Non Violent Resistance and a Focus on the

- Slides: 29

Non Violent Resistance and a Focus on the Child problem behaviour, resistance, reconciliation and child needs – a brief introduction Dr Peter Jakob Consultant Clinical Psychologist

Changing our Underlying Beliefs • Habitual patterns of aggressive behaviour show a coercive effect (Peterson). In effect, recurrent aggressive behaviour is controlling behaviour. – – physical aggression: threatening physical violence, eliciting feelings of guilt, threatening self-harm, embarrassment of family members, etc. • By trying to control, care-givers operate within the same logic of control as the child – control or be controlled. Most violent or aggressive young people refuse to be controlled. The result is symmetrical escalation. • Trying reduce aggression, care-givers often accommodate or appease, and become controlled by the child – reinforcing the aggressive behaviour

Controlling Behaviour in other Problem Areas • Many other problem areas show at least elements of controlling behaviour towards others: – anxiety-related difficulties such as OCD and self-isolation, – entitled dependency in adults with or without enduring mental health problems, – eating disorders, – chronic paediatric illness.

Escalation • Symmetrical escalation: parent and child each attempt to win the upper hand by countering the move of the other. – Arousal levels in parent and child increase – often staying higher than normal even when there have been no recent incidents, especially where there has been previous trauma. – Arousal shoots up during a cycle of mutually escalating controlling behaviour. – Ability to see the future, plan, check progress against plan, social perception and empathy, mentalising and creativity decrease. mutual demonisation, relational rupture

Accomodation and Avoidance • “Complementary escalation” – interaction cycles in which the young person becomes increasingly powerful and the parent increasingly helpless, anxious or depressed – Parent attempts to prevent or reduce aggressive behaviour by accommodating the child – giving in / automatic parental obedience – Anxious avoidance : physical, by staying away from child / psychological, by reducing attention to the child or becoming dissociative Reduced parental presence.

Symmetrical Escalation or Accommodation and Avoidance?

Escalation and Frightened/Frightening Parenting • We know that anxious responses in parents when they are approached by an infant, as well as angry, hostile, critical or unfriendly parental responses raise anxiety in children, and a pattern of seeking the parental attachment figure, and then fleeing from the parent. This forms a pattern known as ‘disorganised attachment’ • Frightened and frightening parenting is mirrored in symmetrical escalation. • From a trauma-oriented point of view, we see successive mutual triggering of traumatic responses/cues in parent and child.

Key Elements of NVR • Breaking Taboo’s – caregivers disobey: they start showing behaviours they would have shown, had they not been inhibited by the young person’s coercion. They stop showing behaviours which have been triggered by the young person’s coercion. • De-escalating- caregivers focus on risk-management during an aggressive incident, and learn to defer their response until later: Strike the iron when it’s cold! • Building support networks – creating alliances with other adults. • Raising presence by taking direct action – protest. • Negotiation and agreement • Reparation and restoration • Reconciliation – gestures that show unconditional regard and love.

De-escalation and Deferred Response • Parents and other care-givers do not aim to change the child during an aggressive incident. All action aims to minimize risk and lower psycho-physiological arousal of adults and child. • Deferring the response: instead of re(!)-acting to provocation, care-givers act at a time of their own choosing, and in a way themselves determine. When they do take action, later, they aim to raise their personal presence as parents, carers or teachers, not punish or change the way the child sees things.

“Try to avoid eye contact…”

Raising Care-giver Presence • NVR does not operate with consequences and rewards, nor does it aim to create insight in the young person. The key factor in changing the parent child relationship through increased parental presence. – Parents increase their physical presence and psychological attention to the child. – Caregivers begin to refuse to accommodate. – Positive action methods enable parents to challenge the young person, when he or she retaliates or attempts to regain control through aggression – without escalating. – Reconciliation gestures help repair the ruptured relationship and promote more secure attachment.

Three dimensions of presence • Physical, temporal presence: – I am here, I won’t go away, I will return. • Internal, embodied presence: – I will bear my anxiety rather than giving in to it, I will overcome my anger by developing agency, I will remain calm, I persevere and am determined, I accept my child as a person and as one of us; I face my child rather than turning away, I will not give up on you. • Systemic presence: – I will not keep secrets, I connect with other adults and seek their support, I have agency in requesting the kind of support I need from other adults, my supporter and I act in unison, my supporter’s physical presence supports my embodied presence with my child, my action is transparent and I accept my supporter as a corrective, my supporter validates my action and the position I take.

Presence - Raising Methods • Positive action methods: parents show a deferred response to a violent incident – striking the iron when it’s cold – plan their action and utilise social support. Careful preparation helps reveal unhelpful beliefs, anxiety-driven responses and even subtle escalatory communication. – – . Announcement: a one-off family ritual drawing a boundary Sit-in: challenge to aggressive incidents Campaign of Concern: witnessing by family supporters Tailing and Telephone Round: parents and supporters increase their presence in dangerous places outside the home.

The Need for Support in Parents – Alliances between adults reverse blaming patterns and splitting between adults. – Supporters become interpersonal resources – they help parents stay grounded in planning and carrying out presence- raising direct action, instead of remaining mired in agonising about the problem – Direct action itself enables parents to stand up to their own anxiety and become de-sensitised.

The Support Network • NVR actively promotes alliances between adults. Parents, relatives, carers, teachers and community members are no longer isolated from each other in responding to aggressive behaviour. They take part in presence-raising action together. • The young person’s behaviour is made transparent within the support network. • The adults’ responses are made transparent within the support network. This is part of the ‘New Authority’, which raises the adults’ legitimacy and credibility.

Supporter Roles – Witness: witnesses violence, e. g. in a sit-in or announcement – Buffer: help diffuse an escalating situation by coming to the home or giving the young person respite in their own home – Campaign of concern: member of the community expresses concern to the young person, whenever there has been an incident of violent or destructive behaviour – Logistic supporter: takes pressure off parents, e. g. looking after younger children during a sit-in, cooking a meal for the family… – Mentor: an ‘NVR graduate’ who can give advice, help parents stay calm, give them hope – Sibling support: helps protect a targeted sibling by regularly checking in with them and informing parents of any incidents of victimisation – Mediator: Helps parents and aggressive child negotiate solutions, e. g. agreements about reparation, restorative justice or new rules.

• Whether in foster care, residential homes, adopted or living in their birth families, children who have been abused and neglected are among those with the greatest unmet psychological need. Those previously abused children who become violent or self-destructive, are also among the most dismissive, when adults in their lives attempt to care for them. • Others, who have not suffered child abuse, and are nonetheless violent, are equally dismissive of the adults’ attempts to care for them. When the caring dialogue between adult and child diminishes, the young person’s unmet need grows. • The ideas in this presentation have been developed by working with NVR in families with violent children, who have experienced developmental trauma. Their aim is to facilitate the renewal of the caring dialogue, which has been eclipsed

Unmet needs and the unheard voice of distress in the aggressive child • The need to feel safe and protected – Attachment and security – Post-traumatic stress and anxiety • The need for support in one’s development • The need to feel a sense of belonging • The need for a coherent and benign narrative of self and family

The Anchoring Function of Attachment and the Position of Parental Strength • In order to develop a sense of safety in relation to their parents, children need to experience their parents as strong – only a strong parent will be able to protect and support me. • Parents cannot attune, empathise and provide care when they feel threatened, dismissed, confused and helpless. They need to acquire a position of strength, in order to overcome survival reactivity. • Parents then become able to re-sensitise themselves to their child’s needs.

I will keep reaching out to you, no matter what you do… Reconciliation Gestures as Relational Gestures • Reconciliation gestures- acts of unconditional love and care, that reassure the young person: “We care about you”. Instead of saying “we love you, we just don’t like what you do”, parents act. Acts speak louder than words. • Reconciliation gestures can communicate a parent’s or carer’s awareness of the child’s unmet need and distress. Planning reconciliation gestures helps parents and carers focus on the child’s unmet needs and become re-sensitized to their distress. This process can re-kindle the caring dialogue.

What thoughts and feelings does this internal image trigger inside of you?

And what thoughts and feelings does this image trigger inside of you?

Child Focused Reconciliation Gestures • Draw the parents’ attention to unmet child needs, where parents have developed care block and children do not yet express their distress. • Imaginary methods enable caregivers to visualise a future with a caring dialogue, in which they are attuned to the child, the child signals distress when their needs are not met, the adults take caring action and the child can feed back the results of this action: – Prepare reconciliation gestures by interviewing the ‘internalised child in distress’ in the parent – Engage adults in an ‘imaginary caring dialogue’ Parents carry out child-focused reconciliation gestures without expecting validation or positive responses.

Child Focus Toolbox for Planning Relational Reconciliation Gestures • Incorporating parental apology and preferred future in the announcement. • Using the imaginary care dialogue to help caregivers plan reconciliation gestures. • Using visualisation to help parents merge the image of the controlling child with the image of the child in need. • Interviewing the ‘internalised child in distress’ in the parent • Holding therapeutic network meetings, at which an advocate for the child can inform parents and NVR therapist about unmet needs. • Seeing the child in parallel to the parents. • Seeing the child together with the parents in family therapy after the controlling behaviour has diminished

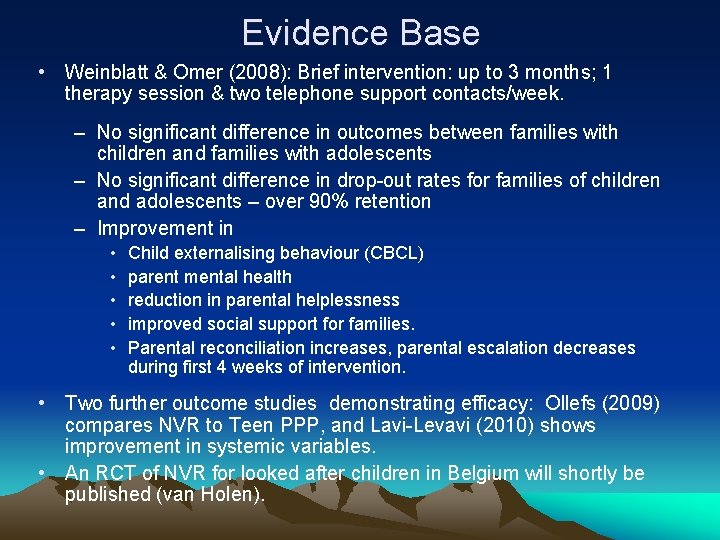

Evidence Base • Weinblatt & Omer (2008): Brief intervention: up to 3 months; 1 therapy session & two telephone support contacts/week. – No significant difference in outcomes between families with children and families with adolescents – No significant difference in drop-out rates for families of children and adolescents – over 90% retention – Improvement in • • • Child externalising behaviour (CBCL) parent mental health reduction in parental helplessness improved social support for families. Parental reconciliation increases, parental escalation decreases during first 4 weeks of intervention. • Two further outcome studies demonstrating efficacy: Ollefs (2009) compares NVR to Teen PPP, and Lavi-Levavi (2010) shows improvement in systemic variables. • An RCT of NVR for looked after children in Belgium will shortly be published (van Holen).

References • Jakob, P. (2014). Non-violent resistance and ADHD in Practice 6/2, pp 7 -11 • Jakob, P. (2011). Re-connecting parents and young people with serious behaviour problems - child-focused practice and reconciliation work in non violent resistance therapy. New Authority Network International, available at: www. newathority. net • Jakob, P. , Wilson, J. and Newman, M (2014). Non-violence and a focus on the child: a UK perspective. Context 132, pp. 37 -41. • Jakob, P. & Shapiro, M. (2014). Overcoming aggression, harm and the dependence trap: Non Violent Resistance in families with a child on the autism spectrum. In G. Jones & E. Hurley: Good autism practice. Autism, happiness and wellbeing. Glasgow: BILD • Lebowitz, E. R. & Omer, H. (2013). Treating childhood and adolescent anxiety. A guide for caregivers. Hoboken: Wiley • Omer, H. (2004). Nonviolent resistance: A new approach to violent and self-destructive children. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. • Omer, H. (2011/1) The new authority: family, school, community. Cambridge University Press.

References for evidence base • Gleniusz, B. (2014). Examining the evidence for the non-violent resistance approach as an effective treatment for adolescents with conduct disorder. Context 132, pp 42 -44. • Jonkman, C. S, Van der Soet, K, Van Gink, N, Godard, N, Van der Stegen, B. & Lindauer, R. J. L. : The effects of nonviolent resistance in a child and adolescent psychiatric ward setting. Unpublished manuscript. • Lavi-Levavi, I. (2010). Improvement in systemic intra- familial variables by "Non- Violent Resistance" treatment for parents of children and adolescents with behavioral problems, Ph. D dissertation, Tel- Aviv University, Tel Aviv. • Newman, M, Fagan, C & Webb, R (2013). The efficacy fo nonviolent resistance groups in treating aggressive and controlling behaviour in children and young people: a preliminary analysis of pilot NVR groups in Kent. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 19/2, pp 138 -141 • Ollefs, B. , Von Schlippe, A. , Omer, H. , and Kriz, J. (2009) Adolescents showing externalising problem behaviour. Effects of parent coaching (German). Familiendynamik, 3: 256 -265. • Van Holen, F. (2014). Looked after children; In print. • Weinblatt, U. & Omer, H. (2008). Non-violent resistance: A treatment for parents of children with acute behavior problems. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 34, pp. 75 -92.

Websites • www. newauthority. net • General information, articles on NVR, and discussion forums. • www. nvrpsy. com – General information, articles on NVR. Copy of April 2014 issue of ‘Context’ for downloading. • www. partnershipprojectsuk. com – General information on NVR, training courses and events in the UK.

promoting new service models in social care, camhs and education Partnership. Projects (UK) Ltd Pepperstitch Cottage Bishopstone Seaford, UK BN 25 2 UG info@Partnership. Projects. UK. com training@Partnership. Projects. UK. com referrals@Partnership. Projects. UK. com www. Partnership. Projects. UK. com