Memory Management 1 Basic OS Organization Operating System

Memory Management 1

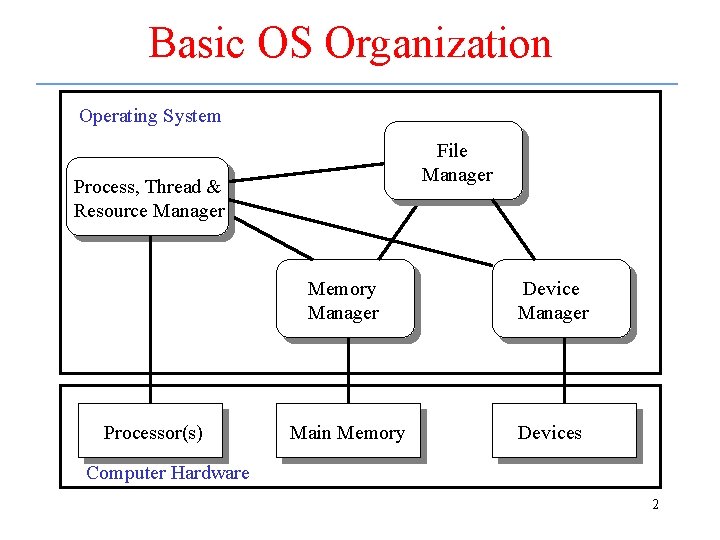

Basic OS Organization Operating System File Manager Process, Thread & Resource Manager Processor(s) Memory Manager Device Manager Main Memory Devices Computer Hardware 2

Storage Hierarchies in the Office Le Us ss F ed re In que fo n rm tly ati on tly en on qu ati re rm e F fo or In M ed Us 3

The Basic Memory Hierarchy tly en on qu ati re rm e F fo or In M ed Us Le Us ss F ed re CPU Registers In que fo n rm tly ati Primary Memory on (Executable Memory) e. g. RAM Secondary Memory e. g. Disk or Tape von Neumann architecture 4

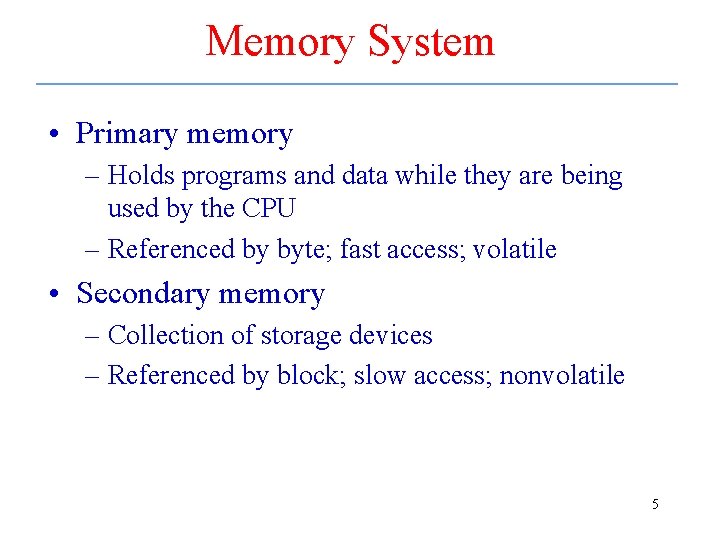

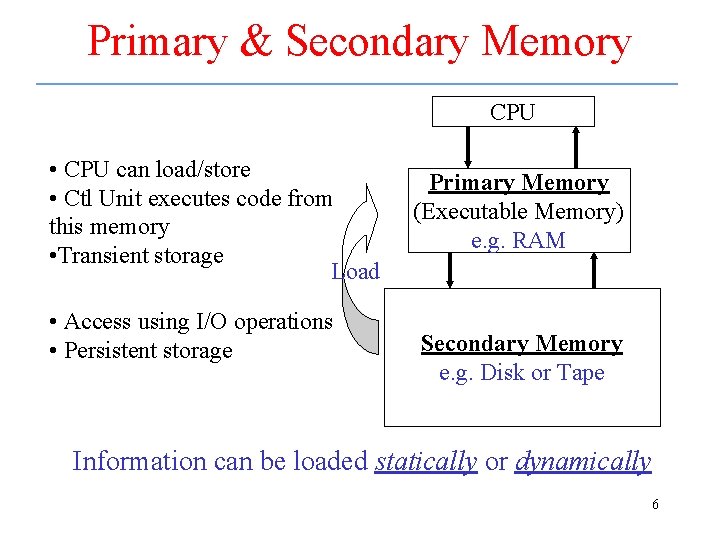

Memory System • Primary memory – Holds programs and data while they are being used by the CPU – Referenced by byte; fast access; volatile • Secondary memory – Collection of storage devices – Referenced by block; slow access; nonvolatile 5

Primary & Secondary Memory CPU • CPU can load/store • Ctl Unit executes code from this memory • Transient storage Load • Access using I/O operations • Persistent storage Primary Memory (Executable Memory) e. g. RAM Secondary Memory e. g. Disk or Tape Information can be loaded statically or dynamically 6

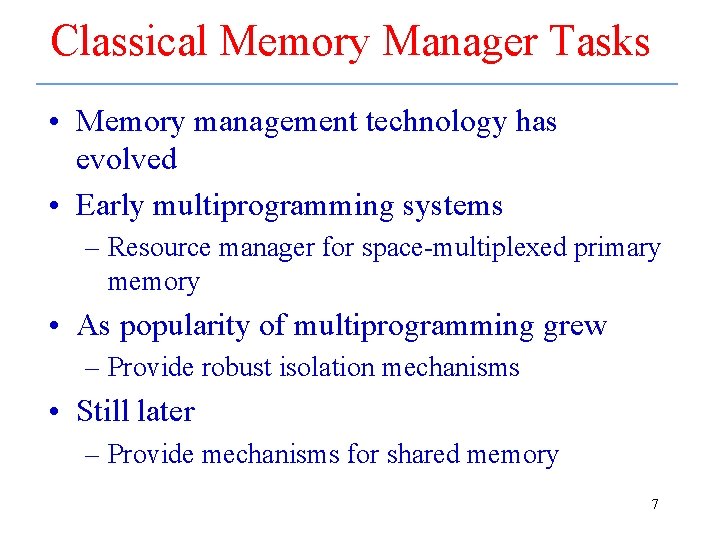

Classical Memory Manager Tasks • Memory management technology has evolved • Early multiprogramming systems – Resource manager for space-multiplexed primary memory • As popularity of multiprogramming grew – Provide robust isolation mechanisms • Still later – Provide mechanisms for shared memory 7

L 1 Cache Memory L 2 Cache Memory “Main” Memory Optical Memory Sequentially Accessed Memory Faster access/higher cost Primary (Executable) CPU Registers Rotating Magnetic Memory Secondary Larger storage/lower cost Memory Hierarchies – Dynamic Loading 8

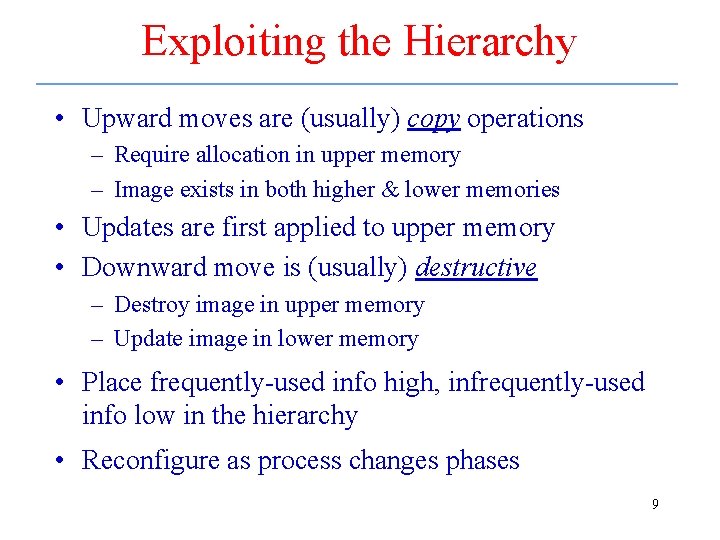

Exploiting the Hierarchy • Upward moves are (usually) copy operations – Require allocation in upper memory – Image exists in both higher & lower memories • Updates are first applied to upper memory • Downward move is (usually) destructive – Destroy image in upper memory – Update image in lower memory • Place frequently-used info high, infrequently-used info low in the hierarchy • Reconfigure as process changes phases 9

Contemporary Memory Manager • Performs the classic functions required to manage primary memory – Attempts to efficiently use primary memory – Keep programs/data in primary memory only while they are being used by CPU – Store/restore data in secondary memory soon after it has been used or created • Exploits storage hierarchies – Virtual memory manager 10

Requirements on Memory Designs • The primary memory access time must be as small as possible • The perceived primary memory must be as large as possible • The memory system must be cost effective 11

Functions of Memory Manager • Allocate primary memory space to processes • Map the process address space into the allocated portion of the primary memory • Minimize access times using a cost-effective amount of primary memory • May use static or dynamic techniques 12

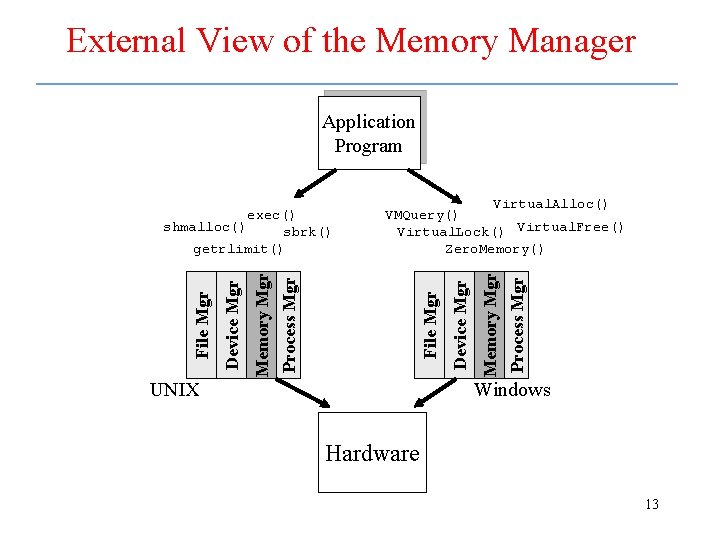

External View of the Memory Manager Application Program Memory Mgr Process Mgr File Mgr UNIX Device Mgr Virtual. Alloc() VMQuery() Virtual. Lock() Virtual. Free() Zero. Memory() Memory Mgr Process Mgr Device Mgr File Mgr exec() shmalloc() sbrk() getrlimit() Windows Hardware 13

Memory Manager • Only a small number of interface functions provided – usually calls to: – Request/release primary memory space – Load programs – Share blocks of memory • Provides following – Memory abstraction – Allocation/deallocation of memory – Memory isolation – Memory sharing 14

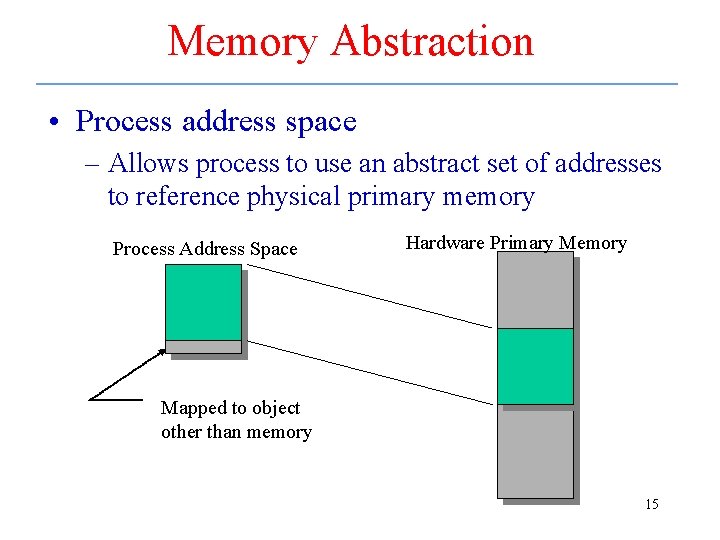

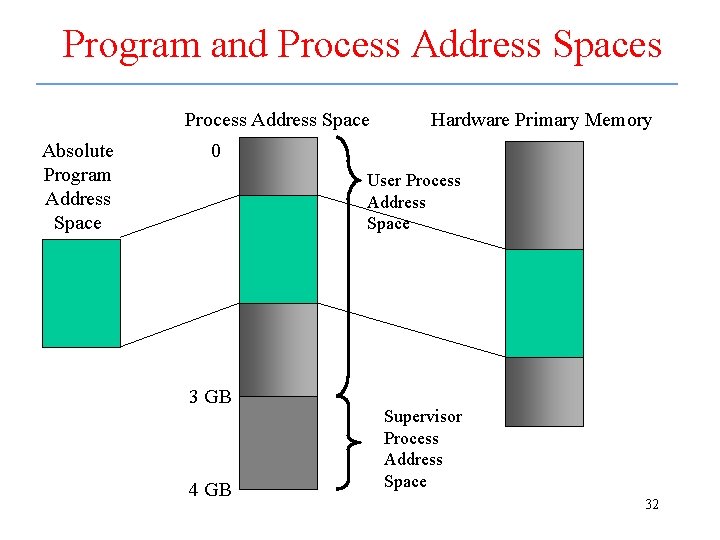

Memory Abstraction • Process address space – Allows process to use an abstract set of addresses to reference physical primary memory Process Address Space Hardware Primary Memory Mapped to object other than memory 15

Address Space • Program must be brought into memory and placed within a process for it to be executed – A program is a file on disk – CPU reads instructions from main memory and reads/writes data to main memory • Determined by the computer architecture – Address binding of instructions and data to memory addresses 16

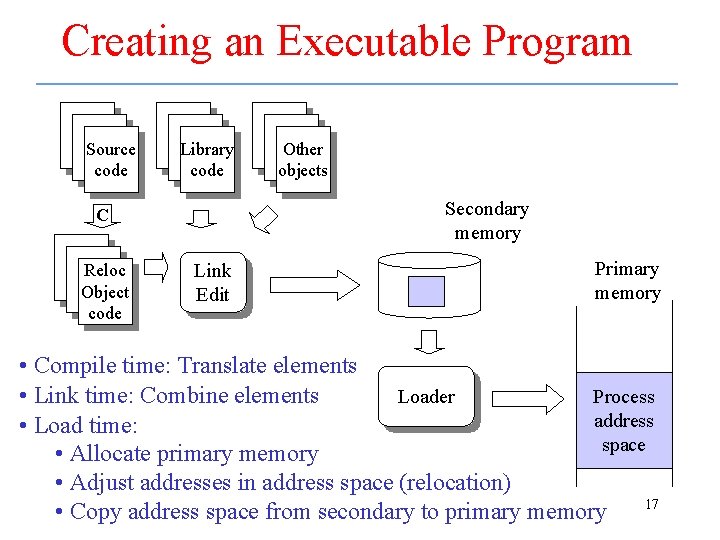

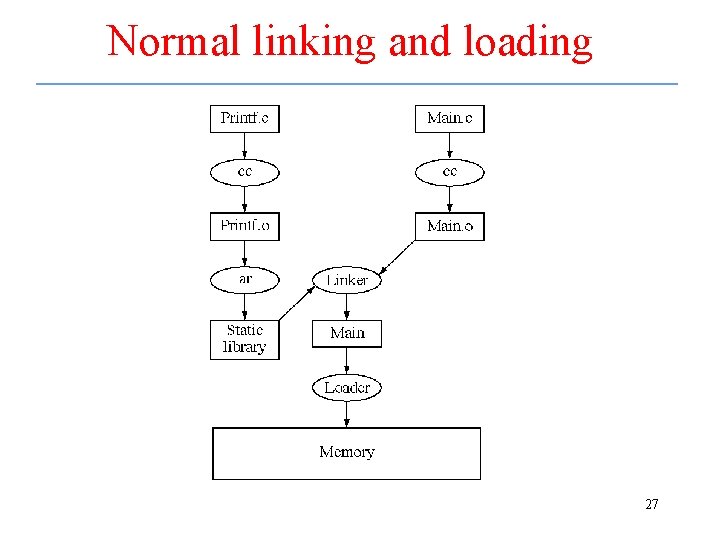

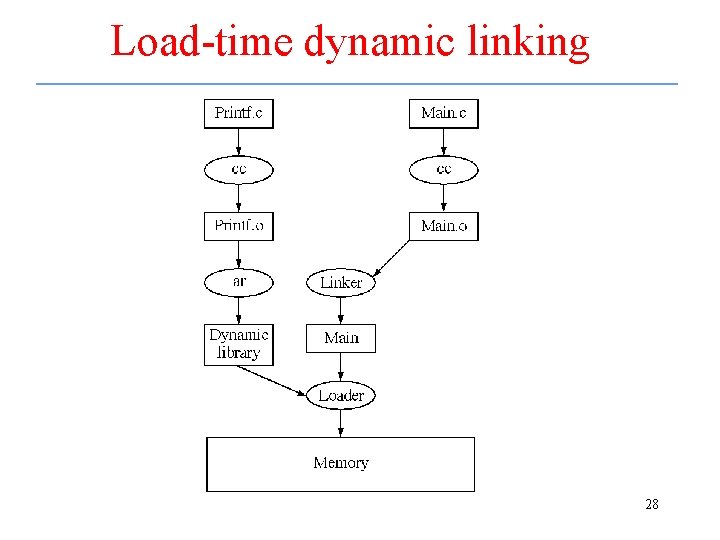

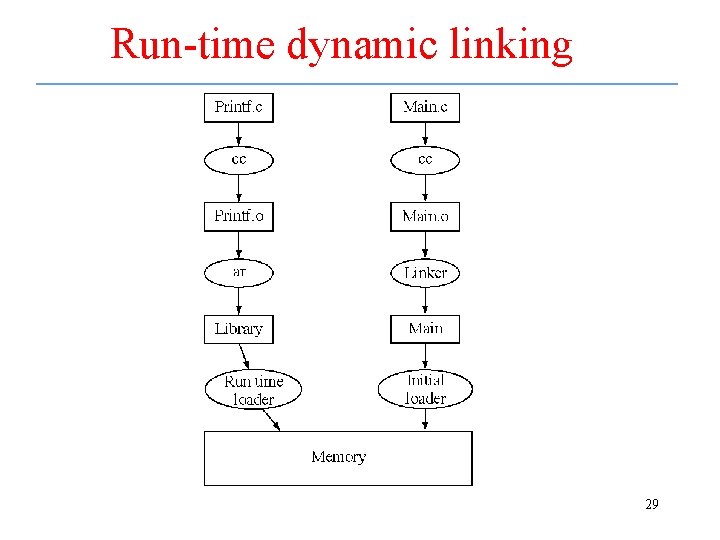

Creating an Executable Program Source code Library code Secondary memory C Reloc Object code Other objects Link Edit Primary memory • Compile time: Translate elements • Link time: Combine elements Loader Process address • Load time: space • Allocate primary memory • Adjust addresses in address space (relocation) 17 • Copy address space from secondary to primary memory

Bindings • Compiler – Binds static variables to storage locations relative to start of data segment – Binds automatic variables to storage locations relative to bottom of stack • Linker – Combines data segments and adjusts bindings accordingly – Same for stack 18

Bindings – cont. • Loader – Binds logical addresses used by program with physical memory locations (address binding) • This type of binding is called static address binding • The last stage of address binding can be deferred to runtime dynamic address binding 19

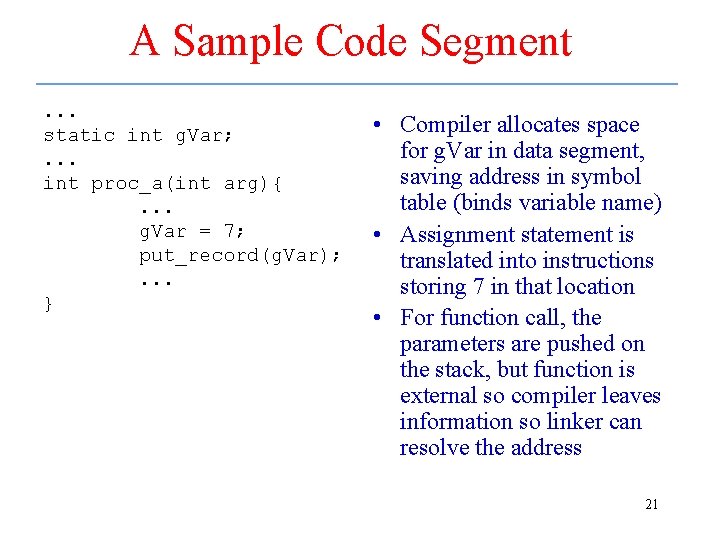

A Sample Code Segment. . . static int g. Var; . . . int proc_a(int arg){. . . g. Var = 7; put_record(g. Var); . . . } 20

A Sample Code Segment. . . static int g. Var; . . . int proc_a(int arg){. . . g. Var = 7; put_record(g. Var); . . . } • Compiler allocates space for g. Var in data segment, saving address in symbol table (binds variable name) • Assignment statement is translated into instructions storing 7 in that location • For function call, the parameters are pushed on the stack, but function is external so compiler leaves information so linker can resolve the address 21

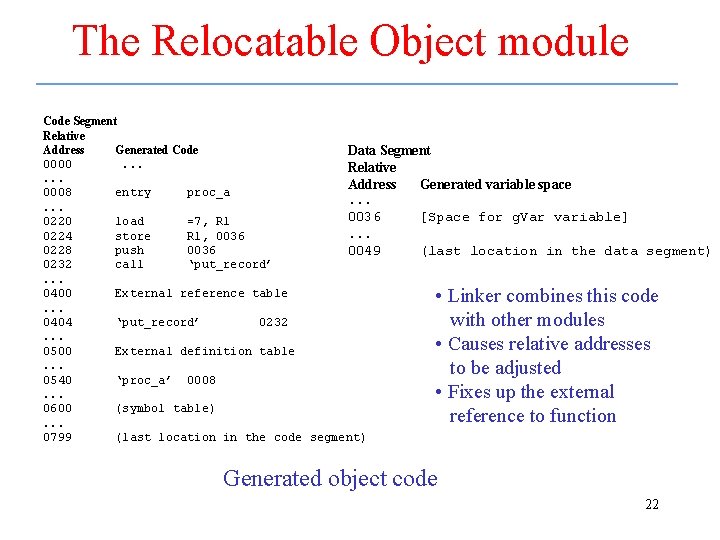

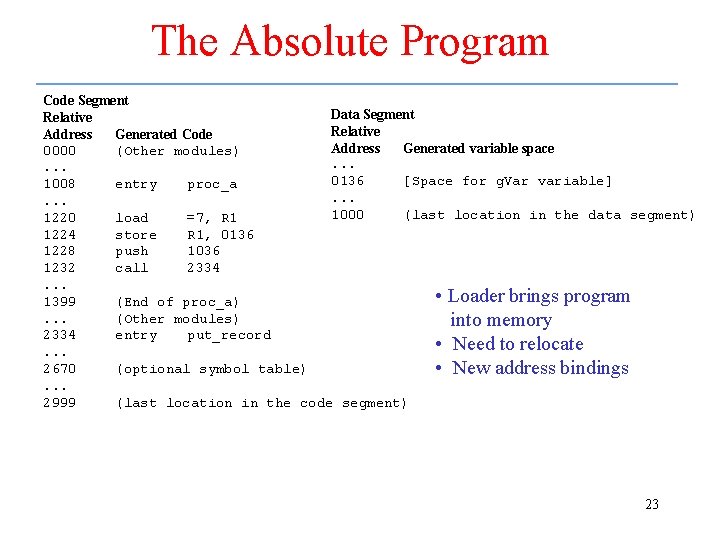

The Relocatable Object module Code Segment Relative Address Generated Code Data Segment 0000. . . Relative. . . Address Generated variable space 0008 entry proc_a. . . 0036 [Space for g. Var variable] 0220 load =7, R 1. . . 0224 store R 1, 0036 0228 push 0036 0049 (last location in the data segment) 0232 call ‘put_record’. . . 0400 External reference table. . . 0404 ‘put_record’ 0232. . . 0500 External definition table. . . 0540 ‘proc_a’ 0008. . . 0600 (symbol table). . . 0799 (last location in the code segment) • Linker combines this code with other modules • Causes relative addresses to be adjusted • Fixes up the external reference to function Generated object code 22

The Absolute Program Code Segment Data Segment Relative Address Generated Code Address Generated variable space 0000 (Other modules). . . 0136 [Space for g. Var variable] 1008 entry proc_a. . . 1000 (last location in the data segment) 1220 load =7, R 1 1224 store R 1, 0136 1228 push 1036 1232 call 2334. . . • Loader brings program 1399 (End of proc_a). . . (Other modules) into memory 2334 entry put_record • Need to relocate. . . 2670 (optional symbol table) • New address bindings. . . 2999 (last location in the code segment) 23

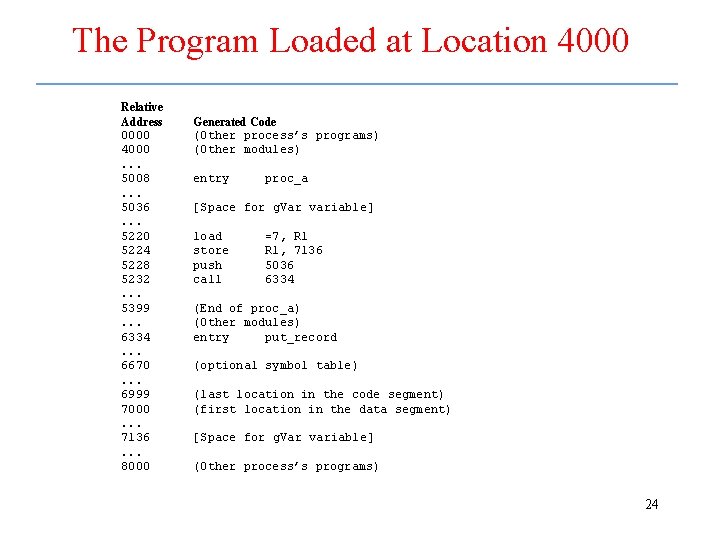

The Program Loaded at Location 4000 Relative Address 0000 4000. . . 5008. . . 5036. . . 5220 5224 5228 5232. . . 5399. . . 6334. . . 6670. . . 6999 7000. . . 7136. . . 8000 Generated Code (Other process’s programs) (Other modules) entry proc_a [Space for g. Var variable] load store push call =7, R 1, 7136 5036 6334 (End of proc_a) (Other modules) entry put_record (optional symbol table) (last location in the code segment) (first location in the data segment) [Space for g. Var variable] (Other process’s programs) 24

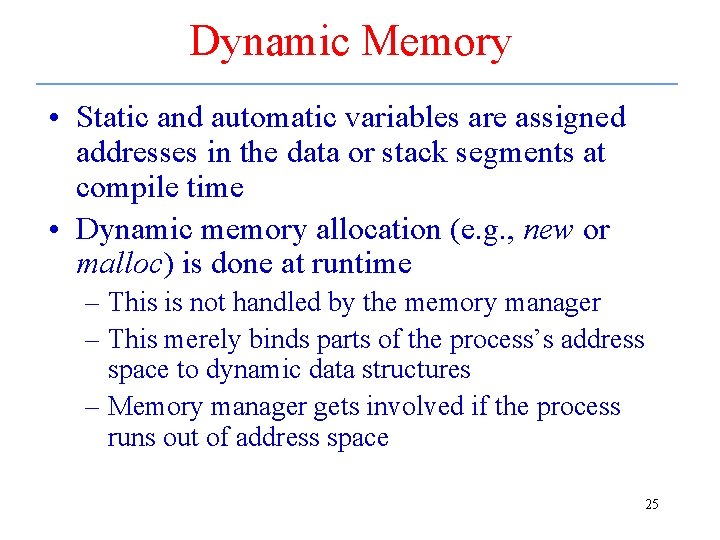

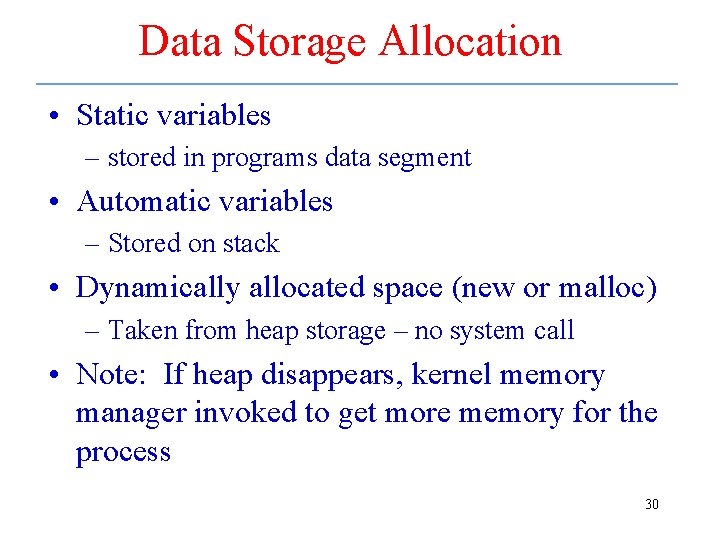

Dynamic Memory • Static and automatic variables are assigned addresses in the data or stack segments at compile time • Dynamic memory allocation (e. g. , new or malloc) is done at runtime – This is not handled by the memory manager – This merely binds parts of the process’s address space to dynamic data structures – Memory manager gets involved if the process runs out of address space 25

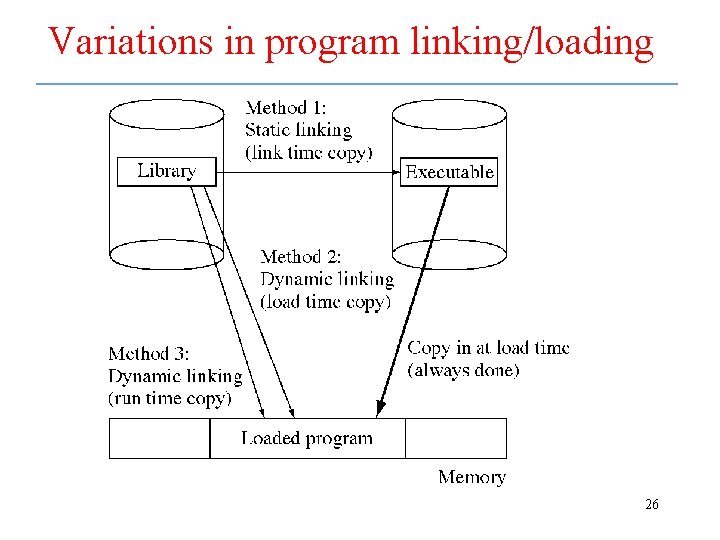

Variations in program linking/loading 26

Normal linking and loading 27

Load-time dynamic linking 28

Run-time dynamic linking 29

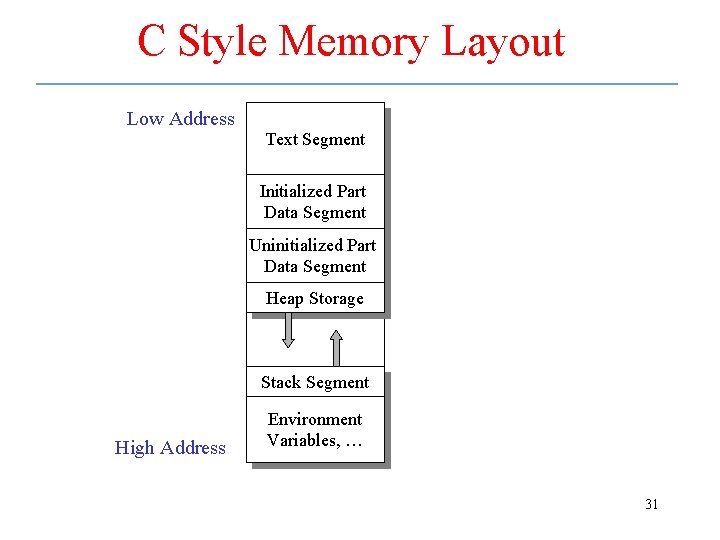

Data Storage Allocation • Static variables – stored in programs data segment • Automatic variables – Stored on stack • Dynamically allocated space (new or malloc) – Taken from heap storage – no system call • Note: If heap disappears, kernel memory manager invoked to get more memory for the process 30

C Style Memory Layout Low Address Text Segment Initialized Part Data Segment Uninitialized Part Data Segment Heap Storage Stack Segment High Address Environment Variables, … 31

Program and Process Address Spaces Process Address Space Absolute Program Address Space Hardware Primary Memory 0 User Process Address Space 3 GB 4 GB Supervisor Process Address Space 32

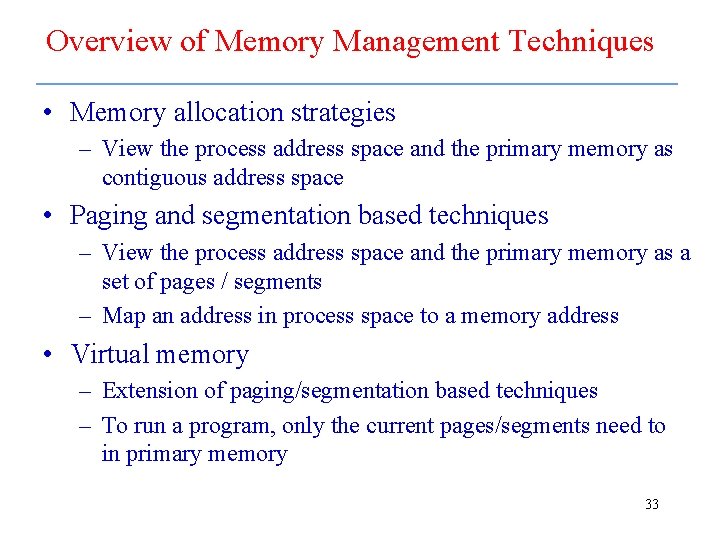

Overview of Memory Management Techniques • Memory allocation strategies – View the process address space and the primary memory as contiguous address space • Paging and segmentation based techniques – View the process address space and the primary memory as a set of pages / segments – Map an address in process space to a memory address • Virtual memory – Extension of paging/segmentation based techniques – To run a program, only the current pages/segments need to in primary memory 33

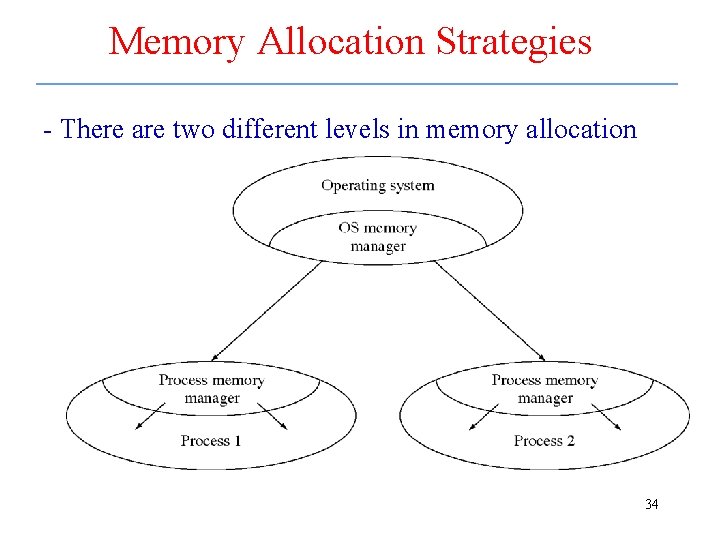

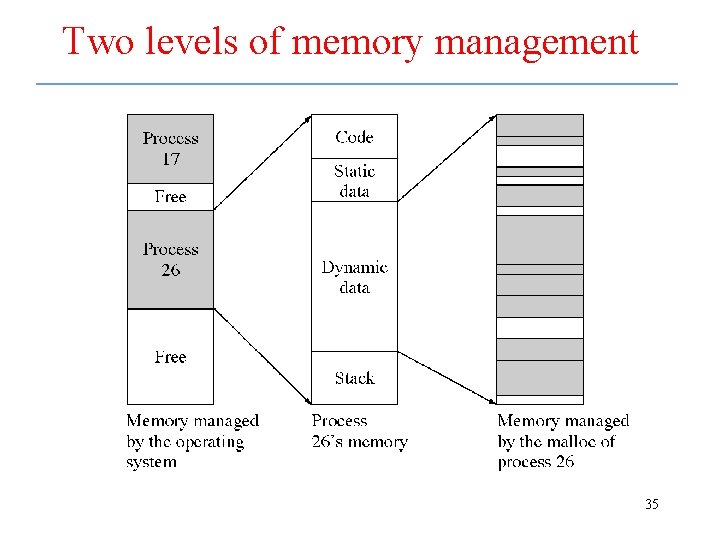

Memory Allocation Strategies - There are two different levels in memory allocation 34

Two levels of memory management 35

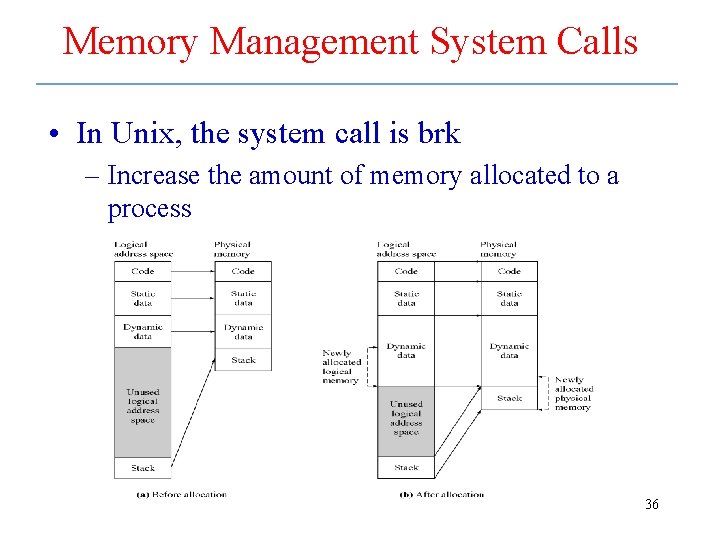

Memory Management System Calls • In Unix, the system call is brk – Increase the amount of memory allocated to a process 36

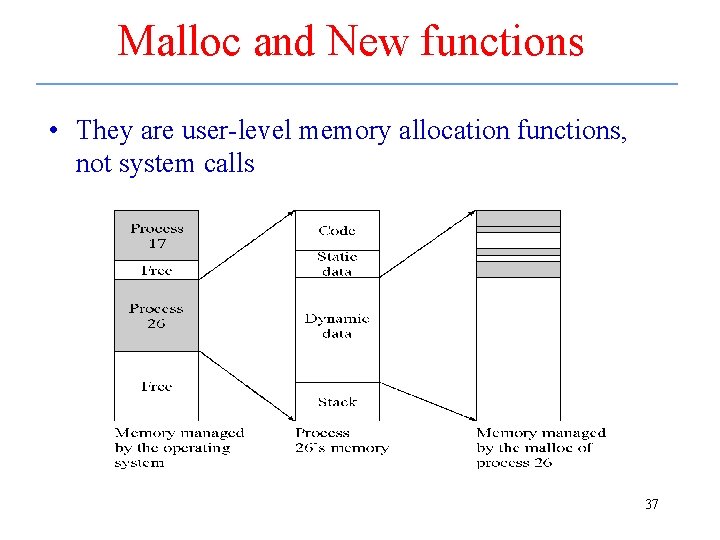

Malloc and New functions • They are user-level memory allocation functions, not system calls 37

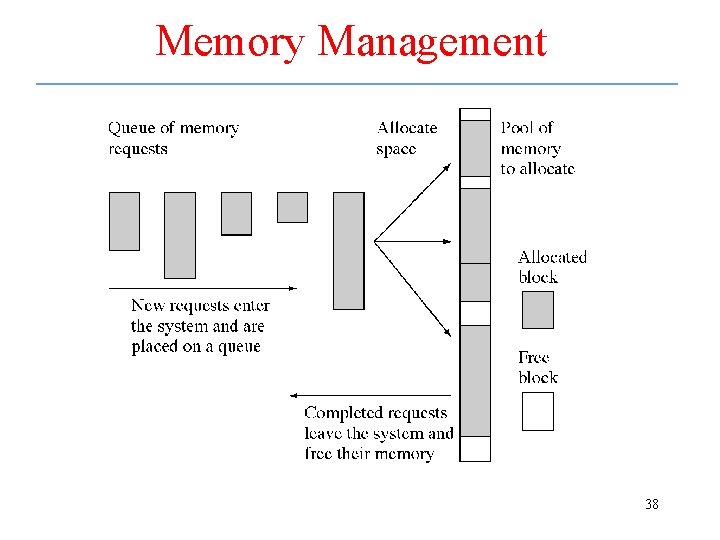

Memory Management 38

Issues in a memory allocation algorithm • Memory layout / organization – how to divide the memory into blocks for allocation? • Fixed partition method: divide the memory once before any bytes are allocated. • Variable partition method: divide it up as you are allocating the memory. • Memory allocation – select which piece of memory to allocate to a request • Memory organization and memory allocation are close related • It is a very general problem – Variations of this problem occurs in many places. • For examples: disk space management 39

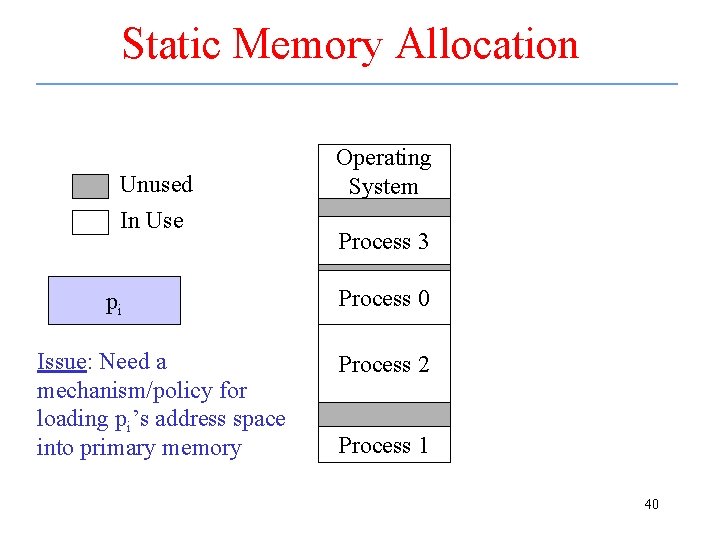

Static Memory Allocation Unused In Use pi Issue: Need a mechanism/policy for loading pi’s address space into primary memory Operating System Process 3 Process 0 Process 2 Process 1 40

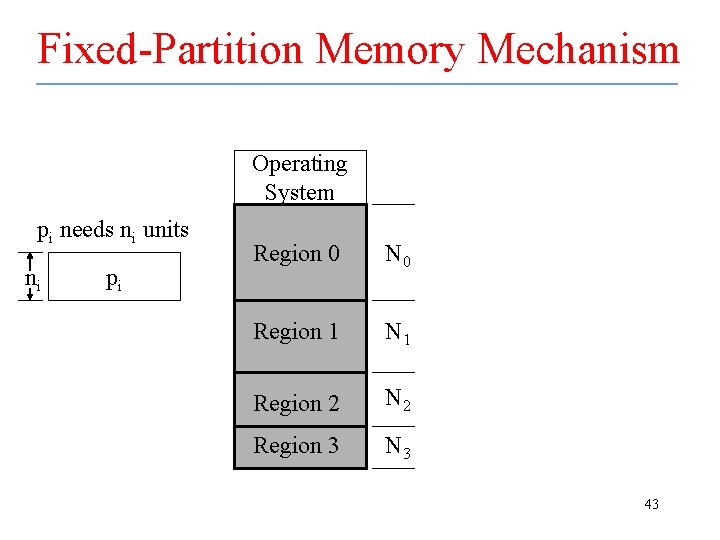

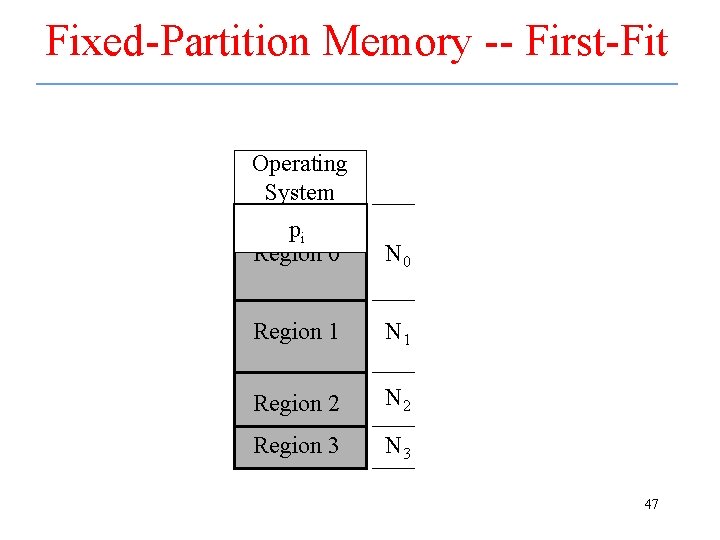

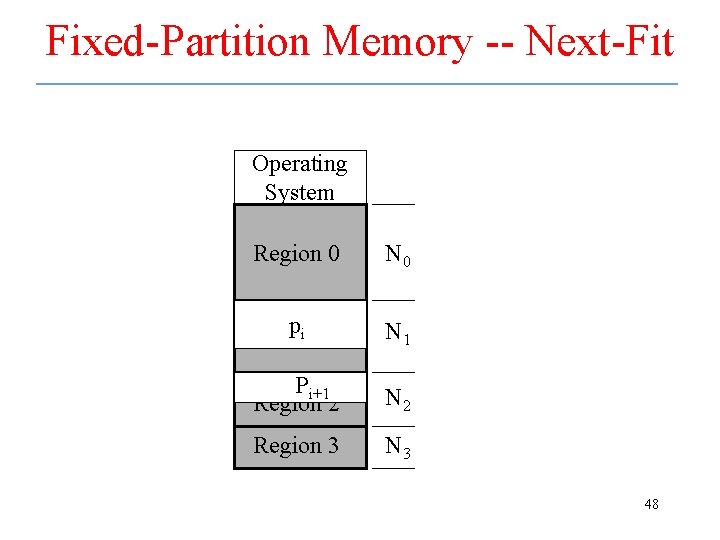

Fixed-Partition Memory allocation • Statically divide the primary memory into fixed size regions – Regions can have different sizes or same sizes • A process / request can be allocated to any region that is large enough 41

Fixed-Partition Memory allocation – cont. • Advantages – easy to implement. – Good when the sizes for memory requests are known. • Disadvantage: – cannot handle variable-size requests effectively. – Might need to use a large block to satisfy a request for small size. – Internal fragmentation – The difference between the request and the allocated region size; Space allocated to a process but is not used • It can be significant if the requests vary in size considerably 42

Fixed-Partition Memory Mechanism Operating System pi needs ni units ni pi Region 0 N 0 Region 1 N 1 Region 2 N 2 Region 3 N 3 43

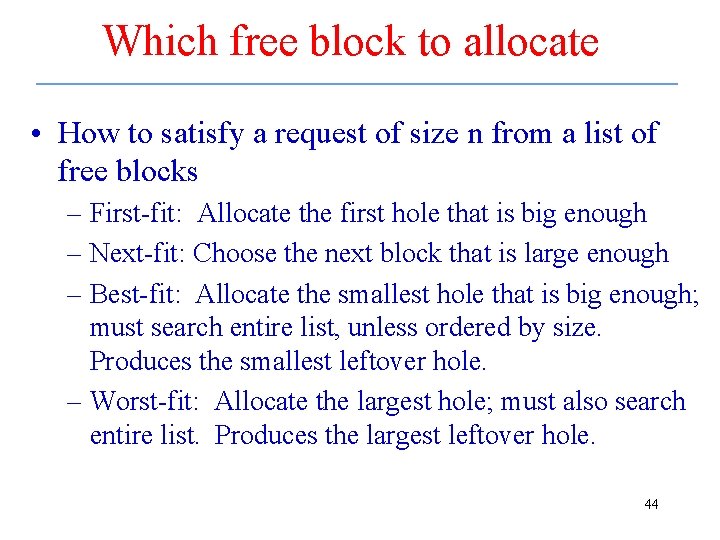

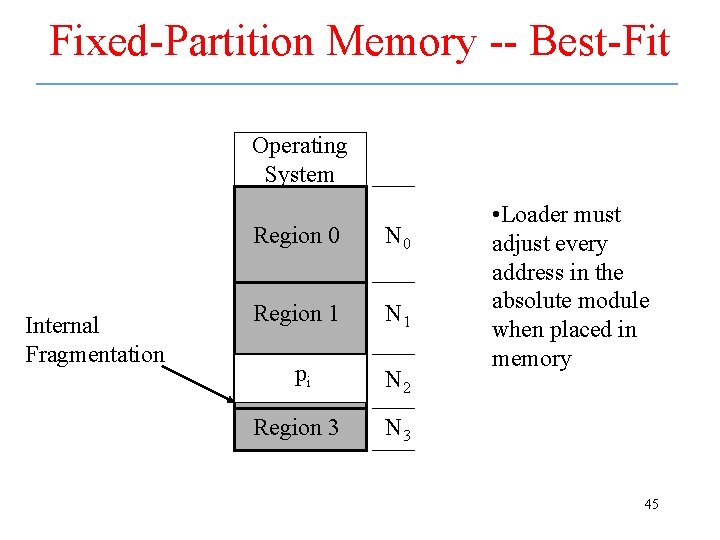

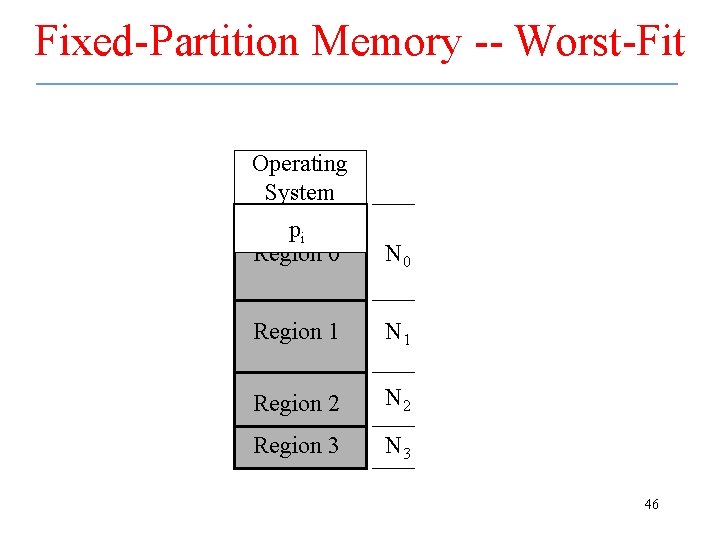

Which free block to allocate • How to satisfy a request of size n from a list of free blocks – First-fit: Allocate the first hole that is big enough – Next-fit: Choose the next block that is large enough – Best-fit: Allocate the smallest hole that is big enough; must search entire list, unless ordered by size. Produces the smallest leftover hole. – Worst-fit: Allocate the largest hole; must also search entire list. Produces the largest leftover hole. 44

Fixed-Partition Memory -- Best-Fit Operating System Internal Fragmentation Region 0 N 0 Region 1 N 1 pi 2 Region N 2 Region 3 N 3 • Loader must adjust every address in the absolute module when placed in memory 45

Fixed-Partition Memory -- Worst-Fit Operating System pi Region 0 N 0 Region 1 N 1 Region 2 N 2 Region 3 N 3 46

Fixed-Partition Memory -- First-Fit Operating System pi Region 0 N 0 Region 1 N 1 Region 2 N 2 Region 3 N 3 47

Fixed-Partition Memory -- Next-Fit Operating System Region 0 N 0 pi 1 Region N 1 Pi+1 Region 2 N 2 Region 3 N 3 48

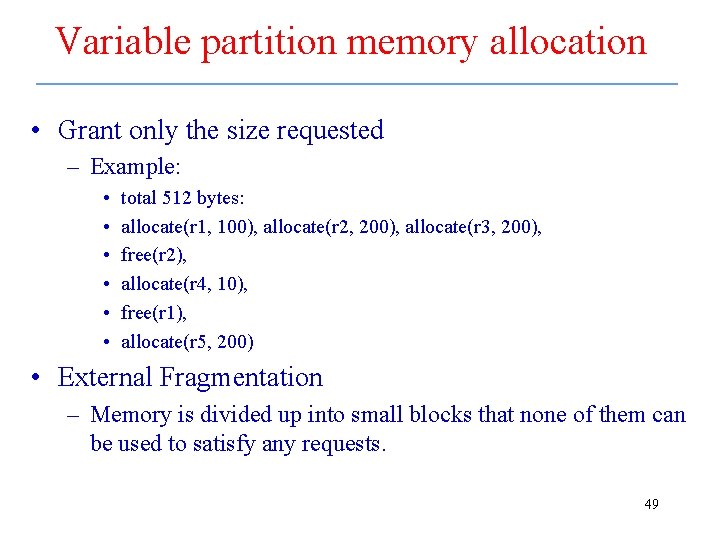

Variable partition memory allocation • Grant only the size requested – Example: • • • total 512 bytes: allocate(r 1, 100), allocate(r 2, 200), allocate(r 3, 200), free(r 2), allocate(r 4, 10), free(r 1), allocate(r 5, 200) • External Fragmentation – Memory is divided up into small blocks that none of them can be used to satisfy any requests. 49

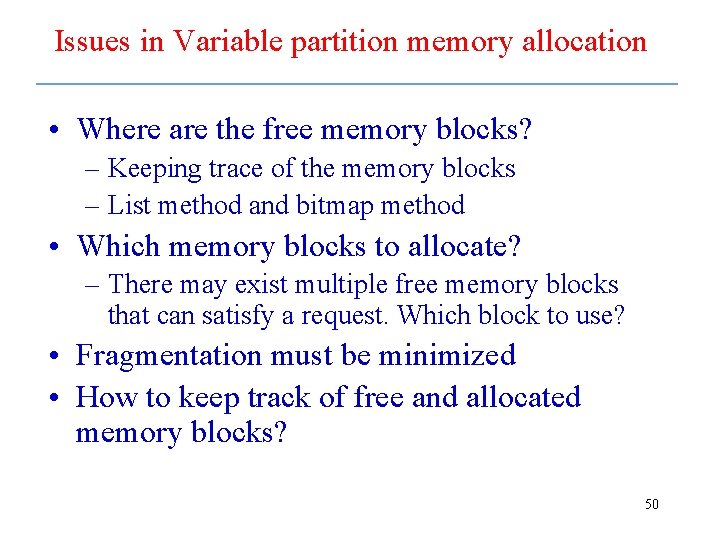

Issues in Variable partition memory allocation • Where are the free memory blocks? – Keeping trace of the memory blocks – List method and bitmap method • Which memory blocks to allocate? – There may exist multiple free memory blocks that can satisfy a request. Which block to use? • Fragmentation must be minimized • How to keep track of free and allocated memory blocks? 50

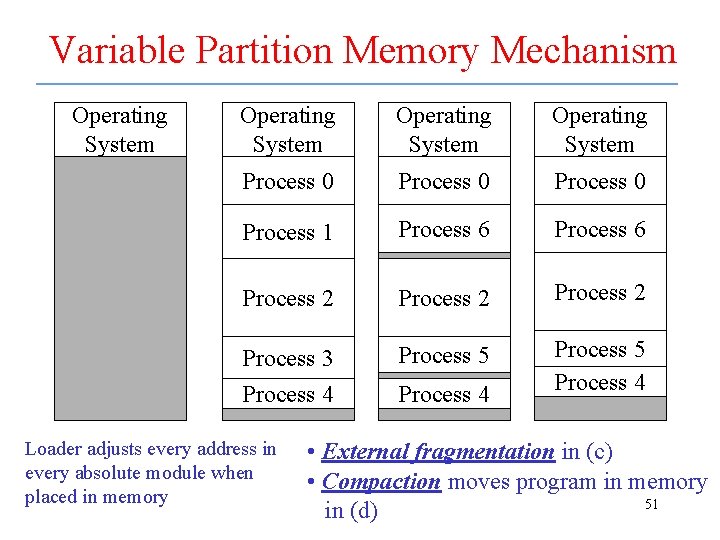

Variable Partition Memory Mechanism Operating System Process 0 Process 1 Process 6 Process 2 Process 3 Process 4 Process 5 Process 4 Loader adjusts every address in every absolute module when placed in memory Process 4 • External fragmentation in (c) • Compaction moves program in memory 51 in (d)

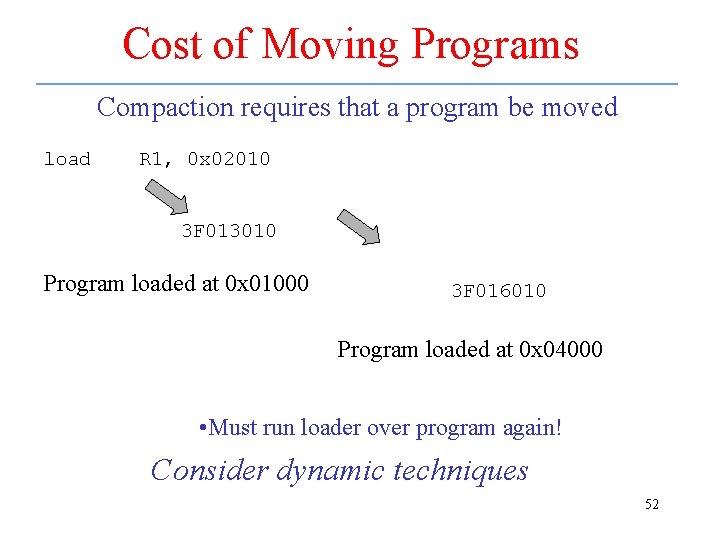

Cost of Moving Programs Compaction requires that a program be moved load R 1, 0 x 02010 3 F 013010 Program loaded at 0 x 01000 3 F 016010 Program loaded at 0 x 04000 • Must run loader over program again! Consider dynamic techniques 52

Dynamic Memory Allocation • Could use dynamically allocated memory • Process wants to change the size of its address space – Smaller Creates an external fragment – Larger May have to move/relocate the program • Allocate “holes” in memory according to – Best- /Worst- / First- /Next-fit 53

Contemporary Memory Allocation • Use some form of variable partitioning • Usually allocate memory in fixed-size blocks (pages) – Simplifies management of free list – Greatly complicates binding problem 54

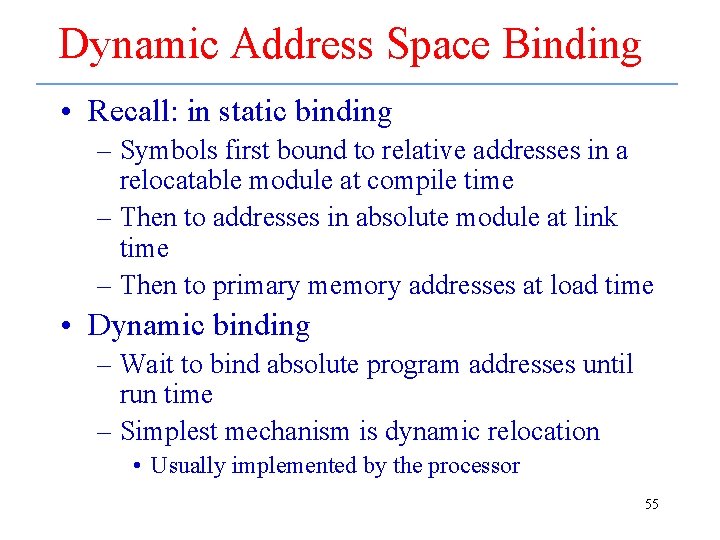

Dynamic Address Space Binding • Recall: in static binding – Symbols first bound to relative addresses in a relocatable module at compile time – Then to addresses in absolute module at link time – Then to primary memory addresses at load time • Dynamic binding – Wait to bind absolute program addresses until run time – Simplest mechanism is dynamic relocation • Usually implemented by the processor 55

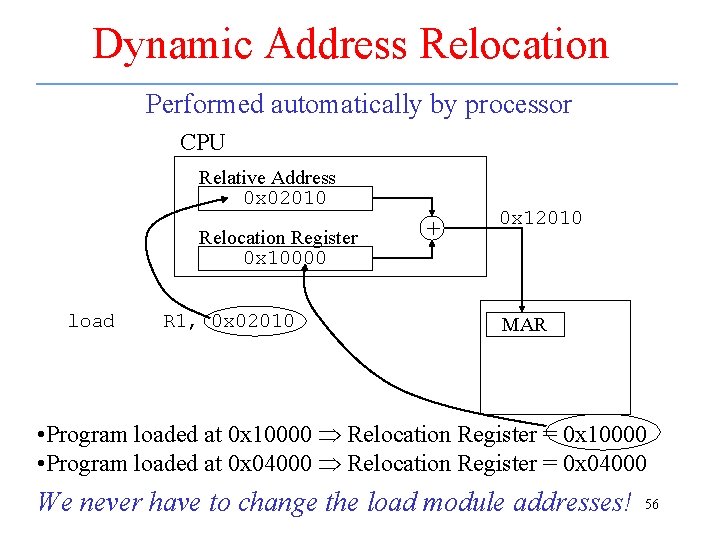

Dynamic Address Relocation Performed automatically by processor CPU Relative Address 0 x 02010 Relocation Register 0 x 10000 load R 1, 0 x 02010 + 0 x 12010 MAR • Program loaded at 0 x 10000 Relocation Register = 0 x 10000 • Program loaded at 0 x 04000 Relocation Register = 0 x 04000 We never have to change the load module addresses! 56

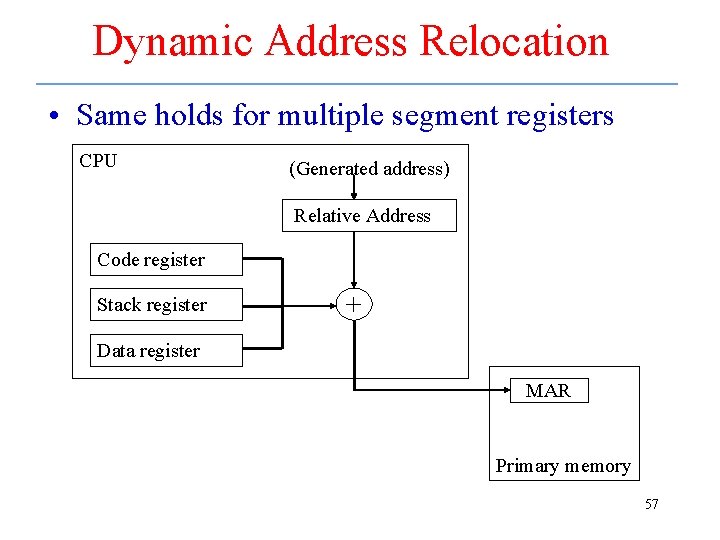

Dynamic Address Relocation • Same holds for multiple segment registers CPU (Generated address) Relative Address Code register Stack register + Data register MAR Primary memory 57

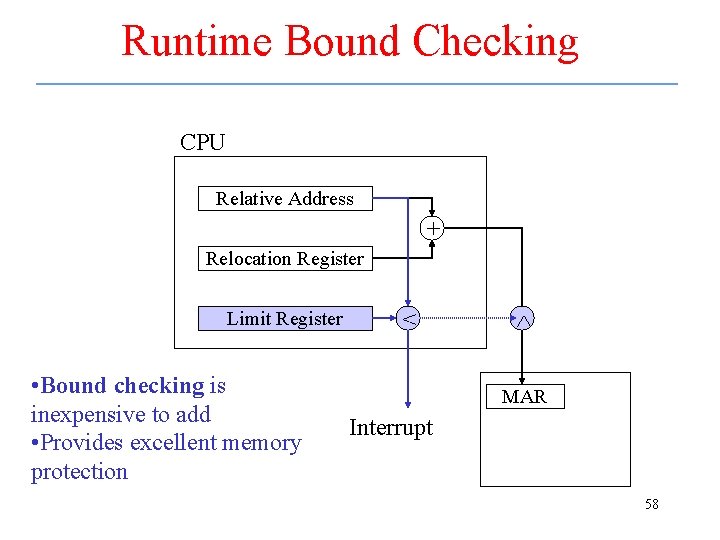

Runtime Bound Checking CPU Relative Address + Relocation Register Limit Register • Bound checking is inexpensive to add • Provides excellent memory protection < MAR Interrupt 58

Memory Mgmt Strategies • Fixed-Partition used only in batch systems • Variable-Partition used everywhere (except in virtual memory) • Swapping systems – Popularized in timesharing – Relies on dynamic address relocation • Dynamic Loading (Virtual Memory) – Exploit the memory hierarchy – Paging -- mainstream in contemporary systems • Shared-memory multiprocessors 59

Swapping • Special case of dynamic memory allocation • Suppose there is high demand for executable memory • Equitable policy might be to time-multiplex processes into the memory (also space-mux) • Means that process can have its address space unloaded when it still needs memory – Usually only happens when it is blocked 60

Swapping – cont. • Objective – Optimize system performance by removing a process from memory when it is blocked, allowing that memory to be used by other processes – Block may be caused by a request for a resource, or by the memory manager • Swapping only becomes necessary when processes are being denied access to memory 61

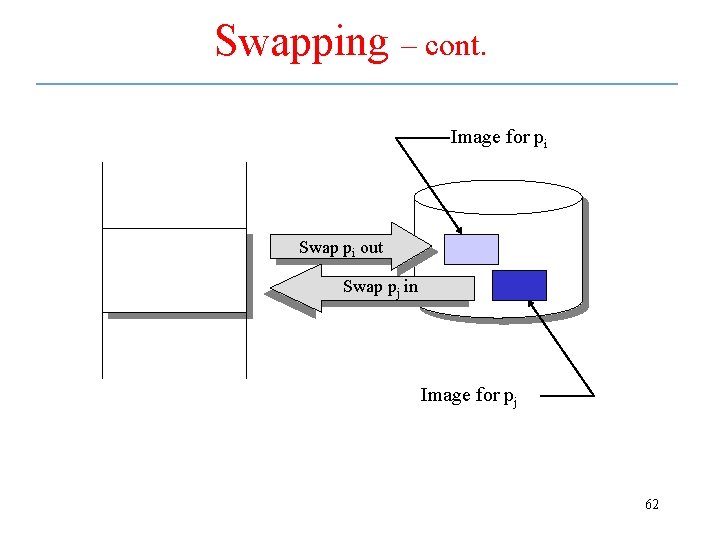

Swapping – cont. Image for pi Swap pi out Swap pj in Image for pj 62

Cost of Swapping • Need to consider time to copy execution image from primary to secondary memory, and back – This is the major part of the swap time • In addition, there is the time required by the memory manager, and the usual context switching time 63

Swapping Systems • Standard swapping used in few systems – Requires too much swapping time and provides too little execution time • Most systems do use some modified version of swapping – In UNIX, swapping is normally disabled, but will be enabled if memory usage reaches some threshold limit; when usage drops below the threshold, swapping is again disabled 64

Virtual Memory • Allows a process to execute when only part of its address space is loaded in primary memory – the rest is in secondary • Need to be able to partition the address space into parts that can be loaded into primary memory when needed 65

Virtual Memory – cont. • A characteristic of programs that is very important to the strategy used by virtual memory systems is spatial reference locality – Refers to the implicit partitioning of code and data segments due to the functioning of the program (portion for initializing data, another for reading input, others for computation, etc. ) • Can be used to select which parts of the process should be loaded into primary memory 66

Virtual Memory Barriers • Must be able to treat the address space in parts that correspond to the various localities that will exist during the programs execution • Must be able to load a part anywhere in physical memory and dynamically bind the addresses appropriately • More on this in next chapter 67

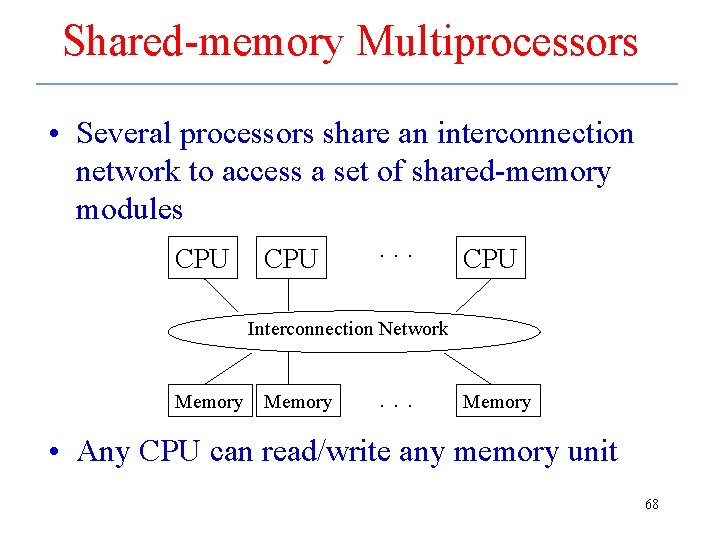

Shared-memory Multiprocessors • Several processors share an interconnection network to access a set of shared-memory modules CPU . . . CPU Interconnection Network Memory . . . Memory • Any CPU can read/write any memory unit 68

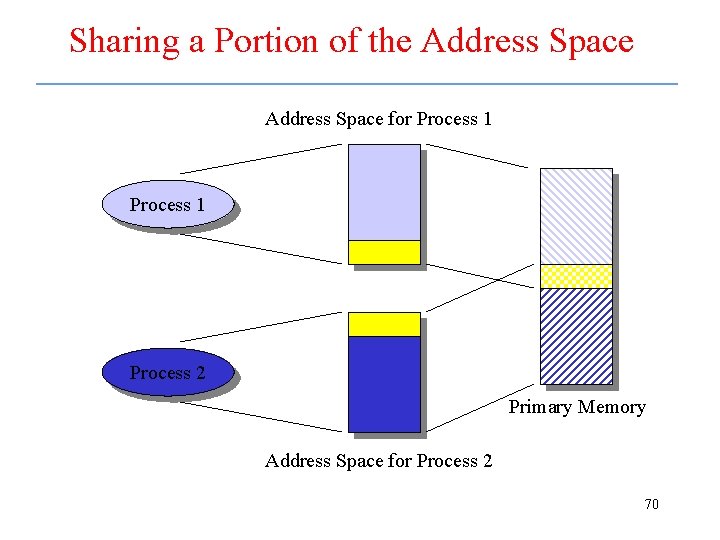

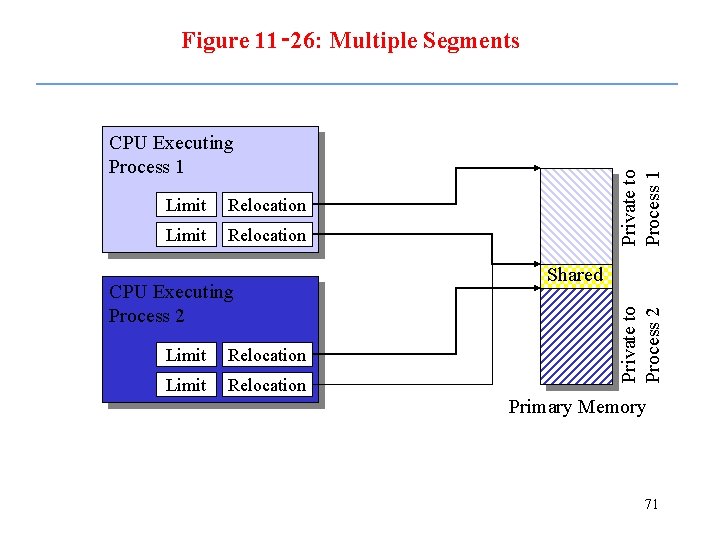

Shared-memory Multiprocessors – cont. • Goal is to use processes or threads to implement units of computation on different processors while sharing information via common primary memory locations • One technique would be to have the address spaces of two processes overlap • Another would split the address space of a process into a private part and a public part 69

Sharing a Portion of the Address Space for Process 1 Process 2 Primary Memory Address Space for Process 2 70

Figure 11‑ 26: Multiple Segments Relocation Limit Relocation CPU Executing Process 2 Limit Relocation Shared Private to Process 2 Limit Private to Process 1 CPU Executing Process 1 Primary Memory 71

Shared-memory Multiprocessors – cont. • A major problem is synchronization – How can one process detect when the other process has written or read information – Will need to use interprocess communication to handle the synchronization • Another problem is overloading the interconnection network – Use cache memories to decrease load on network 72

- Slides: 72