NETWORK PROGRAMMING INTRO TO DISTRIBUTED SYSTEMS FALL 2013

NETWORK PROGRAMMING INTRO TO DISTRIBUTED SYSTEMS FALL 2013 Some material taken from publicly available lecture slides including Srini Seshan’s and David Anderson’s Dongsu L 3 -socket

Today’s Lecture � Transport protocols: UDP and TCP � Version control using SVN TA-led programming session � Editor, socket programming � Debugging with gdb Announcement � Programming Assignment 1 is out. (Due in two weeks--추석)

Review of Previous Lectures What is a distributed system? (L 1) � Definition � Example What are some of the important decisions made in the Internet architecture? (L 2) � Narrow Why? : waist: Network provides minimal functionality (best-effort) to connect existing networks that are heterogeneous � Stateless architecture: no per-flow state inside network Why? For survivability

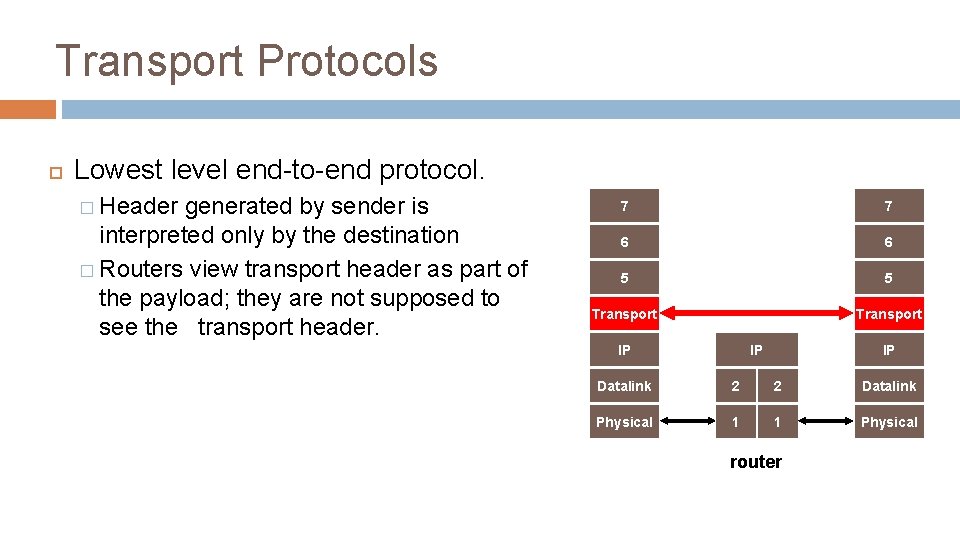

Transport Protocols Lowest level end-to-end protocol. � Header generated by sender is interpreted only by the destination � Routers view transport header as part of the payload; they are not supposed to see the transport header. 7 7 6 6 5 5 Transport IP IP IP Datalink 2 2 Datalink Physical 1 1 Physical router 4

What does the transport layer do? No per-flow (connection) state in the network � Transport layer maintains the connection state. Transport layer identifies an end-to-end connection. How does the transport layer identify an end-point (application)?

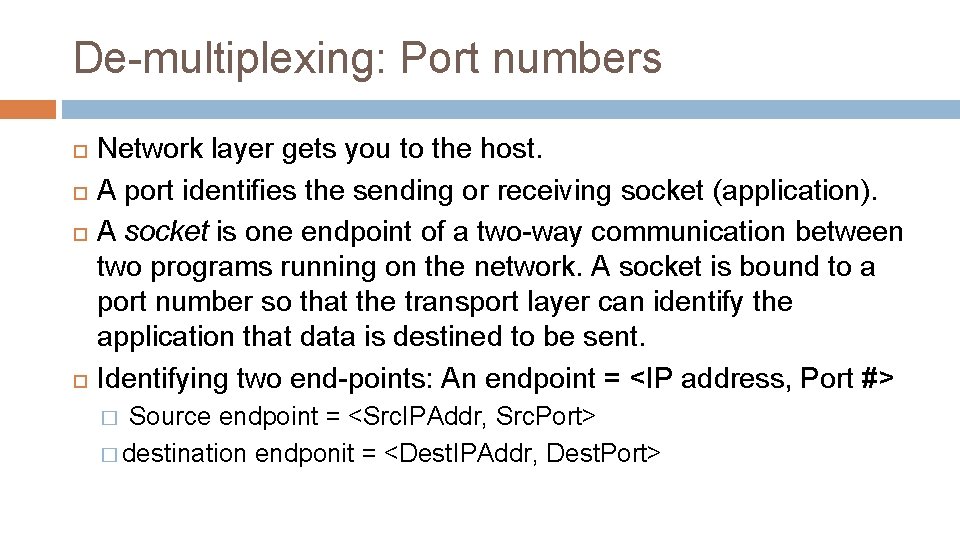

De-multiplexing: Port numbers Network layer gets you to the host. A port identifies the sending or receiving socket (application). A socket is one endpoint of a two-way communication between two programs running on the network. A socket is bound to a port number so that the transport layer can identify the application that data is destined to be sent. Identifying two end-points: An endpoint = <IP address, Port #> Source endpoint = <Src. IPAddr, Src. Port> � destination endponit = <Dest. IPAddr, Dest. Port> �

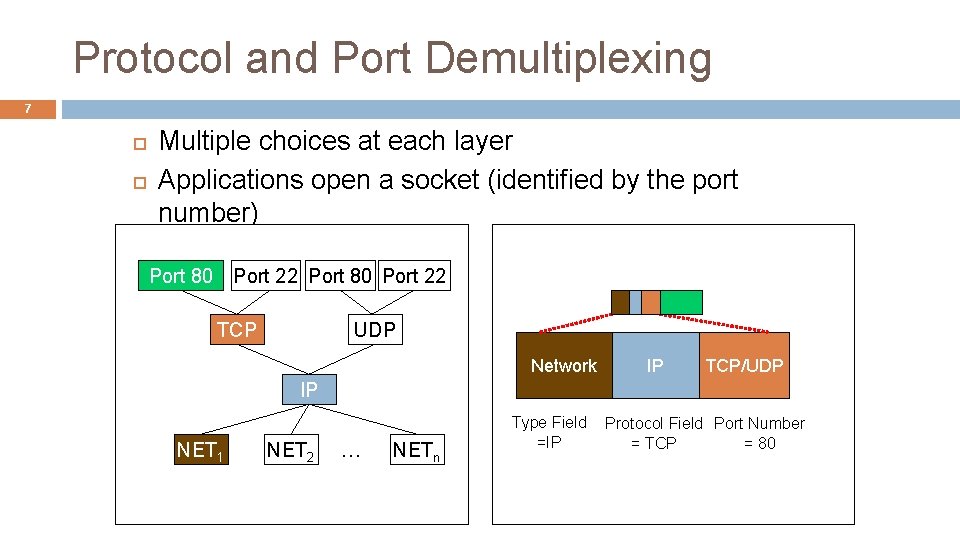

Protocol and Port Demultiplexing 7 Multiple choices at each layer Applications open a socket (identified by the port number) Port 80 Port 22 TCP UDP Network IP TCP/UDP IP NET 1 NET 2 … NETn Type Field =IP Protocol Field Port Number = TCP = 80

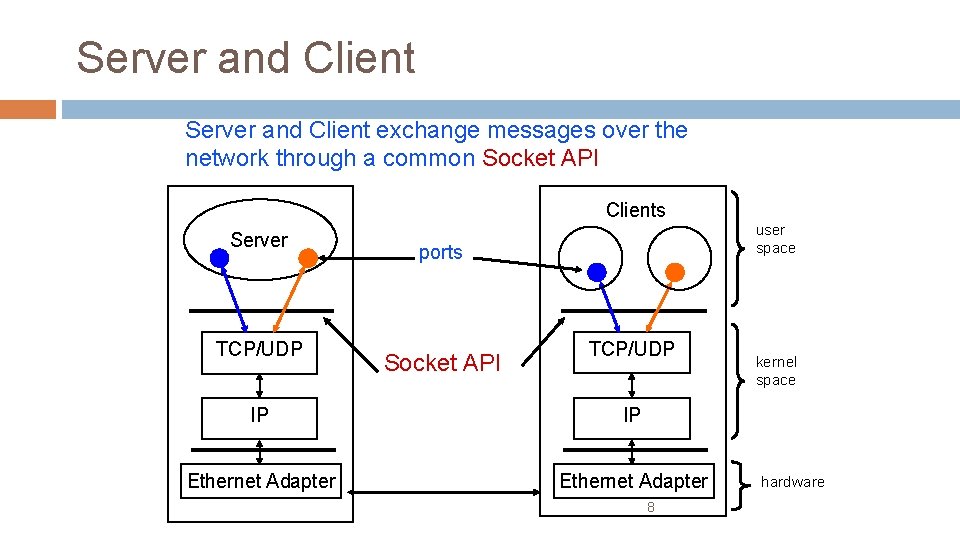

Server and Client exchange messages over the network through a common Socket API Clients Server TCP/UDP ports Socket API TCP/UDP IP IP Ethernet Adapter 8 user space kernel space hardware

Transport protocols UDP � Provides only integrity and de-multiplexing TCP adds…

![UDP: User Datagram Protocol [RFC 768] 10 “No frills, ” “bare bones” Internet transport UDP: User Datagram Protocol [RFC 768] 10 “No frills, ” “bare bones” Internet transport](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/61f5f1bacd8ce9096dbb713dbce87b12/image-10.jpg)

UDP: User Datagram Protocol [RFC 768] 10 “No frills, ” “bare bones” Internet transport protocol, “Best effort” service UDP segments may be: � � Lost, duplicated (bug, spurious retransmission at L 2) Delivered out of order to app Connectionless: � � No handshaking between UDP sender, receiver Each UDP segment handled independently Why is there a UDP? • No connection establishment (which can add delay) • Simple: no connection state at sender, receiver • Small header • No congestion control: UDP can blast away as fast as desired

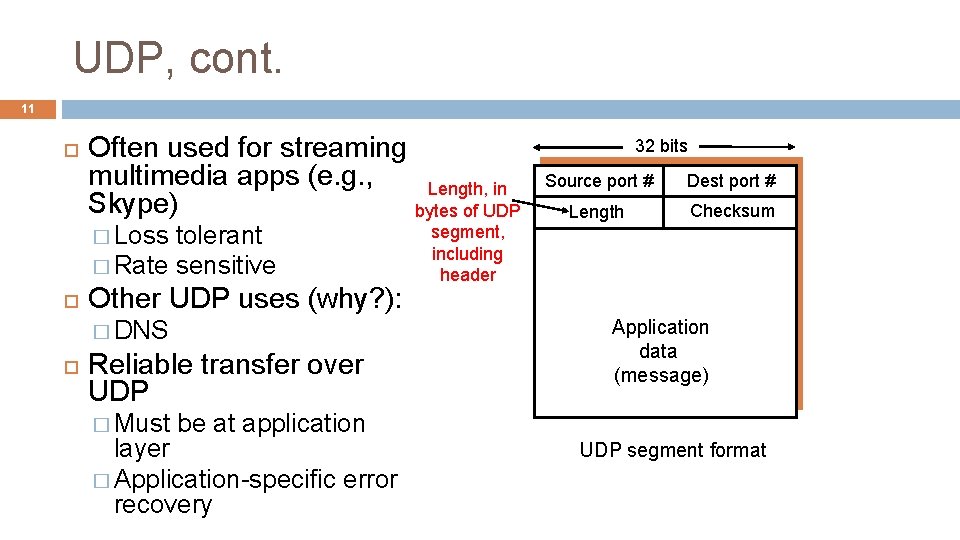

UDP, cont. 11 Often used for streaming multimedia apps (e. g. , Length, in Skype) bytes of UDP � Loss tolerant � Rate sensitive Other UDP uses (why? ): � DNS Reliable transfer over UDP � Must segment, including header 32 bits Source port # Dest port # Length Checksum Application data (message) be at application layer � Application-specific error recovery UDP segment format

Transport protocols UDP � Provides only integrity and de-multiplexing TCP adds… � Connection-oriented � Reliable (error control) � Ordered byte stream (in-order delivery) � Bi-directional byte-stream � Flow and congestion controlled

TCP Protocol implemented entirely at the ends �Fate sharing Abstraction provided �Connection oriented protocol (hand-shake or connection establishment) �In-order byte-stream Implemented functionality (next lecture) � Flow control � Reliability (error control) � Reassembly (in-order delivery) � Congestion control

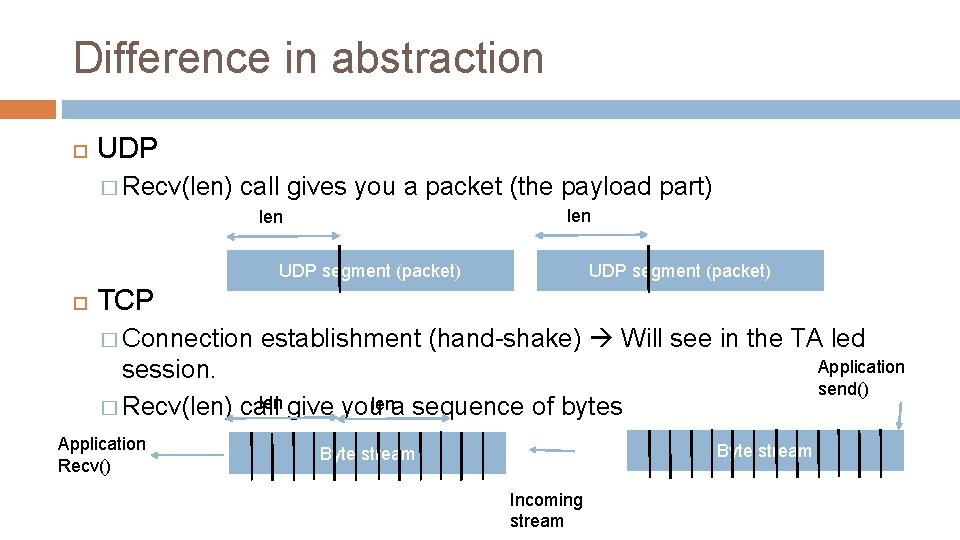

Difference in abstraction UDP � Recv(len) call gives you a packet (the payload part) len UDP segment (packet) TCP � Connection establishment (hand-shake) Will see in the TA led session. len give you lena sequence of bytes � Recv(len) call Application Recv() Application send() Byte stream Incoming stream

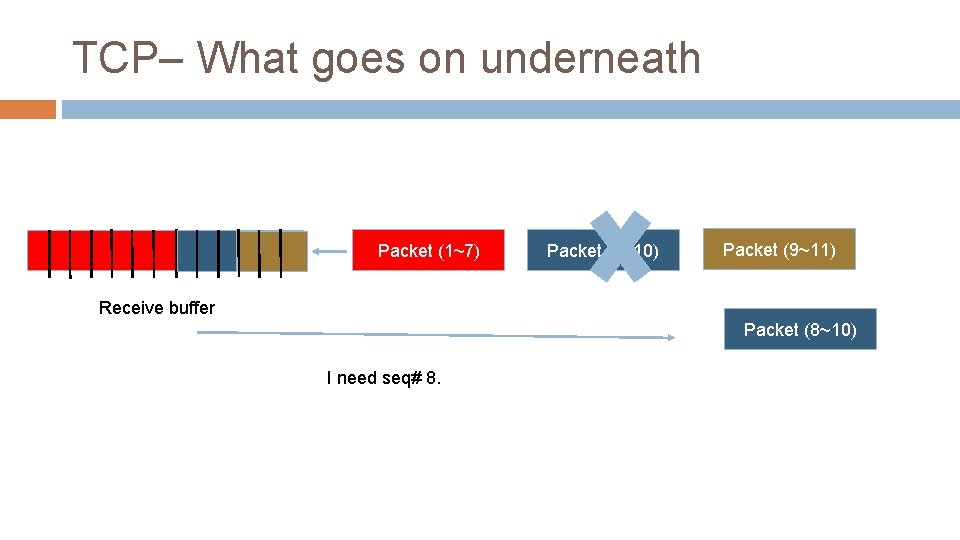

TCP– What goes on underneath Byte stream Packet (1~7) Packet (8~10) Packet (9~11) Receive buffer Packet (8~10) I need seq# 8.

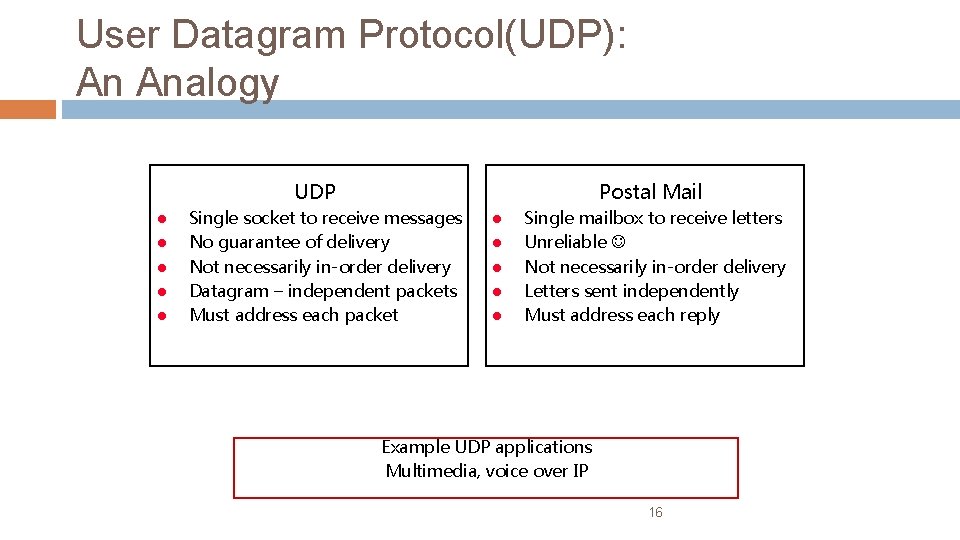

User Datagram Protocol(UDP): An Analogy Postal Mail UDP l l l Single socket to receive messages No guarantee of delivery Not necessarily in-order delivery Datagram – independent packets Must address each packet l l l Single mailbox to receive letters Unreliable Not necessarily in-order delivery Letters sent independently Must address each reply Example UDP applications Multimedia, voice over IP 16

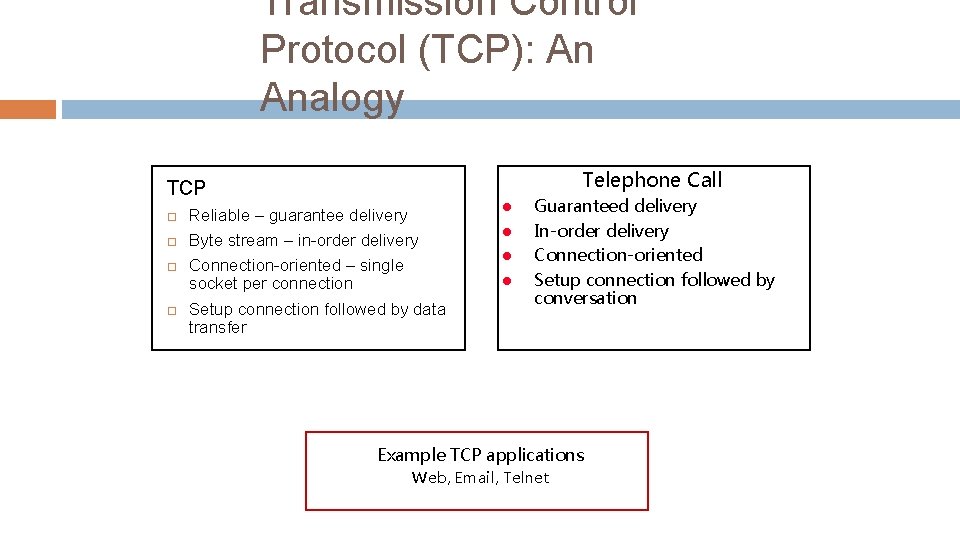

Transmission Control Protocol (TCP): An Analogy Telephone Call TCP Reliable – guarantee delivery Byte stream – in-order delivery Connection-oriented – single socket per connection Setup connection followed by data transfer l l Guaranteed delivery In-order delivery Connection-oriented Setup connection followed by conversation Example TCP applications Web, Email, Telnet

REVISION CONTROL & MAKE

Overview Revision control systems � Motivation � Features � Subversion primer Make � Simple gcc � Make basics and variables � Testing Useful Unix commands

Dealing with large codebases Complications � Code synchronization � Backups � Concurrent modifications Solution: Revision Control System (RCS) � Store all of your code in a repository on a server � Metadata to track changes, revisions, etc… � Also useful for writing books, papers, etc…

Basic RCS features (1/2) Infinite undo � go Automatic backups � all back to previous revisions your code ever, forever saved Changes tracking � see differences between revisions

Basic RCS features (2/2) Concurrency � Multiple Snapshots � Save people working at the same time stable versions on the side (i. e. handin) Branching � Create diverging code paths for experimentation

Typical RCS workflow 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Create repository on RCS server Checkout the repository to your local machine Work locally: create, delete and modify files Update the repository to check for changes other people might have made Resolve any existing conflicts Commit your changes to the repository

RCS implementations Revision Control System (RCS) � Concurrent Versions System (CVS) � Early system, no concurrency or conflict resolution Concurrency, versioning of single files Subversion (SVN) � File and directory moving and renaming, atomic commits

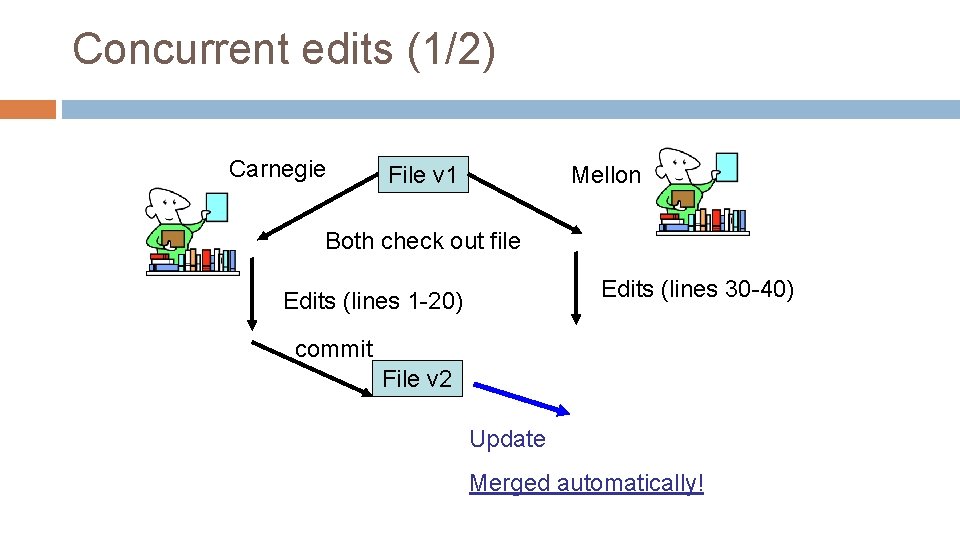

Concurrent edits (1/2) Carnegie File v 1 Mellon Both check out file Edits (lines 30 -40) Edits (lines 1 -20) commit File v 2 Update Merged automatically!

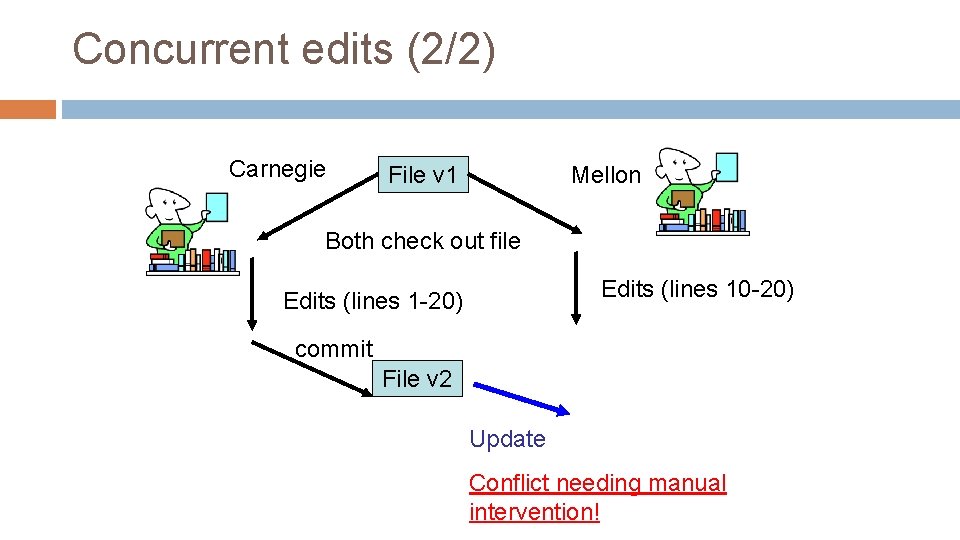

Concurrent edits (2/2) Carnegie File v 1 Mellon Both check out file Edits (lines 10 -20) Edits (lines 1 -20) commit File v 2 Update Conflict needing manual intervention!

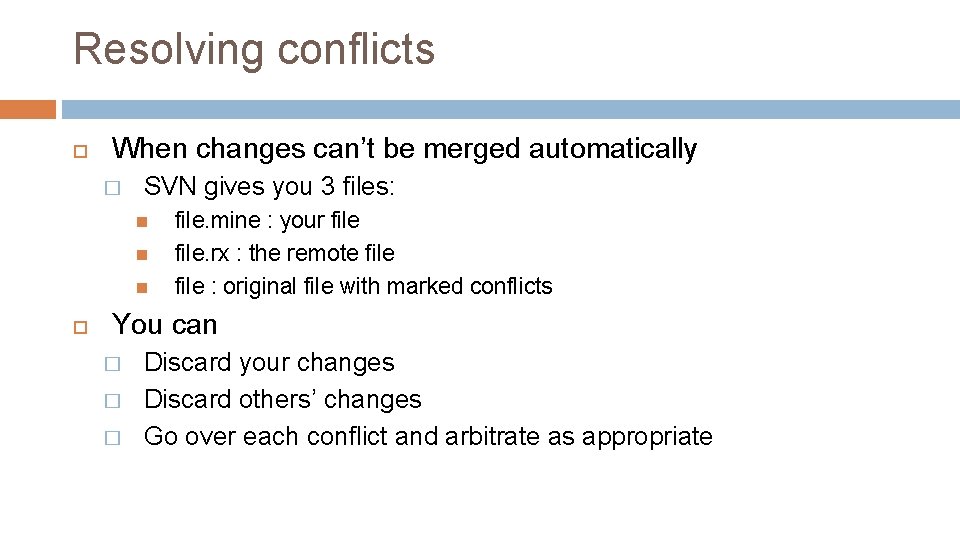

Resolving conflicts When changes can’t be merged automatically � SVN gives you 3 files: file. mine : your file. rx : the remote file : original file with marked conflicts You can � � � Discard your changes Discard others’ changes Go over each conflict and arbitrate as appropriate

Interacting with SVN Command line � Readily available in andrew machines Graphical tools � � � Easier to use Subclipse for Eclipse gives IDE/SVN integration tortoise. SVN

실습 server IP: 143. 248. 141. 52 ~ 143. 248. 141. 59 (8대) ID: your student id (e. g. , 20110111) Password: ee 324 EE#@$

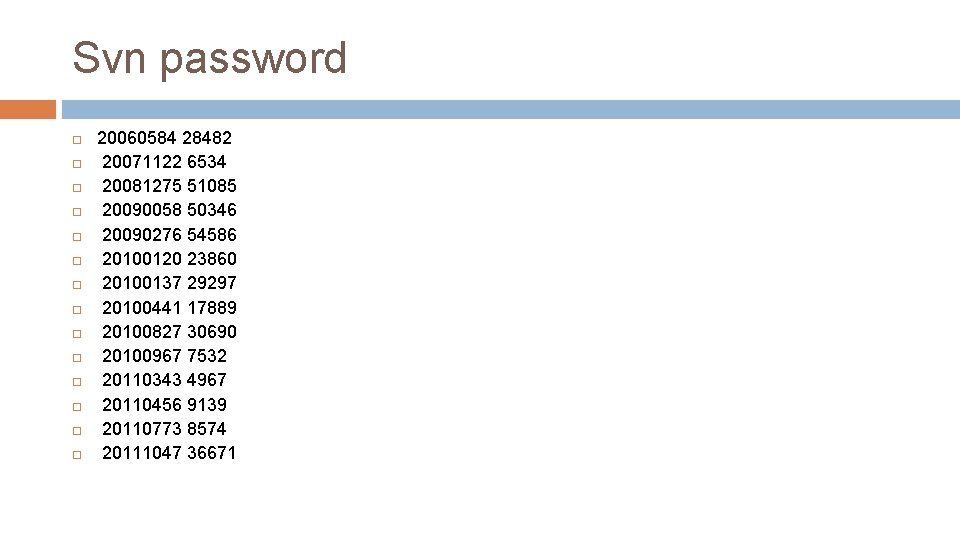

Svn password 20060584 28482 20071122 6534 20081275 51085 20090058 50346 20090276 54586 20100120 23860 20100137 29297 20100441 17889 20100827 30690 20100967 7532 20110343 4967 20110456 9139 20110773 8574 20111047 36671

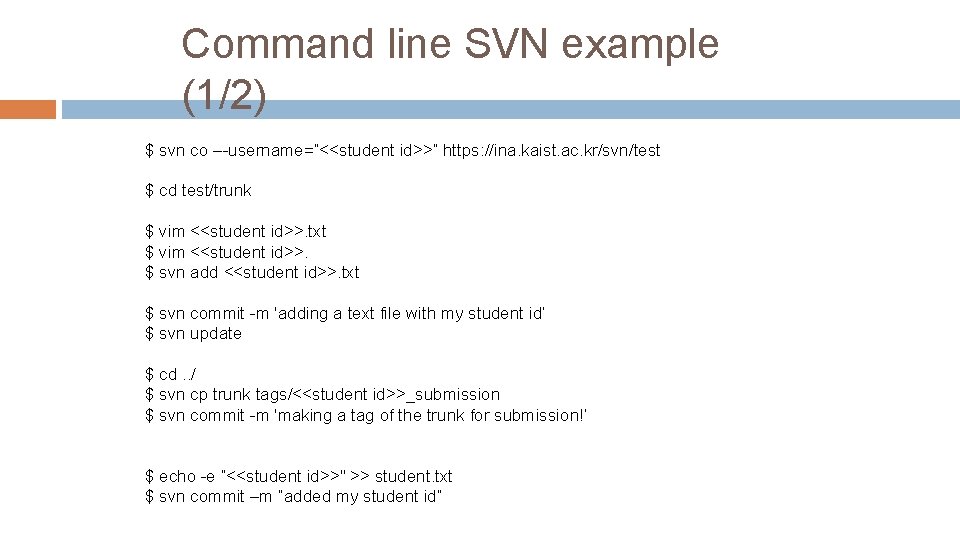

Command line SVN example (1/2) $ svn co –-username=“<<student id>>” https: //ina. kaist. ac. kr/svn/test $ cd test/trunk $ vim <<student id>>. txt $ vim <<student id>>. $ svn add <<student id>>. txt $ svn commit -m 'adding a text file with my student id‘ $ svn update $ cd. . / $ svn cp trunk tags/<<student id>>_submission $ svn commit -m 'making a tag of the trunk for submission!‘ $ echo -e ”<<student id>>" >> student. txt $ svn commit –m “added my student id”

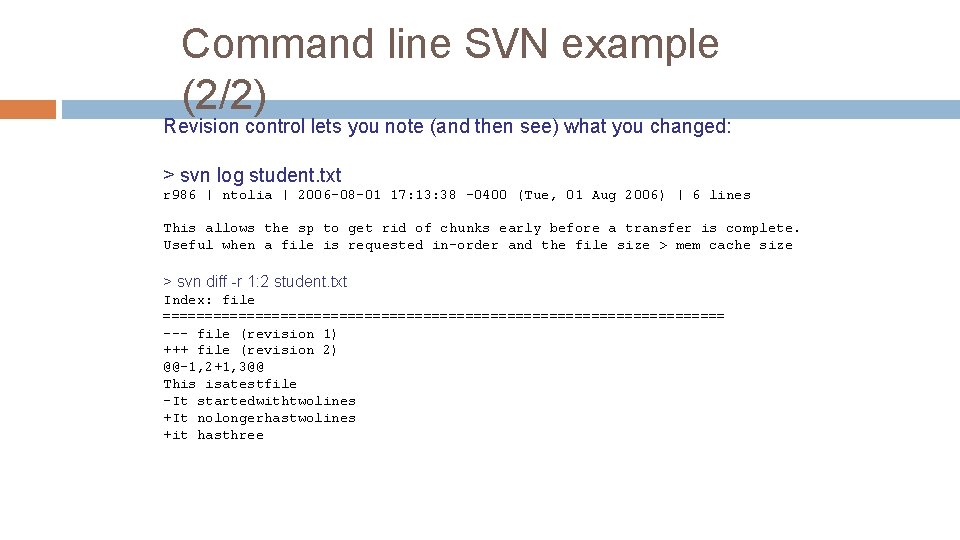

Command line SVN example (2/2) Revision control lets you note (and then see) what you changed: > svn log student. txt r 986 | ntolia | 2006 -08 -01 17: 13: 38 -0400 (Tue, 01 Aug 2006) | 6 lines This allows the sp to get rid of chunks early before a transfer is complete. Useful when a file is requested in-order and the file size > mem cache size > svn diff -r 1: 2 student. txt Index: file ================================== --- file (revision 1) +++ file (revision 2) @@-1, 2+1, 3@@ This isatestfile -It startedwithtwolines +It nolongerhastwolines +it hasthree

General SVN tips Update, make, test, only then commit Merge often (svn up) Comment commits Avoid commit races Modular design avoids conflicts

Know more subversion. tigris. org for SVN software & info svnbook. red-bean. com for SVN book

Makefile You are on your own.

Make Utility for executable building automation Saves you time and frustration Helps you test more and better

Simple gcc If we have files: • prog. c: The main program file • lib. c: Library. c file • lib. h: Library header file % gcc -c prog. c -o prog. o % gcc -c lib. c -o lib. o % gcc lib. o prog. o -o binary

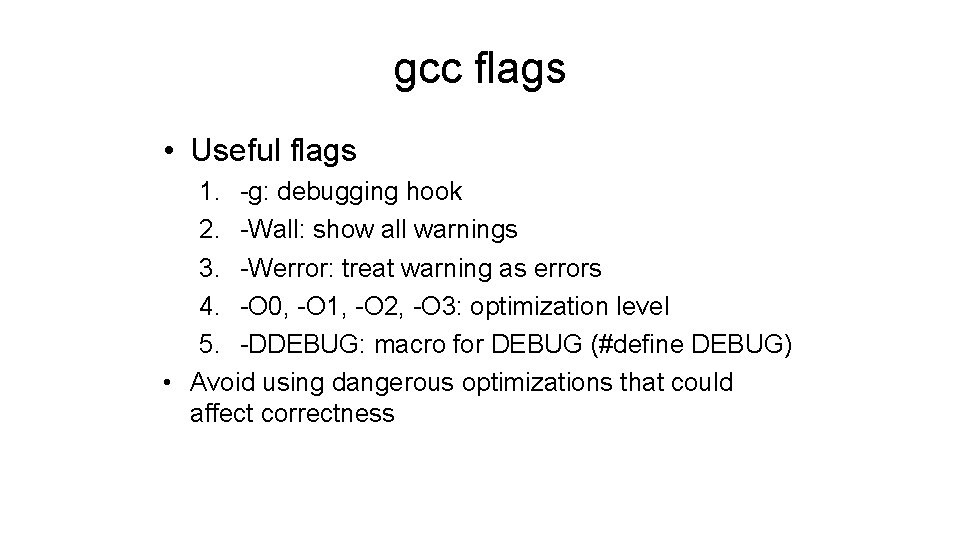

gcc flags • Useful flags 1. -g: debugging hook 2. -Wall: show all warnings 3. -Werror: treat warning as errors 4. -O 0, -O 1, -O 2, -O 3: optimization level 5. -DDEBUG: macro for DEBUG (#define DEBUG) • Avoid using dangerous optimizations that could affect correctness

More gcc % gcc -g -Wall -Werror -c prog. c -o prog. o % gcc -g -Wall -Werror -c lib. c -o lib. o % gcc -g -Wall -Werror lib. o prog. o -o binary This gets boring, fast!

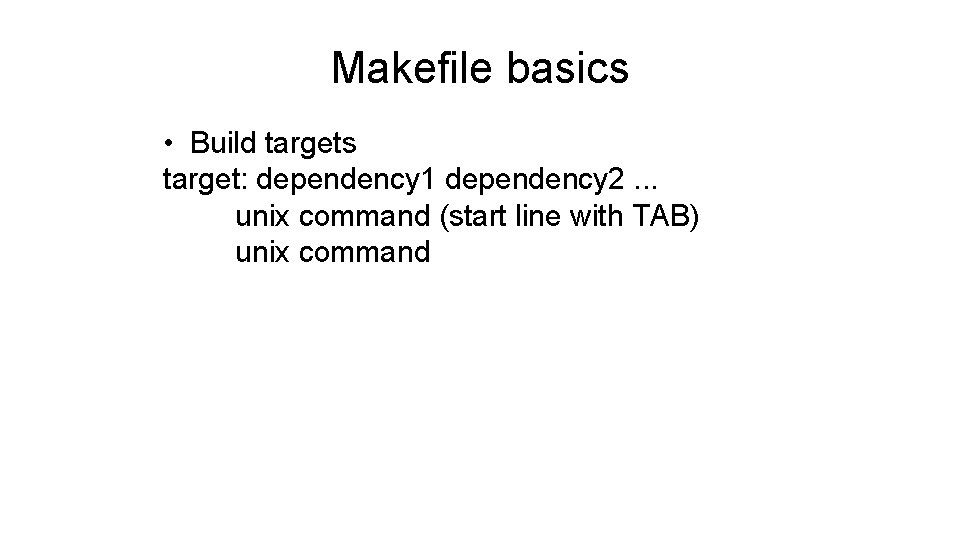

Makefile basics • Build targets target: dependency 1 dependency 2. . . unix command (start line with TAB) unix command

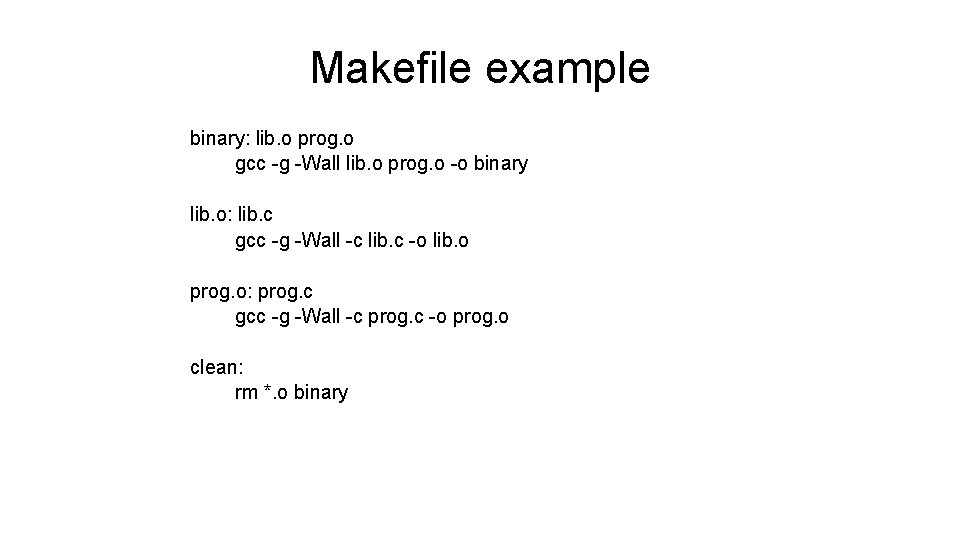

Makefile example binary: lib. o prog. o gcc -g -Wall lib. o prog. o -o binary lib. o: lib. c gcc -g -Wall -c lib. c -o lib. o prog. o: prog. c gcc -g -Wall -c prog. c -o prog. o clean: rm *. o binary

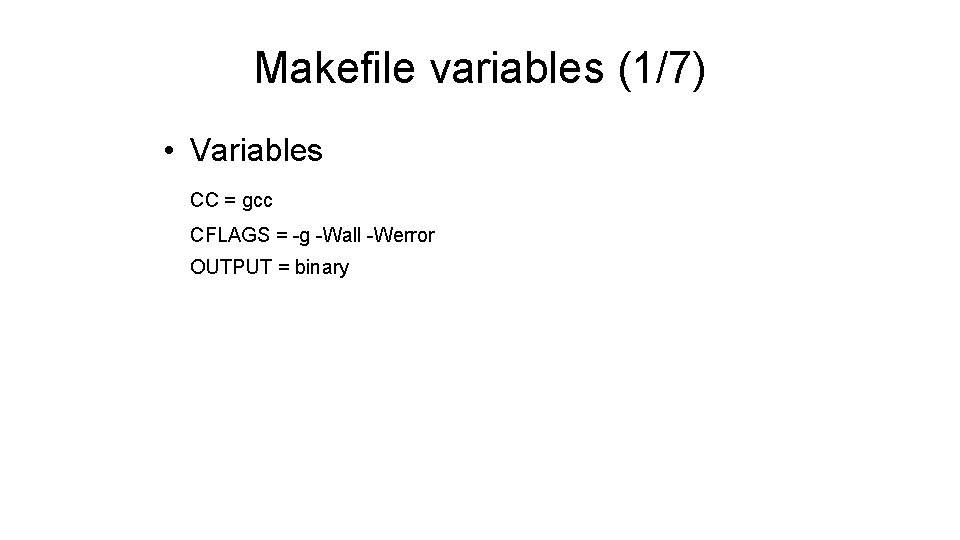

Makefile variables (1/7) • Variables CC = gcc CFLAGS = -g -Wall -Werror OUTPUT = binary

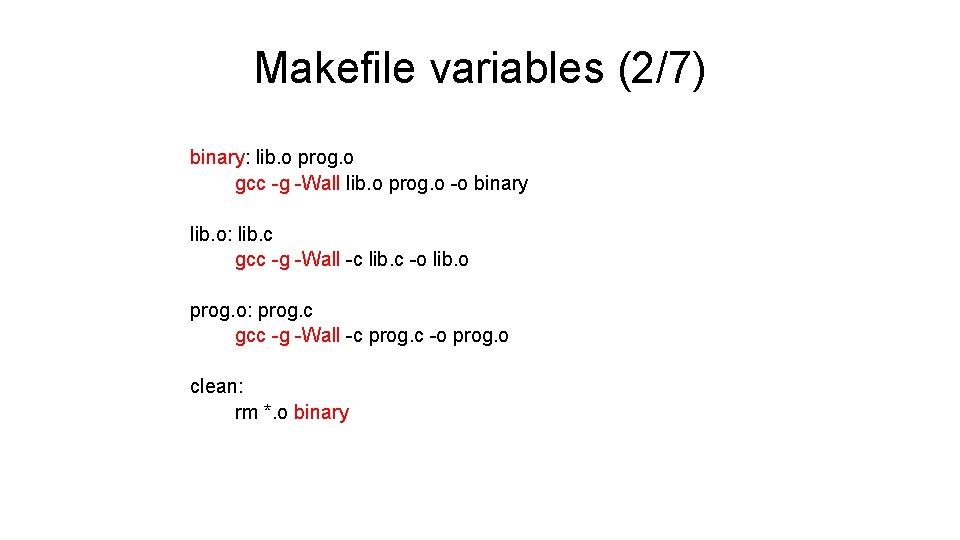

Makefile variables (2/7) binary: lib. o prog. o gcc -g -Wall lib. o prog. o -o binary lib. o: lib. c gcc -g -Wall -c lib. c -o lib. o prog. o: prog. c gcc -g -Wall -c prog. c -o prog. o clean: rm *. o binary

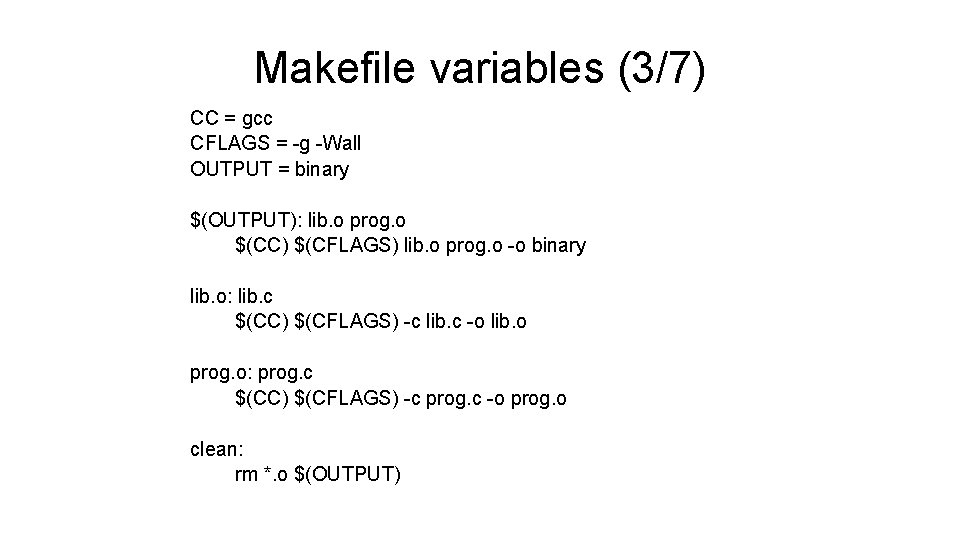

Makefile variables (3/7) CC = gcc CFLAGS = -g -Wall OUTPUT = binary $(OUTPUT): lib. o prog. o $(CC) $(CFLAGS) lib. o prog. o -o binary lib. o: lib. c $(CC) $(CFLAGS) -c lib. c -o lib. o prog. o: prog. c $(CC) $(CFLAGS) -c prog. c -o prog. o clean: rm *. o $(OUTPUT)

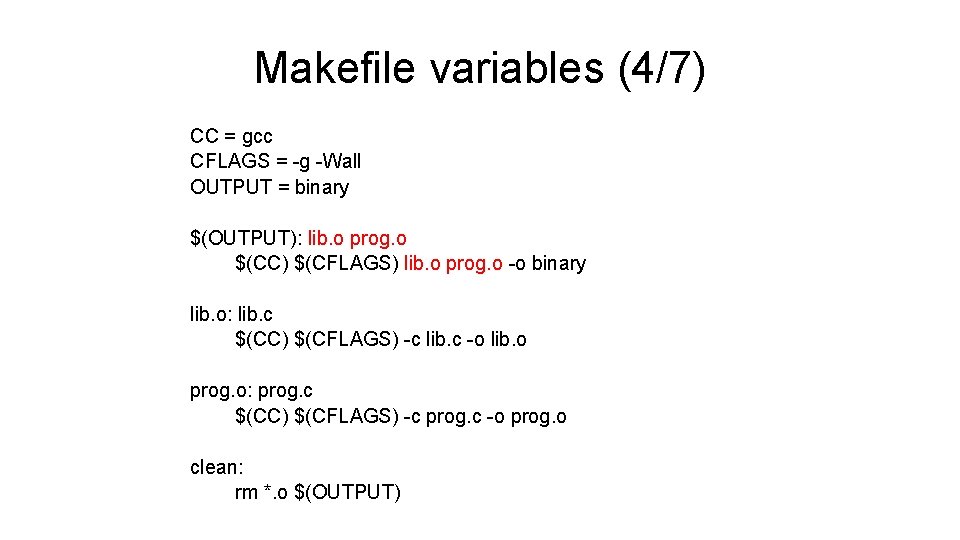

Makefile variables (4/7) CC = gcc CFLAGS = -g -Wall OUTPUT = binary $(OUTPUT): lib. o prog. o $(CC) $(CFLAGS) lib. o prog. o -o binary lib. o: lib. c $(CC) $(CFLAGS) -c lib. c -o lib. o prog. o: prog. c $(CC) $(CFLAGS) -c prog. c -o prog. o clean: rm *. o $(OUTPUT)

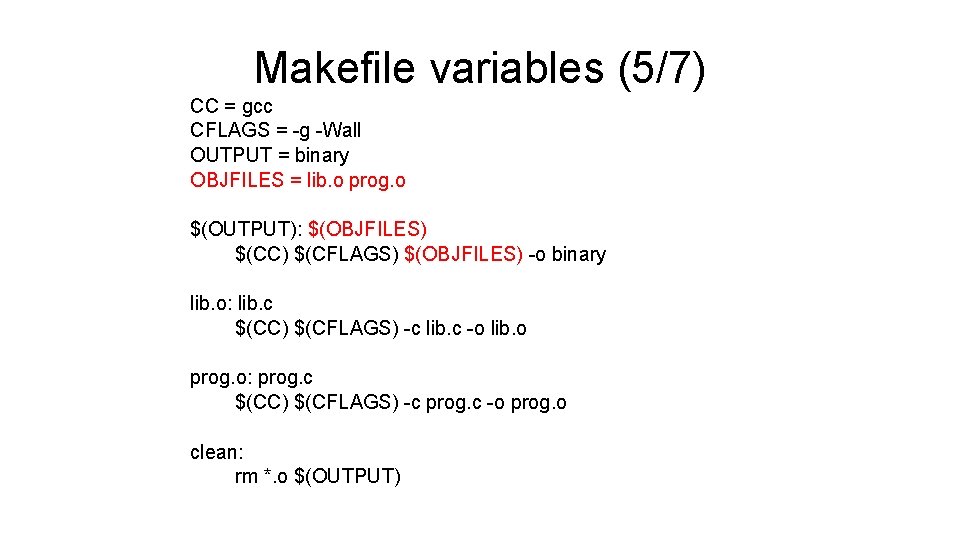

Makefile variables (5/7) CC = gcc CFLAGS = -g -Wall OUTPUT = binary OBJFILES = lib. o prog. o $(OUTPUT): $(OBJFILES) $(CC) $(CFLAGS) $(OBJFILES) -o binary lib. o: lib. c $(CC) $(CFLAGS) -c lib. c -o lib. o prog. o: prog. c $(CC) $(CFLAGS) -c prog. c -o prog. o clean: rm *. o $(OUTPUT)

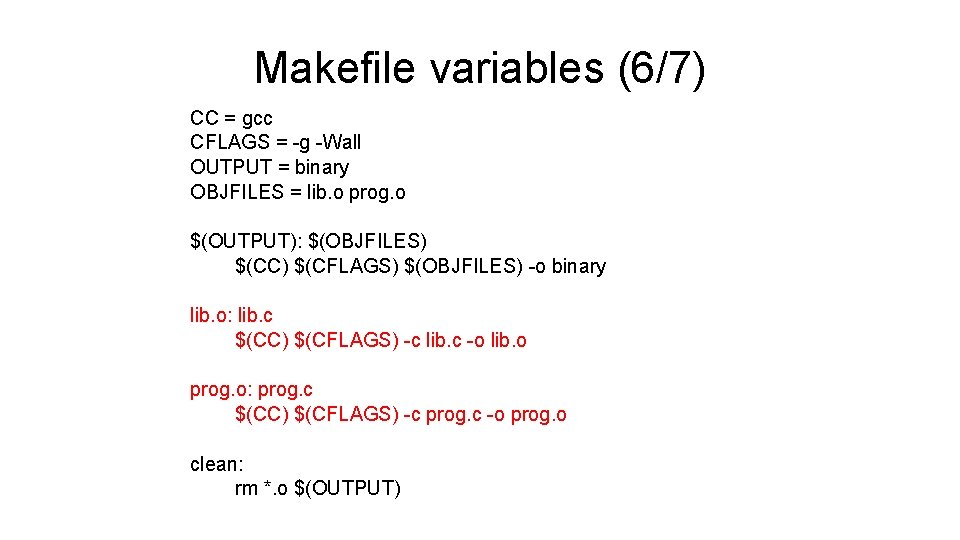

Makefile variables (6/7) CC = gcc CFLAGS = -g -Wall OUTPUT = binary OBJFILES = lib. o prog. o $(OUTPUT): $(OBJFILES) $(CC) $(CFLAGS) $(OBJFILES) -o binary lib. o: lib. c $(CC) $(CFLAGS) -c lib. c -o lib. o prog. o: prog. c $(CC) $(CFLAGS) -c prog. c -o prog. o clean: rm *. o $(OUTPUT)

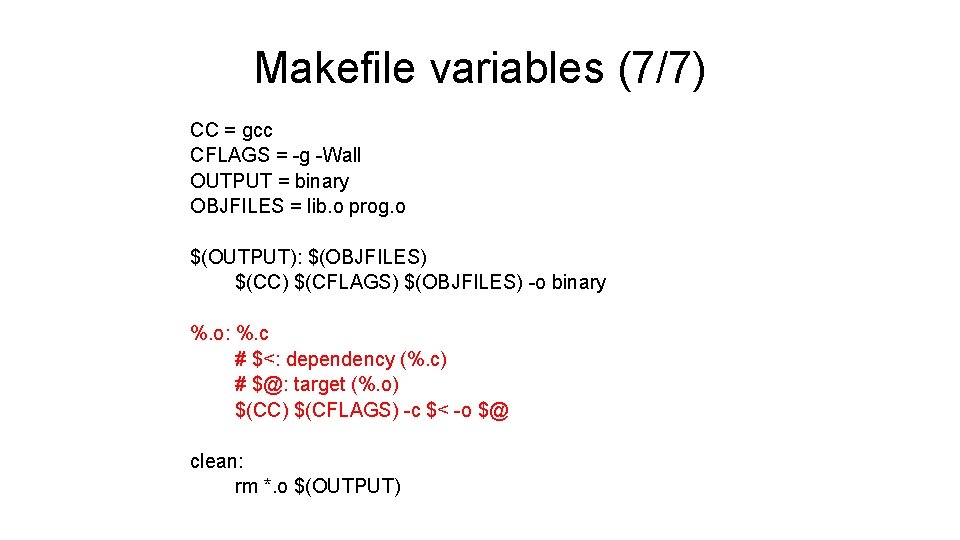

Makefile variables (7/7) CC = gcc CFLAGS = -g -Wall OUTPUT = binary OBJFILES = lib. o prog. o $(OUTPUT): $(OBJFILES) $(CC) $(CFLAGS) $(OBJFILES) -o binary %. o: %. c # $<: dependency (%. c) # $@: target (%. o) $(CC) $(CFLAGS) -c $< -o $@ clean: rm *. o $(OUTPUT)

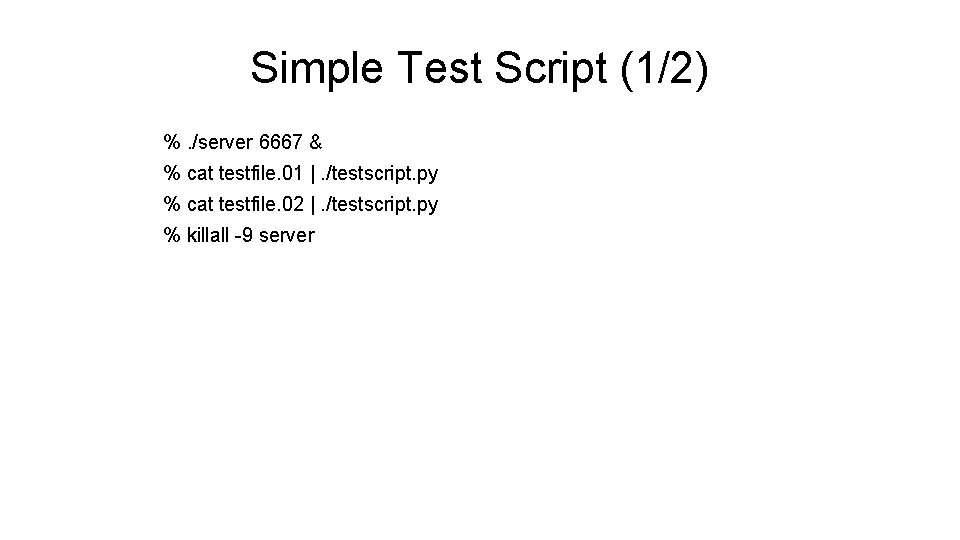

Simple Test Script (1/2) %. /server 6667 & % cat testfile. 01 |. /testscript. py % cat testfile. 02 |. /testscript. py % killall -9 server

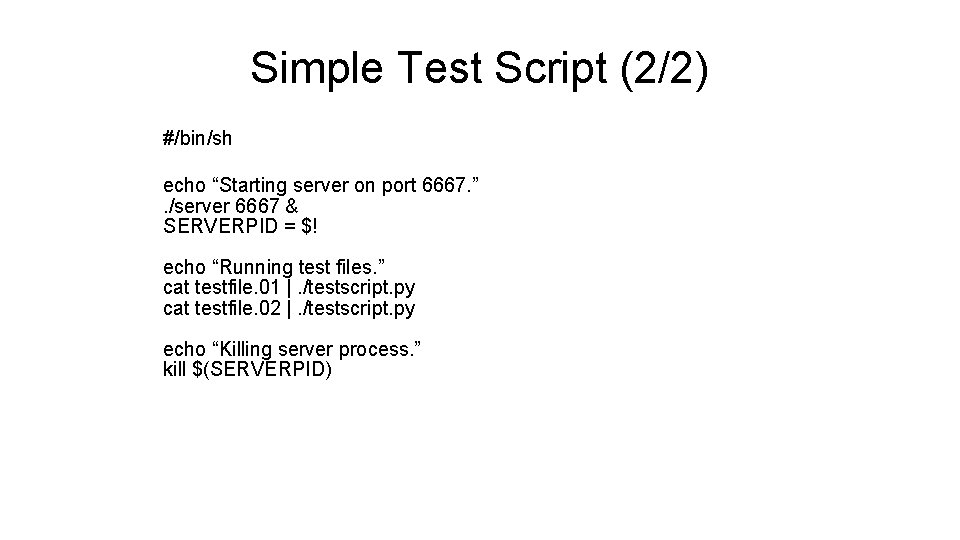

Simple Test Script (2/2) #/bin/sh echo “Starting server on port 6667. ”. /server 6667 & SERVERPID = $! echo “Running test files. ” cat testfile. 01 |. /testscript. py cat testfile. 02 |. /testscript. py echo “Killing server process. ” kill $(SERVERPID)

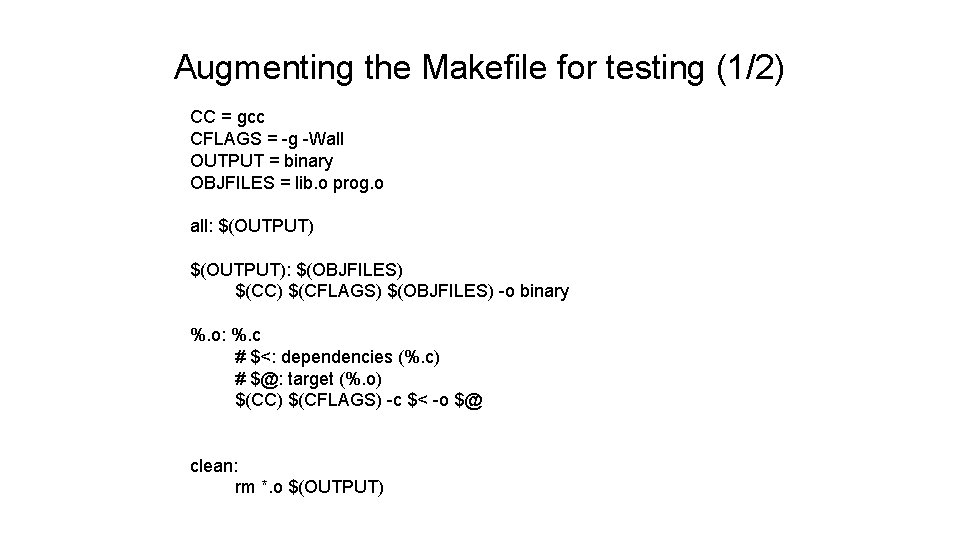

Augmenting the Makefile for testing (1/2) CC = gcc CFLAGS = -g -Wall OUTPUT = binary OBJFILES = lib. o prog. o all: $(OUTPUT): $(OBJFILES) $(CC) $(CFLAGS) $(OBJFILES) -o binary %. o: %. c # $<: dependencies (%. c) # $@: target (%. o) $(CC) $(CFLAGS) -c $< -o $@ clean: rm *. o $(OUTPUT)

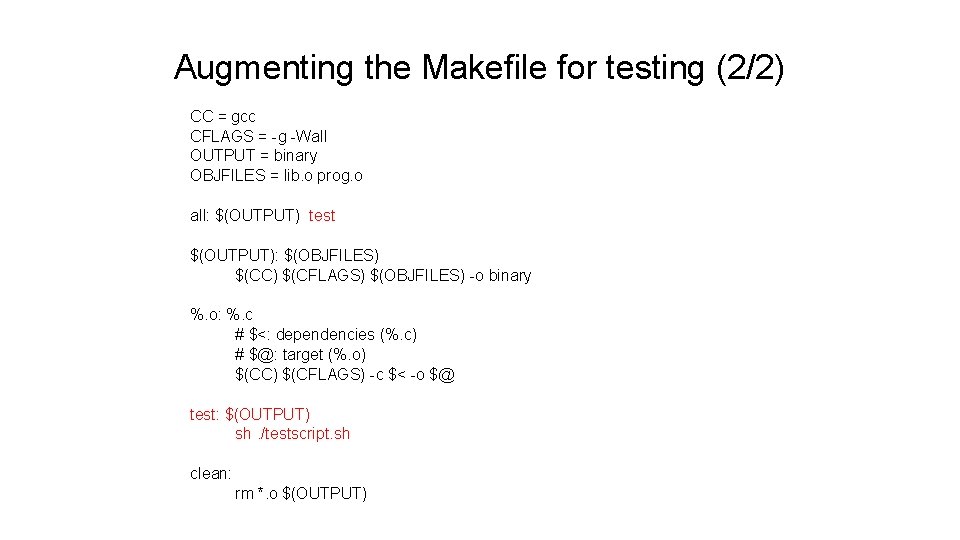

Augmenting the Makefile for testing (2/2) CC = gcc CFLAGS = -g -Wall OUTPUT = binary OBJFILES = lib. o prog. o all: $(OUTPUT) test $(OUTPUT): $(OBJFILES) $(CC) $(CFLAGS) $(OBJFILES) -o binary %. o: %. c # $<: dependencies (%. c) # $@: target (%. o) $(CC) $(CFLAGS) -c $< -o $@ test: $(OUTPUT) sh. /testscript. sh clean: rm *. o $(OUTPUT)

Using the Makefile % make test % make clean • Know more Google – “makefile example” – “makefile template” – “make tutorial” – Chapter 3 of Dave Andersen’s notes

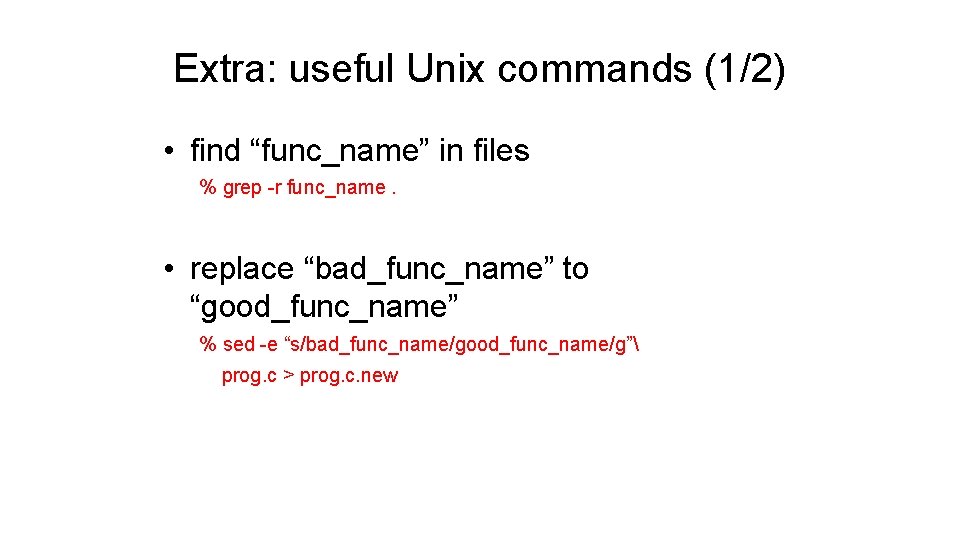

Extra: useful Unix commands (1/2) • find “func_name” in files % grep -r func_name. • replace “bad_func_name” to “good_func_name” % sed -e “s/bad_func_name/good_func_name/g” prog. c > prog. c. new

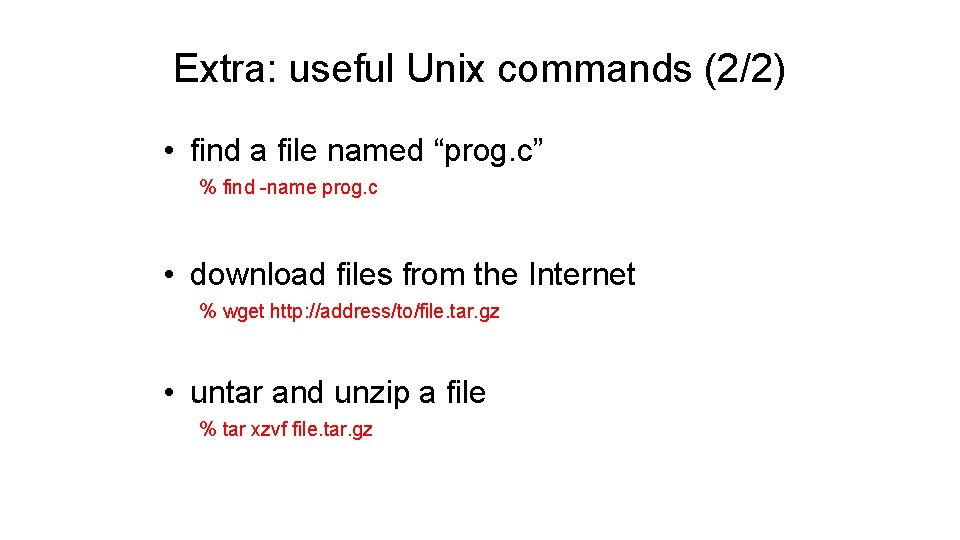

Extra: useful Unix commands (2/2) • find a file named “prog. c” % find -name prog. c • download files from the Internet % wget http: //address/to/file. tar. gz • untar and unzip a file % tar xzvf file. tar. gz

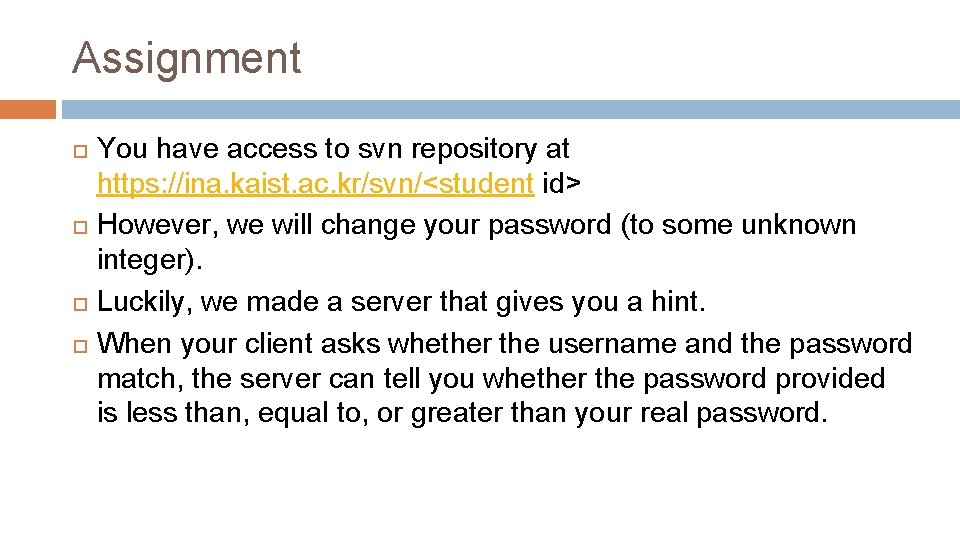

Assignment You have access to svn repository at https: //ina. kaist. ac. kr/svn/<student id> However, we will change your password (to some unknown integer). Luckily, we made a server that gives you a hint. When your client asks whether the username and the password match, the server can tell you whether the password provided is less than, equal to, or greater than your real password.

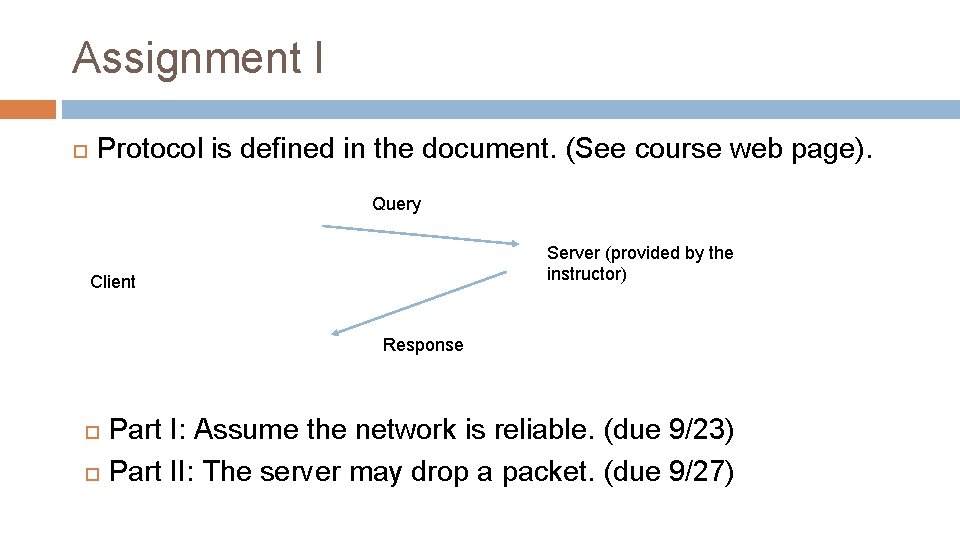

Assignment I Protocol is defined in the document. (See course web page). Query Server (provided by the instructor) Client Response Part I: Assume the network is reliable. (due 9/23) Part II: The server may drop a packet. (due 9/27)

- Slides: 57