METL 1313 Introduction to Corrosion Lecture 2 Basic

METL 1313 Introduction to Corrosion Lecture 2 Basic Electricity

Basic Electricity �Corrosion and cathodic protection are electrochemical phenomena. �Electrical instruments are often used in corrosion testing. �The need to understand various electrical terms, laws, circuits and equipment is paramount when working with corrosion and cathodic protection.

Basic Electricity �Knowledge of the above is essential for anyone entering the field of corrosion/cathodic protection technology.

Electrochemistry �The branch of chemistry that deals with the chemical changes produced by electricity and the production of electricity by chemical changes.

Electrons �Subatomic particles that revolve around a nucleus and carry a negative charge. �They also help hold matter together, similar to mortar in a brick wall.

Voltage �Voltage or potential, is an electromotive force or a difference in potential expressed in volts. �Voltage is the energy that puts charges in motion. �Can also be defined as electrical pressure.

Voltage �Voltage is measured in volts, millivolts, and microvolts. �In corrosion work all three units are used. �The following shows their relationship: � 1. 000 volt 1000 millivolts � 0. 100 volt 100 millivolts � 0. 010 volt 10 millivolts � 1 millivolt 0. 001 volt � 0. 000001 volt 1 microvolt

Voltage �Common symbols for voltage are: �Emf electromotive force - any voltage unit �E or e voltage across a source of electrical energy (e. g. battery, pipe-to-soil potential) �V or v voltage across a sink of electrical energy (e. g. resistor)

Voltage �You will be concerned with voltage when making various measurements in corrosion and cathodic protection work. �Among those voltages measured are pipe-tosoil potentials, voltage drops across resistances or along pipelines.

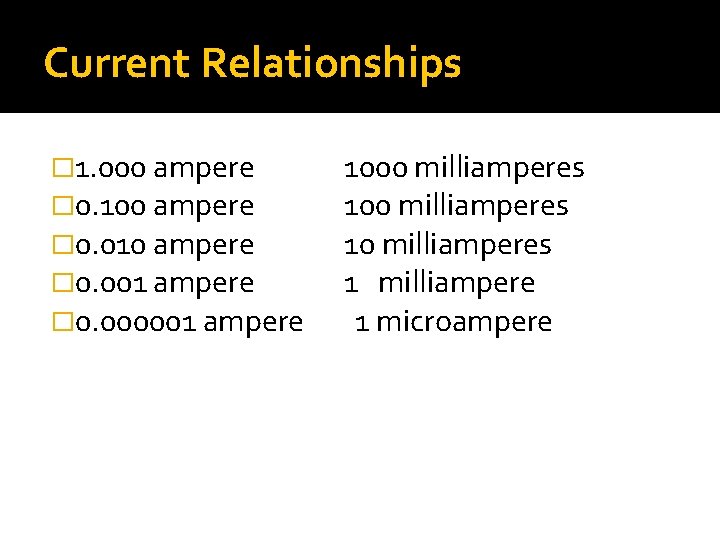

Current �Current is the flow of charges along a conducting path and is measured in amperes. �Current is frequently abbreviated as amps, milliamps, or microamps. �In corrosion work we use all three units. �The following shows their relationship:

Current Relationships � 1. 000 ampere � 0. 100 ampere � 0. 010 ampere � 0. 001 ampere � 0. 000001 ampere 1000 milliamperes 10 milliamperes 1 milliampere 1 microampere

Ampere �The ampere is the common unit of current, and is equal to a flow rate of charge of 1 coulomb per second. �One coulomb is the unit of charge carried by 6. 24 x 1018 electron charges.

Current �Common symbols for current flow are: �I any amperage unit �m. A milliamperes or milliamps �μA microamperes or microamps �Direct current flows constantly in one direction in a circuit. �Alternating current regularly reverses direction of flow, commonly 100 or 120 times per second.

Resistance �Resistance is the opposition or measure of difficulty that electric charges encounter when moving through a material. �The resistance of a conductor is defined as the ratio of the voltage applied to the electric current which flows through it. �The ohm is the common unit of resistance measurement.

Resistance �Resistance may also be measured in milliohms (0. 001 ohm) or in megohms (1, 000 ohms).

Resistance �Common symbols for resistance are: �R, r �Ω (Greek letter omega) �Resistance is very important in corrosion and cathodic protection work.

Resistivity �The resistance of a conductor of unit length and unit cross-sectional area. �The symbol used for resistivity is the Greek letter (ρ) pronounced rho).

Resistivity � An intrinsic property that quantifies how strongly a given material opposes the flow of electric current. � If the resistivity of a material is known, the resistance of a conductor such as a cable or pipeline of known length and cross-sectional area can be calculated from the formula: R = ρ x L / A

Resistivity �Resistivity is constant for a given material.

Cross-sectional Area Calculations �Square or rectangular shape: A (cm 2) = h x w where: h = height (cm) w = width (cm) �Circular shape: A (cm 2) = πr 2 where: r = radius (cm)

Resistance to Current Flow �Resistance to current flow is lowest for: �Low-resistivity (high-conductivity) media �Short length for current flow �Large cross-sectional area for current flow

Resistance to Current Flow �Resistance will be greatest for: �High-resistivity (low-conductivity) media �Long path length for current flow �Small cross-sectional area for current flow

Resistivity of Common Materials Material Resistivity (ohm-cm) Aluminum Carbon Copper Iron Steel Lead Magnesium Zinc Ice Rubber Water (tap) Water (sea) Soil (varies) 2. 69 x 10 -6 3. 50 x 10 -3 1. 72 x 10 -6 9. 80 x 10 -6 18. 00 x 10 -6 2. 20 x 10 -5 4. 46 x 10 -6 5. 75 x 108 7. 20 x 1016 3. 00 x 103 3. 00 x 101 1. 00 x 102 to 5 x 105

Scientific Notation �Scientific notation uses exponents where the multiplier 10 is raised to a power. �For example: 1 x 102 = 1 x 10 = 100 1 x 10 -2 = 1 x. 1 =. 01

Resistivity �The common unit of resistivity measurement for an electrolyte is ohm-centimeter. �Electrolytes prevalent in corrosion and cathodic protection work includes soils and liquids (water).

Resistivity �Since electrolytes do not usually have fixed dimensions (the earth or a body of water, for example), resistivity is usually defined as the resistance between two parallel faces of a cube 1 cm on each side or 1 cm square.

Resistivity �Electrolyte resistivities vary greatly. Some electrolytes have resistivities as low as 30 ohm-cm (seawater) and as high as 500, 000 ohm-cm (dry sand). �The resistivity of an electrolyte is an important factor when evaluating the corrosivity of an environment and designing cathodic protection systems.

Electric Circuit �An electric circuit is the path followed by an electric current. �Electrical laws govern the relationships in electric circuits.

Ohm’s Law Relationships �Where force) E or V = Voltage (electromotive I = Current (amperes) R = Resistance (ohms) E or V = IR I = E/R R = E/I

Ohm’s Law �If two of the three electrical variables are known, you can compute third. �If you have measured the voltage and current in a cathodic protection circuit, for example, you can easily calculate the circuit resistance.

Ohm’s Law Triangle �An easy way to use the Ohm’s Law triangle is to place your thumb over the quantity you are seeking. �To solve for resistance, as in the above example, place your thumb over the R and you can see that R = E/I. �Solve for voltage by placing the thumb over the E and see that E = I x R.

- Slides: 31