Monopolistic Competition Oligopoly and Strategic Pricing Chapter 13

- Slides: 60

Monopolistic Competition, Oligopoly, and Strategic Pricing Chapter 13 © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited.

13 - 2 Introduction u In discussing real-world competition, the focus quickly becomes market structure. u Market structure refers to the physical characteristics of the market within which firms interact. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 3 Introduction u Market structure involves the number of firms in the market and the barriers to entry. u Perfect competition, with an infinite number of firms, and monopoly, with a single firm, are polar opposites. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 4 Introduction u Monopolistic competition and oligopoly lie between these two extremes. Monopolistic competition is a market structure in which there are many firms selling differentiated products. l Oligopoly is a market structure in which there a few interdependent firms. l © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 5 Introduction to Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly u The number of firms in an industry plays an important role in determining whether firms explicitly take other firms’ actions into account. l Oligopolies take into account the reactions of other firms; monopolistic competitors do not. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 6 Introduction to Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly u In monopolistic competition, there are so many firms that firms do not take into account their rivals’ responses to their decisions. u Collusion is difficult due to a large number of firms. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 7 Introduction to Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly u In oligopoly, there are only a few firms and each firm is more likely to engage in strategic decision making. u Strategic decision making – taking explicit account of a rival’s expected response to a decision one is making. u In oligopoly, few firms can collude relatively easily. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 8 Monopolistic Competition u The four distinguishing characteristics of monopolistic competition are: Many sellers. l Differentiated products. l Multiple dimensions of competition. l Easy entry of new firms in the long run. l © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 9 Many Sellers u There are many sellers in monopolistic competition, but each of them is able to identify its own small market segment. u Monopolistically competitive firms act independently of its rivals. u The existence of many sellers also makes collusion difficult. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 10 Differentiated Products u The “many sellers” characteristic gives monopolistic competition its competitive aspect. u Its monopolistic aspect comes from product differentiation. u In a monopolistically competitive market competitors produce many close substitutes. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 11 Differentiated Products u Differentiation may be based on real differences in product characteristics, or can be based on consumers’ perceptions about product differences. u Generally, monopolistic competition is characterized by significant expenditures on advertising, which acts as an important barrier to entry. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 12 Differentiated Products u Any industry where brand proliferation is present is likely to be monopolistically competitive. l Some examples are soap, jeans, cookies and games. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 13 Multiple Dimensions of Competition u Competition takes many forms in a monopolistically competitive industry: Product differentiation. l Perceived quality. l Competitive advertising. l Service and distribution outlets. l © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 14 Easy Entry of New Firms in the Long Run u There are no significant barriers to entry in monopolistic competition. u The existence of economic profits induces other firms to enter, bringing long-run profit down to zero. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

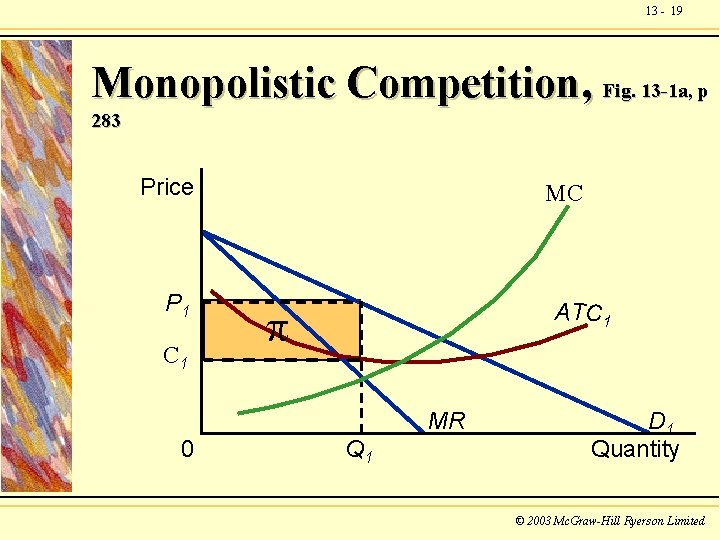

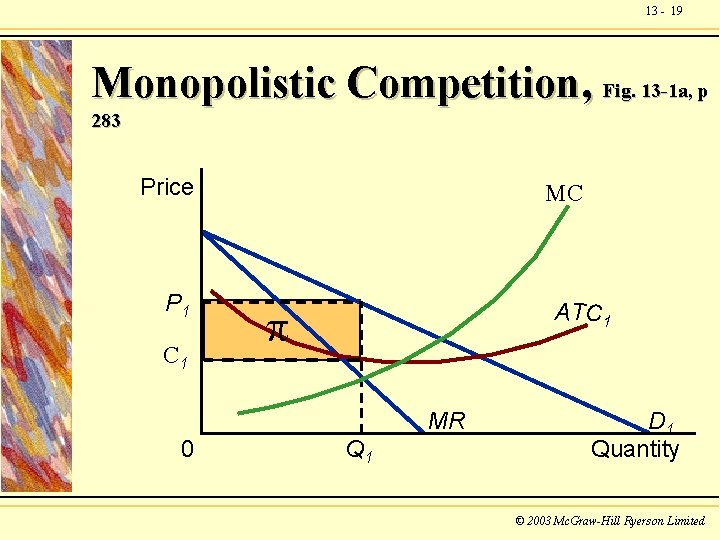

13 - 15 Output, Price, and Profit of a Monopolistic Competitor u. A monopolistically competitive firm produces in the same manner as a monopolist—to maximize profit, it chooses the quantity where MC = MR. u Having determined output, the firm will charge what consumers are willing to pay (determined by the demand curve). © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

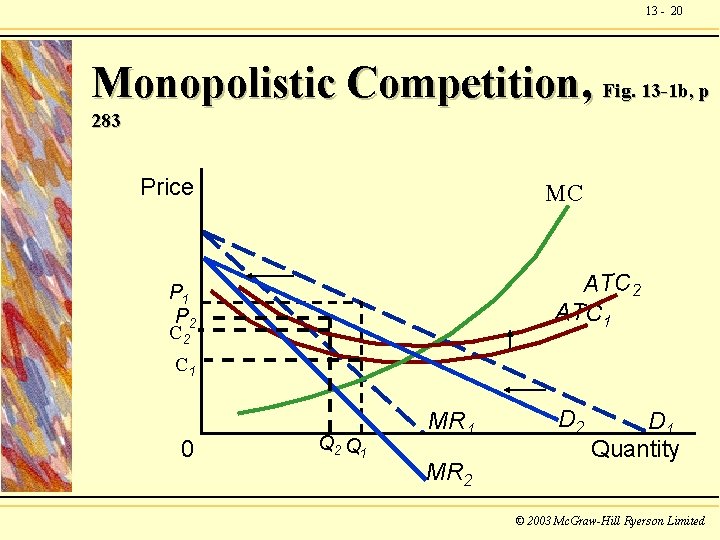

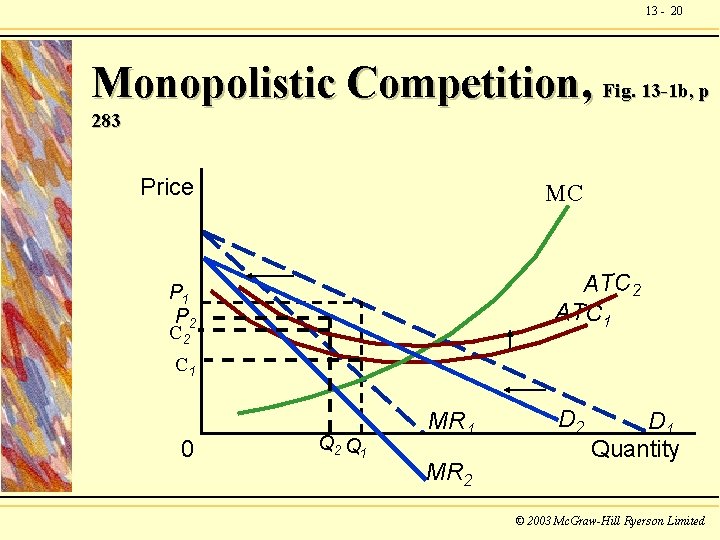

13 - 16 Output, Price, and Profit of a Monopolistic Competitor u If price exceeds ATC, the firm will earn positive economic profits. u These profits attract entry. u Some customers of the existing firms switch to become customers of the new firm. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

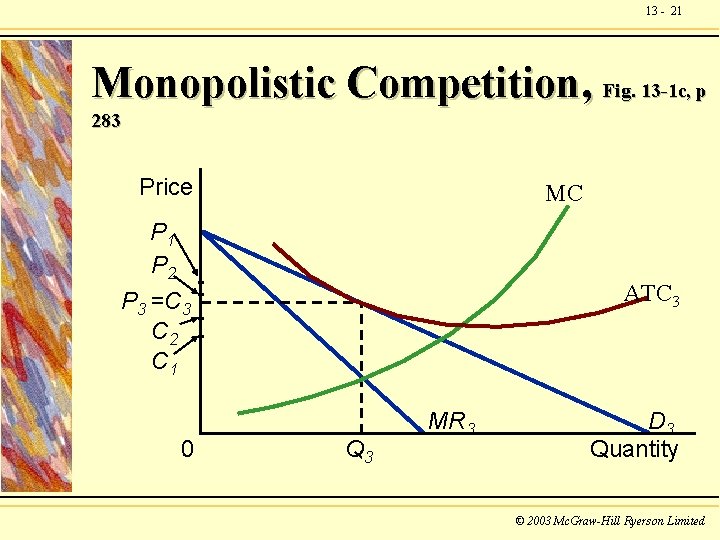

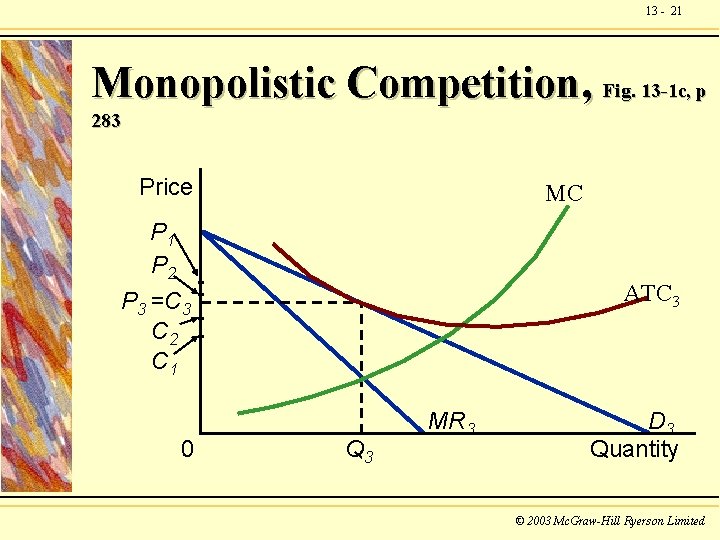

13 - 17 Output, Price, and Profit of a Monopolistic Competitor u Entry causes the existing firm’s demand curve to shift left (decrease) as it loses customers. u Competition, therefore, implies zero economic profit in the long run. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 18 Output, Price, and Profit of a Monopolistic Competitor u At the long run equilibrium, ATC equals price and economic profits are zero. u This occurs at the point of tangency of the ATC and demand curve at the output chosen by the firm. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 19 Monopolistic Competition, Fig. 13 -1 a, p 283 Price P 1 C 1 MC ATC 1 MR 0 Q 1 D 1 Quantity © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 20 Monopolistic Competition, Fig. 13 -1 b, p 283 Price MC ATC 2 ATC 1 P 2 C 1 0 Q 2 Q 1 MR 2 D 1 Quantity © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 21 Monopolistic Competition, Fig. 13 -1 c, p 283 Price MC P 1 P 2 P 3 =C 3 C 2 C 1 0 ATC 3 Q 3 MR 3 D 3 Quantity © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

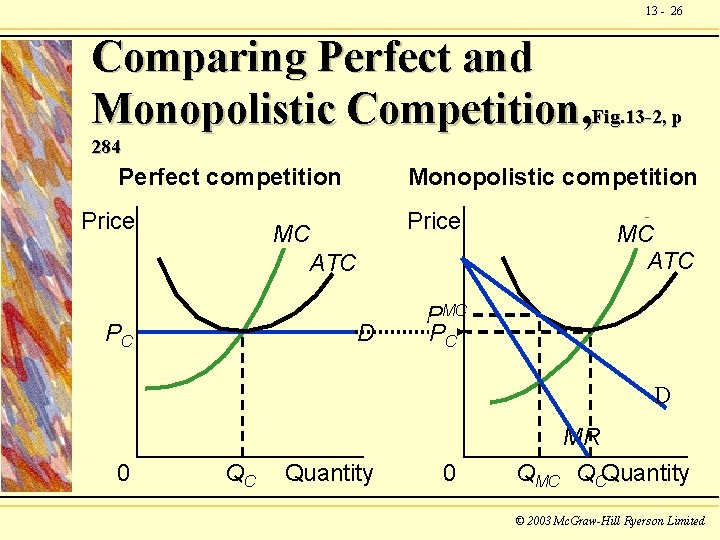

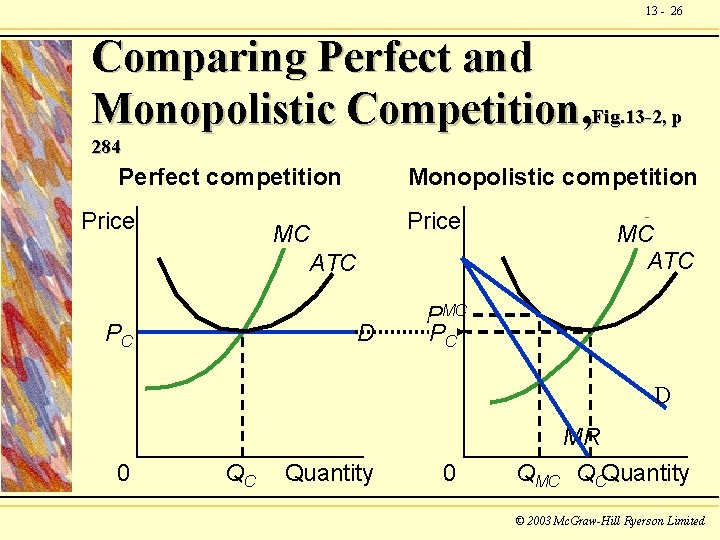

13 - 22 Comparing Monopolistic Competition with Perfect Competition u Both the monopolistic competitor and the perfect competitor make zero economic profit in the long run. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 23 Comparing Monopolistic Competition with Perfect Competition u The perfect competitor’s demand curve is perfectly elastic. u Zero economic profit means that it produces at the minimum of the ATC curve. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 24 Comparing Monopolistic Competition with Perfect Competition u. A monopolistic competitor faces a downward sloping demand curve u It produces where MC = MR, and not where MC =P. u The ATC curve is tangent to the demand curve in the zero-profit long run equilibrium, so the firm does not produce at the minimum point of the ATC curve. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 25 Comparing Monopolistic Competition with Perfect Competition u. A monopolistic competitor produces less than a perfect competitor. u For a monopolistic competitor, increasing market share is a relevant concern, since it can decrease the average cost by increasing output. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 26 Comparing Perfect and Monopolistic Competition, Fig. 13 -2, p 284 Perfect competition Price Monopolistic competition Price MC ATC D PC MC ATC PMC PC D 0 QC Quantity 0 MR QMC QCQuantity © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 27 Comparing Monopolistic Competition with Monopoly u The difference between a monopolist and a monopolistic competitor is in the position of the average total cost curve in long-run equilibrium. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 28 Comparing Monopolistic Competition with Monopoly u The monopolist makes a long-run economic profit since entry is prevented by significant barriers to entry. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 29 Comparing Monopolistic Competition with Monopoly u For a monopolistic competitor, barriers to entry are low, and entry means that no long run economic profit is possible. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 30 Advertising and Monopolistic Competition u Firms in a perfectly competitive market have no incentive to advertise u Monopolistic competitors have a strong incentive to do so. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 31 Characteristics Oligopoly u Oligopolies are made up of a small number of very large firms. u Products may be homogeneous or differentiated u Firms are mutually interdependent. u Each firm must take into account the expected reaction of other firms. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 32 Models of Oligopoly Behavior u Oligopolistic industries are difficult to characterize. u There is no single general model of oligopoly because each oligopolistic industry is different. u Two (out of many) models of oligopoly behavior are the cartel model and the contestable market model. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 33 Models of Oligopoly Behavior u In the cartel model, an oligopoly sets a monopoly price. u In the contestable market model, an oligopoly with no barriers to entry sets a competitive price. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 34 The Cartel Model u. A cartel is a combination of firms that acts as if it were a single firm. u If oligopolies can limit entry, they have a strong incentive to collude. u To collude is to get together with other firms to set price or allocate market share. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 35 The Cartel Model u The cartel model of oligopoly assumes that oligopolies act as if they were monopolists that have assigned output quotas to individual member firms so that total output is consistent with joint profit maximization. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 36 Implicit Price Collusion u Formal collusion is against the law in Canada, but informal collusion is allowed. u Implicit price collusion exists when multiple firms make the same pricing decisions even though they have not consulted with one another. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 37 Implicit Price Collusion u Sometimes the largest or most dominant firm takes the lead in pricing and output decisions, and the others follow. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 38 Cartels and Technological Change u Cartels can be destroyed by an outsider with technological superiority. u Thus, cartels with high profits will provide incentives for significant technological change. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

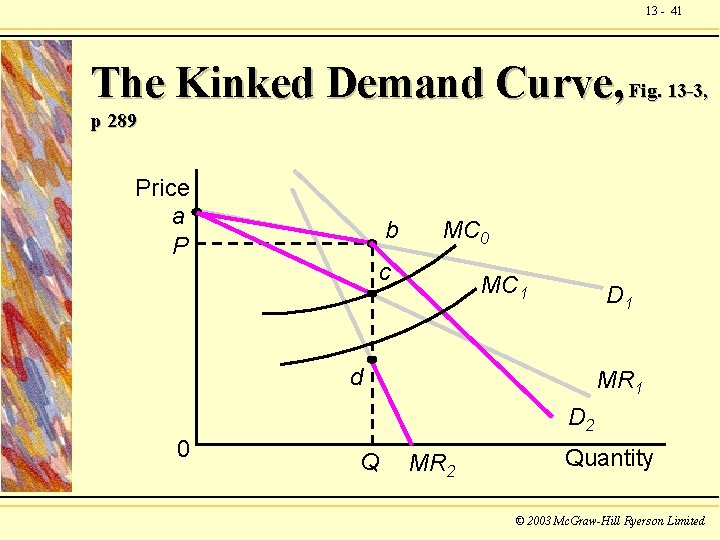

13 - 39 Kinked Demand: Why Are Prices Sticky? u Informal collusion is an important reason why prices are sticky. u Another is the kinked demand curve. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

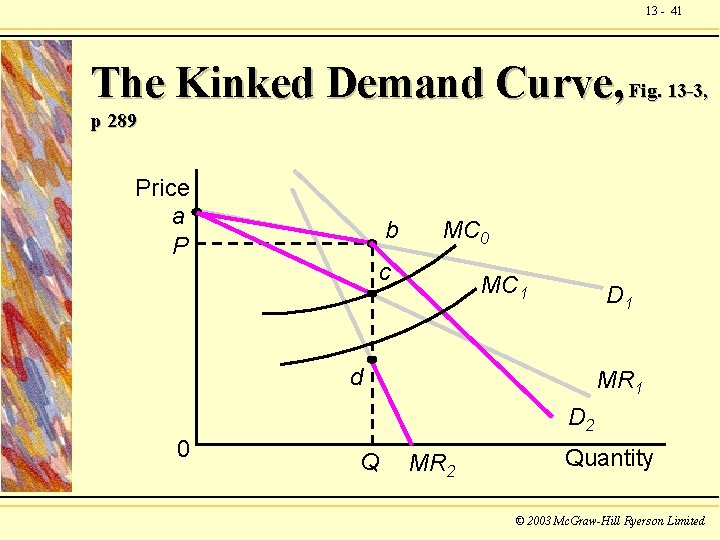

13 - 40 Kinked Demand u When there is a kink in the demand curve, there has to be a gap in the marginal revenue curve. u The kinked demand curve is not a theory of oligopoly but a theory of sticky prices. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 41 The Kinked Demand Curve, Fig. 13 -3, p 289 Price a P b MC 0 c MC 1 D 1 d MR 1 D 2 0 Q MR 2 Quantity © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 42 The Contestable Market Model u According to the contestable market model, barriers to entry and barriers to exit determine a firm’s price and output decisions. l Even if the industry contains a very small number of firms, it could still behave as a competitive market if entry is open. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 43 The Contestable Market Model u The stronger the ability of the oligopolists to collude and prevent market entry, the closer it is to a monopolist solution. u The weaker the ability to collude, the more competitive will be the market. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 44 Strategic Pricing and Oligopoly u Both the cartel and contestable market models use strategic pricing decisions— they set their prices based on the expected reactions of other firms. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 45 Strategic Pricing and Oligopoly u Creation of cartels is limited by threat of outside competition. u In many industries the outside competition comes from international firms. u For a cartel with few barriers to entry, the long run demand curve is very elastic. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 46 Price Wars u Price wars are the result of strategic pricing decisions breaking down. u If prices fall below average total cost, firms may enter into a price war in any oligopoly. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 47 Price Wars u. A firm may develop a predatory pricing strategy as a matter of policy l A predatory pricing strategy involves temporarily pushing the price down below cost in order to drive a competitor out of business. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 48 Game Theory and Strategic Decision Making u Game theory is the application of economic principles to interdependent situations. u One example is the “prisoners’ dilemma” game. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 49 The Prisoner’s Dilemma and a Duopoly Example u The prisoner’s dilemma is one wellknown game that demonstrates the difficulty of cooperative behavior in certain circumstances. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 50 The Prisoner’s Dilemma and a Duopoly Example u The prisoners dilemma has its simplest application when the oligopoly consists of only two firms—a duopoly. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 51 The Prisoner’s Dilemma and a Duopoly Example u By analyzing the strategies of both firms under all situations, all possibilities are placed in a payoff matrix. u A payoff matrix is a box that contains the outcomes of a strategic game under various circumstances. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

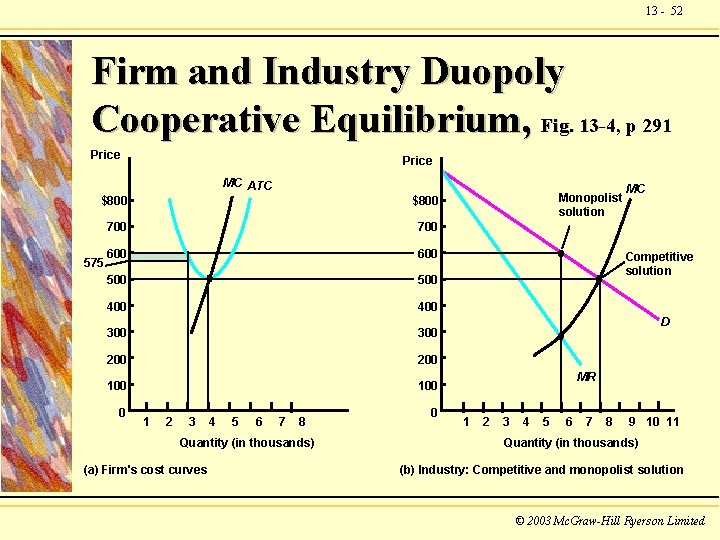

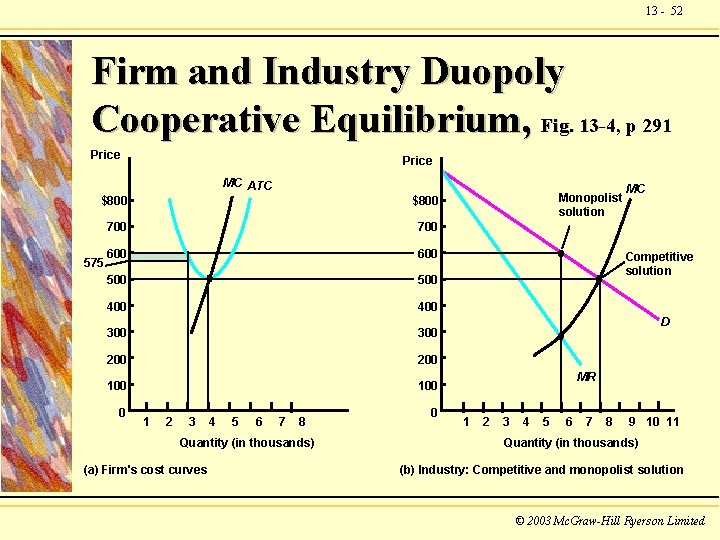

13 - 52 Firm and Industry Duopoly Cooperative Equilibrium, Fig. 13 -4, p 291 Price MC ATC $800 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 575 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Quantity (in thousands) (a) Firm's cost curves 0 Monopolist solution MC Competitive solution D MR 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Quantity (in thousands) (b) Industry: Competitive and monopolist solution © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

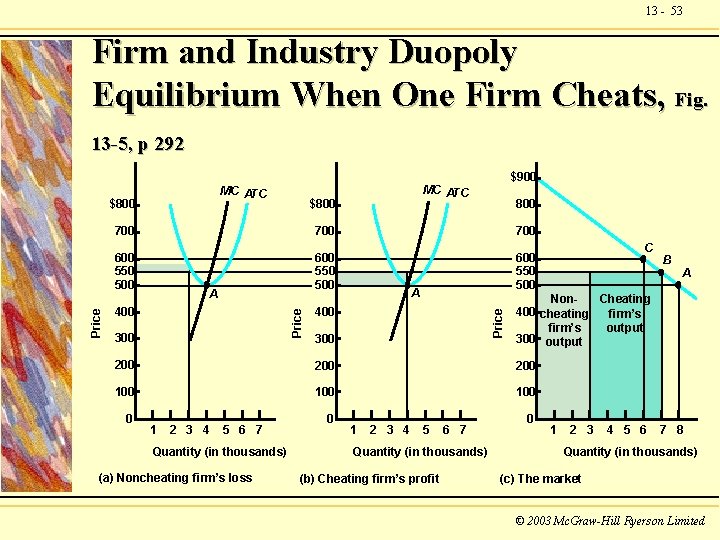

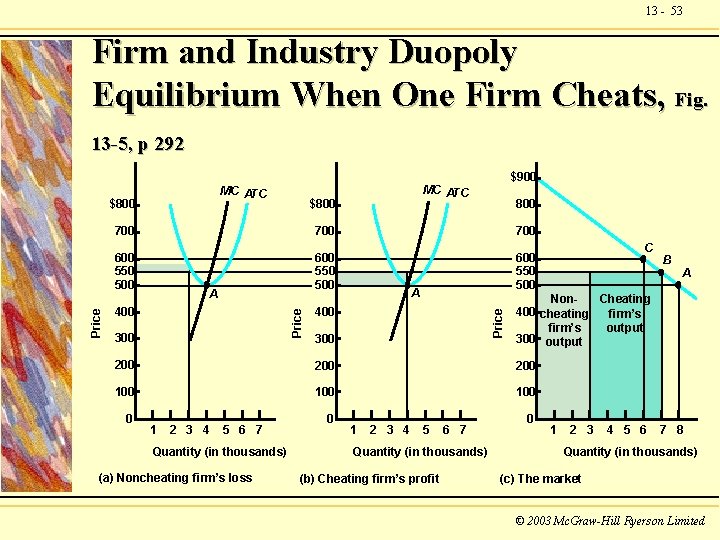

13 - 53 Firm and Industry Duopoly Equilibrium When One Firm Cheats, Fig. 13 -5, p 292 MC ATC $800 700 700 600 550 500 400 300 A 400 Price A Price $800 $900 MC ATC 300 200 100 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Quantity (in thousands) (a) Noncheating firm’s loss 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Quantity (in thousands) (b) Cheating firm’s profit B A Non. Cheating 400 cheating firm’s output 300 output 200 0 C 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Quantity (in thousands) (c) The market © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

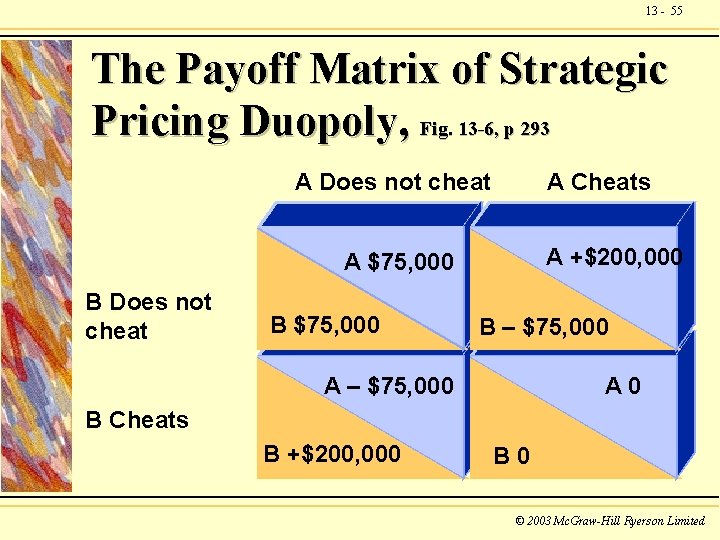

13 - 54 Duopoly and a Payoff Matrix u The duopoly is a variation of the prisoner's dilemma game. u The results can be presented in a payoff matrix that captures the essence of the prisoner's dilemma. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

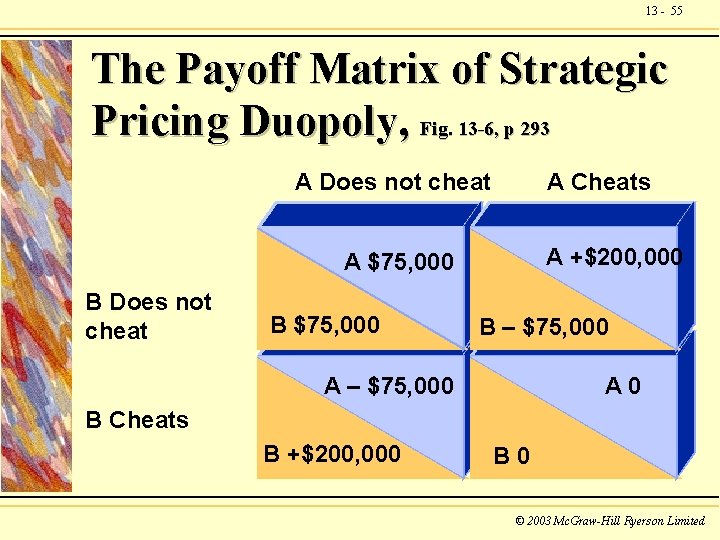

13 - 55 The Payoff Matrix of Strategic Pricing Duopoly, Fig. 13 -6, p 293 A Does not cheat A Cheats A +$200, 000 A $75, 000 B Does not cheat B $75, 000 B – $75, 000 A 0 B Cheats B +$200, 000 B 0 © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 56 Oligopoly Models, Structure, and Performance u Oligopoly models are based either on structure or performance. The four-fold division of markets considered so far are based on market structure. l Structure means the number, size, and interrelationship of firms in the industry. l © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 57 Oligopoly Models, Structure, and Performance u. A monopoly is considered the least competitive, perfectly competitive industries are considered the most competitive. © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 58 Oligopoly Models, Structure, and Performance u The contestable market model gives less weight to market structure. Markets in this model are judged by performance, not structure. l Performance includes such results as ratio of price to marginal cost, output, allocative and productive efficiency, product variety, innovation rate, and profits. l © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

13 - 59 Oligopoly Models, Structure, and Performance u There is a similarity in the two approaches, structure versus performance Often barriers to entry are the reason there are only a few firms in an industry. l When there are many firms, that’s usually because there are few barriers to entry. l In most situations the two approaches come to the same conclusion regarding competitiveness. l © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited

Monopolistic Competition, Oligopoly, and Strategic Pricing End of Chapter 13 © 2003 Mc. Graw-Hill Ryerson Limited.