Modeling Repeated Measures or Longitudinal Data Example Annual

- Slides: 48

Modeling Repeated Measures or Longitudinal Data

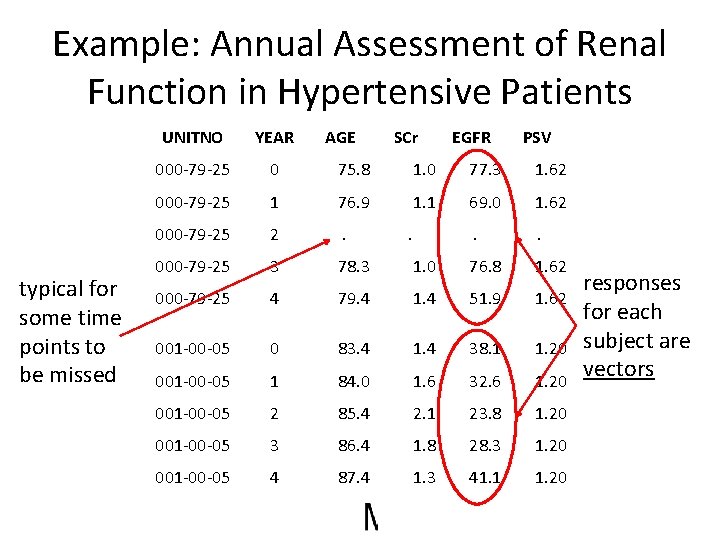

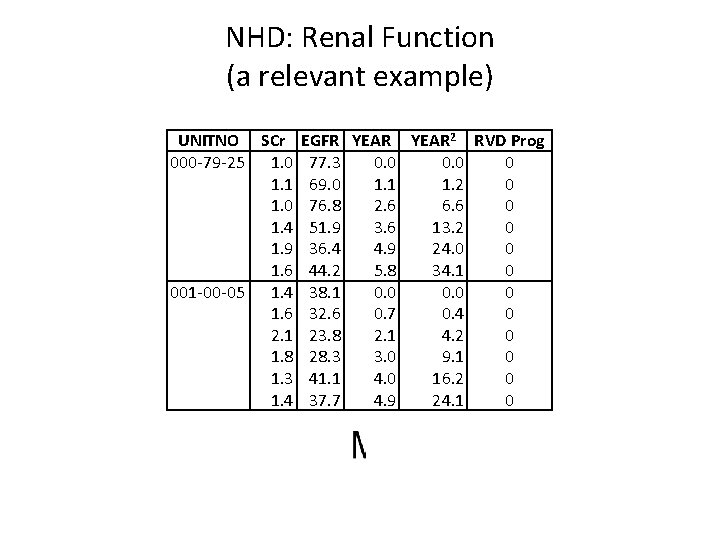

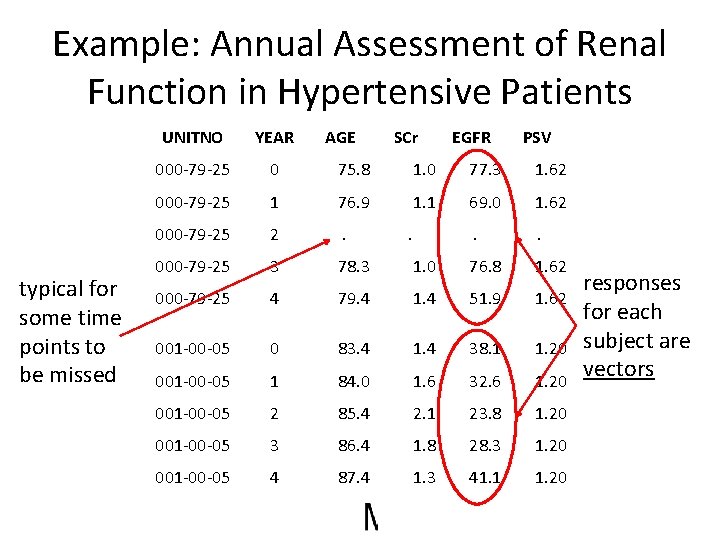

Example: Annual Assessment of Renal Function in Hypertensive Patients typical for some time points to be missed UNITNO YEAR AGE SCr 000 -79 -25 0 75. 8 1. 0 77. 3 1. 62 000 -79 -25 1 76. 9 1. 1 69. 0 1. 62 000 -79 -25 2 . . . 000 -79 -25 3 78. 3 1. 0 76. 8 1. 62 000 -79 -25 4 79. 4 1. 4 51. 9 1. 62 001 -00 -05 0 83. 4 1. 4 38. 1 1. 20 001 -00 -05 1 84. 0 1. 6 32. 6 1. 20 001 -00 -05 2 85. 4 2. 1 23. 8 1. 20 001 -00 -05 3 86. 4 1. 8 28. 3 1. 20 001 -00 -05 4 87. 4 1. 3 41. 1 1. 20 . EGFR PSV responses for each subject are vectors

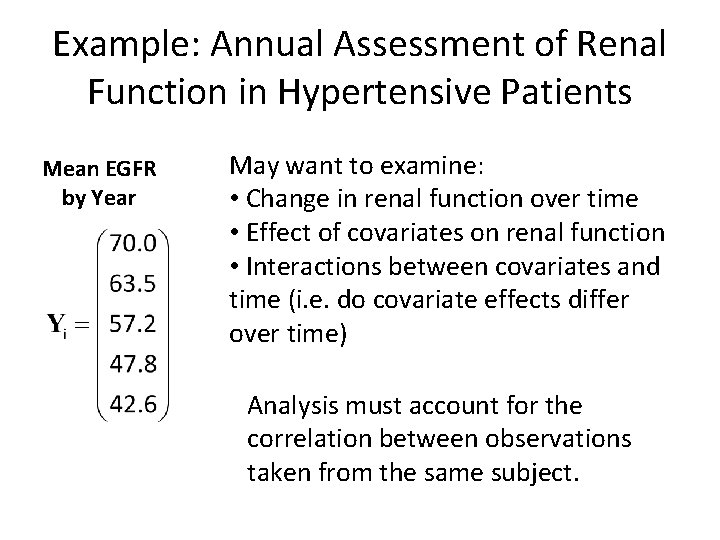

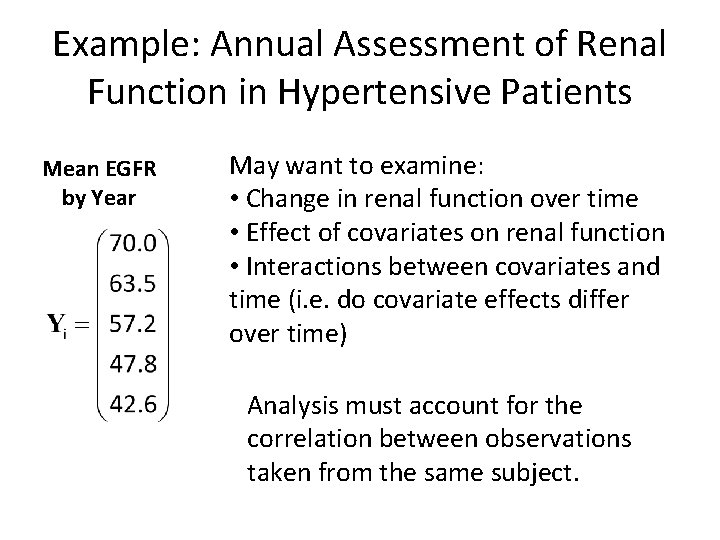

Example: Annual Assessment of Renal Function in Hypertensive Patients Mean EGFR by Year May want to examine: • Change in renal function over time • Effect of covariates on renal function • Interactions between covariates and time (i. e. do covariate effects differ over time) Analysis must account for the correlation between observations taken from the same subject.

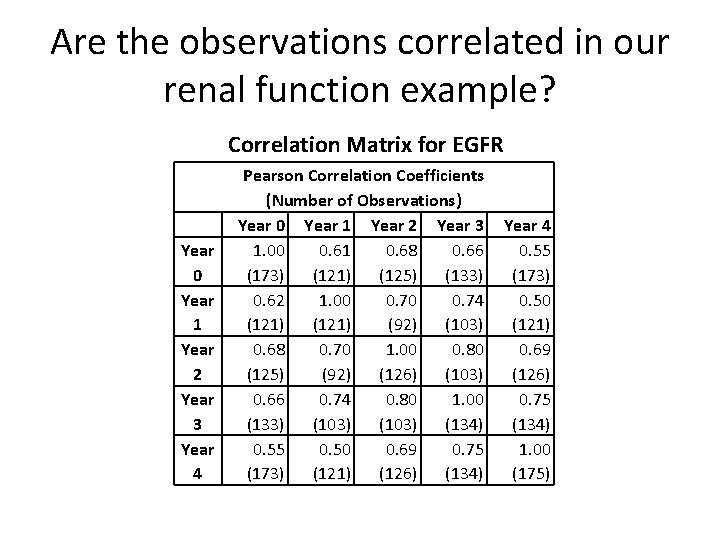

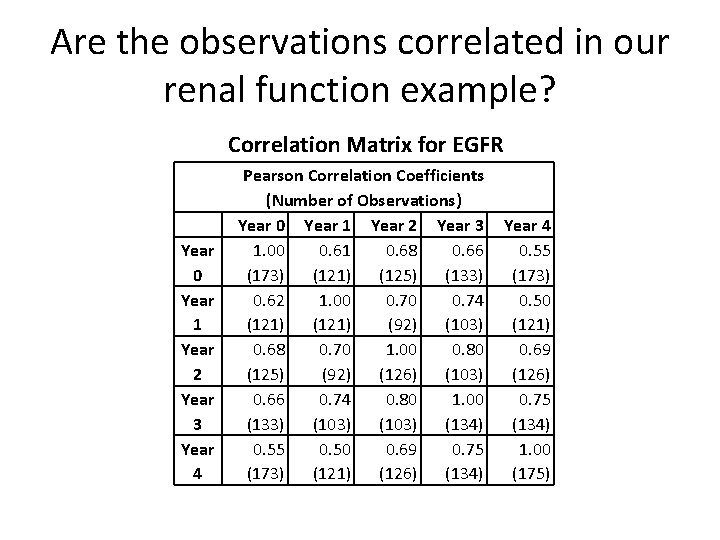

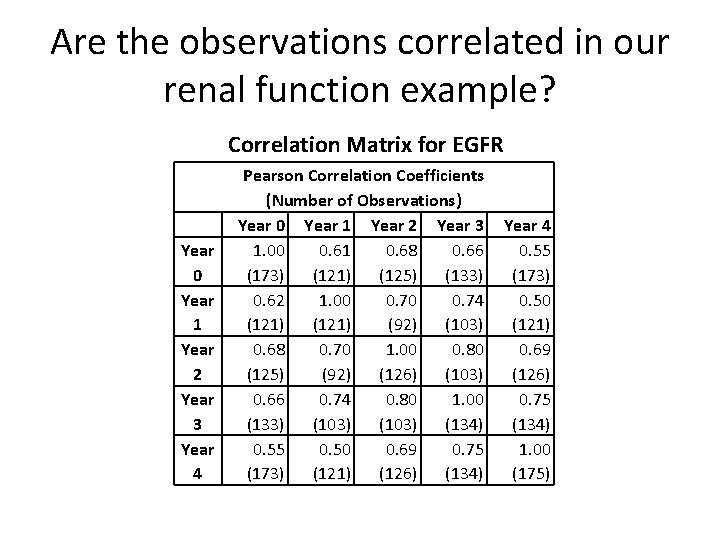

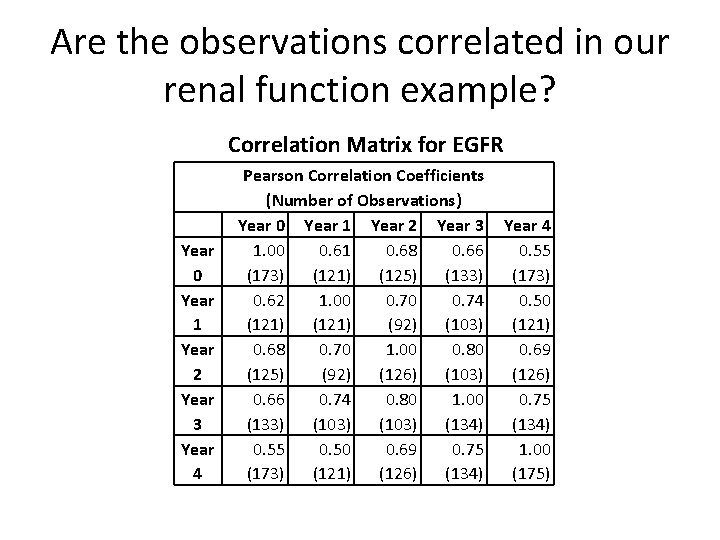

Are the observations correlated in our renal function example? Correlation Matrix for EGFR Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Pearson Correlation Coefficients (Number of Observations) Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 1. 00 0. 61 0. 68 0. 66 (173) (121) (125) (133) 0. 62 1. 00 0. 74 (121) (92) (103) 0. 68 0. 70 1. 00 0. 80 (125) (92) (126) (103) 0. 66 0. 74 0. 80 1. 00 (133) (103) (134) 0. 55 0. 50 0. 69 0. 75 (173) (121) (126) (134) Year 4 0. 55 (173) 0. 50 (121) 0. 69 (126) 0. 75 (134) 1. 00 (175)

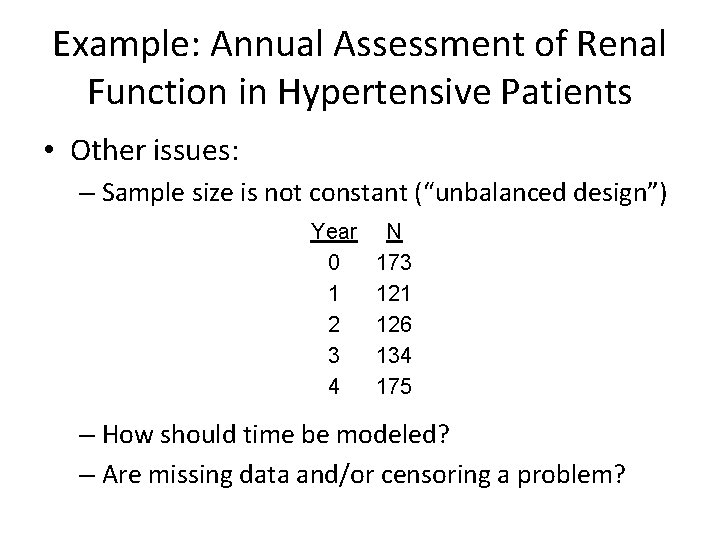

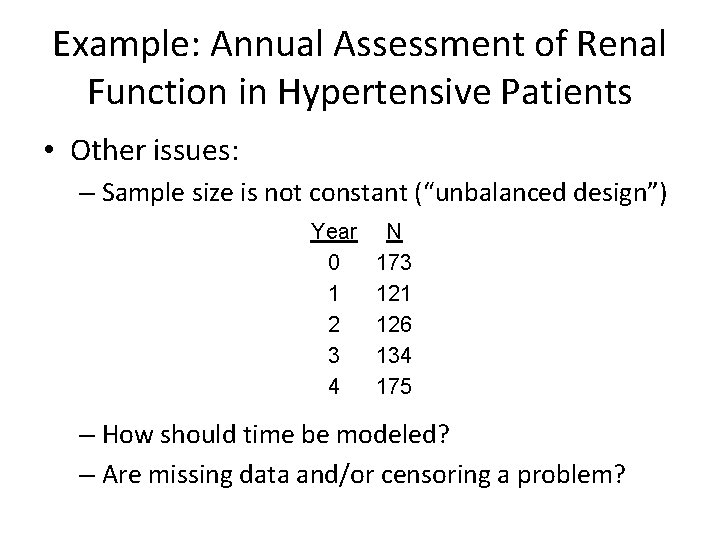

Example: Annual Assessment of Renal Function in Hypertensive Patients • Other issues: – Sample size is not constant (“unbalanced design”) Year 0 1 2 3 4 N 173 121 126 134 175 – How should time be modeled? – Are missing data and/or censoring a problem?

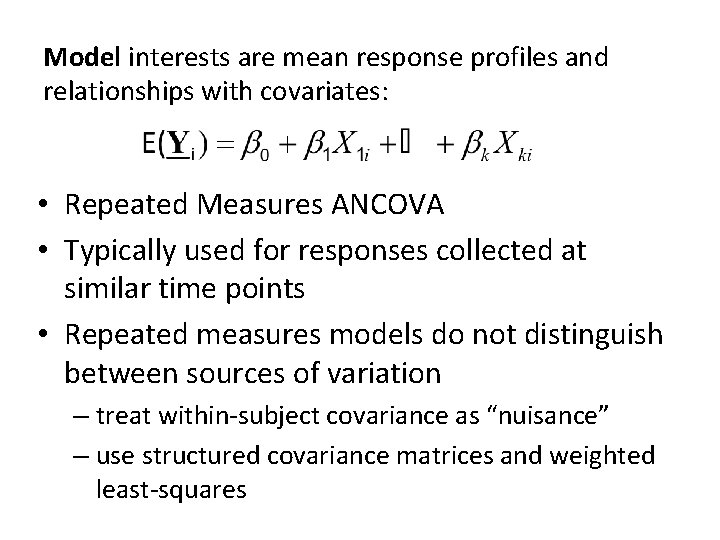

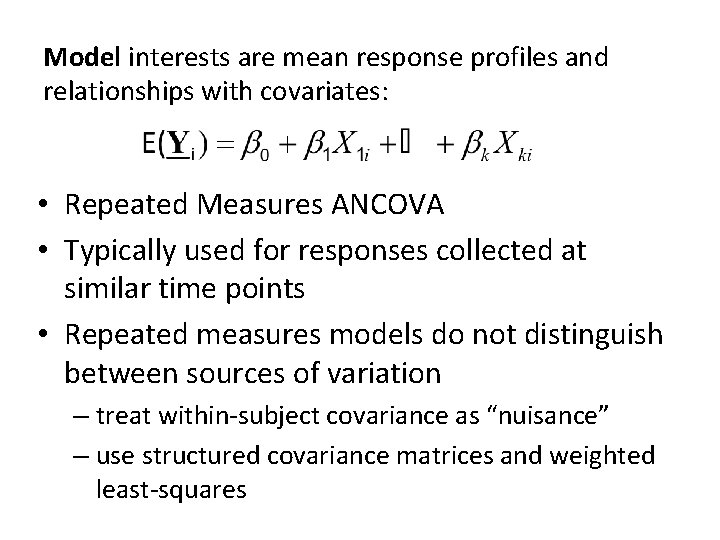

Model interests are mean response profiles and relationships with covariates: • Repeated Measures ANCOVA • Typically used for responses collected at similar time points • Repeated measures models do not distinguish between sources of variation – treat within-subject covariance as “nuisance” – use structured covariance matrices and weighted least-squares

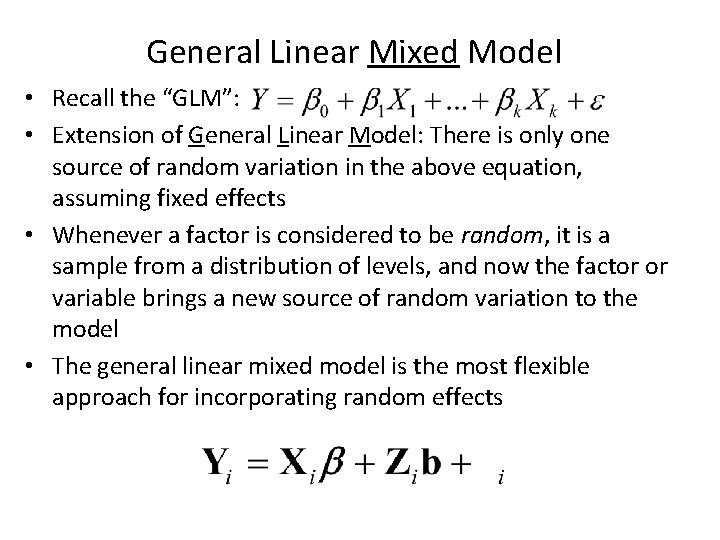

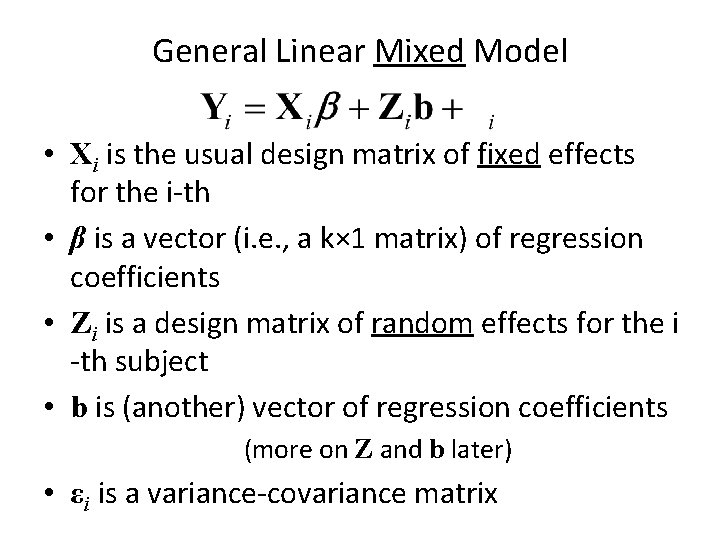

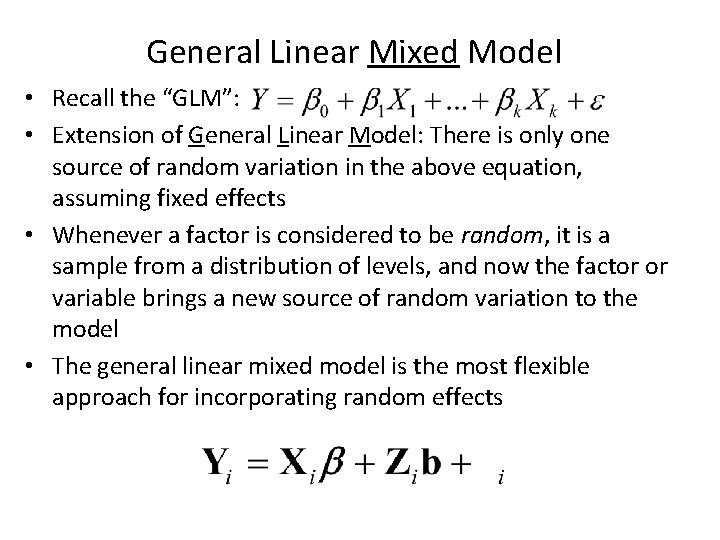

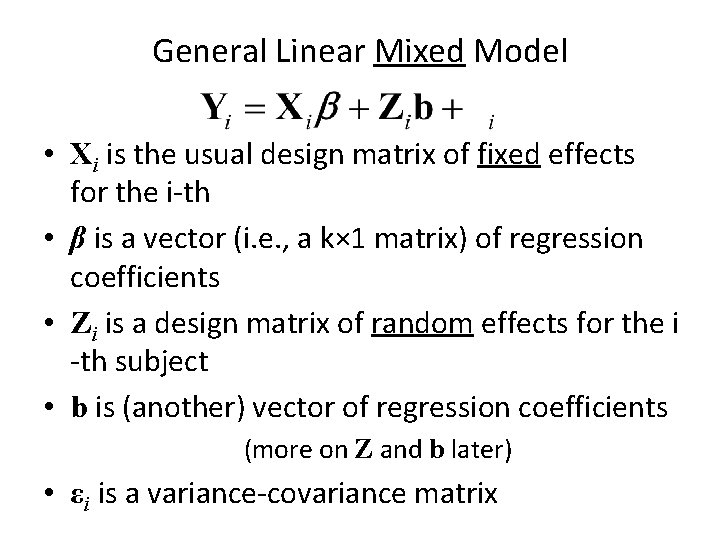

General Linear Mixed Model • Recall the “GLM”: • Extension of General Linear Model: There is only one source of random variation in the above equation, assuming fixed effects • Whenever a factor is considered to be random, it is a sample from a distribution of levels, and now the factor or variable brings a new source of random variation to the model • The general linear mixed model is the most flexible approach for incorporating random effects

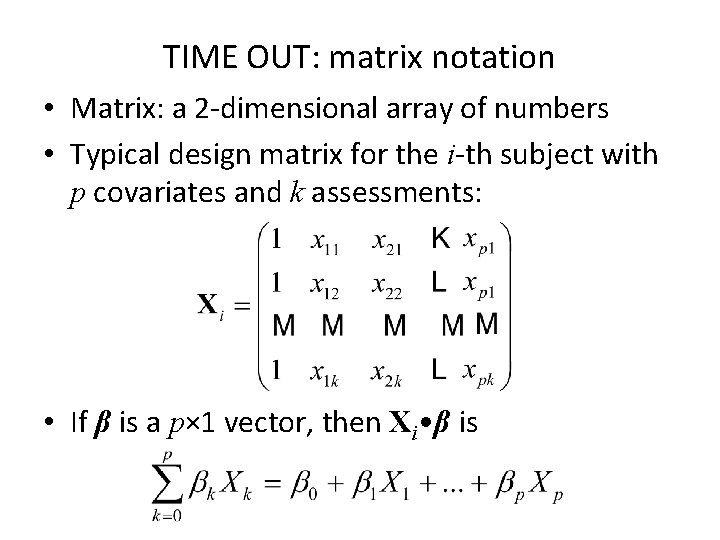

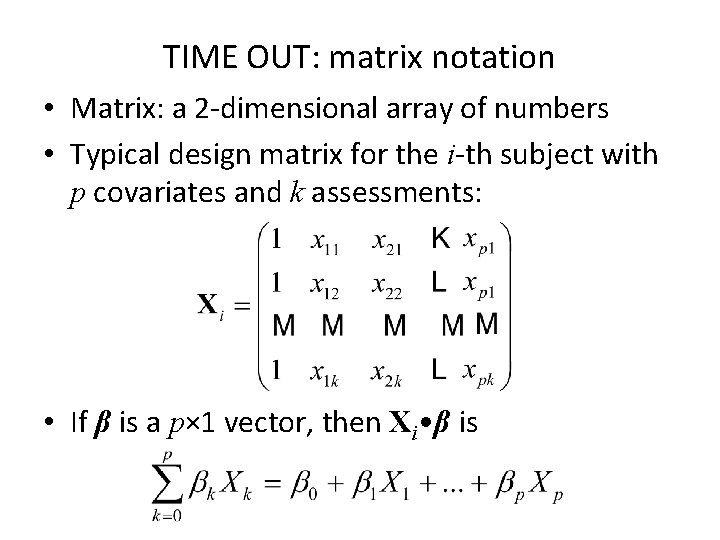

TIME OUT: matrix notation • Matrix: a 2 -dimensional array of numbers • Typical design matrix for the i-th subject with p covariates and k assessments: • If β is a p× 1 vector, then Xi • β is

General Linear Mixed Model • Xi is the usual design matrix of fixed effects for the i-th • β is a vector (i. e. , a k× 1 matrix) of regression coefficients • Zi is a design matrix of random effects for the i -th subject • b is (another) vector of regression coefficients (more on Z and b later) • εi is a variance-covariance matrix

General Linear Mixed Model • Part I: repeated (equally spaced) measures – like our renal function example • Ignore the “random effects” part of the GLMM • Concentrate on εi – No longer assume equal variances and independent observations – If we assume a known, underlying distribution for Yi (guess which one) then we can model the underlying variance – Use maximum-likelihood to estimate variances – Use weighted least-squares to estimate regression parameters

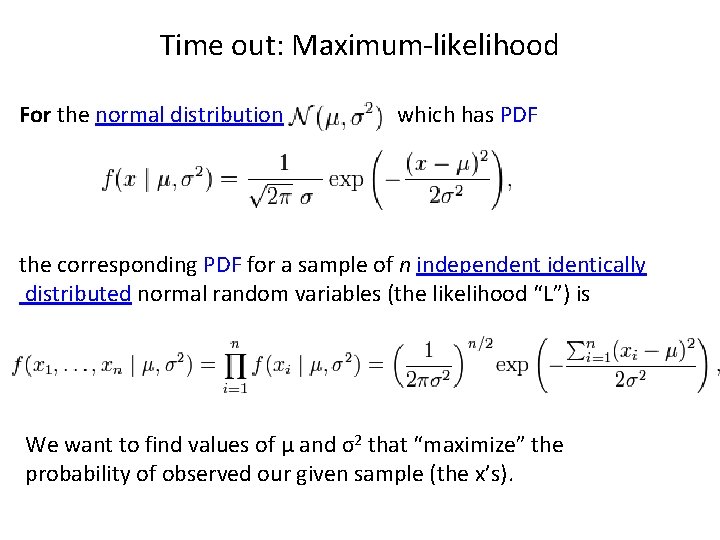

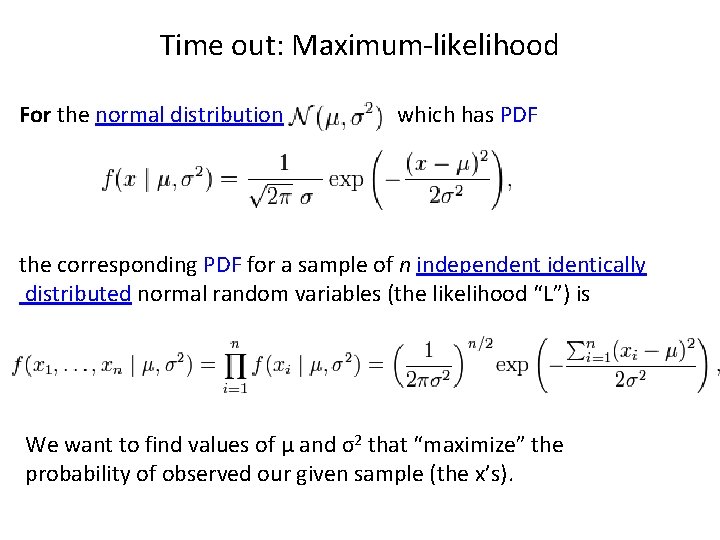

Time out: Maximum-likelihood For the normal distribution which has PDF the corresponding PDF for a sample of n independent identically distributed normal random variables (the likelihood “L”) is We want to find values of μ and σ2 that “maximize” the probability of observed our given sample (the x’s).

Time out: Maximum-likelihood • Use calculus to do this: – Because it’s easier to differentiate, take the natural log transform of L, “log(L)” – Set log(L) = 0 – Find derivatives with respect to each parameter (first μ then σ) – These represent points of inflection – Since log(L) is monotonically increasing, the inflexion points are maxima

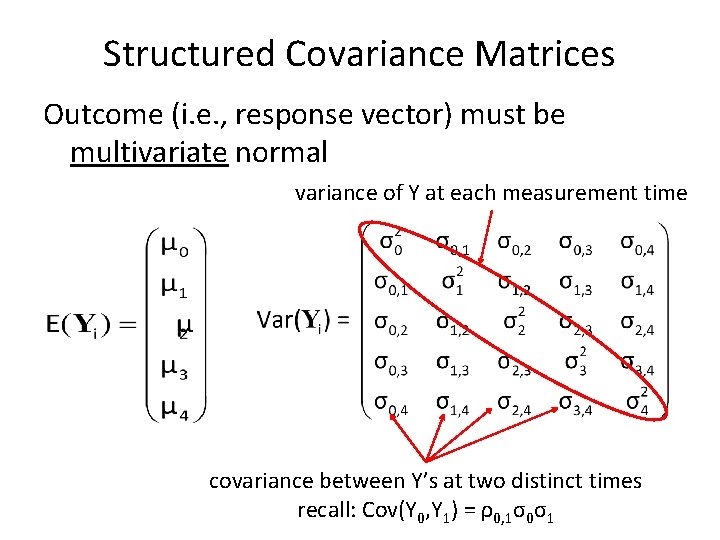

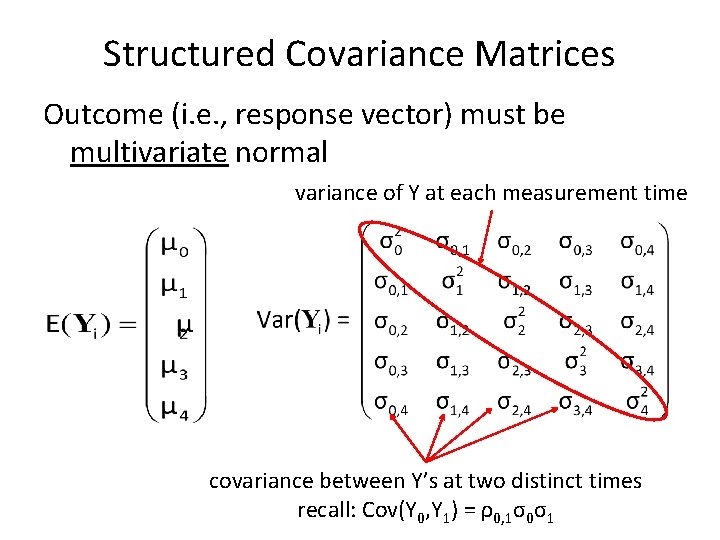

Structured Covariance Matrices Outcome (i. e. , response vector) must be multivariate normal variance of Y at each measurement time covariance between Y’s at two distinct times recall: Cov(Y 0, Y 1) = ρ0, 1σ0σ1

Covariance Structures Some common covariance structures are – Independence: assumes uncorrelated observations, usual model if no repeated measures – Compound symmetry or exchangeable: most “parsimonious”, assumes a single correlation for all repeated measures – Autoregressive: assumes diminishing correlation based on distance of observations, popular in econometric analyses – Unstructured or arbitrary: estimates every possible unique parameter

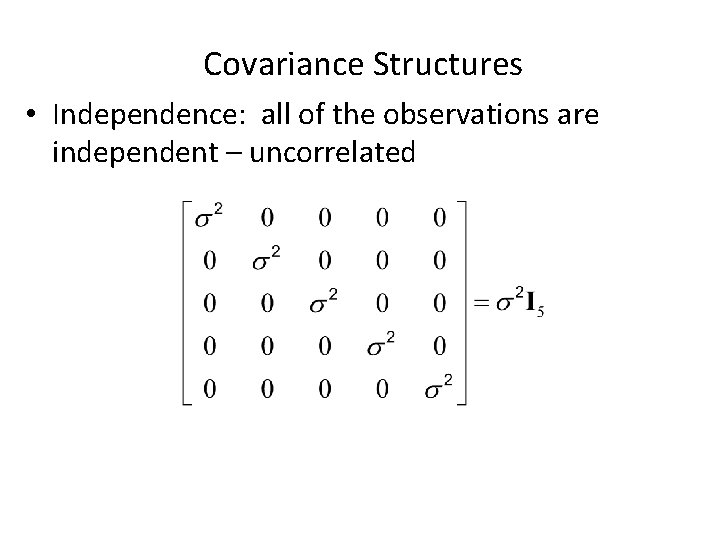

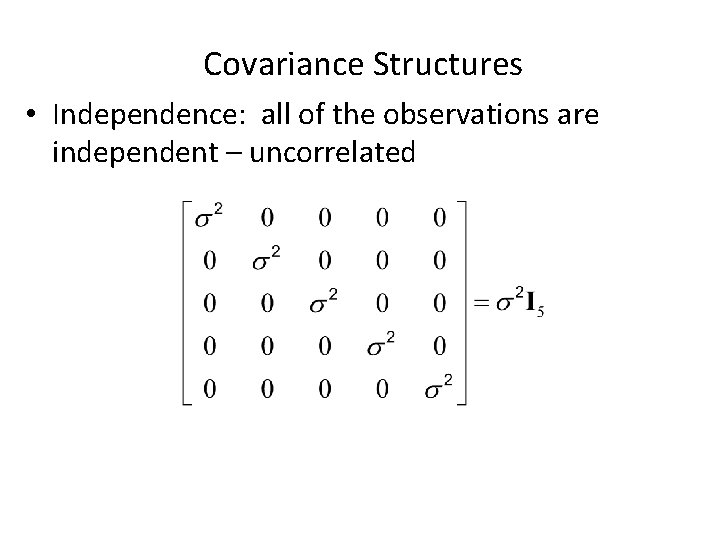

Covariance Structures • Independence: all of the observations are independent – uncorrelated

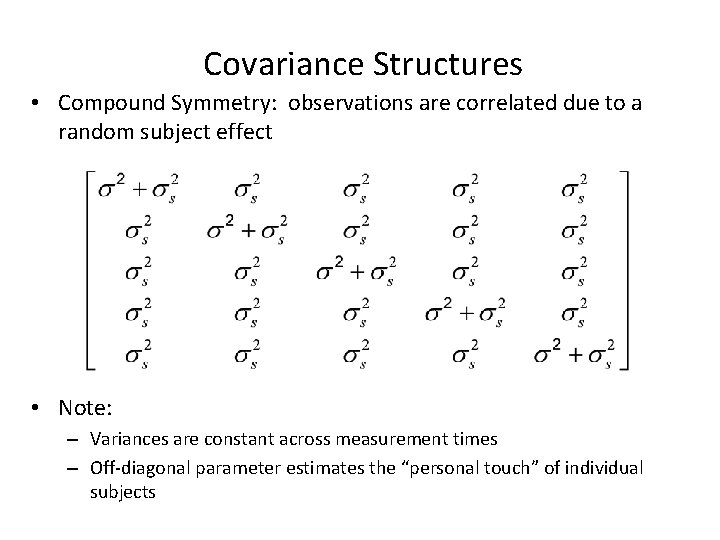

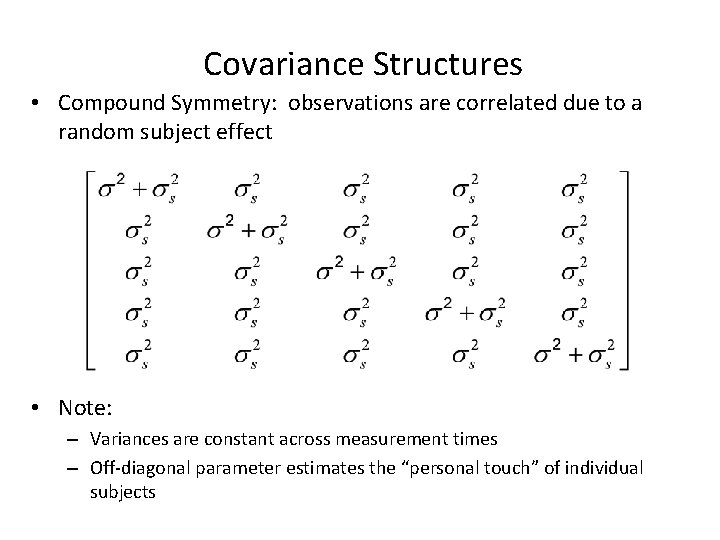

Covariance Structures • Compound Symmetry: observations are correlated due to a random subject effect • Note: – Variances are constant across measurement times – Off-diagonal parameter estimates the “personal touch” of individual subjects

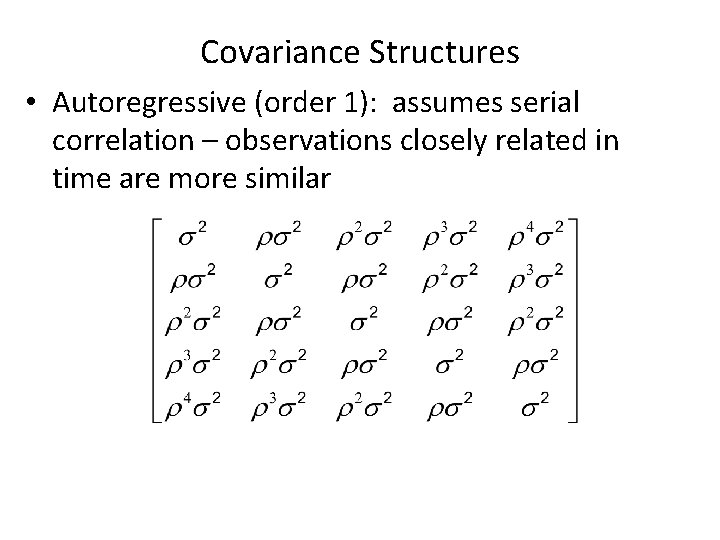

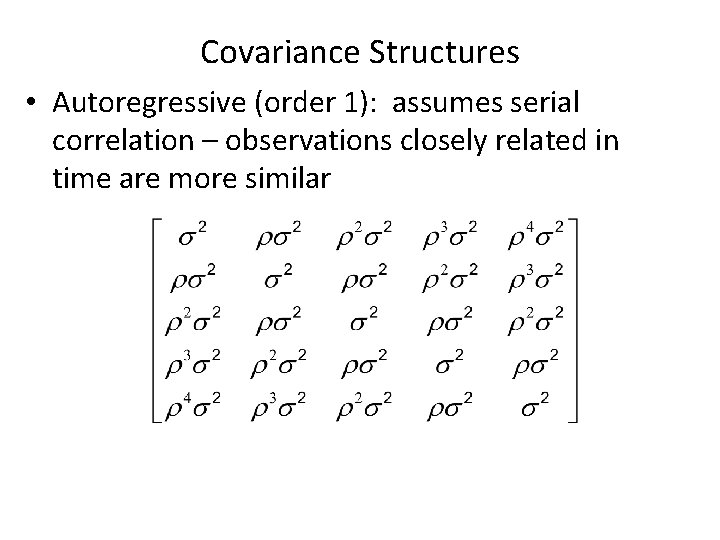

Covariance Structures • Autoregressive (order 1): assumes serial correlation – observations closely related in time are more similar

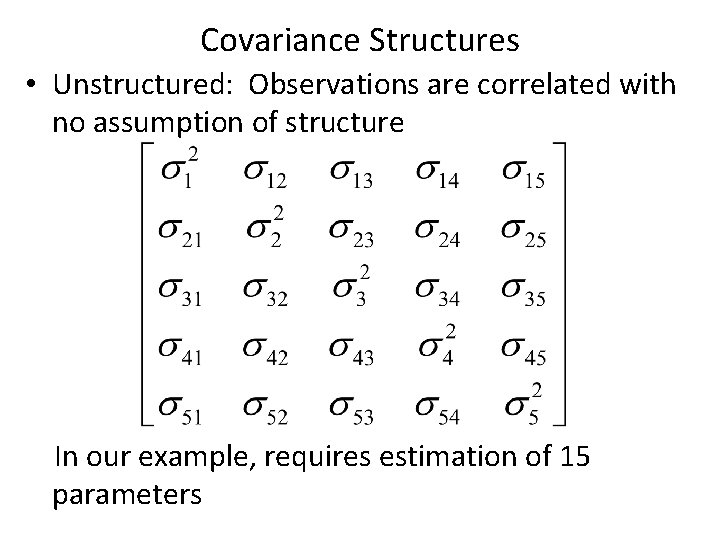

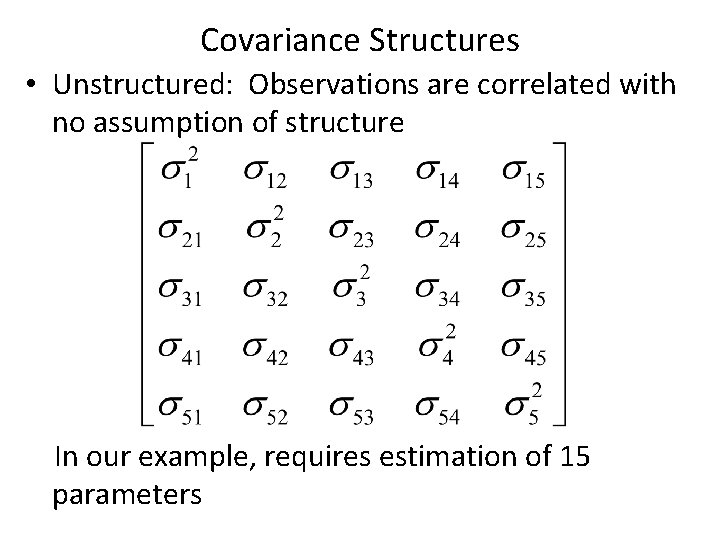

Covariance Structures • Unstructured: Observations are correlated with no assumption of structure In our example, requires estimation of 15 parameters

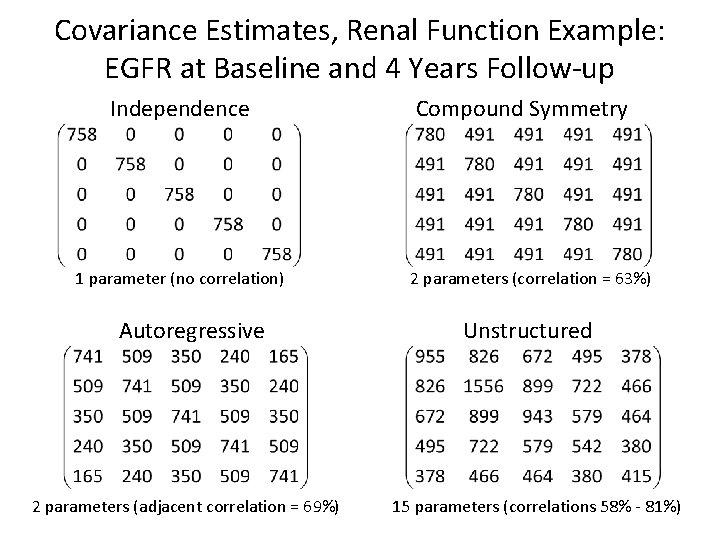

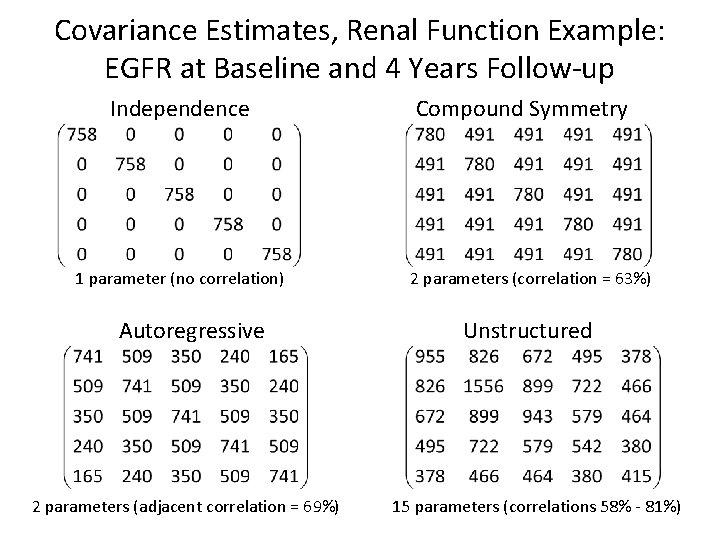

Covariance Estimates, Renal Function Example: EGFR at Baseline and 4 Years Follow-up Independence 1 parameter (no correlation) Autoregressive 2 parameters (adjacent correlation = 69%) Compound Symmetry 2 parameters (correlation = 63%) Unstructured 15 parameters (correlations 58% - 81%)

Are the observations correlated in our renal function example? Correlation Matrix for EGFR Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Pearson Correlation Coefficients (Number of Observations) Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 1. 00 0. 61 0. 68 0. 66 (173) (121) (125) (133) 0. 62 1. 00 0. 74 (121) (92) (103) 0. 68 0. 70 1. 00 0. 80 (125) (92) (126) (103) 0. 66 0. 74 0. 80 1. 00 (133) (103) (134) 0. 55 0. 50 0. 69 0. 75 (173) (121) (126) (134) Year 4 0. 55 (173) 0. 50 (121) 0. 69 (126) 0. 75 (134) 1. 00 (175)

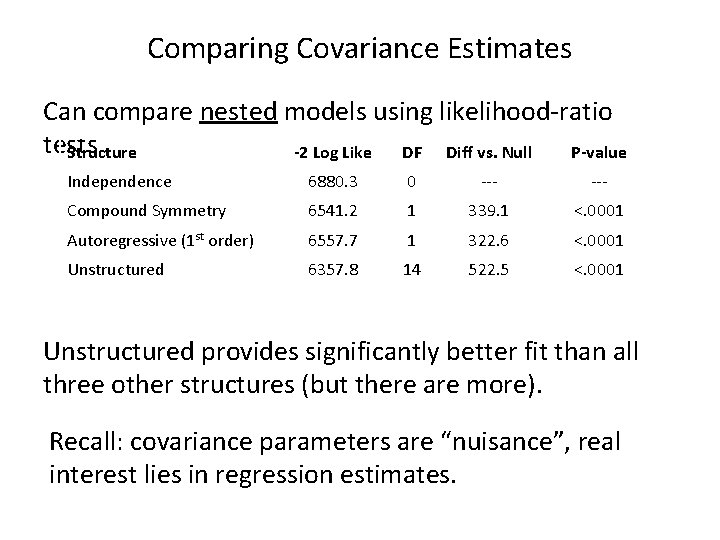

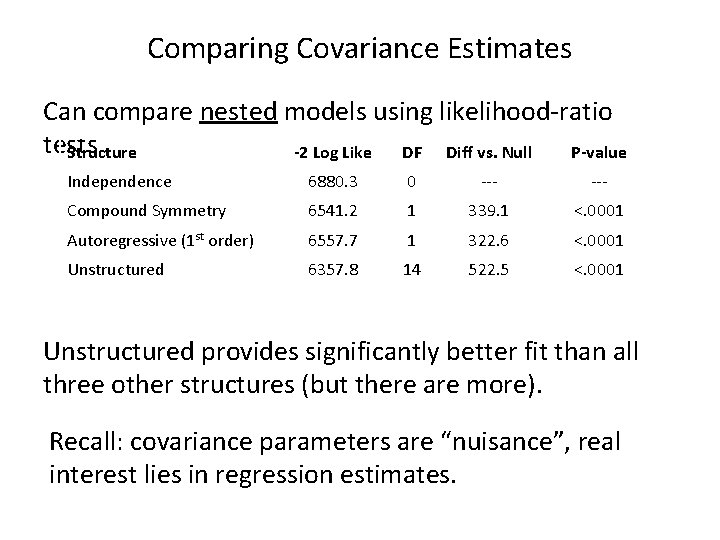

Comparing Covariance Estimates Can compare nested models using likelihood-ratio tests Structure -2 Log Like DF Diff vs. Null P-value Independence 6880. 3 0 --- Compound Symmetry 6541. 2 1 339. 1 <. 0001 Autoregressive (1 st order) 6557. 7 1 322. 6 <. 0001 Unstructured 6357. 8 14 522. 5 <. 0001 Unstructured provides significantly better fit than all three other structures (but there are more). Recall: covariance parameters are “nuisance”, real interest lies in regression estimates.

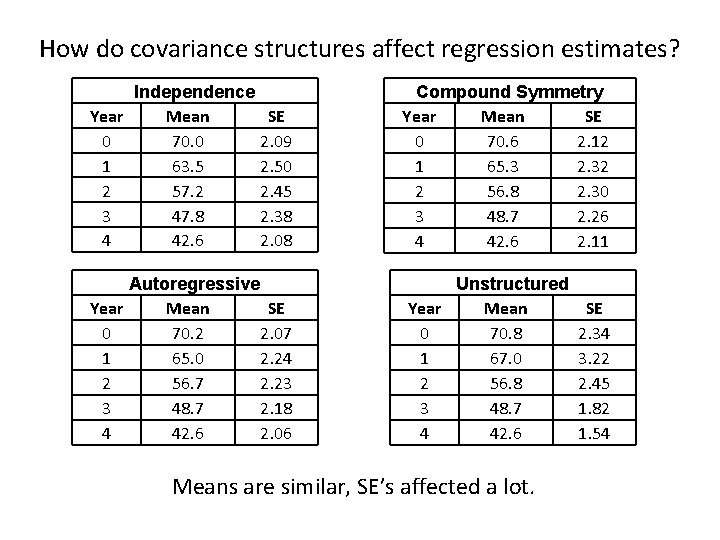

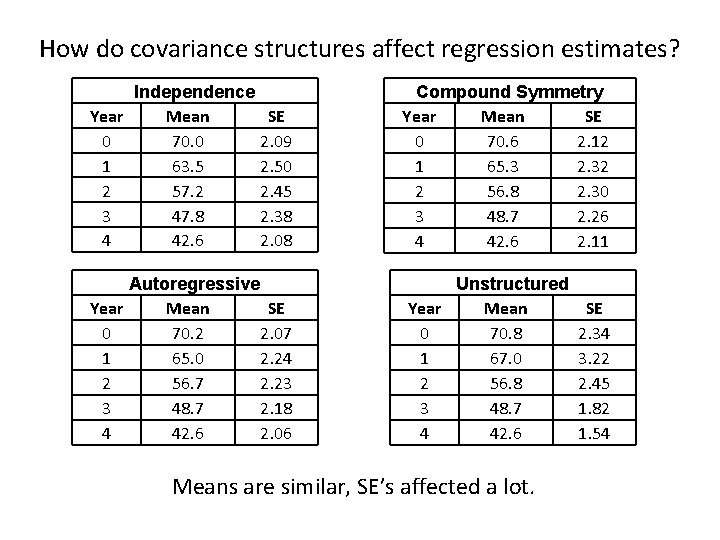

How do covariance structures affect regression estimates? Independence Year Mean SE 0 70. 0 2. 09 1 63. 5 2. 50 2 57. 2 2. 45 3 47. 8 2. 38 4 42. 6 2. 08 Compound Symmetry Year Mean SE 0 70. 6 2. 12 1 65. 3 2. 32 2 56. 8 2. 30 3 48. 7 2. 26 4 42. 6 2. 11 Autoregressive Year Mean SE 0 70. 2 2. 07 1 65. 0 2. 24 2 56. 7 2. 23 3 48. 7 2. 18 4 42. 6 2. 06 Unstructured Year Mean 0 70. 8 1 67. 0 2 56. 8 3 48. 7 4 42. 6 Means are similar, SE’s affected a lot. SE 2. 34 3. 22 2. 45 1. 82 1. 54

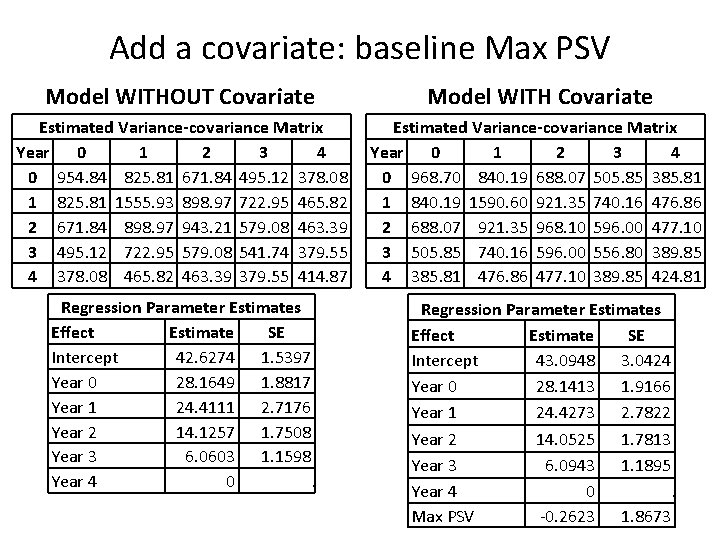

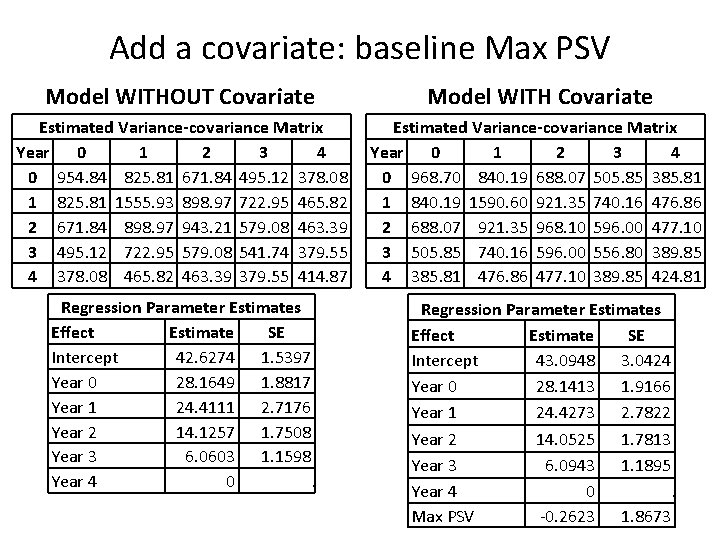

Add a covariate: baseline Max PSV Model WITHOUT Covariate Model WITH Covariate Estimated Variance-covariance Matrix Year 0 1 2 3 4 0 954. 84 825. 81 671. 84 495. 12 378. 08 1 825. 81 1555. 93 898. 97 722. 95 465. 82 2 671. 84 898. 97 943. 21 579. 08 463. 39 3 495. 12 722. 95 579. 08 541. 74 379. 55 4 378. 08 465. 82 463. 39 379. 55 414. 87 Estimated Variance-covariance Matrix Year 0 1 2 3 4 0 968. 70 840. 19 688. 07 505. 85 385. 81 1 840. 19 1590. 60 921. 35 740. 16 476. 86 2 688. 07 921. 35 968. 10 596. 00 477. 10 3 505. 85 740. 16 596. 00 556. 80 389. 85 4 385. 81 476. 86 477. 10 389. 85 424. 81 Regression Parameter Estimates Effect Estimate SE Intercept 42. 6274 1. 5397 Year 0 28. 1649 1. 8817 Year 1 24. 4111 2. 7176 Year 2 14. 1257 1. 7508 Year 3 6. 0603 1. 1598 Year 4 0. Regression Parameter Estimates Effect Estimate SE Intercept 43. 0948 3. 0424 Year 0 28. 1413 1. 9166 Year 1 24. 4273 2. 7822 Year 2 14. 0525 1. 7813 Year 3 6. 0943 1. 1895 Year 4 0. Max PSV -0. 2623 1. 8673

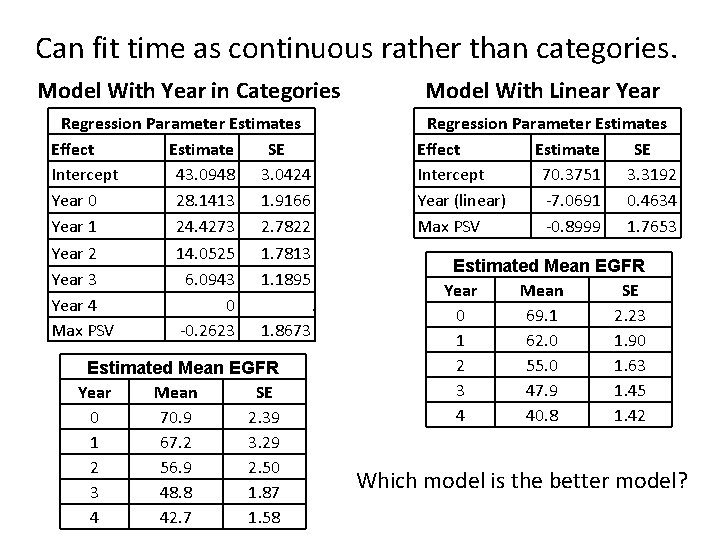

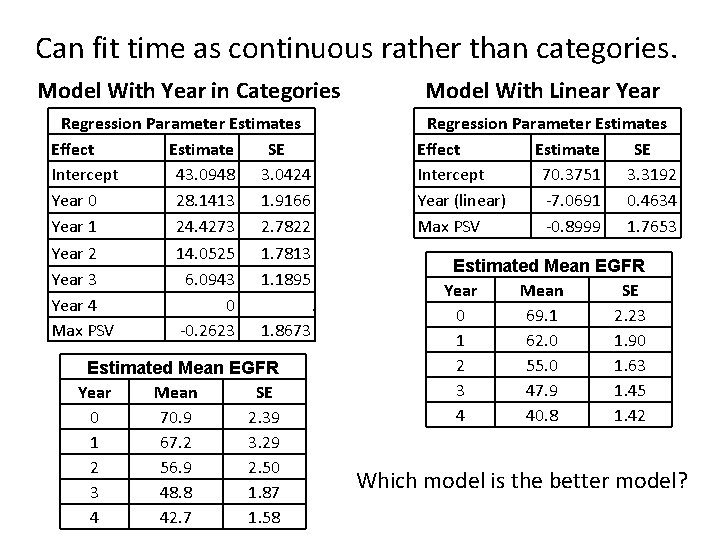

Can fit time as continuous rather than categories. Model With Year in Categories Model With Linear Year Regression Parameter Estimates Effect Estimate SE Intercept 43. 0948 3. 0424 Year 0 28. 1413 1. 9166 Year 1 24. 4273 2. 7822 Year 2 14. 0525 1. 7813 Year 3 6. 0943 1. 1895 Year 4 0. Max PSV -0. 2623 1. 8673 Regression Parameter Estimates Effect Estimate SE Intercept 70. 3751 3. 3192 Year (linear) -7. 0691 0. 4634 Max PSV -0. 8999 1. 7653 Estimated Mean EGFR Year Mean SE 0 70. 9 2. 39 1 67. 2 3. 29 2 56. 9 2. 50 3 48. 8 1. 87 4 42. 7 1. 58 Estimated Mean EGFR Year Mean SE 0 69. 1 2. 23 1 62. 0 1. 90 2 55. 0 1. 63 3 47. 9 1. 45 4 40. 8 1. 42 Which model is the better model?

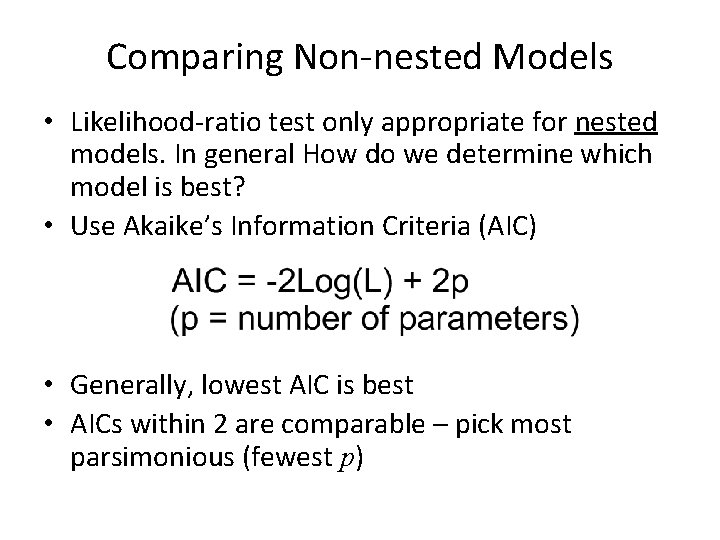

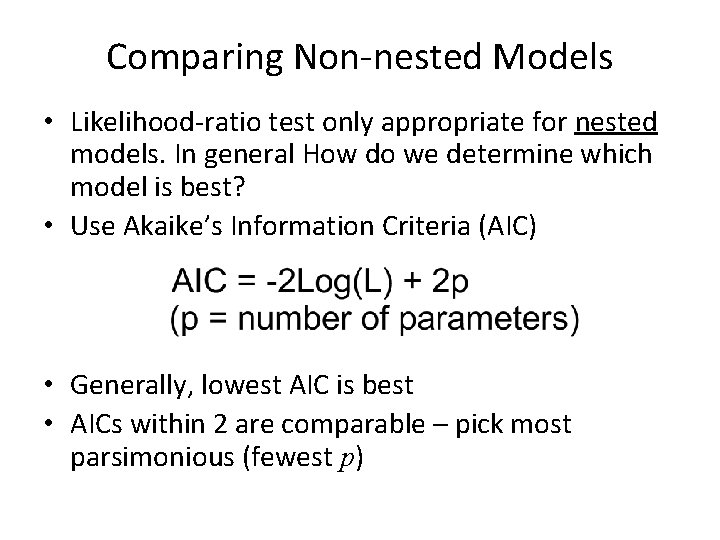

Comparing Non-nested Models • Likelihood-ratio test only appropriate for nested models. In general How do we determine which model is best? • Use Akaike’s Information Criteria (AIC) • Generally, lowest AIC is best • AICs within 2 are comparable – pick most parsimonious (fewest p)

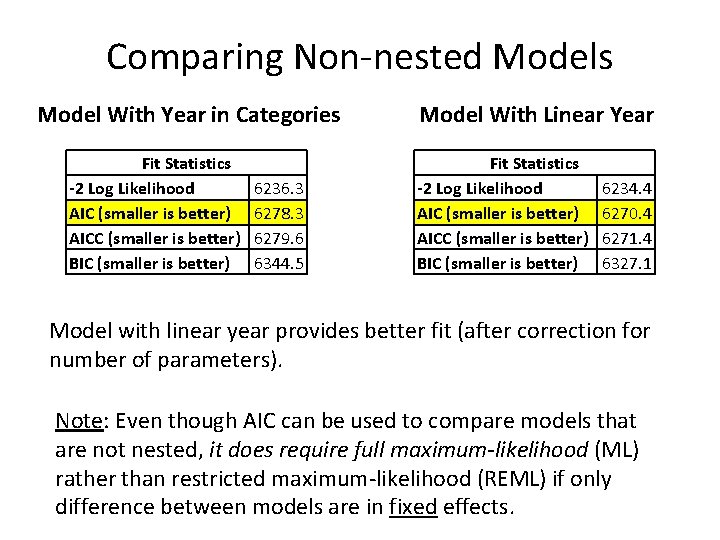

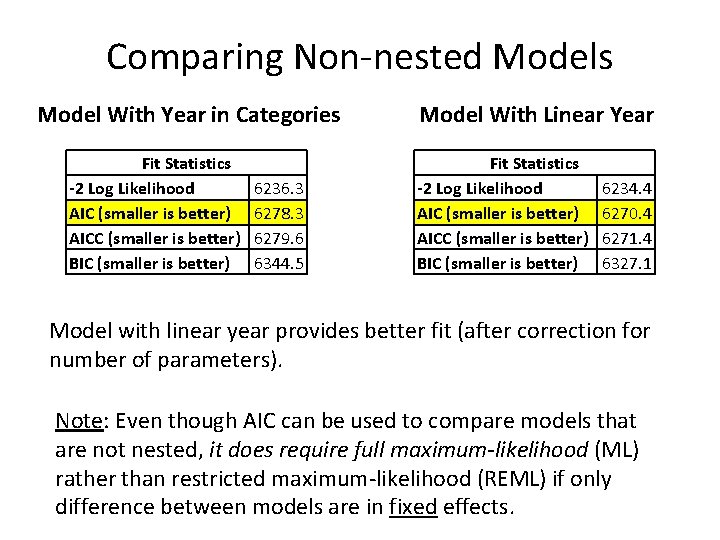

Comparing Non-nested Models Model With Year in Categories Fit Statistics -2 Log Likelihood AIC (smaller is better) AICC (smaller is better) BIC (smaller is better) 6236. 3 6278. 3 6279. 6 6344. 5 Model With Linear Year Fit Statistics -2 Log Likelihood AIC (smaller is better) AICC (smaller is better) BIC (smaller is better) 6234. 4 6270. 4 6271. 4 6327. 1 Model with linear year provides better fit (after correction for number of parameters). Note: Even though AIC can be used to compare models that are not nested, it does require full maximum-likelihood (ML) rather than restricted maximum-likelihood (REML) if only difference between models are in fixed effects.

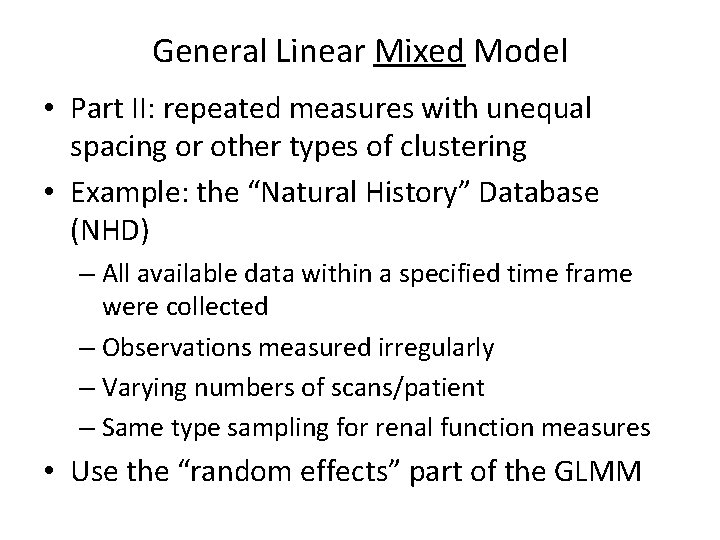

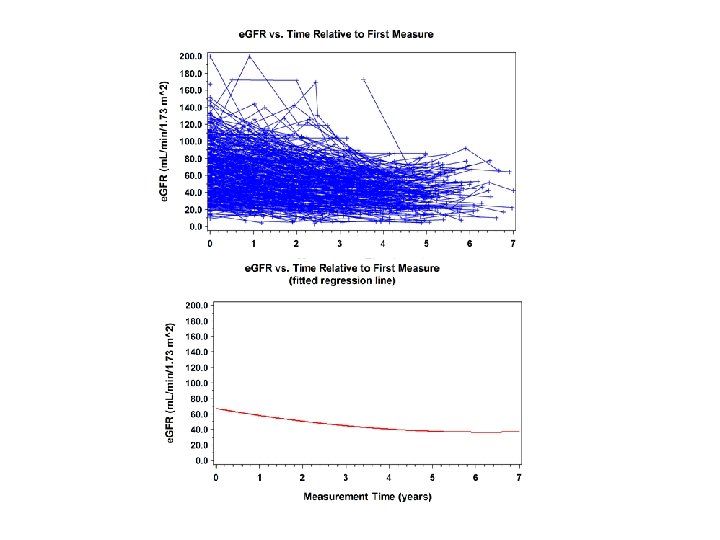

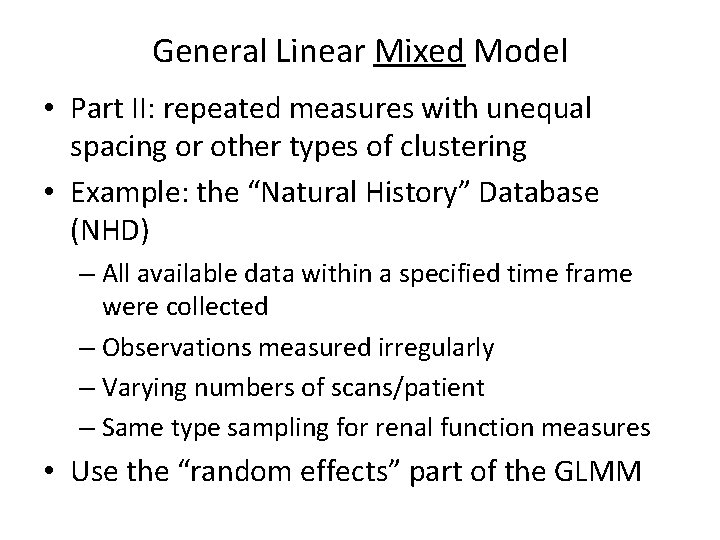

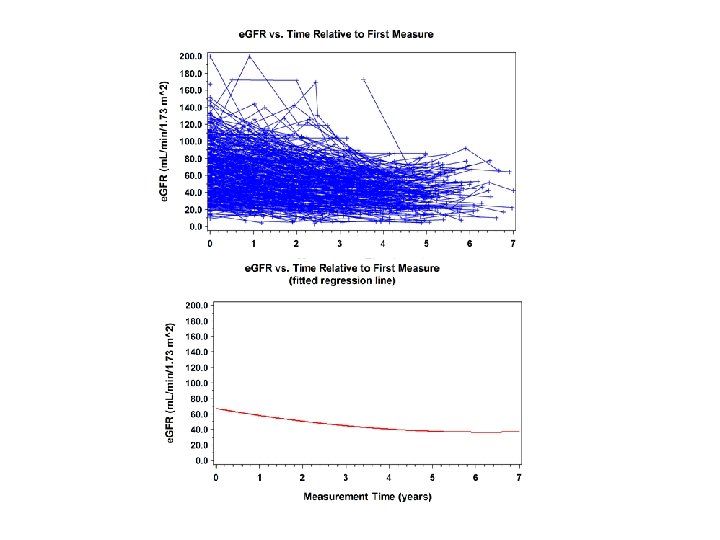

General Linear Mixed Model • Part II: repeated measures with unequal spacing or other types of clustering • Example: the “Natural History” Database (NHD) – All available data within a specified time frame were collected – Observations measured irregularly – Varying numbers of scans/patient – Same type sampling for renal function measures • Use the “random effects” part of the GLMM

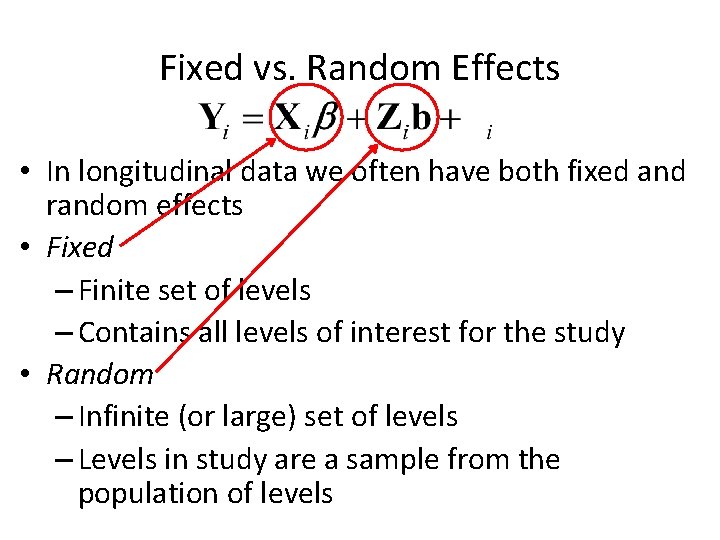

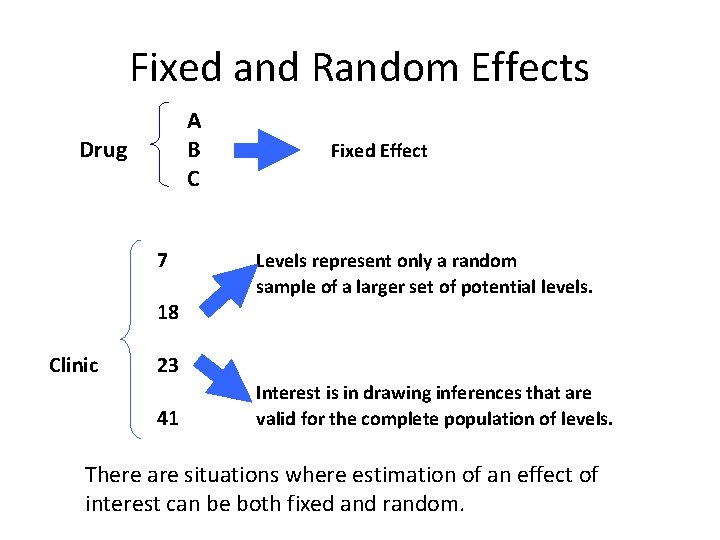

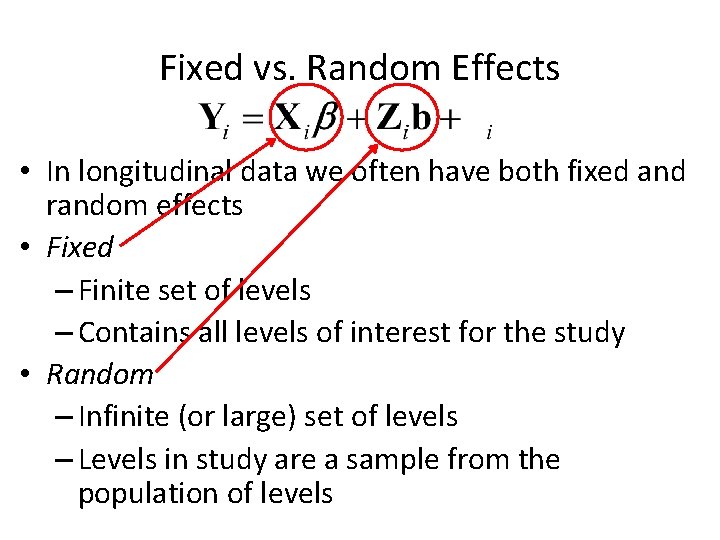

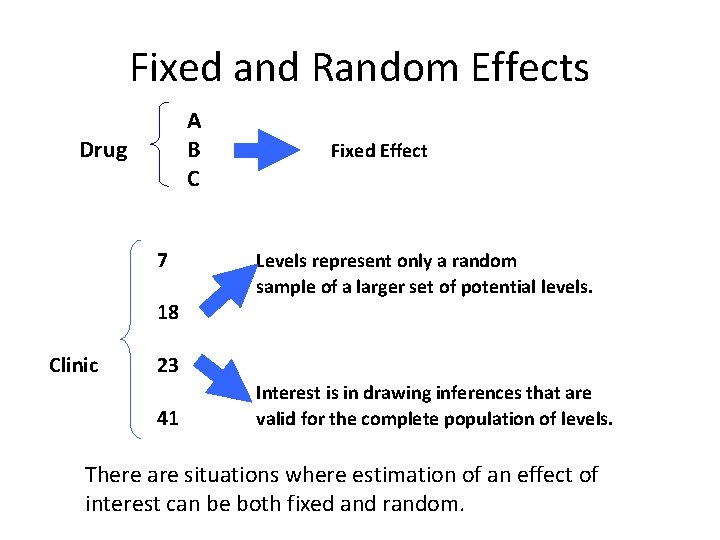

Fixed vs. Random Effects • In longitudinal data we often have both fixed and random effects • Fixed – Finite set of levels – Contains all levels of interest for the study • Random – Infinite (or large) set of levels – Levels in study are a sample from the population of levels

Fixed and Random Effects A B C Drug 7 Fixed Effect Levels represent only a random sample of a larger set of potential levels. 18 Clinic 23 41 Interest is in drawing inferences that are valid for the complete population of levels. There are situations where estimation of an effect of interest can be both fixed and random.

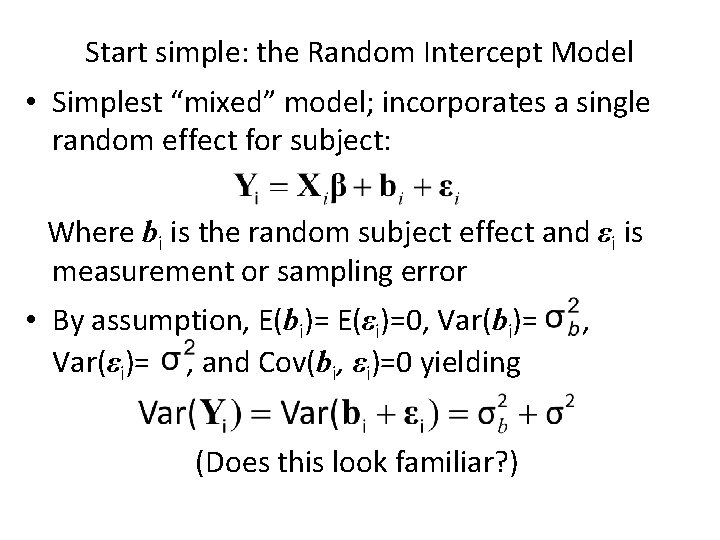

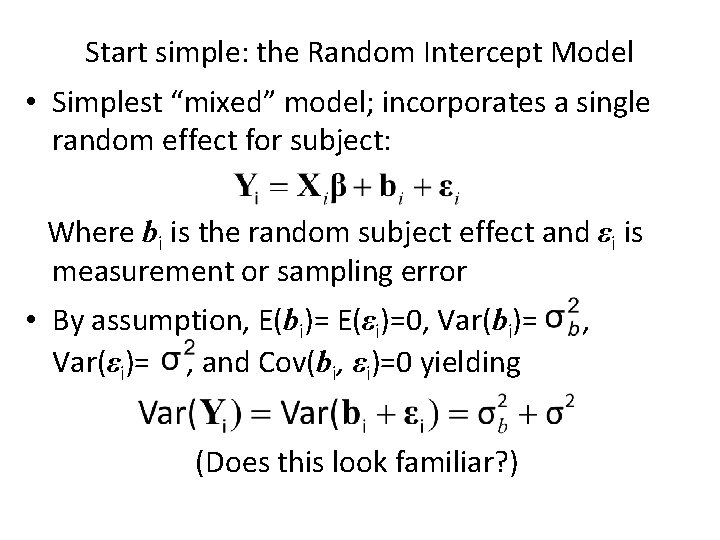

Start simple: the Random Intercept Model • Simplest “mixed” model; incorporates a single random effect for subject: Where bi is the random subject effect and εi is measurement or sampling error • By assumption, E(bi)= E(εi)=0, Var(bi)= Var(εi)= , and Cov(bi, εi)=0 yielding (Does this look familiar? ) ,

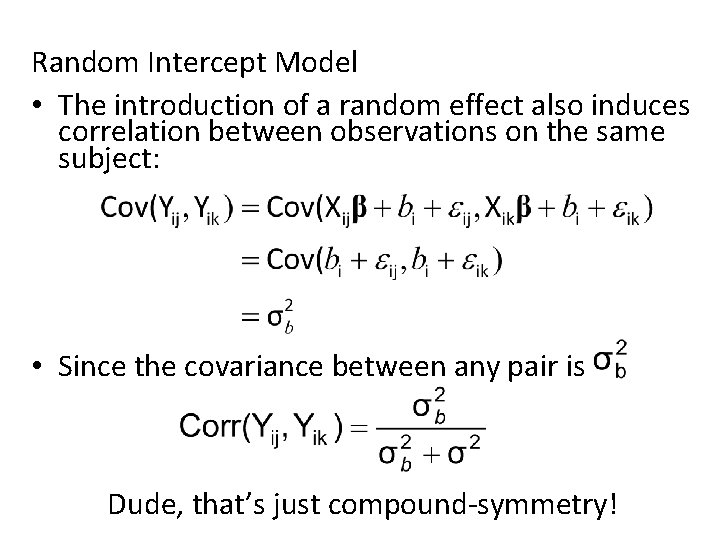

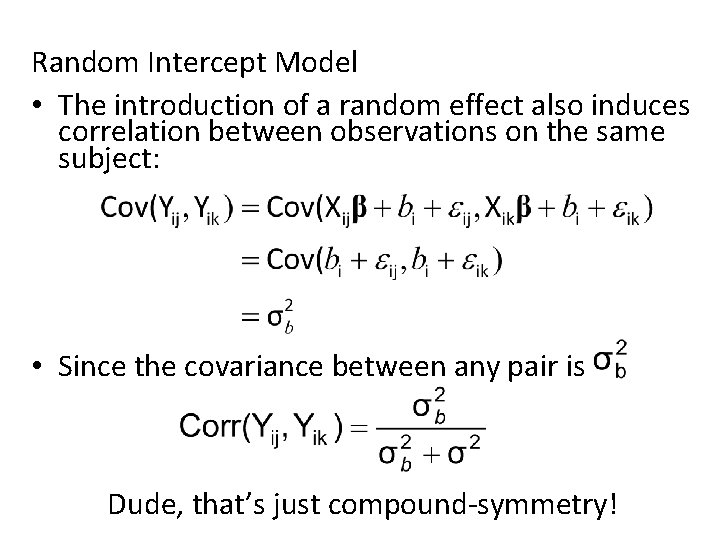

Random Intercept Model • The introduction of a random effect also induces correlation between observations on the same subject: • Since the covariance between any pair is Dude, that’s just compound-symmetry!

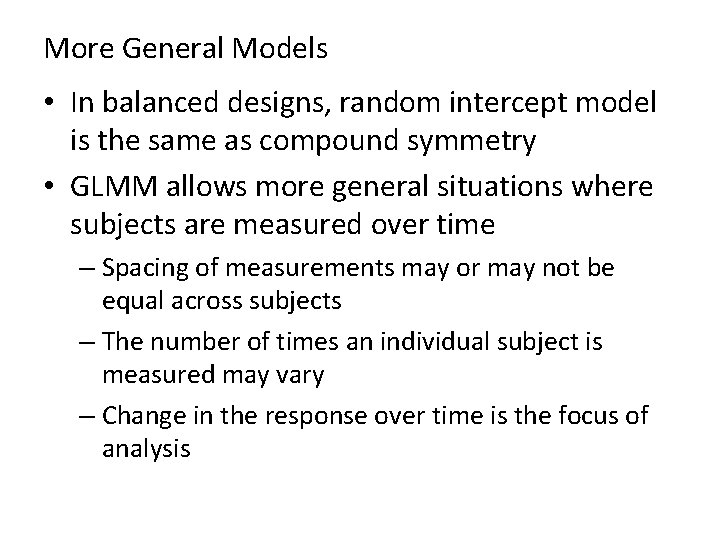

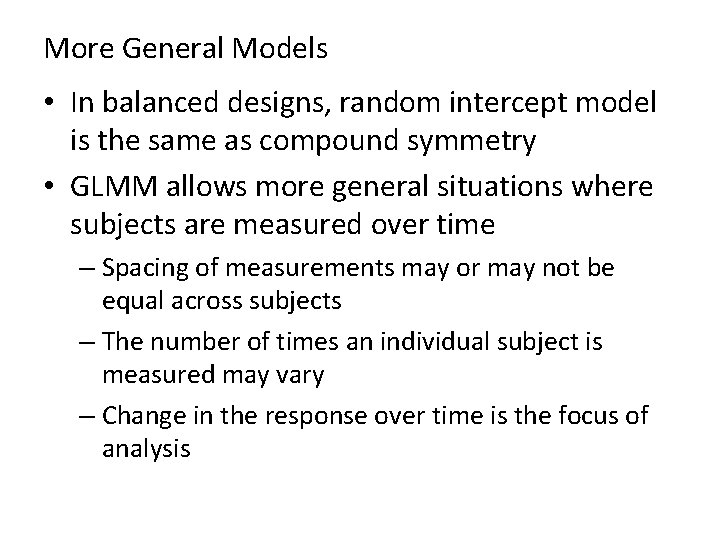

More General Models • In balanced designs, random intercept model is the same as compound symmetry • GLMM allows more general situations where subjects are measured over time – Spacing of measurements may or may not be equal across subjects – The number of times an individual subject is measured may vary – Change in the response over time is the focus of analysis

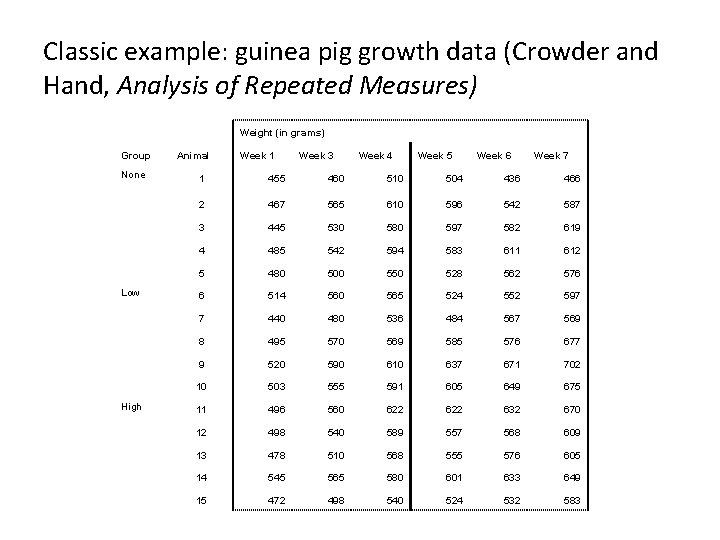

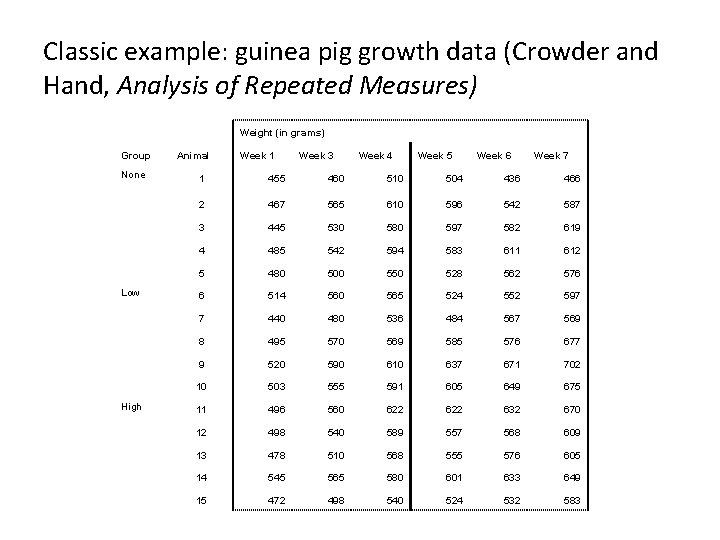

Classic example: guinea pig growth data (Crowder and Hand, Analysis of Repeated Measures) Weight (in grams) Group None Low High Animal Week 1 Week 3 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Week 7 1 455 460 510 504 436 466 2 467 565 610 596 542 587 3 445 530 580 597 582 619 4 485 542 594 583 611 612 5 480 500 550 528 562 576 6 514 560 565 524 552 597 7 440 480 536 484 567 569 8 495 570 569 585 576 677 9 520 590 610 637 671 702 10 503 555 591 605 649 675 11 496 560 622 632 670 12 498 540 589 557 568 609 13 478 510 568 555 576 605 14 545 565 580 601 633 649 15 472 498 540 524 532 583

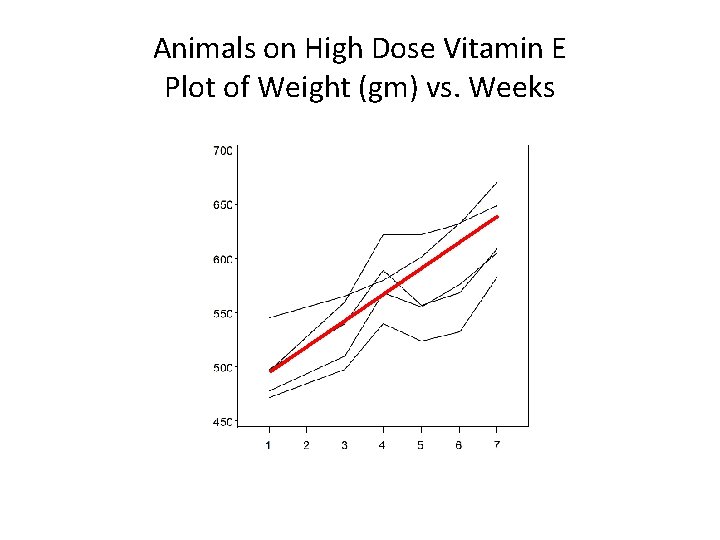

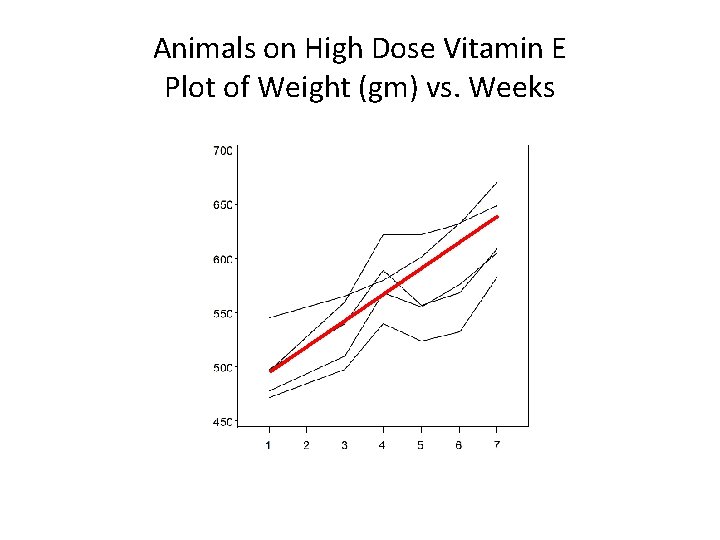

Animals on High Dose Vitamin E Plot of Weight (gm) vs. Weeks

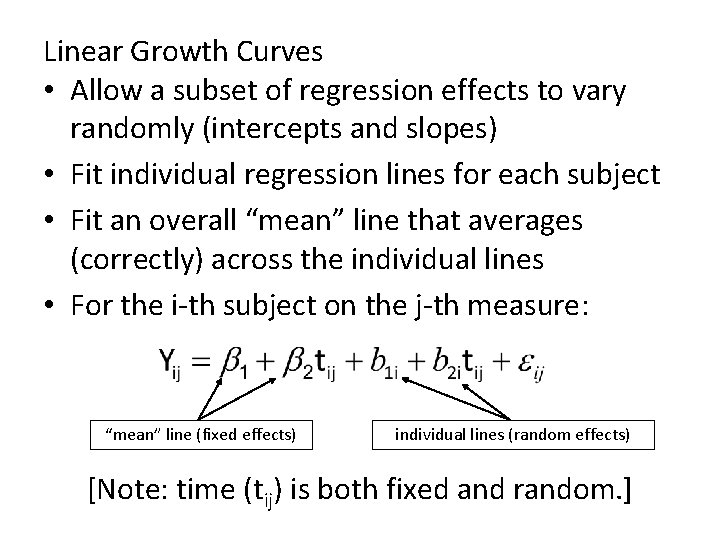

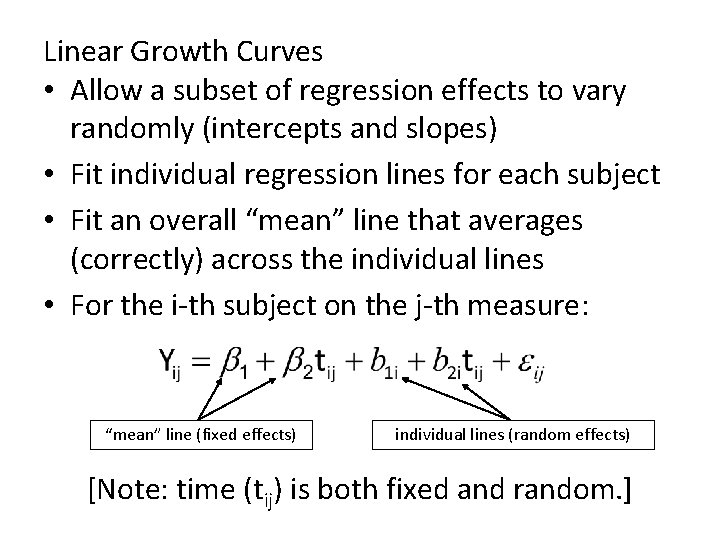

Linear Growth Curves • Allow a subset of regression effects to vary randomly (intercepts and slopes) • Fit individual regression lines for each subject • Fit an overall “mean” line that averages (correctly) across the individual lines • For the i-th subject on the j-th measure: “mean” line (fixed effects) individual lines (random effects) [Note: time (tij) is both fixed and random. ]

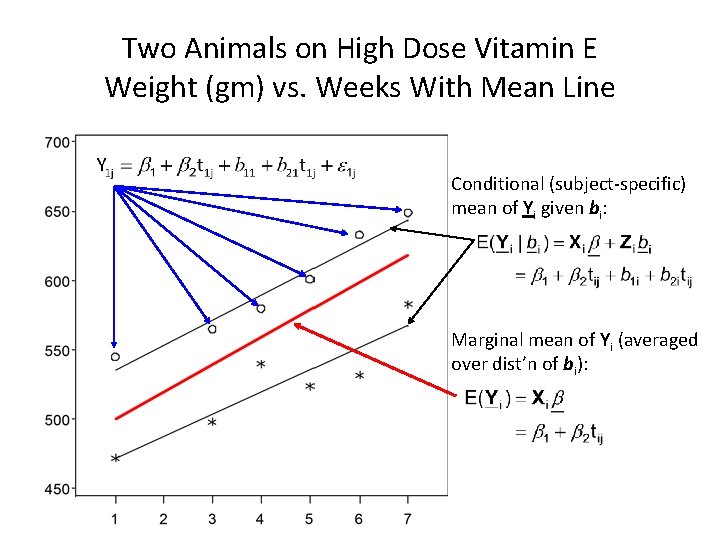

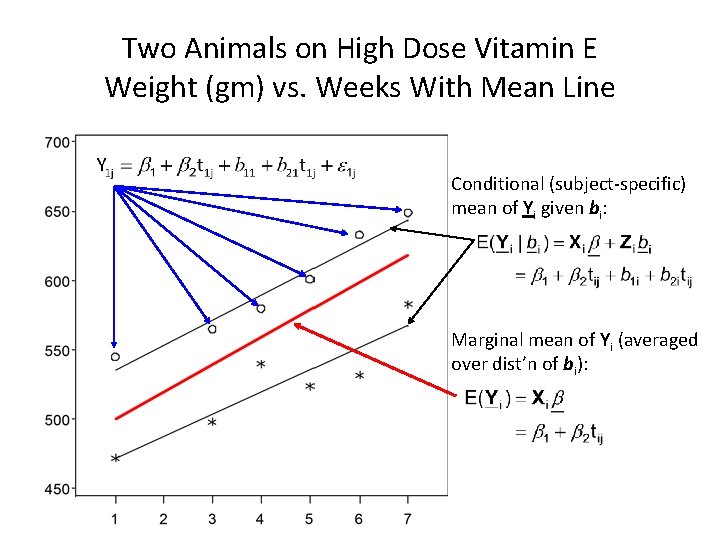

Two Animals on High Dose Vitamin E Weight (gm) vs. Weeks With Mean Line Conditional (subject-specific) mean of Yi given bi: Marginal mean of Yi (averaged over dist’n of bi):

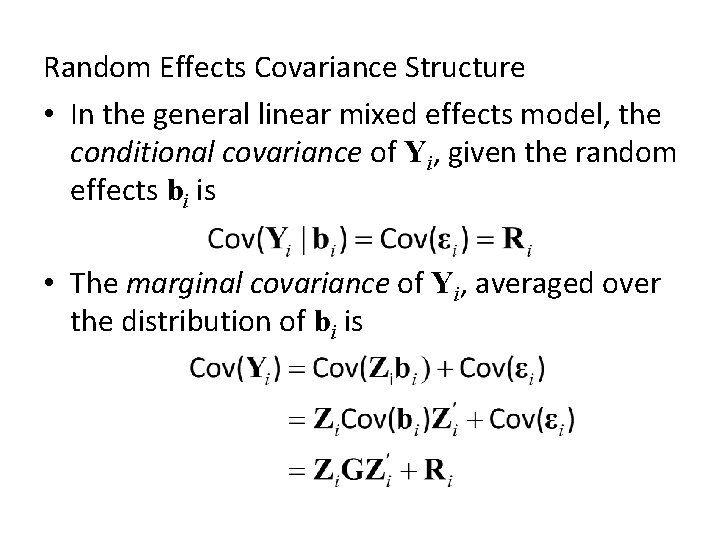

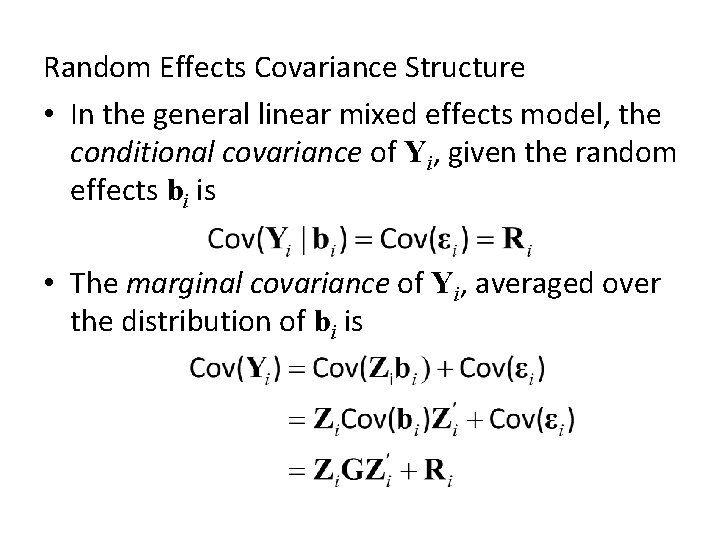

Random Effects Covariance Structure • In the general linear mixed effects model, the conditional covariance of Yi, given the random effects bi is • The marginal covariance of Yi, averaged over the distribution of bi is

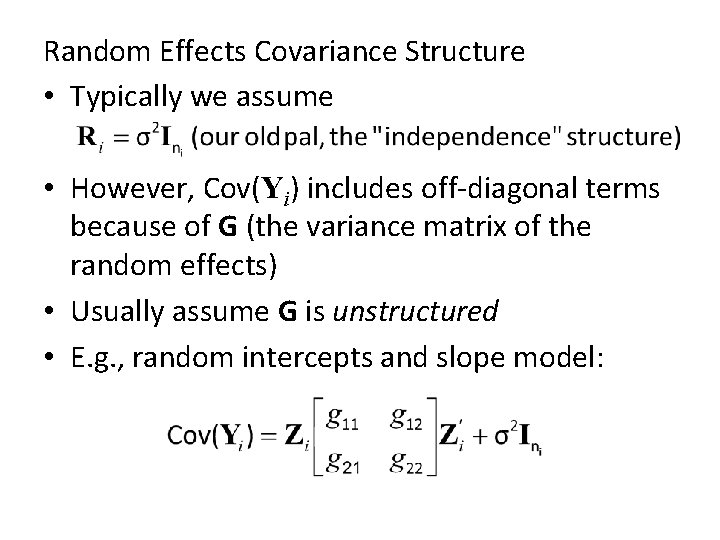

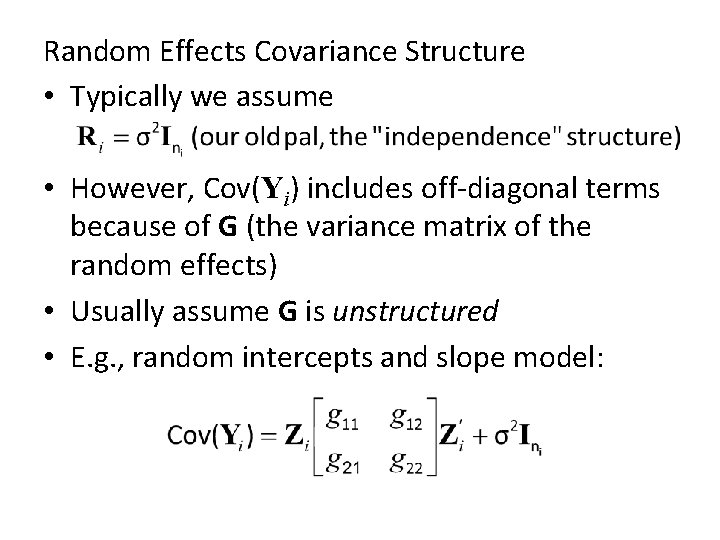

Random Effects Covariance Structure • Typically we assume • However, Cov(Yi) includes off-diagonal terms because of G (the variance matrix of the random effects) • Usually assume G is unstructured • E. g. , random intercepts and slope model:

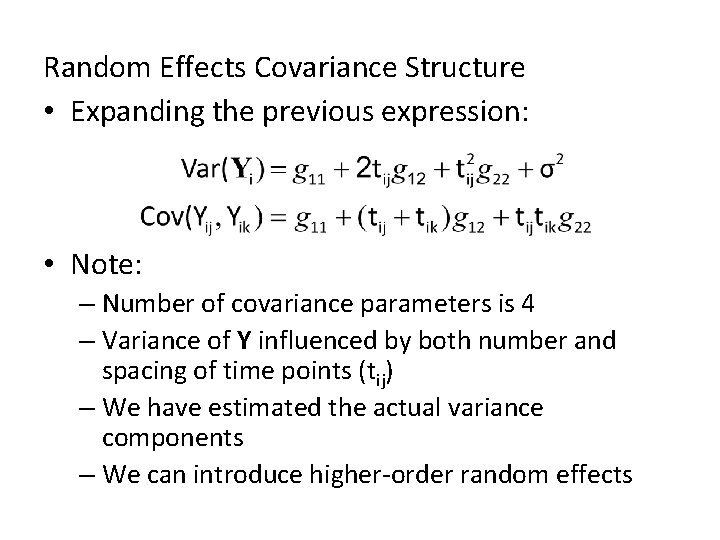

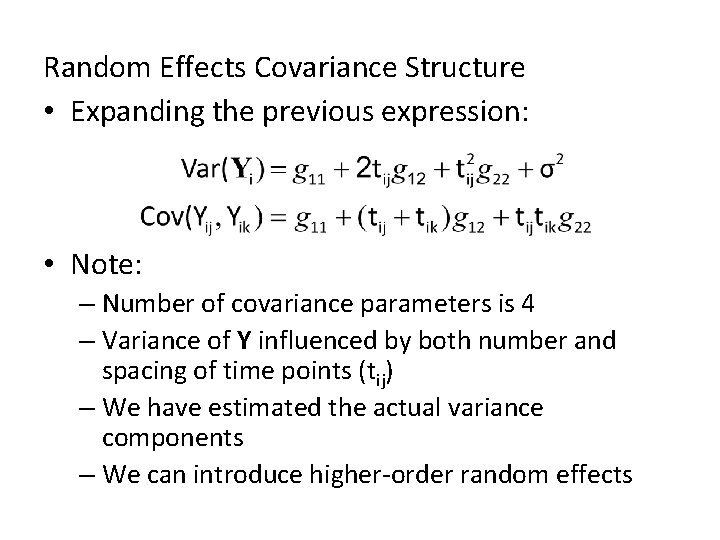

Random Effects Covariance Structure • Expanding the previous expression: • Note: – Number of covariance parameters is 4 – Variance of Y influenced by both number and spacing of time points (tij) – We have estimated the actual variance components – We can introduce higher-order random effects

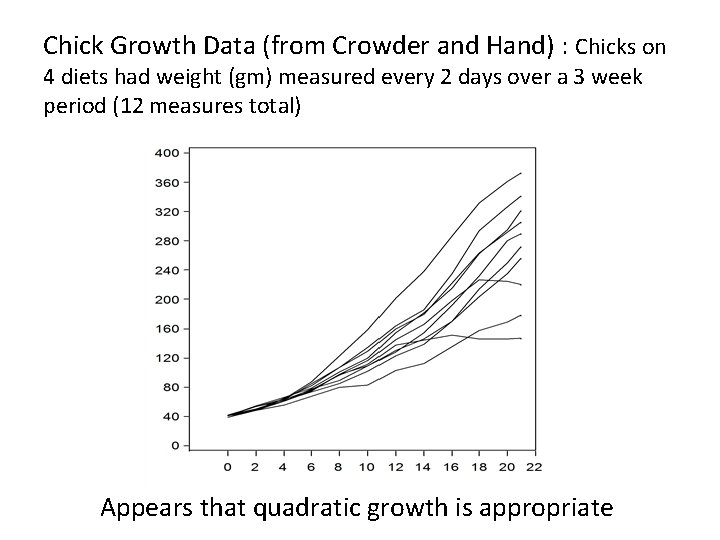

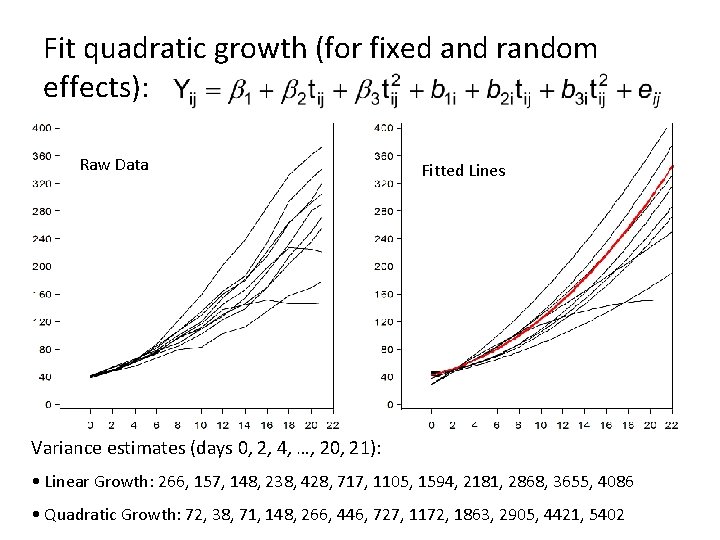

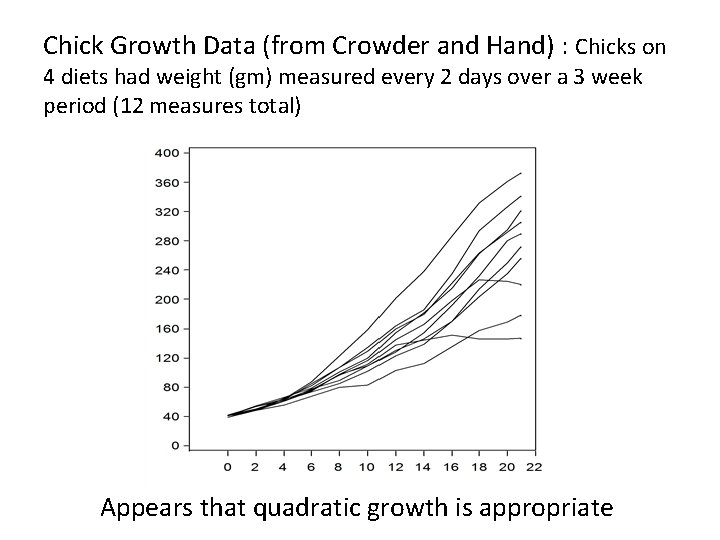

Chick Growth Data (from Crowder and Hand) : Chicks on 4 diets had weight (gm) measured every 2 days over a 3 week period (12 measures total) Appears that quadratic growth is appropriate

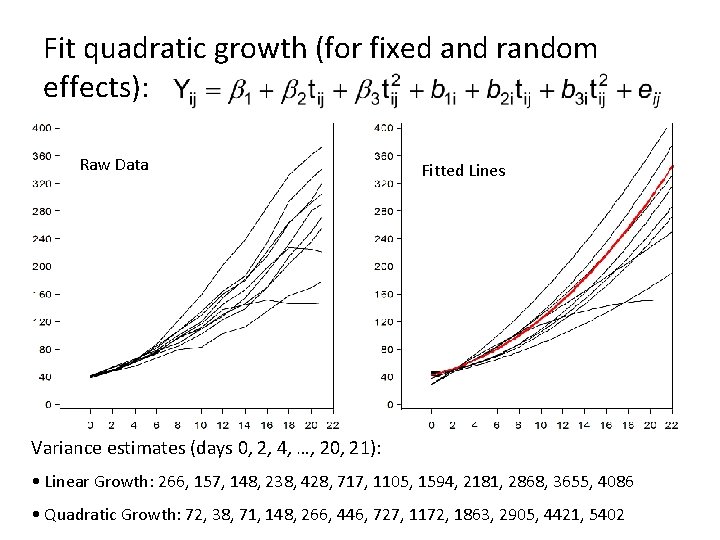

Fit quadratic growth (for fixed and random effects): Raw Data Fitted Lines Variance estimates (days 0, 2, 4, …, 20, 21): • Linear Growth: 266, 157, 148, 238, 428, 717, 1105, 1594, 2181, 2868, 3655, 4086 • Quadratic Growth: 72, 38, 71, 148, 266, 446, 727, 1172, 1863, 2905, 4421, 5402

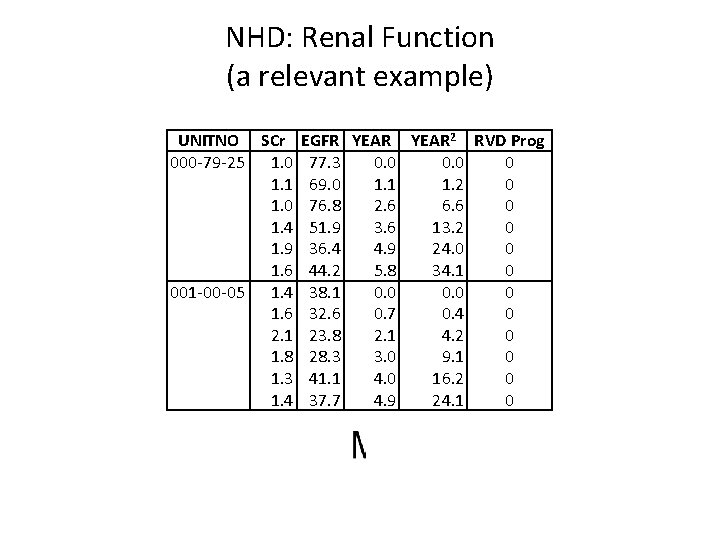

NHD: Renal Function (a relevant example) UNITNO SCr 000 -79 -25 1. 0 1. 1 1. 0 1. 4 1. 9 1. 6 001 -00 -05 1. 4 1. 6 2. 1 1. 8 1. 3 1. 4 EGFR YEAR 2 RVD Prog 77. 3 0. 0 0 69. 0 1. 1 1. 2 0 76. 8 2. 6 6. 6 0 51. 9 3. 6 13. 2 0 36. 4 4. 9 24. 0 0 44. 2 5. 8 34. 1 0 38. 1 0. 0 0 32. 6 0. 7 0. 4 0 23. 8 2. 1 4. 2 0 28. 3 3. 0 9. 1 0 41. 1 4. 0 16. 2 0 37. 7 4. 9 24. 1 0

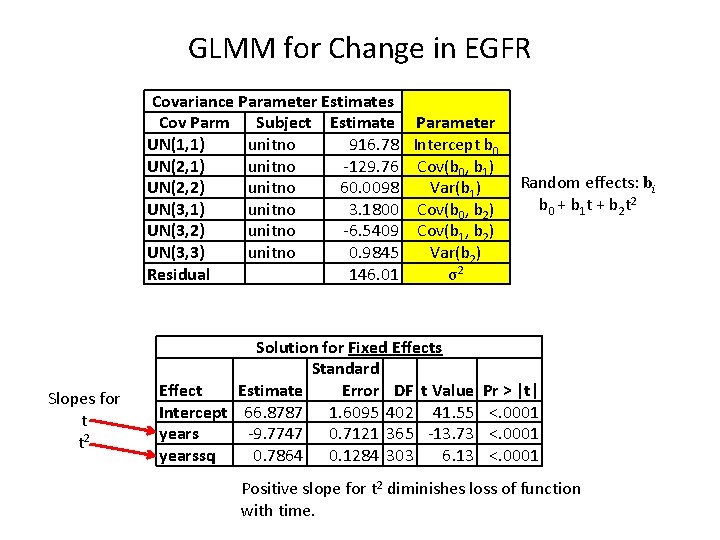

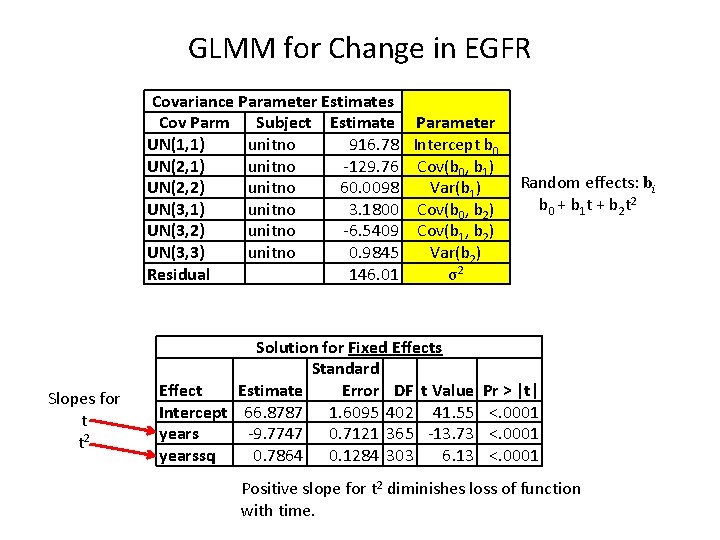

GLMM for Change in EGFR Covariance Parameter Estimates Cov Parm Subject Estimate Parameter UN(1, 1) unitno 916. 78 Intercept b 0 UN(2, 1) unitno -129. 76 Cov(b 0, b 1) UN(2, 2) unitno 60. 0098 Var(b 1) UN(3, 1) unitno 3. 1800 Cov(b 0, b 2) UN(3, 2) unitno -6. 5409 Cov(b 1, b 2) UN(3, 3) unitno 0. 9845 Var(b 2) Residual 146. 01 σ2 Slopes for t t 2 Solution for Fixed Effects Standard Effect Estimate Error DF t Value Intercept 66. 8787 1. 6095 402 41. 55 years -9. 7747 0. 7121 365 -13. 73 yearssq 0. 7864 0. 1284 303 6. 13 Random effects: bi b 0 + b 1 t + b 2 t 2 Pr > |t| <. 0001 Positive slope for t 2 diminishes loss of function with time.

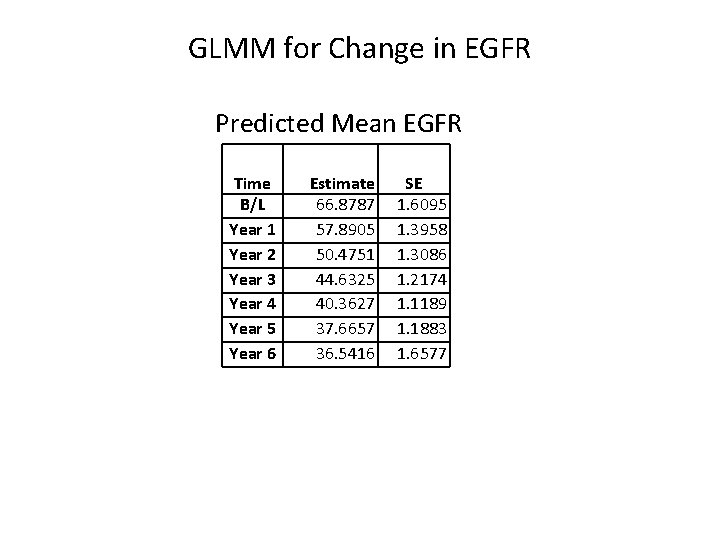

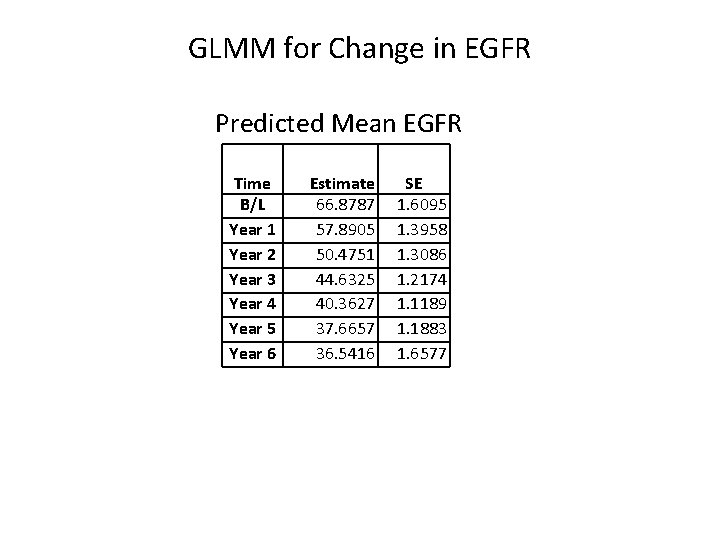

GLMM for Change in EGFR Predicted Mean EGFR Time B/L Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5 Year 6 Estimate 66. 8787 57. 8905 50. 4751 44. 6325 40. 3627 37. 6657 36. 5416 SE 1. 6095 1. 3958 1. 3086 1. 2174 1. 1189 1. 1883 1. 6577

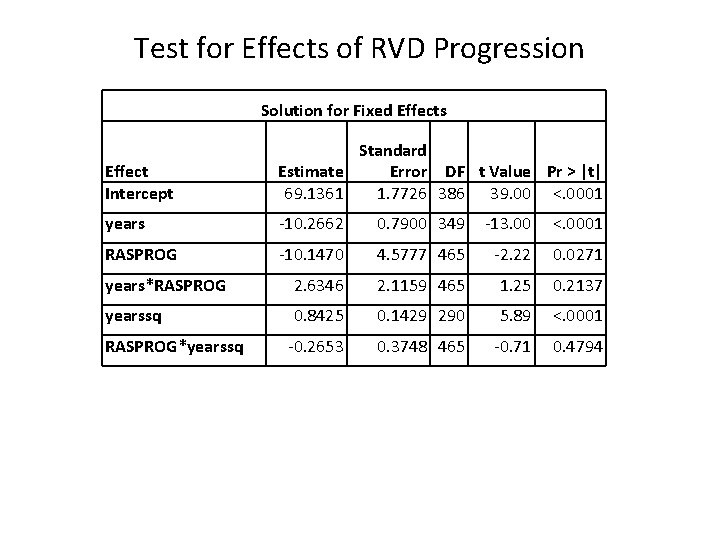

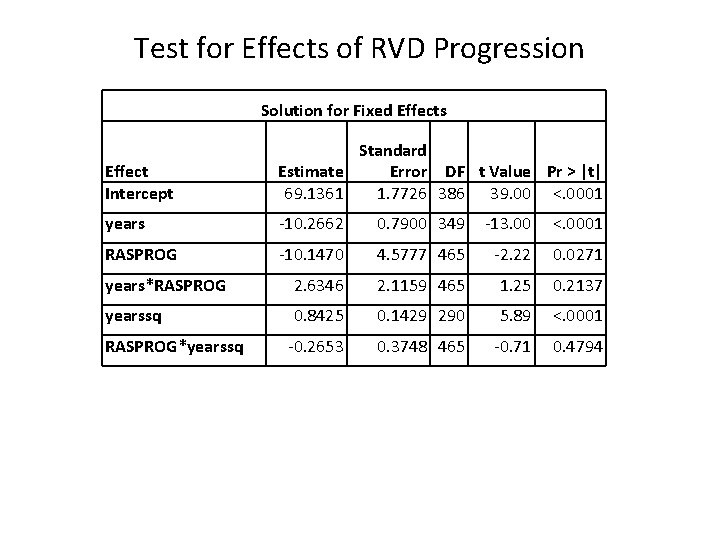

Test for Effects of RVD Progression Solution for Fixed Effects Effect Intercept Standard Estimate Error DF t Value Pr > |t| 69. 1361 1. 7726 386 39. 00 <. 0001 years -10. 2662 0. 7900 349 -13. 00 <. 0001 RASPROG -10. 1470 4. 5777 465 -2. 22 0. 0271 years*RASPROG 2. 6346 2. 1159 465 1. 25 0. 2137 yearssq 0. 8425 0. 1429 290 5. 89 <. 0001 -0. 2653 0. 3748 465 -0. 71 0. 4794 RASPROG*yearssq

Advantages of the GLMM • A wide variety of covariance structures can be fit (and compared) • It is possible to allow for different covariance matrices by group (do not have to pool variance and assume homoscedasticity) • Balanced data is not necessary • Covariates, even time-varying covariates may be incorporated into the model • Many different types of questions may be addressed

Summary: Advantages of Longitudinal Study Design • Permits the discovery of individual characteristics that can explain inter-individual differences in changes in health outcomes over time • Fundamental objective - to measure withinindividual changes • Also of interest – to determine whether the within-individual changes in the response are related to selected covariates