Music increases frontal EEG coherence during verbal learning

Music increases frontal EEG coherence during verbal learning David A. Peterson a, b, c, ∗, Michael H. Thaut b, c a Department of Computer Science, Colorado State University b Program in Molecular, Cellular, and Integrative Neuroscience Colorado State University c Center for Biomedical Research in Music, Colorado State University Neuroscience Letters 412 (2007) 217 -221 Ranelle Johnson

Introduction (others said…) • Memory may be subserved by oscillations in recurrent networks within and between brain regions (in theory) • Increased multi band spectral power in the EEG during encoding is associated with successful subsequent word recall

Introduction • In an earlier study… – verbal learning is associated with broadband increases in EEG power spectra – Music influences the topographic distribution of the increased spectral power • Present study… – examining spatial coherence in EEG measured during learning phase

Independent Variable • Treatment Groups – Learning to recall in conventional speaking voice – Learning to recall while singing to melody

Dependent Variable Theoretical Construct - verbal learning Operational Definition - Transition from not being able to recall to being able to recall a word that is repeatedly presented in the AVLT

Dependent Variable • Theoretical Construct – Learning related changes in coherence (LRCC) • Operational Definition – Percent increase or decrease in coherence comparing “first recalled” words to the same words not recalled during the immediately preceding trial (all pairs of not learned/learned words)

Hypothesis • Learning that persists over short- and long- delays will be associated with “learning related change in coherence” (LRCC) in frontal EEG

Hypothesis • The temporally structured learning template provided by music will strengthen LRCC patterns in frontal EEG compared to conventional spoken learning.

Subjects • 16 healthy right-handed volunteers – Normal hearing – No history- neurological or psychiatric conditions • Randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions in a in between-subjects design • Age range – 18 -26 (mean=19. 8, SD=2. 8) – 18 -21 (mean=19. 0, SD=1. 0) • Each group contained 7 females

Method • Rey’s Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) – 15 semantically unrelated words – Repeated in 5 learning trials – Subjects free recalled as many words as possible after each recall – 6 th trial- distracter list, 20 minute visual

Method Fig. 1. Rey’s Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) and the operational definitions of: • learning (thickest arrows, during the learning trials—e. g. words 2, 14, 15); • short-delay memory (medium thick arrows to M 1—e. g. words 2, 15); • long-delay memory (thinnest arrows to M 2—e. g. word 2).

Method • Pre-recorded female voice (both conditions) • Music condition- sang simple, repetitive and unfamiliar melody • Made both groups’ list of words same durations (15 sec)

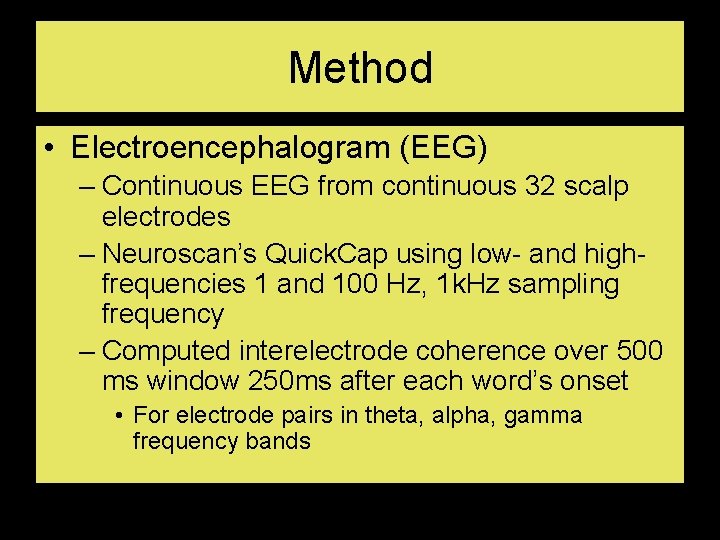

Method • Electroencephalogram (EEG) – Continuous EEG from continuous 32 scalp electrodes – Neuroscan’s Quick. Cap using low- and highfrequencies 1 and 100 Hz, 1 k. Hz sampling frequency – Computed interelectrode coherence over 500 ms window 250 ms after each word’s onset • For electrode pairs in theta, alpha, gamma frequency bands

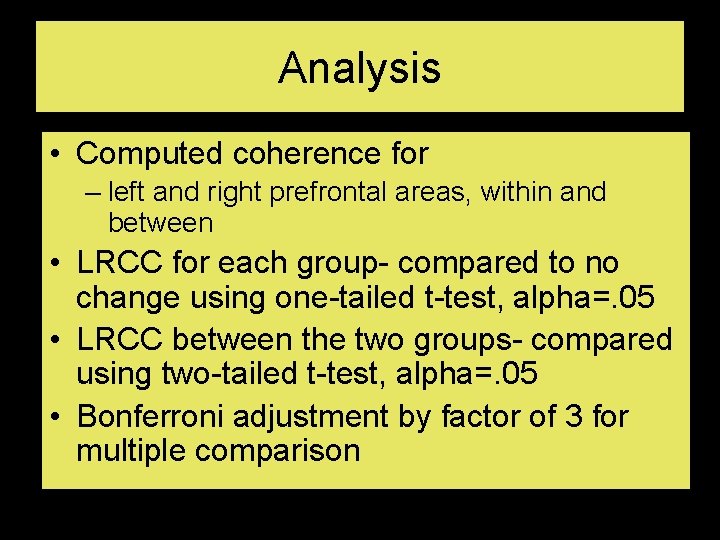

Analysis • Computed coherence for – left and right prefrontal areas, within and between • LRCC for each group- compared to no change using one-tailed t-test, alpha=. 05 • LRCC between the two groups- compared using two-tailed t-test, alpha=. 05 • Bonferroni adjustment by factor of 3 for multiple comparison

Results (performance) • Both groups recalled about 6 more words on the last learned trial than on the first – mean=11 & 4. 9 (spoken) – mean=9. 7 & 4. 3 (music) • Significant improvement in performance – t(16)= 9. 6 & 6. 3, p<0. 0001 • Recall was not significantly different between spoken and musical groups on any trial – t(16)<1. 4, p>0. 1

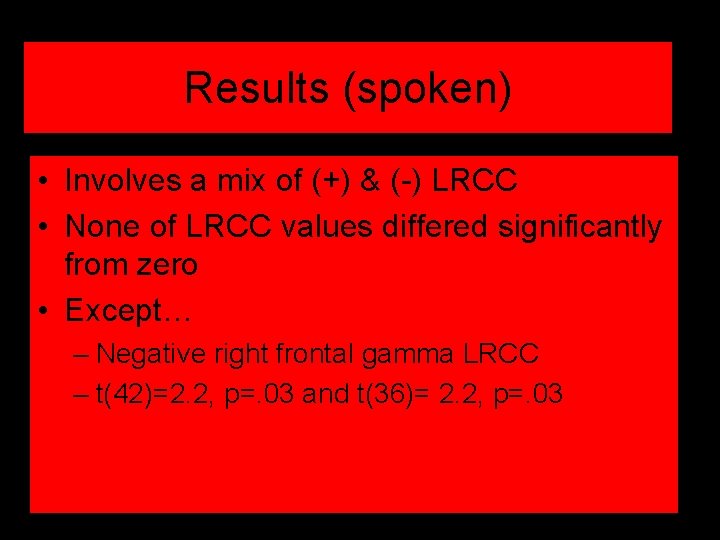

Results (spoken) • Involves a mix of (+) & (-) LRCC • None of LRCC values differed significantly from zero • Except… – Negative right frontal gamma LRCC – t(42)=2. 2, p=. 03 and t(36)= 2. 2, p=. 03

Results (musical) • Involved (+) LRCC within & between the hemispheres • Short-delays – Increased frontal coherence significant for left gamma, t(39)=2. 6, p=. 003 – Interhemispheric theta, t(39)=2. 6, p=. 01

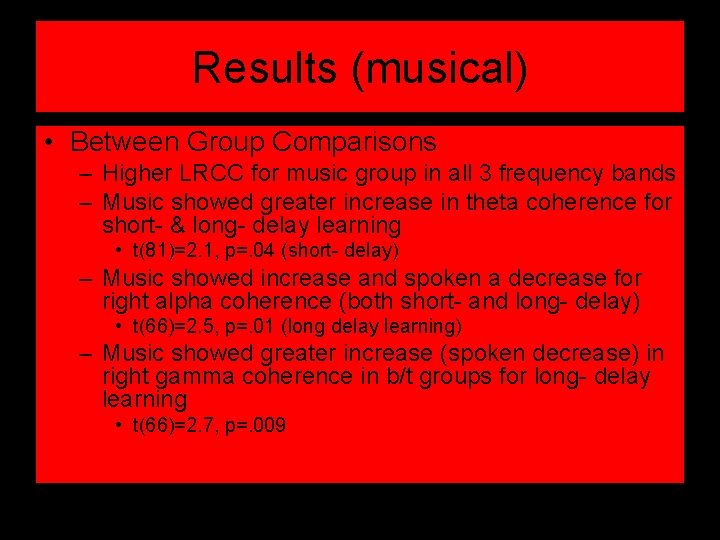

Results (musical) • Between Group Comparisons – Higher LRCC for music group in all 3 frequency bands – Music showed greater increase in theta coherence for short- & long- delay learning • t(81)=2. 1, p=. 04 (short- delay) – Music showed increase and spoken a decrease for right alpha coherence (both short- and long- delay) • t(66)=2. 5, p=. 01 (long delay learning) – Music showed greater increase (spoken decrease) in right gamma coherence in b/t groups for long- delay learning • t(66)=2. 7, p=. 009

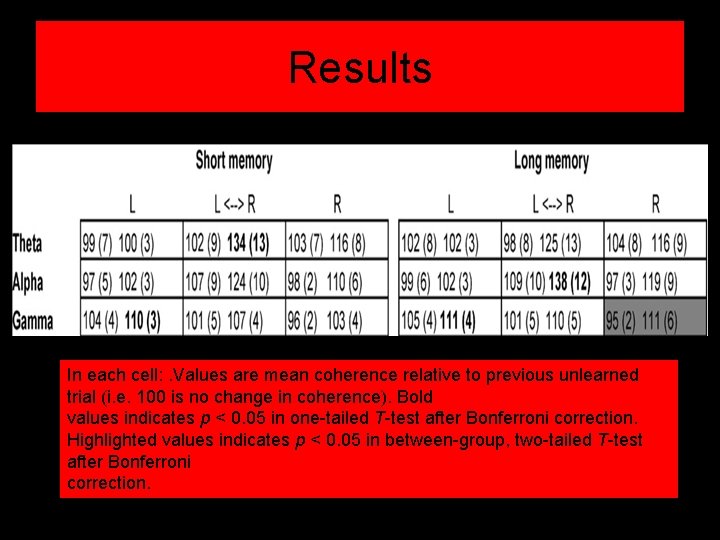

Results In each cell: . Values are mean coherence relative to previous unlearned trial (i. e. 100 is no change in coherence). Bold values indicates p < 0. 05 in one-tailed T-test after Bonferroni correction. Highlighted values indicates p < 0. 05 in between-group, two-tailed T-test after Bonferroni correction.

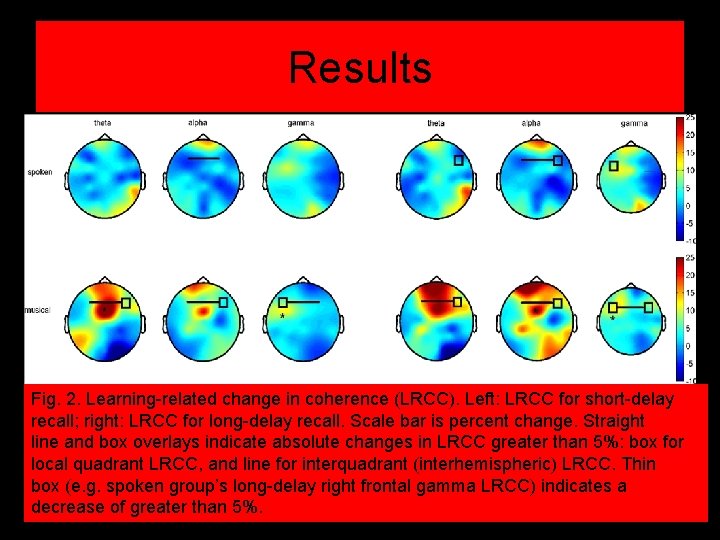

Results Fig. 2. Learning-related change in coherence (LRCC). Left: LRCC for short-delay recall; right: LRCC for long-delay recall. Scale bar is percent change. Straight line and box overlays indicate absolute changes in LRCC greater than 5%: box for local quadrant LRCC, and line for interquadrant (interhemispheric) LRCC. Thin box (e. g. spoken group’s long-delay right frontal gamma LRCC) indicates a decrease of greater than 5%.

Discussion • Music condition had increased frontal coherence whereas spoken condition had no significant change • Music group had stronger temporal synchronization in frontal areas

Discussion • Lack of coherence in spoken condition may be due to form of measure • Spoken learning involves more focal changes • Musical learning shows more topographical broader network synchronization

Discussion • Performance effect “nullified” • Transfer appropriate processing theory – Subjects asked to recall material in different way that it was encoded • Physiological results not due to differences in performance • Physiological results not due to different sensory processing (music vs. spoken stimuli) – Data for LRCC measured with recalled word compared to the same word not recalled in previous trial

Discussion • How does music effect synchronization then? – Early attentional mechanism • Selective attention associated with greater coherence with multiple spatial skills – Music is known to form expectancy, listeners can predict musical aspects, this could increase coherence – Studies suggest that music related processing involves more widely distributed subcortical and cortical networks

What do I think? • Uuuuuummmmm? ? ? • I don’t know enough about the interpretations of EEG to really be able to criticize a whole lot… • But like they said, use more subjects • They could try testing performance by having the words sung back and see if it makes a difference on performance • I don’t understand how you can measure a not recalled word

BUT MOST IMPORTANTLY….

– widely distributed z, t, F =

- Slides: 27