MODULE 5 OPERATOR OVERLOADING Understanding Operators It is

- Slides: 33

MODULE 5 OPERATOR OVERLOADING

Understanding Operators • It is worth recapping some of the fundamental aspects of operators before delving into the details of how they work and how you can overload them. In summary: 1) You use operators to combine operands together into expressions. Each operator has its own semantics, dependent on the type it works with. For example, the + operator means “add” when used with numeric types or “concatenate” when used with strings. 2) Each operator has a precedence. For example, the * operator has a higher precedence than the + operator. This means that the expression a + b * c is the same as a + (b * c). 3) Each operator also has an associativity to define whether the operator evaluates from left to right or from right to left. For example, the = operator is right-associative (it evaluates from right to left), so a = b = c is the same as a = (b = c). 4) A unary operator is an operator that has just one operand. For example, the increment operator (++) is a unary operator. 5) A binary operator is an operator that has two operands. For example, the multiplication operator (*) is a binary operator.

Operator Constraints You have seen throughout this book that C# enables you to overload methods when defining your own types. C# also allows you to overload many of the existing operator symbols for your own types, although the syntax is slightly different. When you do this, the operators you implement automatically fall into a well-defined framework with the following rules: 1. You cannot change the precedence and associativity of an operator. The precedence and associativity are based on the operator symbol (for example, +) and not on the type (for example, int) on which the operator symbol is being used. Hence, the expression a + b * c is always the same as a + (b * c), regardless of the types of a, b, and c. 2. You cannot change the multiplicity (the number of operands) of an operator. For example, * (the symbol for multiplication) is a binary operator. If you declare a * operator for your own type, it must be a binary operator. 3. You cannot invent new operator symbols. For example, you can’t create a new operator symbol, such as ** for raising one number to the power of another number. You’d have to create a method for that. 4. You can’t change the meaning of operators when applied to built-in types. For example, the expression 1 + 2 has a predefined meaning, and you’re not allowed to override this meaning. If you could do this, things would be too complicated! 5. There are some operator symbols that you can’t overload. For example, you can’t overload the dot (. ) operator, which indicates access to a class member. Again, if you could do this, it would lead to unnecessary complexity.

Overloaded Operators To define your own operator behavior, you must overload a selected operator. You use methodlike syntax with a return type and parameters, but the name of the method is the keyword operator together with the operator symbol you are declaring. For example, the following code shows a user-defined structure named Hour that defines a binary + operator to add together two instances of Hour: struct Hour { public Hour(int initial. Value) { this. value = initial. Value; } public static Hour operator +(Hour lhs, Hour rhs) { return new Hour(lhs. value + rhs. value); } …………. . private int value; } Notice the following: 1. The operator is public. All operators must be public. 2. The operator is static. All operators must be static. Operators are never polymorphic and cannot use the virtual, abstract, override, or sealed modifiers. 3. A binary operator (such as the + operator shown earlier) has two explicit arguments, and a unary operator has one explicit argument. (C++ programmers should note that operators never have a hidden this parameter. )

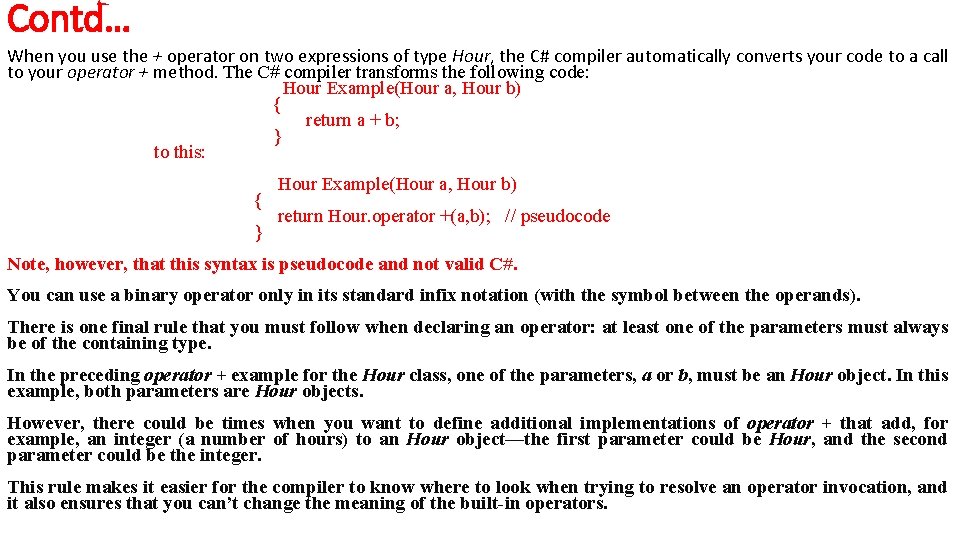

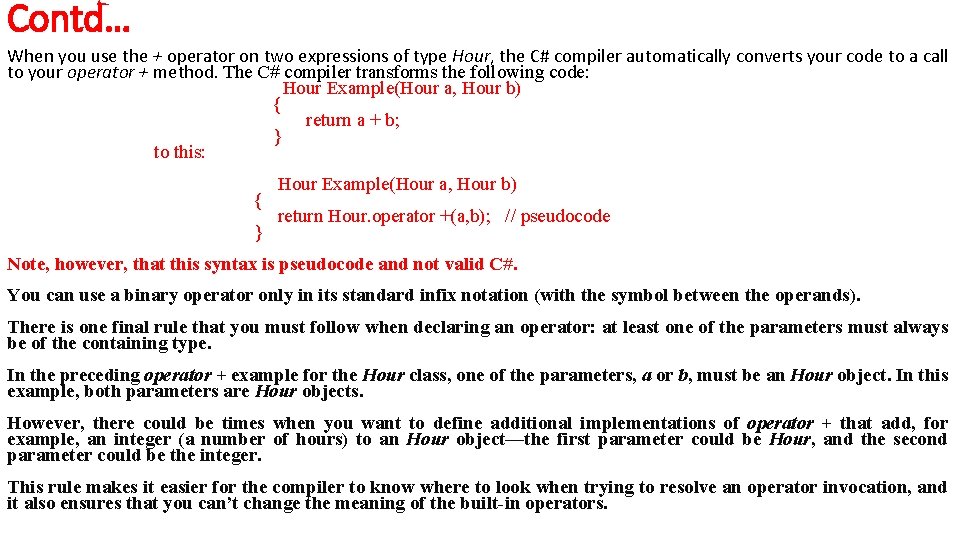

Contd… When you use the + operator on two expressions of type Hour, the C# compiler automatically converts your code to a call to your operator + method. The C# compiler transforms the following code: Hour Example(Hour a, Hour b) { return a + b; } to this: { } Hour Example(Hour a, Hour b) return Hour. operator +(a, b); // pseudocode Note, however, that this syntax is pseudocode and not valid C#. You can use a binary operator only in its standard infix notation (with the symbol between the operands). There is one final rule that you must follow when declaring an operator: at least one of the parameters must always be of the containing type. In the preceding operator + example for the Hour class, one of the parameters, a or b, must be an Hour object. In this example, both parameters are Hour objects. However, there could be times when you want to define additional implementations of operator + that add, for example, an integer (a number of hours) to an Hour object—the first parameter could be Hour, and the second parameter could be the integer. This rule makes it easier for the compiler to know where to look when trying to resolve an operator invocation, and it also ensures that you can’t change the meaning of the built-in operators.

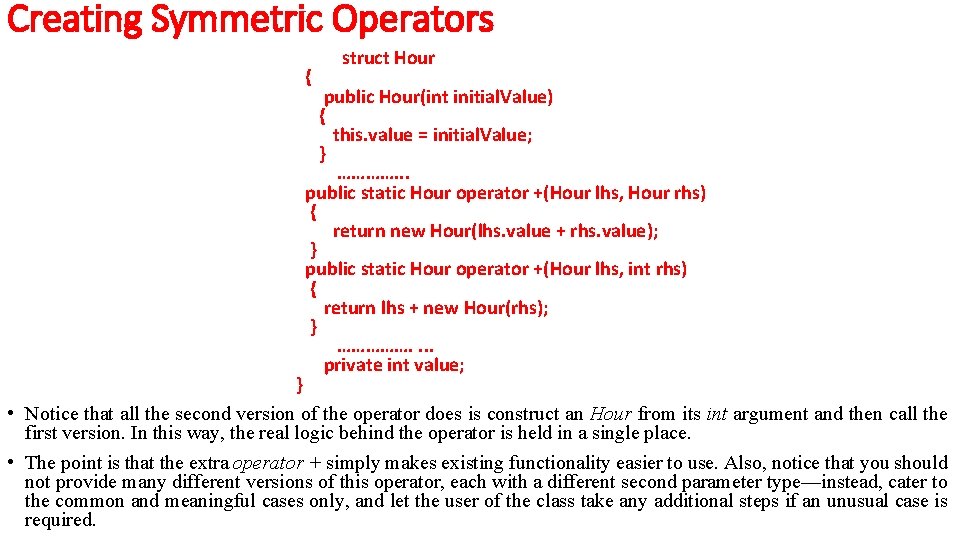

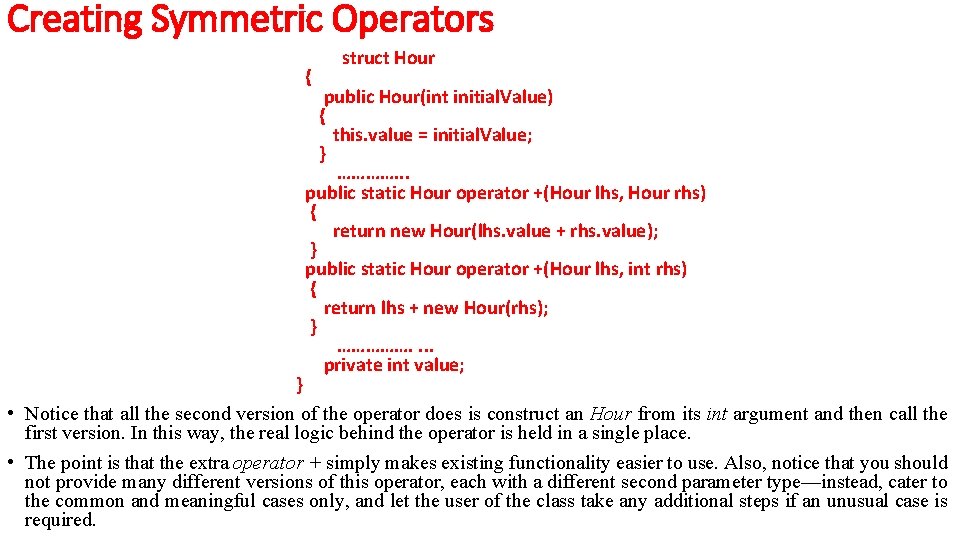

Creating Symmetric Operators • In the preceding section, you saw how to declare a binary + operator to add together two instances of type Hour. The Hour structure also has a constructor that creates an Hour from an int. This means that you can add together an Hour and an int—you just have to first use the Hour constructor to convert the int to an Hour. For example: Hour a =. . . ; int b =. . . ; Hour sum = a + new Hour(b); • This is certainly valid code, but it is not as clear or concise as adding together an Hour and an int directly, like this: Hour a =. . . ; int b =. . . ; Hour sum = a + b; To make the expression (a + b) valid, you must specify what it means to add together an Hour (a, on the left) and an int (b, on the right). In other words, you must declare a binary + operator whose first parameter is an Hour and whose second parameter is an int. The following code shows the recommended approach:

Creating Symmetric Operators { struct Hour public Hour(int initial. Value) { this. value = initial. Value; } …………. . . public static Hour operator +(Hour lhs, Hour rhs) { return new Hour(lhs. value + rhs. value); } public static Hour operator +(Hour lhs, int rhs) { return lhs + new Hour(rhs); } ……………. . private int value; } • Notice that all the second version of the operator does is construct an Hour from its int argument and then call the first version. In this way, the real logic behind the operator is held in a single place. • The point is that the extra operator + simply makes existing functionality easier to use. Also, notice that you should not provide many different versions of this operator, each with a different second parameter type—instead, cater to the common and meaningful cases only, and let the user of the class take any additional steps if an unusual case is required.

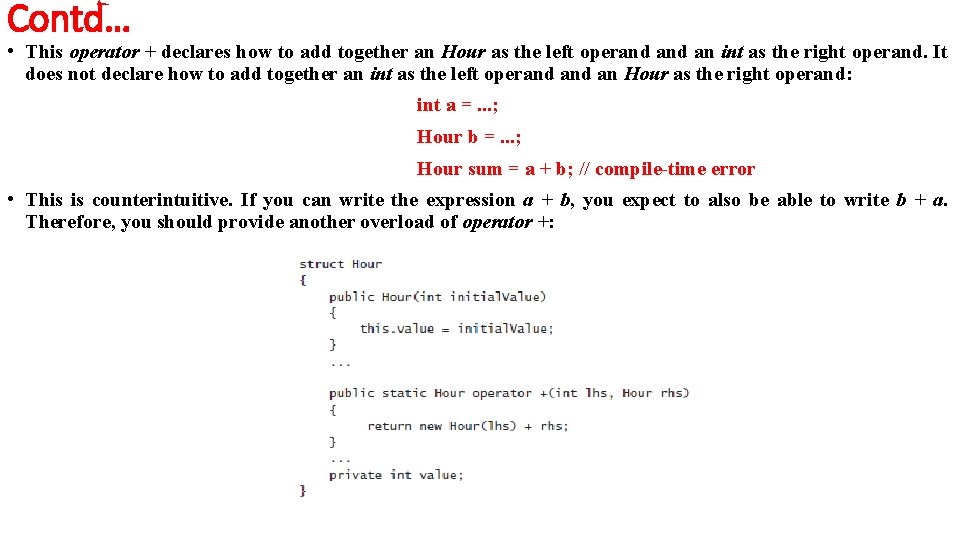

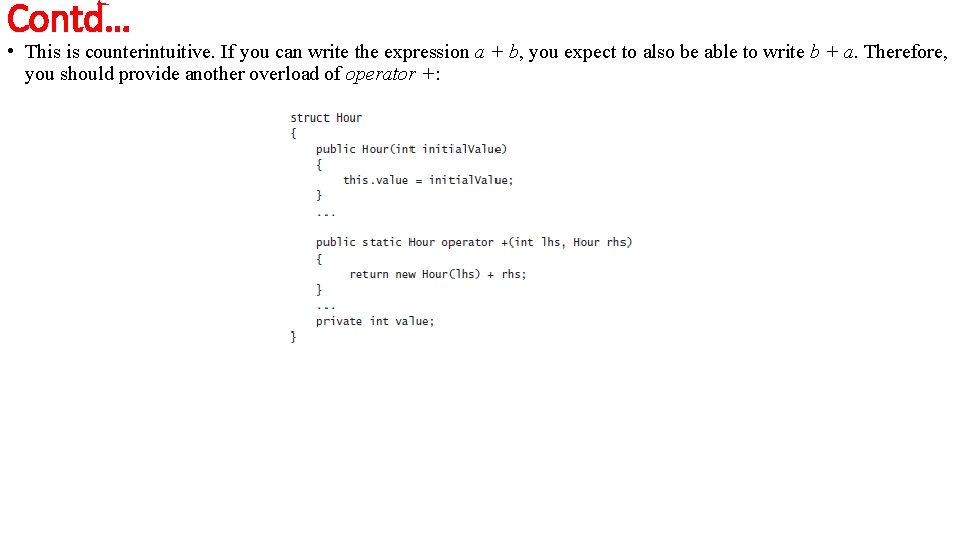

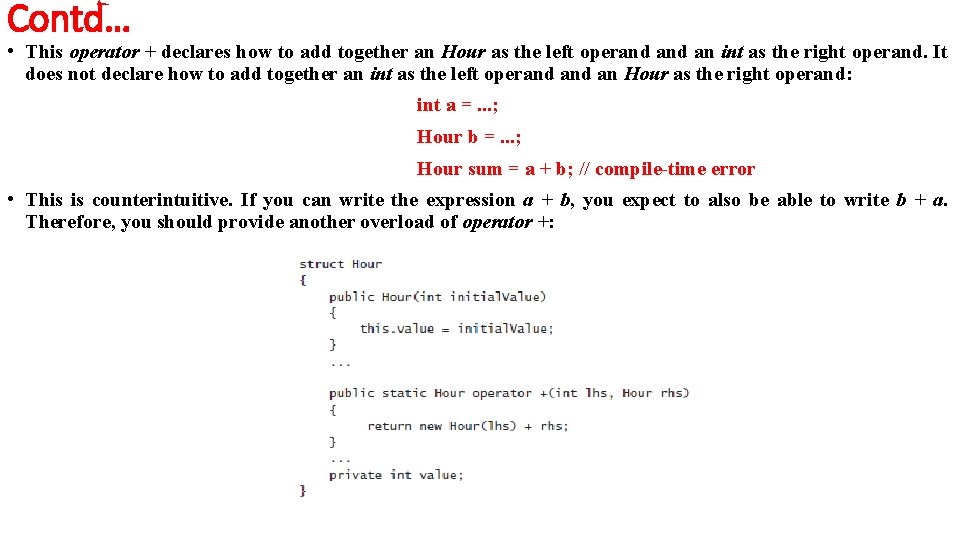

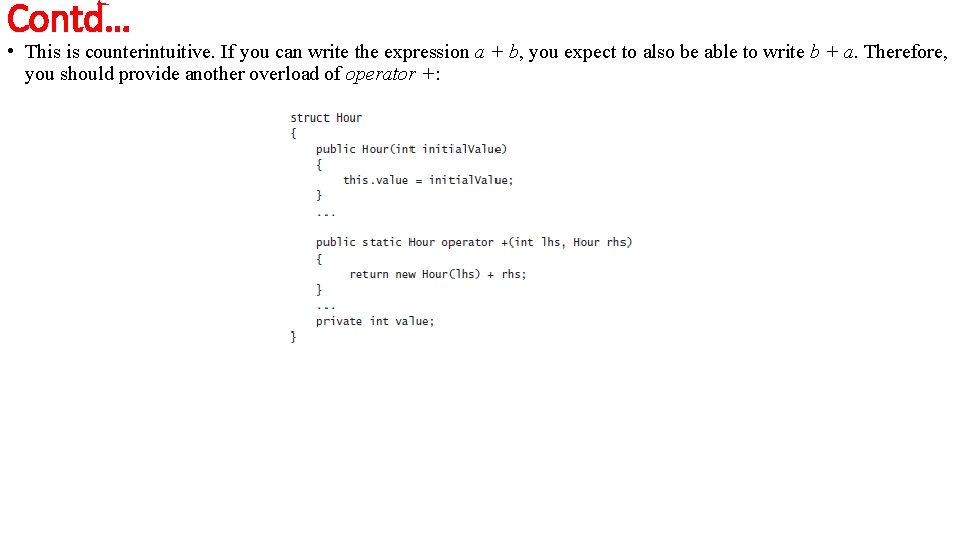

Contd… • This operator + declares how to add together an Hour as the left operand an int as the right operand. It does not declare how to add together an int as the left operand an Hour as the right operand: int a =. . . ; Hour b =. . . ; Hour sum = a + b; // compile-time error • This is counterintuitive. If you can write the expression a + b, you expect to also be able to write b + a. Therefore, you should provide another overload of operator +:

Contd… • This is counterintuitive. If you can write the expression a + b, you expect to also be able to write b + a. Therefore, you should provide another overload of operator +:

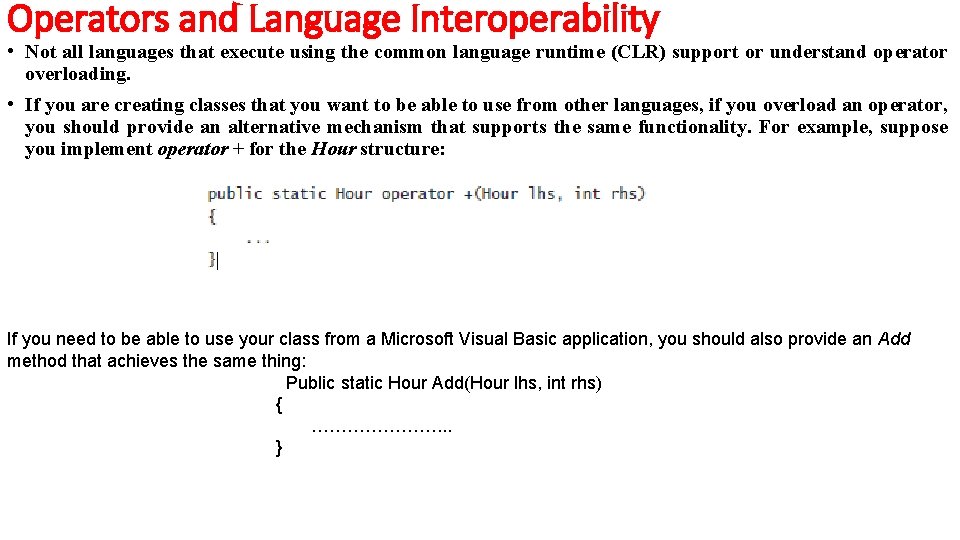

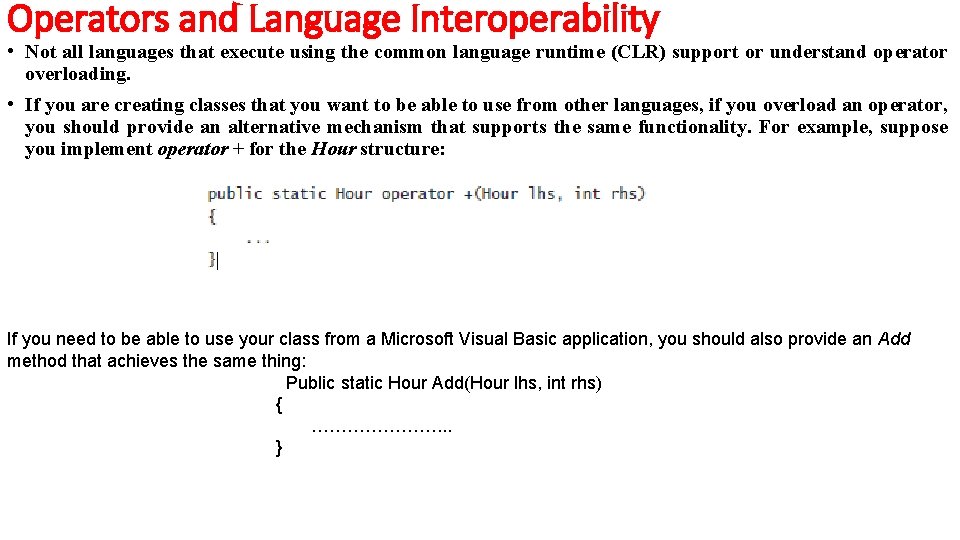

Operators and Language Interoperability • Not all languages that execute using the common language runtime (CLR) support or understand operator overloading. • If you are creating classes that you want to be able to use from other languages, if you overload an operator, you should provide an alternative mechanism that supports the same functionality. For example, suppose you implement operator + for the Hour structure: If you need to be able to use your class from a Microsoft Visual Basic application, you should also provide an Add method that achieves the same thing: Public static Hour Add(Hour lhs, int rhs) { …………………. . . }

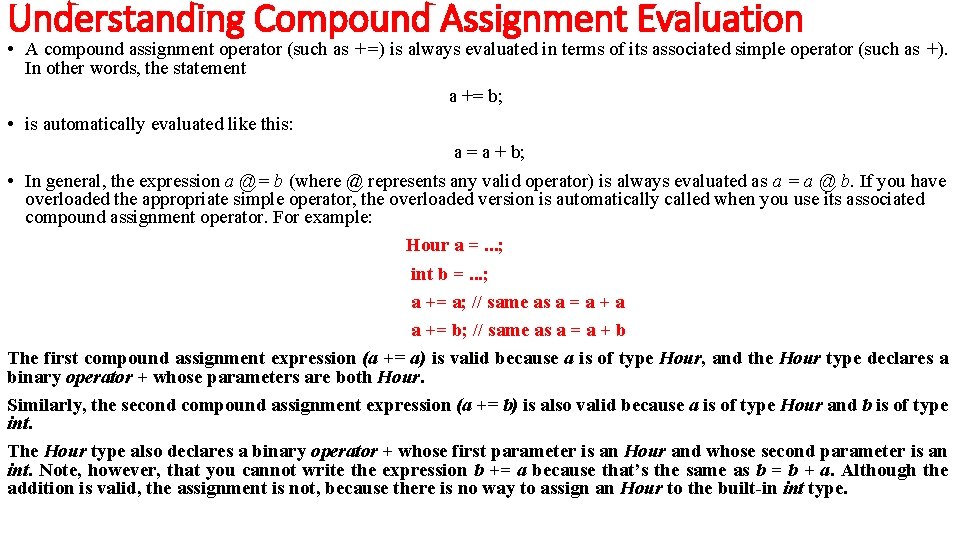

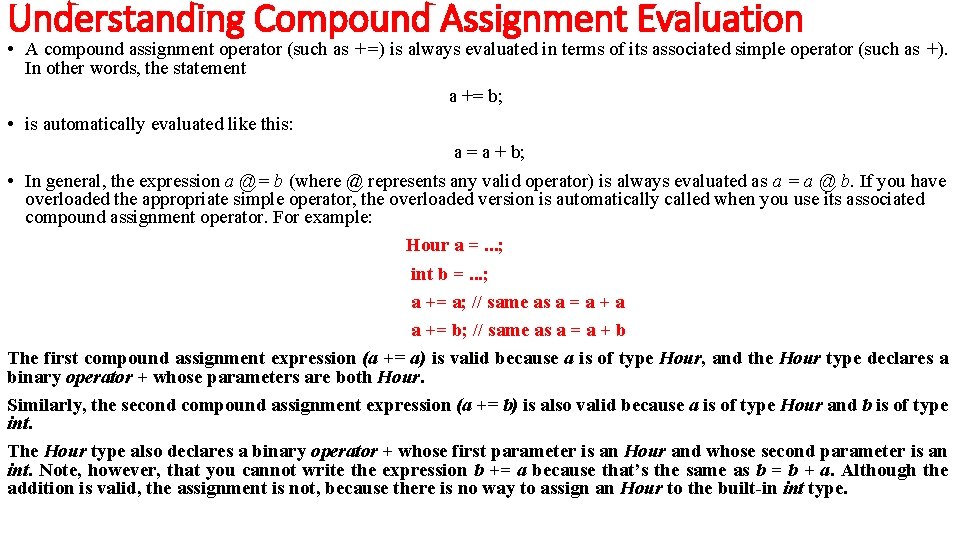

Understanding Compound Assignment Evaluation • A compound assignment operator (such as +=) is always evaluated in terms of its associated simple operator (such as +). In other words, the statement a += b; • is automatically evaluated like this: a = a + b; • In general, the expression a @= b (where @ represents any valid operator) is always evaluated as a = a @ b. If you have overloaded the appropriate simple operator, the overloaded version is automatically called when you use its associated compound assignment operator. For example: Hour a =. . . ; int b =. . . ; a += a; // same as a = a + a a += b; // same as a = a + b The first compound assignment expression (a += a) is valid because a is of type Hour, and the Hour type declares a binary operator + whose parameters are both Hour. Similarly, the second compound assignment expression (a += b) is also valid because a is of type Hour and b is of type int. The Hour type also declares a binary operator + whose first parameter is an Hour and whose second parameter is an int. Note, however, that you cannot write the expression b += a because that’s the same as b = b + a. Although the addition is valid, the assignment is not, because there is no way to assign an Hour to the built-in int type.

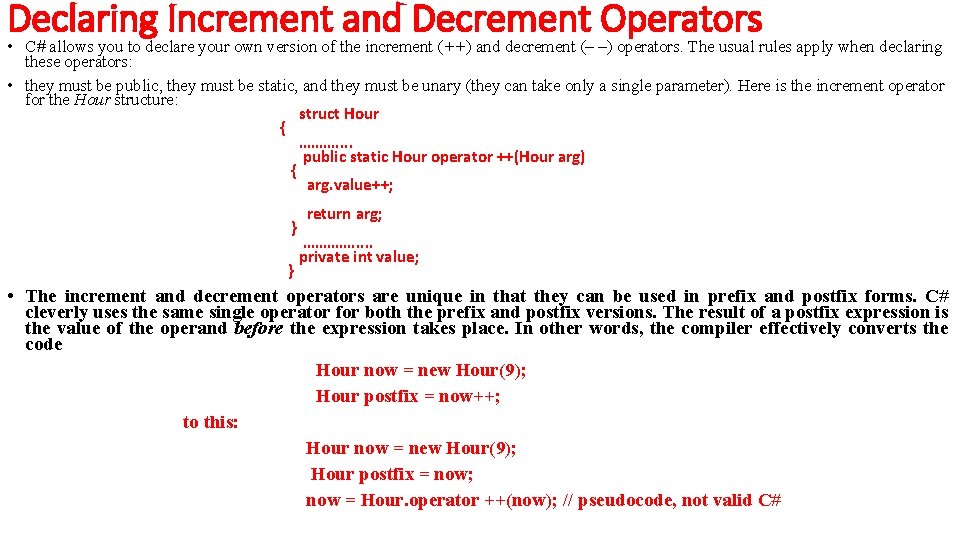

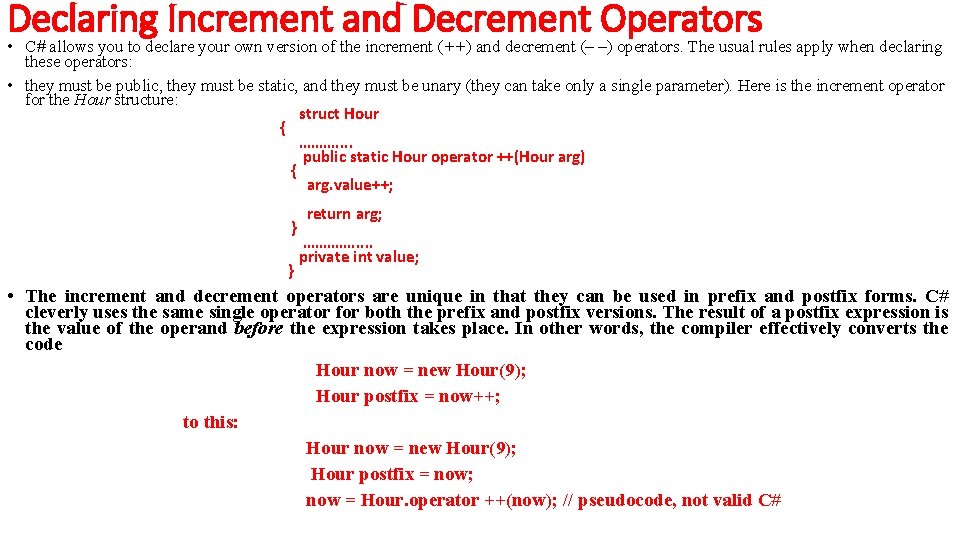

Declaring Increment and Decrement Operators • C# allows you to declare your own version of the increment (++) and decrement (– –) operators. The usual rules apply when declaring these operators: • they must be public, they must be static, and they must be unary (they can take only a single parameter). Here is the increment operator for the Hour structure: struct Hour { ………. . public static Hour operator ++(Hour arg) { arg. value++; } } return arg; …………. . . private int value; • The increment and decrement operators are unique in that they can be used in prefix and postfix forms. C# cleverly uses the same single operator for both the prefix and postfix versions. The result of a postfix expression is the value of the operand before the expression takes place. In other words, the compiler effectively converts the code Hour now = new Hour(9); Hour postfix = now++; to this: Hour now = new Hour(9); Hour postfix = now; now = Hour. operator ++(now); // pseudocode, not valid C#

Contd… • The result of a prefix expression is the return value of the operator, so the C# compiler effectively transforms the code Hour now = new Hour(9); Hour prefix = ++now; to this: Hour now = new Hour(9); now = Hour. operator ++(now); // pseudocode, not valid C# Hour prefix = now; • This equivalence means that the return type of the increment and decrement operators must be the same as the parameter type.

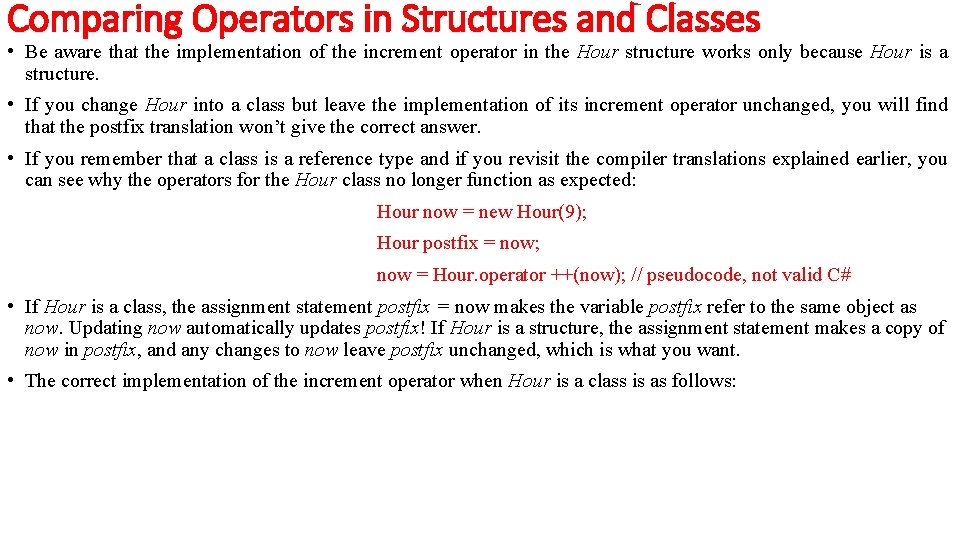

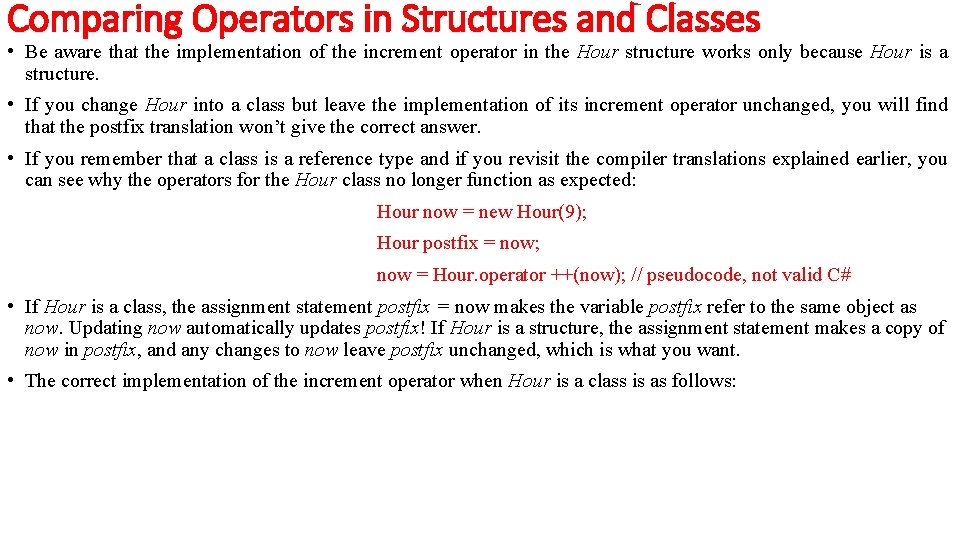

Comparing Operators in Structures and Classes • Be aware that the implementation of the increment operator in the Hour structure works only because Hour is a structure. • If you change Hour into a class but leave the implementation of its increment operator unchanged, you will find that the postfix translation won’t give the correct answer. • If you remember that a class is a reference type and if you revisit the compiler translations explained earlier, you can see why the operators for the Hour class no longer function as expected: Hour now = new Hour(9); Hour postfix = now; now = Hour. operator ++(now); // pseudocode, not valid C# • If Hour is a class, the assignment statement postfix = now makes the variable postfix refer to the same object as now. Updating now automatically updates postfix! If Hour is a structure, the assignment statement makes a copy of now in postfix, and any changes to now leave postfix unchanged, which is what you want. • The correct implementation of the increment operator when Hour is a class is as follows:

Comparing Operators in Structures and Classes Notice that operator ++ now creates a new object based on the data in the original. The data in the new object is incremented, but the data in the original is left unchanged. Although this works, the compiler translation of the increment operator results in a new object being created each time it is used. This can be expensive in terms of memory use and garbage collection overhead. Therefore, it is recommended that you limit operator overloads when you define types. This recommendation applies to all operators, not just to the increment operator.

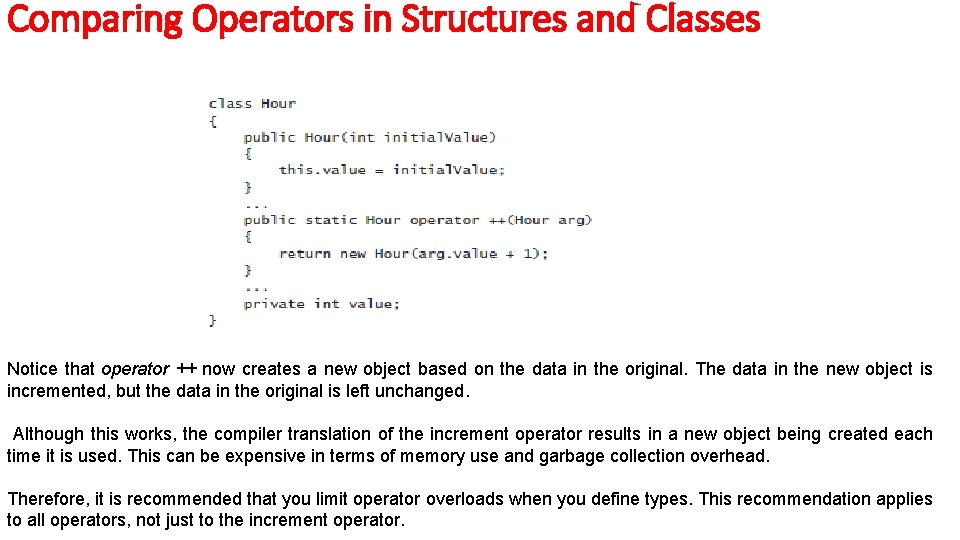

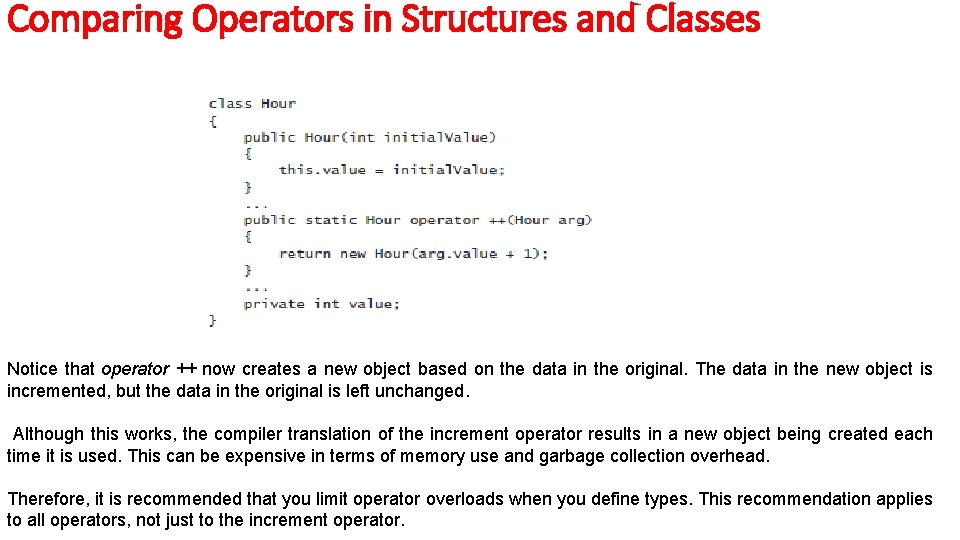

Defining Operator Pairs • Some operators naturally come in pairs. For example, if you can compare two Hour values by using the != operator, you would expect to be able to also compare two Hour values by using the == operator. • The C# compiler enforces this very reasonable expectation by insisting that if you define either operator == or operator !=, you must define them both. • This neither-or-both rule also applies to the < and > operators and the <= and >= operators. The C# compiler does not write any of these operator partners for you. • You must write them all explicitly yourself, regardless of how obvious they might seem. Here are the == and != operators for the Hour structure:

Contd… • The return type from these operators does not actually have to be Boolean. However, you would need to have a very good reason for using some other type, or these operators could become very confusing! Implementing Operators • In the following exercise, you will develop a class that simulates complex numbers. • A complex number has two elements: a real component and an imaginary component. Typically, a complex number is represented in the form (x + yi), where x is the real component and yi is the imaginary component. • The values of x and y are regular integers, and i represents the square root of – 1 (hence the reason why yi is imaginary). • Despite their rather obscure and theoretical feel, complex numbers have a large number of uses in the fields of electronics, applied mathematics, and physics, and in many aspects of engineering. • If you want more information about how and why complex numbers are useful, Wikipedia provides a useful and informative article.

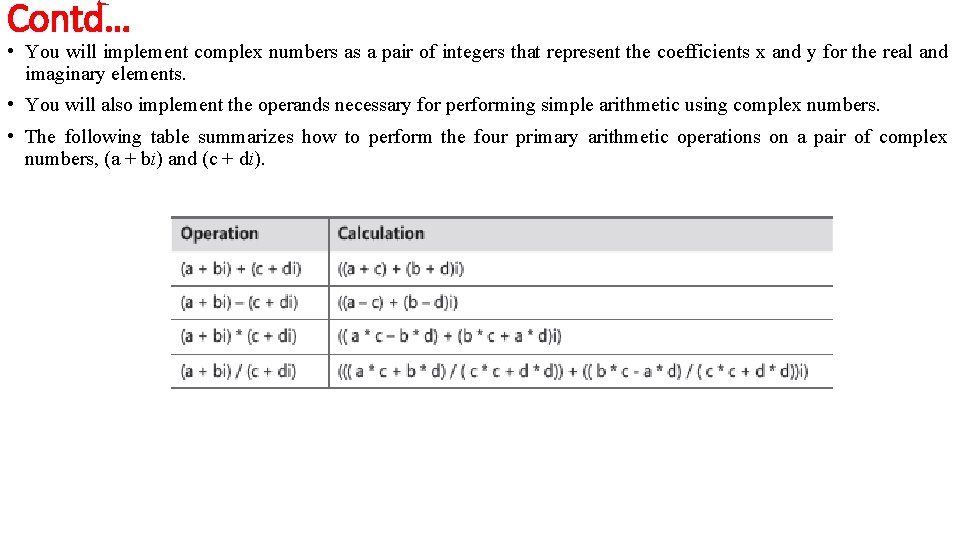

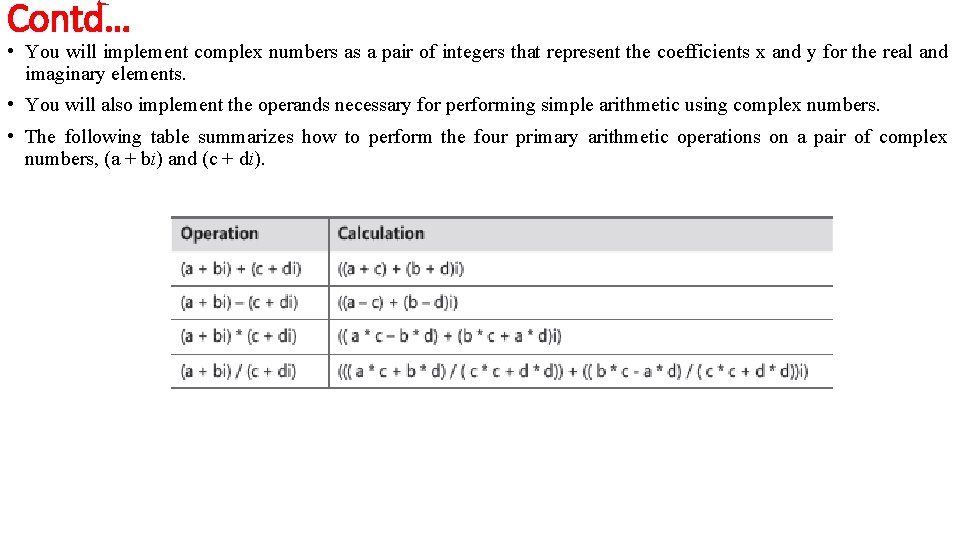

Contd… • You will implement complex numbers as a pair of integers that represent the coefficients x and y for the real and imaginary elements. • You will also implement the operands necessary for performing simple arithmetic using complex numbers. • The following table summarizes how to perform the four primary arithmetic operations on a pair of complex numbers, (a + bi) and (c + di).

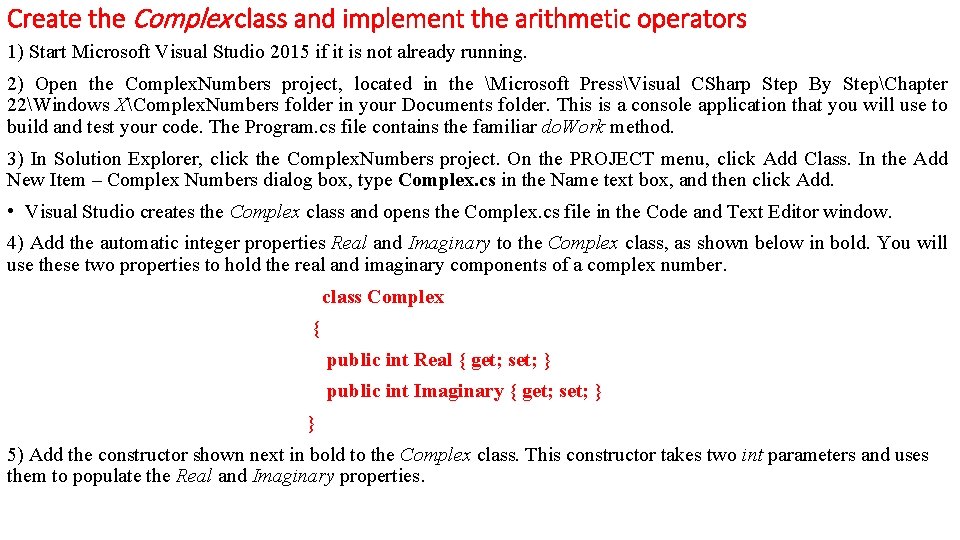

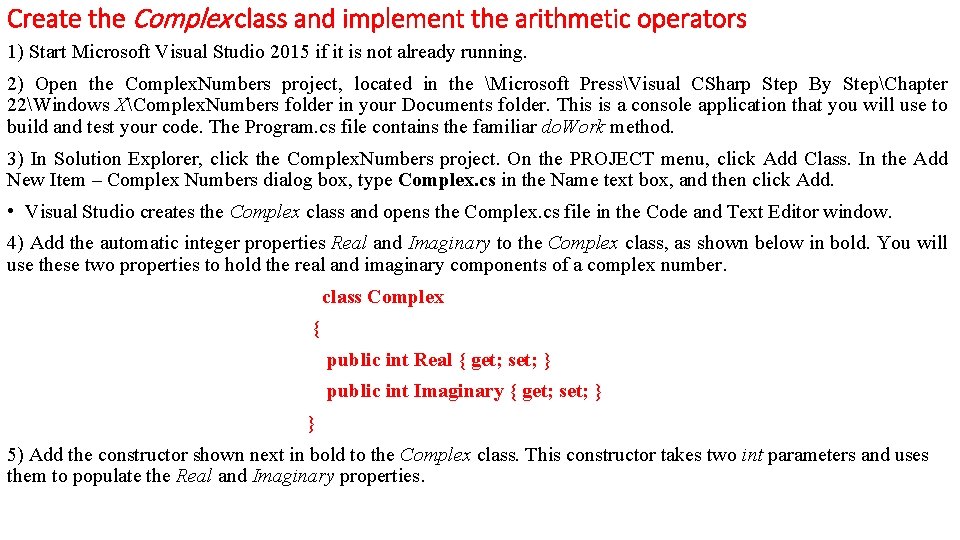

Create the Complex class and implement the arithmetic operators 1) Start Microsoft Visual Studio 2015 if it is not already running. 2) Open the Complex. Numbers project, located in the Microsoft PressVisual CSharp Step By StepChapter 22Windows XComplex. Numbers folder in your Documents folder. This is a console application that you will use to build and test your code. The Program. cs file contains the familiar do. Work method. 3) In Solution Explorer, click the Complex. Numbers project. On the PROJECT menu, click Add Class. In the Add New Item – Complex Numbers dialog box, type Complex. cs in the Name text box, and then click Add. • Visual Studio creates the Complex class and opens the Complex. cs file in the Code and Text Editor window. 4) Add the automatic integer properties Real and Imaginary to the Complex class, as shown below in bold. You will use these two properties to hold the real and imaginary components of a complex number. class Complex { public int Real { get; set; } public int Imaginary { get; set; } } 5) Add the constructor shown next in bold to the Complex class. This constructor takes two int parameters and uses them to populate the Real and Imaginary properties.

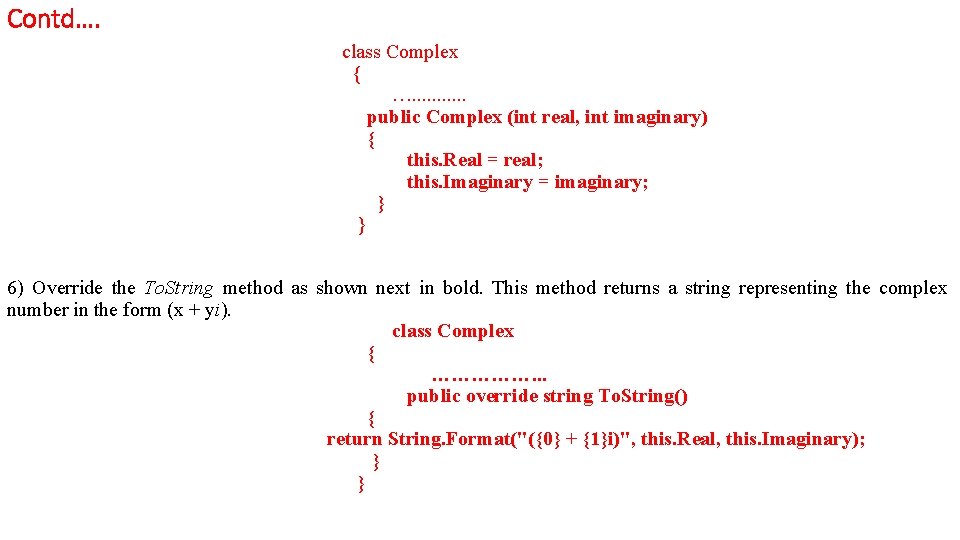

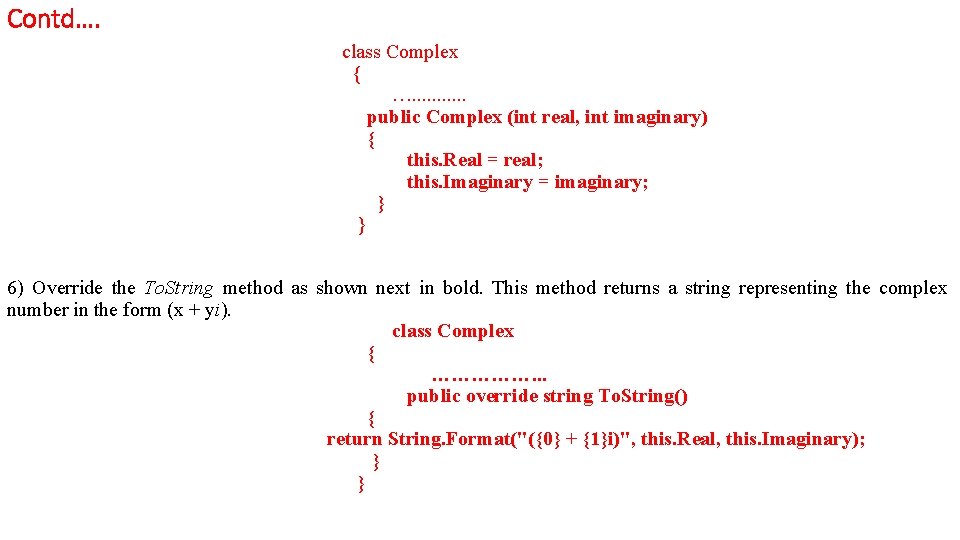

Contd…. class Complex { …. . . public Complex (int real, int imaginary) { this. Real = real; this. Imaginary = imaginary; } } 6) Override the To. String method as shown next in bold. This method returns a string representing the complex number in the form (x + yi). class Complex { ……………. . . public override string To. String() { return String. Format("({0} + {1}i)", this. Real, this. Imaginary); } }

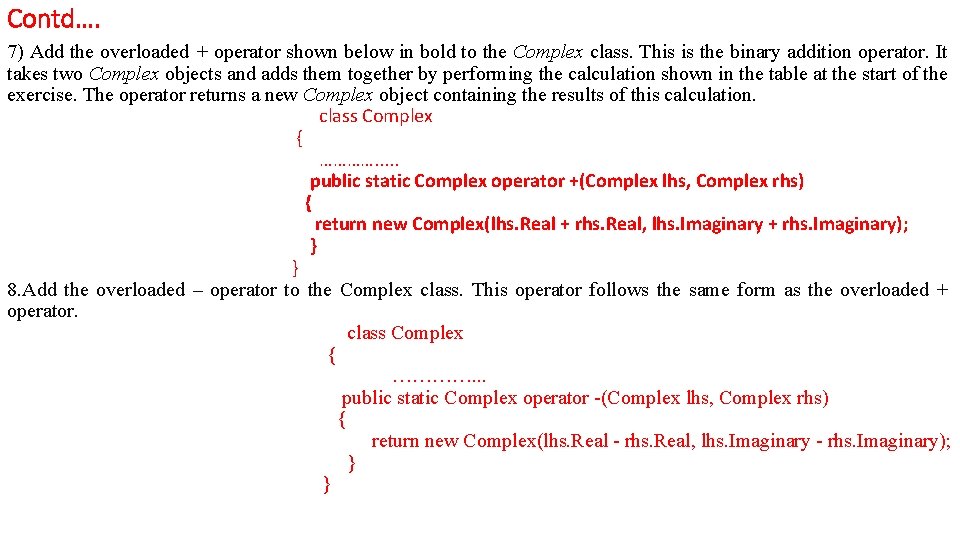

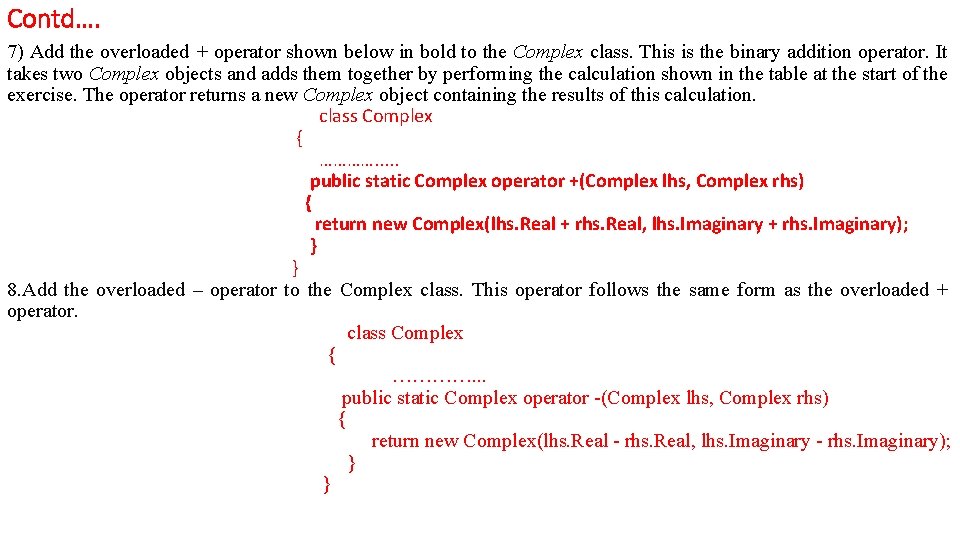

Contd…. 7) Add the overloaded + operator shown below in bold to the Complex class. This is the binary addition operator. It takes two Complex objects and adds them together by performing the calculation shown in the table at the start of the exercise. The operator returns a new Complex object containing the results of this calculation. class Complex { …………. . . public static Complex operator +(Complex lhs, Complex rhs) { return new Complex(lhs. Real + rhs. Real, lhs. Imaginary + rhs. Imaginary); } } 8. Add the overloaded – operator to the Complex class. This operator follows the same form as the overloaded + operator. class Complex { …………. . . public static Complex operator -(Complex lhs, Complex rhs) { return new Complex(lhs. Real - rhs. Real, lhs. Imaginary - rhs. Imaginary); } }

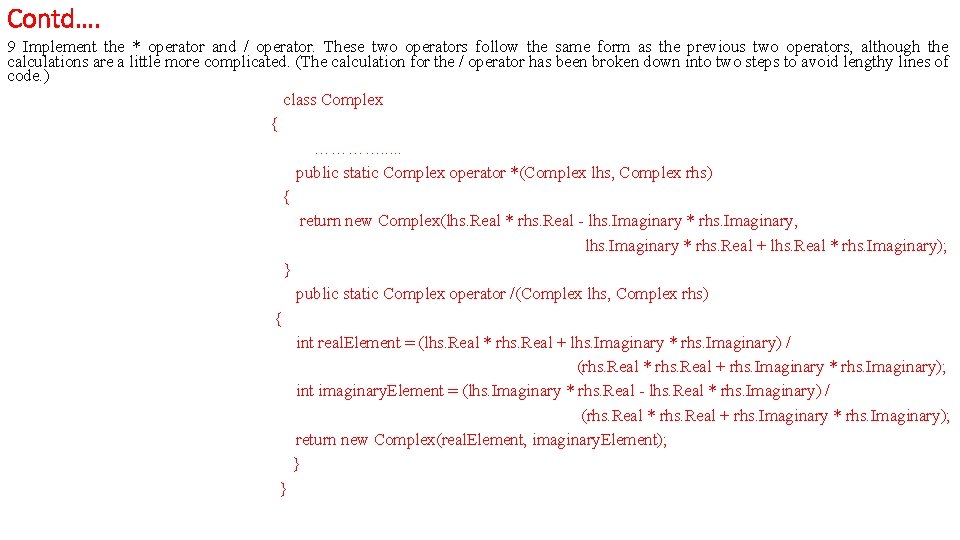

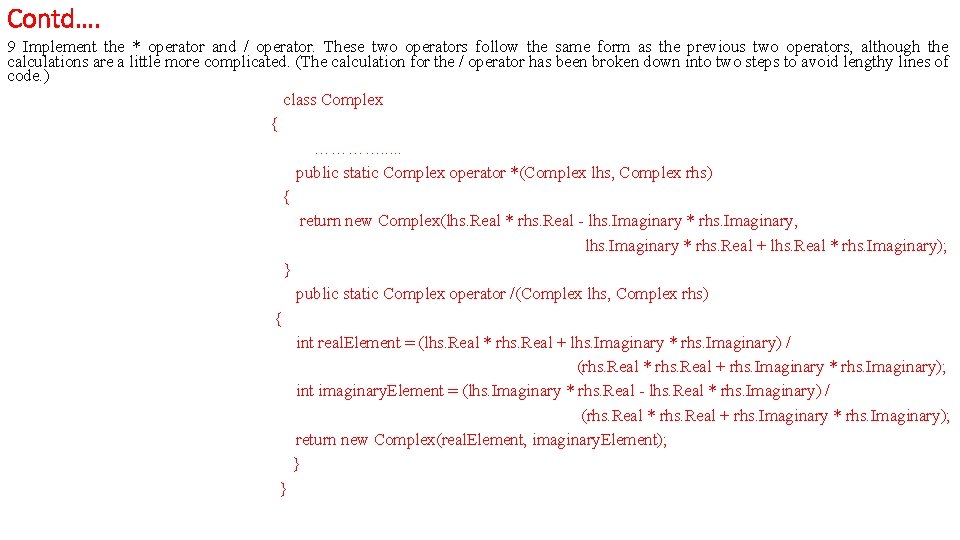

Contd…. 9 Implement the * operator and / operator. These two operators follow the same form as the previous two operators, although the calculations are a little more complicated. (The calculation for the / operator has been broken down into two steps to avoid lengthy lines of code. ) class Complex { …………. . . public static Complex operator *(Complex lhs, Complex rhs) { return new Complex(lhs. Real * rhs. Real - lhs. Imaginary * rhs. Imaginary, lhs. Imaginary * rhs. Real + lhs. Real * rhs. Imaginary); } public static Complex operator /(Complex lhs, Complex rhs) { int real. Element = (lhs. Real * rhs. Real + lhs. Imaginary * rhs. Imaginary) / (rhs. Real * rhs. Real + rhs. Imaginary * rhs. Imaginary); int imaginary. Element = (lhs. Imaginary * rhs. Real - lhs. Real * rhs. Imaginary) / (rhs. Real * rhs. Real + rhs. Imaginary * rhs. Imaginary); return new Complex(real. Element, imaginary. Element); } }

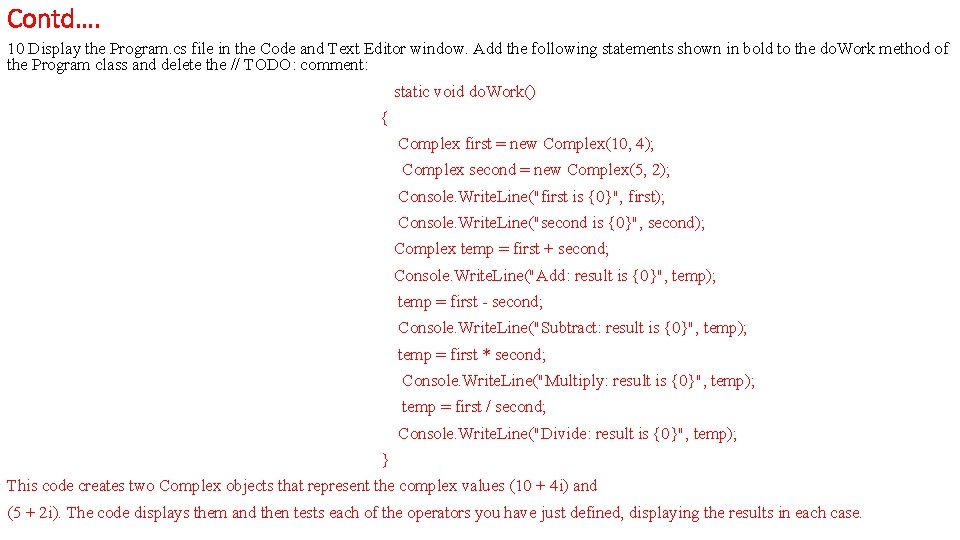

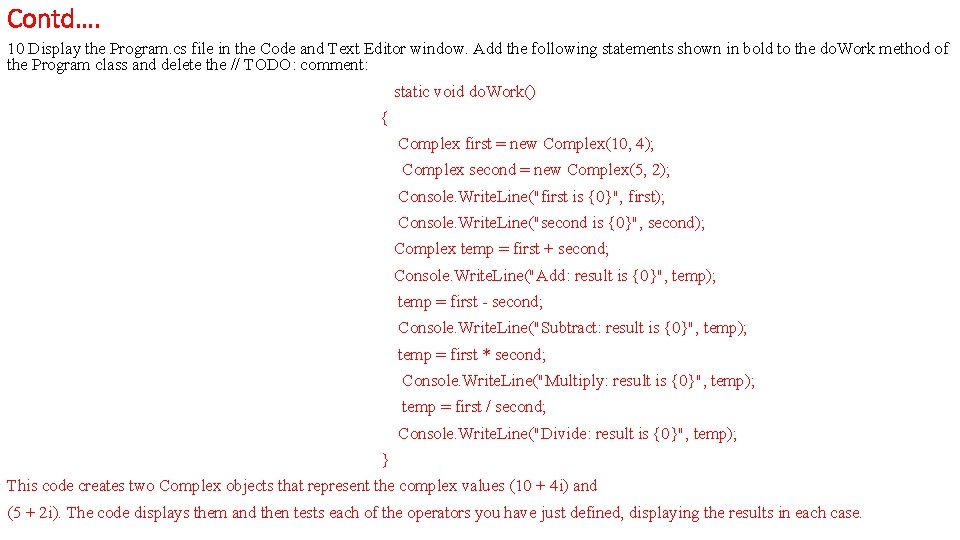

Contd…. 10 Display the Program. cs file in the Code and Text Editor window. Add the following statements shown in bold to the do. Work method of the Program class and delete the // TODO: comment: static void do. Work() { Complex first = new Complex(10, 4); Complex second = new Complex(5, 2); Console. Write. Line("first is {0}", first); Console. Write. Line("second is {0}", second); Complex temp = first + second; Console. Write. Line("Add: result is {0}", temp); temp = first - second; Console. Write. Line("Subtract: result is {0}", temp); temp = first * second; Console. Write. Line("Multiply: result is {0}", temp); temp = first / second; Console. Write. Line("Divide: result is {0}", temp); } This code creates two Complex objects that represent the complex values (10 + 4 i) and (5 + 2 i). The code displays them and then tests each of the operators you have just defined, displaying the results in each case.

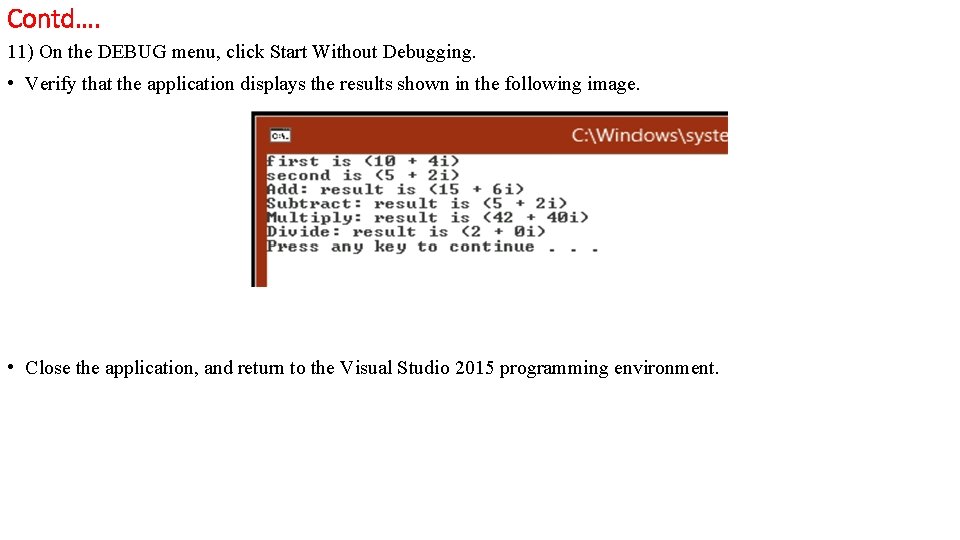

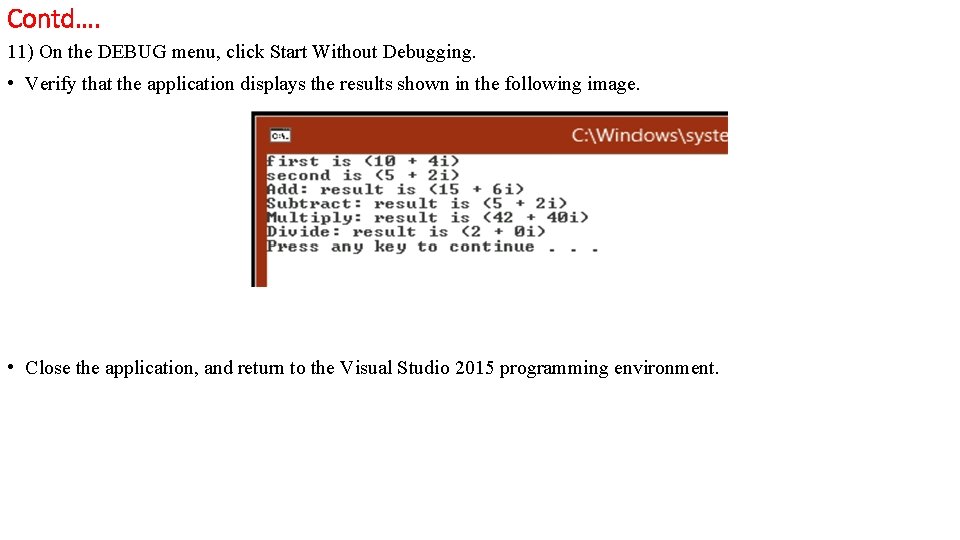

Contd…. 11) On the DEBUG menu, click Start Without Debugging. • Verify that the application displays the results shown in the following image. • Close the application, and return to the Visual Studio 2015 programming environment.

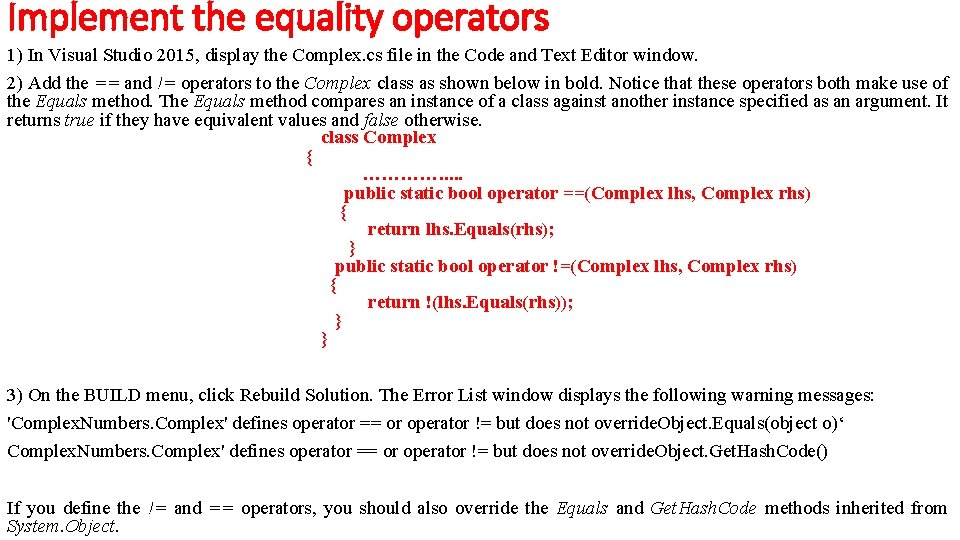

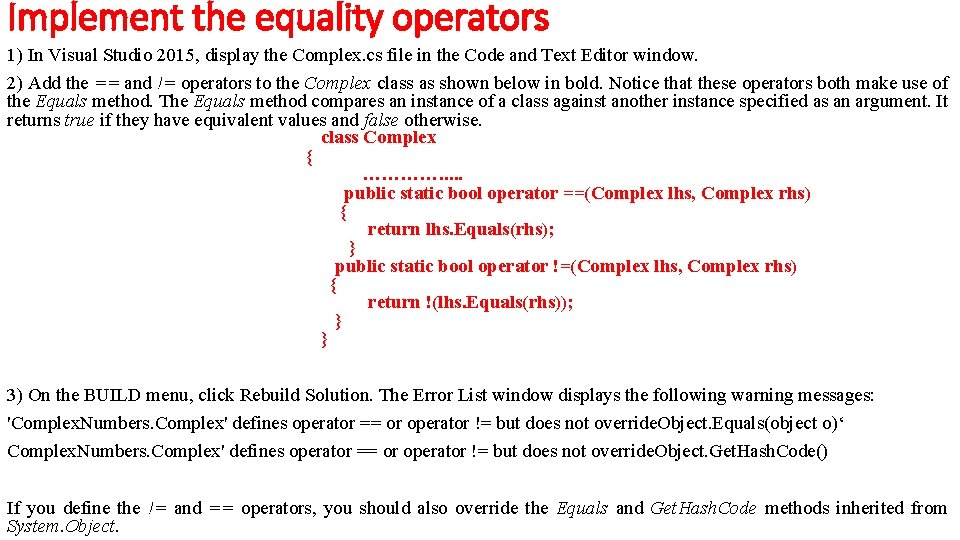

Implement the equality operators 1) In Visual Studio 2015, display the Complex. cs file in the Code and Text Editor window. 2) Add the == and != operators to the Complex class as shown below in bold. Notice that these operators both make use of the Equals method. The Equals method compares an instance of a class against another instance specified as an argument. It returns true if they have equivalent values and false otherwise. class Complex { …………. . . public static bool operator ==(Complex lhs, Complex rhs) { return lhs. Equals(rhs); } public static bool operator !=(Complex lhs, Complex rhs) { return !(lhs. Equals(rhs)); } } 3) On the BUILD menu, click Rebuild Solution. The Error List window displays the following warning messages: 'Complex. Numbers. Complex' defines operator == or operator != but does not override. Object. Equals(object o)‘ Complex. Numbers. Complex' defines operator == or operator != but does not override. Object. Get. Hash. Code() If you define the != and == operators, you should also override the Equals and Get. Hash. Code methods inherited from System. Object.

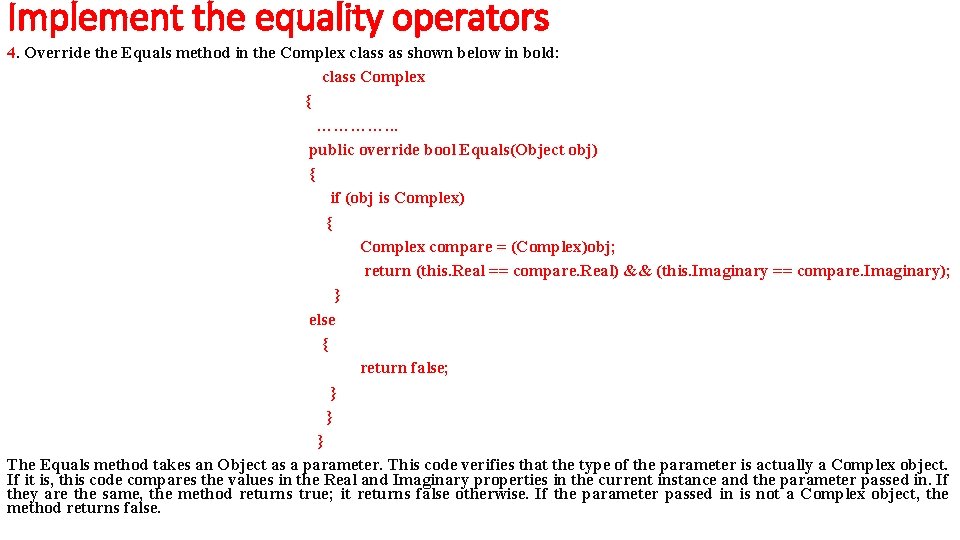

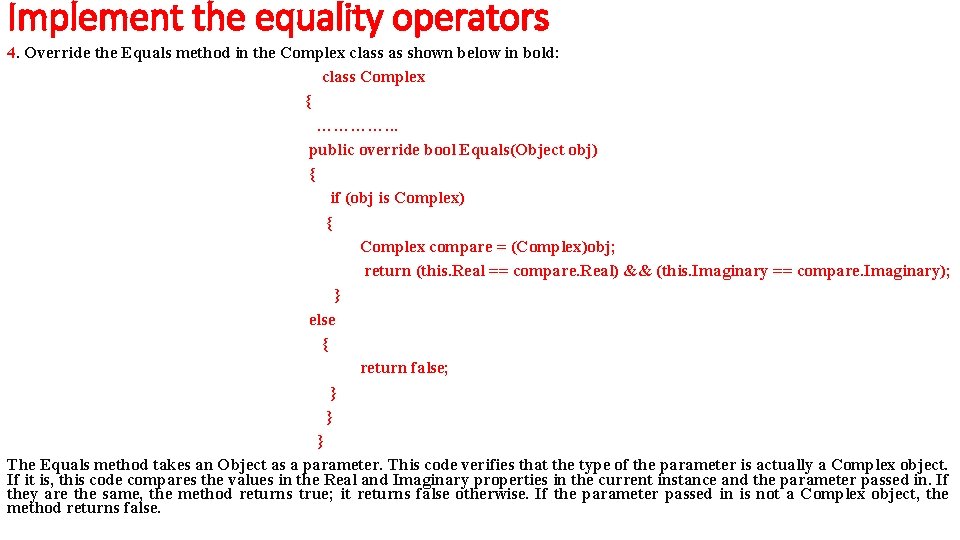

Implement the equality operators 4. Override the Equals method in the Complex class as shown below in bold: class Complex { …………. . . public override bool Equals(Object obj) { if (obj is Complex) { Complex compare = (Complex)obj; return (this. Real == compare. Real) && (this. Imaginary == compare. Imaginary); } else { return false; } } } The Equals method takes an Object as a parameter. This code verifies that the type of the parameter is actually a Complex object. If it is, this code compares the values in the Real and Imaginary properties in the current instance and the parameter passed in. If they are the same, the method returns true; it returns false otherwise. If the parameter passed in is not a Complex object, the method returns false.

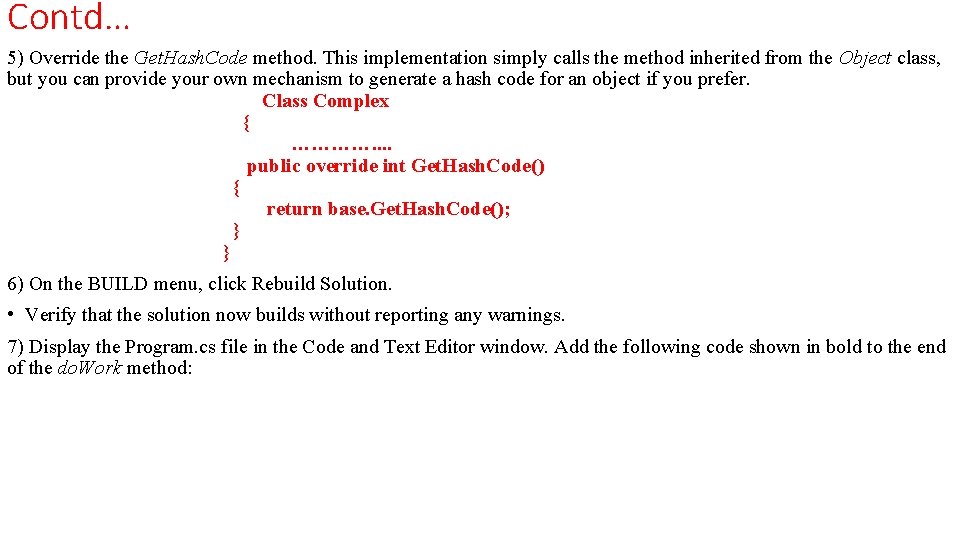

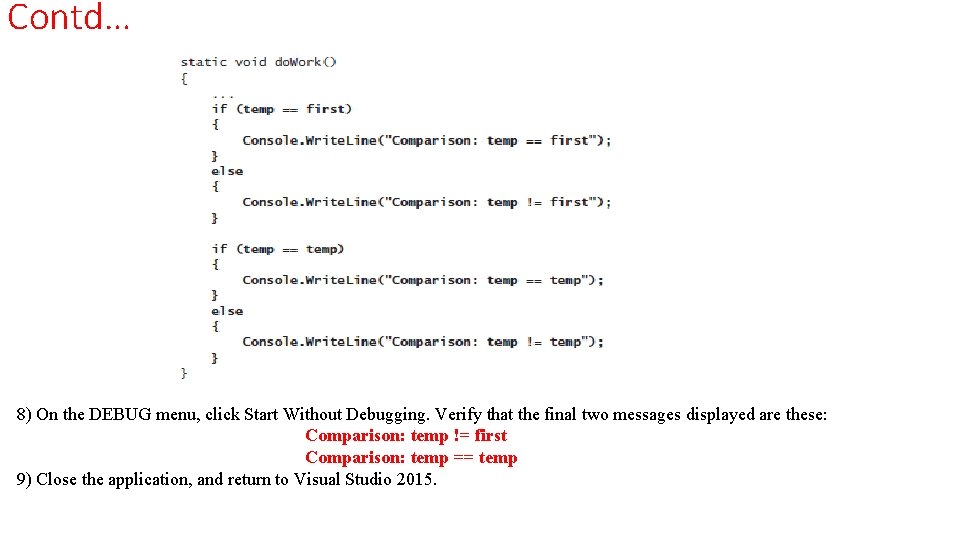

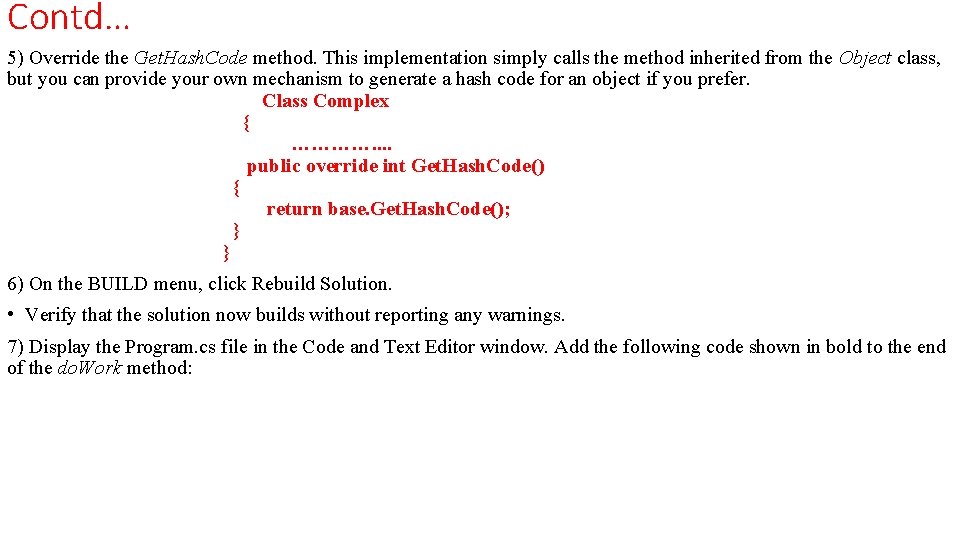

Contd… 5) Override the Get. Hash. Code method. This implementation simply calls the method inherited from the Object class, but you can provide your own mechanism to generate a hash code for an object if you prefer. Class Complex { …………. . public override int Get. Hash. Code() { return base. Get. Hash. Code(); } } 6) On the BUILD menu, click Rebuild Solution. • Verify that the solution now builds without reporting any warnings. 7) Display the Program. cs file in the Code and Text Editor window. Add the following code shown in bold to the end of the do. Work method:

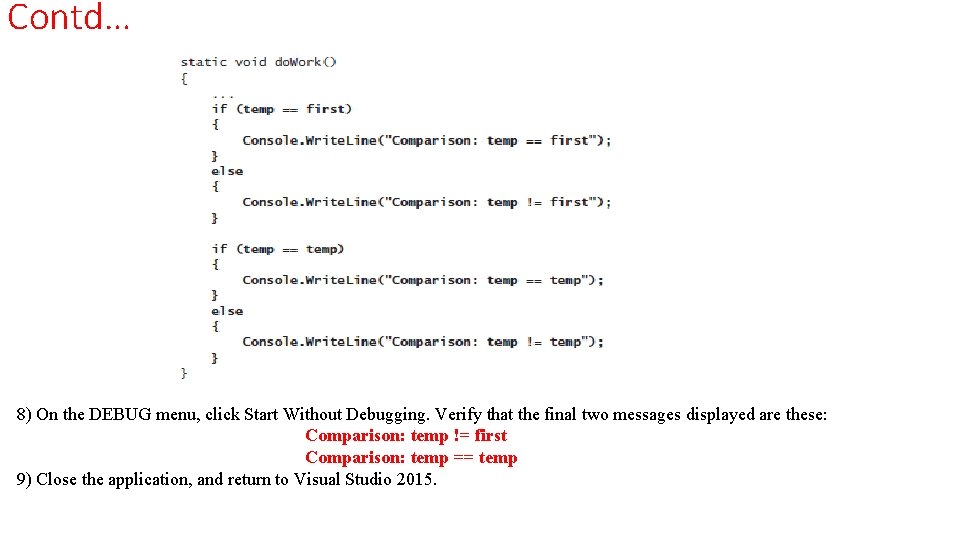

Contd… 8) On the DEBUG menu, click Start Without Debugging. Verify that the final two messages displayed are these: Comparison: temp != first Comparison: temp == temp 9) Close the application, and return to Visual Studio 2015.

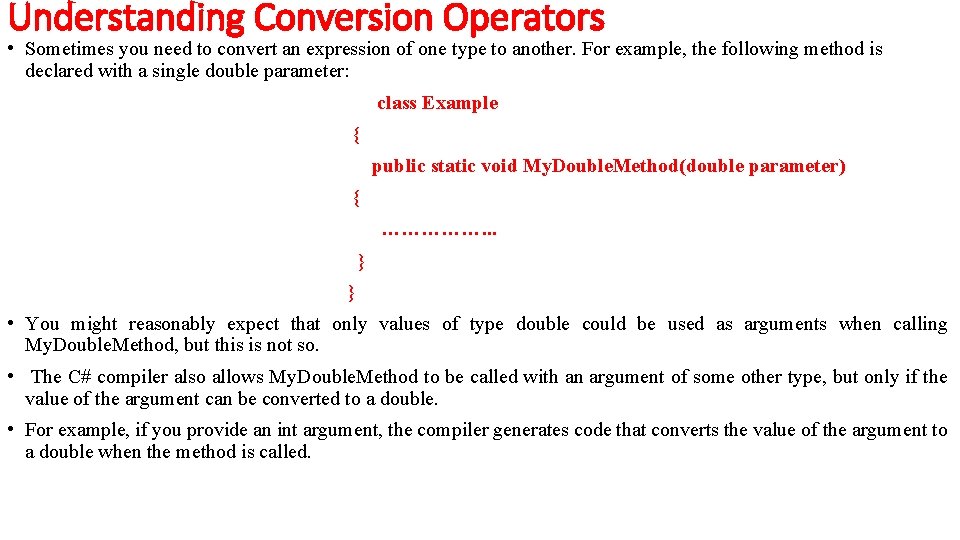

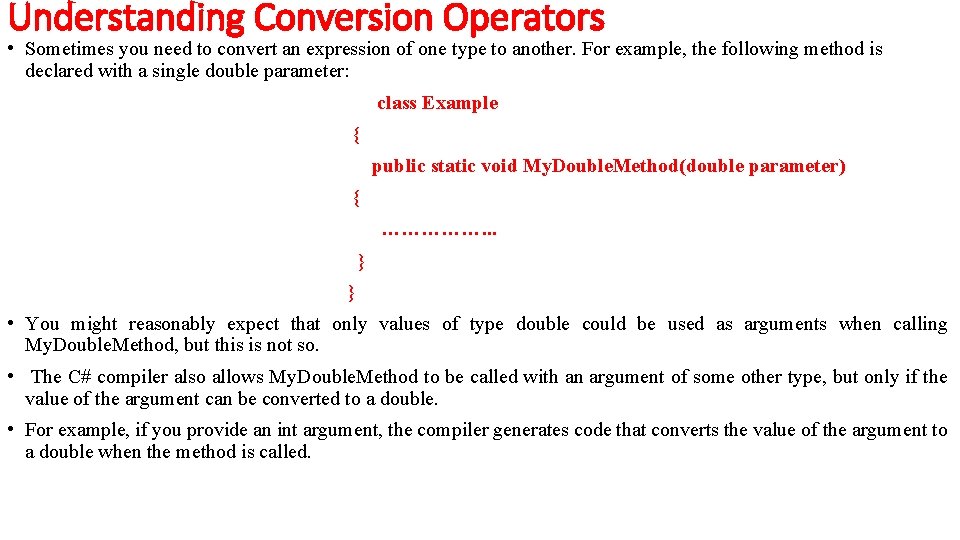

Understanding Conversion Operators • Sometimes you need to convert an expression of one type to another. For example, the following method is declared with a single double parameter: class Example { public static void My. Double. Method(double parameter) { ……………. . . } } • You might reasonably expect that only values of type double could be used as arguments when calling My. Double. Method, but this is not so. • The C# compiler also allows My. Double. Method to be called with an argument of some other type, but only if the value of the argument can be converted to a double. • For example, if you provide an int argument, the compiler generates code that converts the value of the argument to a double when the method is called.

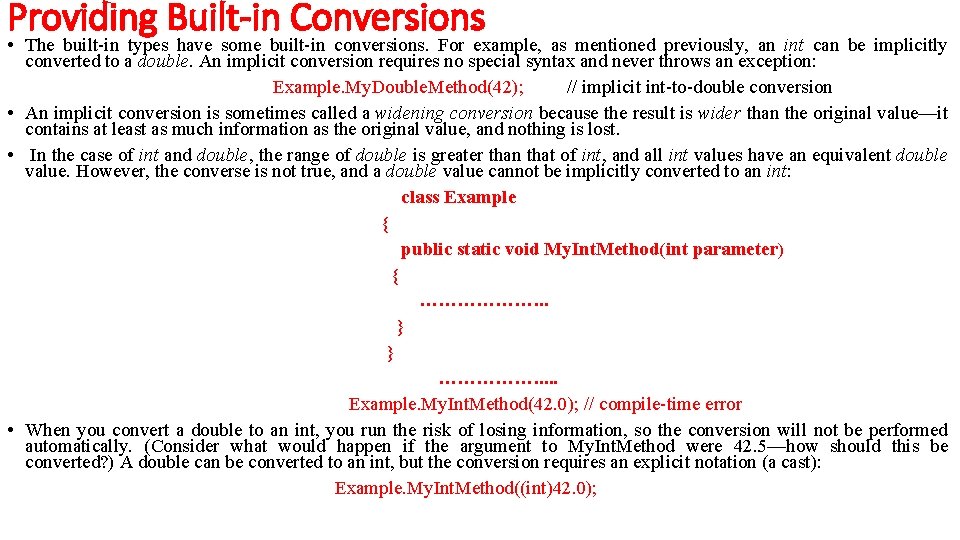

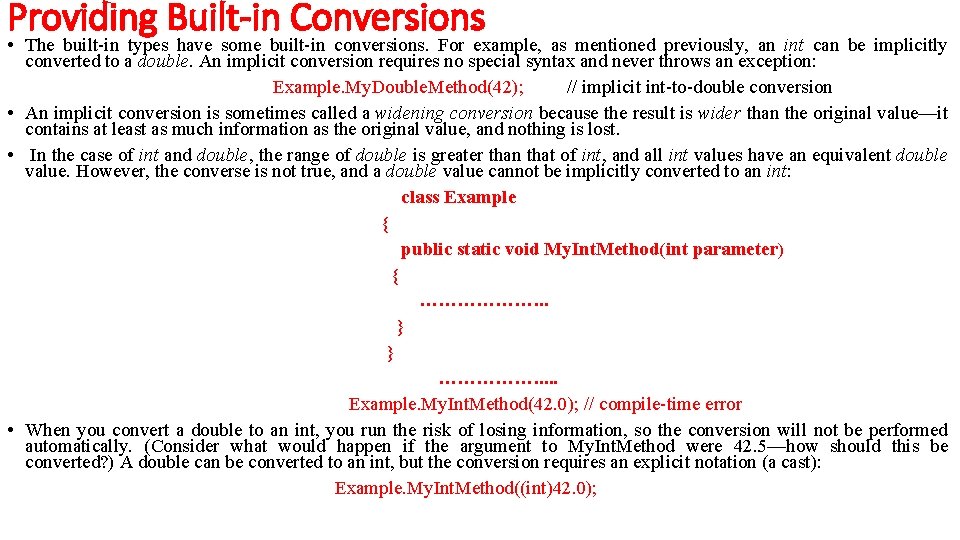

Providing Built-in Conversions • The built-in types have some built-in conversions. For example, as mentioned previously, an int can be implicitly converted to a double. An implicit conversion requires no special syntax and never throws an exception: Example. My. Double. Method(42); // implicit int-to-double conversion • An implicit conversion is sometimes called a widening conversion because the result is wider than the original value—it contains at least as much information as the original value, and nothing is lost. • In the case of int and double, the range of double is greater than that of int, and all int values have an equivalent double value. However, the converse is not true, and a double value cannot be implicitly converted to an int: class Example { public static void My. Int. Method(int parameter) { ………………. . . } } ……………. . . Example. My. Int. Method(42. 0); // compile-time error • When you convert a double to an int, you run the risk of losing information, so the conversion will not be performed automatically. (Consider what would happen if the argument to My. Int. Method were 42. 5—how should this be converted? ) A double can be converted to an int, but the conversion requires an explicit notation (a cast): Example. My. Int. Method((int)42. 0);

Contd… • An explicit conversion is sometimes called a narrowing conversion because the result is narrower than the original value (that is, it can contain less information) and may throw an Overflow. Exception exception if the resulting value is out of the range of the target type. • C# allows you to create conversion operators for your own user-defined types to control whether it is sensible to convert values to other types, and you can also specify whether these conversions are implicit or explicit.

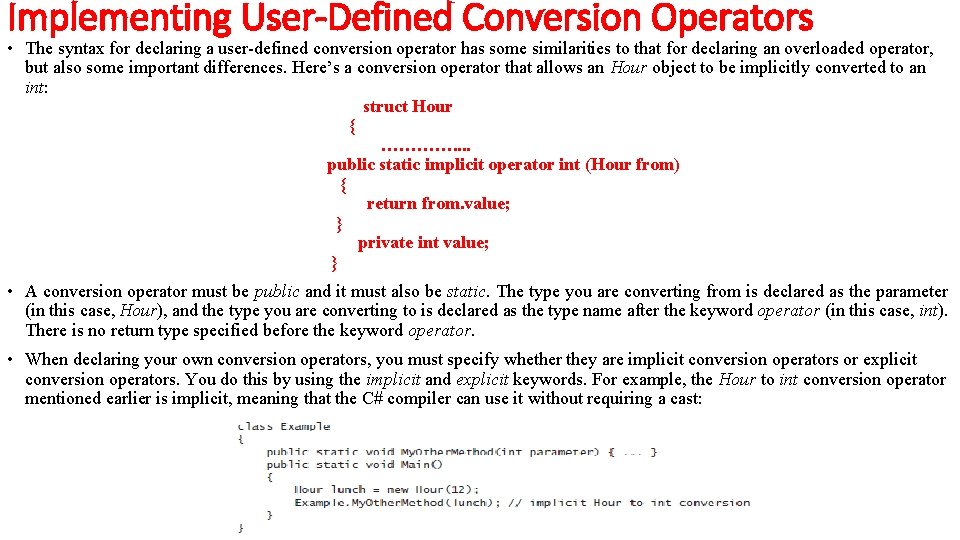

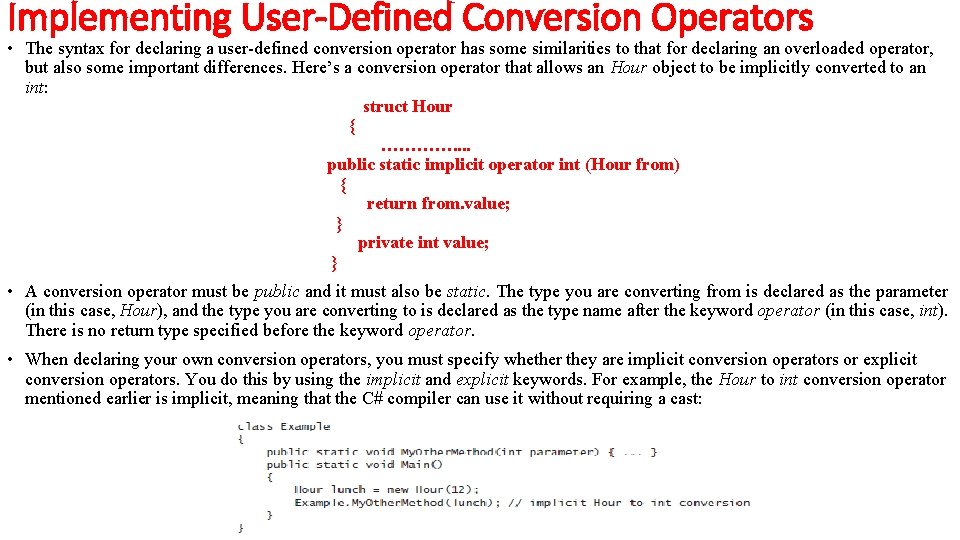

Implementing User-Defined Conversion Operators • The syntax for declaring a user-defined conversion operator has some similarities to that for declaring an overloaded operator, but also some important differences. Here’s a conversion operator that allows an Hour object to be implicitly converted to an int: struct Hour { …………. . public static implicit operator int (Hour from) { return from. value; } private int value; } • A conversion operator must be public and it must also be static. The type you are converting from is declared as the parameter (in this case, Hour), and the type you are converting to is declared as the type name after the keyword operator (in this case, int). There is no return type specified before the keyword operator. • When declaring your own conversion operators, you must specify whether they are implicit conversion operators or explicit conversion operators. You do this by using the implicit and explicit keywords. For example, the Hour to int conversion operator mentioned earlier is implicit, meaning that the C# compiler can use it without requiring a cast:

Contd… • If the conversion operator had been declared explicit, the preceding example would not have compiled, because an explicit conversion operator requires a cast: Example. My. Other. Method((int)lunch); // explicit Hour to int conversion When should you declare a conversion operator as explicit or implicit? If a conversion is always safe, does not run the risk of losing information, and cannot throw an exception, it can be defined as an implicit conversion. • Otherwise, it should be declared as an explicit conversion. Converting from an Hour to an int is always safe—every Hour has a corresponding int value—so it makes sense for it to be implicit. • An operator that converts a string to an Hour should be explicit because not all strings represent valid Hours. (The string “ 7” is fine, but how would you convert the string “Hello, World” to an Hour? )