Module 2 Morphology and Creating Words Things to

- Slides: 26

Module 2 Morphology and Creating Words

Things to know for this lesson This week, we’ll be developing a few rules, and creating some words �� We’ll be working in steps. As part of this lesson, I’ve also included examples of me working through the same process to create two new languages, so you can see what all this looks like. But don’t let what I’ve created influence you. Before we start, I need to clarify something I stumbled on last week. For consonant and vowel blends, you can have more than two phonemes together. You can stack up to eight consonants or vowels together in a word. I don’t recommend that, but it is allowable in many languages, especially with vowels. I say this, because this week we’re getting into word building rules, and I want to make sure you understand that if phonemes don’t blend, they can’t be together in a word. If you didn’t realize that and what to make some more consonant or vowel blends, definitely go ahead and do that now. However, you don’t need to. Some natural languages don’t allow any blending, it’s strictly one consonant phoneme, followed by one vowel phoneme. Most languages fall somewhere in between. Let’s get started.

Step 1 – Initials, Mid-Words and Finals Any word made up of more than one phoneme has a beginning (Initial sounds) and an end (final sound). Three or more means it has a middle. Now you get to decide which of your phonemes are allowed to go in those three spots. You don’t have to do this step. Most natural languages do, and it gives a sense of structure and consistency to words. Sort of a family resemblance. But there are many languages that have very few rules in this area. If that’s what you want, you can simply say that any of your consonants, vowels or blends can go anywhere in a word. But if you do want to take this step, look over your phonemes. Think about how you want your language to sound. Play around with how certain phonemes will sounds at the beginning of a word vs the end. What about mid-word phonemes? As a general rule, natural languages put fewer limits on mid-word phonemes, but you can create whatever rules you like.

Exercise One: Create Your Phoneme Rules 1. List your initial phonemes: 2. List your mid-word phonemes: 3. List your final phonemes:

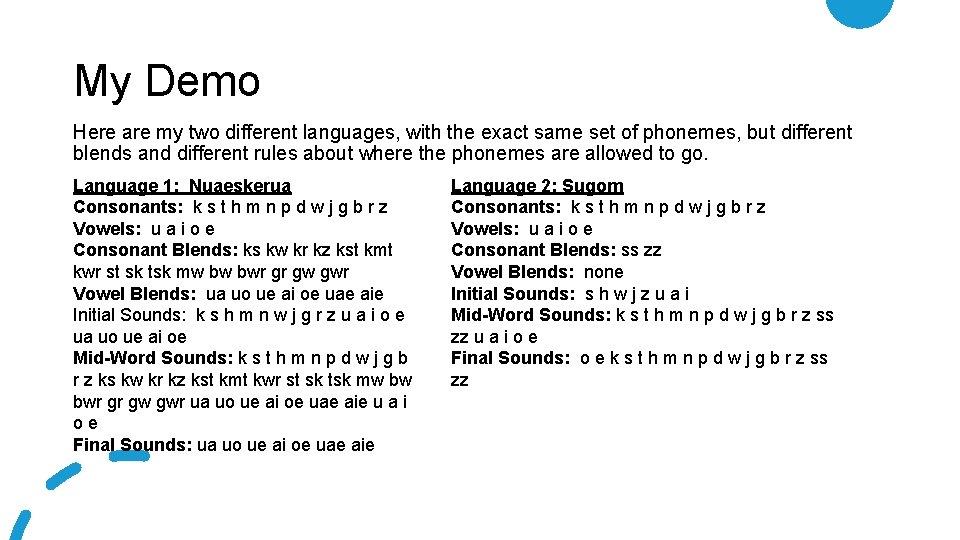

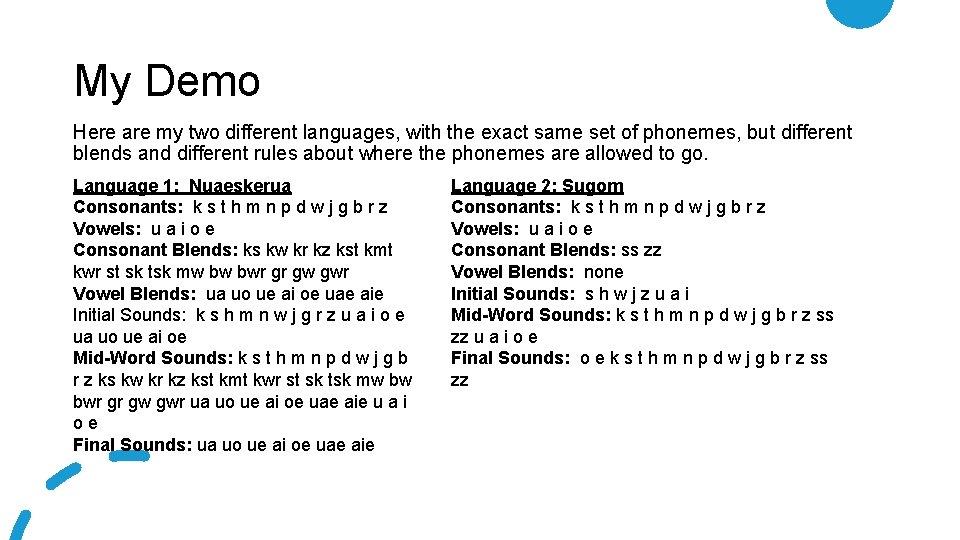

My Demo Here are my two different languages, with the exact same set of phonemes, but different blends and different rules about where the phonemes are allowed to go. Language 1: Nuaeskerua Consonants: k s t h m n p d w j g b r z Vowels: u a i o e Consonant Blends: ks kw kr kz kst kmt kwr st sk tsk mw bw bwr gr gw gwr Vowel Blends: ua uo ue ai oe uae aie Initial Sounds: k s h m n w j g r z u a i o e ua uo ue ai oe Mid-Word Sounds: k s t h m n p d w j g b r z ks kw kr kz kst kmt kwr st sk tsk mw bw bwr gr gw gwr ua uo ue ai oe uae aie u a i oe Final Sounds: ua uo ue ai oe uae aie Language 2: Sugom Consonants: k s t h m n p d w j g b r z Vowels: u a i o e Consonant Blends: ss zz Vowel Blends: none Initial Sounds: s h w j z u a i Mid-Word Sounds: k s t h m n p d w j g b r z ss zz u a i o e Final Sounds: o e k s t h m n p d w j g b r z ss zz

Exercise Two: Create A List of Potential Conlang Words Go back to your list of phonemes, and, if you took that step, your initials, mid-words and finals. Start fitting together phonemes. Play around with word length. Some languages like really long words, others prefer short words. Most tend to vary. Can any of your phonemes stand on their own, as a single word, like English’s pronoun “I” or article “a? ” You aren’t pairing any of these words up with meanings yet, your just creating words in your conlang and finding ones that you like.

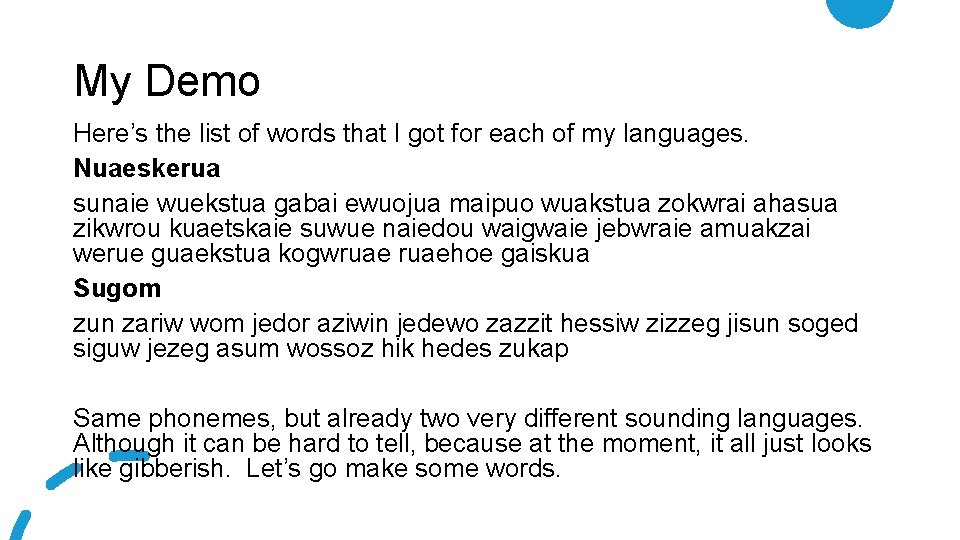

My Demo Here’s the list of words that I got for each of my languages. Nuaeskerua sunaie wuekstua gabai ewuojua maipuo wuakstua zokwrai ahasua zikwrou kuaetskaie suwue naiedou waigwaie jebwraie amuakzai werue guaekstua kogwruaehoe gaiskua Sugom zun zariw wom jedor aziwin jedewo zazzit hessiw zizzeg jisun soged siguw jezeg asum wossoz hik hedes zukap Same phonemes, but already two very different sounding languages. Although it can be hard to tell, because at the moment, it all just looks like gibberish. Let’s go make some words.

My Warning To You On Word Creation I strongly recommend against sitting down with a dictionary or the glossary of a language textbook, and translating every single word you see (That was what I tried to do with my first conlang). That is a great way to get bored and even burn out on your conlang. You would also be translating a lot of words that you don’t need, as dictionaries are full of specialized jargon, loan words, and the like. And you’ll be far more likely to inadvertently create a coded copy of your native language. Instead, we’ll use the Swadesh List

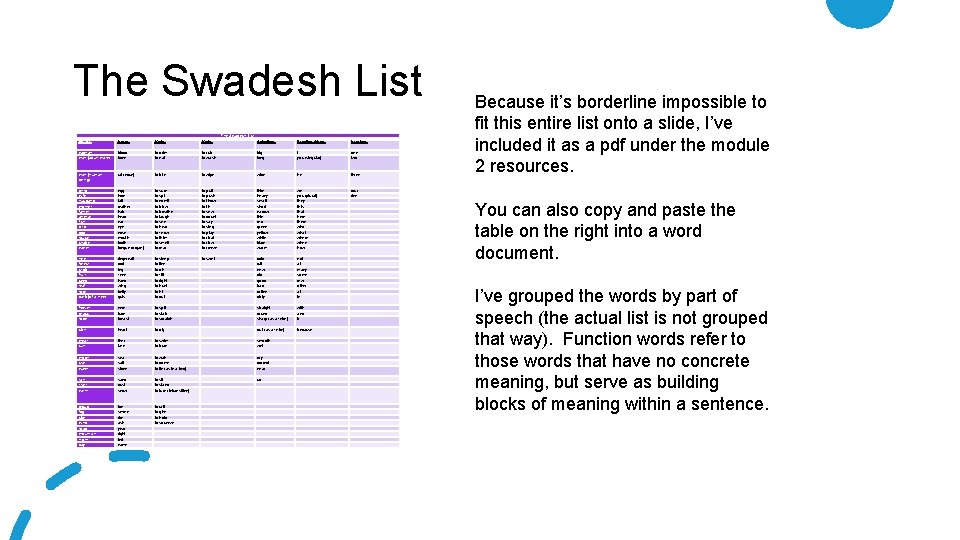

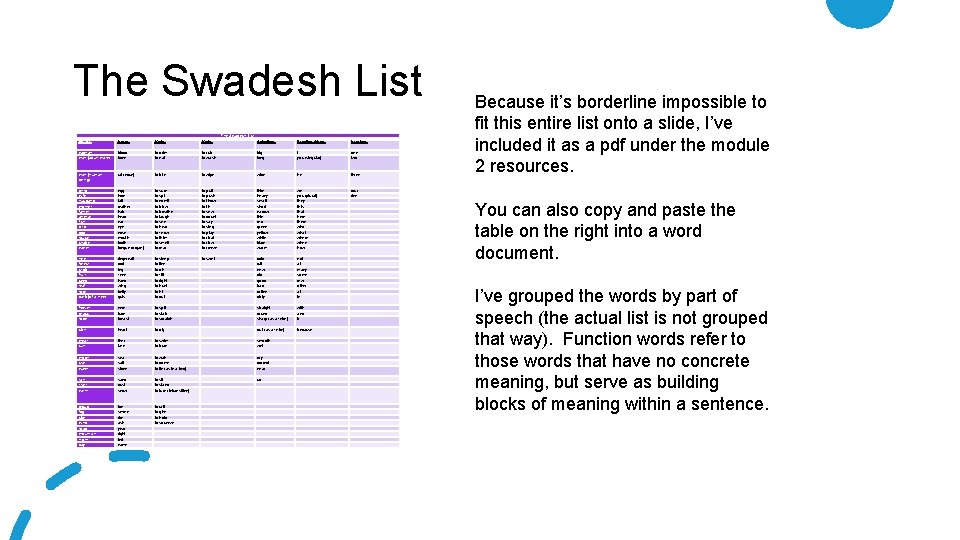

Step 2: Building Your Conlang Vocabulary The Swadesh List was originally a list of 100 words that were found to be universal to all languages, regardless of region or culture. The list has since been expanded to 207 words, and it is a perfect guide for conlanging, especially if you aren’t sure where to start. These are words that are, more or less, found in every human language. In some cases, two words on the English Swadesh list might be the same word in another language. And colors and numbers have turned out to be less consistent across languages than originally thought. But we’ll get to that.

The Swadesh List Nouns Verbs Adjectives Function Words Numbers woman (adult male) blood bone to drink to eat to rub to wash big long I you (singular) one two man (human being) fat (noun) to bite to wipe wide he three child wife husband mother father animal fish bird dog louse snake worm egg horn tail feather hair head ear eye nose mouth tooth tongue (organ) to suck to spit to vomit to blow to breathe to laugh to see to hear to know to think to smell to fear to pull to push to throw to tie to sew to count to say to sing to play to float to flow to freeze thick heavy small short narrow thin red green yellow white black warm we you (plural) they this that here there who what where when how four five tree forest stick fruit seed leaf root bark (of a tree) fingernail foot leg knee hand wing belly guts to sleep to live to die to kill to fight to hunt to hit to cut to swell cold full new old good bad rotten dirty not all many some few other at in flower grass rope neck back breast to split to stab to scratch straight round sharp (as a knife) with and if skin heart to dig dull (as a knife) because meat sun liver lake to swim to burn smooth wet moon star water sea salt stone to walk to come to lie (as in a bed) dry correct near rain river earth sand dust snow to sit to stand to turn (intransitive) far cloud fog sky wind road mountain night day ice smoke fire ash year right left name to fall to give to hold to squeeze Because it’s borderline impossible to fit this entire list onto a slide, I’ve included it as a pdf under the module 2 resources. You can also copy and paste the table on the right into a word document. I’ve grouped the words by part of speech (the actual list is not grouped that way). Function words refer to those words that have no concrete meaning, but serve as building blocks of meaning within a sentence.

Exercise Three: Create a List of Words You Want to Translate After you’ve looked over the Swadesh list, think about the first words you would like to build for your language. Create a list of 10 -15 words, still keeping them in your native language for the moment. Stick with nouns, verbs and adjectives for now. We’ll get into functional words later. The whole list does not have to be words from the Swadesh list. If there are words that you know are important to your speakers, go ahead and add those.

Exercise Four: Assign a conlang word to each word on your list. Take out the list of meanings you want to assign your conlang words to. Match up conlang words to meanings in whatever way suits you. There is no right or wrong here. Have fun. At the end, you should have a list of 10 -15 nouns, verbs and adjectives, all with concrete meanings.

Step 3: Noun and Verb Classes *Note: gender in linguistics has very little to do with how gender is used in typical conversation. So to avoid confusion, we’re going to call these noun classes. * Noun classes occur in two basic systems, that tend to intermingle, especially when you have more than three. You either have Masculine, Feminine (and sometimes neuter) or Animate and Inanimate.

Masculine and Feminine Systems Masculine and Feminine systems will often apply those classes to people as we would aspect, so men, boys, husbands, etc will be masculine, while women, girls and wives are feminine. But then every other noun will be sorted under either masculine or feminine, and it’s often completely arbitrary. There might be a sense of association, i. e. the sun is viewed as masculine while the moon is feminine. But in German a spoon is masculine and a fork is feminine, and German speakers don’t associate either utensil with being more or less manly. It’s often a linguistic accident, caused by a number of complex factors. Languages with a neuter class also don’t just throw everything not associated with male or female into that neuter class. As indicated above, German assigns most words randomly to any of its three classes, even ones we might think should go with a particular class. Mädchen, girl in German, is neuter. Go figure.

Animate and Inanimate Systems Moving away from Masculine and Feminine systems, we have Animate and Inanimate, which is just as common in noun class systems around the world. This can be as straightforward or as counter intuitive as Masculine/Feminine systems, depending on the word. Humans and animals are often animate, while tools and rocks are inanimate. But a tree, as they tend to be stationary, might be inanimate, while a river is animate. And again, sometimes it’s just plain random, no matter what. A river might be inanimate, but rain is animate. Maybe a tree is animate, but other plants are inanimate.

Mixed Systems And these systems do mix once you bring in multiple noun classes. Here’s an example of a four class system: • • Masculine Animate (male people, animals, certain tools, and other stuff) Feminine animate (female people, celestial bodies, certain tools and other stuff) Animate (other stuff that moves around, like wind) Inanimate (stuff that doesn’t move around, like rocks) Those descriptions might sound silly, but that really is what you get with noun classes in natural languages. There’s a system of classes that seems straightforward, then it gradually becomes less straightforward as you learn more nouns and which class they go into.

Summing Up Noun Classes To sum up, if you’re going with noun class, yes you do want to assign some words in a way that makes sense to whoever speaks the language. For human speakers, that probably means male humans are masculine and female humans are feminine, or that humans and animals are animate, while rocks are inanimate. But beyond that, those distinctions get looser, and for some words get tossed out the window. If your speakers have a very unique culture, or are not human at all, you might consider some other class categories.

Noun Affixes In terms of sound association, a lot of languages with noun classes do have a particular noun affix (suffix or prefix) they associate with each class. This can be a single phoneme, like Spanish’s “a” or “o” or it can be a more complex blend of phonemes. Some languages do use prefix, so all nouns of a certain class will start with “m” while others all start with “n. ” Or a language might not associate a particular affix with each noun class. A language could also have an affix that marks a word as a noun, independent of noun class. One last thing to consider, noun classes often, though not always, dictate difference in how nouns are marked for case (declension, which we will talk about next week)

Exercise Five: Assign Noun Classes • Does your language have noun classes? • If so, how many? (I recommend no more than four, if this is your first conlang. Don’t overwhelm yourself) • Are there affixes associated with each noun class? What are those affixes? Take a look at the nouns you created and make any adjustments as needed.

Verb Classes Verb classes are often even messier and arbitrary than noun classes. They might be assigned to certain aspects, such as whether a verb describes a physical action (run, jump, kick) or a passive action (sleep, think, dream) or a grammatical action (helper verbs �� ) They might be assigned to less obvious grammatical features, such as whether the verb can take one object, two objects or no objects (transitivity). While many languages have verb classes (usually denoted via affix and/or differing conjugation rules) it’s rare for common speakers to group them based on obvious or even imagined qualities in the same way noun classes do. Verb classes are more commonly associated with specific conjugation rules. In Spanish, you learn the three verb classes (-ar, -er and -ir) so you know how to conjugate them properly. Different noun classes are just as likely to use the same case marking, but different verb classes far more often have different conjugation rules. Verbs might be assigned a common verb affix, different affixes dependent on their class, or no affix at all.

Exercise Six: Assign Verb Classes • Does you language have verb classes? • If so, how many (I recommend a limit of three here, because you don’t want to get bogged done in more than three different conjugation systems) • Are there affixes associate with each verb class, or a general verb affix? If so, what are they? Assign affixes to your verbs as needed.

Nouns that Verb and Verbs that are Nouns This final step, to me, is the most fun. You don’t need to do it, but it’s a really good way to make your language unique, and avoid creating a code of your native language. You should now have a handful of nouns and/or verbs. We’ll start with the nouns, if you have any. Here are mine nouns for Nuaeskerua: • • • woman - sunaie man - suwue child – ahasua wife - kuaetskaie husband - werue

Playing with Nouns I’m going to randomly choose one word from the list, child. I know what the noun child means, but what could the verb “to child” mean. You can go with the most intuitive answer, perhaps in this case, simply “to be a child. ” This would give you a noun and verb that are clearly based on the same root. But for this exercise, dig deeper, and you see if you find other ideas. To child might mean “to play” or “to be mischievous. ” Maybe it means “to resemble someone, ” as children often look like their parents or other relatives. Maybe it means “to wander into danger unheeded, ” because kids tend to do that. I like that one, so I’ll go with that. I’ll drop the noun suffix “ua” from child and add on a verb suffix “ruo. ” So now ahasua means child, and ahaseruo means “to wander into danger unheeded. ”

Wait, What Are We Doing? Understand, we’re not making idioms or slang. Speakers of this language will not directly associate these two words with each other, in the same that English speakers don’t readily think about the fact that the word “understand” is made of two separate words that have nothing to do with comprehension. We’re doing three specific things: • Creating relationships between words to show they are from the same language • Creating words that don’t translate perfectly into other languages • Creating concepts that matter to your speakers

Playing with Verbs Let’s do the same with verbs This time, I’ll grab my Sogom verb list. • to drink – zun • to eat - zizzeg • to bite - asum • to suck - hedes • to spit - wom I’m going to randomly pick a word, this time spit. I know what “to spit” means, but what could the noun spit be, besides the very obvious, the stuff that comes out when you spit. Maybe it means “an insult, ” or some sort of curse word. But that’s reflecting my personal/cultural feelings about spitting. I think my Sogom speakers see spitting differently. It’s a way to call for good luck. So in Sogom the noun could mean “luck” or “good wishes. ” I’ll make an adjustment so they don’t look like the exact same word. Now I have the verb wom, which means “to spit” and the noun zewom, which means “good wishes. ” Only do this with one or two nouns or verbs that you’ve created. You don’t want every single word in your conlang to have a highly unique meaning.

Wrapping Up At this point, you should have about 10 – 15 words. Create at least five more words, again sticking with nouns, verbs and adjectives for now. You can create as many as 50, but once you start getting bored, stop. You never want to be bored while working on your conlang. That quickly leads to burn out. Have fun!