Methods used in virology Virology is a huge

- Slides: 47

Methods used in virology Virology is a huge subject and uses a wide range of methods. Many of the techniques of molecular biology and cell biology are used, and constraints on space permit us to mention only some of them. Much of the focus of this chapter is on methods that are unique to virology. Many of these methods are used, not only in virus research, but also in the diagnosis of virus diseases of humans, animals and plants.

Cultivation of viruses • Virologists need to be able to produce the objects of their study, so a wide range of procedures has been developed for cultivating viruses. Virus cultivation is also referred to as propagation or growth. • Phages are supplied with bacterial cultures, plant viruses may be supplied with specially cultivated plants or with cultures of protoplasts (plant cells from which the cell wall has been removed), while animal viruses may be supplied with whole organisms, such as mice, eggs containing chick embryos(figure 2 -1) or insect larvae. For the most part, however, animal viruses are grown in cultured animal cells.

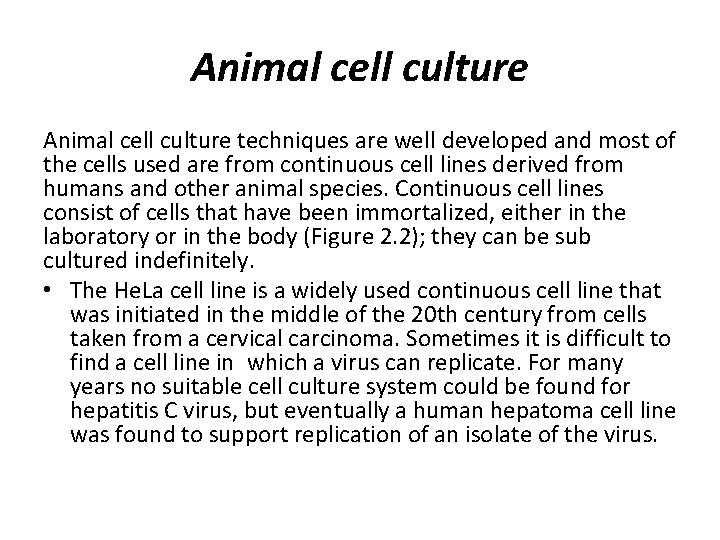

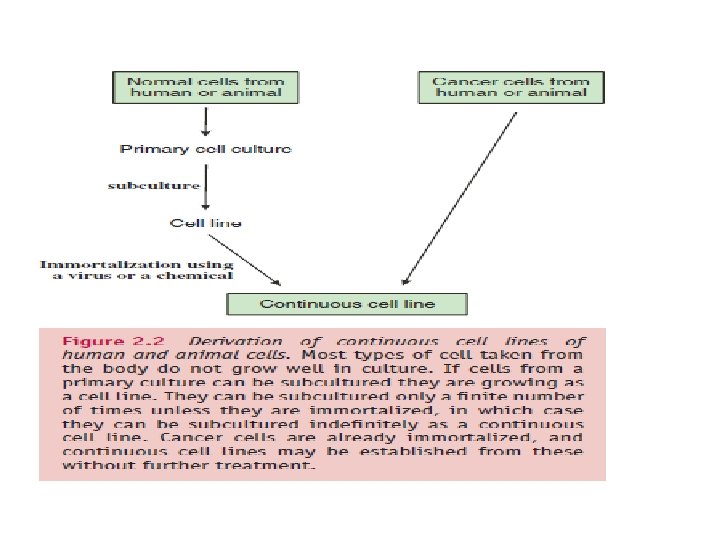

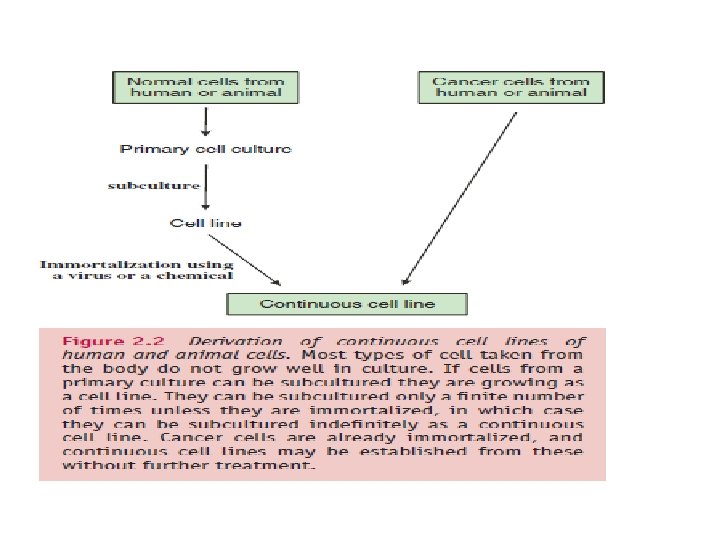

Animal cell culture techniques are well developed and most of the cells used are from continuous cell lines derived from humans and other animal species. Continuous cell lines consist of cells that have been immortalized, either in the laboratory or in the body (Figure 2. 2); they can be sub cultured indefinitely. • The He. La cell line is a widely used continuous cell line that was initiated in the middle of the 20 th century from cells taken from a cervical carcinoma. Sometimes it is difficult to find a cell line in which a virus can replicate. For many years no suitable cell culture system could be found for hepatitis C virus, but eventually a human hepatoma cell line was found to support replication of an isolate of the virus.

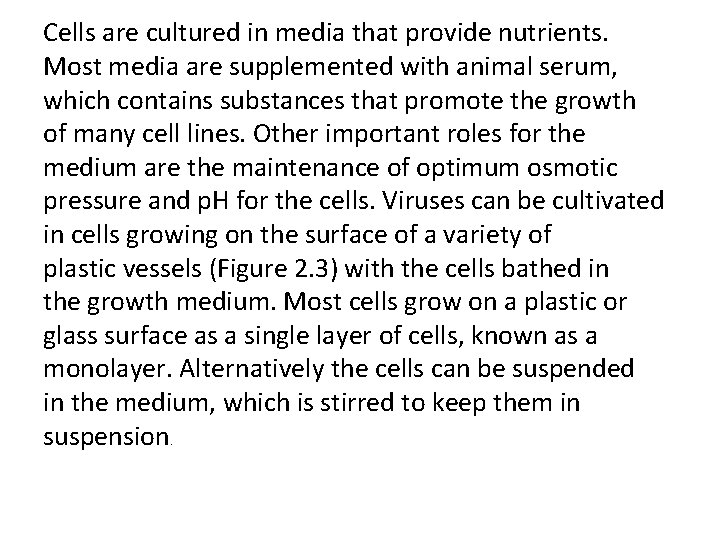

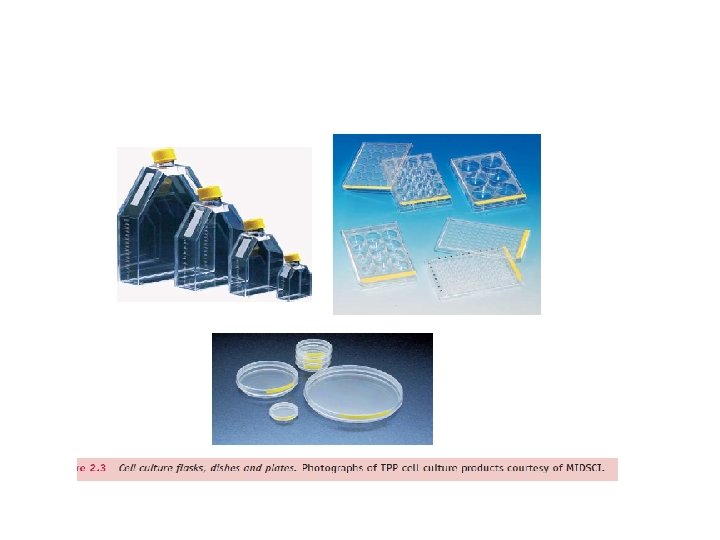

Cells are cultured in media that provide nutrients. Most media are supplemented with animal serum, which contains substances that promote the growth of many cell lines. Other important roles for the medium are the maintenance of optimum osmotic pressure and p. H for the cells. Viruses can be cultivated in cells growing on the surface of a variety of plastic vessels (Figure 2. 3) with the cells bathed in the growth medium. Most cells grow on a plastic or glass surface as a single layer of cells, known as a monolayer. Alternatively the cells can be suspended in the medium, which is stirred to keep them in suspension.

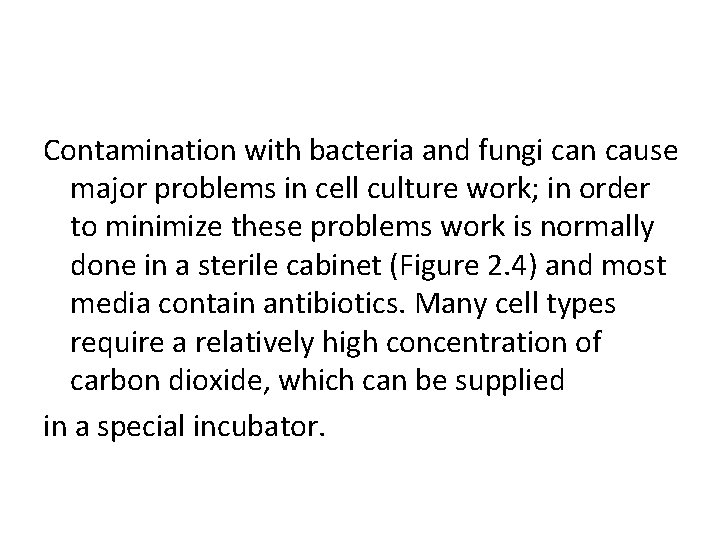

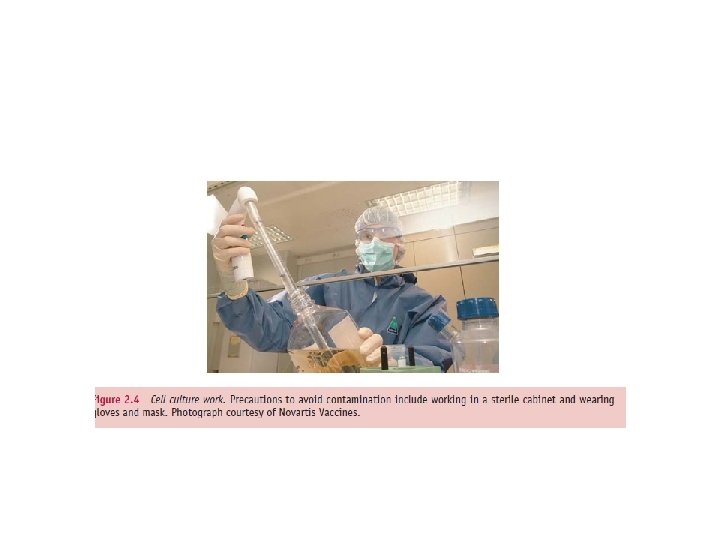

Contamination with bacteria and fungi can cause major problems in cell culture work; in order to minimize these problems work is normally done in a sterile cabinet (Figure 2. 4) and most media contain antibiotics. Many cell types require a relatively high concentration of carbon dioxide, which can be supplied in a special incubator.

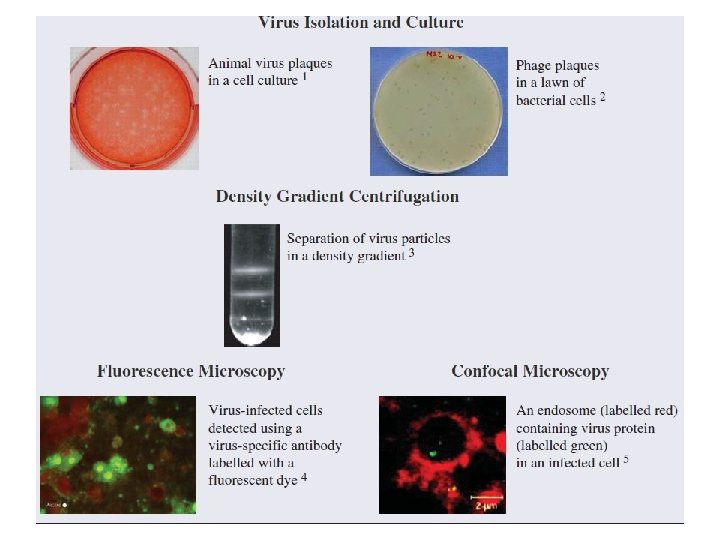

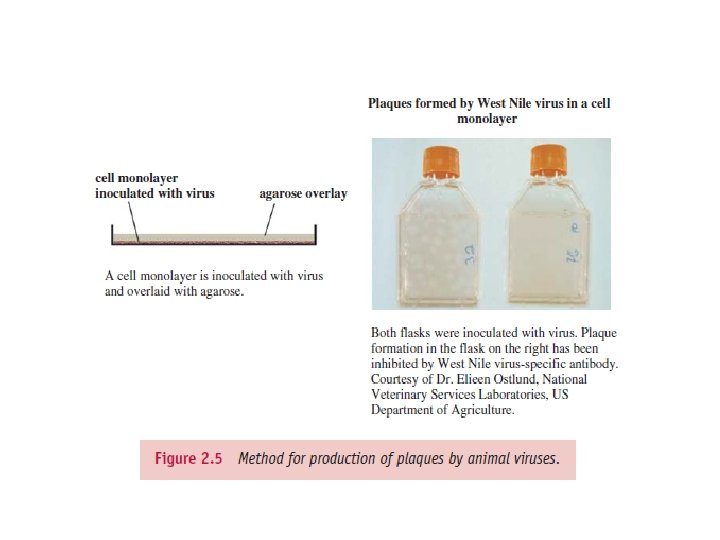

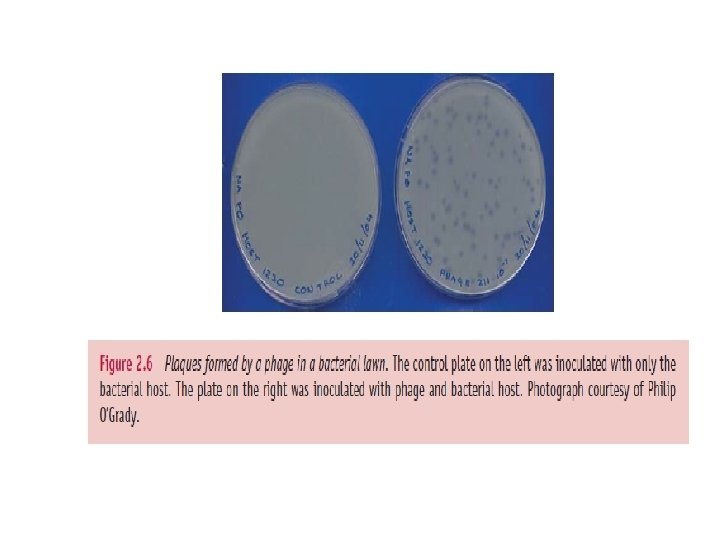

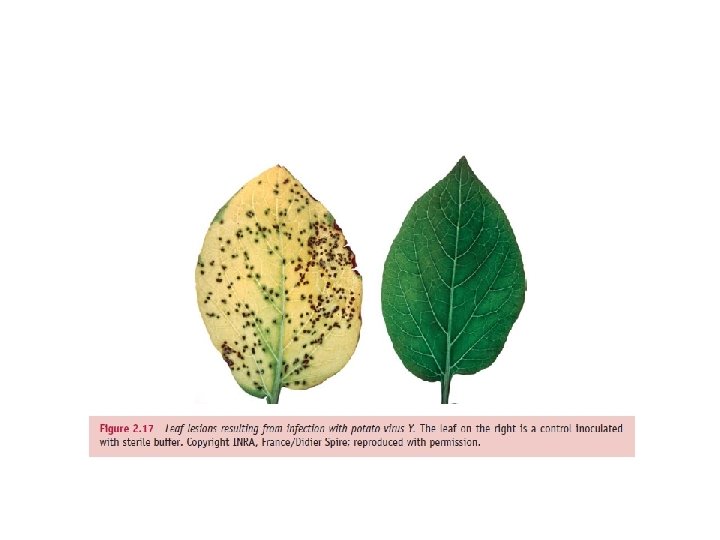

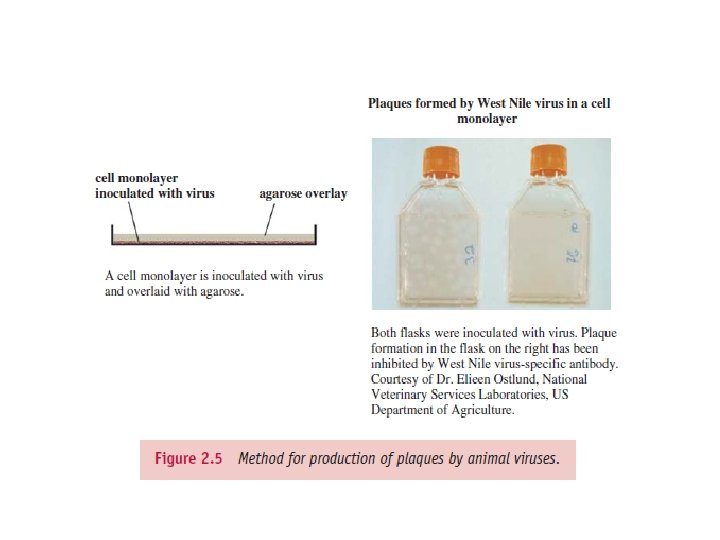

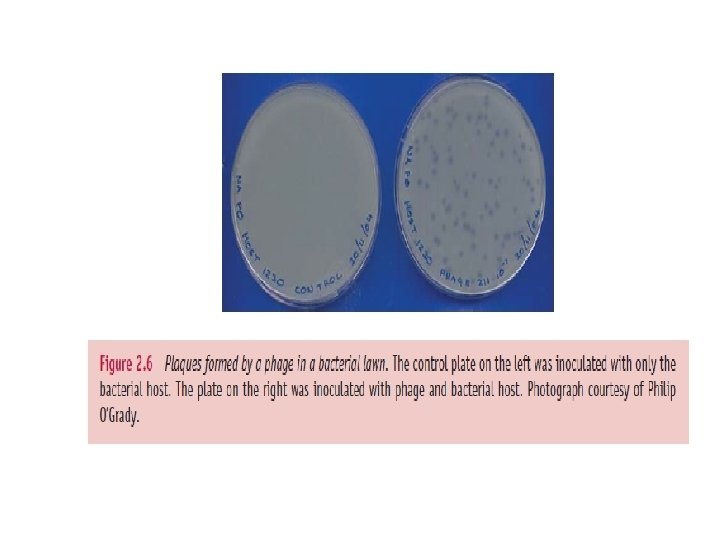

Isolation of viruses Many viruses can be isolated as a result of their ability to form discrete visible zones (plaques) in layers of host cells. If a confluent layer of cells is inoculated with virus at a concentration so that only a small proportion of the cells is infected, then plaques may form where areas of cells are killed or altered by the virus infection. Each plaque is formed when infection spreads radially from an infected cell to surrounding cells. Plaques can be formed by many animal viruses in monolayers if the cells are overlaid with agarose gel to maintain the progeny virus in a discrete zone (Figure 2. 5). Plaques can also be formed by phages in lawns of bacterial growth (Figure 2. 6).

It is generally assumed that a plaque is the result of the infection of a cell by a single virion. If this is the case then all virus produced from virus in the plaque should be a clone, in other words it should be genetically identical. This clone can be referred to as an isolate, and if it is distinct from all other isolates it can be referred to as a strain. This is analogous to the derivation of a bacterial strain from a colony on an agar plate. there is a possibility that a plaque might be derived from two or more virions so, to increase the probability that a genetically pure strain of virus has been obtained, material from a plaque can be inoculated onto further monolayers and virus can be derived from an individual plaque. The virus is said to have been plaque purified.

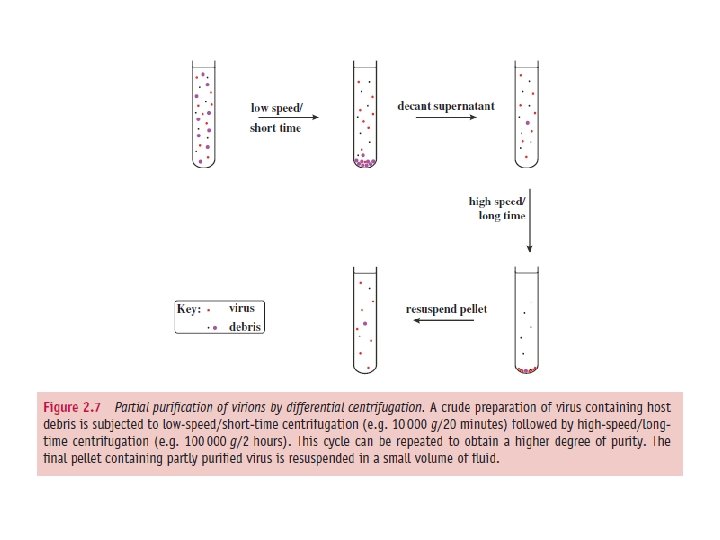

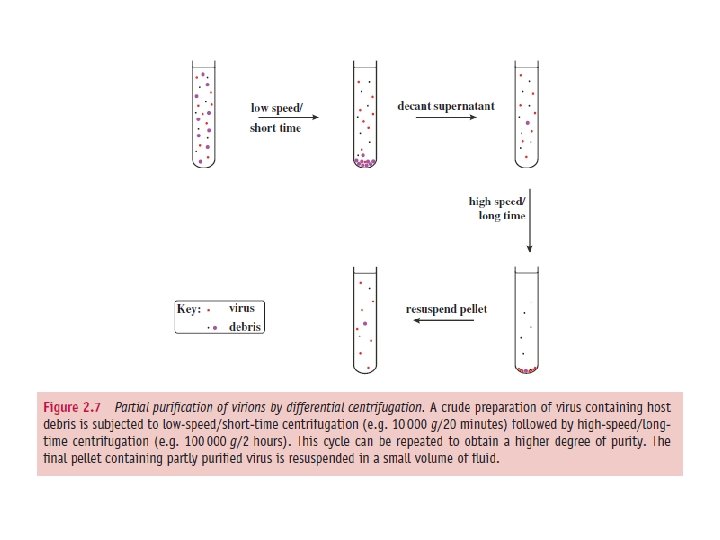

Centrifugation After a virus has been propagated it is usually necessary to remove host cell debris and other contaminants before the virus particles can be used for laboratory studies, for incorporation into a vaccine, or for some other purpose. Many virus purification procedures involve centrifugation; partial purification can be achieved by differential centrifugation and a higher degree of purity can be achieved by some form of density gradient centrifugation.

Differential centrifugation • Differential centrifugation involves alternating cycles of low-speed centrifugation, after which most of the virus is still in the supernatant, and high-speed centrifugation, after which the virus is in the pellet (Figure 2. 7).

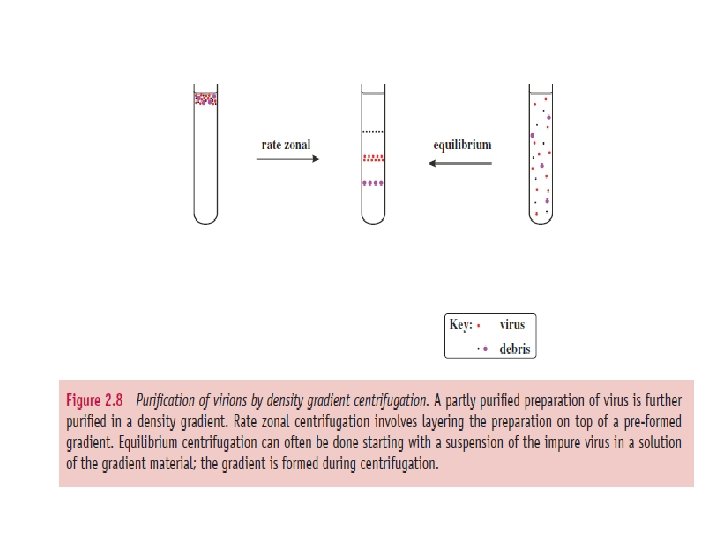

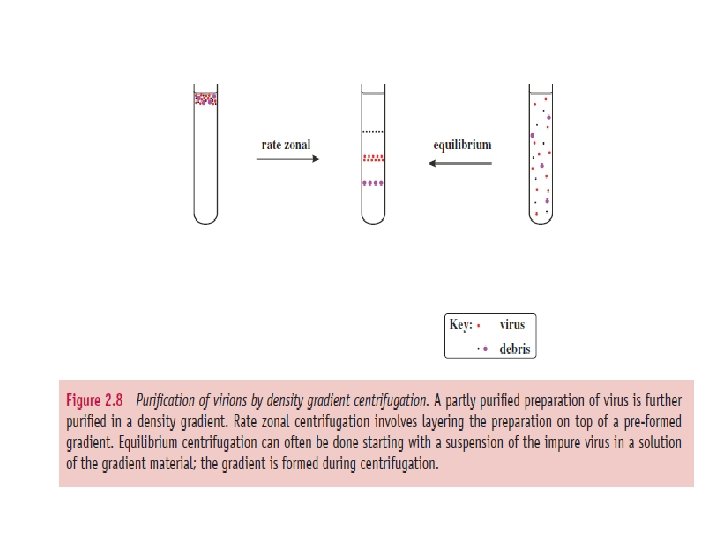

Density gradient centrifugation involves centrifuging particles (such as virions) or nucleic acids) in a solution of increasing concentration, and therefore density. The solutes used have high solubility: sucrose is commonly used. There are two major categories of density gradient centrifugation: rate zonal and equilibrium (isopycnic) centrifugation (Figure 2. 8).

In rate zonal centrifugation a particle moves through the gradient at a rate determined by its sedimentation coefficient, a value that depends principally on its size. Homogeneous particles, such as identical virions, should move as a sharp band that can be harvested after the band has moved part way through the gradient.

In equilibrium centrifugation a concentration of solute is selected to ensure that the density at the bottom of the gradient is greater than that of the particles/molecules to be purified. A particle/molecule suspended in the gradient moves to a point where the gradient density is the same as its own density. This technique enables the determination of the buoyant densities of nucleic acids and of virions. Buoyant densities of virions determined in gradients of caesium chloride are used as criteria in the characterization of viruses.

Structural investigations of cells and virions Light microscopy The sizes of most virions are beyond the limits of resolution of light microscopes, but light microscopy has useful applications in detecting virus-infected cells, for example by observing cytopathic effects or by detecting a fluorescent dye linked to antibody molecules that have bound to a virus antigen (fluorescence microscopy). Confocal microscopy is proving to be especially valuable in virology. The principle of this technique is the use of a pinhole to exclude light from outof-focus regions of the specimen. Most confocal microscopes scan the specimen with a laser, producing exceptionally clear images of thick specimens and of fluorescing specimens.

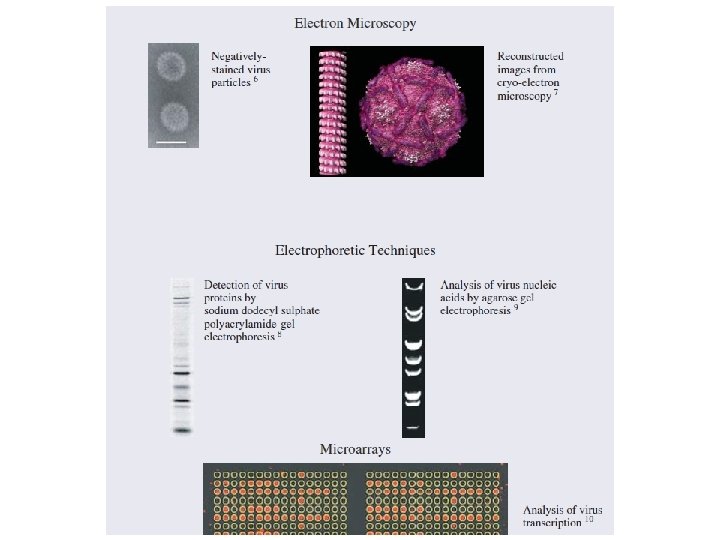

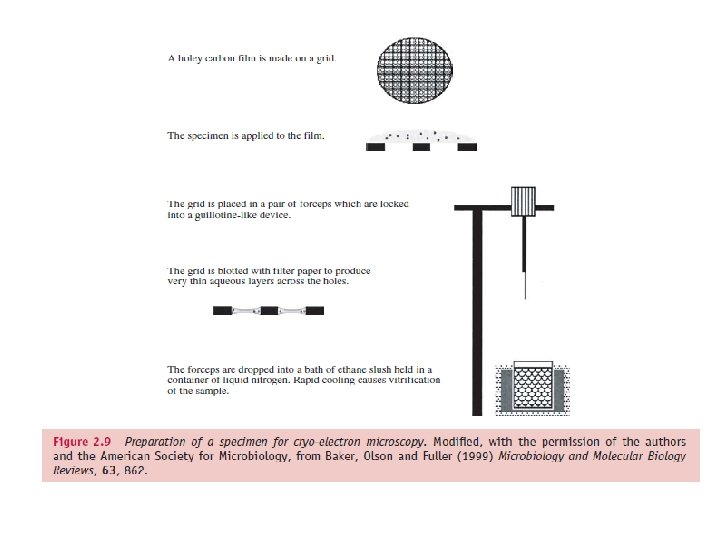

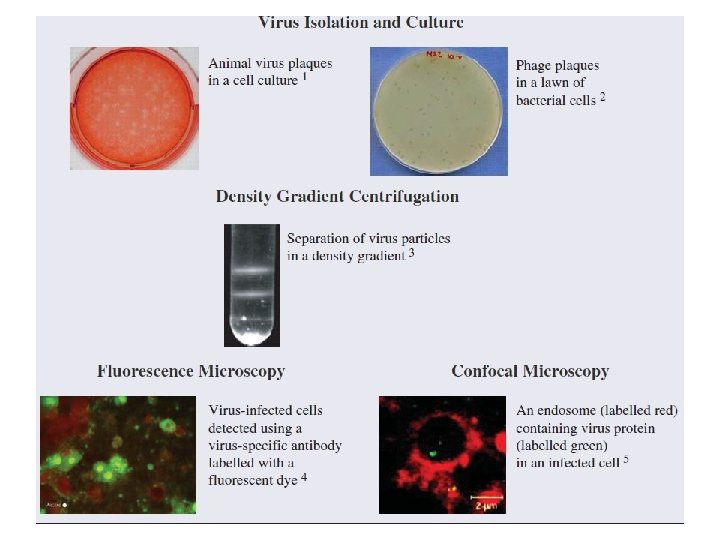

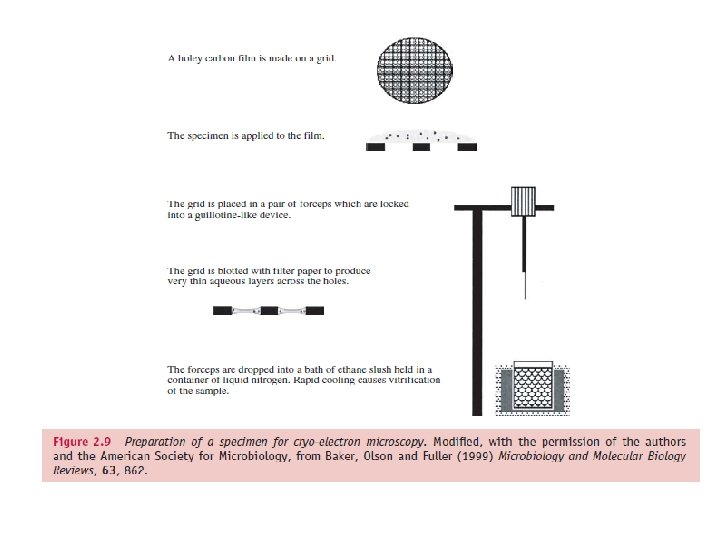

Cryo-electron microscopy techniques are more recent. In these a wet specimen is rapidly cooled to a temperature below − 160 ◦C, freezing the water as a glasslike material, as in the method outlined in Figure 2. 9. The images are recorded while the specimen is frozen. They require computer processing in order to extract maximum detail, and data from multiple images are processed to reconstruct three-dimensional images of virus particles. This may involve averaging many identical copies or combining images into threedimensional density maps (tomograms).

X-ray crystallography is another technique that is revealing detailed information about the three dimensional structures of virions (and DNA, proteins and DNA–protein complexes). This technique requires the production of a crystal of the virions or molecules under study. The crystal is placed in a beam of Xrays, which are diffracted by repeating arrangements of molecules/atoms in the crystal. Analysis of the diffraction pattern allows the relative positions of these molecules/atoms to be determined.

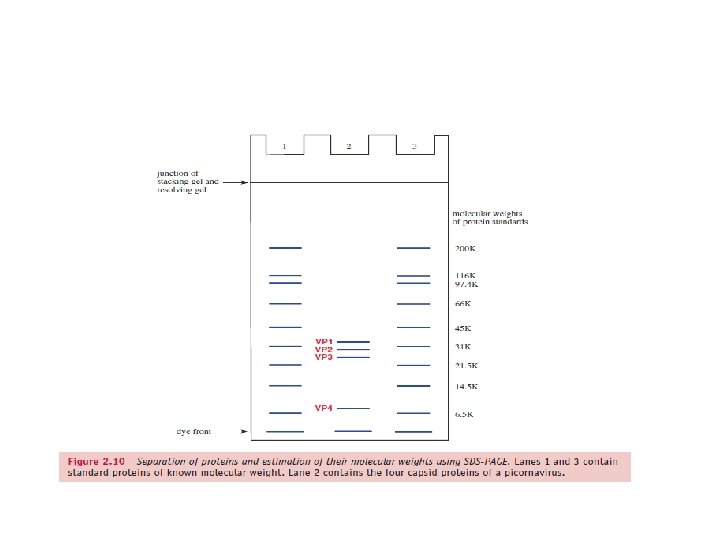

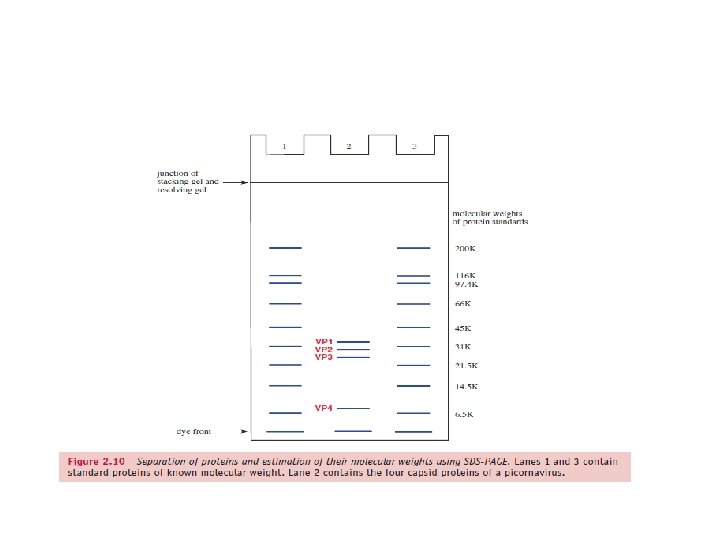

Electrophoretic techniques Mixtures of proteins or nucleic acids can be separated by electrophoresis in a gel composed of agarose or polyacrylamide. In most electrophoretic techniques each protein or nucleic acid forms a band in the gel. Electrophoresis can be performed under conditions where the rate of movement through the gel depends on molecular weight. The molecular weights of the protein or nucleic acid molecules can be estimated by comparing the positions of the bands with positions of bands formed by molecules of known molecular weight electrophoresed in the same gel. The technique for estimating molecular weights of proteins is polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the presence of the detergent sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS-PAGE; Figure 2. 10).

Detection of viruses and virus components A wide range of techniques has been developed for the detection of viruses and virus components and many of them are used in laboratories involved with diagnosis of virus diseases. The techniques can be arranged in four categories: detection of (1) virions, (2) virus infectivity, (3) virus antigens and (4) virus nucleic acids.

Detection of virions Specimens can be negatively stained (Section 2. 5) and examined in an electron microscope for the presence of virions. Limitations to this approach are the high costs of the equipment and limited sensitivity; the minimum detectable concentration of virions is about 106/ml. An example of an application of this technique is the examination of faeces from a patient with gastroenteritis for the presence of rotavirus particles.

Detection of infectivity using cell cultures Not all virions have the ability to replicate in host cells. Those virions that do have this ability are said to be ‘infective’, and the term ‘infectivity’ is used to denote the capacity of a virus to replicate. Virions may be non-infective because they lack part of the genome or because they have been damaged. To determine whether a sample or a specimen contains infective virus it can be inoculated into a culture of cells, or a host organism, known to support the replication of the virus suspected of being present.

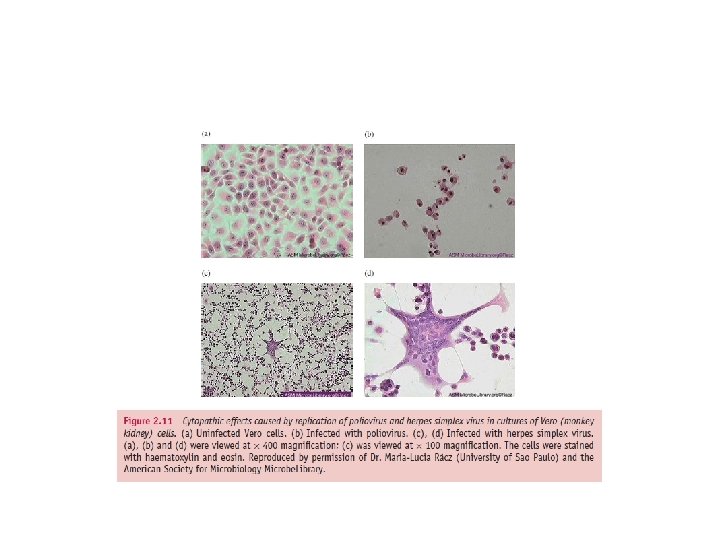

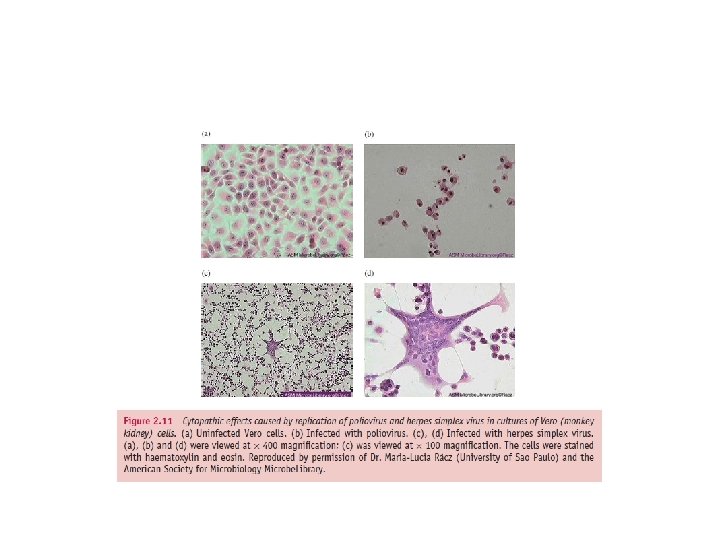

After incubation of an inoculated cell culture at an appropriate temperature it can be examined by light microscopy for characteristic changes in the appearance of the cells resulting from virus-induced damage. A change of this type is known as a cytopathic effect (CPE); examples of CPEs induced by poliovirus and herpes simplex virus can be seen in Figure 2. 11. The poliovirusinfected cells have shrunk and become rounded, while a multinucleated giant cell known as a syncytium (plural syncytia) has been formed by the fusion of membranes of herpes simplex virus-infected cells.

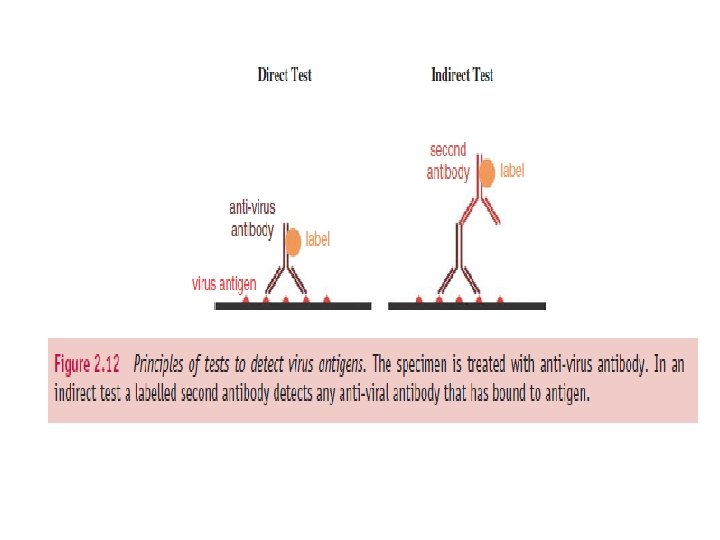

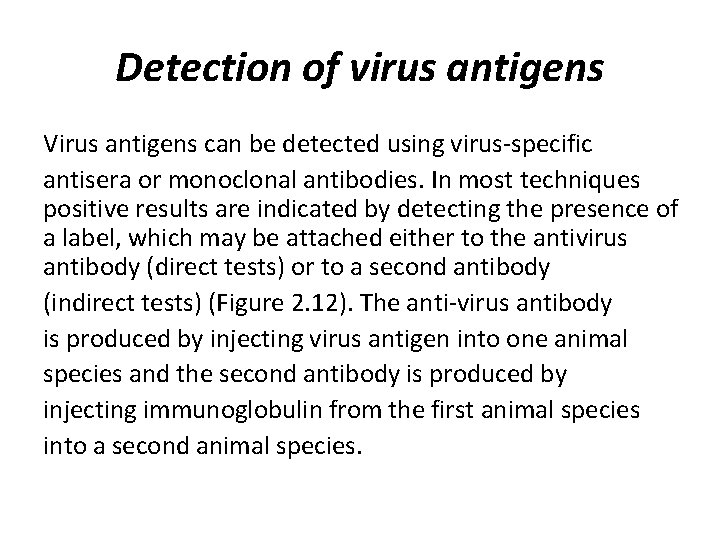

Detection of virus antigens Virus antigens can be detected using virus-specific antisera or monoclonal antibodies. In most techniques positive results are indicated by detecting the presence of a label, which may be attached either to the antivirus antibody (direct tests) or to a second antibody (indirect tests) (Figure 2. 12). The anti-virus antibody is produced by injecting virus antigen into one animal species and the second antibody is produced by injecting immunoglobulin from the first animal species into a second animal species.

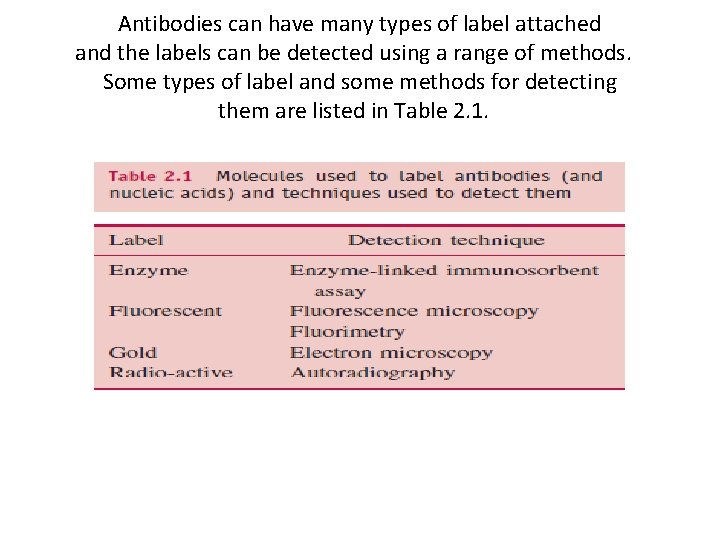

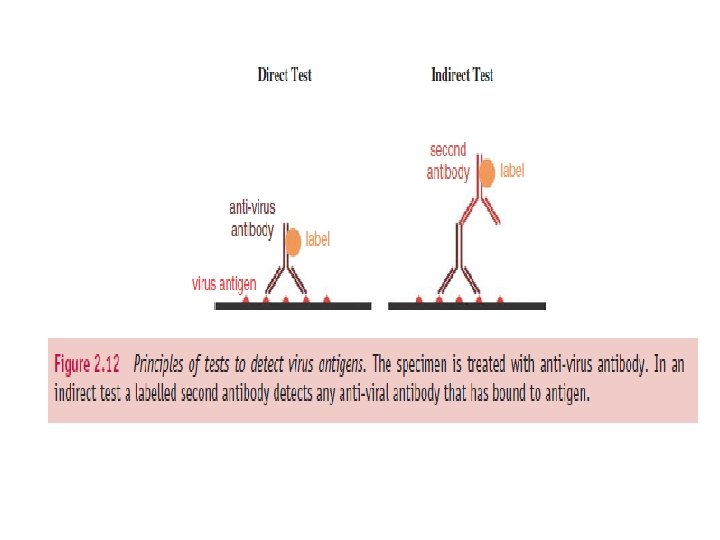

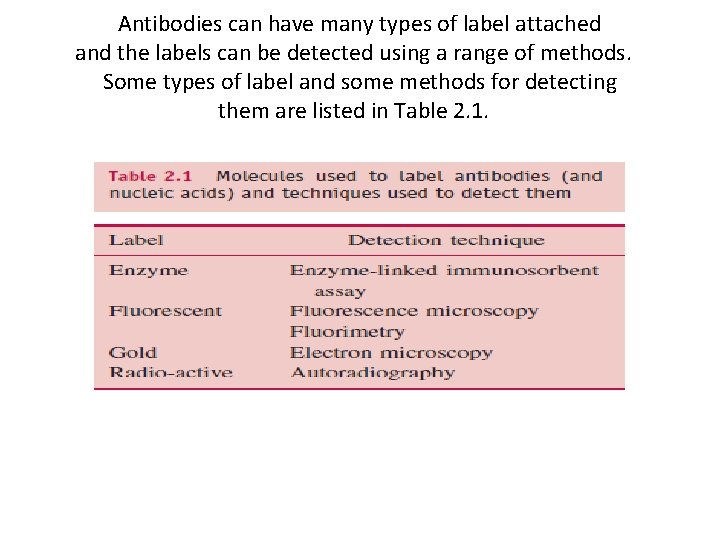

Antibodies can have many types of label attached and the labels can be detected using a range of methods. Some types of label and some methods for detecting them are listed in Table 2. 1.

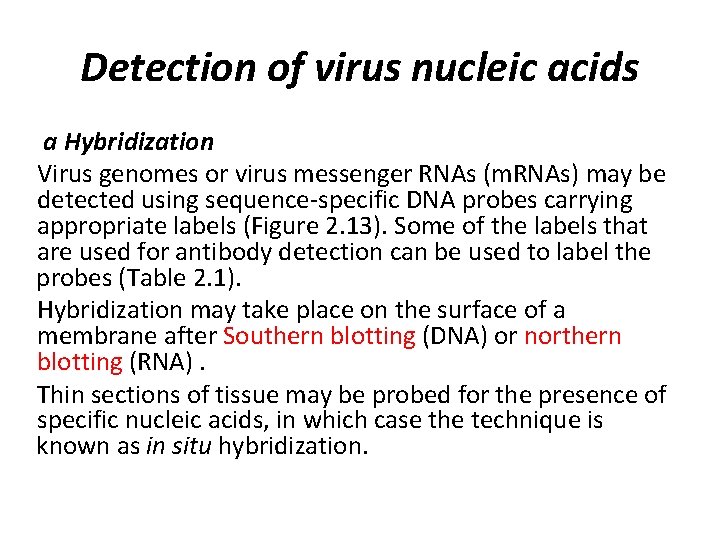

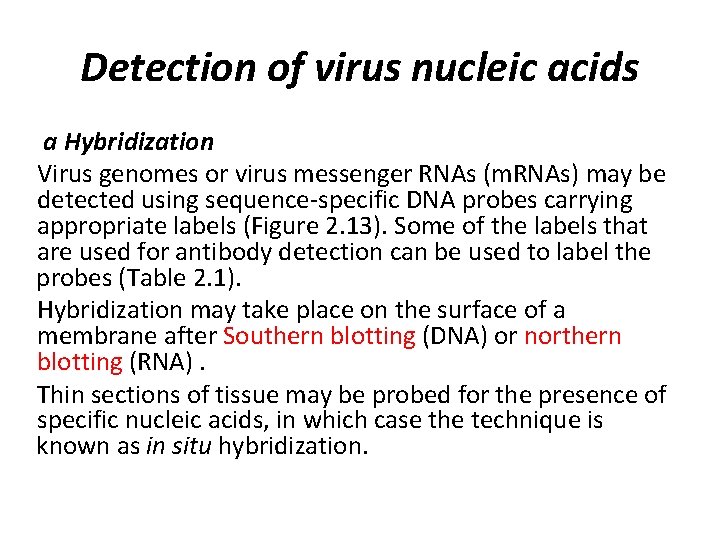

Detection of virus nucleic acids a Hybridization Virus genomes or virus messenger RNAs (m. RNAs) may be detected using sequence-specific DNA probes carrying appropriate labels (Figure 2. 13). Some of the labels that are used for antibody detection can be used to label the probes (Table 2. 1). Hybridization may take place on the surface of a membrane after Southern blotting (DNA) or northern blotting (RNA). Thin sections of tissue may be probed for the presence of specific nucleic acids, in which case the technique is known as in situ hybridization.

B- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) When a sample is likely to contain a low number of copies of a virus nucleic acid the probability of detection can be increased by amplifying virus DNA using a PCR, while RNA can be copied to DNA and amplified using a RT (reverse transcriptase)PCR. The procedures require oligonucleotide primers specific to viral sequences. An amplified product can be detected by electrophoresis in an agarose gel, followed by transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane, which is incubated with a labelled probe.

Infectivity assays An infectivity assay measures the titre (the concentration) of infective virus in a specimen or a preparation. Samples are inoculated into suitable hosts, in which a response can be observed if infective virus is present. Suitable hosts might be animals, plants or cultures of bacterial, plant or animal cells. Infectivity assays fall into two classes: quantitative and quantal.

Quantitative assays are those in which each host response can be any one of a series of values, such as a number of plaques (Section 2. 3). A plaque assay can be carried out with any virus that can form plaques, giving an estimate of the concentration of infective virus in plaqueforming units (pfu). The assay is done using cells grown in Petri dishes, or other appropriate containers, under conditions that will allow the formation of plaques. Cells are inoculated with standard volumes of virus dilutions. After incubation, dishes that received high dilutions of virus may have no plaques or very few plaques, while dishes that received low dilutions of virus may have very large numbers of plaques or all the cells may have lysed.

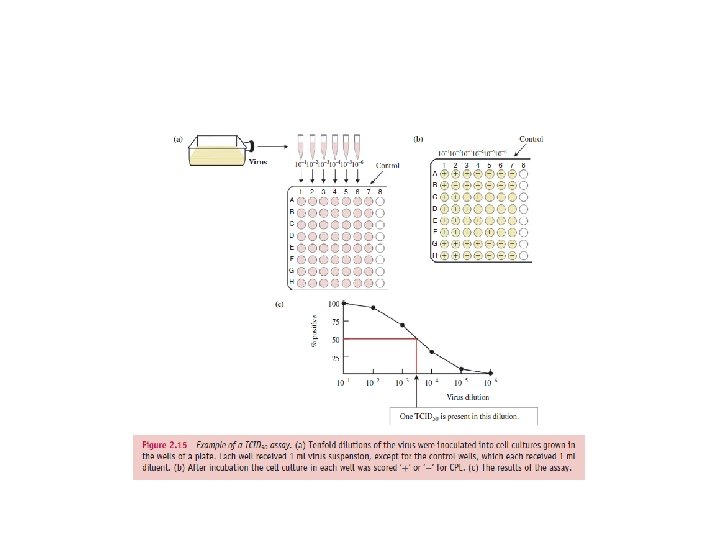

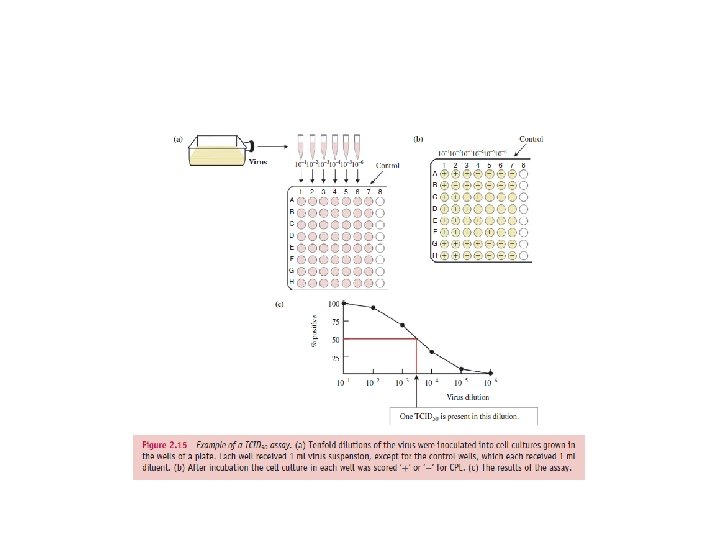

Quantal assays In a quantal assay each inoculated subject either responds or it does not; for example, an inoculated cell culture either develops a CPE or it does not; an inoculated animal either dies or it remains healthy. The aim of the assay is to find the virus dose that produces a response in 50 per cent of inoculated subjects.

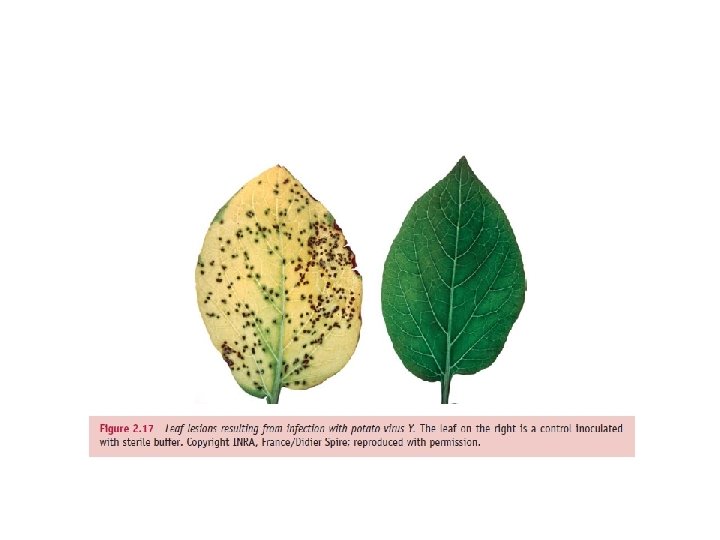

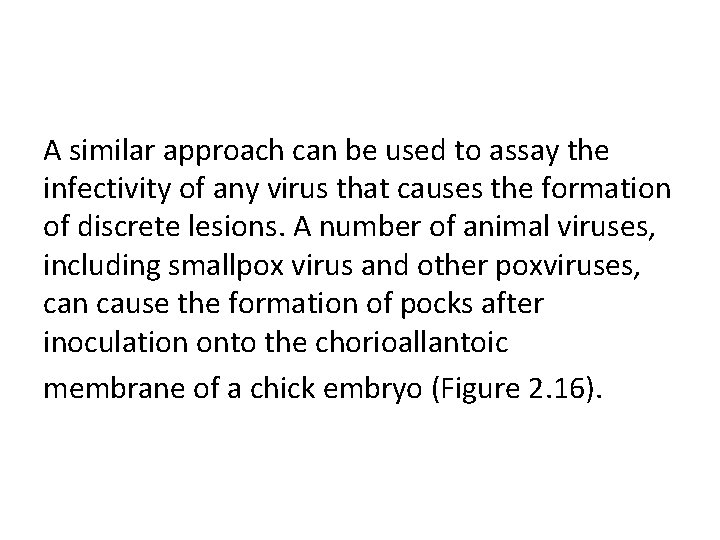

A similar approach can be used to assay the infectivity of any virus that causes the formation of discrete lesions. A number of animal viruses, including smallpox virus and other poxviruses, can cause the formation of pocks after inoculation onto the chorioallantoic membrane of a chick embryo (Figure 2. 16).

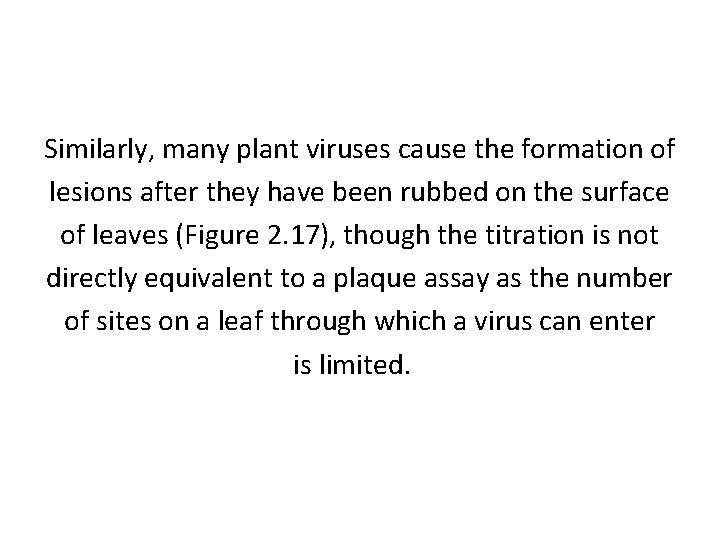

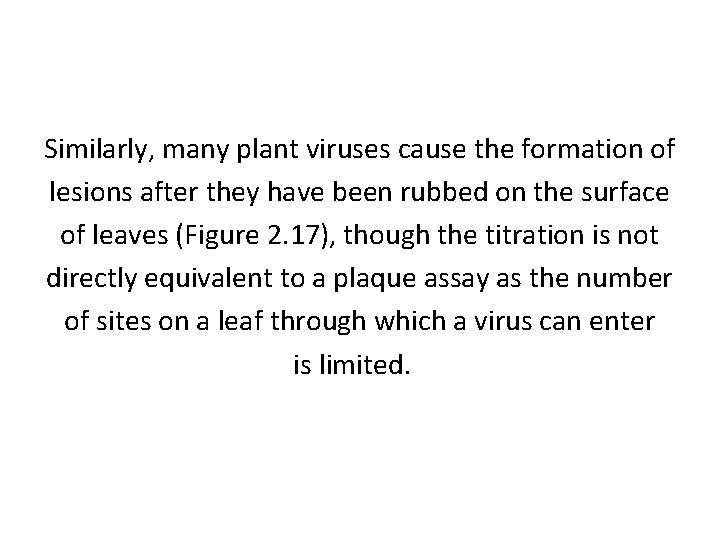

Similarly, many plant viruses cause the formation of lesions after they have been rubbed on the surface of leaves (Figure 2. 17), though the titration is not directly equivalent to a plaque assay as the number of sites on a leaf through which a virus can enter is limited.