Numerals and Numbers How characters and integers are

Numerals and Numbers How characters and integers are represented inside a computer (and in assembly language)

What is ASCII? • Humans can communicate with machines • But need a language each understands • English language employs a finite set of character-symbols (‘alphabet’) of letters, plus digits and various punctuation-marks • Character-symbols are assigned ‘values’ • American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) is a standard scheme

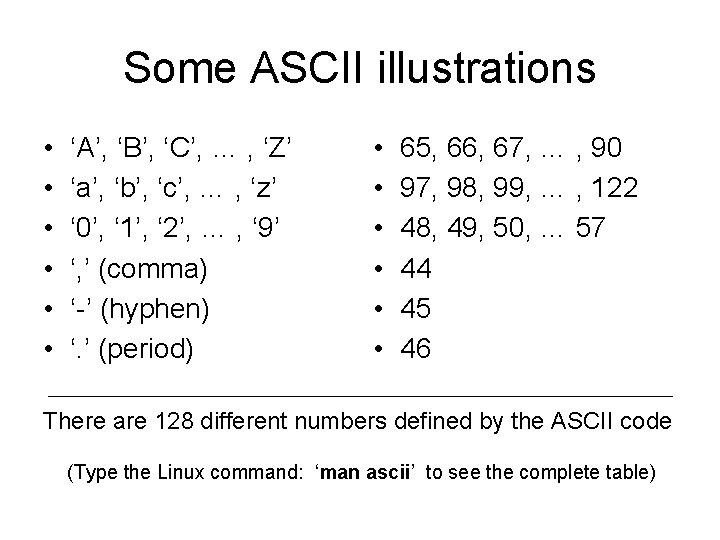

Some ASCII illustrations • • • ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’, … , ‘Z’ ‘a’, ‘b’, ‘c’, … , ‘z’ ‘ 0’, ‘ 1’, ‘ 2’, … , ‘ 9’ ‘, ’ (comma) ‘-’ (hyphen) ‘. ’ (period) • • • 65, 66, 67, … , 90 97, 98, 99, … , 122 48, 49, 50, … 57 44 45 46 There are 128 different numbers defined by the ASCII code (Type the Linux command: ‘man ascii’ to see the complete table)

ASCII ‘control-codes’ • • ASCII was devised for typewriter terminals Some code-values denote ‘typing motions’ The ‘back-space’ motion is 8 The ‘tab’ motion is 9 The ‘new-line’ motion is 10 The ‘carriage-return’ motion is 13 A code exists for the typewriter’s bell: 7

Numerals versus Numbers • A ‘numeral’ is a digit-character: ‘ 1’, ‘ 2’, … • The digit-character ‘ 0’ has ASCII value 48 • The digit-character ‘ 1’ has ASCII value 49 … • The digit-character ‘ 9’ has ASCII value 57 • So a ‘numeral’ isn’t what it appear to be! e. g. , character ‘ 7’ isn’t equal to number 7

Communicating in ASCII • • • Humans talk to computers using ASCII Computer says: Give me a number Human replies: ok, I will say ‘ 6’ Computer must ‘interpret’ this input Must ‘convert’ the character’s ASCII-value into the number-value that was intended • It’s easy: computer can just do subtraction ‘ 6’ – ‘ 0’ = 54 – 48 = 6

Bigger numbers? • • Computer says: Tell me a bigger number Human thinks: ok, how about ninety-five? Human types in two digits: ‘ 9’ and ‘ 5’ Here the typing-order is important: because “ 95” means 9 -times-10, plus 5 • Computer sees two ASCII values: 57, then 53 • It must convert 57 into 9, and 53 into 5, and then do a multiplication (by 10) and an addition step

Positional Notation • We use the Hindu-Arabic notation system • It uses ten digit-symbols: ‘ 0’, ‘ 1’, ‘ 2’. … , ‘ 9’ • For writing numbers bigger than nine, the digit-symbols are comined in a sequence: so three hundred sixty-five is written “ 365” • The “position” of each digit is significant, as it affects what that digit really means • Meanings determined by the number-base

Other number bases? • • An analogy: base two versus base ten Base-ten uses ten digits: 0, 1, 2, … , 0 Base-two uses two digits: 0, 1 3 -digit number using base ten: 365 3 -digit number using base two: 101 365 (base 10) means 3 x 100 + 6 x 10 + 5 x 1 101 (base 2) means 1 x 4 + 0 x 2 + 1 x 1 101 (base 10) means 1 x 100 + 0 x 10 + 1 x 1

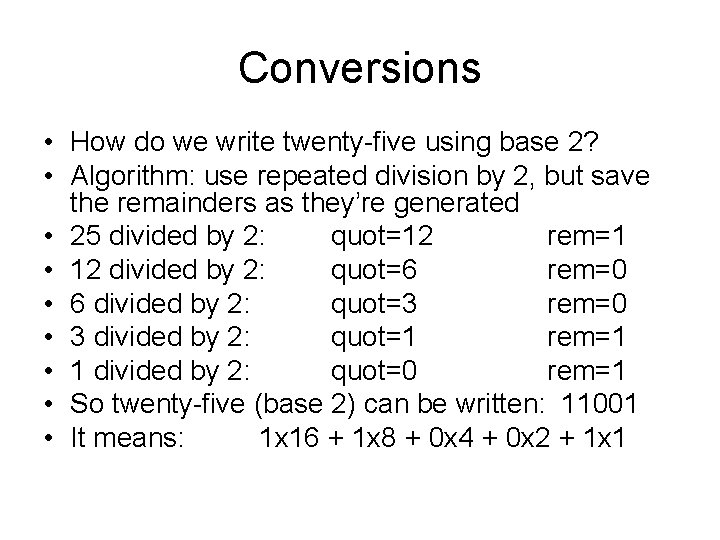

Conversions • How do we write twenty-five using base 2? • Algorithm: use repeated division by 2, but save the remainders as they’re generated • 25 divided by 2: quot=12 rem=1 • 12 divided by 2: quot=6 rem=0 • 6 divided by 2: quot=3 rem=0 • 3 divided by 2: quot=1 rem=1 • 1 divided by 2: quot=0 rem=1 • So twenty-five (base 2) can be written: 11001 • It means: 1 x 16 + 1 x 8 + 0 x 4 + 0 x 2 + 1 x 1

Exercise • • Write forty-nine in base 8 notation? 49 divided by 8: quot=6 rem=1 6 divided by 8: quot=0 rem=6 We stop when quotient equals zero Answer: 49 (base 8) is written as 61 It means (positional notation): 6 x 8 + 1 x 1 Note: remainders used in backward order!

- Slides: 11