Migration in Chordates By Dr Rashmi Kohli Types

Migration in Chordates By: Dr. Rashmi Kohli

Types of Migration (i)Altitudinal migration (vertical migration) (ii) Latitudinal migration • (iii) Longitudinal migration • (iv) Total migration • (v) Partial migration • (vi) Diurnal migration • (vii) Nocturnal migration • (viii) Daily migration • (ix) Seasonal migration • (x) Irregular migration

• Causes of migration (i) The ripening of gonads. (ii)Instinct. (iii)Scarcity of food. (iv)Hostile temperature. (v)Day length. • Range of Migration • Depends upon conditions and the species. • Eg – the arctic tern travels 11, 000 miles to reach Antarctica in winters. • European white stork covers about 8000 miles to south Africa.

Speed of Migration Average speed of flight during migration – 30 to 50 miles per hour. E. g. – Stork (covers non stop 600 km in 6 hrs). Plover (covers non stop 880 km in 11 hrs). Altitude of migration Most birds fly up to height of 3000 ft. Some small birds fly at 5000 to 14000 ft. during night. Some fly very close to earth (Migrating geese, painted snipe, etc). Regularity of migration Birds maintain regularity and accuracy & remain constant in choice of breeding place (Purple martins). Routes of migration Birds follow same routes each year. E. g. – sandpipers.

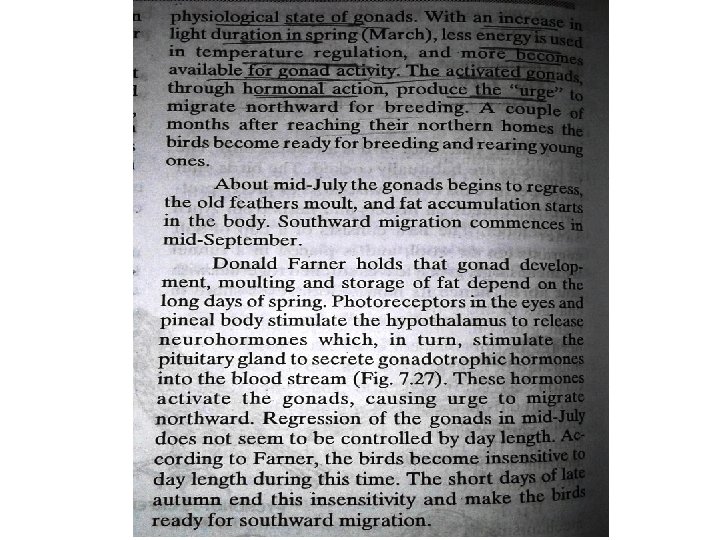

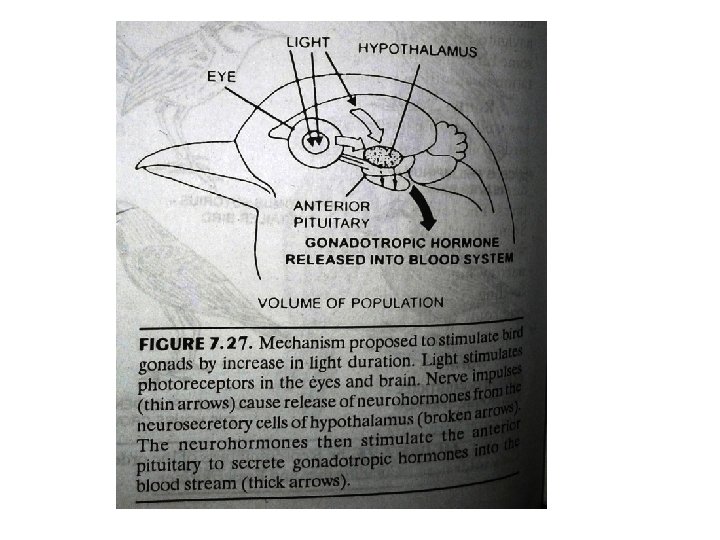

Guiding mechanism (i) Landmarks – topographical features like rivers, valleys, oceans, deserts, etc. (ii) Earth magnetic field (iii)Telluric currents – air currents may lead birds. (iv)Experience (v) Sun – birds use sun as a compass. (vi)Stars (vii)Internal clock and compass. Stimulus External stimuli – variation in day length. Internal stimuli – favorable energy balance & physiological state of gonads.

ORIENTATION AND NAVIGATION • Birds use their senses for navigation. • Most of them use sun as compass. • The navigation may also be based on abilities, such as ability to detect magnetic field, use visual land marks or olfactory cues. • The older individuals even use correlation of wind drift. • Migratory birds use two forms electromagnetic tools to find and reach their destination, one is innate and while other is due to experience. • When the birds are young they migrate correct by following the direction of Earth's magnetic field but they are unawared about how far their destination is.

ORIENTATION AND NAVIGATION • This happens by radical pair mechanism due to chemical reaction in photo pigments sensation to long wave length. • It is as simples as a boy scout with a compass but no map, but with age the birds gain experience and they can landmark and do mapping by magnetities in trigeminal system, which indicates about strength of magnitude at different latitudes while going from North to South and let the bird reach the destination. • Research has shown that there is a neural connection between eyes and cluster N (a part of forebrain) which stays activated during migration orientation which helps birds to actually see the magnetic field of Earth.

Adaptations • Birds need to alter their metabolism in order to meet the demands of migration. • The storage of energy through the accumulation of fat and the control of sleep in nocturnal migrants require special physiological adaptations. • In addition, the feathers of a bird suffer from wear-andtear and require to be molted. • The timing of this molt - usually once a year but sometimes two - varies with some species molting prior to moving to their winter grounds and others molting prior to returning to their breeding grounds. • Apart from physiological adaptations, migration sometimes requires behavioural changes such as flying in flocks to reduce the energy used in migration or the risk of predation.

Threats and conservation 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Human activities have threatened many migratory bird species. The distances involved in bird migration mean that they often cross political boundaries of countries and conservation measures require international cooperation. Several international treaties have been signed to protect migratory species including the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 of the US and the African. Eurasian Migratory Waterbird Agreement. The concentration of birds during migration can put species at risk. Some spectacular migrants have already gone extinct, the most notable being the Passenger Pigeon(Ectopistes migratorius). During migration the flocks were a mile (1. 6 km) wide and 300 miles (500 km) long, taking several days to pass and containing up to a billion birds. Other significant areas include stop-over sites between the wintering and breeding territories. [ Hunting along the migratory route can also take a heavy toll. The populations of Siberian Cranes that wintered in India declined due to hunting along the route, particularly in Afghanistan and Central Asia. Birds were last seen in their favourite wintering grounds in Keoladeo National Park in 2002. Structures such as power lines, wind farms and offshore oil-rigs have also been known to affect migratory birds. Habitat destruction by land use changes is the biggest threat, and shallow wetlands that are stopover and wintering sites for migratory birds are particularly threatened by draining and reclamation for human use.

TYPES OF MIGRATION IN FISHES • POTAMODROMOUS MIGRATION • When fishes migrate from one freshwater habitat to another in search of food or for spawning, it is called potamodromous migration. • There about 8, 000 known species that migrate within lakes and rivers, generally for food on daily basis as the availability of food differs from place to place and from season to season. • Fishes also must migrate to lay their eggs in places where oxygen concentration in water is more and where there is abundance of food for juveniles when they hatch from eggs. COMMON ASIAN CARPS

TYPES OF MIGRATION IN FISHES • OCEANODROMOUS MIGRATION • This migration is from sea water to sea water. • There are no barriers within the sea and fishes have learned to migrate in order to take advantage of favourable conditions wherever they occur. • Thus there about 12, 000 marine species that regularly migrate within sea water. • Herrings, sardines, mackerels, cods, roaches and tunas migrate in large numbers in search of food by way of shoaling (migrating together socially but without much coordination) or schooling (swimming with high degree of coordination and synchronized manoeuvres).

DIADROMOUS MIGRATION • When fishes can migrate from fresh water to sea or from sea to fresh water, it is called diadromous migration. • There about 120 species of fishes that are capable of overcoming osmotic barriers and migrate in these two different types of habitats. • This migration is of two types. 1. Catadromous migration 2. Anadromous migration

Catadromous migration • This type of migration involves movement of large number of individuals from fresh water to sea water, generally for spawning as happens in the case of eels (Anguilla) inhabiting European and North American rivers. • Both European eel (Anguilla anguilla or Anguilla vulgaris) and the American eel (Anguilla rostrata) migrate from the continental rivers to Sargasso Sea off Bermuda in south Atlantic for spawning, crossing Atlantic Ocean during the journey and covering a distance of about 5, 600 km. • The adult eels that inhabit rivers are about a metre long, yellow in colour and spend 8 -15 years feeding and growing.

Migration • Before migration the following changes take place in their bodies: • They deposit large amount of fat in their bodies which serves as reserve food during the long journey to Sargasso Sea. • Colour changes from yellow to metallic silvery grey. • Digestive tract shrinks and feeding stops. • Eyes are enlarged and vision sharpens. Other sensory organs also become sensitive. • Skin becomes respiratory. • Gonads get matured and enlarged. • They become restless and develop strong urge to migrate in groups. • They migrate through the rivers and reach coastal areas of the sea where they are joined by the males and then together they swim in large numbers, reaching Sargasso Sea in about two months. They spawn and die. Each female lays about 20 million eggs which are soon fertilized by males.

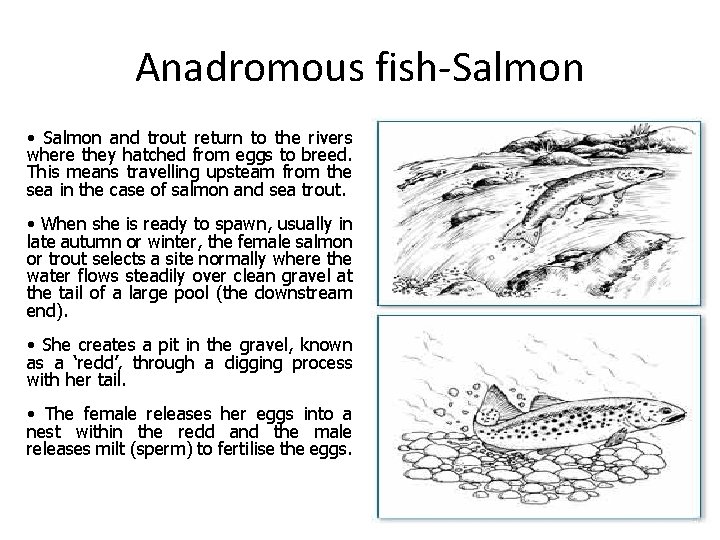

Anadromous fish-Salmon • Salmon and trout return to the rivers where they hatched from eggs to breed. This means travelling upsteam from the sea in the case of salmon and sea trout. • When she is ready to spawn, usually in late autumn or winter, the female salmon or trout selects a site normally where the water flows steadily over clean gravel at the tail of a large pool (the downstream end). • She creates a pit in the gravel, known as a ‘redd’, through a digging process with her tail. • The female releases her eggs into a nest within the redd and the male releases milt (sperm) to fertilise the eggs.

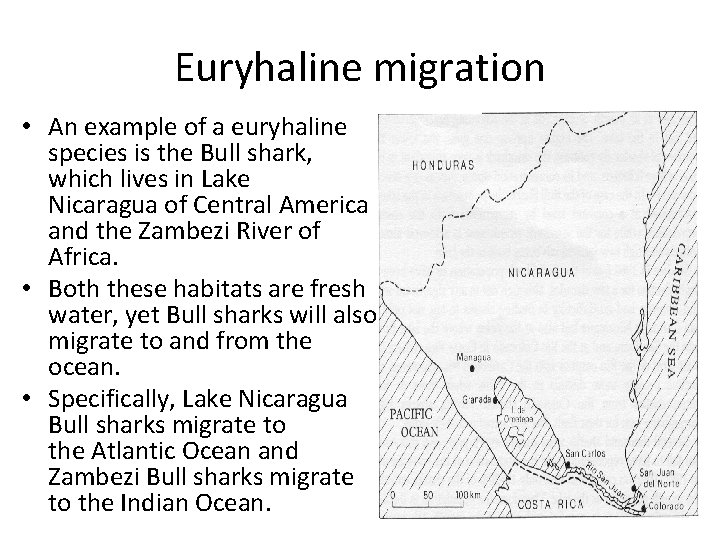

Euryhaline migration • An example of a euryhaline species is the Bull shark, which lives in Lake Nicaragua of Central America and the Zambezi River of Africa. • Both these habitats are fresh water, yet Bull sharks will also migrate to and from the ocean. • Specifically, Lake Nicaragua Bull sharks migrate to the Atlantic Ocean and Zambezi Bull sharks migrate to the Indian Ocean.

The Rigors of Making Freshwater. Saltwater Transitions • Diadromous fishes are of particular interest to physiologists because of the great challenges posed by freshwater-saltwater transitions. • In particular, freshwater and saltwater environments make strikingly different demands on water-balance systems, so these fishes must make the necessary physiological adjustments whenever they pass from one type of aquatic habitat to the other • Every diadromous species migrates at least twice, once from freshwater to saltwater, and once in the other direction. • Because of their ability to tolerate a variety of salinity regimes, diadromous species are also described as euryhaline, meaning "broadly salty. "

The Rigors of Making Freshwater. Saltwater Transitions • Freshwater fish are in an environment in which they are hyperosmotic. • That is, the concentration of salts and ions in their bodies is greater than that in the external aquatic environment. As a result, they have a tendency to lose important ions through diffusion across the skin and gills, and simultaneously to gain water from the environment. • To maintain homeostasis, freshwater species have special adaptations for retaining ions and getting rid of excess water. • First, they actively take in ions across their gills and skin, a process that requires energy. • Second, to get rid of excess water they excrete nitrogenous waste products in great quantities, in the form of a highly diluted urine.

The Rigors of Making Freshwater. Saltwater Transitions • • • In marine environments the challenges are the opposite. Saltwater species must deal with an environment in which their salt and ionic concentrations are significantly lower than that of the surrounding aquatic environment. Saltwater species tend to lose water to the ocean and to gain ions from it. To obtain and conserve water, saltwater species increase their drinking rate, and excrete smaller amounts of a highly concentrated urine. In addition, they eliminate excess ions through specialized salt-excretion cells in the gills and in the lining of the mouth. Euryhaline species must adopt the tactics of freshwater species while in freshwater environments, and those of marine species in saltwater environments. Frequently, physiological adjustments are made while organisms are in the intermediate, brackish waters of estuaries. These include changing their drinking rate, the degree of concentration of their urine, and the direction of ion-pumping in the gills and integument. In addition to these physiological changes, associated with osmoregulation, other changes are made by diadromous species during transitions between freshwater and saltwater habitats. In some diadromous species, external features such as coloration change. For example, in some salmon species, individuals lose their typical red coloration before migrating to sea, where they take on a more silver-coloured form. They regain their freshwater coloration when they reenter the freshwater environment.

- Slides: 29