Model Resolution and ElevatedSlantwise Convection CSTAR Workshop 6

- Slides: 25

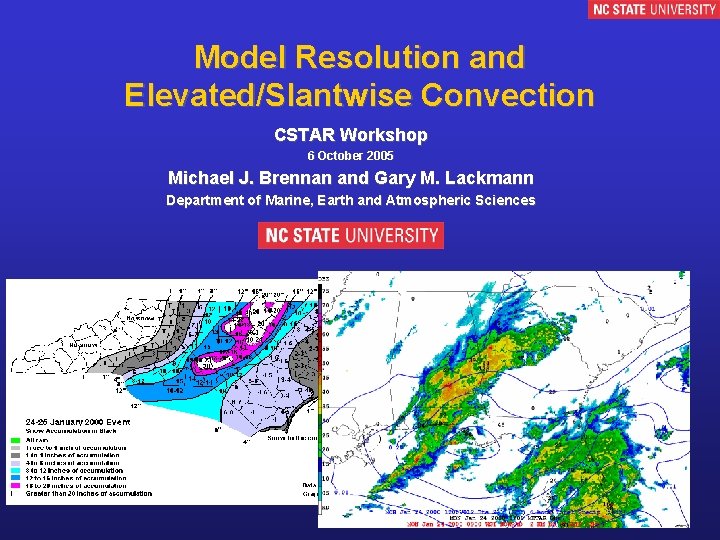

Model Resolution and Elevated/Slantwise Convection CSTAR Workshop 6 October 2005 Michael J. Brennan and Gary M. Lackmann Department of Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences 1

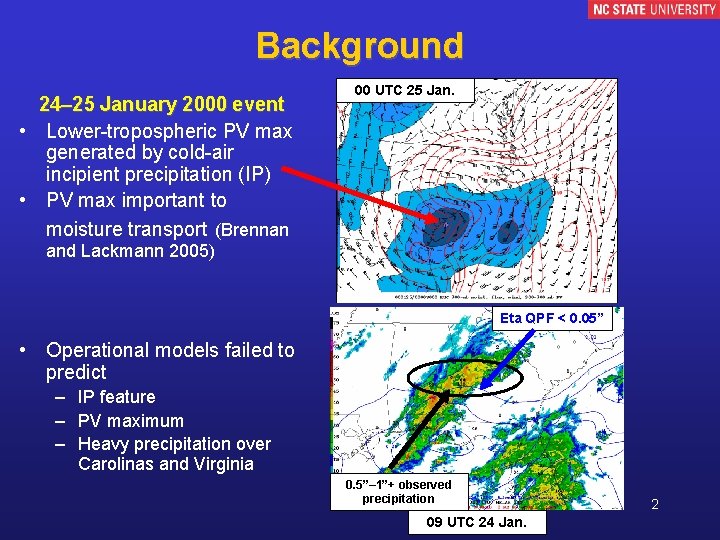

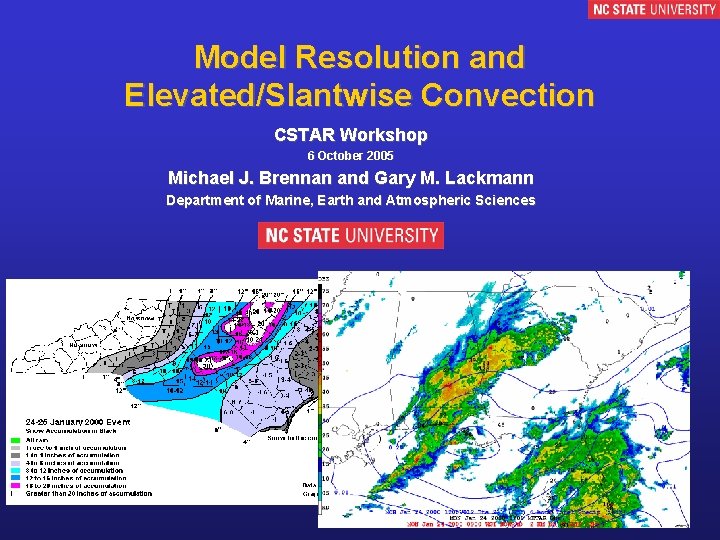

Background 24– 25 January 2000 event • Lower-tropospheric PV max generated by cold-air incipient precipitation (IP) • PV max important to moisture transport (Brennan 00 UTC 25 Jan. and Lackmann 2005) Eta QPF < 0. 05” • Operational models failed to predict – IP feature – PV maximum – Heavy precipitation over Carolinas and Virginia 0. 5”– 1”+ observed precipitation 09 UTC 24 Jan. 2

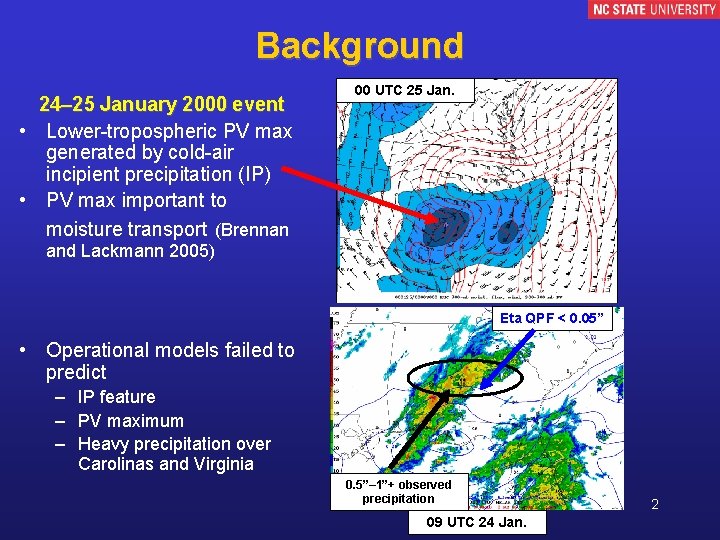

Motivation/Methodology Motivation • Why were operational models unable to predict formation of critical IP feature? – Formed over relatively data-rich region within first 12 h of model cycle Methodology • Observational case study – • • Examine forcing, moisture, instability associated with IP formation Evaluate short-term operational model forecasts Test sensitivity of IP formation to model grid spacing 3

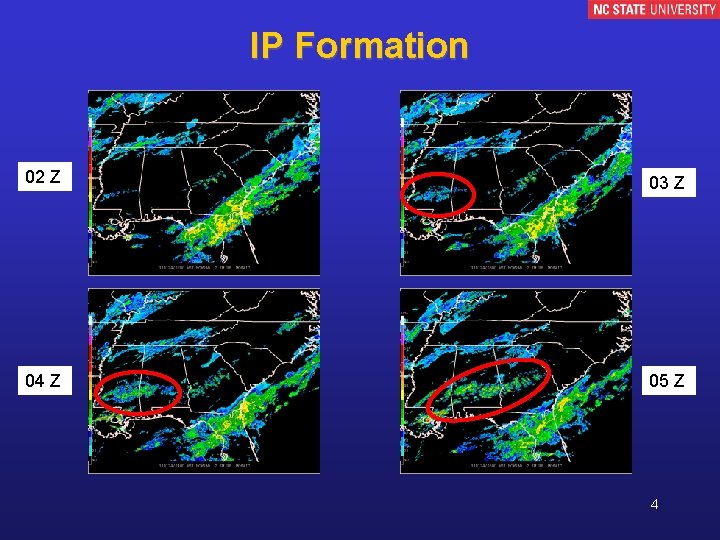

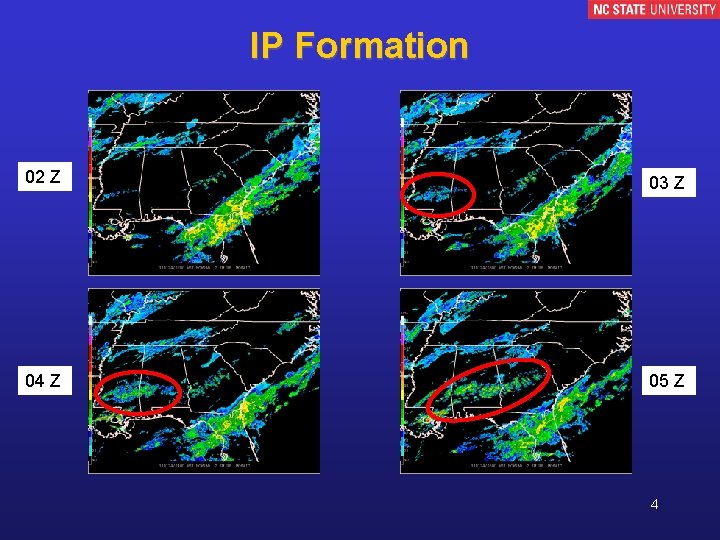

IP Formation 02 Z 03 Z 04 Z 05 Z 4

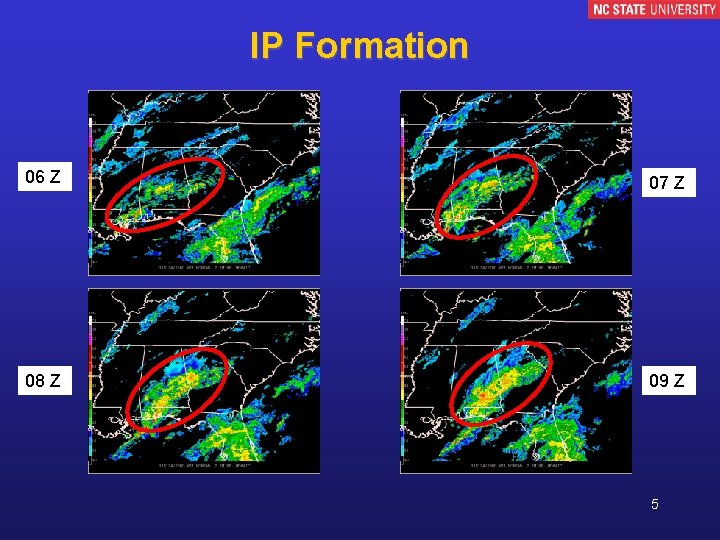

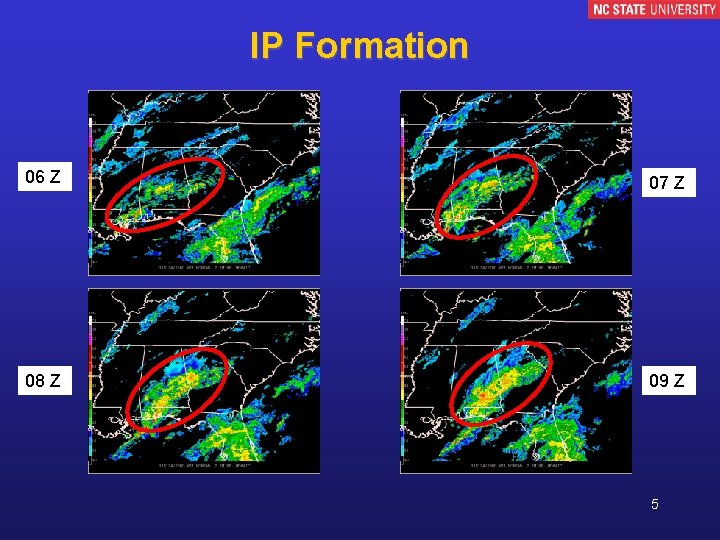

IP Formation 06 Z 07 Z 08 Z 09 Z 5

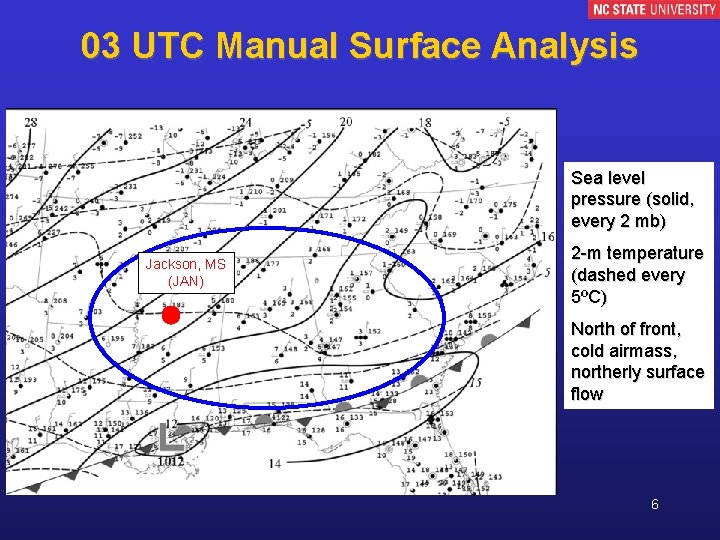

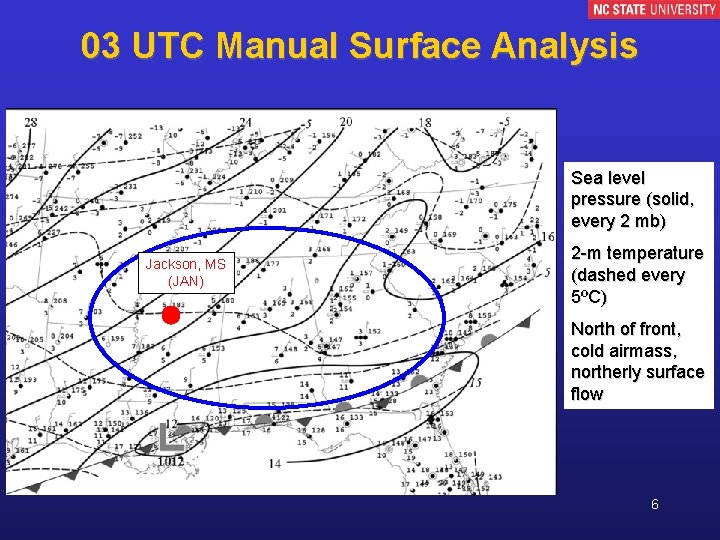

03 UTC Manual Surface Analysis Sea level pressure (solid, every 2 mb) Jackson, MS (JAN) 2 -m temperature (dashed every 5ºC) North of front, cold airmass, northerly surface flow 6

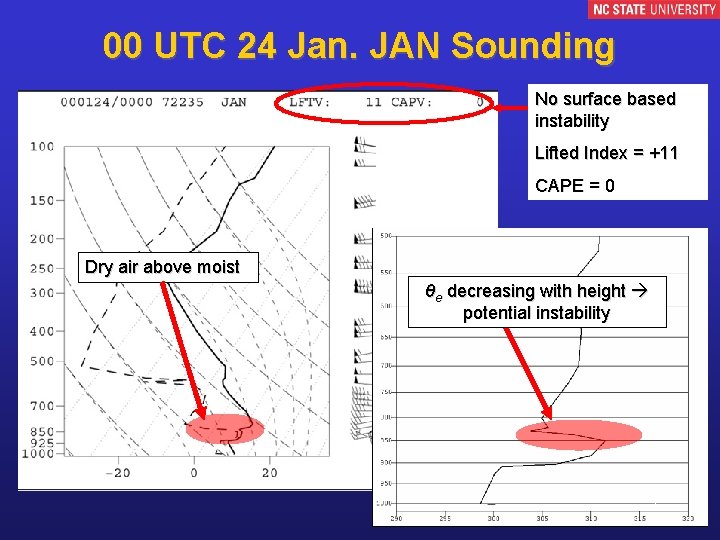

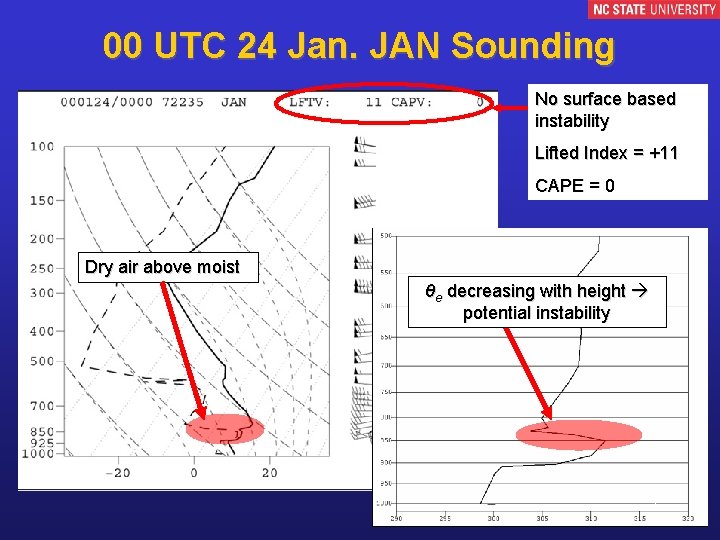

00 UTC 24 Jan. JAN Sounding No surface based instability Lifted Index = +11 CAPE = 0 Dry air above moist θe decreasing with height potential instability 7

Elevated Convection • Parcels become positively buoyant above the surface layer – Surface-based parcels become buoyant and ride over frontal inversion (Colman 1990 b) – Buoyant parcels originate above stable surface layer as frontogenetical forcing lifts parcels to LCL (Martin 1998) • Most cold season thunderstorm activity in CONUS is elevated (Colman 1990 a) – Usually occurs northeast of surface cyclone above warm-frontal inversion and extremely stable airmass (Colman 1990 a) 8

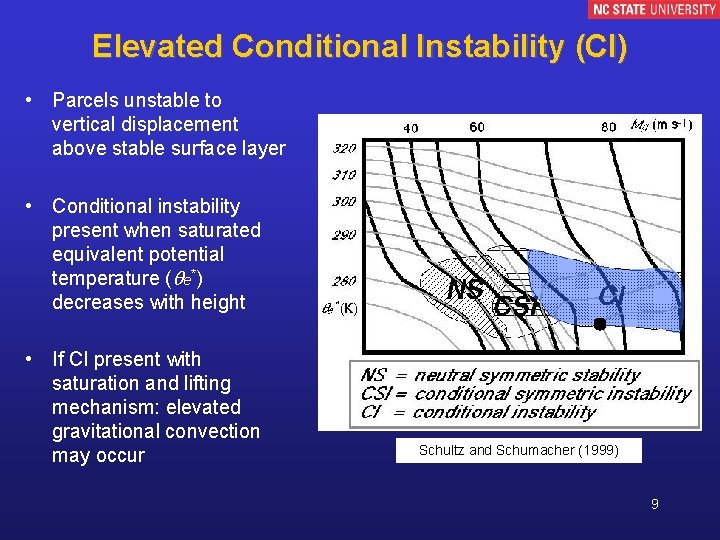

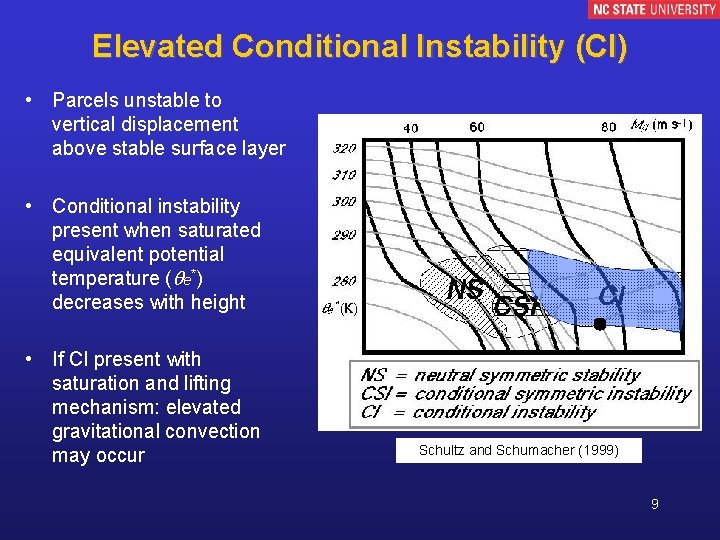

Elevated Conditional Instability (CI) • Parcels unstable to vertical displacement above stable surface layer • Conditional instability present when saturated equivalent potential temperature ( e*) decreases with height • If CI present with saturation and lifting mechanism: elevated gravitational convection may occur Schultz and Schumacher (1999) 9

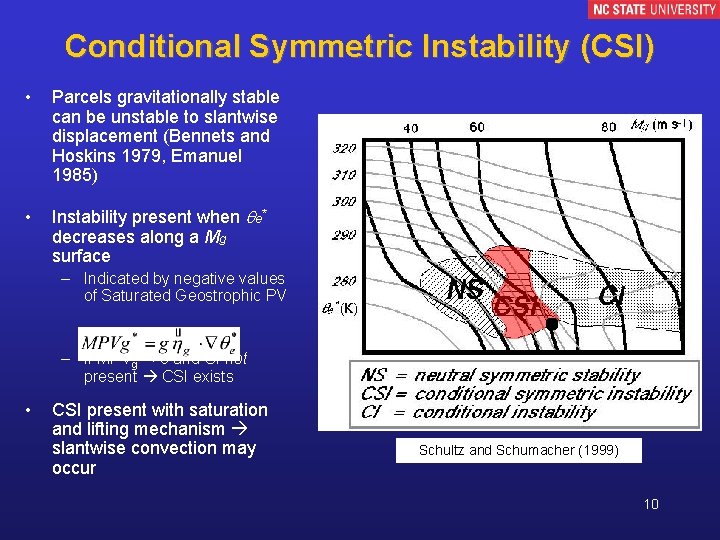

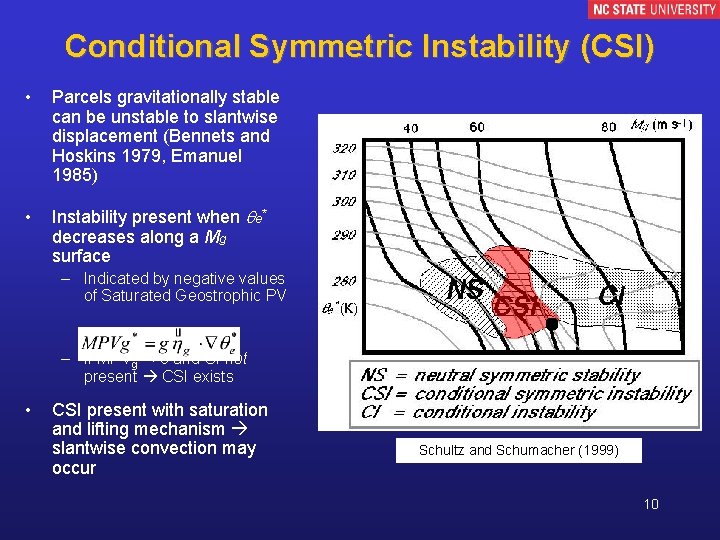

Conditional Symmetric Instability (CSI) • Parcels gravitationally stable can be unstable to slantwise displacement (Bennets and Hoskins 1979, Emanuel 1985) • Instability present when e* decreases along a Mg surface – Indicated by negative values of Saturated Geostrophic PV – If MPVg* < 0 and CI not present CSI exists • CSI present with saturation and lifting mechanism slantwise convection may occur Schultz and Schumacher (1999) 10

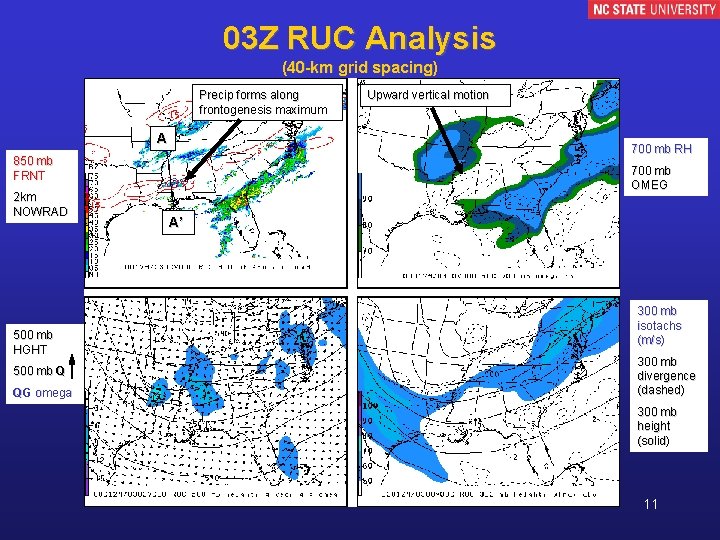

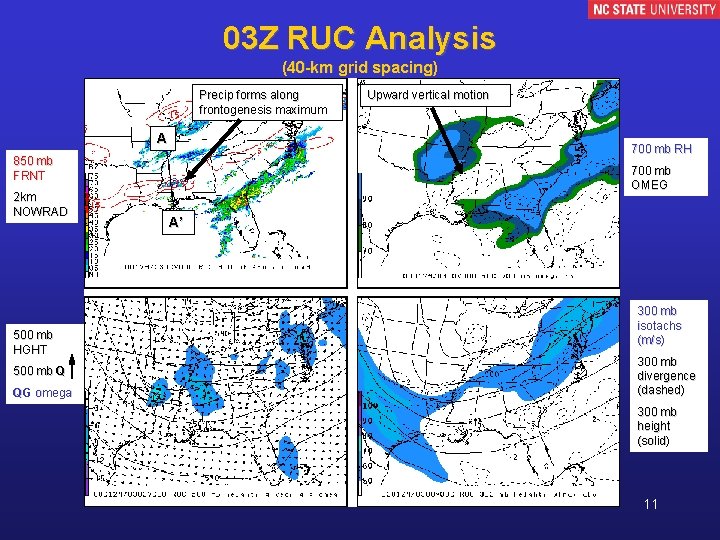

03 Z RUC Analysis (40 -km grid spacing) Precip forms along frontogenesis maximum A 700 mb RH 850 mb FRNT 2 km NOWRAD 500 mb HGHT 500 mb Q QG omega Upward vertical motion 700 mb OMEG A’ 300 mb isotachs (m/s) 300 mb divergence (dashed) 300 mb height (solid) 11

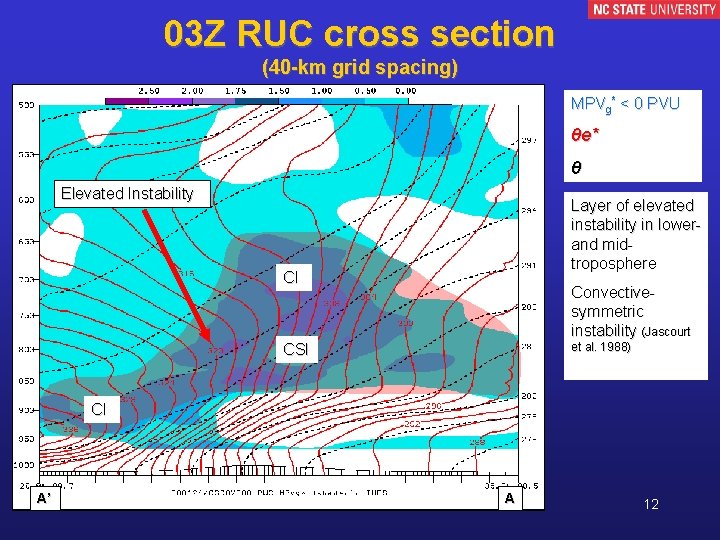

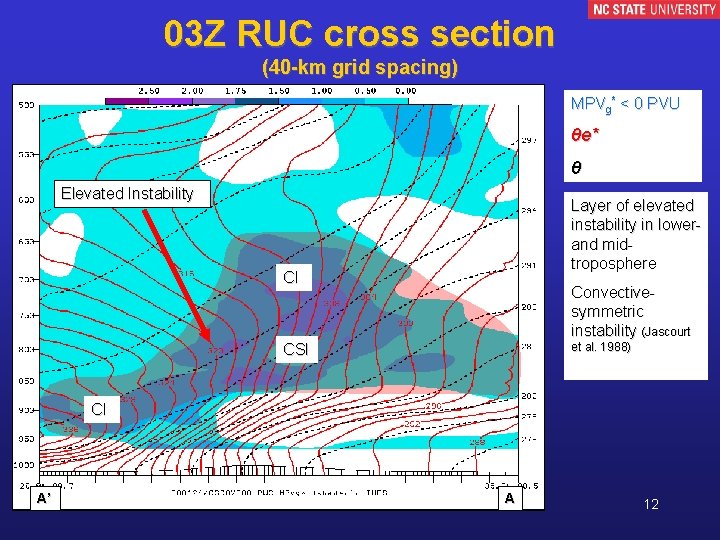

03 Z RUC cross section (40 -km grid spacing) MPVg* < 0 PVU θe* θ Elevated Instability Layer of elevated instability in lowerand midtroposphere CI Convectivesymmetric instability (Jascourt et al. 1988) CSI CI A’ A 12

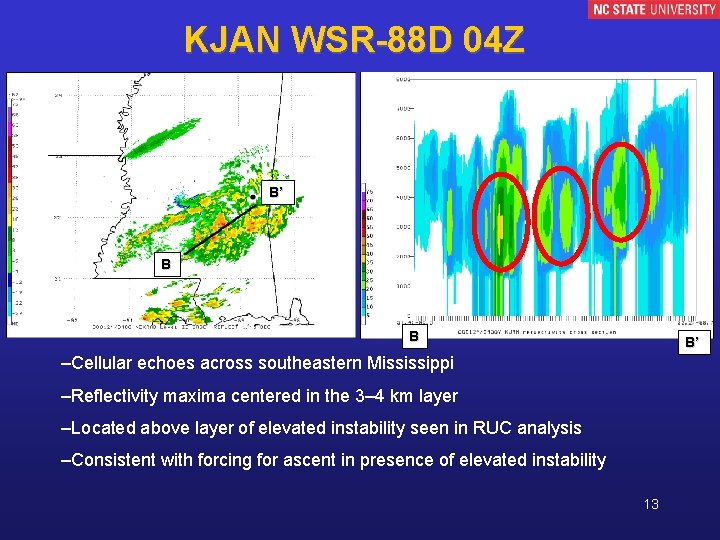

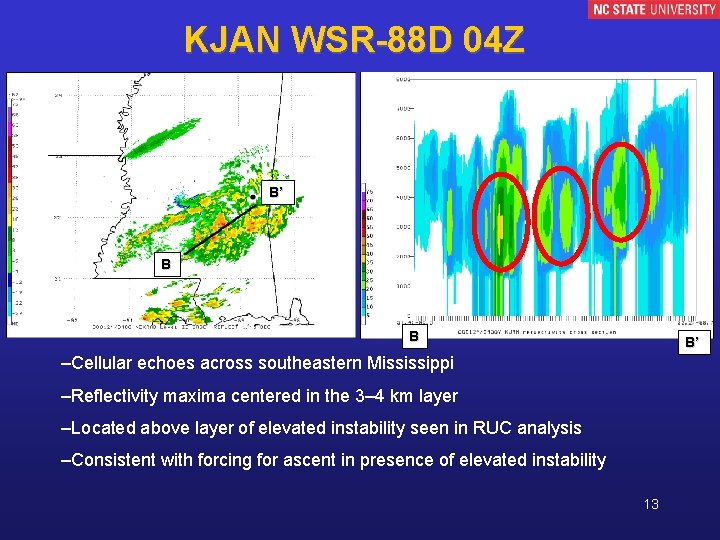

KJAN WSR-88 D 04 Z B’ B B B’ –Cellular echoes across southeastern Mississippi –Reflectivity maxima centered in the 3– 4 km layer –Located above layer of elevated instability seen in RUC analysis –Consistent with forcing for ascent in presence of elevated instability 13

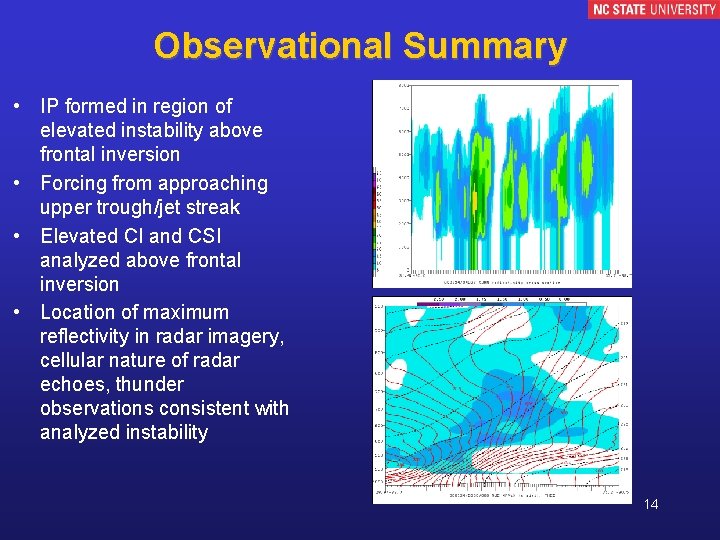

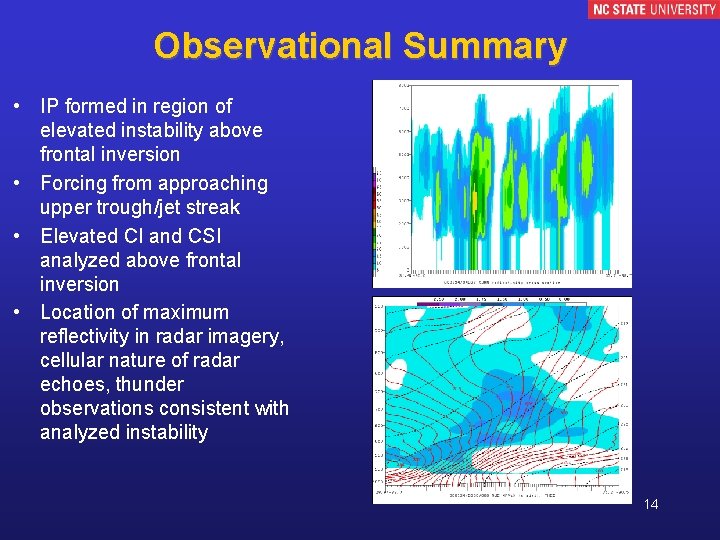

Observational Summary • IP formed in region of elevated instability above frontal inversion • Forcing from approaching upper trough/jet streak • Elevated CI and CSI analyzed above frontal inversion • Location of maximum reflectivity in radar imagery, cellular nature of radar echoes, thunder observations consistent with analyzed instability 14

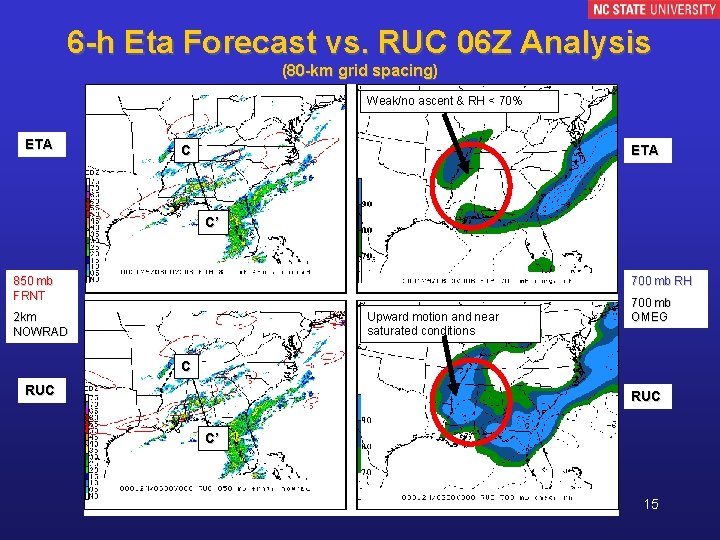

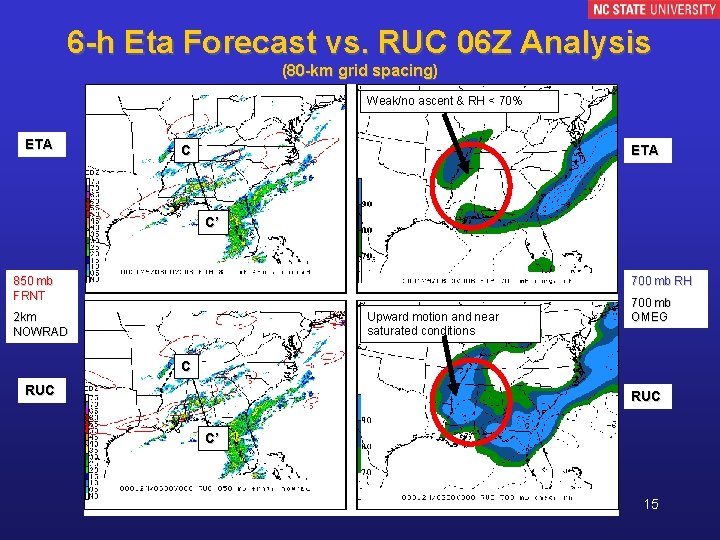

6 -h Eta Forecast vs. RUC 06 Z Analysis (80 -km grid spacing) Weak/no ascent & RH < 70% ETA C’ 850 mb FRNT 700 mb RH Upward motion and near saturated conditions 2 km NOWRAD 700 mb OMEG C RUC C’ 15

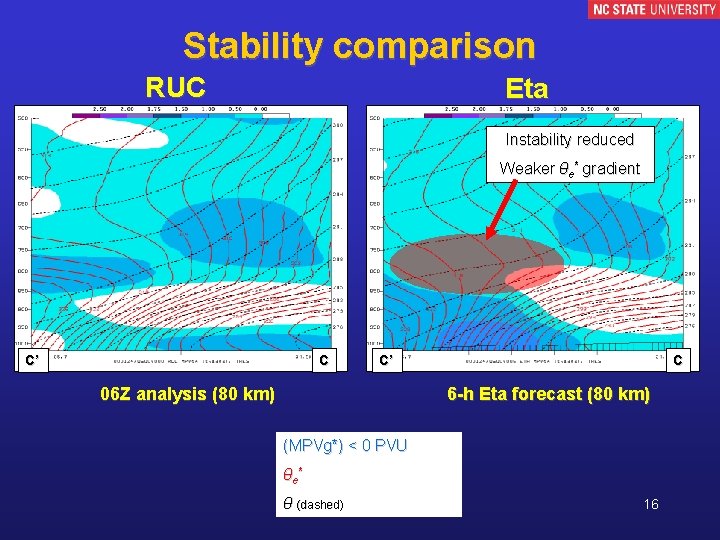

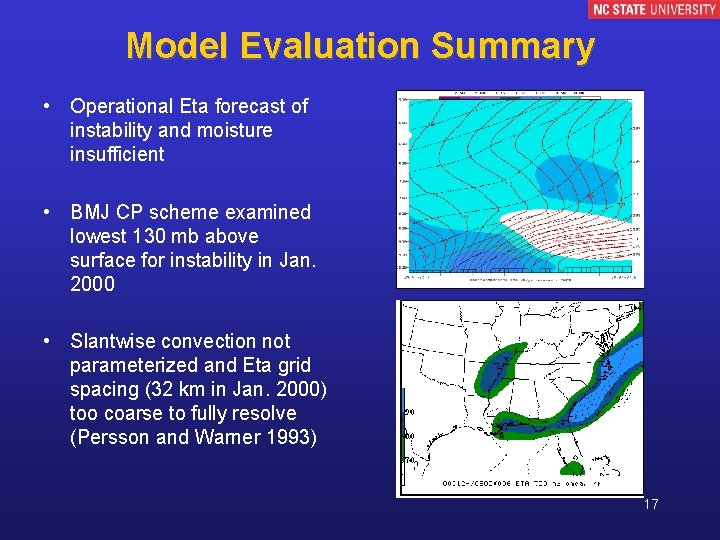

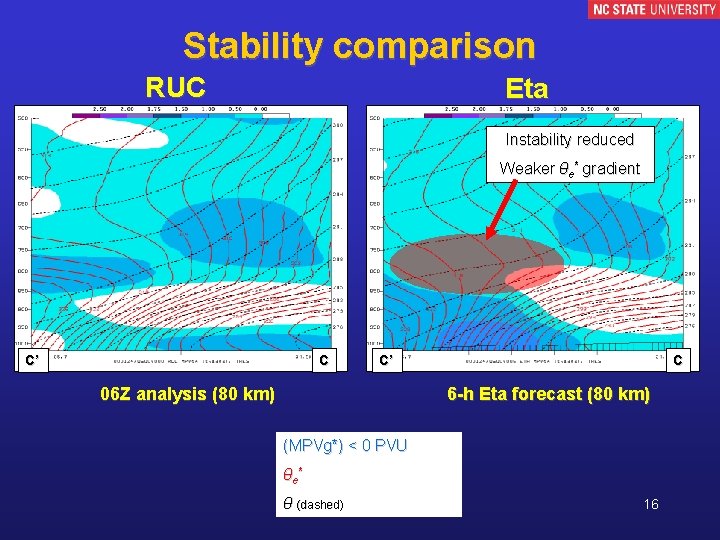

Stability comparison RUC Eta Instability reduced Weaker θe* gradient C’ C C’ 06 Z analysis (80 km) C 6 -h Eta forecast (80 km) (MPVg*) < 0 PVU θ e* θ (dashed) 16

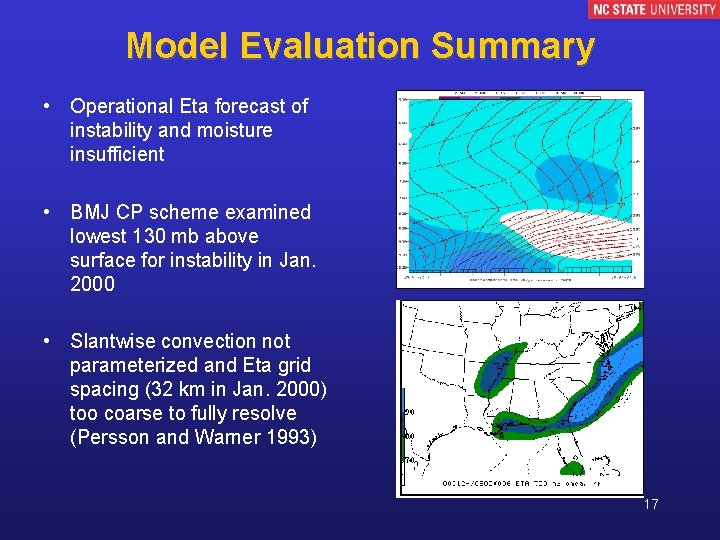

Model Evaluation Summary • Operational Eta forecast of instability and moisture insufficient • BMJ CP scheme examined lowest 130 mb above surface for instability in Jan. 2000 • Slantwise convection not parameterized and Eta grid spacing (32 km in Jan. 2000) too coarse to fully resolve (Persson and Warner 1993) 17

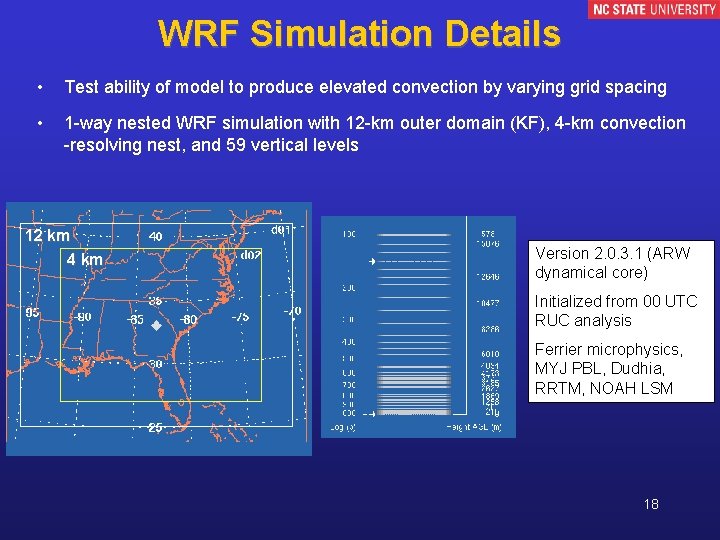

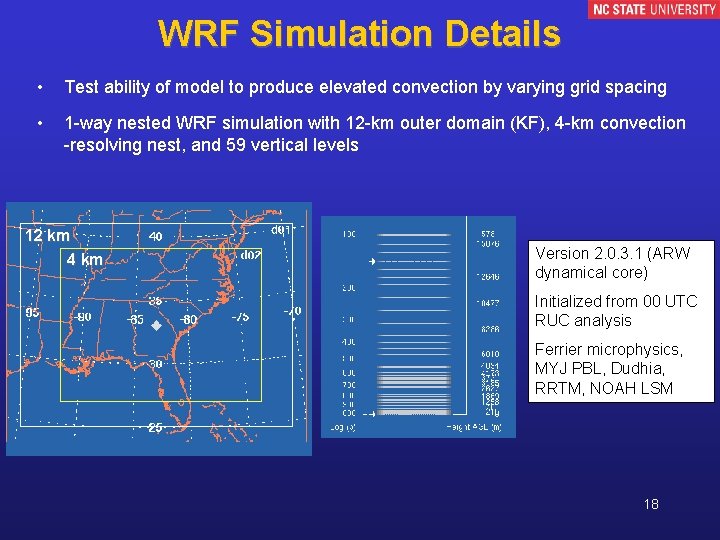

WRF Simulation Details • Test ability of model to produce elevated convection by varying grid spacing • 1 -way nested WRF simulation with 12 -km outer domain (KF), 4 -km convection -resolving nest, and 59 vertical levels 12 km 4 km Version 2. 0. 3. 1 (ARW dynamical core) Initialized from 00 UTC RUC analysis Ferrier microphysics, MYJ PBL, Dudhia, RRTM, NOAH LSM 18

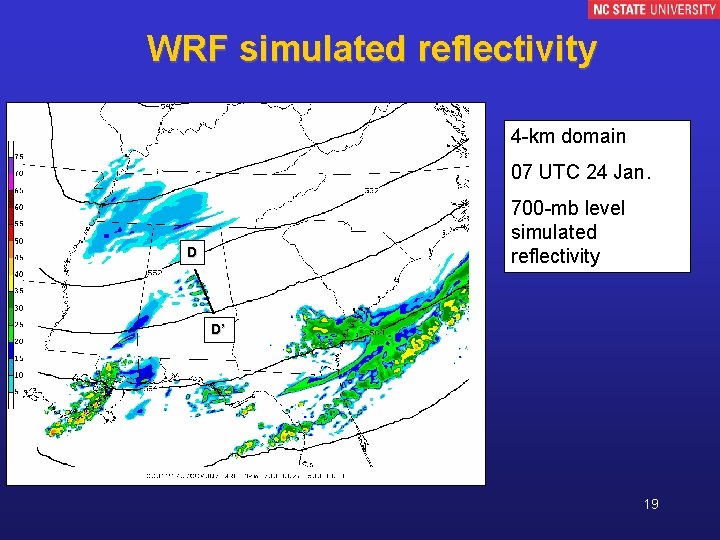

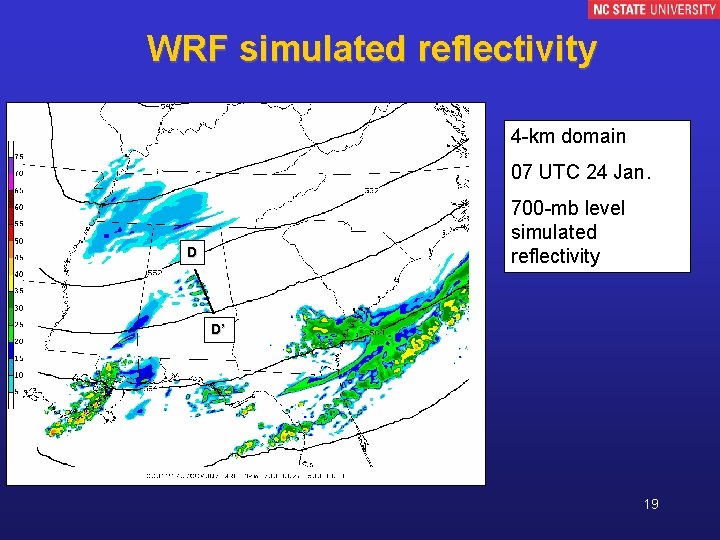

WRF simulated reflectivity 4 -km domain 07 UTC 24 Jan. 700 -mb level simulated reflectivity D D’ 19

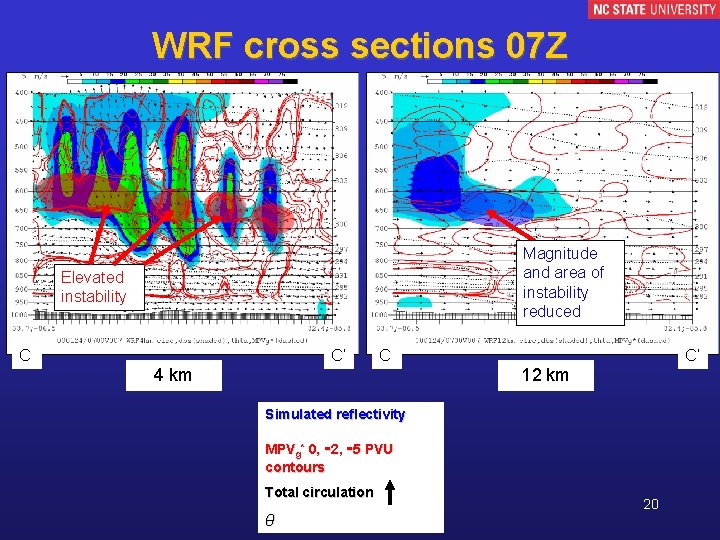

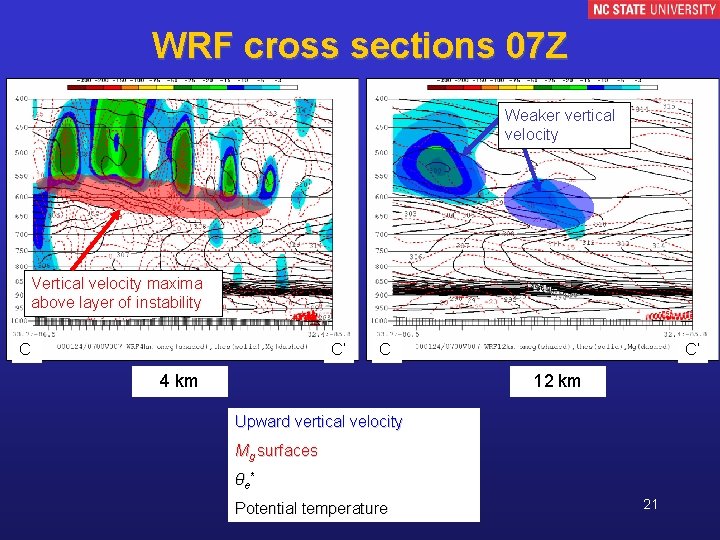

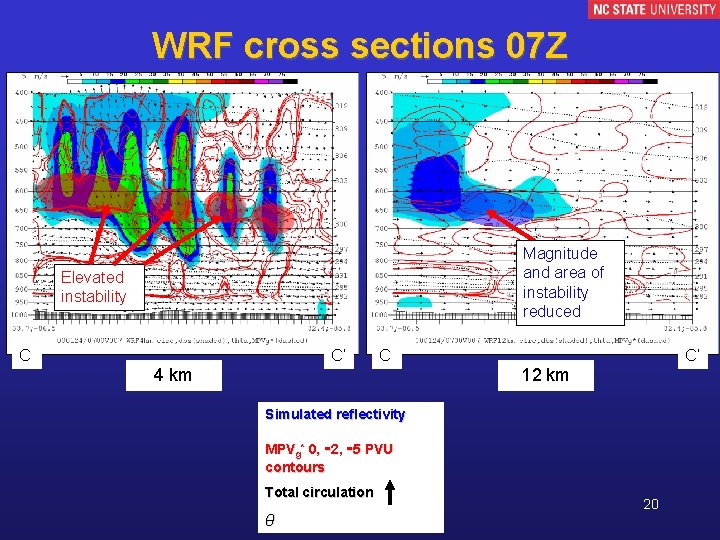

WRF cross sections 07 Z Magnitude and area of instability reduced Elevated instability C C’ C 4 km C’ 12 km Simulated reflectivity MPVg* 0, -2, -5 PVU contours Total circulation θ 20

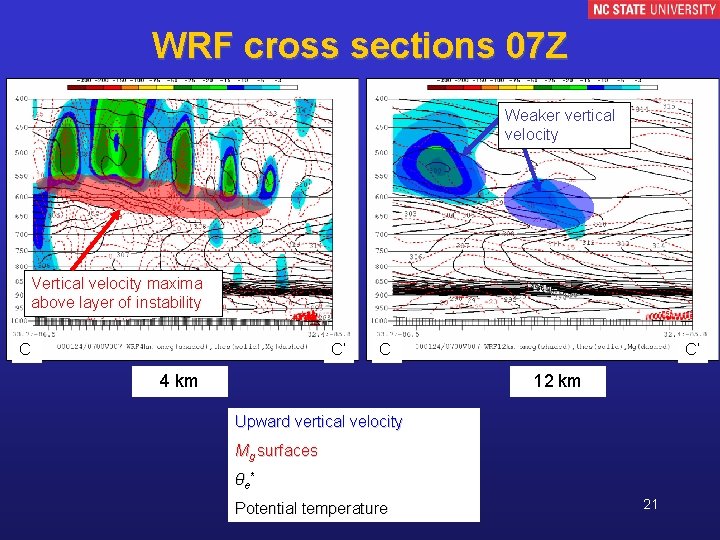

WRF cross sections 07 Z Weaker vertical velocity Vertical velocity maxima above layer of instability C C’ C 4 km C’ 12 km Upward vertical velocity Mg surfaces θ e* Potential temperature 21

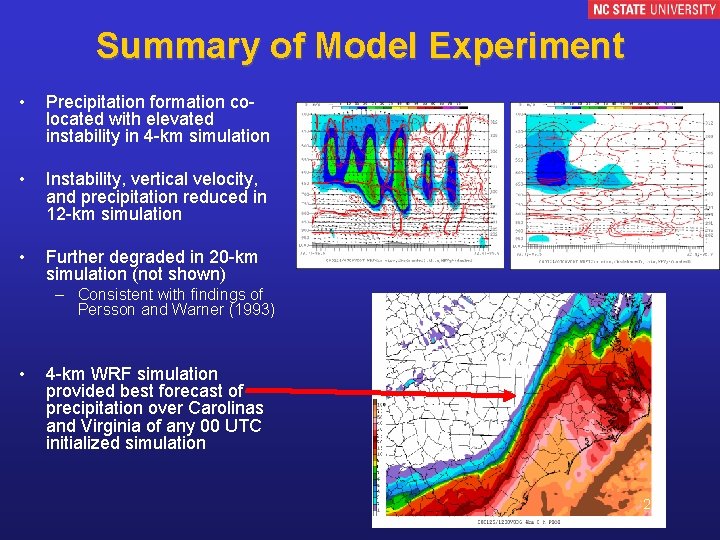

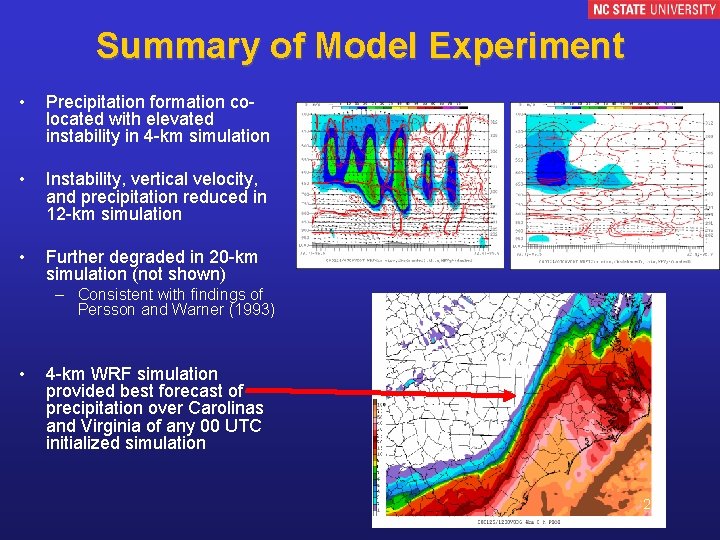

Summary of Model Experiment • Precipitation formation colocated with elevated instability in 4 -km simulation • Instability, vertical velocity, and precipitation reduced in 12 -km simulation • Further degraded in 20 -km simulation (not shown) – Consistent with findings of Persson and Warner (1993) • 4 -km WRF simulation provided best forecast of precipitation over Carolinas and Virginia of any 00 UTC initialized simulation 22

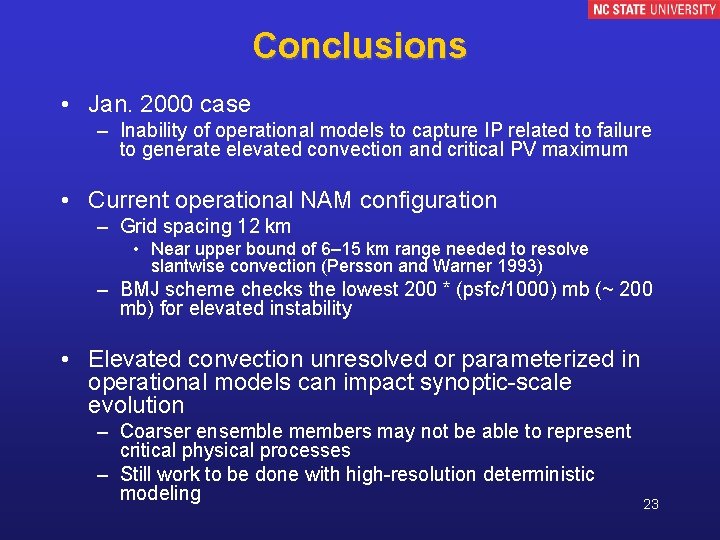

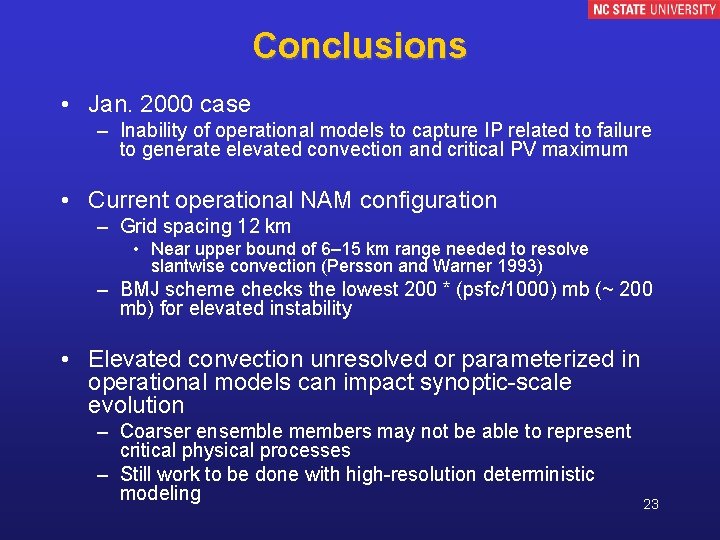

Conclusions • Jan. 2000 case – Inability of operational models to capture IP related to failure to generate elevated convection and critical PV maximum • Current operational NAM configuration – Grid spacing 12 km • Near upper bound of 6– 15 km range needed to resolve slantwise convection (Persson and Warner 1993) – BMJ scheme checks the lowest 200 * (psfc/1000) mb (~ 200 mb) for elevated instability • Elevated convection unresolved or parameterized in operational models can impact synoptic-scale evolution – Coarser ensemble members may not be able to represent critical physical processes – Still work to be done with high-resolution deterministic modeling 23

Acknowledgements • Sponsored by: – NOAA CSTAR grants NA 03 NWS 4680007 and NA-07 WA 0206 – NSF grant ATM-0342691 • Unidata program provided much of meteorological data • Level II radar data obtained from NCDC • Some RUC model data obtained from Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) Program, US Dept. of Energy • WRF model provided by NCAR • Ryan Torn of Univ. of Washington provided original WRF to GEMPAK conversion code 24

References Bennetts, D. A. , and B. J. Hoskins, 1979: Conditional symmetric instability – a possible explanation for frontal rainbands. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. , 105, 945– 962. Brennan, M. J. , and G. M. Lackmann, 2005: The influence of incipient latent heat release on the precipitation distribution of the 24 25 January 2000 cyclone. Mon. Wea. Rev. , 133, 19131937 Colman, B. R. , 1990 a: Thunderstorms above frontal surfaces in environments without positive CAPE. Part I: A climatology. Mon. Wea. Rev. , 118, 1103– 1121. , 1990 b: Thunderstorms above frontal surfaces in environments without positive CAPE. Part II: Organization and instability mechanisms. Mon. Wea. Rev. , 118, 1123– 1144. Emanuel, K. A. , 1985: Frontal circulations in the presence of small moist symmetric stability. J. Atmos. Sci. , 42, 1062– 1071. Martin. J. E. , 1998: The structure and evolution of a continental winter cyclone. Part II: Frontal forcing of an extreme snow event. Mon. Wea. Rev. , 126, 329 -348. Persson. P. O. G. , and T. T. Warner, 1993: Nonlinear hydrostatic conditional symmetric instability: Implications for numerical weather prediction. Mon. Wea. Rev. , 121, 1821– 1833. Schultz, D. M. , and P. N. Schumacher, 1999: The use and misuse of conditional symmetric instability. Mon. Wea. Rev. , 127, 2709 2732; Corrigendum, 128, 1573. 25