Numbers Where do they come from Where do

Numbers Where do they come from? Where do they go?

• Numbers come out of measurement.

Types of Measurement • • • Length, area, volume. Weight/mass. Duration. Speed. Density. . (many more).

• Counting is also a form of measurement.

Key Properties of Measurement, I Comparison With respect to a given type of measurement, any two quantities can be compared: • Either they are equal, or one is larger and one is smaller.

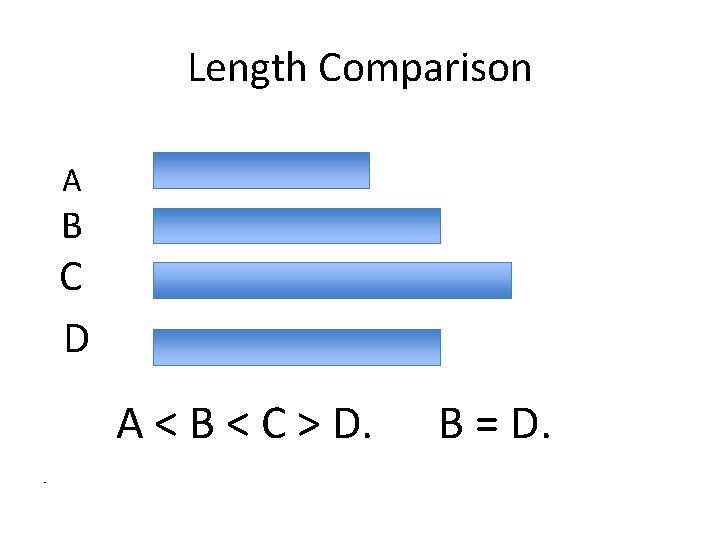

Length Comparison A B C D A < B < C > D. • B = D.

Key Properties of Measurement, II Combination Measureable objects can be combined to give a combined measurement.

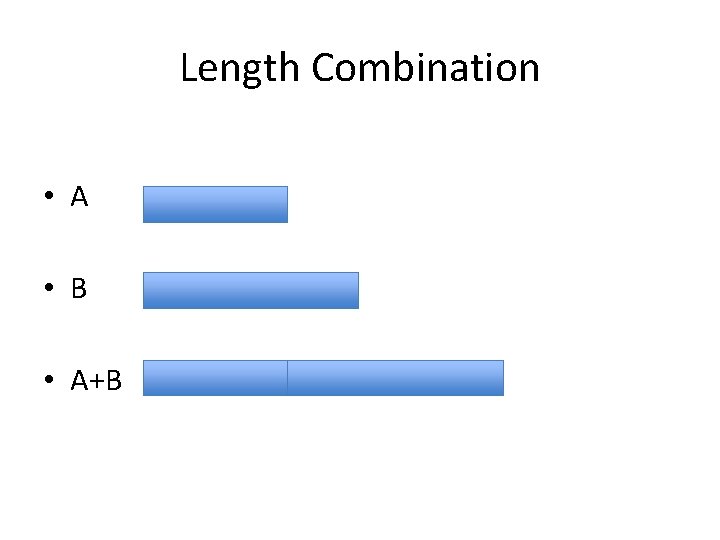

Length Combination • A • B • A+B

Key Properties of Measurement, III Replication • A measurable object can be replicated any desired (whole) number of times.

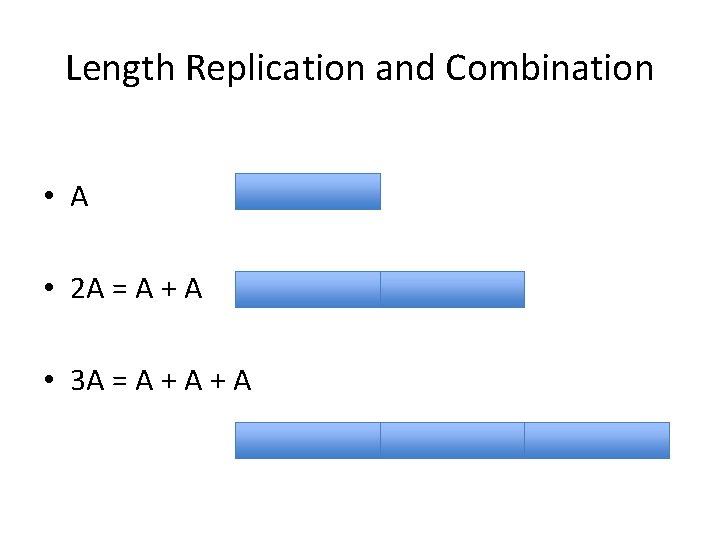

Length Replication and Combination • A • 2 A = A + A • 3 A = A + A

Key Properties of Measurement, IV Partition • A measureable object can be subdivided into a desired (whole) number of equal parts/subobjects. (May not apply in counting situations. )

Length Partitioning • A = (½) A + (½) A A=( )A+ ( ) A + ( )A

Numbers as Operators/Ratios/Multipliers • The operations of replication and subdivision allow to construct any rational multiple of a given quantity. • Other (i. e. , irrational multiples) are then constructed by approximation – sandwiching them between rational numbers.

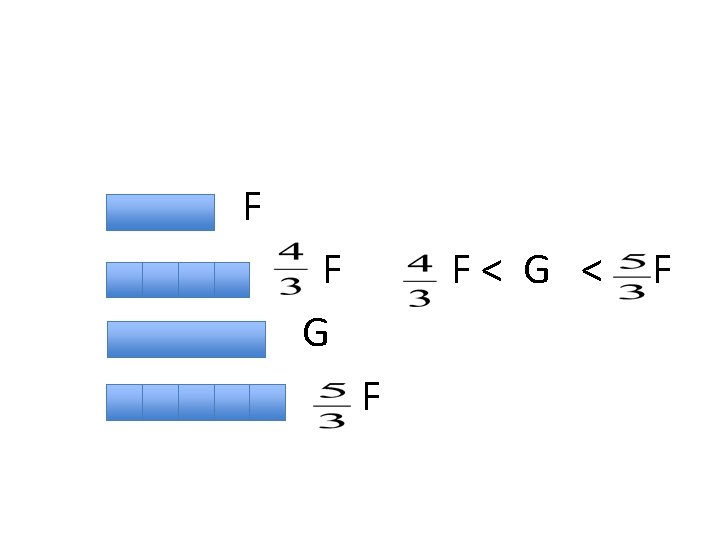

F F G F< G < F F

Numbers from/in Measurement Summary • A number gives a • multiplicative comparison • between two quantities.

Numbers and Quantities • You attach numbers to individual quantities/amounts by • choosing a unit.

• By itself, a number does not signify any specific object or quantity. • To do that, it must refer to a unit.

• The number then tells you how large the given amount is, • in relation to (i. e. , as a multiple of) the unit.

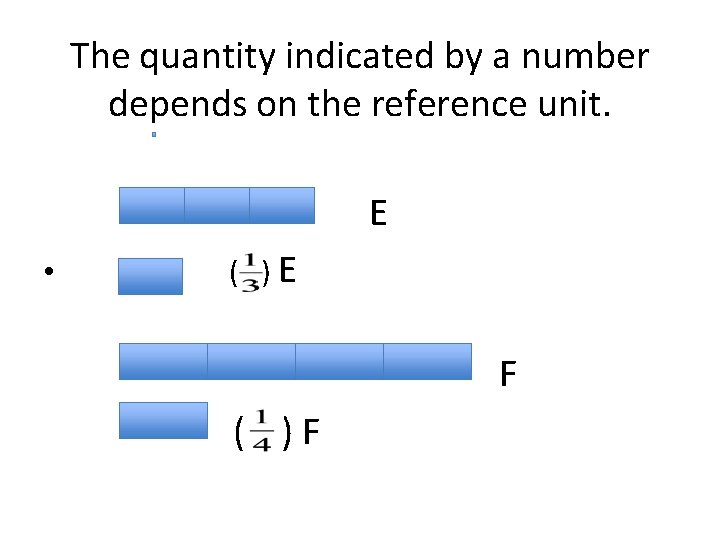

The quantity indicated by a number depends on the reference unit. E • ( )E F ( )F

Pedagogical Note • Although numbers are essentially multiplicative, students meet them first as counts, in an essentially additive context.

• Dealing successfully with fractions requires reconceptualizing numbers in terms of multiplicative comparison.

• This reorganization is perhaps best approached by promoting • unit consciousness, • i. e. , a habit of being aware of and of specifying the relevant unit. • Having students do many unit conversions is one way to encourage this.

The bugaboo in adding fractions • Another crucial convention about units: • If we see the “equation” • 3 + 4 = 2, (not!) it seems like nonsense.

• But the equation • 3 dimes + 4 nickels = 2 quarters • makes perfectly good sense.

• What’s the difference? • In the first, there is no explicit reference unit, • So, you assume all the numbers refer to the same unit.

• This is the standing convention, often not conscious, when we write addition equations.

• In the second equation, the units are specified, and you can relate them all to a common unit, for example, pennies.

• Then • 3 dimes + 4 nickels = 2 quarters reads • 3 x 10 + 4 x 5 = 2 x 25, which is correct in the normal sense.

• The popular wrong way of adding fractions, by adding numerators and adding denominators, stems from the same • failure to attend to units.

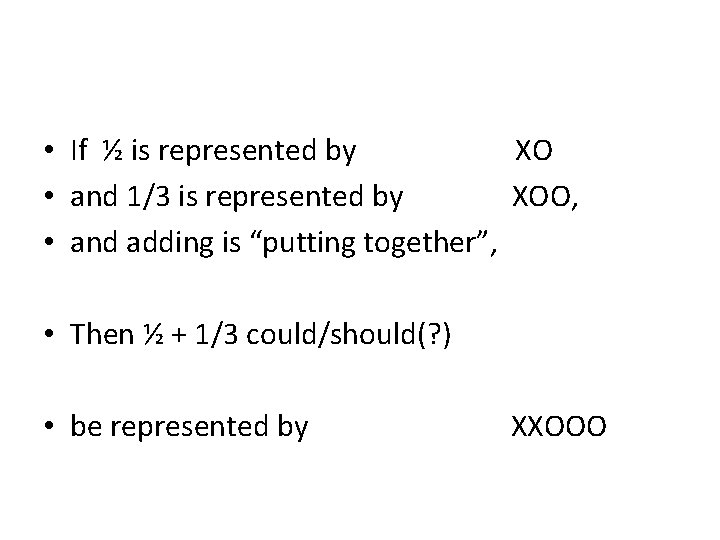

• If ½ is represented by XO • and 1/3 is represented by XOO, • and adding is “putting together”, • Then ½ + 1/3 could/should(? ) • be represented by XXOOO

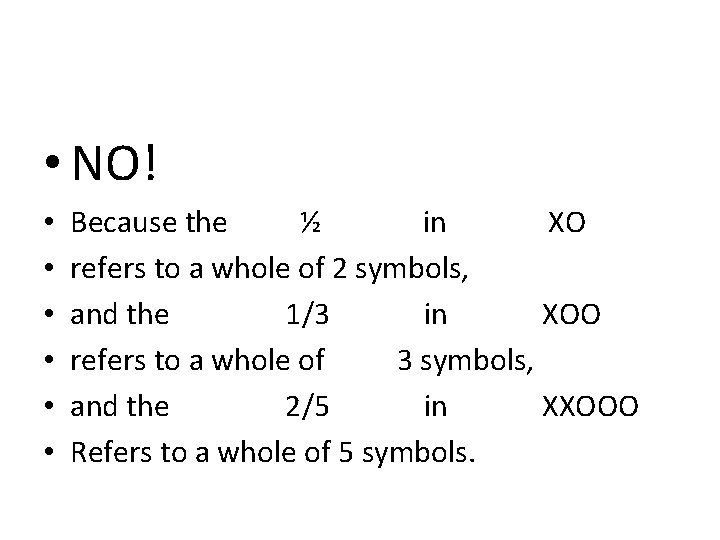

• NO! • • • Because the ½ in XO refers to a whole of 2 symbols, and the 1/3 in XOO refers to a whole of 3 symbols, and the 2/5 in XXOOO Refers to a whole of 5 symbols.

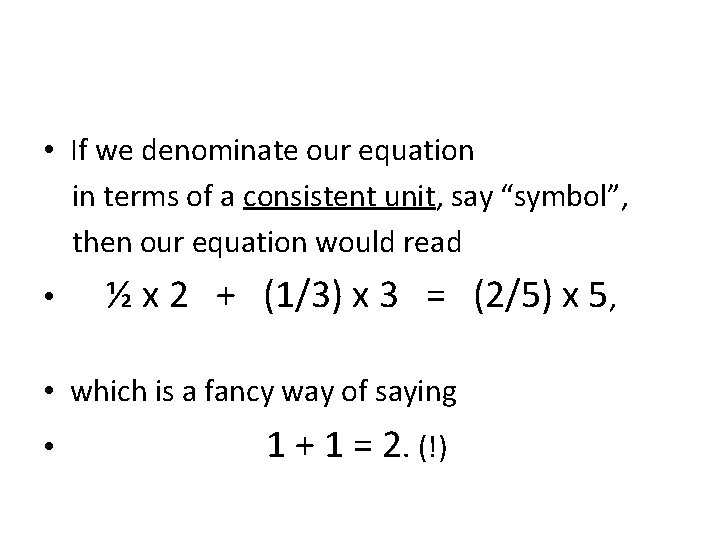

• If we denominate our equation in terms of a consistent unit, say “symbol”, then our equation would read • ½ x 2 + (1/3) x 3 = (2/5) x 5, • which is a fancy way of saying • 1 + 1 = 2. (!)

Moral • Make your students • Attend to the unit! • This is an important case of the CCSSM mathematical practice • “Attend to precision”.

• (With thanks to Herb Gross. )

Number Line, I • We can find a standard representative for each length by choosing • a line, • a point (origin) on the line, • and an orientation (direction) on the line.

• • Then each length can be represented by an interval, starting at the origin, and going in the positive direction.

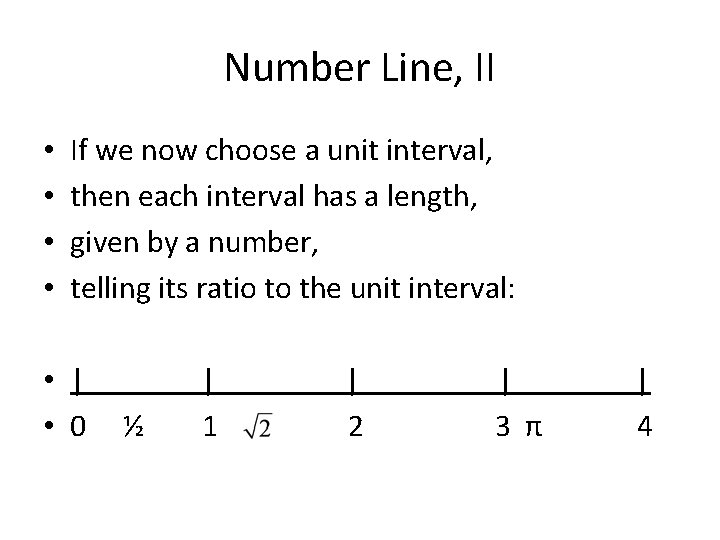

Number Line, II • • If we now choose a unit interval, then each interval has a length, given by a number, telling its ratio to the unit interval: • | • 0 ½ | 1 | 2 | 3 π | 4

Number Line, III • Including intervals of both orientations produces the full number line, with both positive and negative numbers.

Part II • Numbers come out of measurement, but dealing with them involves • arithmetic, which gives rise to • algebra.

• In algebra, we need to know the • “Properties of the Operations”, aka • The Rules of Arithmetic.

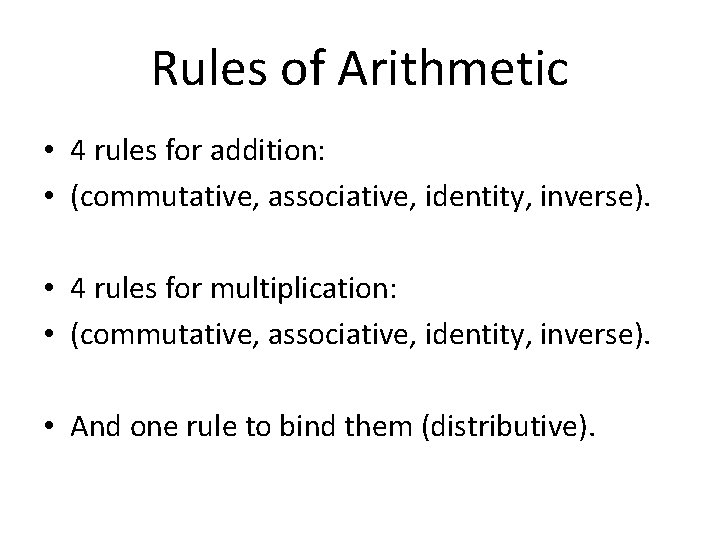

Rules of Arithmetic • 4 rules for addition: • (commutative, associative, identity, inverse). • 4 rules for multiplication: • (commutative, associative, identity, inverse). • And one rule to bind them (distributive).

Numbers for Mathematicians • Mathematicians do not like units. • Mathematicians like formal rules. • So: mathematicians are willing to call any collection that satisfies these rules, “numbers”.

• There are • many, many • different kinds of systems of such “numbers”. • They are called “fields”.

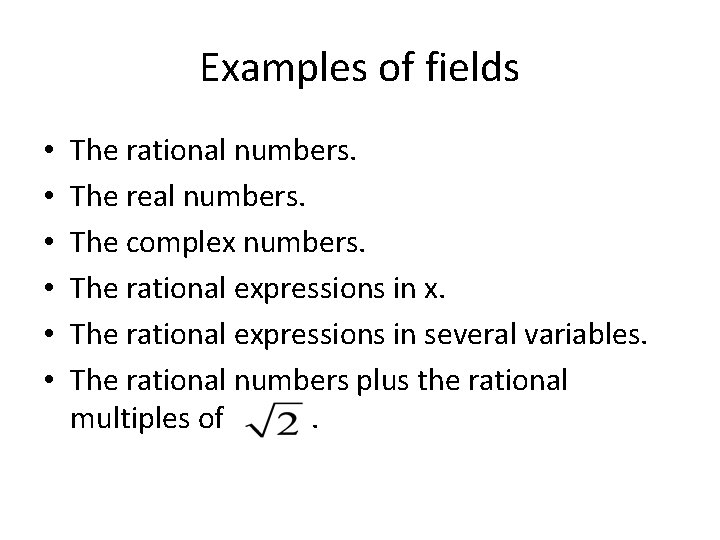

Examples of fields • • • The rational numbers. The real numbers. The complex numbers. The rational expressions in x. The rational expressions in several variables. The rational numbers plus the rational multiples of.

More Examples • The rational numbers plus the rational multiples of i. • For every power of a prime number there is a field with this number of elements. • And many, many more. . .

• So by focusing on the structure imposed by the rules, we gain a huge number of new number systems.

What is lost? • There is no notion of size, or ordering. • You can’t say that one number is larger than another. • These “numbers” may be useless for measurement!

• For example, you could take a “number”, such as “ 2”, and raise it to a large power, and the result could be “ 2” again! or even “ 1”!

• Mathematicians don’t care! • Measurement is for scientists! • Mathematicians like algebra!

• Such “numbers”can be useful. • For example, they are used • in the RSA cryptosystem, • that keeps your online bank transactions private.

• Also, these “numbers” are related to some topics in K-12 math, e. g: • telling time; and the old arithmetic technique of • “casting out nines”.

Casting Out Nines • Given a base 10 number, sum the digits. • Repeat, and repeat, until you get a single digit.

• Then, let A and B be base ten numbers. • Cast out nines for A, and for B. • Multiply, and cast out nines on the product, if necessary.

• Multiply AB. • Cast out nines on the product. • The result will be the same! • This was used to check arithmetic • in the era of hand computation.

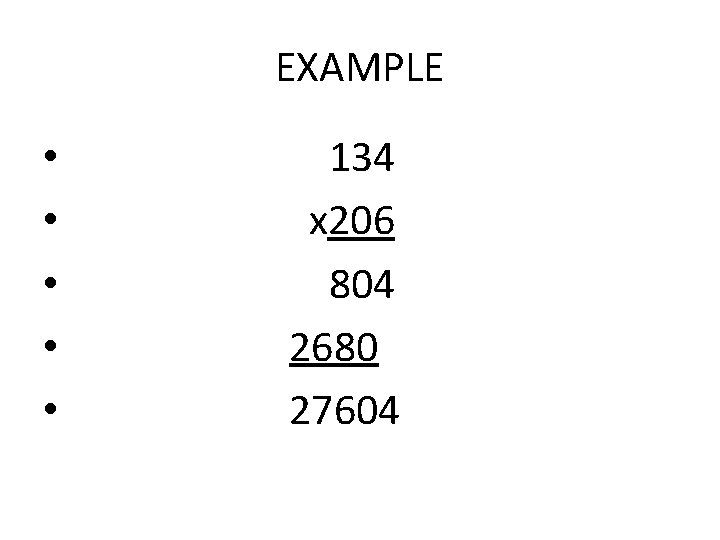

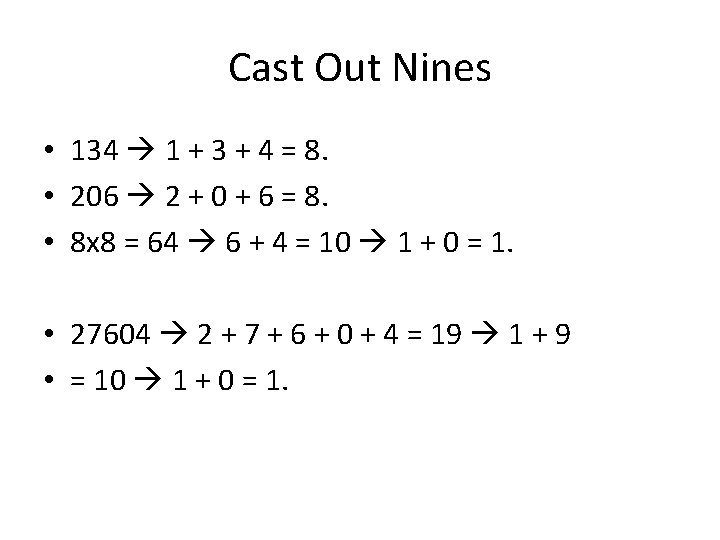

EXAMPLE • • • 134 x 206 804 2680 27604

Cast Out Nines • 134 1 + 3 + 4 = 8. • 206 2 + 0 + 6 = 8. • 8 x 8 = 64 6 + 4 = 10 1 + 0 = 1. • 27604 2 + 7 + 6 + 0 + 4 = 19 1 + 9 • = 10 1 + 0 = 1.

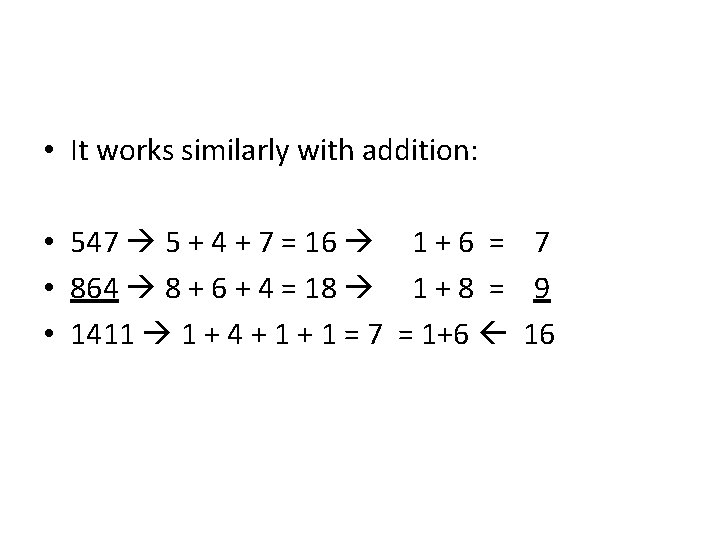

• It works similarly with addition: • 547 5 + 4 + 7 = 16 1 + 6 = 7 • 864 8 + 6 + 4 = 18 1 + 8 = 9 • 1411 1 + 4 + 1 = 7 = 1+6 16

The Field with 2 Elements • The simplest such system is “even” and “odd”. • “Even” functions as zero, and “odd” is one.

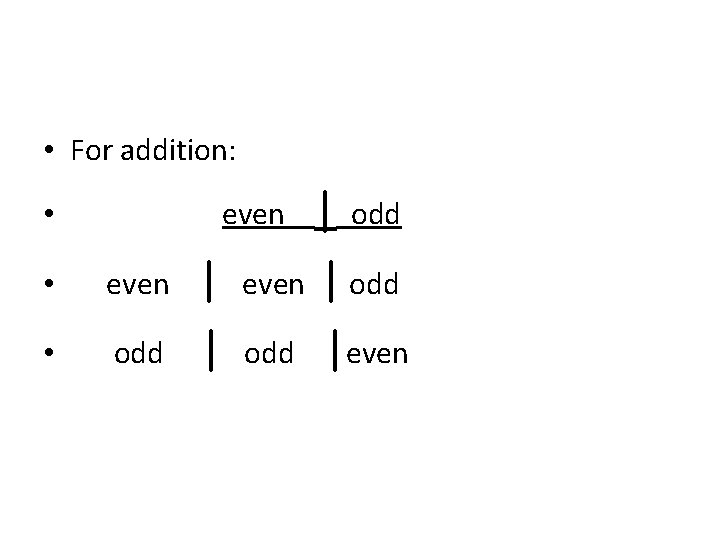

• For addition: | odd | even | odd |even • • even • odd

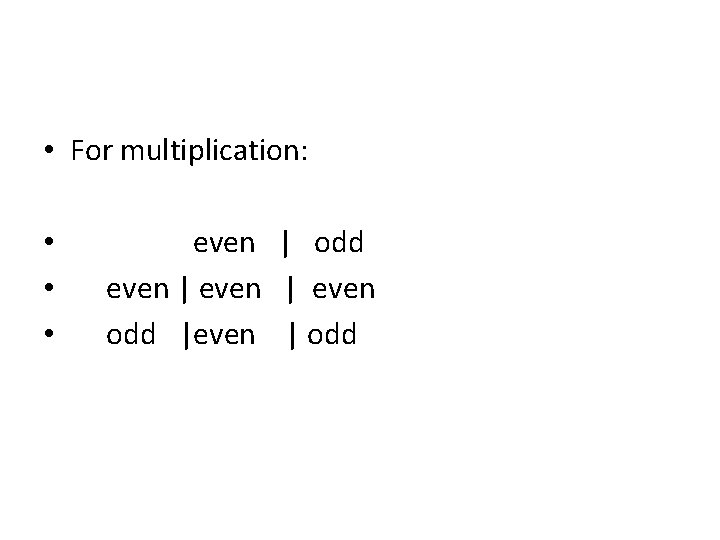

• For multiplication: • • • even | odd even | even odd |even | odd

Summary • In the K-12 journey, the concept of number undergoes two major transitions:

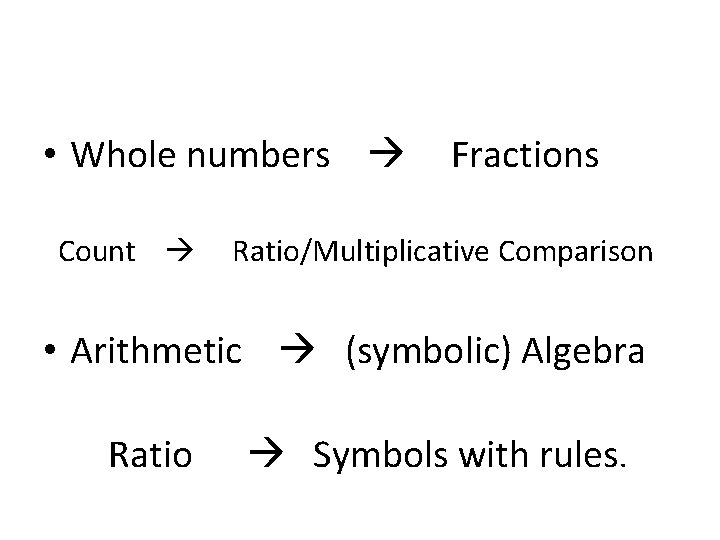

• Whole numbers Count Fractions Ratio/Multiplicative Comparison • Arithmetic (symbolic) Algebra Ratio Symbols with rules.

• Helping our students understand negotiate these transitions is an essential task of mathematics instruction.

• Thank you! • And good luck!

- Slides: 65