NIGERCONGO LANGUAGES IN AKWA IBOM STATE A COMPARISON

NIGER-CONGO LANGUAGES IN AKWA IBOM STATE: A COMPARISON AND RECONSTRUCTION OF PROTO-FORMS. AKPAN, OKOKON UDO & OKON, EMMANUEL AKANINYENE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS & NIGERIAN LANGUAGES UNIVERSITY OF UYO, AKWA IBOM STATE, NIGERIA okokonakpan@uniuyo. edu. ng & akanokon. eo@gmail. com

INTRODUCTION • Akwa Ibom State is a political enclave at the South Eastern corner of Nigeria Urua (200 O) with 31 L. G. As. out of which fourteen of them speak Ibibio as a language. • About 4 million people speak Ibibio Essien (1990) and Urua (2000) • It is true that all languages change through time. How they change and what kind of changes one can expect are not always obvious. • By comparing between and among languages or speech forms, the history of a group or speech forms can be discovered in addition to ascertaining their genetic relationships. • A language where speakers loose contact with one another can eventually evolve into numerous distinct languages. • To establish that a pair of languages are genetically related, one needs to demonstrate that there are recurring sound correspondences among the words in the languages so compared which have roughly the same meaning and belong to the basic vocabulary. The more such sound correspondences recur, the stronger the genetic relationship.

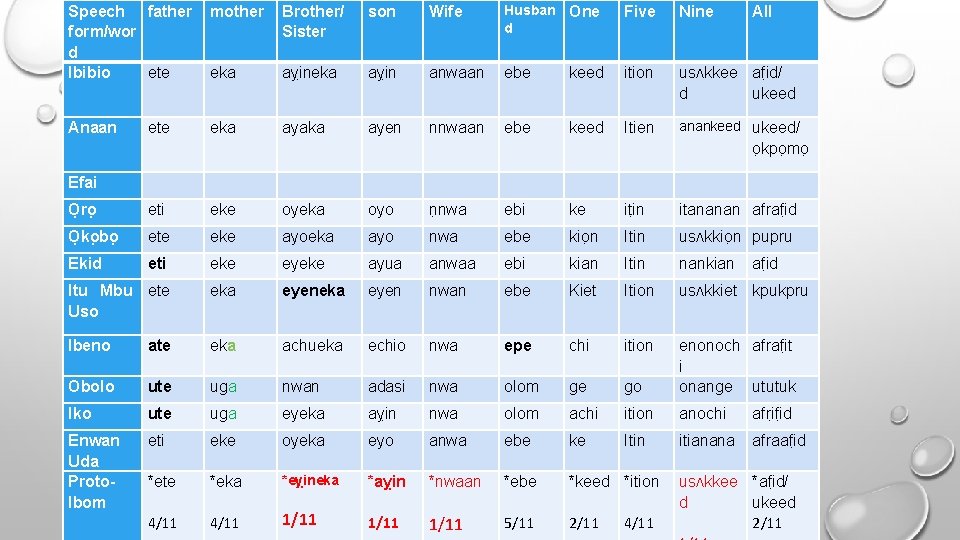

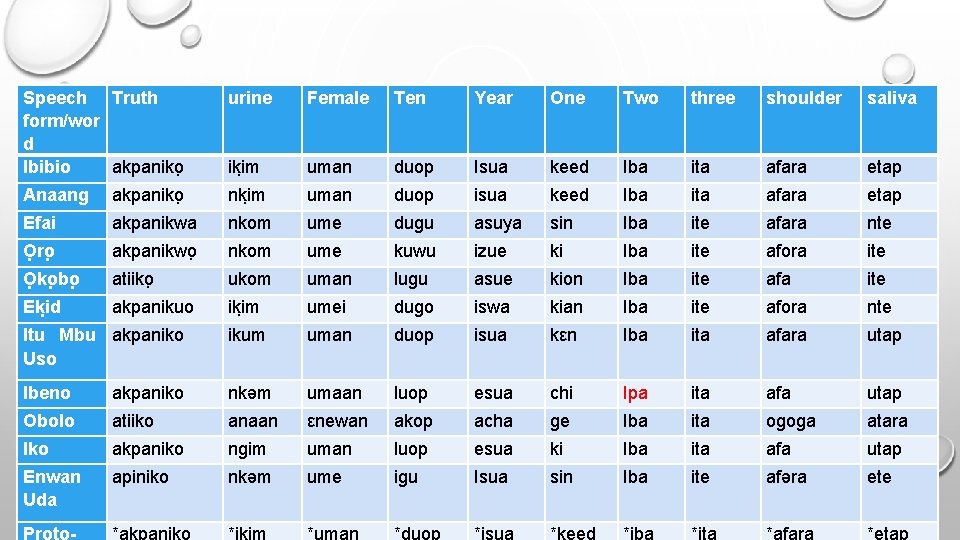

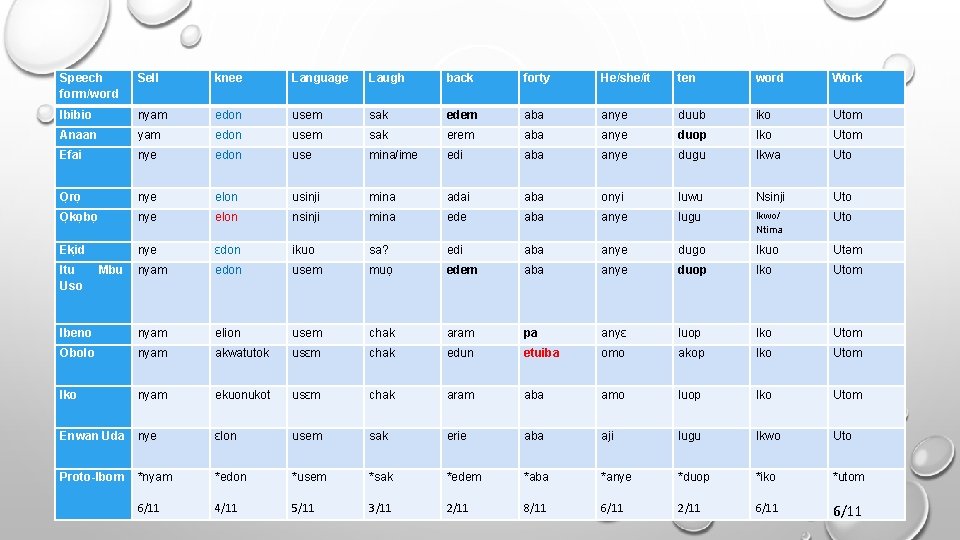

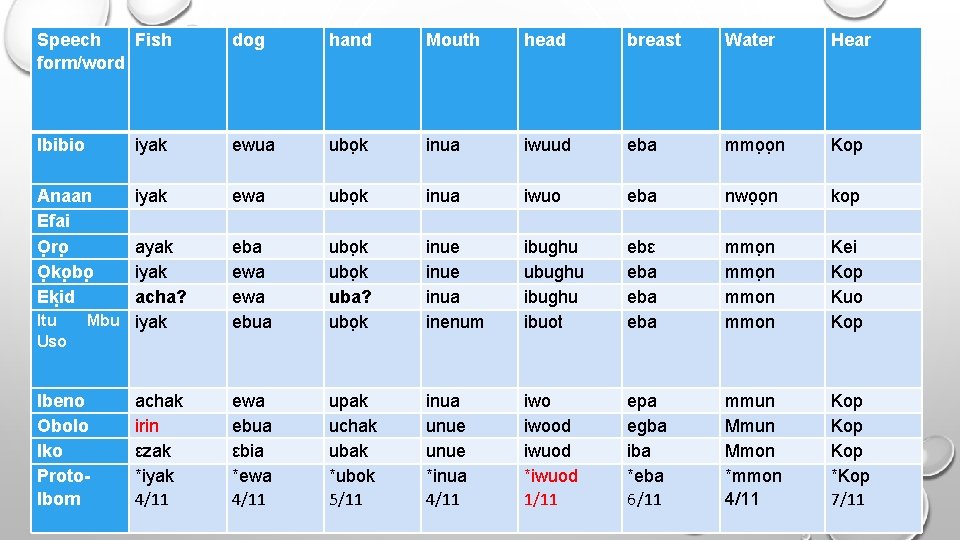

SCOPE OF THE PAPER • This paper is restricted to the analysis of such similarities in the basic vocabulary and the phonological correspondences. • The basic vocabulary items such as words for kinship (e. g. Ibibio – ete, Obolo – ute, Ekid – eti, Ibeno – ate, Anaan – ete Okobo – ete, Oro – eti, etc) meaning father, daily activities or experiences, parts of the body, natural phenomena and, • A few occasional strays on morphological features of the proto-form would be considered.

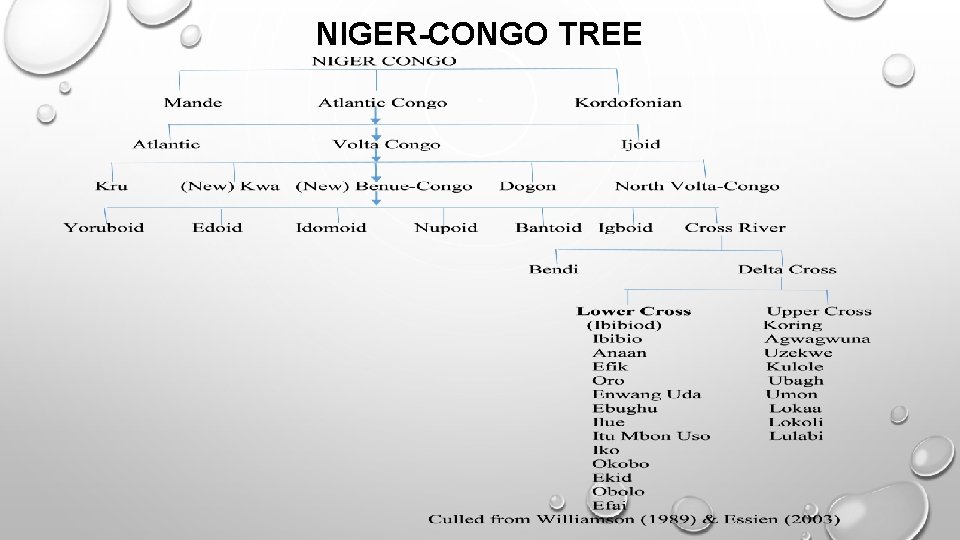

BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON NIGERCONGO LANGUAGE FAMILY • Niger-Congo languages constitute one of the world’s major language families and Africa’s largest in terms of geographical area, number of speakers, and number of distinct languages. • Grimmes (1996) estimates Niger-Congo languages in the neighbourhood of 1, 436. • This figure is also supported by williamson and Blench (2000). • Williamson and Blench (2000) say that some of the languages in Africa with the greatest number of speakers belong to Niger-Congo, • Akan, the largest language of Ghana; Yoruba, Hausa and Igbo - major languages of Nigeria. • Swahili is the most widely spoken in Afirca.

BASIC FEATURES OF NIGER-CONGO PHYLUM • A common characteristics of Niger-Congo phylum is its elaborate noun class system which marks singular/plural alternations with affixes mostly prefixes. Other noticeable characteristics of Niger-Congo also include verbal extensions and basic lexicon. • Phonologically, languages of this family often show vowel harmony on the size of the pharynx, controlled by advancement or retraction of the root of the tongue and raising or lowering of the larynx (Ladefoged 1964, Steward 1967, Lindau 1975). • The expanded or [+ATR] vowels are /i, e, з, o, u/ and the non-expanded or [-ATR] ones are /i, ε a, ə, մ/. it is also common to find systems which lack /з/ and in which /a/ is opaque.

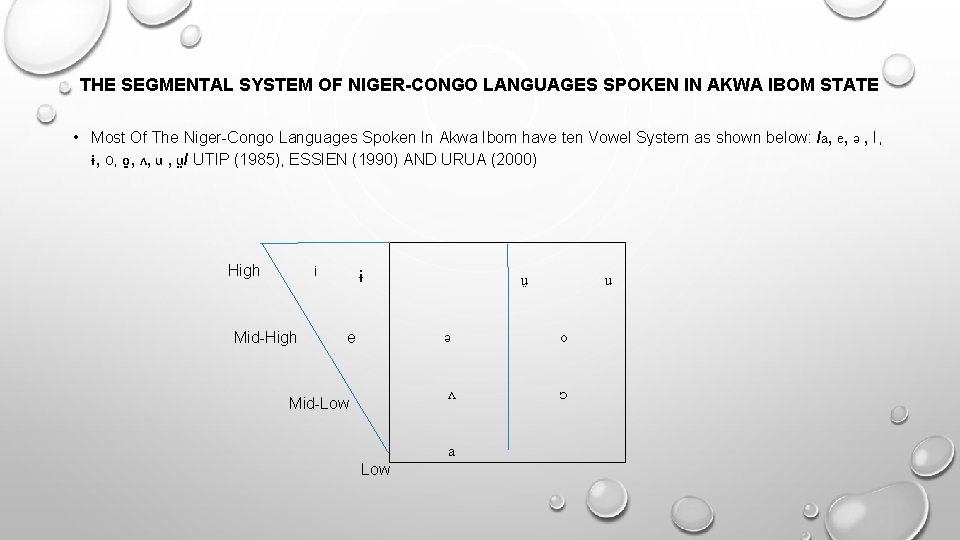

THE SEGMENTAL SYSTEM OF NIGER-CONGO LANGUAGES SPOKEN IN AKWA IBOM STATE • Most Of The Niger-Congo Languages Spoken In Akwa Ibom have ten Vowel System as shown below: /a, e, ə , I, ɨ, o, ọ , ʌ, u , ụ / UTIP (1985), ESSIEN (1990) AND URUA (2000) High i ɨ ṳ u Mid-High e ə o Mid-Low ʌ a Low ᴐ

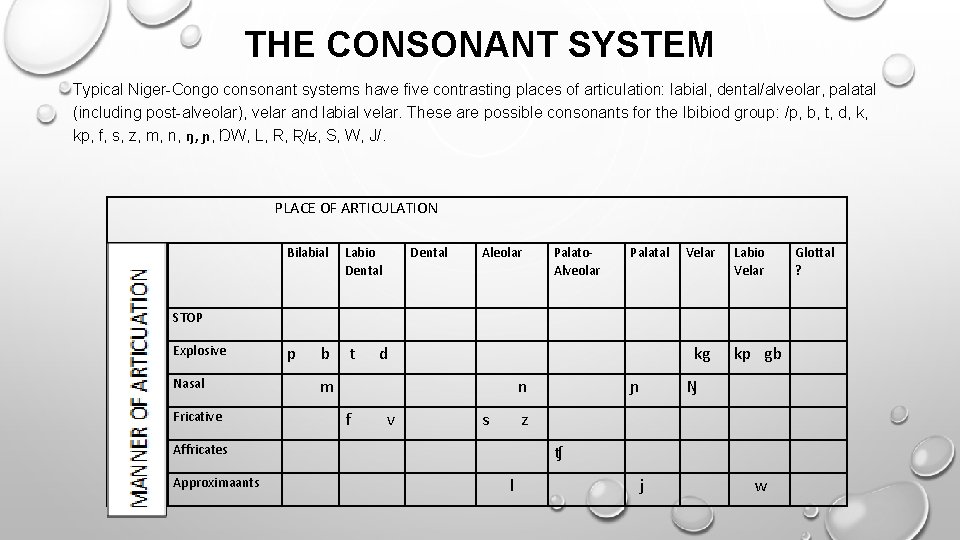

THE CONSONANT SYSTEM Typical Niger-Congo consonant systems have five contrasting places of articulation: labial, dental/alveolar, palatal (including post-alveolar), velar and labial velar. These are possible consonants for the Ibibiod group: /p, b, t, d, k, kp, f, s, z, m, n, ŋ, ɲ, ŊW, L, R, Ʀ/ʁ, S, W, J/. PLACE OF ARTICULATION Bilabial Labio Dental Aleolar Palato. Alveolar Palatal Velar Labio Velar Glottal ? STOP Explosive p b t d kg kp gb Nasal m n ɲ Ŋ Fricative f v s z Affricates ʧ Approximaants l j w

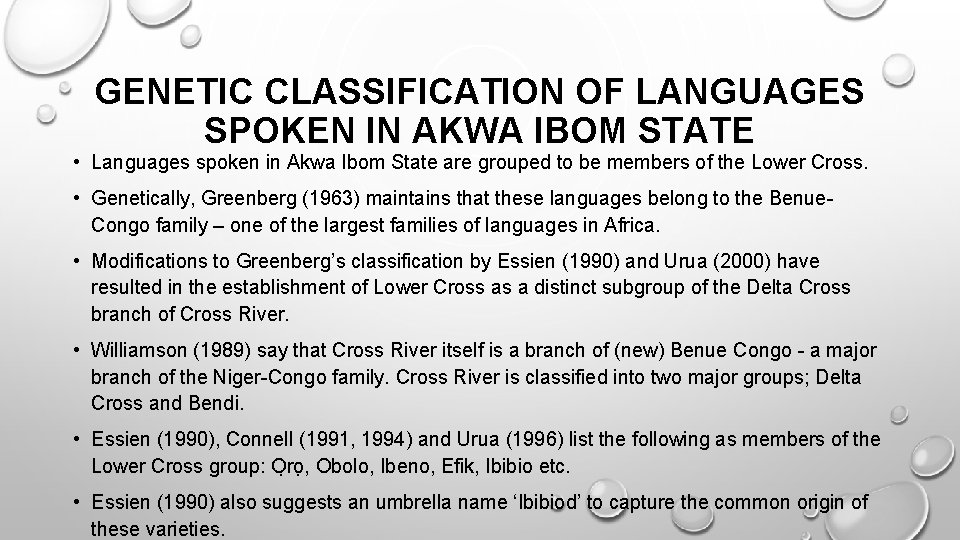

GENETIC CLASSIFICATION OF LANGUAGES SPOKEN IN AKWA IBOM STATE • Languages spoken in Akwa Ibom State are grouped to be members of the Lower Cross. • Genetically, Greenberg (1963) maintains that these languages belong to the Benue- Congo family – one of the largest families of languages in Africa. • Modifications to Greenberg’s classification by Essien (1990) and Urua (2000) have resulted in the establishment of Lower Cross as a distinct subgroup of the Delta Cross branch of Cross River. • Williamson (1989) say that Cross River itself is a branch of (new) Benue Congo - a major branch of the Niger-Congo family. Cross River is classified into two major groups; Delta Cross and Bendi. • Essien (1990), Connell (1991, 1994) and Urua (1996) list the following as members of the Lower Cross group: O ro , Obolo, Ibeno, Efik, Ibibio etc. • Essien (1990) also suggests an umbrella name ‘Ibibiod’ to capture the common origin of these varieties.

LANGUAGE AND DIALECT • Language is an invaluable possession of the human race. It also means speech habit of a given people, a symbol of identity and a site for social interaction. • Fromkin and Rodman (1974: 252) ‘dialects are mutually intelligible versions of the same basic grammar, with systematic differences’. • These dialects or speech forms are what Essien (1986) refer to as smaller tongues such as Anaan, O ro , O ko bo , Eki d, Ibeno, Obolo, Itu Mbon Uso , Iko etc.

NIGER-CONGO TREE

POINT TO NOTE • All the listed speech forms are independent forms. • The fact that they share a considerable and high degree of lexical items, a variety of phonological, morphological, and syntactic features, as well as, a great deal of mutual intelligibility with each other does not suggest any form of dependency on any of these languages for survival. • Hegemony status of English - members of this group are playing a complementary role to the English language. • A great deal of the Lower Cross speech forms is threatened with varying degrees of extinction. • Speakers’ attitude and government policies on language matters.

PRINCIPLES FOR TRACING PROTOLANGUAGE • . A. THE ‘MAJORITY PRINCIPLE’ is very straight forward. • If in a cognate set, three words begin with a [p] sound and one word begins with a [b] sound, then our best guess is that the majorities have retained the original sound [p] and the minorities have changed a little through time. • B. THE ‘MOST NATURAL PRINCIPLE’. This principle is based on the fact that certain types of sound changes are extremely unlikely. The direction of change described in each case (1) - (4) below has been commonly observed, but the reverse has not. • 1. Final vowels often disappear (vino-vin) • 2. Stops become nasal medially (nduk in Oro vs nnuk in Itu Mbon Uso) • 2. Voiceless sounds become voiced, typically between vowels (muta-muda) • 3. Stops become fricatives (ripa-riva) • 4. Consonants become voiceless word finally (Ibibio ebe versus Ibeno epe) ‘husband’. • 5. Alveolar becomes lateral in (Ibibio edon vs Okobo elon

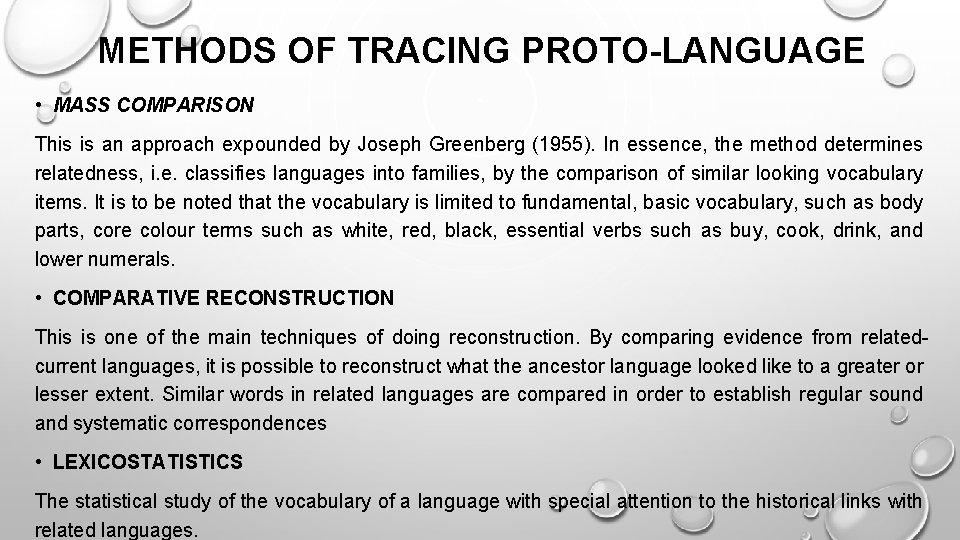

METHODS OF TRACING PROTO-LANGUAGE • MASS COMPARISON This is an approach expounded by Joseph Greenberg (1955). In essence, the method determines relatedness, i. e. classifies languages into families, by the comparison of similar looking vocabulary items. It is to be noted that the vocabulary is limited to fundamental, basic vocabulary, such as body parts, core colour terms such as white, red, black, essential verbs such as buy, cook, drink, and lower numerals. • COMPARATIVE RECONSTRUCTION This is one of the main techniques of doing reconstruction. By comparing evidence from relatedcurrent languages, it is possible to reconstruct what the ancestor language looked like to a greater or lesser extent. Similar words in related languages are compared in order to establish regular sound and systematic correspondences • LEXICOSTATISTICS The statistical study of the vocabulary of a language with special attention to the historical links with related languages.

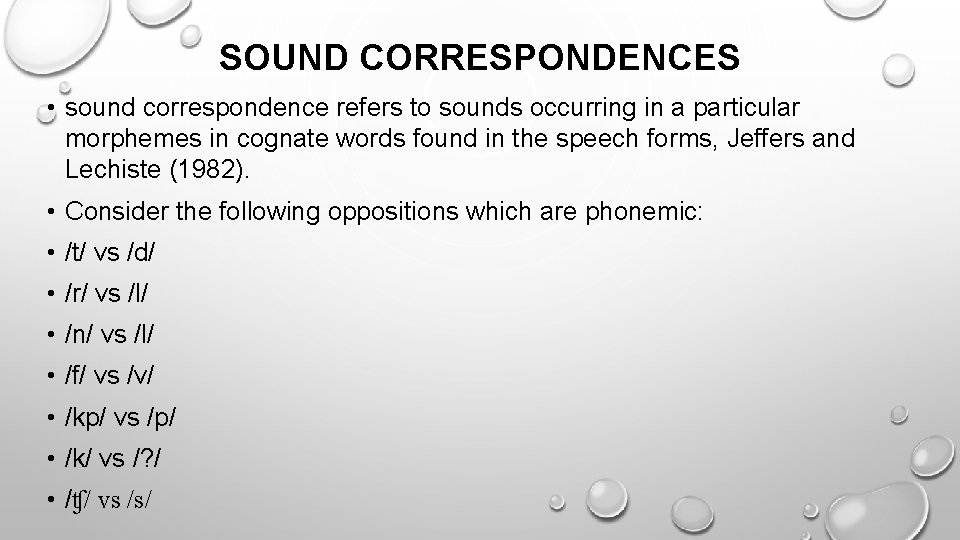

SOUND CORRESPONDENCES • sound correspondence refers to sounds occurring in a particular morphemes in cognate words found in the speech forms, Jeffers and Lechiste (1982). • Consider the following oppositions which are phonemic: • /t/ vs /d/ • /r/ vs /l/ • /n/ vs /l/ • /f/ vs /v/ • /kp/ vs /p/ • /k/ vs /? / • /ʧ/ vs /s/

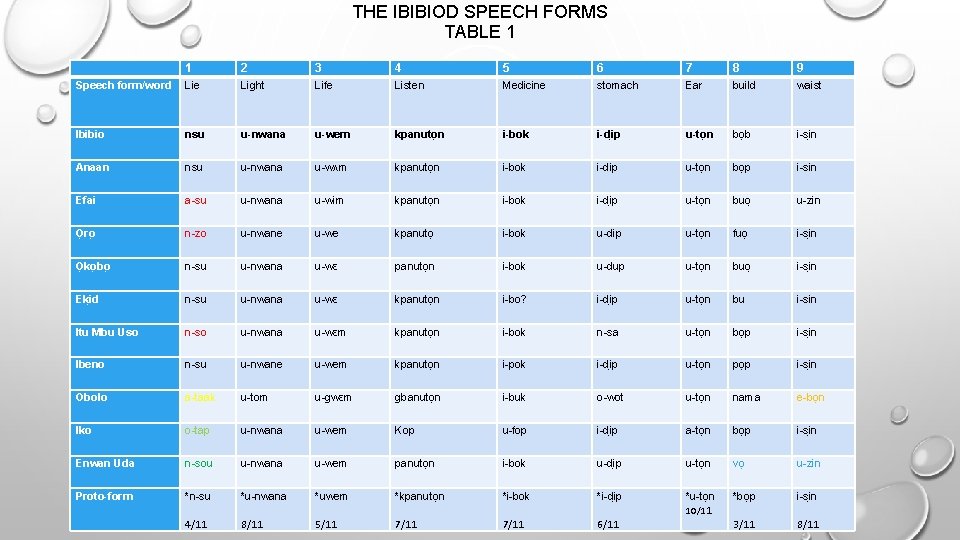

THE IBIBIOD SPEECH FORMS TABLE 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Speech form/word Lie Light Life Listen Medicine stomach Ear build waist Ibibio nsu u-nwana u-wem kpanuto n i-bok i-di p u-to n bo b i-si n Anaan nsu u-nwana u-wʌm kpanuto n i-bok i-dip u-to n bo p i-sin Efai a-su u-nwana u-wim kpanuto n i-bok i-di p u-to n buo u-zin O ro n-zo u-nwane u-we kpanuto i-bok u-dip u-to n fuo i-si n O ko bo n-su u-nwana u-wε panuto n i-bok u-dup u-to n buo i-si n Eki d n-su u-nwana u-wε kpanuto n i-bo? i-di p u-to n bu i-sin Itu Mbu Uso n-so u-nwana u-wεm kpanuto n i-bok n-sa u-to n bo p i-si n Ibeno n-su u-nwane u-wem kpanuto n i-pok i-di p u-to n po p i-si n Obolo a-taak u-tom u-gwεm gbanuto n i-buk o-wot u-to n nama e-bo n Iko o-tap u-nwana u-wem Kop u-fop i-di p a-to n bo p i-si n Enwan Uda n-sou u-nwana u-wem panuto n i-bok u-di p u-to n vo u-zin Proto-form *n-su *u-nwana *uwem *kpanuto n *i-bok *i-di p *u-to n 10/11 *bo p i-si n 4/11 8/11 5/11 7/11 6/11 3/11 8/11

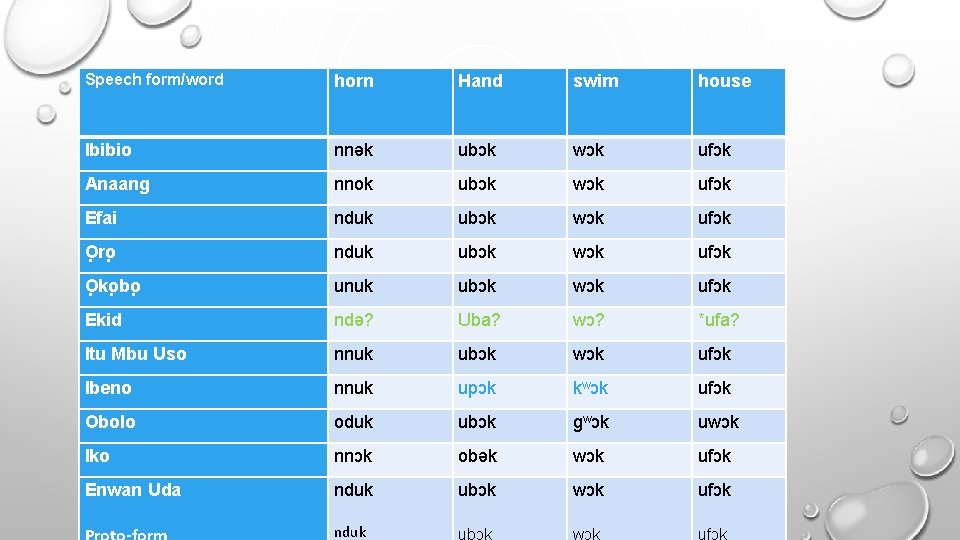

Speech form/word horn Hand swim house Ibibio nnək ubᴐk wᴐk ufᴐk Anaang nnok ubᴐk wᴐk ufᴐk Efai nduk ubᴐk wᴐk ufᴐk O ro nduk ubᴐk wᴐk ufᴐk O ko bo unuk ubᴐk wᴐk ufᴐk Ekid ndə? Uba? wᴐ? *ufa? Itu Mbu Uso nnuk ubᴐk wᴐk ufᴐk Ibeno nnuk upᴐk kwᴐk ufᴐk Obolo oduk ubᴐk gwᴐk uwᴐk Iko nnᴐk obək wᴐk ufᴐk Enwan Uda nduk ubᴐk wᴐk ufᴐk nduk

Speech father form/wor d Ibibio ete mother Brother/ Sister son Wife Husban One d Five Nine eka ayi n anwaan ebe keed ition usʌkkee afi d/ d ukeed Anaan eka ayaka ayen nnwaan ebe keed Itien anankeed ukeed/ ete All o kpo mo Efai O ro eti eke oyeka oyo n nwa ebi ke iti n itananan afrafi d O ko bo ete eke ayoeka ayo nwa ebe kio n Itin usʌkkio n pupru Ekid eti eke eyeke ayua anwaa ebi kian Itin nankian Itu Mbu ete Uso eka eyen nwan ebe Kiet Ition usʌkkiet kpukpru Ibeno ate eka achueka echio nwa epe chi ition Obolo ute uga nwan adasi nwa olom ge go enonoch afrafi t i onange ututuk Iko ute uga eyeka ayi n nwa olom achi ition anochi afri fi d Enwan Uda Proto. Ibom eti eke oyeka eyo anwa ebe ke Itin itianana afraafi d *ete *eka *eyi neka *ayi n *nwaan *ebe *keed *ition 4/11 1/11 5/11 2/11 4/11 afi d usʌkkee *afi d/ d ukeed 2/11

Speech Truth form/wor d Ibibio akpaniko urine Female Ten Year One Two three shoulder saliva iki m uman duop Isua keed Iba ita afara etap Anaang akpaniko nki m uman duop isua keed Iba ita afara etap Efai akpanikwa nkom ume dugu asuya sin Iba ite afara nte O ro akpanikwo nkom ume kuwu izue ki Iba ite afora ite O ko bo atiiko ukom uman lugu asue kion Iba ite afa ite Eki d akpanikuo iki m umei dugo iswa kian Iba ite afora nte Itu Mbu akpaniko Uso ikum uman duop isua kεn Iba ita afara utap Ibeno akpaniko nkəm umaan luop esua chi Ipa ita afa utap Obolo atiiko anaan εnewan akop acha ge Iba ita ogoga atara Iko akpaniko ngim uman luop esua ki Iba ita afa utap Enwan Uda apiniko nkəm ume igu Isua sin Iba ite afəra ete

Speech form/word Sell knee Language Laugh back forty He/she/it ten word Work Ibibio nyam edon usem sak edem aba anye duub iko Utom Anaan yam edon usem sak erem aba anye duop Iko Utom Efai nye edon use mina/ime edi aba anye dugu Ikwa Uto O ro nye elon usinji mina adai aba onyi luwu Nsinji Uto O ko bo nye elon nsinji mina ede aba anye lugu Ikwo/ Ntima Uto Eki d nye εdon ikuo sa? edi aba anye dugo Ikuo Utəm Mbu nyam edon usem muo edem aba anye duop Iko Utom Ibeno nyam elion usem chak aram pa anyε luop Iko Utom Obolo nyam akwatutok usεm chak edun etuiba omo akop Iko Utom Iko nyam ekuonukot usεm chak aram aba amo luop Iko Utom Enwan Uda nye εlon usem sak erie aba aji lugu Ikwo Uto Proto-Ibom *nyam *edon *usem *sak *edem *aba *anye *duop *iko *utom 6/11 4/11 5/11 3/11 2/11 8/11 6/11 2/11 6/11 Itu Uso

Speech Fish form/word dog hand Mouth head breast Water Hear Ibibio ewua ubo k inua iwuud eba mmo o n Kop ewa eba ewa ebua ubo k uba? ubo k inua inue inua inenum iwuo ibughu ubughu ibuot eba ebε eba eba nwo o n mmo n mmon kop Kei Kop Kuo Kop ewa ebua εbia *ewa 4/11 upak uchak ubak *ubok 5/11 inua unue *inua 4/11 iwood iwuod *iwuod 1/11 epa egba iba *eba 6/11 mmun Mmon *mmon 4/11 Kop Kop *Kop 7/11 iyak Anaan Efai O ro O ko bo Eki d Itu Uso iyak ayak iyak acha? Mbu iyak Ibeno Obolo Iko Proto. Ibom achak irin εzak *iyak 4/11

GENERAL DISCUSSION • The sound patterning of genetically related speech forms usually shows similar or even identical phonological rules or correspondence in sound structure. For ibeno, okobo, and oro, the lateral alveolar /l/ generally correspond to Ibibio /d/ as seen in examples: • The relationship between /l/l and /d/ is that they share the same place of articulation, i. e. The alveolar ridge. • On the other hand, the Anaan /p/ generally corresponds to Ibibio /kp/ • Within the Anaan, there are other lects that behave differently from what seems a Standard variety. The Ukanafun Anaan corresponds to Ibibio /s/ in these examples: uchan vs usan ‘plate’ uchoro vs usoro ceremony etc. • Oro, Okobo and Ekid show a tendency to delete final consonants where Ibibio, Anaan and Ibeno maintain them • A systematic correspondence in the distribution of /k/ in all other speech forms and the glottal stop in Ekid. • The /b/ in all other forms alternates to /p/ in Ibeno in the medial position. • Oro changes to lateral alveolar with other speech forms in the environment of /d/

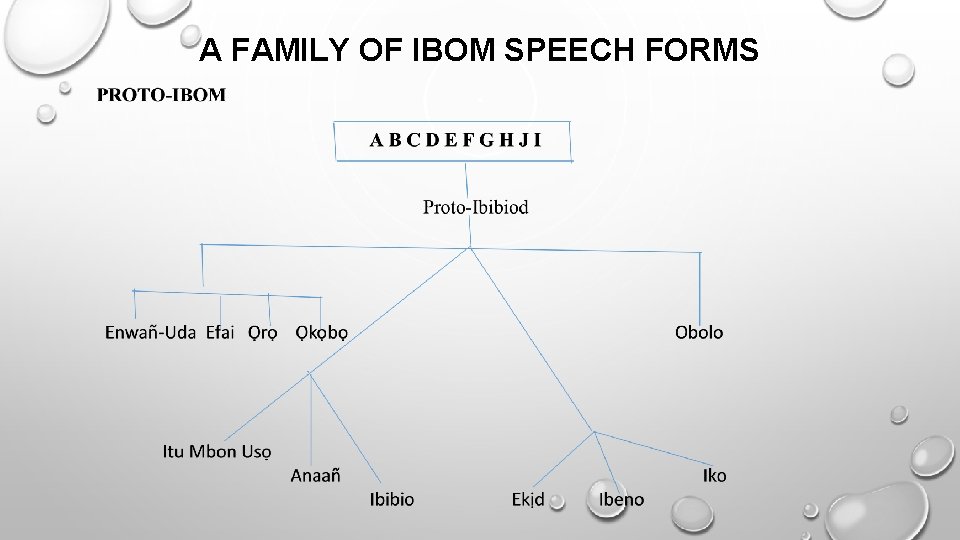

A FAMILY OF IBOM SPEECH FORMS

MORPHOLOGICAL FEATURES • Words in the ibibiod group are grammaticalised with numerous affixes. Certain nouns are inherent while others are derived. • A great number of nouns in the lower cross of Niger-Congo are derived through a process known as nominalization. The following nominalization processes are attestable for these languages Ø Agentive nominalization Here, an a or andi morpheme is prefixed to the verb root as in: mia nduba ‘compete’ – a. mia nduba ‘competitor’ Ø Verbal nominalisation: These are nouns derived from verbs through prefixation. E. g. nem (verb) ‘be sweet’ - i. nem (derived noun) ‘sweetness Ø Gerundive nominalization: A verb with an –ing form. The ‘u’ abstract marker in Ibibio

THE IBIBIO VERBAL SYSTEM • African languages such as ibibio tends to use verbs more frequently than European languages. • Many descriptive adjectives in European language are expressed in verbal forms in some african languages (ibibio) as well as adjectival forms. • The verb has more complex conjugations than any other category. • Tense, aspect, modality abbreviated as TAM by creissels (2000) are commonly marked or grammaticalised in ibibio language as verbal inflections. In ibibio, person as well as negation are always marked on the verb. Therefore, the verb has a rich verbal morphology. Ukaraidem ‘self-governance’ U- abstract nominal bound morpheme Kara (verb) ‘govern or rule’

CONCLUSION • Genetically-related speech forms can be closely related or more distantly related depending on how directly they trace back to a common source. Ibibio and Anaan are closely related speech forms and would be right next to each other as shown in the above tree. • Based on the overt relationship, we submit that Akwa Ibom speech forms are not only genetically related, but must have descended from a common proto-language. • This is also coupled with the experience that the speakers of all other speech forms speak and understand Ibibio with slight lexical variations without learning it formally. • The language therefore becomes the symbol of identity and protection of the people. It also facilitates communication between the people and government. • Feedback from the research reveals that Obolo was the first to break away and it is the most divergent. • While, Ibibio, Anaan and Itu Mbon Uso are the closest. • Speakers of other speech forms speak and understand Ibibio, share common characteristics linguistically, culturally and traditionally. The paper proposes that the proto-form be called Ibibio to reecho Essien’s (1990) proposal. • Minor differences in the Linguistic and cultural tendencies should not be magnified so as to promote unity

/SO SO NO /THANK YOU/MERCI

REFERENCES: • Abasiatai, m. (1991). Women in modern ibibioland. In abasiatai, m. (Ed). The ibibio: an Introduction to the land, the people and their language. Calabar: Paico Press Limited. • Adiakpan, j (2000). The Ekid Speaking People. Lagos: Ok John Nigeria Limited. • Chomsky, n. (1968). Language ad Mind. New York: Harcourt Brace and World Inc. • Connel, b. (1991). Phonetic Aspects of Lower Cross Languages and their Implications for Sound Change. Ph. D. Dissertation. University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh. • Connel, b. (1994). The Lower Cross Languages. A Prolegomena to the Classification of Cross River Languages. Journal of West African Languages vol. Xxiv 1 3 -46 • Egbokhare, f. Et al (2001). Language Clusters in Nigeria. Capetown: the Centre for Advanced Studies of African Society. • Elugbe, b. And a. P. Omanor (1991). Nigerian Pidgin Background and Prospects. Nigeria: Heinemann Educational Books plc. • Essien, o. (1977). The Role of the English Language in our Development. In Akpan, m. B. (Ed. ) African Development Studies. • Essien, o. (1990). A Grammar of Ibibio Language. Ibadan: Ibadan University Press. • Urua, E. (2000). Ibibio Phonetics and Phonology. Cape Town, South Africa: CASAS

- Slides: 27