NEOPLASIA DIFFERENCE BETWEEN BENIGN MALIGNANT TUMORS ROUTES OF

NEOPLASIA • DIFFERENCE BETWEEN BENIGN & MALIGNANT TUMORS • ROUTES OF SPREAD OF CANCER • GRADING & STAGING OF CANCER

Definition of neoplasm ‘A mass of tissue formed as a result of abnormal, excessive, uncoordinated, autonomous and purposeless proliferation of cells even after cessation of stimulus for growth which caused it’.

Neoplasms may be ‘benign’ or ‘malignant. ‘Benign’ when they are slow-growing and localised without causing much difficulty to the host ‘Malignant’ when they proliferate rapidly, spread throughout the body and may eventually cause death of the host.

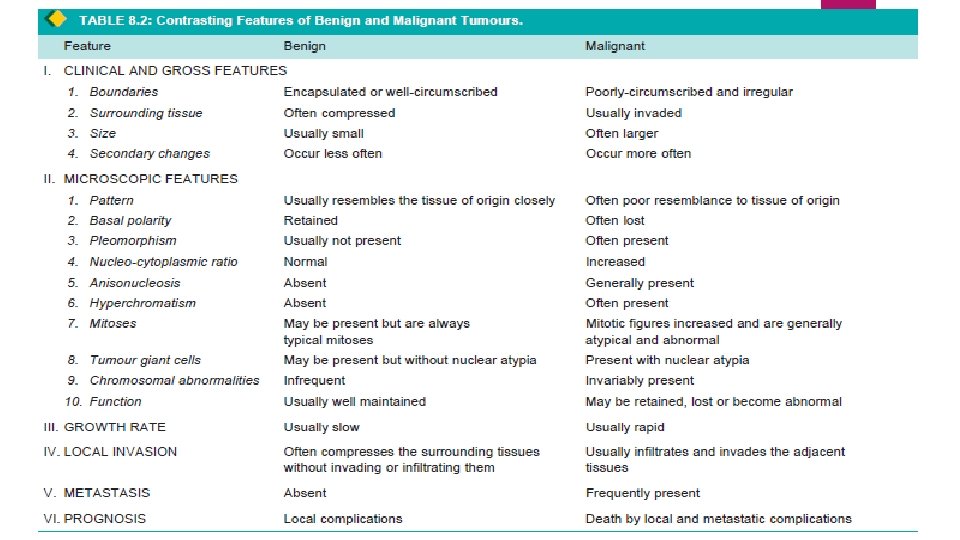

Majority of neoplasms can be categorised clinically and morphologically into benign and malignant on the basis of certain characteristics listed below. Characteristics of tumours are: I. Rate of growth II. Cancer phenotype and stem cells III. Clinical and gross features IV. Microscopic features V. Local invasion (Direct spread) VI. Metastasis (Distant spread).

I. RATE OF GROWTH The tumour cells generally proliferate more rapidly than the normal cells. In general, benign tumours grow slowly and malignant tumours rapidly. The rate at which the tumour enlarges depends upon 2 main factors: 1. Rate of cell production, growth fraction and rate of cell loss 2. Degree of differentiation of the tumour.

1. Rate of cell production, growth fraction and rate of cell loss. Rate of growth of a tumour depends upon 3 important parameters: i) doubling time of tumour cells, ii) number of cells remaining in proliferative pool (growth fraction), and iii) rate of loss of tumour cells by cell shedding.

2. Degree of differentiation. Rate of growth of malignant tumour is directly proportionate to the degree of differentiation. Poorly differentiated tumours show aggressive growth pattern as compared to better differentiated tumours.

II. CANCER PHENOTYPE AND STEM CELLS Normally growing cells in an organ are related to the neighbouring cells—they grow under normal growth controls, perform their assigned function and there is a balance between the rate of cell proliferation and the rate of cell death including cell suicide (i. e. apoptosis). Thus normal cells are socially desirable.

Cancer cells exhibit antisocial behaviour as under: i) Cancer cells disobey the growth controlling signals in the body and proliferate rapidly. ii) Cancer cells escape death signals and achieve immortality. iii) Imbalance between cell proliferation and cell death in cancer causes excessive growth. iv) Cancer cells lose properties of differentiation and thus perform little or no function. v) Due to loss of growth controls, cancer cells are genetically unstable and develop newer mutations. vi) Cancer cells overrun their neighbouring tissue and invade locally. vii) Cancer cells have the ability to travel from the site of origin to other sites in the body where they colonise and establish distant metastasis.

III. CLINICAL AND GROSS FEATURES Clinically, Benign tumours are slow growing, and depending upon the location, may remain asymptomatic (e. g. subcutaneous lipoma), or may produce serious symptoms (e. g. meningioma in the nervous system). Malignant tumours grow rapidly, may ulcerate on the surface, invade locally into deeper tissues, may spread to distant sites (metastasis), and also produce systemic features such as weight loss, anorexia and anemia. Two of the cardinal clinical features of malignant tumours are: invasiveness and metastasis.

Gross appearance Certain distinctive features characterise almost all tumours compared to neighbouring normal tissue of origin They have a different colour, texture and consistency. Gross terms such as papillary, fungating, infiltrating, haemorrhagic, ulcerative and cystic are used to describe the macroscopic appearance of the tumours.

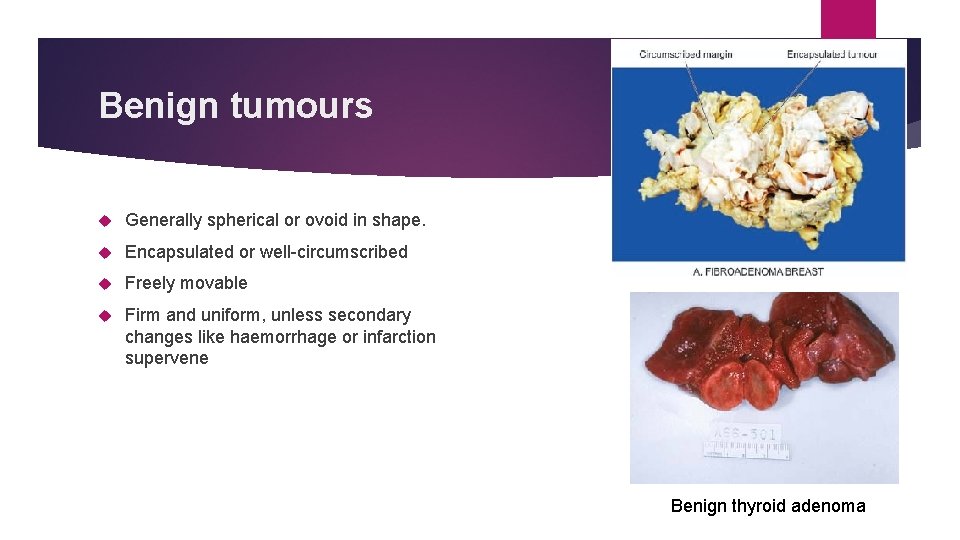

Benign tumours Generally spherical or ovoid in shape. Encapsulated or well-circumscribed Freely movable Firm and uniform, unless secondary changes like haemorrhage or infarction supervene Benign thyroid adenoma

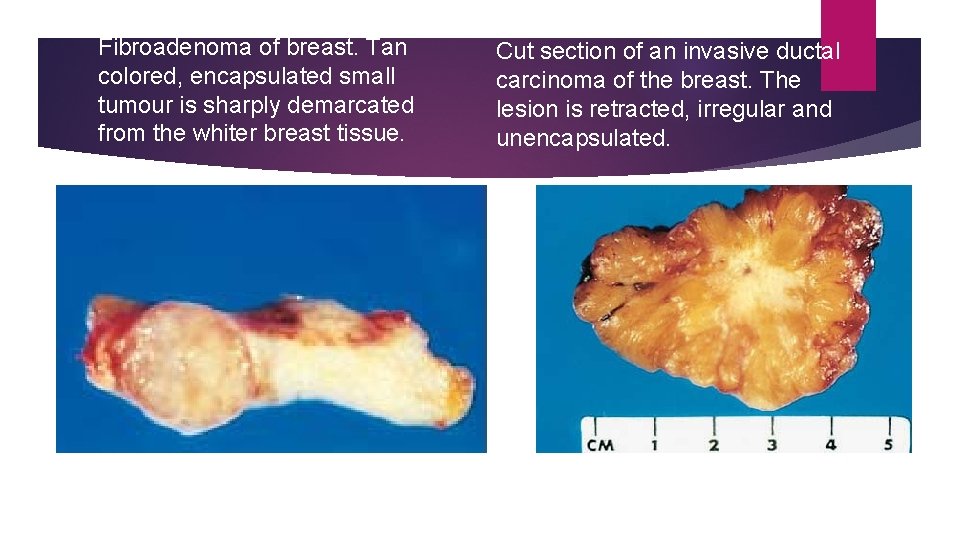

Malignant tumours Irregular in shape, poorly-circumscribed and extend into the adjacent tissues. Secondary changes like haemorrhage, infarction and ulceration are seen more often. Sarcomas typically have fish-flesh like consistency Carcinomas are generally firm.

Fibroadenoma of breast. Tan colored, encapsulated small tumour is sharply demarcated from the whiter breast tissue. Cut section of an invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. The lesion is retracted, irregular and unencapsulated.

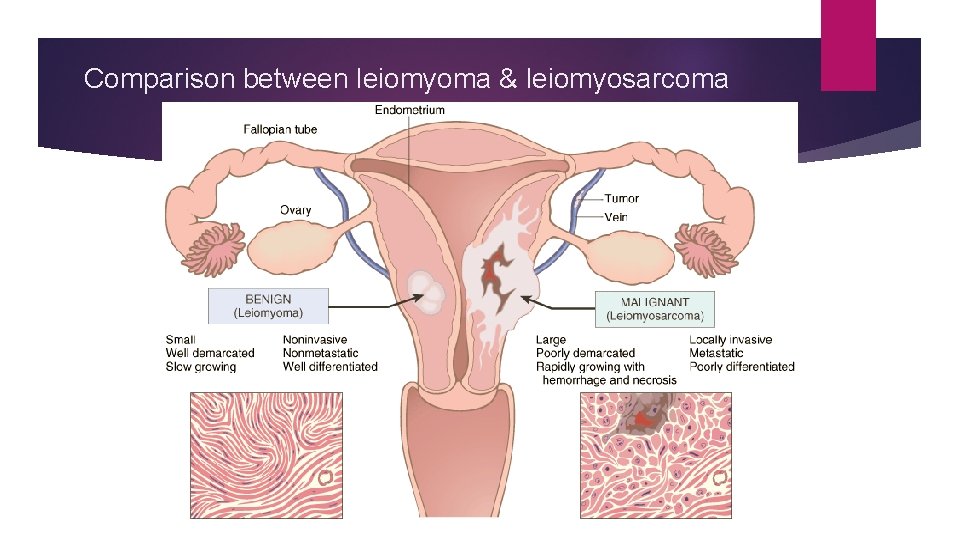

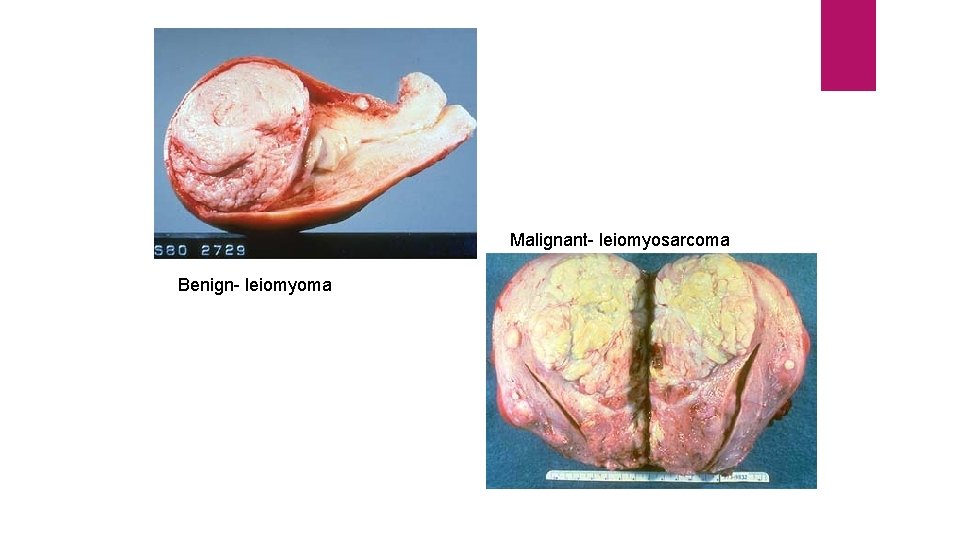

Comparison between leiomyoma & leiomyosarcoma

Malignant- leiomyosarcoma Benign- leiomyoma

IV. MICROSCOPIC FEATURES For recognising and classifying the tumours, the microscopic characteristics of tumour cells are of greatest importance. These features which are appreciated in histologic sections are: 1. microscopic pattern 2. cytomorphology of neoplastic cells (differentiation and anaplasia) 3. tumour angiogenesis and stroma 4. inflammatory reaction.

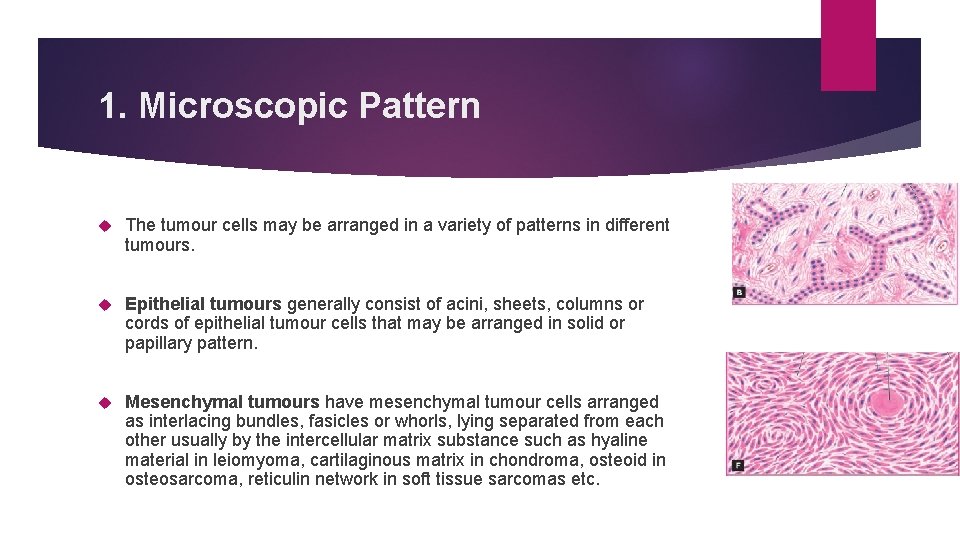

1. Microscopic Pattern The tumour cells may be arranged in a variety of patterns in different tumours. Epithelial tumours generally consist of acini, sheets, columns or cords of epithelial tumour cells that may be arranged in solid or papillary pattern. Mesenchymal tumours have mesenchymal tumour cells arranged as interlacing bundles, fasicles or whorls, lying separated from each other usually by the intercellular matrix substance such as hyaline material in leiomyoma, cartilaginous matrix in chondroma, osteoid in osteosarcoma, reticulin network in soft tissue sarcomas etc.

Leiomyoma

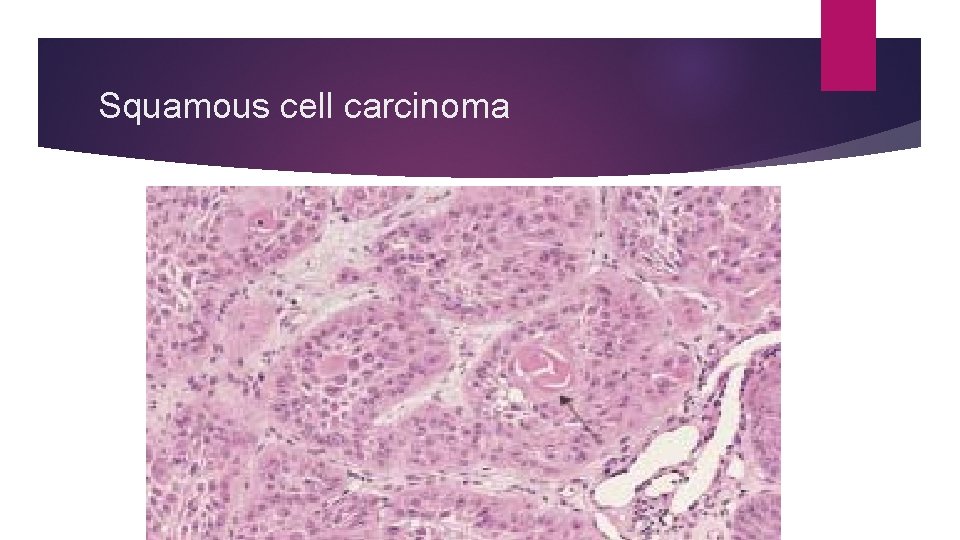

Squamous cell carcinoma

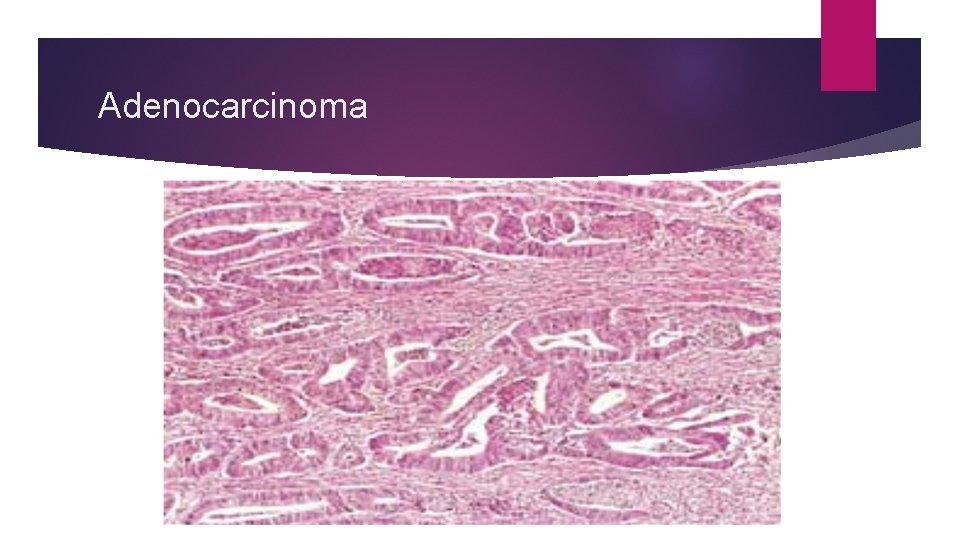

Adenocarcinoma

Certain tumours have mixed patterns e. g. teratoma arising from totipotent cells, pleomorphic adenoma of salivary gland (mixed salivary tumour), fibroadenoma of the breast, carcinosarcoma of the uterus and various other combinations of tumour types. Haematopoietic tumours such as leukaemias and lymphomas often have none or little stromal support.

2. Cytomorphology of Neoplastic Cells (Differentiation and Anaplasia) Differentiation is defined as the extent of morphological and functional resemblance of parenchymal tumour cells to corresponding normal cells. If the deviation of neoplastic cell in structure and function is minimal as compared to normal cell, the tumour is described as ‘well-differentiated’ such as most benign and low-grade malignant tumours. ‘Poorly differentiated’, ‘undifferentiated’ or ‘dedifferentiated’ are synonymous terms for poor structural and functional resemblance to corresponding normal cell.

Anaplasia is lack of differentiation Characteristic feature of most malignant tumours. Depending upon the degree of differentiation, the extent of anaplasia is also variable i. e. poorly differentiated malignant tumours have high degree of anaplasia. As a result of anaplasia, noticeable morphological and functional alterations in the neoplastic cells are observed.

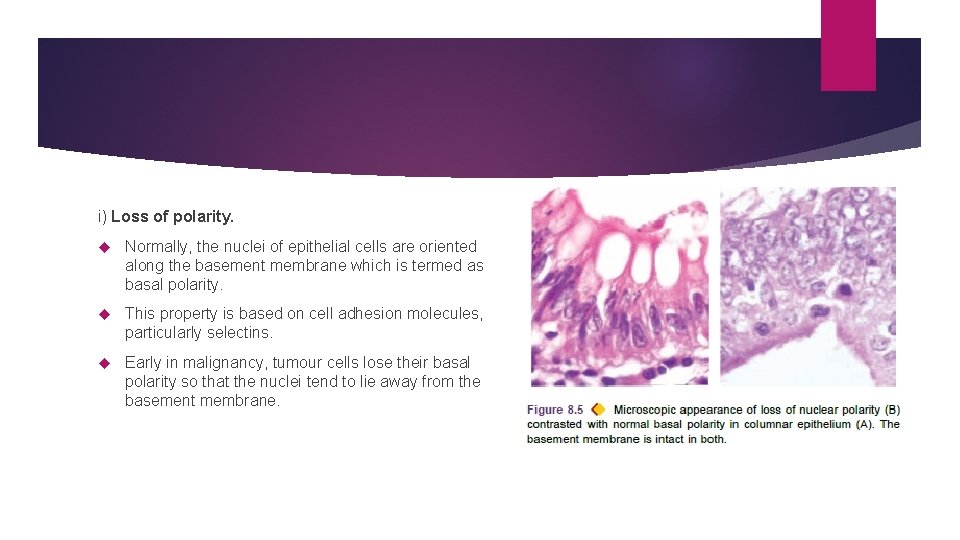

i) Loss of polarity. Normally, the nuclei of epithelial cells are oriented along the basement membrane which is termed as basal polarity. This property is based on cell adhesion molecules, particularly selectins. Early in malignancy, tumour cells lose their basal polarity so that the nuclei tend to lie away from the basement membrane.

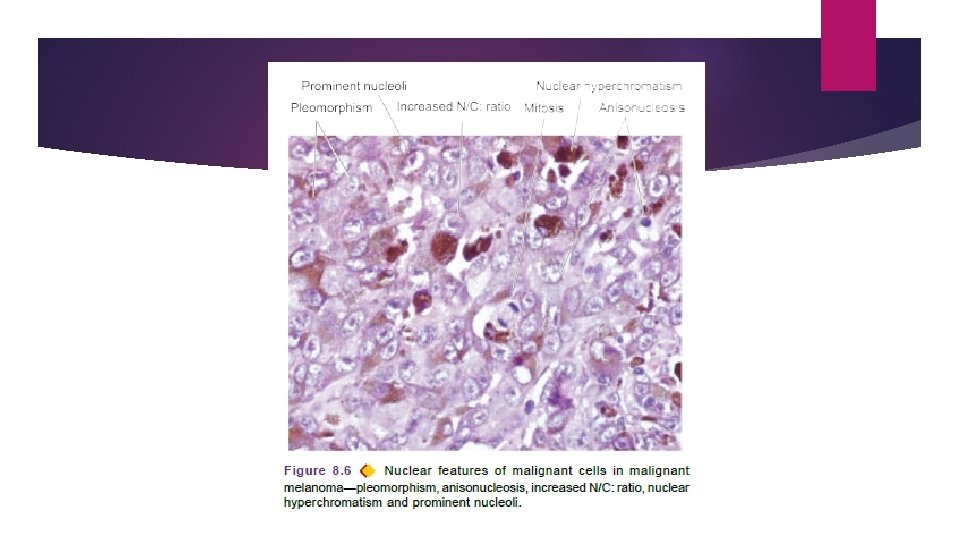

ii) Pleomorphism means variation in size and shape of the tumour cells. Extent of cellular pleomorphism generally correlates with the degree of anaplasia. Tumour cells are often bigger than normal but in some tumours they can be of normal size or smaller than normal. iii) N: C ratio. Nuclei are enlarged disproportionate to the cell size so that the nucleocytoplasmic ratio is increased from normal 1: 5 to 1: 1. iv) Anisonucleosis. Nuclei show variation in size and shape in malignant tumour cells.

v) Hyperchromatism. Characteristically, the nuclear chromatin of malignant cell is increased and coarsely clumped. Due to increase in the amount of nucleoprotein resulting in dark-staining nuclei, referred to as hyperchromatism. Nuclear shape may vary, nuclear membrane may be irregular and nuclear chromatin is clumped along the nuclear membrane.

vi) Nucleolar changes. Malignant cells frequently have a prominent nucleolus or nucleoli in the nucleus reflecting increased nucleoprotein synthesis.

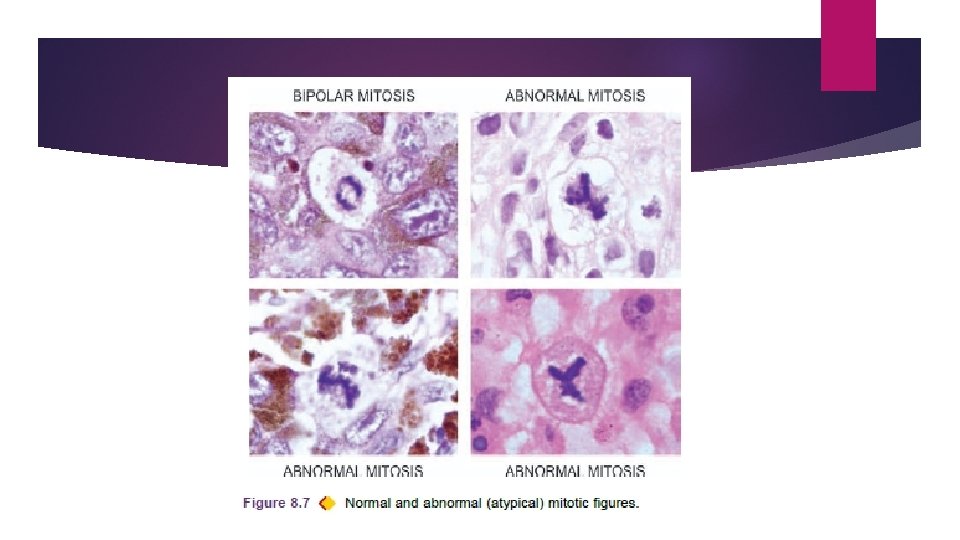

vii) Mitotic figures. Normal mitotic figures may be seen in some non-neoplastic proliferating cells (e. g. haematopoietic cells of the bone marrow, intestinal epithelium, hepatocytes etc), in certain benign tumours and some low grade malignant tumours; in sections they are seen as a dark band of dividing chromatin at two poles of the nuclear spindle. Abnormal or atypical mitotic figures are important in malignant tumours and are identified as tripolar, quadripolar and multipolar spindles in malignant tumour cells.

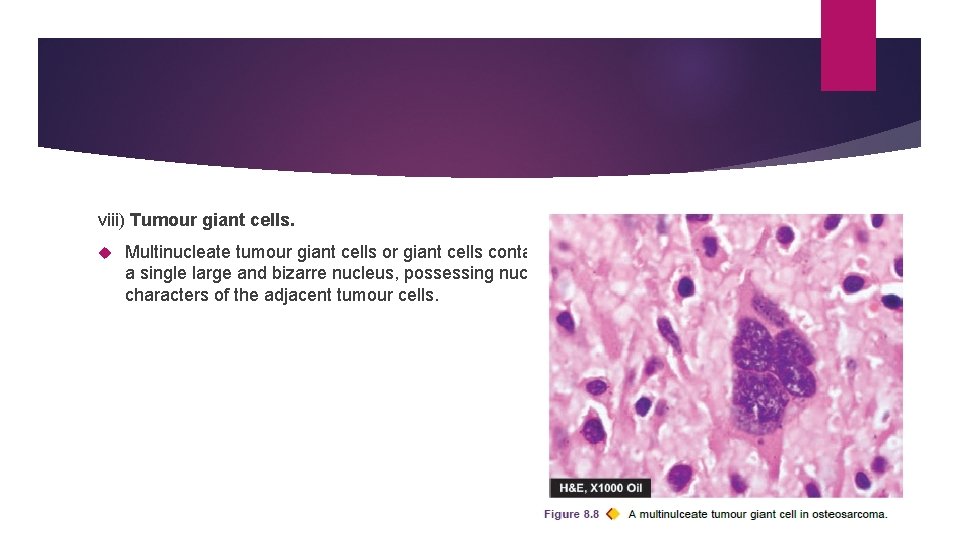

viii) Tumour giant cells. Multinucleate tumour giant cells or giant cells containing a single large and bizarre nucleus, possessing nuclear characters of the adjacent tumour cells.

ix) Functional (Cytoplasmic) changes. The functional abnormality in neoplasms may be quantitative, qualitative, or both. Benign tumours and better-differentiated malignant tumours continue to function well qualitatively, though there may be quantitative abnormality in the product. e. g. large or small amount of collagen produced by benign tumours of fibrous tissue, keratin formation in welldifferentiated squamous cell carcinoma, absence of keratin in anaplastic squamous cell carcinoma.

x) Chromosomal abnormalities are more marked in more malignant tumours. Most malignant tumours show DNA aneuploidy, often in the form of an increase in the number of chromosomes, reflected morphologically by the increase in the size of nuclei. Examples: presence of Philadelphia chromosome of chronic myeloid leukaemia, Burkitt’s lymphoma, acute lymphoid leukaemia, multiple myeloma, retinoblastoma, oat cell carcinoma, Wilms’ tumour etc.

3. Tumour Angiogenesis and Stroma Connective tissue along with its vascular network forms the supportive framework on which the parenchymal tumour cells grow and receive nourishment. Stroma may have nerves and metaplastic bone or cartilage but no lymphatics.

TUMOUR ANGIOGENESIS. In order to provide nourishment to growing tumour, new blood vessels are formed from pre-existing ones (angiogenesis). This takes place under the influence of angiogenic factors elaborated by tumour cells such as vascular endothelium growth factor (VEGF).

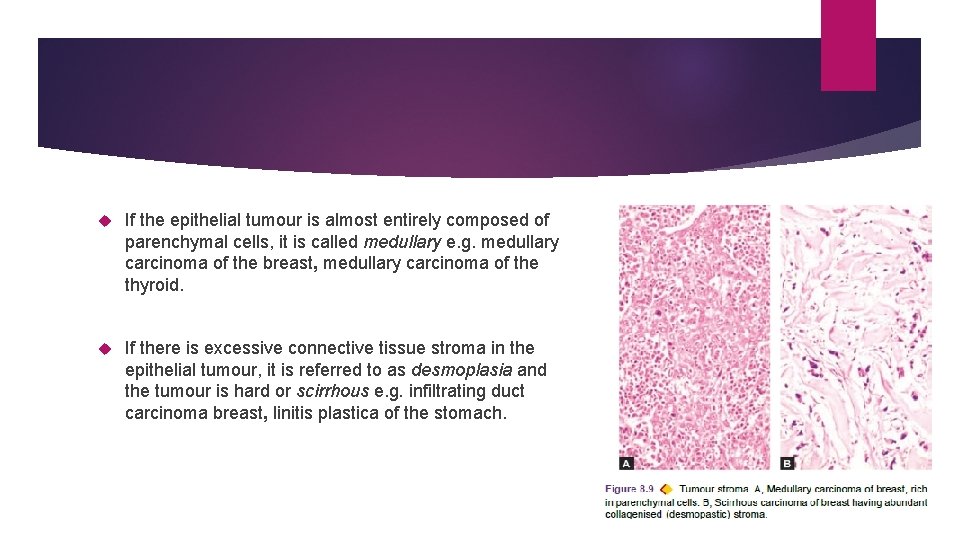

TUMOUR STROMA. Collagenous tissue in the stroma may be scanty or excessive. In the former case tumour is soft and fleshy (e. g. in sarcomas, lymphomas), latter case tumour is hard and gritty (e. g. infiltrating duct carcinoma breast). Growth of fibrous tissue in tumour is stimulated by basic fibroblast growth factor (b. FGF) elaborated by tumour cells.

If the epithelial tumour is almost entirely composed of parenchymal cells, it is called medullary e. g. medullary carcinoma of the breast, medullary carcinoma of the thyroid. If there is excessive connective tissue stroma in the epithelial tumour, it is referred to as desmoplasia and the tumour is hard or scirrhous e. g. infiltrating duct carcinoma breast, linitis plastica of the stomach.

4. Inflammatory Reaction At times, prominent inflammatory reaction is present in and around the tumours. Result of ulceration in the cancer when there is secondary infection; may be acute or chronic. Some tumours show chronic inflammatory reaction, chiefly of lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages, and in some instances granulomatous reaction, in the absence of ulceration. Due to cell-mediated immunologic response by the host in an attempt to destroy the tumour. Examples: seminoma testis, malignant melanoma of the skin, lymphoepithelioma of the throat, medullary carcinoma of the breast, choriocarcinoma, Warthin’s tumour of salivary glands etc.

V. LOCAL INVASION (DIRECT SPREAD) BENIGN TUMOURS. Most benign tumours form encapsulated or circumscribed masses MALIGNANT TUMOURS. Malignant tumours also enlarge by expansion Some well-differentiated tumours may be partially encapsulated as well e. g. follicular carcinoma thyroid. But characteristically, they are distinguished from benign tumours by invasion, infiltration and destruction of the surrounding tissue, besides distant metastasis. that expand push aside the surrounding normal tissues without actually invading, infiltrating or metastasising.

Tumours invade via the route of least resistance. Cancers extend through tissue spaces, permeate lymphatics, blood vessels, perineural spaces and may penetrate a bone by growing through nutrient foramina. More commonly, the tumours invade thin walled capillaries and veins than thickwalled arteries. Dense compact collagen, elastic tissue and cartilage are some of the tissues which are sufficiently resistant to invasion by tumours.

VI. METASTASIS (DISTANT SPREAD) Metastasis (meta = transformation, stasis = residence) is defined as spread of tumour by invasion in such a way that discontinuous secondary tumour mass/masses are formed at the site of lodgement. Metastasis and invasiveness are the two most important features to distinguish malignant from benign tumours. Benign tumours do not metastasise while all the malignant tumours with a few exceptions like gliomas of the central nervous system and basal cell carcinoma of the skin, can metastasise.

Generally, larger, more aggressive and rapidly-growing tumours are more likely to metastasise. About one-third of malignant tumours at presentation have evident metastatic deposits while another 20% have occult metastasis.

Routes of Metastasis Cancers may spread to distant sites by following pathways: 1. Lymphatic spread 2. Haematogenous spread 3. Spread along body cavities and natural passages (Transcoelomic spread, along epithelium-lined surfaces, spread via cerebrospinal fluid, implantation).

1. LYMPHATIC SPREAD Carcinomas metastasise by lymphatic route Sarcomas haematogenous route. However, sarcomas may also spread by lymphatic pathway.

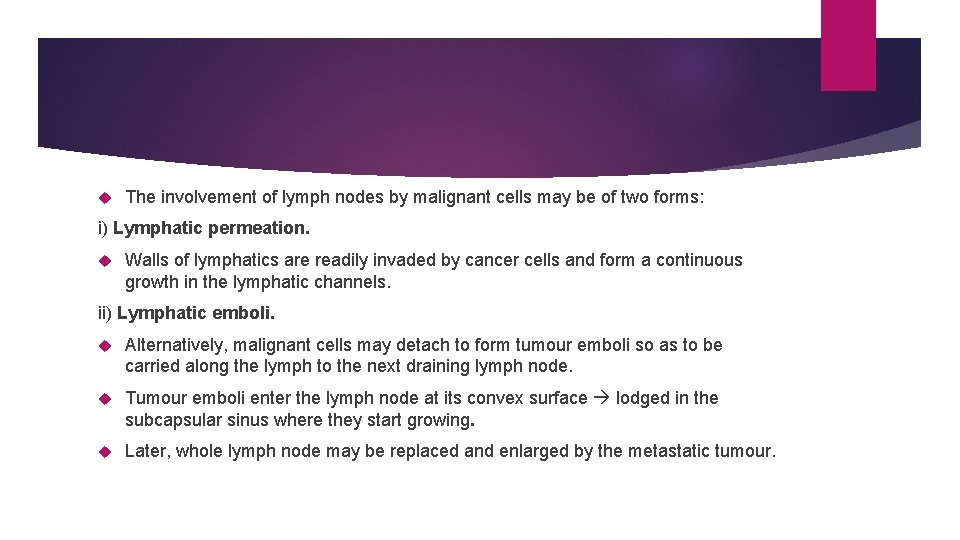

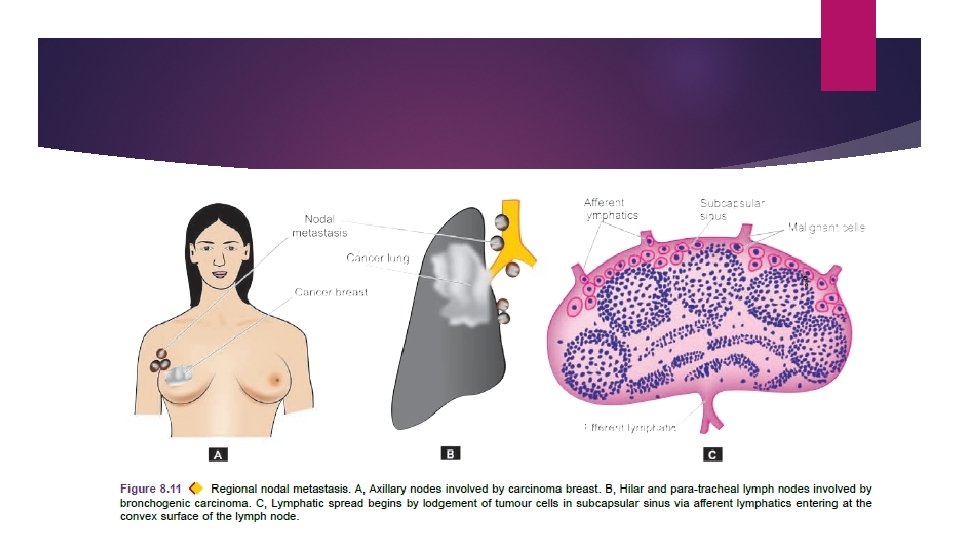

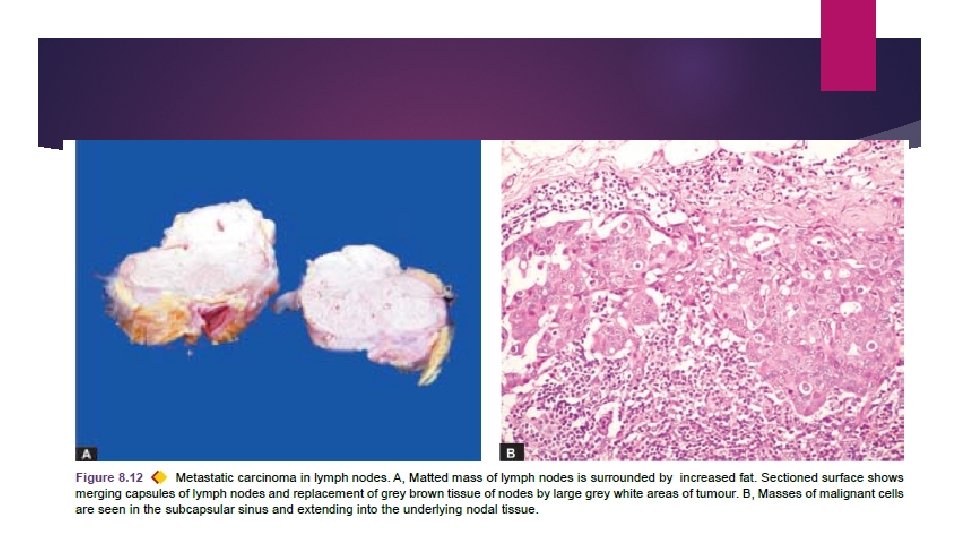

The involvement of lymph nodes by malignant cells may be of two forms: i) Lymphatic permeation. Walls of lymphatics are readily invaded by cancer cells and form a continuous growth in the lymphatic channels. ii) Lymphatic emboli. Alternatively, malignant cells may detach to form tumour emboli so as to be carried along the lymph to the next draining lymph node. Tumour emboli enter the lymph node at its convex surface lodged in the subcapsular sinus where they start growing. Later, whole lymph node may be replaced and enlarged by the metastatic tumour.

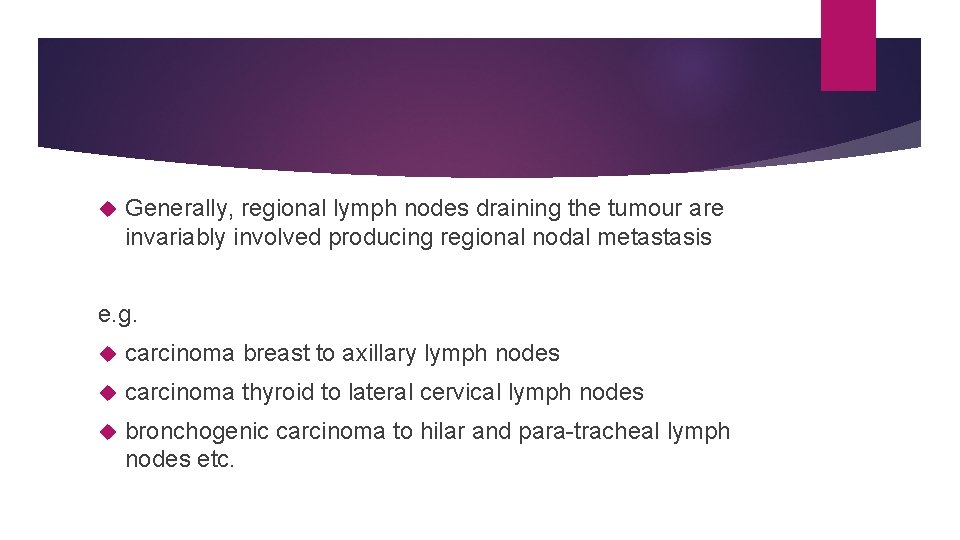

Generally, regional lymph nodes draining the tumour are invariably involved producing regional nodal metastasis e. g. carcinoma breast to axillary lymph nodes carcinoma thyroid to lateral cervical lymph nodes bronchogenic carcinoma to hilar and para-tracheal lymph nodes etc.

Regional lymphadenitis of sinus histiocytosis: All regional nodal enlargements are not due to nodal metastasis because necrotic products of tumour and antigens may also incite regional lymphadenitis of sinus histiocytosis. Skip metastasis: Sometimes lymphatic metastases do not develop first in the lymph node nearest to the tumour because of venous-lymphatic anastomoses or due to obliteration of lymphatics by inflammation or radiation.

Retrograde metastases: Due to obstruction of the lymphatics by tumour cells, the lymph flow is disturbed and tumour cells spread against the flow of lymph at unusual sites. e. g. metastasis of carcinoma prostate to the supraclavicular lymph nodes, metastatic deposits from bronchogenic carcinoma to the axillary lymph nodes. Virchow’s lymph node is nodal metastasis preferentially to supraclavicular lymph node from cancers of abdominal organs e. g. cancer stomach, colon, and gall bladder.

2. HAEMATOGENOUS SPREAD Blood-borne metastasis is the common route for sarcomas. Carcinomas lung, breast, thyroid, kidney, liver, prostate and ovary. Sites where blood-borne metastasis commonly occurs are: liver, lungs, brain, bones, kidney and adrenals. A few organs such as spleen, heart, and skeletal muscle generally do not allow tumour metastasis to grow.

Systemic veins drain blood into vena cavae from limbs, head and neck and pelvis. Cancers of these sites more often metastasise to the lungs. Portal veins drain blood from the bowel, spleen and pancreas into the liver. Tumours of these organs frequently have secondaries in the liver. Arterial spread of tumours is less likely because they are thick-walled and contain elastic tissue which is resistant to invasion.

Retrograde spread by blood route may occur at unusual sites due to retrograde spread after venous obstruction. Examples are vertebral metastases in cancers of the thyroid and prostate.

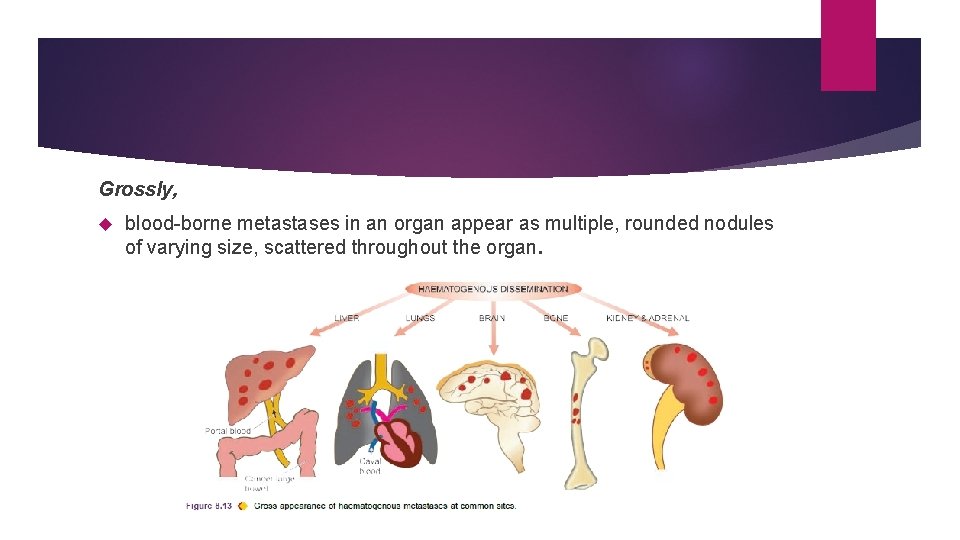

Grossly, blood-borne metastases in an organ appear as multiple, rounded nodules of varying size, scattered throughout the organ.

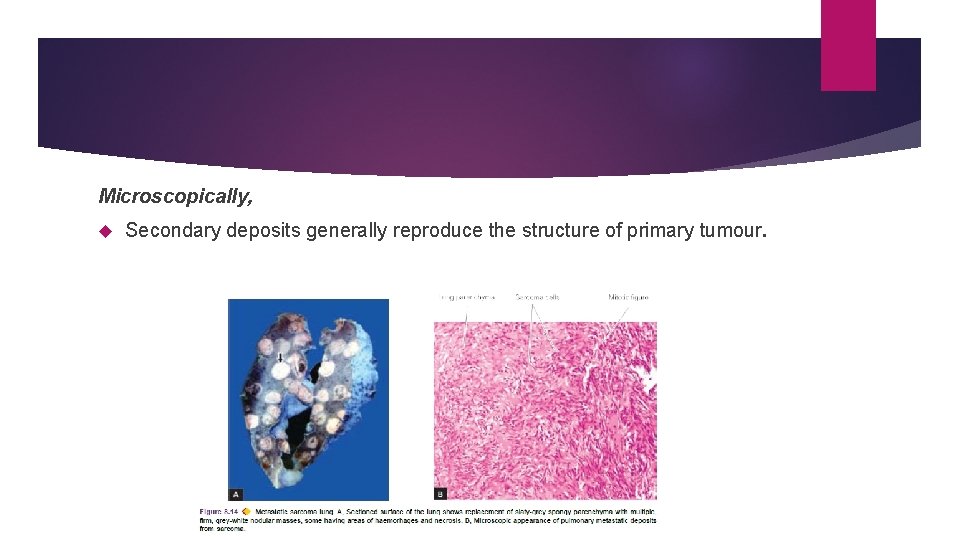

Microscopically, Secondary deposits generally reproduce the structure of primary tumour.

3. SPREAD ALONG BODY CAVITIES AND NATURAL PASSAGES. i) Transcoelomic spread. Certain cancers invade through the serosal wall of the coelomic cavity so that tumour fragments or clusters of tumour cells break off to be carried in the coelomic fluid and are implanted elsewhere in the body cavity. Peritoneal cavity (MC), pleural and pericardial cavities.

Examples of transcoelomic spread are: a) Carcinoma of the stomach seeding to both ovaries (Krukenberg tumour). b) Carcinoma of the ovary spreading to the entire peritoneal cavity without infiltrating the underlying organs. c) Pseudomyxoma peritonei is the gelatinous coating of the peritoneum from mucin-secreting carcinoma of the ovary or apppendix. d) Carcinoma of the bronchus and breast seeding to the pleura and pericardium.

ii) Spread along epithelium-lined surfaces. It is unusual because intact epithelium and mucus coat are quite resistant to penetration by tumour cells. a) the fallopian tube from the endometrium to the ovaries or vice -versa b) through the bronchus into alveoli c) through the ureters from the kidneys into lower urinary tract.

iii) Spread via cerebrospinal fluid. Malignant tumour of the ependyma and leptomeninges spread by release of tumour fragments and tumour cells into the CSF produce metastases at other sites in the central nervous system.

iv) Implantation. Rarely, tumour may spread by implantation by surgeon’s scalpel, needles, sutures, or may be implanted by direct contact such as transfer of cancer of the lower lip to the apposing upper lip.

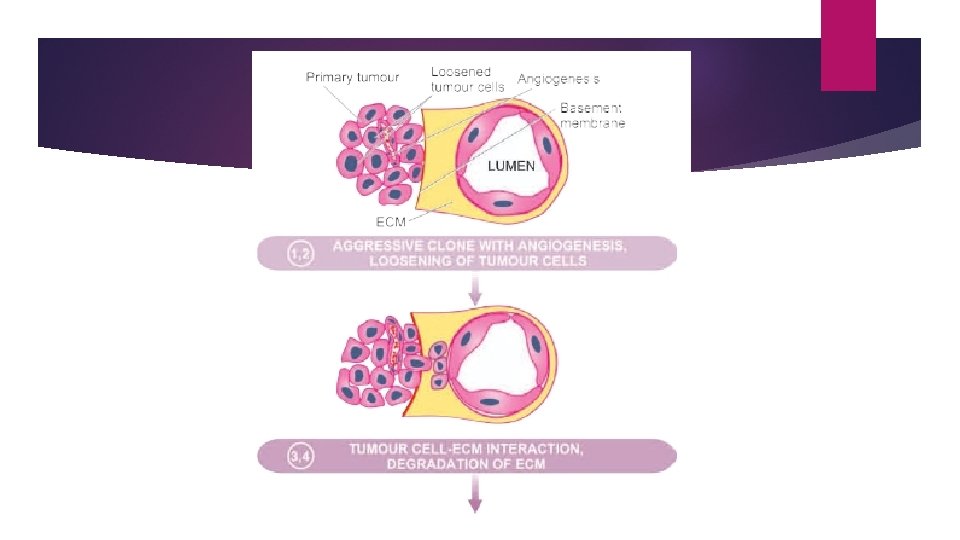

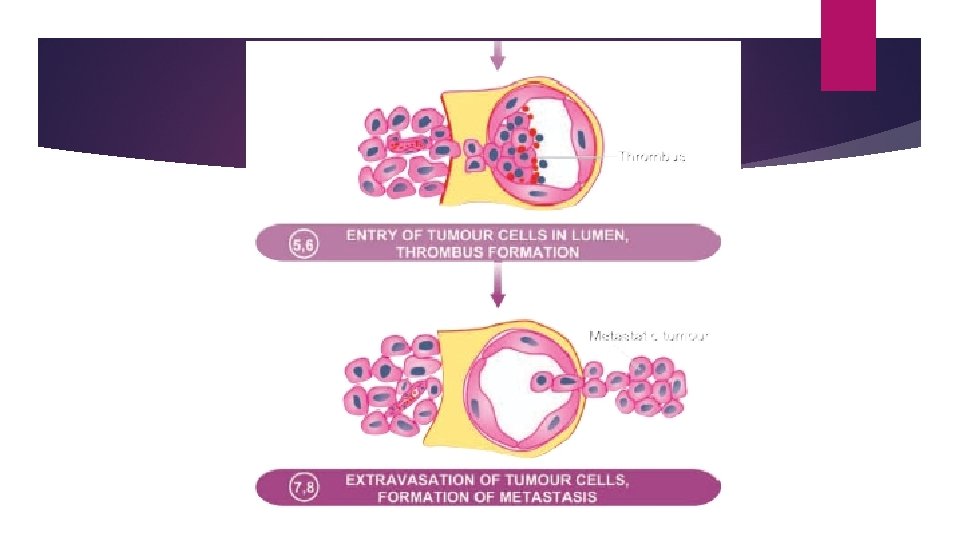

MECHANISM AND BIOLOGY OF INVASION AND METASTASIS The process involves passage through barriers before gaining access to the vascular lumen. This includes making the passage by the cancer cells by dissolution of extracellular matrix (ECM) at three levels— Ø At the basement membrane of tumour itself Ø at the level of interstitial connective tissue, and Ø at the basement membrane of microvasculature.

PROGNOSTIC MARKERS i) Clinical prognostic markers: Size Grade vascular invasion and nodal involvement by the tumour

ii) Molecular prognostic markers: indicative of poor prognosis are: a) expression of an oncogene by tumour cells (C-met); b) CD 44 molecule; c) oestrogen receptors; d) epidermal growth factor receptor; e) angiogenesis factors and degree of neovascularisation f) expression of metastasis associated gene or nucleic acid (MAGNA) in the DNA fragment in metastasising tumour.

GRADING AND STAGING OF CANCER ‘Grading’ and ‘staging’ are the two systems to predict tumour behaviour and guide therapy after a malignant tumour is detected. Grading is defined as the gross and microscopic degree of differentiation of the tumour. Staging means extent of spread of the tumour within the patient. Grading is histologic while staging is clinical.

Grading Cancers may be graded grossly and microscopically. Gross features like exophytic or fungating appearance are indicative of less malignant growth than diffusely infiltrating tumours. Grading is largely based on 2 important histologic features: the degree of anaplasia, and the rate of growth. Based on these features, cancers are categorised from grade I as the most differentiated, to grade III or IV as the most undifferentiated or anaplastic.

Broders’ grading: Grade I: Well-differentiated (less than 25% anaplastic cells). Grade II: Moderately-differentiated (25 -50% anaplastic cells). Grade III: Moderately-differentiated (50 -75% anaplastic cells). Grade IV: Poorly-differentiated or anaplastic (more than 75% anaplastic cells).

Grading of tumours has several shortcomings it is subjective and the degree of differentiation may vary from one area of tumour to the other. Pathologists grade cancers in descriptive terms (e. g. well-differentiated, undifferentiated, keratinising, non-keratinising etc) rather than giving the tumours grade numbers. More objective criteria for histologic grading include use of flow cytometry for mitotic cell counts, cell proliferation markers by immunohistochemistry, and by applying image morphometry for cancer cell and nuclear parameters.

Staging The extent of spread of cancers can be assessed by 3 ways — by clinical examination by investigations, and by pathologic examination of the tissue removed. Two important staging systems currently followed are: TNM staging and AJC staging.

TNM staging. T for primary tumour, N for regional nodal involvement, and M for distant metastases. For each of the 3 components namely T, N and M, numbers are added to indicate the extent of involvement, as under: T 0 to T 4: In situ lesion to largest and most extensive primary tumour. N 0 to N 3: No nodal involvement to widespread lymph node involvement. M 0 to M 2: No metastasis to disseminated haematogenous metastases.

AJC staging. American Joint Committee staging divides all cancers into stage 0 to IV Takes into account all the 3 components of the preceding system (primary tumour, nodal involvement and distant metastases) in each stage.

Currently, clinical staging of tumours does not rest on routine radiography (X-ray, ultrasound) and exploratory surgery but more modern techniques are available by which it is possible to ‘stage’ a malignant tumour by non-invasive techniques. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan based on tissue density for locating the local extent of tumour and its spread to other organs.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan facilitates distinction of benign and malignant tumour on the basis of biochemical and molecular processes in tumours. Radioactive tracer studies in vivo such as use of iodine isotope 125 bound to specific tumour antibodies is another method by which small number of tumour cells in the body can be detected by imaging of tracer substance bound to specific tumour antigen.

- Slides: 78