Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Six to Twelve Months Introduction

Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Six to Twelve Months

Introduction of Co-Presenters • Jennifer Mc. Allister, MD, IBCLC • Medical Director, West Chester Hospital Special Care Nursery, University of Cincinnati Newborn Nursery, NOWS/NAS Follow-up Clinic • Pediatrician with experience in newborn medicine for 10 years • Kate Meister, Ph. D • Assistant Professor, Behavioral Medicine and Clinical Psychology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center • Psychologist in NICU Follow-Up and NAS clinic. • Clinical specialty training in integrative behavioral health, early childhood psychology and developmental assessment, behavioral sleep medicine • Liz Rick, MOT, OTR/L • Registered Occupational Therapist with 10 years of experience • Employed at CCHMC for 7 years • A part of the NOWS/NAS Clinic since its start 5 years ago

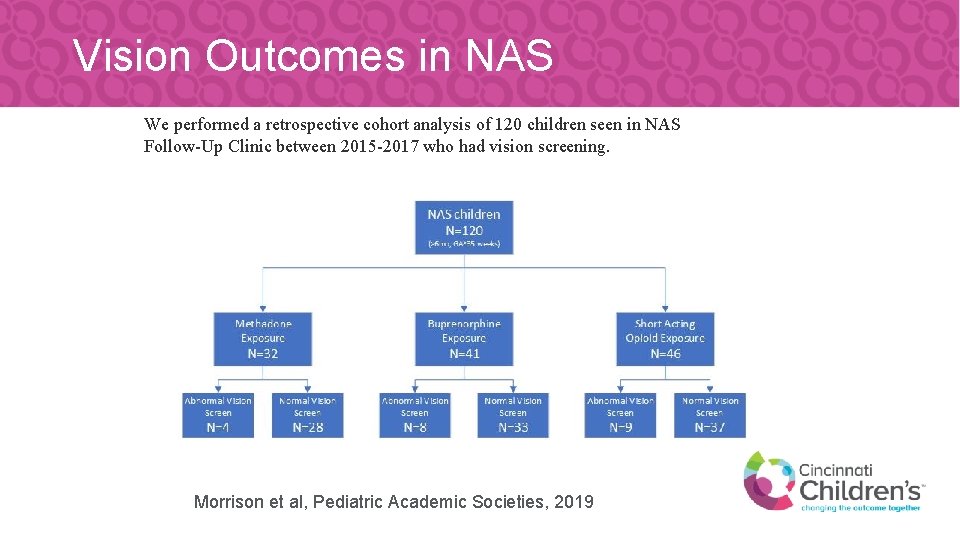

Vision Outcomes in NAS We performed a retrospective cohort analysis of 120 children seen in NAS Follow-Up Clinic between 2015 -2017 who had vision screening. Morrison et al, Pediatric Academic Societies, 2019

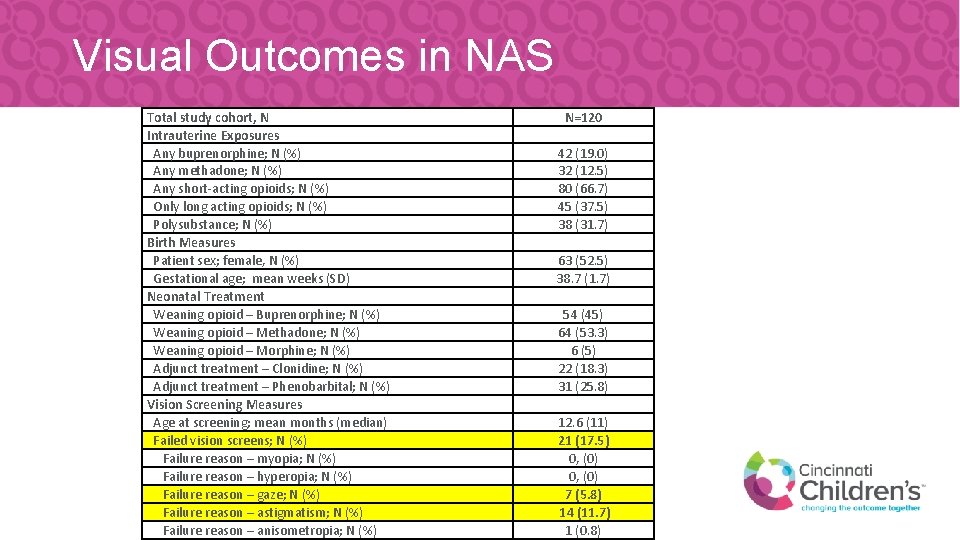

Visual Outcomes in NAS Total study cohort, N Intrauterine Exposures Any buprenorphine; N (%) Any methadone; N (%) Any short-acting opioids; N (%) Only long acting opioids; N (%) Polysubstance; N (%) Birth Measures Patient sex; female, N (%) Gestational age; mean weeks (SD) Neonatal Treatment Weaning opioid – Buprenorphine; N (%) Weaning opioid – Methadone; N (%) Weaning opioid – Morphine; N (%) Adjunct treatment – Clonidine; N (%) Adjunct treatment – Phenobarbital; N (%) Vision Screening Measures Age at screening; mean months (median) Failed vision screens; N (%) Failure reason – myopia; N (%) Failure reason – hyperopia; N (%) Failure reason – gaze; N (%) Failure reason – astigmatism; N (%) Failure reason – anisometropia; N (%) N=120 42 (19. 0) 32 (12. 5) 80 (66. 7) 45 (37. 5) 38 (31. 7) 63 (52. 5) 38. 7 (1. 7) 54 (45) 64 (53. 3) 6 (5) 22 (18. 3) 31 (25. 8) 12. 6 (11) 21 (17. 5) 0, (0) 7 (5. 8) 14 (11. 7) 1 (0. 8)

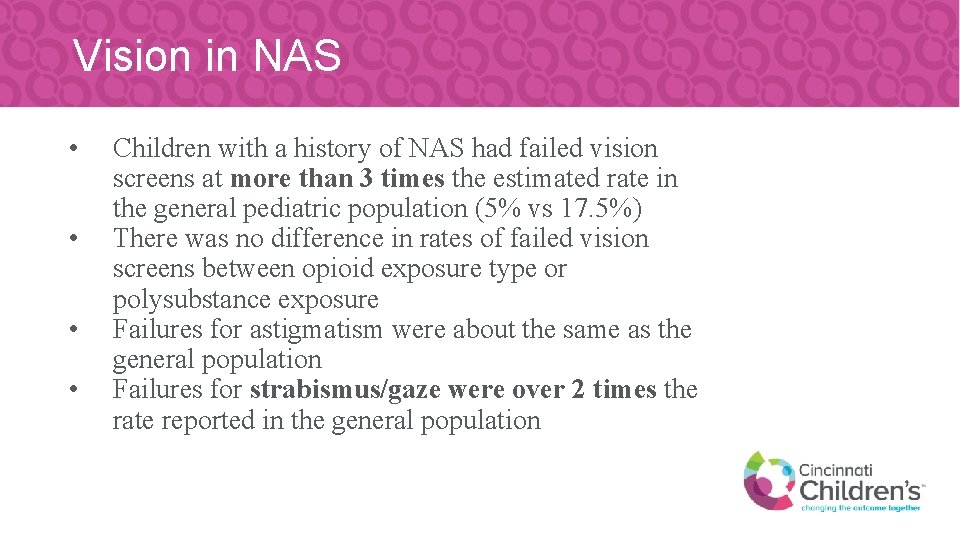

Vision in NAS • • Children with a history of NAS had failed vision screens at more than 3 times the estimated rate in the general pediatric population (5% vs 17. 5%) There was no difference in rates of failed vision screens between opioid exposure type or polysubstance exposure Failures for astigmatism were about the same as the general population Failures for strabismus/gaze were over 2 times the rate reported in the general population

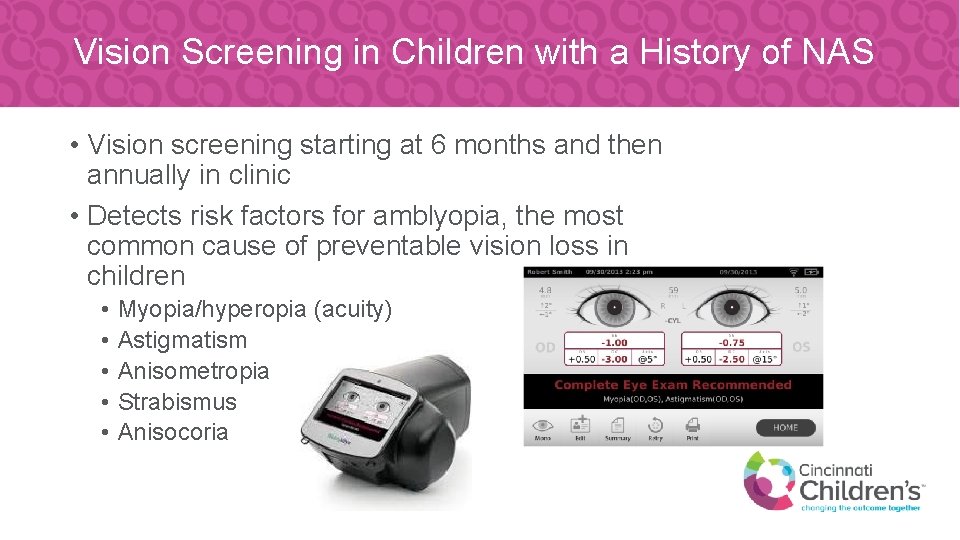

Vision Screening in Children with a History of NAS • Vision screening starting at 6 months and then annually in clinic • Detects risk factors for amblyopia, the most common cause of preventable vision loss in children • • • Myopia/hyperopia (acuity) Astigmatism Anisometropia Strabismus Anisocoria

Normal Visual Development • The ability to see 20/20, focusing ability (accommodation), eye muscle coordination (aiming or alignment) and stereopsis are all developed by 6 months of age in humans. By 9 months of age, the system is in place. • Maximum "critical period" in humans is from just after birth to 2 years of age • If amblyopia is not detected by the age of 7 -9, vision loss will become permanent

Normal Visual Development Five to eight months old: reaching, recognition and recall • At around five months old, a baby's depth perception has developed. • They are seeing the world in 3 D more completely, and this is evident as they get better at reaching for objects both near and far. • They also have good color vision at this point, though not quite as fully developed as an adult's. • At this stage, a baby may recognize their parent across a room and smile at them • They can see objects outside when looking through a window. • They might even remember what an object is even if they only see part of it. • Babies generally start crawling, and this further enhances their eye-hand coordination https: //www. aao. org/eye-health/tips-prevention/baby-vision-development-first-year

Normal Visual Development Nine to twelve months: Gripping, grasping and on the go • At about nine months old, babies can generally judge distance pretty well. • Usually by nine months, babies eyes are probably their final color, though it is not uncommon to see some slight changes later. • Babies can now judge distances fairly well and throw things with precision. • This is about when they start to pull themselves up to stand. • At around ten months old, babies can usually see and judge distance well enough to grasp something between their thumb and forefinger. • By twelve months old, most babies are crawling and trying to walk.

Visual Developmental Concerns • By three to four months old, an infant should be able to focus on objects and the eyes should be straight, with no turning (strabismus). • If you notice that a child's eyes are moving inward or outward, if he or she is not focusing on objects, and/or the eyes seem to be crossed, you should seek medical attention. (red flag) • It might only be noticed when a child is tired or looking at something very closely • If abnormal, needs eye examination by a physician • Infants who have significant delays in tracking moving objects (after 3 months old) or eyes beating back and forth when tracking objects (nystagmus)

How to Promote Visual Development Five to eight months • Hang a mobile, crib gym or various objects across the crib for the baby to grab, pull and kick. • Give the baby plenty of time to play and explore on the floor. • Provide plastic or wooden blocks that can be held in the hands. • Play patty cake and other games, moving the baby's hands through the motions while saying the words aloud.

How to Promote Visual Development Nine to twelve months • Play hide and seek games with toys or your face to help the baby develop visual memory. • Name objects when talking to encourage the baby's word association and vocabulary development skills. • Encourage crawling and creeping.

Social Emotional Development and Sleep 6 to 12 months

Social Emotional Development • Direct relationship of prenatal exposure on later infant and toddler development is unclear • Generally higher risk for behavioral and/emotional concerns • comorbid substance exposure (e. g. , alcohol, tobacco, other illicit drugs) • Environmental – low SES, caregiver mental health • Other medical risk factors - poor prenatal care, prematurity, drug treatment for symptoms at birth

Social Emotional Development Major Milestones 6 months • Can discriminate familiar faces vs. strangers • Likes to play with others (especially parents) • Responds to others’ emotions 9 months • Has favorite toys • May develop stranger anxiety/cling to caregivers 12 months • Has favorites things/people • Shows fear in certain situations • Makes sounds/actions to get attention • Plays interactive games (e. g. , peek-a-boo)

Social Emotional Development Attachment • Moving from Indiscriminate to Discriminate Attachment • Infants exposed prenatally are at higher risk for insecure and disorganized attachment patterns • May not experience stranger anxiety • May be overly clingy to caregivers • Take longer to recover when reunited with caregiver • Multiple placements may disrupt attachment with caregivers

Social Emotional Development Potential Difficulties • Visit with noncustodial parent(s): changes in behavior, increased fussiness, more clingy, disruptions in sleep • Stranger anxiety/separation anxiety • Managing visits • Expect period of adjustment prior to and after visits • Keep routines as consistent as possible • If possible – schedule visits around sleep and eating schedules • Schedule “recovery time” – play time with caregiver, calming activities

Social Emotional Development • Take away – although many factors will influence long term social, emotional, and behavioral development, consistent and predictable caregiving as well as establishment of solid daily routines can help mitigate risks for later behavior and emotional concerns

Sleep Milestones 6 to 9 months • Need 11 to 15 hours of sleep in 24 hour period • Most infants can “physiologically” sleep through night • 25 -50% of infants still wake up (and need help to fall asleep) • Signalers vs. self-soothers • Naps • May be sporadic nappers or consolidated to 2 -3 longer naps per day

Sleep Milestones 9 to 12 months • • 11 to 13 hours in 24 hour period Should continue to decrease Naps move toward more consolidation Frequent night waking– waking every 1 -2 hours

Common Sleep Challenges • Sleep regression • Around 6 and 9 months • Usually tied to development milestones or disruptions in routine • Sleep associations • Has only ever fallen asleep with…. caregiver present, being rocked, getting bottle, etc. • May be more likely to develop with NAS population because needed more external soothing in first couple of months • Safe sleep • Can no longer swaddle – other 5 S’s

Sleep Strategies • Start with consistent nap and bedtime routines • Continue to use 5 S’s (other than swaddling), white noise machine, dark room • Gradually fade sleep associations • Avoid having child fall asleep in your arms or while being rocked. • Make it a priority to have child in bed before he falls asleep. • Focus on bedtime at first or naptime, with the goal to address night wakings after child has learned to fall asleep on their own at bedtime. • Extinction • Checking Method • Caregiver presence

Extinction • Commonly known as "crying it out" • Involves putting child to bed and leaving the room and not returning unless you have concerns about physical health or safety. • Usually the fastest method to change sleep • Can be very difficult on caregivers

Checking Method • Once child has been put to bed say goodnight and leave the room • If child cries out and is still crying after a few minutes, return to the room and provide brief reassurance with words or light physical touch (placing hand on back or belly). • Do not pick up child turn on the lights, or respond to requests. Do not stay in the room longer than one or two minutes. • Repeat this process, extending the time that you give child to fall asleep independently (e. g. , 2 minutes; then 5 minutes; then 10 minutes; then 15 minutes

Caregiver Presence • Caregiver stays in the room after bedtime but eliminates all interactions (verbal; physical touch; eye contact). • Presence may be reassuring but you are not actively involved in assisting with child’s sleep onset thus leaving the room once child is asleep • Usually the slowest strategy but may be more acceptable for caregiver and child

Sleep Strategy Considerations Choosing a strategy • Assessing sleep environment • Lack of private sleep area • Crib vs. pack n play vs. co-sleeping • Caregiver readiness • Caregiver guilt • Caregiver fears/worries • Other factors – growth concerns, medical concerns • Take away – all of these strategies can be successful but need to be a good fit for caregiver and child

Sleep Resources • Pediatric Sleep Council • Great resource for therapists and caregivers • https: //www. babysleep. com/ • Books • Helping Your Child with Sleep Problems • by Michael Gradisar, Ph. D. • Sleeping Through the Night, Revised Edition: How Infants, Toddlers, and Their Parents Can Get a Good Night’s Sleep • by Jodi Mindell. Ph. D. • Sleeping Like a Baby : A Sensitive and Sensible Approach to Solving Your Child’s Sleep Problems • by Avi Sadeh

Gross Motor Milestones 6 -8 months • • • Rolling supine to prone Sitting independently Scooting forward Grasping both feet in supine Weight shifts and reaches for a toy in prone 9 -11 months • Creeps 5 feet (quadruped) • Maintains balance while sitting and manipulating toy • Pulls to standing

Gross Motor Red Flags • Not yet sitting independently by 9 months of age • Rocketing backwards in sitting • Unable to bear weight through plantar surface of both feet • Not taking weight OR • Unable to obtain a flat footed posture • Stiffness in the legs • Assess environment. Are they spending a lot of time in standing devices?

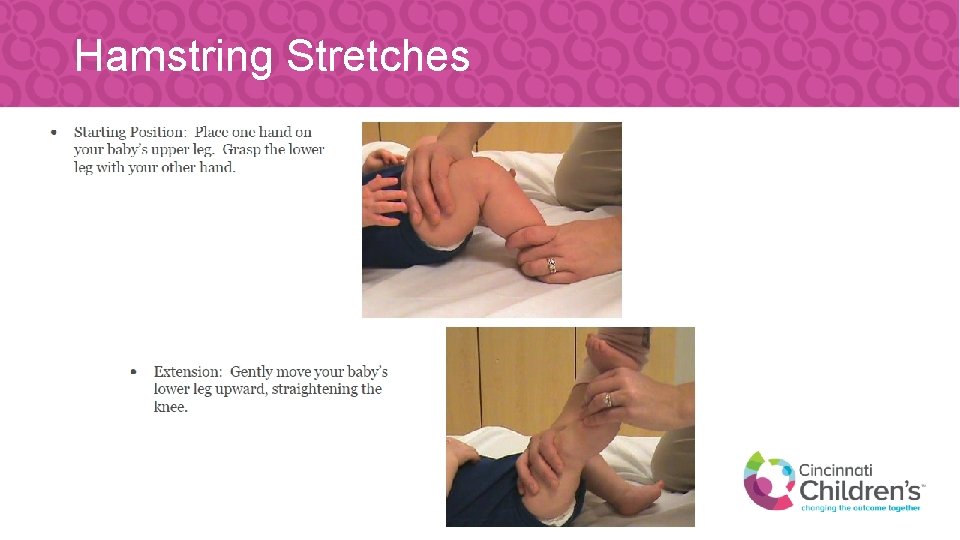

Hamstring Stretches

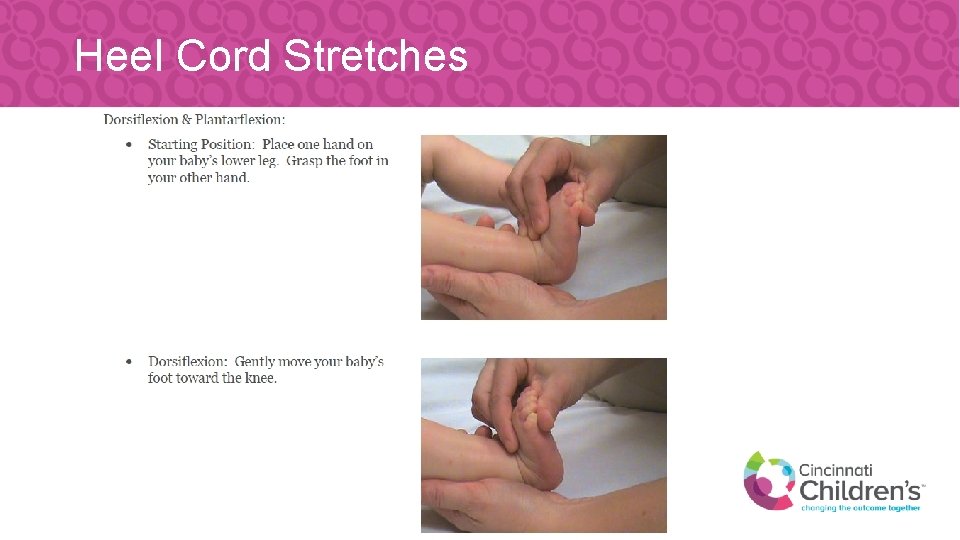

Heel Cord Stretches

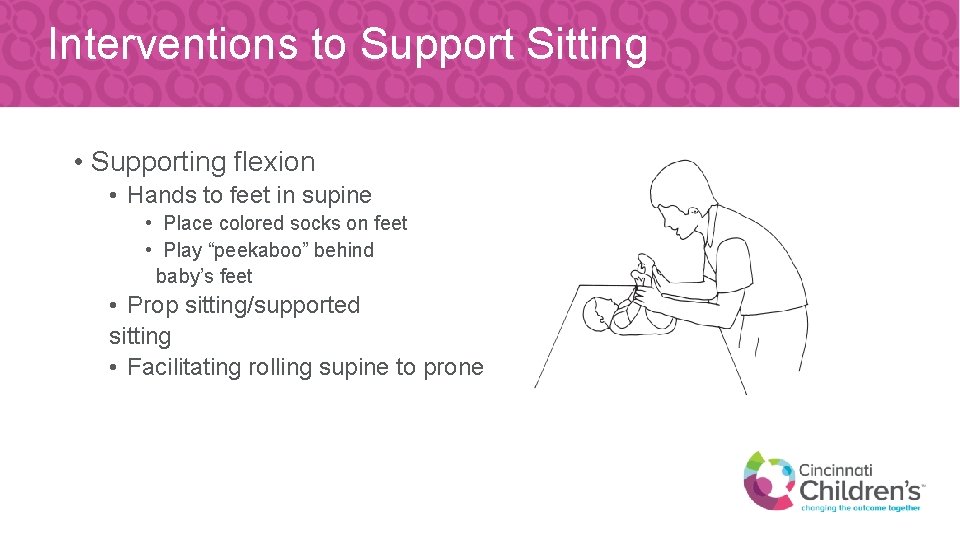

Interventions to Support Sitting • Supporting flexion • Hands to feet in supine • Place colored socks on feet • Play “peekaboo” behind baby’s feet • Prop sitting/supported sitting • Facilitating rolling supine to prone

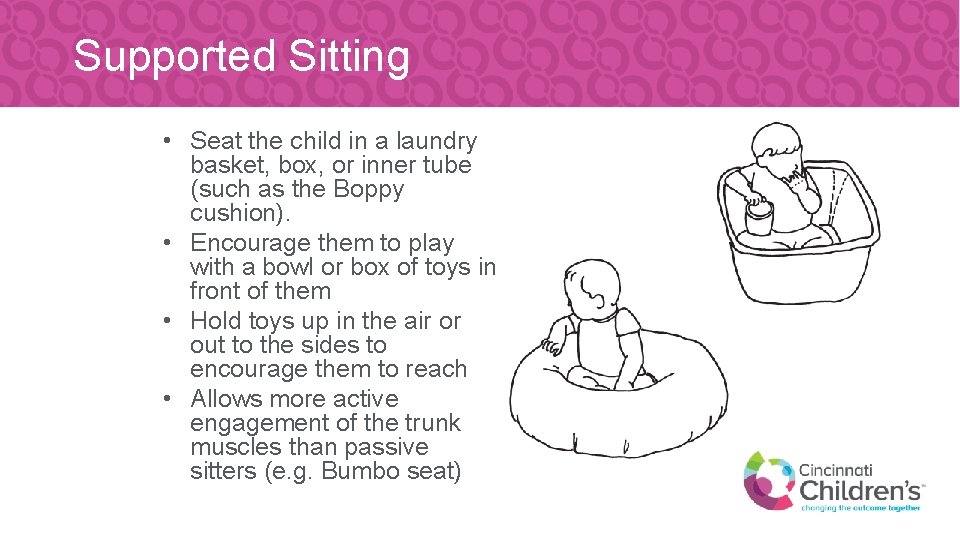

Supported Sitting • Seat the child in a laundry basket, box, or inner tube (such as the Boppy cushion). • Encourage them to play with a bowl or box of toys in front of them • Hold toys up in the air or out to the sides to encourage them to reach • Allows more active engagement of the trunk muscles than passive sitters (e. g. Bumbo seat)

Prop Sitting • Begin by placing your child in a seated position with their knees pointed out and their heels together. • Place toys in front of your child so they look forward. Try to keep your child in this seated position.

Fine Motor Milestones 6 -8 months • • • Retains 2 objects at the same Transfers objects between hands Bangs toys against table Rakes small objects Uses radial digital grasp 9 -11 months • Claps hands • Bangs objects together at midline • Emergence of pincer grasp (tip of thumb and index finger)

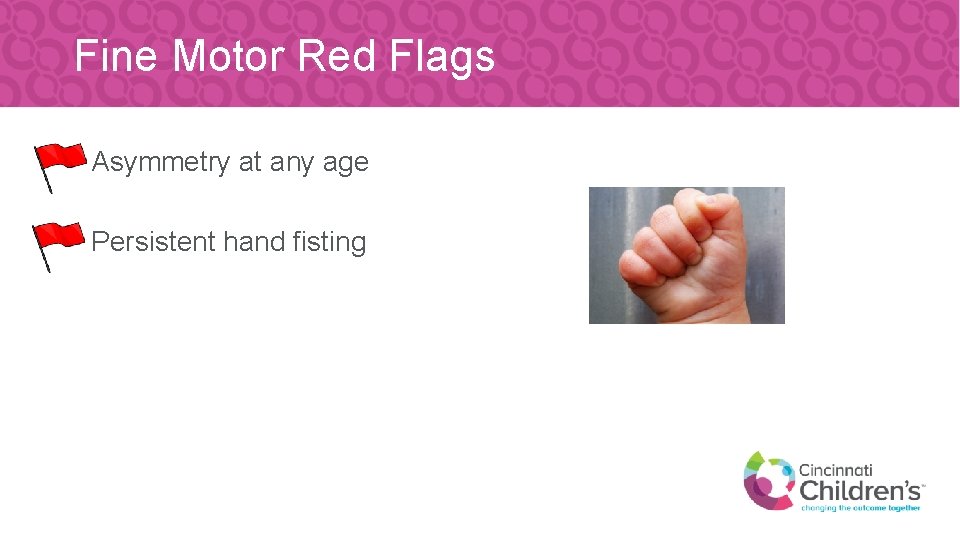

Fine Motor Red Flags • Asymmetry at any age • Persistent hand fisting

Interventions to Support Fine Motor Skills Encourage bilateral hand use • Offer large, lightweight objects that can be held with 2 hands (playground ball, books) • Offer objects that make noise when you tap them together (blocks, cymbals) • Assess posture while seated • Leaning can contribute to reaching easier with 1 hand

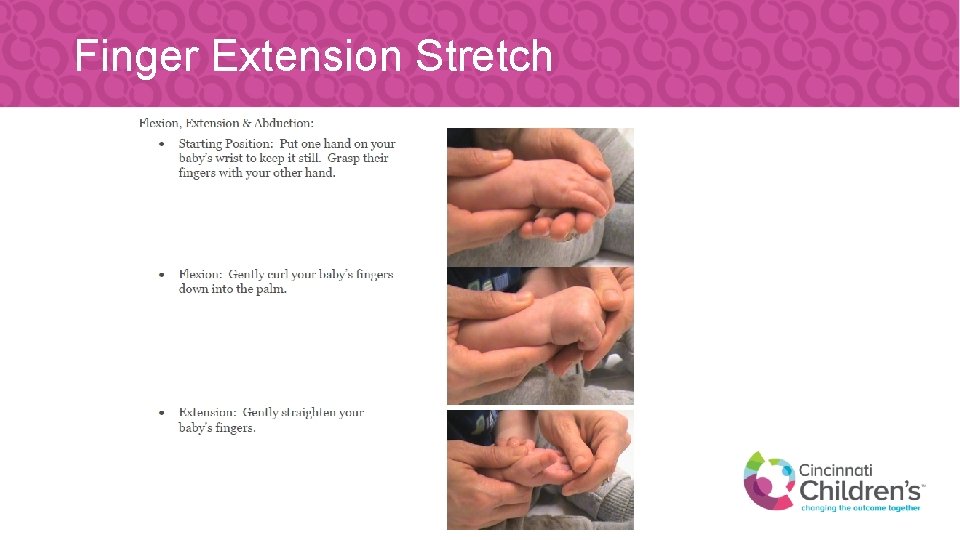

Finger Extension Stretch

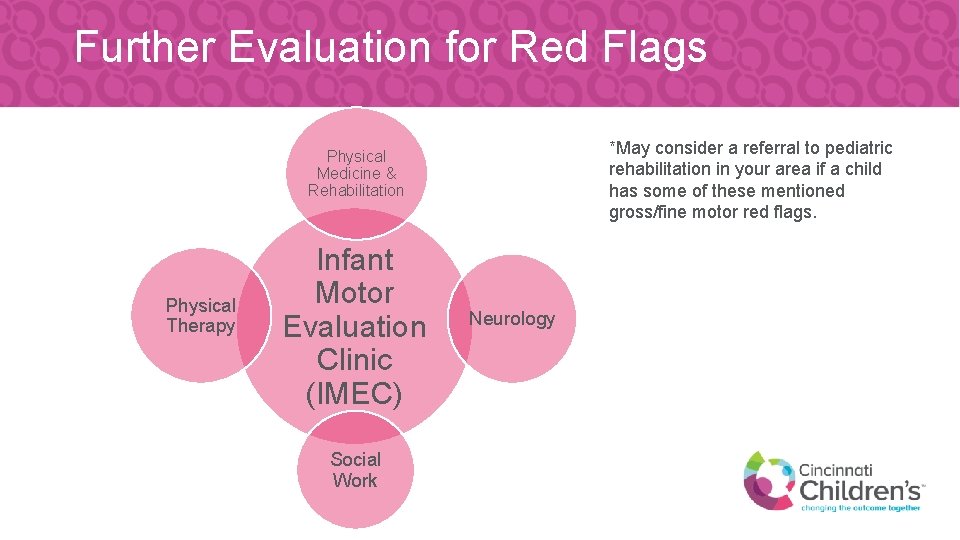

Further Evaluation for Red Flags *May consider a referral to pediatric rehabilitation in your area if a child has some of these mentioned gross/fine motor red flags. Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation Physical Therapy Infant Motor Evaluation Clinic (IMEC) Social Work Neurology

Beginning Solid Foods

Barriers Impacting Presentation of Puree/Solid Foods • Motor deficits such as poor postural control, limited manipulation of objects to initiate mouthing of toys • Medical procedures or conditions including: Digestive, cardiac, respiratory, neurologic • Sensory deficits that may impact including strong gag reflex, poor state regulation • May transition to purees OK, but struggle to transition to thicker/lumpier textures

Introducing Purees and Solids • Introduction of purees and solids provides an important opportunity to educate caregivers about feeding and how to read the child’s non-verbal communication • Stress is quality—not quantity—of feeding at this stage

Introducing Purees and Solids • Read the child’s cues for the presentation; they will guide the treatment session • Foods may not be the first strategy, as the child may need to work on overall desensitization • Do not ‘trick’ or present the spoon without the child’s permission; feeding should be a positive experience

Non-Nutritive Oral Exposure/Desensitization Tools • • Toothbrush Utensils Lots of Links Caregiver’s finger Baby’s hand NUK brush Small amount of puree on the tray Toys for sensory food exploration (e. g. , animal toys, little people in puree)

Presentation of Solids • Begin with small pieces of: • A soft, single texture solid (no outer shell or mixed textures) or • Meltable solid (one that will dissolve in the mouth) • Avoid mixing texture foods and some stage 3 baby foods • Presentation of the puree or sauce with a chunk is very difficult for a child to orally manage and will often prompt a gag

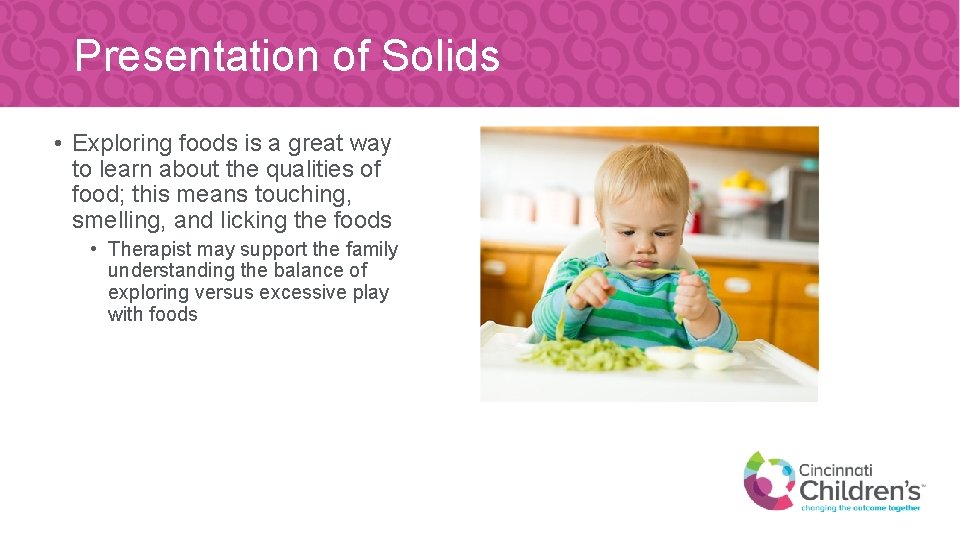

Presentation of Solids • Exploring foods is a great way to learn about the qualities of food; this means touching, smelling, and licking the foods • Therapist may support the family understanding the balance of exploring versus excessive play with foods

Common Negative Responses • Continue to read the cues of the child; when they are turning from or pushing away the foods presented, the experience may be too much for them to handle

Common Negative Responses Modify diet to support successful feeding: • • • smaller bite size change texture offer dips modify sensory properties of foods may encourage family to work on desensitization using non-nutritive items

Treatment Strategies to Support Transition to Solids • Spitting out foods does not mean dislike • Up until this point, movement with oral intake has been front to back movements (e. g. , bottle/breast, puree); due to this pattern, foods may be pushed OUT • Presentation of new foods may take 15 -20 times prior to acceptance of the foods • Allow child to engage in finger feeding, if able to support placement of food in their mouth

Presenter Contact Information • Jennifer. Mc. Allister@cchmc. org • Elizabeth. Rick@cchmc. org • Kate. Meister@cchmc. org

References • CDC’s Developmental Milestones - https: //www. cdc. gov/ncbddd/actearly/milestones/index. html • Logan, B. A. , Brown, M. S. , & Hayes, M. J. (2013). Neonatal abstinence syndrome: treatment and pediatric outcomes. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology, 56(1), 186– 192. https: //doi. org/10. 1097/GRF. 0 b 013 e 31827 feea 4 • Mindell JA & Owens JA (2003). A Clinical Guide to Pediatric Sleep: Diagnosis and Management of Sleep Problems. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. • Pediatric Sleep Council - https: //www. babysleep. com/ • Swanson, K. , Beckwith, L. , & Howard, J. 2000. Intrusive caregiving and quality of attachment in prenatally drug-exposed toddlers and their primary caregivers. Attachment & Human Development, 2(2): 130 -148.

- Slides: 51