Microstructure of a polymer glass subjected to instantaneous

Microstructure of a polymer glass subjected to instantaneous shear strains Matthew L. Wallace and Béla Joós Michael Plischke

Introduction • • • Model: a short chain polymer melt (10 monomers) Different types of rigidity transitions The glass transition and the onset of rigidity Shearing the glass: the elastic and plastic regimes Microstructure of the deformed glass: displacements, stresses, UBC Vancouver, July 2007

The issues • Polymer glass under deformation • Glasses are heterogeneous • What happens to the glass when deformed: a lot of questions from aging, mechanical properties, and thermal properties • Which properties are we interested in this study? We will focus on the microstructure as a first step in understanding the effect of deformation on the properties of the glass. Main message: deformation reduces heterogeneity UBC Vancouver, July 2007

Outline • • • Our way of preparing the polymer melt near the glass transition: pressure quench at constant temperature to improve statistics Onset of rigidity in the glass: a new angle on the glass transition Deforming the glass below the rigidity transition: the elastic and plastic regime Macroscopic signatures Changes in the microstructure What is learned, what needs to be learned. UBC Vancouver, July 2007

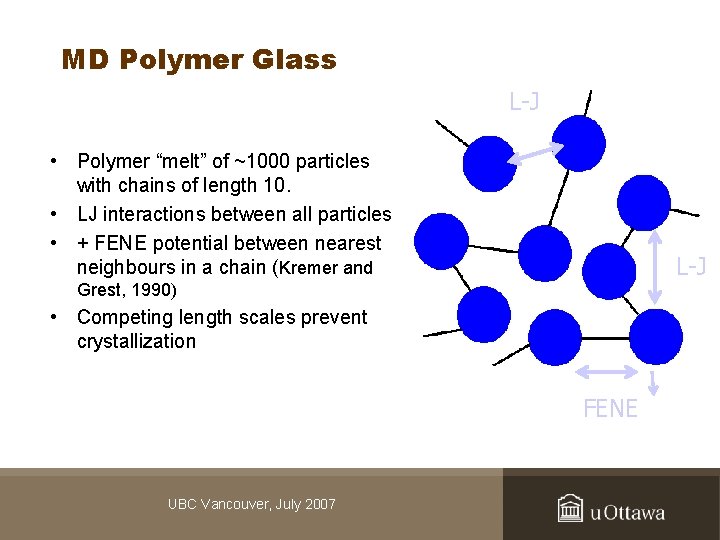

MD Polymer Glass L-J • Polymer “melt” of ~1000 particles with chains of length 10. • LJ interactions between all particles • + FENE potential between nearest neighbours in a chain (Kremer and Grest, 1990) L-J L-J • Competing length scales prevent crystallization FENE UBC Vancouver, July 2007

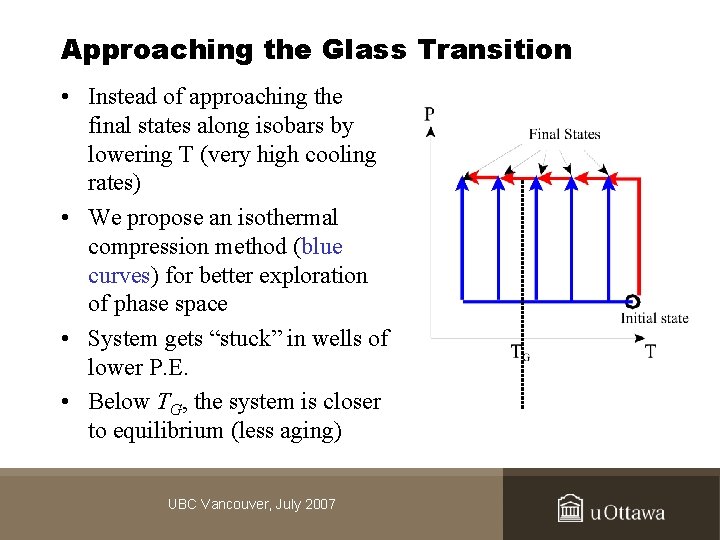

Approaching the Glass Transition • Instead of approaching the final states along isobars by lowering T (very high cooling rates) • We propose an isothermal compression method (blue curves) for better exploration of phase space • System gets “stuck” in wells of lower P. E. • Below TG, the system is closer to equilibrium (less aging) UBC Vancouver, July 2007

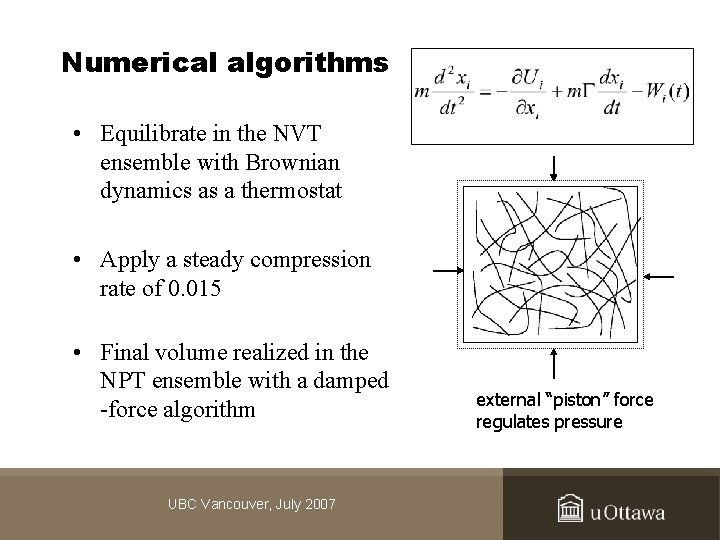

Numerical algorithms • Equilibrate in the NVT ensemble with Brownian dynamics as a thermostat • Apply a steady compression rate of 0. 015 • Final volume realized in the NPT ensemble with a damped -force algorithm UBC Vancouver, July 2007 external “piston” force regulates pressure

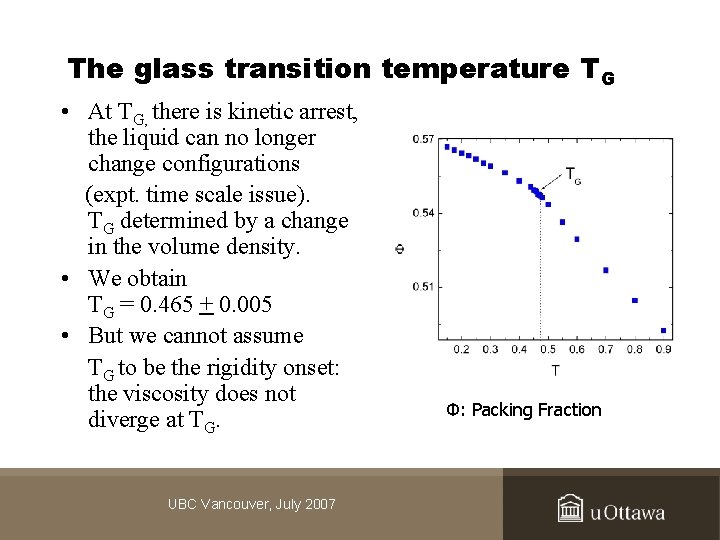

The glass transition temperature TG • At TG, there is kinetic arrest, the liquid can no longer change configurations (expt. time scale issue). TG determined by a change in the volume density. • We obtain TG = 0. 465 + 0. 005 • But we cannot assume TG to be the rigidity onset: the viscosity does not diverge at TG. UBC Vancouver, July 2007 Φ: Packing Fraction

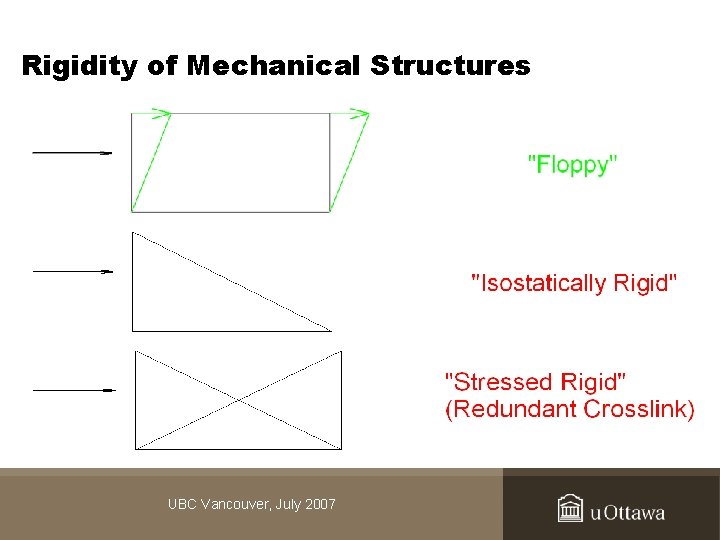

Rigidity of Mechanical Structures UBC Vancouver, July 2007

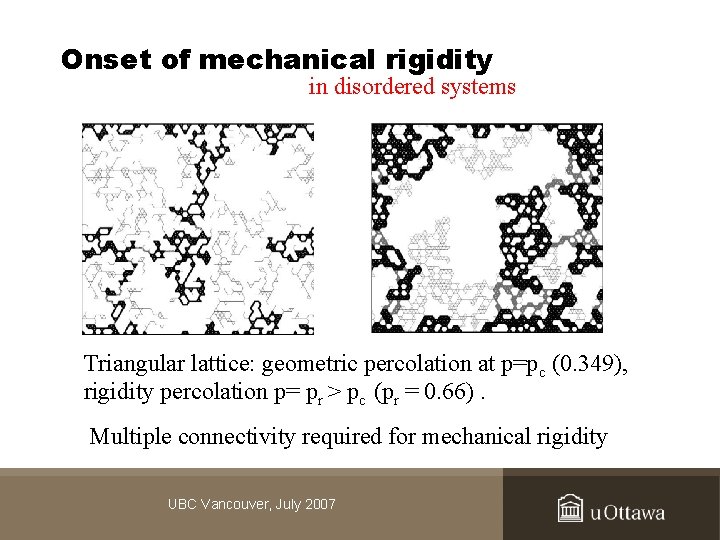

Onset of mechanical rigidity in disordered systems Triangular lattice: geometric percolation at p=pc (0. 349), rigidity percolation p= pr > pc (pr = 0. 66). Multiple connectivity required for mechanical rigidity UBC Vancouver, July 2007

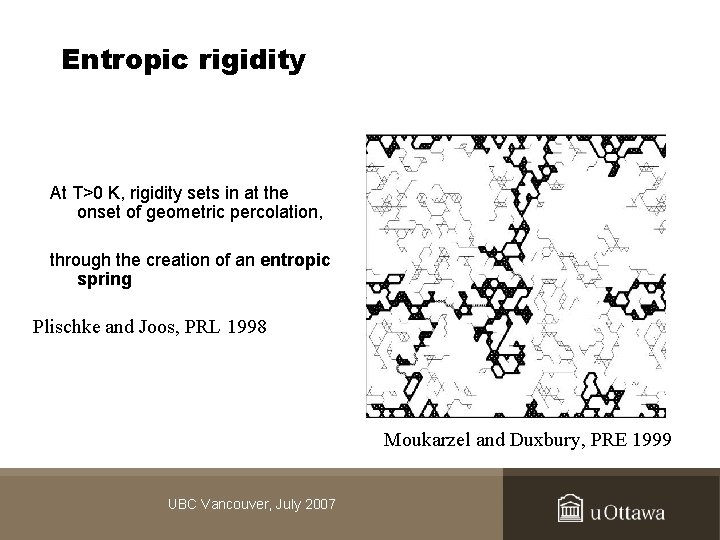

Entropic rigidity At T>0 K, rigidity sets in at the onset of geometric percolation, through the creation of an entropic spring Plischke and Joos, PRL 1998 Moukarzel and Duxbury, PRE 1999 UBC Vancouver, July 2007

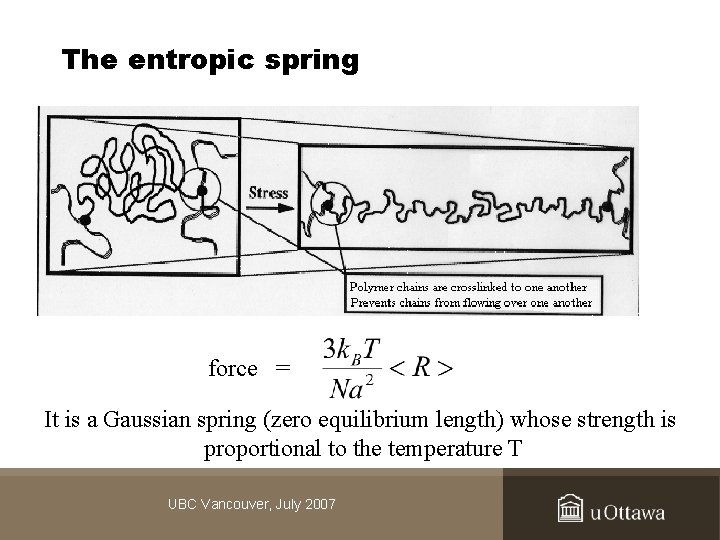

The entropic spring force = It is a Gaussian spring (zero equilibrium length) whose strength is proportional to the temperature T UBC Vancouver, July 2007

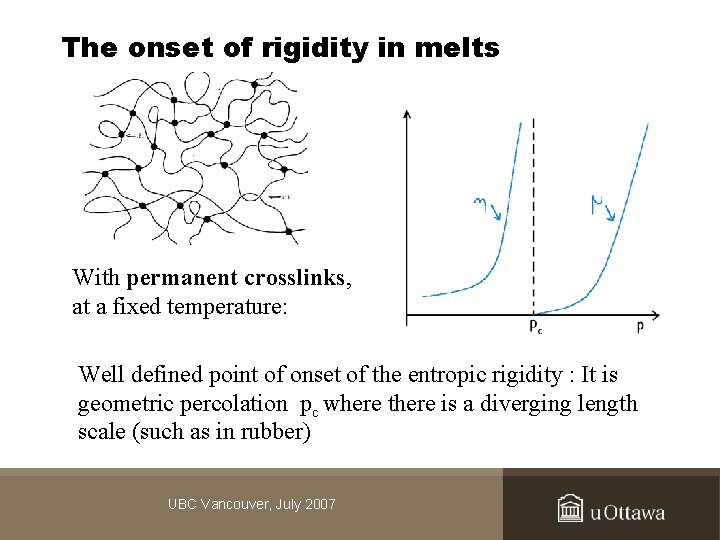

The onset of rigidity in melts With permanent crosslinks, at a fixed temperature: Well defined point of onset of the entropic rigidity : It is geometric percolation pc where there is a diverging length scale (such as in rubber) UBC Vancouver, July 2007

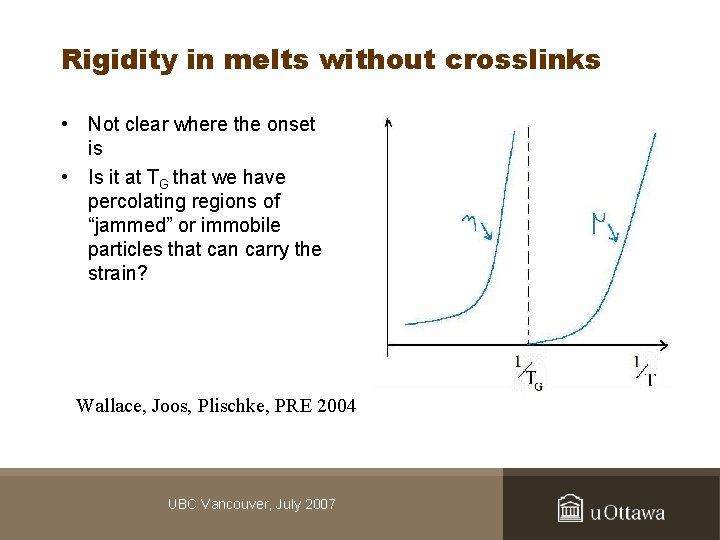

Rigidity in melts without crosslinks • Not clear where the onset is • Is it at TG that we have percolating regions of “jammed” or immobile particles that can carry the strain? Wallace, Joos, Plischke, PRE 2004 UBC Vancouver, July 2007

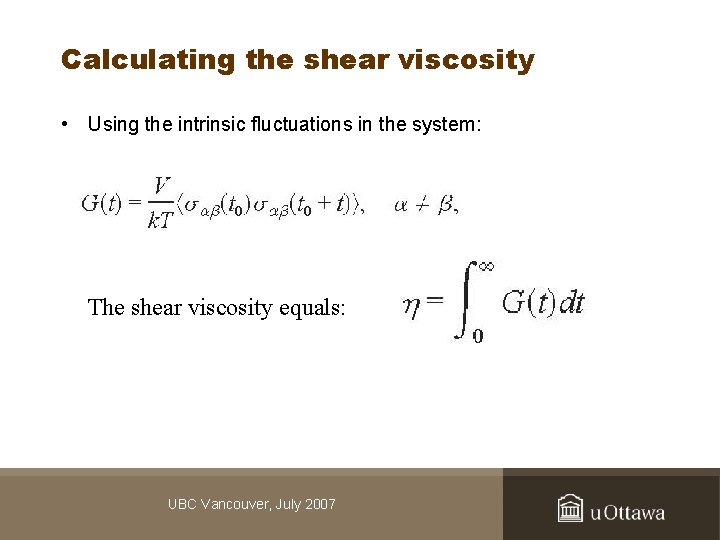

Calculating the shear viscosity • Using the intrinsic fluctuations in the system: The shear viscosity equals: UBC Vancouver, July 2007

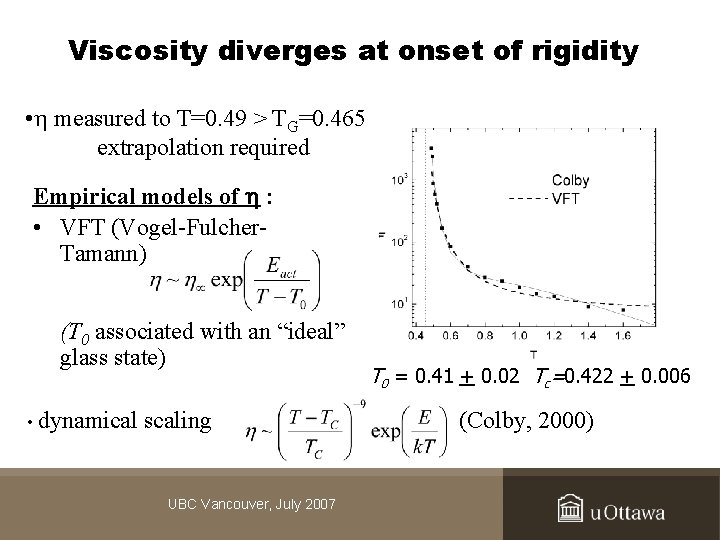

Viscosity diverges at onset of rigidity • measured to T=0. 49 > TG=0. 465 extrapolation required Empirical models of : • VFT (Vogel-Fulcher. Tamann) (T 0 associated with an “ideal” glass state) • dynamical scaling UBC Vancouver, July 2007 T 0 = 0. 41 + 0. 02 Tc=0. 422 + 0. 006 (Colby, 2000)

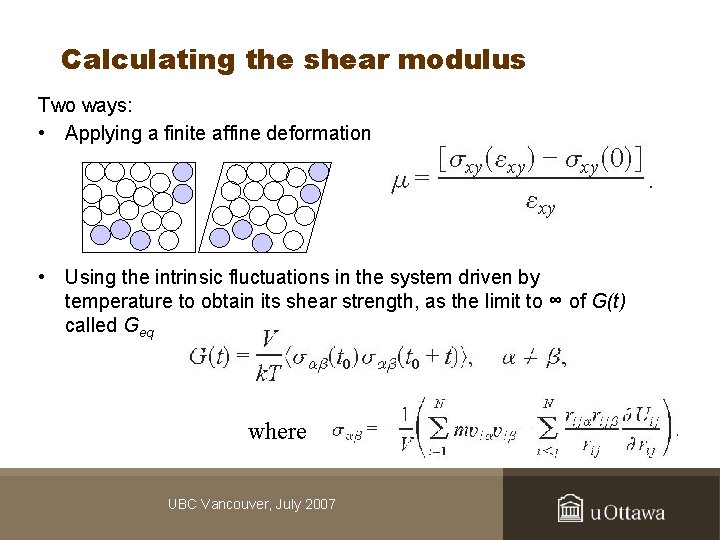

Calculating the shear modulus Two ways: • Applying a finite affine deformation • Using the intrinsic fluctuations in the system driven by temperature to obtain its shear strength, as the limit to ∞ of G(t) called Geq where UBC Vancouver, July 2007

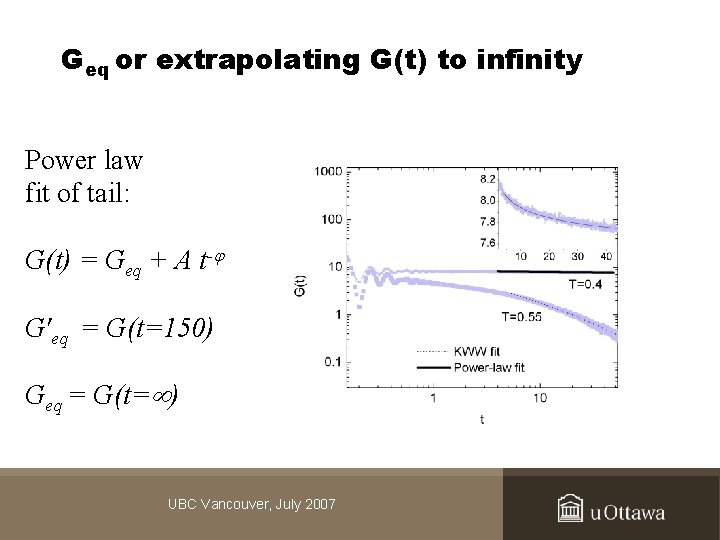

Geq or extrapolating G(t) to infinity Power law fit of tail: G(t) = Geq + A t- G'eq = G(t=150) Geq = G(t= ) UBC Vancouver, July 2007

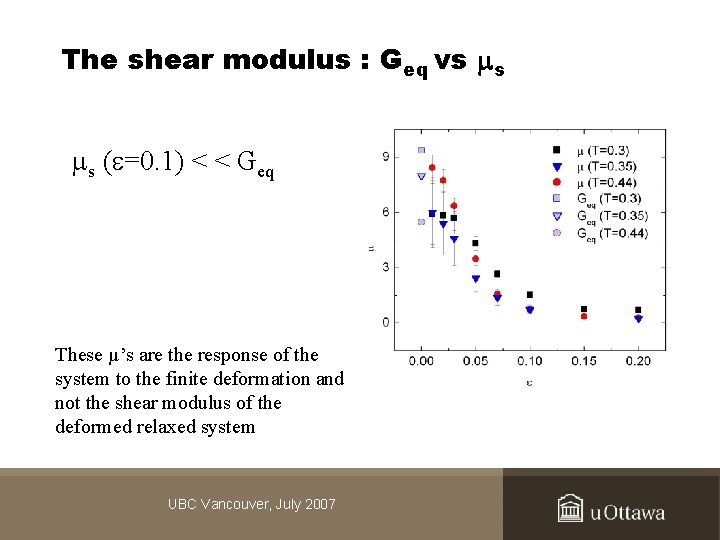

The shear modulus : Geq vs s s ( =0. 1) < < Geq These µ’s are the response of the system to the finite deformation and not the shear modulus of the deformed relaxed system UBC Vancouver, July 2007

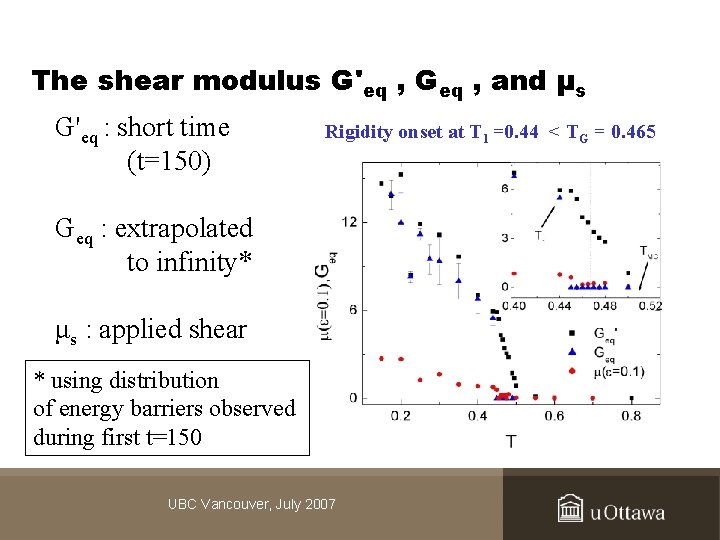

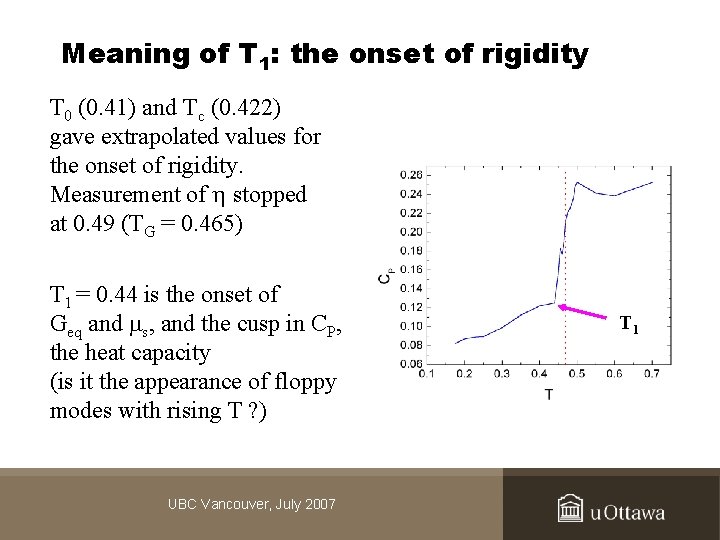

The shear modulus G'eq , Geq , and μs G'eq : short time (t=150) Rigidity onset at T 1 =0. 44 < TG = 0. 465 Geq : extrapolated to infinity* μs : applied shear * using distribution of energy barriers observed during first t=150 UBC Vancouver, July 2007

Meaning of T 1: the onset of rigidity T 0 (0. 41) and Tc (0. 422) gave extrapolated values for the onset of rigidity. Measurement of stopped at 0. 49 (TG = 0. 465) T 1 = 0. 44 is the onset of Geq and s, and the cusp in CP, the heat capacity (is it the appearance of floppy modes with rising T ? ) UBC Vancouver, July 2007 T 1

Issues on rigidity in the polymer glass • TG is the temperature at which the melt stops flowing. It is not a point of divergence of the viscosity (For glass makers: s= 1012 Pa ·s or = s / G = 400 s for Si. O 2 In simulations: s= 107 or = s / G = 105 (simulations 103, unit of time: 2 ps) (issues of time scale and aging) • Onset of rigidity: divergence of viscosity, onset of shear modulus, cusp in heat capacity (disappearance of floppy modes) • Comparison with gelation due to permanent crosslinks: no clearly defined length scale, but there could be a dynamical one UBC Vancouver, July 2007

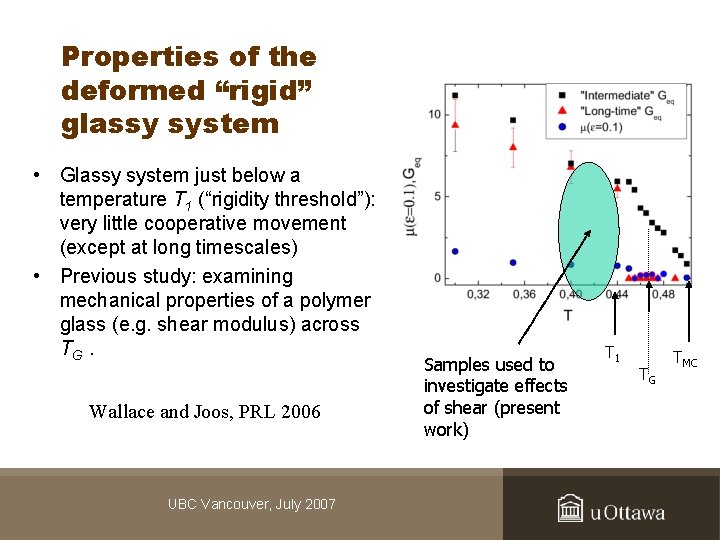

Properties of the deformed “rigid” glassy system • Glassy system just below a temperature T 1 (“rigidity threshold”): very little cooperative movement (except at long timescales) • Previous study: examining mechanical properties of a polymer glass (e. g. shear modulus) across TG. Wallace and Joos, PRL 2006 UBC Vancouver, July 2007 Samples used to investigate effects of shear (present work) T 1 TG TMC

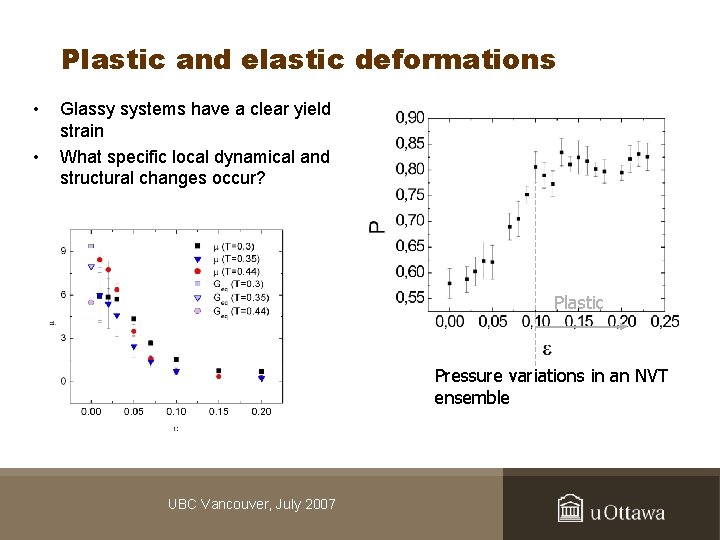

Plastic and elastic deformations • • Glassy systems have a clear yield strain What specific local dynamical and structural changes occur? Plastic Pressure variations in an NVT ensemble UBC Vancouver, July 2007

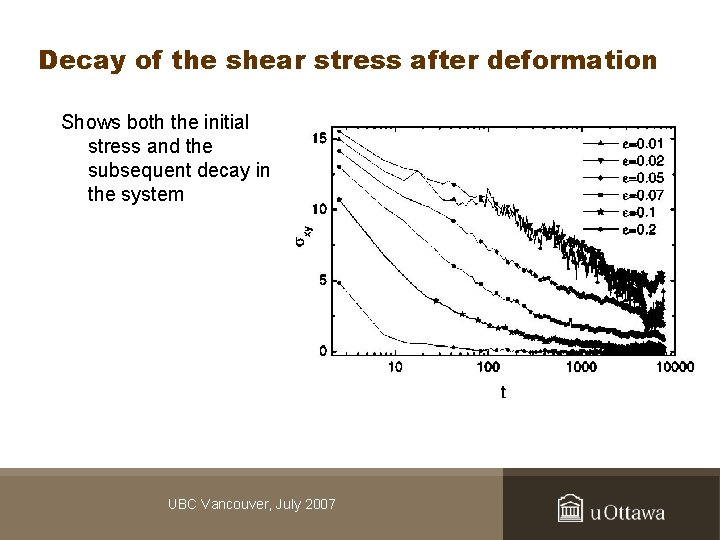

Decay of the shear stress after deformation Shows both the initial stress and the subsequent decay in the system UBC Vancouver, July 2007

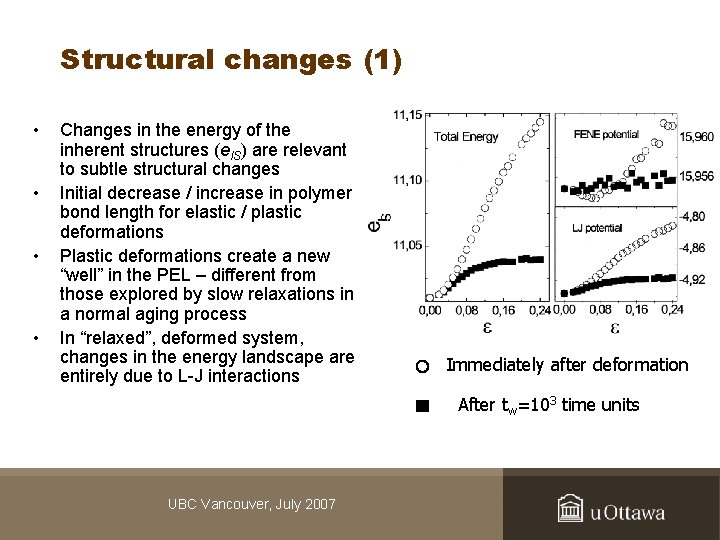

Structural changes (1) • • Changes in the energy of the inherent structures (e. IS) are relevant to subtle structural changes Initial decrease / increase in polymer bond length for elastic / plastic deformations Plastic deformations create a new “well” in the PEL – different from those explored by slow relaxations in a normal aging process In “relaxed”, deformed system, changes in the energy landscape are entirely due to L-J interactions Immediately after deformation After tw=103 time units UBC Vancouver, July 2007

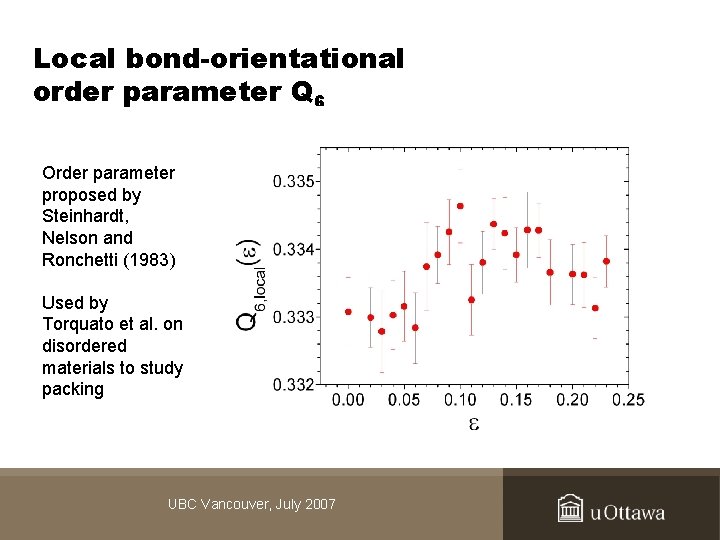

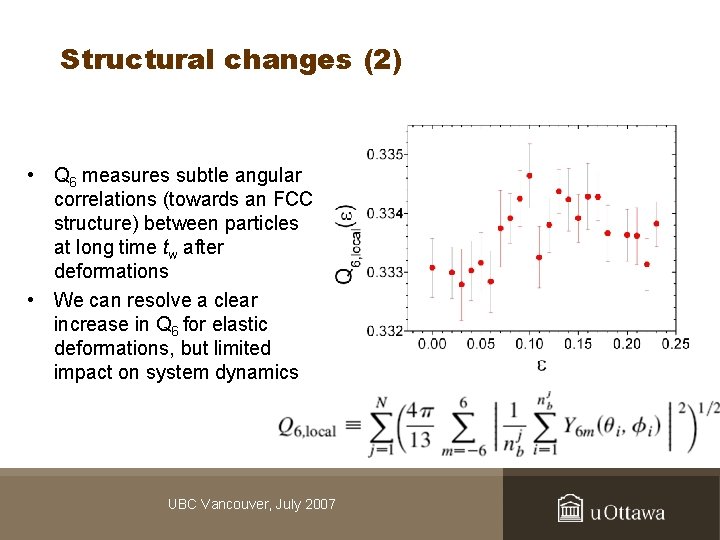

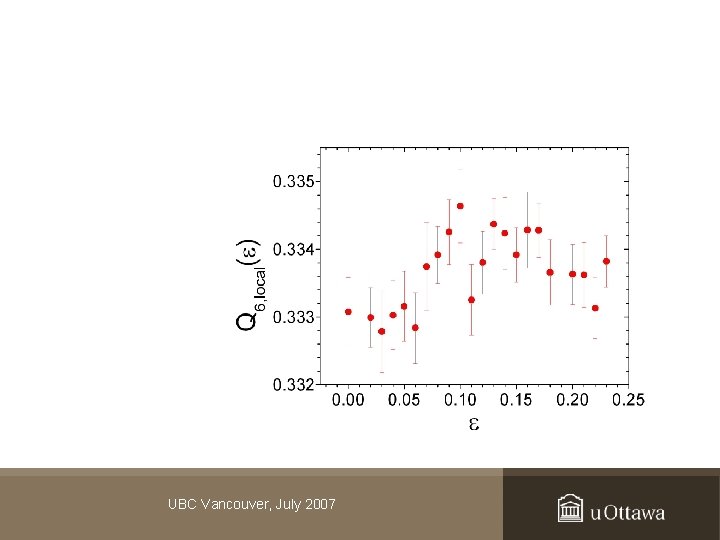

Local bond-orientational order parameter Q 6 Order parameter proposed by Steinhardt, Nelson and Ronchetti (1983) Used by Torquato et al. on disordered materials to study packing UBC Vancouver, July 2007

Structural changes (2) • Q 6 measures subtle angular correlations (towards an FCC structure) between particles at long time tw after deformations • We can resolve a clear increase in Q 6 for elastic deformations, but limited impact on system dynamics UBC Vancouver, July 2007

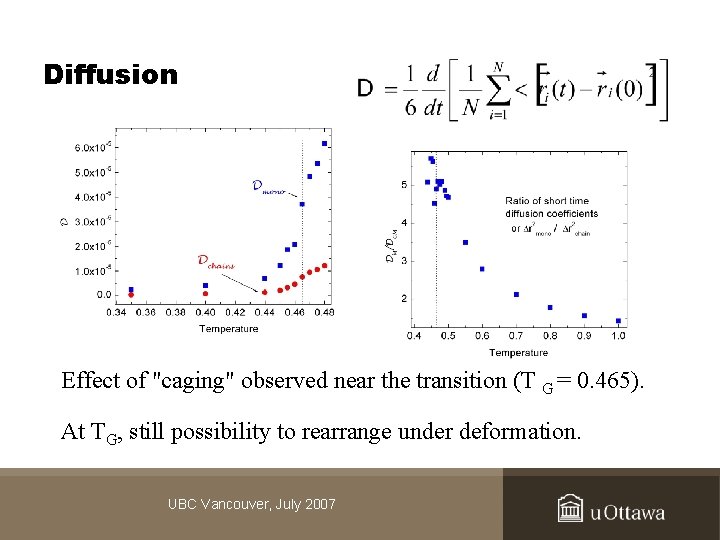

Diffusion Effect of "caging" observed near the transition (T G = 0. 465). At TG, still possibility to rearrange under deformation. UBC Vancouver, July 2007

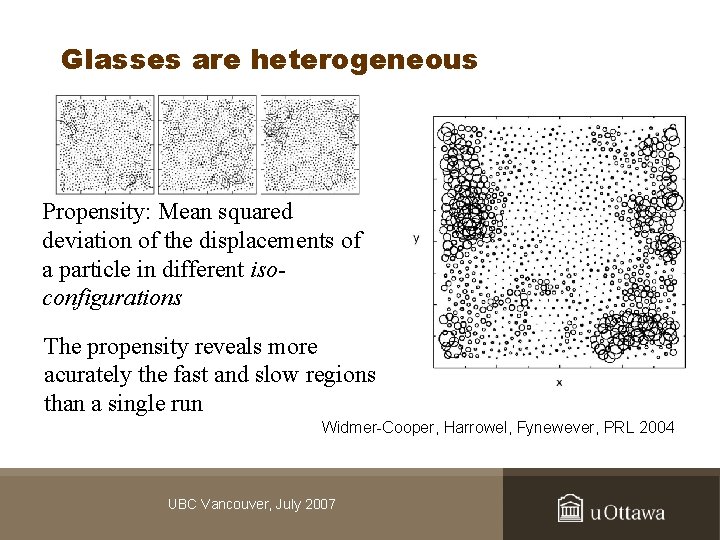

Glasses are heterogeneous Propensity: Mean squared deviation of the displacements of a particle in different isoconfigurations The propensity reveals more acurately the fast and slow regions than a single run Widmer-Cooper, Harrowel, Fynewever, PRL 2004 UBC Vancouver, July 2007

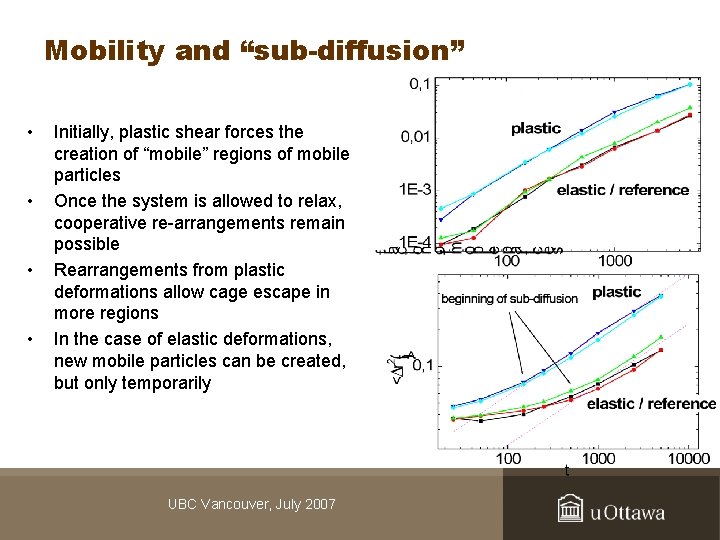

Mobility and “sub-diffusion” • • Initially, plastic shear forces the creation of “mobile” regions of mobile particles Once the system is allowed to relax, cooperative re-arrangements remain possible Rearrangements from plastic deformations allow cage escape in more regions In the case of elastic deformations, new mobile particles can be created, but only temporarily UBC Vancouver, July 2007

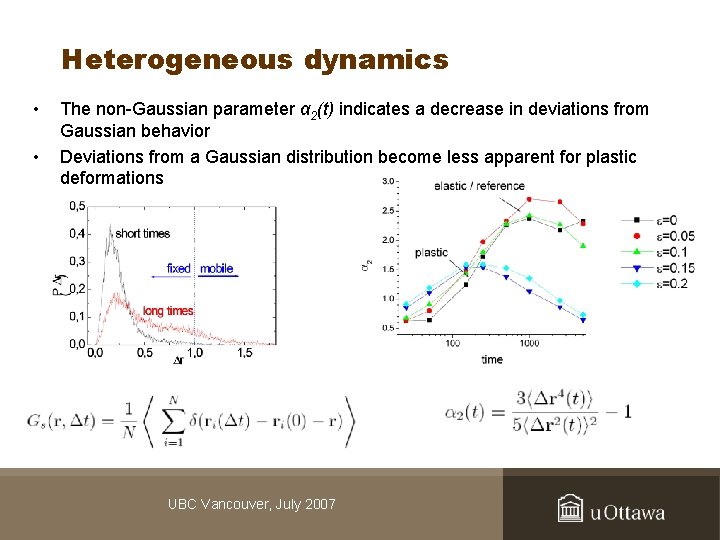

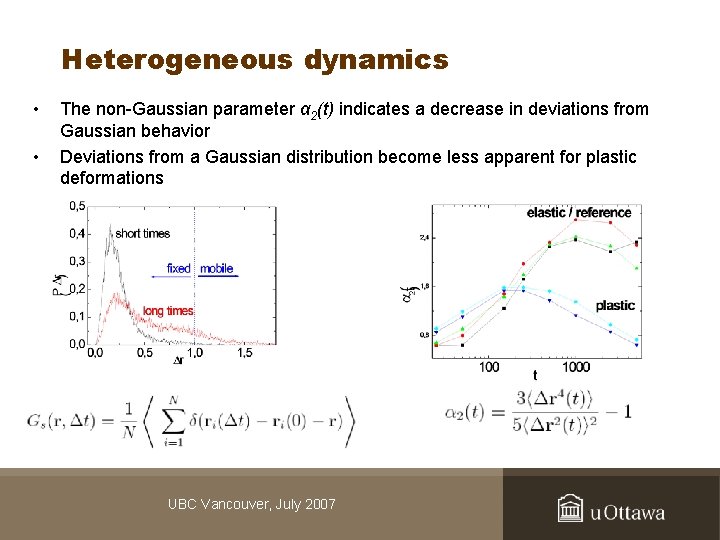

Heterogeneous dynamics • • The non-Gaussian parameter α 2(t) indicates a decrease in deviations from Gaussian behavior Deviations from a Gaussian distribution become less apparent for plastic deformations UBC Vancouver, July 2007

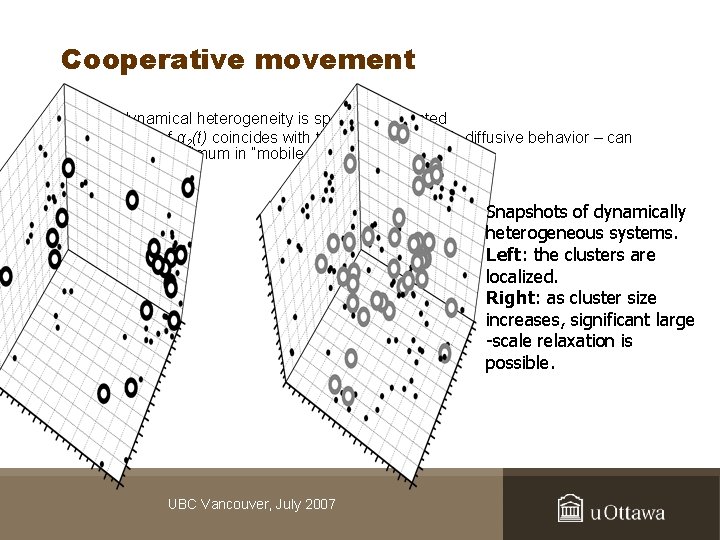

Cooperative movement • • The dynamical heterogeneity is spatially correlated The peak of α 2(t) coincides with the beginning of sub-diffusive behavior – can indicate a maximum in “mobile cluster” size Snapshots of dynamically heterogeneous systems. Left: the clusters are localized. Right: as cluster size increases, significant large -scale relaxation is possible. UBC Vancouver, July 2007

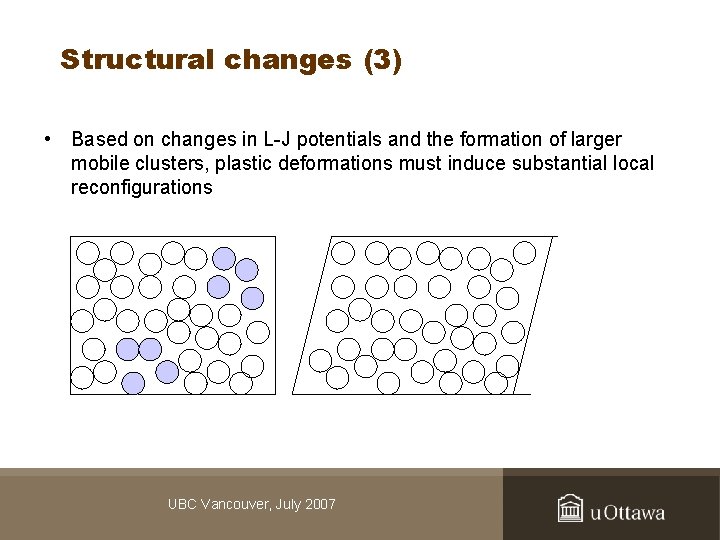

Structural changes (3) • Based on changes in L-J potentials and the formation of larger mobile clusters, plastic deformations must induce substantial local reconfigurations UBC Vancouver, July 2007

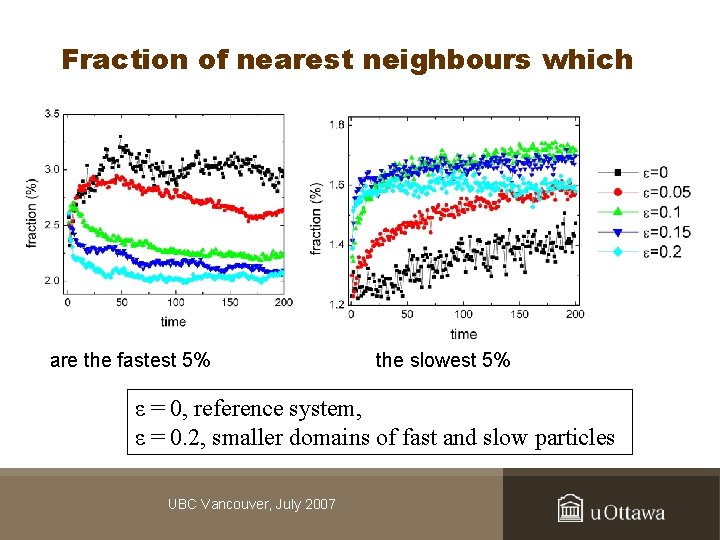

Fraction of nearest neighbours which are the fastest 5% the slowest 5% ε = 0, reference system, ε = 0. 2, smaller domains of fast and slow particles UBC Vancouver, July 2007

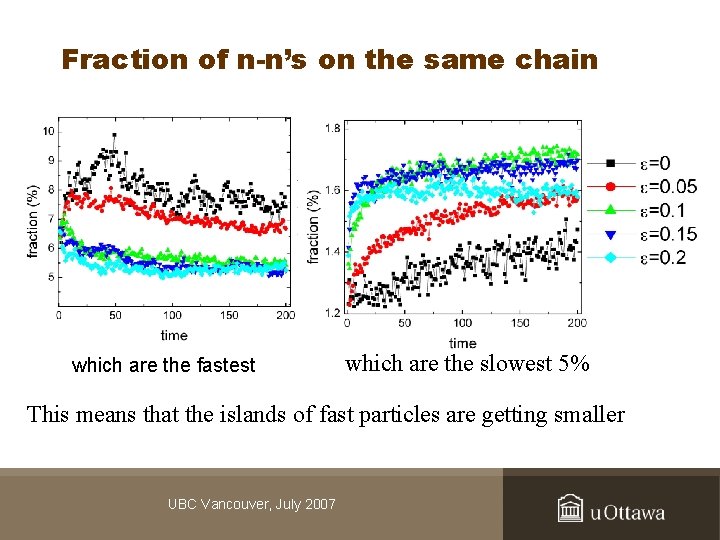

Fraction of n-n’s on the same chain which are the fastest which are the slowest 5% This means that the islands of fast particles are getting smaller UBC Vancouver, July 2007

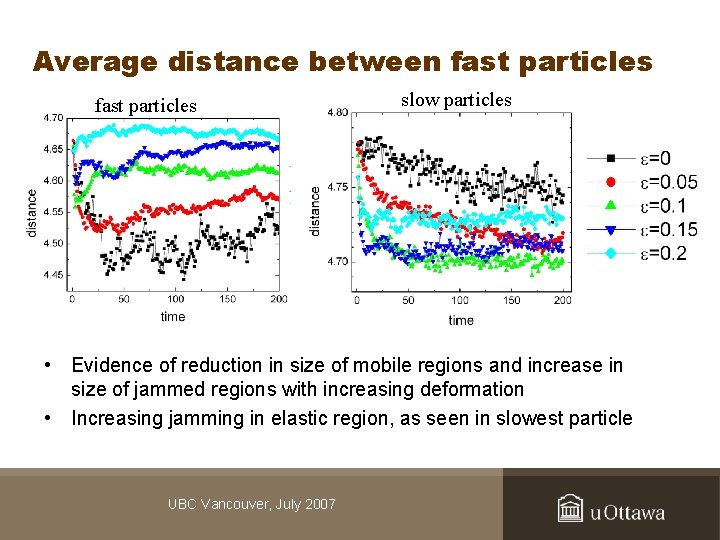

Average distance between fast particles slow particles • Evidence of reduction in size of mobile regions and increase in size of jammed regions with increasing deformation • Increasing jamming in elastic region, as seen in slowest particle UBC Vancouver, July 2007

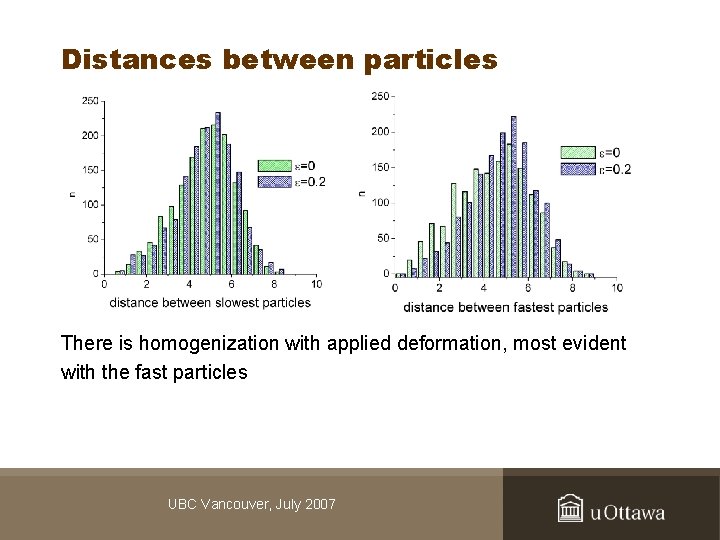

Distances between particles There is homogenization with applied deformation, most evident with the fast particles UBC Vancouver, July 2007

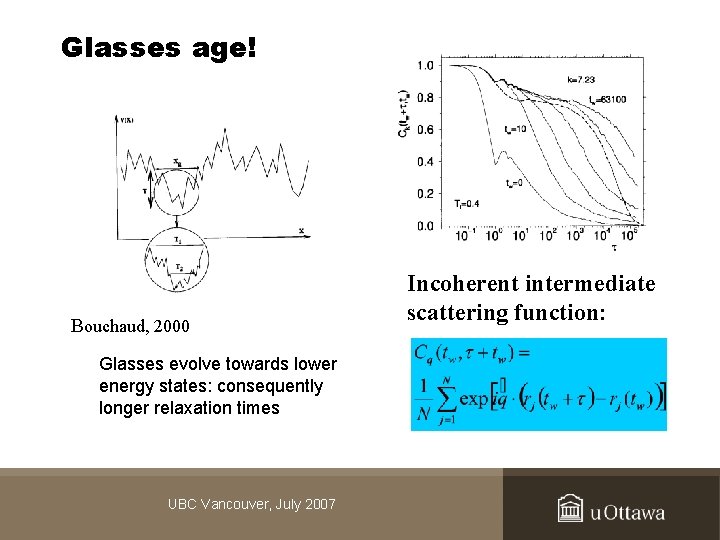

Glasses age! Kob, 2000 Bouchaud, 2000 Glasses evolve towards lower energy states: consequently longer relaxation times UBC Vancouver, July 2007 Incoherent intermediate scattering function:

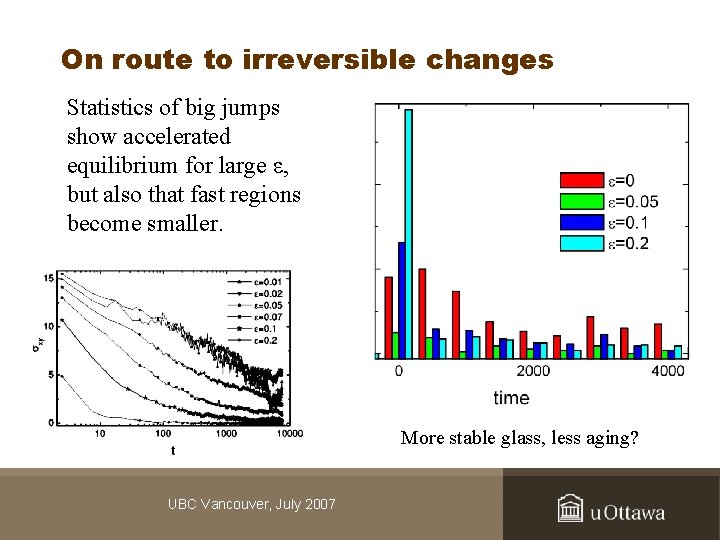

On route to irreversible changes Statistics of big jumps show accelerated equilibrium for large ε, but also that fast regions become smaller. More stable glass, less aging? UBC Vancouver, July 2007

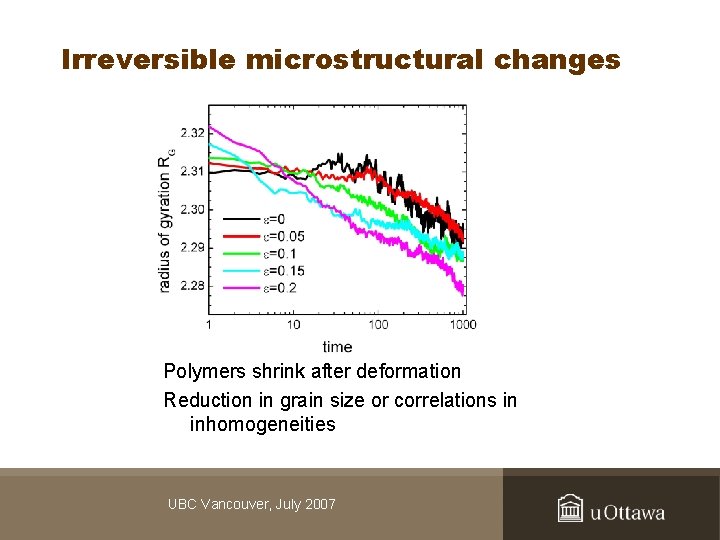

Irreversible microstructural changes Polymers shrink after deformation Reduction in grain size or correlations in inhomogeneities UBC Vancouver, July 2007

Conclusion • We have presented attempts to characterize the effect of deformations on the structure of the glass that did not require huge computing times • The net effect of deformations appears to be connected to general “jamming” phenomena, and what the deformations can do to un-jam the structure • What they reveal is a more homogeneous glass with a smaller “grain” structure • More studies are required (highly computer intensive) • Currently working on applying oscillating shear to the glass, and monitoring the aging of the glasses prepared by shear deformation UBC Vancouver, July 2007

Heterogeneous dynamics • • The non-Gaussian parameter α 2(t) indicates a decrease in deviations from Gaussian behavior Deviations from a Gaussian distribution become less apparent for plastic deformations UBC Vancouver, July 2007

Conclusion With permanent crosslinks • • The location of the onset of rigidity is well-defined in networks with permanent links. In networks with permanent links, the percolation model is as credible, if not more, than any other. Experimental and theoretical issues such as effects of the hard core to be resolved Temperature driven system • Location of the onset of rigidity determined to be below the glass transition, no clearly defined length scales. Questions of time scales and definition • Under applied stress, permanent changes can occur, notions of “overaging” and “rejuvenation”. What are the structure and the properties of the “overaged” glass? UBC Vancouver, July 2007

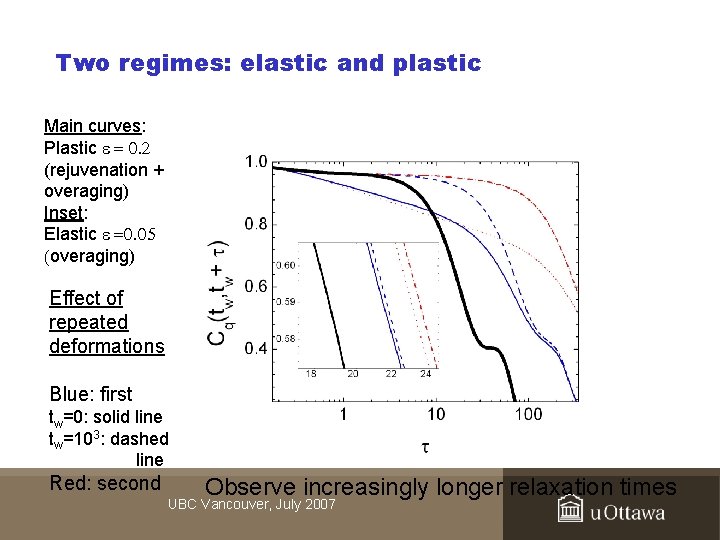

Discussion on “overaging” • Evidence that the phenomenon is universal (Experiments on colloids, computer simulations • • • Shear increases ordering Two distinct regimes: elastic and plastic Repeated applications of plastic deformation, in particular, yield increasingly longer relaxation times Is this a mean to achieve more homogeneous glasses? )changes in relaxation times not significant) • on a polymer glass, similar results on LJ binary mixtures) UBC Vancouver, July 2007

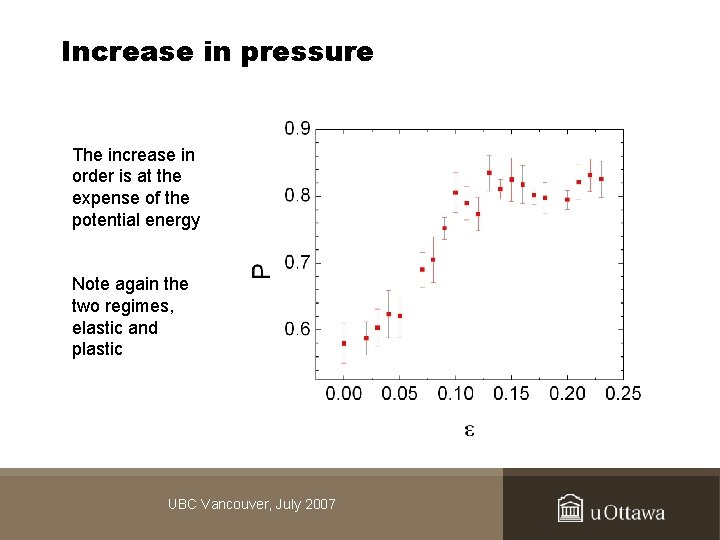

Increase in pressure The increase in order is at the expense of the potential energy Note again the two regimes, elastic and plastic UBC Vancouver, July 2007

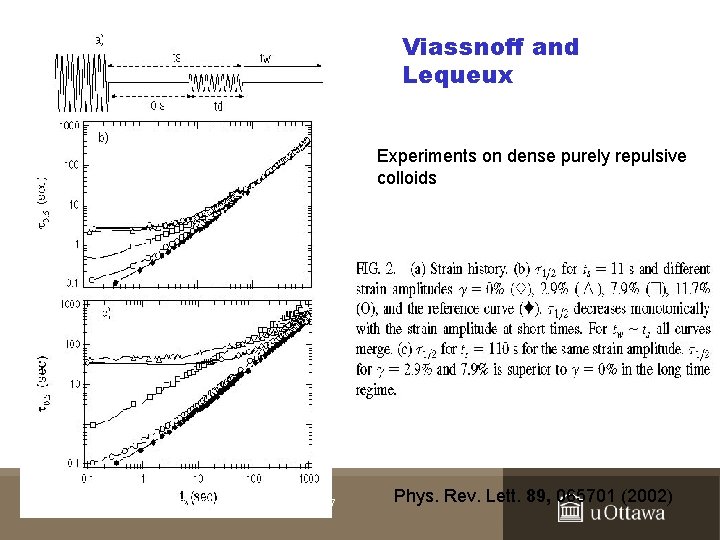

Viassnoff and Lequeux Experiments on dense purely repulsive colloids UBC Vancouver, July 2007 Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 065701 (2002)

Mechanical vs entropic rigidity Rigidity at T=0 K (Rigidity Theory and Applications, Thorpe and Duxbury eds. , Plenum 1999) In essence, in unstressed systems, multiple connectivity is required for rigidity Mean field model (Maxwell counting), the onset of rigidity occurs at the point where the number of degrees of freedom equals the number of constraints (stretching and bending) UBC Vancouver, July 2007

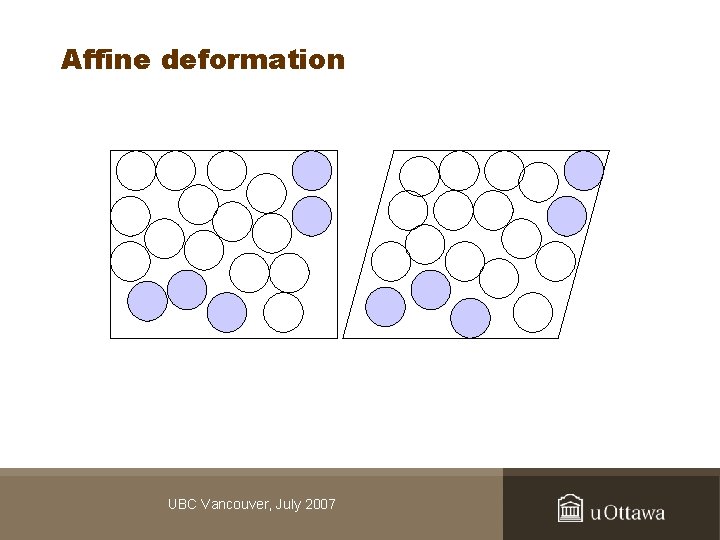

Affine deformation UBC Vancouver, July 2007

Two regimes: elastic and plastic Main curves: Plastic = 0. 2 (rejuvenation + overaging) Inset: Elastic =0. 05 (overaging) Effect of repeated deformations Blue: first tw=0: solid line tw=103: dashed line Red: second Observe increasingly longer relaxation times UBC Vancouver, July 2007

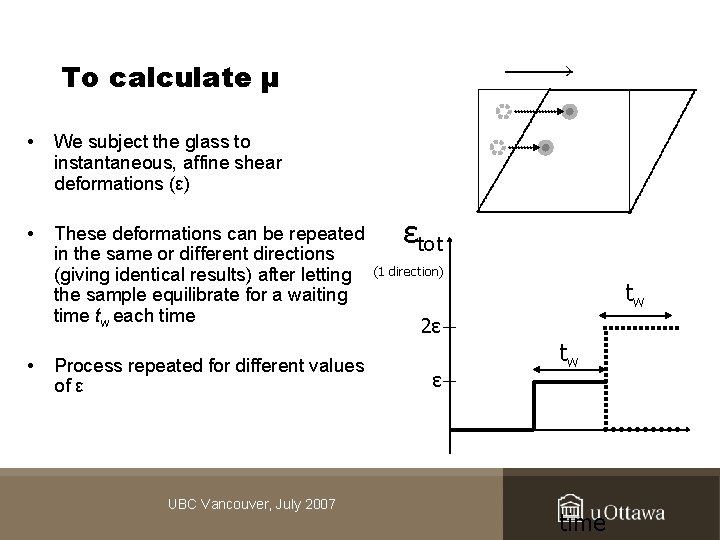

To calculate µ • We subject the glass to instantaneous, affine shear deformations (ε) • These deformations can be repeated in the same or different directions (giving identical results) after letting the sample equilibrate for a waiting time tw each time • Process repeated for different values of ε UBC Vancouver, July 2007 εtot (1 direction) 2ε ε tw tw time

UBC Vancouver, July 2007

- Slides: 52