Murder Mens rea Mens rea The mens rea

- Slides: 26

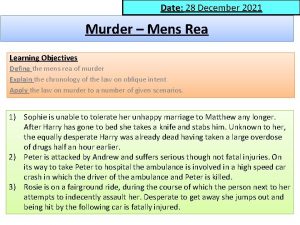

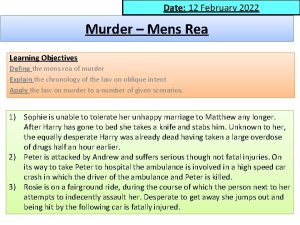

Murder Mens rea

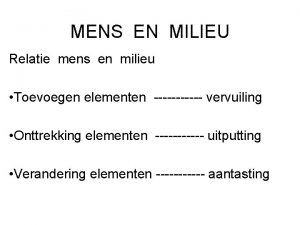

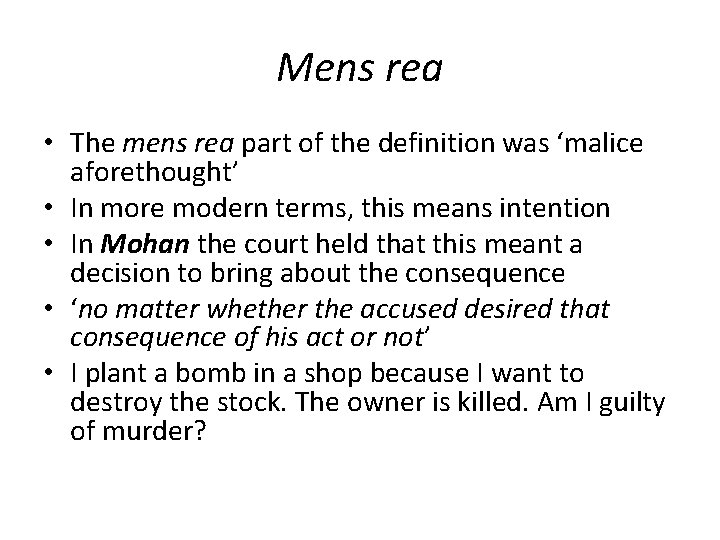

Mens rea • The mens rea part of the definition was ‘malice aforethought’ • In more modern terms, this means intention • In Mohan the court held that this meant a decision to bring about the consequence • ‘no matter whether the accused desired that consequence of his act or not’ • I plant a bomb in a shop because I want to destroy the stock. The owner is killed. Am I guilty of murder?

Malice no longer needed – Gray (1965) Kill a suffering child with fatal overdose. Killing can take place due to love or compassion.

The mens rea of an unlawful killing is an intention to kill or cause grievous bodily harm. If a defendant who kills has either of those intentions then they are guilty of murder. This was established in Vickers (1957) and confirmed by house of Lords in Cunningham (1982).

Direct and oblique intent • There are two types of intent • Direct – where the consequences are desired, the main aim or purpose of D’s act • Oblique (indirect) – where the consequences are not desired but are virtually certain to occur • In the example, much will depend on whether I knew the owner was there • If I did then I am guilty as even though I did not desire his death I knew it was virtually certain

Oblique intent: Foresight of consequences • The law has developed over the years • In DPP v Smith the House of Lords held that the mens rea for murder is intention to kill or cause grievous bodily harm • Grievous bodily harm was described in Smith as ‘really serious harm’ • It has since been held that the word ‘really’ is unnecessary • For oblique intention the starting point is the Criminal Justice Act 1967

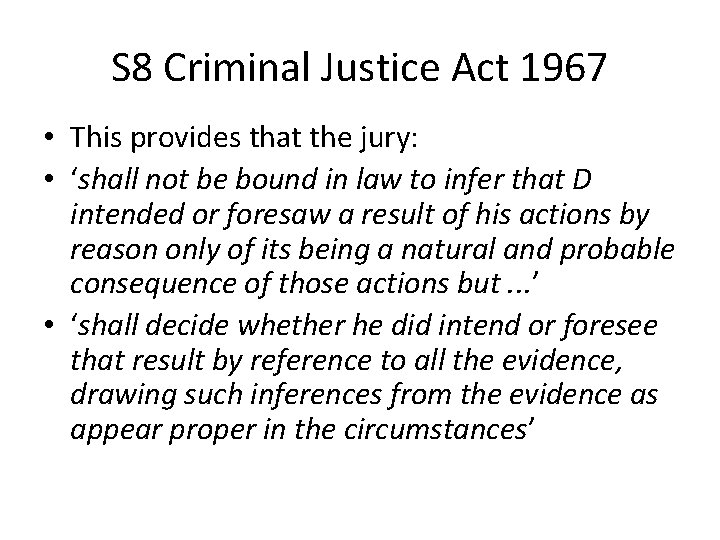

S 8 Criminal Justice Act 1967 • This provides that the jury: • ‘shall not be bound in law to infer that D intended or foresaw a result of his actions by reason only of its being a natural and probable consequence of those actions but. . . ’ • ‘shall decide whether he did intend or foresee that result by reference to all the evidence, drawing such inferences from the evidence as appear proper in the circumstances’

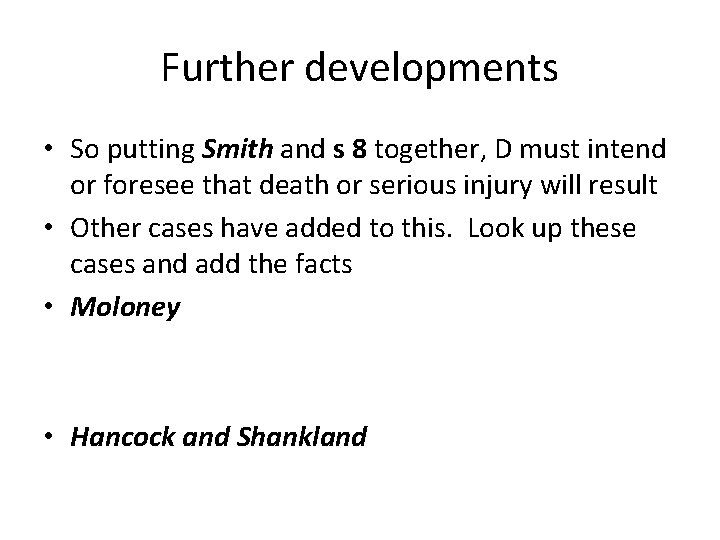

Further developments • So putting Smith and s 8 together, D must intend or foresee that death or serious injury will result • Other cases have added to this. Look up these cases and add the facts • Moloney • Hancock and Shankland

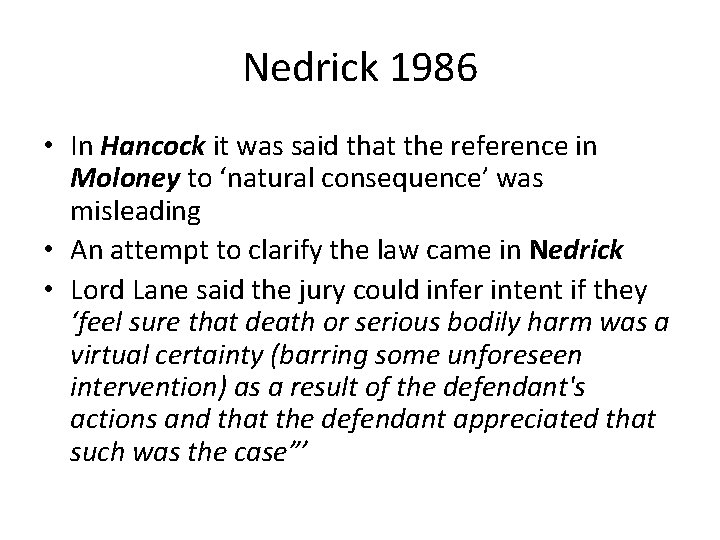

Nedrick 1986 • In Hancock it was said that the reference in Moloney to ‘natural consequence’ was misleading • An attempt to clarify the law came in Nedrick • Lord Lane said the jury could infer intent if they ‘feel sure that death or serious bodily harm was a virtual certainty (barring some unforeseen intervention) as a result of the defendant's actions and that the defendant appreciated that such was the case”’

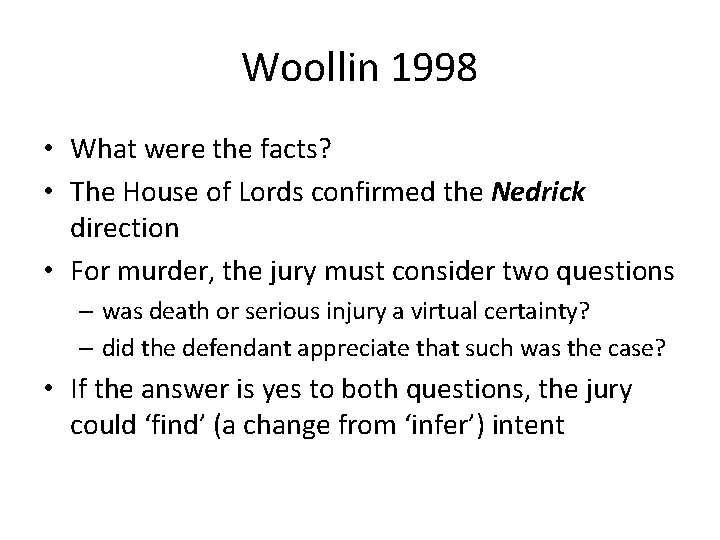

Woollin 1998 • What were the facts? • The House of Lords confirmed the Nedrick direction • For murder, the jury must consider two questions – was death or serious injury a virtual certainty? – did the defendant appreciate that such was the case? • If the answer is yes to both questions, the jury could ‘find’ (a change from ‘infer’) intent

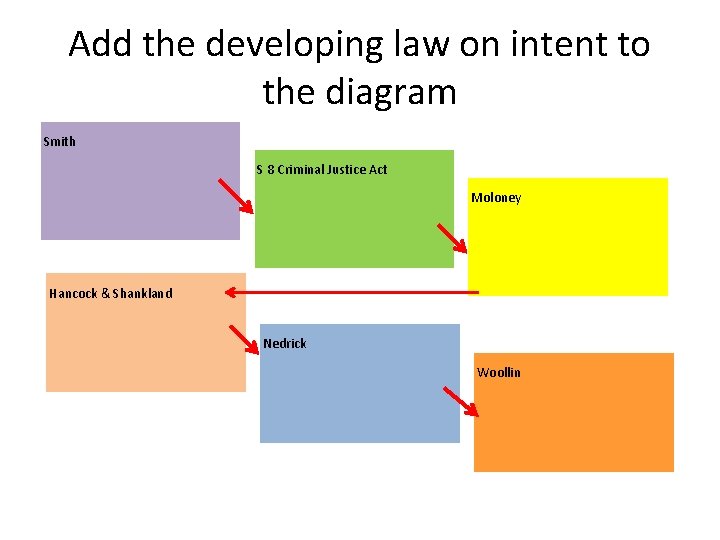

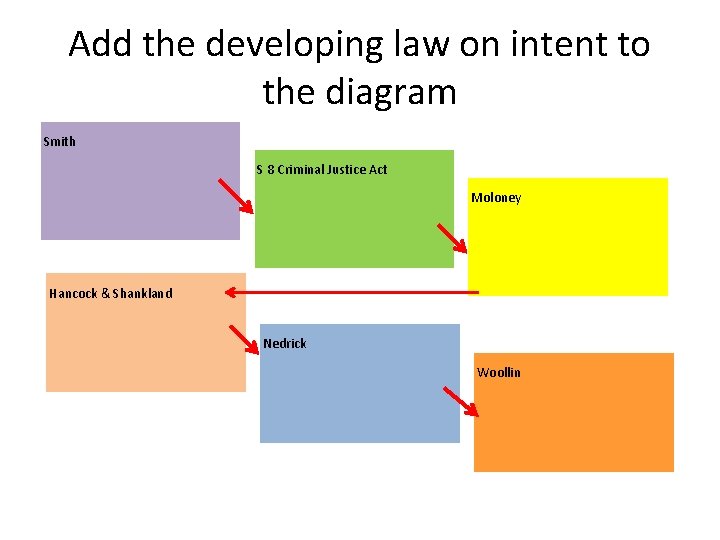

Add the developing law on intent to the diagram Smith S 8 Criminal Justice Act Moloney Hancock & Shankland Nedrick Woollin

Proof or evidence? • The test was followed in Matthews and Alleyne • What were the facts? • The Court of Appeal said that foresight of death as a virtual certainty does not automatically prove intent, it is merely evidence of intent for the jury to consider

Moloney (1985) – mere foresight of death or serious injury was not in itself intent, but could be evidence from which a jury might infer intention Hancock and Shankland (1986) – the greater the probability of a consequence, the more likely that it was foreseen; If the consequence was foreseen, the greater the probability is that it was also intended; Juries must be reminded that the decision is theirs to be reached upon a consideration of all the evidence

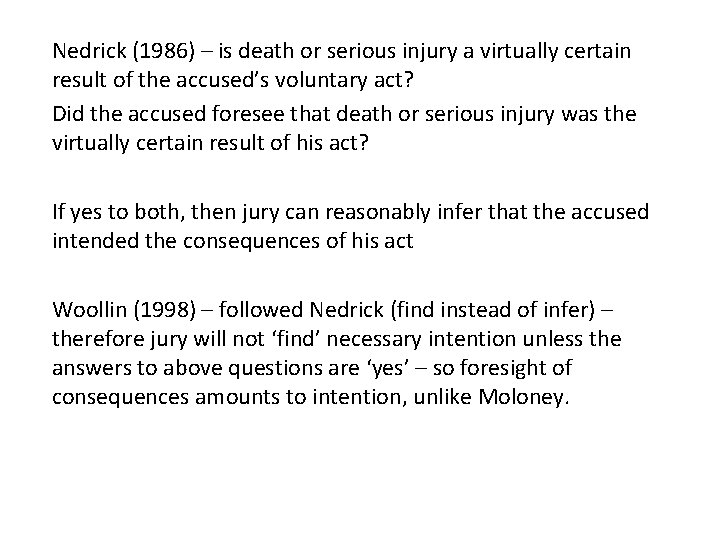

Nedrick (1986) – is death or serious injury a virtually certain result of the accused’s voluntary act? Did the accused foresee that death or serious injury was the virtually certain result of his act? If yes to both, then jury can reasonably infer that the accused intended the consequences of his act Woollin (1998) – followed Nedrick (find instead of infer) – therefore jury will not ‘find’ necessary intention unless the answers to above questions are ‘yes’ – so foresight of consequences amounts to intention, unlike Moloney.

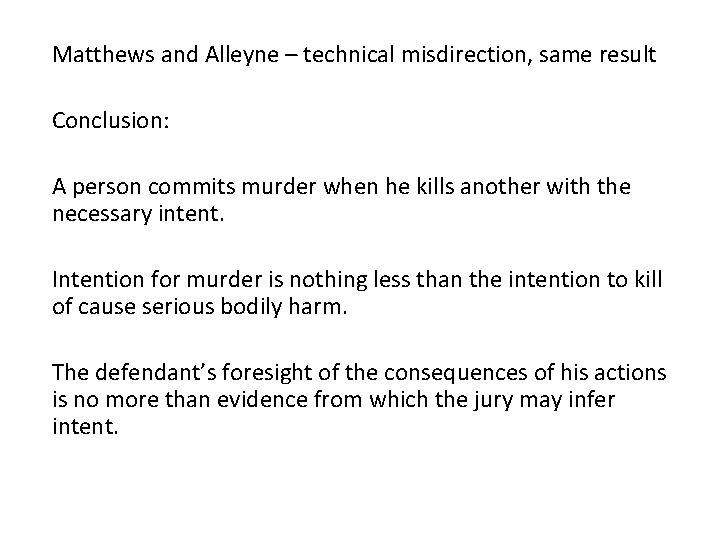

Matthews and Alleyne – technical misdirection, same result Conclusion: A person commits murder when he kills another with the necessary intent. Intention for murder is nothing less than the intention to kill of cause serious bodily harm. The defendant’s foresight of the consequences of his actions is no more than evidence from which the jury may infer intent.

Coincidence of AR and MR • The actus reus and mens rea must coincide • The actus reus may be treated as continuing • This was seen in Fagan when he argued that the mens rea (intentionally refusing to move) did not coincide with the actus reus (driving onto the policeman’s foot) • A similar point can be seen in Thabo Meli • Here the actus reus was seen as a series of acts

Exam tip For a person to be liable each and every part of a crime has to be proved beyond reasonable doubt Learn the definitions so you can identify both the actus reus and the mens rea of each offence when answering a problem question Then take each part in turn and apply the law to the given facts Concentrate on the areas which are most relevant to the facts of the actual scenario Use the most recent cases on the law in support For an essay question you will need the developing law too, in order to evaluate it

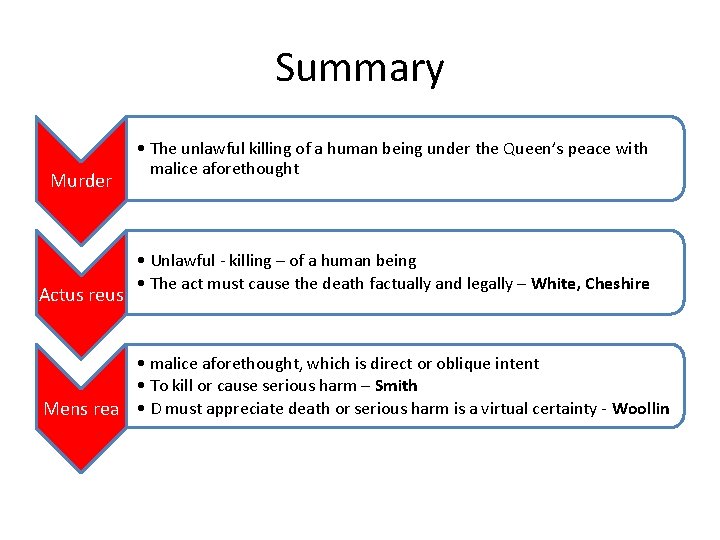

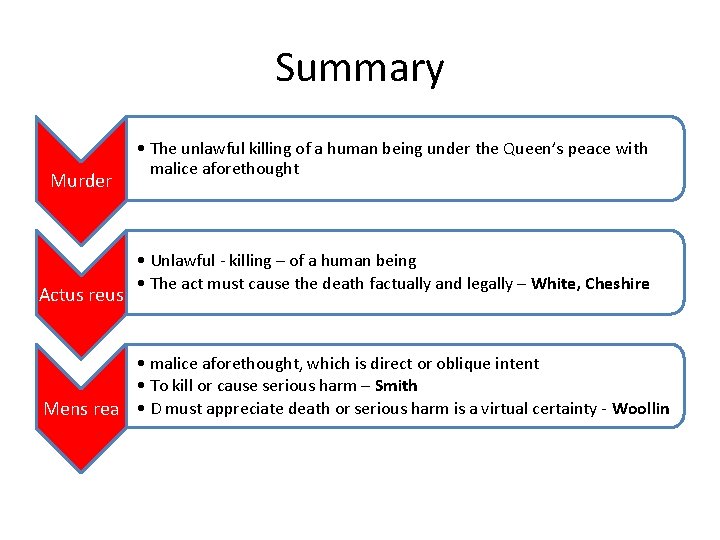

Summary Murder Actus reus • The unlawful killing of a human being under the Queen’s peace with malice aforethought • Unlawful - killing – of a human being • The act must cause the death factually and legally – White, Cheshire • malice aforethought, which is direct or oblique intent • To kill or cause serious harm – Smith Mens rea • D must appreciate death or serious harm is a virtual certainty - Woollin

Mens rea The mens rea of murder is malice aforethought. This means that the defendant must intend either to kill or to cause grievous bodily harm. The phrase is misleading, since in this context ‘malice’ does not mean ill will, and premeditation is not necessary. The defendant may have direct or indirect intention.

Evaluation (1) Lack of cohesion Murder is a common-law offence developed through decisions in many cases over long periods of time. These cases have in turn led to uncertainty and ambiguities, which required further cases to settle. Critics argue that it is essential to have a clear definition of murder, as it is the most serious of criminal offences.

Evaluation (2) Problems with mens rea: intention Cases like Hyam, Moloney, Nedrick and Woollin highlight the difficulties that the courts have faced in establishing the meaning of intention, and even today there is still no clear definition. This means juries may make different decisions in cases with similar facts.

Evaluation (3) Problems with mens rea: intention to cause GBH The mens rea of murder can be satisfied when the defendant intends only to cause GBH. This means that a defendant could be convicted of murder when he or she had no intention of causing death or had not even considered the possibility that it may occur.

Evaluation (4) Life sentence The mandatory life sentence for murder has been criticised, as it does not allow judges the flexibility to pass sentences appropriate to the circumstances of the case.

Reform (1) The Law Commission has proposed that the ambiguities surrounding the law of murder should be resolved through legislation, namely a new Homicide Act. This would, it hopes, achieve the certainty that has been lacking in this area for so long. The new Act would encompass all of the elements of homicide – murder, voluntary manslaughter and involuntary manslaughter. The Law Commission suggests that the offences should be defined according to a ‘ladder principle’ or hierarchy, which reflects the seriousness of the various offences.

Reform (2) Murder would be divided into ‘first-degree’ and ‘second-degree’ categories: • First-degree murder would apply to the defendant who intended to kill, and he or she would receive the mandatory life sentence. • Second-degree murder would carry a discretionary life sentence and would apply to defendants who: - killed while intending to commit serious harm - were ‘recklessly indifferent’ to causing death - rely on provocation, diminished responsibility or duress The new Act should also include a clear definition of the mens rea required for murder – particularly regarding intention.

Reform (3) It has been suggested that the compulsory nature of the mandatory life sentence should be changed so that the maximum sentence remains life imprisonment but judges are free to sentence according to the circumstances of each case, rather than being restrained by a mandatory sentence.

Actus reus and mens rea

Actus reus and mens rea Mens rea adalah

Mens rea adalah Mens rea

Mens rea Mens rea ελληνικα

Mens rea ελληνικα Battery actus reus

Battery actus reus Strict liability tort

Strict liability tort Actus reus and mens rea

Actus reus and mens rea Actus reus and mens rea

Actus reus and mens rea Mens rea

Mens rea Reamens

Reamens Murder mystery inference activity

Murder mystery inference activity The murder of emmitt till date

The murder of emmitt till date Focus

Focus Macbeth dagger soliloquy

Macbeth dagger soliloquy Pasta passion and pistols characters

Pasta passion and pistols characters Murder mystery assignment

Murder mystery assignment Murder mystery vocabulary

Murder mystery vocabulary The raven text

The raven text Murder by hiv

Murder by hiv Caesar act

Caesar act Julie wills murder

Julie wills murder Steven benson murder

Steven benson murder Murder and a meal lab

Murder and a meal lab Abortion is murder

Abortion is murder Cryptography murder mystery answers

Cryptography murder mystery answers Murder drones b

Murder drones b Zechariah stevenson sentenced

Zechariah stevenson sentenced