Motor Control Systems Analysis Design and Optimization Strategies

![Phase III – Optimization Slip Correction – Traction Modeling [7], [8] Phase III – Optimization Slip Correction – Traction Modeling [7], [8]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/b9798de18d78dddaa3caafba47947808/image-13.jpg)

![References [1] Heiney, A. (Ed. ). (2018, April 27). NASA’s Ninth Annual Robotic Mining References [1] Heiney, A. (Ed. ). (2018, April 27). NASA’s Ninth Annual Robotic Mining](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/b9798de18d78dddaa3caafba47947808/image-22.jpg)

- Slides: 23

Motor Control Systems Analysis, Design, and Optimization Strategies for a Lightweight Excavation Robot Austin Crawford MS Candidate, University of Arkansas Committee Chair: Dr. Uche Wejinya

Publications Motor Control Strategies for Drivetrain System of an Excavation Robot - Martian Surface Simulant, submitted to IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 2019. A journal article will be prepared based on overall work.

Outline - Motor Control System • Phase I Analysis – Develop generic process for analysis able to be applied to a multitude of DC motor control applications • Phase II Design – Use techniques established in Phase I and apply to current robot build • Phase III Optimization – Use results from the analysis of the current robot build to identify optimization possibilities for future iterations of the robot • Phase IV Automation – Develop a starting basis for implementation of an automation process for future robot iterations

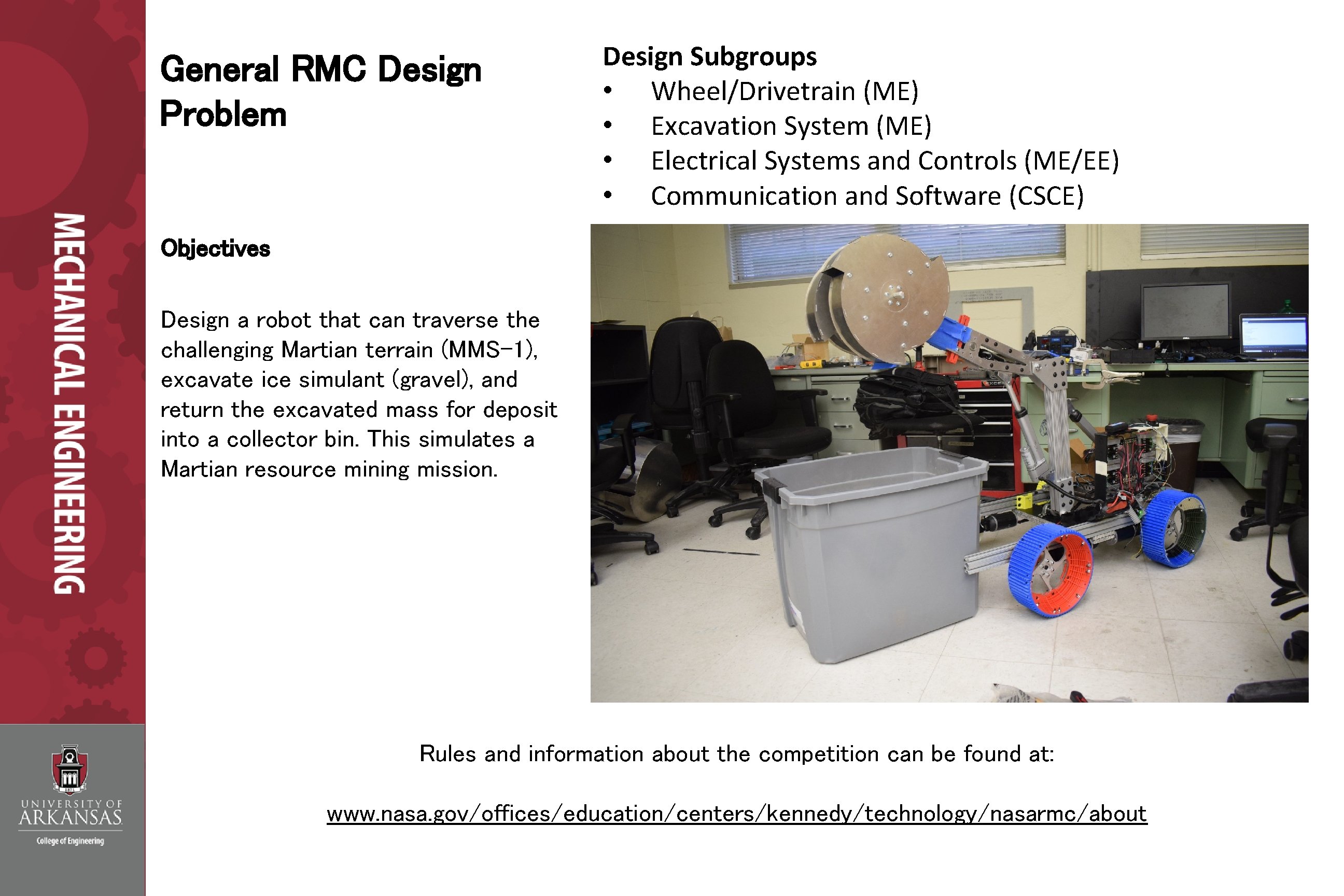

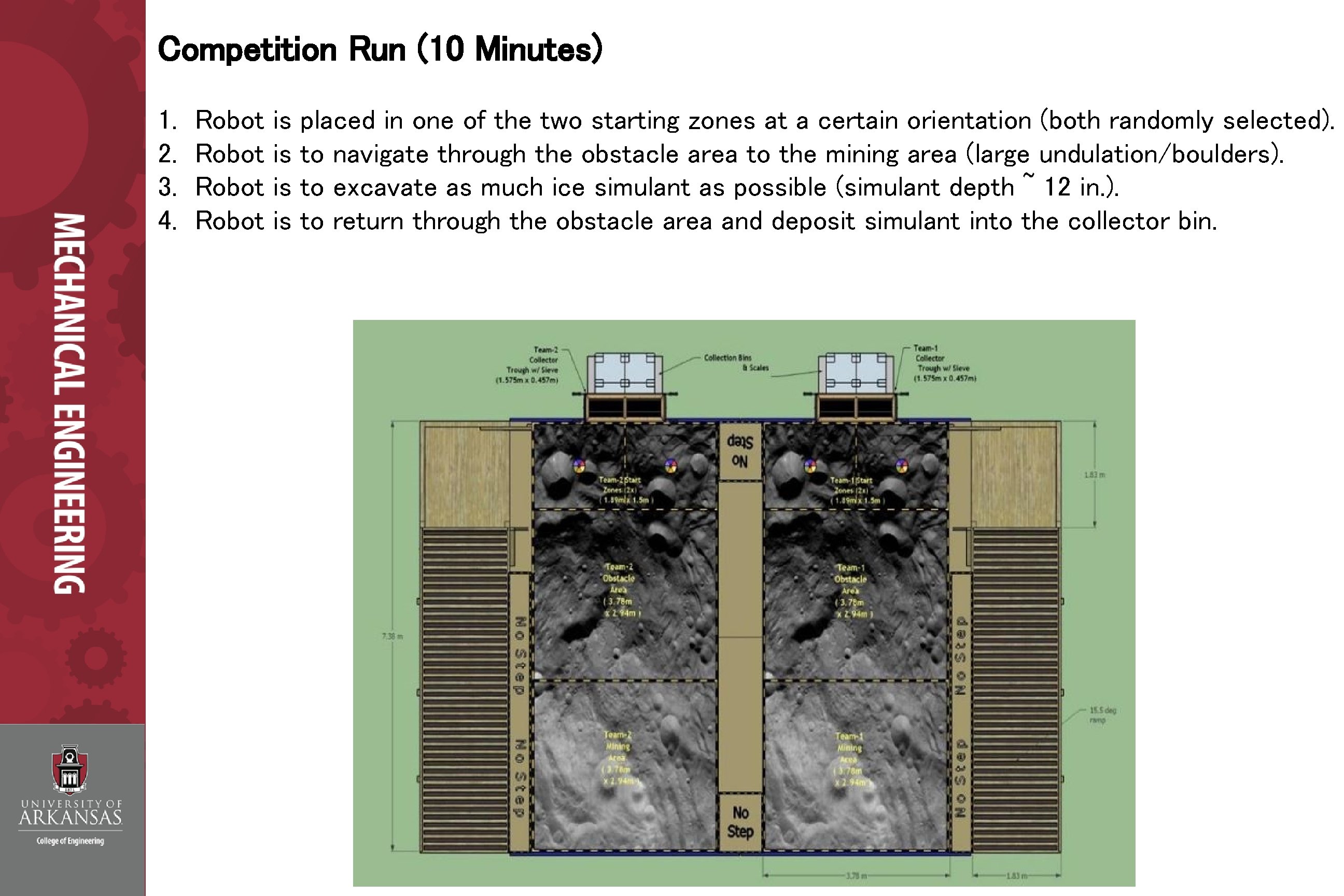

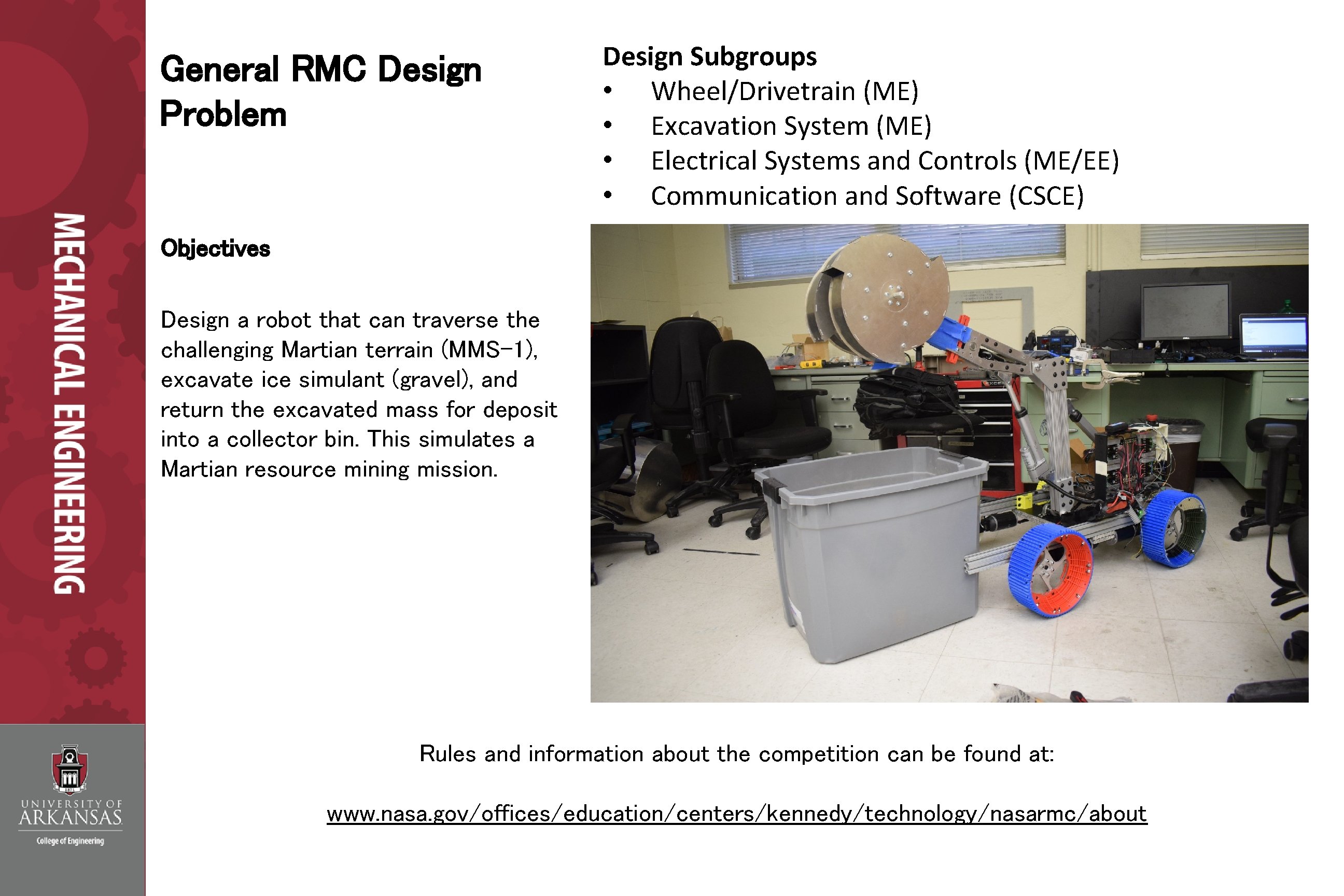

General RMC Design Problem Design Subgroups • Wheel/Drivetrain (ME) • Excavation System (ME) • Electrical Systems and Controls (ME/EE) • Communication and Software (CSCE) Objectives Design a robot that can traverse the challenging Martian terrain (MMS-1), excavate ice simulant (gravel), and return the excavated mass for deposit into a collector bin. This simulates a Martian resource mining mission. Rules and information about the competition can be found at: www. nasa. gov/offices/education/centers/kennedy/technology/nasarmc/about

Competition Run (10 Minutes) 1. 2. 3. 4. Robot is is placed in one of the two starting zones at a certain orientation (both randomly selected). to navigate through the obstacle area to the mining area (large undulation/boulders). to excavate as much ice simulant as possible (simulant depth ~ 12 in. ). to return through the obstacle area and deposit simulant into the collector bin.

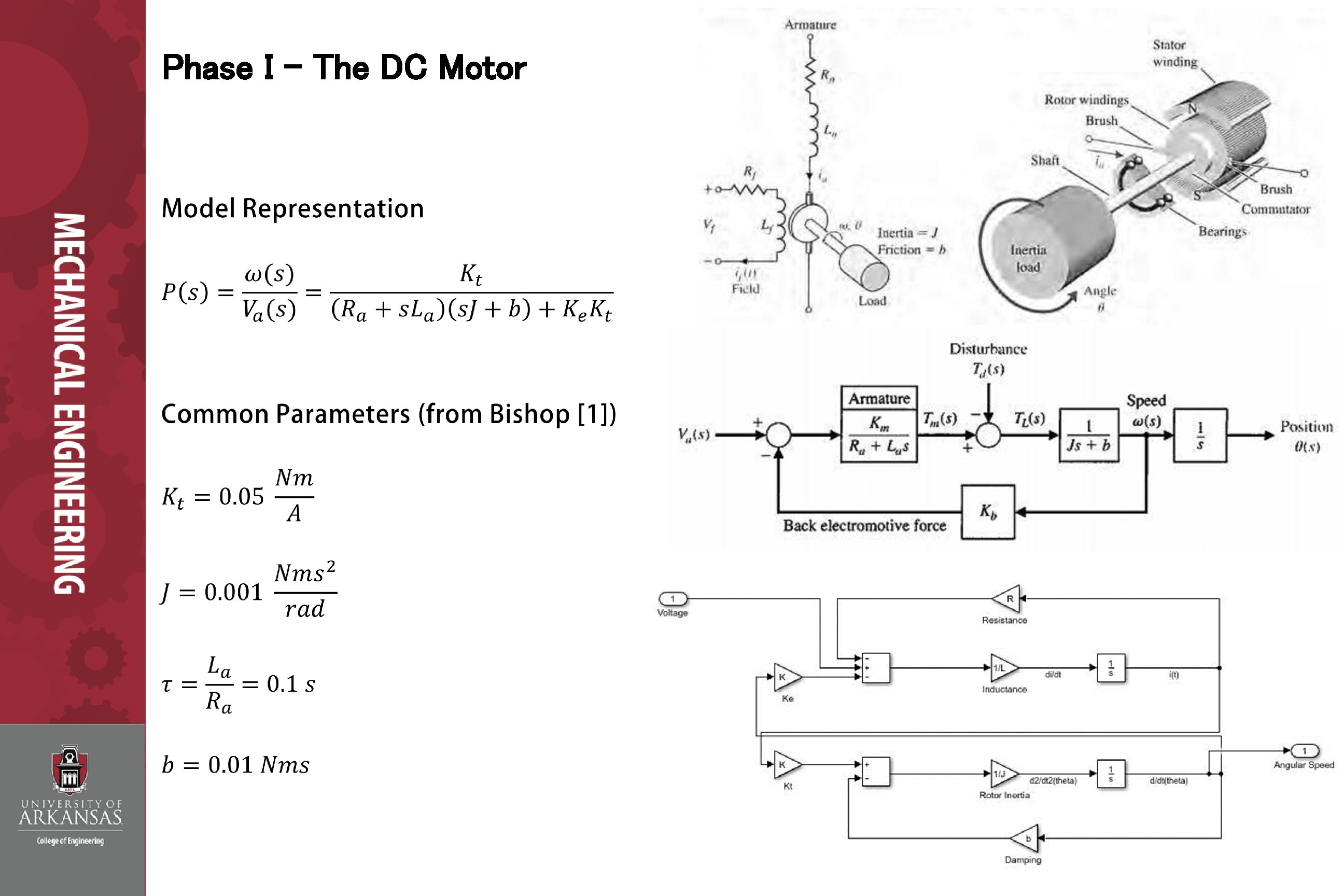

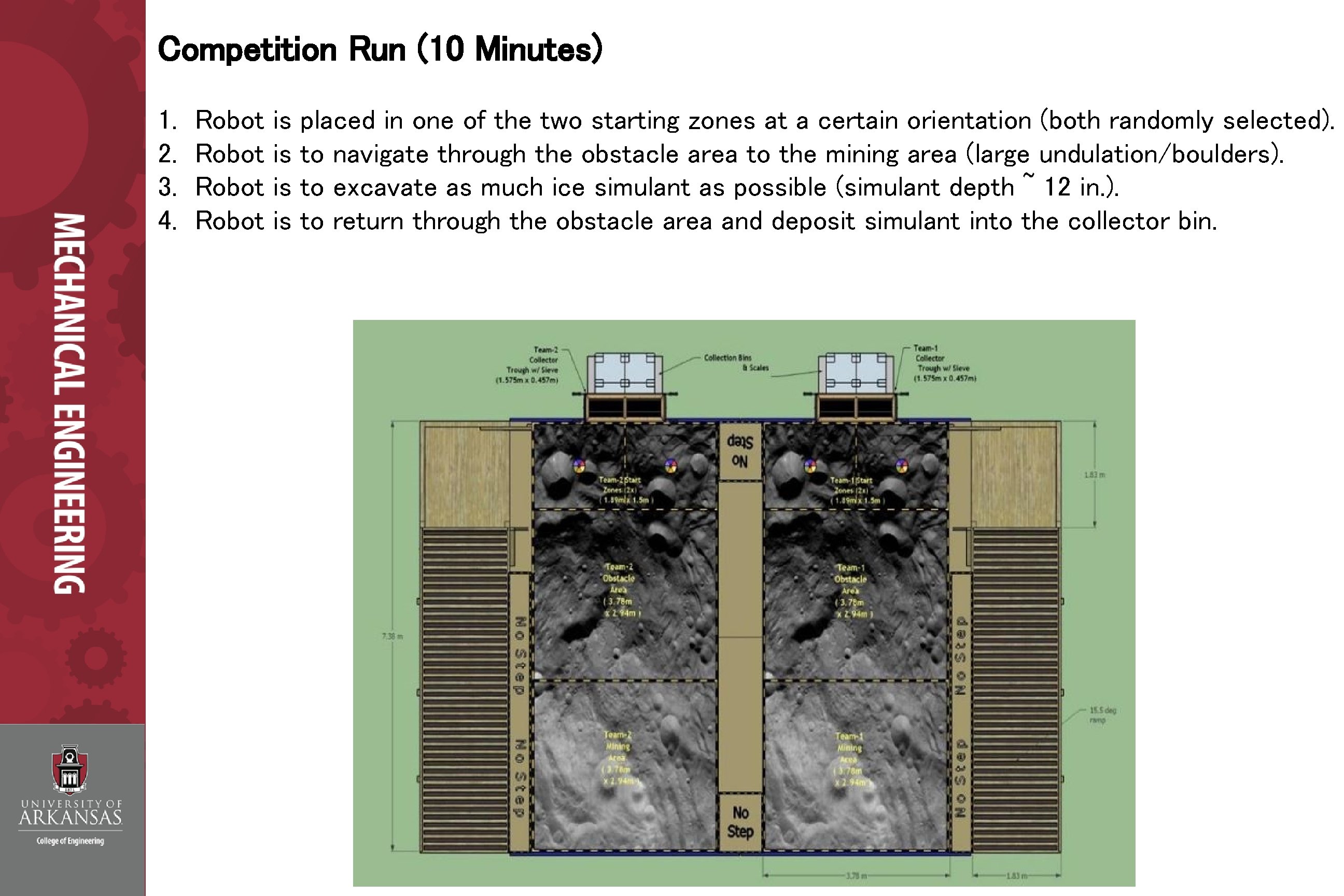

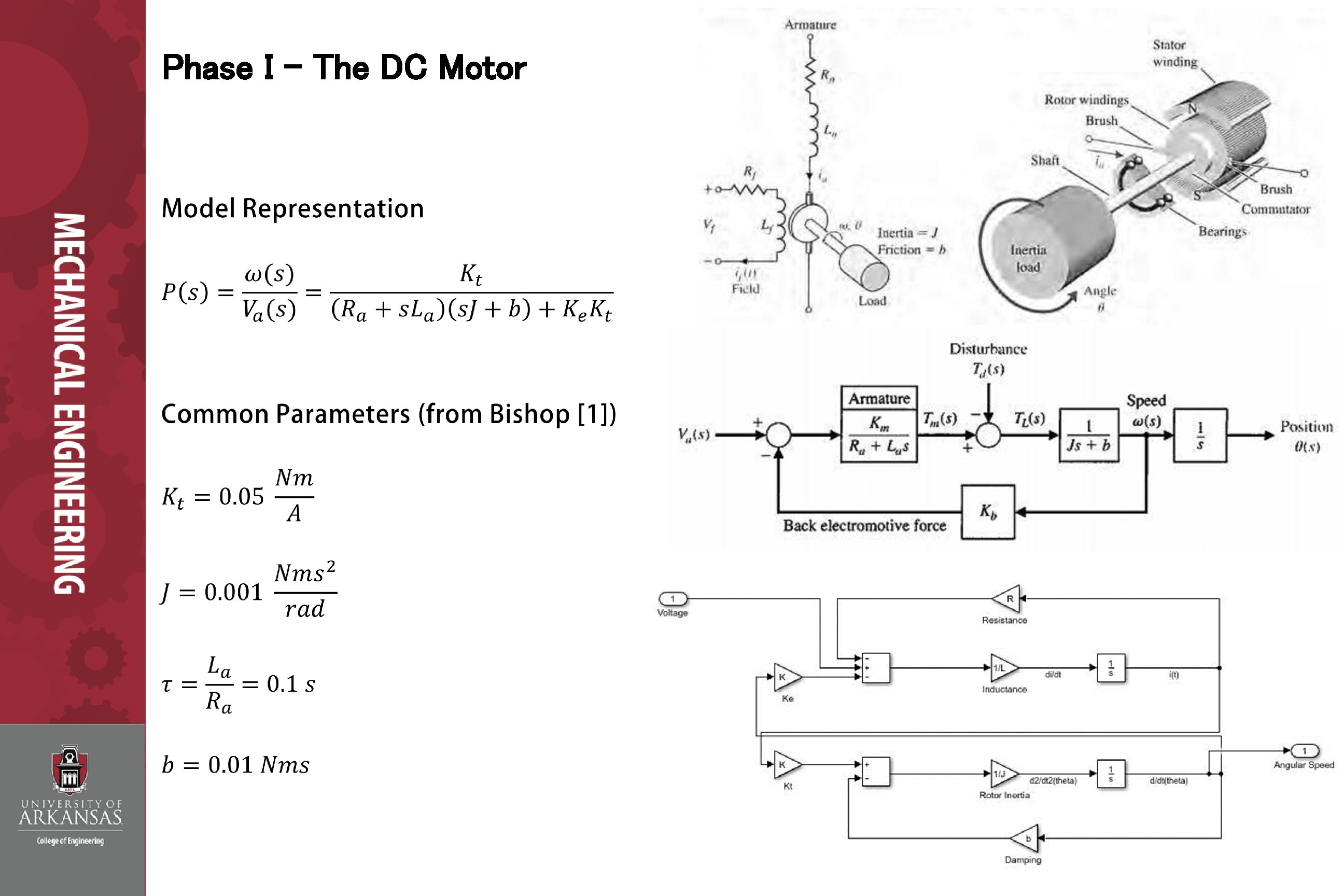

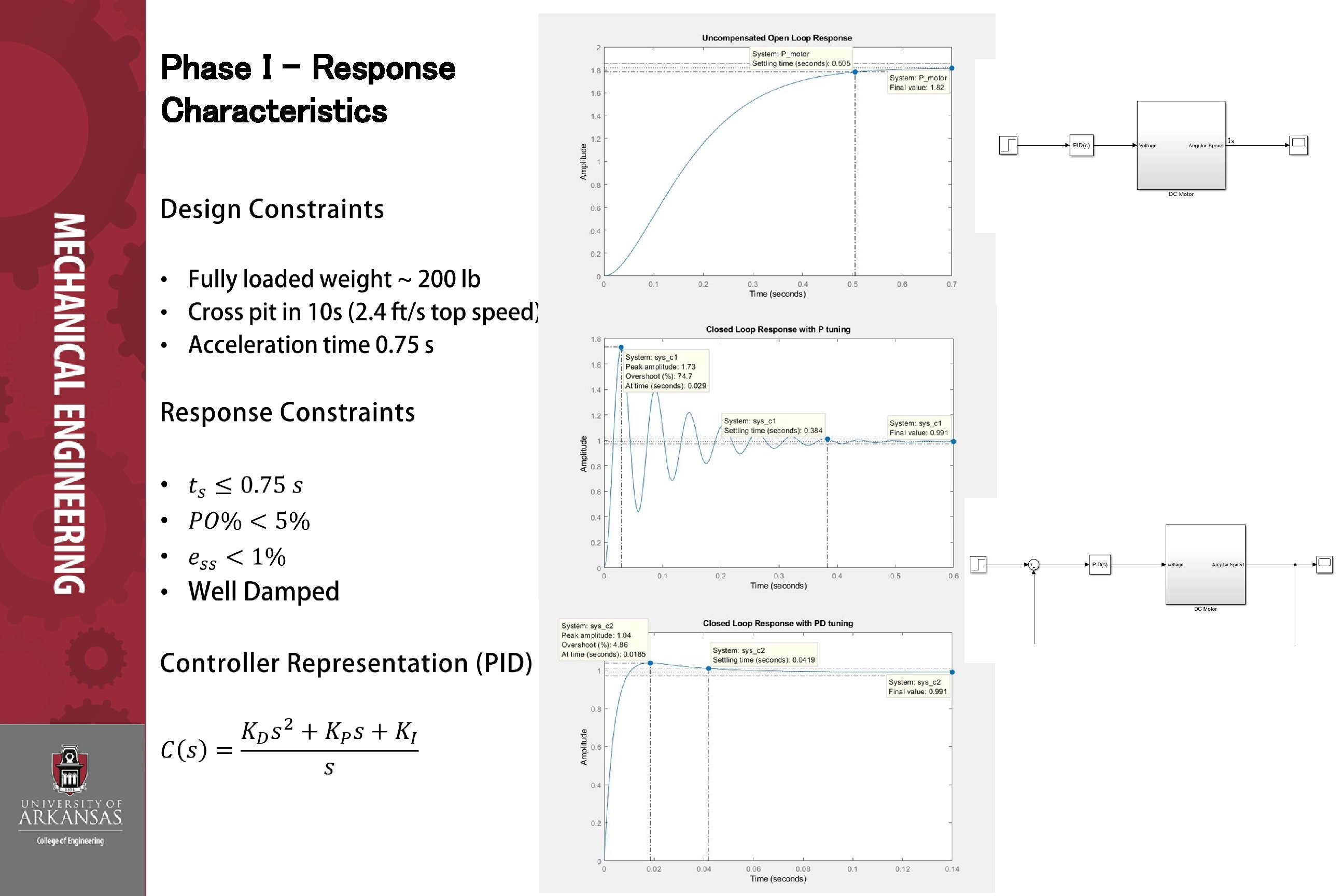

Phase I – The DC Motor

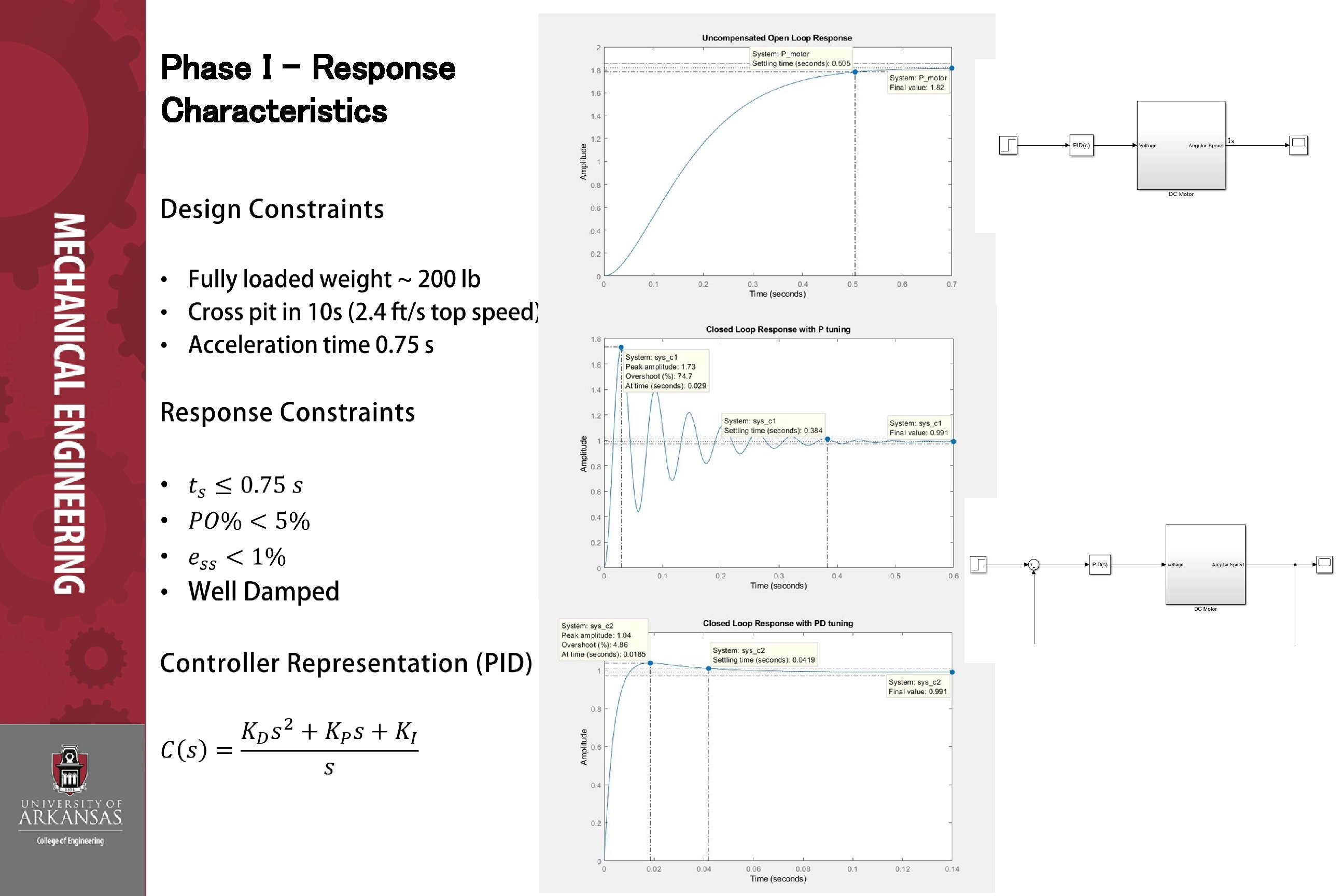

Phase I – Response Characteristics

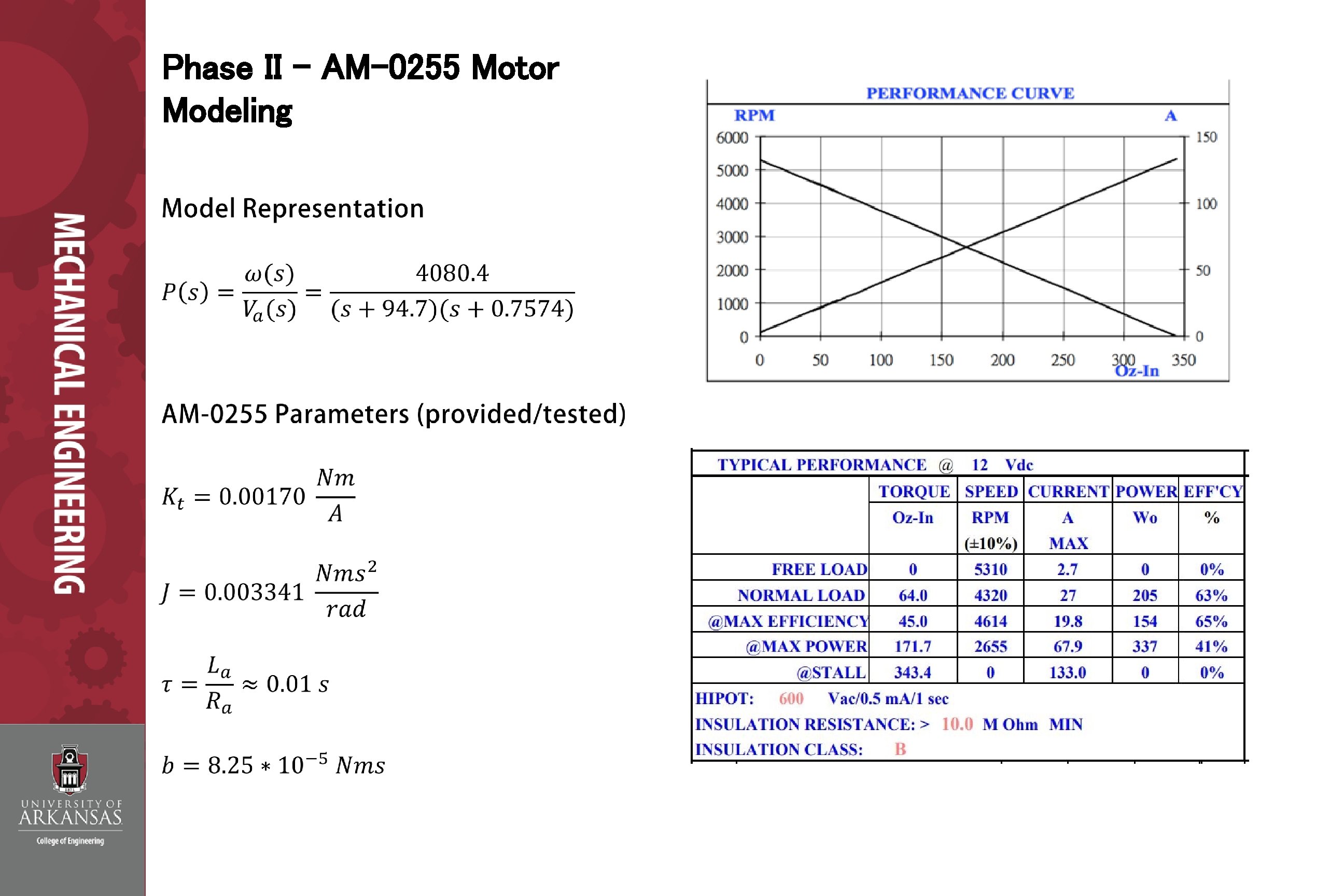

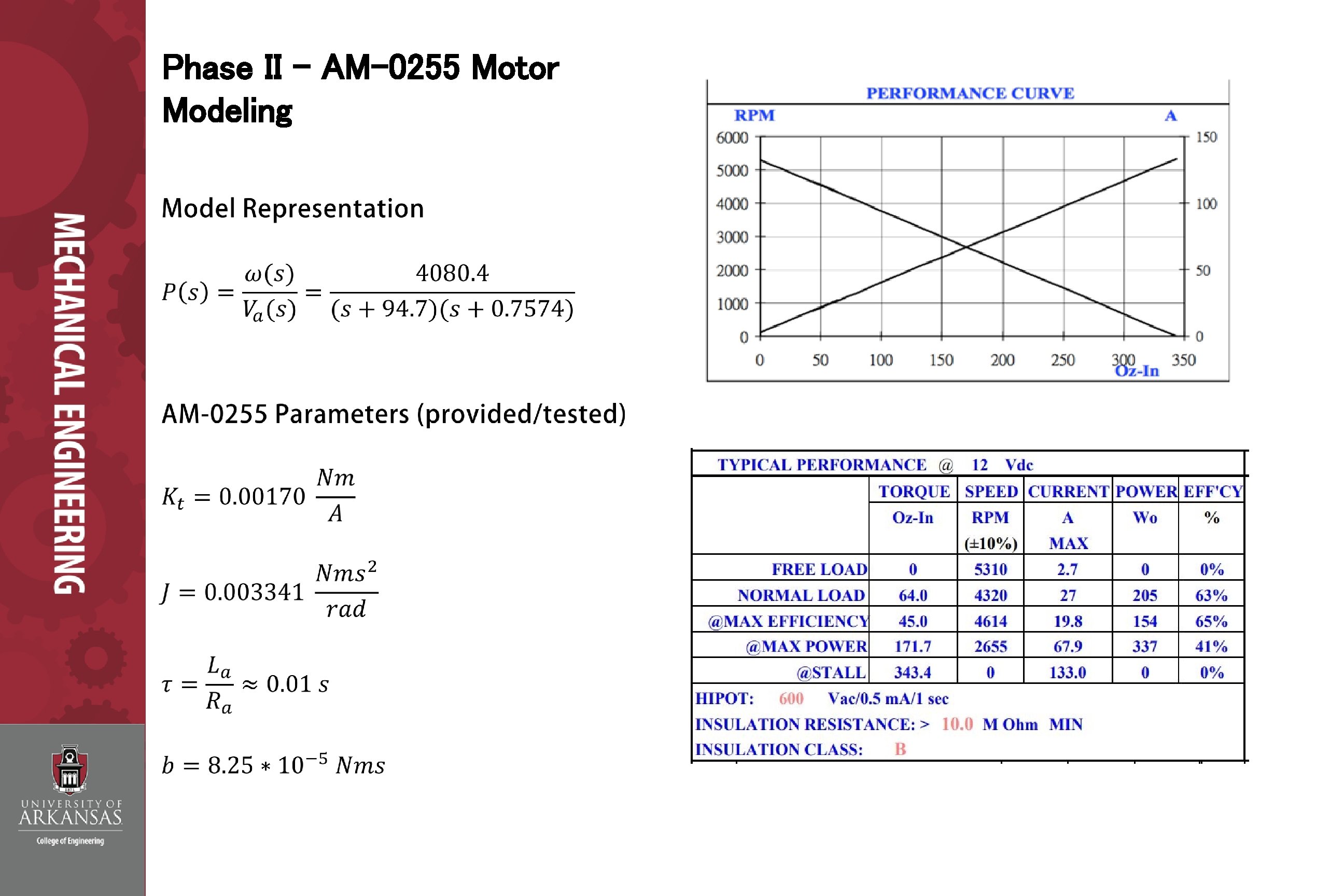

Phase II – AM-0255 Motor Modeling

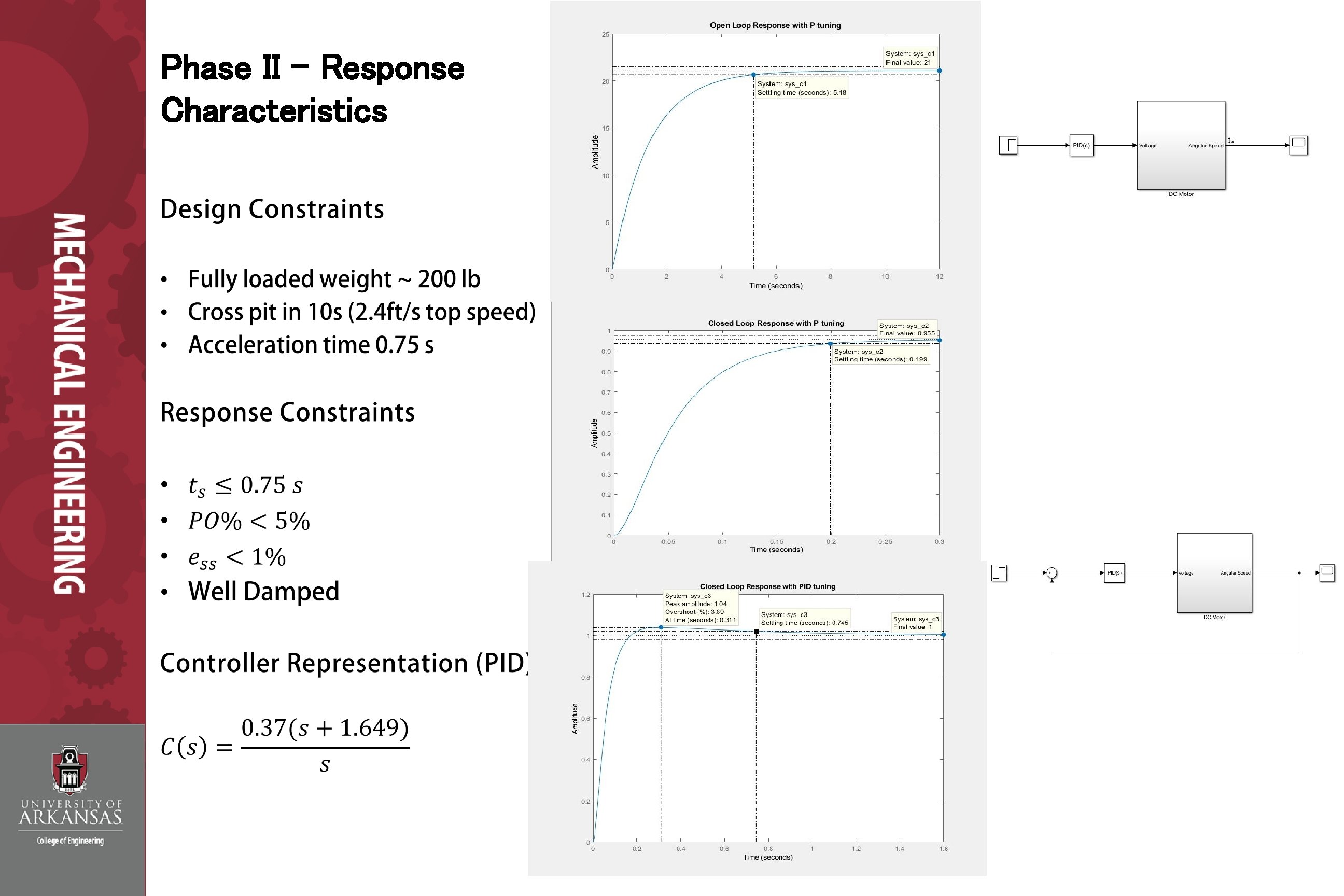

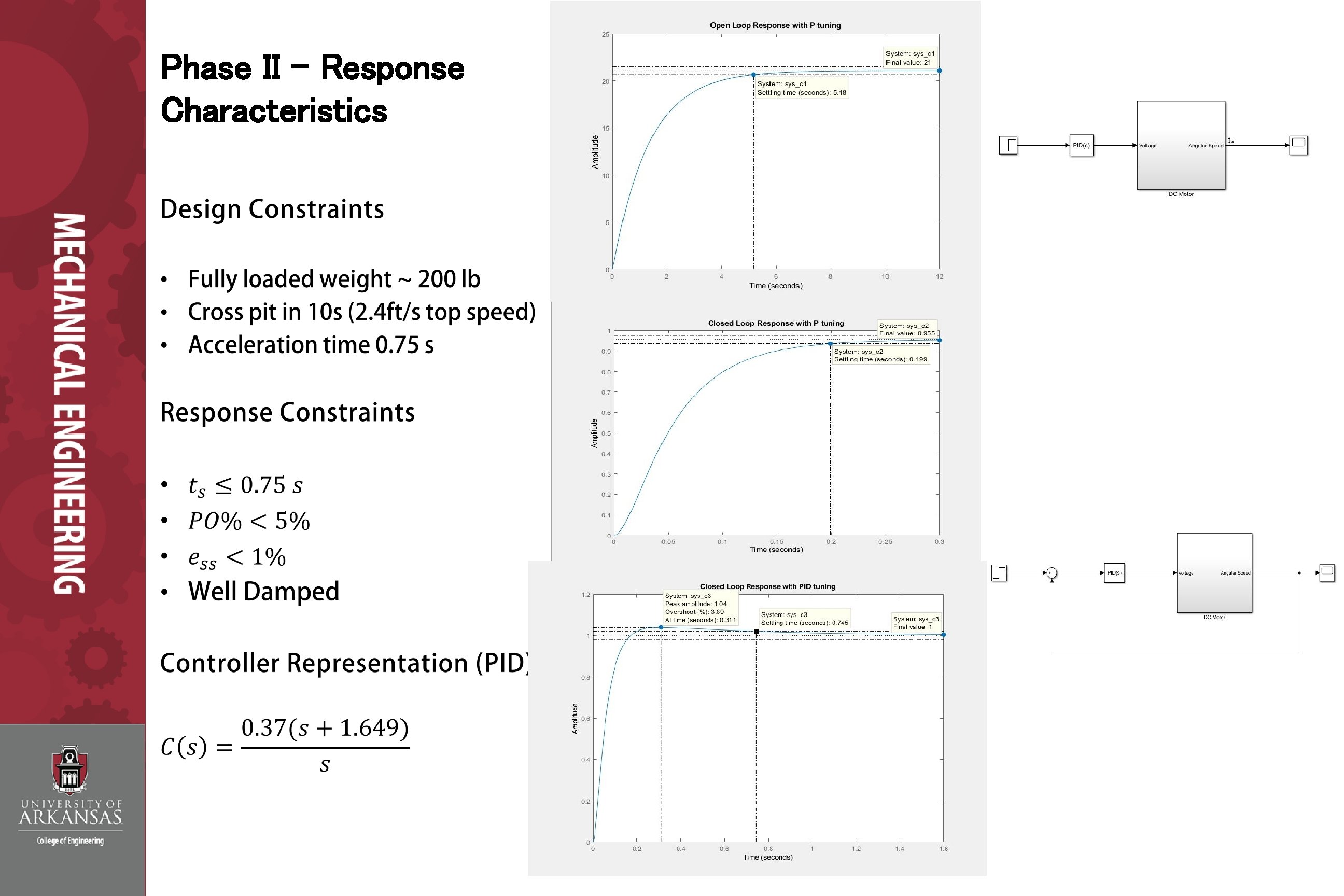

Phase II – Response Characteristics

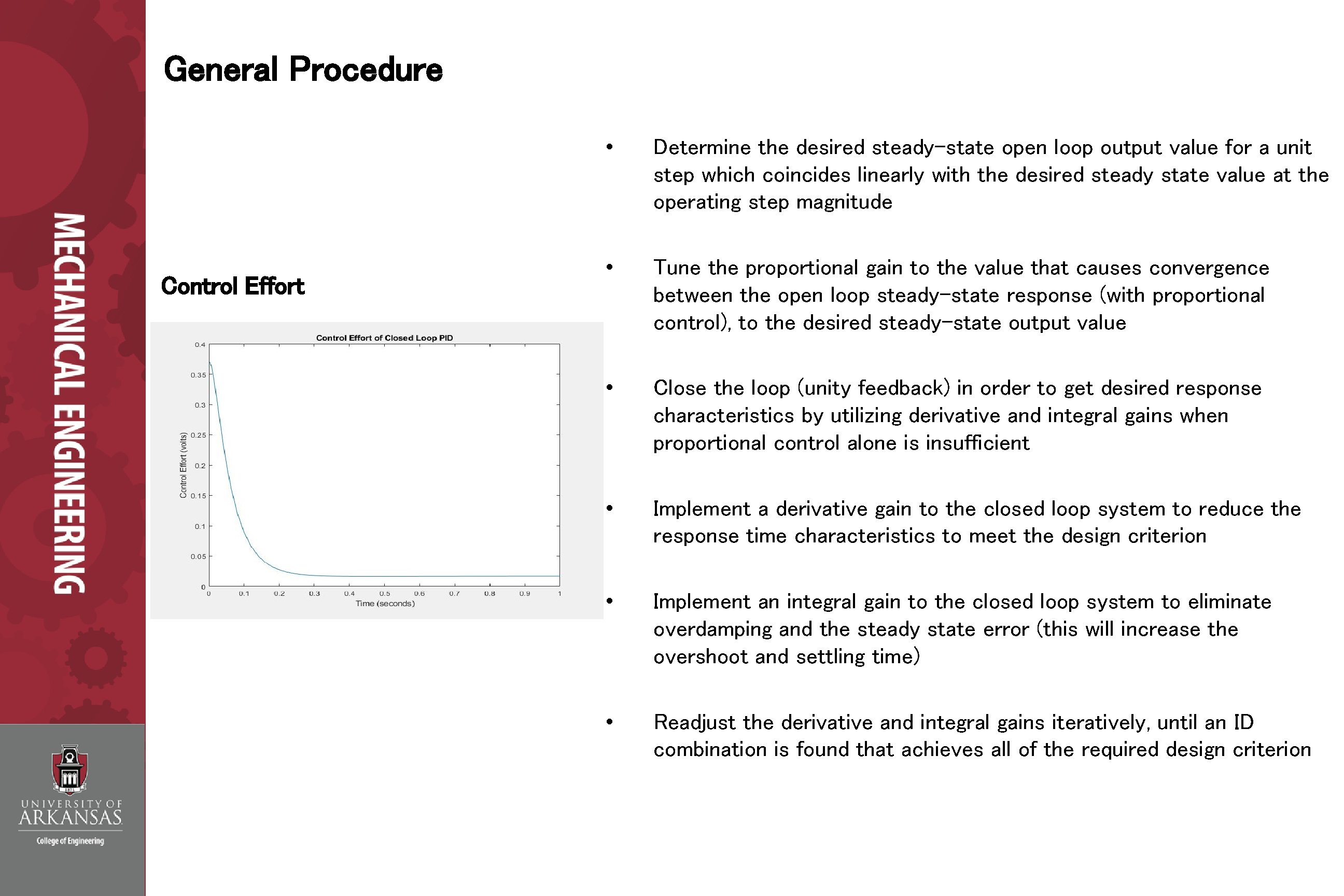

General Procedure Control Effort • Determine the desired steady-state open loop output value for a unit step which coincides linearly with the desired steady state value at the operating step magnitude • Tune the proportional gain to the value that causes convergence between the open loop steady-state response (with proportional control), to the desired steady-state output value • Close the loop (unity feedback) in order to get desired response characteristics by utilizing derivative and integral gains when proportional control alone is insufficient • Implement a derivative gain to the closed loop system to reduce the response time characteristics to meet the design criterion • Implement an integral gain to the closed loop system to eliminate overdamping and the steady state error (this will increase the overshoot and settling time) • Readjust the derivative and integral gains iteratively, until an ID combination is found that achieves all of the required design criterion

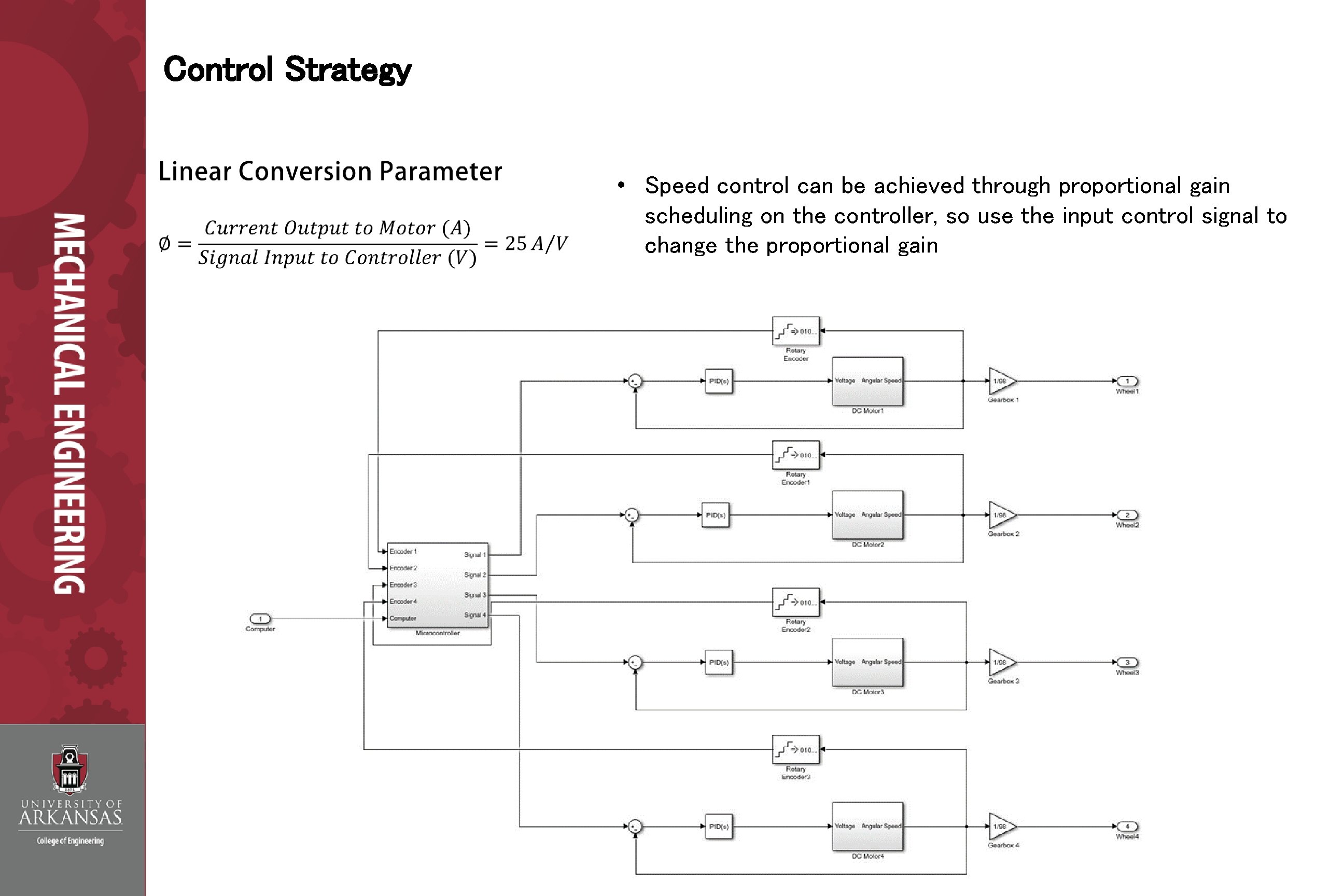

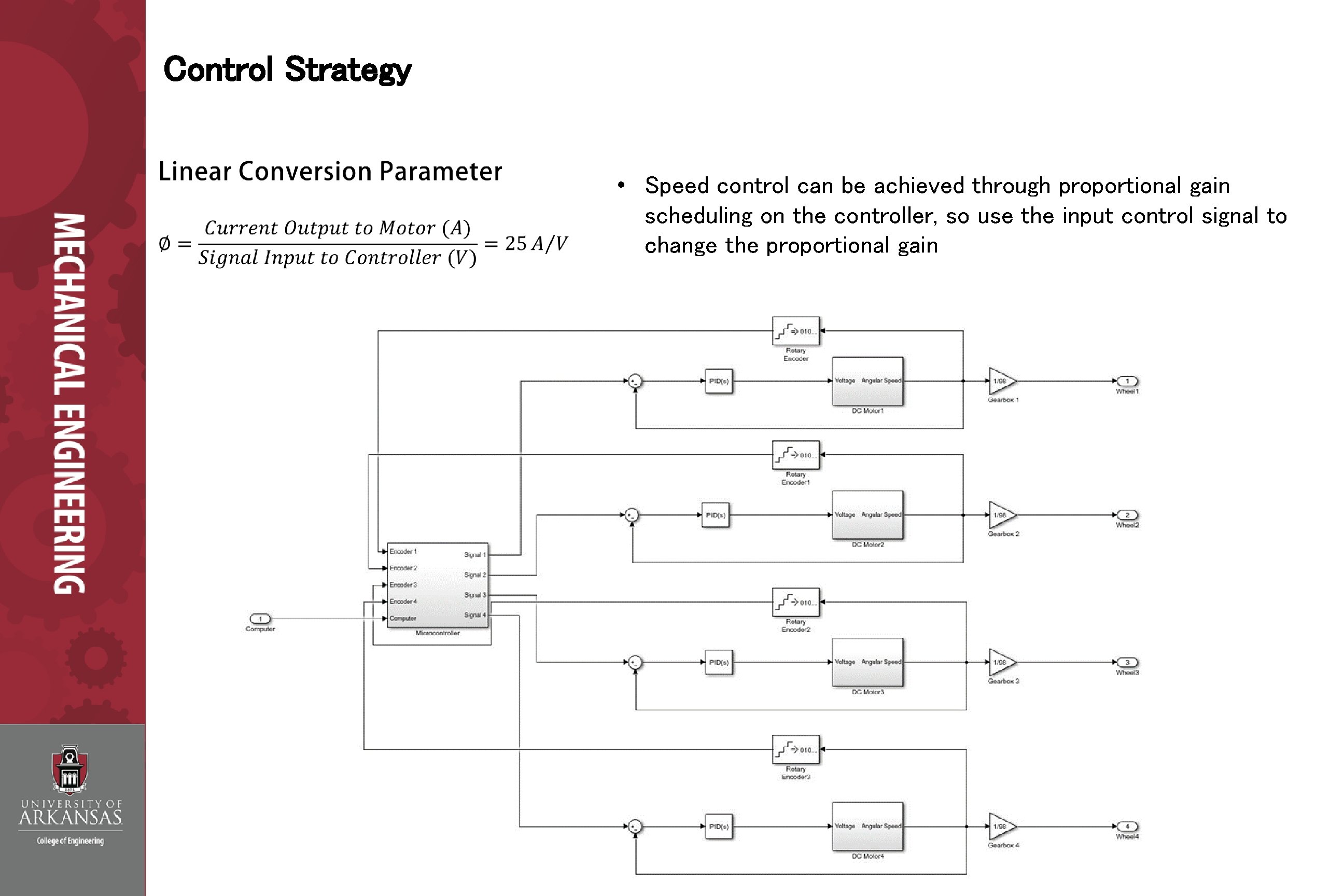

Control Strategy • Speed control can be achieved through proportional gain scheduling on the controller, so use the input control signal to change the proportional gain

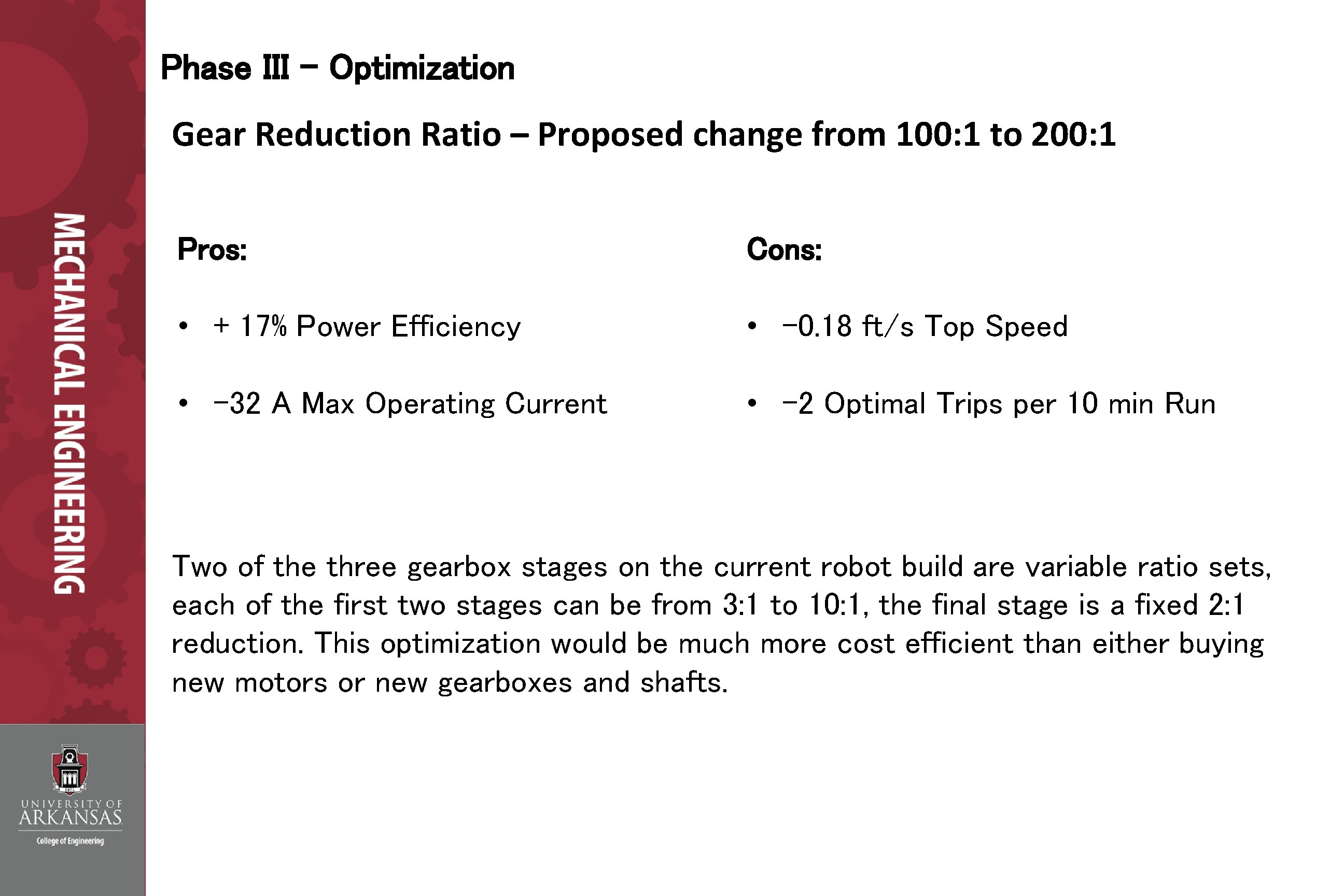

Phase III – Optimization Gear Reduction Ratio – Proposed change from 100: 1 to 200: 1 Pros: Cons: • + 17% Power Efficiency • -0. 18 ft/s Top Speed • -32 A Max Operating Current • -2 Optimal Trips per 10 min Run Two of the three gearbox stages on the current robot build are variable ratio sets, each of the first two stages can be from 3: 1 to 10: 1, the final stage is a fixed 2: 1 reduction. This optimization would be much more cost efficient than either buying new motors or new gearboxes and shafts.

![Phase III Optimization Slip Correction Traction Modeling 7 8 Phase III – Optimization Slip Correction – Traction Modeling [7], [8]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/b9798de18d78dddaa3caafba47947808/image-13.jpg)

Phase III – Optimization Slip Correction – Traction Modeling [7], [8]

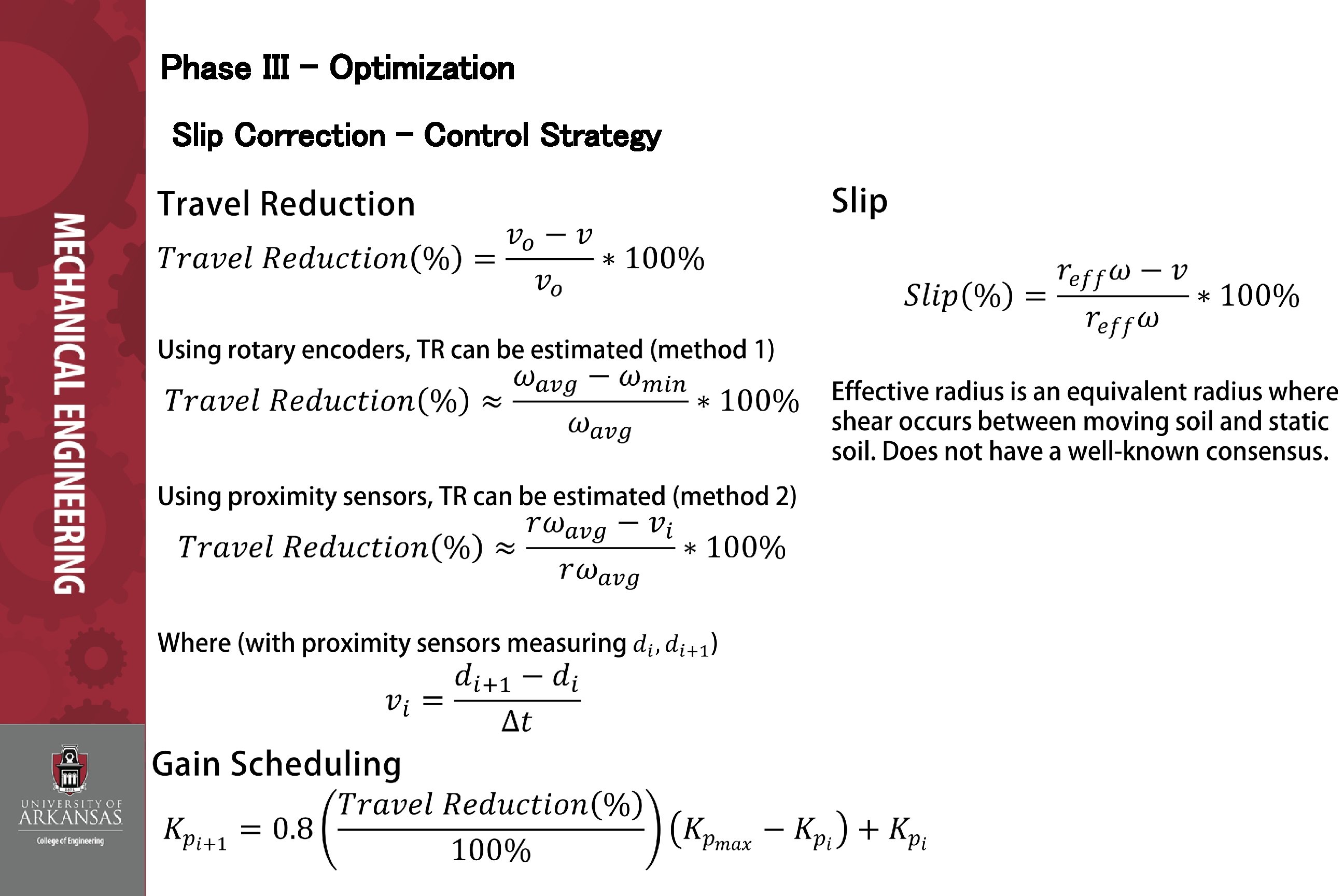

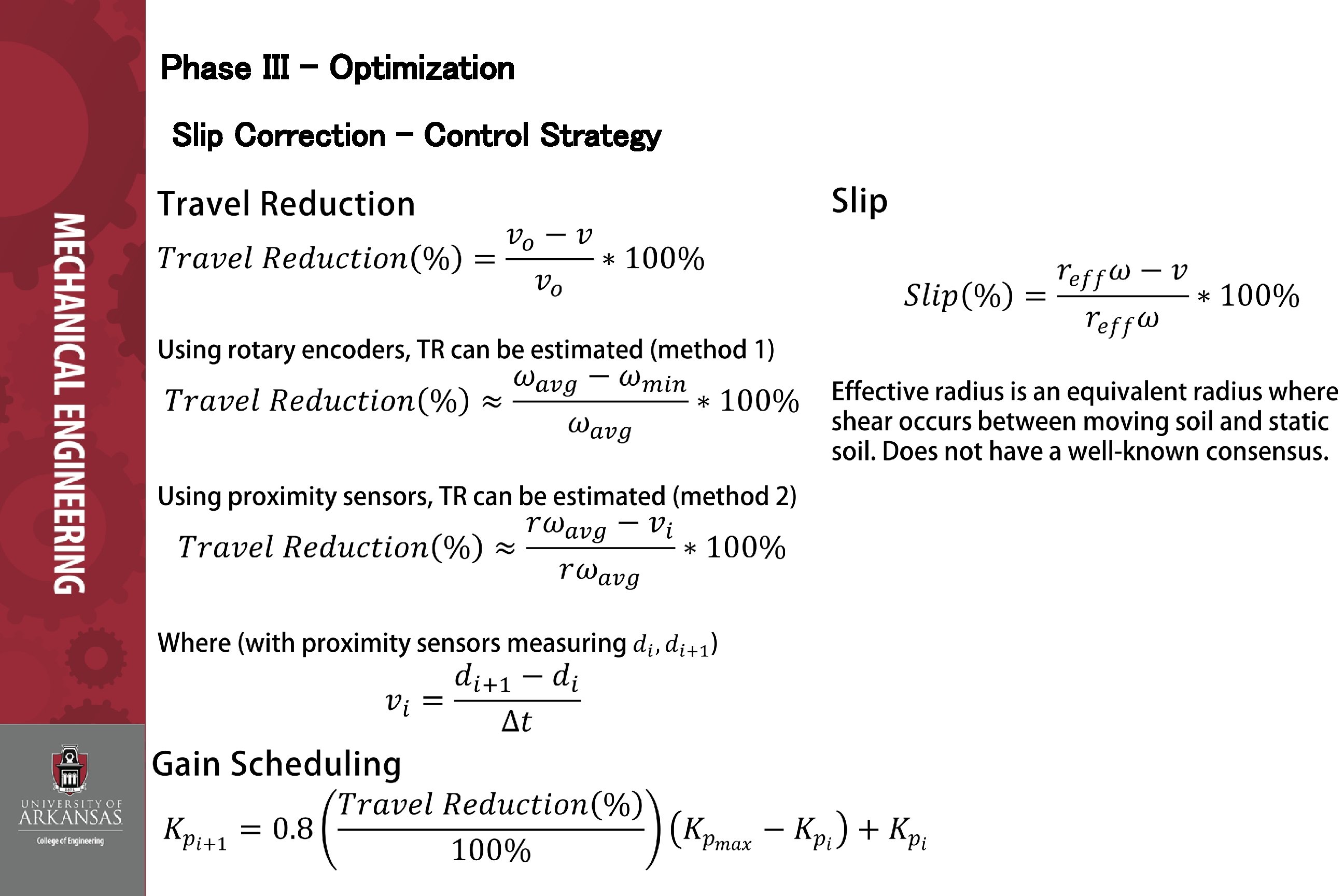

Phase III – Optimization Slip Correction – Control Strategy

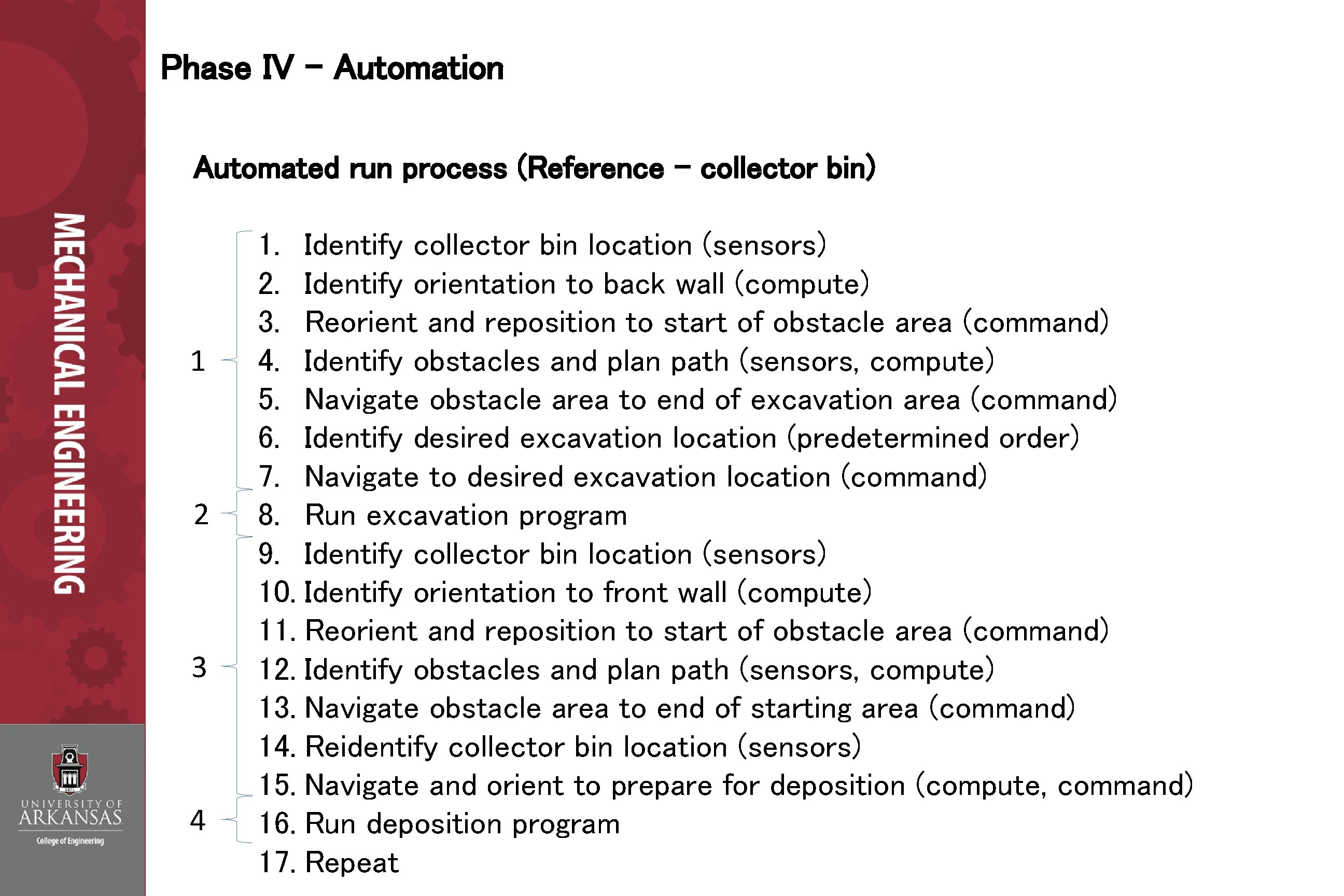

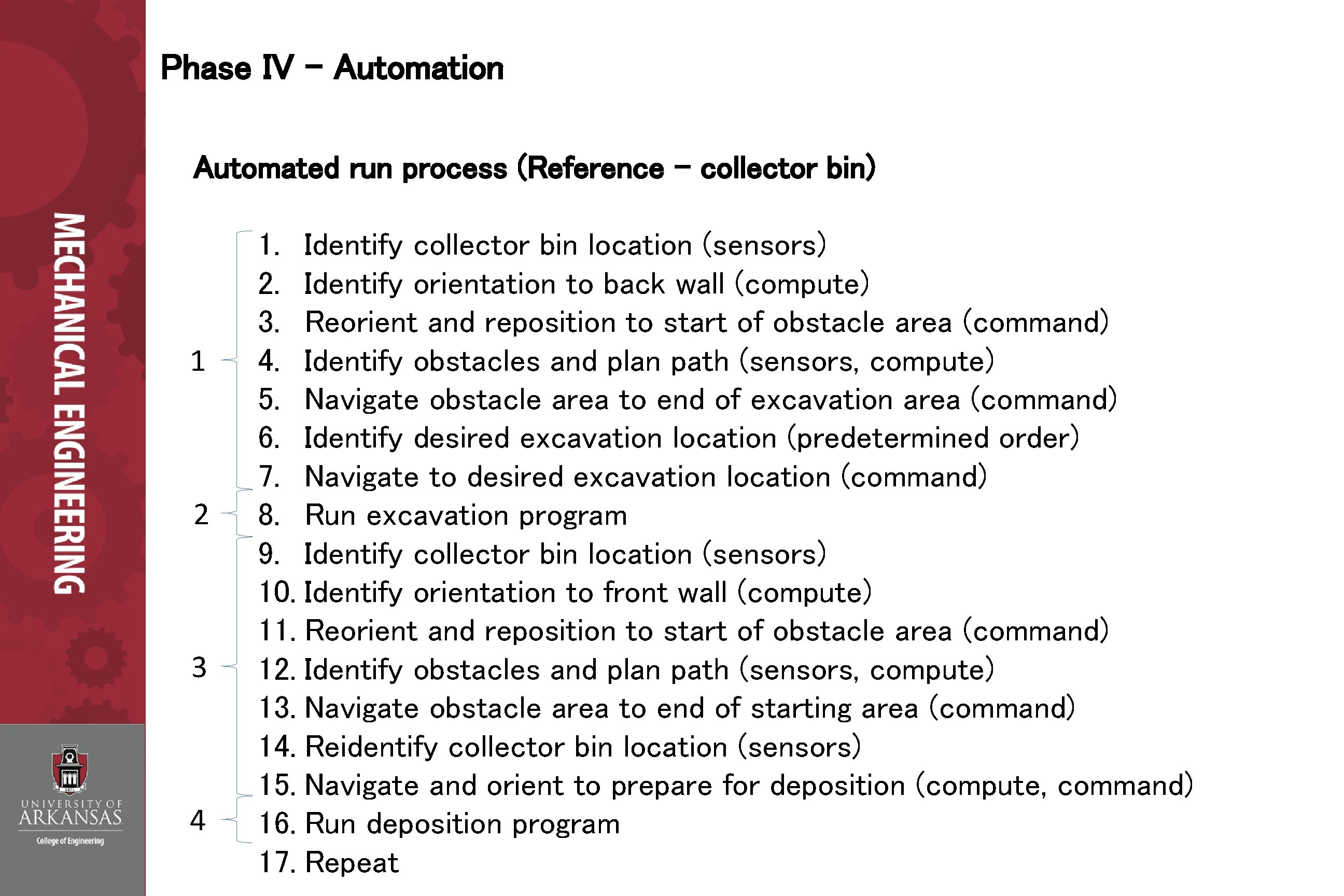

Phase IV – Automation Automated run process (Reference – collector bin) 1 2 3 4 1. Identify collector bin location (sensors) 2. Identify orientation to back wall (compute) 3. Reorient and reposition to start of obstacle area (command) 4. Identify obstacles and plan path (sensors, compute) 5. Navigate obstacle area to end of excavation area (command) 6. Identify desired excavation location (predetermined order) 7. Navigate to desired excavation location (command) 8. Run excavation program 9. Identify collector bin location (sensors) 10. Identify orientation to front wall (compute) 11. Reorient and reposition to start of obstacle area (command) 12. Identify obstacles and plan path (sensors, compute) 13. Navigate obstacle area to end of starting area (command) 14. Reidentify collector bin location (sensors) 15. Navigate and orient to prepare for deposition (compute, command) 16. Run deposition program 17. Repeat

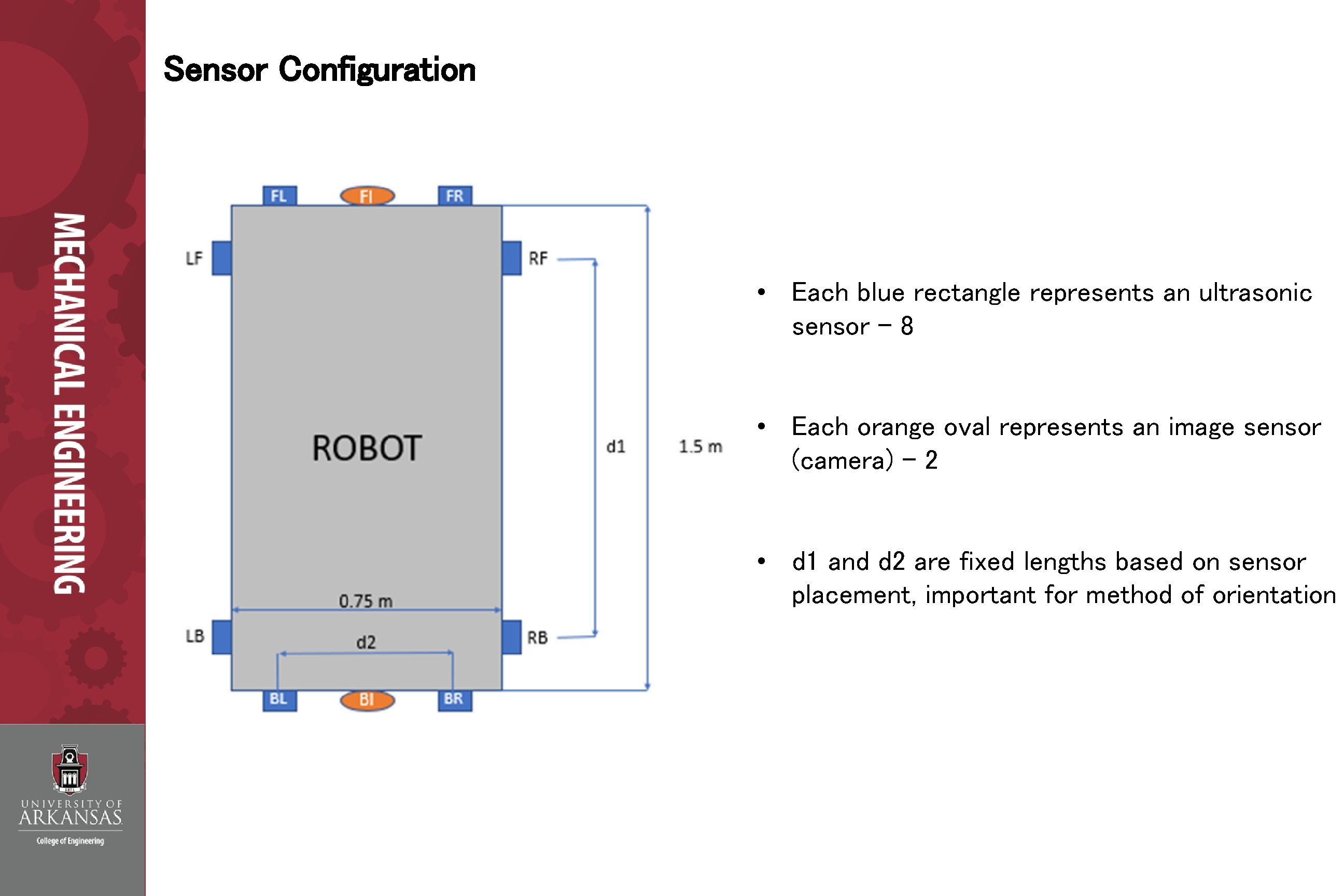

Conditions The following conditions are desired to be maintained for the duration of automated runs: • If any of the eight proximity sensors detects a distance of less than 1 meter, the robot must not rotate in such a way that it will bring a corner of two of its sides towards that measured distance point. It will always be working to: • Reduce the magnitude of the angle measured between a robot side and the closest proximity wall • Drive towards the direction of the largest measured distance to a wall • The algorithm should be constructed in such a way that the robot should default to using the two adjacent sides which have the least proximity distance measurements to the certain walls in question when running an orientation command • The robot can use proximity sensor measurements and triangulation to determine its actual straightline distance travelled over a discrete time interval. This measurement can be directly implemented into Method 2 of the slip correction strategies previously discussed in Phase III • Two sensors on a given robot side must be placed symmetrically about the robots geometrical center with respect to that side.

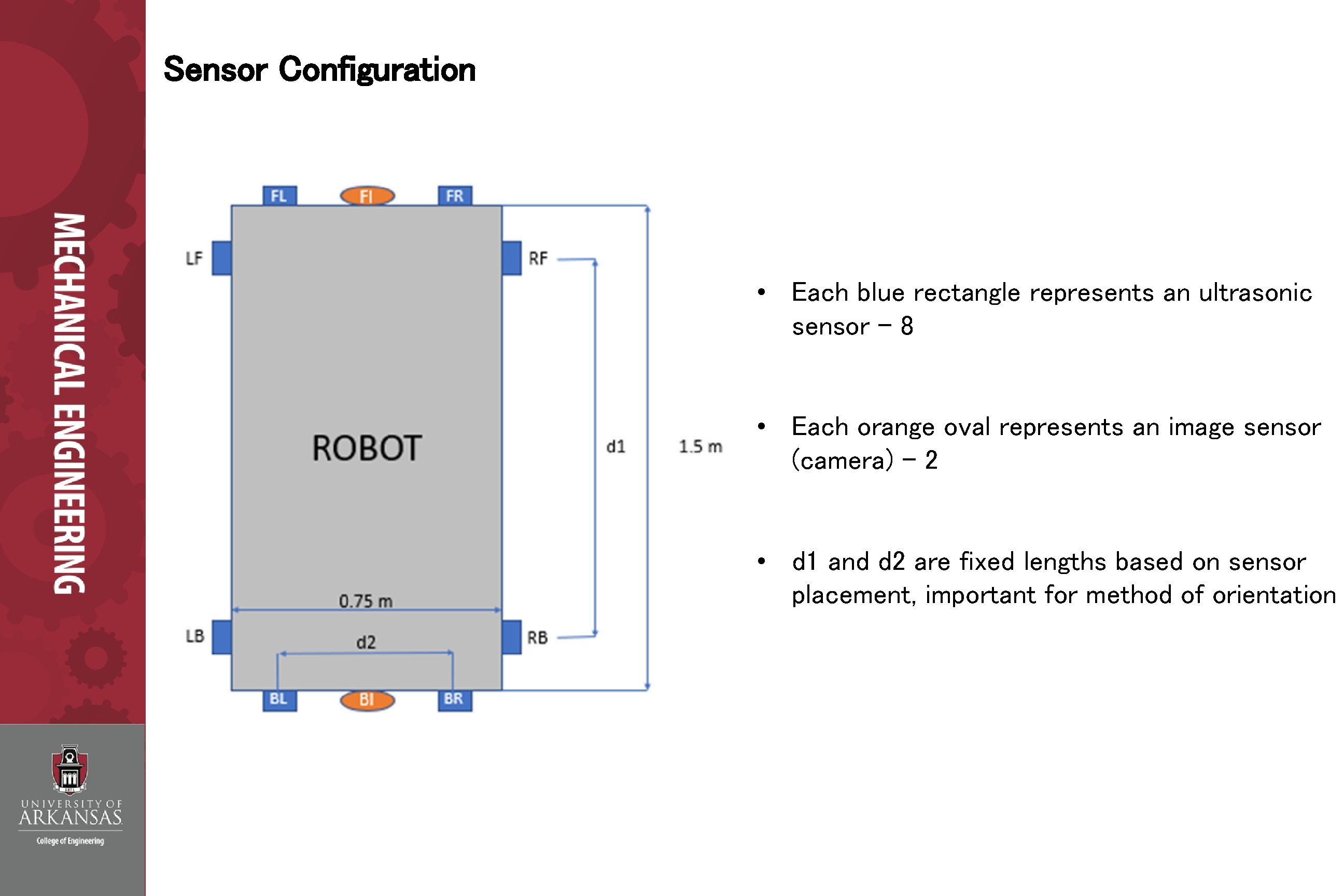

Sensor Configuration • Each blue rectangle represents an ultrasonic sensor – 8 • Each orange oval represents an image sensor (camera) – 2 • d 1 and d 2 are fixed lengths based on sensor placement, important for method of orientation

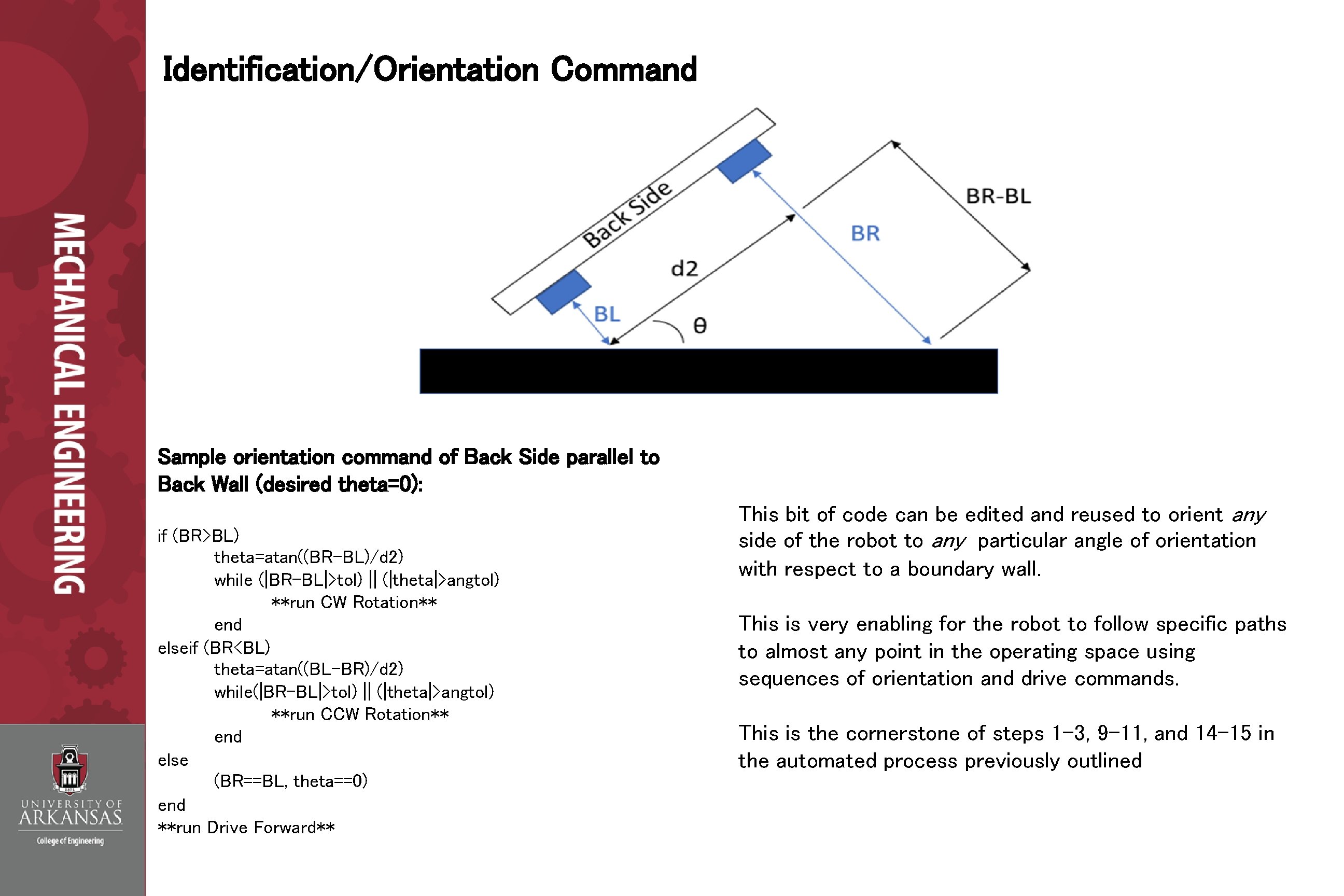

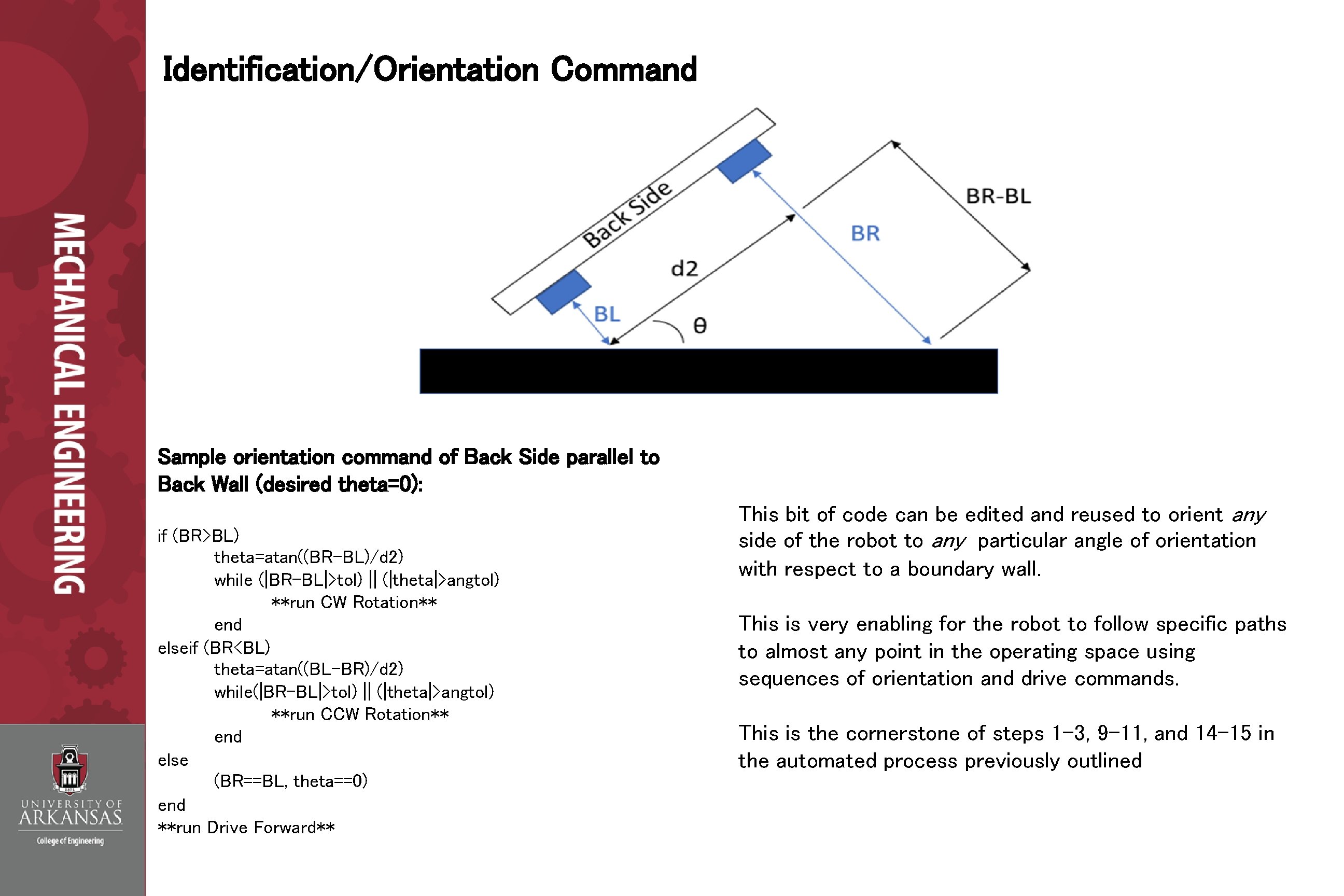

Identification/Orientation Command Sample orientation command of Back Side parallel to Back Wall (desired theta=0): if (BR>BL) theta=atan((BR-BL)/d 2) while (|BR-BL|>tol) || (|theta|>angtol) **run CW Rotation** end elseif (BR<BL) theta=atan((BL-BR)/d 2) while(|BR-BL|>tol) || (|theta|>angtol) **run CCW Rotation** end else (BR==BL, theta==0) end **run Drive Forward** This bit of code can be edited and reused to orient any side of the robot to any particular angle of orientation with respect to a boundary wall. This is very enabling for the robot to follow specific paths to almost any point in the operating space using sequences of orientation and drive commands. This is the cornerstone of steps 1 -3, 9 -11, and 14 -15 in the automated process previously outlined

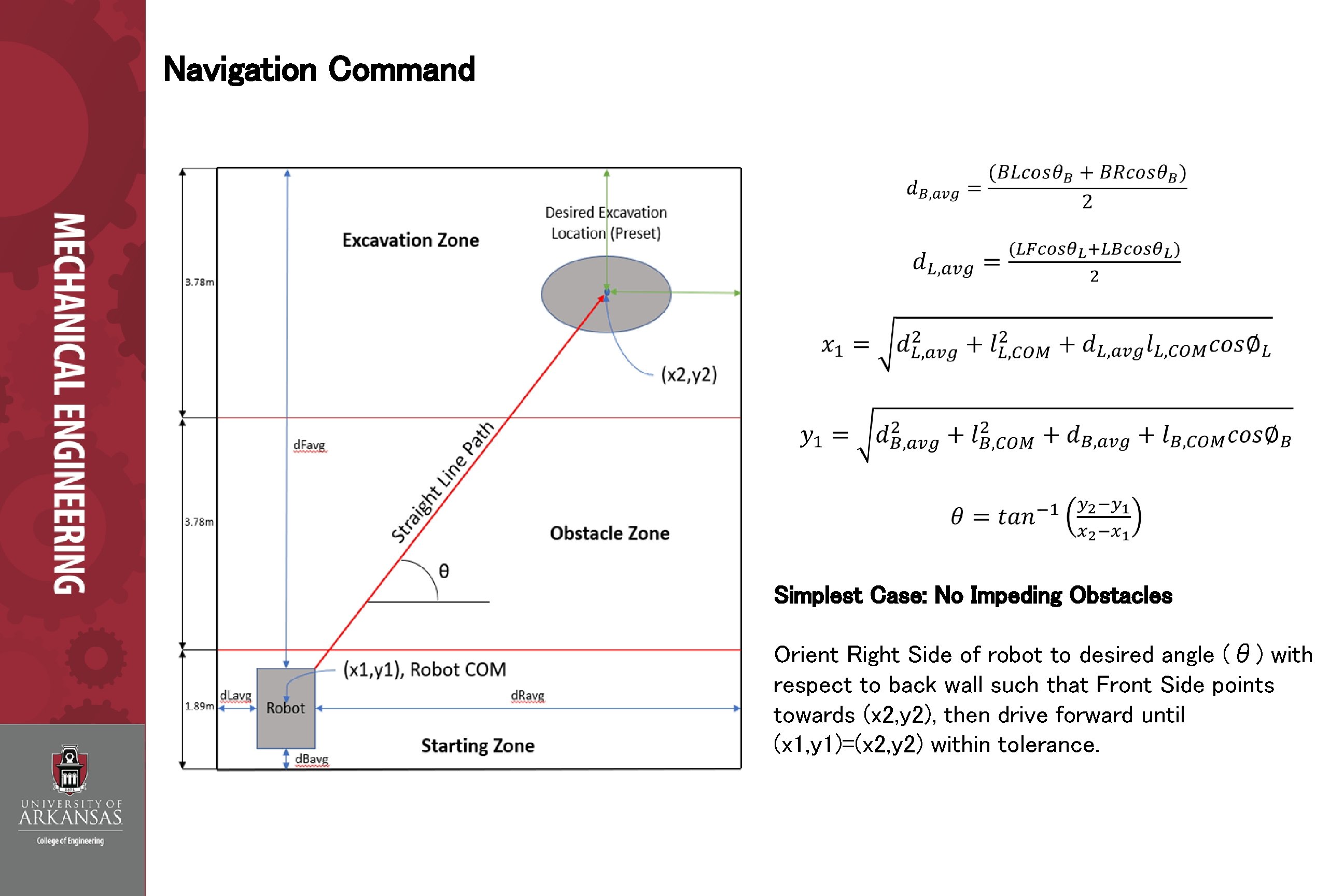

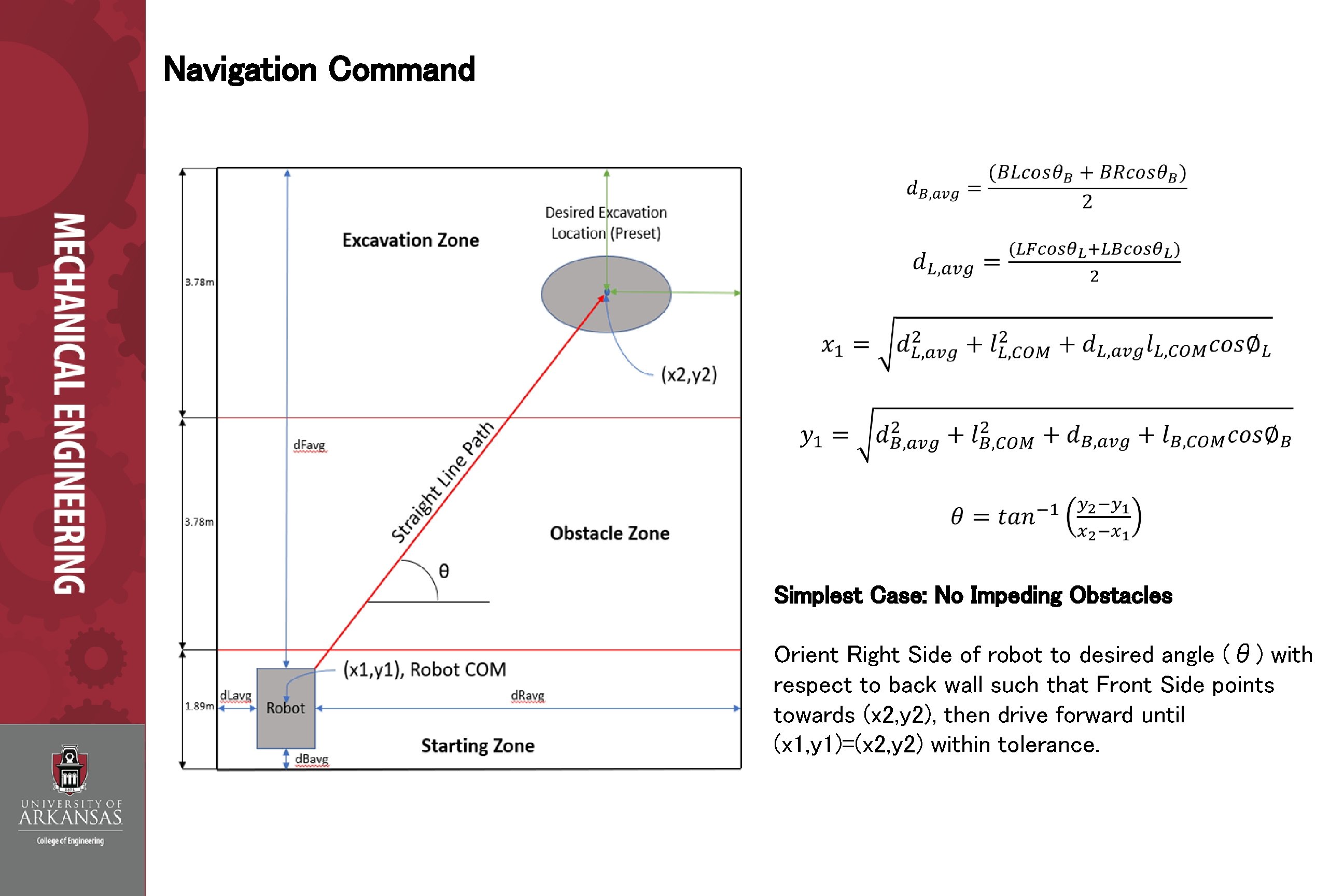

Navigation Command Simplest Case: No Impeding Obstacles Orient Right Side of robot to desired angle (θ) with respect to back wall such that Front Side points towards (x 2, y 2), then drive forward until (x 1, y 1)=(x 2, y 2) within tolerance.

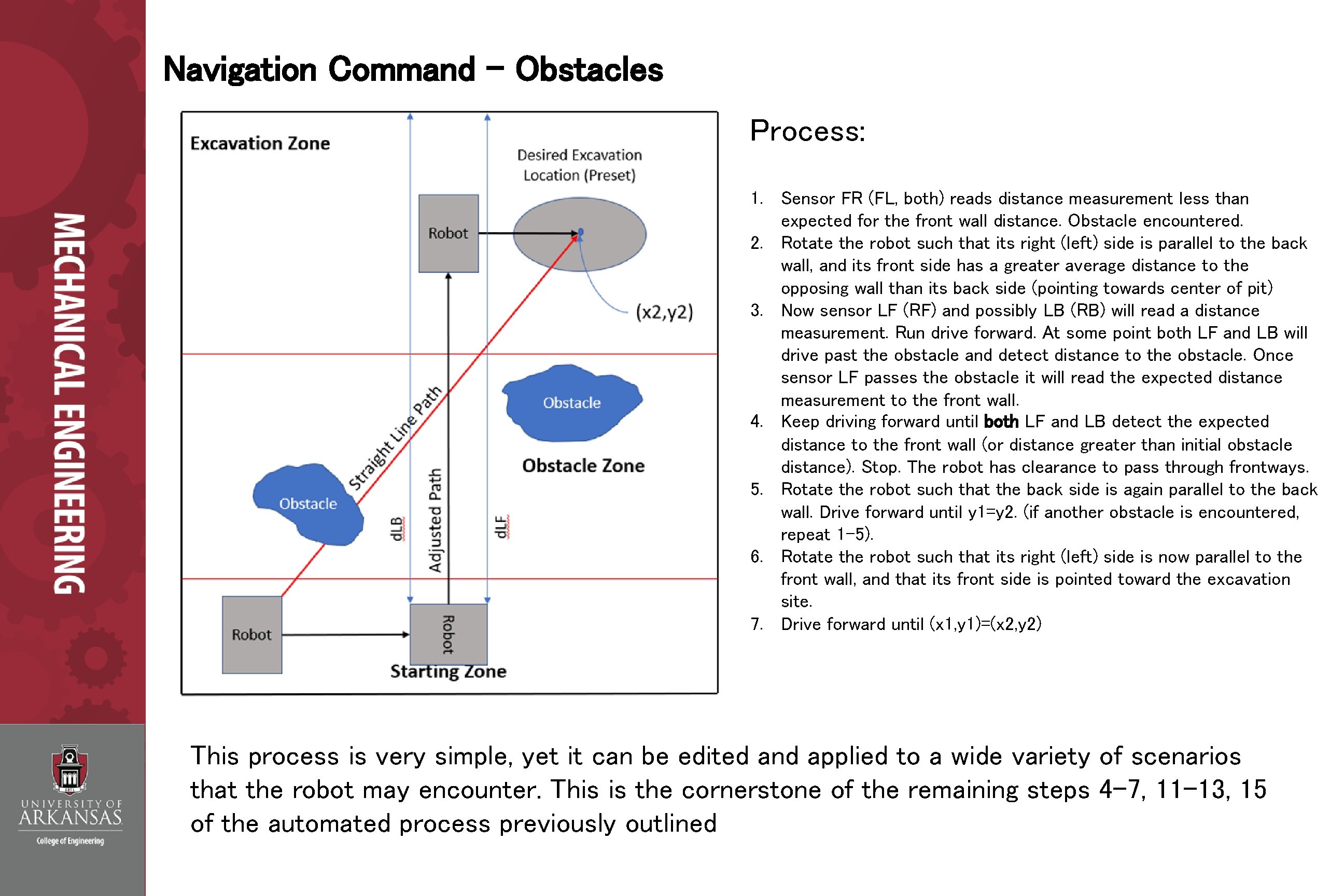

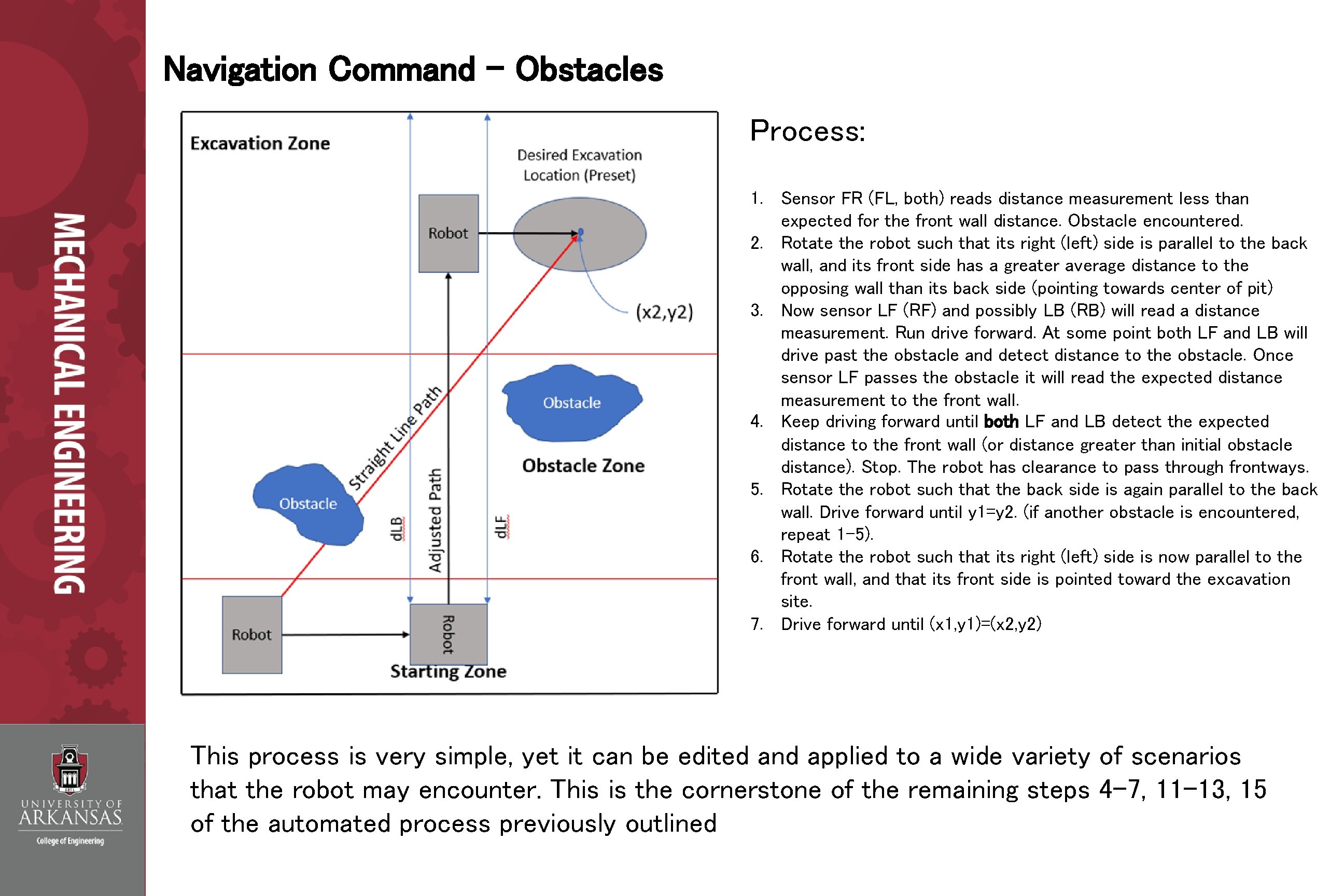

Navigation Command - Obstacles Process: 1. Sensor FR (FL, both) reads distance measurement less than expected for the front wall distance. Obstacle encountered. 2. Rotate the robot such that its right (left) side is parallel to the back wall, and its front side has a greater average distance to the opposing wall than its back side (pointing towards center of pit) 3. Now sensor LF (RF) and possibly LB (RB) will read a distance measurement. Run drive forward. At some point both LF and LB will drive past the obstacle and detect distance to the obstacle. Once sensor LF passes the obstacle it will read the expected distance measurement to the front wall. 4. Keep driving forward until both LF and LB detect the expected distance to the front wall (or distance greater than initial obstacle distance). Stop. The robot has clearance to pass through frontways. 5. Rotate the robot such that the back side is again parallel to the back wall. Drive forward until y 1=y 2. (if another obstacle is encountered, repeat 1 -5). 6. Rotate the robot such that its right (left) side is now parallel to the front wall, and that its front side is pointed toward the excavation site. 7. Drive forward until (x 1, y 1)=(x 2, y 2) This process is very simple, yet it can be edited and applied to a wide variety of scenarios that the robot may encounter. This is the cornerstone of the remaining steps 4 -7, 11 -13, 15 of the automated process previously outlined

Future Work • Build practice run pit. Motor control optimization comes hand in hand with real testing. Determine difference between optimal number of trips per ten-minute run and actual trips the robot is capable of performing. This would indicate opportunities for optimization. • Can use test pit to help verify or revise and improve the strategies presented for slip correction. Can also use to test the validity of the automation strategy as well as revise to account for as many scenarios the robot may encounter as possible. • Need several iterations of custom motor control boards to be manufactured and tested on the robot build to verify or revise the process of the PID tuning method proposed.

![References 1 Heiney A Ed 2018 April 27 NASAs Ninth Annual Robotic Mining References [1] Heiney, A. (Ed. ). (2018, April 27). NASA’s Ninth Annual Robotic Mining](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/b9798de18d78dddaa3caafba47947808/image-22.jpg)

References [1] Heiney, A. (Ed. ). (2018, April 27). NASA’s Ninth Annual Robotic Mining Competition: Rules and Rubrics. Retrieved May 10, 2018, from https: //www. nasa. gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/2018_rules_rubrics_parti. pdf [2] Bishop, R. H. , & Dorf, R. C. (2011). Modern Control Systems (12 th ed. ). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. [3] Introduction: PID Controller Design. (n. d. ). Retrieved May 10, 2018, from http: //ctms. engin. umich. edu/CTMS/index. php? example=Introduction§ion=Control. PID [4] Loseke, Barrett (2018). RMC Independent Study: Summer 2018. Submitted August 5, 2018. [5] Massouda, N. (2018, July 11). Re: 2. 5 CIM Motor Question: 4244 [E-mail to the author]. Andy. Mark Inc. [6] DC Motor Speed: Simulink Modeling. (n. d. ). Retrieved May 12, 2018, from http: //ctms. engin. umich. edu/CTMS/index. php? example=Motor. Speed§ion=Simulink. Modeling [7] Skonieczny, K. (2013). Lightweight Robotic Excavation. Carnegie Mellon University. 51 -71. [8] Mieczyslaw Gregory Bekker (1969). Introduction to terrain-vehicle systems. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. [9] Pavone, M. , Acikmese, B. , Nesnas, I. A. , & Starek, J. (2014). Spacecraft Autonomy Challenges for Next Generation Space Missions [Scholarly project]. Retrieved April 8, 2019, from https: //web. stanford. edu/~pavone/papers/Pavone. Acikmese. ea. LNS 14. pdf [10] Parrish, L. , “Regolith Advanced Surface Systems Operations Robot (RASSOR) Excavator, ” NASA Technology Transfer Program, pp. 1 -2, Mar. 2013 [11] Motor Specifications FR 801 -001. (n. d. ). Retrieved May, 2017, from files. andymark. com/CIM-motor-curve. pdf. CCL Industrial Motor Limited (CIM). [12] Technical Specifications. (n. d. ). Retrieved August, 2018, from https: //www. themartiangarden. com/tech-specs. MMS-1 Specifications

Acknowledgements I would like to thank and recognize the University of Arkansas for providing the opportunity for research and involvement in the NASA RMC. Thank you to the faculty lead advisor for the competition and for robotics research for the department, Dr. Uche Wejinya. Thank you to the members of the University of Arkansas undergraduate RMC design-build team. Thank you to my summer 2018 understudy Barrett Loseke, who was a primary contributor to this report. Thank you to my research partners pertaining to the work on the excavation system, Ryan Watson and Chris Taylor.