New Ways of Analysing Syntactic Variation ICLa VE

![Summary of Major Differences [After Cornips & Corrigan 2005 a/b] Variationists: • Speaker representativeness; Summary of Major Differences [After Cornips & Corrigan 2005 a/b] Variationists: • Speaker representativeness;](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/19272b4616f2e8061405cfb01d37aae9/image-5.jpg)

![Summary of Major Differences [After Cornips & Corrigan 2005 a/b] Variationists: Ascertain the significance Summary of Major Differences [After Cornips & Corrigan 2005 a/b] Variationists: Ascertain the significance](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/19272b4616f2e8061405cfb01d37aae9/image-6.jpg)

![Examples of Major Differences: Variationist [After Mishoe & Montgomery 1994: 4] Examples of Major Differences: Variationist [After Mishoe & Montgomery 1994: 4]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/19272b4616f2e8061405cfb01d37aae9/image-9.jpg)

![Examples of Major Differences: Variationist [After Mishoe & Montgomery 1994: 4] Examples of Major Differences: Variationist [After Mishoe & Montgomery 1994: 4]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/19272b4616f2e8061405cfb01d37aae9/image-10.jpg)

![What Else Makes a Modular Approach Necessary? [After Cornips & Corrigan 2005 a/b] What Else Makes a Modular Approach Necessary? [After Cornips & Corrigan 2005 a/b]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/19272b4616f2e8061405cfb01d37aae9/image-28.jpg)

- Slides: 31

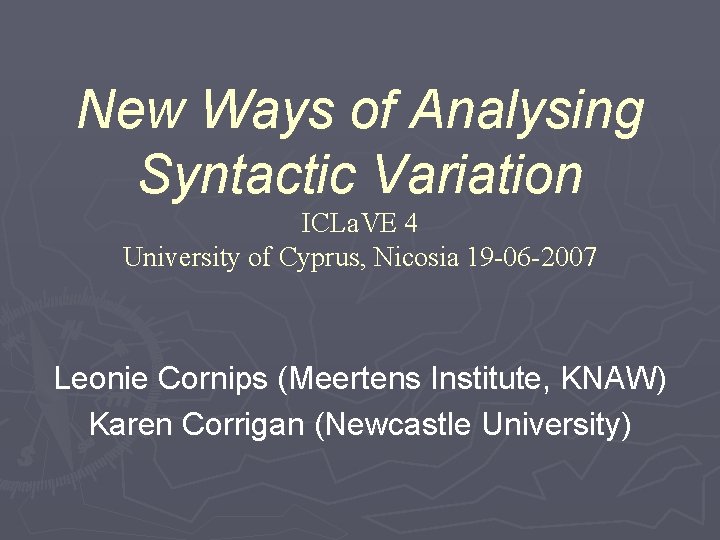

New Ways of Analysing Syntactic Variation ICLa. VE 4 University of Cyprus, Nicosia 19 -06 -2007 Leonie Cornips (Meertens Institute, KNAW) Karen Corrigan (Newcastle University)

Introduction: Aims (1) Review the manner in which morphosyntactic variation is treated by Variationists and Generativists; (2) Develop Wilson and Henry (1998), i. e. combining insights from both models can: (a. ) enhance our understanding of the mechanisms of linguistic variation and change and (b. ) provide new sources of evidence on which analyses within the generative programme of Chomsky (1995) inter alia can be built. (3) To put forward the assumption that interface levels constitute the locus of social, morphosyntactic variation and to propose a modular approach for an integrated theory of syntactic variation (Cornips & Corrigan 2005).

Introduction: Variationists vs. Generativists (1) Points of Congruence: • • Characterisation of variation Locus of Variation (2) Points of Difference: • • Data Methods Analyses Interpretation

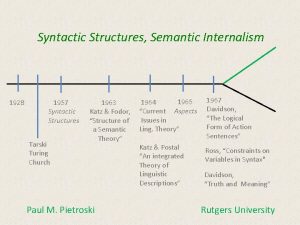

Variationists vs. Generativists

![Summary of Major Differences After Cornips Corrigan 2005 ab Variationists Speaker representativeness Summary of Major Differences [After Cornips & Corrigan 2005 a/b] Variationists: • Speaker representativeness;](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/19272b4616f2e8061405cfb01d37aae9/image-5.jpg)

Summary of Major Differences [After Cornips & Corrigan 2005 a/b] Variationists: • Speaker representativeness; • Controlled recordings; • Collection of substantial quantities of data; • ‘Community’ grammars. Generativists: • Native-speaker introspection; • ‘Individual’ grammars.

![Summary of Major Differences After Cornips Corrigan 2005 ab Variationists Ascertain the significance Summary of Major Differences [After Cornips & Corrigan 2005 a/b] Variationists: Ascertain the significance](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/19272b4616f2e8061405cfb01d37aae9/image-6.jpg)

Summary of Major Differences [After Cornips & Corrigan 2005 a/b] Variationists: Ascertain the significance of inherent variability for a range of socio-cultural correlates with respect to ‘community’ grammars. Generativists: Delimit the set of possible languages and discover the universal constraints by which all ‘individual’ grammars are bound.

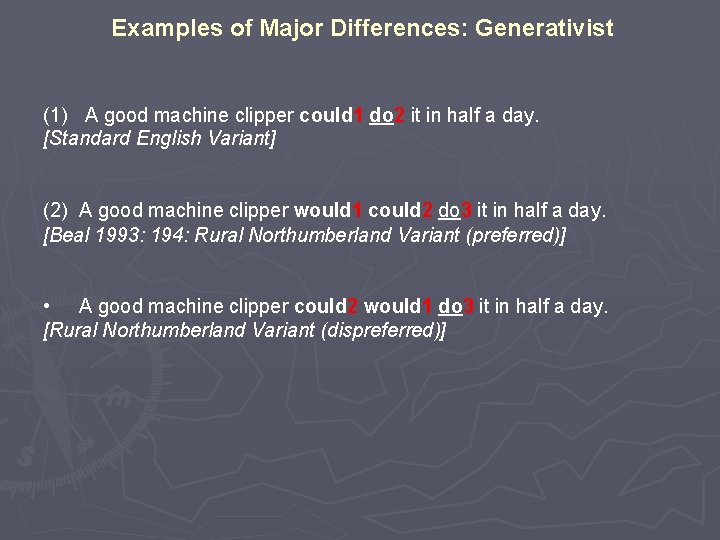

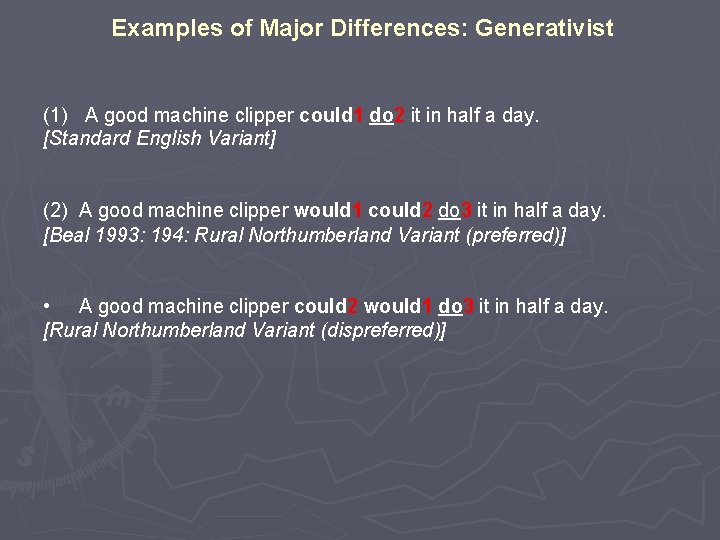

Examples of Major Differences: Generativist (1) A good machine clipper could 1 do 2 it in half a day. [Standard English Variant] (2) A good machine clipper would 1 could 2 do 3 it in half a day. [Beal 1993: 194: Rural Northumberland Variant (preferred)] • A good machine clipper could 2 would 1 do 3 it in half a day. [Rural Northumberland Variant (dispreferred)]

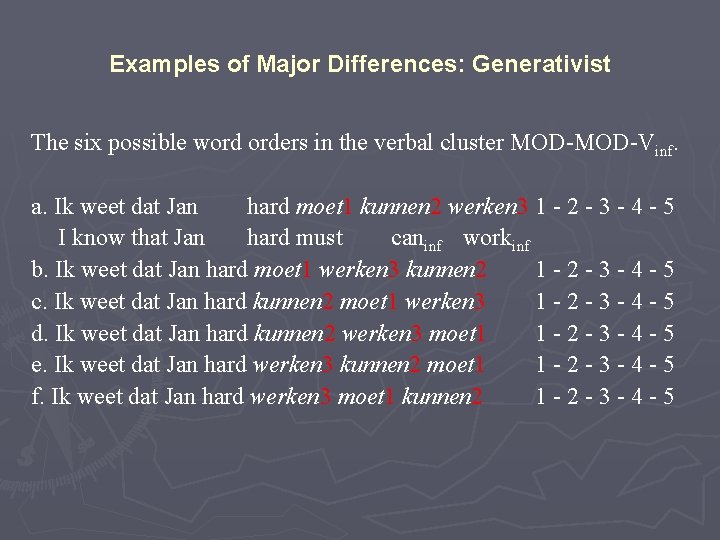

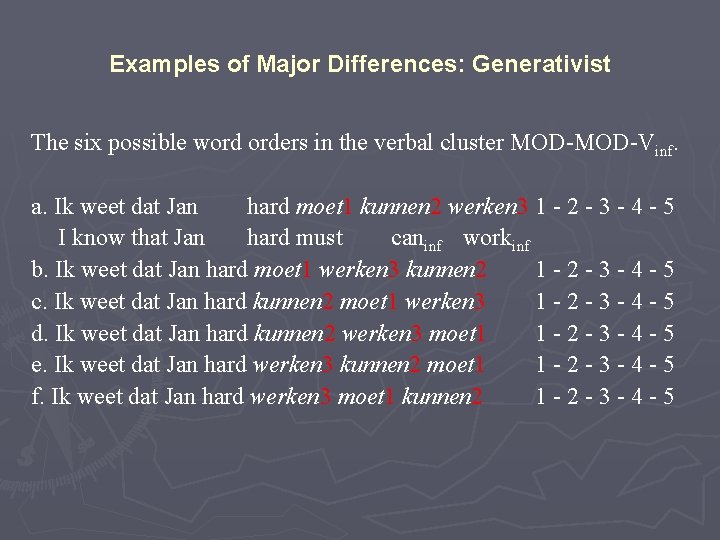

Examples of Major Differences: Generativist The six possible word orders in the verbal cluster MOD-Vinf. a. Ik weet dat Jan hard moet 1 kunnen 2 werken 3 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 I know that Jan hard must caninf workinf b. Ik weet dat Jan hard moet 1 werken 3 kunnen 2 1 -2 -3 -4 -5 c. Ik weet dat Jan hard kunnen 2 moet 1 werken 3 1 -2 -3 -4 -5 d. Ik weet dat Jan hard kunnen 2 werken 3 moet 1 1 -2 -3 -4 -5 e. Ik weet dat Jan hard werken 3 kunnen 2 moet 1 1 -2 -3 -4 -5 f. Ik weet dat Jan hard werken 3 moet 1 kunnen 2 1 -2 -3 -4 -5

![Examples of Major Differences Variationist After Mishoe Montgomery 1994 4 Examples of Major Differences: Variationist [After Mishoe & Montgomery 1994: 4]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/19272b4616f2e8061405cfb01d37aae9/image-9.jpg)

Examples of Major Differences: Variationist [After Mishoe & Montgomery 1994: 4]

![Examples of Major Differences Variationist After Mishoe Montgomery 1994 4 Examples of Major Differences: Variationist [After Mishoe & Montgomery 1994: 4]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/19272b4616f2e8061405cfb01d37aae9/image-10.jpg)

Examples of Major Differences: Variationist [After Mishoe & Montgomery 1994: 4]

Social Stratification of AUX-PAST + PARTICIPLE in Heerlen Dutch (cf. Cornips 2006)

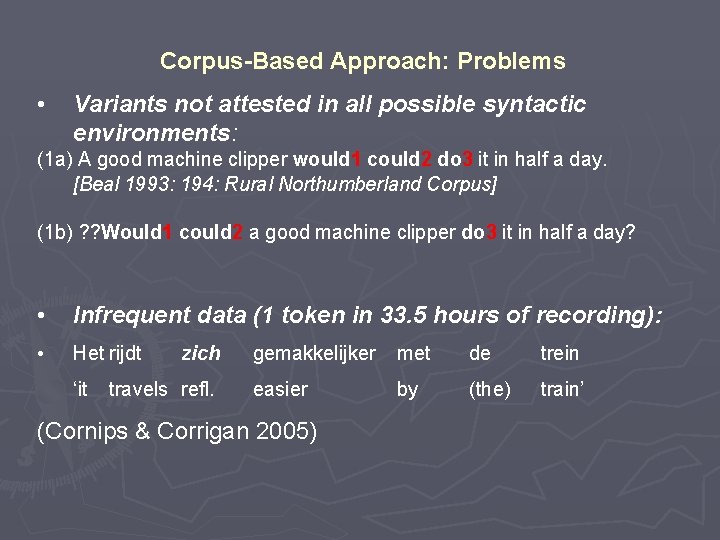

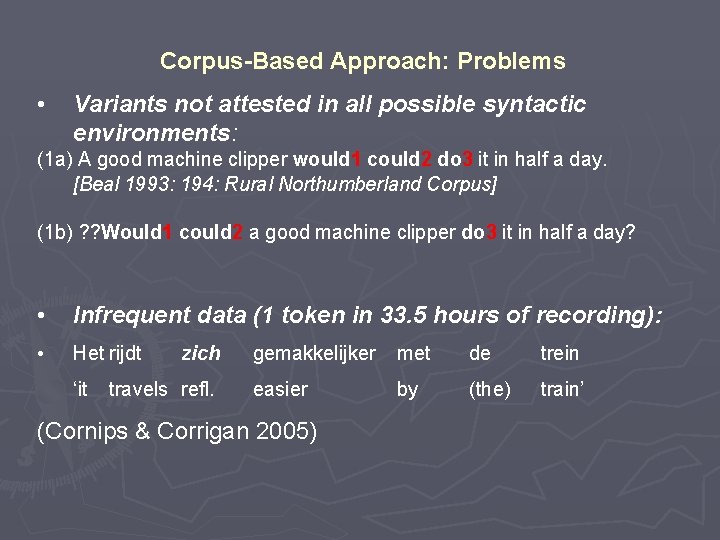

Corpus-Based Approach: Problems • Variants not attested in all possible syntactic environments: (1 a) A good machine clipper would 1 could 2 do 3 it in half a day. [Beal 1993: 194: Rural Northumberland Corpus] (1 b) ? ? Would 1 could 2 a good machine clipper do 3 it in half a day? • Infrequent data (1 token in 33. 5 hours of recording): • Het rijdt ‘it zich travels refl. gemakkelijker met de trein easier by (the) train’ (Cornips & Corrigan 2005)

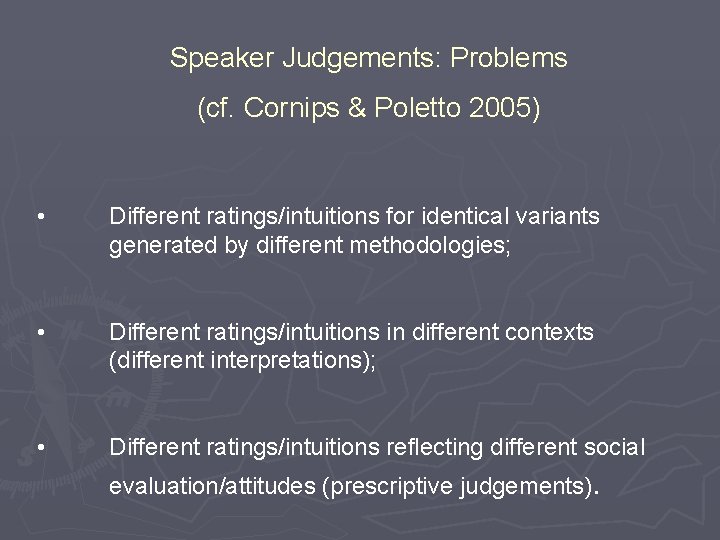

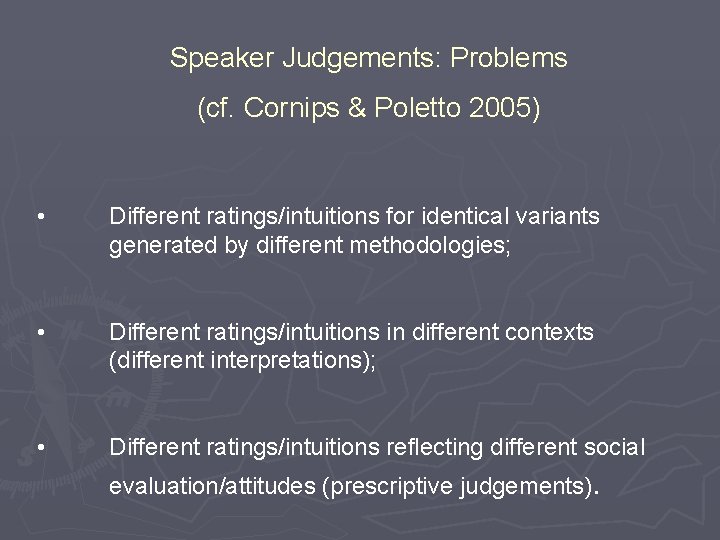

Speaker Judgements: Problems (cf. Cornips & Poletto 2005) • Different ratings/intuitions for identical variants generated by different methodologies; • Different ratings/intuitions in different contexts (different interpretations); • Different ratings/intuitions reflecting different social evaluation/attitudes (prescriptive judgements).

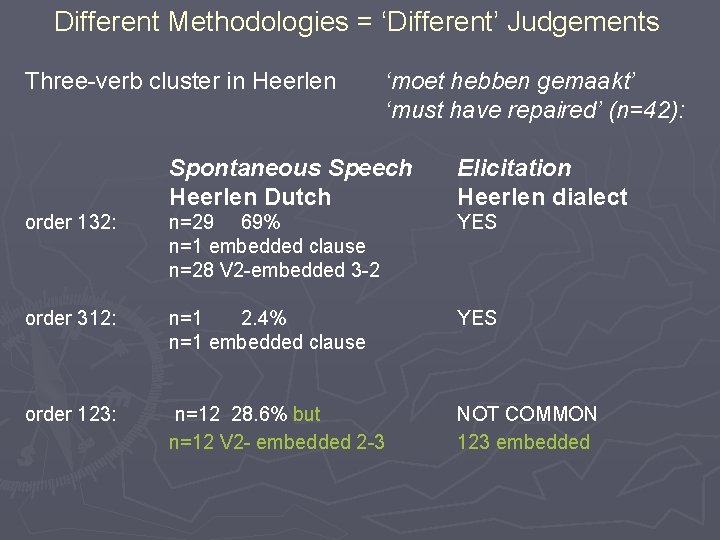

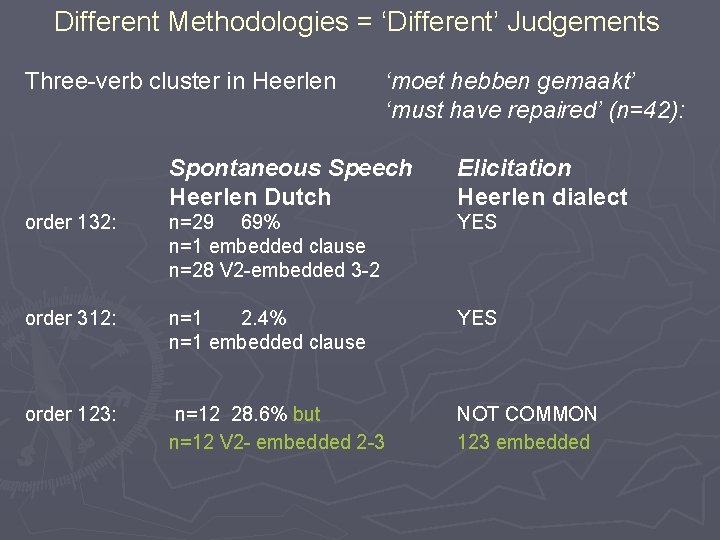

Different Methodologies = ‘Different’ Judgements Three-verb cluster in Heerlen ‘moet hebben gemaakt’ ‘must have repaired’ (n=42): Spontaneous Speech Heerlen Dutch Elicitation Heerlen dialect order 132: n=29 69% n=1 embedded clause n=28 V 2 -embedded 3 -2 YES order 312: n=1 2. 4% n=1 embedded clause YES order 123: n=12 28. 6% but n=12 V 2 - embedded 2 -3 NOT COMMON 123 embedded

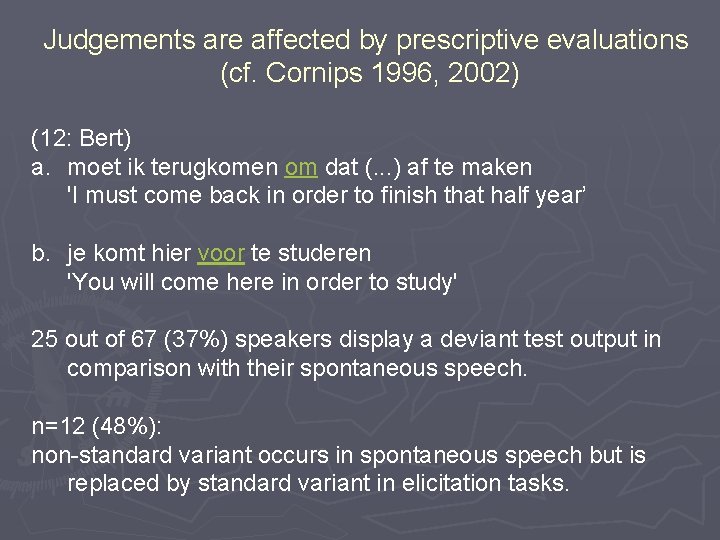

Judgements are affected by prescriptive evaluations (cf. Cornips 1996, 2002) (12: Bert) a. moet ik terugkomen om dat (. . . ) af te maken 'I must come back in order to finish that half year’ b. je komt hier voor te studeren 'You will come here in order to study' 25 out of 67 (37%) speakers display a deviant test output in comparison with their spontaneous speech. n=12 (48%): non-standard variant occurs in spontaneous speech but is replaced by standard variant in elicitation tasks.

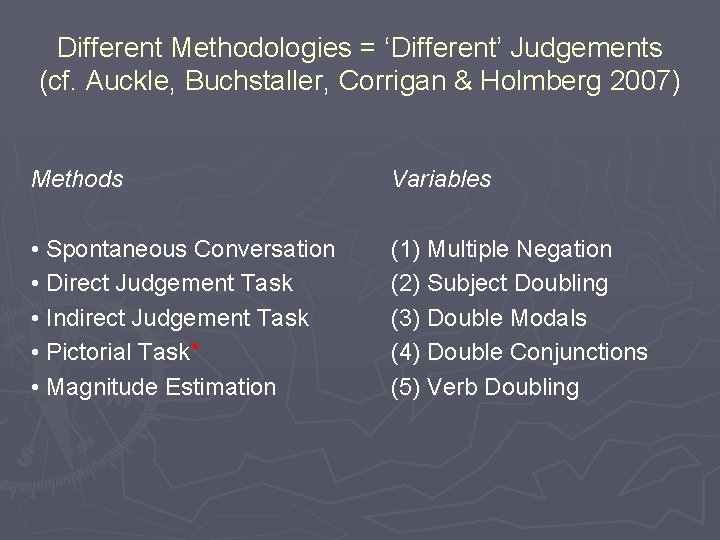

Different Methodologies = ‘Different’ Judgements (cf. Auckle, Buchstaller, Corrigan & Holmberg 2007) Methods Variables • Spontaneous Conversation • Direct Judgement Task • Indirect Judgement Task • Pictorial Task* • Magnitude Estimation (1) Multiple Negation (2) Subject Doubling (3) Double Modals (4) Double Conjunctions (5) Verb Doubling

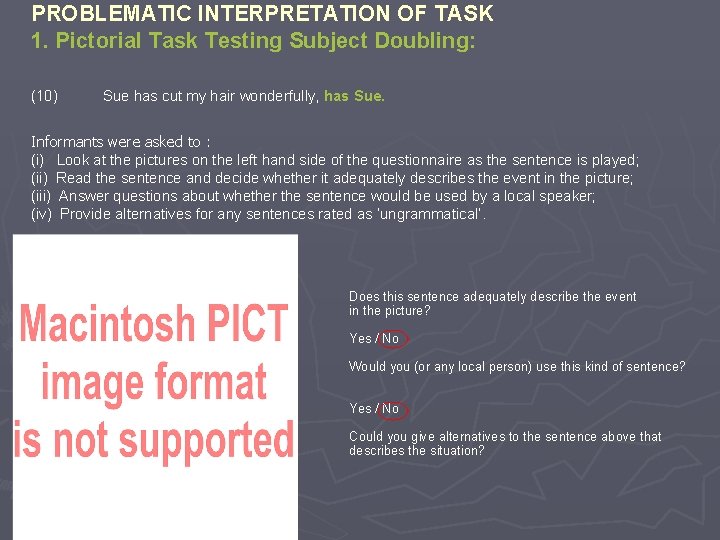

PROBLEMATIC INTERPRETATION OF TASK 1. Pictorial Task Testing Subject Doubling: (10) Sue has cut my hair wonderfully, has Sue. Informants were asked to : (i) Look at the pictures on the left hand side of the questionnaire as the sentence is played; (ii) Read the sentence and decide whether it adequately describes the event in the picture; (iii) Answer questions about whether the sentence would be used by a local speaker; (iv) Provide alternatives for any sentences rated as ‘ungrammatical’. Does this sentence adequately describe the event in the picture? Yes / No Would you (or any local person) use this kind of sentence? Yes / No Could you give alternatives to the sentence above that describes the situation?

PROBLEMATIC INTERPRETATION OF TASK 1. Provide alternatives for any sentence rated *

A Solution: The ‘Modular’ Approach to Variability • Be aware of data collection pitfalls and design studies that combine both spontaneous and elicited data; • Adopt a ‘modular’ approach to data analysis as well as collection:

A Solution: The ‘Modular’ Approach to Variability • Be aware of data collection pitfalls and design studies that combine both spontaneous and elicited data; • Adopt a ‘modular’ approach to data analysis as well as collection:

A Solution: The ‘Modular’ Approach to Variability • Interfaces and the sociolinguistic syntactic variable syntactically related ‘low level’ ≠ interface level syntactically remote ‘high level’ = interface level

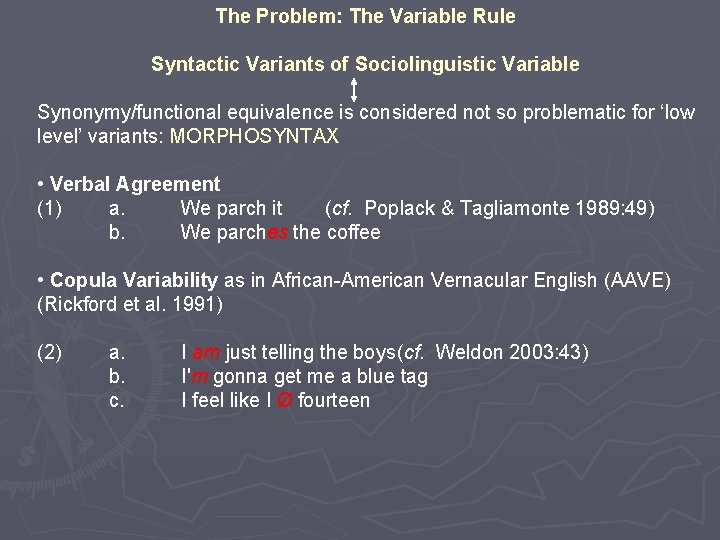

The Problem: The Variable Rule Syntactic Variants of Sociolinguistic Variable Synonymy/functional equivalence is considered not so problematic for ‘low level’ variants: MORPHOSYNTAX • Verbal Agreement (1) a. We parch it (cf. Poplack & Tagliamonte 1989: 49) b. We parches the coffee • Copula Variability as in African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) (Rickford et al. 1991) (2) a. b. c. I am just telling the boys(cf. Weldon 2003: 43) I'm gonna get me a blue tag I feel like I Ø fourteen

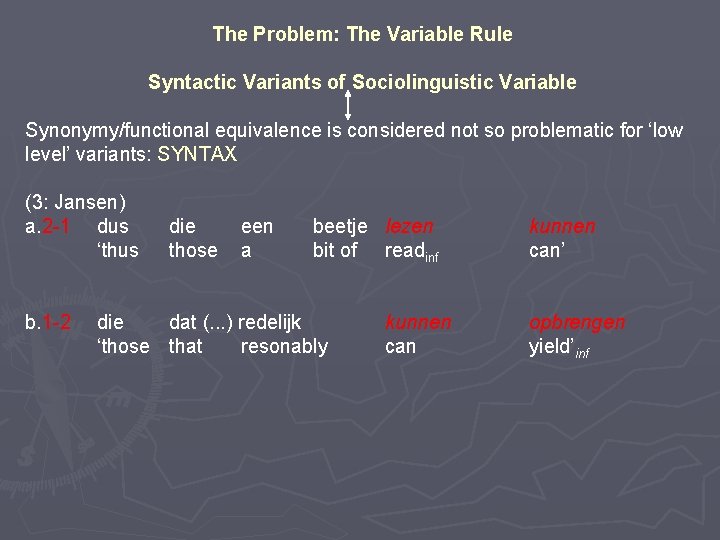

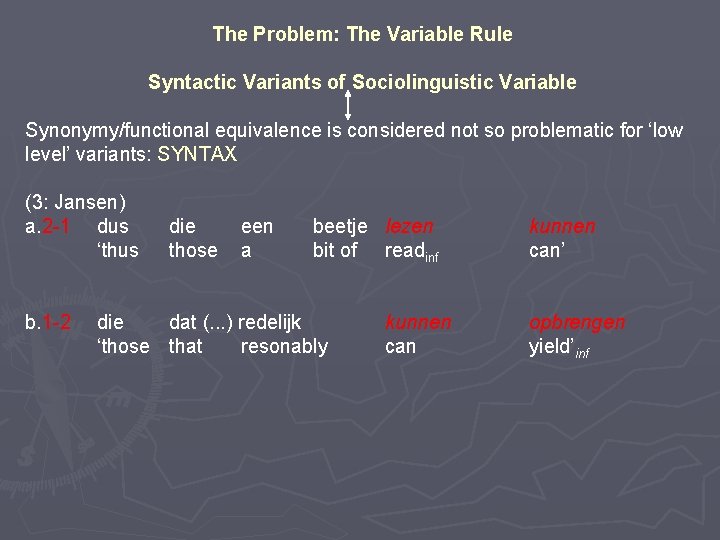

The Problem: The Variable Rule Syntactic Variants of Sociolinguistic Variable Synonymy/functional equivalence is considered not so problematic for ‘low level’ variants: SYNTAX (3: Jansen) a. 2 -1 dus ‘thus b. 1 -2 die those een a beetje lezen bit of readinf die dat (. . . ) redelijk ‘those that resonably kunnen can’ opbrengen yield’inf

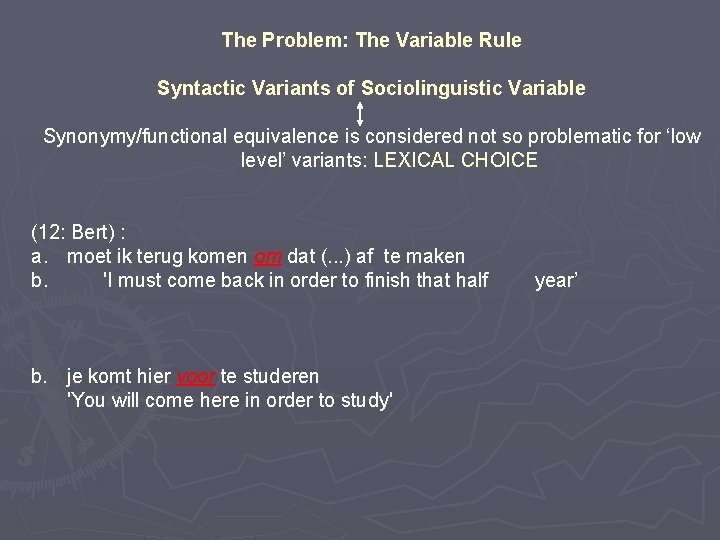

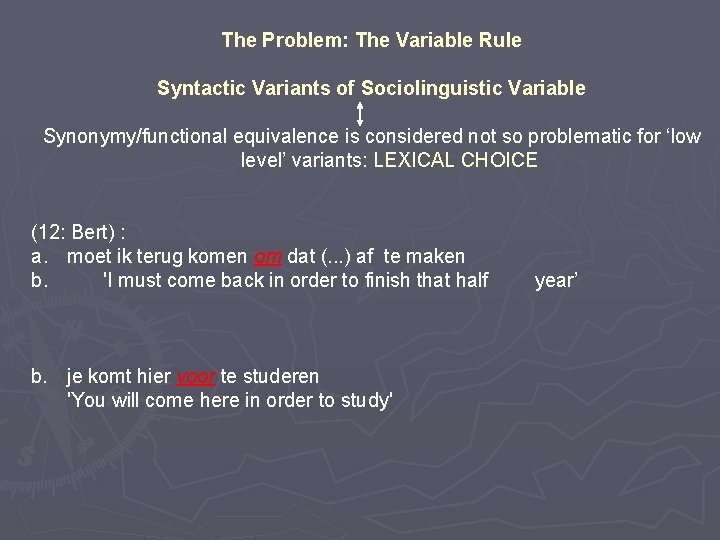

The Problem: The Variable Rule Syntactic Variants of Sociolinguistic Variable Synonymy/functional equivalence is considered not so problematic for ‘low level’ variants: LEXICAL CHOICE (12: Bert) : a. moet ik terug komen om dat (. . . ) af te maken b. 'I must come back in order to finish that half b. je komt hier voor te studeren 'You will come here in order to study' year’

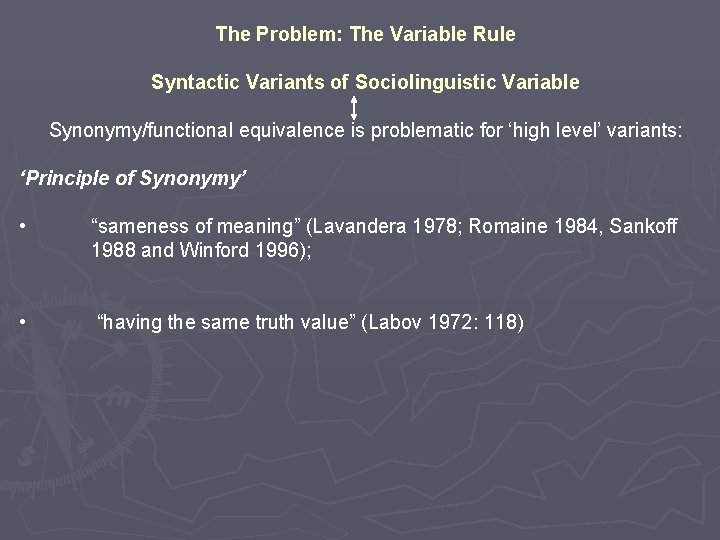

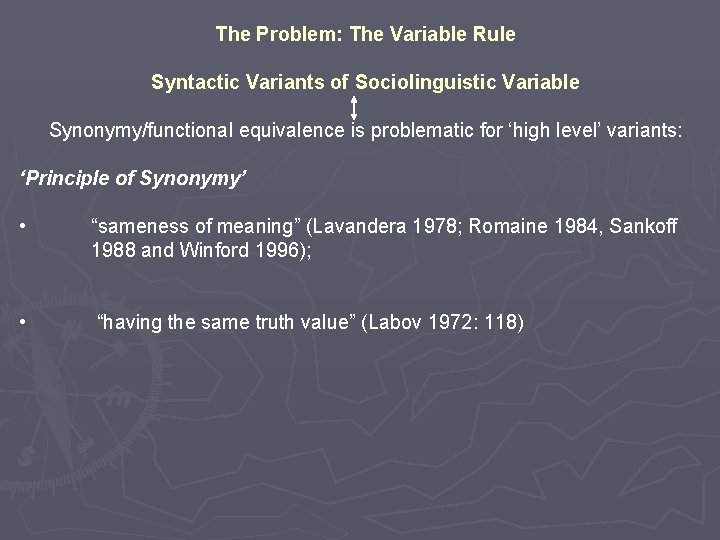

The Problem: The Variable Rule Syntactic Variants of Sociolinguistic Variable Synonymy/functional equivalence is problematic for ‘high level’ variants: ‘Principle of Synonymy’ • “sameness of meaning” (Lavandera 1978; Romaine 1984, Sankoff 1988 and Winford 1996); • “having the same truth value” (Labov 1972: 118)

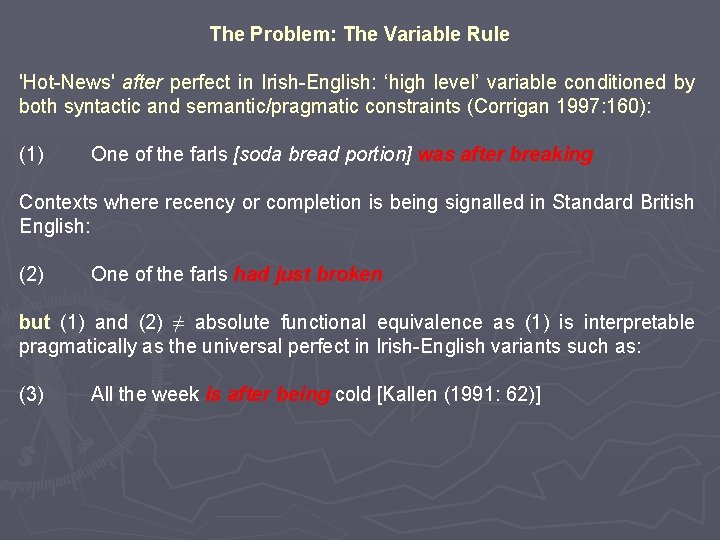

The Problem: The Variable Rule 'Hot-News' after perfect in Irish-English: ‘high level’ variable conditioned by both syntactic and semantic/pragmatic constraints (Corrigan 1997: 160): (1) One of the farls [soda bread portion] was after breaking Contexts where recency or completion is being signalled in Standard British English: (2) One of the farls had just broken but (1) and (2) ≠ absolute functional equivalence as (1) is interpretable pragmatically as the universal perfect in Irish-English variants such as: (3) All the week is after being cold [Kallen (1991: 62)]

The Problem: The Variable Rule Habitual ‘doen’ in Heerlen Dutch: ‘high level’ variable conditioned by both syntactic and semantic/pragmatic constraints: a. een jongen (. . . ) a boy 'A boy (. . . ) also fishes’ doet does ook also b. hij ‘he well eens. . . once…’ vist ook fishes too vissen. . . fishinf. . . (19: Cor)

![What Else Makes a Modular Approach Necessary After Cornips Corrigan 2005 ab What Else Makes a Modular Approach Necessary? [After Cornips & Corrigan 2005 a/b]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/19272b4616f2e8061405cfb01d37aae9/image-28.jpg)

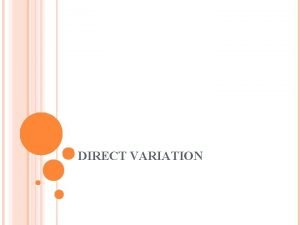

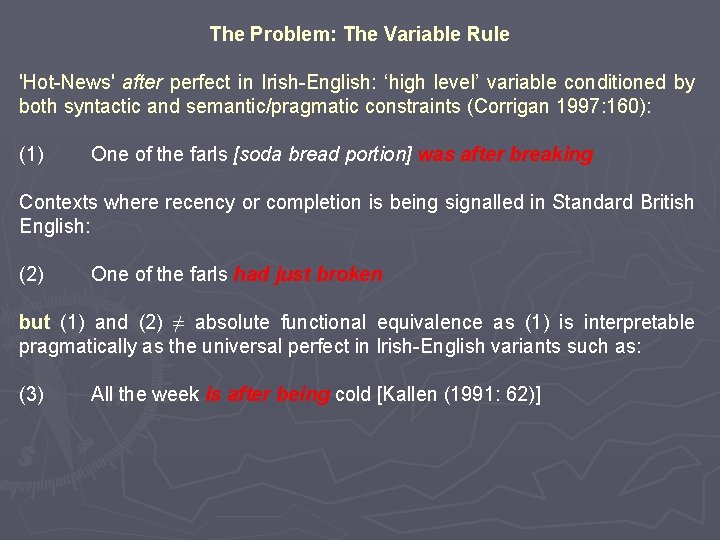

What Else Makes a Modular Approach Necessary? [After Cornips & Corrigan 2005 a/b]

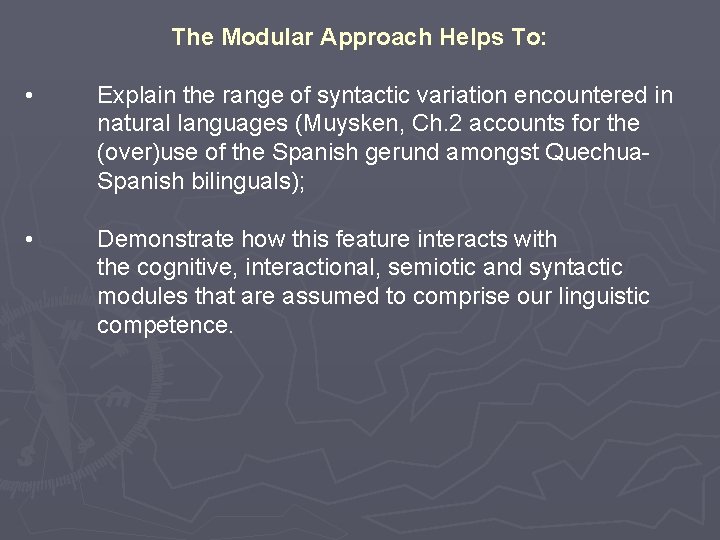

The Modular Approach Helps To: • Explain the range of syntactic variation encountered in natural languages (Muysken, Ch. 2 accounts for the (over)use of the Spanish gerund amongst Quechua. Spanish bilinguals); • Demonstrate how this feature interacts with the cognitive, interactional, semiotic and syntactic modules that are assumed to comprise our linguistic competence.

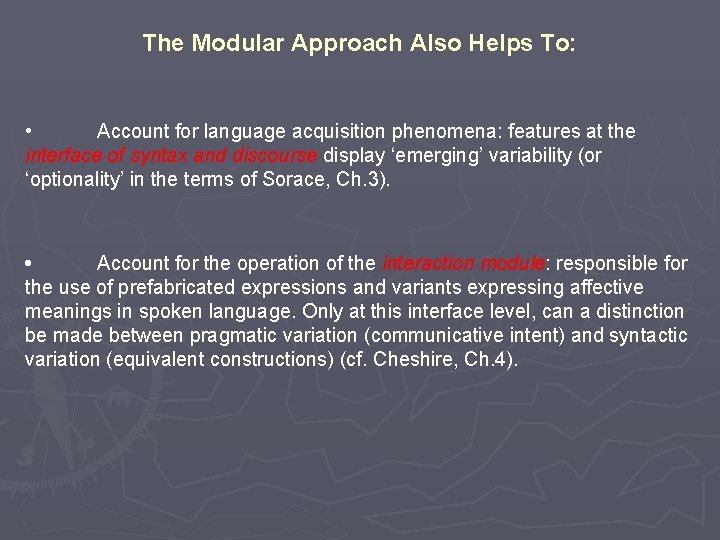

The Modular Approach Also Helps To: • Account for language acquisition phenomena: features at the interface of syntax and discourse display ‘emerging’ variability (or ‘optionality’ in the terms of Sorace, Ch. 3). • Account for the operation of the interaction module: responsible for the use of prefabricated expressions and variants expressing affective meanings in spoken language. Only at this interface level, can a distinction be made between pragmatic variation (communicative intent) and syntactic variation (equivalent constructions) (cf. Cheshire, Ch. 4).

Conclusion • A Modular approach can provide an integrated theory of syntactic variation; • A Modular approach suggests that the locus of VARIABLE phenomena is most likely to be where the syntax module is mapped to other domains and that it is in these areas where variation that has social meaning is located; • Paying closer attention to modularity and interface levels will prove critical to enhancing our understanding of the locus of variation on which these issues hinge.

Which graph represents a function with direct variation

Which graph represents a function with direct variation Direct and inverse variation

Direct and inverse variation Prediction interval formula

Prediction interval formula Mountain bike mania student copy

Mountain bike mania student copy Political cartoon analogy

Political cartoon analogy Argument analysis structure

Argument analysis structure How do consumers respond to various marketing efforts

How do consumers respond to various marketing efforts Analysing a cartoon

Analysing a cartoon Methods of analysis character

Methods of analysis character Matching stage in strategic management

Matching stage in strategic management Art sentence starters

Art sentence starters Analyze business transactions

Analyze business transactions Inquiring and analysing

Inquiring and analysing Cultural aspects of strategy choice

Cultural aspects of strategy choice Analysing argument

Analysing argument Analysing the 6 strategic options megxit

Analysing the 6 strategic options megxit Analysing market data

Analysing market data Gods ways are not our ways

Gods ways are not our ways New ways to learn

New ways to learn Chapter 7 section 4 new ways of thinking

Chapter 7 section 4 new ways of thinking New ways of doing business

New ways of doing business Lexical vs syntactic ambiguity

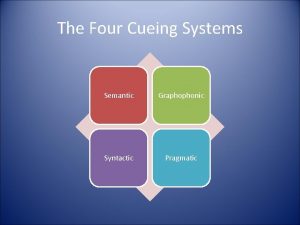

Lexical vs syntactic ambiguity Graphophonic cues examples

Graphophonic cues examples The boy saw the man with the telescope tree diagram

The boy saw the man with the telescope tree diagram Asyndeton stylistic device

Asyndeton stylistic device Syntactic knowledge

Syntactic knowledge Ion adjectives

Ion adjectives Semantic patterning example

Semantic patterning example Syntactic bootstrapping

Syntactic bootstrapping Ic analysis example

Ic analysis example Syntactic awareness

Syntactic awareness 812007

812007