Modern Physics vs Classical Physics MODERN PHYSICS Electrons

- Slides: 96

Modern Physics vs Classical Physics

MODERN PHYSICS Electrons Photons J. J. Thompson Robert Millikan Max Planck Albert Einstein Photoelectric Effect Experiment The Graph Energy Levels Absorption/Emission Spectra Bohr Model De Broglie Wavelength X-Ray Production Compton Scattering Nuclear Notation Energy-Mass Equivalence Nuclear Decay Fission Fusion

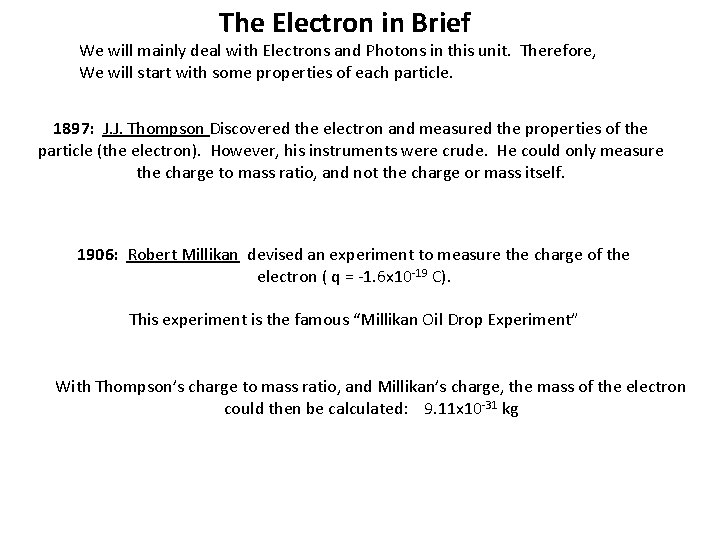

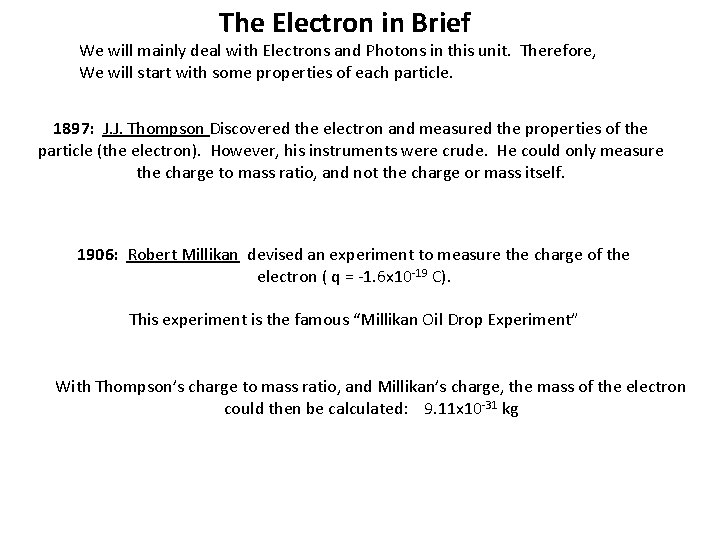

The Electron in Brief We will mainly deal with Electrons and Photons in this unit. Therefore, We will start with some properties of each particle. 1897: J. J. Thomson Discovered the electron and measured the properties of the particle (the electron). However, his instruments were crude. He could only measure the charge to mass ratio, and not the charge or mass itself.

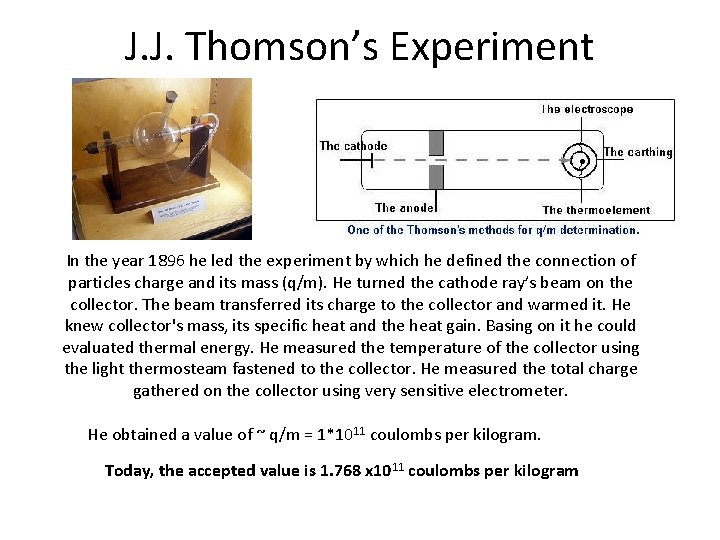

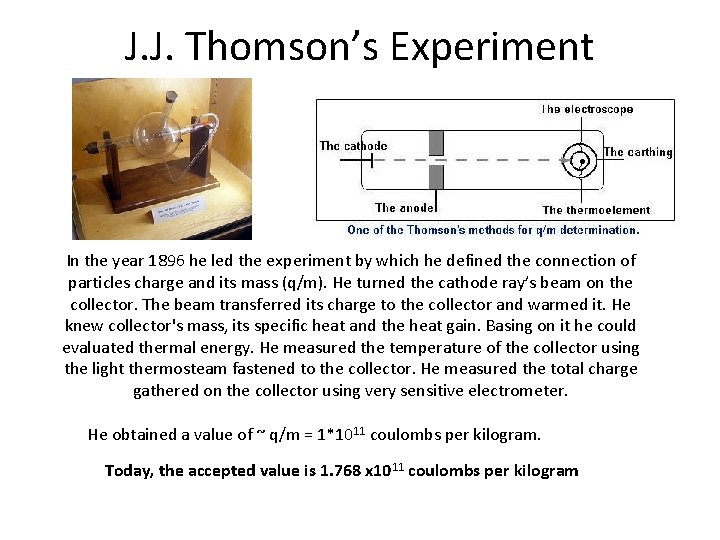

J. J. Thomson’s Experiment

J. J. Thomson’s Experiment In the year 1896 he led the experiment by which he defined the connection of particles charge and its mass (q/m). He turned the cathode ray’s beam on the collector. The beam transferred its charge to the collector and warmed it. He knew collector's mass, its specific heat and the heat gain. Basing on it he could evaluated thermal energy. He measured the temperature of the collector using the light thermosteam fastened to the collector. He measured the total charge gathered on the collector using very sensitive electrometer. He obtained a value of ~ q/m = 1*1011 coulombs per kilogram. Today, the accepted value is 1. 768 x 1011 coulombs per kilogram

The Electron in Brief We will mainly deal with Electrons and Photons in this unit. Therefore, We will start with some properties of each particle. 1897: J. J. Thomson Discovered the electron and measured the properties of the particle (the electron). However, his instruments were crude. He could only measure the charge to mass ratio, and not the charge or mass itself. 1906: Robert Millikan devised an experiment to measure the charge of the electron ( q = -1. 6 x 10 -19 C). This experiment is the famous “Millikan Oil Drop Experiment”

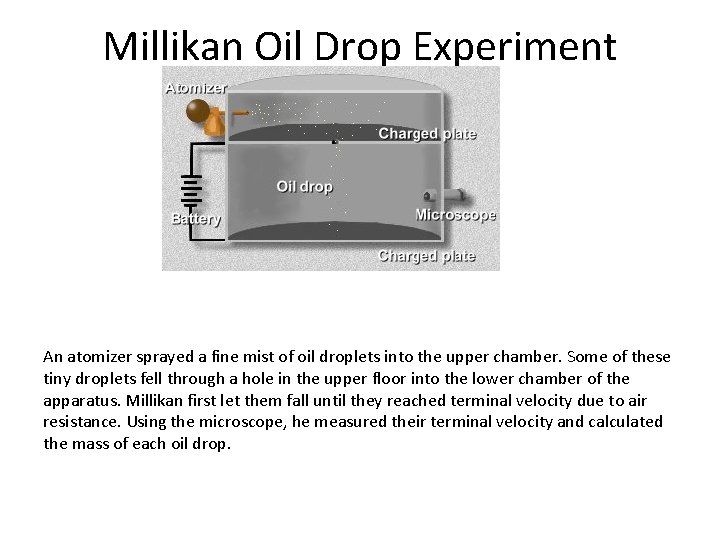

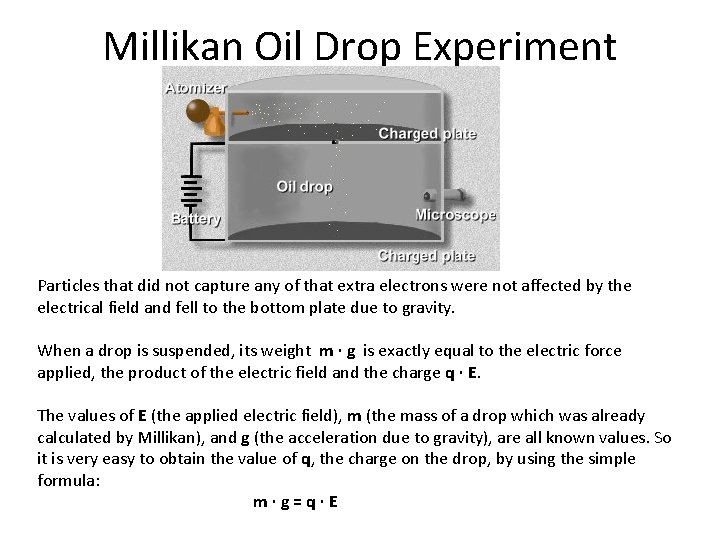

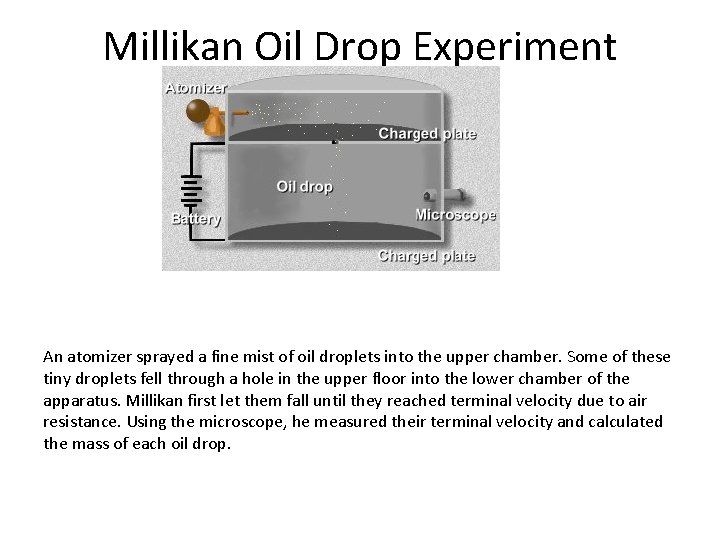

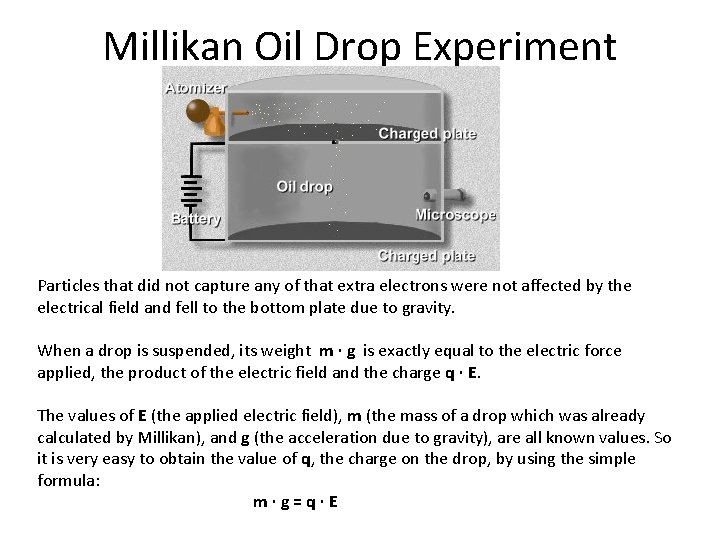

Millikan Oil Drop Experiment An atomizer sprayed a fine mist of oil droplets into the upper chamber. Some of these tiny droplets fell through a hole in the upper floor into the lower chamber of the apparatus. Millikan first let them fall until they reached terminal velocity due to air resistance. Using the microscope, he measured their terminal velocity and calculated the mass of each oil drop.

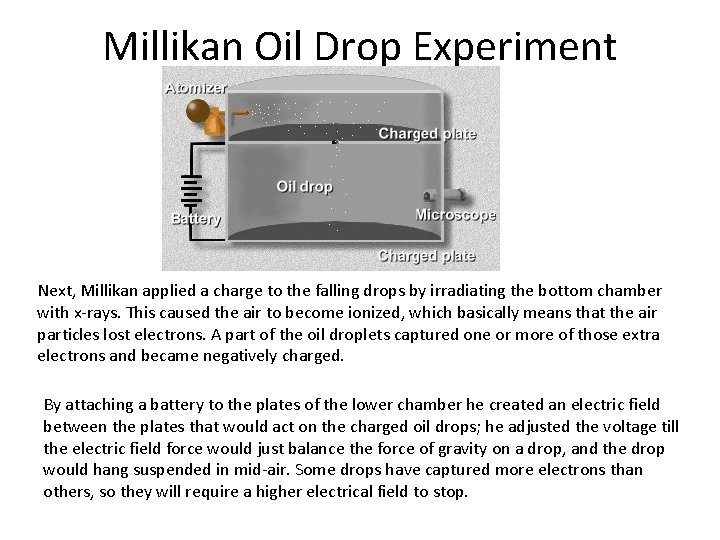

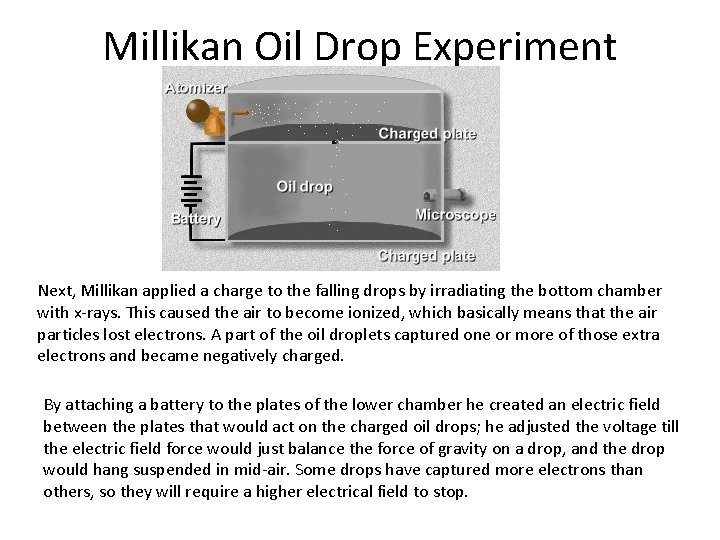

Millikan Oil Drop Experiment Next, Millikan applied a charge to the falling drops by irradiating the bottom chamber with x-rays. This caused the air to become ionized, which basically means that the air particles lost electrons. A part of the oil droplets captured one or more of those extra electrons and became negatively charged. By attaching a battery to the plates of the lower chamber he created an electric field between the plates that would act on the charged oil drops; he adjusted the voltage till the electric field force would just balance the force of gravity on a drop, and the drop would hang suspended in mid-air. Some drops have captured more electrons than others, so they will require a higher electrical field to stop.

Millikan Oil Drop Experiment Particles that did not capture any of that extra electrons were not affected by the electrical field and fell to the bottom plate due to gravity. When a drop is suspended, its weight m · g is exactly equal to the electric force applied, the product of the electric field and the charge q · E. The values of E (the applied electric field), m (the mass of a drop which was already calculated by Millikan), and g (the acceleration due to gravity), are all known values. So it is very easy to obtain the value of q, the charge on the drop, by using the simple formula: m·g=q·E

Millikan Oil Drop Experiment

The Electron in Brief We will mainly deal with Electrons and Photons in this unit. Therefore, We will start with some properties of each particle. 1897: J. J. Thompson Discovered the electron and measured the properties of the particle (the electron). However, his instruments were crude. He could only measure the charge to mass ratio, and not the charge or mass itself. 1906: Robert Millikan devised an experiment to measure the charge of the electron ( q = -1. 6 x 10 -19 C). This experiment is the famous “Millikan Oil Drop Experiment” With Thompson’s charge to mass ratio, and Millikan’s charge, the mass of the electron could then be calculated: 9. 11 x 10 -31 kg

The Photon blackbody radiation In the last quarter of the 1800’s scientists had been working on a way to take what they knew about mechanics, thermodynamics, electricity & magnetism and optics to describe how hot objects cool by giving off light in various parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. The study of this effect is known as blackbody radiation. You have seen blackbody radiation. Any object That is hot enough gives off light (blackbody radiation)

The Photon blackbody radiation You have seen blackbody radiation. Any object that is hot enough gives off light (blackbody radiation)

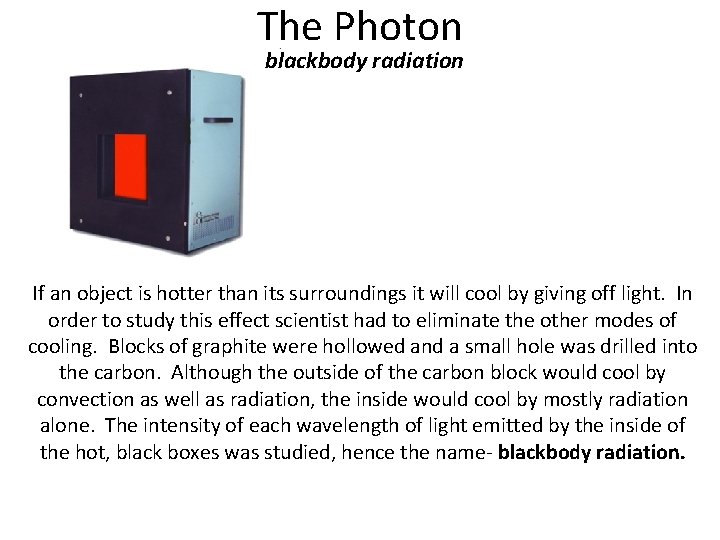

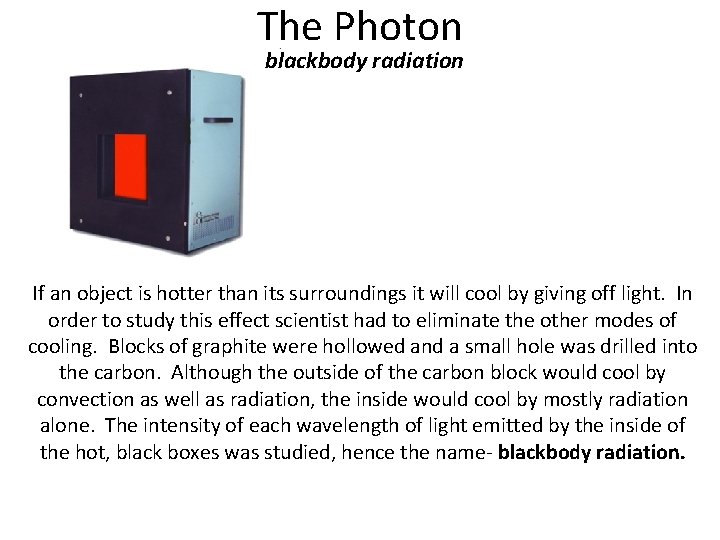

The Photon blackbody radiation If an object is hotter than its surroundings it will cool by giving off light. In order to study this effect scientist had to eliminate the other modes of cooling. Blocks of graphite were hollowed and a small hole was drilled into the carbon. Although the outside of the carbon block would cool by convection as well as radiation, the inside would cool by mostly radiation alone. The intensity of each wavelength of light emitted by the inside of the hot, black boxes was studied, hence the name- blackbody radiation.

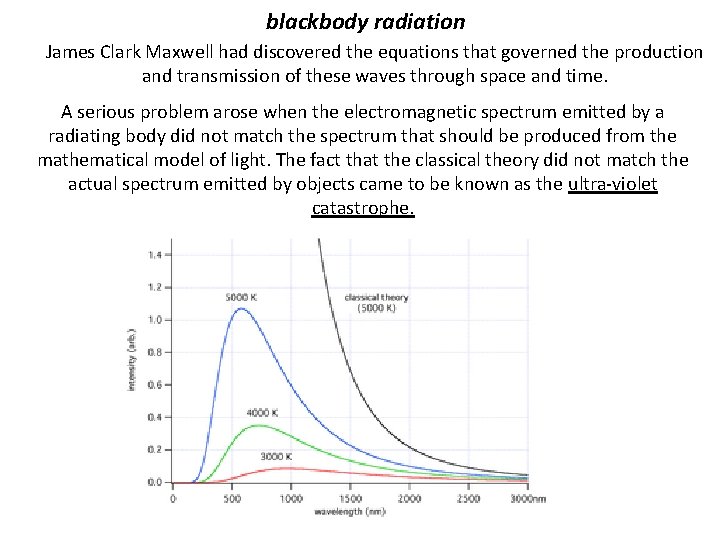

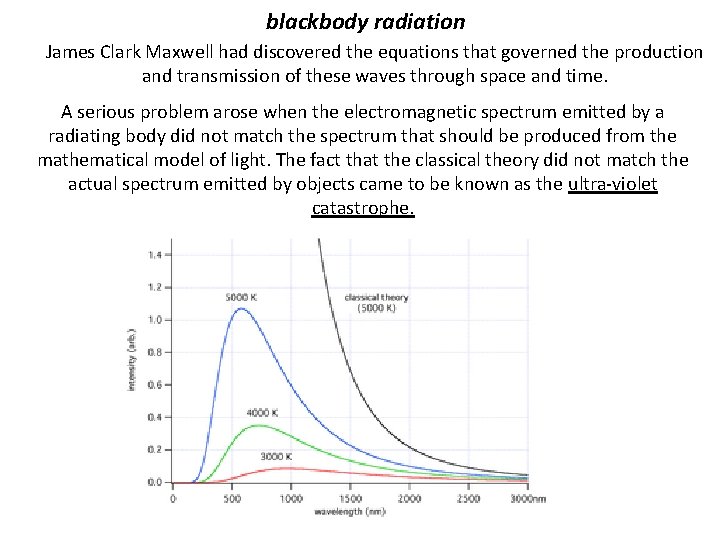

blackbody radiation James Clark Maxwell had discovered the equations that governed the production and transmission of these waves through space and time. A serious problem arose when the electromagnetic spectrum emitted by a radiating body did not match the spectrum that should be produced from the mathematical model of light. The fact that the classical theory did not match the actual spectrum emitted by objects came to be known as the ultra-violet catastrophe.

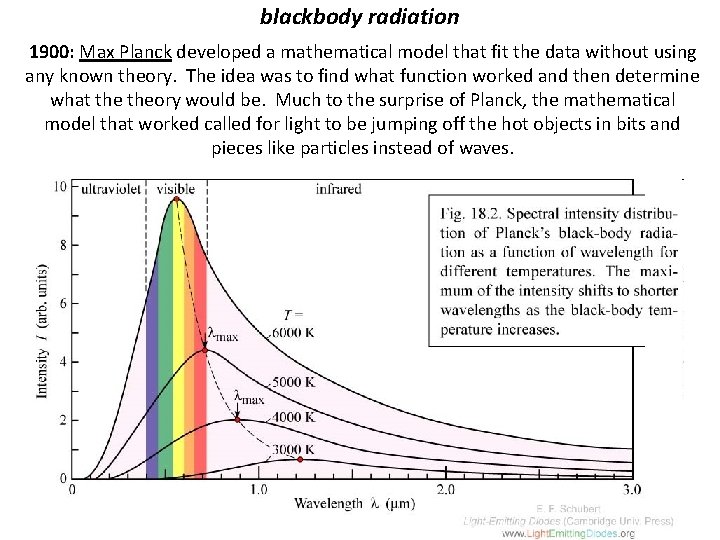

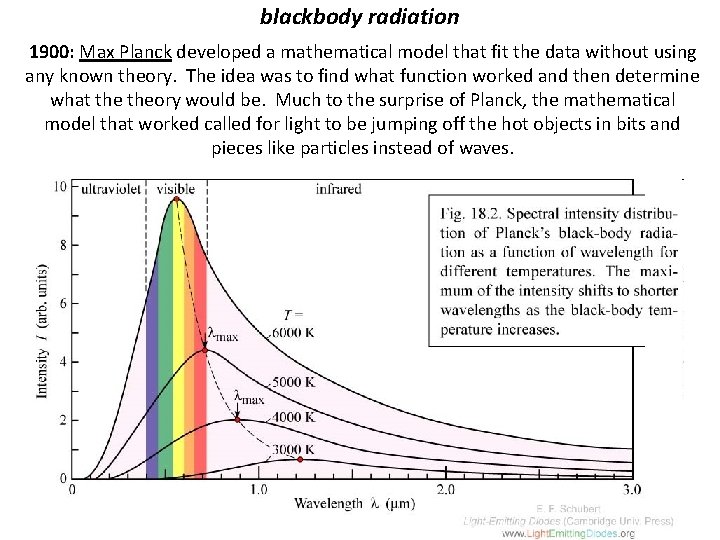

blackbody radiation 1900: Max Planck developed a mathematical model that fit the data without using any known theory. The idea was to find what function worked and then determine what theory would be. Much to the surprise of Planck, the mathematical model that worked called for light to be jumping off the hot objects in bits and pieces like particles instead of waves.

blackbody radiation

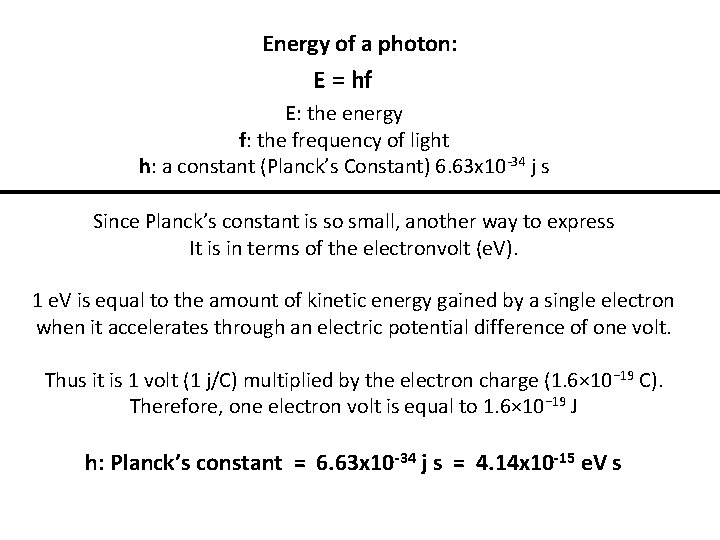

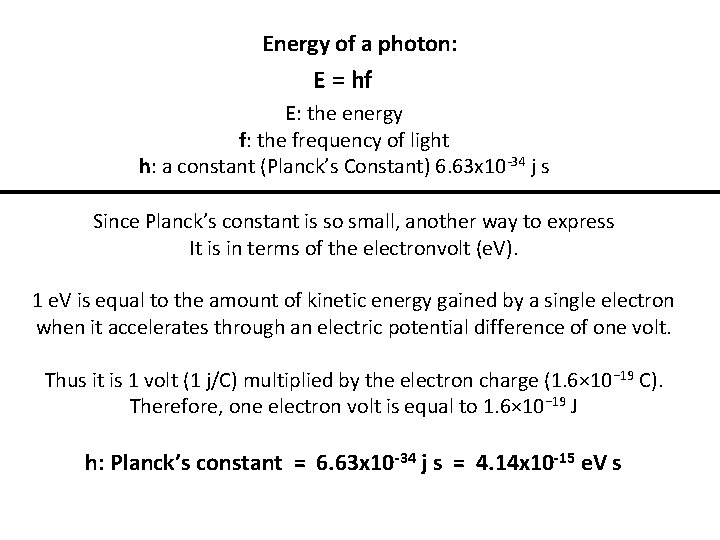

Energy of a photon: E = hf E: the energy f: the frequency of light h: a constant (Planck’s Constant) 6. 63 x 10 -34 j s Since Planck’s constant is so small, another way to express It is in terms of the electronvolt (e. V). 1 e. V is equal to the amount of kinetic energy gained by a single electron when it accelerates through an electric potential difference of one volt. Thus it is 1 volt (1 j/C) multiplied by the electron charge (1. 6× 10− 19 C). Therefore, one electron volt is equal to 1. 6× 10− 19 J h: Planck’s constant = 6. 63 x 10 -34 j s = 4. 14 x 10 -15 e. V s

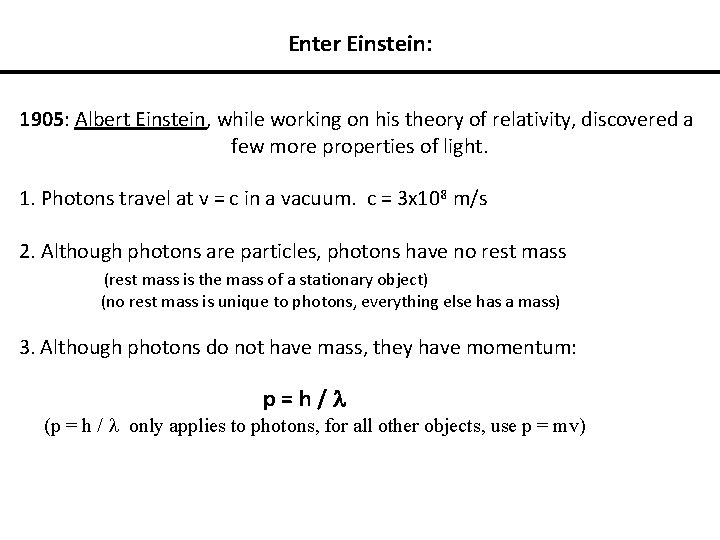

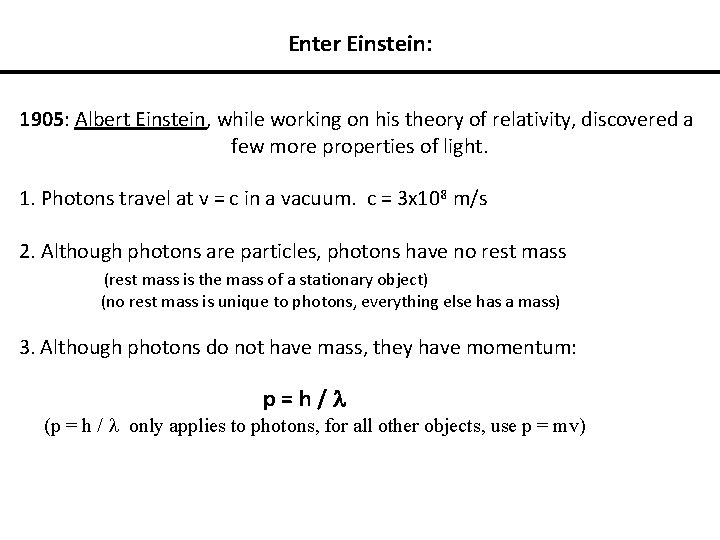

Enter Einstein: 1905: Albert Einstein, while working on his theory of relativity, discovered a few more properties of light. 1. Photons travel at v = c in a vacuum. c = 3 x 108 m/s 2. Although photons are particles, photons have no rest mass (rest mass is the mass of a stationary object) (no rest mass is unique to photons, everything else has a mass) 3. Although photons do not have mass, they have momentum: p = h / (p = h / only applies to photons, for all other objects, use p = mv)

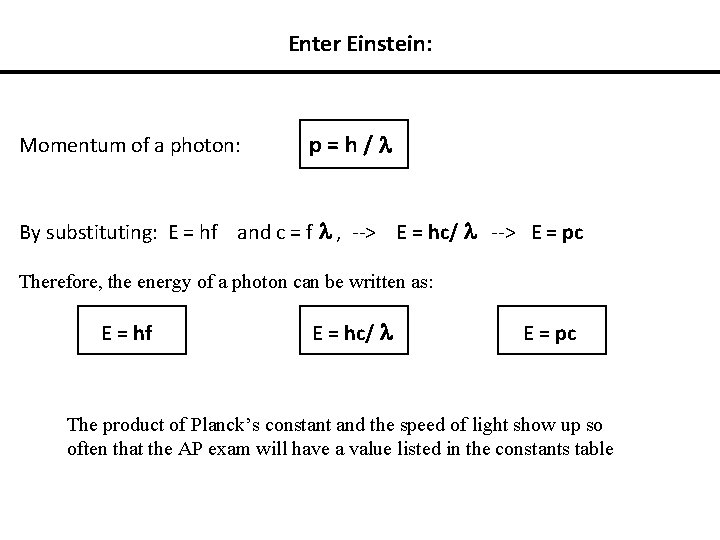

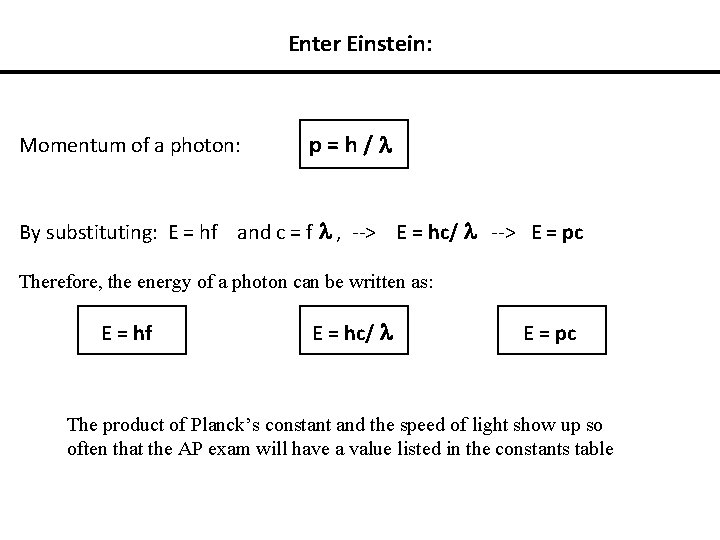

Enter Einstein: Momentum of a photon: p = h / By substituting: E = hf and c = f , --> E = hc/ --> E = pc Therefore, the energy of a photon can be written as: E = hf E = hc/ E = pc The product of Planck’s constant and the speed of light show up so often that the AP exam will have a value listed in the constants table

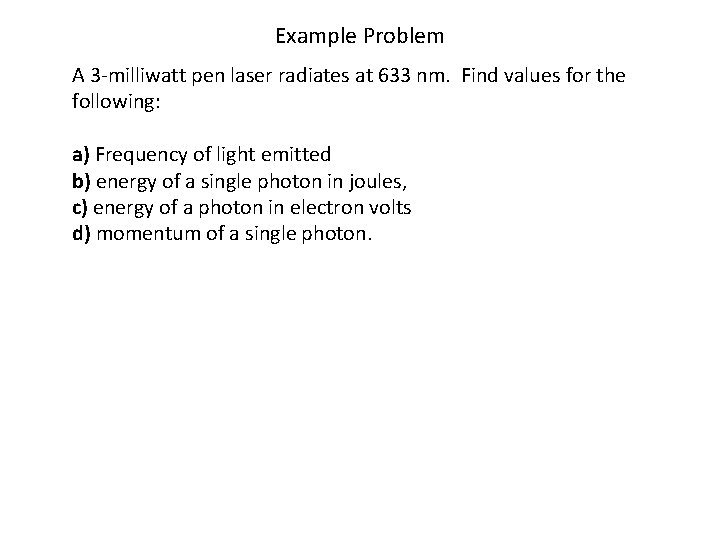

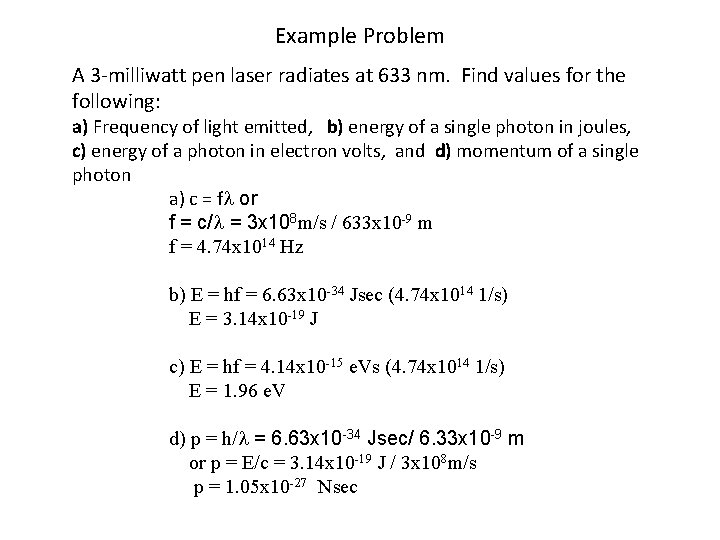

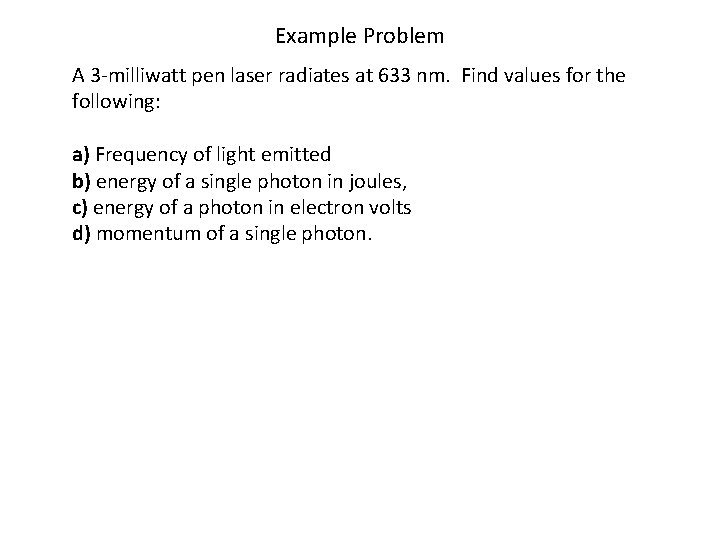

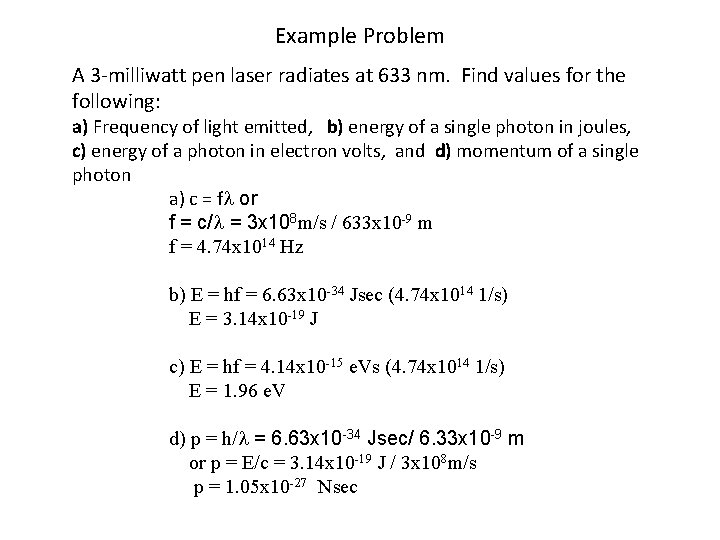

Example Problem A 3 -milliwatt pen laser radiates at 633 nm. Find values for the following: a) Frequency of light emitted b) energy of a single photon in joules, c) energy of a photon in electron volts d) momentum of a single photon.

Example Problem A 3 -milliwatt pen laser radiates at 633 nm. Find values for the following: a) Frequency of light emitted, b) energy of a single photon in joules, c) energy of a photon in electron volts, and d) momentum of a single photon a) c = f or f = c/ = 3 x 108 m/s / 633 x 10 -9 m f = 4. 74 x 1014 Hz b) E = hf = 6. 63 x 10 -34 Jsec (4. 74 x 1014 1/s) E = 3. 14 x 10 -19 J c) E = hf = 4. 14 x 10 -15 e. Vs (4. 74 x 1014 1/s) E = 1. 96 e. V d) p = h/ = 6. 63 x 10 -34 Jsec/ 6. 33 x 10 -9 m or p = E/c = 3. 14 x 10 -19 J / 3 x 108 m/s p = 1. 05 x 10 -27 Nsec

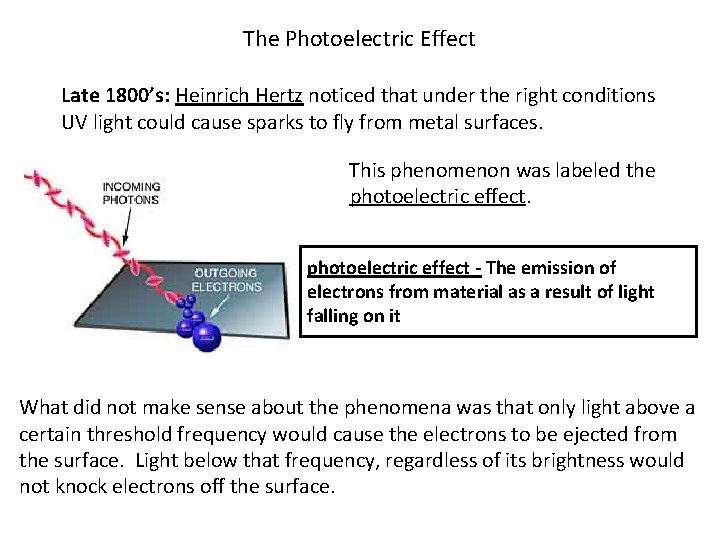

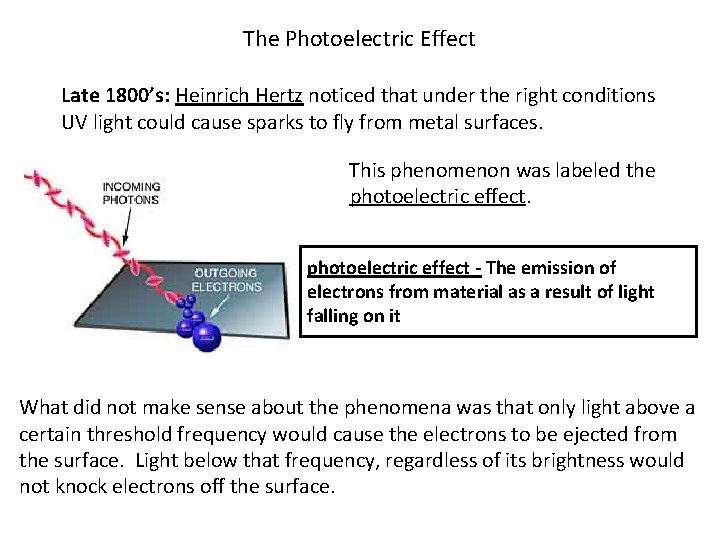

The Photoelectric Effect Late 1800’s: Heinrich Hertz noticed that under the right conditions UV light could cause sparks to fly from metal surfaces. This phenomenon was labeled the photoelectric effect - The emission of electrons from material as a result of light falling on it What did not make sense about the phenomena was that only light above a certain threshold frequency would cause the electrons to be ejected from the surface. Light below that frequency, regardless of its brightness would not knock electrons off the surface.

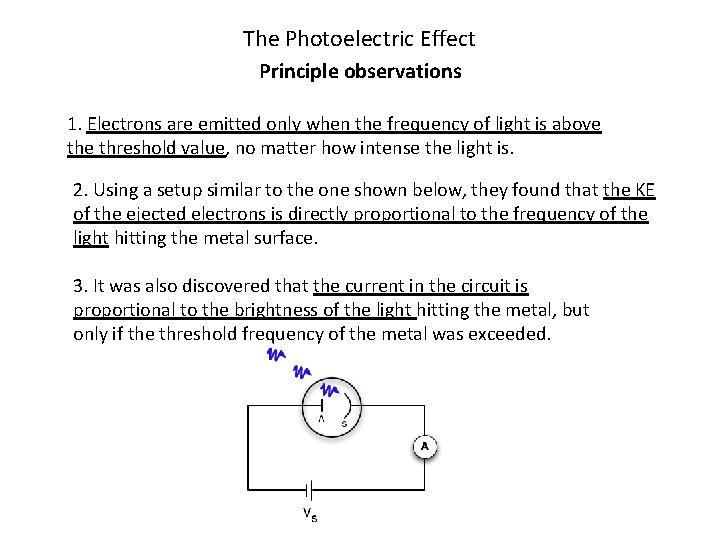

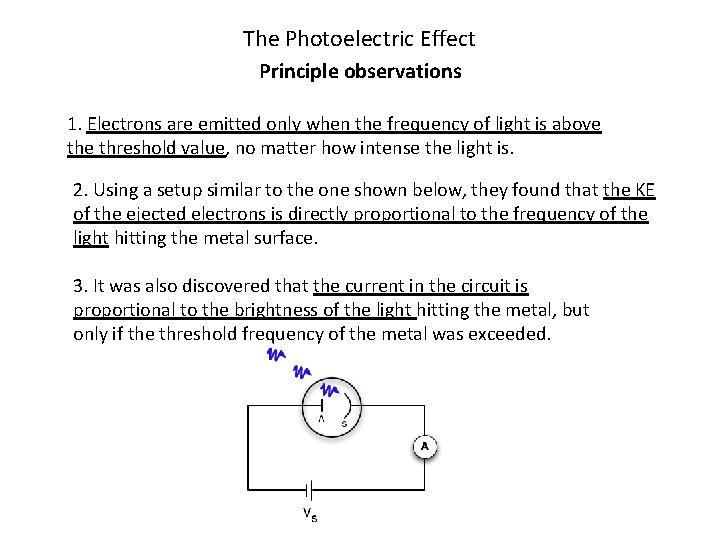

The Photoelectric Effect Principle observations 1. Electrons are emitted only when the frequency of light is above threshold value, no matter how intense the light is. 2. Using a setup similar to the one shown below, they found that the KE of the ejected electrons is directly proportional to the frequency of the light hitting the metal surface. 3. It was also discovered that the current in the circuit is proportional to the brightness of the light hitting the metal, but only if the threshold frequency of the metal was exceeded.

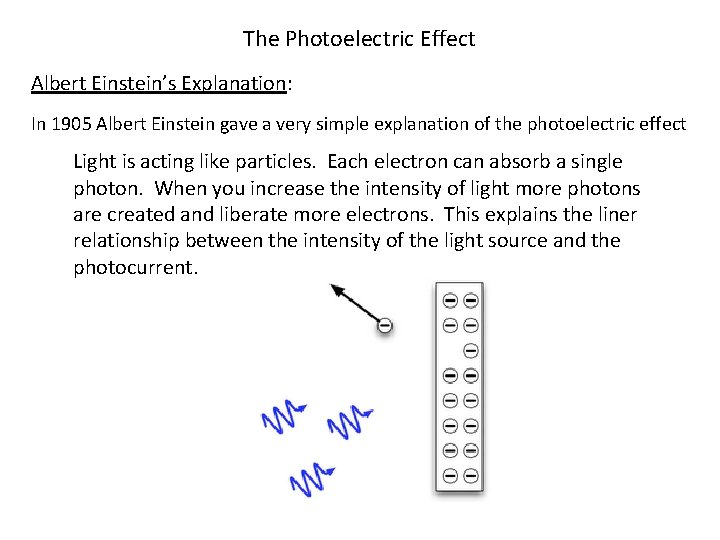

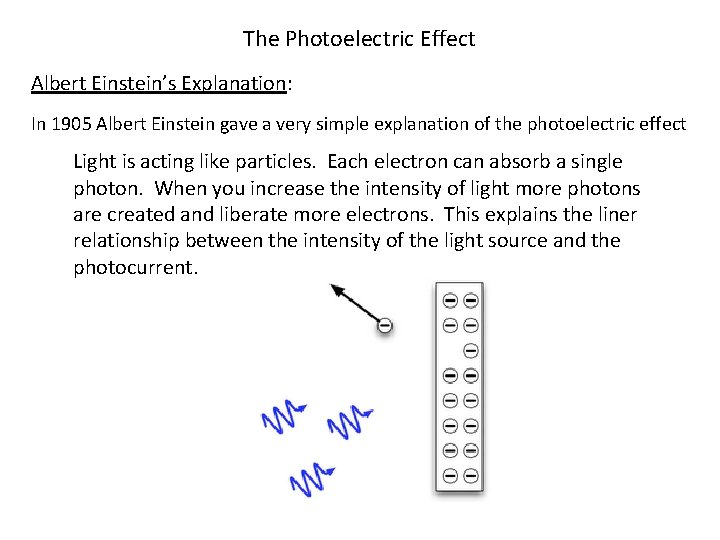

The Photoelectric Effect Albert Einstein’s Explanation: In 1905 Albert Einstein gave a very simple explanation of the photoelectric effect Light is acting like particles. Each electron can absorb a single photon. When you increase the intensity of light more photons are created and liberate more electrons. This explains the liner relationship between the intensity of the light source and the photocurrent.

The Photoelectric Effect Albert Einstein’s Explanation:

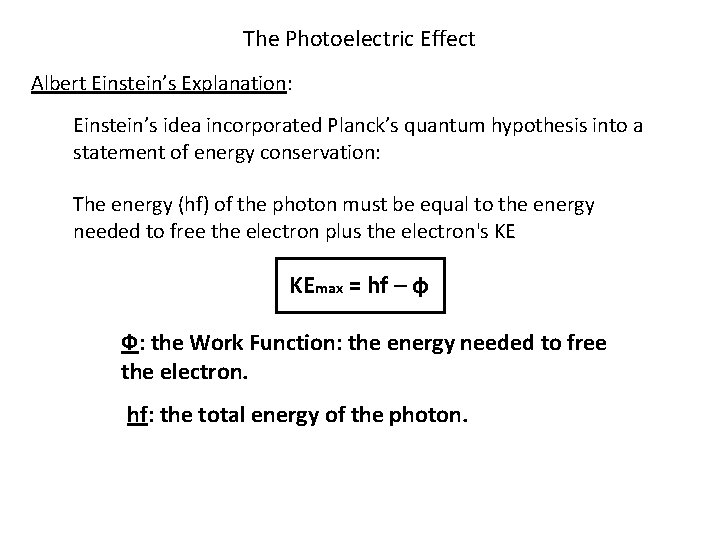

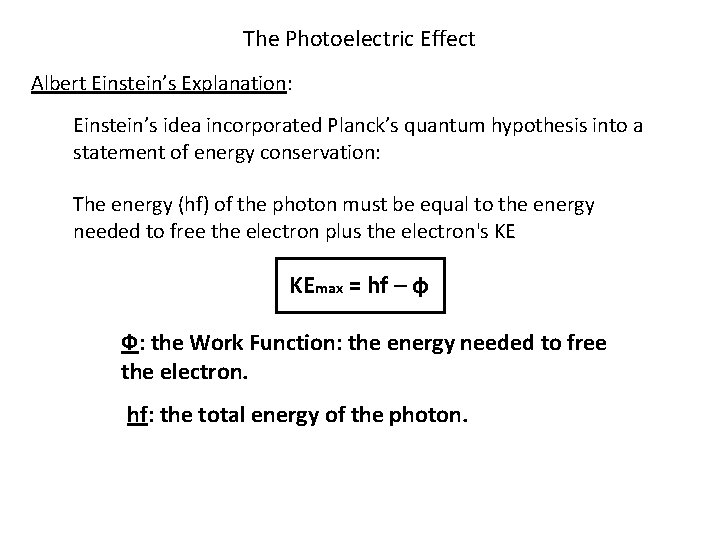

The Photoelectric Effect Albert Einstein’s Explanation: Einstein’s idea incorporated Planck’s quantum hypothesis into a statement of energy conservation: The energy (hf) of the photon must be equal to the energy needed to free the electron plus the electron's KE KEmax = hf – ф Ф: the Work Function: the energy needed to free the electron. hf: the total energy of the photon.

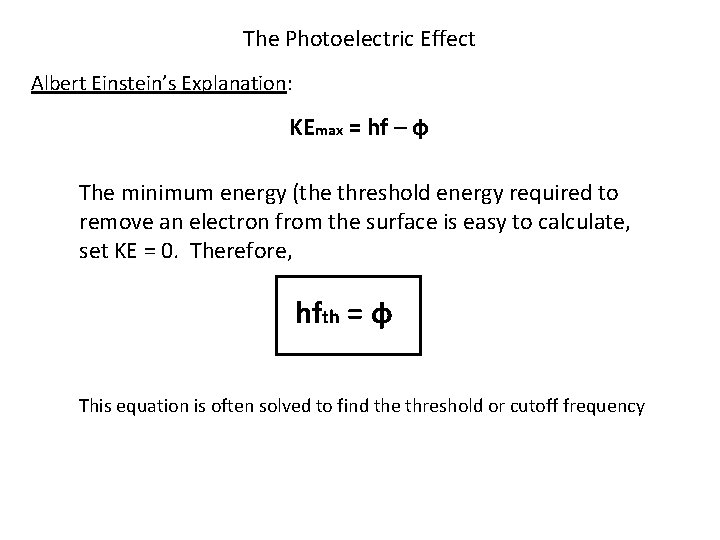

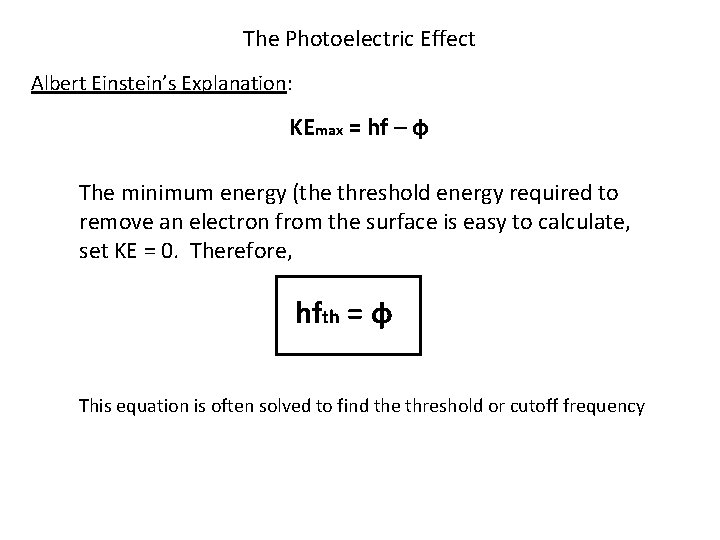

The Photoelectric Effect Albert Einstein’s Explanation: KEmax = hf – ф The minimum energy (the threshold energy required to remove an electron from the surface is easy to calculate, set KE = 0. Therefore, hfth = ф This equation is often solved to find the threshold or cutoff frequency

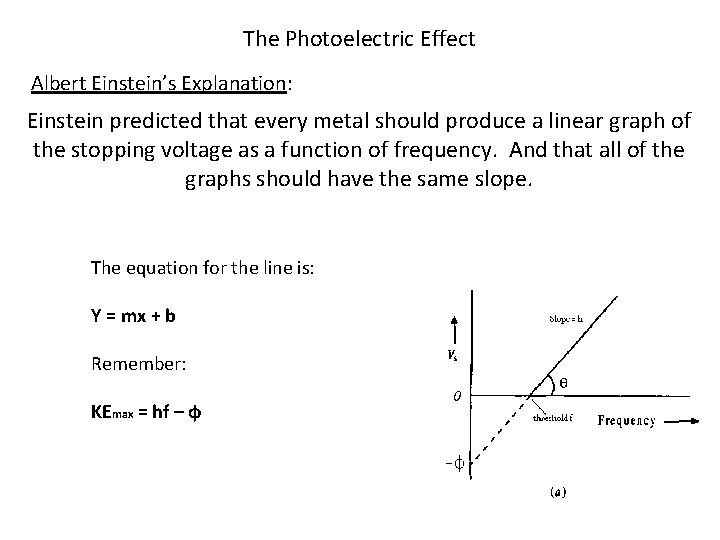

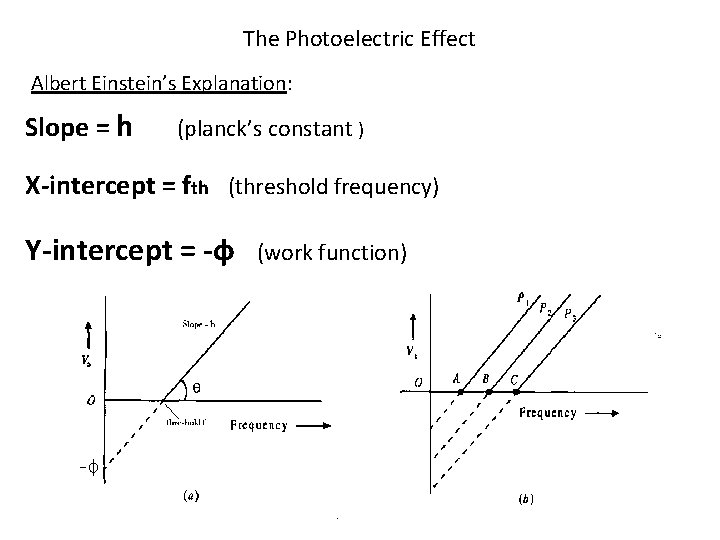

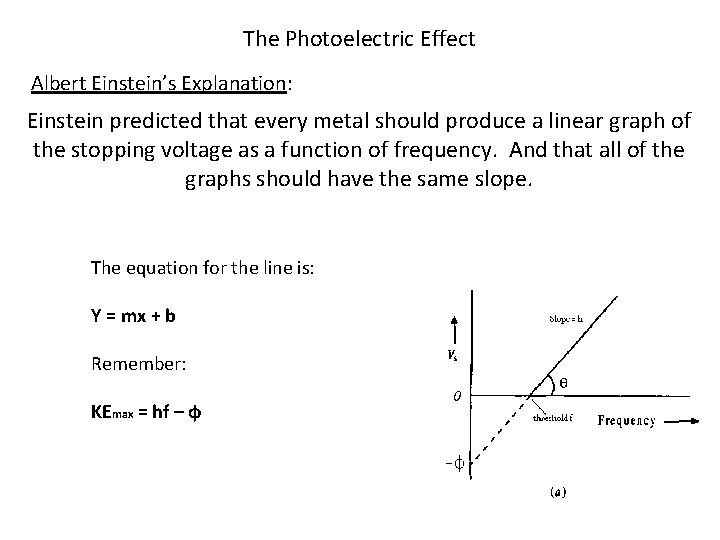

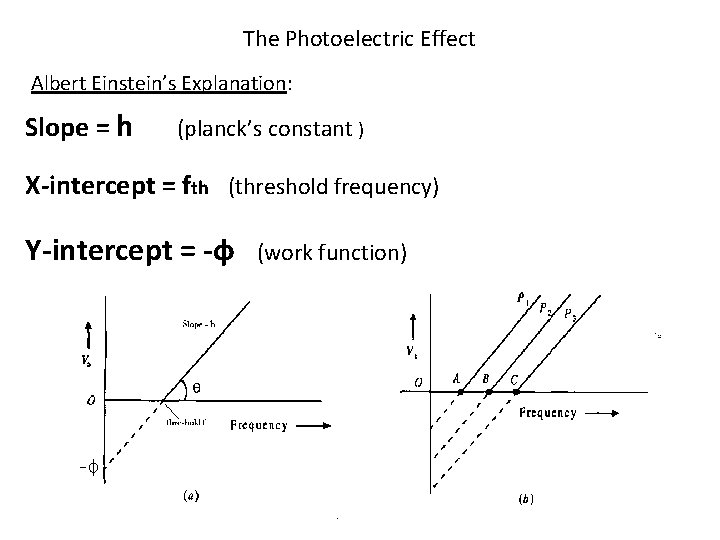

The Photoelectric Effect Albert Einstein’s Explanation: Einstein predicted that every metal should produce a linear graph of the stopping voltage as a function of frequency. And that all of the graphs should have the same slope. The equation for the line is: Y = mx + b Remember: KEmax = hf – ф

The Photoelectric Effect Albert Einstein’s Explanation: Slope = h (planck’s constant ) X-intercept = fth (threshold frequency) Y-intercept = -ф (work function)

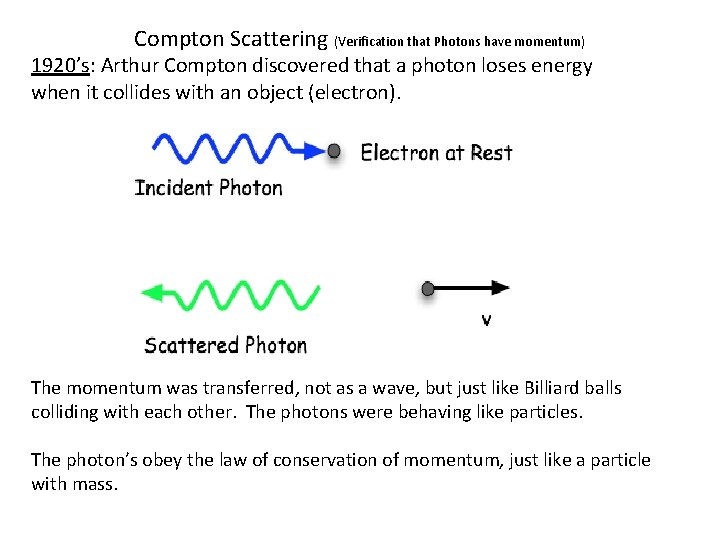

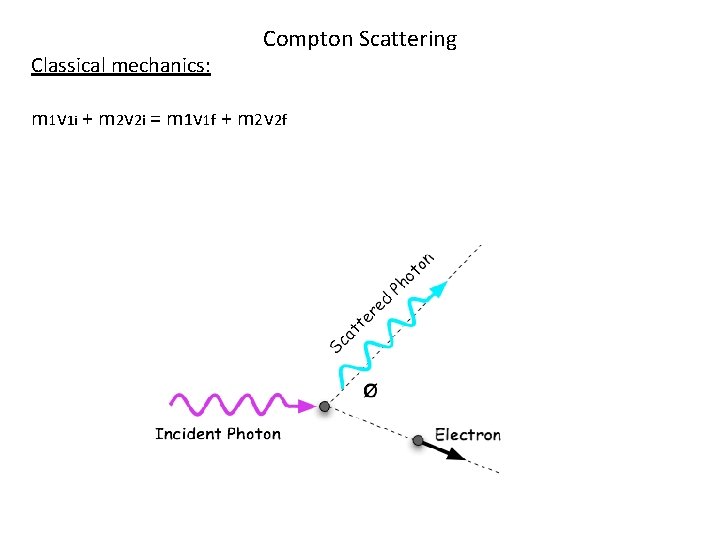

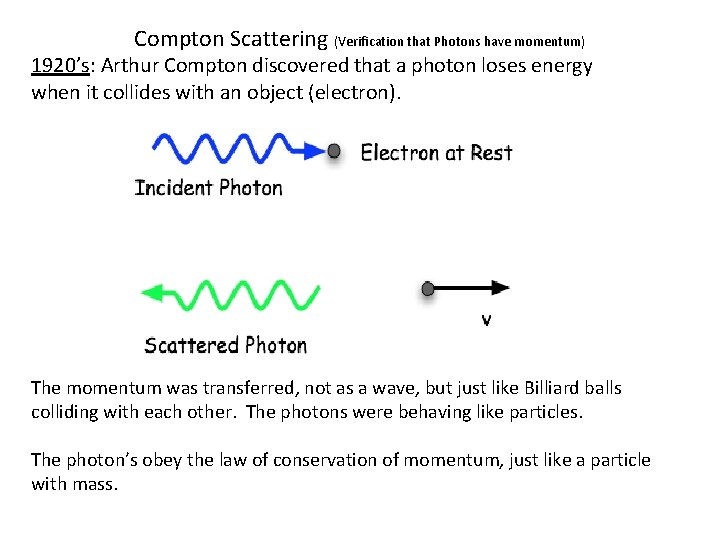

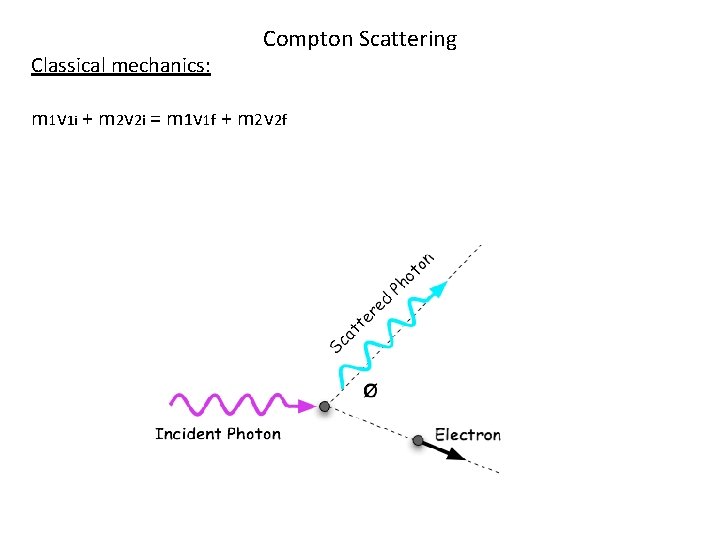

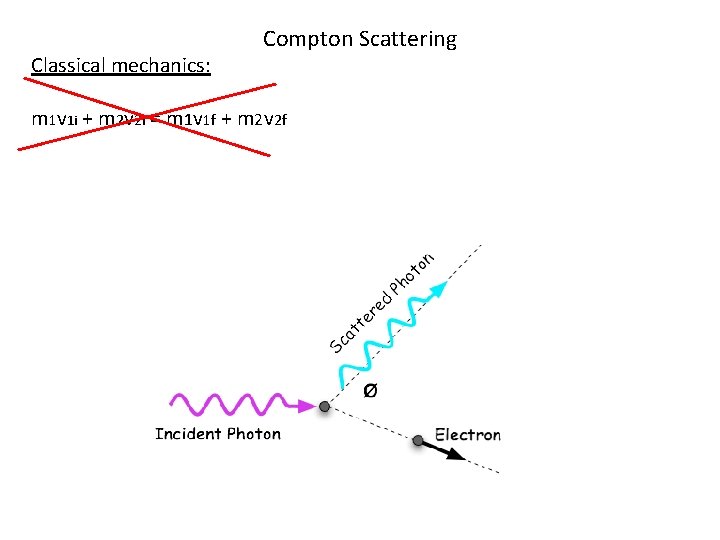

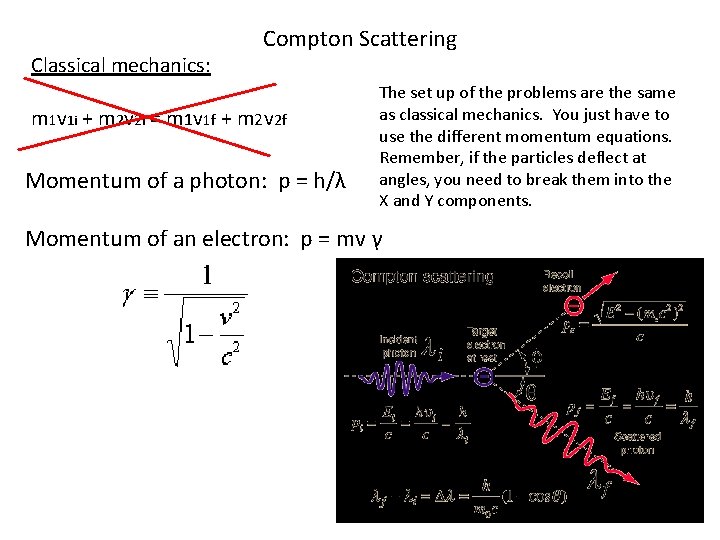

Compton Scattering (Verification that Photons have momentum) 1920’s: Arthur Compton discovered that a photon loses energy when it collides with an object (electron). The momentum was transferred, not as a wave, but just like Billiard balls colliding with each other. The photons were behaving like particles. The photon’s obey the law of conservation of momentum, just like a particle with mass.

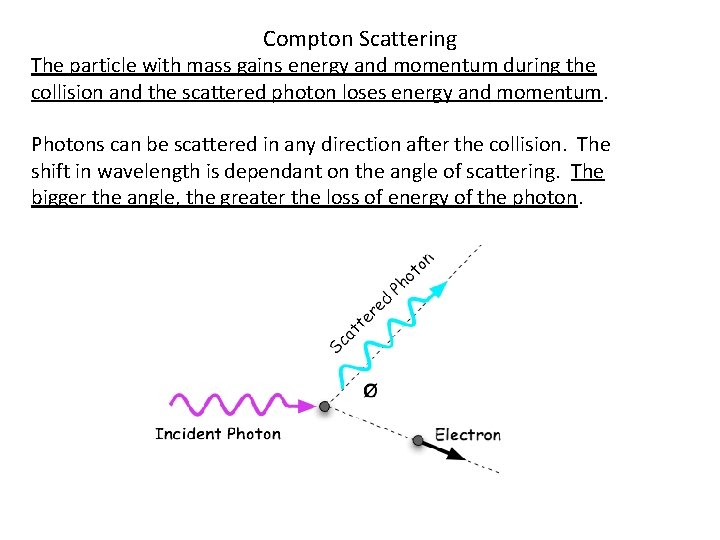

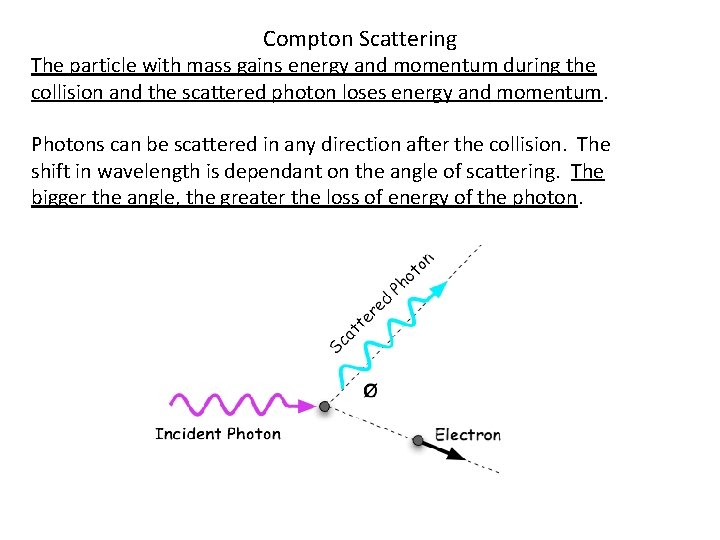

Compton Scattering The particle with mass gains energy and momentum during the collision and the scattered photon loses energy and momentum. Photons can be scattered in any direction after the collision. The shift in wavelength is dependant on the angle of scattering. The bigger the angle, the greater the loss of energy of the photon.

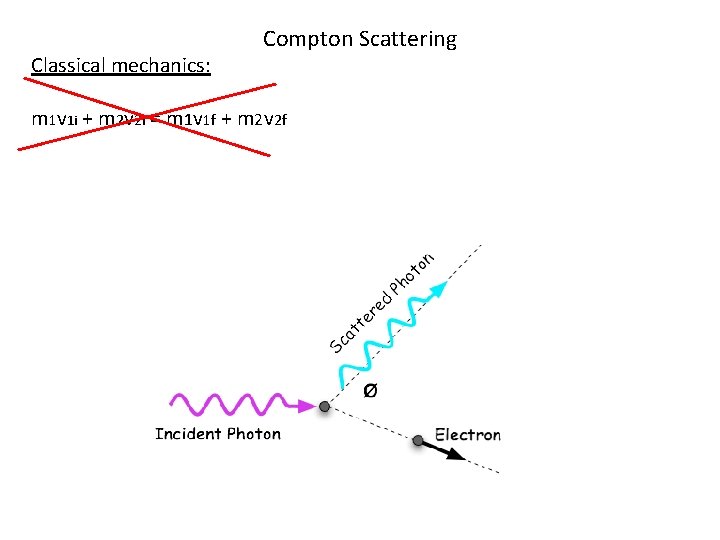

Classical mechanics: Compton Scattering m 1 v 1 i + m 2 v 2 i = m 1 v 1 f + m 2 v 2 f

Classical mechanics: Compton Scattering m 1 v 1 i + m 2 v 2 i = m 1 v 1 f + m 2 v 2 f

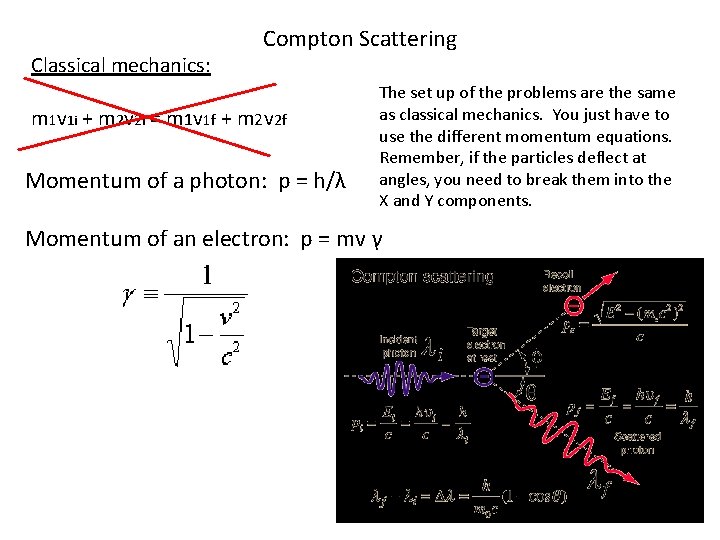

Classical mechanics: Compton Scattering m 1 v 1 i + m 2 v 2 i = m 1 v 1 f + m 2 v 2 f Momentum of a photon: p = h/λ The set up of the problems are the same as classical mechanics. You just have to use the different momentum equations. Remember, if the particles deflect at angles, you need to break them into the X and Y components. Momentum of an electron: p = mv γ

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom So far we showed that many aspects of light can only be predicted if we assume light is a particle. Yet it also acts as a wave (diffraction/interference). This is called the Wave/Particle duality of light. It is both a wave and a particle – or something else that we can only measure as a wave or particle. If light can behave as a particle, can a particle behave as a wave? Yes The atom can only be fully explained if we assume it is a wave… Brief history of the atom

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom J. J. Thomson – Plum Pudding Model: Plum Pudding does not contain plums!!! In the 17 th century, “plum” referred to raisins and other dried fruits.

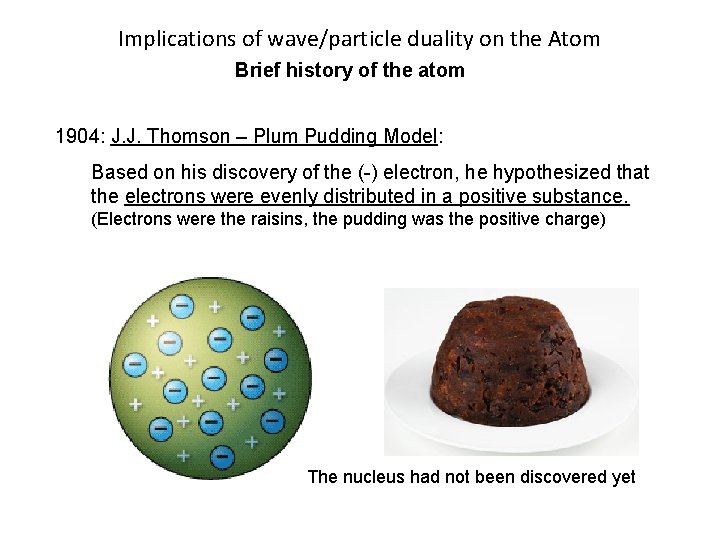

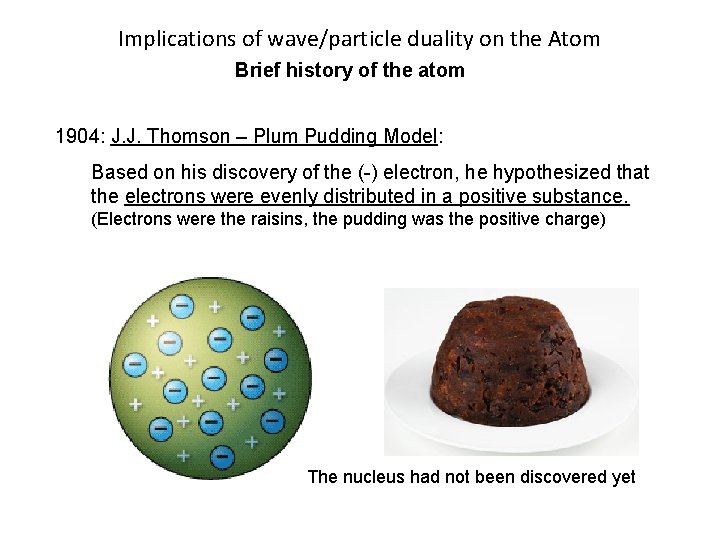

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom 1904: J. J. Thomson – Plum Pudding Model: Based on his discovery of the (-) electron, he hypothesized that the electrons were evenly distributed in a positive substance. (Electrons were the raisins, the pudding was the positive charge) The nucleus had not been discovered yet

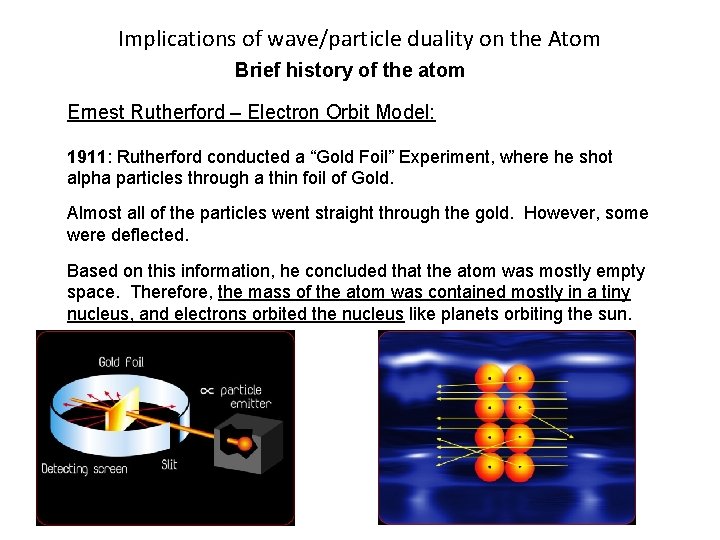

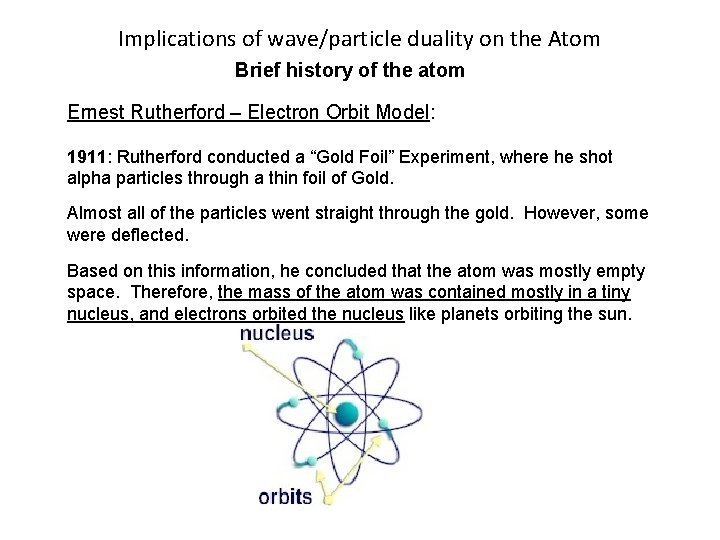

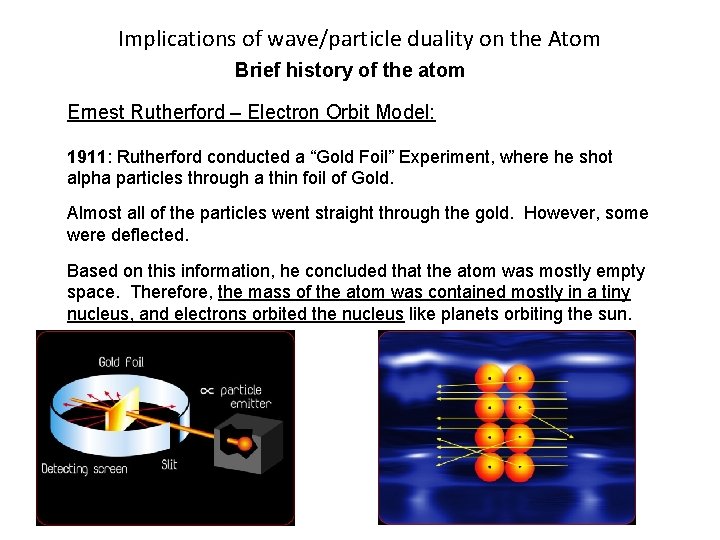

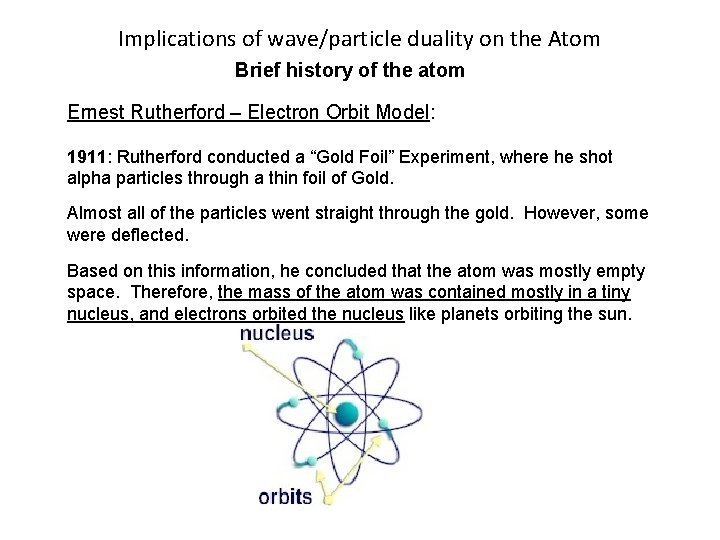

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Ernest Rutherford – Electron Orbit Model: 1911: Rutherford conducted a “Gold Foil” Experiment, where he shot alpha particles through a thin foil of Gold. Almost all of the particles went straight through the gold. However, some were deflected. Based on this information, he concluded that the atom was mostly empty space. Therefore, the mass of the atom was contained mostly in a tiny nucleus, and electrons orbited the nucleus like planets orbiting the sun.

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Ernest Rutherford – Electron Orbit Model:

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Ernest Rutherford – Electron Orbit Model: 1911: Rutherford conducted a “Gold Foil” Experiment, where he shot alpha particles through a thin foil of Gold. Almost all of the particles went straight through the gold. However, some were deflected. Based on this information, he concluded that the atom was mostly empty space. Therefore, the mass of the atom was contained mostly in a tiny nucleus, and electrons orbited the nucleus like planets orbiting the sun.

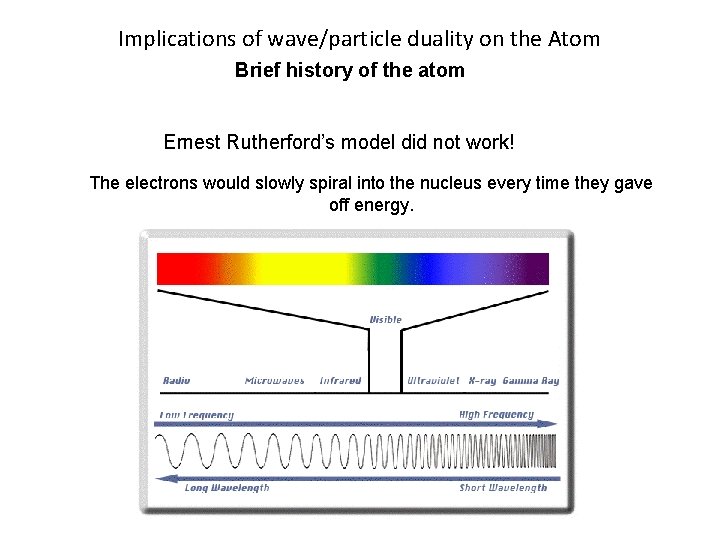

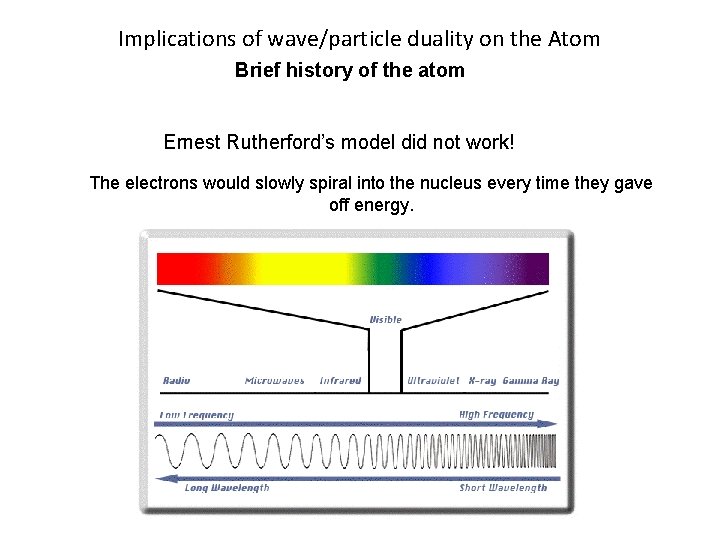

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Ernest Rutherford’s model did not work! The electrons would slowly spiral into the nucleus every time they gave off energy.

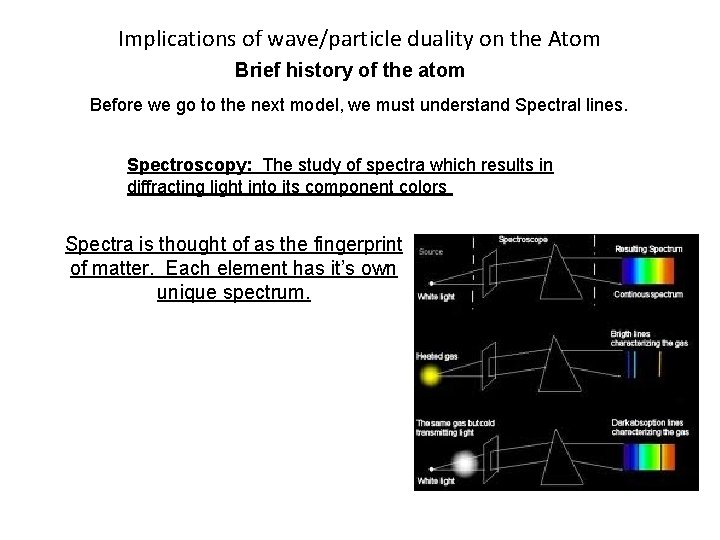

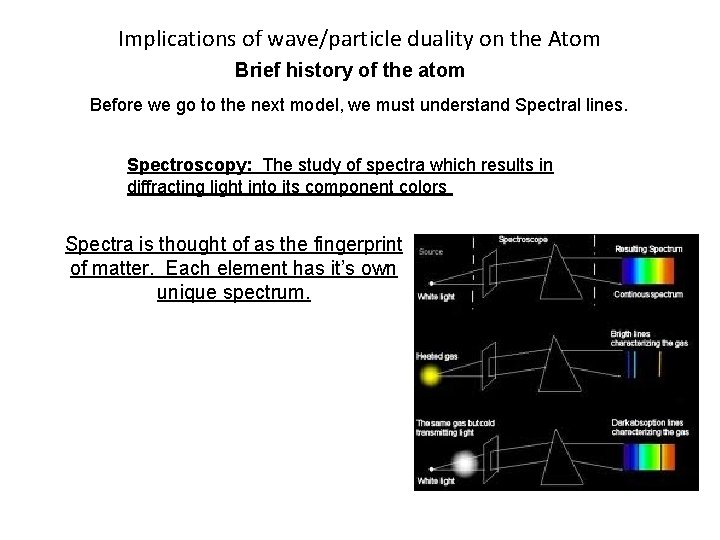

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Before we go to the next model, we must understand Spectral lines. Spectroscopy: The study of spectra which results in diffracting light into its component colors Spectra is thought of as the fingerprint of matter. Each element has it’s own unique spectrum.

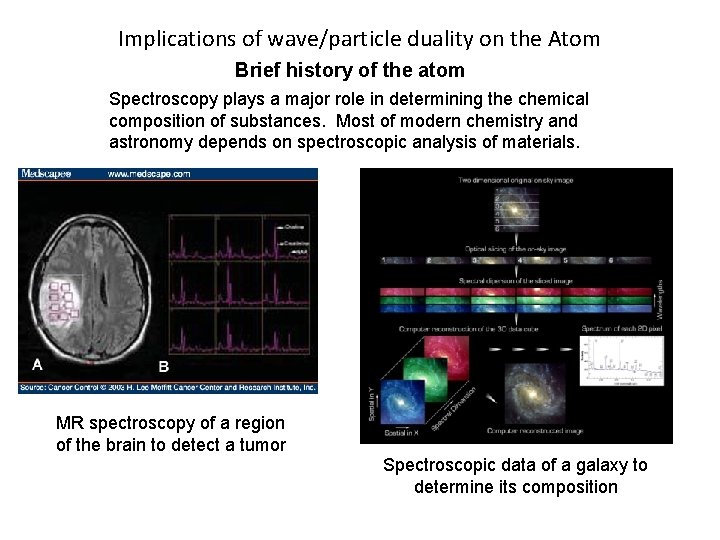

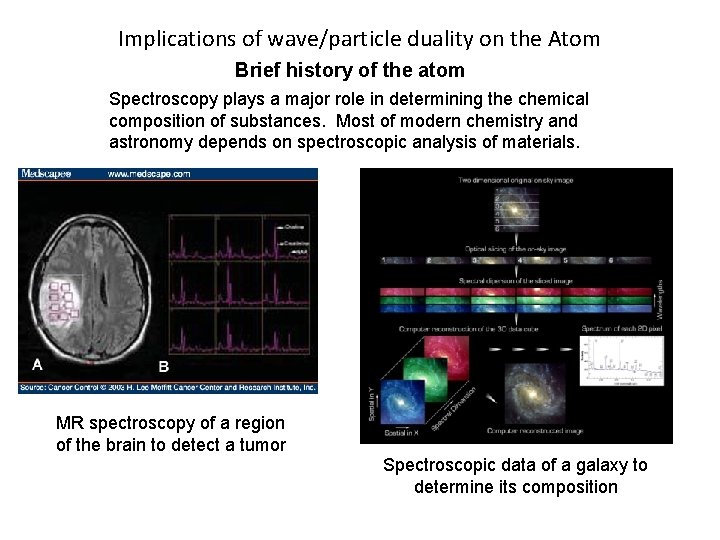

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Spectroscopy plays a major role in determining the chemical composition of substances. Most of modern chemistry and astronomy depends on spectroscopic analysis of materials. MR spectroscopy of a region of the brain to detect a tumor Spectroscopic data of a galaxy to determine its composition

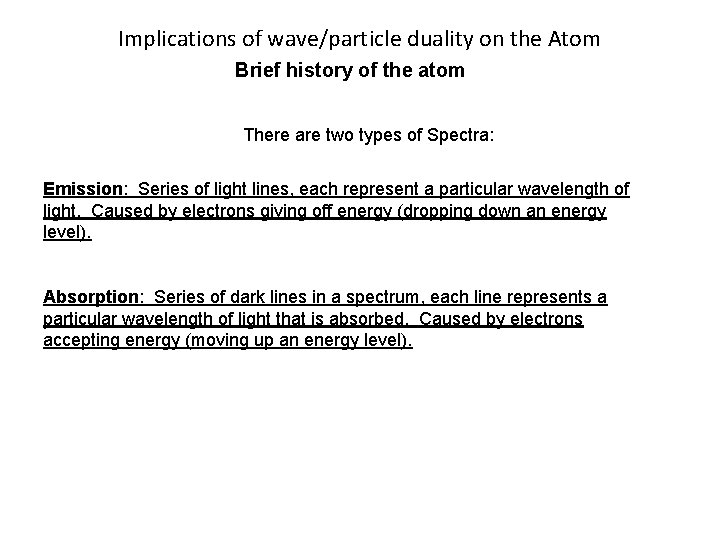

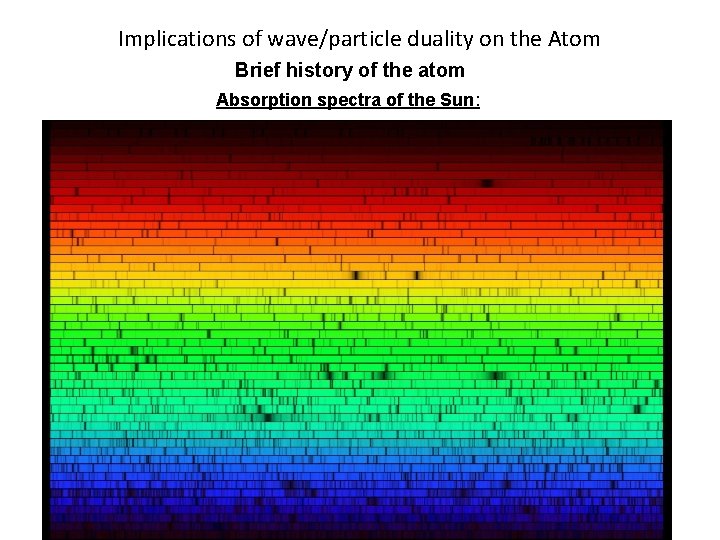

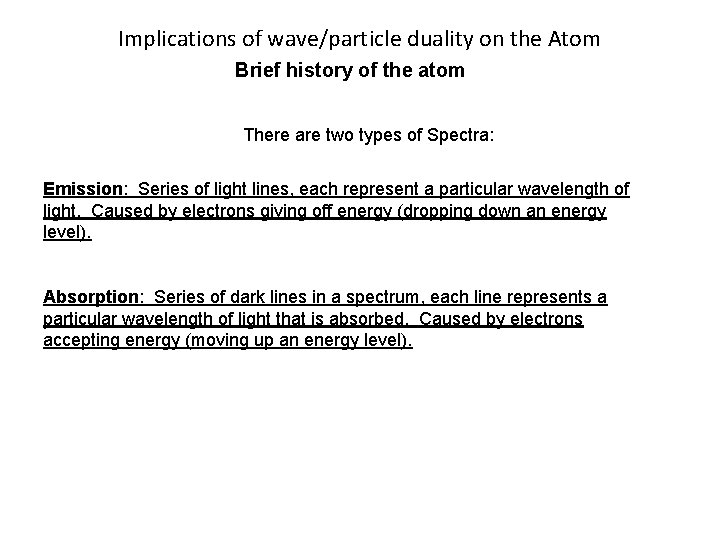

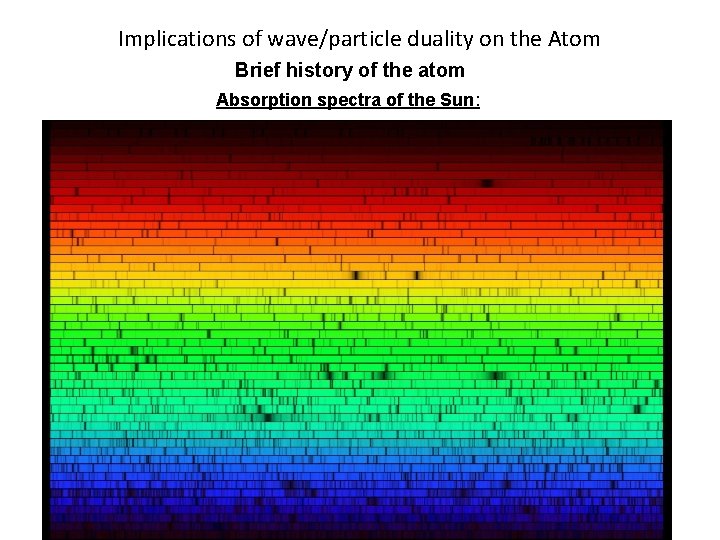

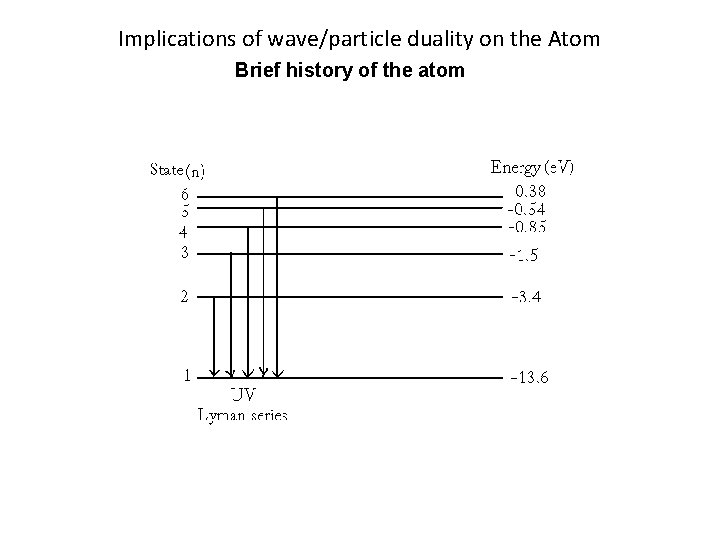

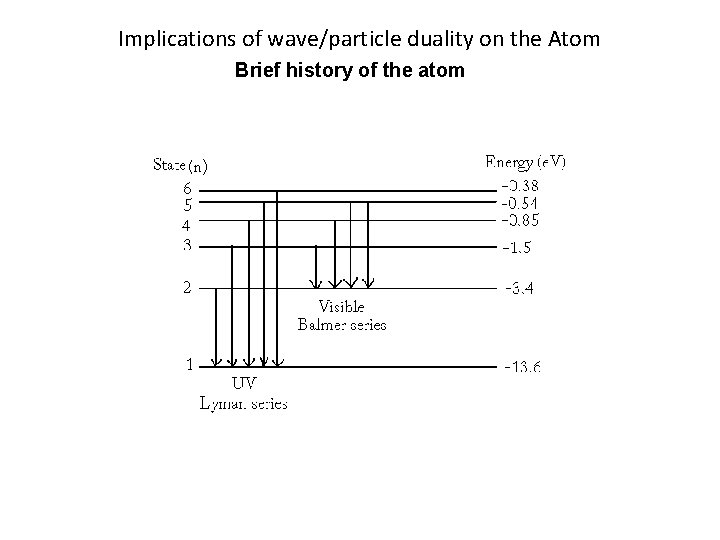

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom There are two types of Spectra: Emission: Series of light lines, each represent a particular wavelength of light. Caused by electrons giving off energy (dropping down an energy level). Absorption: Series of dark lines in a spectrum, each line represents a particular wavelength of light that is absorbed. Caused by electrons accepting energy (moving up an energy level).

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Absorption spectra of the Sun:

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Emission and Absorption spectrum

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Spectroscopy: Physicists could use spectroscopy to determine compositions, temperatures, velocities, etc… of many different object. Charts were made of the spectra of each element. However, no one could determine the exact cause of the spectral lines. According to Rutherford’s model, electrons that gave off continuous energy would spiral into the nucleus of the atom. Another model of the atom had to be made.

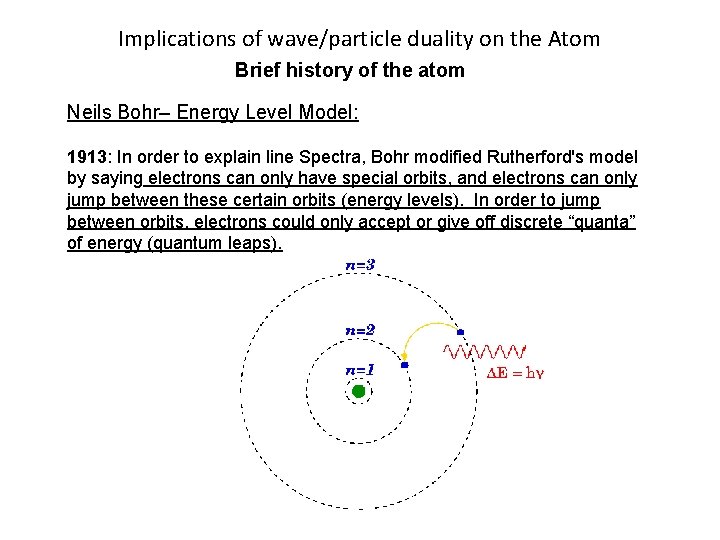

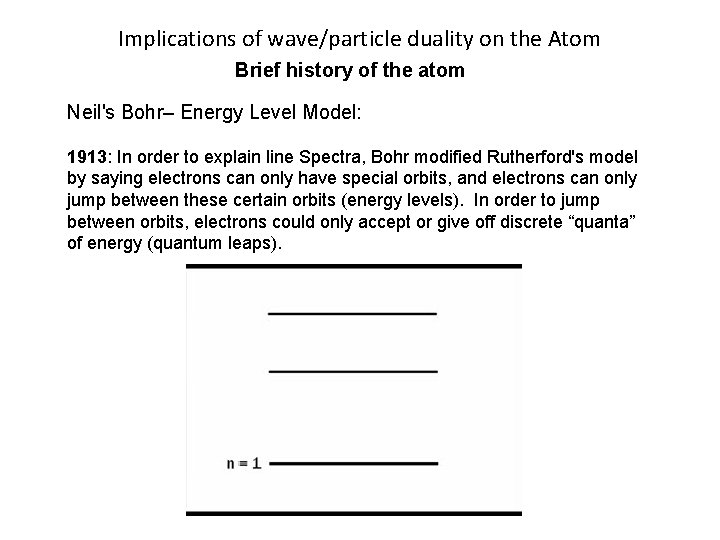

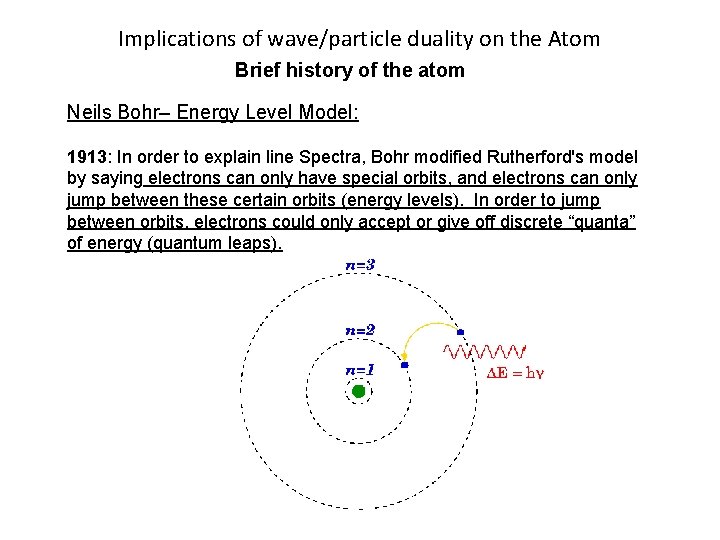

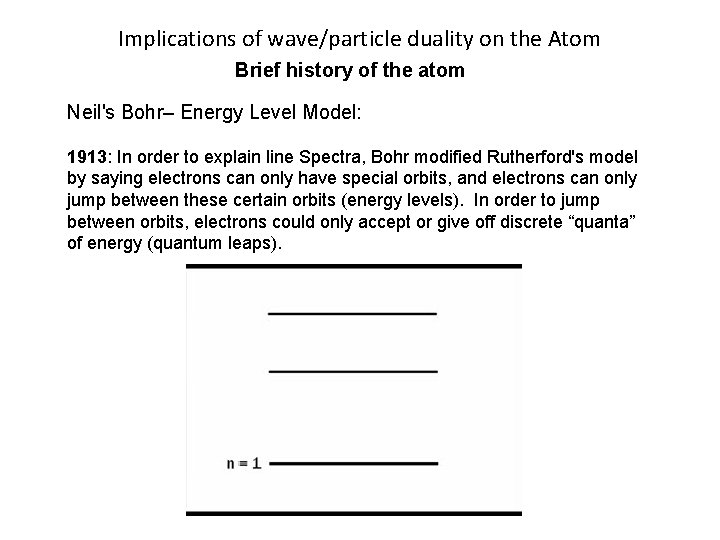

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Neils Bohr– Energy Level Model: 1913: In order to explain line Spectra, Bohr modified Rutherford's model by saying electrons can only have special orbits, and electrons can only jump between these certain orbits (energy levels). In order to jump between orbits, electrons could only accept or give off discrete “quanta” of energy (quantum leaps).

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Neil's Bohr– Energy Level Model: 1913: In order to explain line Spectra, Bohr modified Rutherford's model by saying electrons can only have special orbits, and electrons can only jump between these certain orbits (energy levels). In order to jump between orbits, electrons could only accept or give off discrete “quanta” of energy (quantum leaps).

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom

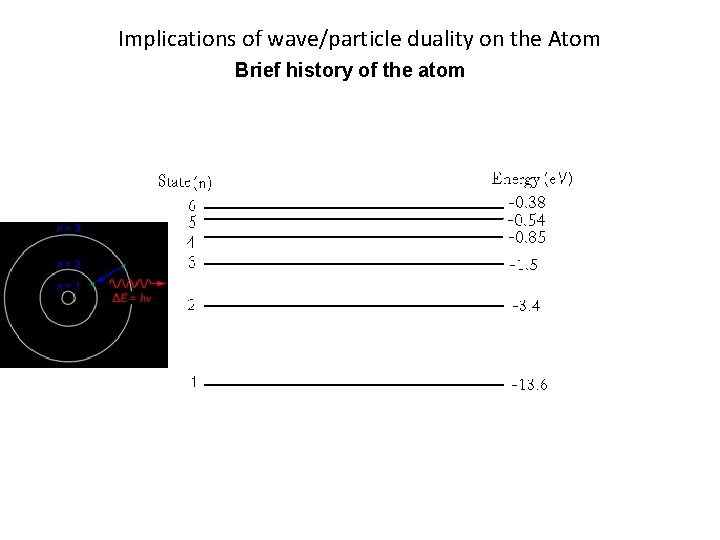

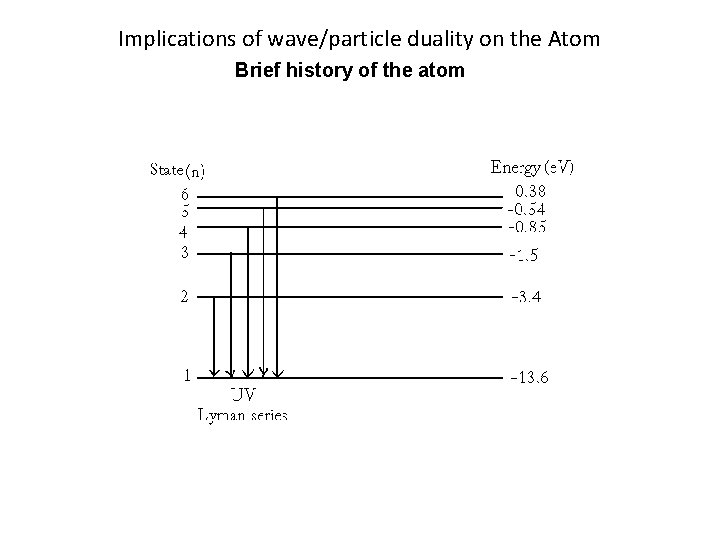

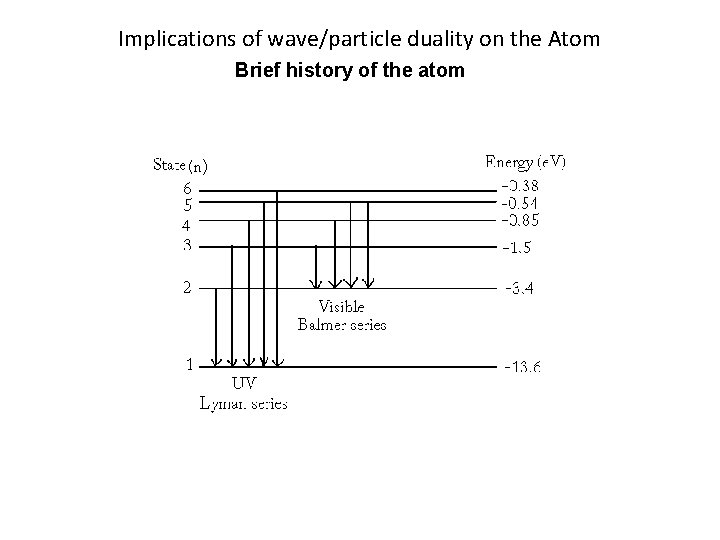

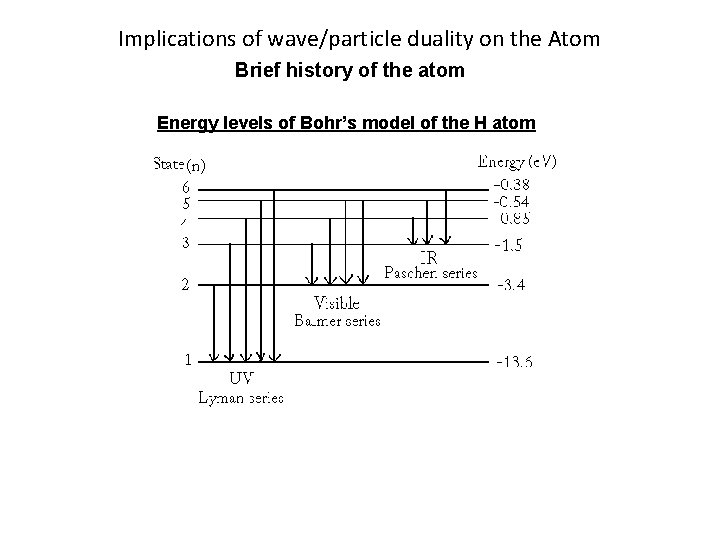

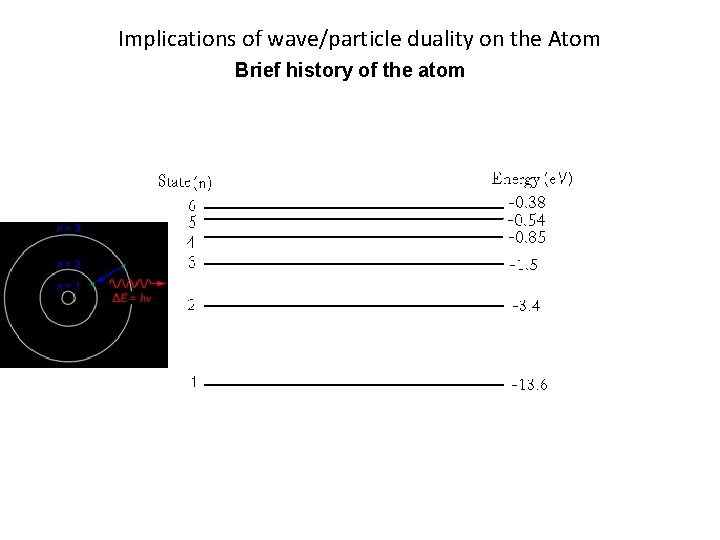

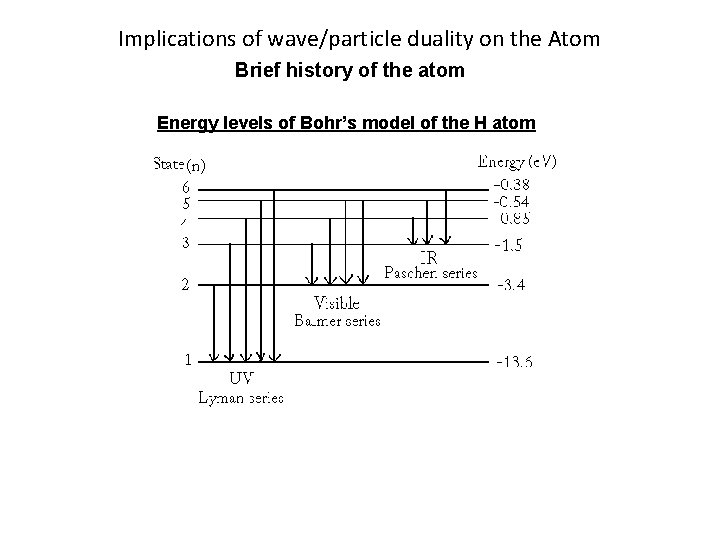

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Energy levels of Bohr’s model of the H atom

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Energy levels of Bohr’s model of the H atom Energy => hf = Ei - Ef

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Energy levels of Bohr’s model of the H atom When using this equation E is the energy from Bohr’s Energy level diagram. Make sure E is converted into Joules

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Problem with Bohr’s model:

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Problem with Bohr’s model: It only works for Hydrogen, or Ionized Helium (Helium with only 1 electron) His model does not work for any atom with more than 1 electron

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Problem with Bohr’s model: It only works for Hydrogen, or Ionized Helium (Helium with only 1 electron) His model does not work for any atom with more than 1 electron So why is his model important? He has the correct concept (Energy levels). This led the way into a more correct model of the Atom.

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Energy levels of the H atom

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Problem with Bohr’s model: It only works for Hydrogen, or Ionized Helium (Helium with only 1 electron) His model does not work for any atom with more than 1 electron So why is his model important? He has the correct concept (Energy levels). This led the way into a more correct model of the Atom.

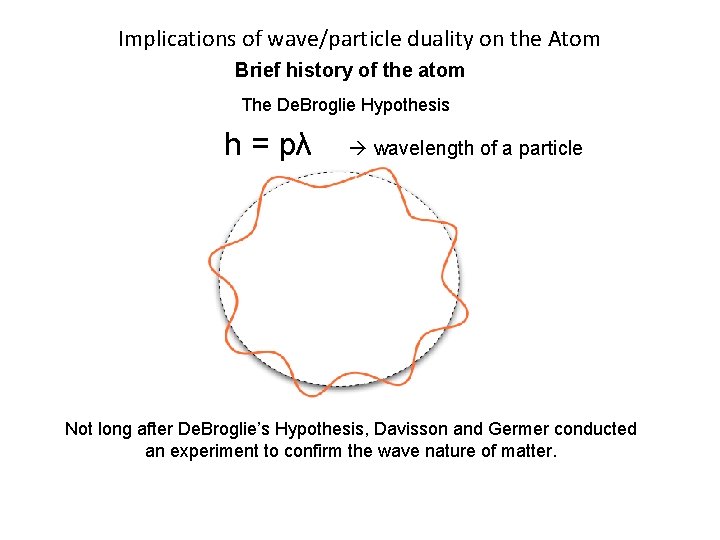

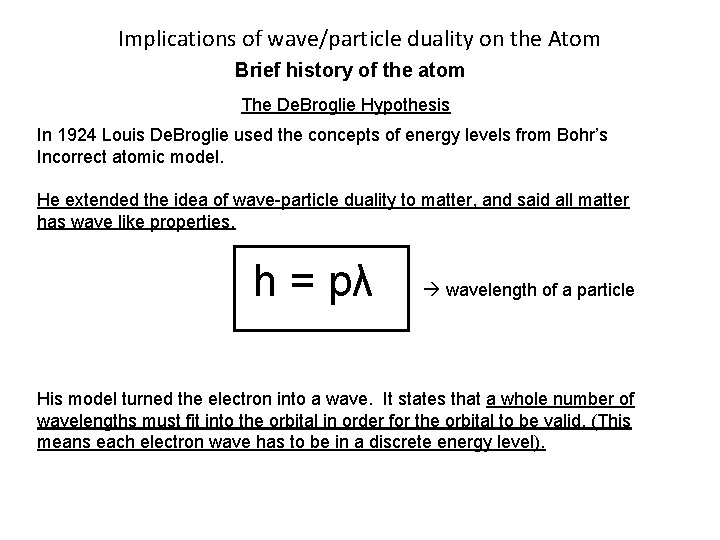

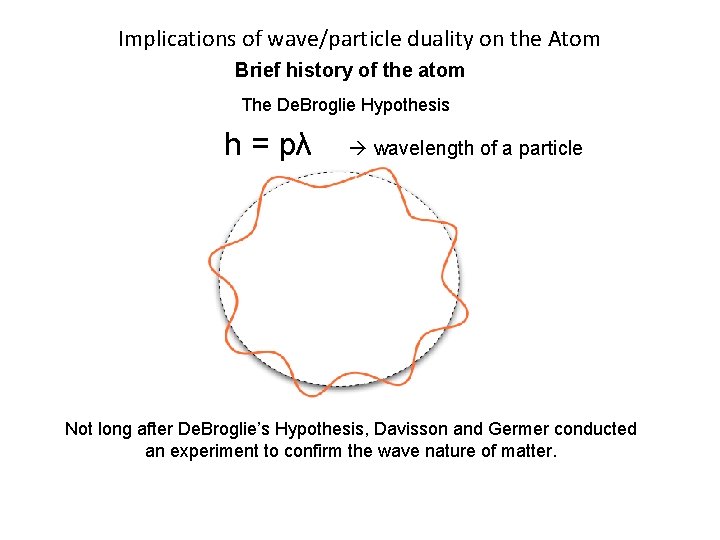

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom The De. Broglie Hypothesis In 1924 Louis De. Broglie used the concepts of energy levels from Bohr’s Incorrect atomic model. He extended the idea of wave-particle duality to matter, and said all matter has wave like properties. h = pλ wavelength of a particle His model turned the electron into a wave. It states that a whole number of wavelengths must fit into the orbital in order for the orbital to be valid. (This means each electron wave has to be in a discrete energy level).

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom The De. Broglie Hypothesis h = pλ wavelength of a particle Not long after De. Broglie’s Hypothesis, Davisson and Germer conducted an experiment to confirm the wave nature of matter.

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom The De. Broglie Hypothesis h = pλ wavelength of a particle If all matter has a wavelength, why don’t humans diffract when they walk through a doorway?

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom The De. Broglie Hypothesis Not long after De. Broglie’s Hypothesis, Davisson and Germer conducted an experiment to confirm the wave nature of matter.

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Heisenberg added to the model by saying since the electron is the entire standing wave, we cannot pinpoint the electrons exact position. It occupies the entire wave. (This is “Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle”)

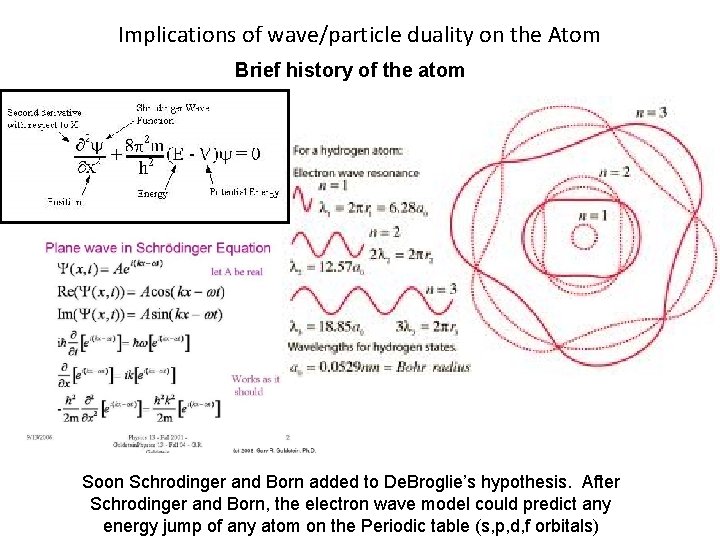

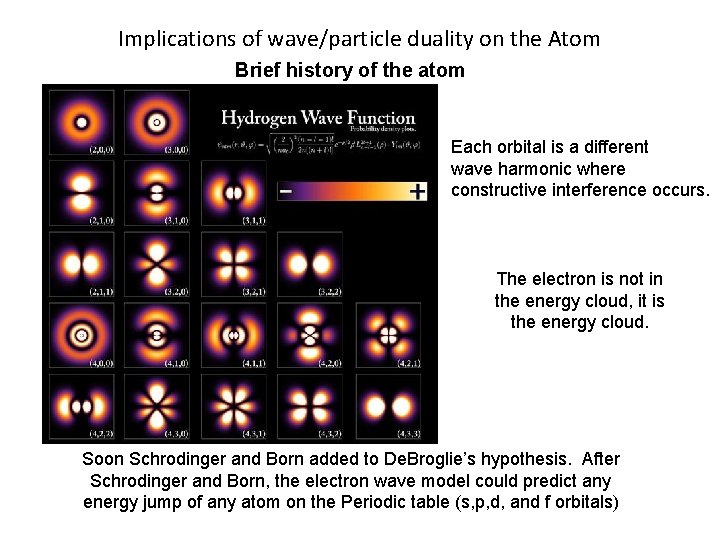

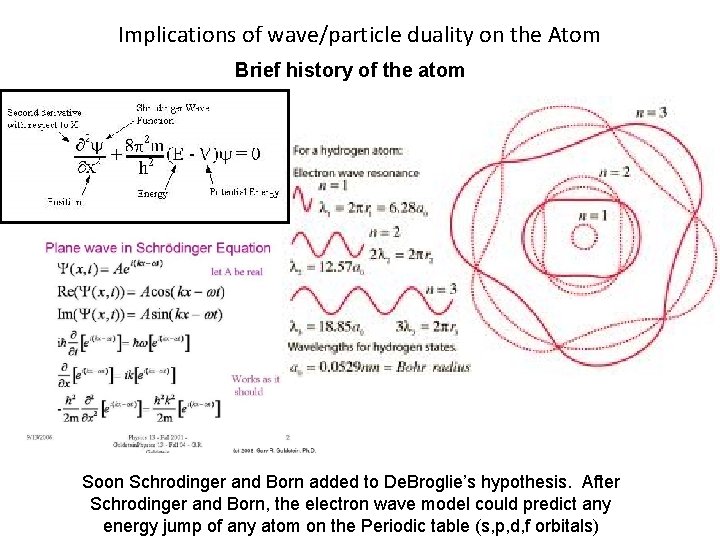

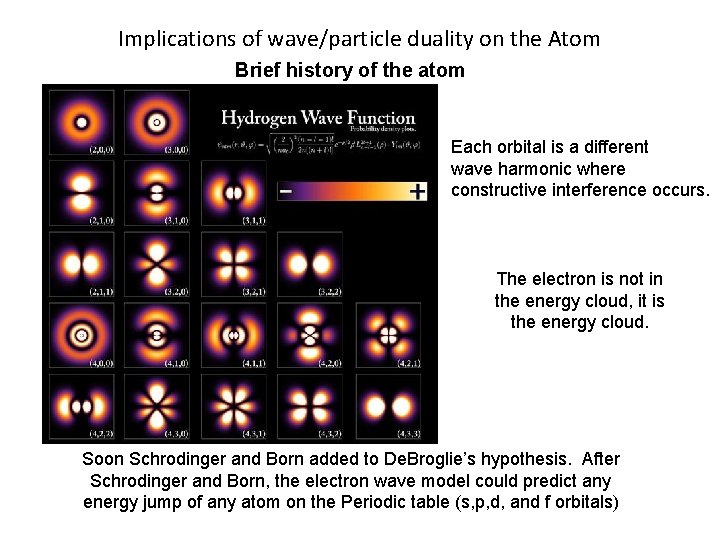

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Soon Schrodinger and Born added to De. Broglie’s hypothesis. After Schrodinger and Born, the electron wave model could predict any energy jump of any atom on the Periodic table (s, p, d, f orbitals)

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Physicists modern view of atoms

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom Each orbital is a different wave harmonic where constructive interference occurs. The electron is not in the energy cloud, it is the energy cloud. Soon Schrodinger and Born added to De. Broglie’s hypothesis. After Schrodinger and Born, the electron wave model could predict any energy jump of any atom on the Periodic table (s, p, d, and f orbitals)

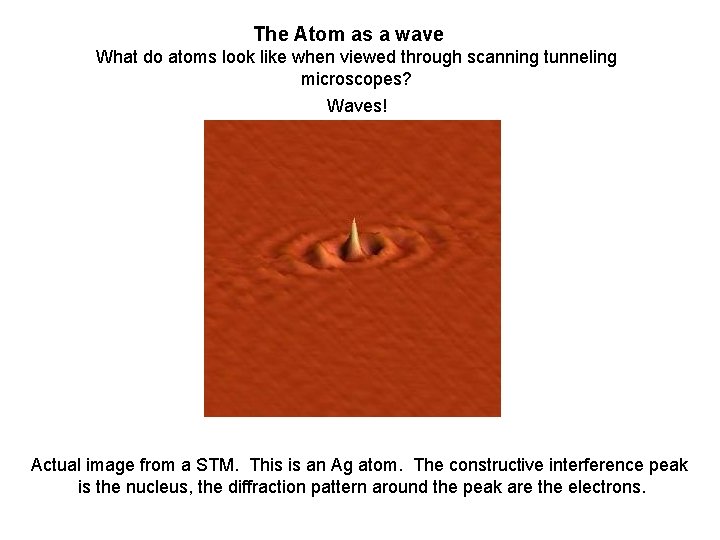

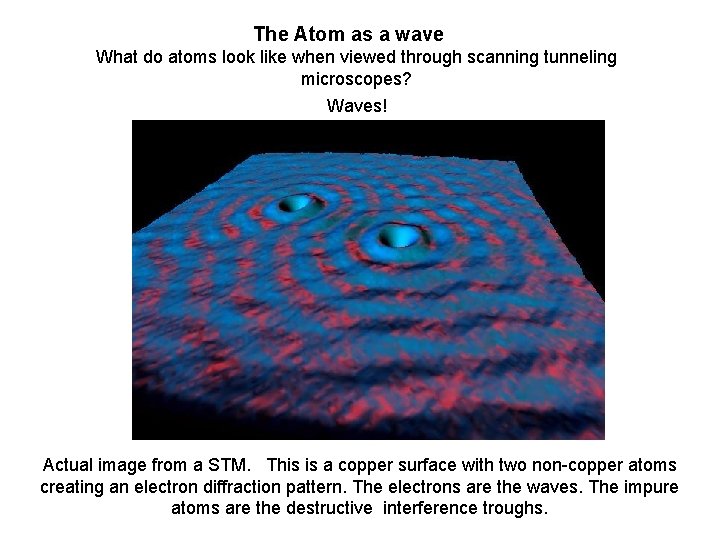

The Atom as a wave What do atoms look like when viewed through scanning tunneling microscopes?

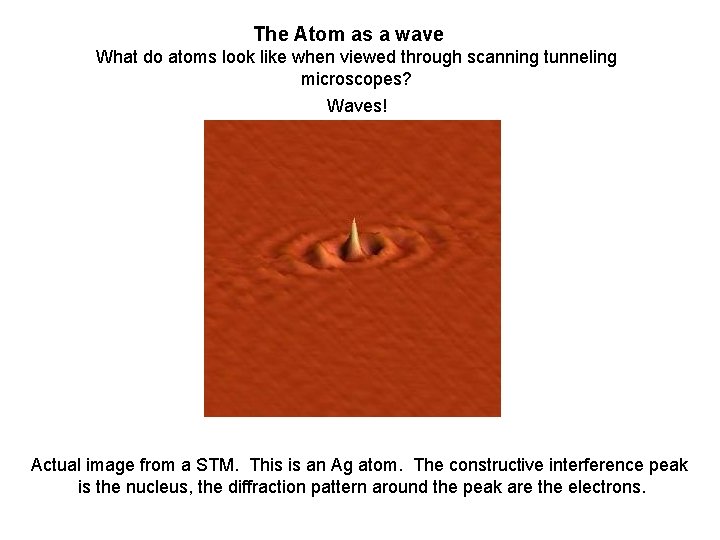

The Atom as a wave What do atoms look like when viewed through scanning tunneling microscopes? Waves! Actual image from a STM. This is an Ag atom. The constructive interference peak is the nucleus, the diffraction pattern around the peak are the electrons.

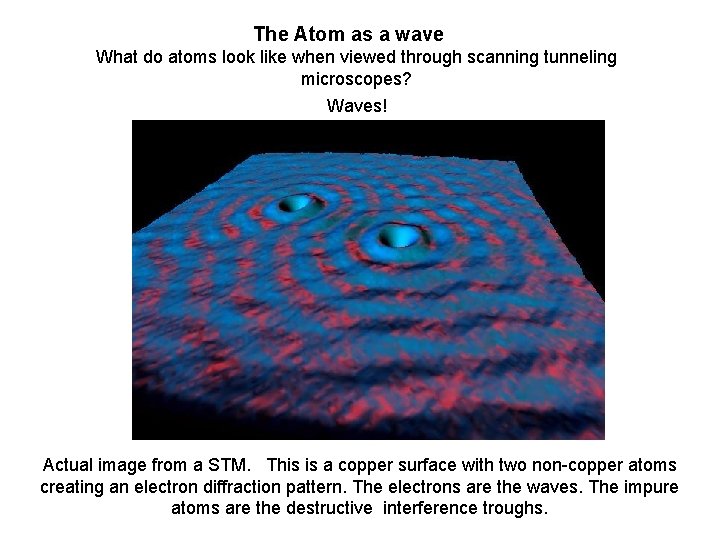

The Atom as a wave What do atoms look like when viewed through scanning tunneling microscopes? Waves! Actual image from a STM. This is a copper surface with two non-copper atoms creating an electron diffraction pattern. The electrons are the waves. The impure atoms are the destructive interference troughs.

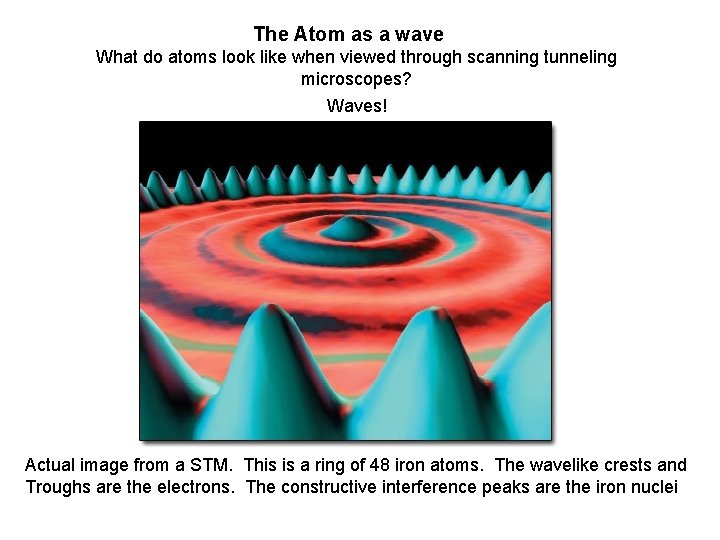

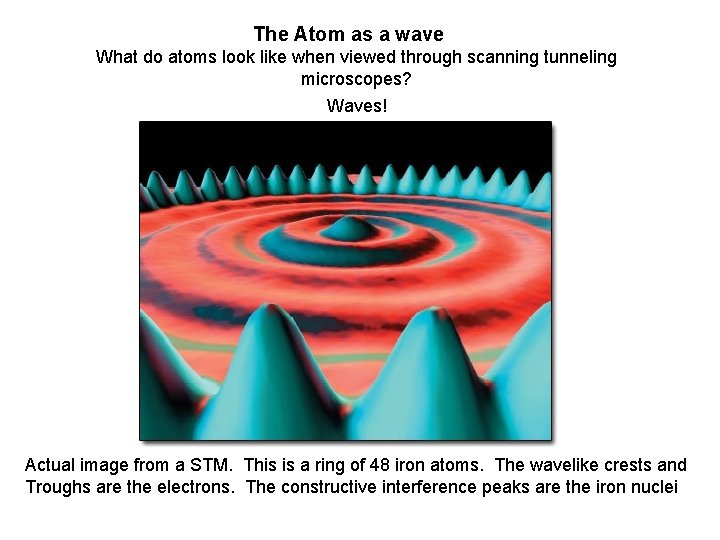

The Atom as a wave What do atoms look like when viewed through scanning tunneling microscopes? Waves! Actual image from a STM. This is a ring of 48 iron atoms. The wavelike crests and Troughs are the electrons. The constructive interference peaks are the iron nuclei

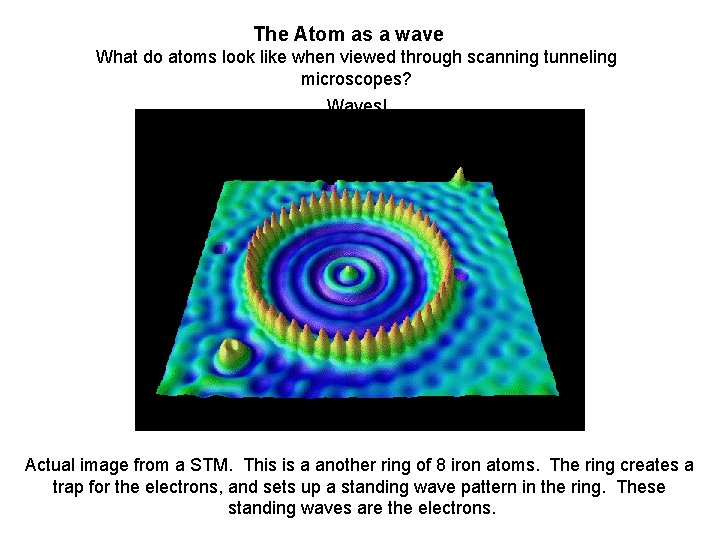

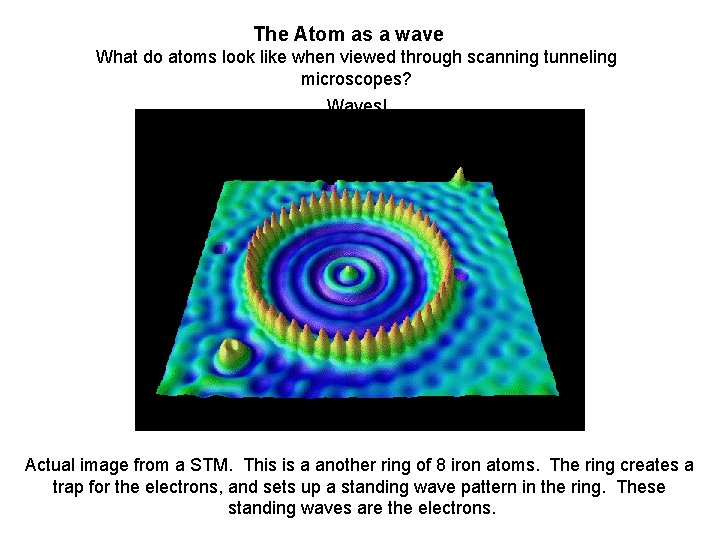

The Atom as a wave What do atoms look like when viewed through scanning tunneling microscopes? Waves! Actual image from a STM. This is a another ring of 8 iron atoms. The ring creates a trap for the electrons, and sets up a standing wave pattern in the ring. These standing waves are the electrons.

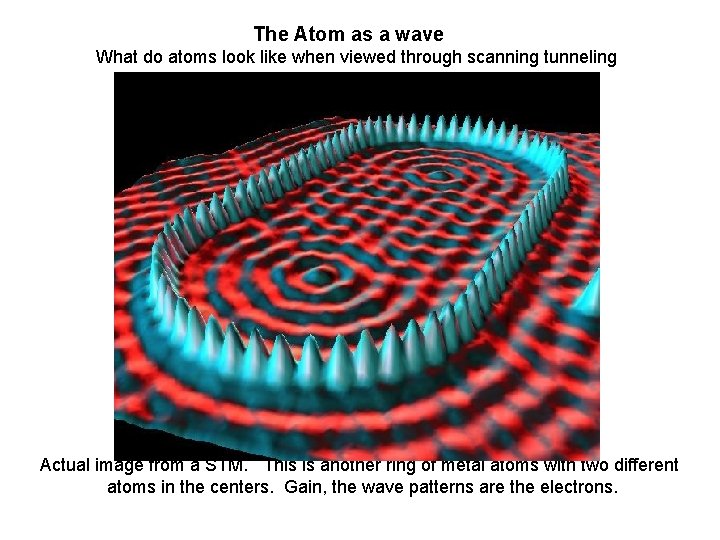

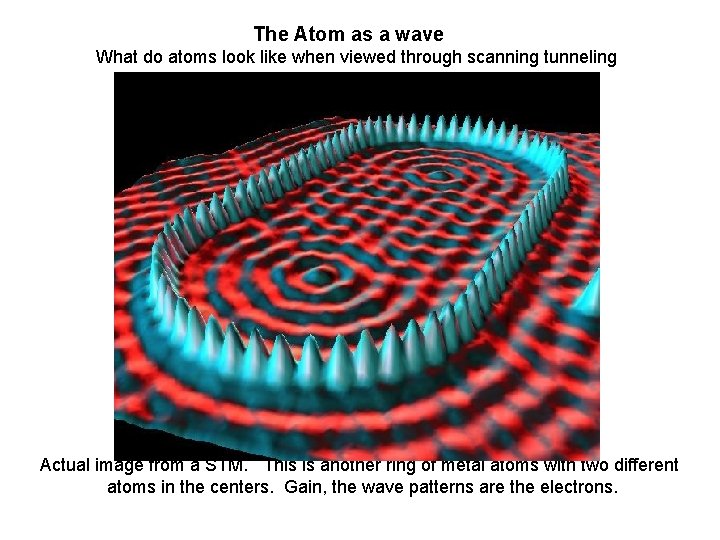

The Atom as a wave What do atoms look like when viewed through scanning tunneling microscopes? Waves! Actual image from a STM. This is another ring of metal atoms with two different atoms in the centers. Gain, the wave patterns are the electrons.

Implications of wave/particle duality on the Atom Brief history of the atom

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: When physicists started thinking of the electron (as well as P+ and N) as a wave and not a particle, many breakthroughs were made and new technologies still continue to be developed.

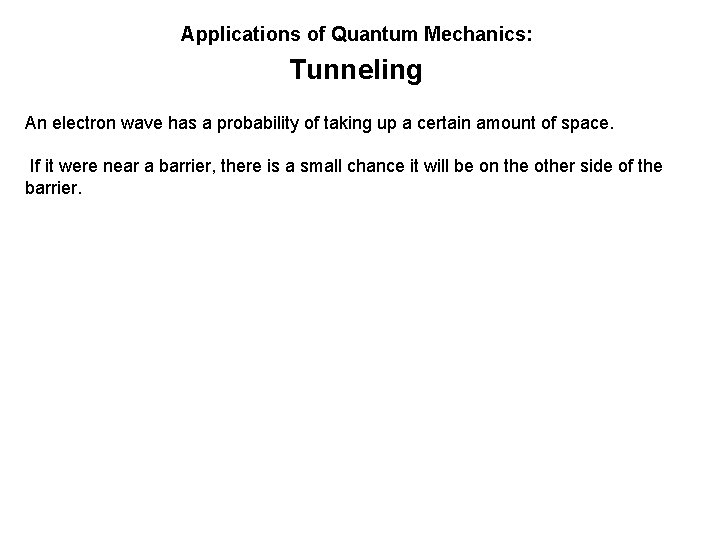

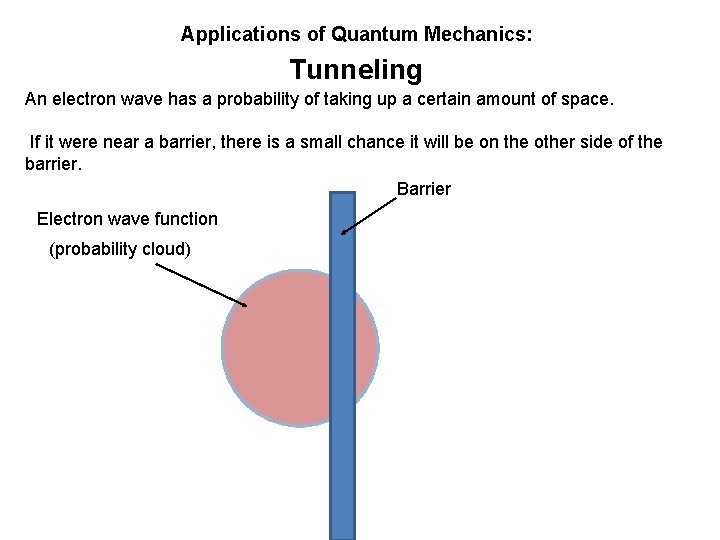

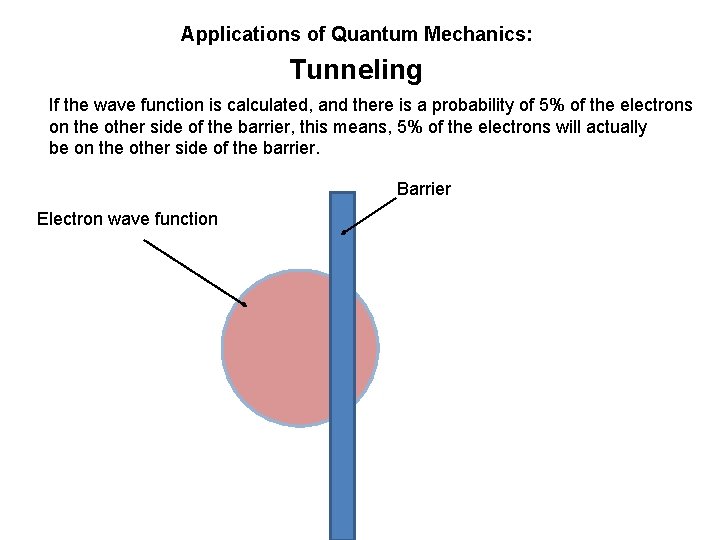

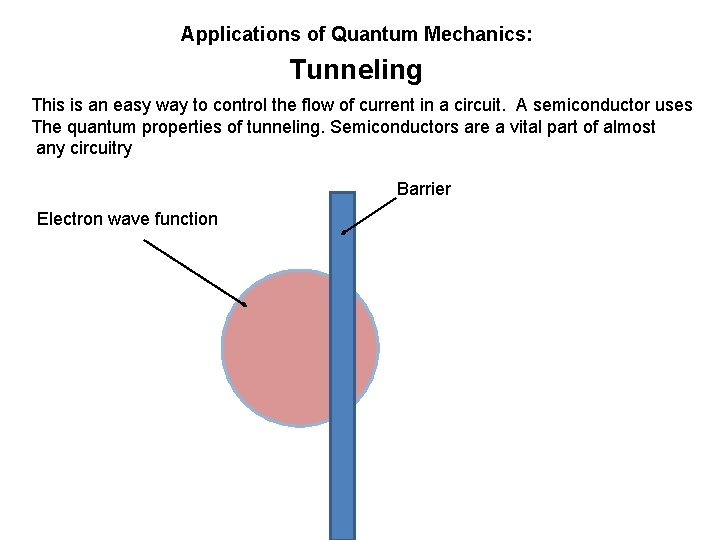

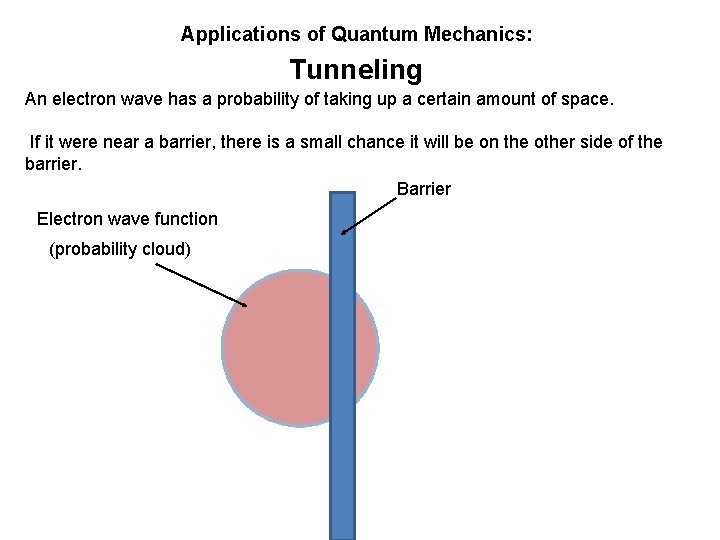

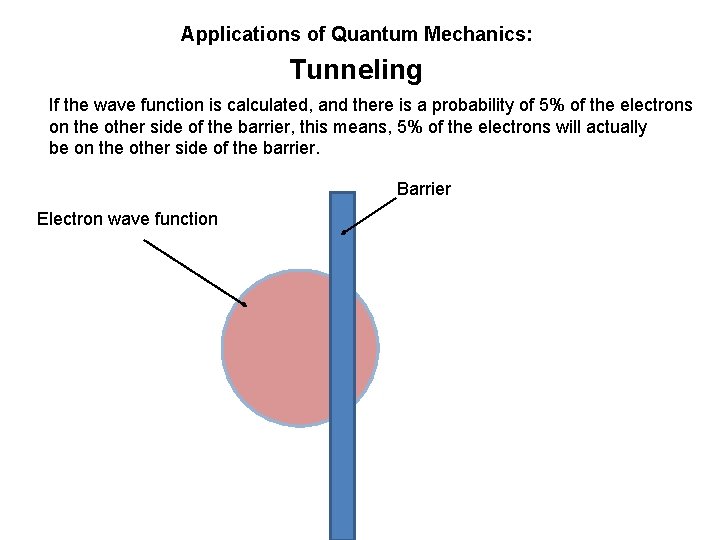

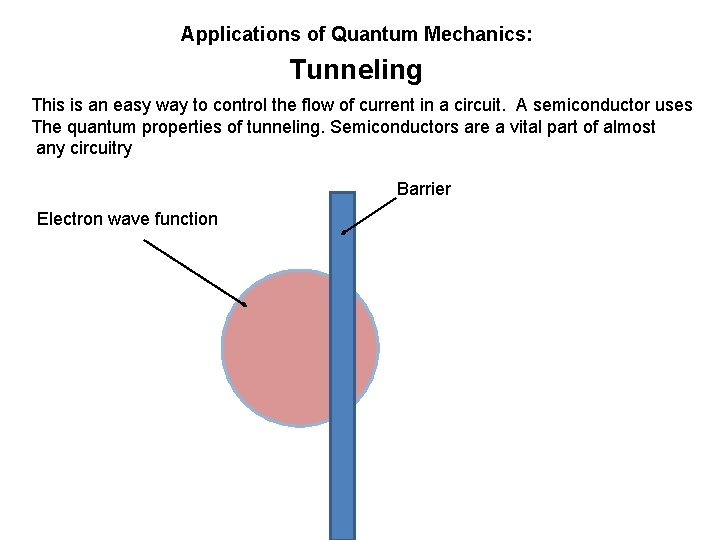

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Tunneling An electron wave has a probability of taking up a certain amount of space. If it were near a barrier, there is a small chance it will be on the other side of the barrier.

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Tunneling An electron wave has a probability of taking up a certain amount of space. If it were near a barrier, there is a small chance it will be on the other side of the barrier. Barrier Electron wave function (probability cloud)

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Tunneling If the wave function is calculated, and there is a probability of 5% of the electrons on the other side of the barrier, this means, 5% of the electrons will actually be on the other side of the barrier. Barrier Electron wave function

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Tunneling This is an easy way to control the flow of current in a circuit. A semiconductor uses The quantum properties of tunneling. Semiconductors are a vital part of almost any circuitry Barrier Electron wave function

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Tunneling

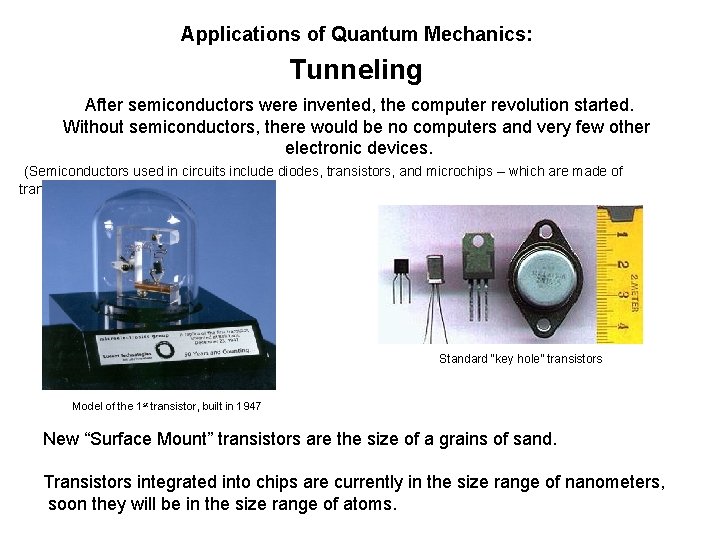

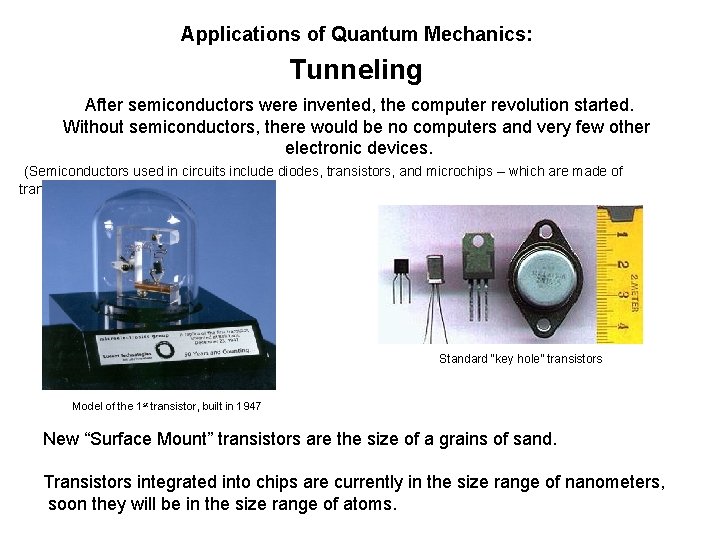

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Tunneling After semiconductors were invented, the computer revolution started. Without semiconductors, there would be no computers and very few other electronic devices. (Semiconductors used in circuits include diodes, transistors, and microchips – which are made of transistors) Standard “key hole” transistors Model of the 1 st transistor, built in 1947 New “Surface Mount” transistors are the size of a grains of sand. Transistors integrated into chips are currently in the size range of nanometers, soon they will be in the size range of atoms.

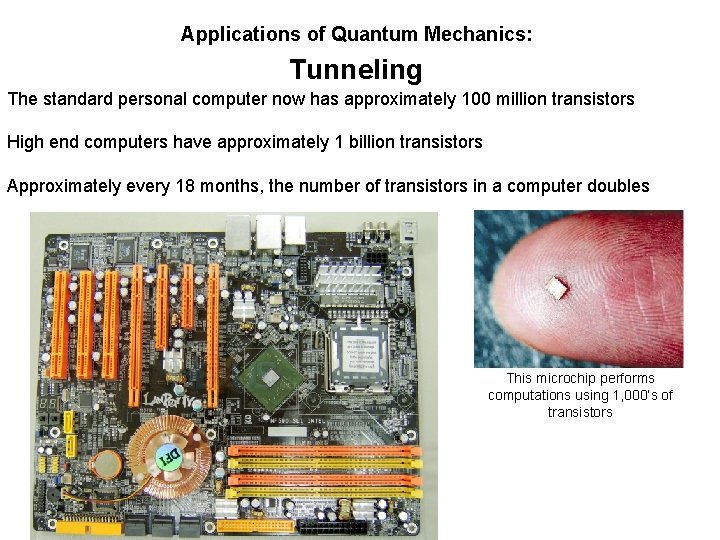

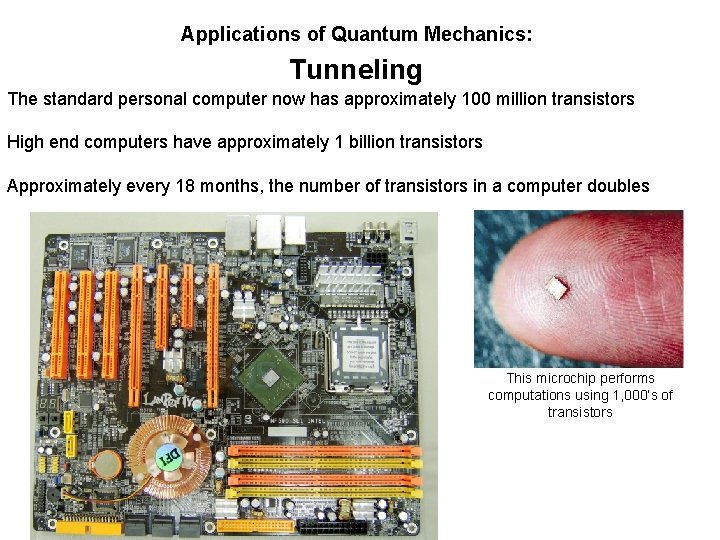

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Tunneling The standard personal computer now has approximately 100 million transistors High end computers have approximately 1 billion transistors Approximately every 18 months, the number of transistors in a computer doubles This microchip performs computations using 1, 000’s of transistors

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Quantum Entanglement Developed by Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen in 1935. It’s now called the EPR paradox. Einstein refused to believe it calling it “spooky action at a distance” and insisting it was caused by an error in his math. Finally, in 1980, Alain Aspect experimentally verified quantum entanglement.

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Quantum Entanglement What is quantum entanglement? In the press it is often called quantum teleportation. However that is very misleading. If a particle is created in a pair, such as two photons emitted by a single source, the quantum properties of the photons are somehow linked so that one always knows what the other is doing. When an aspect of one photon’s quantum state is measured, the other photon instantly changes in response, even when the two photons are separated by large distances.

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Quantum Entanglement What is quantum entanglement? Explanation for dummies: You have two crayons out of a box, one red and one blue. You don’t look at the crayons and mail a random one to Alaska. The person you mailed it to wants a blue crayon, you can measure your crayon at home and say it’s red, This will instantly cause the persons crayon in Alaska to turn blue. If the person in Alaska wanted a blue crayon, you can measure your crayon at home and say it’s blue, the persons crayon in Alaska will instantly turn red. As soon as you measure the color of your crayon, the color of the Alaska crayon will instantly turn the opposite color. However, you can choose the color of your crayon by the type of measurement made, thereby instantly changing the color of the Alaska crayon to whichever color you want. (Action at a distance)

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Quantum Entanglement What is quantum entanglement? Why does this happen?

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Quantum Entanglement What is quantum entanglement? Why does this happen? We don’t know! Quantum mechanics just says it DOES happen and it’s been experimentally verified.

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Quantum Entanglement

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Quantum Entanglement, Wave Superposition, and Quantum vacuum fluxuations are the principles behind the development of quantum computers. Quantum computers are currently in their infancy. They were theorized in 1981 (after quantum entanglement was verified in 1980), and are still being developed. A quantum computer will be able to perform calculations using virtually no processing power in virtually no time. They will be 10, 000’s of times faster and much smaller than today's computers. Today's computers use “bits of data…megabytes, gigabytes, etc…Each bit has a value of 1 or 0. Quantum computers use the superposition of wave functions “qubits” instead of bits. Each wave function can be 1 or 0 or both at the same time (superposition of the wave function).

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Quantum Entanglement, Wave Superposition, and Quantum vacuum fluxuations are the principles behind the development of quantum computers. Since a “qubit” can have all values, Calculations can be performed without actually running the calculations. Each photon or electron can occupy multiple places simultaneously (wave nature), However, it can only make an actual appearance at one location. Its presence defines its path, and that can, in a very strange way, negate the need for the algorithm (calculation) to run. In a nutshell: the photons or electron states that never existed can perform the calculations, and because of entanglement, the real photon or electron will have the answer (state = 1 or 0). A quantum computer can solve a problem without ever running the problem. Therefore, it’s really fast!

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Quantum Computers

Applications of Quantum Mechanics: Quantum Computers

Quantum Mechanics Review: