Mix It Up Summer 2014 Geometry and Algebra

Mix It Up Summer 2014 Geometry and Algebra: Powerful When Together

Goals for ALL Students National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) Standards: Learn to value mathematics Become confident in their ability to do mathematics Become mathematical problem solvers Learn to communicate mathematically Learn to reason mathematically Mix It Up Summer 2014 2

Geometry �Spatial sense – an intuition about shapes and the relationships among shapes A “feel” for the geometric aspects of surroundings and shapes formed by the objects in the environment Ability to mentally visualize objects and spatial relationships (to turn things around in your mind) �Geometry comprised of… Shapes and their properties Transformations Location Visualization Mix It Up Summer 2014 3

3 -D and 2 -D Shapes and Figures �Laurie’s lesson on 3 -d, name and describe a few � 2 -d shapes, name and describe a few �Quadrilaterals – name and describe a few �Are these quadrilaterals? Mix It Up Summer 2014 4

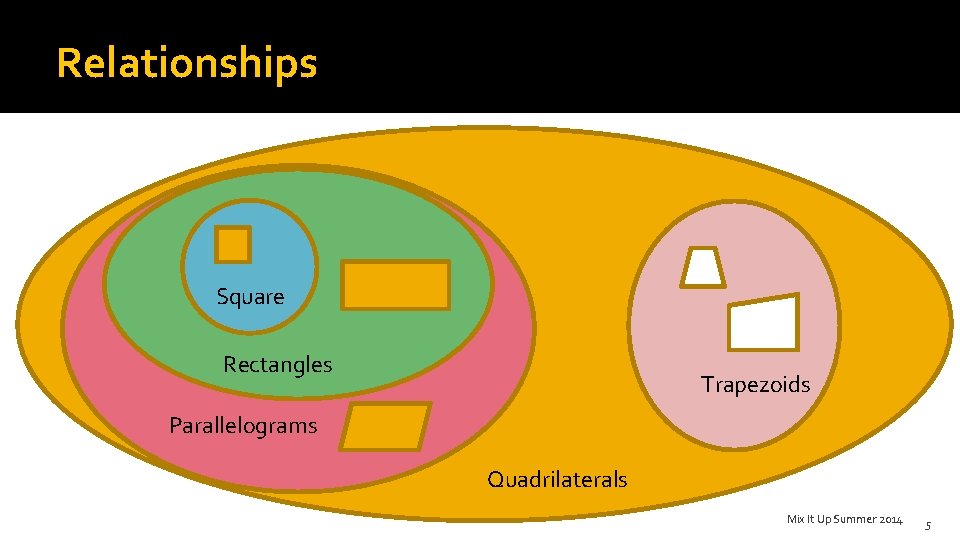

Relationships Square Rectangles Trapezoids Parallelograms Quadrilaterals Mix It Up Summer 2014 5

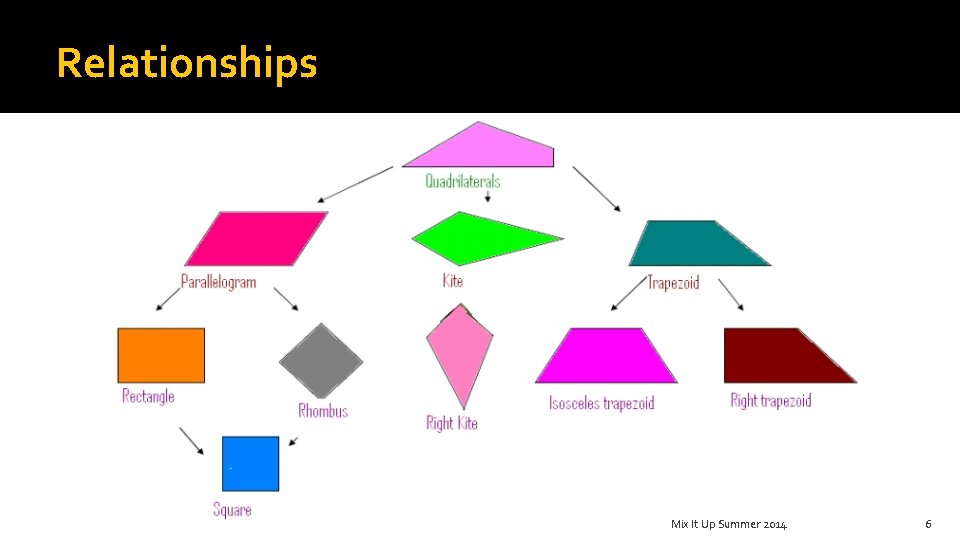

Relationships Mix It Up Summer 2014 6

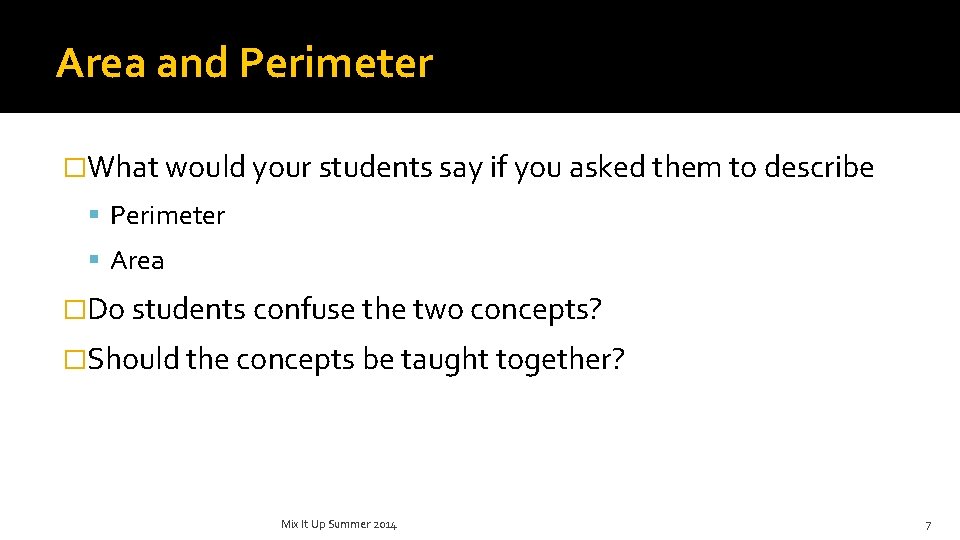

Area and Perimeter �What would your students say if you asked them to describe Perimeter Area �Do students confuse the two concepts? �Should the concepts be taught together? Mix It Up Summer 2014 7

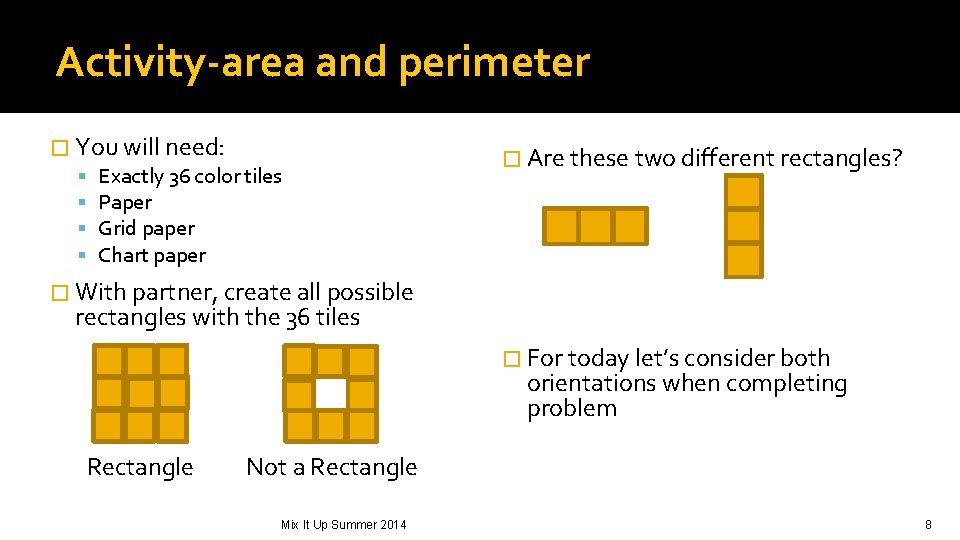

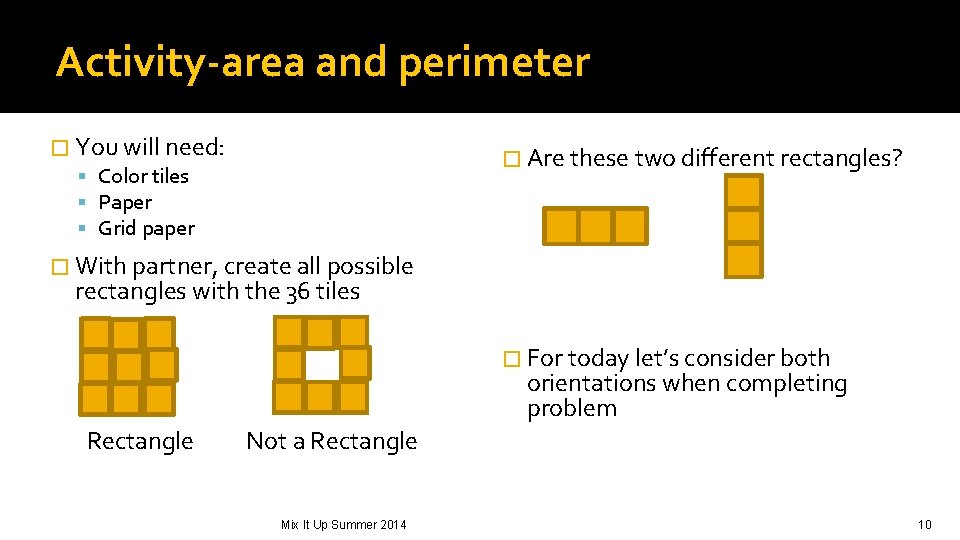

Activity-area and perimeter � You will need: Exactly 36 color tiles Paper Grid paper Chart paper � Are these two different rectangles? � With partner, create all possible rectangles with the 36 tiles � For today let’s consider both orientations when completing problem Rectangle Not a Rectangle Mix It Up Summer 2014 8

Activity-area and perimeter �On chart paper with four- Length Width Perimeter Area quadrant fold, illustrate your pattern with a drawing a table a graph a verbal description of maximum perimeter Mix It Up Summer 2014 9

Activity-area and perimeter � You will need: Color tiles Paper Grid paper � Are these two different rectangles? � With partner, create all possible rectangles with the 36 tiles � For today let’s consider both orientations when completing problem Rectangle Not a Rectangle Mix It Up Summer 2014 10

Activity-area and perimeter �On chart paper with four- quadrant fold, illustrate your pattern with a drawing a table a graph a verbal description of maximum area Mix It Up Summer 2014 Length Width Perimeter Area 11

Area and perimeter �What did you notice about the perimeter when the area is fixed? �What did you notice about the area when the perimeter is fixed? �How will this help students understand difference in perimeter and area? Mix It Up Summer 2014 12

Area and perimeter �What did you notice about the perimeter when the area is fixed? �What did you notice about the area when the perimeter is fixed? �How will this help students understand difference in perimeter and area? Mix It Up Summer 2014 13

Levels of Geometric Thought � Visual Level – level 0 � Van Hiele’s Husband & wife � Descriptive Level – level 1 Dutch educators � Relational Level – level 2 Studied many students thinking while solving geometric tasks � Five hierarchal levels of � Deductive Level - level 3 (usually high school) � Rigor – level 4 (usually college math major level) geometric thinking Mix It Up Summer 2014 14

Visual Level Characteristics (Level 0) The student identifies, compares and sorts shapes on the basis of their appearance as a whole ▪ For example, students recognize rectangles by its form but, a rectangle seems different to them then a square ▪ At this level rhombus is not recognized as a parallelogram solves problems using general properties and techniques (e. g. , overlaying, measuring) uses informal language does NOT analyze in terms of components Mix It Up Summer 2014 15

Analysis/Descriptive Level Characteristics Level 1) The student recognizes and describes a shape (e. g. , parallelogram) in terms of its properties. discovers properties experimentally by observing, measuring, drawing and modeling. uses formal language and symbols. does NOT use sufficient definitions. Lists many properties. does NOT see a need for proof of generalizations discovered empirically (inductively). Mix It Up Summer 2014 16

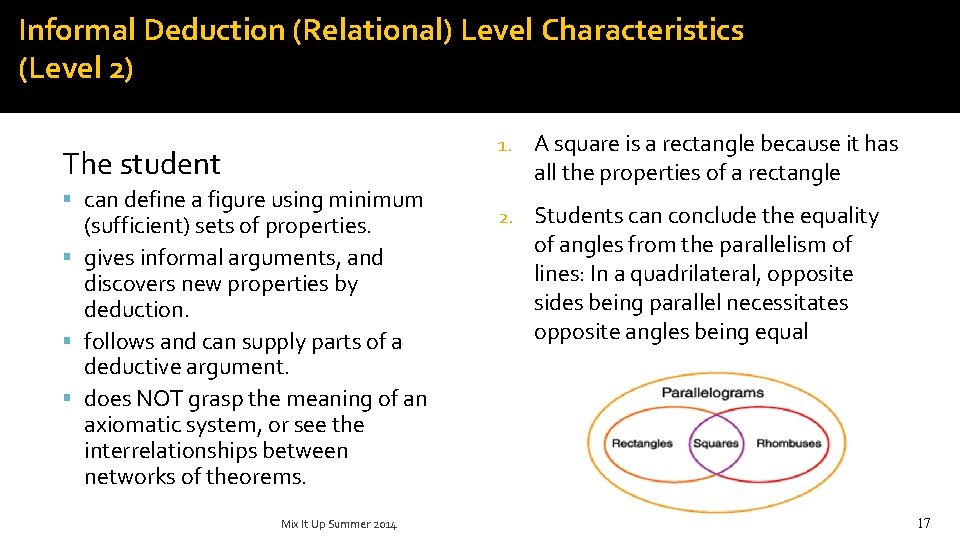

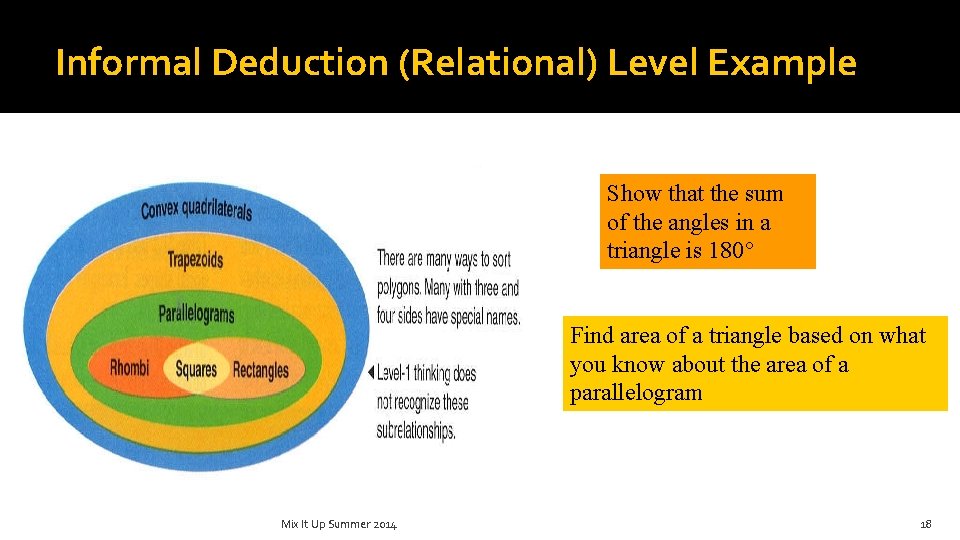

Informal Deduction (Relational) Level Characteristics (Level 2) The student can define a figure using minimum (sufficient) sets of properties. gives informal arguments, and discovers new properties by deduction. follows and can supply parts of a deductive argument. does NOT grasp the meaning of an axiomatic system, or see the interrelationships between networks of theorems. Mix It Up Summer 2014 1. A square is a rectangle because it has all the properties of a rectangle 2. Students can conclude the equality of angles from the parallelism of lines: In a quadrilateral, opposite sides being parallel necessitates opposite angles being equal 17

Informal Deduction (Relational) Level Example Show that the sum of the angles in a triangle is 180° Find area of a triangle based on what you know about the area of a parallelogram Mix It Up Summer 2014 18

Deductive Level Characteristics (Level 3) – High School Geometry � Students prove theorems deductively and establish interrelationships among networks of theorems in the Euclidean geometry � Thinking is concerned with the meaning of deduction, with the converse of a theorem, with axioms, and with necessary and sufficient conditions � Students seek to prove facts inductively � It would be possible to develop an axiomatic system of geometry, but the axiomatics themselves belong to the next (fourth) level Mix It Up Summer 2014 19

Rigor Characteristics (Level 4) – Mathematics Majors � Students establish theorems in different postulational systems and analyze/compare these systems For example, students can compare Euclidean geometry (plane geometry) with spherical geometry � Figures are defined only by symbols bound by relations �A comparative study of the various deductive systems can be accomplished � Students have acquired a scientific insight into geometry Mix It Up Summer 2014 20

Major Characteristics of the Levels � Levels are sequential and hierarchal � What is implicit at one level becomes explicit at the next level � Material taught to students above their level is subject to reduction of level � Progress from one level to the next is more dependant on instructional experience than on age or maturation � One goes through various “phases” in proceeding from one level to the next Students do not automatically progress; they gain abstraction and sophistication in their thinking as a result of their experiences. Mix It Up Summer 2014 21

Characteristics of Levels of Thinking � Students may reason at multiple levels or at intermediate levels. � Children advance at different rates for different concepts. �Each level has its own language/vocabulary, set of symbols, and network of relations. � Terms that are considered correct at one level may be modified at another. � Instruction and language at a level higher than the student may inhibit learning. Mix It Up Summer 2014 22

Levels of Geometric Thinking �Looking back to the levels of thinking, what level was the fixed area/perimeter activity? �Discuss with your table partners. �Be ready to share with class and support your thinking. Mix It Up Summer 2014 23

The TEKS �Let’s look at the TEKS �For the perimeter/area activity, create a chart describing The grade level and TEKS the activity included The prerequisite knowledge and skills (TEKS) that prepare students for the concepts in the activity The level of geometric thinking involved in the specific TEKS How to extend the activity to a higher grade level Mix It Up Summer 2014 24

Representations Revisited �Encourage students to develop and use multiple representations �Help them build connections across these representations so that they can transition from concrete to abstract ways of thinking. �“Seeing similarities in the ways to represent different situations is an important step toward abstraction” (NCTM 2000, 138). �Remember to ALWAYS move from Concrete manipulative, Pictorial/graphical, Abstract (verbal/numerical) Mix It Up Summer 2014 25

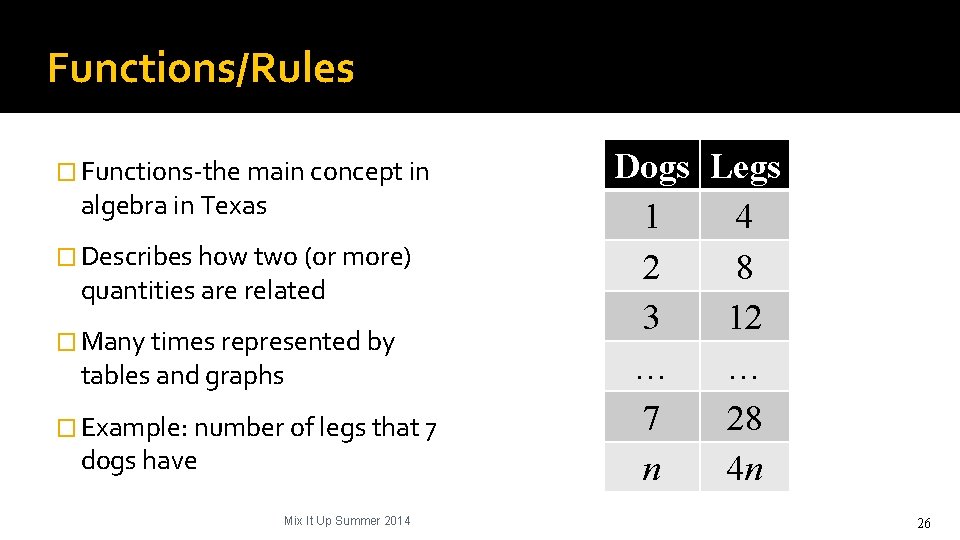

Functions/Rules � Functions-the main concept in algebra in Texas � Describes how two (or more) quantities are related � Many times represented by tables and graphs � Example: number of legs that 7 dogs have Mix It Up Summer 2014 Dogs Legs 1 4 2 8 3 12 … … 7 28 n 4 n 26

Number of Dogs (input) Process Number of Eyes (output) 1 2 2 2+2 or 2 x 1 or 2 x 2 2 4 3 4 5 6 7 2+2+2+2+2+2 2+2+2+2 or 2 x 3 or 2 x 4 or 2 x 5 or 2 x 6 or 2 x 7 6 8 10 12 14 n Recursive rule – each entry is found by adding subtracting, multiplying, dividing, etc. to previous entry (looks up or down a table) 2 n Explicit rule – uses a rule or equation based in the input term to determine the output (looks across the table) Mix It Up Summer 2014 27

Mix It Up Summer 2014 28

Using Pattern Blocks Take out a yellow hexagon; Make a hexagon using the red trapezoids. How many trapezoids did it take to make a hexagon? Make a larger hexagon with trapezoids. How many trapezoids did it take to make a hexagon? Continue making the next 3 larger hexagons Create a chart to illustrate. Find a rule for the pattern. Term Number of Blocks 1 2 Sketch 2 3 4 5 State how many trapezoids it will take to make the 8 th hexagon. Mix It Up Summer 2014 29

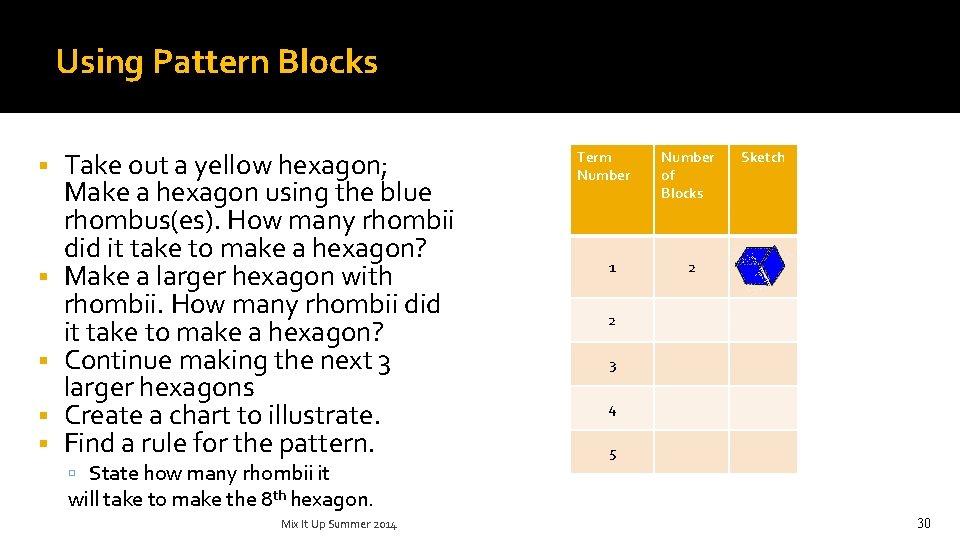

Using Pattern Blocks Take out a yellow hexagon; Make a hexagon using the blue rhombus(es). How many rhombii did it take to make a hexagon? Make a larger hexagon with rhombii. How many rhombii did it take to make a hexagon? Continue making the next 3 larger hexagons Create a chart to illustrate. Find a rule for the pattern. State how many rhombii it Term Number 1 Number of Blocks Sketch 2 2 3 4 5 will take to make the 8 th hexagon. Mix It Up Summer 2014 30

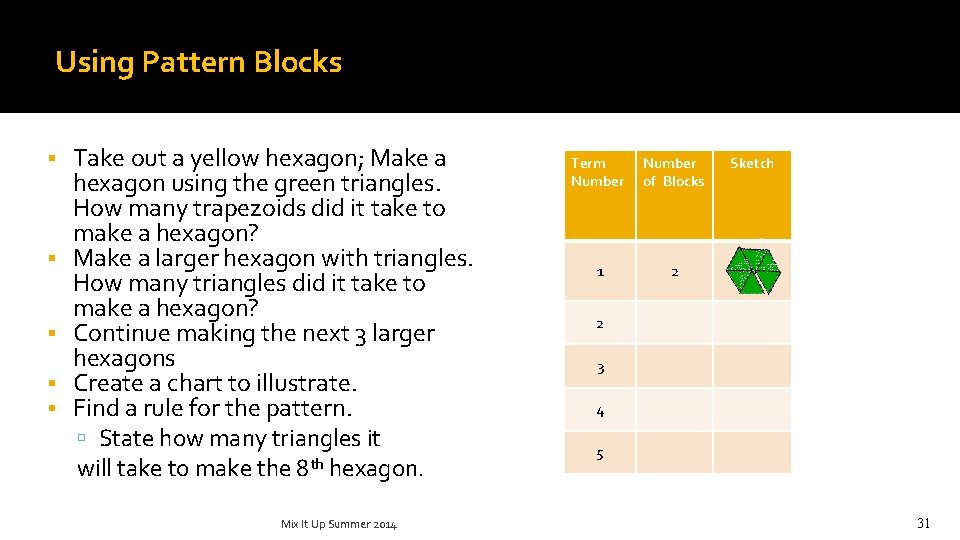

Using Pattern Blocks Take out a yellow hexagon; Make a hexagon using the green triangles. How many trapezoids did it take to make a hexagon? Make a larger hexagon with triangles. How many triangles did it take to make a hexagon? Continue making the next 3 larger hexagons Create a chart to illustrate. Find a rule for the pattern. State how many triangles it will take to make the 8 th hexagon. Mix It Up Summer 2014 Term Number of Blocks 1 2 Sketch 2 3 4 5 31

For your assigned pattern �On chart paper, illustrate your pattern With a drawing With a table A graph With a function (rule) With a verbal description Mix It Up Summer 2014 32

Habits of Mind Mathematical Habits of Mind are productive ways of thinking that support the learning and application of formal mathematics. The learning of mathematics is as much about developing these habits of mind as it is about understanding established results of mathematics. Patti talked about the Science Habits of Mind Mix It Up Summer 2014 33

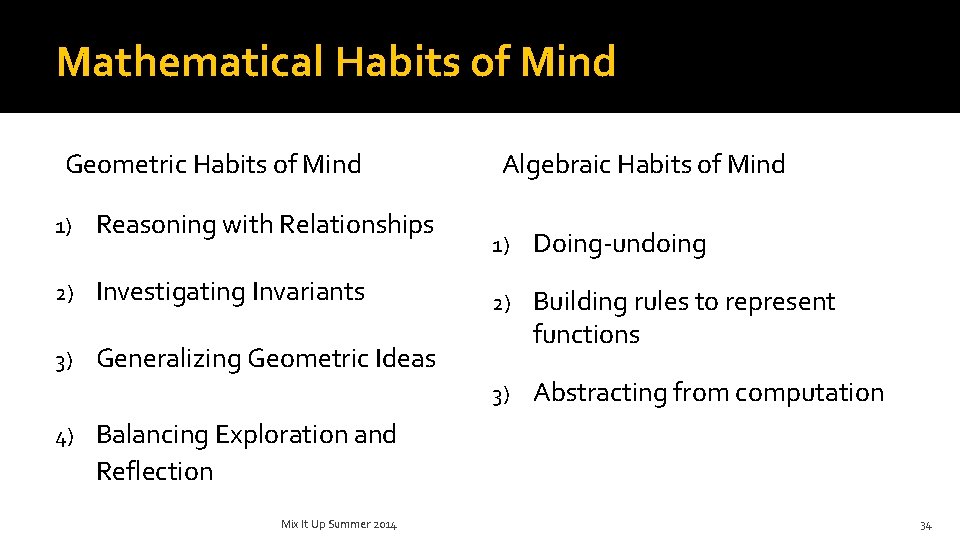

Mathematical Habits of Mind Geometric Habits of Mind 1) Reasoning with Relationships 2) Investigating Invariants 3) Generalizing Geometric Ideas 4) Algebraic Habits of Mind 1) Doing-undoing 2) Building rules to represent functions 3) Abstracting from computation Balancing Exploration and Reflection Mix It Up Summer 2014 34

Habits of Mind �Looking back activities, What Algebraic Habits of Mind did the activities involve? What Geometric Habits of Mind did the activities involve? �Discuss with your table partners. �Be ready to share with class and support your thinking. Mix It Up Summer 2014 35

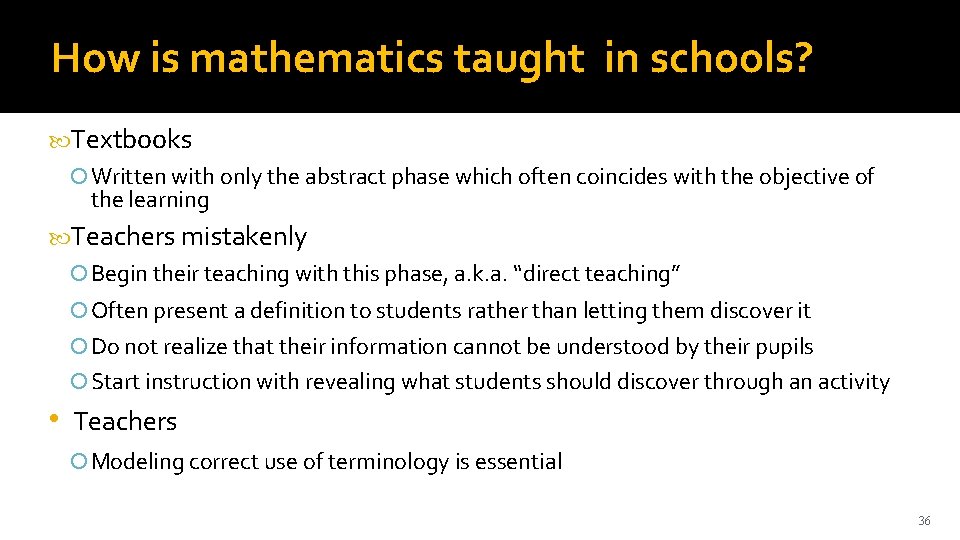

How is mathematics taught in schools? Textbooks Written with only the abstract phase which often coincides with the objective of the learning Teachers mistakenly Begin their teaching with this phase, a. k. a. “direct teaching” Often present a definition to students rather than letting them discover it Do not realize that their information cannot be understood by their pupils Start instruction with revealing what students should discover through an activity • Teachers Modeling correct use of terminology is essential Mix It Up Summer 2014 36

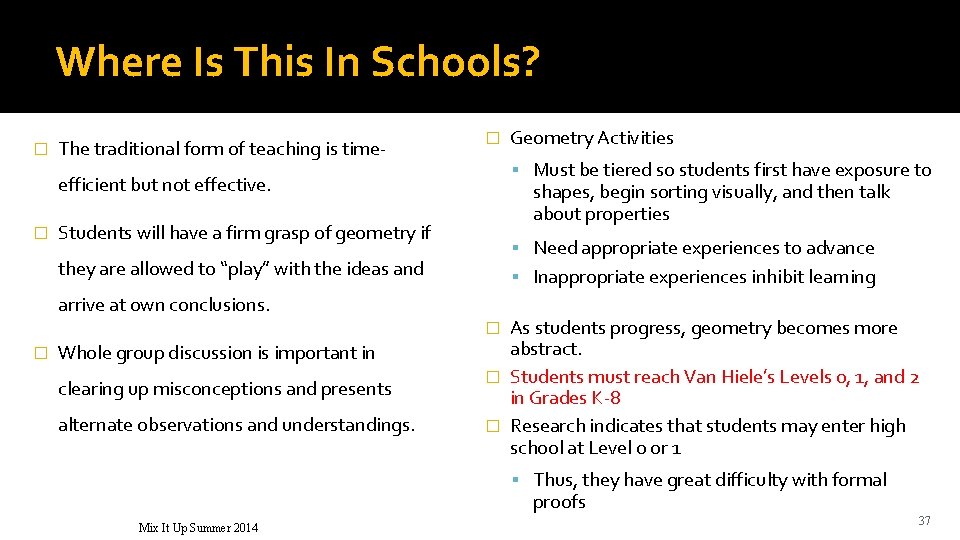

Where Is This In Schools? � The traditional form of teaching is time- � Must be tiered so students first have exposure to efficient but not effective. � shapes, begin sorting visually, and then talk about properties Students will have a firm grasp of geometry if Need appropriate experiences to advance they are allowed to “play” with the ideas and arrive at own conclusions. Geometry Activities Inappropriate experiences inhibit learning As students progress, geometry becomes more abstract. � Students must reach Van Hiele’s Levels 0, 1, and 2 in Grades K-8 � Research indicates that students may enter high school at Level 0 or 1 � � Whole group discussion is important in clearing up misconceptions and presents alternate observations and understandings. Thus, they have great difficulty with formal proofs Mix It Up Summer 2014 37

�STOP HERE IN OCTOBER Mix It Up Summer 2014 38

Geometric Habits of Mind �In groups of four Read your assigned papers On chart paper, create an explanation of your assigned GHo. M Include examples If your paper had a mathematics problem, solve and illustrate the problem (time permitting) Relate to the mathematical levels of thinking (Levels 0 -4) Mix It Up Summer 2014 39

Reasoning with Relationships � Actively looking for relationships within and between figures, such as congruence, similarity Names properties of shapes Constructs and deconstructs shapes Reasons with symmetry Asks questions concerning how alike, how different Mix It Up Summer 2014 Internal questions include: � “How are these figures alike? ” � “In How many ways are they alike? ” � “How are these figures different? ” � “What would I have to do to this object to make it like that object? ” 40

Investigating Invariants � Invariant – remains unchanged as other tings vary. Could be … Orientation Location Angles � Performs transformations without prompting � Notices not all properties change during a transformation � Asks questions like How did that get from here to � Analyzing properties affected by a transformation Mix It Up Summer 2014 there? What changed? Why? What stayed the same? Why? 41

Generalizing Geometric Ideas � Wants to understand describe the “always” and “every” related to geometric concepts Asks questions like “Does this happen in every case? ” Conjectures about every, always, and “Why would this happen in every case? ” “Can I think of examples when this is not true? ” “Would this apply in other dimensions? ” when Tests conjectures Makes convincing arguments to support conclusion Uses one solution to generate another Notices a rule that’s true for entire set of figures Wonders what happens when context changes Mix It Up Summer 2014 42

Balancing Exploration and Reflection �Tries various approaches (often as result of hypothesis) �Regularly considers what worked, what learned �Modifies hypothesis �Asks questions like… What would happen if I…? What did the action or result tell me? Mix It Up Summer 2014 43

GHo. M and Levels of Geometric Thinking �So far we have done two activities Toothpick perimeter Diagonals of quadrilaterals �What GHo. M has each activity involved? Discuss with your table mates and be prepared to defend your decisions Mix It Up Summer 2014 44

Analyze Activities �Go back to activities posted �What level of van Hiele is each activity? �Which Geometry Habits of Mind did you employ when doing activity? �What questions can you add to determine level? �How can you enrich activity to place on higher level? Mix It Up Summer 2014 45

Generalization: Goal of Algebraic Thinking �Algebra described as generalized arithmetic �Arithmetic effective in describing static situations �Algebra is dynamic and deals with how things change �Children can appreciate the significance of change and the need to describe and predict variation Mix It Up Summer 2014 46

Generalization: Goal of Algebraic Thinking � The central goal of algebraic thinking To get children to think about, describe, and justify what is going on in general with regard to some mathematical situation. � Children should be able to develop a generalization, a statement that describes a general mathematical truth about some set of data. Geometric Habits of Mind 1) Reasoning with Relationships 2) Investigating Invariants 3) Generalizing Geometric Ideas 4) Balancing Exploration and Reflection � Three instructional strategies — representations, questioning, and listening—are all critical components in helping children build their own generalizations. Mix It Up Summer 2014 47

Three levels of Justification �Franke, and Levi (2003) describe three levels of arguments or justifications that children make: (1) appealing to an authority figure (a conjecture is true because “the teacher said so”) (2) looking at particular examples or cases (3) building generalizable arguments. What level of van Hiele’s? What GHo. M? Mix It Up Summer 2014 48

Algebraic Thinking � Students use language to describe informal generalizations and connect symbols to the language, a process which produces formal (algebraic) generalizations the language component is critical - students are required to articulate their own movement from concrete to abstract � Abstractions – beginning with the concrete enables students to then access higher levels of abstraction such as writing a linear function rule for the toothpick problem or generalizing properties of quadrilaterals/diagonals � The TEKS for mathematics require building and making connections among concrete, verbal, numeric, graphic, and symbolic representations of relationships between quantities Mix It Up Summer 2014 49

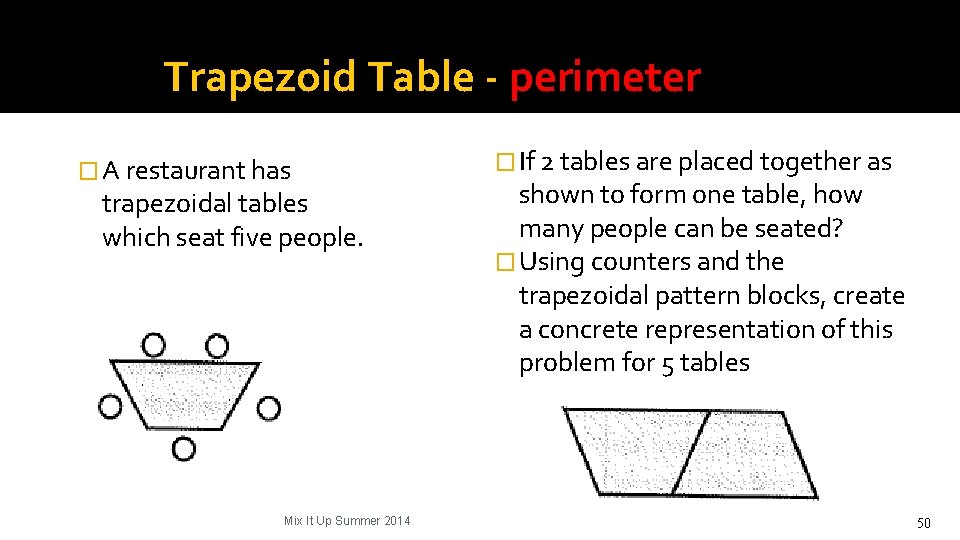

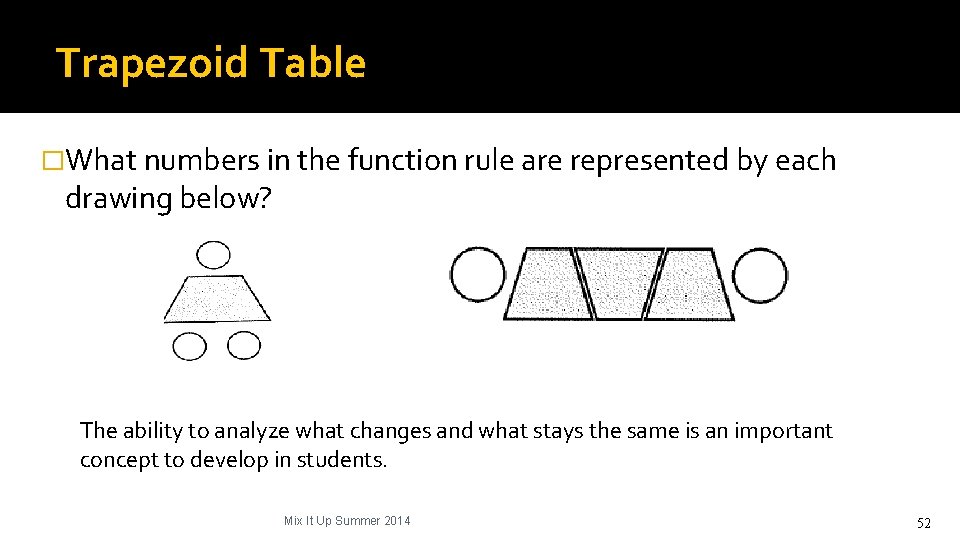

Trapezoid Table - perimeter � A restaurant has trapezoidal tables which seat five people. Mix It Up Summer 2014 � If 2 tables are placed together as shown to form one table, how many people can be seated? � Using counters and the trapezoidal pattern blocks, create a concrete representation of this problem for 5 tables 50

Trapezoidal Table �On chart paper with four- quadrant fold, illustrate your pattern With a drawing With a table A graph With a function (rule) With a verbal description Mix It Up Summer 2014 � The pattern that emerged is arithmetic sequence. The numbers in the sequence begin 5, 8, 11, . . � To find the number of people that can sit at 20 tables, use what function (rule)? 51

Trapezoid Table �What numbers in the function rule are represented by each drawing below? The ability to analyze what changes and what stays the same is an important concept to develop in students. Mix It Up Summer 2014 52

Trapezoid Table �Think about classroom practice. What is the role of the teacher when a task such as the Trapezoid Table is being solved? What is the role of the students? Who is responsible for representing the ideas? Are children given time and opportunity to represent their own thinking (metacognition)? Are multiple representations shared and discussed publicly? Mix It Up Summer 2014 53

The Importance of Tables � As children record numbers in tables, begin to develop idea of correspondence between the numbers � They attend to where the numbers go in the table and the meanings embodied in the position of the numbers � Learn certain #’s go in 1 st column and certain # go in 2 nd column � Helps them visually and cognitively look across columns and keep track of two numbers simultaneously-an important step in functional thinking � K-1 teacher may record � G 2 -3 students begin to record � G 4 -5 students record on t-table Mix It Up Summer 2014 54

Activities �For your assigned activities Work activity as a student Determine Geometric Habit(s) of Mind involved in the activity Create a poster illustrating ▪ ▪ ▪ the activities, the solutions, multiple representations (if possible) the TEKS and the GHOM Mix It Up Summer 2014 55

�STOPPED HERE �REST NOT READY FOR MIX �Next activity-diagonals of polygons �Then fixed area �Then pattern blocks similarity ? ? ? Mix It Up Summer 2014 56

What we do and what we do not do… �Sometimes we attempt to inform by explanation, but this is useless. Students should learn by doing, not be informed by explanation. �The teacher must give guidance to the process of learning, allowing students to discuss their orientations and by having them find their way in the field of thinking. Mix It Up Summer 2014 57

Where Is This In Schools? � Activities are tiered so students first have exposure to shapes, begin sorting them visually, and then talk about properties they see. � As students progress, geometry becomes more abstract. � Research indicates that students may enter high school at Level 0 or 1; thus, they have great difficulty with formal proofs. � Definitions progress to only contain necessary information. Mix It Up Summer 2014 58

Where Is This In Schools? � Many textbooks are written with only the integration phase which often coincides with the objective of the learning. � Many teachers begin their teaching with this phase, a. k. a. “direct teaching. ” Many teachers do not realize that their information cannot be understood by their pupils. � Many teachers start instruction with revealing what students should discover through an activity. � Teachers modeling correct use of terminology is essential, but often present a definition to students rather than letting them discover it. Mix It Up Summer 2014 59

Implications for Teaching � The traditional form of teaching, by modeling and explanation, is time- efficient but not effective. � Students will have a firm grasp of geometry if they are allowed to “play” with the ideas and arrive at own conclusions. � Whole group discussion is important in clearing up misconceptions and presents alternate observations and understandings. Mix It Up Summer 2014 60

Implications for Teaching � The more teachers know about a subject and the way students learn, the more effective they will be. Research indicates teacher content knowledge is low and there needs to be increased research in explaining student cognition in geometry � Difficulty in assigning van Hiele level. Many students are between levels or show two levels simultaneously, and they can be at different levels for different concepts. Some researchers argue for a continuum of attainment from one level to another on a specific concept. Mix It Up Summer 2014 61

Activities �For the activities Work activity as a student Determine Geometric Habit(s) of Mind Determine van Hiele level Mix It Up Summer 2014 62

Questioning Mix It Up Summer 2014 63

The Value of Questioning Not all questions challenge children’s thinking. Think about the kinds of questions you ask your students. What do they require of students? Do they call for students to simply recall number facts or perform computations? �Or do they call for students to analyze information, to build arguments, and to explain their reasoning? • Mix It Up Summer 2014 64

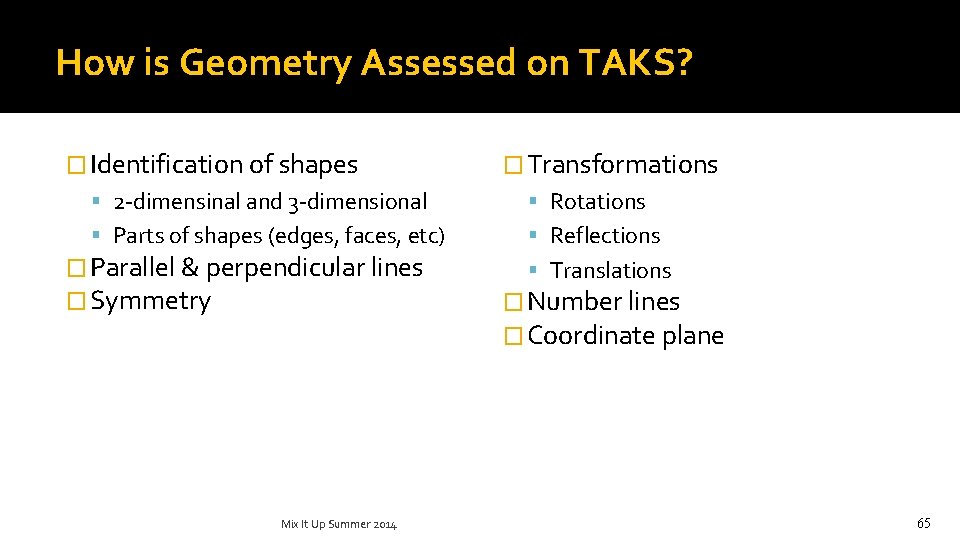

How is Geometry Assessed on TAKS? � Identification of shapes � Transformations 2 -dimensinal and 3 -dimensional Rotations Parts of shapes (edges, faces, etc) Reflections � Parallel & perpendicular lines � Symmetry Mix It Up Summer 2014 Translations � Number lines � Coordinate plane 65

What about STAAR? �Handout Mix It Up Summer 2014 66

Next Steps How can you use what you have learned about van Hiele levels to improve the teaching and learning of geometry in your class? Mix It Up Summer 2014 67

Patterns �Recognizing and using is critical to human thinking ability �Relate to expectations and predictions �Fundamental skill for algebraic thinking �Algebraic thinking involves finding and using patterns to generalize �Generalizing is goal of algebraic thinking Mix It Up Summer 2014 68

Types of Patterns Repeating patterns often focus of early childhood program, very common type of pattern o An attribute (color, shape, position, quantity, or texture) repeated over and over again o Frequently given the labels aab or ab to represent the simplest patterns Ø Growing (or additive) patterns more complicated o Change from one value to another in a predictable way o Example: 2, 5, 8, 11, … o Example: 1, 2, 4, 7, 11, … o Important for young children to analyze o Lead to more interesting studies in mathematics o Foundational to the study of functions Ø Mix It Up Summer 2014 69

Why is Algebraic Thinking Important? Algebraic thinking and content demand attention. Algebraic thinking increases flexibility in thinking. Algebraic thinking develops perseverance and tolerance for new ideas. Algebraic thinking creates self-confidence. Mix It Up Summer 2014 70

Algebraic Thinking Fostered by Questioning �Understanding progressions in children’s functional thinking across grades �Teacher learning - developing “algebra eyes and ears” �Teachers model algebraic thinking in think-alouds �Ask a variety of questions (ex: Can you explain what the 3 and 5 represent in that problem? ) Mix It Up Summer 2014 71

Good Questions to Ask ■ Does anyone have a conjecture to share? ■ How did you model the problem? ■ How did you represent your thinking? ■ Why did you use this particular representation? How did it help you find the solution? ■ What strategy did you use? ■ How did you get your solution? ■ What does the n stand for in your relationship? Mix It Up Summer 2014 ■ Marta, do you agree with Jack? Why? ■ Did anybody get a different solution? ■ How are your ideas different? ■ Is there a better way to organize the information? ■ Would you use a different argument to convince your friends than to convince the teacher? Why? 72

Generalization: Goal of Algebraic Thinking �The central goal of algebraic thinking To get children to think about, describe, and justify what is going on in general with regard to some mathematical situation. �Children should be able to develop a generalization, a statement that describes a general mathematical truth about some set of data. �Three instructional goals —represent, question, and listen—are all critical components in helping children build their own generalizations. Mix It Up Summer 2014 73

Thinking Back… � What did we do during this lesson? � If an outsider had walked into the room during this lesson, what observations could he/she have made? What did he see? What did he hear? Where were the learners located and what were they doing? Where was the teacher located and what was he/she doing? � As a learner, were you engaged during this activity? How do you know? What evidence do you have that others were engaged? Mix It Up Summer 2014 74

Algebraic Habits of Mind �How did this activity address the three algebraic habits of mind 1) Doing-undoing: undo mathematical processes as well do them, 2) Building rules to represent functions: recognize a pattern and organize data in situations where input is related to output 3) Abstracting from computation: think about computations independently of particular numbers Mix It Up Summer 2014 75

Four important instructional goals to help children think algebraically… ■ Question: Ask questions that encourage children to think algebraically. ■ Listen: Listen to and build on children’s thinking. ■ Represent: Provide multiple ways for children to systematically represent algebraic situations. ■ Generalize: Help children develop and justify their own generalizations. Mix It Up Summer 2014 76

Generalizations � Final stage in algebraic thinking - focusing attention on what has been created (a generalization) and its final form of expression, whether words or symbols. � Children should view building a generalization as an important mathematical activity. � It is at the heart of algebraic thinking. Show them you value their work— decorate your walls with the generalizations they build! Mix It Up Summer 2014 77

Integrating algebraic thinking into arithmetic already teaching � Look for arithmetic properties to generalize � Design computational problems that lead to generalizations � Generalize about sums and products of evens and odds � Make known quantities unknown by removing information � Symbolize and solve missing number sentences Mix It Up Summer 2014 78

Algebraic Habits of Mind � Connections facilitate the move from concrete to abstract, enabling students to reason algebraically. � Three “Algebraic Habits of Mind” (Driscoll, 1999) building rules to represent functions doing-undoing abstracting from computation Mix It Up Summer 2014 79

Why is Algebraic Thinking Important? ØAlgebraic thinking and content demand attention. ØAlgebraic thinking increases flexibility in thinking. ØAlgebraic thinking develops perseverance and tolerance for new ideas. ØAlgebraic thinking creates self-confidence. Mix It Up Summer 2014 80

Algebraic Thinking Fostered by Questioning �Understanding progressions in children’s functional thinking across grades �Teacher learning - developing “algebra eyes and ears” �Teachers model algebraic thinking in think-alouds �Ask a variety of questions (ex: Can you explain what the 3 and 5 represent in that problem? ) Mix It Up Summer 2014 81

Algebraic Thinking Fostered by Listening �Listening is just as important as questioning. It helps you understand children’s thinking, and you can use this knowledge to guide your instruction. If you are listening, then children are talking and— more likely—actively engaged in their learning. �Whether students are solving an elaborate task or simply reviewing solutions to homework problems, listen to their ideas, strategies, and reasoning and think about how you can extend their algebraic thinking. Mix It Up Summer 2014 82

Habits of Mind �How did this activity address the three algebraic habits of mind 1) Doing-undoing: undo mathematical processes as well do them, 2) Building rules to represent functions: recognize a pattern and organize data in situations where input is related to output 3) Abstracting from computation: think about computations independently of particular numbers Mix It Up Summer 2014 83

The Value of Questioning Not all questions challenge children’s thinking. Think about the kinds of questions you write in your lesson plans. • What do they require of students? • Do they call for students to simply recall number facts or perform computations? �Or do they call for students to analyze information, to build arguments, and to explain their reasoning? Mix It Up Summer 2014 84

What we do and what we do not do… �It is customary to illustrate newly introduced technical language with a few examples. �If the examples are deficient, the technical language will be deficient. �We often neglect the importance of the third stage, explicitation. Discussion helps clear out misconceptions and cements understanding. Mix It Up Summer 2014 85

What we do and what we do not do… �Sometimes we attempt to inform by explanation, but this is useless. Students should learn by doing, not be informed by explanation. �The teacher must give guidance to the process of learning, allowing students to discuss their orientations and by having them find their way in the field of thinking. Mix It Up Summer 2014 86

Consequences �Many textbooks are written with only the integration phase in place. �The integration phase often coincides with the objective of the learning. �Many teachers switch to, or even begin, their teaching with this phase, a. k. a. “direct teaching. ” �Many teachers do not realize that their information cannot be understood by their pupils. Mix It Up Summer 2014 87

Constructing Understanding î “Children’s learning always involves CONSTRUCTING ideas and systems. ” î “Kids need encouragement to reflect, to share their emerging ideas and hypotheses with others, to have their errors and temporary understandings respected – and they need plenty of time. ” Zemelman & Hyde. (1998). Best Practices: New Standards for Teaching and Learning in America’s Schools, p. 15. Mix It Up Summer 2014 88

Measurement MOVE TO MORNING WITH PATTI �A comparison of an attribute of an item with a unit having the same attribute �Understanding measurement depends on familiarity with unit used through hands-on opportunities to measure �Estimating and conceptualizing benchmarks used frequently help develop understanding �Earliest experiences focus on hands-on opportunities Mix It Up Summer 2014 89

Measurement � Must understand how measurement instruments work to be used correctly and meaningfully � Area and volume formulas provide method for measuring these attributes by measuring length � Area, perimeter, and volume are related to each other. Example – changing one dimension may effect the perimeter, area, or volume of an item Mix It Up Summer 2014 90

Measurement in school �Usually say to “measure” is to Fill Cover Match �In other words, to measure is to count the number of units needed to fill, cover, or match the attribute being measured Mix It Up Summer 2014 91

Steps to measure 1) 2) 3) Decide the attribute to be measured Select a unit that has the same attribute Compare the units with the item being measured by filling covering, or matching Mix It Up Summer 2014 92

Developing Measurement Concepts-making comparisons �Goal one: students will understand the attribute to be measured Type of activity-Make comparisons based on attribute; ex, longer/shorter, heavier/lighter Once clear that attribute is understood, no further need for comparison activities Grade 3 -5 students may understand length and perhaps weight and volume • Area still difficult for grades 3 -5 • Mix It Up Summer 2014 93

Developing Measurement Concepts-using models of units � Goal two: students will understand how filling, covering, matching with measuring units produces a number called a measure Type of activity-use physical models of measuring units to fill, cover, or match with the measuring unit ▪ Time, temperature no model Begin with nonstandard units (paper clips, tiles, etc) Progress to standard units (Formulas should not be used at this stage) � Make no assumptions about what students may know Mix It Up Summer 2014 94

Developing Measurement Concepts-making/using instruments �Goal three: students will use common measuring tools with understanding and flexibility �Type of make measuring instruments, use to compare with unit models Directly compare student-made tools and standard tools ▪ Student made tools best with informal units Mix It Up Summer 2014 95

Approximate nature of measurement �No measurement is exact �In all measuring activities, emphasize the use of the word approximate �Smaller units are more precise, but not exact Mix It Up Summer 2014 96

Area �How much it takes to cover a region �Difficult for children to understand Ex: Long skinny rectangle may have less area than a triangle with shorter sides Mix It Up Summer 2014 97

Area �Many 8 or 9 year olds do not understand that rearranging the area into different shapes does not affect the amount of area �Comparison activities help with this What is meant by comparison activities? Mix It Up Summer 2014 98

Warning about formulas � Filling many shapes with manipulatives to find the area has almost no impact on students understanding of formulas such L x W for determining area. Why? ? � Filling does not focus on the dimensions or multiplying � Goal of filling is to understand the meaning of measuring area � Once this goal met, move on to other activities to connect rows and columns to area Mix It Up Summer 2014 99

Focus on Algebraic Thinking �Algebra I considered “gate-keeper” �What does that mean? �Failure rate of grade 9 students statewide Mix It Up Summer 2014 100

Algebraic Habits of Mind �Connections facilitate the move from concrete to abstract, enabling students to reason algebraically. �Three “Algebraic Habits of Mind” (Driscoll, 1999) building rules to represent functions doing-undoing abstracting from computation �We will discuss and describe these habits throughout this workshop Mix It Up Summer 2014 101

Algebraic Habits of Mind Doing-undoing: ability to undo mathematical processes as well do them, to work backwards from the answer to the starting point (ex: 4+? =6) 2) Building rules to represent functions: ability to recognize a pattern and organize data in situations where input is related to output (ex: the rule is add 1) 3) Abstracting from computation: ability to think about computations independently of particular numbers(ex: grouping numbers to add quickly) 1) Mix It Up Summer 2014 102

Patterns �Recognizing and using is critical to human thinking ability �Relate to expectations and predictions �Useful for predicting �Fundamental skill for algebraic thinking �Analyze what changes, what stays constant Rate of change Mix It Up Summer 2014 103

Thinking Back… � What did we do during this lesson? � If an outsider had walked into the room during this lesson, what observations could he/she have made? What did he see? What did he hear? Where were the learners located and what were they doing? Where was the teacher located and what was he/she doing? � As a learner, were you engaged during this activity? How do you know? What evidence do you have that others were engaged? Mix It Up Summer 2014 104

Habits of Mind �How did this activity address the three algebraic habits of mind 1) Doing-undoing: undo mathematical processes as well do them, 2) Building rules to represent functions: recognize a pattern and organize data in situations where input is related to output 3) Abstracting from computation: think about computations independently of particular numbers Mix It Up Summer 2014 105

Trapezoid Table �Think about your classroom practice. What is your role as teacher when a task such as the Trapezoid Table is being solved? What is the role of your students? Who is responsible for representing the ideas? Are students given time and opportunity to represent their own thinking? Are multiple representations shared and discussed publicly? Mix It Up Summer 2014 106

Student Displays • Public record helps student remember the generalizations made, they can more easily build on these ideas. That is, they can use generalizations already established to build justifications for other conjectures. Mix It Up Summer 2014 107

Representation-the process of representing an idea and the product, or result, of that process � Present information at three levels Concrete – manipulatives Pictorial – drawings, charts, graph Abstract – number sentences Mix It Up Summer 2014 � Representations can take many forms Oral or written words, symbols, pictures, diagrams, tables, graphs or tactile forms with manipulatives 108

As teach, consider … �What important ideas do I want to address in an activity? �What long-term algebraic learning goals does this activity relate to? �Which features of the three algebraic habits of mind do I want this activity to elicit from my students? Mix It Up Summer 2014 109

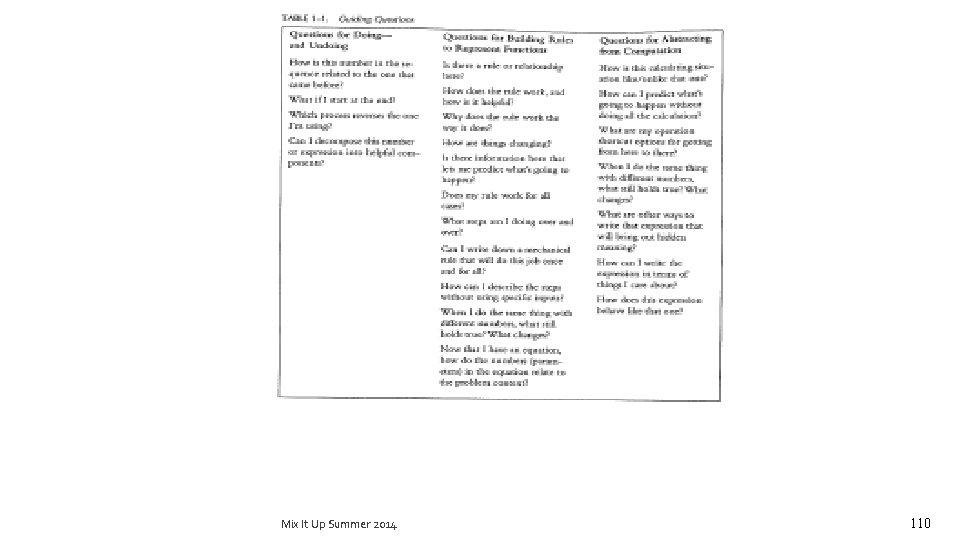

Mix It Up Summer 2014 110

Questions �For the Trapezoidal Table Problem List 2 or 3 questions that a teacher should ask that would encourage students to develop each of the three habits of algebraic thinking ▪ Doing-undoing ▪ Abstracting from computation ▪ Building rules to represent functions Mix It Up Summer 2014 111

Focus on Functions �In Texas, the Algebra TEKS are function based �Describe how two (or more) quantities are related �Understanding the relationship begins in Kindergarten �Many times represented by tables and graphs �Example: number of eyes that 7 dogs have Mix It Up Summer 2014 112

Habits of Mind �How did this activity address the three algebraic habits of mind 1) Doing-undoing: undo mathematical processes as well do them, 2) Building rules to represent functions: recognize a pattern and organize data in situations where input is related to output 3) Abstracting from computation: think about computations independently of particular numbers Mix It Up Summer 2014 113

As teach, consider … �What important ideas do I want to address in an activity? �What long-term algebraic learning goals does this activity relate to? �Which features of the three algebraic habits of mind do I want this activity to elicit from my students? �What questions will I ask to ensure that my goals are met? Mix It Up Summer 2014 114

To elicit algebraic thinking …. �What process reverses the one you are using? �How does the rule work? �How are things changing? �What things stay the same? �Is there information that helps you predict what is happening? �What operation could you use to get from here to there? �When you do the same thing with different numbers, what still holds true? Mix It Up Summer 2014 115

Thinking Back… � What did we do during these activities? � If an outsider had walked into the room during these activities, what observations could he/she have made? What did he see? What did he hear? Where were the learners located and what were they doing? Where was the teacher located and what was he/she doing? � As a learner, were you engaged during these activities? How do you know? What evidence do you have that others were engaged? Mix It Up Summer 2014 116

Algebraic Thinking Fostered by Questioning �Understanding progressions in students’ functional thinking across grades �Teacher learning - developing “algebra eyes and ears” �Teachers model algebraic thinking in think-alouds �Ask a variety of questions (ex: Can you explain what the 3 and 5 represent in that problem? ) Mix It Up Summer 2014 117

Representations �As you encourage your students to develop and use multiple representations, help them build connections across these representations so that they can transition from concrete to more abstract ways of thinking. �“Seeing similarities in the ways to represent different situations is an important step toward abstraction” (NCTM 2000, 138). Mix It Up Summer 2014 118

Generalization: Goal of Algebraic Thinking �The central goal of algebraic thinking To get students to think about, describe, and justify what is going on in general with regard to some mathematical situation. �Students should develop a generalization, a statement that describes a general mathematical truth about some set of data. �Three instructional goals —represent, question, and listen—are all critical components in helping students build their own generalizations. Mix It Up Summer 2014 119

TAKS / STAAR �How do rich questions prepare students for the TAKS and the coming STAAR? �Let’s look at Surveys of Enacted Curriculum Mix It Up Summer 2014 120

STAAR �What are the implications of the SEC and STAAR? �With table mates, discuss STAAR information. �How can teachers increase the rigor of activities to prepare students for rigor of STAAR Mix It Up Summer 2014 121

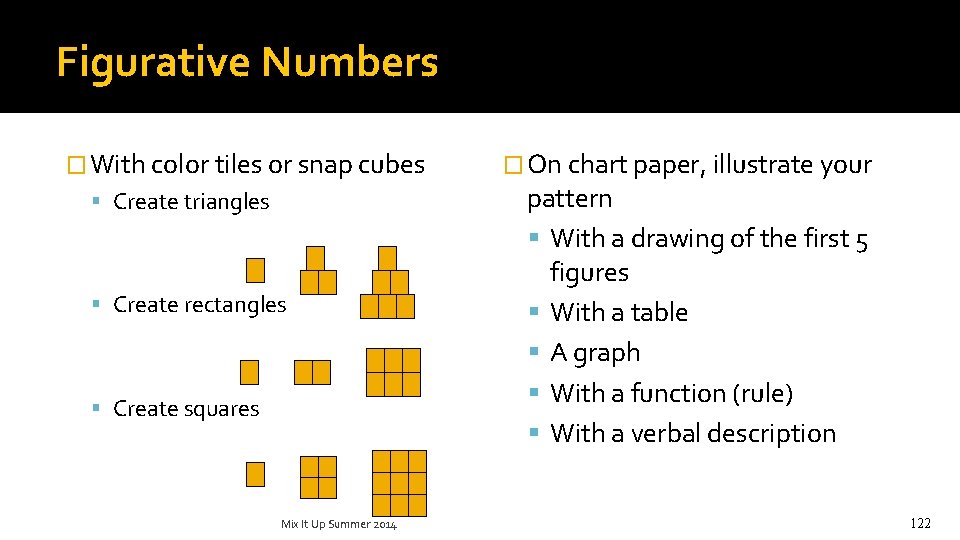

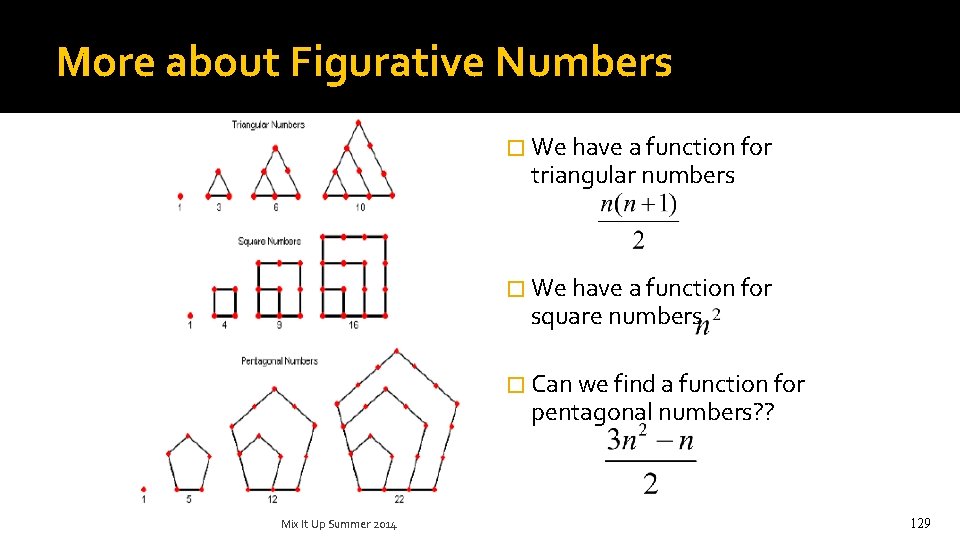

Figurative Numbers � With color tiles or snap cubes Create triangles Create rectangles Create squares Mix It Up Summer 2014 � On chart paper, illustrate your pattern With a drawing of the first 5 figures With a table A graph With a function (rule) With a verbal description 122

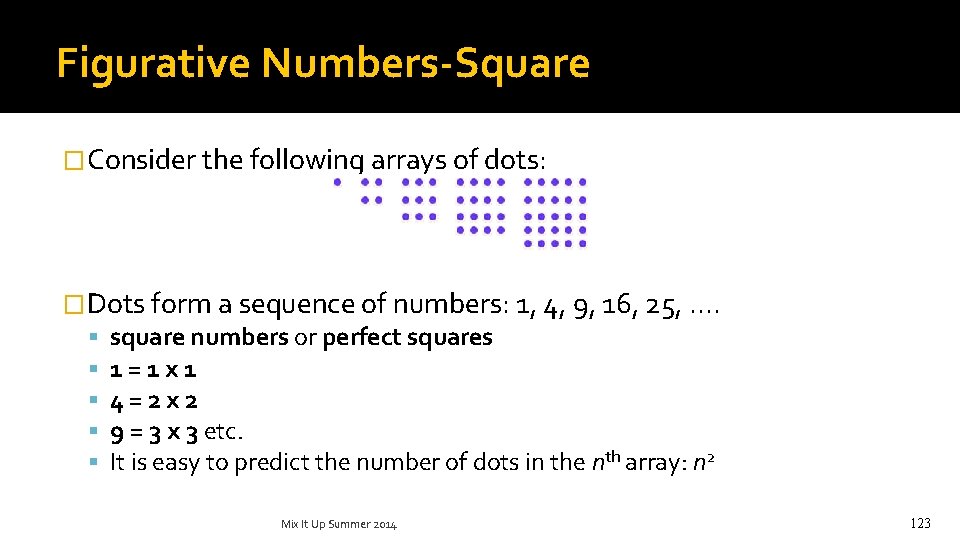

Figurative Numbers-Square �Consider the following arrays of dots: �Dots form a sequence of numbers: 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, . . square numbers or perfect squares 1=1 x 1 4=2 x 2 9 = 3 x 3 etc. It is easy to predict the number of dots in the nth array: n 2 Mix It Up Summer 2014 123

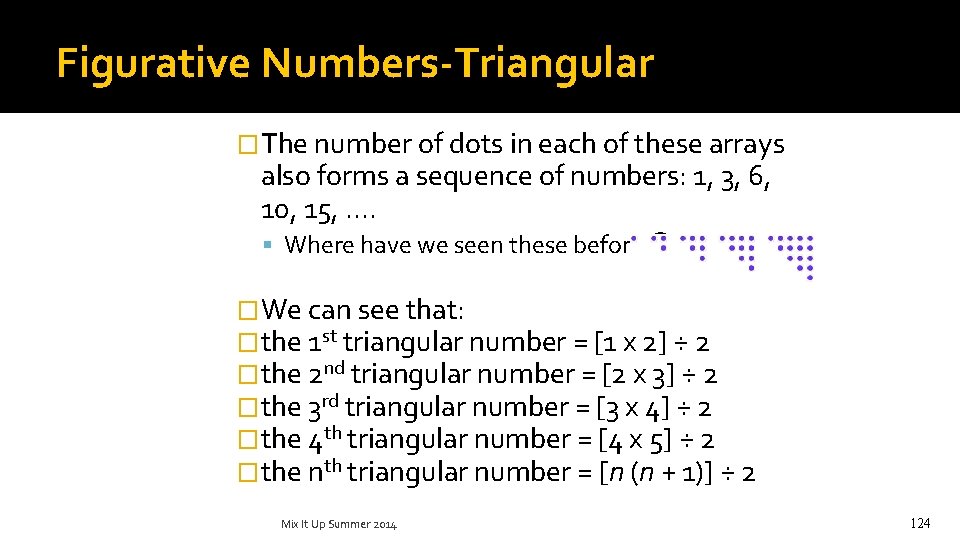

Figurative Numbers-Triangular �The number of dots in each of these arrays also forms a sequence of numbers: 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, . . Where have we seen these before �We can see that: �the 1 st triangular number = [1 x 2] ÷ 2 �the 2 nd triangular number = [2 x 3] ÷ 2 �the 3 rd triangular number = [3 x 4] ÷ 2 �the 4 th triangular number = [4 x 5] ÷ 2 �the nth triangular number = [n (n + 1)] ÷ 2 Mix It Up Summer 2014 124

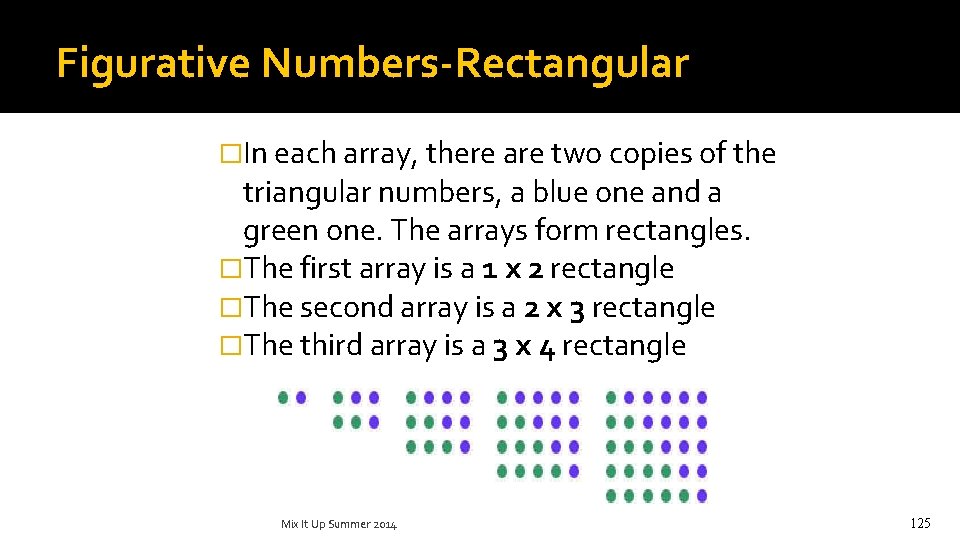

Figurative Numbers-Rectangular �In each array, there are two copies of the triangular numbers, a blue one and a green one. The arrays form rectangles. �The first array is a 1 x 2 rectangle �The second array is a 2 x 3 rectangle �The third array is a 3 x 4 rectangle Mix It Up Summer 2014 125

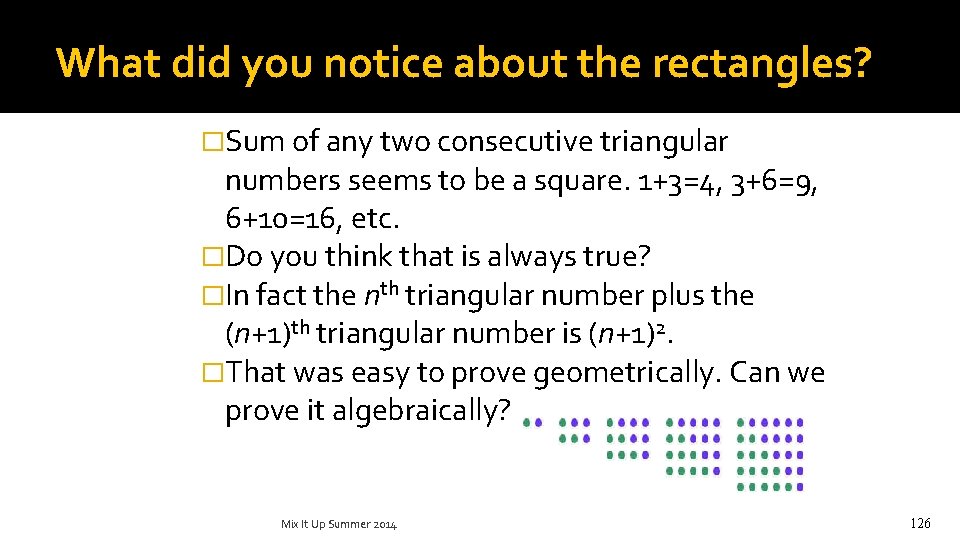

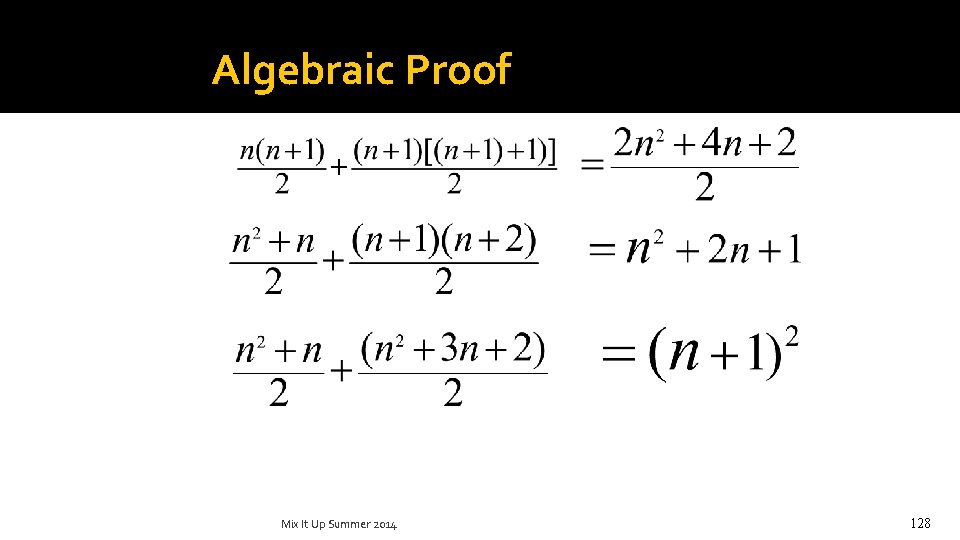

What did you notice about the rectangles? �Sum of any two consecutive triangular numbers seems to be a square. 1+3=4, 3+6=9, 6+10=16, etc. �Do you think that is always true? �In fact the nth triangular number plus the (n+1)th triangular number is (n+1)2. �That was easy to prove geometrically. Can we prove it algebraically? Mix It Up Summer 2014 126

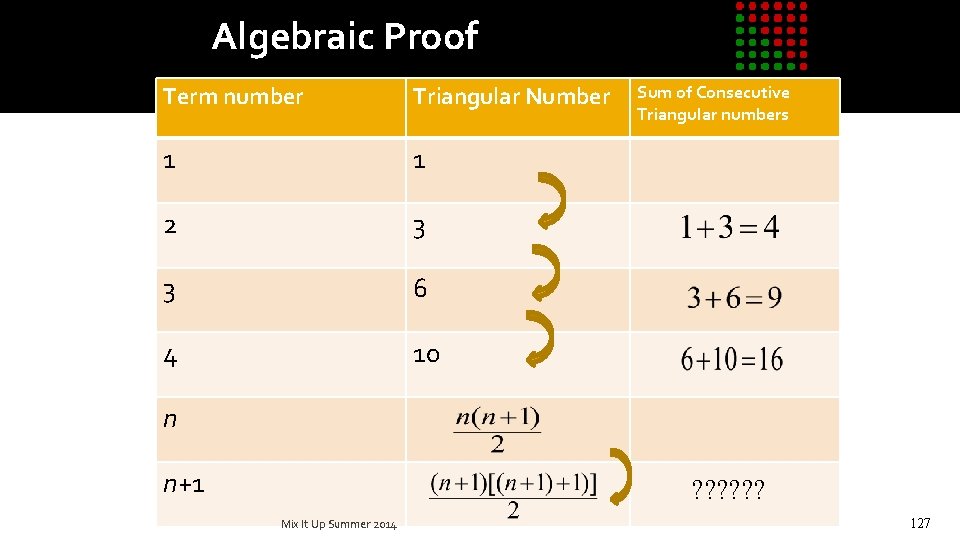

Algebraic Proof Term number Triangular Number 1 1 2 3 3 6 4 10 Sum of Consecutive Triangular numbers n n+1 ? ? ? Mix It Up Summer 2014 127

Algebraic Proof Mix It Up Summer 2014 128

More about Figurative Numbers � We have a function for triangular numbers � We have a function for square numbers � Can we find a function for pentagonal numbers? ? Mix It Up Summer 2014 129

Representation-the process of representing an idea and the product, or result, of that process � Present information at three levels Concrete – manipulatives Pictorial – drawings, charts, graph Abstract – number sentences Mix It Up Summer 2014 � Representations can take many forms Oral or written words, symbols, pictures, diagrams, tables, graphs or tactile forms with manipulatives 130

Function-Based Algebra • In Texas, the Algebra TEKS are function based • Describe how two (or more) quantities are related • Understanding the relationship begins in Kindergarten • Many times represented by tables and graphs • Example: number of eyes that 7 dogs have Mix It Up Summer 2014 131

Algebraic Thinking � Students use language to describe informal generalizations and connect symbols to the language, a process which produces formal (algebraic) generalizations the language component is critical - students are required to articulate their own movement from concrete to abstract � Abstractions – writing a linear function rule for a real- world situation, for example – become concrete enabling students to then access higher levels of abstraction � The TEKS for mathematics require building and making connections among concrete, verbal, numeric, graphic, and symbolic representations of relationships between quantities Mix It Up Summer 2014 132

Ultimate Goal The goal is for teaching to focus on �Students’ ideas, their reasoning, their representations, their conjectures, �their arguments, their generalizations—in short, their algebraic thinking. �To give mathematical—algebraic—purpose to explorations through the type of tasks chosen and the questions asked Mix It Up Summer 2014 133

Thinking Back… � What did we do during this lesson? � If an outsider had walked into the room during this lesson, what observations could he/she have made? What did he see? What did he hear? Where were the learners located and what were they doing? Where was the teacher located and what was he/she doing? � As a learner, were you engaged during this activity? How do you know? What evidence do you have that others were engaged? Mix It Up Summer 2014 134

Habits of Mind �How did this activity address the three algebraic habits of mind 1) Doing-undoing: undo mathematical processes as well do them, 2) Building rules to represent functions: recognize a pattern and organize data in situations where input is related to output 3) Abstracting from computation: think about computations independently of particular numbers Mix It Up Summer 2014 135

Questions � List questions that a teacher could ask to elicit mathematical ideas and foster algebraic thinking in students. Questions that would orient the students’ thinking about or to a particular point Questions that clarify your understanding of students’ thinking Questions to encourage ▪ Doing-undoing ▪ Abstracting from computation ▪ Building rules to represent functions Mix It Up Summer 2014 136

Mix It Up Summer 2014 137

6 �Abstracting from computation, symbolic representation on 100 chart �Arrow Arithmetic Mix It Up Summer 2014 138

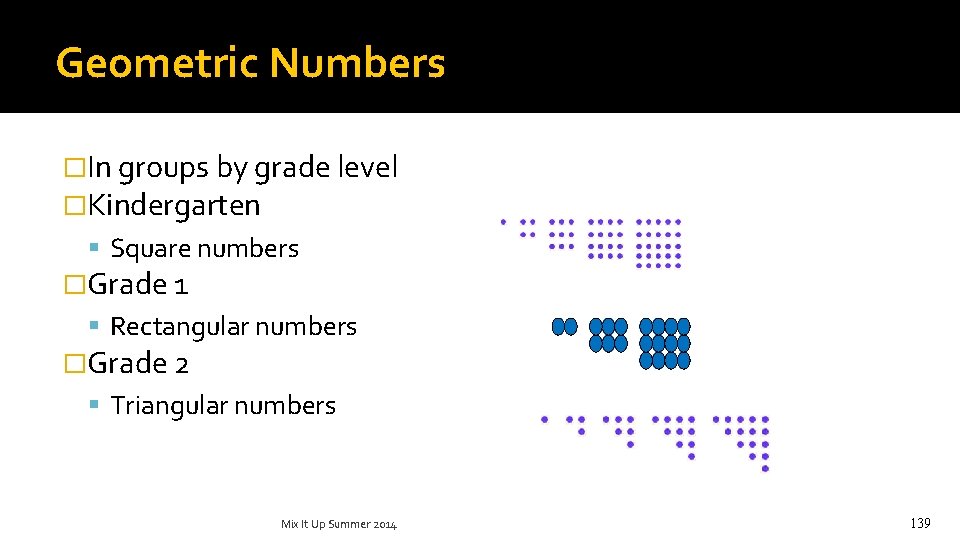

Geometric Numbers �In groups by grade level �Kindergarten Square numbers �Grade 1 Rectangular numbers �Grade 2 Triangular numbers Mix It Up Summer 2014 139

For your assigned activity �On chart paper, illustrate your pattern List all patterns that you see With a drawing With a t-table A graph With a function (rule) if possible With a verbal description �Share with group Mix It Up Summer 2014 140

Thinking Back… � What did we do during this lesson? � If an outsider had walked into the room during this lesson, what observations could he/she have made? What did he see? What did he hear? Where were the learners located and what were they doing? Where was the teacher located and what was he/she doing? � As a learner, were you engaged during this activity? How do you know? What evidence do you have that others were engaged? Mix It Up Summer 2014 141

Fundamental Components of Algebraic Thinking To think algebraically, one must be able to understand patterns, relations, and functions; represent and analyze mathematical situations and structures using algebraic symbols; use mathematical models to represent and understand quantitative relationships; and analyze change in various contexts. Each of these basic concepts evolves as students grow and mature. Navigating through Algebra, NCTM, Page 2 Mix It Up Summer 2014 142

- Slides: 142