Neonatal intestinal atresia Ahmed Elrouby Lecturer of Pediatric

Neonatal intestinal atresia Ahmed Elrouby Lecturer of Pediatric Surgery

Golden points • Bilious vomiting is always abnormal. • Abdominal distention (scaphoid abdomen possible). • Delayed, scanty or no passage of meconium. • Polyhydramnios in mother. • Down's syndrome • Family history: • Hirschsprung's disease • Diabetic mother • Jejunal atresia

Duodenal obstruction Incidence: 1/6000 -1/10000 live births

Etiology • Malrotation (acute, chronic) • Annular pancreas • Duodenal atresia: complete /incomplete by diaphragm; Duodenal atresia is believed to occur from a failure of recanalization of the lumen of the duodenum at 8 -10 weeks' gestation with intact mesentry (≠ jejuno-ileal atresia which develops from vascular accident with deficient mesentry)

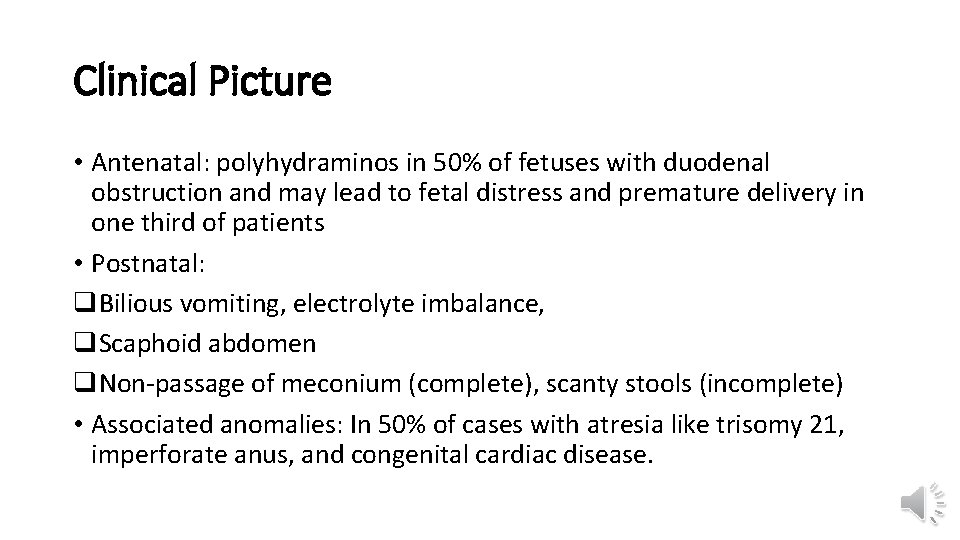

Clinical Picture • Antenatal: polyhydraminos in 50% of fetuses with duodenal obstruction and may lead to fetal distress and premature delivery in one third of patients • Postnatal: q. Bilious vomiting, electrolyte imbalance, q. Scaphoid abdomen q. Non-passage of meconium (complete), scanty stools (incomplete) • Associated anomalies: In 50% of cases with atresia like trisomy 21, imperforate anus, and congenital cardiac disease.

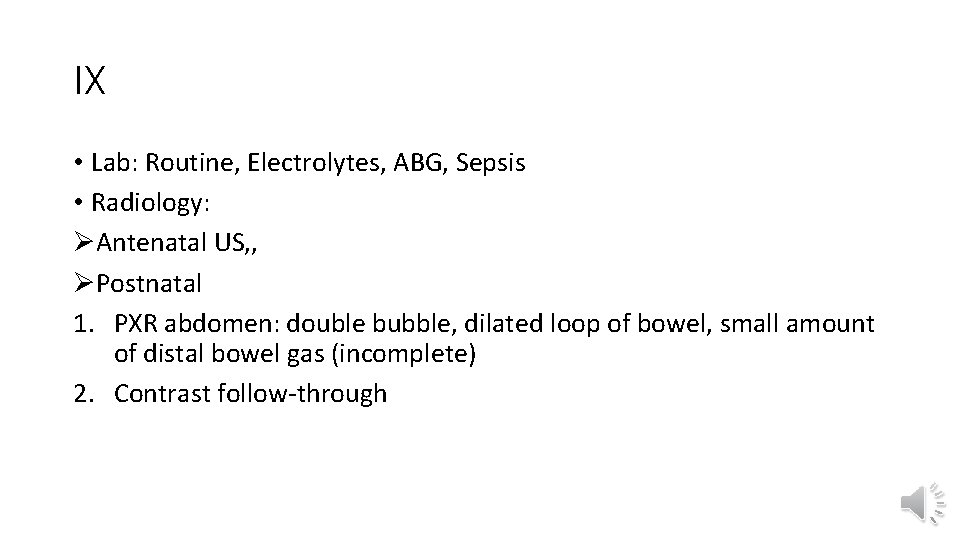

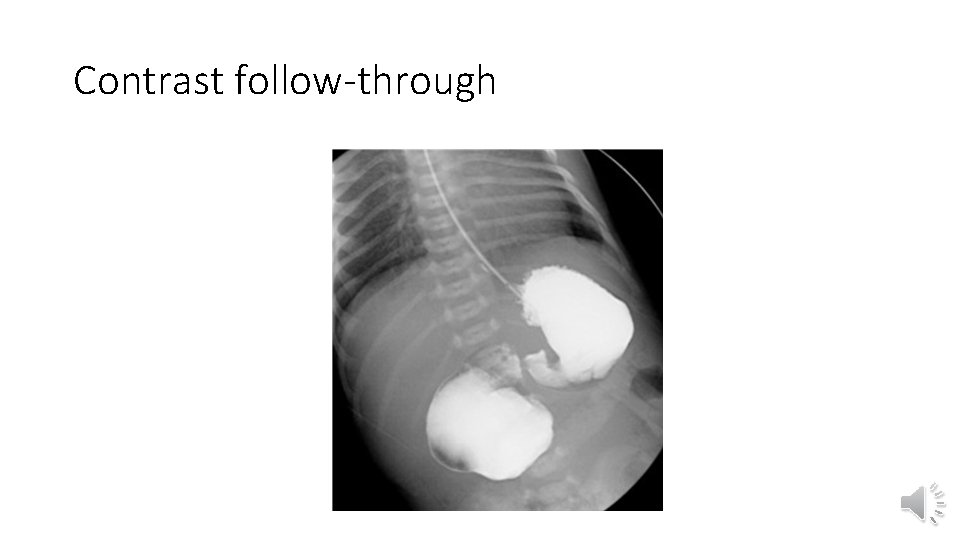

IX • Lab: Routine, Electrolytes, ABG, Sepsis • Radiology: ØAntenatal US, , ØPostnatal 1. PXR abdomen: double bubble, dilated loop of bowel, small amount of distal bowel gas (incomplete) 2. Contrast follow-through

Double bubble sign

Contrast follow-through

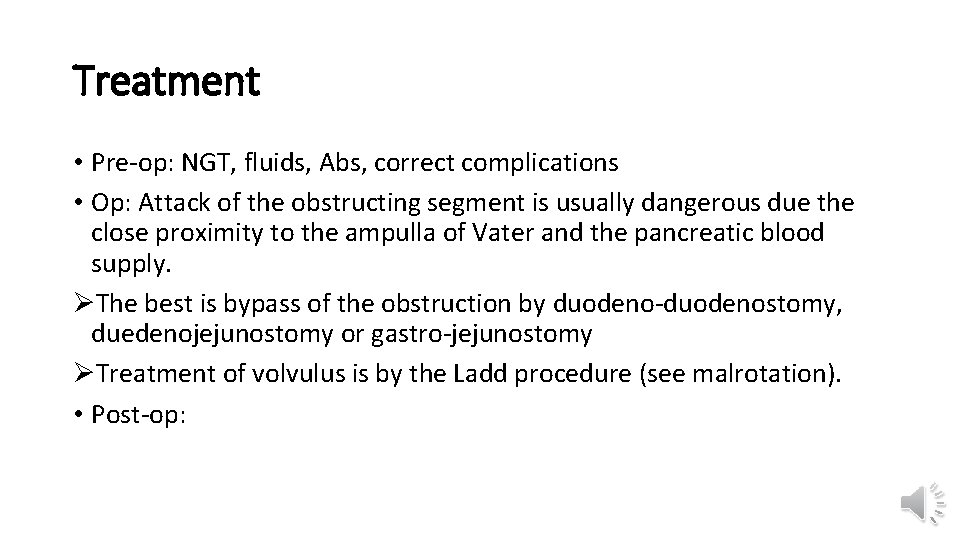

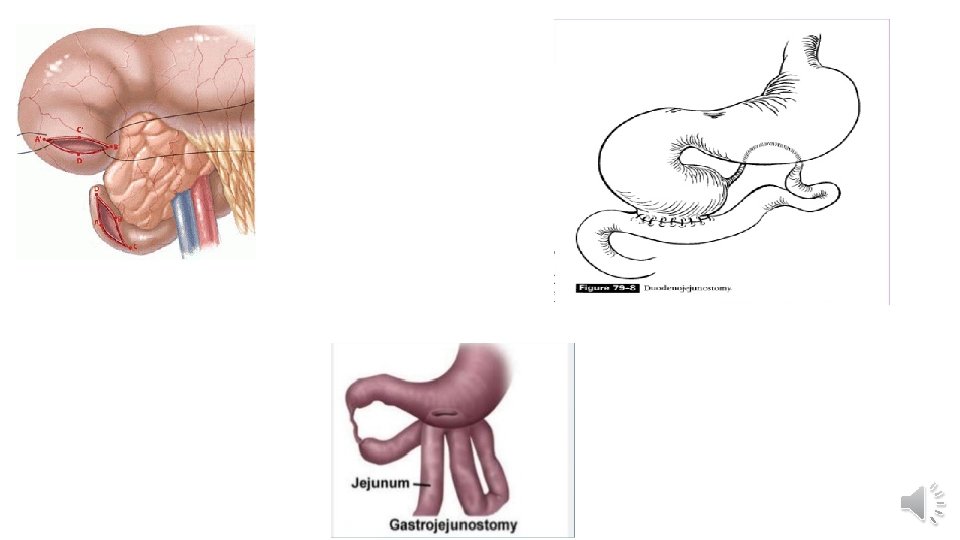

Treatment • Pre-op: NGT, fluids, Abs, correct complications • Op: Attack of the obstructing segment is usually dangerous due the close proximity to the ampulla of Vater and the pancreatic blood supply. ØThe best is bypass of the obstruction by duodeno-duodenostomy, duedenojejunostomy or gastro-jejunostomy ØTreatment of volvulus is by the Ladd procedure (see malrotation). • Post-op:

Malrotation, volvulus Ahmed Elrouby, MD

Incidence • Because of the potential for midgut volvulus and loss of the entire small bowel, malrotation represents perhaps the most feared cause for proximal small-bowel obstruction. • Midgut volvulus from malrotation is a life-threatening surgical emergency in the newborn. • Remember that malrotation is not synonymous with volvulus. Malrotation occurs in approximately 1 in 6000 newborns; Volvulus represents the acute twisting of the intestines upon their mesentery and can occur in a patient with malrotation due to the lack of normal fixation of the bowel to the retroperitoneum. • Patients who develop obstructive symptoms of malrotation usually present in the first month of life. Of those who are eventually symptomatic, 90% present in the first year of life.

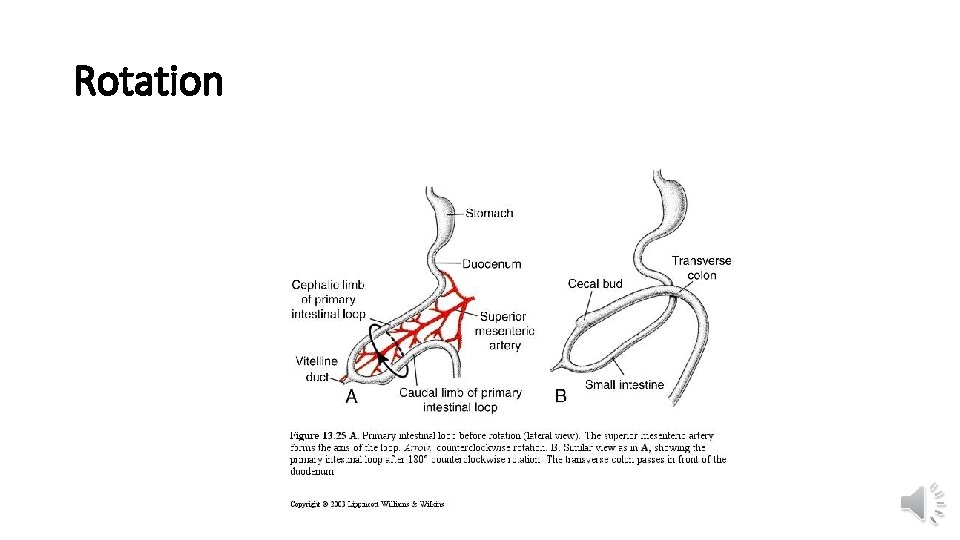

Embryology: Rotation • Malrotation results from a failure of the GI tract to complete its normal rotation as it returns to the abdominal cavity at 8 -10 weeks' gestation. • The bowel develops outside of the abdominal cavity as a single long loop of bowel based on the pedicle of the superior mesenteric vessels. As the bowel returns to the abdomen, the proximal small bowel returns first and the duodenum rotates underneath the superior mesenteric vessels to assume a retroperitoneal position. Rotation continues as the large bowel returns to the peritoneal cavity, rotating over the vascular pedicle to place the ileocecal valve in the right lower quadrant and establishing the hepatic and splenic flexures.

Rotation

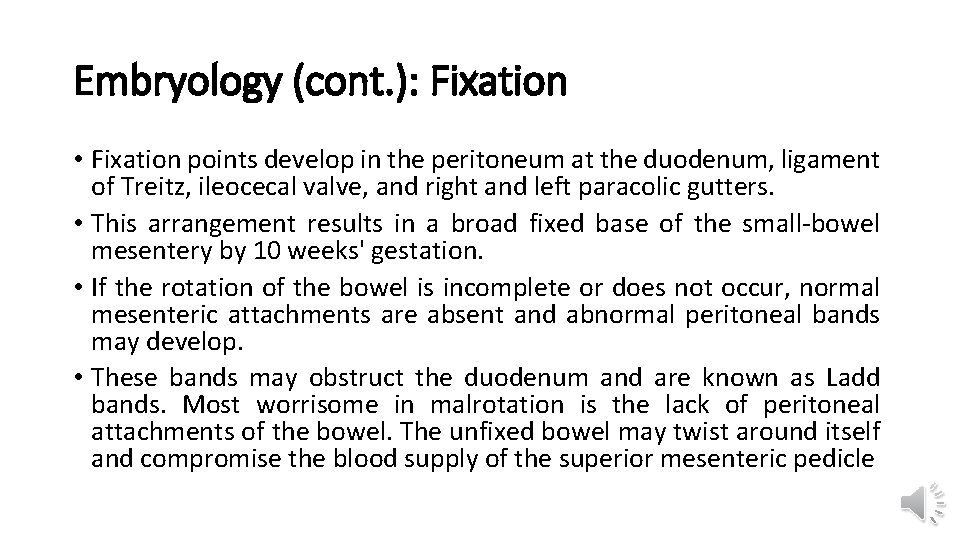

Embryology (cont. ): Fixation • Fixation points develop in the peritoneum at the duodenum, ligament of Treitz, ileocecal valve, and right and left paracolic gutters. • This arrangement results in a broad fixed base of the small-bowel mesentery by 10 weeks' gestation. • If the rotation of the bowel is incomplete or does not occur, normal mesenteric attachments are absent and abnormal peritoneal bands may develop. • These bands may obstruct the duodenum and are known as Ladd bands. Most worrisome in malrotation is the lack of peritoneal attachments of the bowel. The unfixed bowel may twist around itself and compromise the blood supply of the superior mesenteric pedicle

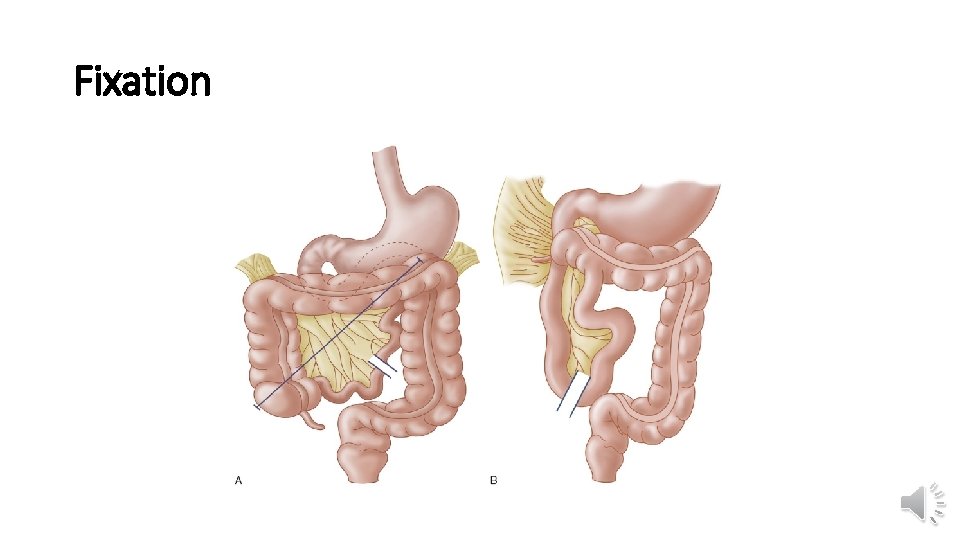

Fixation

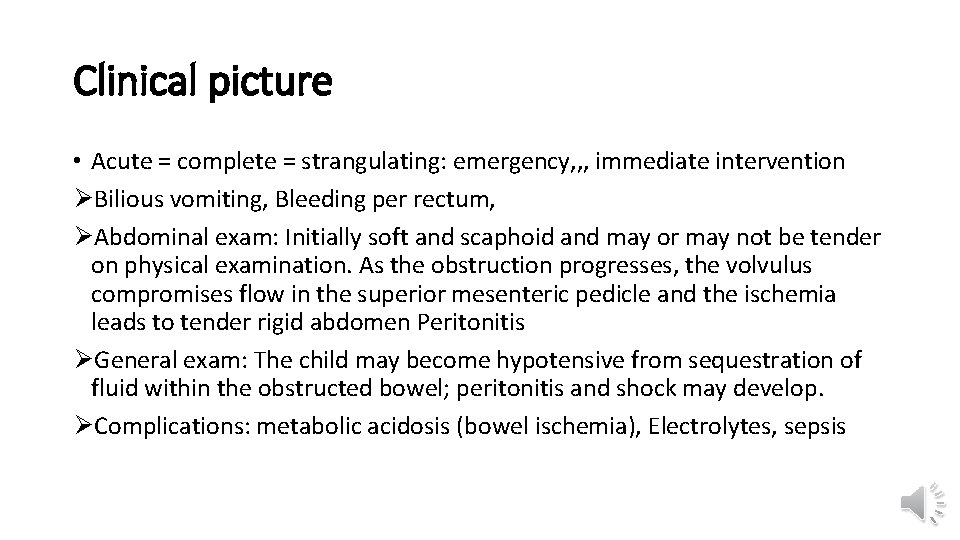

Clinical picture • Acute = complete = strangulating: emergency, , , immediate intervention ØBilious vomiting, Bleeding per rectum, ØAbdominal exam: Initially soft and scaphoid and may or may not be tender on physical examination. As the obstruction progresses, the volvulus compromises flow in the superior mesenteric pedicle and the ischemia leads to tender rigid abdomen Peritonitis ØGeneral exam: The child may become hypotensive from sequestration of fluid within the obstructed bowel; peritonitis and shock may develop. ØComplications: metabolic acidosis (bowel ischemia), Electrolytes, sepsis

C/P: (cont. ) • Chronic = incomplete = Non-strangulating: indolent course ØRecurrent bilious vomiting, constipation, intestinal dysmotility, abdominal pain(bands) ØAbdominal exam : normal ØGeneral exam: normal

Ix • Lab • Radiology 1. PXR 2. Contrast study: cork screw 3. US: Normally, the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) lies to the left of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV). An SMA that lies to the right or anterior to the SMV suggests malrotation 4. Contrast enema may demonstrate the abnormal position of the cecum but is no longer considered the best study to establish the diagnosis of malrotation

Abnormal gas distribution

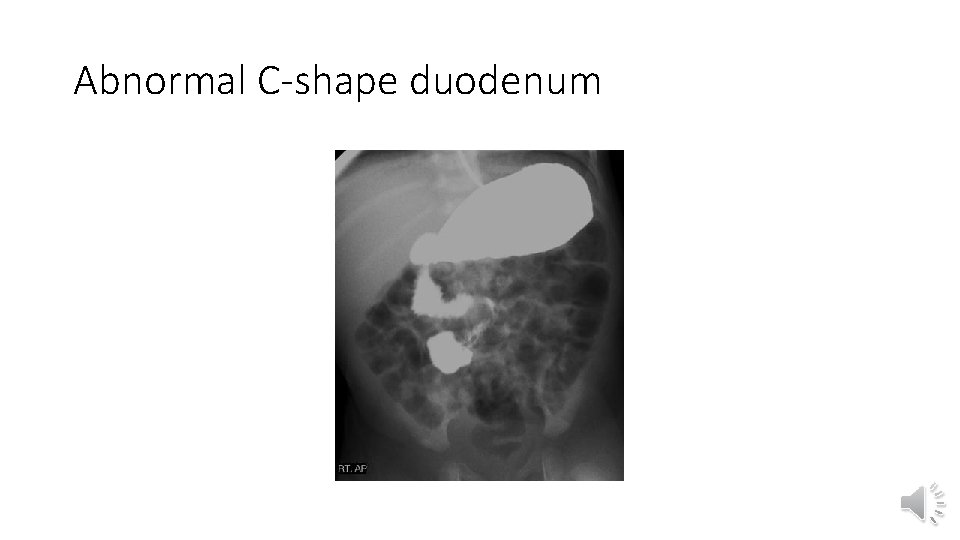

Abnormal C-shape duodenum

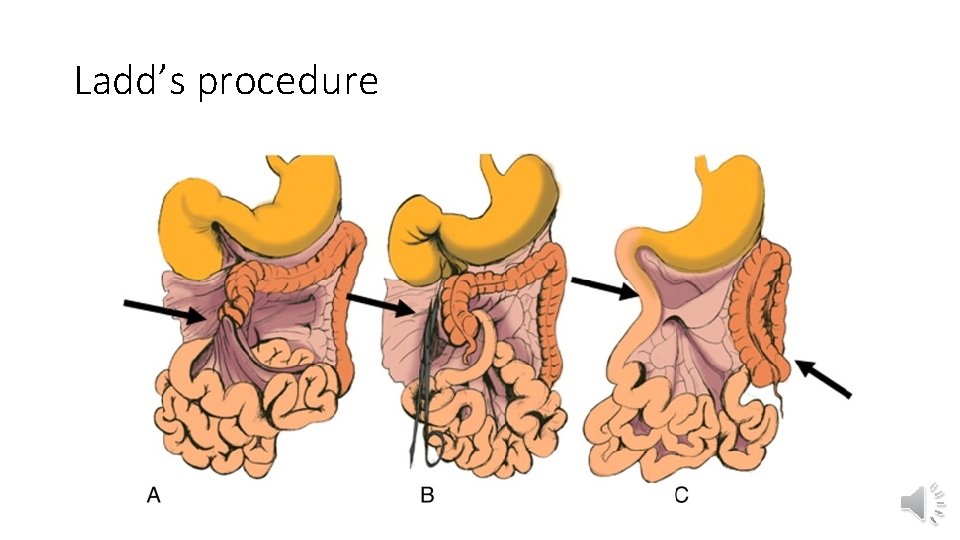

Treatment • Surgical treatment for malrotation is the Ladd procedure. A Ladd procedure includes evisceration of the midgut and immediate counterclockwise derotation of the gut to release the volvulus and reestablish flow of blood to the bowel. Obstructing Ladd bands from the colon to the duodenum are released. • The position of the mesentery does not allow the bowel to be placed in a normal position within the abdomen; therefore, the bowel is returned to the abdomen in a manner that spreads out the mesentery as much as possible. The duodenum and small bowel are placed on the right side of the abdomen, and the colon is placed on the left, with the cecum in the left lower quadrant. Because the ileocecal valve now is on the left side of the abdomen, the appendix is removed. Development of new postoperative adhesions may secure the bowel in this new configuration to avoid recurrent volvulus.

Ladd’s procedure

Prognosis • Malrotation with midgut volvulus is a true surgical emergency in the newborn. Delay in operation may result in catastrophic loss of a large portion of the small bowel. In patients with severe midgut volvulus, the entire midgut is necrotic and the child cannot survive. • Morbidity and mortality from malrotation and volvulus are directly related to the extent of bowel necrosis. The mortality rate may be as high as 65% if more than 75% of the small bowel is necrotic at the time of laparotomy. Survivors may develop short bowel syndrome, with its associated complications of malabsorption and malnutrition. The Ladd procedure does not address the intestinal dysmotility associated with malrotation but rather prevents the risk of midgut volvulus. Thus, patients with constipation and motility problems from malrotation may note improvement in their symptoms following the Ladd procedur

Jejuno-ileal atresia Ahmed Elrouby, MD

Incidence • Atresia of the jejunum or ileum is more common than duodenal atresia, • It occurs in 1500 births. • Small-bowel obstruction from jejunoileal atresia may also lead to polyhydramnios and premature delivery is observed in one third of patients with intestinal atresia

Pathogenesis • In contrast to duodenal atresia, jejunoileal atresia is widely considered to be a condition acquired during development rather than a preprogrammed anomaly due to vascular accident • The extent of atresia and the appearance of the atretic intestinal segment vary according to the timing and degree of the disruption of the mesenteric blood supply. Atresias may be focal or multiple throughout the small bowel. Interruption of the main superior mesenteric blood supply can result in atresia of most of the jejunum and ileum. • Other abdominal conditions, such as gastroschisis or intrauterine intussusception, may be associated with intestinal atresia, presumably from kinking, stretching, or otherwise disrupting the blood supply to the fetal bowel. Chromosomal anomalies are rare (<1%) in children with jejunoileal atres

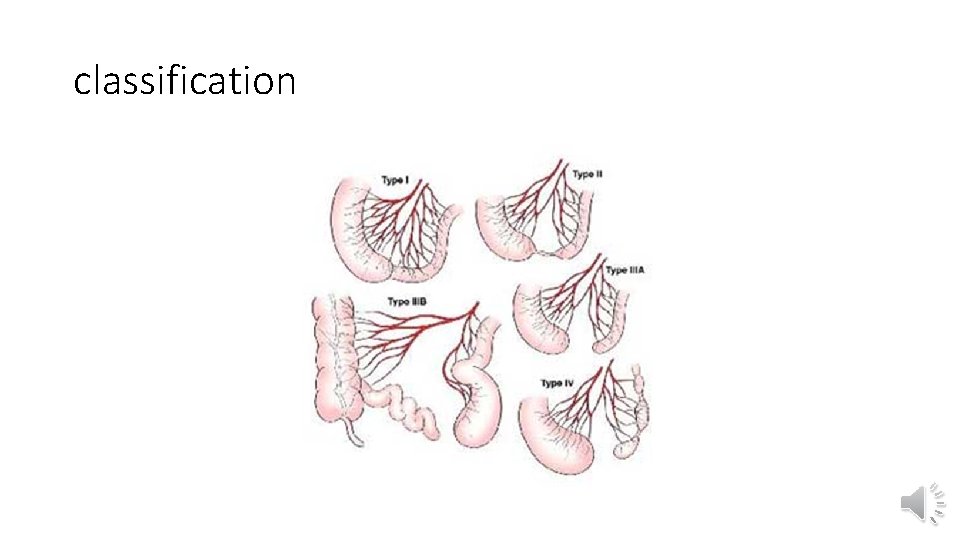

Classification • Types (Classification)---see fig. Type I: intraluminal diaphragm (membrane). Type II: 2 bowel ends connected by fibrous atretic cord. Type III: (a) 2 bowel ends completely separated with a mesenteric defect. • (b) apple peel (christmas tree) anomaly. Type IV: multiple defects

classification

C/P • Bilious vomiting • Distension • Non passage of meconium

c/p • Infants with jejunoileal atresia may present with distention and vomiting. .

Ix • Lab • Radiology ØPXR: Thumb-sized loops of bowel with air-fluid levels can be observed on plain radiography. As many as 12% of newborns with jejunoileal atresia may have intra-abdominal calcifications observed on plain radiography. These calcifications are consistent with meconium peritonitis, resulting from necrosis and perforation of a devascularized loop of bowel ØContrast enema: Some surgeons insist on a contrast enema to exclude colonic atresia, while others examine the colon intraoperatively to ensure patency of the distal bowel

Treatment • Preoperative: Blood flow to the segments immediately proximal and distal to the atresia may be compromised. For this reason, preoperative nasogastric decompression is vital to limit distention of the intestine proximal to the atresia. A delay in diagnosis or operation may distend and compromise the poorly vascularized, dilated, often bulbous bowel. • Operative: Surgery for jejunoileal atresia involves resection and primary anastomosis of the atretic segments. Diverting ostomies are avoided if possible. As with surgery for duodenal atresia, tapering of the proximal dilated segment occasionally is necessary to limit the motility problems observed with dilated proximal bowel. If at all possible, the ileocecal valve is preserved. Long-term outcomes are generally excellent if sufficient bowel is present for absorption and growth

- Slides: 34