Model Checking Concurrent Programs Aarti Gupta aguptaneclabs com

Model Checking Concurrent Programs Aarti Gupta agupta@nec-labs. com Systems Analysis and Verification http: //www. nec-labs. com January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs

Acknowledgements q NEC Systems Analysis & Verification Group – – – – – Gogul Balakrishnan Malay Ganai Franjo Ivancic Vineet Kahlon Weihong Li Nadia Papakonstantinou Sriram Sankaranarayanan Nishant Sinha Chao Wang q Interns – Himanshu Jain, Yu Yang, Aleksandr Zaks, … January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 2

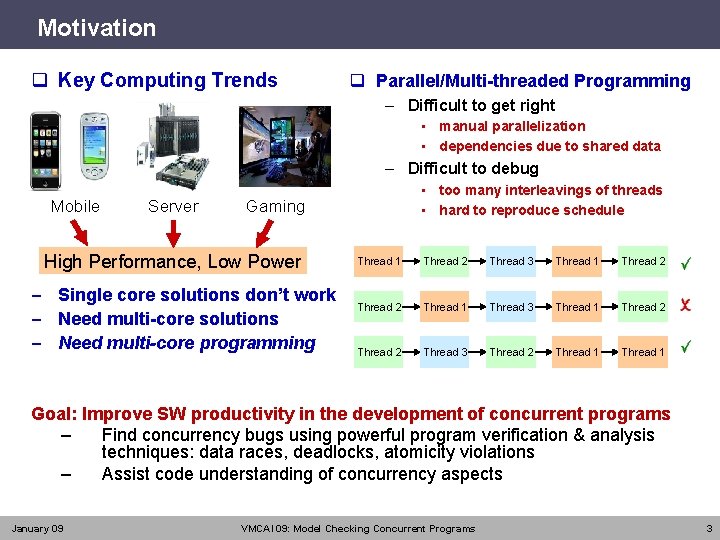

Motivation q Key Computing Trends q Parallel/Multi-threaded Programming – Difficult to get right • manual parallelization • dependencies due to shared data – Difficult to debug Mobile Server • too many interleavings of threads • hard to reproduce schedule Gaming High Performance, Low Power – Single core solutions don’t work – Need multi-core solutions – Need multi-core programming Thread 1 Thread 2 Thread 3 Thread 1 Thread 2 Thread 1 Thread 3 Thread 1 Thread 2 Thread 3 Thread 2 Thread 1 Goal: Improve SW productivity in the development of concurrent programs – Find concurrency bugs using powerful program verification & analysis techniques: data races, deadlocks, atomicity violations – Assist code understanding of concurrency aspects January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 3

Outline q Background q Model Checking Concurrent Programs – Results for Interacting Pushdown Systems q Practical Model Checking of Concurrent Programs – Four main strategies q Con. Save Platform q Summary & Challenges January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 4

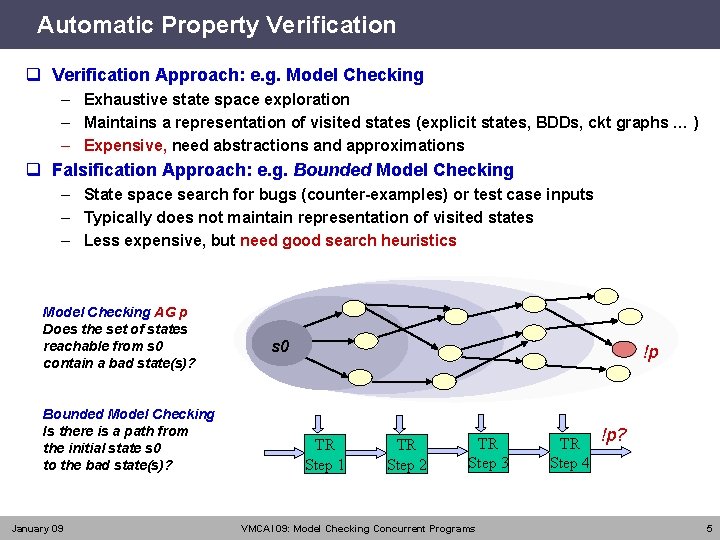

Automatic Property Verification q Verification Approach: e. g. Model Checking – Exhaustive state space exploration – Maintains a representation of visited states (explicit states, BDDs, ckt graphs … ) – Expensive, need abstractions and approximations q Falsification Approach: e. g. Bounded Model Checking – State space search for bugs (counter-examples) or test case inputs – Typically does not maintain representation of visited states – Less expensive, but need good search heuristics Model Checking AG p Does the set of states reachable from s 0 contain a bad state(s)? Bounded Model Checking Is there is a path from the initial state s 0 to the bad state(s)? January 09 s 0 !p TR Step 1 TR Step 2 TR Step 3 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs TR Step 4 !p? 5

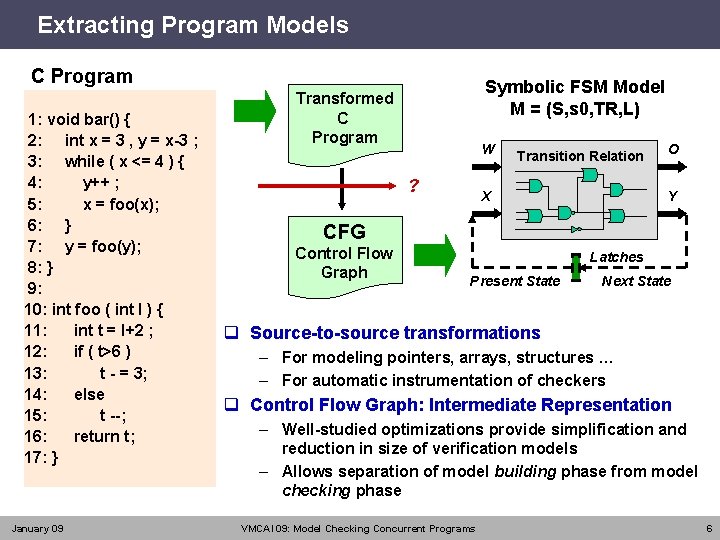

Extracting Program Models C Program 1: void bar() { 2: int x = 3 , y = x-3 ; 3: while ( x <= 4 ) { 4: y++ ; 5: x = foo(x); 6: } 7: y = foo(y); 8: } 9: 10: int foo ( int l ) { 11: int t = l+2 ; 12: if ( t>6 ) 13: t - = 3; 14: else 15: t --; 16: return t; 17: } January 09 Symbolic FSM Model M = (S, s 0, TR, L) Transformed C Program W ? Transition Relation X O Y CFG Control Flow Graph Latches Present State Next State q Source-to-source transformations – For modeling pointers, arrays, structures … – For automatic instrumentation of checkers q Control Flow Graph: Intermediate Representation – Well-studied optimizations provide simplification and reduction in size of verification models – Allows separation of model building phase from model checking phase VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 6

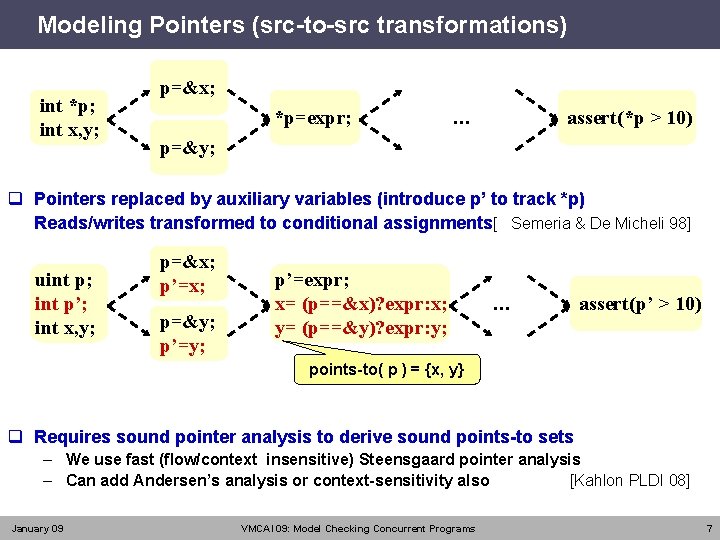

Modeling Pointers (src-to-src transformations) int *p; int x, y; p=&x; *p=expr; … assert(*p > 10) p=&y; q Pointers replaced by auxiliary variables (introduce p’ to track *p) Reads/writes transformed to conditional assignments[ Semeria & De Micheli 98] uint p; int p’; int x, y; p=&x; p’=x; p=&y; p’=y; p’=expr; x= (p==&x)? expr: x; y= (p==&y)? expr: y; … assert(p’ > 10) points-to( p ) = {x, y} q Requires sound pointer analysis to derive sound points-to sets – We use fast (flow/context insensitive) Steensgaard pointer analysis – Can add Andersen’s analysis or context-sensitivity also [Kahlon PLDI 08] January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 7

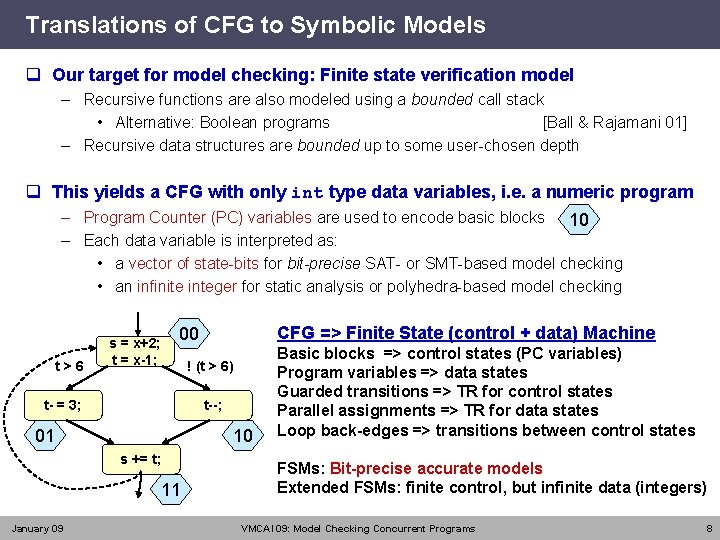

Translations of CFG to Symbolic Models q Our target for model checking: Finite state verification model – Recursive functions are also modeled using a bounded call stack • Alternative: Boolean programs [Ball & Rajamani 01] – Recursive data structures are bounded up to some user-chosen depth q This yields a CFG with only int type data variables, i. e. a numeric program – Program Counter (PC) variables are used to encode basic blocks 10 – Each data variable is interpreted as: • a vector of state-bits for bit-precise SAT- or SMT-based model checking • an infinite integer for static analysis or polyhedra-based model checking t>6 s = x+2; t = x-1; t- = 3; ! (t > 6) t--; 01 10 s += t; 11 January 09 CFG => Finite State (control + data) Machine 00 Basic blocks => control states (PC variables) Program variables => data states Guarded transitions => TR for control states Parallel assignments => TR for data states Loop back-edges => transitions between control states FSMs: Bit-precise accurate models Extended FSMs: finite control, but infinite data (integers) VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 8

![Veri. Sol Model Checking Platform [Ganai et al. 05], [Gupta et al. 06] Engines Veri. Sol Model Checking Platform [Ganai et al. 05], [Gupta et al. 06] Engines](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/2c74de200f39070f0b83f41f45c4babb/image-9.jpg)

Veri. Sol Model Checking Platform [Ganai et al. 05], [Gupta et al. 06] Engines for finding Bugs Engines for finding Proofs Proof Engines Proves correctness of properties using Unbounded Model Checking and Induction BMC Find bugs efficiently BMC: Bounded Model Checking UMC: Unbounded Model Checking EMM: Efficient Memory Modeling PBIA: Proof-Based Iterative Abstraction Distributed BMC Find bugs on network of workstations Efficient Representation (circuit simplifier) SMT solvers, BDDs+Polyhedra BMC + EMM + PBIA Reduce model size by identifying & removing irrelevant memories and logic Boolean Solver (SAT, BDD) BMC + EMM Find bugs in embedded memory systems using Efficient Memory Model BMC + PBIA Reduce model size by identifying & removing irrelevant logic January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 9

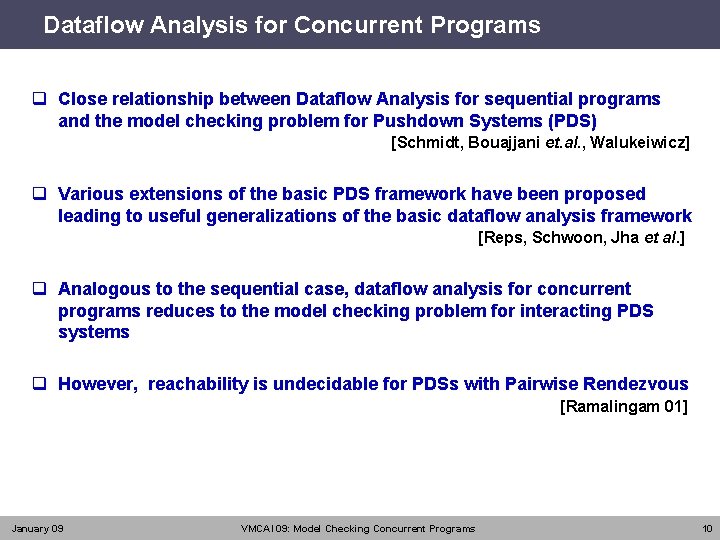

Dataflow Analysis for Concurrent Programs q Close relationship between Dataflow Analysis for sequential programs and the model checking problem for Pushdown Systems (PDS) [Schmidt, Bouajjani et. al. , Walukeiwicz] q Various extensions of the basic PDS framework have been proposed leading to useful generalizations of the basic dataflow analysis framework [Reps, Schwoon, Jha et al. ] q Analogous to the sequential case, dataflow analysis for concurrent programs reduces to the model checking problem for interacting PDS systems q However, reachability is undecidable for PDSs with Pairwise Rendezvous [Ramalingam 01] January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 10

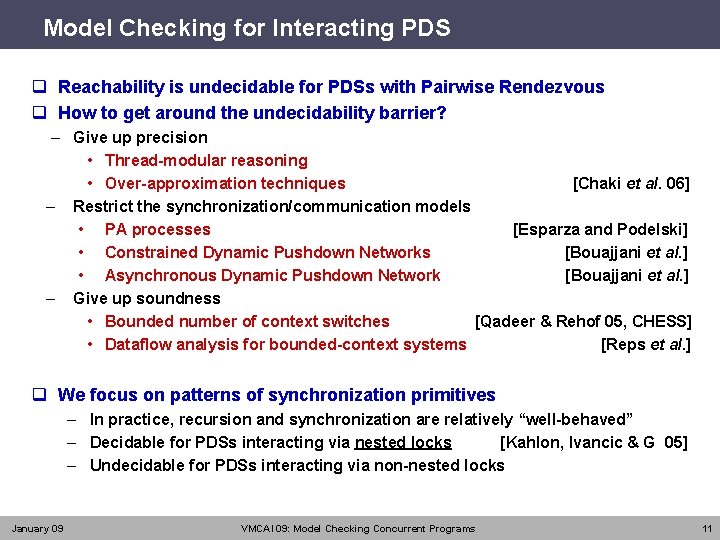

Model Checking for Interacting PDS q Reachability is undecidable for PDSs with Pairwise Rendezvous q How to get around the undecidability barrier? – Give up precision • Thread-modular reasoning • Over-approximation techniques [Chaki et al. 06] – Restrict the synchronization/communication models • PA processes [Esparza and Podelski] • Constrained Dynamic Pushdown Networks [Bouajjani et al. ] • Asynchronous Dynamic Pushdown Network [Bouajjani et al. ] – Give up soundness • Bounded number of context switches [Qadeer & Rehof 05, CHESS] • Dataflow analysis for bounded-context systems [Reps et al. ] q We focus on patterns of synchronization primitives – In practice, recursion and synchronization are relatively “well-behaved” – Decidable for PDSs interacting via nested locks [Kahlon, Ivancic & G 05] – Undecidable for PDSs interacting via non-nested locks January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 11

![Model Checking Double-indexed LTL Properties [Kahlon & G, POPL 07] q For L(F, G) Model Checking Double-indexed LTL Properties [Kahlon & G, POPL 07] q For L(F, G)](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/2c74de200f39070f0b83f41f45c4babb/image-12.jpg)

Model Checking Double-indexed LTL Properties [Kahlon & G, POPL 07] q For L(F, G) and L(U) the model checking problem is undecidable even for system comprised of non-interacting PDSs – For decidability, restriction to fragments L(G, X) and L(X, F, inf. F) q For PDSs interacting via nested locks the model checking problem is decidable only for the fragments – L(G, X) – L(X, F, inf. F) q For PDSs interacting via – Pairwise rendezvous, or – Asynchronous rendezvous, or – Broadcasts the model checking problem is decidable only for L(G, X) January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 12

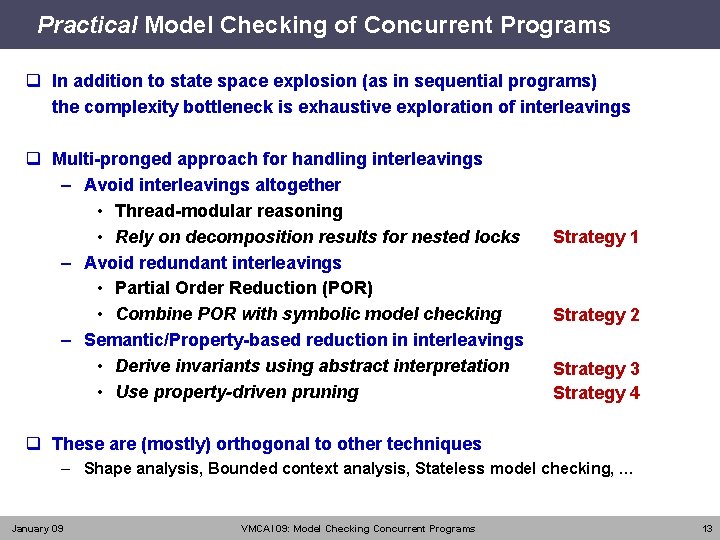

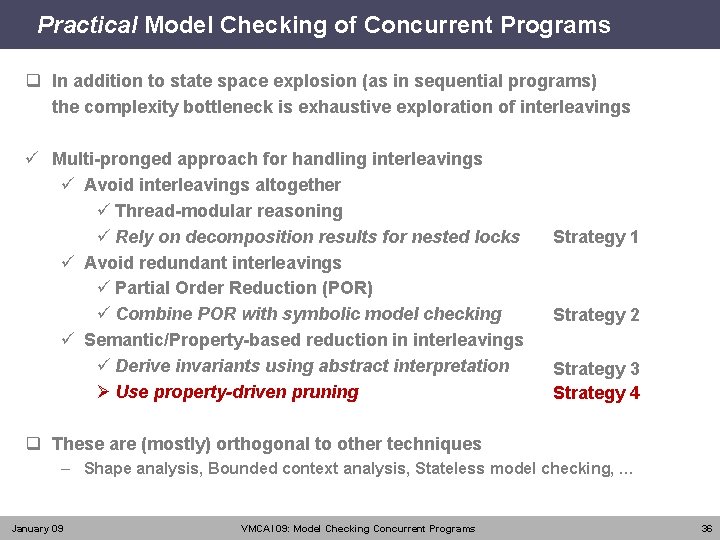

Practical Model Checking of Concurrent Programs q In addition to state space explosion (as in sequential programs) the complexity bottleneck is exhaustive exploration of interleavings q Multi-pronged approach for handling interleavings – Avoid interleavings altogether • Thread-modular reasoning • Rely on decomposition results for nested locks – Avoid redundant interleavings • Partial Order Reduction (POR) • Combine POR with symbolic model checking – Semantic/Property-based reduction in interleavings • Derive invariants using abstract interpretation • Use property-driven pruning Strategy 1 Strategy 2 Strategy 3 Strategy 4 q These are (mostly) orthogonal to other techniques – Shape analysis, Bounded context analysis, Stateless model checking, … January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 13

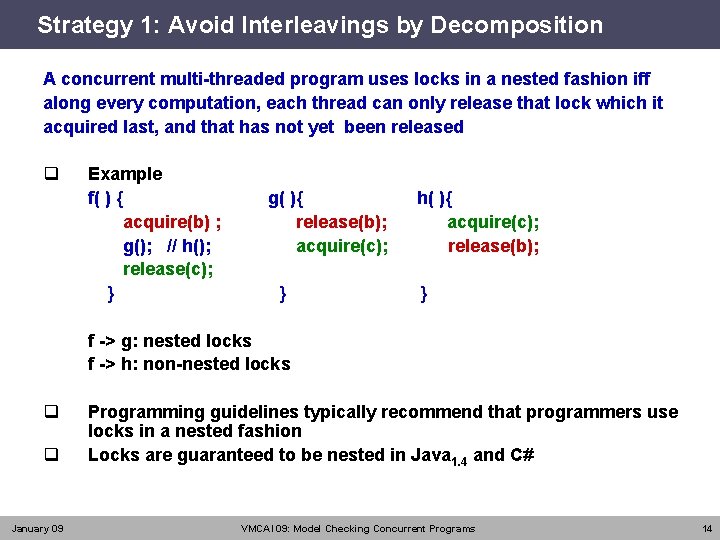

Strategy 1: Avoid Interleavings by Decomposition A concurrent multi-threaded program uses locks in a nested fashion iff along every computation, each thread can only release that lock which it acquired last, and that has not yet been released q Example f( ) { acquire(b) ; g(); // h(); release(c); } g( ){ release(b); acquire(c); } h( ){ acquire(c); release(b); } f -> g: nested locks f -> h: non-nested locks q q January 09 Programming guidelines typically recommend that programmers use locks in a nested fashion Locks are guaranteed to be nested in Java 1. 4 and C# VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 14

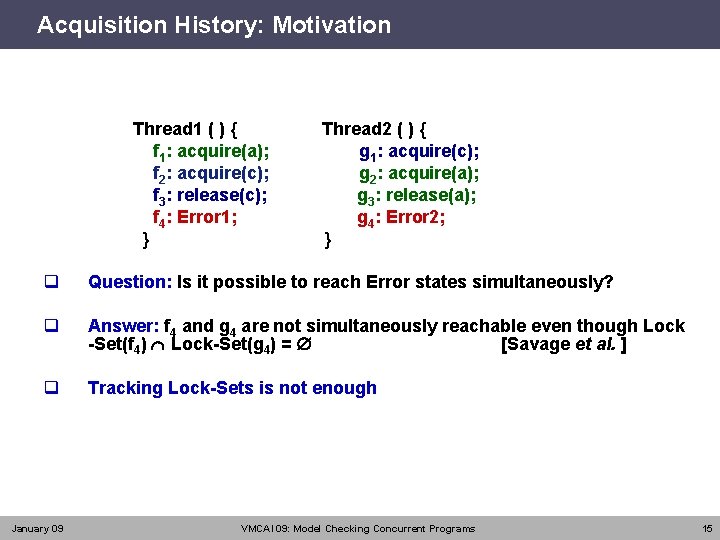

Acquisition History: Motivation Thread 1 ( ) { f 1: acquire(a); f 2: acquire(c); f 3: release(c); f 4: Error 1; } Thread 2 ( ) { g 1: acquire(c); g 2: acquire(a); g 3: release(a); g 4: Error 2; } q Question: Is it possible to reach Error states simultaneously? q Answer: f 4 and g 4 are not simultaneously reachable even though Lock -Set(f 4) Lock-Set(g 4) = [Savage et al. ] q Tracking Lock-Sets is not enough January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 15

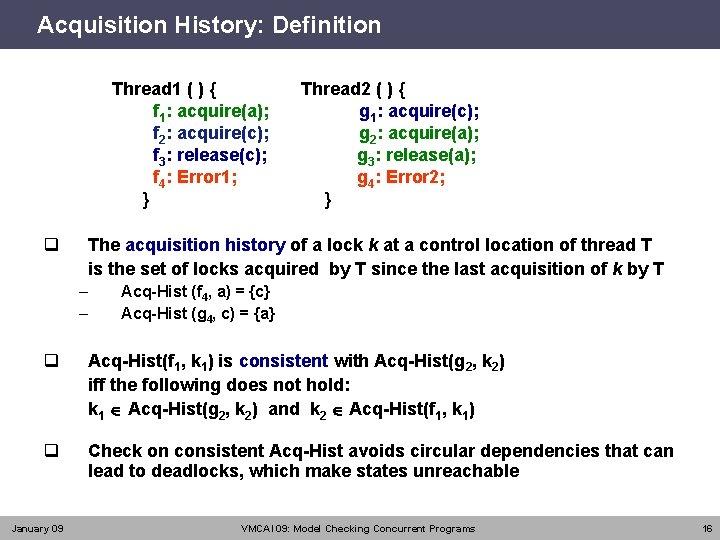

Acquisition History: Definition Thread 1 ( ) { f 1: acquire(a); f 2: acquire(c); f 3: release(c); f 4: Error 1; } q Thread 2 ( ) { g 1: acquire(c); g 2: acquire(a); g 3: release(a); g 4: Error 2; } The acquisition history of a lock k at a control location of thread T is the set of locks acquired by T since the last acquisition of k by T – – Acq-Hist (f 4, a) = {c} Acq-Hist (g 4, c) = {a} q Acq-Hist(f 1, k 1) is consistent with Acq-Hist(g 2, k 2) iff the following does not hold: k 1 Acq-Hist(g 2, k 2) and k 2 Acq-Hist(f 1, k 1) q Check on consistent Acq-Hist avoids circular dependencies that can lead to deadlocks, which make states unreachable January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 16

![Decomposition Result for Nested Locks [Kahlon et al. CAV 05] q States c 1 Decomposition Result for Nested Locks [Kahlon et al. CAV 05] q States c 1](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/2c74de200f39070f0b83f41f45c4babb/image-17.jpg)

Decomposition Result for Nested Locks [Kahlon et al. CAV 05] q States c 1 and c 2 in Thread 1 and Thread 2 , respectively, are simultaneously reachable iff – Lock-Set(c 1) Lock-Set(c 2) = – There exists some path with consistent acquisition histories i. e. , where there do not exist locks k and l such that : – l Acq-Hist (c 1, k) – k Acq-Hist (c 2, l) q Corollary: By tracking acquisition histories we can decompose model checking for a concurrent program to its individual threads – Augment states with acquisition histories AH – Reachability: There exist consistent acquisition histories AH 1 and AH 2 such that the augmented local states (c 1, AH 1) and (c 2, AH 2) are reachable individually in T 1 and T 2 , respectively – Polynomial in number of states, exponential in number of locks – Context-sensitive static analysis results in small locksets and AHs January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 17

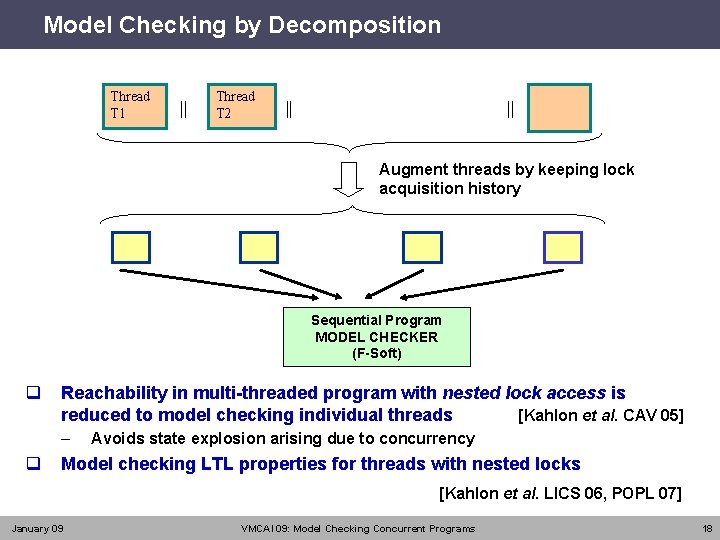

Model Checking by Decomposition Thread T 1 || Thread T 2 || || Augment threads by keeping lock acquisition history Sequential Program MODEL CHECKER (F-Soft) q Reachability in multi-threaded program with nested lock access is reduced to model checking individual threads [Kahlon et al. CAV 05] – q Avoids state explosion arising due to concurrency Model checking LTL properties for threads with nested locks [Kahlon et al. LICS 06, POPL 07] January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 18

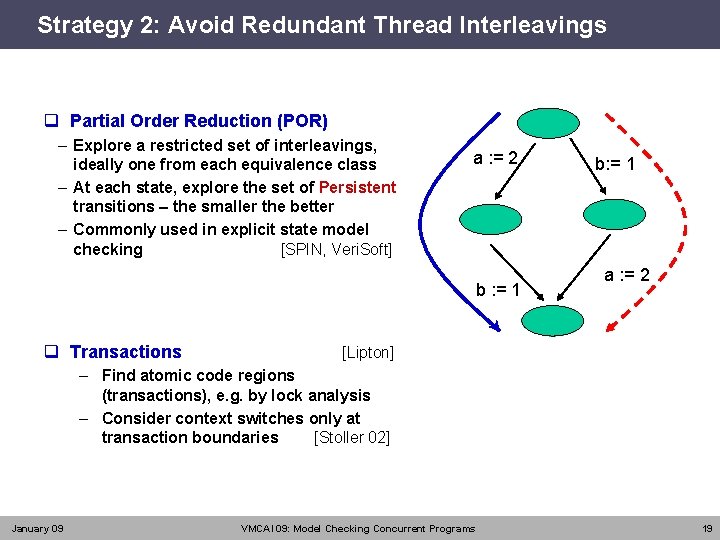

Strategy 2: Avoid Redundant Thread Interleavings q Partial Order Reduction (POR) – Explore a restricted set of interleavings, ideally one from each equivalence class – At each state, explore the set of Persistent transitions – the smaller the better – Commonly used in explicit state model checking [SPIN, Veri. Soft] a : = 2 b : = 1 q Transactions b: = 1 a : = 2 [Lipton] – Find atomic code regions (transactions), e. g. by lock analysis – Consider context switches only at transaction boundaries [Stoller 02] January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 19

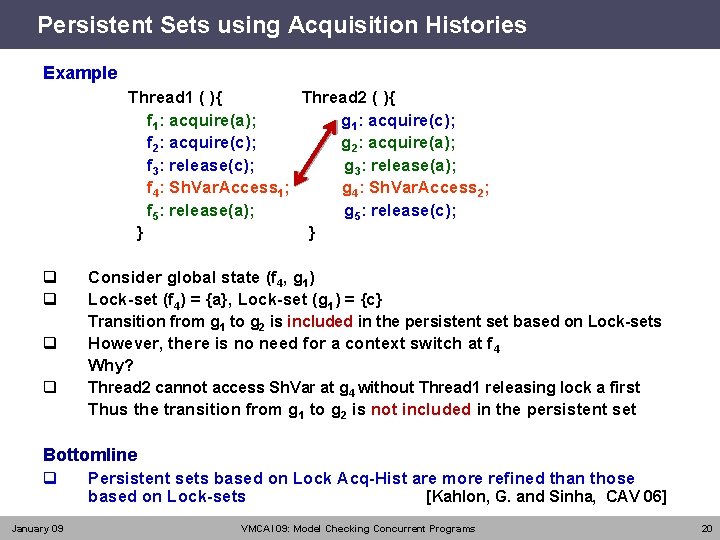

Persistent Sets using Acquisition Histories Example Thread 1 ( ){ Thread 2 ( ){ f 1: acquire(a); g 1: acquire(c); f 2: acquire(c); g 2: acquire(a); f 3: release(c); g 3: release(a); f 4: Sh. Var. Access 1; g 4: Sh. Var. Access 2; f 5: release(a); g 5: release(c); } } q q Consider global state (f 4, g 1) Lock-set (f 4) = {a}, Lock-set (g 1) = {c} Transition from g 1 to g 2 is included in the persistent set based on Lock-sets q However, there is no need for a context switch at f 4 Why? q Thread 2 cannot access Sh. Var at g 4 without Thread 1 releasing lock a first Thus the transition from g 1 to g 2 is not included in the persistent set Bottomline q Persistent sets based on Lock Acq-Hist are more refined than those based on Lock-sets January 09 [Kahlon, G. and Sinha, CAV 06] VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 20

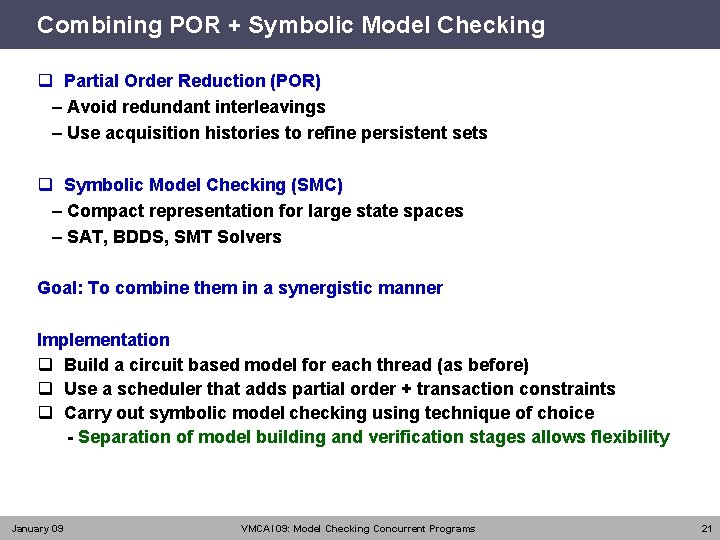

Combining POR + Symbolic Model Checking q Partial Order Reduction (POR) – Avoid redundant interleavings – Use acquisition histories to refine persistent sets q Symbolic Model Checking (SMC) – Compact representation for large state spaces – SAT, BDDS, SMT Solvers Goal: To combine them in a synergistic manner Implementation q Build a circuit based model for each thread (as before) q Use a scheduler that adds partial order + transaction constraints q Carry out symbolic model checking using technique of choice - Separation of model building and verification stages allows flexibility January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 21

![Generic Symbolic Model Checker Framework Shared variable detection [Kahlon et al. 07] Lockset analysis Generic Symbolic Model Checker Framework Shared variable detection [Kahlon et al. 07] Lockset analysis](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/2c74de200f39070f0b83f41f45c4babb/image-22.jpg)

Generic Symbolic Model Checker Framework Shared variable detection [Kahlon et al. 07] Lockset analysis Thread-safe static analysis Model Generation Scheduler Symbolic Constraints For Scheduler Symbolic Model Checking January 09 [SPIN, Veri. Soft] [Kahlon et al. CAV 06] POR, Transactions [Wang et al. TACAS 08] [Ganai et al. SPIN 08] Constraints MC Engine (BMC) VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 22

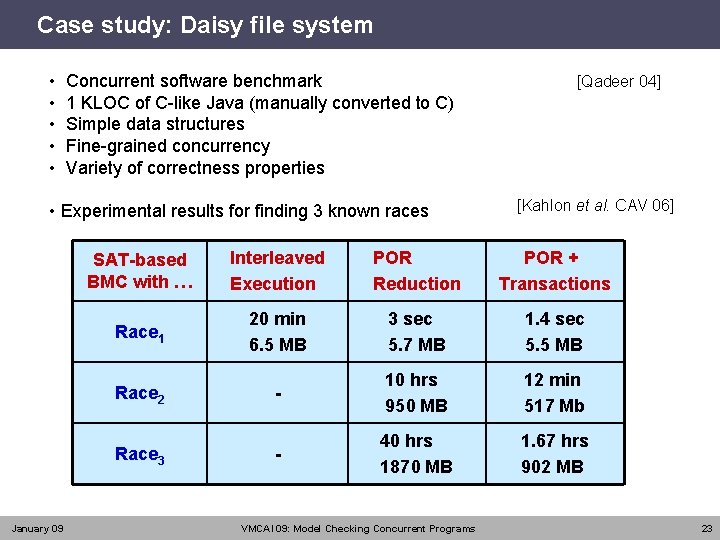

Case study: Daisy file system • • • Concurrent software benchmark 1 KLOC of C-like Java (manually converted to C) Simple data structures Fine-grained concurrency Variety of correctness properties • Experimental results for finding 3 known races [Kahlon et al. CAV 06] SAT-based BMC with … Interleaved Execution POR Reduction POR + Transactions Race 1 20 min 6. 5 MB 3 sec 5. 7 MB 1. 4 sec 5. 5 MB Race 2 - 10 hrs 950 MB 12 min 517 Mb - 40 hrs 1870 MB 1. 67 hrs 902 MB Race 3 January 09 [Qadeer 04] VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 23

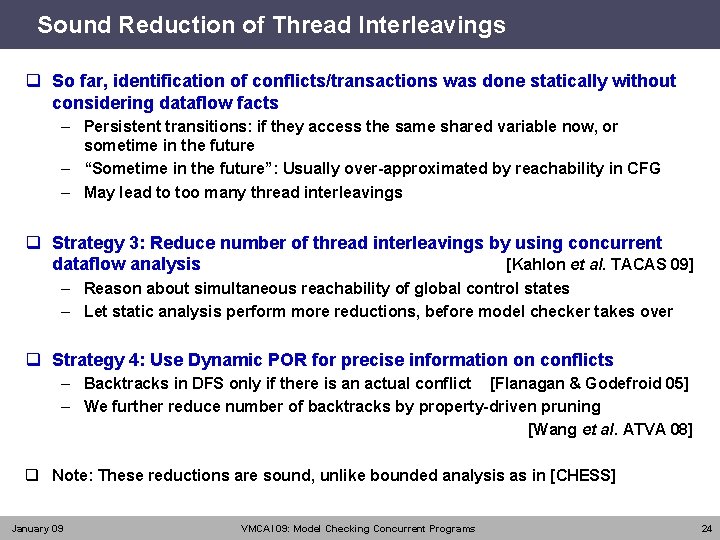

Sound Reduction of Thread Interleavings q So far, identification of conflicts/transactions was done statically without considering dataflow facts – Persistent transitions: if they access the same shared variable now, or sometime in the future – “Sometime in the future”: Usually over-approximated by reachability in CFG – May lead to too many thread interleavings q Strategy 3: Reduce number of thread interleavings by using concurrent dataflow analysis [Kahlon et al. TACAS 09] – Reason about simultaneous reachability of global control states – Let static analysis perform more reductions, before model checker takes over q Strategy 4: Use Dynamic POR for precise information on conflicts – Backtracks in DFS only if there is an actual conflict [Flanagan & Godefroid 05] – We further reduce number of backtracks by property-driven pruning [Wang et al. ATVA 08] q Note: These reductions are sound, unlike bounded analysis as in [CHESS] January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 24

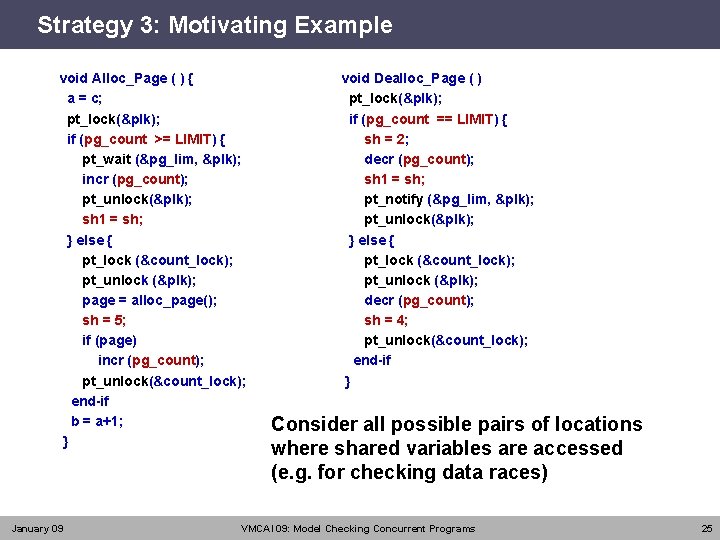

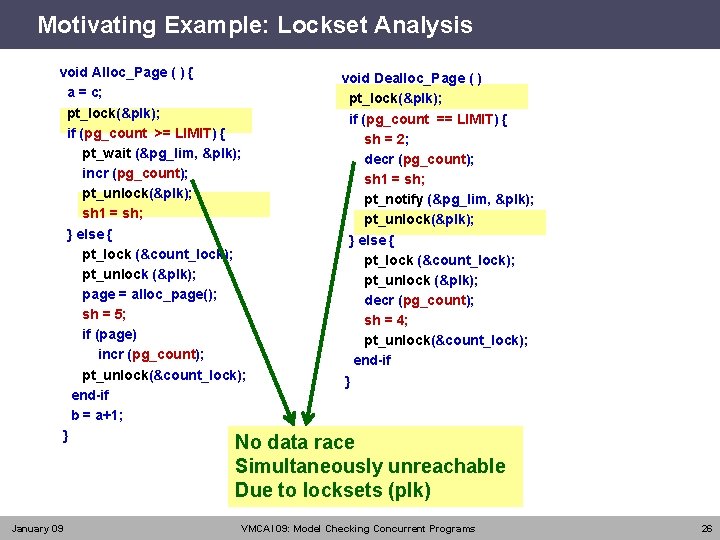

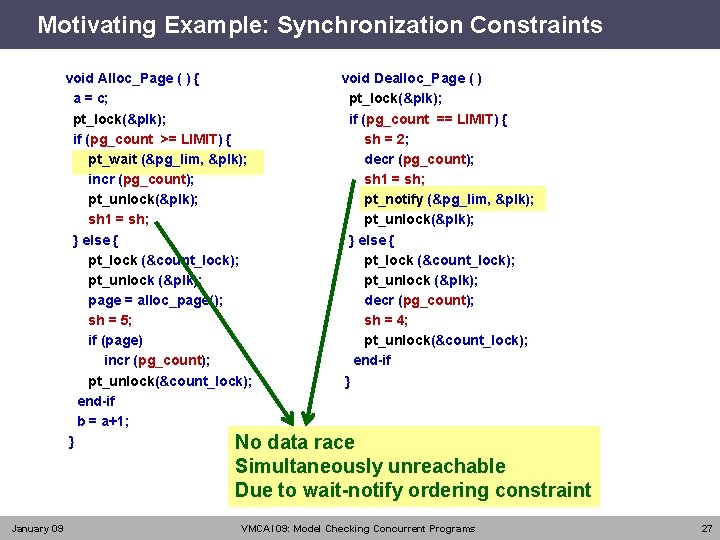

Strategy 3: Motivating Example void Alloc_Page ( ) { a = c; pt_lock(&plk); if (pg_count >= LIMIT) { pt_wait (&pg_lim, &plk); incr (pg_count); pt_unlock(&plk); sh 1 = sh; } else { pt_lock (&count_lock); pt_unlock (&plk); page = alloc_page(); sh = 5; if (page) incr (pg_count); pt_unlock(&count_lock); end-if b = a+1; } January 09 void Dealloc_Page ( ) pt_lock(&plk); if (pg_count == LIMIT) { sh = 2; decr (pg_count); sh 1 = sh; pt_notify (&pg_lim, &plk); pt_unlock(&plk); } else { pt_lock (&count_lock); pt_unlock (&plk); decr (pg_count); sh = 4; pt_unlock(&count_lock); end-if } Consider all possible pairs of locations where shared variables are accessed (e. g. for checking data races) VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 25

Motivating Example: Lockset Analysis void Alloc_Page ( ) { a = c; pt_lock(&plk); if (pg_count >= LIMIT) { pt_wait (&pg_lim, &plk); incr (pg_count); pt_unlock(&plk); sh 1 = sh; } else { pt_lock (&count_lock); pt_unlock (&plk); page = alloc_page(); sh = 5; if (page) incr (pg_count); pt_unlock(&count_lock); end-if b = a+1; } void Dealloc_Page ( ) pt_lock(&plk); if (pg_count == LIMIT) { sh = 2; decr (pg_count); sh 1 = sh; pt_notify (&pg_lim, &plk); pt_unlock(&plk); } else { pt_lock (&count_lock); pt_unlock (&plk); decr (pg_count); sh = 4; pt_unlock(&count_lock); end-if } No data race Simultaneously unreachable Due to locksets (plk) January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 26

Motivating Example: Synchronization Constraints void Alloc_Page ( ) { a = c; pt_lock(&plk); if (pg_count >= LIMIT) { pt_wait (&pg_lim, &plk); incr (pg_count); pt_unlock(&plk); sh 1 = sh; } else { pt_lock (&count_lock); pt_unlock (&plk); page = alloc_page(); sh = 5; if (page) incr (pg_count); pt_unlock(&count_lock); end-if b = a+1; } No void Dealloc_Page ( ) pt_lock(&plk); if (pg_count == LIMIT) { sh = 2; decr (pg_count); sh 1 = sh; pt_notify (&pg_lim, &plk); pt_unlock(&plk); } else { pt_lock (&count_lock); pt_unlock (&plk); decr (pg_count); sh = 4; pt_unlock(&count_lock); end-if } data race Simultaneously unreachable Due to wait-notify ordering constraint January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 27

Motivating Example void Alloc_Page ( ) { void Dealloc_Page ( ) a = c; pt_lock(&plk); if (pg_count == LIMIT) { if (pg_count >= LIMIT) { sh = 2; pt_wait (&pg_lim, &plk); decr (pg_count); incr (pg_count); sh 1 = sh; pt_unlock(&plk); pt_notify (&pg_lim, &plk); sh 1 = sh; pt_unlock(&plk); } else { pt_lock (&count_lock); pt_unlock (&plk); page = alloc_page(); decr (pg_count); sh = 5; sh = 4; if (page) pt_unlock(&count_lock); incr (pg_count); end-if How do we get these invariants? pt_unlock(&count_lock); } Abstract Interpretation of course : ) end-if b = a+1; NO, due to invariants at these locations } pg_count is in (-inf, LIMIT) in T 1 Data race? January 09 pg_count is in [LIMIT, +inf) in T 2 Therefore, these locations are not simultaneously reachable VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 28

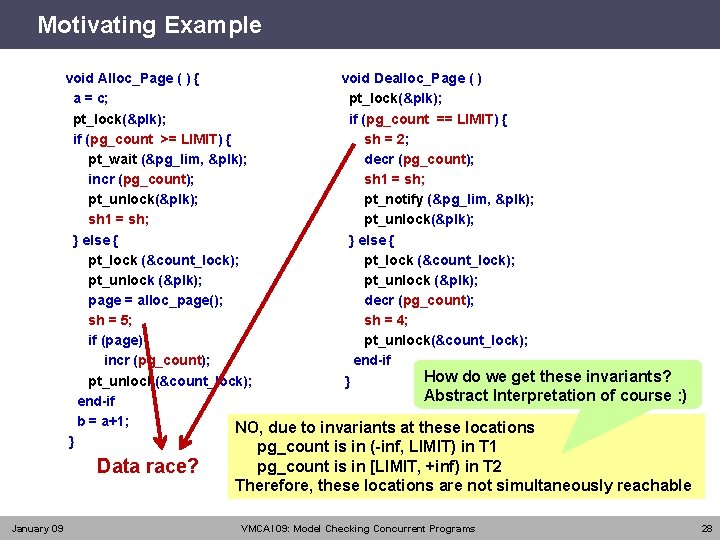

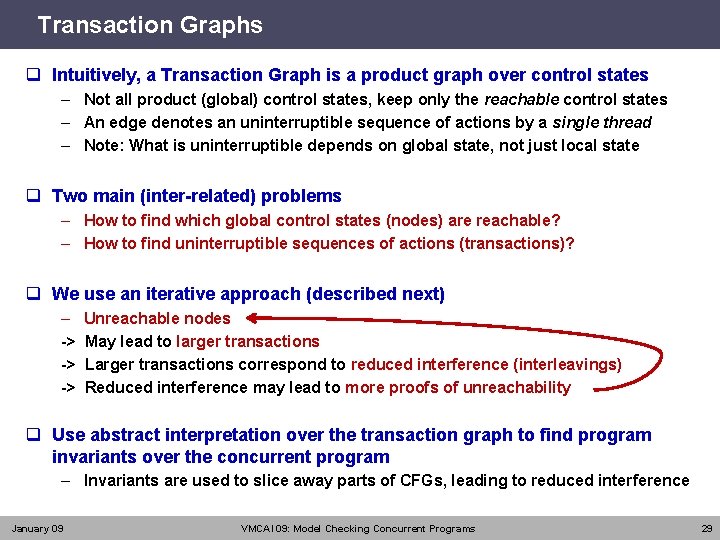

Transaction Graphs q Intuitively, a Transaction Graph is a product graph over control states – Not all product (global) control states, keep only the reachable control states – An edge denotes an uninterruptible sequence of actions by a single thread – Note: What is uninterruptible depends on global state, not just local state q Two main (inter-related) problems – How to find which global control states (nodes) are reachable? – How to find uninterruptible sequences of actions (transactions)? q We use an iterative approach (described next) – -> -> -> Unreachable nodes May lead to larger transactions Larger transactions correspond to reduced interference (interleavings) Reduced interference may lead to more proofs of unreachability q Use abstract interpretation over the transaction graph to find program invariants over the concurrent program – Invariants are used to slice away parts of CFGs, leading to reduced interference January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 29

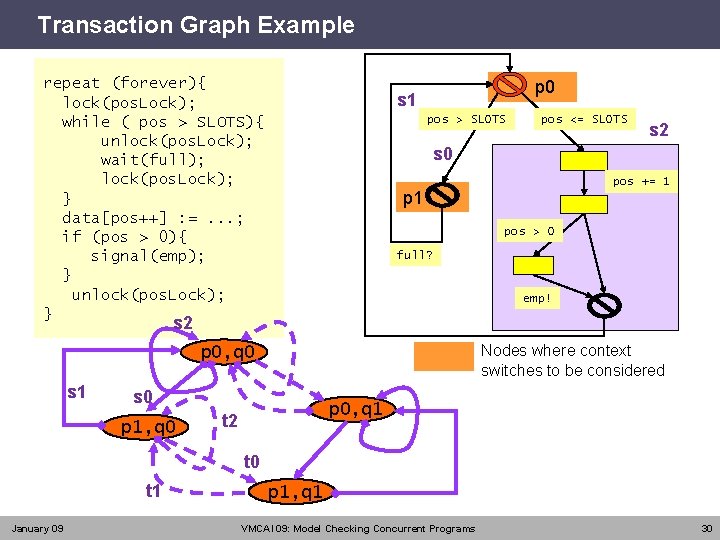

Transaction Graph Example repeat (forever){ lock(pos. Lock); while ( pos > SLOTS){ unlock(pos. Lock); wait(full); lock(pos. Lock); } data[pos++] : =. . . ; if (pos > 0){ signal(emp); } unlock(pos. Lock); } p 0 s 1 pos > SLOTS pos <= SLOTS s 2 s 0 pos += 1 pos > 0 full? emp! s 2 Nodes where context switches to be considered p 0, q 0 s 1 s 0 p 1, q 0 p 0, q 1 t 2 t 0 t 1 January 09 p 1, q 1 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 30

![Iterative Refinement of Transaction Graphs [Kahlon, Sankaranarayanan & G, TACAS 09] q Transaction Graph: Iterative Refinement of Transaction Graphs [Kahlon, Sankaranarayanan & G, TACAS 09] q Transaction Graph:](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/2c74de200f39070f0b83f41f45c4babb/image-31.jpg)

Iterative Refinement of Transaction Graphs [Kahlon, Sankaranarayanan & G, TACAS 09] q Transaction Graph: Abstract Representation for Thread Interleavings – At any stage, the transaction graph captures the set of interleavings that need to be considered for sound static analysis or model checking q Initial Transaction Graph – Use static POR to consider non-redundant interleavings • Over control states only, need to consider CFL reachability – Use synchronization constraints to eliminate unreachable nodes • For example, lock-based analysis, or wait-notify ordering constraints • Precise transaction identification under synchronization constraints: based on use of Parikh-bounded languages [Kahlon 08] q Iterative Refinement Repeat – Compute range, octagonal, or polyhedral invariants over the transaction graph – Use invariants to prove nodes unreachable and to simplify CFGs (slicing, …) – Re-compute transactions (static POR, synchronization) on the simplified CFGs Until transactions cannot be refined further January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 31

![Abstract Interpretation over Transaction Graphs [Kahlon, Sankaranarayanan & G, TACAS 09] s 2 p Abstract Interpretation over Transaction Graphs [Kahlon, Sankaranarayanan & G, TACAS 09] s 2 p](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/2c74de200f39070f0b83f41f45c4babb/image-32.jpg)

Abstract Interpretation over Transaction Graphs [Kahlon, Sankaranarayanan & G, TACAS 09] s 2 p 0, q 0 s 1 p, q s 0 p 1, q 0 p 0, q 1 t 2 Transaction by P t 0 t 1 p 1, q 1 < , > p’, q’ < ’, ’ > ’ = Meld ( ’, ) q Compute invariants < , > at each node <p, q> – – holds over the state of thread P (shared + local) holds over the state of thread Q (shared + local) q < , > must satisfy the consistency condition over shared variables – They must agree on values of the shared variables, i. e. |shared q Basic operation: Forward propagation (post) over transactional edge – Computed for each edge by sequential static analysis q Melding operator : for maintaining consistency – After post-condition < , > < ’, >, may also need to update to ’ – Meld ( , ) = ’, such that ’ and ’ |shared January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 32

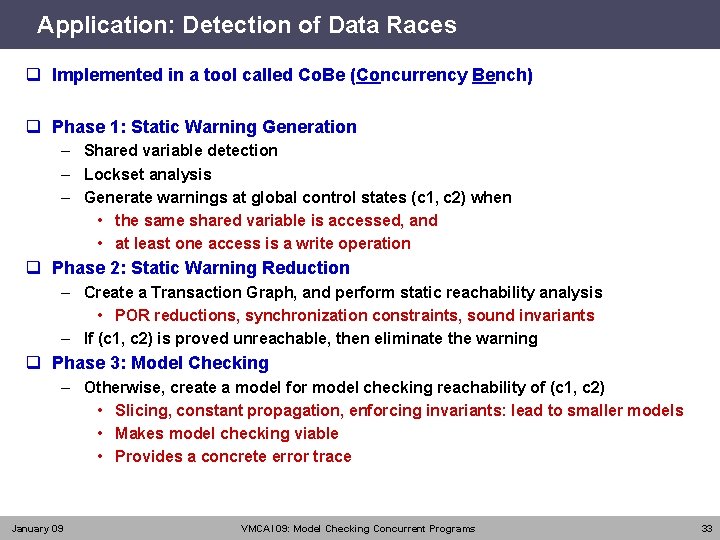

Application: Detection of Data Races q Implemented in a tool called Co. Be (Concurrency Bench) q Phase 1: Static Warning Generation – Shared variable detection – Lockset analysis – Generate warnings at global control states (c 1, c 2) when • the same shared variable is accessed, and • at least one access is a write operation q Phase 2: Static Warning Reduction – Create a Transaction Graph, and perform static reachability analysis • POR reductions, synchronization constraints, sound invariants – If (c 1, c 2) is proved unreachable, then eliminate the warning q Phase 3: Model Checking – Otherwise, create a model for model checking reachability of (c 1, c 2) • Slicing, constant propagation, enforcing invariants: lead to smaller models • Makes model checking viable • Provides a concrete error trace January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 33

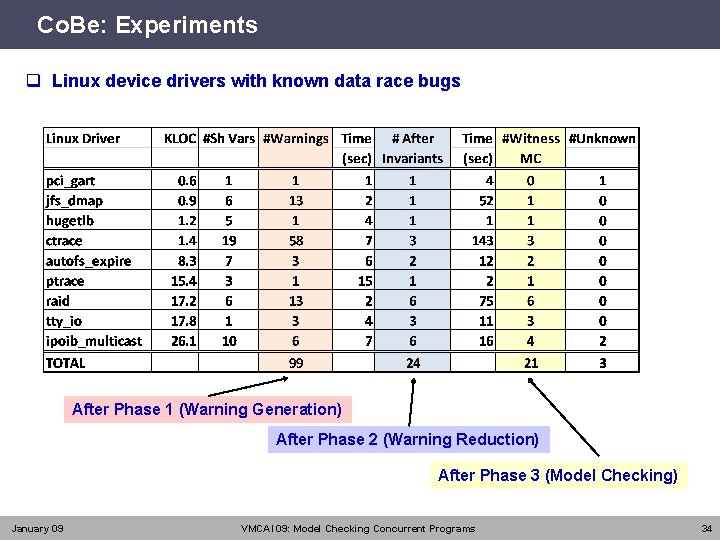

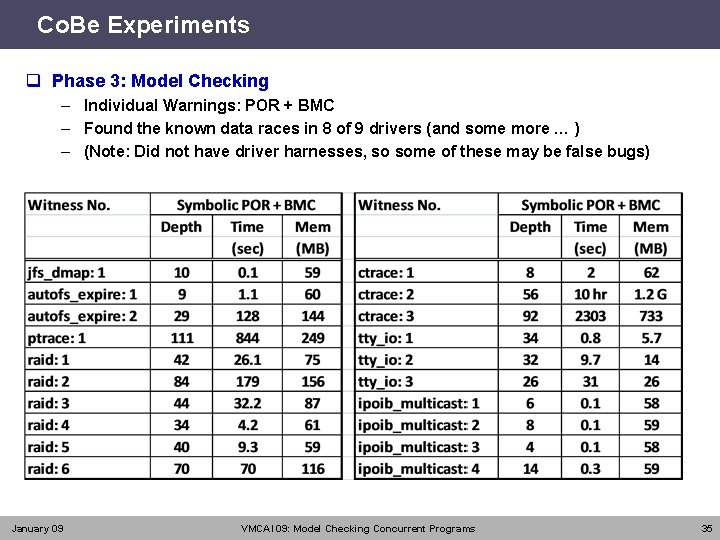

Co. Be: Experiments q Linux device drivers with known data race bugs After Phase 1 (Warning Generation) After Phase 2 (Warning Reduction) After Phase 3 (Model Checking) January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 34

Co. Be Experiments q Phase 3: Model Checking – Individual Warnings: POR + BMC – Found the known data races in 8 of 9 drivers (and some more … ) – (Note: Did not have driver harnesses, so some of these may be false bugs) January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 35

Practical Model Checking of Concurrent Programs q In addition to state space explosion (as in sequential programs) the complexity bottleneck is exhaustive exploration of interleavings ü Multi-pronged approach for handling interleavings ü Avoid interleavings altogether ü Thread-modular reasoning ü Rely on decomposition results for nested locks ü Avoid redundant interleavings ü Partial Order Reduction (POR) ü Combine POR with symbolic model checking ü Semantic/Property-based reduction in interleavings ü Derive invariants using abstract interpretation Ø Use property-driven pruning Strategy 1 Strategy 2 Strategy 3 Strategy 4 q These are (mostly) orthogonal to other techniques – Shape analysis, Bounded context analysis, Stateless model checking, … January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 36

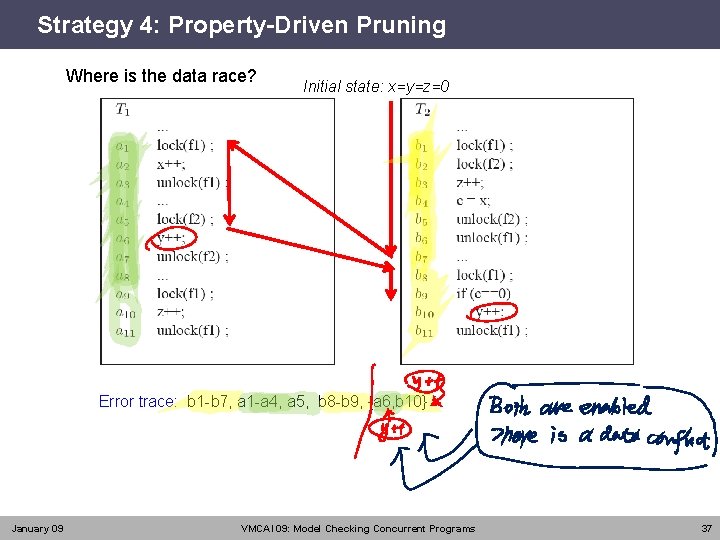

Strategy 4: Property-Driven Pruning Where is the data race? Initial state: x=y=z=0 Error trace: b 1 -b 7, a 1 -a 4, a 5, b 8 -b 9, {a 6, b 10} January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 37

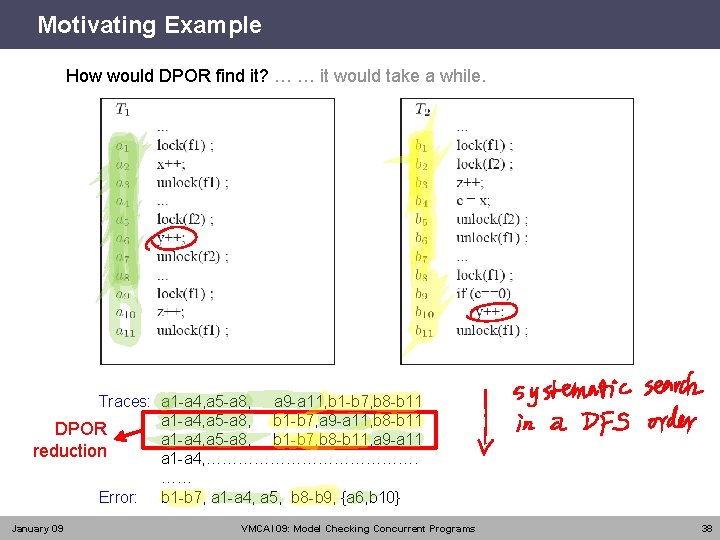

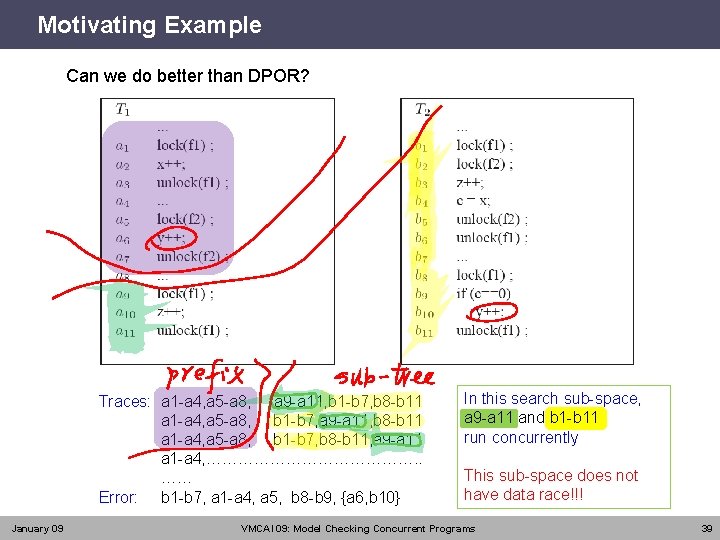

Motivating Example How would DPOR find it? … … it would take a while. Traces: a 1 -a 4, a 5 -a 8, a 9 -a 11, b 1 -b 7, b 8 -b 11 a 1 -a 4, a 5 -a 8, b 1 -b 7, a 9 -a 11, b 8 -b 11 DPOR a 1 -a 4, a 5 -a 8, b 1 -b 7, b 8 -b 11, a 9 -a 11 reduction a 1 -a 4, …………………. …… Error: b 1 -b 7, a 1 -a 4, a 5, b 8 -b 9, {a 6, b 10} January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 38

Motivating Example Can we do better than DPOR? Traces: a 1 -a 4, a 5 -a 8, a 9 -a 11, b 1 -b 7, b 8 -b 11 a 1 -a 4, a 5 -a 8, b 1 -b 7, a 9 -a 11, b 8 -b 11 a 1 -a 4, a 5 -a 8, b 1 -b 7, b 8 -b 11, a 9 -a 11 a 1 -a 4, …………………. . …… Error: b 1 -b 7, a 1 -a 4, a 5, b 8 -b 9, {a 6, b 10} January 09 In this search sub-space, a 9 -a 11 and b 1 -b 11 run concurrently This sub-space does not have data race!!! VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 39

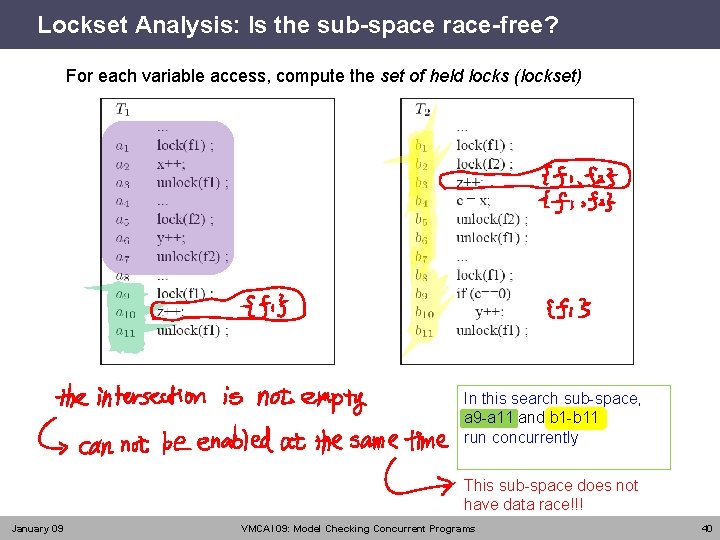

Lockset Analysis: Is the sub-space race-free? For each variable access, compute the set of held locks (lockset) In this search sub-space, a 9 -a 11 and b 1 -b 11 run concurrently This sub-space does not have data race!!! January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 40

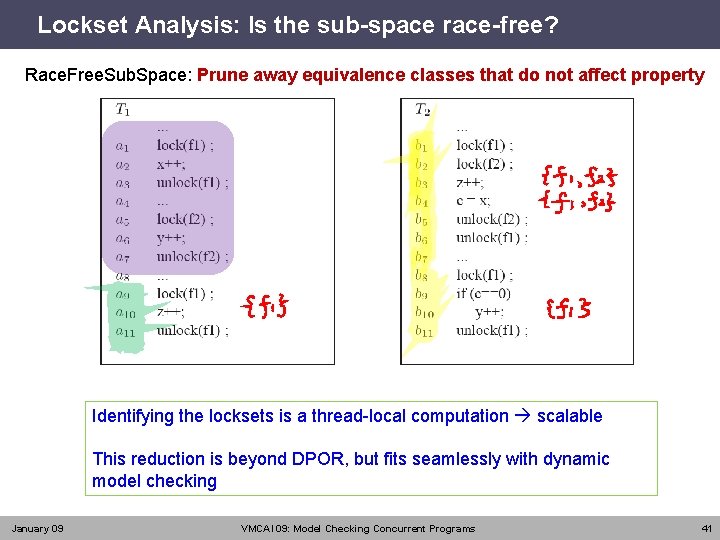

Lockset Analysis: Is the sub-space race-free? Race. Free. Sub. Space: Prune away equivalence classes that do not affect property Identifying the locksets is a thread-local computation scalable This reduction is beyond DPOR, but fits seamlessly with dynamic model checking January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 41

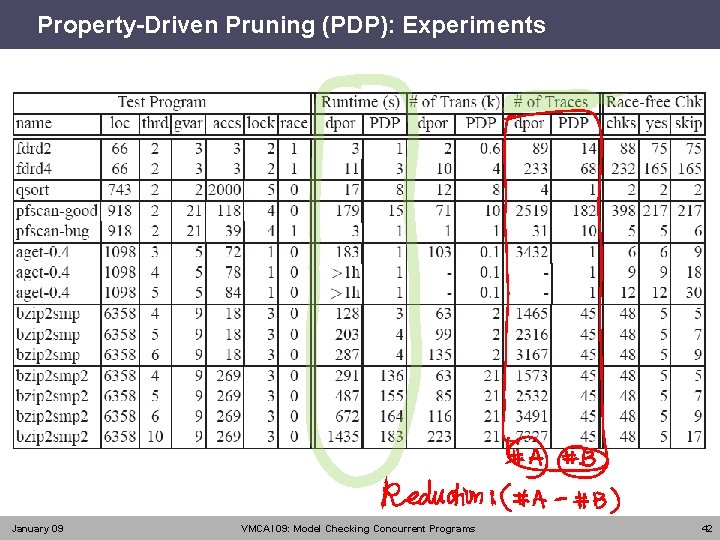

Property-Driven Pruning (PDP): Experiments January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 42

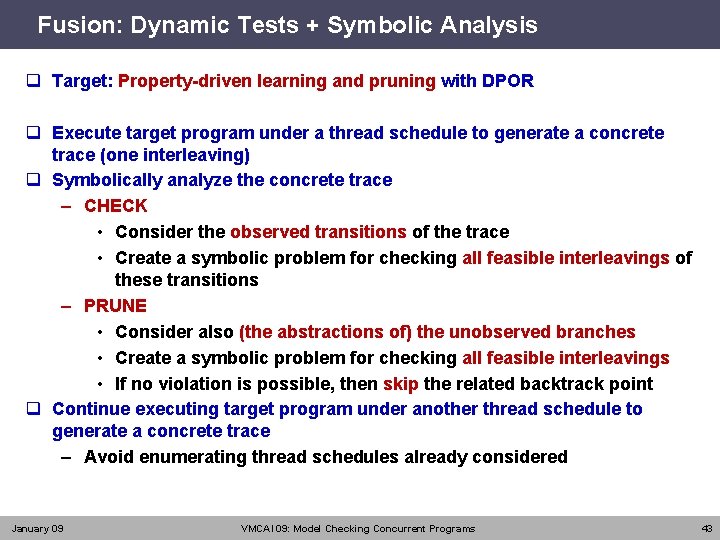

Fusion: Dynamic Tests + Symbolic Analysis q Target: Property-driven learning and pruning with DPOR q Execute target program under a thread schedule to generate a concrete trace (one interleaving) q Symbolically analyze the concrete trace – CHECK • Consider the observed transitions of the trace • Create a symbolic problem for checking all feasible interleavings of these transitions – PRUNE • Consider also (the abstractions of) the unobserved branches • Create a symbolic problem for checking all feasible interleavings • If no violation is possible, then skip the related backtrack point q Continue executing target program under another thread schedule to generate a concrete trace – Avoid enumerating thread schedules already considered January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 43

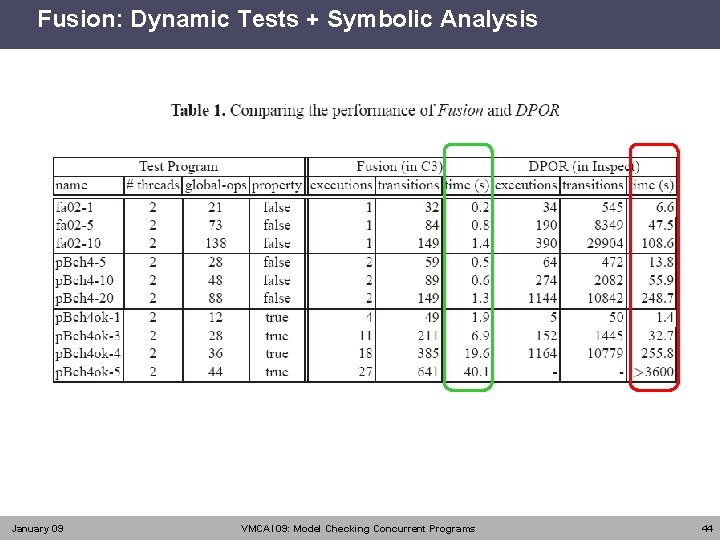

Fusion: Dynamic Tests + Symbolic Analysis January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 44

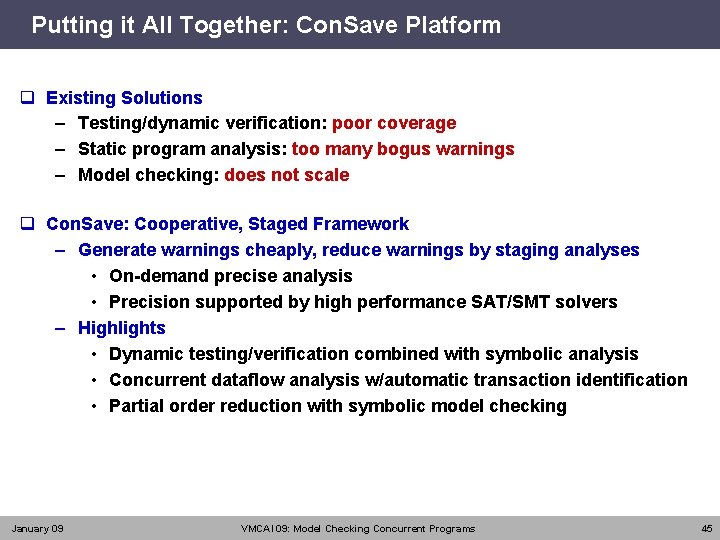

Putting it All Together: Con. Save Platform q Existing Solutions – Testing/dynamic verification: poor coverage – Static program analysis: too many bogus warnings – Model checking: does not scale q Con. Save: Cooperative, Staged Framework – Generate warnings cheaply, reduce warnings by staging analyses • On-demand precise analysis • Precision supported by high performance SAT/SMT solvers – Highlights • Dynamic testing/verification combined with symbolic analysis • Concurrent dataflow analysis w/automatic transaction identification • Partial order reduction with symbolic model checking January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 45

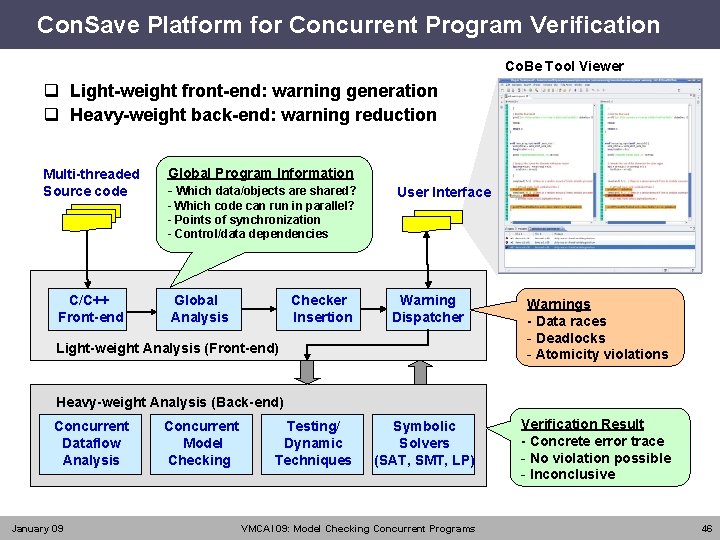

Con. Save Platform for Concurrent Program Verification Co. Be Tool Viewer q Light-weight front-end: warning generation q Heavy-weight back-end: warning reduction Multi-threaded Source code C/C++ Front-end Global Program Information - Which data/objects are shared? - Which code can run in parallel? - Points of synchronization - Control/data dependencies Global Analysis Checker Insertion User Interface Warning Dispatcher Warnings - Data races - Deadlocks - Atomicity violations Symbolic Solvers (SAT, SMT, LP) Verification Result - Concrete error trace - No violation possible - Inconclusive Light-weight Analysis (Front-end) Heavy-weight Analysis (Back-end) Concurrent Dataflow Analysis January 09 Concurrent Model Checking Testing/ Dynamic Techniques VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 46

Summary and Other Challenges q Concurrent program verification – Concurrency is pervasive, and very difficult to verify – Many promising technologies in formal methods • Testing/dynamic verification, Static analysis, Model checking, … • Controlling complexity of interleavings is key – Accuracy in models AND efficiency of analysis are needed for practical impact • Don’t give up too early on large models, on precision • Advancements in Decision Procedures (SAT, SMT, …) offer hope – Great opportunity, especially with proliferation of multi-cores q Better program analyses – Pointer alias analysis, shared variable detection, … – Heap shapes and properties q Modular component interfaces – Required for scaling up to large systems (MLOC) – Practical difficulties can be addressed by systematic development practices, but there should be a clear return on invested effort January 09 VMCAI 09: Model Checking Concurrent Programs 47

- Slides: 47