Numerical simulation of countercurrent gasliquid film flow over

- Slides: 16

Numerical simulation of countercurrent gas-liquid film flow over an inclined plate Rajesh K. Singh and Janine E. Galvin National Energy Technology Laboratory NETL Multiphase Flow Science Workshop, August 12 -13, 2015 Lakeview Golf Resort & Spa, 150 Lakeview Drive, Morgantown, WV, 26508

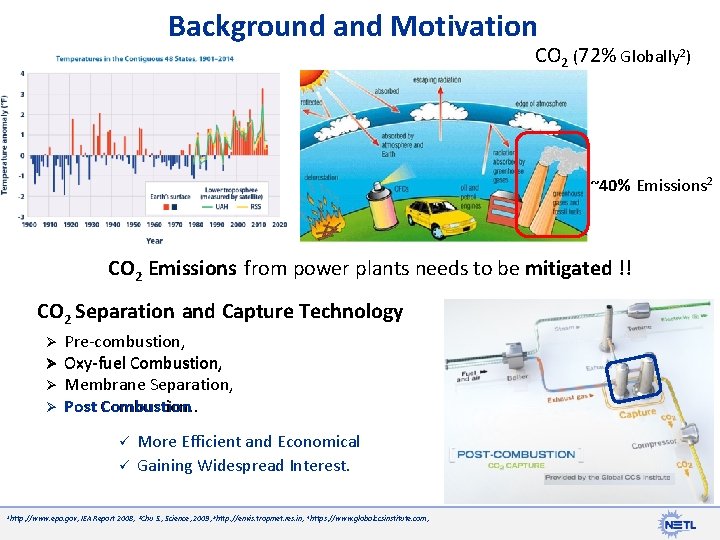

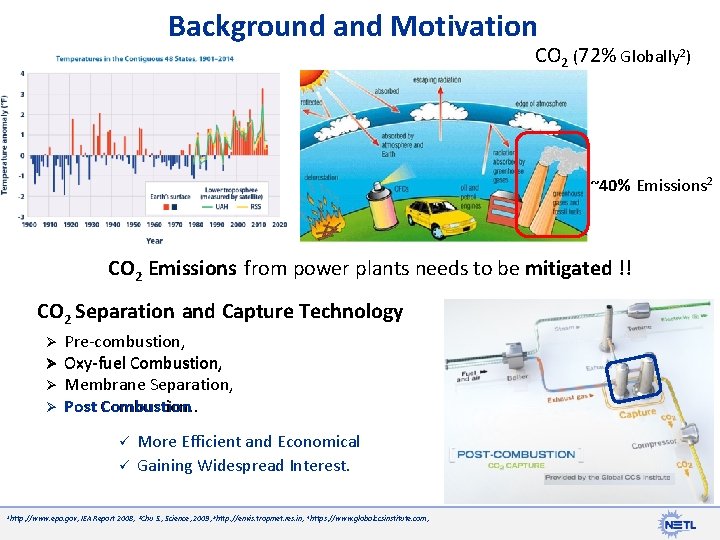

Background and Motivation CO 2 (72% Globally 2) ~40% Emissions 2 CO 2 Emissions from power plants needs to be mitigated !! CO 2 Separation and Capture Technology Ø Ø Pre-combustion, Oxy-fuel Combustion, Membrane Separation, Post Combustion. ü ü 1 http: //www. epa. gov, More Efficient and Economical Gaining Widespread Interest. IEA Report 2008, 3 Chu S. , Science, 2009, 5 http: //envis. tropmet. res. in, 4 https: //www. globalccsinstitute. com,

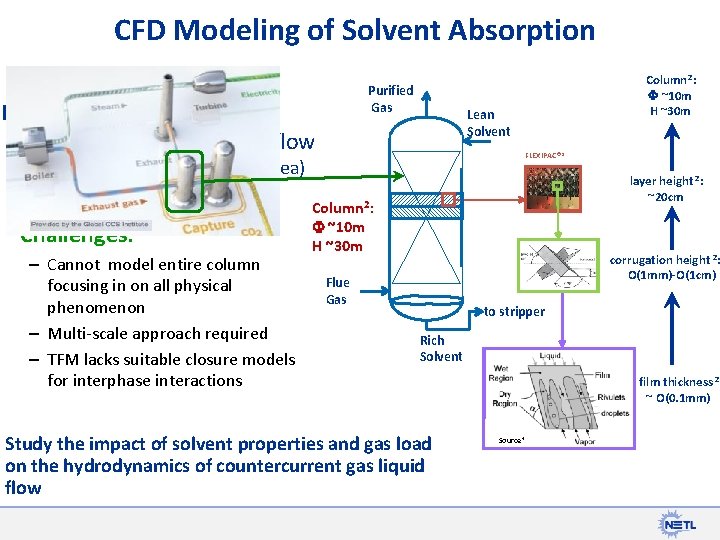

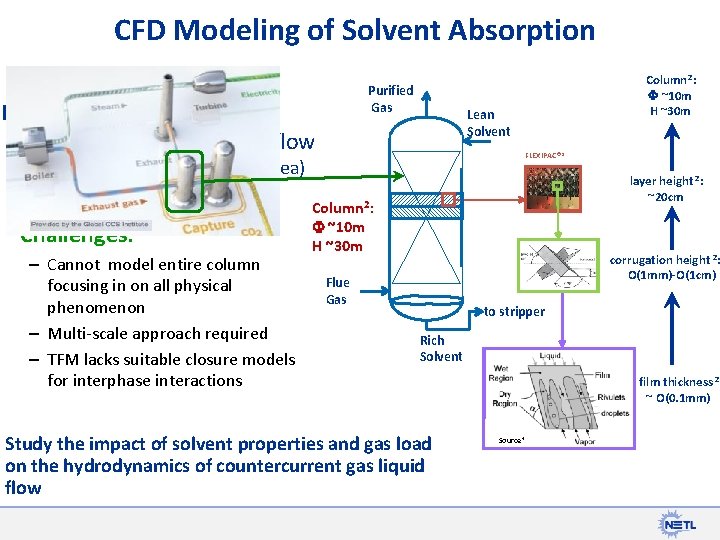

CFD Modeling of Solvent Absorption Purified Gas Efficiency of CO 2 absorption hydrodynamics of local flow Lean Solvent FLEXIPAC® 1 (Pressure Drop, interfacial area) Challenges: – Cannot model entire column focusing in on all physical phenomenon – Multi-scale approach required – TFM lacks suitable closure models for interphase interactions Column 2: F ~10 m H ~30 m layer height 2: ~20 cm Column 2: F ~10 m H ~30 m corrugation height 2: O(1 mm)-O(1 cm) Flue Gas to stripper Rich Solvent Study the impact of solvent properties and gas load on the hydrodynamics of countercurrent gas liquid flow film thickness 2 ~ O(0. 1 mm) Source 4

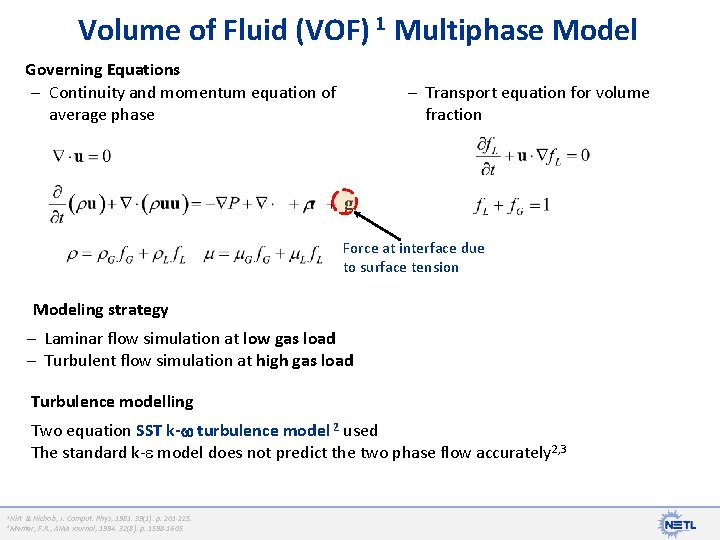

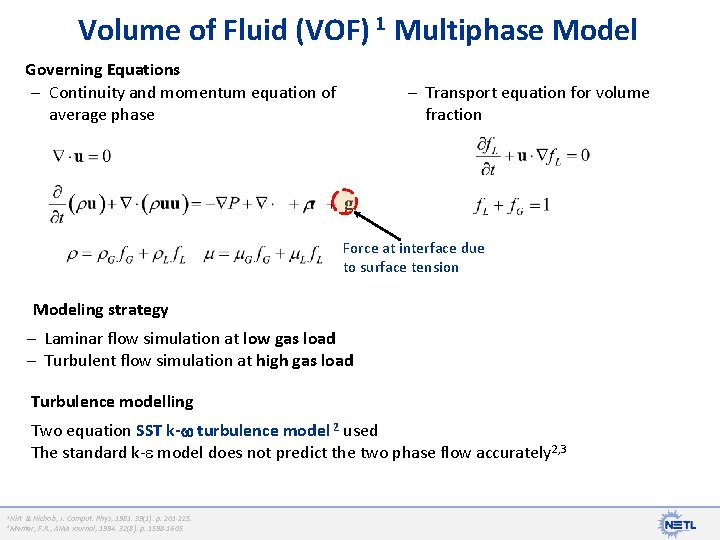

Volume of Fluid (VOF) 1 Multiphase Model Governing Equations – Continuity and momentum equation of average phase – Transport equation for volume fraction Force at interface due to surface tension Modeling strategy – Laminar flow simulation at low gas load – Turbulent flow simulation at high gas load Turbulence modelling Two equation SST k- turbulence model 2 used The standard k- model does not predict the two phase flow accurately 2, 3 1 Hirt & Nichols, J. Comput. Phys, 1981. 39(1): p. 201 -225. F. R. , AIAA Journal, 1994. 32(8): p. 1598 -1605 2 Menter,

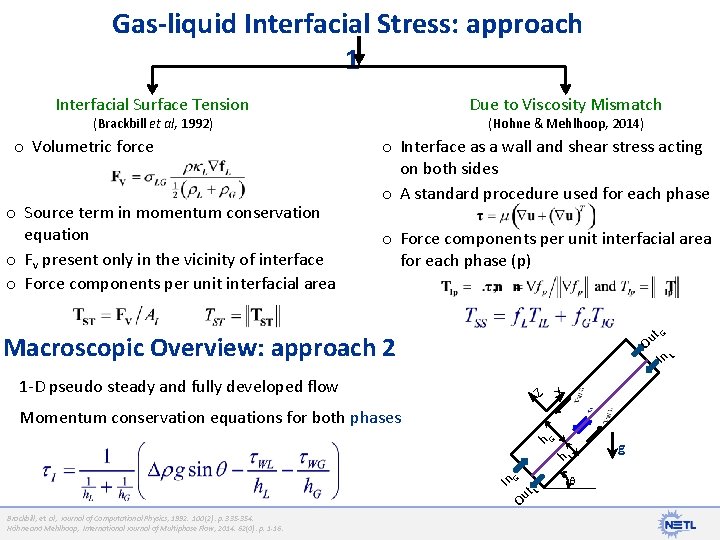

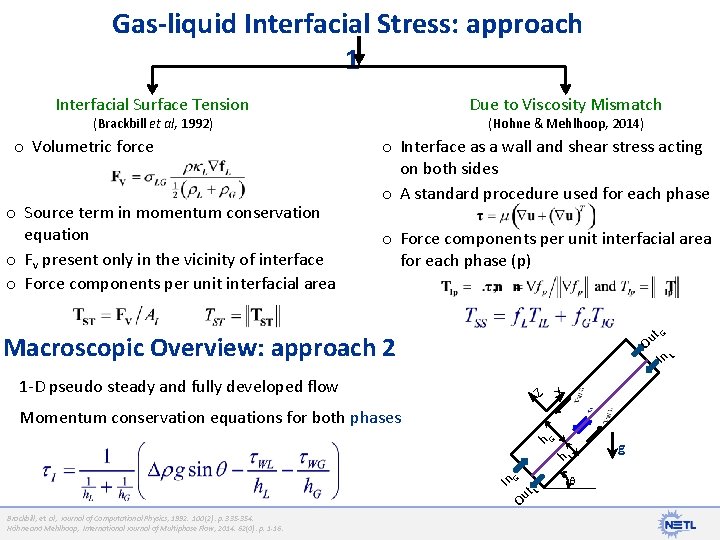

Gas-liquid Interfacial Stress: approach 1 Interfacial Surface Tension Due to Viscosity Mismatch (Brackbill et al, 1992) o Volumetric force o Source term in momentum conservation equation o Fv present only in the vicinity of interface o Force components per unit interfacial area (Hohne & Mehlhoop, 2014) o Interface as a wall and shear stress acting on both sides o A standard procedure used for each phase o Force components per unit interfacial area for each phase (p) Z 1 -D pseudo steady and fully developed flow X L Ou In t. G Macroscopic Overview: approach 2 Momentum conservation equations for both phases Ou t. L In G h L h G g Brackbill, et. al, Journal of Computational Physics, 1992. 100(2): p. 335 -354. Höhne and Mehlhoop, International Journal of Multiphase Flow, 2014. 62(0): p. 1 -16.

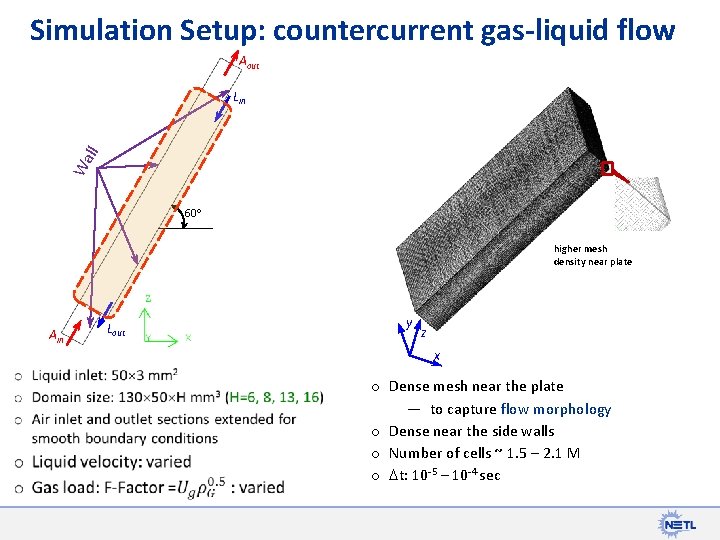

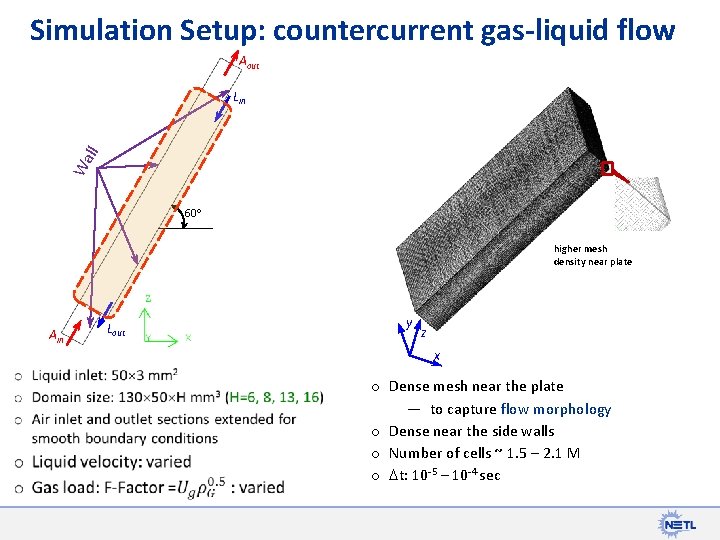

Simulation Setup: countercurrent gas-liquid flow Aout Wa ll Lin 60 higher mesh density near plate Ain Lout y z x o Dense mesh near the plate — to capture flow morphology o Dense near the side walls o Number of cells ~ 1. 5 2. 1 M o t: 10 -5 – 10 -4 sec

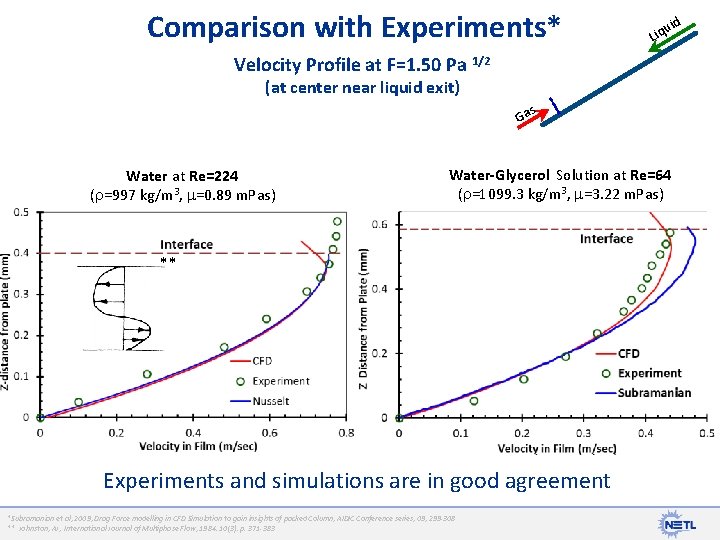

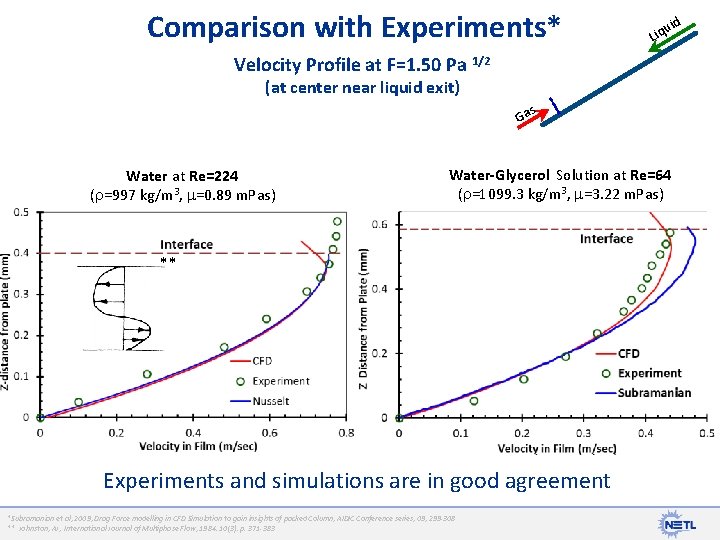

Comparison with Experiments* id iqu L Velocity Profile at F=1. 50 Pa 1/2 (at center near liquid exit) s Ga Water at Re=224 ( =997 kg/m 3, =0. 89 m. Pas) Water-Glycerol Solution at Re=64 ( =1099. 3 kg/m 3, =3. 22 m. Pas) ** Experiments and simulations are in good agreement *Subramanian et al, 2009, Drag Force modelling in CFD Simulation to gain insights of packed Column, AIDIC Conference series, 09, 299 -308 ** Johnston, AJ, International Journal of Multiphase Flow, 1984. 10(3): p. 371 -383

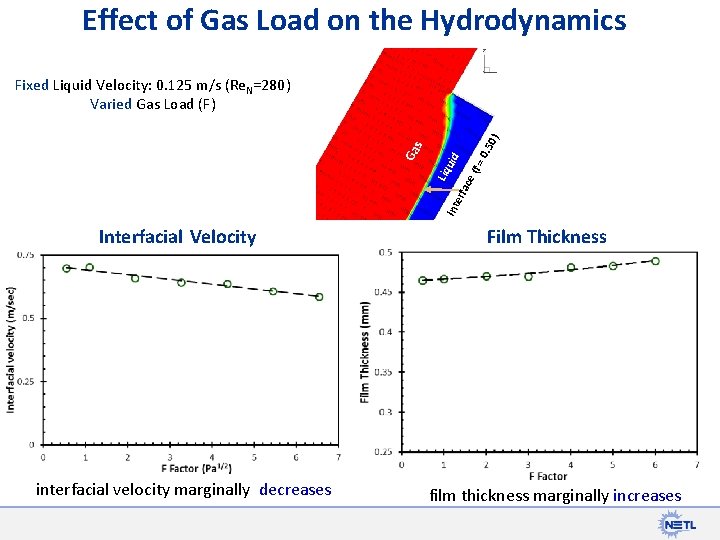

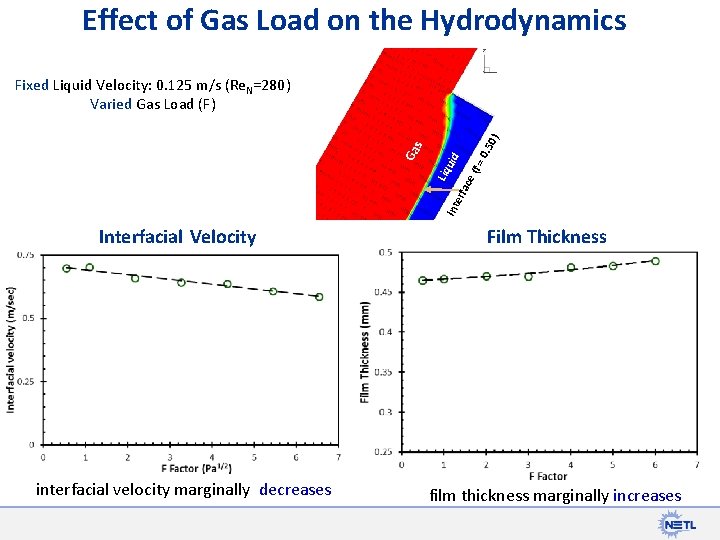

Effect of Gas Load on the Hydrodynamics 0) 0. 5 (f = id ace Int erf Liq u Ga s Fixed Liquid Velocity: 0. 125 m/s (Re. N=280) Varied Gas Load (F) Interfacial Velocity interfacial velocity marginally decreases Film Thickness film thickness marginally increases

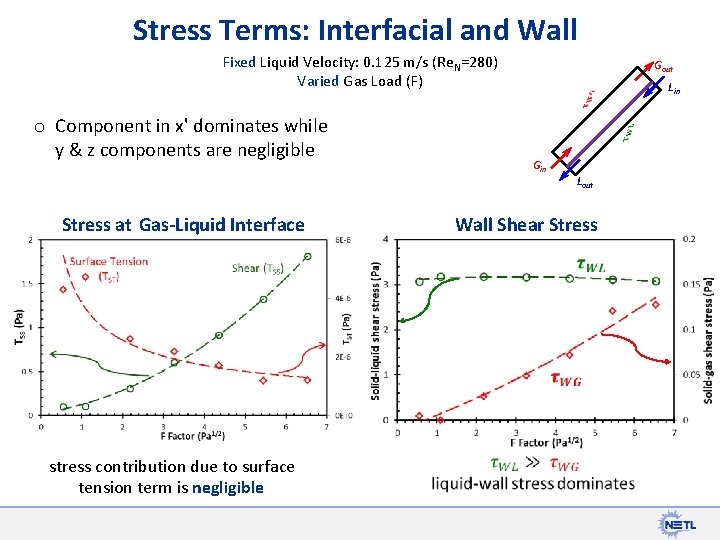

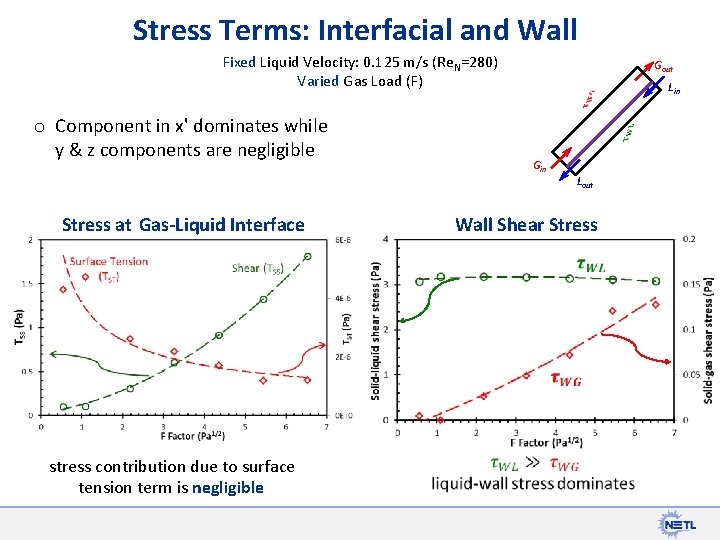

Stress Terms: Interfacial and Wall Fixed Liquid Velocity: 0. 125 m/s (Re. N=280) Varied Gas Load (F) Gout Lin o Component in x' dominates while y & z components are negligible Gin Lout Wall Shear Stress at Gas-Liquid Interface stress contribution due to surface tension term is negligible

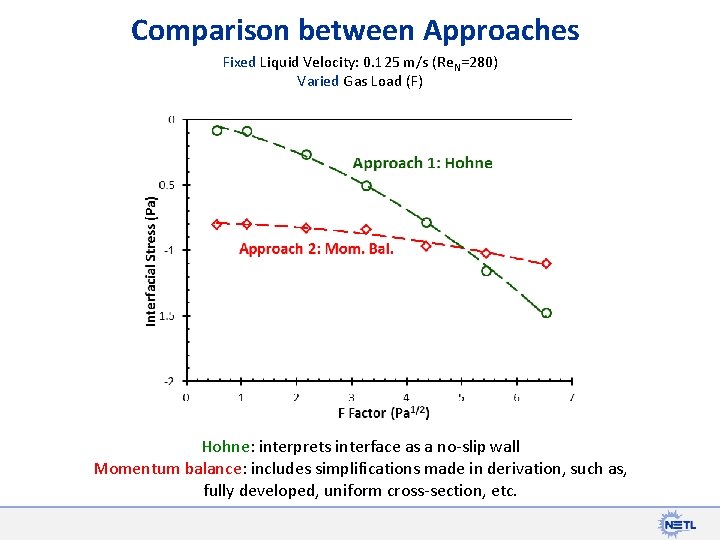

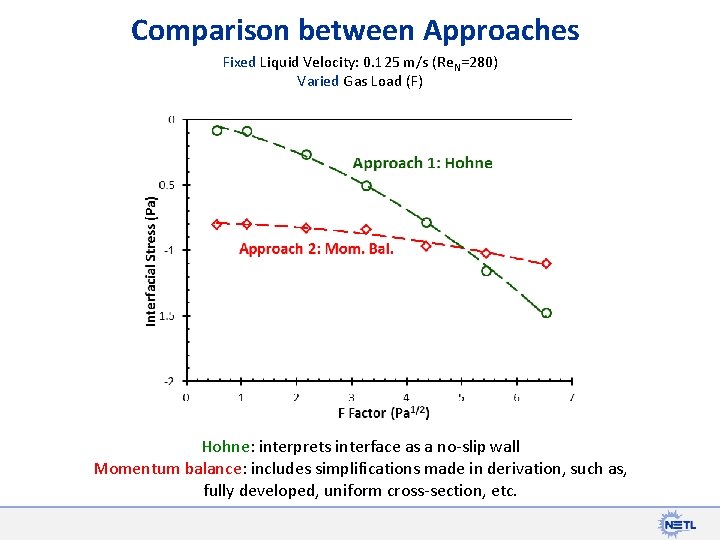

Comparison between Approaches Fixed Liquid Velocity: 0. 125 m/s (Re. N=280) Varied Gas Load (F) Hohne: interprets interface as a no-slip wall Momentum balance: includes simplifications made in derivation, such as, fully developed, uniform cross-section, etc.

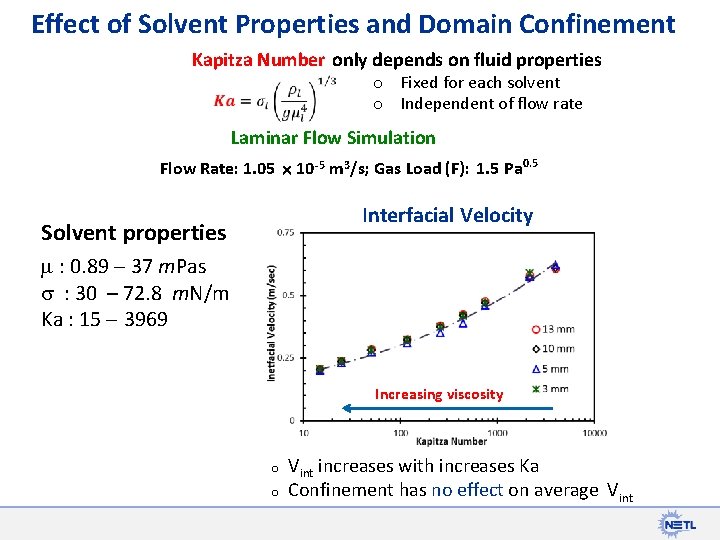

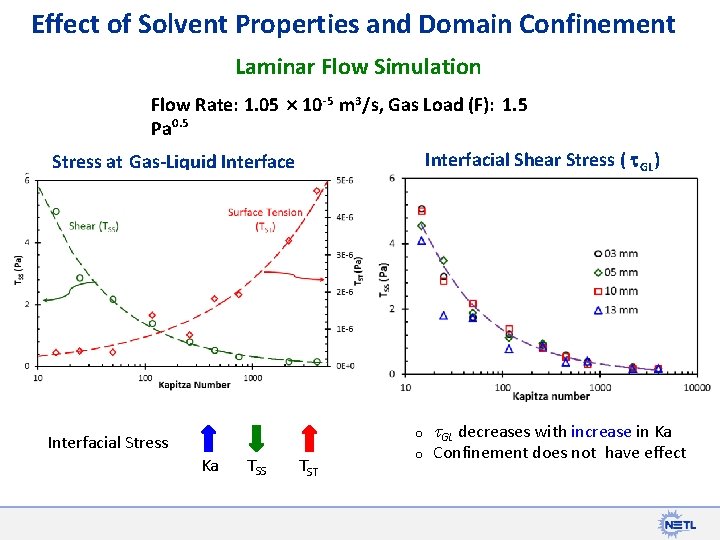

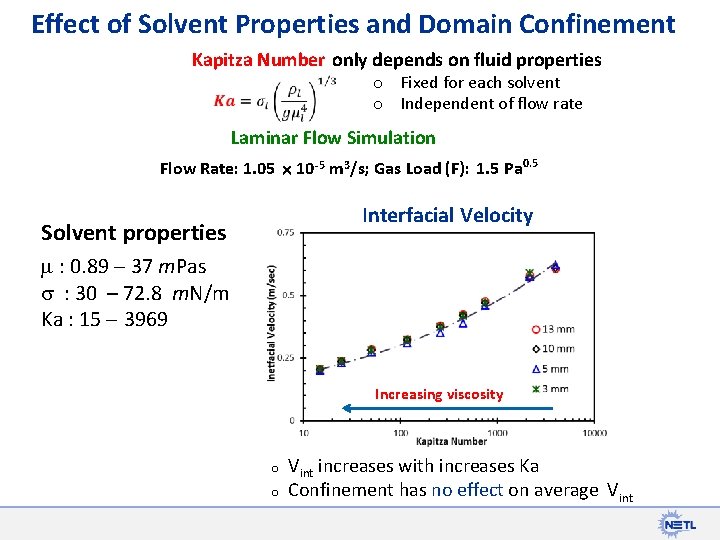

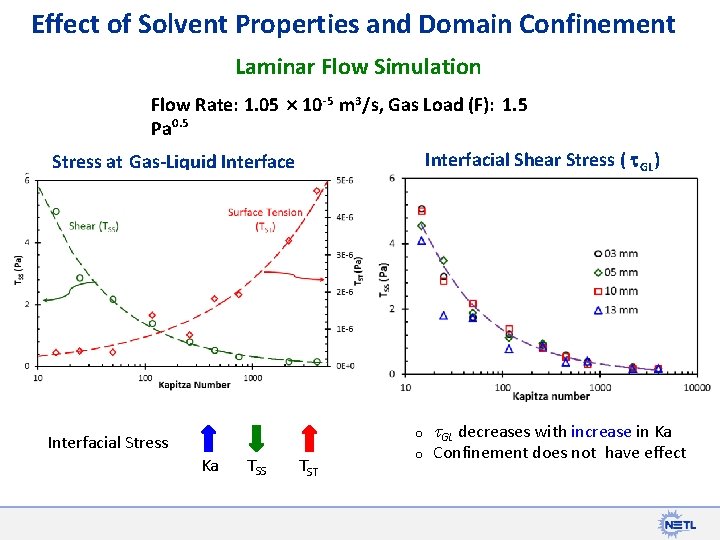

Effect of Solvent Properties and Domain Confinement Kapitza Number only depends on fluid properties o o Fixed for each solvent Independent of flow rate Laminar Flow Simulation Flow Rate: 1. 05 10 -5 m 3/s; Gas Load (F): 1. 5 Pa 0. 5 Interfacial Velocity Solvent properties : 0. 89 37 m. Pas s : 30 – 72. 8 m. N/m Ka : 15 3969 Increasing viscosity o o Vint increases with increases Ka Confinement has no effect on average Vint

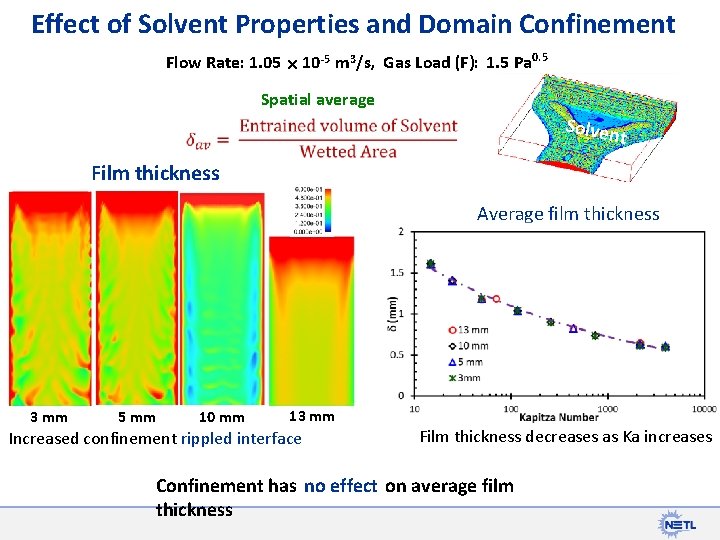

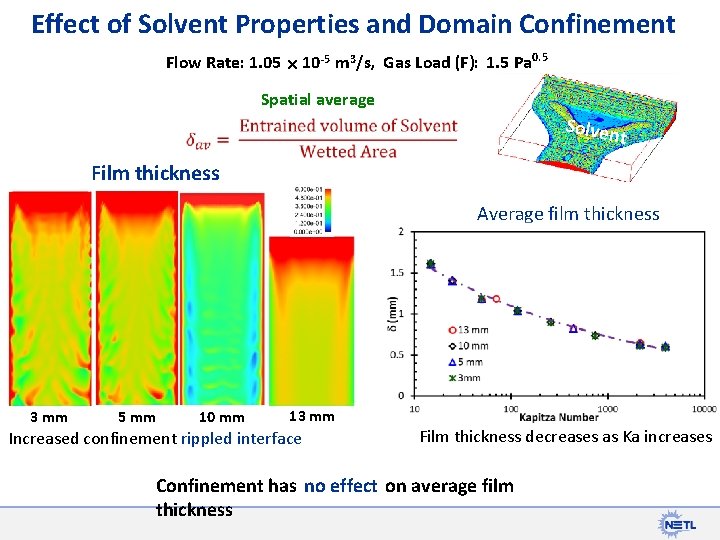

Effect of Solvent Properties and Domain Confinement Flow Rate: 1. 05 10 -5 m 3/s, Gas Load (F): 1. 5 Pa 0. 5 Spatial average Solven t Film thickness Average film thickness 3 mm 5 mm 10 mm 13 mm Increased confinement rippled interface Film thickness decreases as Ka increases Confinement has no effect on average film thickness

Effect of Solvent Properties and Domain Confinement Laminar Flow Simulation Flow Rate: 1. 05 10 -5 m 3/s, Gas Load (F): 1. 5 Pa 0. 5 Interfacial Shear Stress ( t. GL) Stress at Gas-Liquid Interface F=1. 50 o Interfacial Stress Ka TSS TST o t. GL decreases with increase in Ka Confinement does not have effect

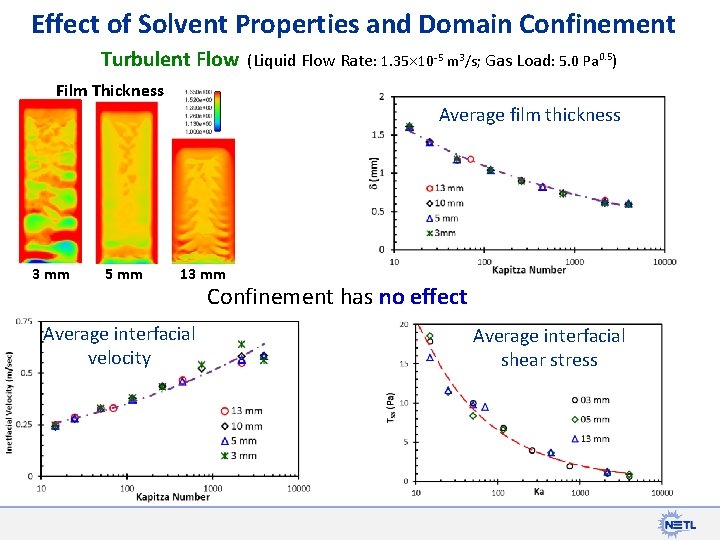

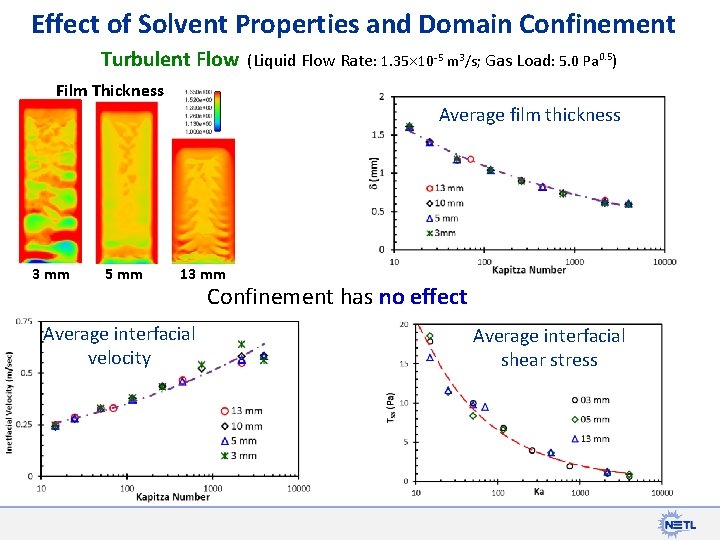

Effect of Solvent Properties and Domain Confinement Turbulent Flow (Liquid Flow Rate: 1. 35 10 -5 m 3/s; Gas Load: 5. 0 Pa 0. 5) Film Thickness Average film thickness 3 mm 5 mm 13 mm Average interfacial velocity Confinement has no effect Average interfacial shear stress

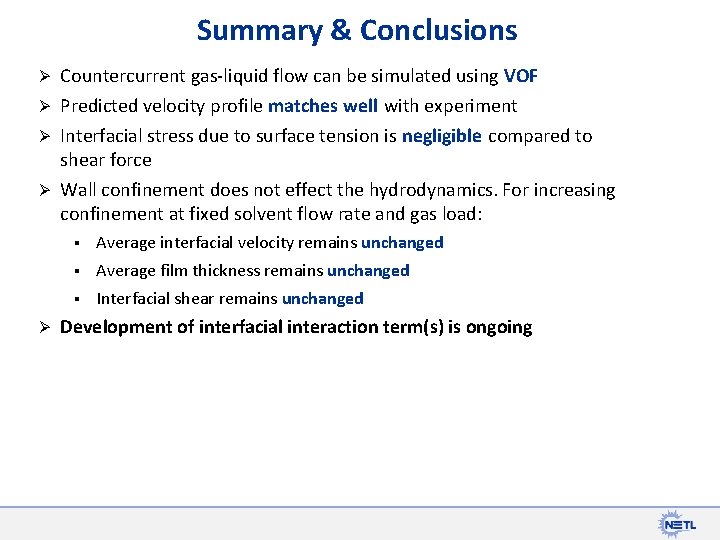

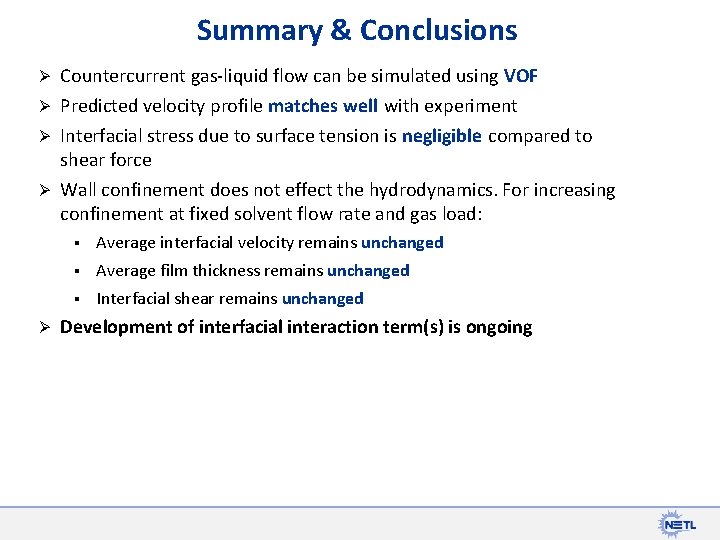

Summary & Conclusions Ø Countercurrent gas-liquid flow can be simulated using VOF Predicted velocity profile matches well with experiment Ø Interfacial stress due to surface tension is negligible compared to shear force Ø Wall confinement does not effect the hydrodynamics. For increasing confinement at fixed solvent flow rate and gas load: Ø Ø § Average interfacial velocity remains unchanged § Average film thickness remains unchanged § Interfacial shear remains unchanged Development of interfacial interaction term(s) is ongoing

Acknowledgments – Carbon Capture Simulation Initiative (CCSI) – NETL Simulation Based Engineering User Center (SBEUC) – Dr. Brian Bell (Ansys Inc. ) Disclaimer: This work is made available by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government, the Department of Energy, the National Energy Technology Laboratory, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, including warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favor by the United States Government, the Department of Energy, or the National Energy Technology Laboratory. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, the Department of Energy, or the National Energy Technology Laboratory, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes.