MSc Course in Ship Management International Ship Chartering

- Slides: 57

MSc Course in Ship Management International Ship Chartering by Professor Alkis John Corres

SECTION ONE CHOICE OF RULES IN THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SHIPPER AND CARRIER

There are Rules which describe the relationship between shipper and carrier. There are presently three sets of Rules in existence, two of which in force and another one expected to enter into force in the near future. These are: • The Hague Visby Rules (HVR) which enjoy widespread international recognition, signed in 1924, cover 80% of global commerce. • The Hamburg Rules (HR) which are more in favour of the charterer/shipper side and have limited acceptance/application, signed in 1978, cover 15% of global commerce, and • The Rotterdam Rules (RR) which introduce some new concepts in the relationship between the parties. The RR have been designed with liner shipping more in mind, however theoretically there is nothing limiting their application in the bulk trades (provided this is reflected in a Clause Paramount).

Brief description of the HVR When applicable: • The HVR apply only to international voyages i. e. the Bill of Lading must concern the transportation of cargo to another country. • These Rules explicitly exclude deck cargo and the carriage of living animals. • The Rules apply automatically in the following cases: - When the Bill of Lading was issued in a signatory state to the HVR. - When cargo loading takes place in the port of a signatory state, and, - When the two contracting parties have inserted in the Bill of Lading a clause declaring that the contract of carriage has been made under the HVR.

Obligations of the carrier under the HVR • The carrier is under obligation to provide a seaworthy and cargo-worthy vessel on arrival to the loading port and before departure. • According to Article IV(1) the carrier is responsible for cargo loss or damage only in cases when he has failed his obligation to display ‘’due diligence’’ to restore seaworthiness when lost. • The carrier must also handle, store, transport, protect and discharge the cargo appropriately while showing care. • The above provision clarifies that the carrier has in fact a ‘’duty of care’’ towards the owner of the cargo in the legal sense of the term.

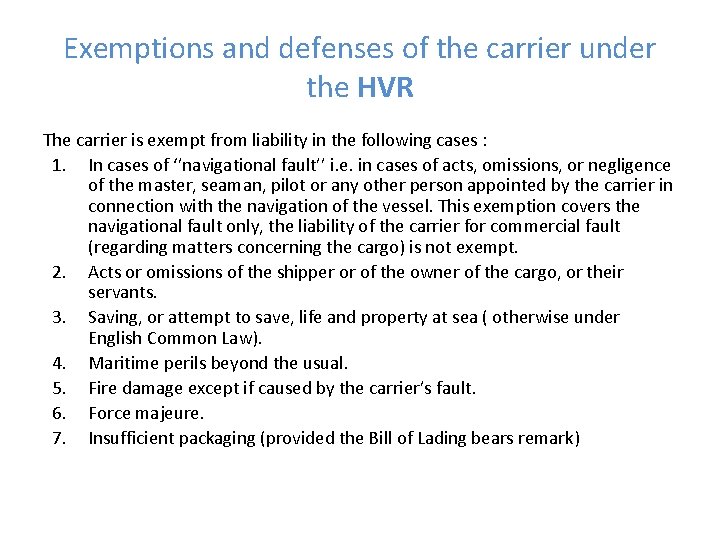

Exemptions and defenses of the carrier under the HVR The carrier is exempt from liability in the following cases : 1. In cases of ‘’navigational fault’’ i. e. in cases of acts, omissions, or negligence of the master, seaman, pilot or any other person appointed by the carrier in connection with the navigation of the vessel. This exemption covers the navigational fault only, the liability of the carrier for commercial fault (regarding matters concerning the cargo) is not exempt. 2. Acts or omissions of the shipper or of the owner of the cargo, or their servants. 3. Saving, or attempt to save, life and property at sea ( otherwise under English Common Law). 4. Maritime perils beyond the usual. 5. Fire damage except if caused by the carrier’s fault. 6. Force majeure. 7. Insufficient packaging (provided the Bill of Lading bears remark)

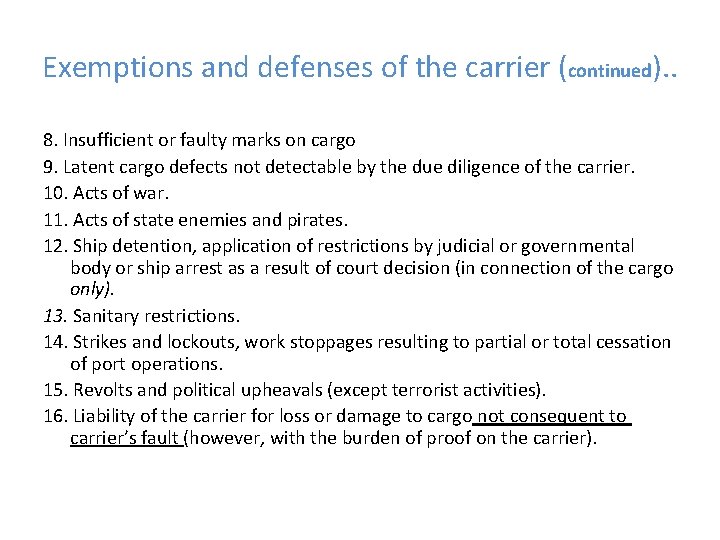

Exemptions and defenses of the carrier (continued). . 8. Insufficient or faulty marks on cargo 9. Latent cargo defects not detectable by the due diligence of the carrier. 10. Acts of war. 11. Acts of state enemies and pirates. 12. Ship detention, application of restrictions by judicial or governmental body or ship arrest as a result of court decision (in connection of the cargo only). 13. Sanitary restrictions. 14. Strikes and lockouts, work stoppages resulting to partial or total cessation of port operations. 15. Revolts and political upheavals (except terrorist activities). 16. Liability of the carrier for loss or damage to cargo not consequent to carrier’s fault (however, with the burden of proof on the carrier).

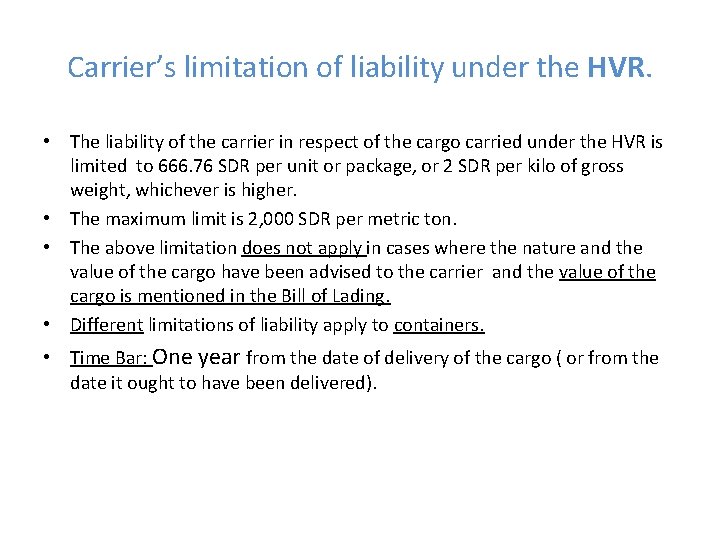

Carrier’s limitation of liability under the HVR. • The liability of the carrier in respect of the cargo carried under the HVR is limited to 666. 76 SDR per unit or package, or 2 SDR per kilo of gross weight, whichever is higher. • The maximum limit is 2, 000 SDR per metric ton. • The above limitation does not apply in cases where the nature and the value of the cargo have been advised to the carrier and the value of the cargo is mentioned in the Bill of Lading. • Different limitations of liability apply to containers. • Time Bar: One year from the date of delivery of the cargo ( or from the date it ought to have been delivered).

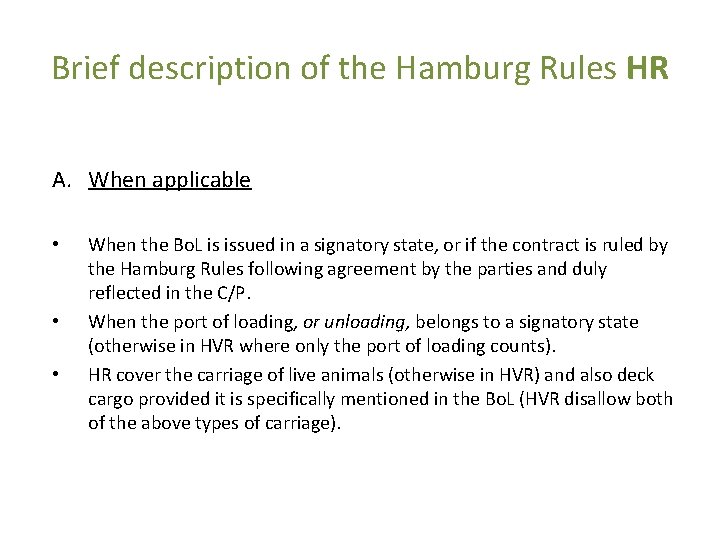

Brief description of the Hamburg Rules HR A. When applicable • • • When the Bo. L is issued in a signatory state, or if the contract is ruled by the Hamburg Rules following agreement by the parties and duly reflected in the C/P. When the port of loading, or unloading, belongs to a signatory state (otherwise in HVR where only the port of loading counts). HR cover the carriage of live animals (otherwise in HVR) and also deck cargo provided it is specifically mentioned in the Bo. L (HVR disallow both of the above types of carriage).

HR continued. . B. Carrier’s liability The liability of the carrier under the HR is increased compared to the HVR in three ways: • Deletion of the list of carrier’s exemptions from liability and in particular of the navigational error, • Extension of the time bar for charterers’ claims, and • Transfer of the burden of proof from the charterer/ shipper to the carrier.

HR continued… C. Limits of liability and time bar • The double criterion applicable to HVR still applies here but the limits of liability are higher ( 835 SDR per package instead of 666. 67 SDR in HVR and 2. 5 SDR per kilo instead of 2. 0 SDR in the HVR). • The carrier is responsible for delays in the delivery of the cargo up to two and a half times the freight rate for the parts of cargo in delayed delivery. • The carrier loses his limitation of liability in cases of willful misconduct and gross negligence with knowledge that damage might occur. • Time bar for claims is double to that of HVR, two years instead of one, from the date the cargo was delivered (or it ought to have been delivered).

The Rotterdam Rules RR The Rotterdam Rules are not yet in force and their eventual entry into force is expected to significantly change the legal landscape of carriage of goods by sea. RR are the second attempt in four decades to bring changes to the widely adopted HVR following pressure from shippers, charterers and receivers in view of the limited success of the HR. The RR bring radical changes to the status of port terminals by allowing for direct action against them. At the same time they regulate the electronic means of e-Commerce and incorporate environmental protection parameters. The RR – although being more friendly to door transport – are not a multimodal convention.

RR continued. . • The RR make use of the concept of ‘’Contract of Transport’’ which makes the use of a Bo. L optional. • There is no more an obligation to issue Bo. Ls to evidence the existence of a contract of carriage, however Bo. Ls will not under the RR disappear. Their role will be separate from the contract of transport. • The requirement under the RR is to have a ‘’Contract of Transport’’ and a ‘’document of transport’’.

Rights and obligations of the carrier under the RR • In general the obligations of the carrier are more extensive and cover door to door delivery. To this end there is a duty to receive and deliver the goods. • Generally the carrier is responsible/liable in case of damage occurred whilst the goods are in his own period of responsibility, unless he can prove that damage was not due to his own fault, or under certain circumstances. • The periods of responsibility under the different Rules are as follows: Ø HVR: Loading – discharging Ø HR : Port of loading – Port of discharge Ø RR : Receipt – Delivery of the goods ( considerably wider)

Rights and obligations of the carrier under the RR continued. . • According to Article 12 the duty of the carrier is to take the goods to destination. • Under Article 13 the obligation entails the duties to “ receive, load, handle, stow, carry, keep, care for, unload and deliver the goods’’. • The obligation for providing a seaworthy vessel is for the entire duration of the voyage (i. e. continuous as under English Common Law) rather than interrupted as in the case of HVR. • The ‘’nautical fault’’ does not exist under the RR. • Time bar is as per HR, i. e. two years. • Delays in transit times can lead to claims under the RR.

Rights and obligations of the shipper under the RR. • Duties: To deliver the goods in good condition and provide the requisite information concerning the goods and the draft Bo. L. • Rights: To obtain a Bo. L once the goods have been delivered to the carrier. • The shipper does not have the right to limit his liability but there is a question mark regarding the substance of such a liability when – according to the Contract of Carriage – the responsibility for the goods rests with the carrier. • Freight Forwarders: Are accommodated under the RR either as ‘’carriers’’ or as ‘’documentary shippers’’. • Liability limits : are higher than both HVR and HR at SDR 875 per parcel. One party only is entitled to give instructions to the carrier. • Ship arrest: The ability of the shipper to arrest the ship of the carrier has been enhanced.

SECTION TWO CONTRACT TERMS, NEGOTIATIONS AND THE CONSEQUENCES OF BREACHES UNDER THE HVR

Ship chartering is a negotiations’ based procedure between the cargo and the ship side. • In a similar way to Marine Insurance negotiations, the display of ‘’good faith’’ from both sides is a prerequisite. • Negotiation revolves around the terms of a standard charterparty form chosen by the parties. • The parties have the right to add, delete, or modify the original provisions to suit their requirements. • When negotiations are completed – the fixture is outright – the chartering contract goes ‘’on subjects’’ for final approval usually from the charterer’s side. Subjects must be lifted within certain date, otherwise there is no deal. • The parties must be aware there are rules by custom on conduct which have taken the form of Court decisions.

Charterparties contain two basic categories of terms, express and implied, which are both valid. • Express are called the written terms referenced in the charterparty. • Implied are called the terms which are not written but considered to be mutually known, understood and accepted by the contracting parties. • For example the need for the vessel offered to be in a seaworthy condition on arrival and before sailing is an implied term.

Charterparty terms can be distinguished according of the severity of consequences of breaching them in the following three categories. . • Representations • Warranties • Conditions Representations: These are statements made during the course of negotiations and it is important these are true. In case found to be untrue there are two possibilities. If made without intention to mislead and/or by mistake the representer must compensate the other party for any damages it may have suffered. If, on the other hand, the representation was made intentionally we have a case of misrepresentation which is serious enough to give the right to the other party to declare the contract null and void. For example, the owners may have described their vessel as in very good condition after extensive repairs. If found that no such repairs had taken, place the owners may be found to have intensionally misrepresented the case and the charterer may choose to rescind the contract.

Warranties and Conditions • Warranties: are usually given concerning the performance of a vessel or certain details of the fixture. The breach of a warranty gives the right to the injurious party to claim compensation but it does not give it the right to cancel the contract. Typical cases of breach of warranties are the speed of the vessel and its fuel consumption. The Courts have also found a delayed redelivery of a vessel from Time Charter to be a breach of a warranty. • Conditions: The breach of a condition is a very serious matter as it gives the right to the injured party, not only to cancel the contract but also to claim compensation for damages. Court decisions have confirmed that: • • • the flag and class of the vessel, the date of sailing from the port of loading, the position of the ship at the date of signing the charterparty, the carrying capacity of the vessel and its readiness to load within the agreed dates . . belong in this category of terms.

To somewhat blur the picture there is also another category of terms. • These are called ‘’innominate terms’’ indicating that the degree of graveness of consequences in case of a breach can be either that of a warranty, or that of a condition. • In practice the outcome of such a case depends on the severity of damage inflicted on the injured party by the breach. Classic example of an innominate term is seaworthiness, i. e. the lack thereof. • In such cases the claimant can either seek compensation for the damages suffered as a result of the breach ( i. e. like a breach of a warranty), or rescind from the contract claiming at the same time compensation for the damages incurred (i. e. like a breach of a condition). • The judgment in such cases rests with the Court, or the Arbitration Court, dealing with the issue.

The fundamental implied obligations of the contracting parties are as follows. . The carrier • Is under obligation to provide a seaworthy vessel, suitable in all respects for the loading and transportation of the cargo mentioned in the charterparty. • He is also obliged to execute the voyage without any undue delay , and. . • . . not to deviate from the proper route unjustifiably. The charterer on the other hand is obliged to • refrain from loading dangerous cargo on the vessel without due notice to the master, and. . • . . to indicate a safe port for the discharge of the cargo (should that become necessary as a result of conditions rendering the original port of discharge unsafe, or for any other reason).

The meaning of the word ‘’seaworthiness’’ is generally wider than the common understanding of the word suggests. A vessel can be unseaworthy for a variety of reasons involving, but not limited to, the following: • Ship safety including aspects of technical safety ( hull and/or machinery aspects including equipment onboard) • Legal and administrative efficiency ( i. e. compliance with international and national legislation, flag bylaws etc) • Sufficient supplies (fuel, stores, provisions, fresh water and spare parts) for the execution of the voyage. • Appropriate manning according to flag requirements with duly certified officers according to international requirements, and • Suitable spaces onboard for the safe storage of the cargo during voyage (cargo worthiness). Lack of any of the above can lead to un-seaworthiness claims by various parties. Attention I drawn on the last bullet where unsuitable cargo loading spaces can lead not only to the rejection of the vessel/ cancellation of the C/P but also to claims for consequential damages.

In contrast to English Common Law provisions which demand the vessel to be in seaworthy condition throughout the voyage, the HVR allow for an interrupted obligation of the owners. • The Hague Visby Rules (Carriage of Goods by Sea Act in the UK) have replaced the above onerous obligation of the owners with the duty to display ‘’due diligence’’ for maintaining the vessel in seaworthy condition. • According to these provisions a ship must be in seaworthy condition on arrival at the loading port and before departure ( for the loaded leg of the voyage), therefore the obligation is not continuous anymore but interrupted. • In case of an event rendering the vessel unseaworthy the owners are under obligation to display ‘’due diligence’’ to restore the vessel to seaworthy condition. • As previously said breaches to the innominate term ‘’seaworthiness’’ require arbitration or Court interpretation regarding the severity of consequences for the owners.

Any reference to court decisions raises the question of the ‘’burden of proof’’. • Interestingly there are more parties than the charterers which may become involved in seaworthiness – related claims ( e. g. shippers, receivers, cargo interests, P+I clubs etc). • As a general rule the burden of proving the lack of seaworthiness will be for the party claiming the un-seaworthiness of the vessel. • In doing so the claiming party must a. Prove the un-seaworthiness, b. Prove the extent of damages it has suffered as a result and also c. Prove the causal relationship between the lack of seaworthiness of the vessel and the damages incurred. • The owners, on the other hand, will have to prove in Court that they have exercised ‘’due diligence’’ in their efforts to restore the vessel in seaworthy condition.

SECTION THREE REASONABLE DISPATCH, DEVIATION AND SOME OBLIGATIONS ON THE SIDE OF THE CHARTERER UNDER THE HVR

The obligation of the owners to execute the voyage with ‘’reasonable dispatch’’. • According to English Common Law voyage delays related to vessel repairs following weather damage and delayed sailing due to unusually adverse weather conditions are considered as reasonable and will not trigger claims under this heading. • Under the HVR reasonable is considered any delay in the execution of the voyage as a result of actions which would take an average, prudent ship owner on the same ship and voyage acting under the same circumstances. • It is evident the judges in this occasion are given the widest possible discretion, bound only perhaps by previous court cases. • As in the cases of seaworthiness, voyage delays are also innominate terms requiring court interpretation regarding the extent of consequences for the owners.

Deviation from the ‘’proper’’ route is only allowed under HVR when found ‘’reasonable’’. • In theory ‘’ proper route’’ is the one described in the C/P which in practice is seldom – if ever - the case. • Thus one is lead to the ‘’usual route’’ i. e. the one mentioned in maritime guides and publications. Failing that, one is left with the direct geographical route. • Only intentional deviation qualifies as deviation from the voyage route thereby suggesting that unintended deviations do not count as such. • Under the HVR deviations from the route are justified provided they fall in one of the following two cases: A. Saving of life at sea, or attempted saving of life or property, and B. Whenever such deviation is reasonable. • The reasonableness of such a deviation will always be judged by the court as the consequences of unjustified deviation are considerable.

Consequences of unjustifiable deviation. • Under English Common Law unjustifiable deviation is considered as fundamental breach of the contract of carriage. • That means that the carrier cannot benefit from limitation of liability provisions in the contract. • Under the HVR in cases where the charterer has rescinded the contract of carriage demanding compensation, the carrier may claim reasons to avoid liability under IV. 2, or to limit such liability under IV. 5 or claim a time bar of such claims once one year has passed.

Liability of the charterer from undeclared loading of dangerous cargo. Definition: Dangerous cargo is considered : • A. Cargoes mentioned in the IMDG Code of the IMO, • B. Cargo than can be a hazard for other cargoes onboard the vessel and • C. Cargo that can lead to a prohibition to sail or to the arrest of the vessel. The liability of the charterers to advise the carrier about their intention to load dangerous cargo on the ship is strict and absolute and any breaches lead to consequences of breach of a condition. The carrier, once advised, has the option to either refuse loading the dangerous cargo on the vessel, or to request from the charterer- or take himself – protective measures which will render the carriage of the cargo, safe.

Charterer’s duty to nominate safe port • Breach of this obligation has the consequences of a breach on a warranty. • Whether a port is safe for a specific vessel to enter is often a matter of prevailing conditions. This means there are no ports which are always safe, as weather conditions play an important part. Examples of an unsafe port can be as follows: a) Icebound port. b) Strong side winds (usually for large ships). c) Unreliable passage and port depth data. d) Non-availability of tugs with appropriate power for the vessel size. e) Political risks, upheavals. f) Port where discharging the specific cargo is prohibited (e. g no low-flash port).

SECTION FOUR VOYAGE CHARTERS

The main forms of ship charter are the following. . • Voyage charter: Is the contract of carriage of cargo by a certain vessel under specific terms within agreed days for loading (laycans). • Time charter: Is the charter contract under which a vessel is chartered for a specific time period under specific terms. • Bareboat charter: Is also a form of a time charter whereby the bareboat charterer assumes the role and duties of a shipowner (i. e. both the technical and the commercial management of the vessel). • Contract of Affreightment: Is the agreement for the carriage of high volumes of transportation within a certain time period with fixed freight rates for the destinations involved.

The four stages of a ship voyage are as follows. . • The preliminary voyage, or ballast voyage, i. e. the voyage needed in order that the vessel arrives at the loading port within the agreed dates. • The loading operation, i. e. the stage during which the charterer/shipper has to load the vessel with a full and complete cargo usually plus or minus 5%. (Failure to comply with this obligation leads to the obligation to pay Deadfreight i. e. freight for the cargo which was not loaded). • The loaded voyage stage , and • The discharging operation in one or more ports where any deviation from the contractually agreed laytime will be monitored and dealt with (in way of demurrage, or dispatch).

Main characteristics of a Voyage Charter • It is the simplest and the most frequent type of ship charter whereby the charterer pays the freight rate (usually per ton, or lumpsum) and demurrage (only in cases where the contractually agreed laytime is exceeded). • The ship owner pays for all the expenses of the voyage including bunkers and agency charges. • Freight is payable before, or after cargo loading. • Freight is usually prepaid during cargo loading, upon sailing from the load port, or a few days after sailing. • Freight can also be paid later before breaking bulk (BBB), during discharging, or within a specified number of days after discharge.

Voyage charter in a nutshell • The C/P specifies the arrival of the fixed ship within specific laydays. In case the ship arrives to the loadport late – and the charterers feel unable to grant an extension – the charterers have the right to declare the contract null and void. • The vessel tenders a Notice of Readiness (NOR) on arrival which should trigger the boarding of cargo surveyors to verify the suitability of the ship’s cargo spaces for the cargo to be carried. • Upon surveyor’s satisfaction and issuance of a certificate the charterers must normally accept the NOR. • After NOR is accepted the pilot boards the vessel for berthing. • Time starts to count according to the individual C/P provisions only after NOR is accepted by the charterers. • In all cases the time taken for the vessel to sail from the roads to the berth allocated does not count as laytime (it is considered part of the voyage).

Voyage charter in a nutshell continued. . • With the term ‘’laytime’’ the C/P makes reference to the agreed time during which the charterer must complete the loading and unloading operations of the vessel. • In case laytime is exceeded the charterer is in breach and is under obligation to pay demurrage i. e. extra charges for keeping the vessel occupied beyond the agreed time. • The daily rate for demurrage is specified in the C. P. No proof of any damages is necessary for a demurrage claim. • In case laytime is not used in its entirety, in dry cargo only, the owners may be obliged to pay ‘’dispatch’’ money to charterers for freeing the vessel earlier. • Customarily Dispatch=1/2 Demurrage

Freight payment in Voyage Charters • Freight is payable in cash. • In the currency specified in the charterparty. • The money must be paid into the bank account indicated by the owners at the time specified in the C/P. • Freight is not considered as paid unless the money is credited to the bank account of the owners (more about this matter under the time charter discussion later).

There are two contracts which run in parallel during the carriage of goods by sea. • The first one is the chartering contract as discussed so far between charterer and carrier which concerns the reservation of the vessel (or part thereof) for the carriage of the cargo described in the C/P. • The second contract is between the carrier and the receiver of the cargo as manifested by the Bill of Lading (Bo. L). The Bo. L is proof of the type and quantity of the cargo loaded and in some cases of the value of the cargo. • The Bo. L is a title to the ownership of the cargo onboard and as such it allows for the transfer of such ownership before cargo is delivered in a way similar to cheques.

SECTION FIVE TIME CHARTERS

The basics of a time charter • A time charter contract involves the undertaking of the time charterer to pay during the contract period for the hire, the bunkers and the port expenses of the vessel. • A time charter starts (along with the obligation for freight payment) with the delivery of the vessel – which can take place anywhere – and stops with the redelivery – which can also take place anywhere, although many owners prefer it to take place in a port. • In T/C freight is always prepaid, usually two weeks or monthly, in advance. • Upon delivery of the vessel the commercial management of the vessel is transferred to the time charterer for the duration of the contract while the technical management stays with the owners.

On and Off Hire Once the vessel is delivered into T/C and for the duration of the charter period the time charterers are under obligation to pay hire by the due dates to the owners. • This fundamental obligation of the charterers is suspended when events take place preventing or limiting the use of the vessel. • Such events are described in the C/P and can be different from one contract to another. • No fault on the part of the owners is necessary to trigger off-hire events. • The key parameter in off hire is the loss of time, which is expected in contracts where vessel remuneration is time linked.

T/C basics continued. . • The transfer of the commercial management of the vessel to the time charterer upon delivery means that this party acquires – in exchange for the hire it has undertaken to pay - full control on the activity of the vessel and freedom to order it to load and discharge wherever it requires. • The time charterer is free to use the vessel for its own transport needs, or to trade it as a lawful owner would in the open market, or take part in Contracts of Affreightment (Co. As about which see later in this section). • The vessel must be redelivered to her owners within the time prescribed in the C/P. • In case the time charterers wish the vessel to be redelivered earlier (underlap) they need to inform the owners in writing and the latter are under obligation to take the vessel back first and then discuss compensation. • In case the vessel’s redelivery takes place later than the contract dates (overlap) this is considered a breach of a warranty and the daily hire of the vessel will need to be agreed anew.

Early and delayed redelivery in T/C • In case of an underlap redelivery - i. e when time charterers advise owners in writing that they wish to redeliver before the contractual date – the owners will have to take the vessel back and try to reach a commercial agreement for the residual part of the T/C. • Failing this, the parties will need to take the matter to court or arbitration procedure for a resolution of the dispute. • In such cases the state of the relevant freight market is taken into account (higher, lower, or the same as at the time when the vessel was chartered) and the subsequent employment of the vessel in order to subtract such earnings from the time charterer’s obligation to compensate. • Similar reasoning is applicable in cases of overlap delivery where the question arises, which must be the daily rate for the extra time take to redeliver.

Issues surrounding the legitimacy of the last voyage in overlap redelivery. • In view of serious consequences for the owners (e. g. missing the laycans for another time charter) in cases of possible abuse of time charterer’s right to order the vessel at will during the contractual T/C period, this matter has a rich history of admiralty court rulings. • The courts have sought ways to make sure that the order on the part of the time charterers for the last voyage was given in belief that the vessel would be redelivered within the contractual dates (legitimate last voyage). • If otherwise, the last voyage is considered illegitimate taking also into account any tolerance margin (usually 4 -5%) incorporated in the contract. • The two options lead to different possible outcomes for the owners.

Overlap redelivery issues continued. . Legitimate last voyage order In order that the last voyage is legitimate the time charterer must be in belief that it will not be conducent to a delayed redelivery in three different points in time, i. e. • At the time when the order was given, • At the time when the execution of the order starts, and • During the time when this last order is executed. • (House of Lords, The Gregos, 1994). With this court decision the phenomenon of a last voyage order which is legitimate at the time it was given and illegitimate during its execution is eliminated, given the impossibility of refusal to execute the voyage on the part of the owners due to already undertaken responsibilities to third parties via signed and released Bills of Lading.

Owners’ options in overlap redelivery. • In case the order of the last voyage is legitimate the owners are under obligation to execute and the charterers must compensate the vessel with the contractual rate until redelivery. • This is also applicable in cases where the market rate is lower than the contractual rate. • In cases where the prevailing market rate is higher than the rate of the contract the time charterers are under obligation to pay additional compensation to the owners equal to the difference between contractual and market rate.

Owners’ options in overlap redelivery continued… In case of a illegitimate last voyage order the owners have the right to refuse execution offering at the same time an alternative to charterers. • If the time charterers insist on their illegitimate last voyage order the owners can consider it as repudiatory breach of contract, proceed to a new chartering contract and sue the charterers for damages resulting from repudiation. • Alternatively, the owners can agree to the execution of the illegitimate last order demanding the contractual rate until the end of the time charter period with additional compensation equal to the difference between market and contract rates on top of the contractual rate for the extra time taken (only in case the market rates are higher than the contract rates).

Owners’ right to withdraw vessel from T/C • The Owners' have the right to withdraw the vessel for late payment of hire, subject to giving the charterers timely notice when hire is late and reserving their right to withdraw. • All the owners have to prove is that hire has not been paid by the due time - regardless of intention or negligence of the time charterers – and that the charterers have been duly notified as above. • Later hire payment than the due date does not correct the charterer’s breach and consequently does not affect the owners’ right to withdraw, except in the following two cases: Ø The owners declare in writing that they consider the delayed payment as timely and accepted, or Ø There is no notice – within a reasonable time period from them to charterers – refusing the delayed payment. • Acceptance of part-payment of hire from the owners does not affect their right to withdraw the vessel.

The anti-technicality clause • This clause aims at the protection of the charterers from errors and omissions on their side for delayed hire payment which could easily lead to losing the vessel under time charter possibly with serious commercial consequences. • According to this clause the owners undertake the obligation to notify charterers in writing about their intention to withdraw due to nonpayment of the hire giving them time (usually 48 hrs) to proceed with the payment, while guaranteeing that the vessel will not be withdrawn before the date notified. • The wording of the letter – which must not be delivered earlier than the midnight of the due date of the payment – must make clear beyond any doubt that the vessel will be withdrawn unless payment is received within the notice period. • The charterers are not under obligation to be privy of the contents of such letter unless it is delivered during working days/hours.

SECTION SIX OTHER FORMS OF SHIP CHARTER

Bareboat charters BBC • Bareboat charters are a relatively recent form of charter the first application of which dates back to the year 1951 when the Federal Republic of Germany allowed for the first time registration of a foreign flag vessel in the German registry on condition it was chartered by a German company or citizen for a specific period of time. • Bareboat charters are a sub- category of time charters where the time charterer assumes both the commercial and the technical management of the vessel for the duration of the contract. • The important difference with a time charter is the limited incidence of off -hire events as the same party – the bareboat charterer – is also responsible for technical management issues. • Bareboat charters are widely used by financing institutions in cases of Sale and Leaseback and Hire Purchase as they allow banks to remain legal owners of the asset (vessel) while the bareboat charterers assume the role of a disponent owner.

BBC continued. . • In order that bareboat arrangements become possible both registries – the one from which the ship comes and the other to which the ship goes to – must comply with the provisions of the United Nations Convention on Conditions for Registration of Ships (1986), Article 12. • More specifically, the registry of origin must allow for ‘’bareboat out ’’ – i. e. its own registered vessels to be able to enter for a specific time period into another registry – while the receiving registry to allow for ‘’bareboat in’’ i. e. the acceptance of vessels from other registries for a specific time period. • International law clearly demands that every ship is under obligation to fly one flag, therefore there must be a written agreement between originating and receiving registries before the transfer takes place. • All open registries and a limited number of national registries have incorporated bareboat registry arrangements in effort of enhancing their commercial flexibility.

BBC continued… • Entry into a bareboat registry takes effect on basis of a bareboat charter in the name of the bareboat charterer and it does not require a deletion certificate from the registry of origin. • In fact from the time when the vessel enters into the bareboat registry of a certain country and raises its flag it assumes all rights and obligations under the legal system of the country, except for matters concerning the ownership of the vessel and securitization of debt (such as mortgages). • While on bareboat charter the vessel can be sold by its original owners to another party without any consequences regarding the bareboat contract on condition that such change of ownership is reported in writing to the bareboat registry of the receiving state. • A bareboat charter ends naturally when the contract period is over and it is not renewed and when the time period for which the originating registry has given its consent is over. • It can also theoretically end at any time if the originating registry repeals its consent for the specific charter.

Contracts of Affreightment Co. A • • The main purpose of a Contract of Affreightment (Co. A) is to oblige one or more carriers to lift a fixed or determinable quantity of cargo of a specified type over a given period of time to specific destination(s). Usually, the Co. A is not limited to one particular vessel, but operates as a series of voyage charters. Freight is payable on the quantity of cargo transported and the carrier bears the risk of delay en route. Co. As in essence involve two promises. The shipper promises to provide a certain overall quantity of cargo over a period of – usually – one year, and the carrier(s) promise to transport that cargo to the agreed destination(s) within the contract period at the predetermined freight rates. Co. As protect shippers from freight market rises without the risks of a time charter while providing large volumes of cargo to carriers.

Co. As continued… • According to Steamship Mutual: ’’ Given the long term nature of the contract, a COA is almost always tailor made to meet the specific needs of the parties concerned. These parties are the shipper or buyer of the cargo who is often motivated by requiring certainty for the costs of transportation, and the ship-owner who is concerned with providing assured long term employment and flexibility for his owned or chartered in tonnage. • COAs enable the ship-owners to be flexible and allow the vessels to be fitted into a pattern of trade that maximizes laden as against ballast distances and allows such arrangement to be concluded at very competitive rates of freight. • As a result, COAs contain very few standardized terms, other than the individual voyage charter terms that govern each lifting once the vessel has been tendered for loading. • The least standardized part of the contract will be the shipping programme and nomination provisions, and it is these provisions that are the most abused or contested over the period of a lengthy COA. ’’