MST Topological Sort and Disjoint Sets 15 211

![All the code class Union. Find { int[] u; Union. Find(int n) { u All the code class Union. Find { int[] u; Union. Find(int n) { u](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bb4d2897b099c698352c70976d1a547/image-49.jpg)

![The Union. Find class Union. Find { int[] u; Union. Find(int n) { u The Union. Find class Union. Find { int[] u; Union. Find(int n) { u](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bb4d2897b099c698352c70976d1a547/image-50.jpg)

![Iterative find int find(int i) { int j, root; for (j = i; u[j] Iterative find int find(int i) { int j, root; for (j = i; u[j]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bb4d2897b099c698352c70976d1a547/image-51.jpg)

- Slides: 58

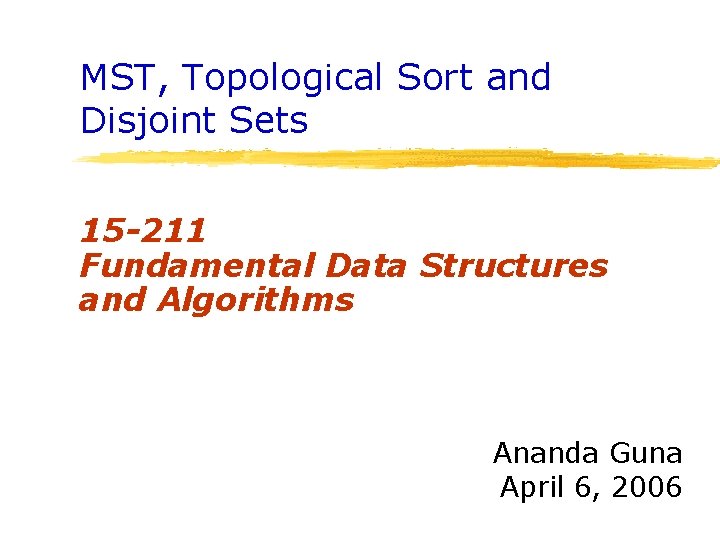

MST, Topological Sort and Disjoint Sets 15 -211 Fundamental Data Structures and Algorithms Ananda Guna April 6, 2006

In this lecture § Prim’s revisited § Kruskal’s algorithm § Topological Sorting § Union Find algorithms ØDisjoint Sets ØAnalysis

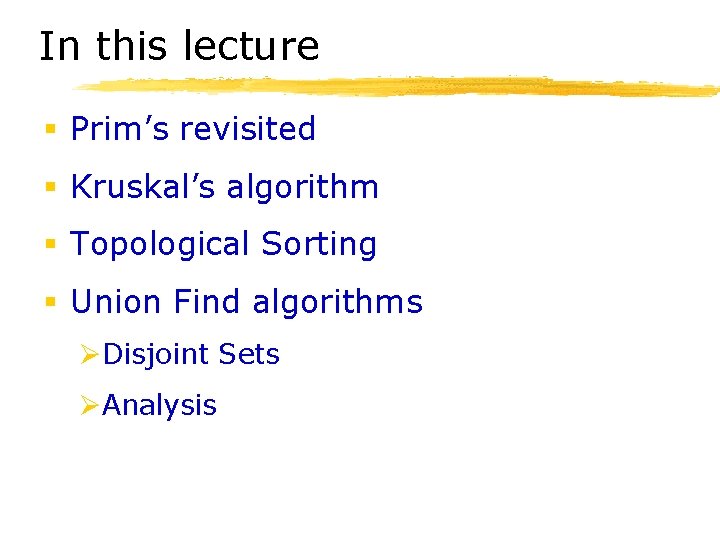

Prim’s Algorithm • Algorithm is based on the idea of two sets • S = vertices in the current MST • V-S = vertices not in the current MST • Find the minimum edge (u, v) such that u is in S and v is in V-S • Add the edge to MST and node v to S • At the end algorithm guarantees that we have constructed a MST • Note: MST is not unique

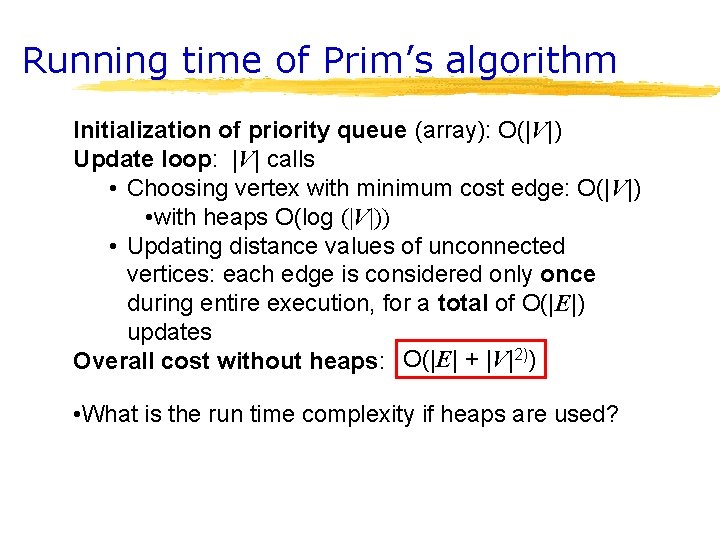

Prim’s Algorithm Invariant § At each step, we add the edge (u, v) s. t. the weight of (u, v) is minimum among all edges where u is in the tree and v is not in the tree § Each step maintains a minimum spanning tree of the vertices that have been included thus far § When all vertices have been included, we have a MST for the graph!

Running time of Prim’s algorithm Initialization of priority queue (array): O(|V|) Update loop: |V| calls • Choosing vertex with minimum cost edge: O(|V|) • with heaps O(log (|V|)) • Updating distance values of unconnected vertices: each edge is considered only once during entire execution, for a total of O(|E|) updates Overall cost without heaps: O(|E| + |V|2)) • What is the run time complexity if heaps are used?

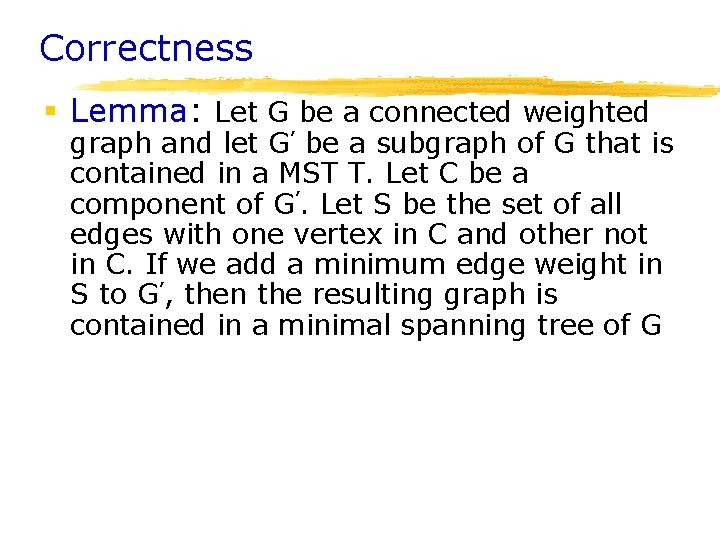

Correctness § Lemma: Let G be a connected weighted graph and let G’ be a subgraph of G that is contained in a MST T. Let C be a component of G’. Let S be the set of all edges with one vertex in C and other not in C. If we add a minimum edge weight in S to G’, then the resulting graph is contained in a minimal spanning tree of G

Correctness § Theorem: Prim’s algorithm correctly finds a minimal spanning tree § Proof: by induction show that tree constructed at each iteration is contained in a MST. Then at the termination, the tree constructed is a MST Ø Base case: tree has no edges, and therefore contained in every spanning tree Ø Inductive case: Let T be the current tree constructed using Prim’s algorithm. By inductive argument, T is contained in some MST. Ø Let (u, v) be the next edge selected by Prim’s, such that u in T and v not in T. Let G’ be T together with all vertices not in T. Then T is a component of G’ and (u, v) is a minimum weight edge with one vertex in T and one not in T. Then by lemma, when (u, v) is added to G’ , the resulting graph is also contained in a MST.

Kruskal’s Algorithm

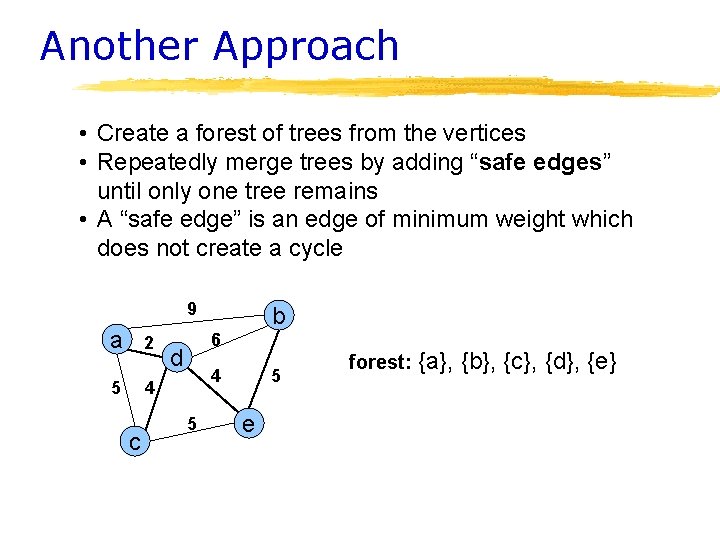

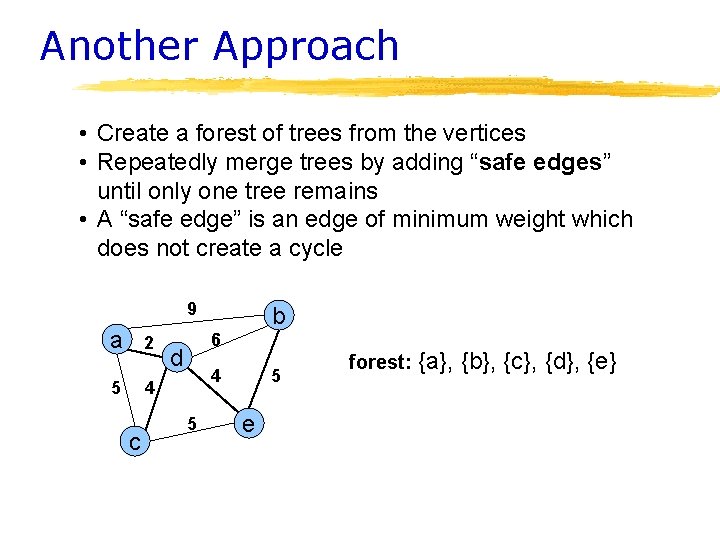

Another Approach • Create a forest of trees from the vertices • Repeatedly merge trees by adding “safe edges” until only one tree remains • A “safe edge” is an edge of minimum weight which does not create a cycle 9 a 2 5 6 d 4 4 c b 5 5 e forest: {a}, {b}, {c}, {d}, {e}

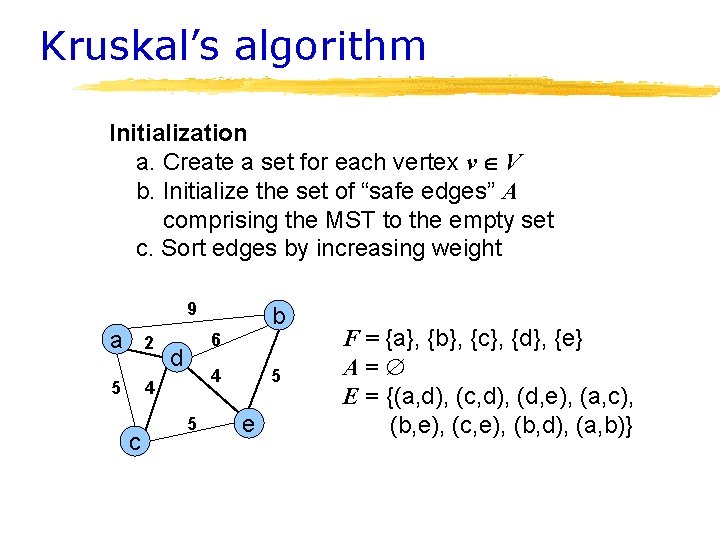

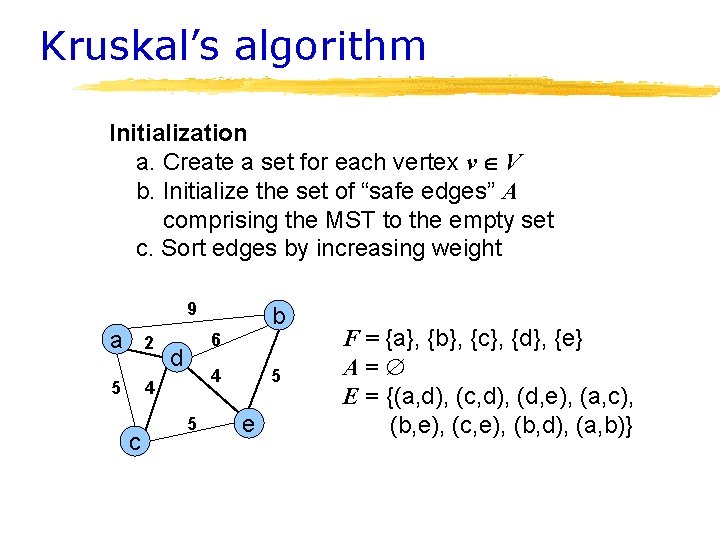

Kruskal’s algorithm Initialization a. Create a set for each vertex v V b. Initialize the set of “safe edges” A comprising the MST to the empty set c. Sort edges by increasing weight 9 a 2 5 4 c b 6 d 4 5 5 e F = {a}, {b}, {c}, {d}, {e} A= E = {(a, d), (c, d), (d, e), (a, c), (b, e), (c, e), (b, d), (a, b)}

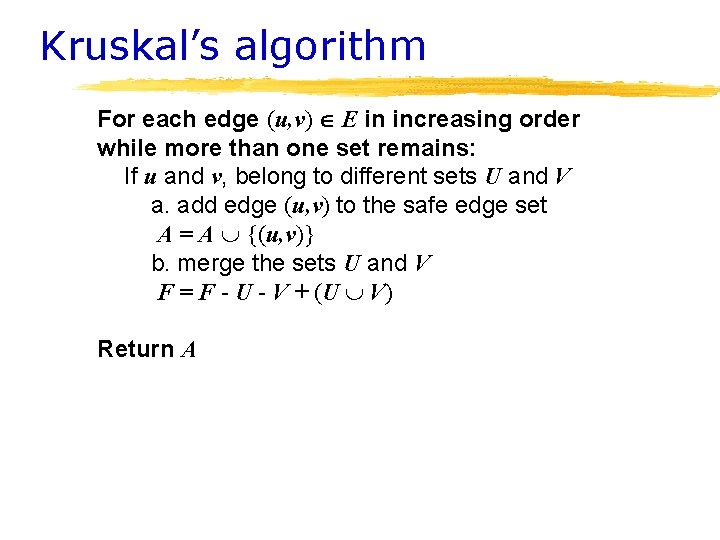

Kruskal’s algorithm For each edge (u, v) E in increasing order while more than one set remains: If u and v, belong to different sets U and V a. add edge (u, v) to the safe edge set A = A {(u, v)} b. merge the sets U and V F = F - U - V + (U V) Return A

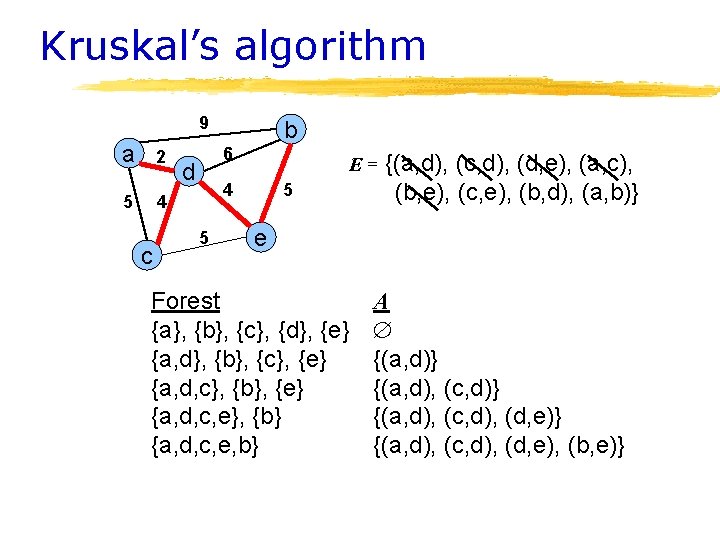

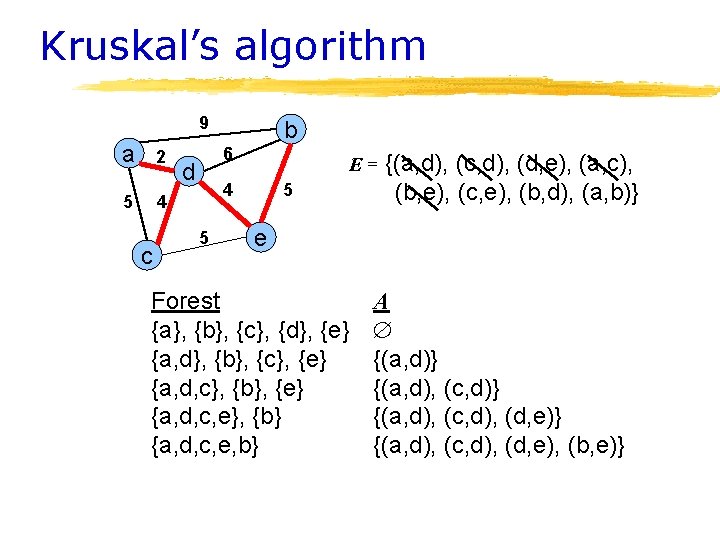

Kruskal’s algorithm 9 a 2 5 4 c b 6 d E= 4 5 5 {(a, d), (c, d), (d, e), (a, c), (b, e), (c, e), (b, d), (a, b)} e Forest {a}, {b}, {c}, {d}, {e} {a, d}, {b}, {c}, {e} {a, d, c}, {b}, {e} {a, d, c, e}, {b} {a, d, c, e, b} A {(a, d)} {(a, d), (c, d), (d, e)} {(a, d), (c, d), (d, e), (b, e)}

Kruskal’s Algorithm Summary § After each iteration, every tree in the forest is a MST of the vertices it connects § Algorithm terminates when all vertices are connected into one tree § Both Prim’s and Kruskal’s algorithms are greedy algorithms § Complexity of Kruskal’s algorithm Ø O(|E| log |E|) to sort the edges Ø O(|V|) initial sets Ø O(|V||log|V|) find and union operations § What if the edges are maintained in a PQ?

Topological Sort

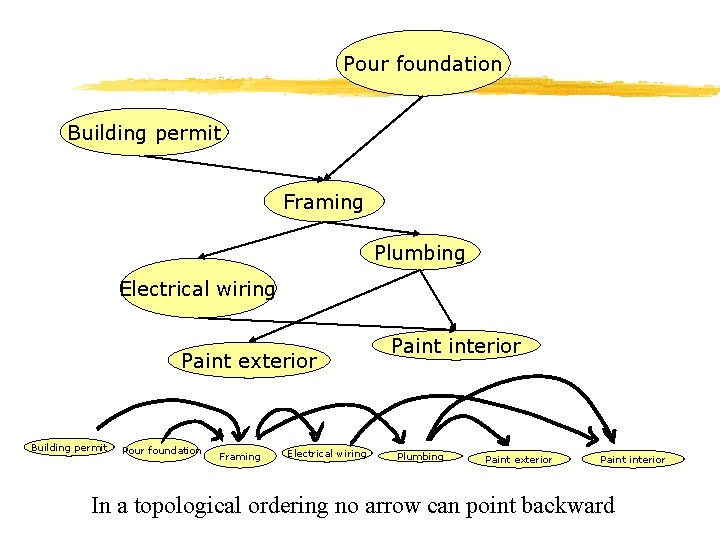

Topological sort § Definition: ØA topological sort of G=(V, E) is an ordering of all of G’s vertices v 1, v 2, …, vn such that for every edge (vi, vj) in E, i<j.

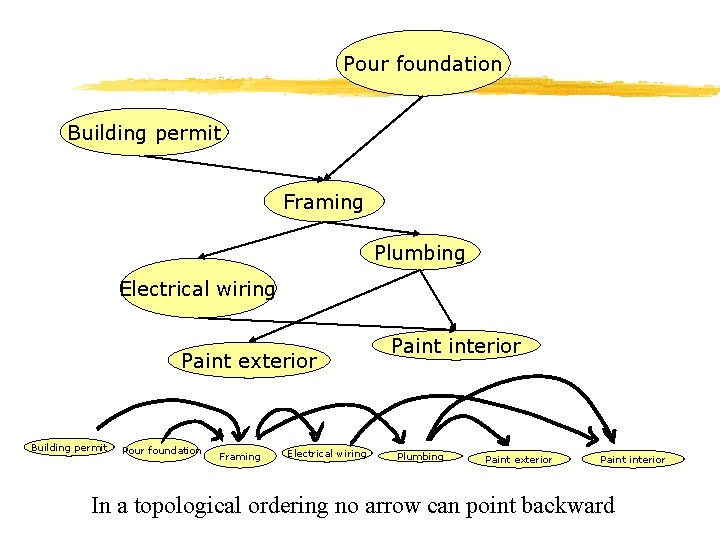

Pour foundation Building permit Framing Plumbing Electrical wiring Paint exterior Building permit Pour foundation Framing Electrical wiring Paint interior Plumbing Paint exterior Paint interior In a topological ordering no arrow can point backward

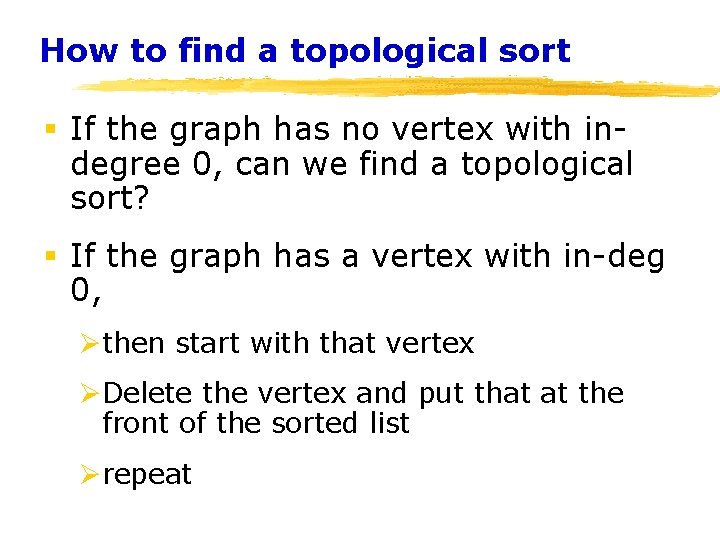

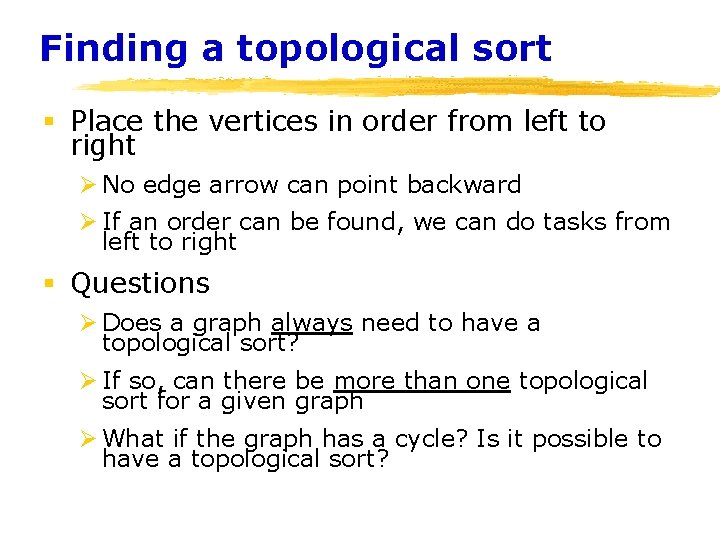

Finding a topological sort § Place the vertices in order from left to right Ø No edge arrow can point backward Ø If an order can be found, we can do tasks from left to right § Questions Ø Does a graph always need to have a topological sort? Ø If so, can there be more than one topological sort for a given graph Ø What if the graph has a cycle? Is it possible to have a topological sort?

How to find a topological sort § If the graph has no vertex with indegree 0, can we find a topological sort? § If the graph has a vertex with in-deg 0, Øthen start with that vertex ØDelete the vertex and put that at the front of the sorted list Ørepeat

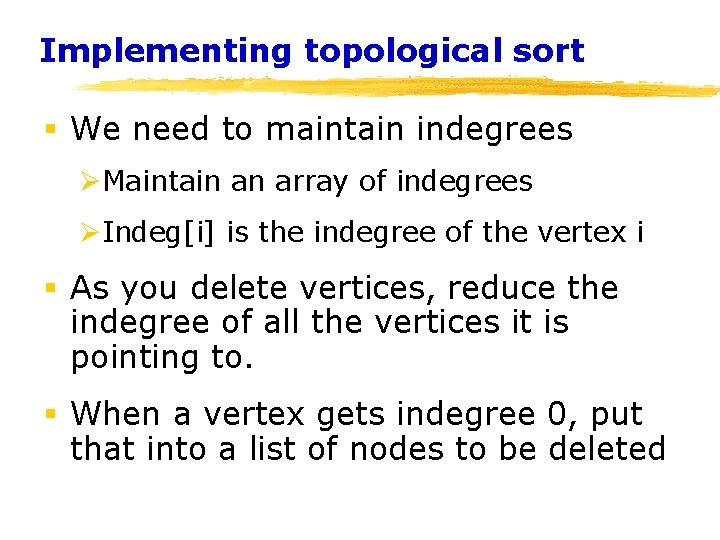

Implementing topological sort § We need to maintain indegrees ØMaintain an array of indegrees ØIndeg[i] is the indegree of the vertex i § As you delete vertices, reduce the indegree of all the vertices it is pointing to. § When a vertex gets indegree 0, put that into a list of nodes to be deleted

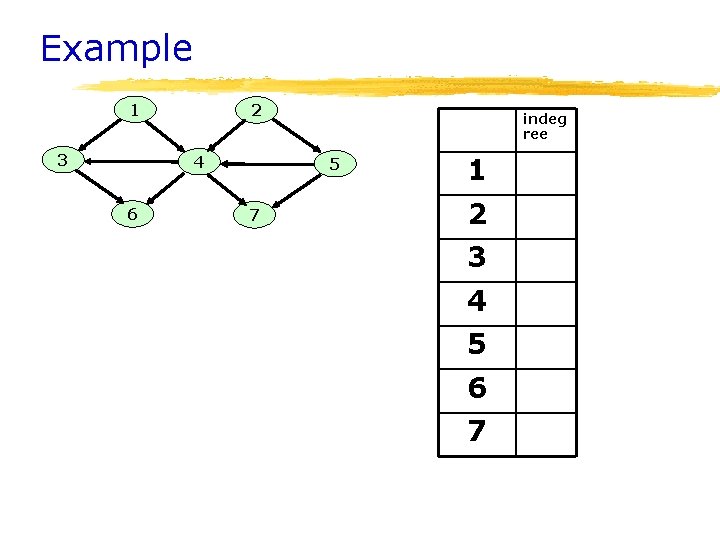

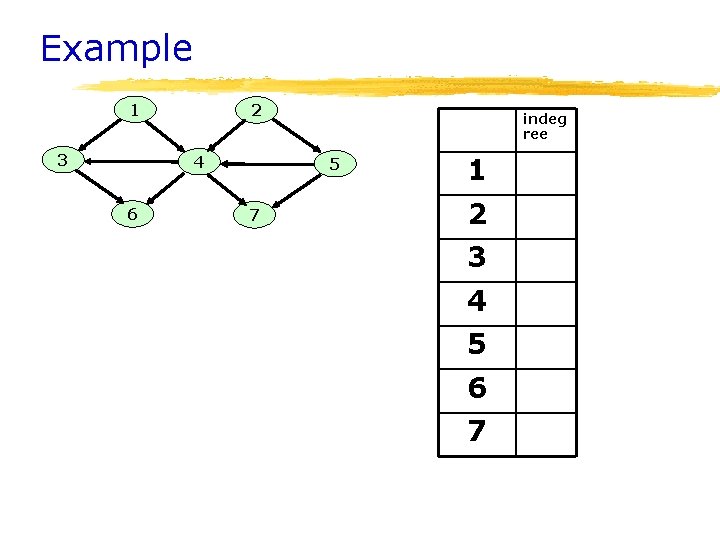

Example 1 3 2 4 6 indeg ree 5 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

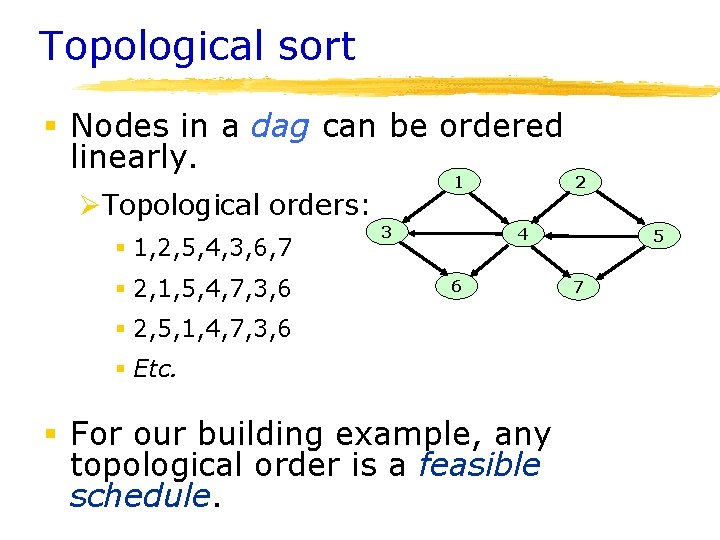

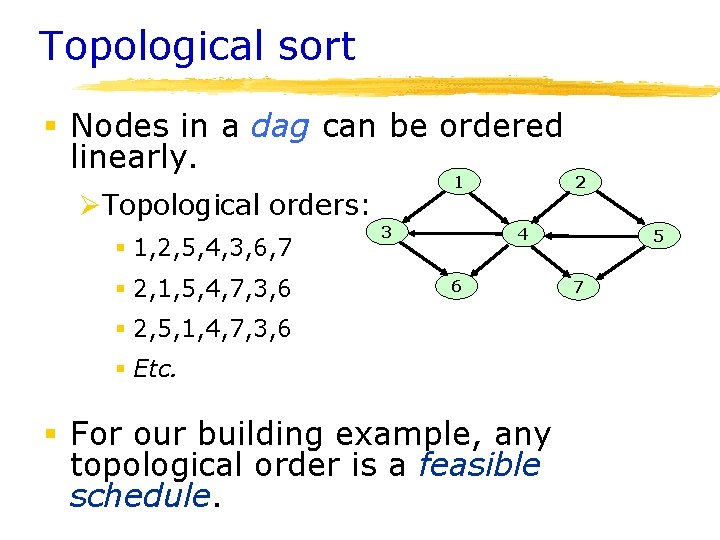

Topological sort § Nodes in a dag can be ordered linearly. 1 ØTopological orders: § 1, 2, 5, 4, 3, 6, 7 § 2, 1, 5, 4, 7, 3, 6 3 2 4 6 § 2, 5, 1, 4, 7, 3, 6 § Etc. § For our building example, any topological order is a feasible schedule. 5 7

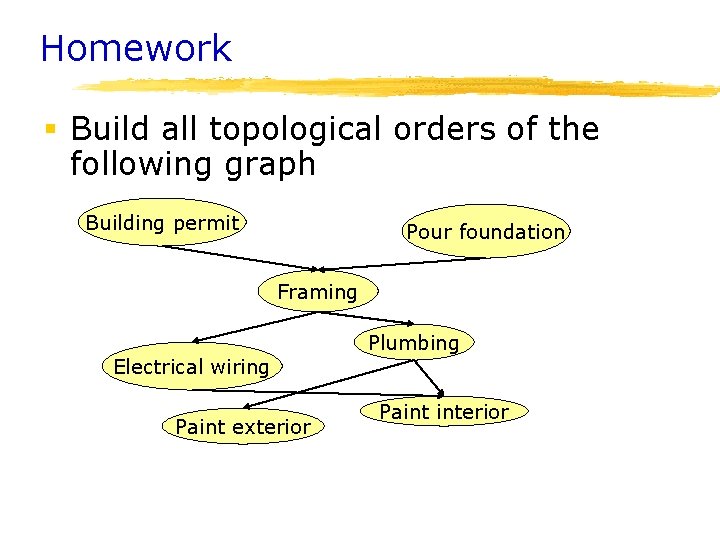

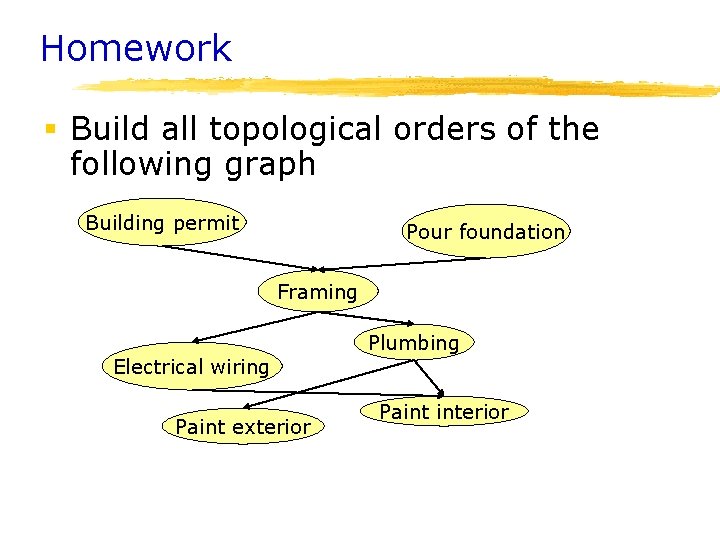

Homework § Build all topological orders of the following graph Building permit Pour foundation Framing Electrical wiring Paint exterior Plumbing Paint interior

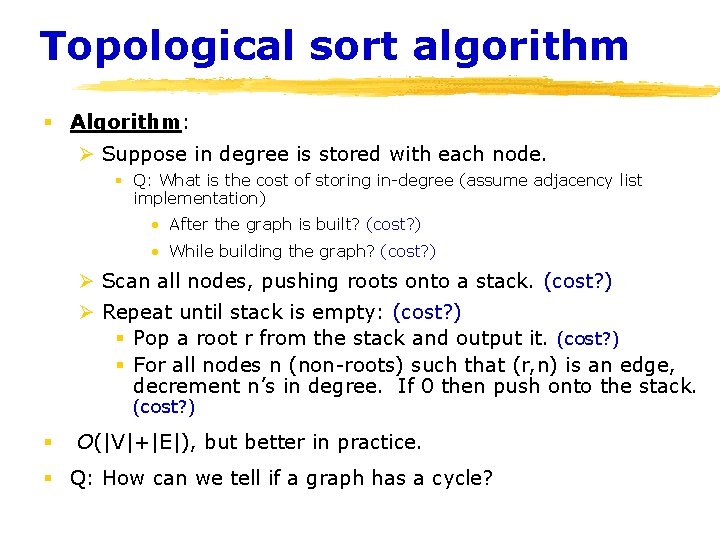

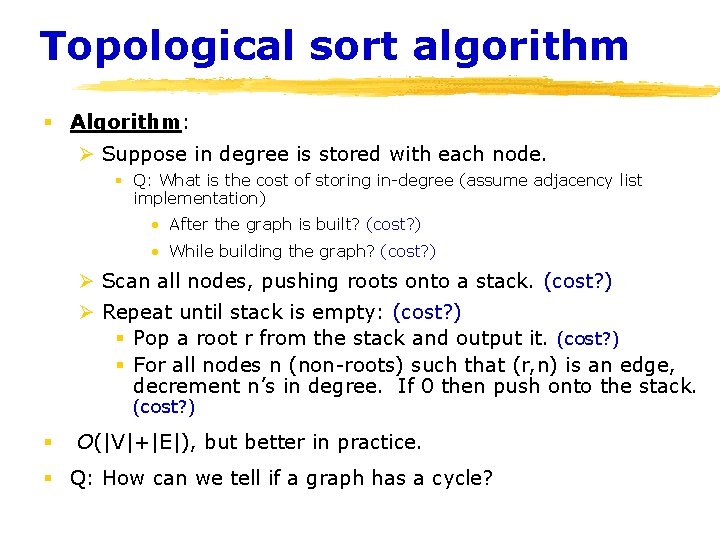

Topological sort algorithm § Algorithm: Ø Suppose in degree is stored with each node. § Q: What is the cost of storing in-degree (assume adjacency list implementation) • After the graph is built? (cost? ) • While building the graph? (cost? ) Ø Scan all nodes, pushing roots onto a stack. (cost? ) Ø Repeat until stack is empty: (cost? ) § Pop a root r from the stack and output it. (cost? ) § For all nodes n (non-roots) such that (r, n) is an edge, decrement n’s in degree. If 0 then push onto the stack. (cost? ) § O(|V|+|E|), but better in practice. § Q: How can we tell if a graph has a cycle?

Union Find

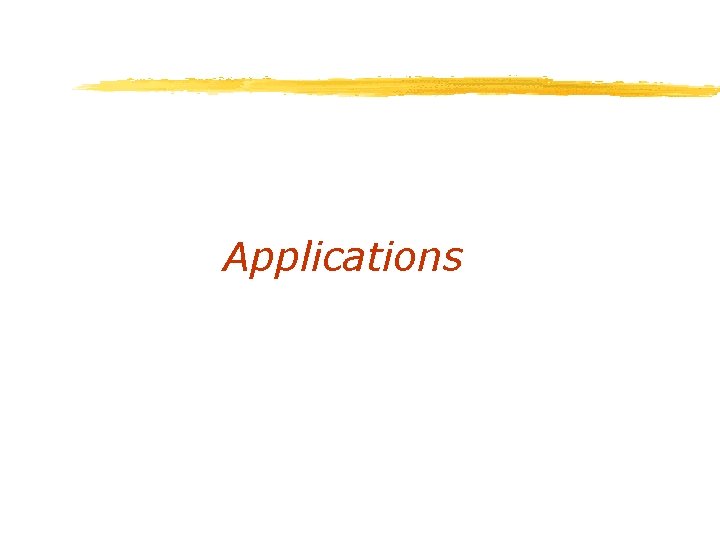

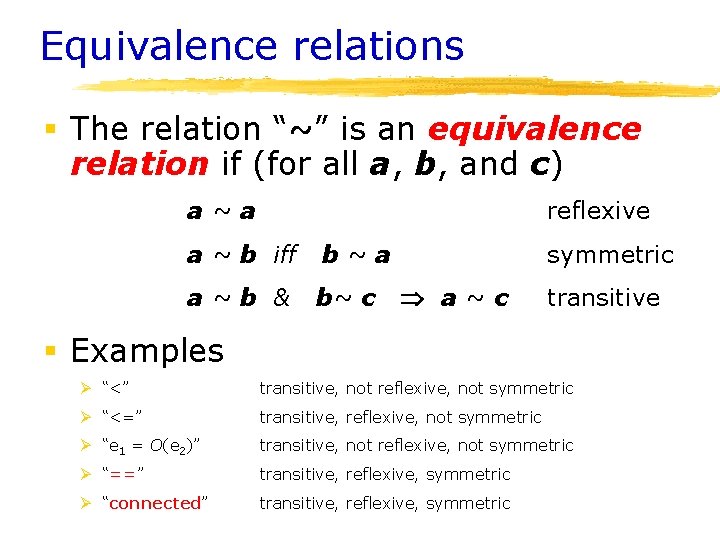

Equivalence relations § The relation “~” is an equivalence relation if (for all a, b, and c) a~a reflexive a ~ b iff b~a a~b & b~ c symmetric a~c transitive § Examples Ø “<” transitive, not reflexive, not symmetric Ø “<=” transitive, reflexive, not symmetric Ø “e 1 = O(e 2)” transitive, not reflexive, not symmetric Ø “==” transitive, reflexive, symmetric Ø “connected” transitive, reflexive, symmetric

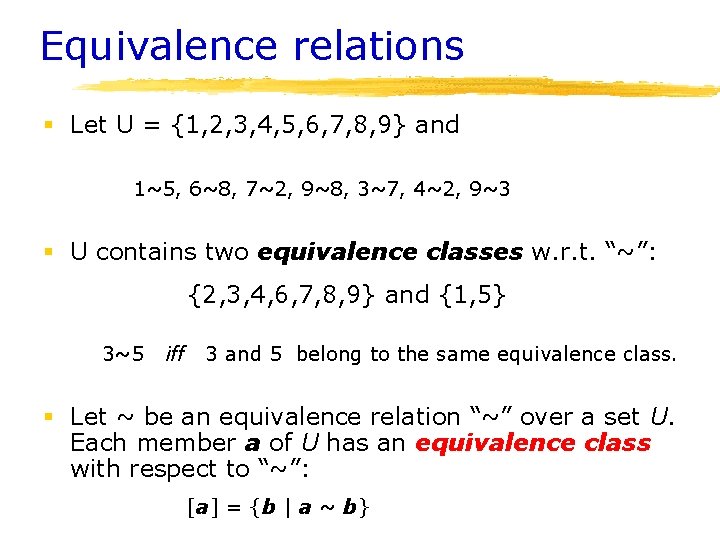

Equivalence relations § Let U = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9} and 1~5, 6~8, 7~2, 9~8, 3~7, 4~2, 9~3 § U contains two equivalence classes w. r. t. “~”: {2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9} and {1, 5} 3~5 iff 3 and 5 belong to the same equivalence class. § Let ~ be an equivalence relation “~” over a set U. Each member a of U has an equivalence class with respect to “~”: [a] = {b | a ~ b}

Equivalence relations § The set of equivalence classes are a partition of U. { {2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9}, {1, 5} } § In general Øi j implies Pi Pj={}. Ø For each a U, there is exactly one i such that a Pi. § Why study Equivalence Relations? § What problems can be solved by understanding equivalence relations? Ø Common ancestor problem Ø Maze problem

Applications

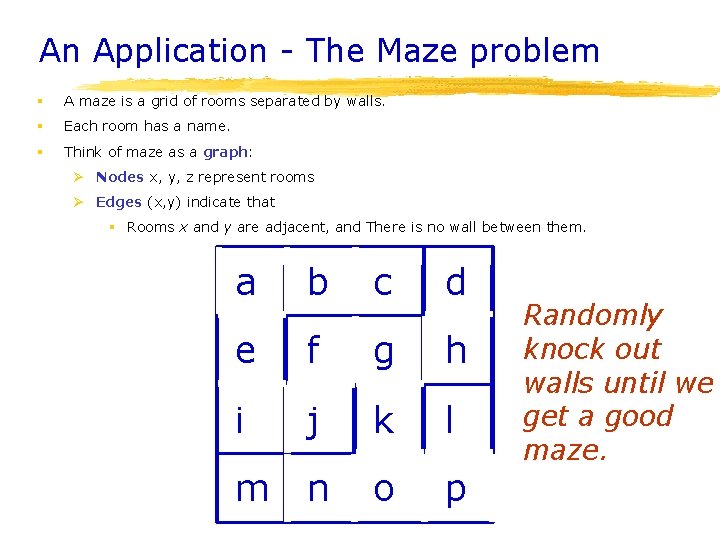

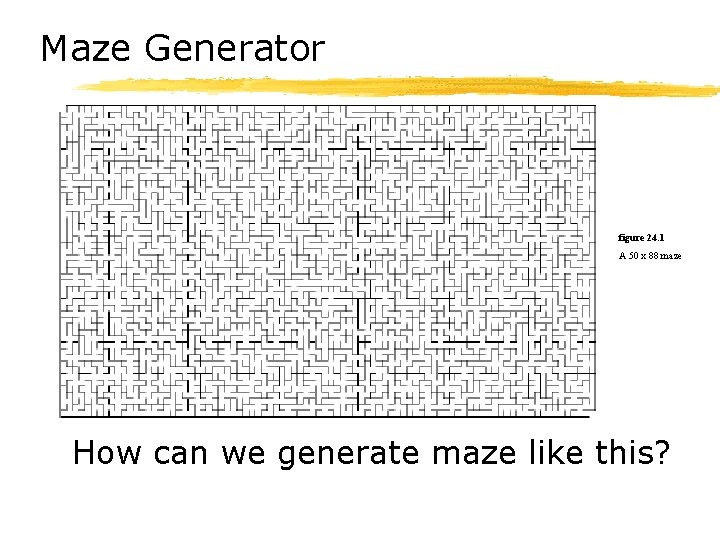

Maze Generator figure 24. 1 A 50 x 88 maze How can we generate maze like this?

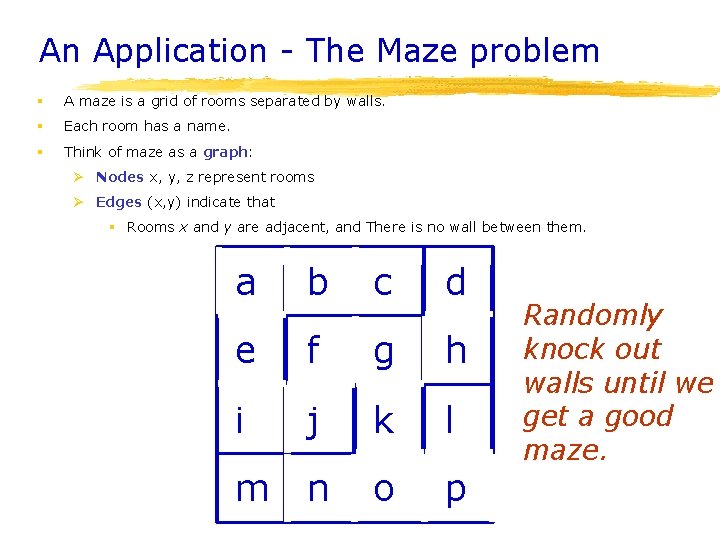

An Application - The Maze problem § A maze is a grid of rooms separated by walls. § Each room has a name. § Think of maze as a graph: Ø Nodes x, y, z represent rooms Ø Edges (x, y) indicate that § Rooms x and y are adjacent, and There is no wall between them. a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Randomly knock out walls until we get a good maze.

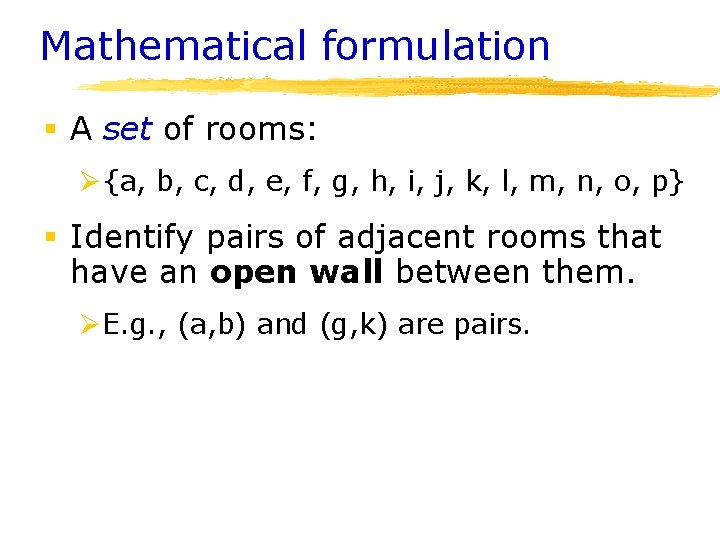

Mathematical formulation § A set of rooms: Ø{a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, o, p} § Identify pairs of adjacent rooms that have an open wall between them. ØE. g. , (a, b) and (g, k) are pairs.

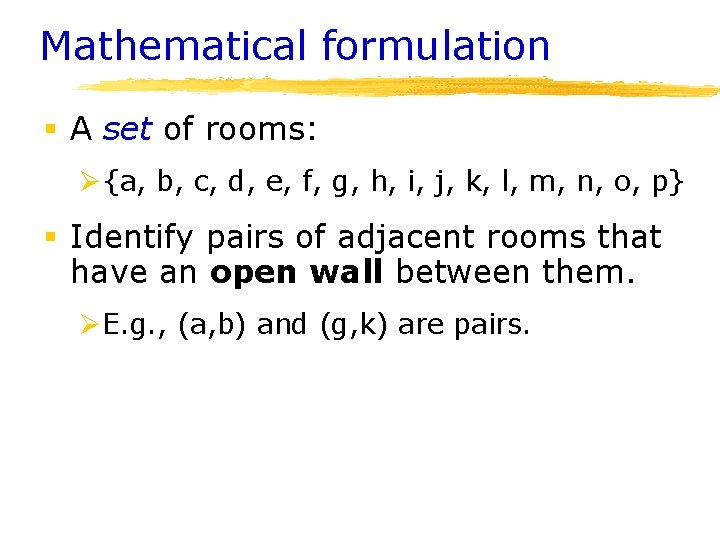

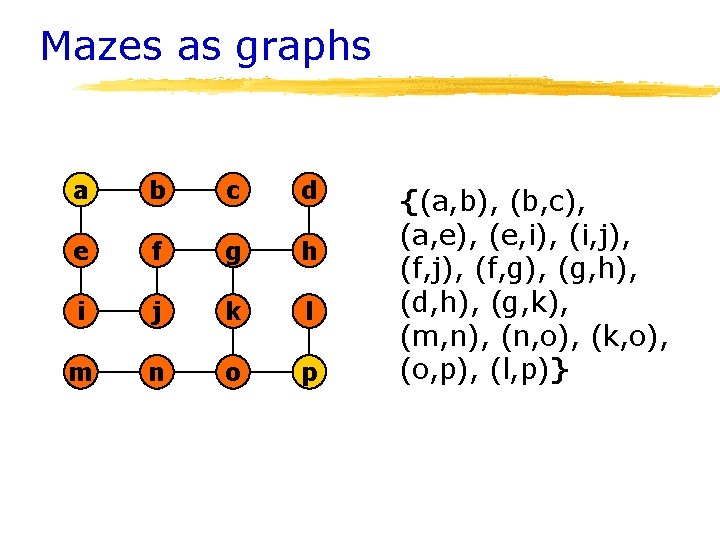

Mazes as graphs a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p {(a, b), (b, c), (a, e), (e, i), (i, j), (f, g), (g, h), (d, h), (g, k), (m, n), (n, o), (k, o), (o, p), (l, p)}

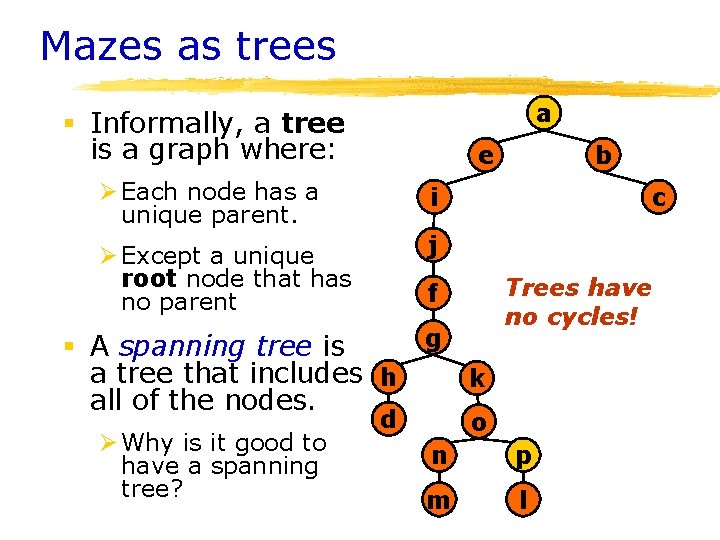

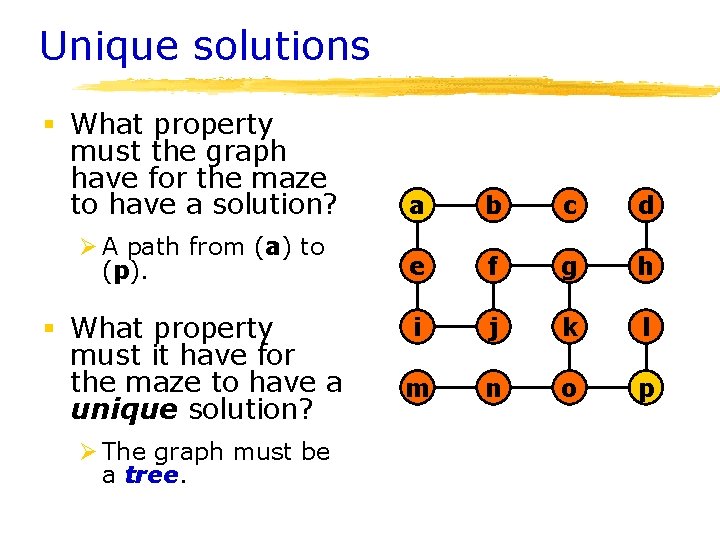

Unique solutions § What property must the graph have for the maze to have a solution? Ø A path from (a) to (p). § What property must it have for the maze to have a unique solution? Ø The graph must be a tree. a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p

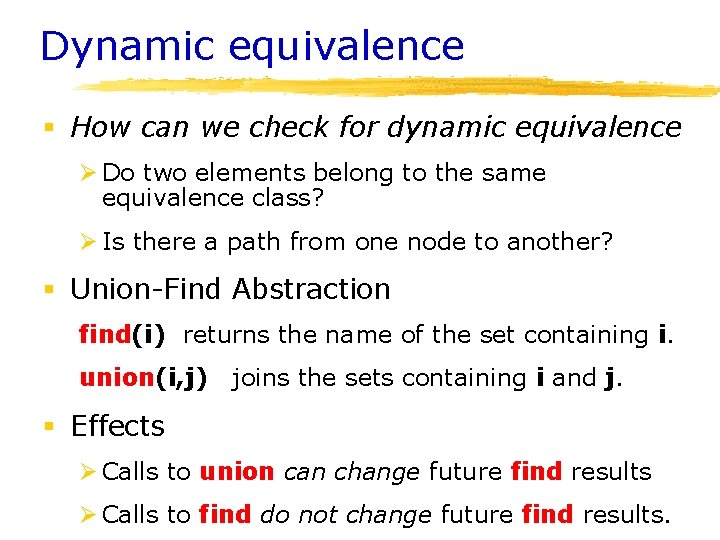

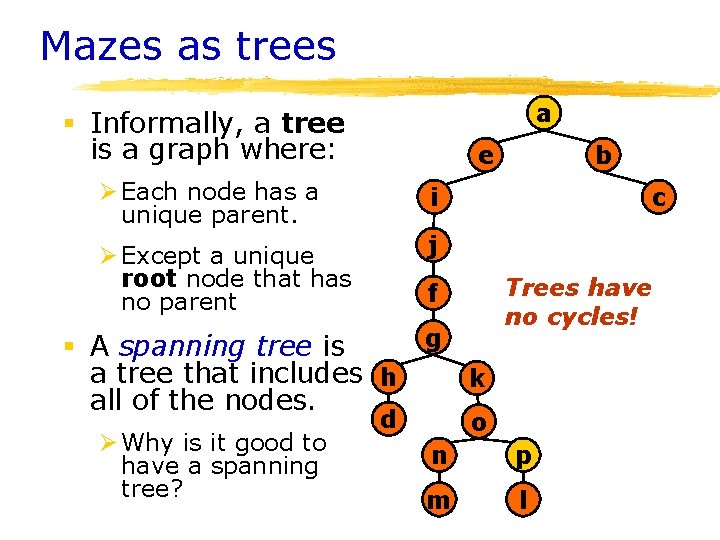

Mazes as trees a § Informally, a tree is a graph where: e Ø Each node has a unique parent. i Ø Except a unique root node that has no parent j c f g § A spanning tree is a tree that includes h k all of the nodes. Ø Why is it good to have a spanning tree? d b Trees have no cycles! o n p m l

Dynamic equivalence § How can we check for dynamic equivalence Ø Do two elements belong to the same equivalence class? Ø Is there a path from one node to another? § Union-Find Abstraction find(i) returns the name of the set containing i. union(i, j) joins the sets containing i and j. § Effects Ø Calls to union can change future find results Ø Calls to find do not change future find results.

The Union-Find Interface § Represent elements as ints Ø Let 0 i N stand for ei {e 0, … , e. N-1} § Find identifies the set containing i. int find(int i) § Equivalence testing find(i) == find(j) § Union called for an effect void union(int i, int j) Ø Affects results of future calls to find

Understanding Union-Find

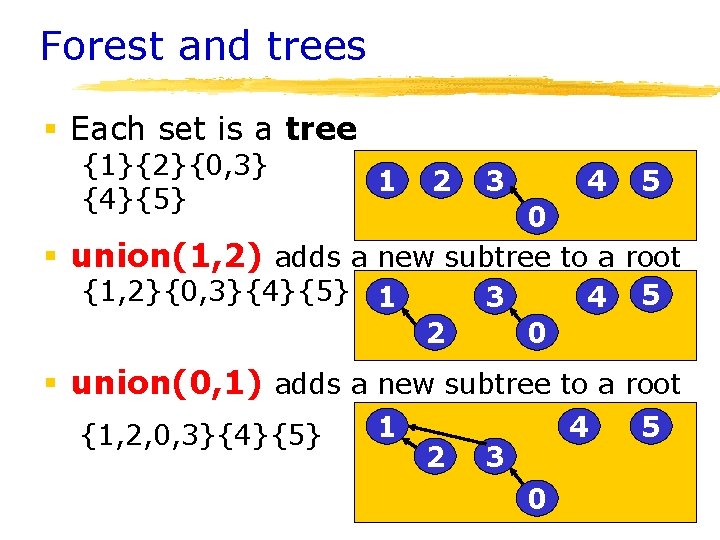

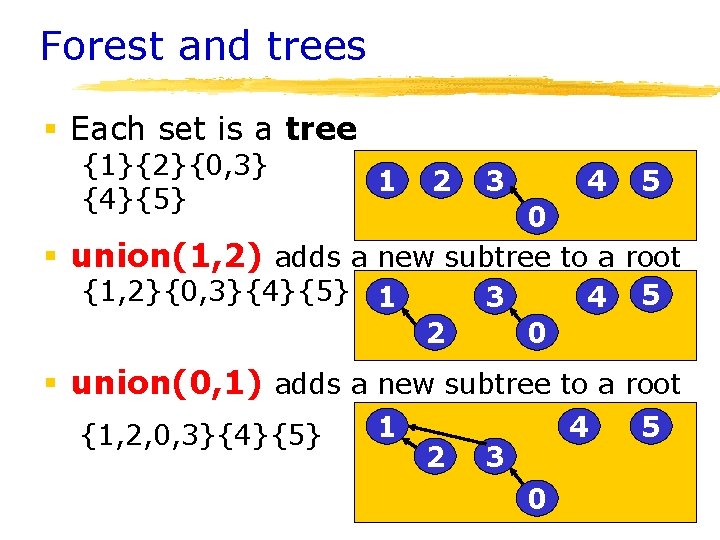

Forest and trees § Each set is a tree {1}{2}{0, 3} {4}{5} 1 2 3 4 5 0 § union(1, 2) adds a new subtree to a root {1, 2}{0, 3}{4}{5} 1 3 4 5 2 0 § union(0, 1) adds a new subtree to a root {1, 2, 0, 3}{4}{5} 1 2 4 3 0 5

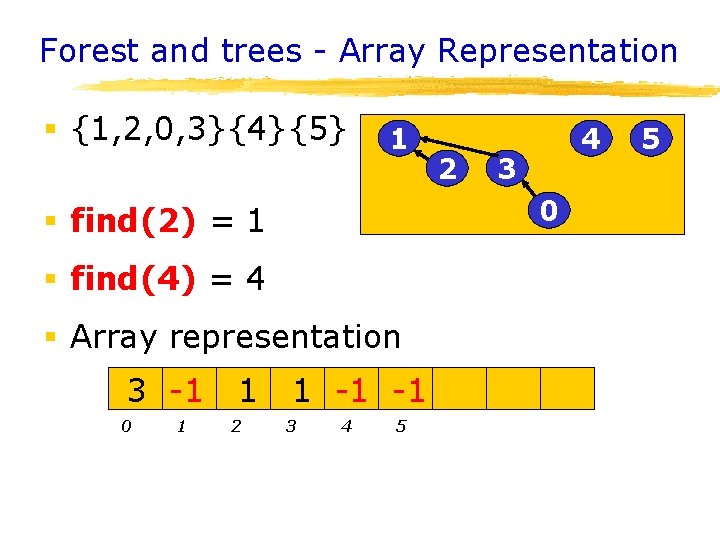

Forest and trees - Array Representation § {1, 2, 0, 3}{4}{5} 1 § find(4) = 4 § Array representation 0 1 1 2 3 0 § find(2) = 1 3 -1 2 4 1 -1 -1 3 4 5 5

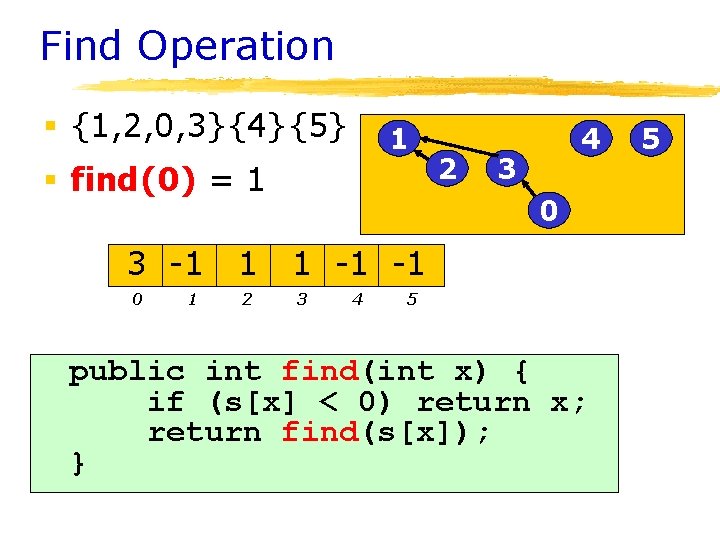

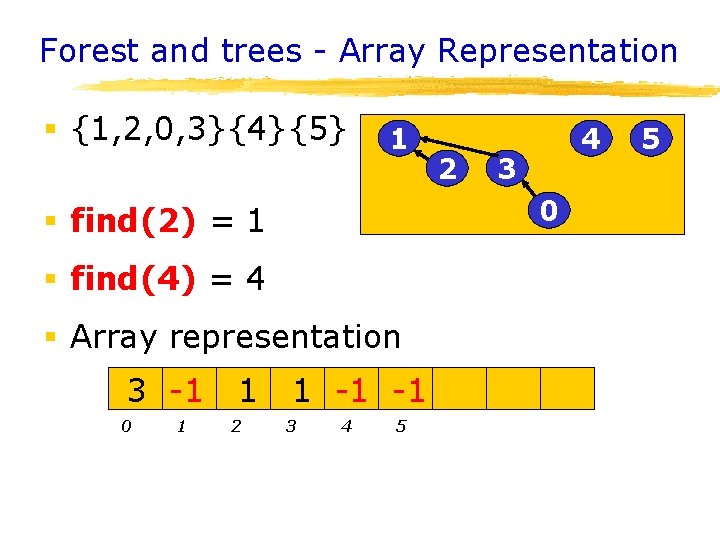

Find Operation § {1, 2, 0, 3}{4}{5} 1 § find(0) = 1 3 -1 0 1 1 2 2 4 3 0 1 -1 -1 3 4 5 public int find(int x) { if (s[x] < 0) return x; return find(s[x]); } 5

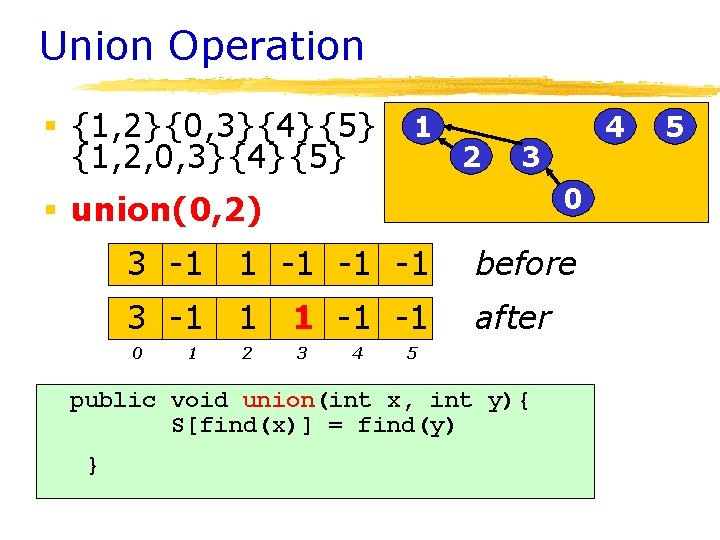

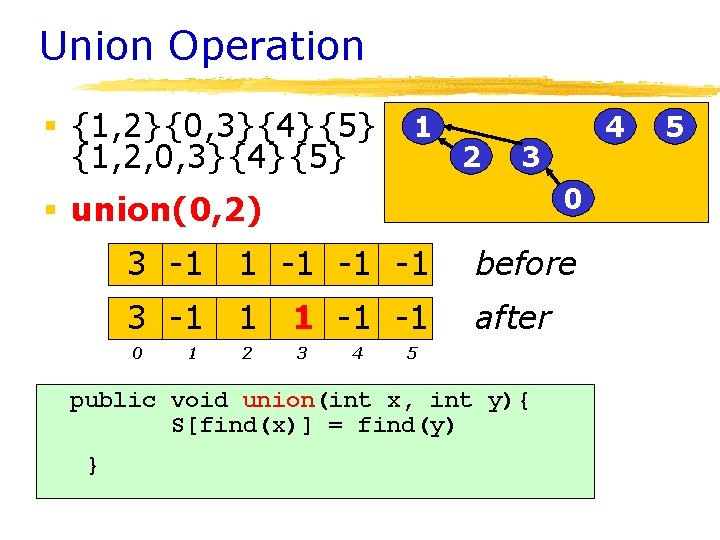

Union Operation § {1, 2}{0, 3}{4}{5} {1, 2, 0, 3}{4}{5} 1 2 3 0 § union(0, 2) 3 -1 1 -1 -1 -1 before 3 -1 1 after 0 1 2 1 -1 -1 3 4 5 public void union(int x, int y){ S[find(x)] = find(y) } 4 5

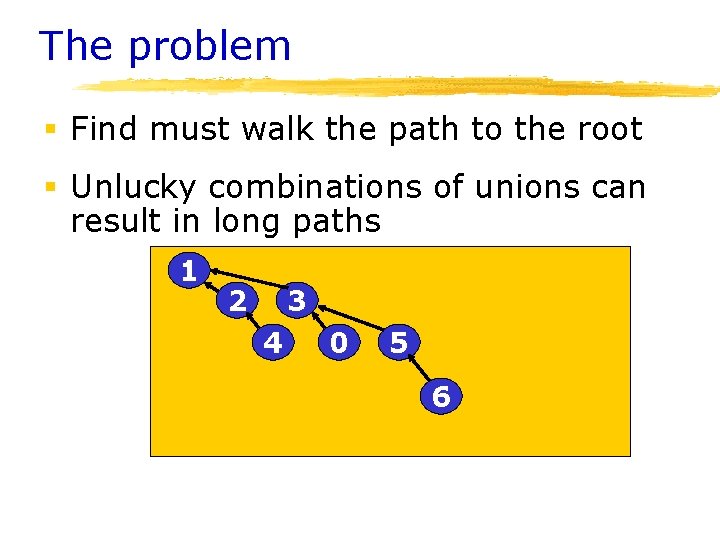

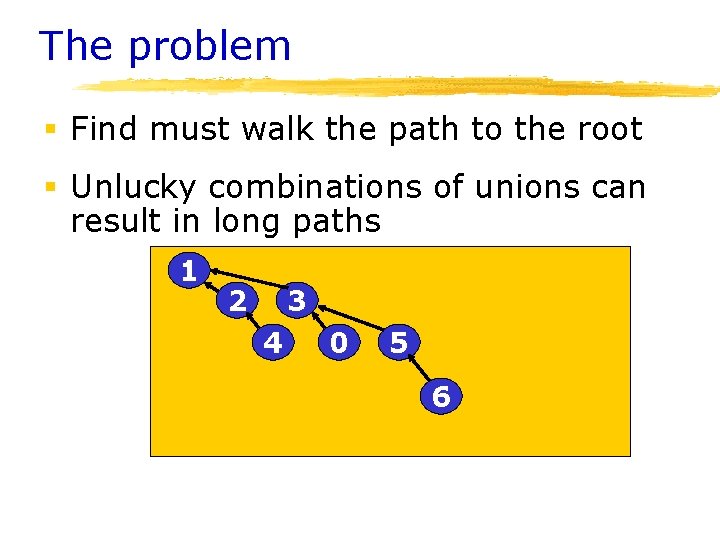

The problem § Find must walk the path to the root § Unlucky combinations of unions can result in long paths 1 2 3 4 0 5 6

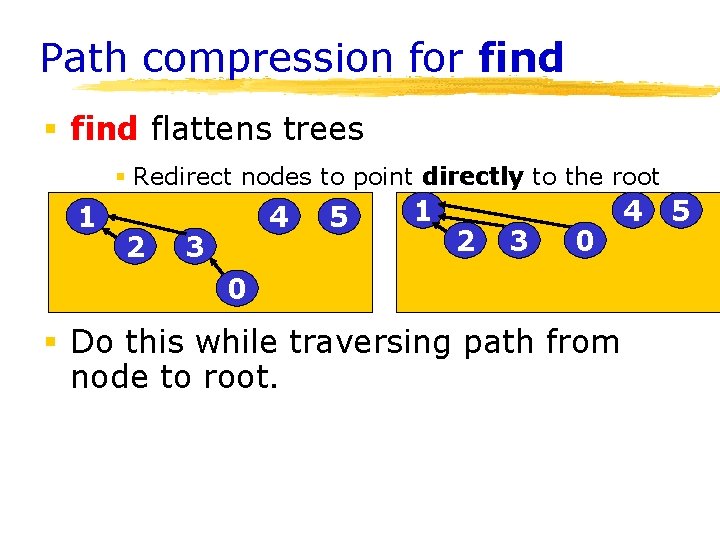

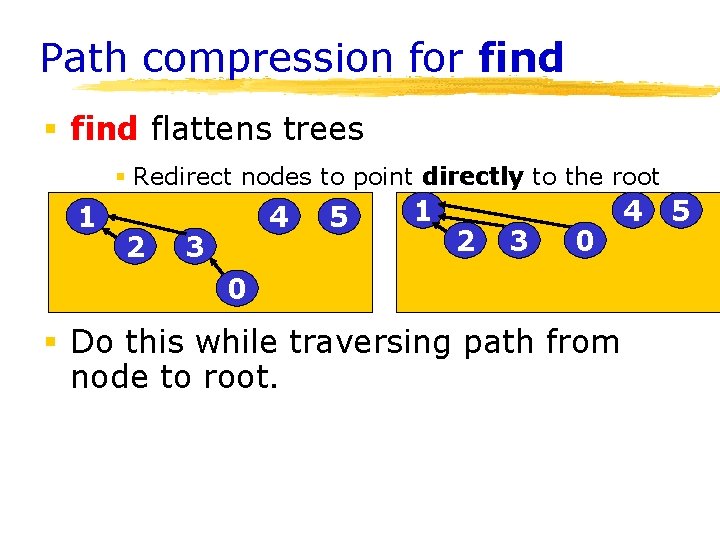

Path compression for find § find flattens trees § Redirect nodes to point directly to the root 1 2 4 3 5 1 2 3 0 0 § Do this while traversing path from node to root. 4 5

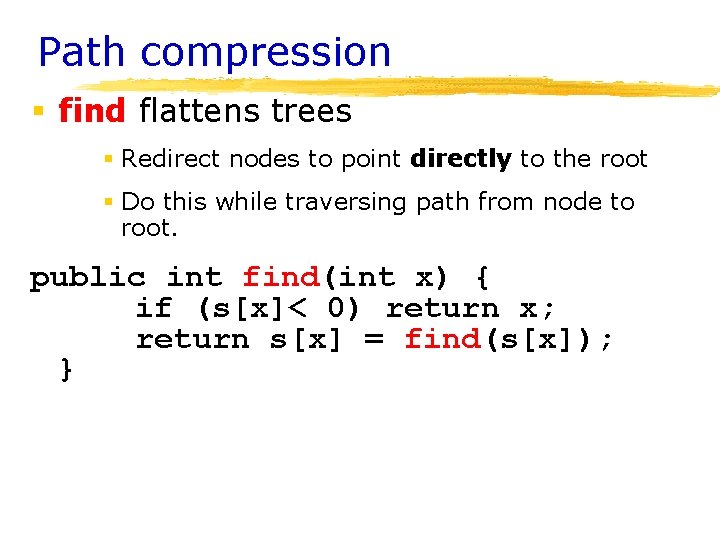

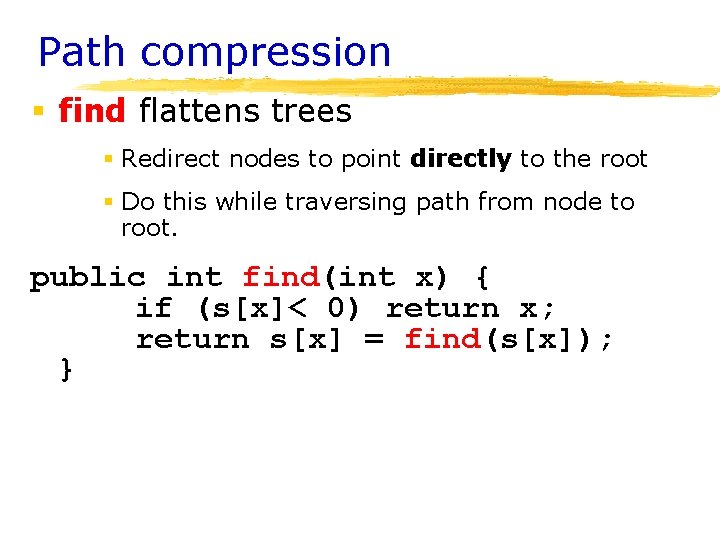

Path compression § find flattens trees § Redirect nodes to point directly to the root § Do this while traversing path from node to root. public int find(int x) { if (s[x]< 0) return x; return s[x] = find(s[x]); }

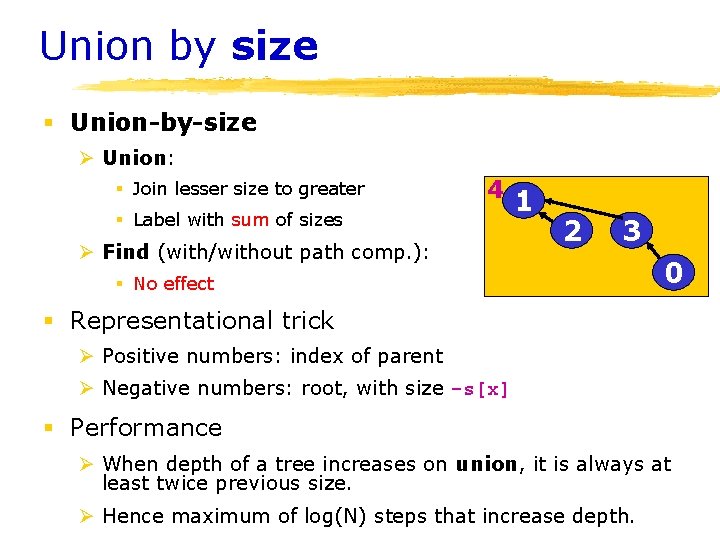

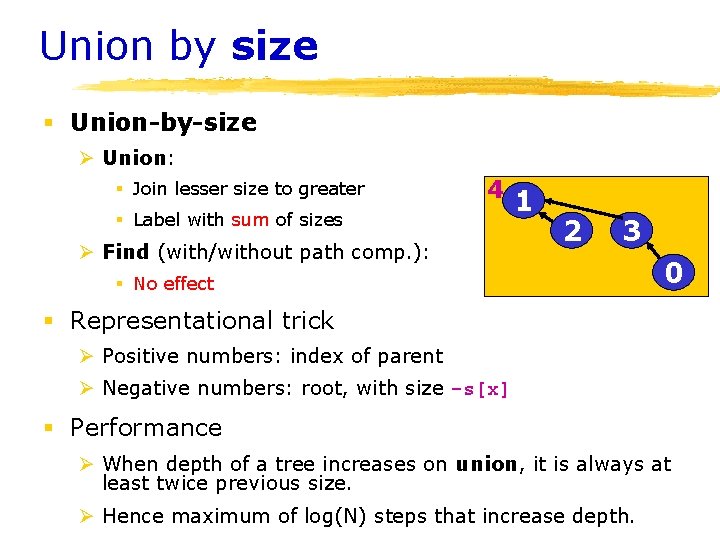

Union by size § Union-by-size Ø Union: § Join lesser size to greater 4 § Label with sum of sizes Ø Find (with/without path comp. ): 1 2 3 § No effect 0 § Representational trick Ø Positive numbers: index of parent Ø Negative numbers: root, with size -s[x] § Performance Ø When depth of a tree increases on union, it is always at least twice previous size. Ø Hence maximum of log(N) steps that increase depth.

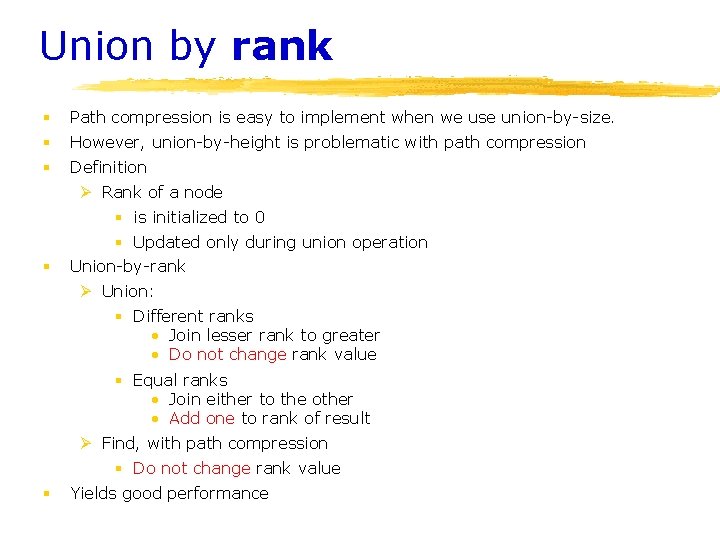

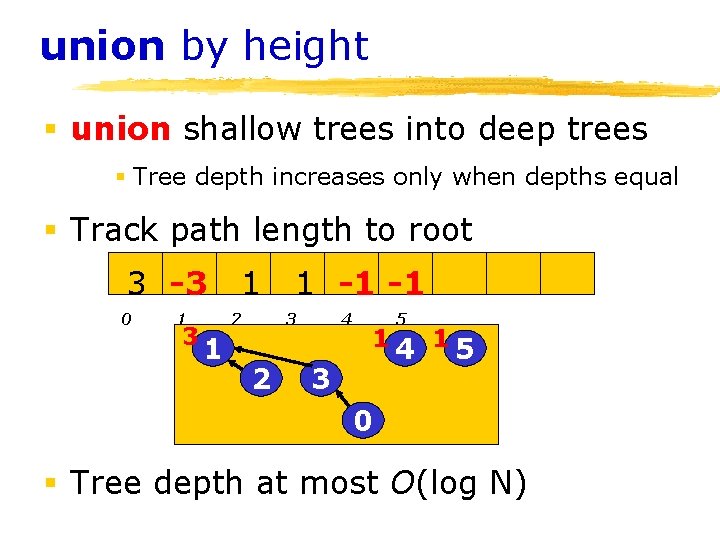

union by height § union shallow trees into deep trees § Tree depth increases only when depths equal § Track path length to root 3 -3 0 1 3 1 2 1 1 -1 -1 3 2 4 1 3 5 4 15 0 § Tree depth at most O(log N)

Union by height, details § Union-by-height Ø Union: § Different heights • Join lesser height to greater • Do not change height values § Equal heights • Join either tree to the other • Add one to height of result Ø Find: § Without path compression • No effect § With path compression • Must recalculate height • Can involve looking at many subtrees 2 1 2 3 0

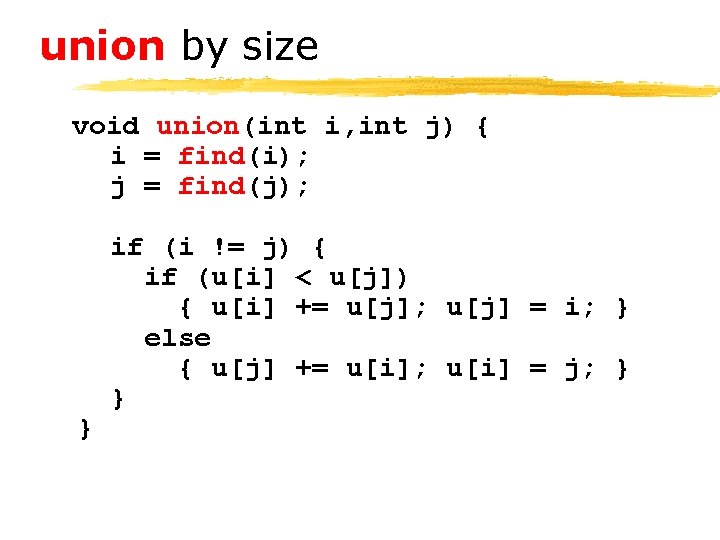

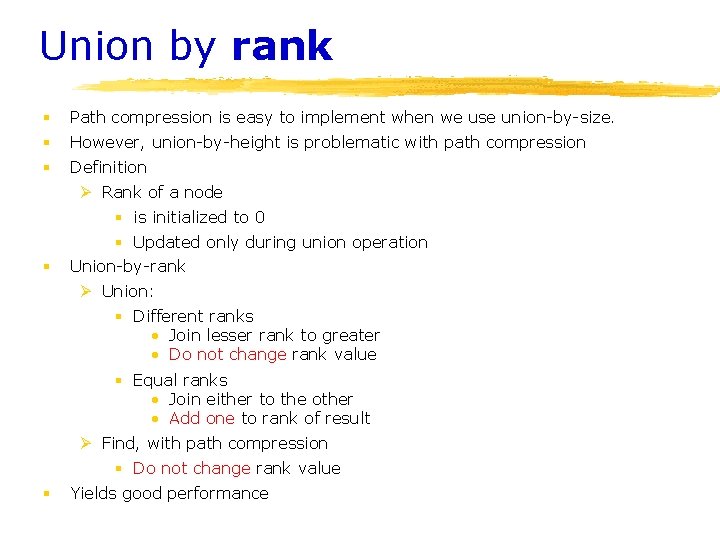

Union by rank § Path compression is easy to implement when we use union-by-size. § However, union-by-height is problematic with path compression § Definition Ø Rank of a node § is initialized to 0 § Updated only during union operation § Union-by-rank Ø Union: § Different ranks • Join lesser rank to greater • Do not change rank value § Equal ranks • Join either to the other • Add one to rank of result Ø Find, with path compression § Do not change rank value § Yields good performance

![All the code class Union Find int u Union Findint n u All the code class Union. Find { int[] u; Union. Find(int n) { u](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bb4d2897b099c698352c70976d1a547/image-49.jpg)

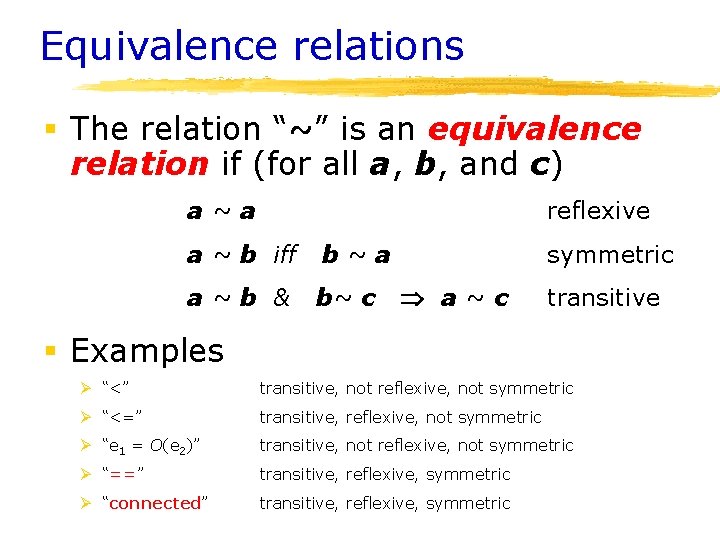

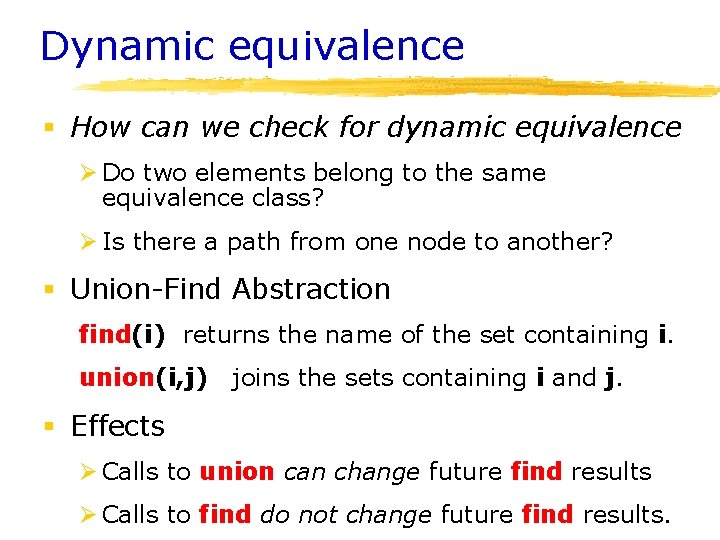

All the code class Union. Find { int[] u; Union. Find(int n) { u = new int[n]; for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) u[i] = -1; } int find(int i) { int j, root; for (j = i; u[j] >= 0; j = u[j]) ; root = j; while (u[i] >= 0) { j = u[i]; u[i] = root; i = j; } return root; } } void union(int i, int j) { i = find(i); j = find(j); if (i !=j) { if (u[i] < u[j]) { u[i] += u[j]; u[j] = i; } else { u[j] += u[i]; u[i] = j; } } }

![The Union Find class Union Find int u Union Findint n u The Union. Find class Union. Find { int[] u; Union. Find(int n) { u](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bb4d2897b099c698352c70976d1a547/image-50.jpg)

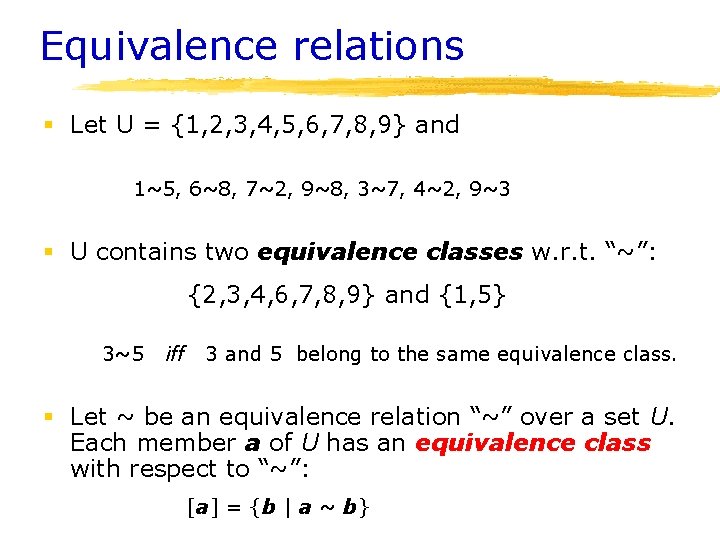

The Union. Find class Union. Find { int[] u; Union. Find(int n) { u = new int[n]; for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) u[i] = -1; } int find(int i) {. . . } } void union(int i, int j) {. . . }

![Iterative find int findint i int j root for j i uj Iterative find int find(int i) { int j, root; for (j = i; u[j]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bb4d2897b099c698352c70976d1a547/image-51.jpg)

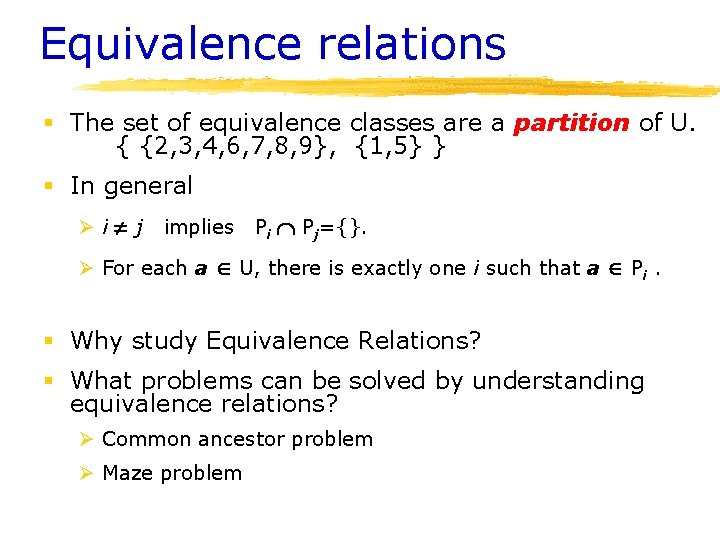

Iterative find int find(int i) { int j, root; for (j = i; u[j] >= 0; j = u[j]) ; root = j; while (u[i] >= 0) { j = u[i]; u[i] = root; i = j; } } return root;

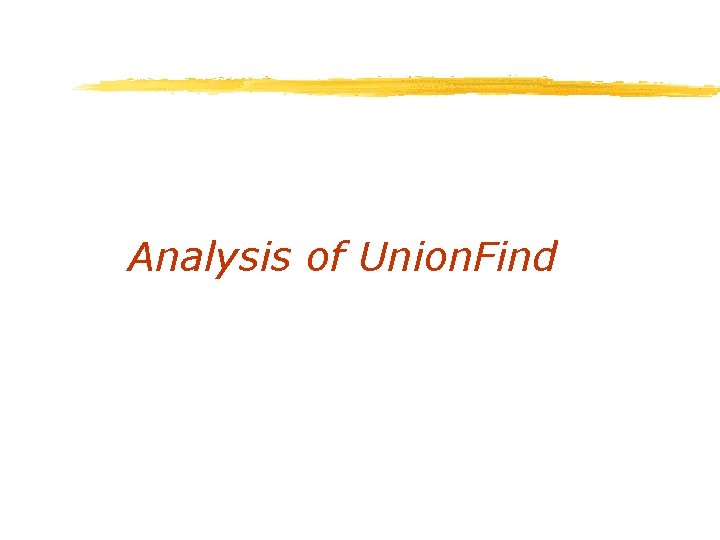

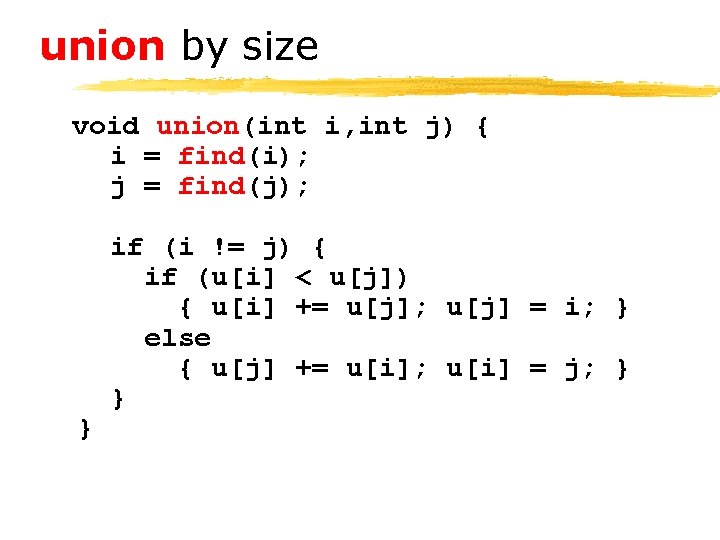

union by size void union(int i, int j) { i = find(i); j = find(j); } if (i != j) { if (u[i] < u[j]) { u[i] += u[j]; u[j] = i; } else { u[j] += u[i]; u[i] = j; } }

Analysis of Union. Find

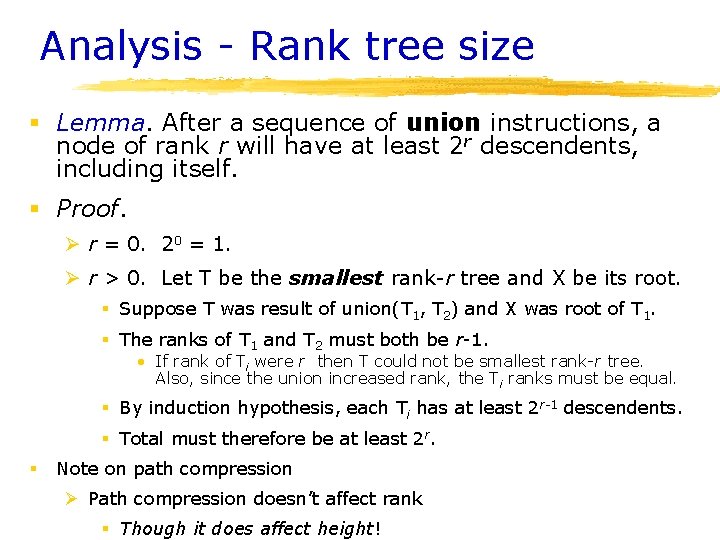

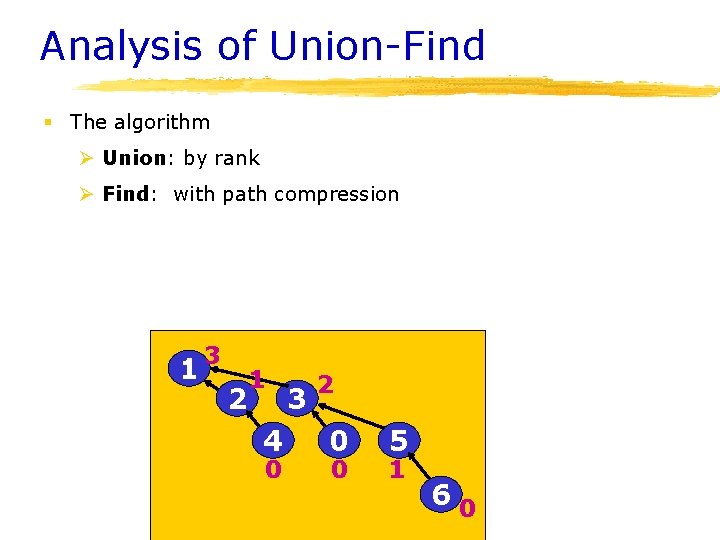

Analysis of Union-Find § The algorithm Ø Union: by rank Ø Find: with path compression 1 3 2 1 4 0 3 2 0 0 5 1 60

Analysis - Rank tree size § Lemma. After a sequence of union instructions, a node of rank r will have at least 2 r descendents, including itself. § Proof. Ø r = 0. 20 = 1. Ø r > 0. Let T be the smallest rank-r tree and X be its root. § Suppose T was result of union(T 1, T 2) and X was root of T 1. § The ranks of T 1 and T 2 must both be r-1. • If rank of Ti were r then T could not be smallest rank-r tree. Also, since the union increased rank, the Ti ranks must be equal. § By induction hypothesis, each Ti has at least 2 r-1 descendents. § Total must therefore be at least 2 r. § Note on path compression Ø Path compression doesn’t affect rank § Though it does affect height!

Analysis - Nodes of rank r § Lemma. The number of nodes of rank r is at most N/2 r. § Proof. Ø Each node of rank r roots a subtree of at least 2 r nodes. Ø No node within the subtree can be of rank r. So all subtrees of rank r are disjoint. Ø At most N/2 r subtrees. § Examples: Ø rank 0: at most N subtrees (i. e. , every node is a root). Ø rank log(N): at most 1 subtree (of size N).

Analysis - Ranks on a path § Lemma. Node rank always increases from leaf to root. § Proof. ØObvious if no path compression. ØWith path compression, nodes are promoted from lower levels and hence were of lesser rank.

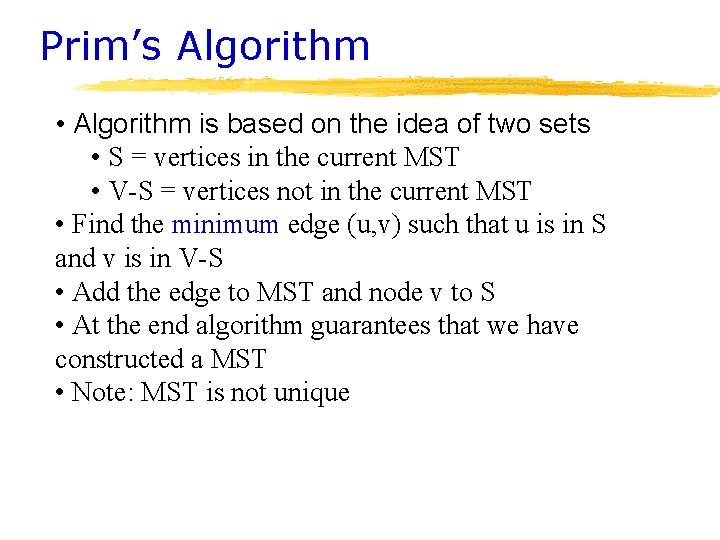

Time bounds § Variables Ø M operations. § N elements. Algorithms Ø Simple forest representation § Worst: find O(N). mixed operations O(MN). § Average: tricky Ø Union by height; Union by size § Worst: find O(log N). mixed operations O(M log N). § Average: mixed operations O(M) Ø Path compression in find § Worst: mixed operations: “nearly linear” [analysis in 15 -451]