MIND LECTURES 1 Philosophy of Mind The philosophy

- Slides: 55

MIND LECTURES 1

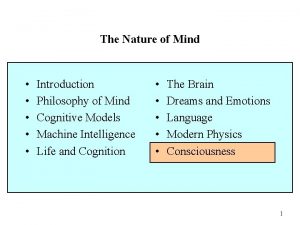

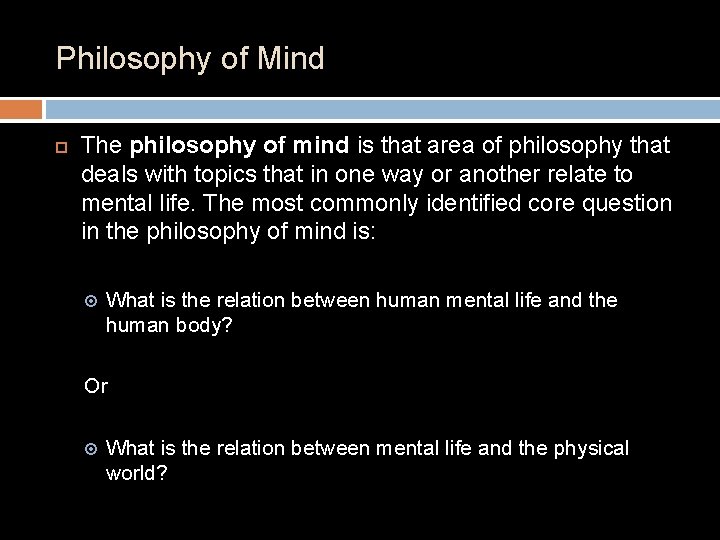

Philosophy of Mind The philosophy of mind is that area of philosophy that deals with topics that in one way or another relate to mental life. The most commonly identified core question in the philosophy of mind is: What is the relation between human mental life and the human body? Or What is the relation between mental life and the physical world?

The 20 th century shift The 20 th century began with the dominance of philosophy focused on language, logic, mathematics and epistemology. The philosophy of mind was largely seen as posterior to discussions of language and epistemology. Two shifts occurred in the philosophy of mind as the 20 th century developed. First, philosophy of mind became an interdisciplinary subject. Currently, it is impossible to study the philosophy of mind without knowing a great deal about: computer science, phenomenology, neuroscience, linguistics, cognitive science, traditional philosophy, and non-western philosophy, such as ancient Asian techniques of meditation. Second, language and epistemology are now seen to be less basic than philosophy of mind. Questions about how language works and how we know things are taken to be dependent in part on how the mind works. We now think of inquiring into the mind as a way of learning about language and knowledge.

Problems in the Philosophy of Mind The Problem of Other Minds 1. 2. 3. The mind ≠ body. A person can only perceive another person’s body. So, a person cannot perceive another person’s mind. Non-Solipsism Question: How do I know there are other minds out there at all? Non-Uniqueness Question: How do I know that my mind is not completely unique, even if there are other minds out there? Animal Question: Do non-human animals have minds like humans?

Problems in the Philosophy of Mind The Problem of Free Will 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. The mind = body. The body is governed by laws of nature. Either laws of nature are deterministic or indeterministic. If laws are deterministic, then there is no free will. If laws are indeterministic, then my actions are random. Illusion Question: Is freewill an illusion? Morality Question: How can there be moral responsibility without free will? Punishment Question: If our bodies are governed by deterministic laws, why are we punished? We could not have done otherwise.

Problems in the Philosophy of Mind The Problem of the Self and Personal Identity 1. 2. 3. 4. If the Self = my body, then what happens to my body also happens to me. My body undergoes physical change constantly. My Self does not undergo change constantly. So, the self ≠ the body. Continuity Question: If there is something I fundamentally am, what is that thing underlying me throughout all the changes my body and mind undergo? Responsibility Question: If there is no continual self, how is that I can be held responsible for something I did at an earlier time when that person is not around any longer?

Problems in the Philosophy of Mind The problem of Intentionality 1. 2. 3. Intentionality or aboutness is a pervasive component of human life and essential to understanding the human condition. Intentionality allows us to think at one location or refer from one location to something that is spatially distant or temporally distant from us. Some think that intentionality is the mark of mental phenomena. How is it that thoughts inside my head can reach out beyond my head and refer to something very distant in space and time? More generally, how is the phenomena of aboutness possible in a physical world?

Problems in the Philosophy of Mind Questions concerning emotion and rationality 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. What is an emotion? What is it to be rational? Are our actions guided by reason or by emotion, or by both? What is the specific analysis of an emotions, such as anger? Are there different kinds of rationality, such as practical vs. theoretical? Can reason influence emotion? Can emotion override reason?

Problems in the Philosophy of Mind Question concerning mind-reading? 1. 2. 3. 4. How do I know what another person is doing or trying to do? How does autism help us understand human mind-reading? What role do mirror-neurons play in explaining our understanding of another person’s behavior? What evidence can we use to decide between competing theories of mind-reading?

Problems in the Philosophy of Mind Questions concerning AI? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Can computers think? What criterion is appropriate for answering the question of whether computers can think? What can we learn about human cognition by studying ways in which we can program computers to learn? What are the moral boundaries of AI? Does mathematics provide a counterexample to the idea that computers can perform mental tasks equivalent to humans. Is the singularity coming? What does the singularity suggest about the nature of mindedness?

Problems in the Philosophy of Mind Questions on specific mental states: What is a belief? What is a desire? What is an intention? What is attention? What is perception? What is memory?

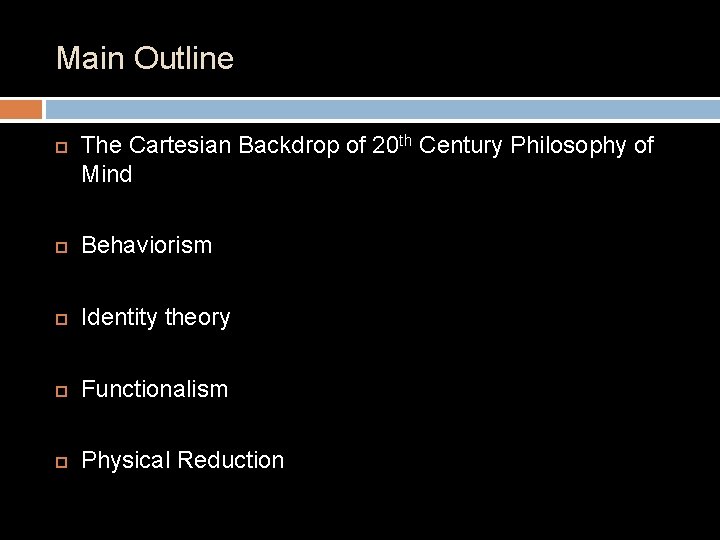

Main Outline The Cartesian Backdrop of 20 th Century Philosophy of Mind Behaviorism Identity theory Functionalism Physical Reduction

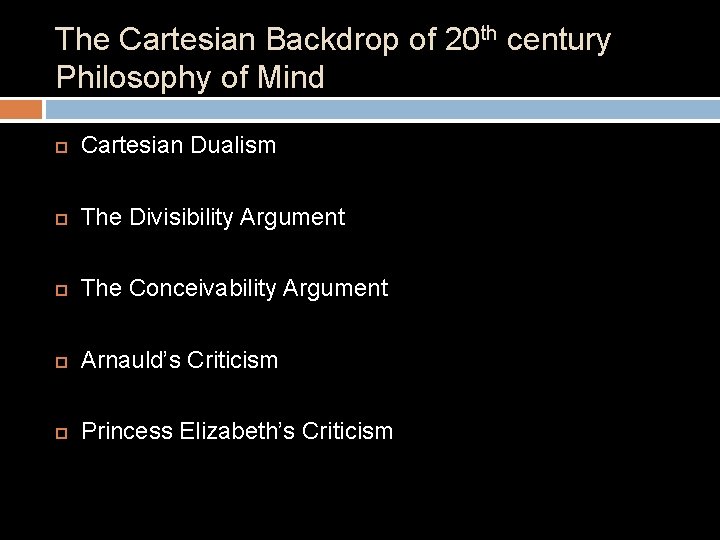

The Cartesian Backdrop of 20 th century Philosophy of Mind Cartesian Dualism The Divisibility Argument The Conceivability Argument Arnauld’s Criticism Princess Elizabeth’s Criticism

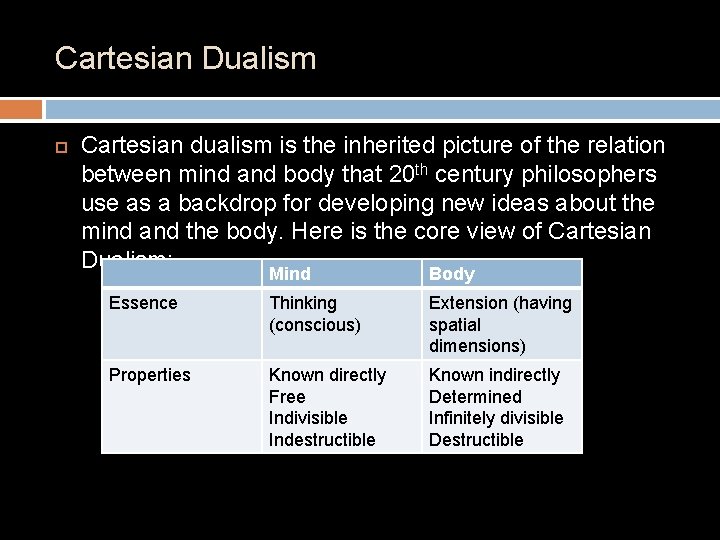

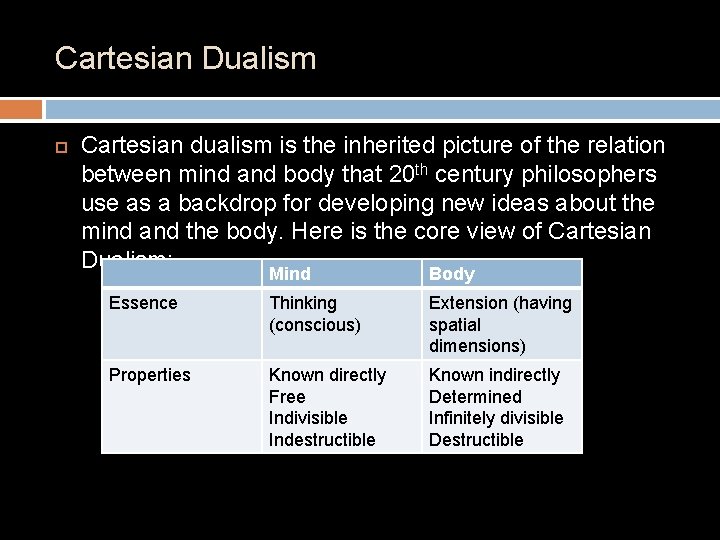

Cartesian Dualism Cartesian dualism is the inherited picture of the relation between mind and body that 20 th century philosophers use as a backdrop for developing new ideas about the mind and the body. Here is the core view of Cartesian Dualism: Mind Body Essence Thinking (conscious) Extension (having spatial dimensions) Properties Known directly Free Indivisible Indestructible Known indirectly Determined Infinitely divisible Destructible

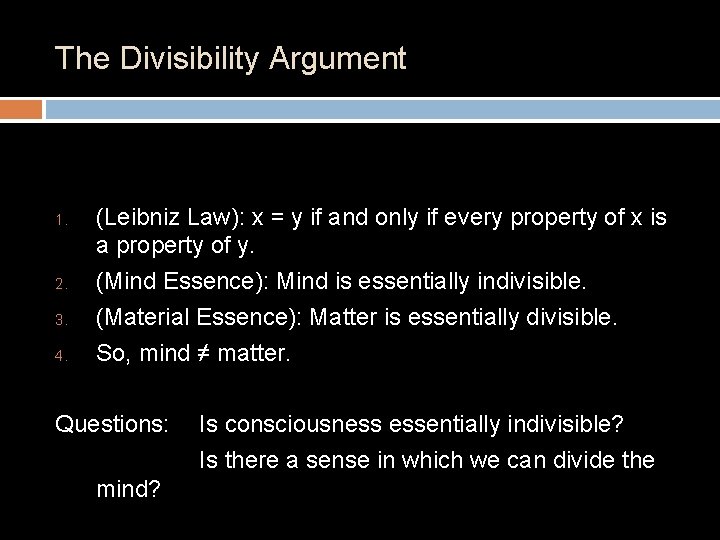

The Divisibility Argument 1. 2. 3. 4. (Leibniz Law): x = y if and only if every property of x is a property of y. (Mind Essence): Mind is essentially indivisible. (Material Essence): Matter is essentially divisible. So, mind ≠ matter. Questions: mind? Is consciousness essentially indivisible? Is there a sense in which we can divide the

The Conceivability Argument 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. If I can conceive of my mind existing without my body, then it is possible for my mind to exist without my body. I can conceive of my mind existing without my body. So, it is possible for my mind to exist without my body. If it is possible for my mind to exist without my body, then my mind is not identical to my body. So, my mind is not identical to my body.

Arnauld’s Criticism Descartes’ assumes that if I can conceive x without y, then it is possible for x to exist without y. Arnauld challenges him with the following example: 1. 2. 3. A man ignorant of geometrical knowledge can conceive of a right triangle existing without having the Pythagorean property P. The reason why is because he may grasp that the triangle T has a 90 degree angle, but fail to see that it has the Pythagorean property P. However, it is impossible for T to exist without P. So, it is not true that if S can conceive x without y, it is possible for x to exist without y.

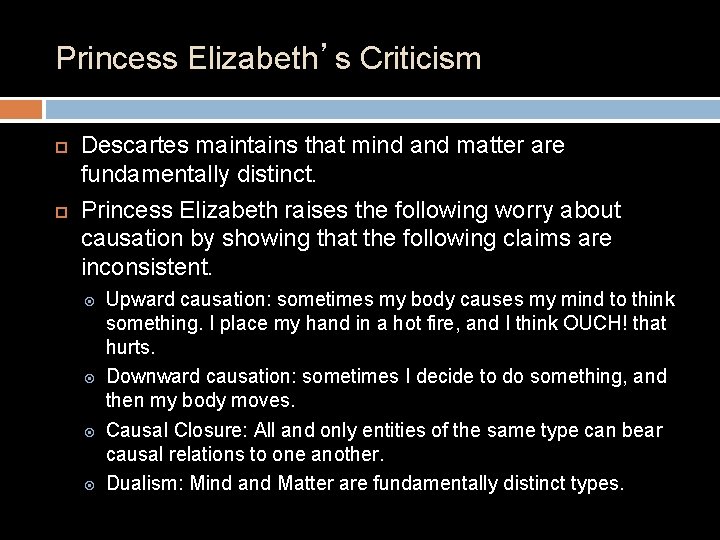

Princess Elizabeth’s Criticism Descartes maintains that mind and matter are fundamentally distinct. Princess Elizabeth raises the following worry about causation by showing that the following claims are inconsistent. Upward causation: sometimes my body causes my mind to think something. I place my hand in a hot fire, and I think OUCH! that hurts. Downward causation: sometimes I decide to do something, and then my body moves. Causal Closure: All and only entities of the same type can bear causal relations to one another. Dualism: Mind and Matter are fundamentally distinct types.

Behaviorism in the 20 th Century Wittgenstein’s Beetle in a Box Thought Experiment Ryle’s University Objection Logical vs. Methodological Behaviorism Mental States as Behavioral Dispositions Problems with Behavioral Dispositions

Wittgenstein’s Beetle in a Box I If I say of myself that it is only from my own case that I know what the word “pain” means – must I not say the same of other people too? And how can I generalize the one case so irresponsibly? Suppose everyone had a box with something in it: we call it a “beetle”. No one can look into anyone else’s box, and everyone says he knows what a beetle is only by looking at his beetle. – Here it would be quite possible for everyone to have something different in his box. One might even imagine such a thing constantly changing. – But suppose the word “beetle” had a use in these people’s language? – If so it would not be used as the name of a thing. The thing in the box has no place in the language-game at all; not even as a something: for the box might even be empty. –No, one can ‘divide through’ by the thing in the box; it cancels out, whatever it is. That it is to say: if we construe the grammar of the expression of sensation on the model of ‘object and designation’ the object drops out of consideration as irrelevant. – Philosophical Investigations 293

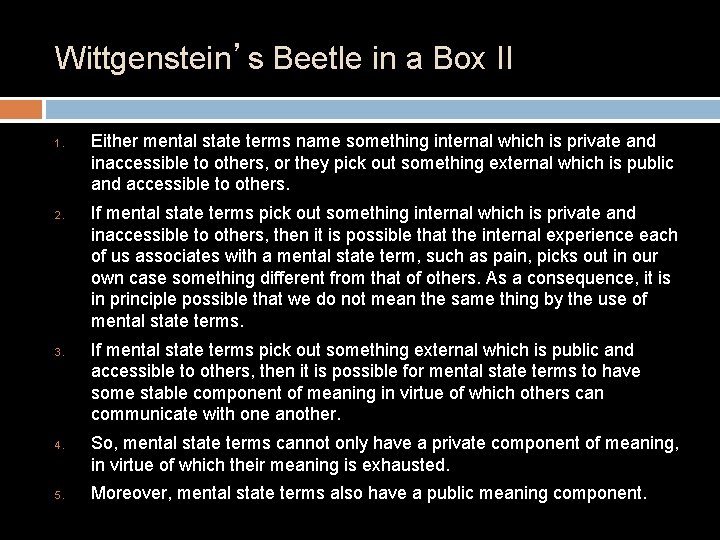

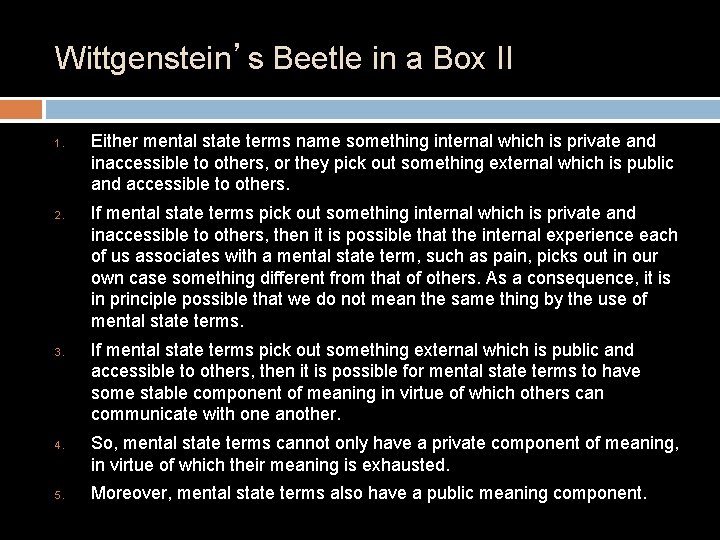

Wittgenstein’s Beetle in a Box II 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Either mental state terms name something internal which is private and inaccessible to others, or they pick out something external which is public and accessible to others. If mental state terms pick out something internal which is private and inaccessible to others, then it is possible that the internal experience each of us associates with a mental state term, such as pain, picks out in our own case something different from that of others. As a consequence, it is in principle possible that we do not mean the same thing by the use of mental state terms. If mental state terms pick out something external which is public and accessible to others, then it is possible for mental state terms to have some stable component of meaning in virtue of which others can communicate with one another. So, mental state terms cannot only have a private component of meaning, in virtue of which their meaning is exhausted. Moreover, mental state terms also have a public meaning component.

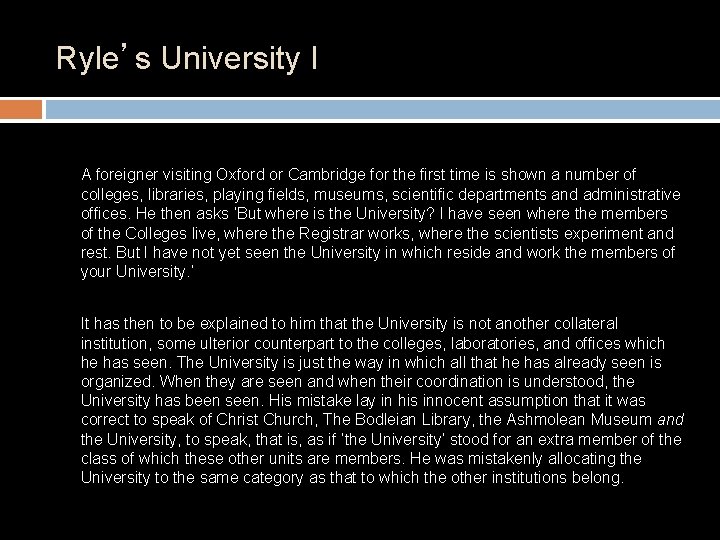

Ryle’s University I A foreigner visiting Oxford or Cambridge for the first time is shown a number of colleges, libraries, playing fields, museums, scientific departments and administrative offices. He then asks ‘But where is the University? I have seen where the members of the Colleges live, where the Registrar works, where the scientists experiment and rest. But I have not yet seen the University in which reside and work the members of your University. ’ It has then to be explained to him that the University is not another collateral institution, some ulterior counterpart to the colleges, laboratories, and offices which he has seen. The University is just the way in which all that he has already seen is organized. When they are seen and when their coordination is understood, the University has been seen. His mistake lay in his innocent assumption that it was correct to speak of Christ Church, The Bodleian Library, the Ashmolean Museum and the University, to speak, that is, as if ‘the University’ stood for an extra member of the class of which these other units are members. He was mistakenly allocating the University to the same category as that to which the other institutions belong.

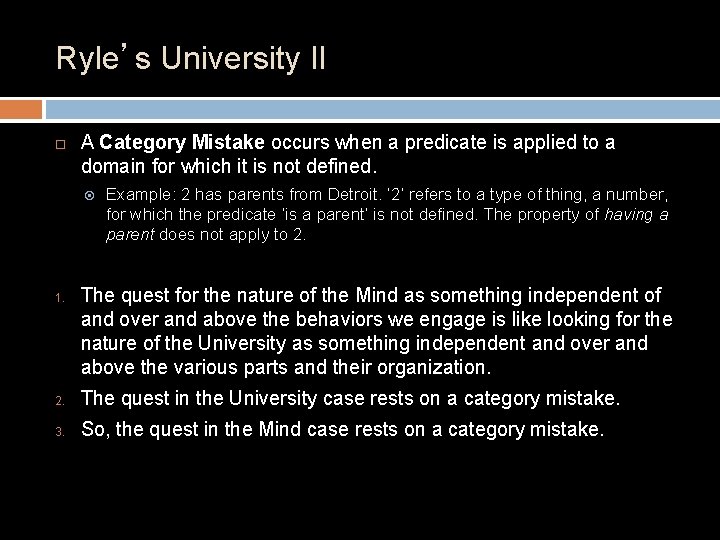

Ryle’s University II A Category Mistake occurs when a predicate is applied to a domain for which it is not defined. 1. Example: 2 has parents from Detroit. ‘ 2’ refers to a type of thing, a number, for which the predicate ‘is a parent’ is not defined. The property of having a parent does not apply to 2. The quest for the nature of the Mind as something independent of and over and above the behaviors we engage is like looking for the nature of the University as something independent and over and above the various parts and their organization. 2. The quest in the University case rests on a category mistake. 3. So, the quest in the Mind case rests on a category mistake.

Behaviorism I Dualism: When one listens attentively there is an internal focusing of one’s attention and a listening. The attention is a function of mind, and the listening is a function of bodily behavior. Behaviorism: ‘Listening Attentively’ is a unified act not composed of two distinct components involving conscious attentive focus, and bodily listening. All that is involved is listening attentively to whatever one is listening to.

Behaviorism II Behaviorism is the view that mental life is nothing over and above behavior. There are two different kinds of behaviorism: Logical behaviorism maintains that mental states under logical analysis just are behavioral states. Methodological behaviorism maintains that from a psychological standpoint behavior is all that matters for the study of the mind. Internal states are not objectively observable, and so, it is incorrect to try to deploy them in psychology.

Logical Behaviorism Mental states such, as Jones believes that it will rain, Jones hopes that it will rain, Jones desires that it rain, etc are ultimately logical shorthand for descriptions of behavior. ‘Jones believes that it will rain’ fundamentally means In situation C, Jones will do P 1 or P 2 or P 3…. or Pn. Mental states are analyzed as dispositions to behave in certain ways.

Problems for Behaviorism Circularity as a problem for behavioral dispositions Putnam’s Super-Spartans as a problem for behavioral dispositions Causation as a problem for behaviorism

Circularity as a problem for behavioral dispositions An analysis of mental states in terms of dispositions is successful only if the analysis is non-circular. Jones believes that it will rain if and only if were it to rain and he intended not to get wet, he would bring an umbrella. In the analysis of belief the notion of intention has shown up, so we don’t have a complete analysis of mental states in terms of pure behavior. Questions: Is it possible to give a non-circular analysis? Does the circularity matter?

Putnam’s Super-Spartans I Imagine a community of ‘Super-Spartans’ – a community in which the adults have the ability to successfully suppress all involuntary pain behavior. They may, on occasion, admit that they feel pain, but always in pleasant well-modulated voices –even if they are undergoing the agonies of the damned. They do not wince, scream, flinch, sob, grit their teeth, clench their fists, exhibit beads of sweat, or otherwise act like people in pain or people suppressing the unconditioned responses associated with pain. However, they do feel the pain, and dislike it (just as we do). They even admit that it takes a great effort of will to behave as they do. It is only that they have what they regard as important ideological reasons for behaving as they do, and they have, through years of training, learned to live up to their own exacting standards. --Brains and Behavior 1968

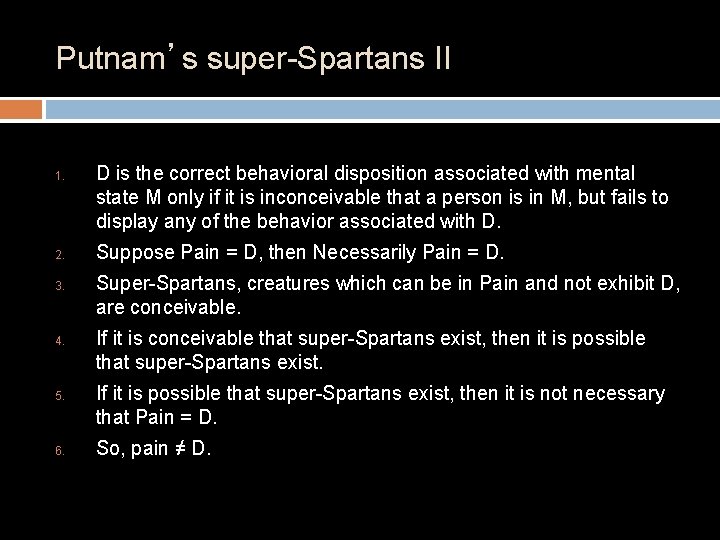

Putnam’s super-Spartans II 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. D is the correct behavioral disposition associated with mental state M only if it is inconceivable that a person is in M, but fails to display any of the behavior associated with D. Suppose Pain = D, then Necessarily Pain = D. Super-Spartans, creatures which can be in Pain and not exhibit D, are conceivable. If it is conceivable that super-Spartans exist, then it is possible that super-Spartans exist. If it is possible that super-Spartans exist, then it is not necessary that Pain = D. So, pain ≠ D.

Causation as a problem for behaviorism Behavior seems to be the effect of the will. As a consequence if our behavior is all that our mental life amounts to it would be hard to make sense of claims such as the following. Jones’s ran into the store because he believed it was going to rain and he didn’t want to get wet. In the claim above Jones’s beliefs and desire seem to play a causal role, so his beliefs and desires cannot just be behaviors.

Identity Theory Identity Theory: Type vs. Token Jackson’s Mary Thought Experiment Kripke’s argument against type identity theory Putnam’s argument against type identity theory

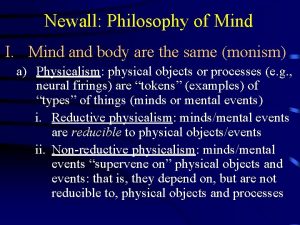

Identity Theory I Identity Theory is the view that mental states are nothing over and above brain processes. Pain = C-fiber stimulation No one takes seriously the idea that we have discovered exactly which brain states correlate with which mental states. So the example above is just an equation of sorts that is used to think about the view propounded by identity theory. The ‘is’ involved is one of strict numerical identity.

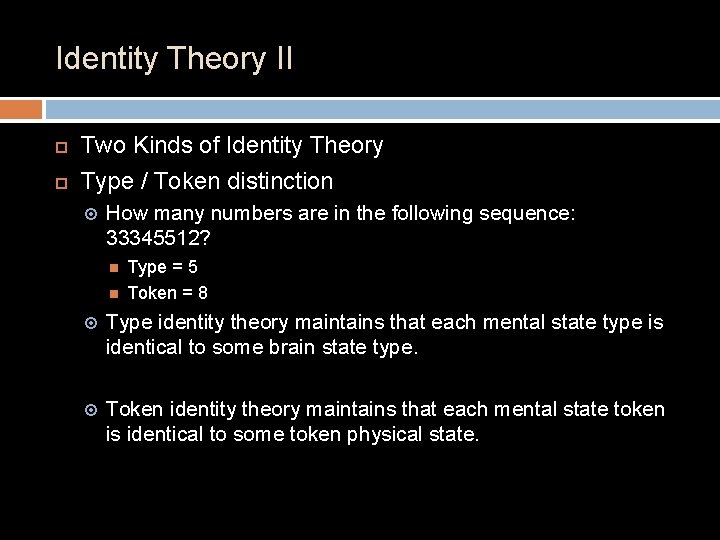

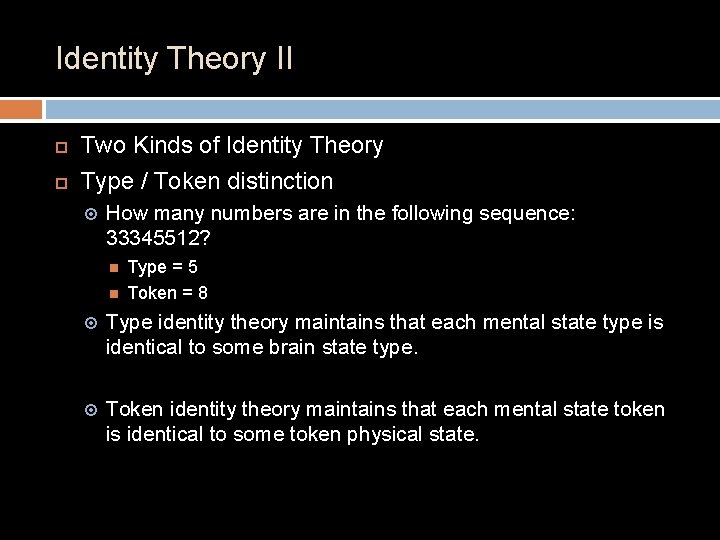

Identity Theory II Two Kinds of Identity Theory Type / Token distinction How many numbers are in the following sequence: 33345512? Type = 5 Token = 8 Type identity theory maintains that each mental state type is identical to some brain state type. Token identity theory maintains that each mental state token is identical to some token physical state.

Jackson’s Mary Thought Experiment I Mary is a brilliant scientist who is, for whatever reason, forced to investigate the world from a black and white room via a black and white television monitor. She specializes in neurophysiology of vision and acquires, let us suppose, all the physical information there is to obtain about what goes on when we see ripe tomatoes, or the sky, and use terms like ‘red’, ‘blue’, and so on. She discovers, for example, just which wavelength combinations from the sky stimulate the retina, and exactly how this produces via the ventral nervous system the contraction of the vocal chords and expulsion of air from the lungs that results in the uttering of the sentence ‘The sky is blue’… What will happen when Mary is released from her black and white room or is given a color television monitor? Will she learn anything or not? It seems just obvious that she will learn something about the world and our visual experience of it. But then is it inescapable that her previous knowledge was incomplete. She had all the physical information. Ergo there is more to have than that, and physicalism is false. Frank Jackson Epiphenomenal Qualia

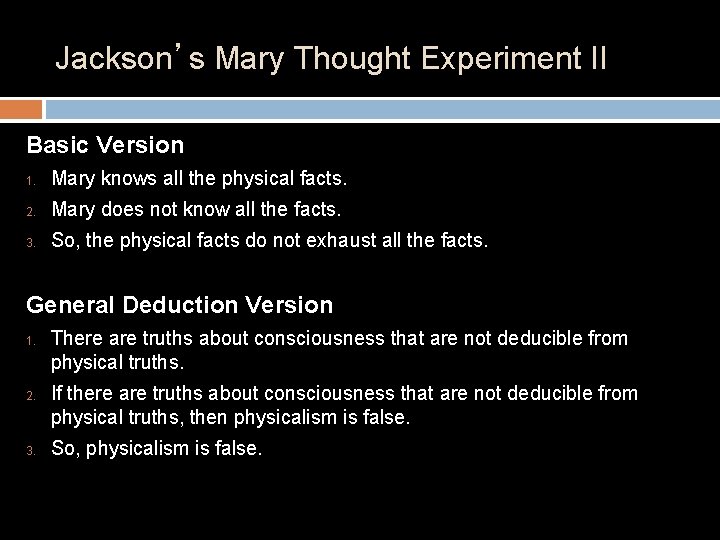

Jackson’s Mary Thought Experiment II Basic Version 1. Mary knows all the physical facts. 2. Mary does not know all the facts. 3. So, the physical facts do not exhaust all the facts. General Deduction Version 1. 2. 3. There are truths about consciousness that are not deducible from physical truths. If there are truths about consciousness that are not deducible from physical truths, then physicalism is false. So, physicalism is false.

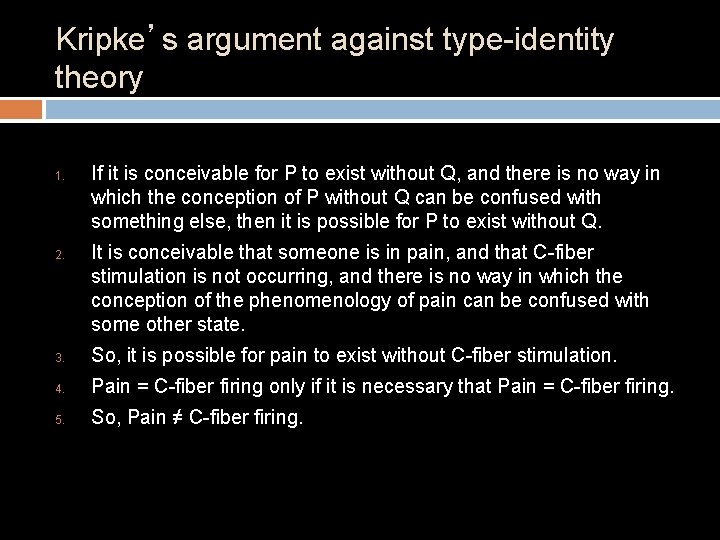

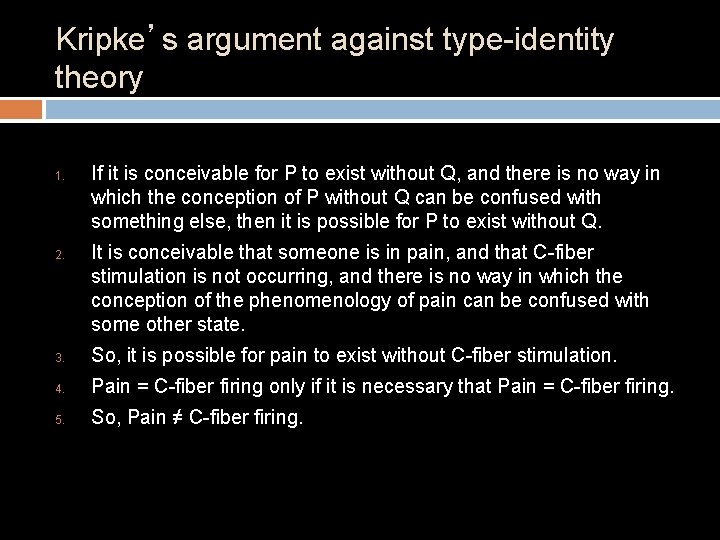

Kripke’s argument against type-identity theory 1. 2. If it is conceivable for P to exist without Q, and there is no way in which the conception of P without Q can be confused with something else, then it is possible for P to exist without Q. It is conceivable that someone is in pain, and that C-fiber stimulation is not occurring, and there is no way in which the conception of the phenomenology of pain can be confused with some other state. 3. So, it is possible for pain to exist without C-fiber stimulation. 4. Pain = C-fiber firing only if it is necessary that Pain = C-fiber firing. 5. So, Pain ≠ C-fiber firing.

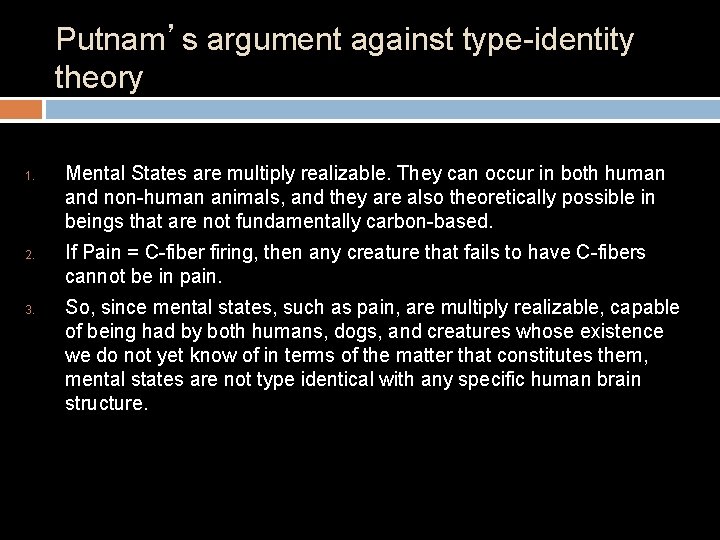

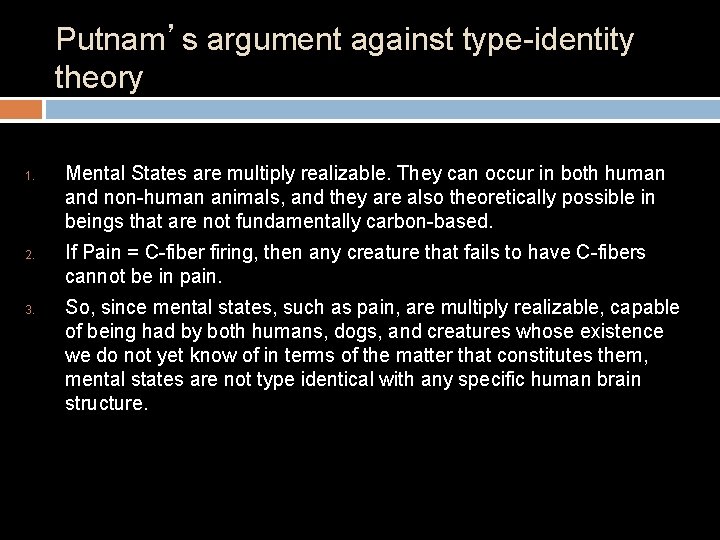

Putnam’s argument against type-identity theory 1. 2. 3. Mental States are multiply realizable. They can occur in both human and non-human animals, and they are also theoretically possible in beings that are not fundamentally carbon-based. If Pain = C-fiber firing, then any creature that fails to have C-fibers cannot be in pain. So, since mental states, such as pain, are multiply realizable, capable of being had by both humans, dogs, and creatures whose existence we do not yet know of in terms of the matter that constitutes them, mental states are not type identical with any specific human brain structure.

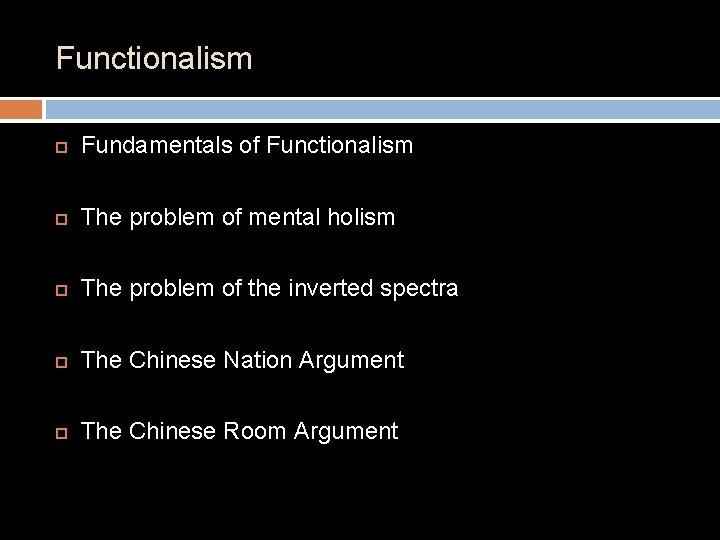

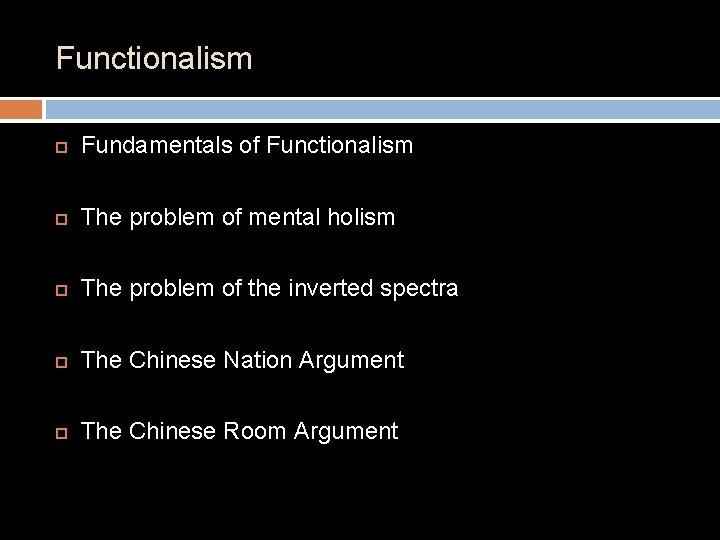

Functionalism Fundamentals of Functionalism The problem of mental holism The problem of the inverted spectra The Chinese Nation Argument The Chinese Room Argument

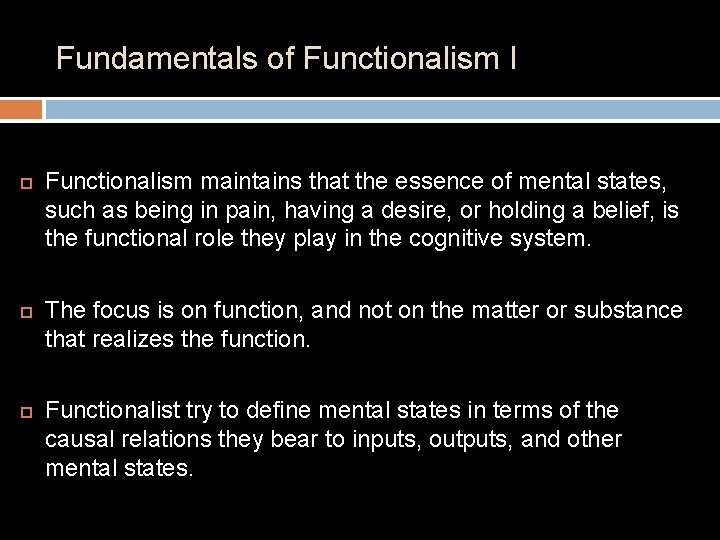

Fundamentals of Functionalism I Functionalism maintains that the essence of mental states, such as being in pain, having a desire, or holding a belief, is the functional role they play in the cognitive system. The focus is on function, and not on the matter or substance that realizes the function. Functionalist try to define mental states in terms of the causal relations they bear to inputs, outputs, and other mental states.

Fundamentals of Functionalism II Example: Pain is the state that tends to be caused by bodily injury, to produce the belief that something is wrong with the body and the desire to be out of that state, to produce anxiety, and in the absence of any stronger, conflicting desires, to cause wincing or moaning. Functionalism is not the same as behaviorism because while behaviorism makes no reference to internal mental states, functionalism explicitly does. Functionalism is not open to the circularity problem that behaviorism faced because functionalist can use Ramsey-sentences to avoid circularity. Consider the definition of pain above. The Ramsey sentence of it is: x y z w [x tends to be caused by bodily injury & x tends to produce states y, z, and w & x tends to produce wincing and moaning].

The Problem of Mental Holism The objection from mental holism holds that functionalism makes it very hard for two distinct individuals of the same species and two individuals of different species to share the same mental state. Between Persons Version: John and Jim both believe the A’s will win the pennant, but that and a few other beliefs are the only ones they have in common. So given that so little of their psychology is in common, it cannot be that their beliefs have the same functional role, so they don’t have the same belief. Cross Species Version: John and Bunny Rabbit Sam both can feel pain, but since John has a richer psychology than Sam, they are not both in pain. Mental holism cuts against the idea that functionalism can really

The Problem of Inverted Spectra 1. 2. Functionalism about the qualitative aspects of seeing a color is true only if it is impossible for there to be two individuals with identical functional roles, but distinct qualitative characters. It is conceivable that two individuals exist with inverted spectra, where one sees blue the other sees yellow, where one sees red the other sees green. 3. If it is conceivable that P, then it is possible that P. 4. So, it is possible that inverted spectra exists. 5. So, functionalism about the qualitative aspect of seeing a color is false. Functionalism cannot capture the qualitative aspect of experience.

The Chinese Nation Argument I Suppose we convert the government of China to functionalism, and we convince its officials that it would enormously enhance their international prestige to realize a human mind for an hour. We provide each of the billion people in China with a specially designed two-way radio that connects them in the appropriate way to other persons and to the artificial body mentioned in the previous example. We replace the little men with a radio transmitter and receiver connected to the input and output neurons. Instead of a bulletin board, we arrange to have letters displayed on a series of satellites placed so that they can be seen from anywhere in China. Ned Block Troubles with Functionalism Question: Would such a system instantiate a mind?

The Chinese Nation Argument II 1. 2. 3. 4. Functionalism maintains that mental states are defined by their functional role and not by the material that realizes the role. And is true only if any material that does realize the role actually instantiates the state. It is possible for the Chinese nation to instantiate the role of a particular mental state, or set of mental states, for about an hour. However, it is implausible that the Chinese nation actually instantiates the particular mental state, or set of mental states, for the hour envisioned. So, functionalism is false.

The Chinese Room Argument I Imagine that a bunch of computer programmers have written a program that will enable a computer to simulate the understanding of Chinese. So, for example, if the computer is given a question in Chinese, it will match the question against its memory, or data base, and produce appropriate answers to the questions in Chinese. Suppose for the sake of argument that the computer’s answers are as good as those of a native Chinese speaker. Now then, does the computer, on the basis of this, understand Chinese, does it literally understand Chinese, in the way that Chinese speakers understand Chinese?

The Chinese Room Argument II Imagine that you are locked in a room, and in this room are several baskets full of Chinese symbols. Imagine that you (like me) do not understand a word of Chinese, but that you are given a rule book in English for manipulating these Chinese symbols. The rules specify the manipulations of the symbols purely formally, in terms of their syntax, not their semantics. So the rule might say: ‘Take a squiggle-squiggle sign out of basket number one and put it next to a squoggle-squoggle sign from basket number two’. Now suppose that some other Chinese symbols are passed into the room, and that you are given further rules for passing back Chinese symbols out of the room. Suppose that unknown to you the symbols passed into the room are called ‘questions’ by the people outside the room, and the symbols you pass back out of the room are called ‘answers to questions’. Suppose, furthermore, that the programmers are so good at designing the programs and that you are so good at manipulating the symbols, that vey soon your answers are indistinguishable from those of a native Chinese speaker. There you are locked in your room shuffling your Chinese symbols with respect to incoming Chinese symbols.

The Chinese Room Argument III 1. 2. 3. Strong AI: A suitably programmed computer can understand a natural language and actually have other mental capabilities similar to humans. If Strong AI is true, then there is a program for Chinese such that if any computing system runs that program, that system thereby comes to understand Chinese. A person could run a program for Chinese without thereby coming to understand Chinese. Therefore, Strong AI is false.

The Chinese Room Argument IV 1. 2. 3. 4. Computer programs are completely defined by their formal syntactic structure. Manipulating syntax is not sufficient for generating semantic understanding. Minds have semantic capacities. So, computers cannot give rise to minds. Simulating a Mind is not equivalent to Duplicating a Mind

Physical Reduction Fundamentals of physical reduction Kim’s argument from causal exclusion Davidson – Fodor argument against reduction

Fundamentals of physical reduction I Reduction is the general attempt to reduce a phenomenon described in one vocabulary to the language of another vocabulary. Typically one claims that the reduced vocabulary is not fundamental. Physical Reduction in the philosophy of mind is the view that mental life can be completely understood in terms of physical entities and relations. Physical Supervenience: No two possible worlds can be identical in their physical properties and be different in their mental or social properties. If A supervenes on B, then A can be reduced to B.

Fundamentals of physical reduction II Supervenience: Lewis’s example A dot-matrix picture has global properties – it is symmetrical, it is cluttered, and whatnot – and yet all there is to the picture is dots and non-dots at each point of the matrix. The global properties are nothing but patterns in the dots. They supervene: no two pictures could differ in their global properties without differing, somewhere, in whethere is or there isn’t a dot. Reduction: Lewis’s account 1. Mental State M = occupant of functional role F. 2. Occupant of F = brain state B. 3. Therefore M = B.

Kim’s argument from causal exclusion The following four claims appear to be inconsistent: 1. 2. 3. 4. Mental properties have causal powers. Mental properties supervene on physical properties. Every physical effect has a sufficient physical cause. If a property E has a sufficient cause C, then no other property C* distinct from C can be the cause of E. What causal work do mental properties do?

Fodor’s argument against reduction I From the character of the laws 1. Laws of psychology involve exceptions. 2. Laws of physics do not involve exceptions. 3. So, the laws of psychology cannot be reduced to the laws of physics. Psychological Law: If agent A desires D, and M is a means to D, then all else being equal A ought to do M. Physical Law: E = MC 2. These laws don’t have the same characters. So, reduction is impossible.

Fodor’s argument against reduction II From the nature of laws 1. 2. 3. It is a law that P brings about Q. It is a law that R brings about S. It is a law that P or R brings about Q or S. Fodor argues that while 1 and 2 are laws, 3 is not a law. Fundamental Laws do not contain disjunctions in their antecedents and consequents.

Bhadeshia lectures

Bhadeshia lectures How to get the most out of lectures

How to get the most out of lectures Reinforcement learning lectures

Reinforcement learning lectures Hegel three forms of art

Hegel three forms of art Ludic space

Ludic space Define aerodynamics

Define aerodynamics Pab ankle fracture

Pab ankle fracture Medical emergency student lectures

Medical emergency student lectures Bureau of lectures

Bureau of lectures Oral communication 3 lectures text

Oral communication 3 lectures text Dr sohail lectures

Dr sohail lectures Translation 1

Translation 1 Data mining lectures

Data mining lectures Cern summer student lectures

Cern summer student lectures Yelena bogdan md

Yelena bogdan md Frcr physics lectures

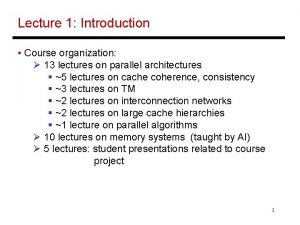

Frcr physics lectures 13 lectures

13 lectures Nuclear medicine lectures

Nuclear medicine lectures Step wise project planning

Step wise project planning Tamara berg husband

Tamara berg husband Anatomy lectures powerpoint

Anatomy lectures powerpoint Hematology medicine student lectures

Hematology medicine student lectures Utilities and energy lecture

Utilities and energy lecture Slagle lecture

Slagle lecture C programming and numerical analysis an introduction

C programming and numerical analysis an introduction Medicinal chemistry lectures

Medicinal chemistry lectures Digital logic design lectures

Digital logic design lectures Cs106b lectures

Cs106b lectures Pathology lectures for medical students

Pathology lectures for medical students Comsats virtual campus lectures

Comsats virtual campus lectures Frequency of xrays

Frequency of xrays Reinforcement learning lectures

Reinforcement learning lectures Cs106b lectures

Cs106b lectures Cell and molecular biology lectures

Cell and molecular biology lectures Power system lectures

Power system lectures Rick trebino lectures

Rick trebino lectures Cern summer school lectures

Cern summer school lectures Rcog cpd portfolio

Rcog cpd portfolio Web engineering lectures ppt

Web engineering lectures ppt Theory of translation lectures

Theory of translation lectures Orthopedic ppt lectures

Orthopedic ppt lectures Compsci 453

Compsci 453 Blood physiology guyton

Blood physiology guyton Dr asim lectures

Dr asim lectures Hugh blair lectures on rhetoric

Hugh blair lectures on rhetoric Bba lectures

Bba lectures Cdeep lectures

Cdeep lectures Radio astronomy lectures

Radio astronomy lectures Haematology lectures

Haematology lectures Theory of translation lectures

Theory of translation lectures Lectures paediatrics

Lectures paediatrics Empiricism and the philosophy of mind

Empiricism and the philosophy of mind Hổ đẻ mỗi lứa mấy con

Hổ đẻ mỗi lứa mấy con Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu

Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu Diễn thế sinh thái là

Diễn thế sinh thái là Thế nào là giọng cùng tên? *

Thế nào là giọng cùng tên? *