Metabolic and Genetic Disorders Amyloidosis Etiology May be

Metabolic and Genetic Disorders Amyloidosis Etiology • May be primary (idiopathic), secondary to systemic disease, or familial • Formation of a fibrillar protein deposited in soft tissues and visceral organs with associated levels of dysfunction

Etiology • May be primary (idiopathic), secondary to systemic disease, or familial • Formation of a fibrillar protein deposited in soft tissues and visceral organs with associated levels of dysfunction

Clinical Presentation • The primary form may produce obvious tongue enlargement (macroglossia) and associated purpura, or nodular submucosal alterations. • The secondary form may be subtle; gingival tissues may contain deposits of amyloid.

Diagnosis • Appearance of tongue • Systemic complaints • Biopsy results: demonstration of amyloid deposits in tissues (tongue, gingiva)

Differential Diagnosis • Hyalinosis cutis et mucosae (lipoid proteinosis) • Leukemic infiltrate • Lymphangioma • Neurofibromatosis • Hemodialysis-related disorder

Treatment • Directed to underlying cause (secondary) • Localized amyloid tumors may be excised. • Generally symptom related (dialysis, digitalis, depending upon organ involvement)

Prognosis • • When renal impairment exists, transplantation may be necessary.

Cherubism Etiology • Autosomal-dominant, fibroblast/giant cell– containing condition • May be secondary to somatic mutation, mapping to chromosome 4 p 16. 3 • No associated metabolic or biochemical alterations noted • Possible linkage/association with Noonan’s syndrome

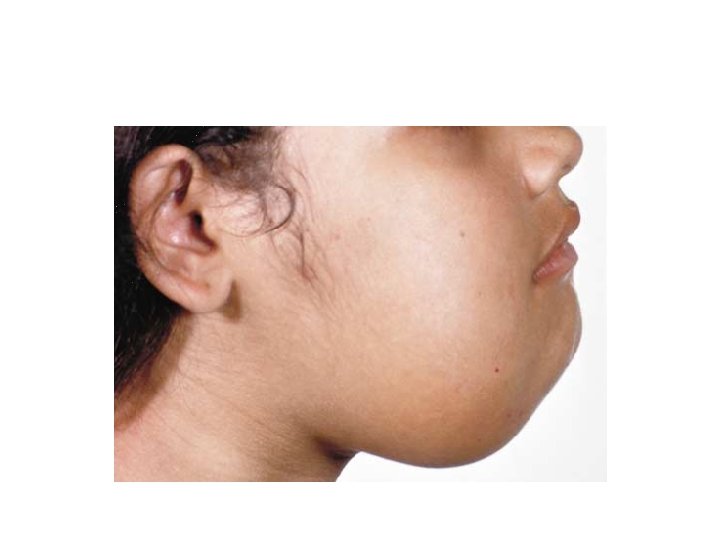

Clinical Presentation • Early signs in childhood • Bilateral, symmetric enlargement of mandible • Maxillary involvement less common and less prominent • Dental arch/occlusal discrepancies may be noted. • Unerupted teeth often noted • Facial features include lower-third fullness and scleral exposure at a forward resting gaze.

Radiographic Findings • Symmetric, multiloculated, expansile radiolucencies of mandibular body and ramus • Impacted/displaced teeth common • Thinned cortices with scalloped medullary margins • Older patients may exhibit maturation with bone fill in some areas but with preservation of expanded bony profile.

Diagnosis • Clinical appearance • Radiographic findings

Differential Diagnosis • • • Central giant cell granuloma (multiple) Fibrous dysplasia Langerhans cell disease (histiocytosis X) Hyperparathyroidism Multiple odontogenic keratocysts

Treatment • Variable, ranging from cosmetic recontouring to local curettage early in lesion development • Active surgical intervention should be deferred until after the pubertal growth spurt, if possible.

Prognosis • Stability usually noted by end of skeletal growth • Often regresses into adulthood, but variably so

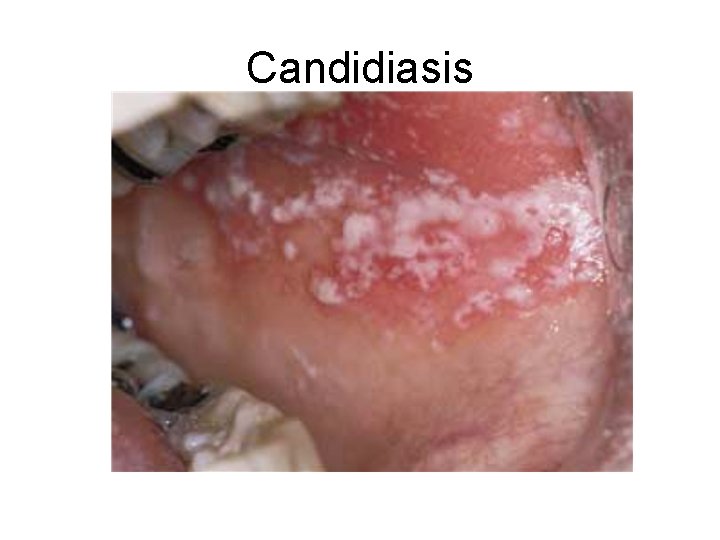

Candidiasis

Etiology • Infection with a fungal organism of the Candida species, usually Candida albicans • Associated with predisposing factors: most commonly, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, antibiotic use, or xerostomia (due to lack of protective effects of saliva)

Clinical Presentation • • • • Acute (thrush) • Pseudomembranous • Painful white plaques representing fungal colonies on inflamed mucosa • Erythematous (acute atrophic): painful red patches caused by acute Candida overgrowth and subsequent stripping of those colonies from mucosa • Chronic • Atrophic (erythematous): painful red patches; organism difficult to identify by culture, smear, and biopsy • “Denture-sore mouth”: a form of atrophic candidiasis associated with poorly fitting dentures; mucosa is red and painful on denture-bearing surface

Clinical Presentation • • • Median rhomboid glossitis: a form of hyperplastic candidiasis seen on midline dorsum of tongue anterior to circumvallate papillae • Perlèche: chronic Candida infection of labial commissures; often co-infected with Staphylococcus aureus • Hyperplastic/chronic hyperplastic: a form of hyperkeratosis in which Candida has been identified; usually buccal mucosa near commissures; cause and effect not yet proven • Syndrome associated: chronic candidiasis may be seen in association with endocrinopathies

Diagnosis • • Microscopic evaluation of lesion smears • • Potassium hydroxide preparation to demonstrate hyphae • • Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain • • Culture on proper medium (Sabouraud’s, corn meal, or • potato agar) • • Biopsy with PAS, Gomori’s methenamine silver (GMS), or • other fungal stain of microscopic sections

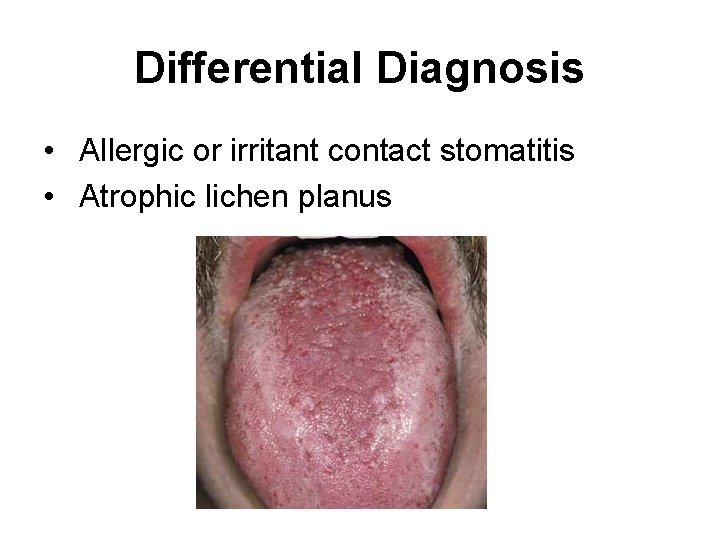

Differential Diagnosis • Allergic or irritant contact stomatitis • Atrophic lichen planus

Treatment • Topical or systemic antifungal agents • For immunocompromised patients: routine topical agents after control of infection is achieved, usually with systemic azole agents • See “Therapeutics” section • Correction of predisposing factor, if possible • Some cases of chronic candidiasis may require prolonged therapy (weeks to months).

Prognosis • Excellent in the immunocompetent host

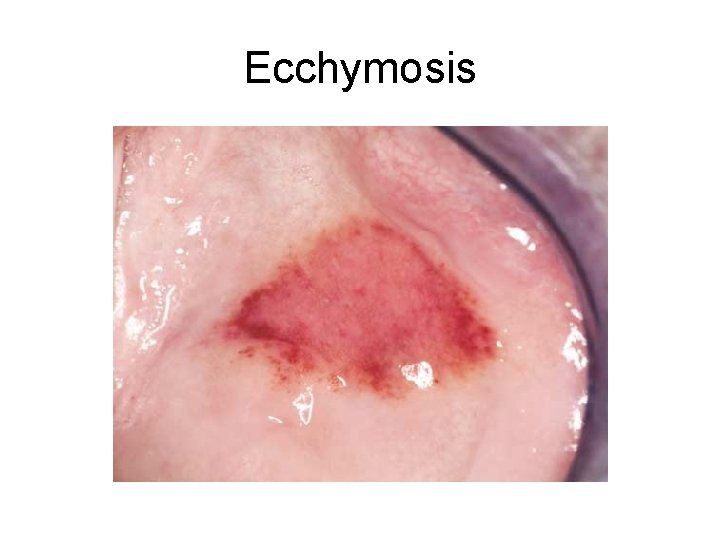

Ecchymosis

Etiology • Soft tissue hemorrhage • Blood dyscrasia with secondary thrombocytopenia, hemophilia • Vascular wall defects • Coagulopathy • Trauma

Clinical Presentation • Larger than pinpoint spots (ie, larger than petechiae) • Nonvesicular, macular surface • Lesions do not blanch with pressure • Red to reddish blue to brown color

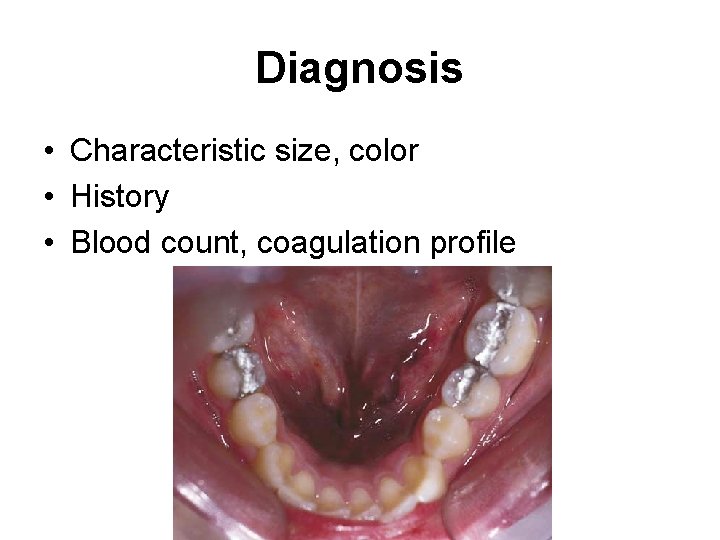

Diagnosis • Characteristic size, color • History • Blood count, coagulation profile

Differential Diagnosis • Hemophilia, Kaposi’s sarcoma, hemangioma, thrombocytopenia, von Willebrand’s disease, leukemia, trauma

Treatment • Identification of etiology, and corresponding treatment

Prognosis • Excellent

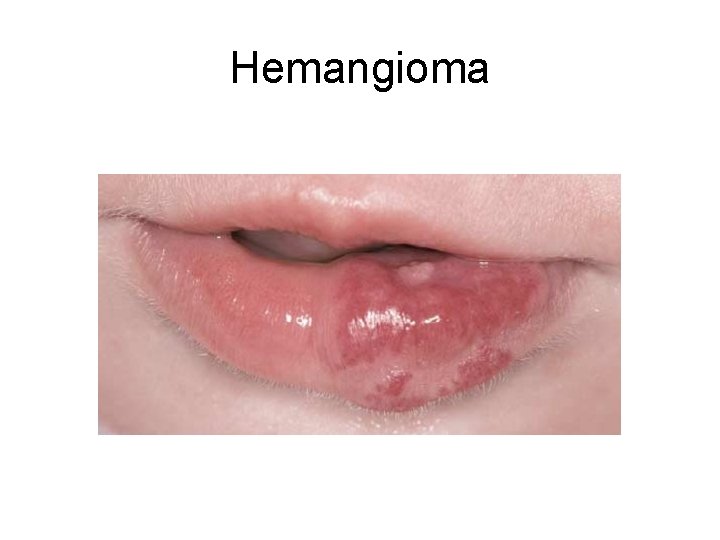

Hemangioma

Etiology • Benign developmental anomalies of blood vessels that may be subclassified as congenital hemangiomas and vascular malformations • “Congenital hemangioma” usually noted initially in infancy or childhood (hamartomatous proliferation) • Congenital hemangioma due to proliferation of endothelial cells • “Vascular malformations” due to abnormal morphogenesis of arterial and venous structures

Clinical Presentation • Congenital lesions usually arise around time of birth, grow rapidly, and usually involute over several years. • Malformations generally are persistent, grow with the child, and do not involute. • Color varies from red to blue depending on depth, degree of congestion, and caliber of vessels • Range in size from few millimeters to massive with disfigurement • Most common on lips, tongue, buccal mucosa • Usually asymptomatic • Sturge-Weber syndrome (trigeminal encephaloangiomatosis) includes cutaneous vascular malformations (port wine stains) along trigeminal nerve distribution, mental retardation, and seizures.

Diagnosis • Aspiration • Blanching under pressure (diascopy) • Imaging studies

Differential Diagnosis • • Purpura Telangiectasia Kaposi’s sarcoma Other vascular neoplasms

Treatment • Observation • Congenital hemangiomas typically involute, whereas vascular malformations persist. • Surgery (scalpel, cryosurgery, laser [argon, copper])— congenital hemangiomas usually are circumscribed and more easily removed than are vascular malformations, which are poorly defined. (Vascular malformations are associated with excessive bleeding and recurrence. ) • Sclerotherapy • Microembolization followed by resection for large malformations or if bleeding is problematic

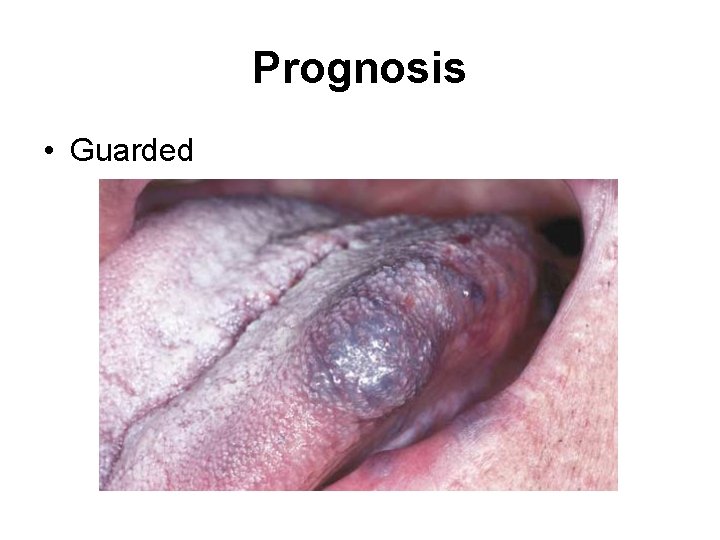

Prognosis • Guarded

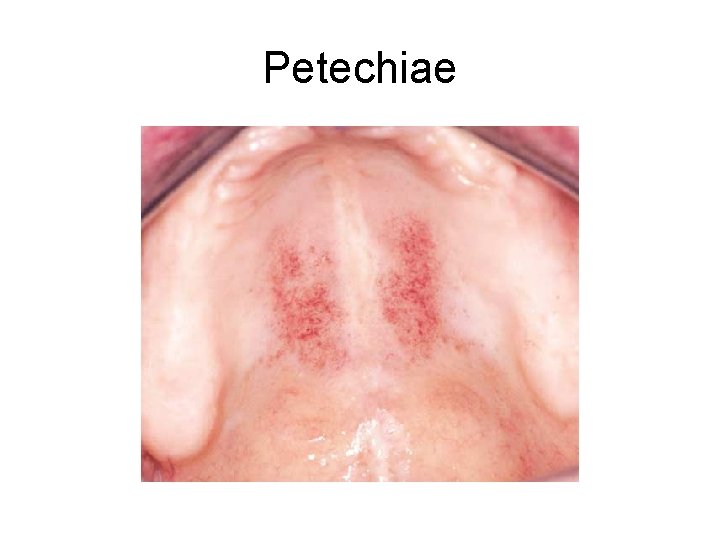

Petechiae

![Etiology • Viral infection (Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]mononucleosis; measles), rickettsial infection • Thrombocytopenia, leukemia • Etiology • Viral infection (Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]mononucleosis; measles), rickettsial infection • Thrombocytopenia, leukemia •](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/c274cb709c7d17062a7278964d3e7d51/image-41.jpg)

Etiology • Viral infection (Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]mononucleosis; measles), rickettsial infection • Thrombocytopenia, leukemia • Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) • Trauma: prolonged coughing, frequent vomiting, giving birth, fellatio, violent Valsalva maneuvers

Clinical Presentation • Pinpoint hemorrhage into mucosa/submucosa • Asymptomatic • Usually involves the soft palate • No blanching on pressure (diascopy)

Diagnosis • Clinical features • History, determination of underlying cause

Treatment • None; observation only Prognosis • Variable, depending upon etiology

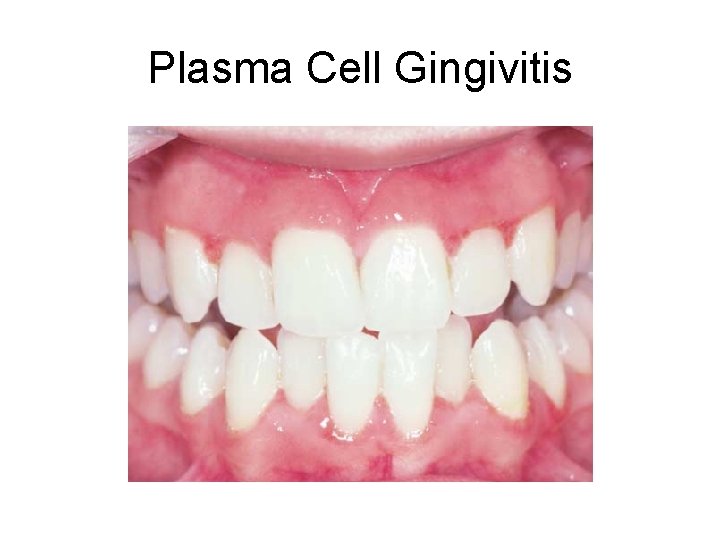

Plasma Cell Gingivitis

Etiology • Usually represents a hypersensitivity phenomenon to an agent such as the following: • Cinnamon/cinnamon flavoring • Candy flavors • Toothpaste/mouthwash • Plaque antigens

Clinical Presentation • Reddened, velvety gingival surface • Surface epithelium becomes nonkeratinized. • Limited to attached gingiva

Diagnosis • Response to elimination of possible etiologic agents • Biopsy results show plasma cell infiltration within the submucosa and lamina propria beneath an acanthotic epithelium. • Patch testing

Differential Diagnosis • • • Lupus erythematosus Wegener’s granulomatosis Chronic candidiasis Lichen planus Mucous membrane pemphigoid

Treatment • Elimination of causative factor Prognosis • Reversal with removal of causative agent

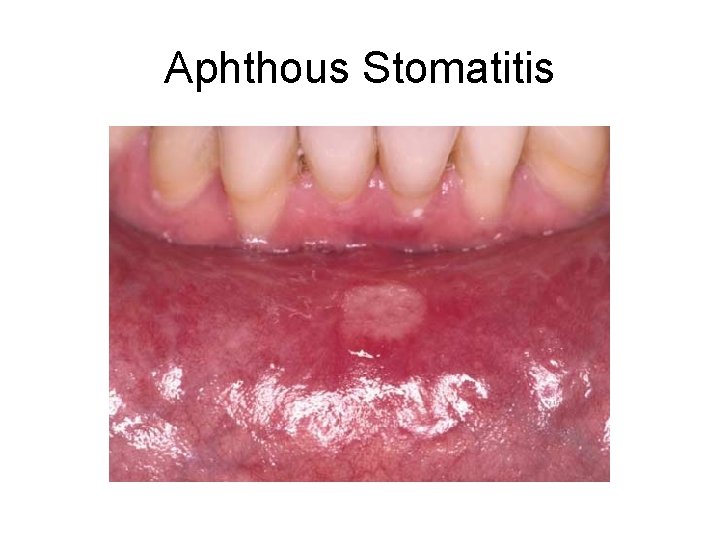

Aphthous Stomatitis

Etiology • • • Unknown—probably represents a focal immunodysfunction; no viral or other infectious agent identified • Triggers vary from case to case (eg, increased stress/anxiety, hormonal changes, dietary factors, trauma) • Alterations in barrier permeability may be a factor, as occur with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), bone marrow suppression, neutropenia, gluten sensitivity, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, food allergy, Behçet’s disease, and dietary deficiencies (iron, folate, vitamin B 12, zinc).

Clinical Presentation • • Recurrent, self-limiting, painful ulcers • • Usually restricted to nonkeratinized oral and pharyngeal • mucosa (not hard palate or attached gingiva) • • Well-demarcated ulcers with yellow fibrinous base and • erythematous halo • • Three clinical forms: minor ulcers, major ulcers, herpetiform • lesions

Minor variant (most common subtype) • • • Occasional Single but more often multiple Less than 1 cm in diameter Oval to round shape Healing within 7 to 14 days

Major variant (Sutton’s ulcers) • • 1 cm or greater in diameter Single or less commonly several Deep To ragged edges with elevated edematous margins • May persist for several weeks to months • Often heal with scarring

Herpetiform variant (least common variant) • Grouped superficial ulcers 1 to 2 mm in diameter; crops of 10 to 100 lesions • In nonkeratinized and keratinized tissues • Healing within 7 to 14 days • No etiologic role for herpes simplex virus

Diagnosis • Usually has diagnostic clinical appearance of focal, welldefined ulcers involving nonkeratinized mucosa • History helpful; a recurrent process • Positive family history

Differential Diagnosis • Traumatic ulcer • Chancre • Recurrent intraoral herpes simplex stomatitis • Cyclic neutropenia

Treatment • Symptomatic therapy may be adequate. • Systemic causative factors, if present, should be addressed. • Tetracycline-based oral rinses may be helpful. • Corticosteroid therapy is the most rational approach and is a consistently effective treatment. • Topical corticosteroids as gels, creams, or ointment 4 to 6 times/d to early lesions • Intralesional corticosteroid injections • Short-duration systemic corticosteroids (low to moderate doses)

Prognosis • • Simple aphthosis Excellent Cannot be cured Good control with corticosteroids is usually possible. Typically, severity decreases as patient ages. Complex aphthosis Needs medical evaluation for intercurrent disease Chronic problem

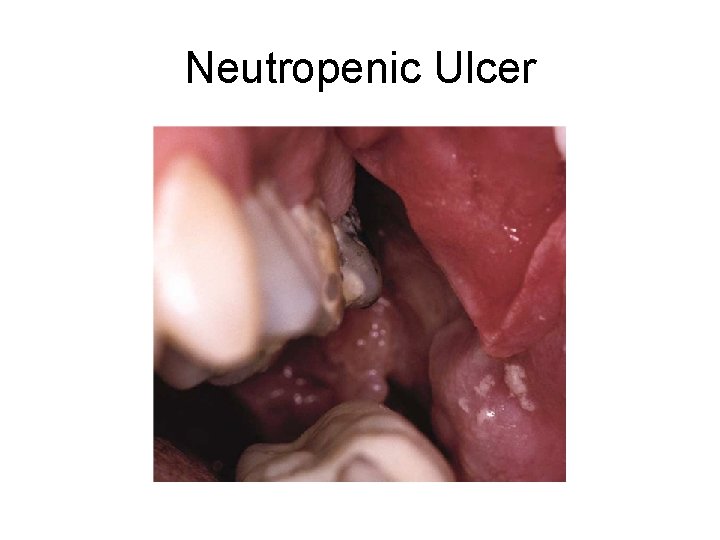

Neutropenic Ulcer

Etiology • Idiopathic or iatrogenic neutropenia • Usually noted when neutrophil count falls below 1, 500/mm 3

Clinical Presentation • Sharply defined ulcer(s), often with minimal peripheral erythema • Ulcer base covered by fibrinous exudate • Wide variation in size of ulcers

Diagnosis • Clinical appearance correlated with results of peripheral blood count

Differential Diagnosis • • Major aphthous ulcer Traumatic ulcer Necrotizing sialometaplasia Squamous cell carcinoma

Treatment • Identification and management of underlying neutropenia • Supportive therapy Prognosis • Relative to ability to manage underlying neutropenia

- Slides: 66