Naming Names are used to uniquely identify resourcesservices

![Home-Based Approach The principle of Mobile IP [Perkins 97] 30 Home-Based Approach The principle of Mobile IP [Perkins 97] 30](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/58bca5b22e1dec7b368ef676dd453acf/image-30.jpg)

- Slides: 47

Naming • Names are used to uniquely identify resources/services. • Name resolution: process to determine the actual entity that a name refers to. • In distributed settings, the naming system is often provided by a number of sites. 1

Names and Addresses • Name is a string of bytes used to refer to an entity. • Examples: – Processes, mailboxes, printers, disk, files, web-pages, messages, NICs etc. • Access Point = Address of the entity to be addressed. • Nice attribute: name should be independent of the address (location independent). • Addresses: 32/64 bit-string (48 bits for Ethernet addresses vs. User-friendly-names (in Unix each file can have upto 255 bytes name). 2

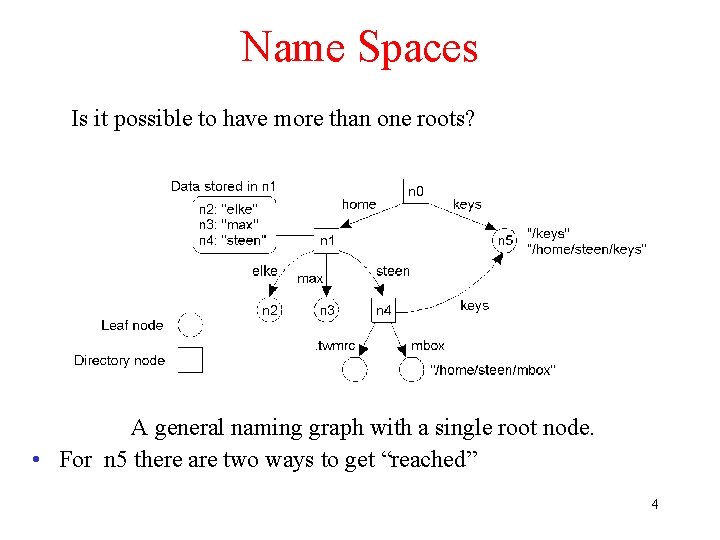

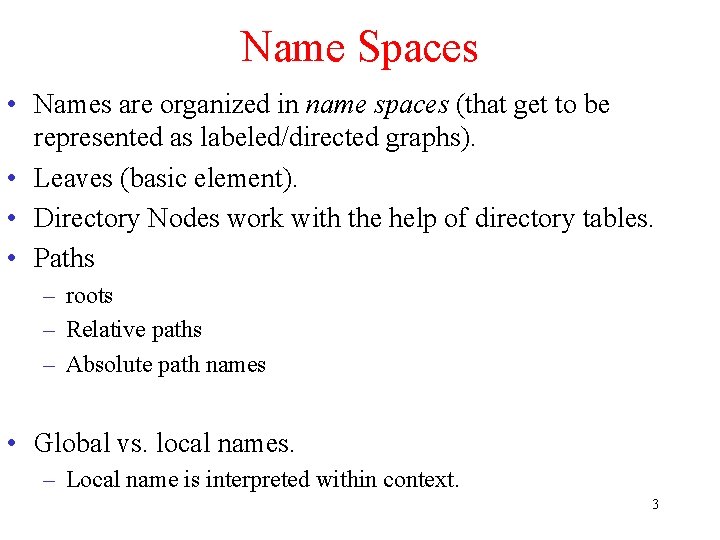

Name Spaces • Names are organized in name spaces (that get to be represented as labeled/directed graphs). • Leaves (basic element). • Directory Nodes work with the help of directory tables. • Paths – roots – Relative paths – Absolute path names • Global vs. local names. – Local name is interpreted within context. 3

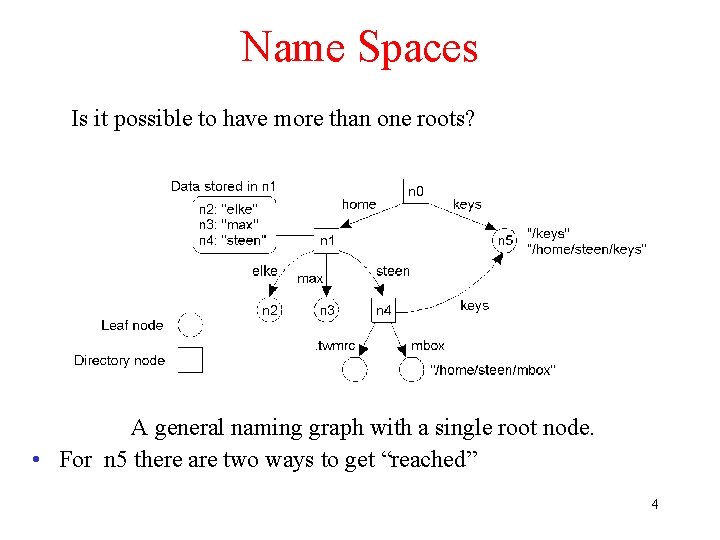

Name Spaces Is it possible to have more than one roots? A general naming graph with a single root node. • For n 5 there are two ways to get “reached” 4

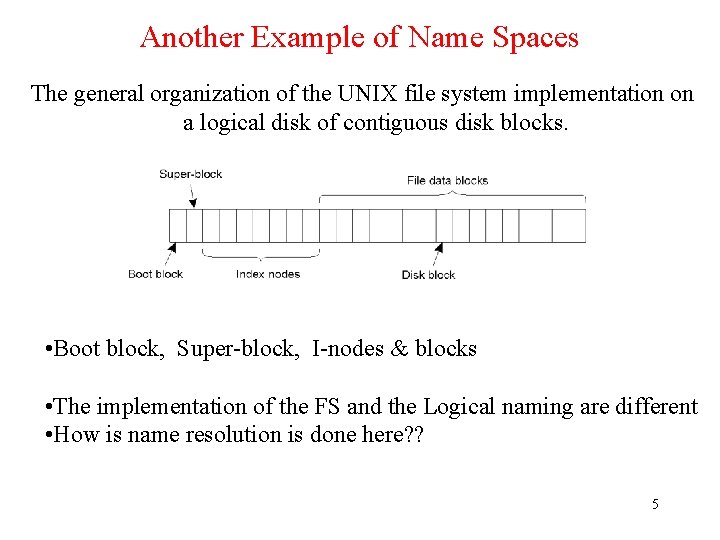

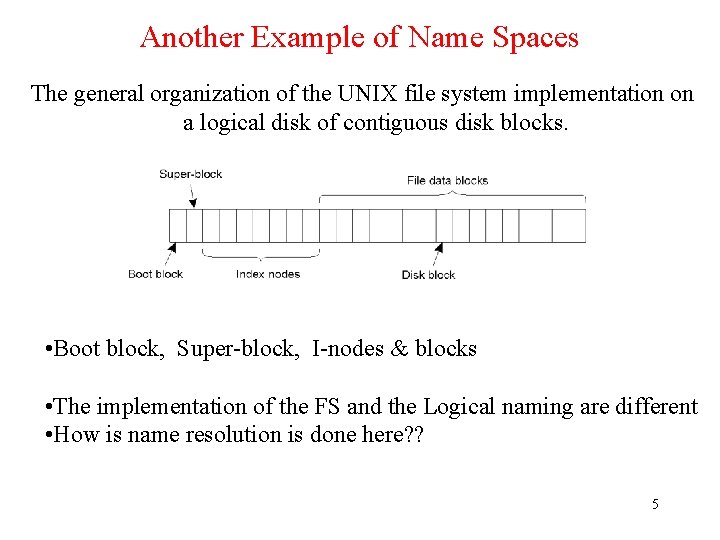

Another Example of Name Spaces The general organization of the UNIX file system implementation on a logical disk of contiguous disk blocks. • Boot block, Super-block, I-nodes & blocks • The implementation of the FS and the Logical naming are different • How is name resolution is done here? ? 5

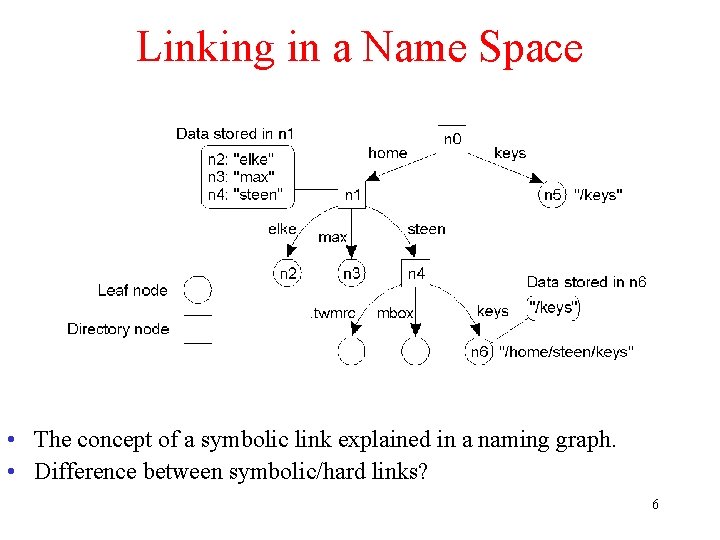

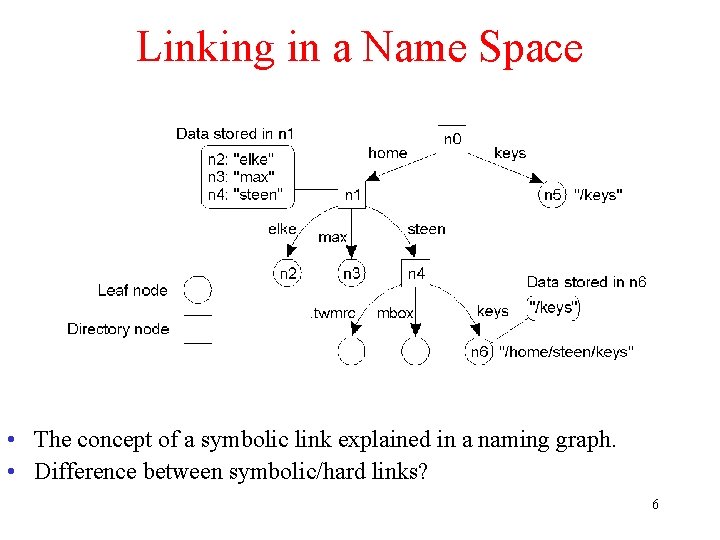

Linking in a Name Space • The concept of a symbolic link explained in a naming graph. • Difference between symbolic/hard links? 6

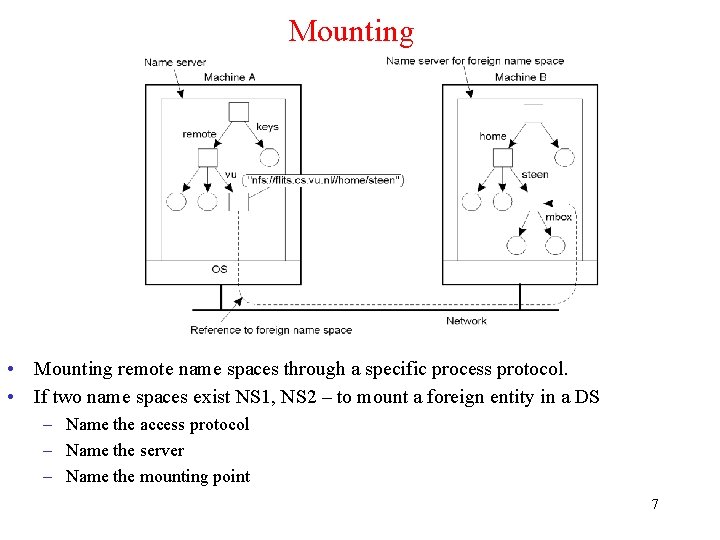

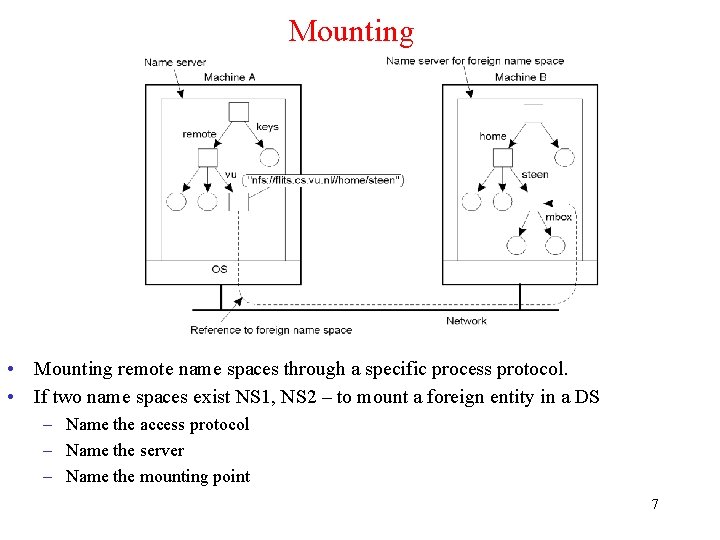

Mounting • Mounting remote name spaces through a specific process protocol. • If two name spaces exist NS 1, NS 2 – to mount a foreign entity in a DS – Name the access protocol – Name the server – Name the mounting point 7

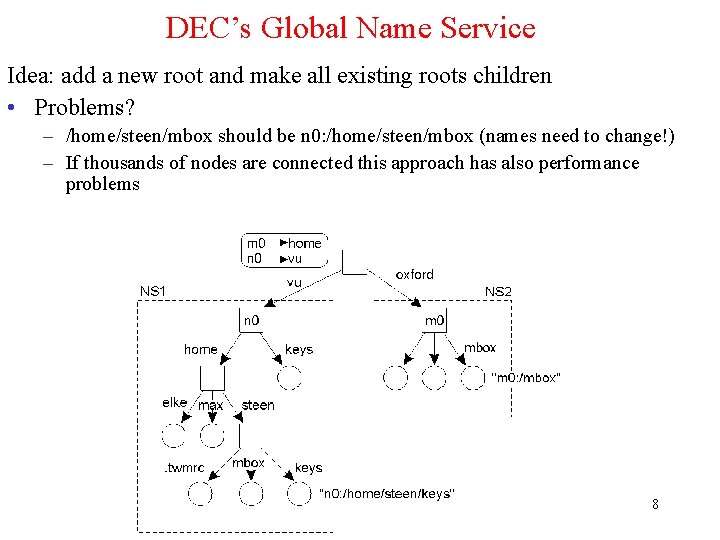

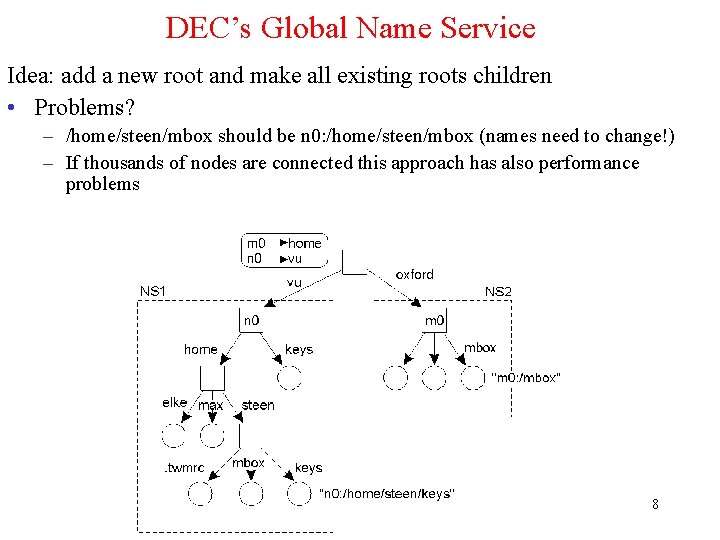

DEC’s Global Name Service Idea: add a new root and make all existing roots children • Problems? – /home/steen/mbox should be n 0: /home/steen/mbox (names need to change!) – If thousands of nodes are connected this approach has also performance problems 8

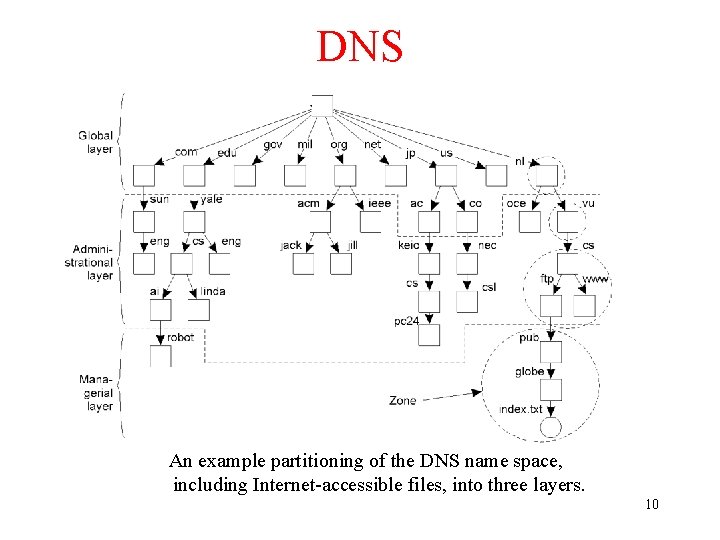

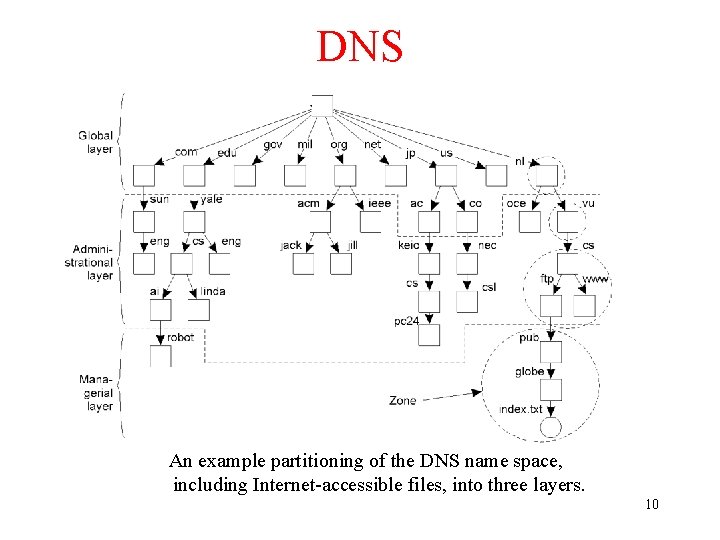

Organizing Name Spaces for DSs • To effectively implement a Large-Scale naming System the name space has to be partitioned into a number of layers: – Global Leyer (high level nodes) – Administrative Leyer (manages names within a single organization) – Managerial Leyer (name spaces that may often change) – DNS – Domain Name Service is such an example. 9

DNS An example partitioning of the DNS name space, including Internet-accessible files, into three layers. 10

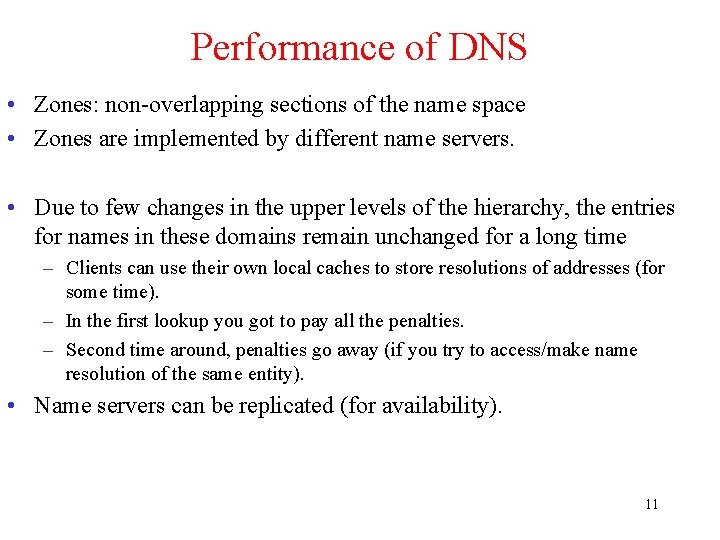

Performance of DNS • Zones: non-overlapping sections of the name space • Zones are implemented by different name servers. • Due to few changes in the upper levels of the hierarchy, the entries for names in these domains remain unchanged for a long time – Clients can use their own local caches to store resolutions of addresses (for some time). – In the first lookup you got to pay all the penalties. – Second time around, penalties go away (if you try to access/make name resolution of the same entity). • Name servers can be replicated (for availability). 11

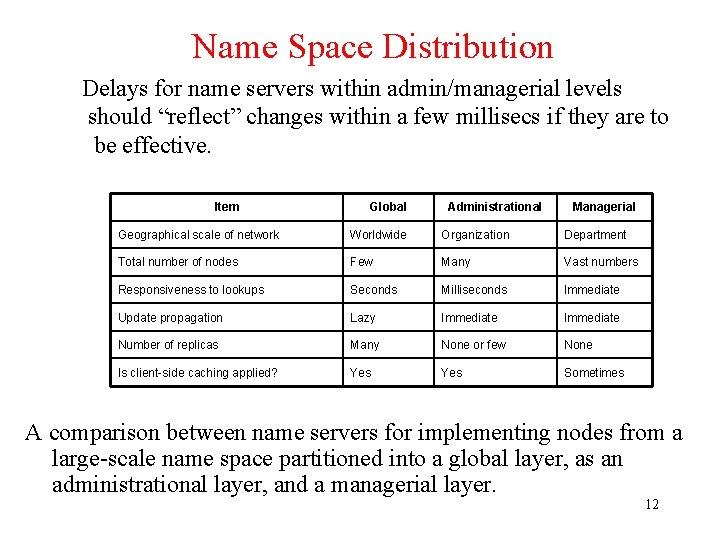

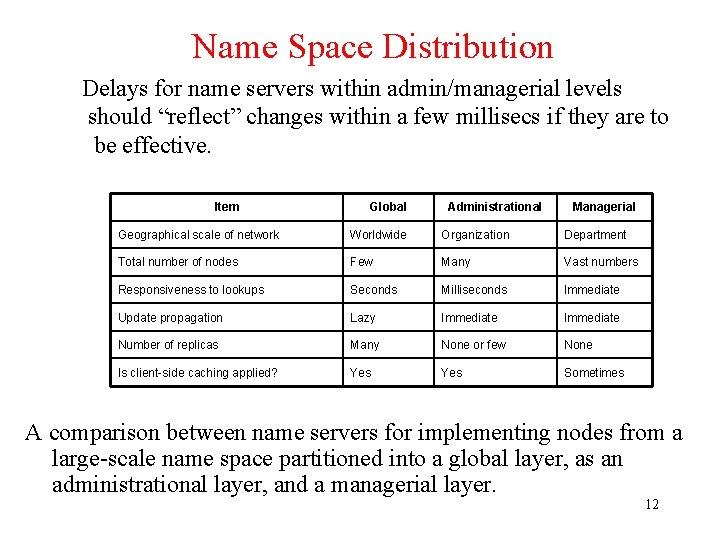

Name Space Distribution Delays for name servers within admin/managerial levels should “reflect” changes within a few millisecs if they are to be effective. Item Global Administrational Managerial Geographical scale of network Worldwide Organization Department Total number of nodes Few Many Vast numbers Responsiveness to lookups Seconds Milliseconds Immediate Update propagation Lazy Immediate Number of replicas Many None or few None Is client-side caching applied? Yes Sometimes A comparison between name servers for implementing nodes from a large-scale name space partitioned into a global layer, as an administrational layer, and a managerial layer. 12

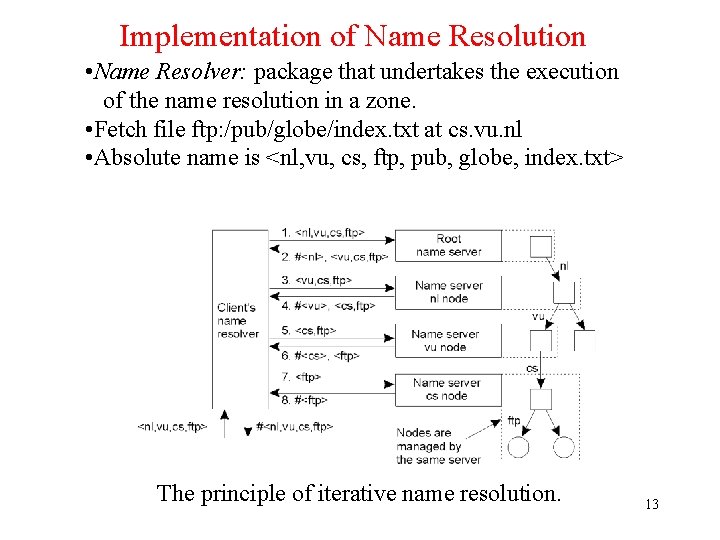

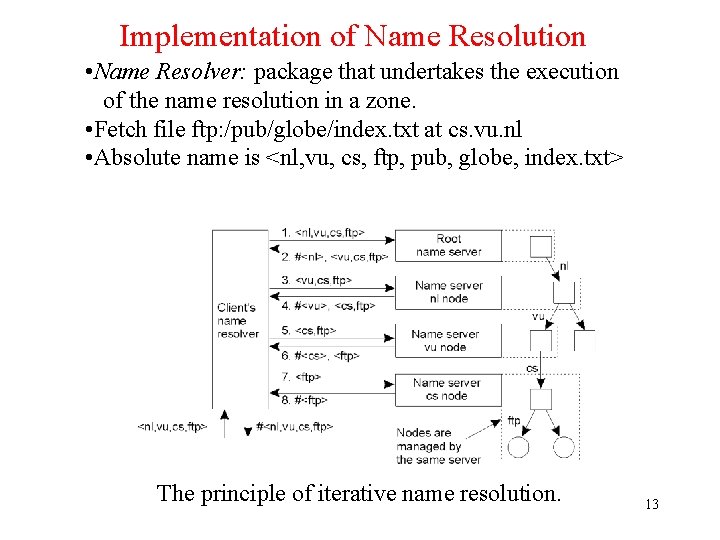

Implementation of Name Resolution • Name Resolver: package that undertakes the execution of the name resolution in a zone. • Fetch file ftp: /pub/globe/index. txt at cs. vu. nl • Absolute name is <nl, vu, cs, ftp, pub, globe, index. txt> The principle of iterative name resolution. 13

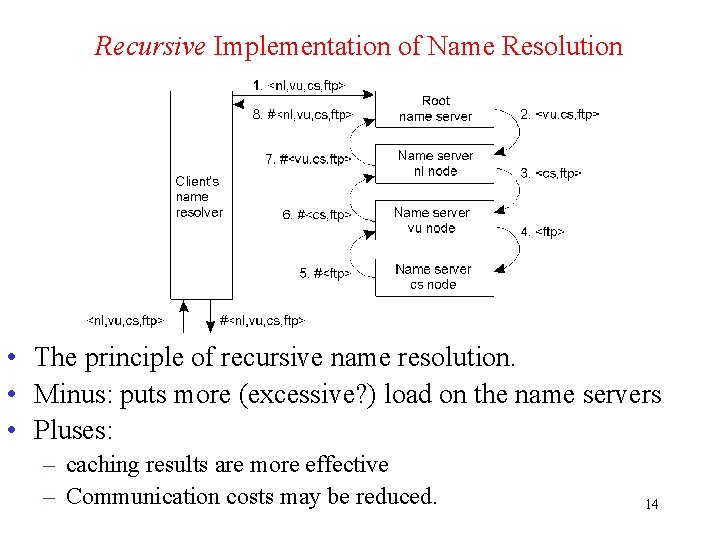

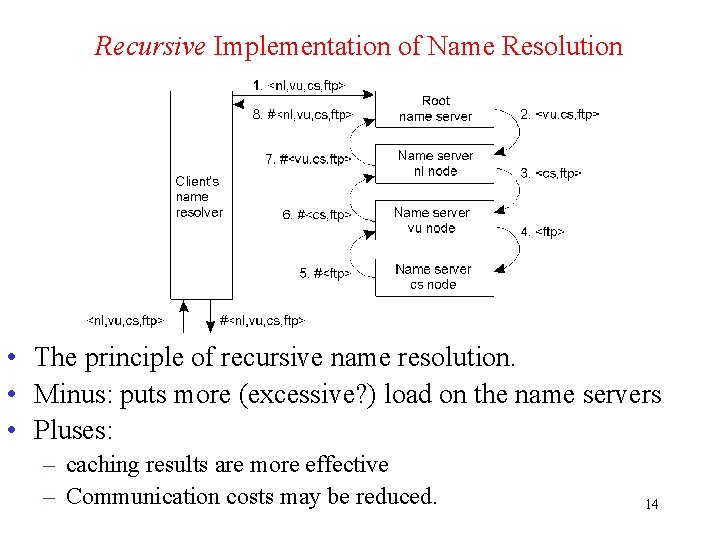

Recursive Implementation of Name Resolution • The principle of recursive name resolution. • Minus: puts more (excessive? ) load on the name servers • Pluses: – caching results are more effective – Communication costs may be reduced. 14

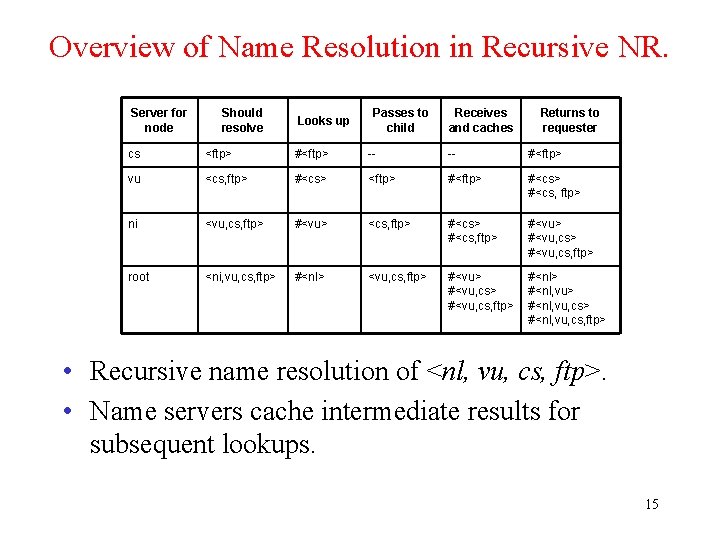

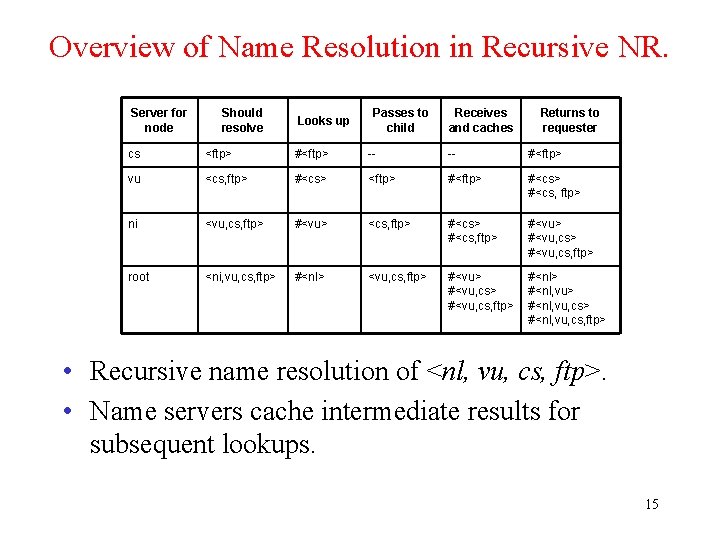

Overview of Name Resolution in Recursive NR. Server for node Should resolve Looks up Passes to child Receives and caches Returns to requester cs <ftp> #<ftp> -- -- #<ftp> vu <cs, ftp> #<cs> <ftp> #<cs> #<cs, ftp> ni <vu, cs, ftp> #<vu> <cs, ftp> #<cs, ftp> #<vu, cs> #<vu, cs, ftp> root <ni, vu, cs, ftp> #<nl> <vu, cs, ftp> #<vu, cs> #<vu, cs, ftp> #<nl, vu> #<nl, vu, cs, ftp> • Recursive name resolution of <nl, vu, cs, ftp>. • Name servers cache intermediate results for subsequent lookups. 15

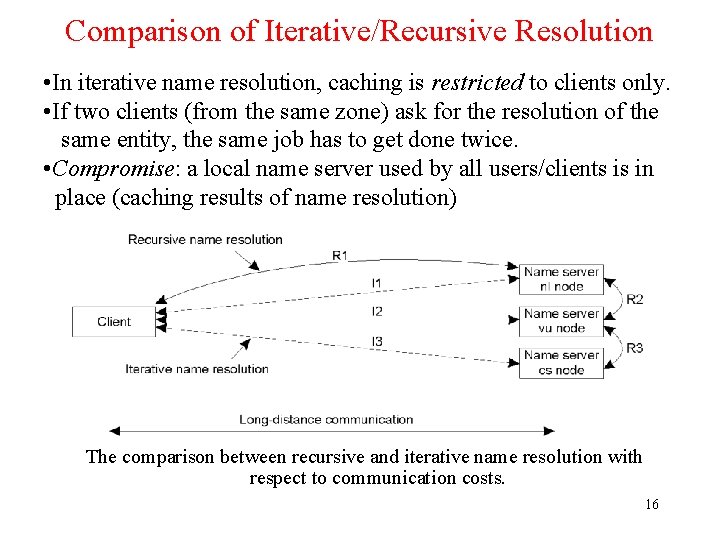

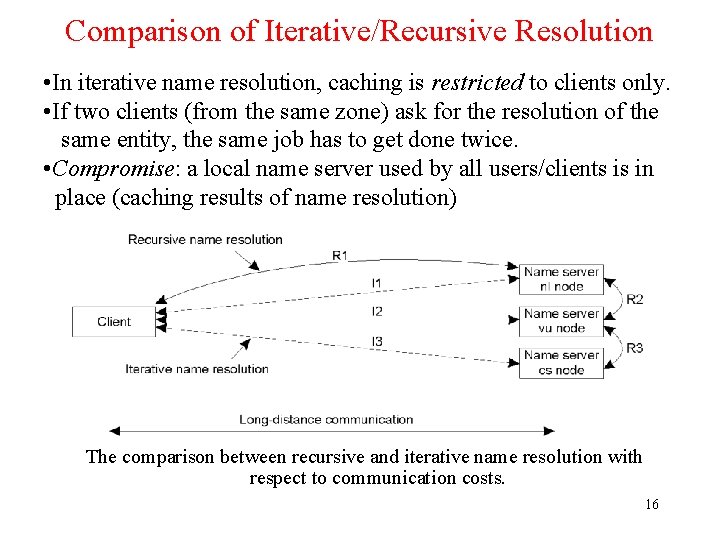

Comparison of Iterative/Recursive Resolution • In iterative name resolution, caching is restricted to clients only. • If two clients (from the same zone) ask for the resolution of the same entity, the same job has to get done twice. • Compromise: a local name server used by all users/clients is in place (caching results of name resolution) The comparison between recursive and iterative name resolution with respect to communication costs. 16

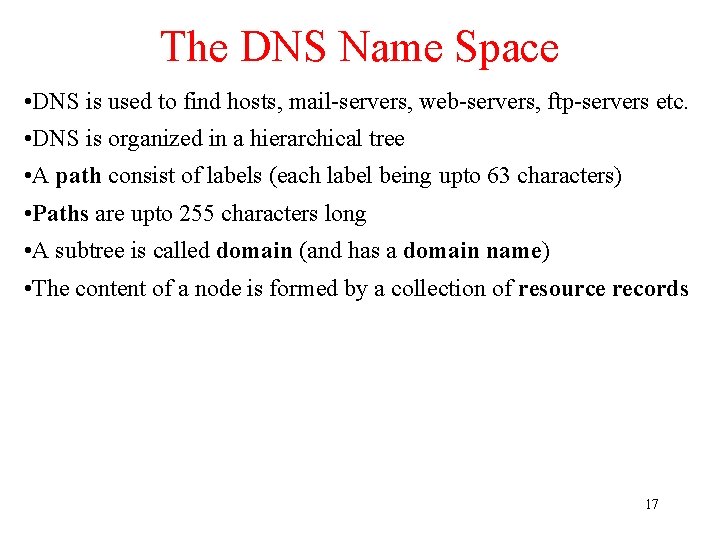

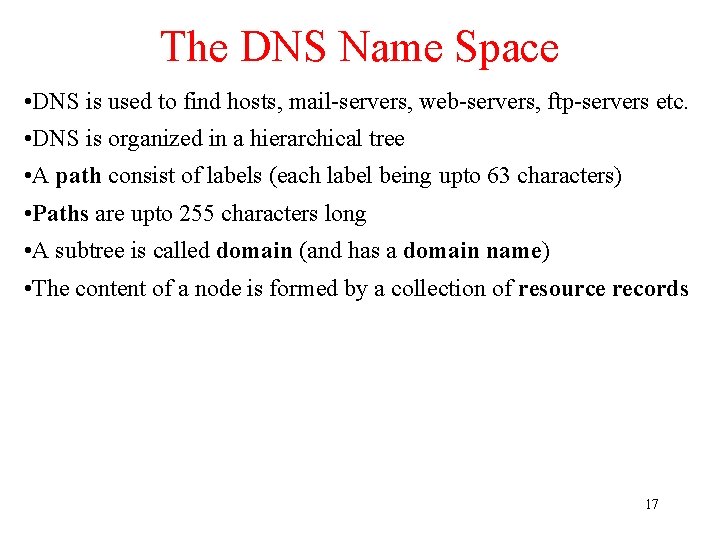

The DNS Name Space • DNS is used to find hosts, mail-servers, web-servers, ftp-servers etc. • DNS is organized in a hierarchical tree • A path consist of labels (each label being upto 63 characters) • Paths are upto 255 characters long • A subtree is called domain (and has a domain name) • The content of a node is formed by a collection of resource records 17

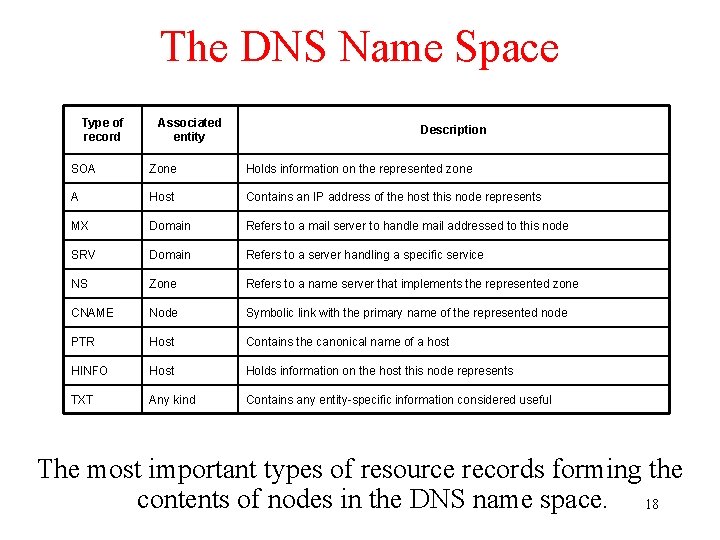

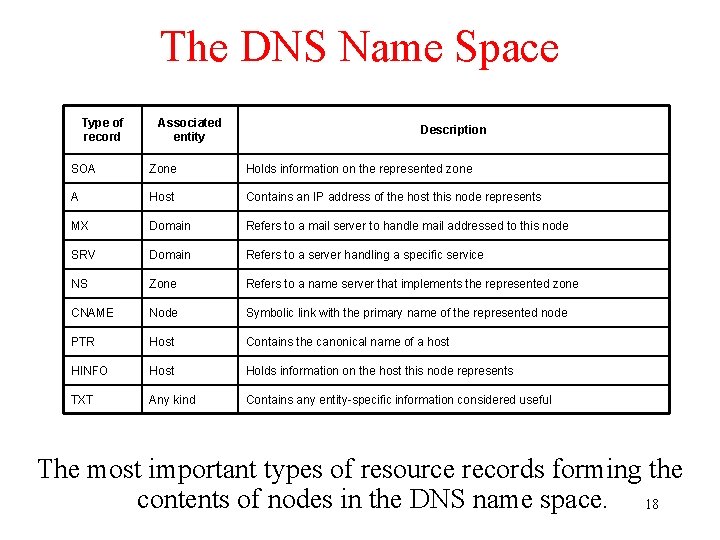

The DNS Name Space Type of record Associated entity Description SOA Zone Holds information on the represented zone A Host Contains an IP address of the host this node represents MX Domain Refers to a mail server to handle mail addressed to this node SRV Domain Refers to a server handling a specific service NS Zone Refers to a name server that implements the represented zone CNAME Node Symbolic link with the primary name of the represented node PTR Host Contains the canonical name of a host HINFO Host Holds information on the host this node represents TXT Any kind Contains any entity-specific information considered useful The most important types of resource records forming the contents of nodes in the DNS name space. 18

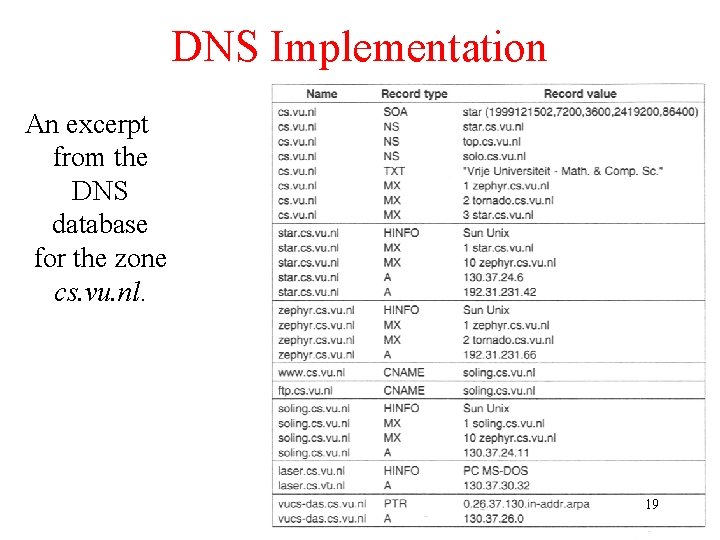

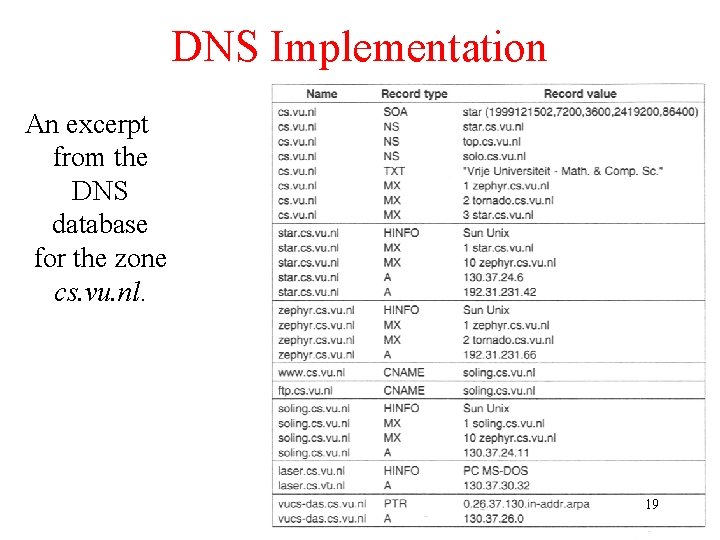

DNS Implementation An excerpt from the DNS database for the zone cs. vu. nl. 19

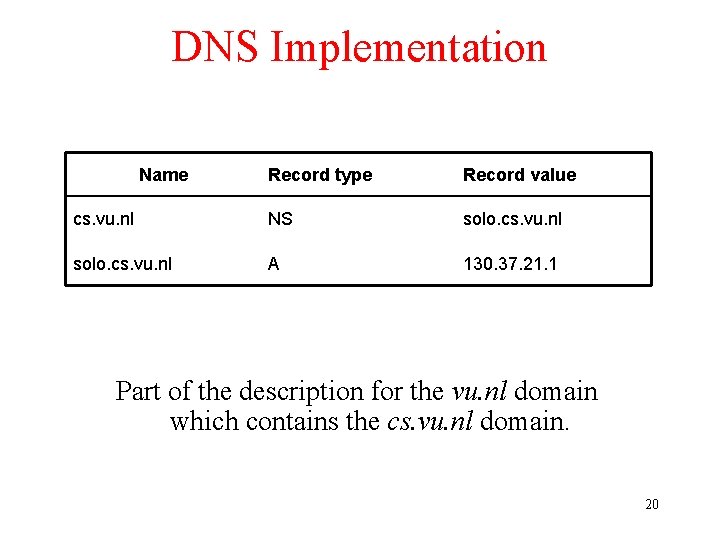

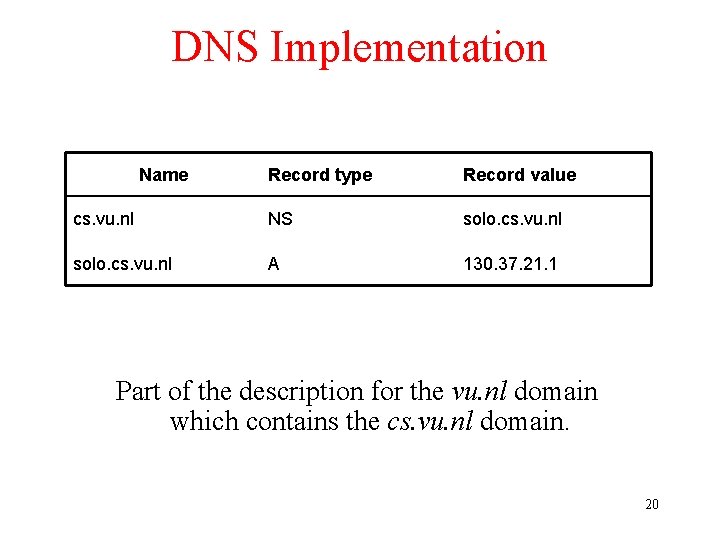

DNS Implementation Name Record type Record value cs. vu. nl NS solo. cs. vu. nl A 130. 37. 21. 1 Part of the description for the vu. nl domain which contains the cs. vu. nl domain. 20

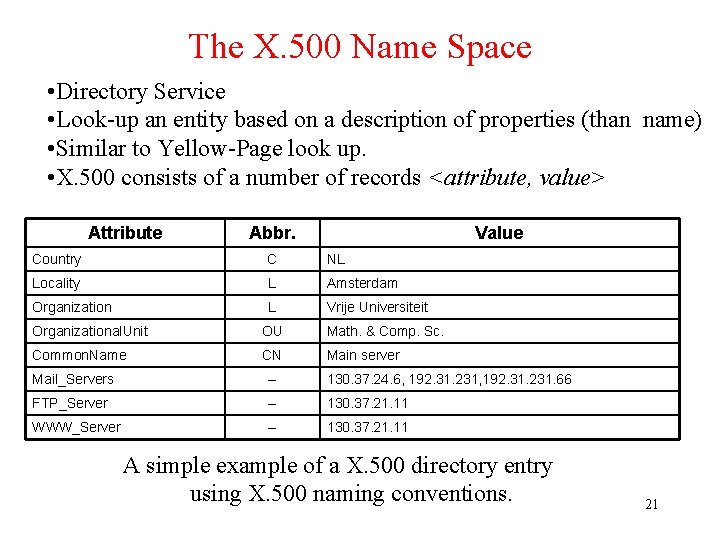

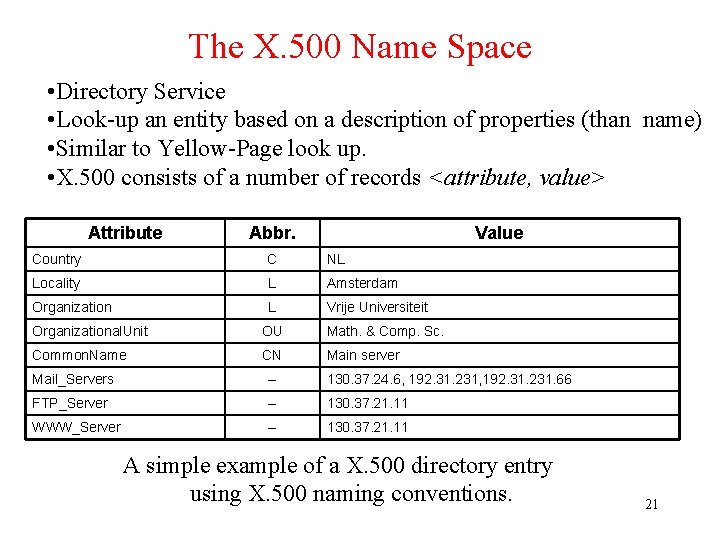

The X. 500 Name Space • Directory Service • Look-up an entity based on a description of properties (than name) • Similar to Yellow-Page look up. • X. 500 consists of a number of records <attribute, value> Attribute Abbr. Value Country C NL Locality L Amsterdam Organization L Vrije Universiteit Organizational. Unit OU Math. & Comp. Sc. Common. Name CN Main server Mail_Servers -- 130. 37. 24. 6, 192. 31. 231. 66 FTP_Server -- 130. 37. 21. 11 WWW_Server -- 130. 37. 21. 11 A simple example of a X. 500 directory entry using X. 500 naming conventions. 21

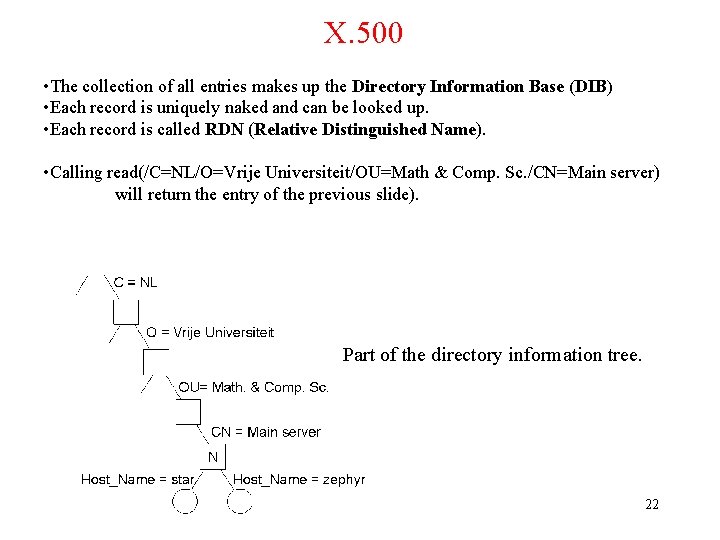

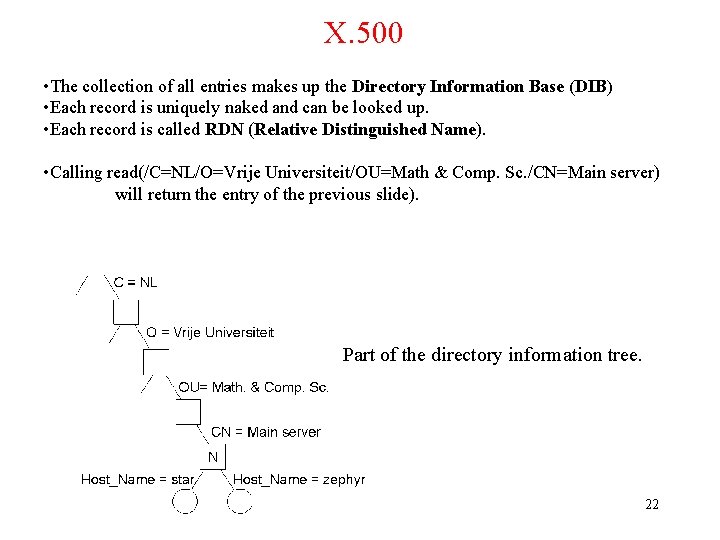

X. 500 • The collection of all entries makes up the Directory Information Base (DIB) • Each record is uniquely naked and can be looked up. • Each record is called RDN (Relative Distinguished Name). • Calling read(/C=NL/O=Vrije Universiteit/OU=Math & Comp. Sc. /CN=Main server) will return the entry of the previous slide). Part of the directory information tree. 22

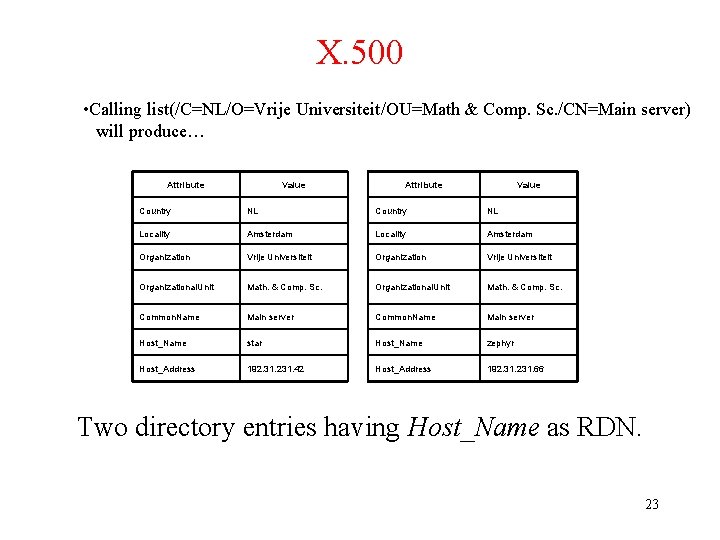

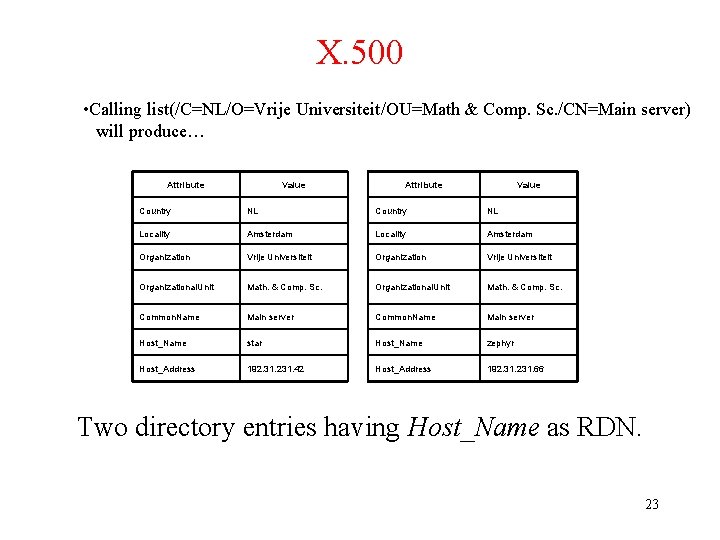

X. 500 • Calling list(/C=NL/O=Vrije Universiteit/OU=Math & Comp. Sc. /CN=Main server) will produce… Attribute Value Country NL Locality Amsterdam Organization Vrije Universiteit Organizational. Unit Math. & Comp. Sc. Common. Name Main server Host_Name star Host_Name zephyr Host_Address 192. 31. 231. 42 Host_Address 192. 31. 231. 66 Two directory entries having Host_Name as RDN. 23

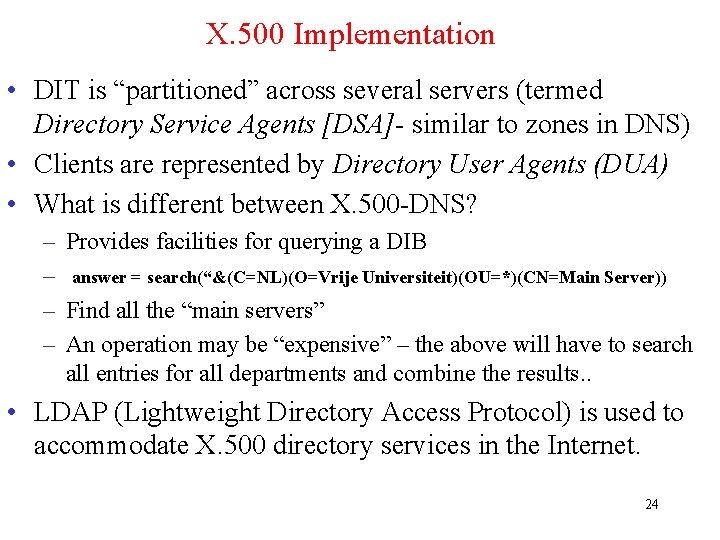

X. 500 Implementation • DIT is “partitioned” across several servers (termed Directory Service Agents [DSA]- similar to zones in DNS) • Clients are represented by Directory User Agents (DUA) • What is different between X. 500 -DNS? – Provides facilities for querying a DIB – answer = search(“&(C=NL)(O=Vrije Universiteit)(OU=*)(CN=Main Server)) – Find all the “main servers” – An operation may be “expensive” – the above will have to search all entries for all departments and combine the results. . • LDAP (Lightweight Directory Access Protocol) is used to accommodate X. 500 directory services in the Internet. 24

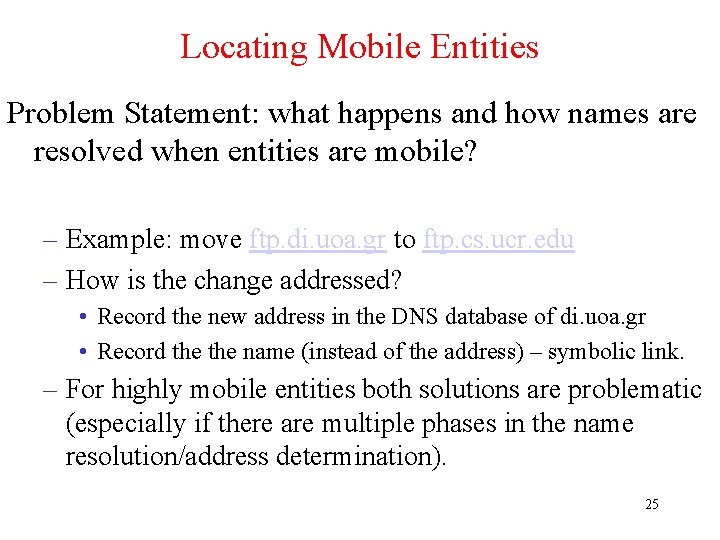

Locating Mobile Entities Problem Statement: what happens and how names are resolved when entities are mobile? – Example: move ftp. di. uoa. gr to ftp. cs. ucr. edu – How is the change addressed? • Record the new address in the DNS database of di. uoa. gr • Record the name (instead of the address) – symbolic link. – For highly mobile entities both solutions are problematic (especially if there are multiple phases in the name resolution/address determination). 25

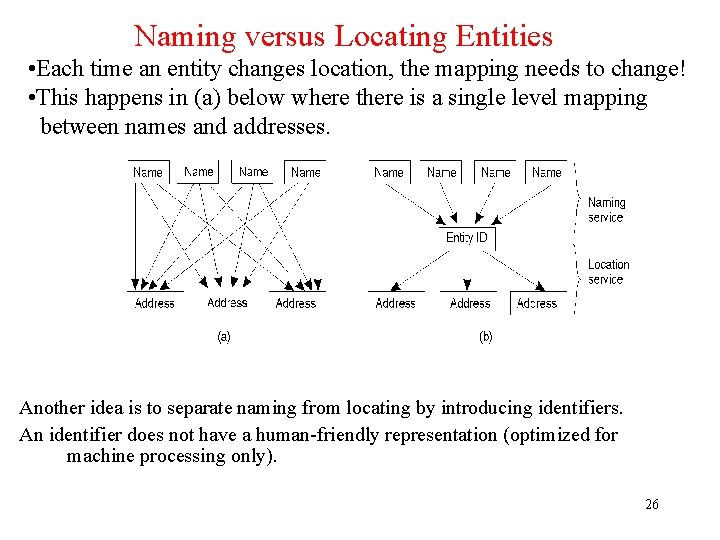

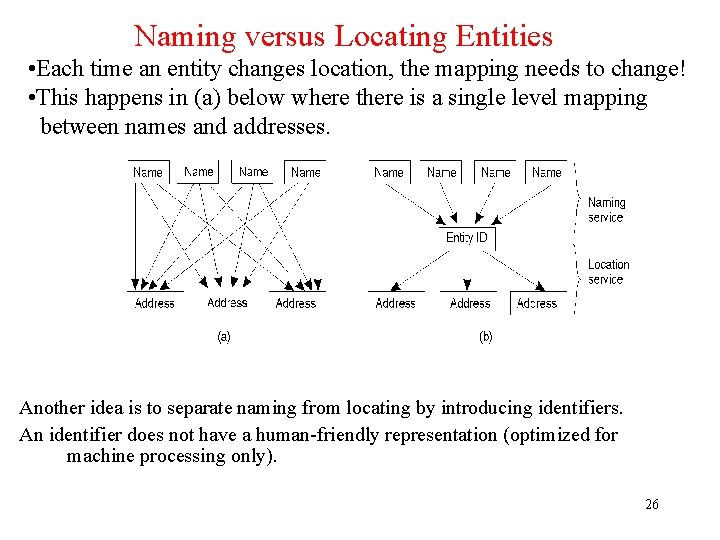

Naming versus Locating Entities • Each time an entity changes location, the mapping needs to change! • This happens in (a) below where there is a single level mapping between names and addresses. Another idea is to separate naming from locating by introducing identifiers. An identifier does not have a human-friendly representation (optimized for machine processing only). 26

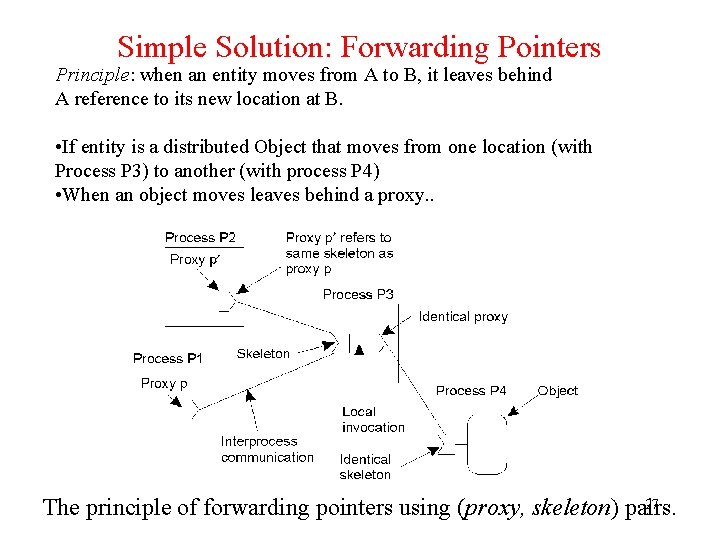

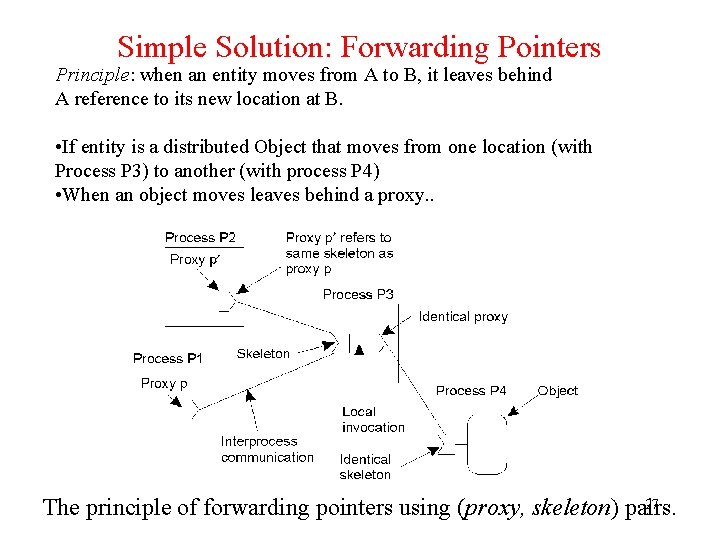

Simple Solution: Forwarding Pointers Principle: when an entity moves from A to B, it leaves behind A reference to its new location at B. • If entity is a distributed Object that moves from one location (with Process P 3) to another (with process P 4) • When an object moves leaves behind a proxy. . 27 The principle of forwarding pointers using (proxy, skeleton) pairs.

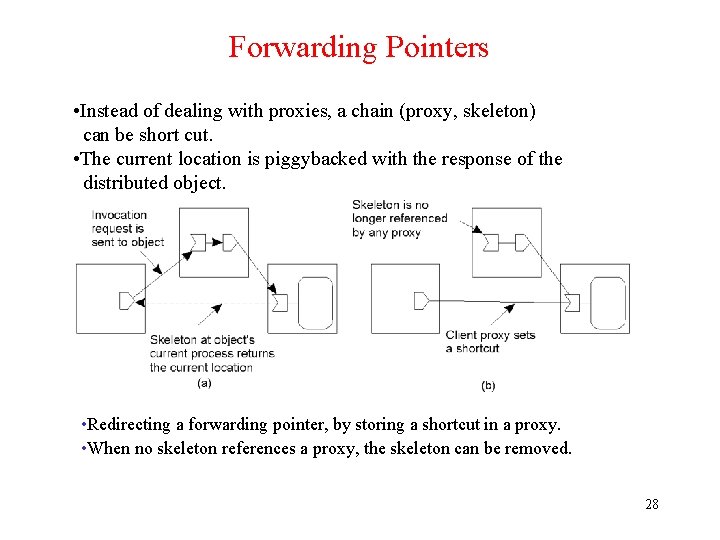

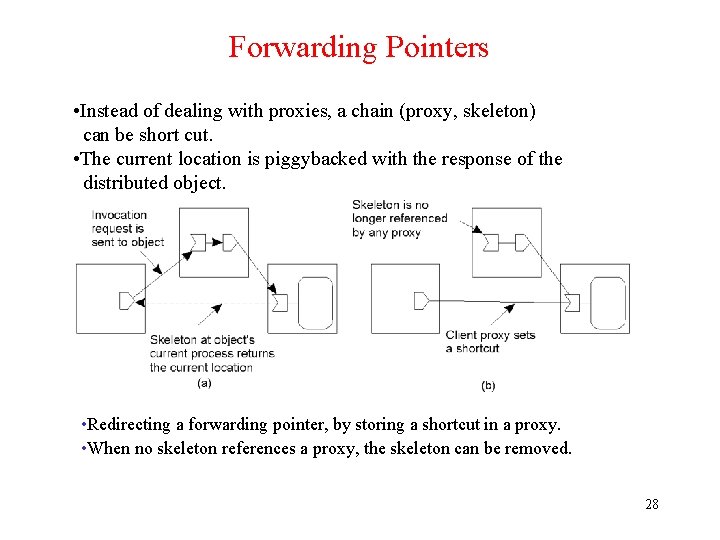

Forwarding Pointers • Instead of dealing with proxies, a chain (proxy, skeleton) can be short cut. • The current location is piggybacked with the response of the distributed object. • Redirecting a forwarding pointer, by storing a shortcut in a proxy. • When no skeleton references a proxy, the skeleton can be removed. 28

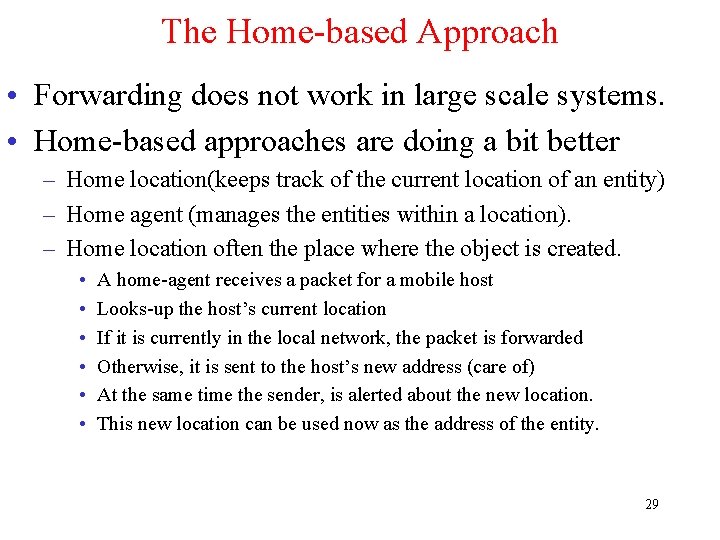

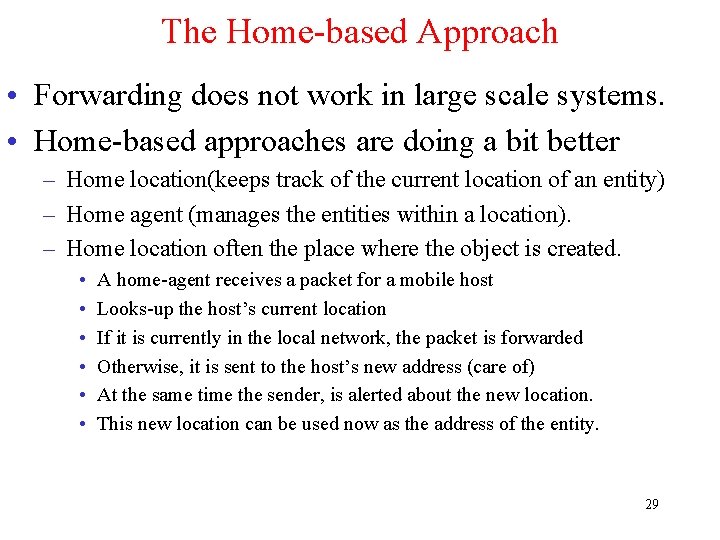

The Home-based Approach • Forwarding does not work in large scale systems. • Home-based approaches are doing a bit better – Home location(keeps track of the current location of an entity) – Home agent (manages the entities within a location). – Home location often the place where the object is created. • • • A home-agent receives a packet for a mobile host Looks-up the host’s current location If it is currently in the local network, the packet is forwarded Otherwise, it is sent to the host’s new address (care of) At the same time the sender, is alerted about the new location. This new location can be used now as the address of the entity. 29

![HomeBased Approach The principle of Mobile IP Perkins 97 30 Home-Based Approach The principle of Mobile IP [Perkins 97] 30](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/58bca5b22e1dec7b368ef676dd453acf/image-30.jpg)

Home-Based Approach The principle of Mobile IP [Perkins 97] 30

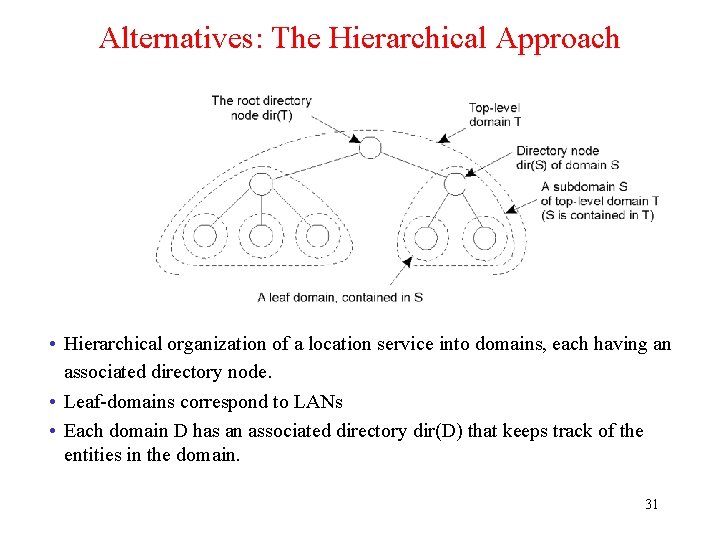

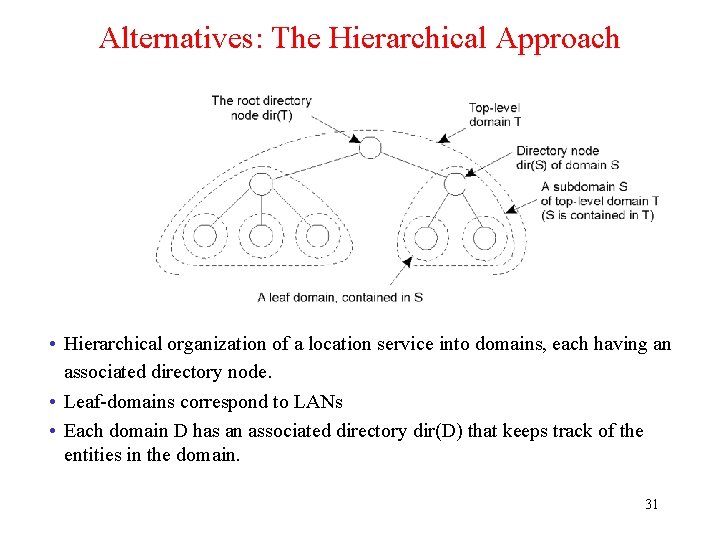

Alternatives: The Hierarchical Approach • Hierarchical organization of a location service into domains, each having an associated directory node. • Leaf-domains correspond to LANs • Each domain D has an associated directory dir(D) that keeps track of the entities in the domain. 31

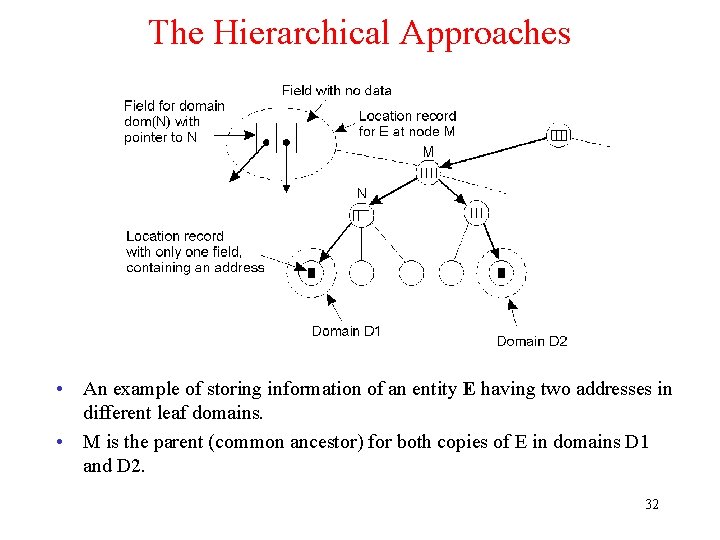

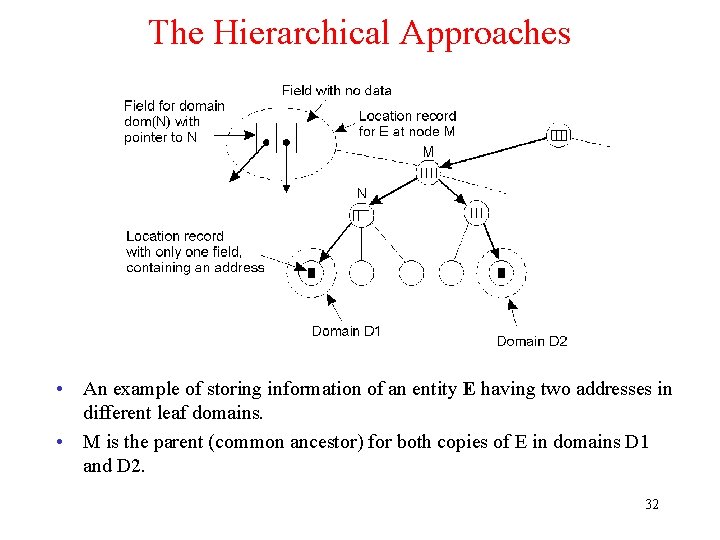

The Hierarchical Approaches • An example of storing information of an entity E having two addresses in different leaf domains. • M is the parent (common ancestor) for both copies of E in domains D 1 and D 2. 32

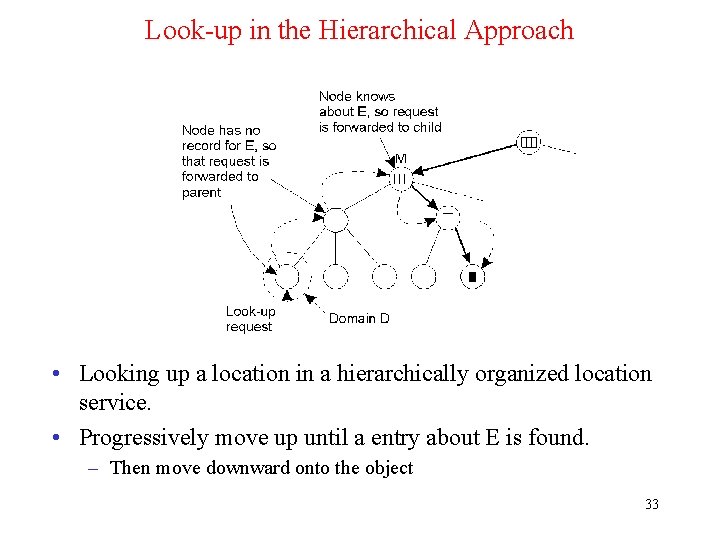

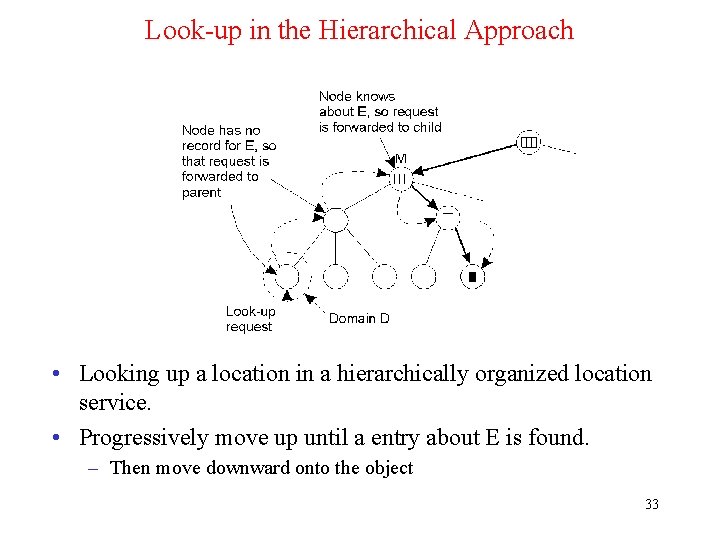

Look-up in the Hierarchical Approach • Looking up a location in a hierarchically organized location service. • Progressively move up until a entry about E is found. – Then move downward onto the object 33

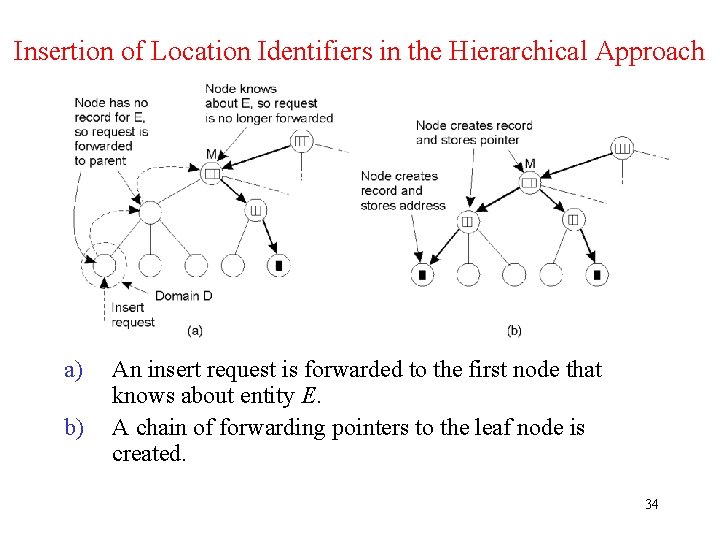

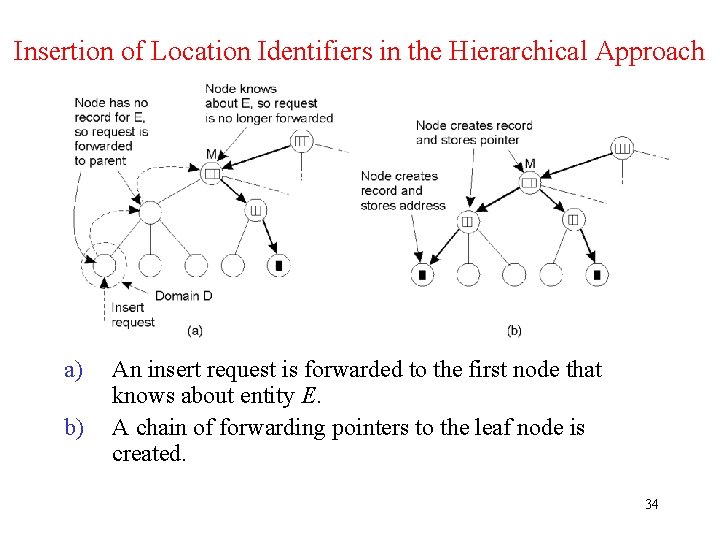

Insertion of Location Identifiers in the Hierarchical Approach a) b) An insert request is forwarded to the first node that knows about entity E. A chain of forwarding pointers to the leaf node is created. 34

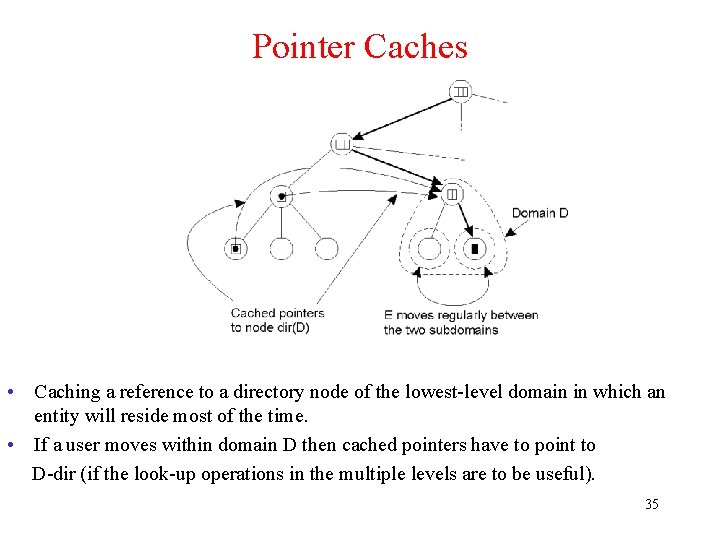

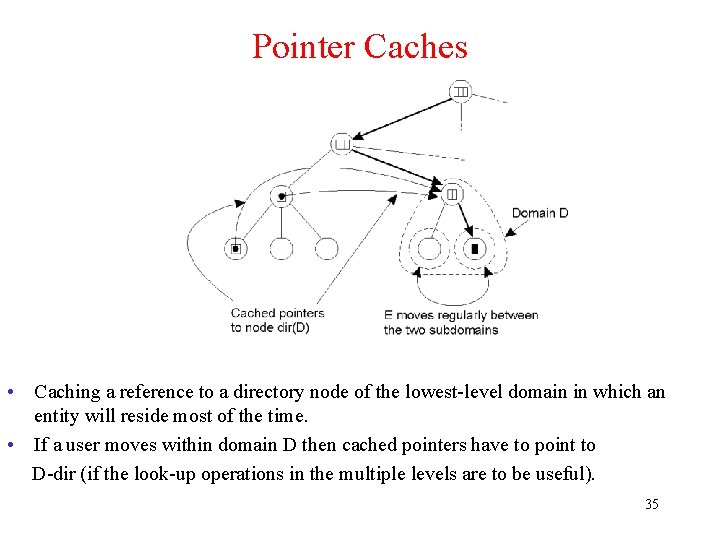

Pointer Caches • Caching a reference to a directory node of the lowest-level domain in which an entity will reside most of the time. • If a user moves within domain D then cached pointers have to point to D-dir (if the look-up operations in the multiple levels are to be useful). 35

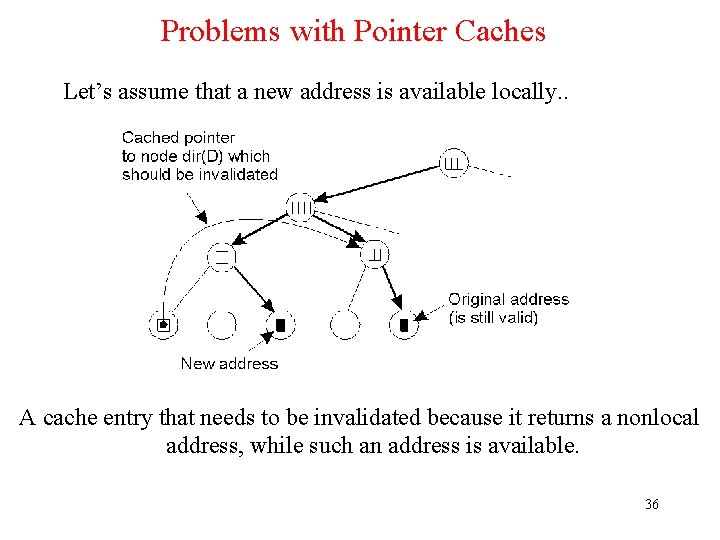

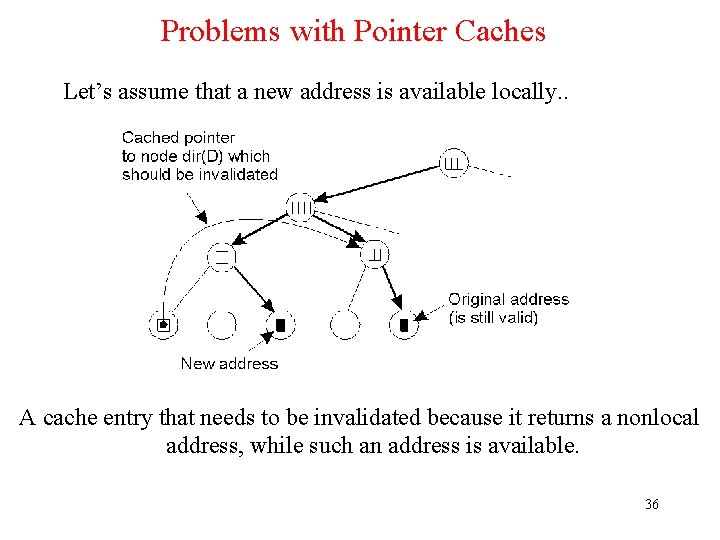

Problems with Pointer Caches Let’s assume that a new address is available locally. . A cache entry that needs to be invalidated because it returns a nonlocal address, while such an address is available. 36

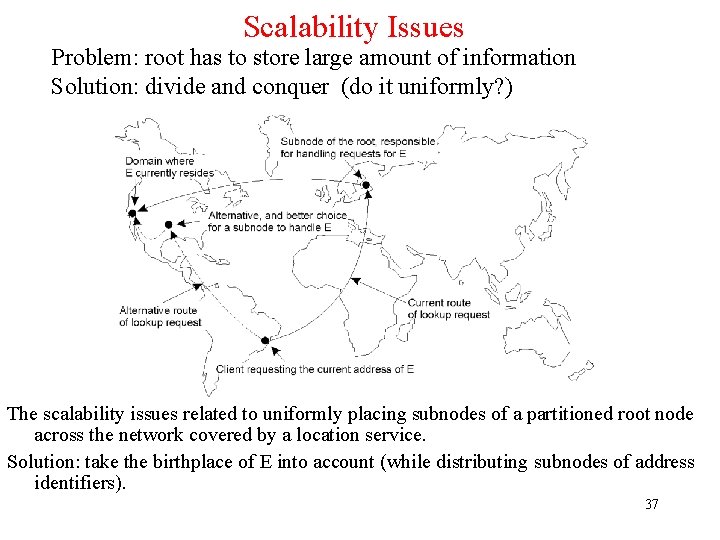

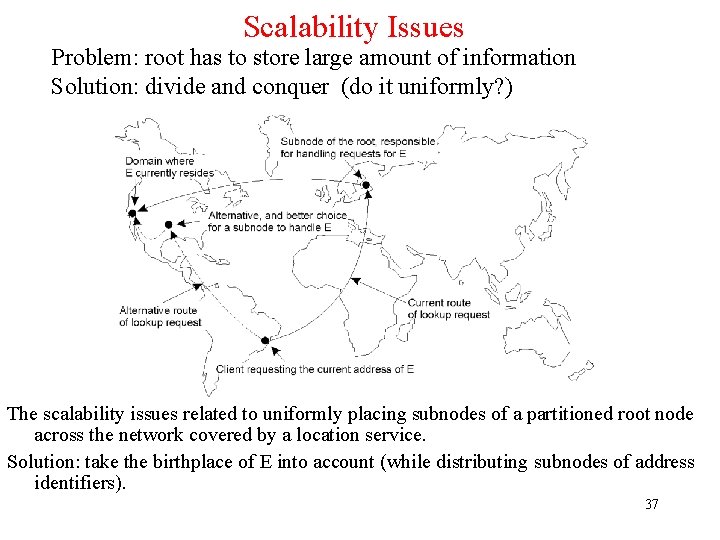

Scalability Issues Problem: root has to store large amount of information Solution: divide and conquer (do it uniformly? ) The scalability issues related to uniformly placing subnodes of a partitioned root node across the network covered by a location service. Solution: take the birthplace of E into account (while distributing subnodes of address identifiers). 37

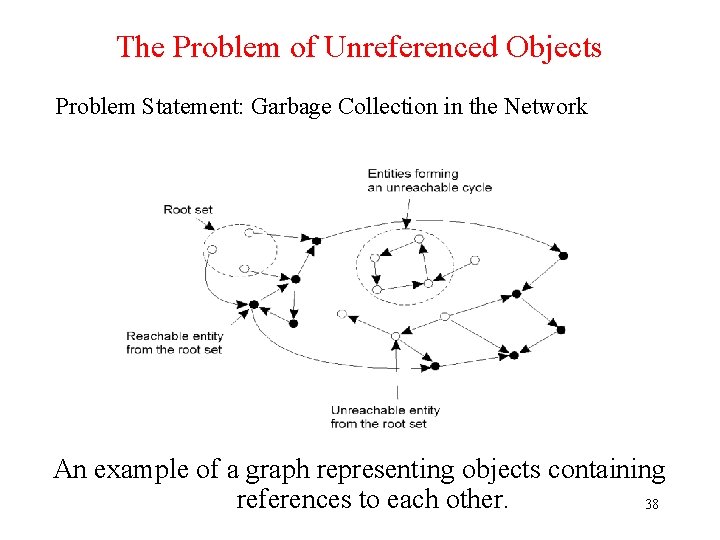

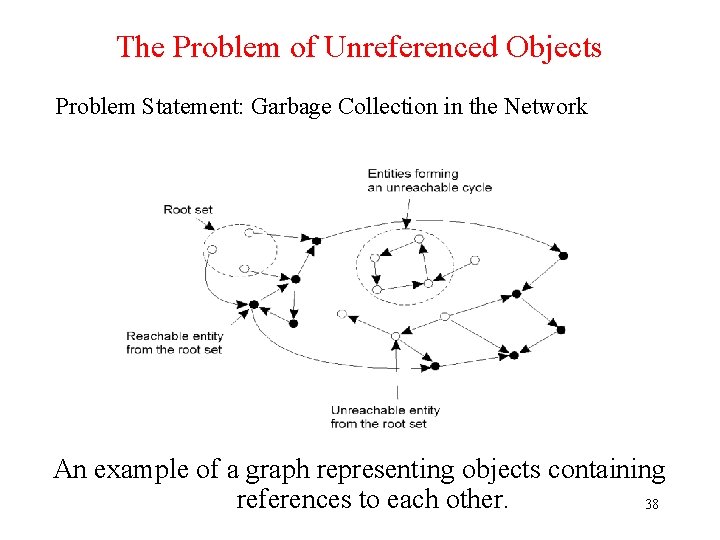

The Problem of Unreferenced Objects Problem Statement: Garbage Collection in the Network An example of a graph representing objects containing references to each other. 38

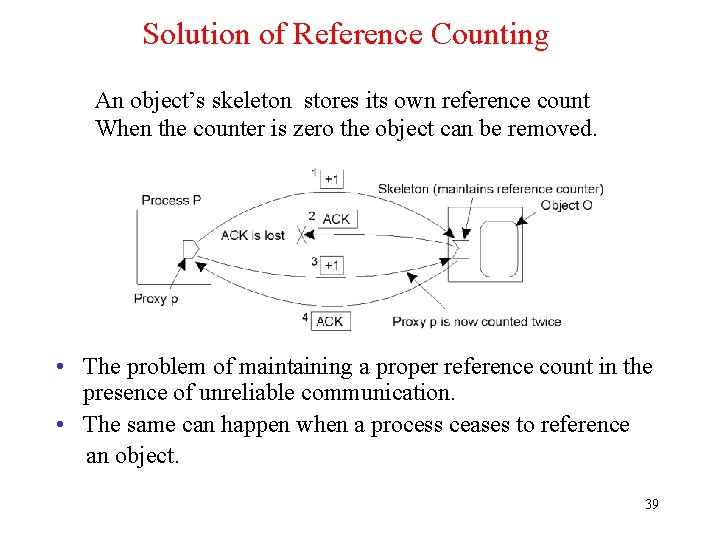

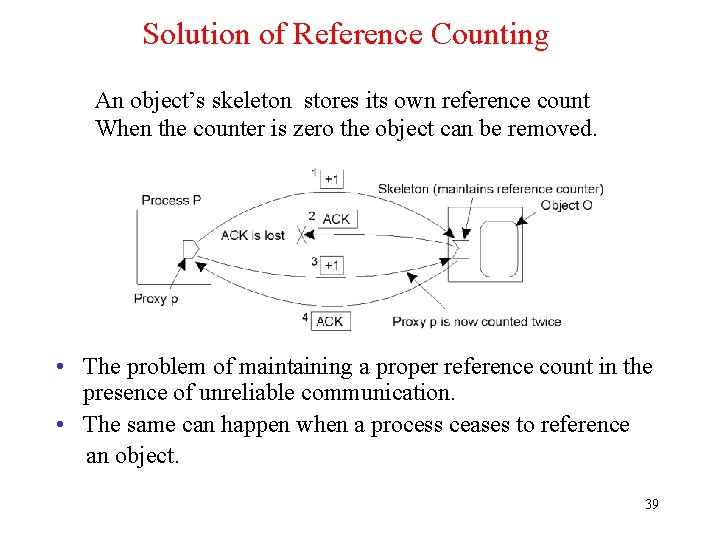

Solution of Reference Counting An object’s skeleton stores its own reference count When the counter is zero the object can be removed. • The problem of maintaining a proper reference count in the presence of unreliable communication. • The same can happen when a process ceases to reference an object. 39

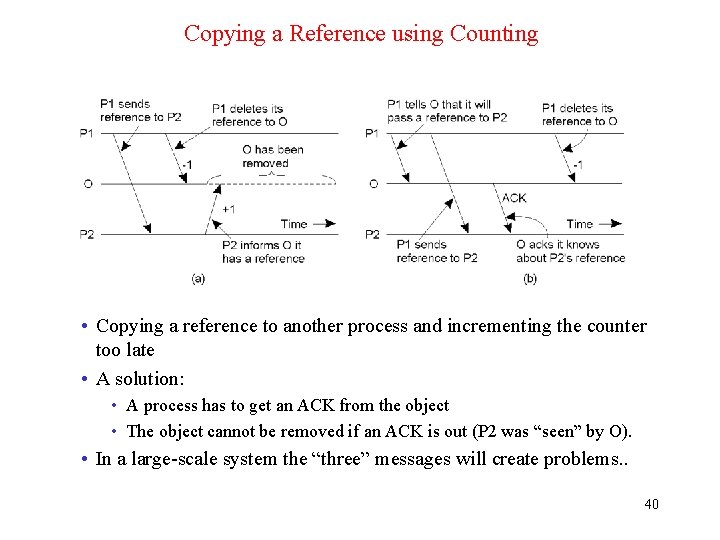

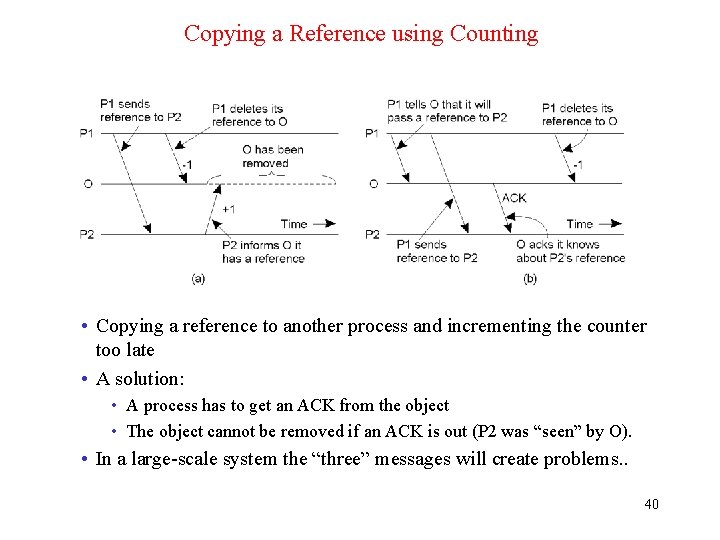

Copying a Reference using Counting • Copying a reference to another process and incrementing the counter too late • A solution: • A process has to get an ACK from the object • The object cannot be removed if an ACK is out (P 2 was “seen” by O). • In a large-scale system the “three” messages will create problems. . 40

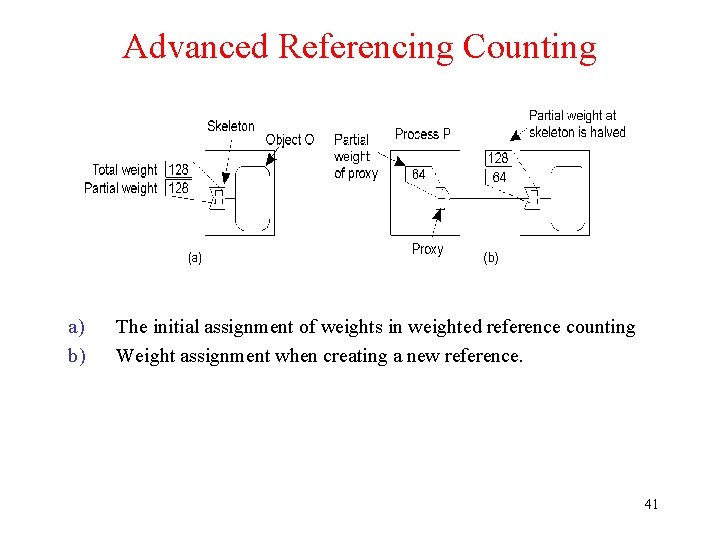

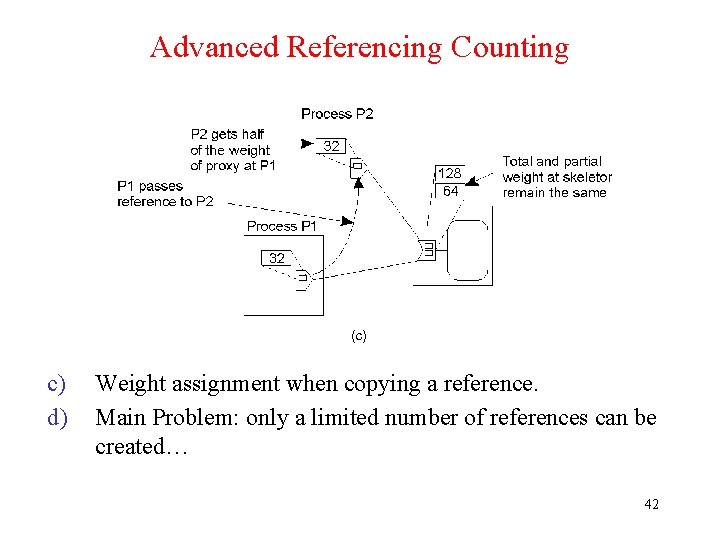

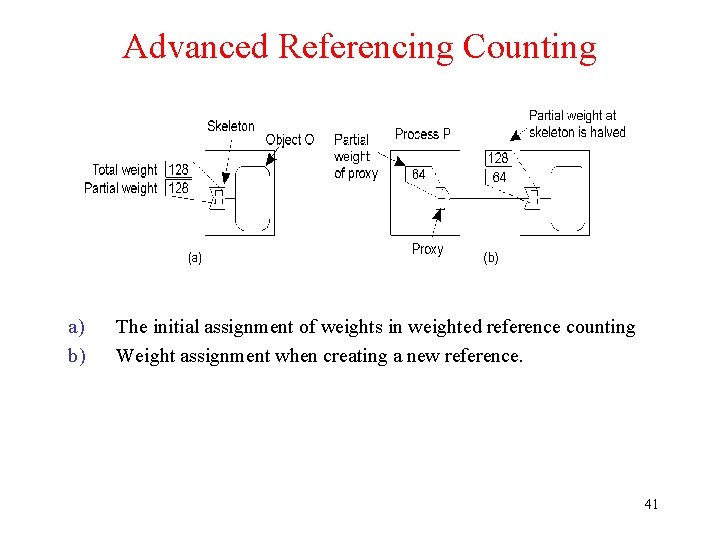

Advanced Referencing Counting a) b) The initial assignment of weights in weighted reference counting Weight assignment when creating a new reference. 41

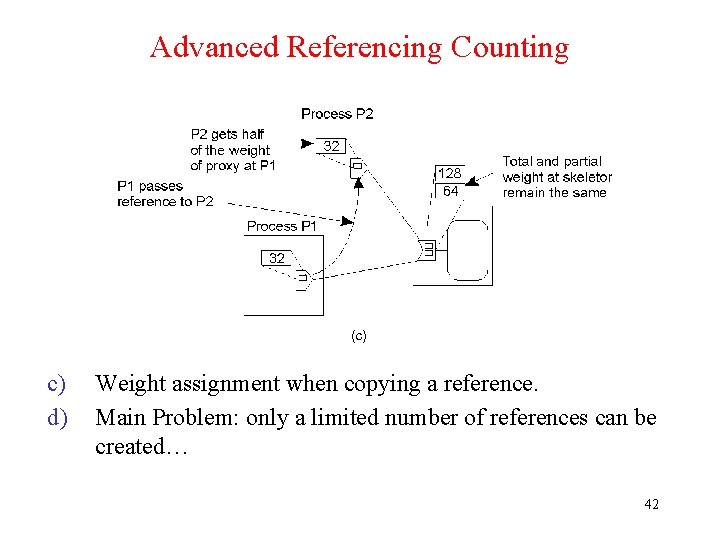

Advanced Referencing Counting c) d) Weight assignment when copying a reference. Main Problem: only a limited number of references can be created… 42

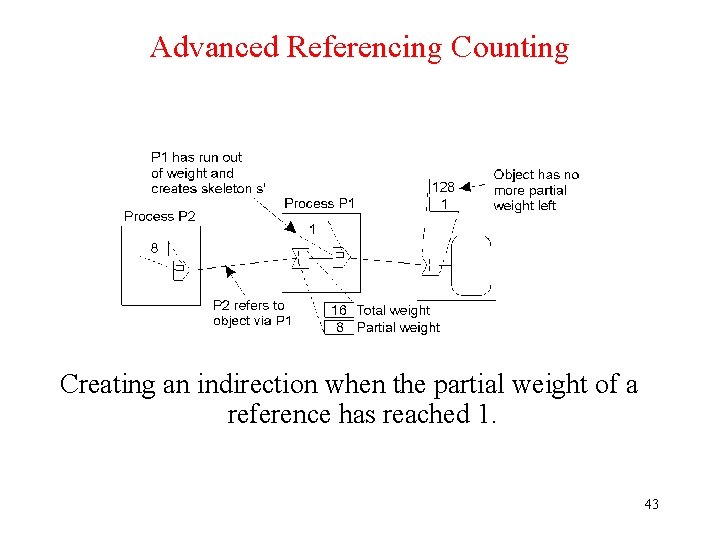

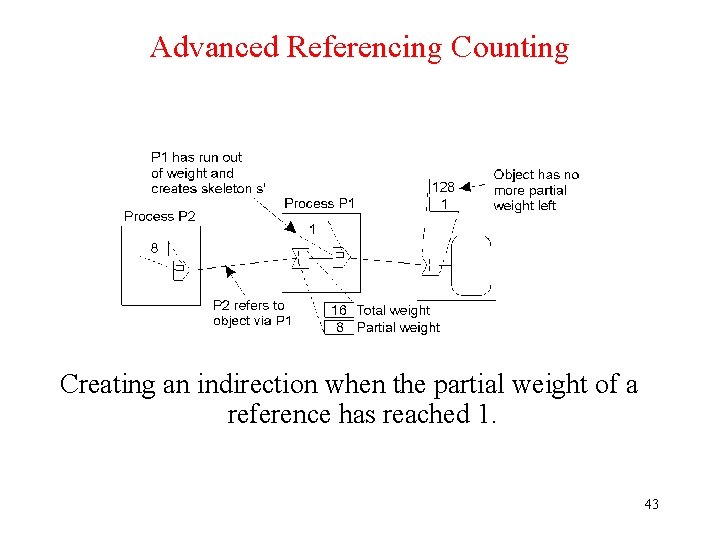

Advanced Referencing Counting Creating an indirection when the partial weight of a reference has reached 1. 43

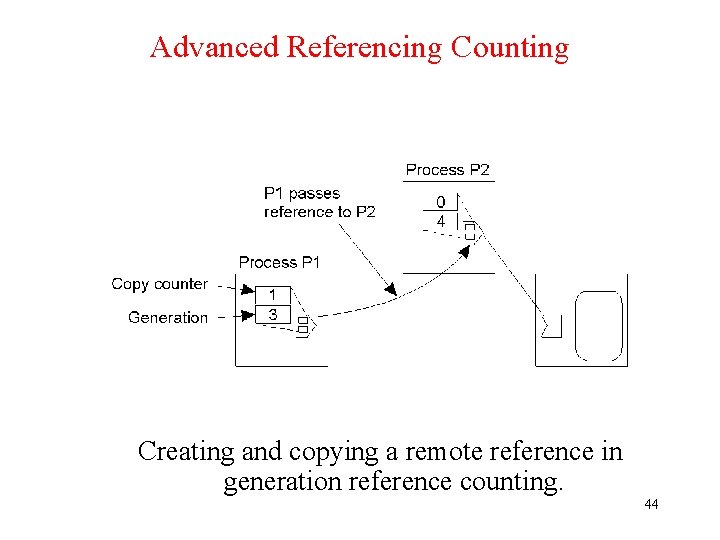

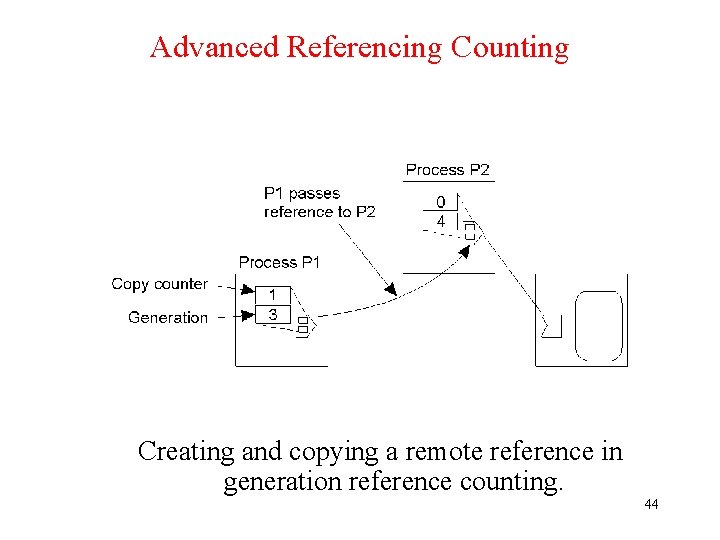

Advanced Referencing Counting Creating and copying a remote reference in generation reference counting. 44

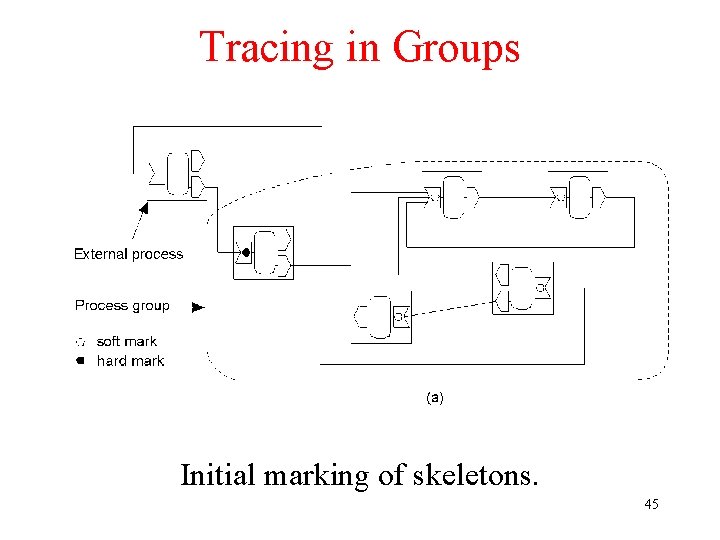

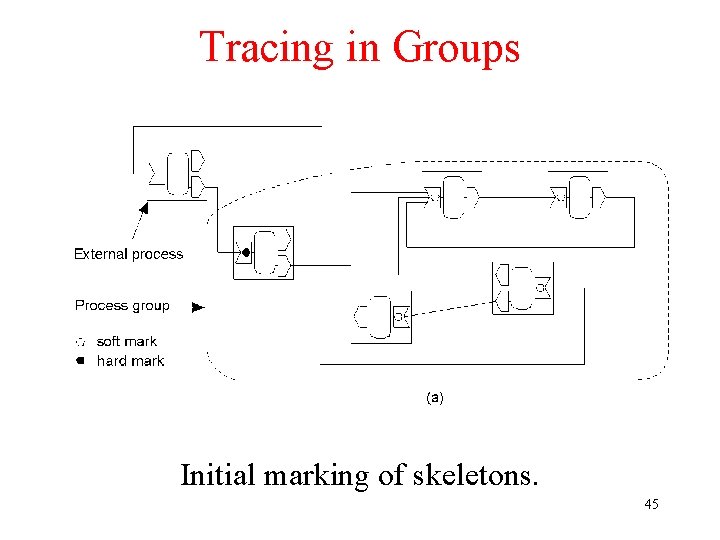

Tracing in Groups Initial marking of skeletons. 45

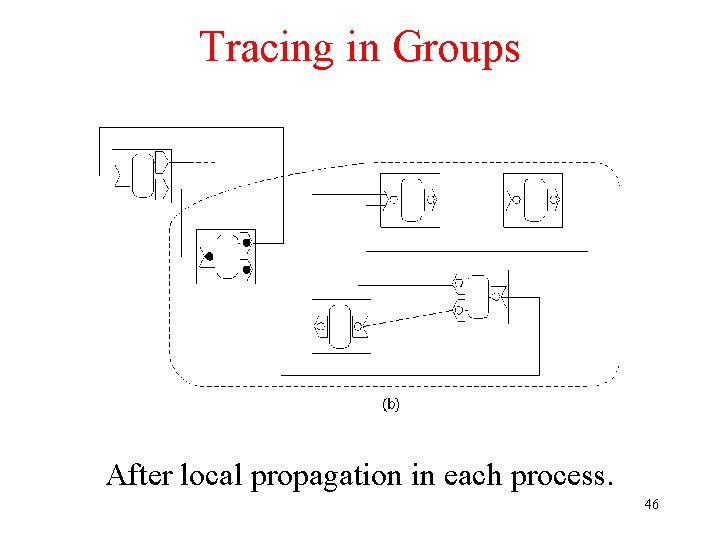

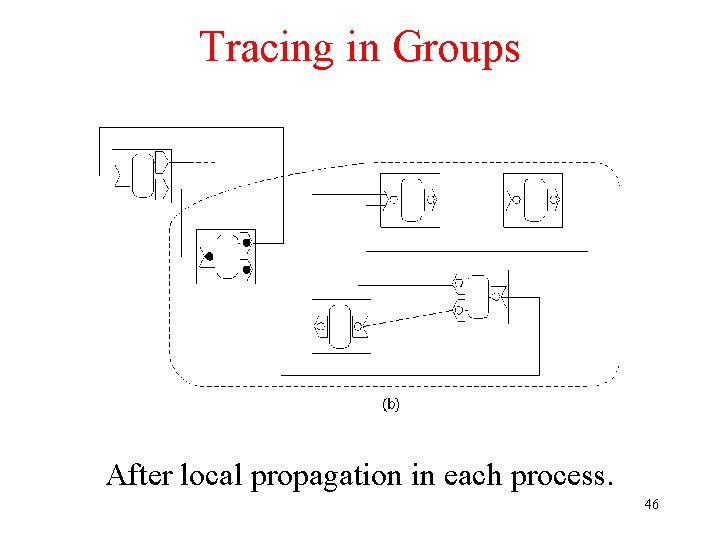

Tracing in Groups After local propagation in each process. 46

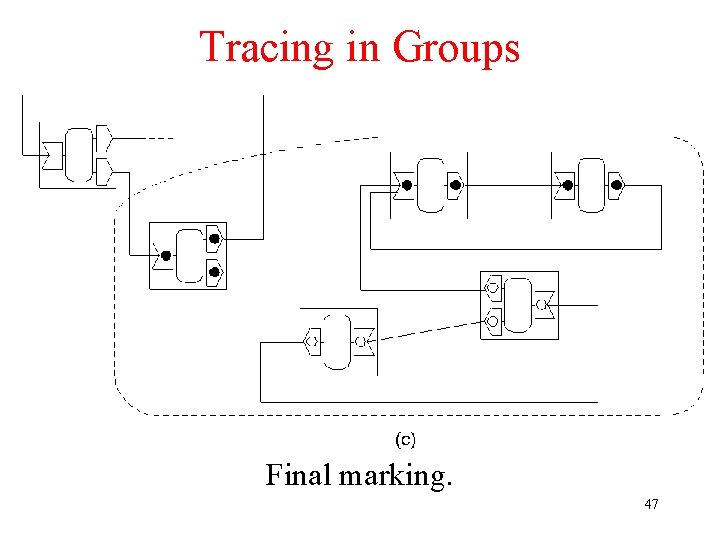

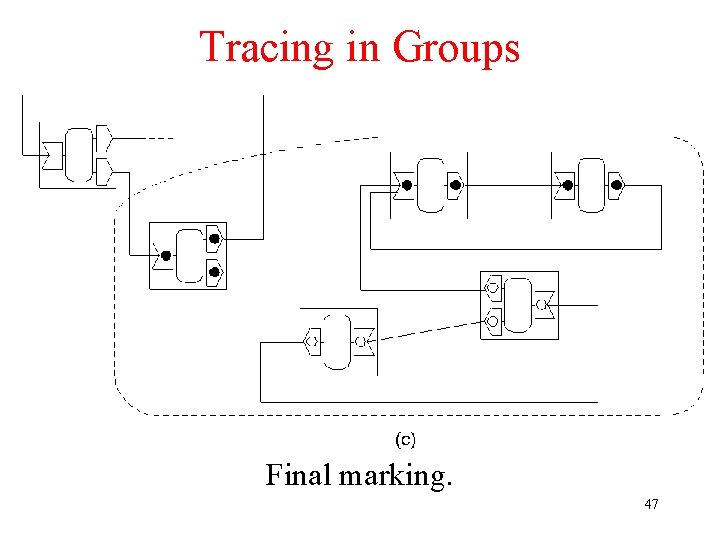

Tracing in Groups Final marking. 47