Medical Nutrition Therapy in Neurological Disorders Part 1

- Slides: 50

Medical Nutrition Therapy in Neurological Disorders Part 1

Nutrition and Neurologic Disease • • May have nutritional etiologies resulting from deficiency or excess May be nonnutritional in origin but have significant nutritional implications

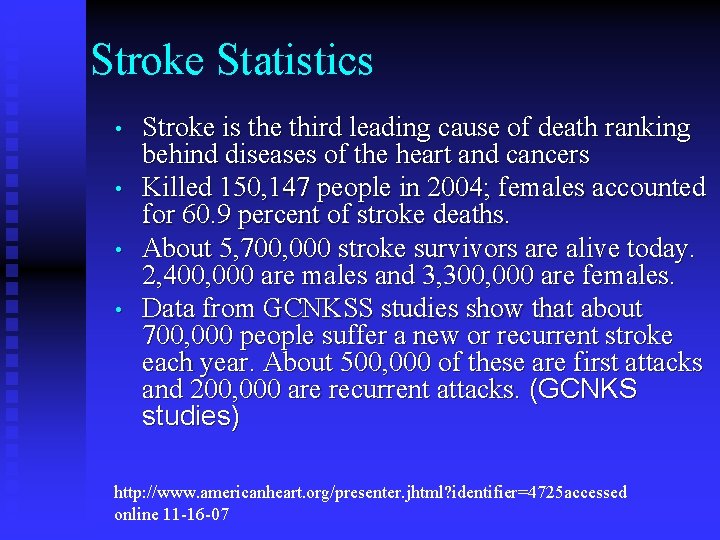

Stroke Statistics • • Stroke is the third leading cause of death ranking behind diseases of the heart and cancers Killed 150, 147 people in 2004; females accounted for 60. 9 percent of stroke deaths. About 5, 700, 000 stroke survivors are alive today. 2, 400, 000 are males and 3, 300, 000 are females. Data from GCNKSS studies show that about 700, 000 people suffer a new or recurrent stroke each year. About 500, 000 of these are first attacks and 200, 000 are recurrent attacks. (GCNKS studies) http: //www. americanheart. org/presenter. jhtml? identifier=4725 accessed online 11 -16 -07

Stroke Statistics • • From 1992 to 2002 the death rate from stroke declined 13. 8 percent, but the actual number of stroke deaths rose 6. 9 percent. A leading cause of functional disability – 15 -30% permanently disabled Primary Prevention of Ischemic Stroke, AHA/ASA Guideline, Stroke 2006; 37: 1583 -1633, accessed online 11 -16 -06

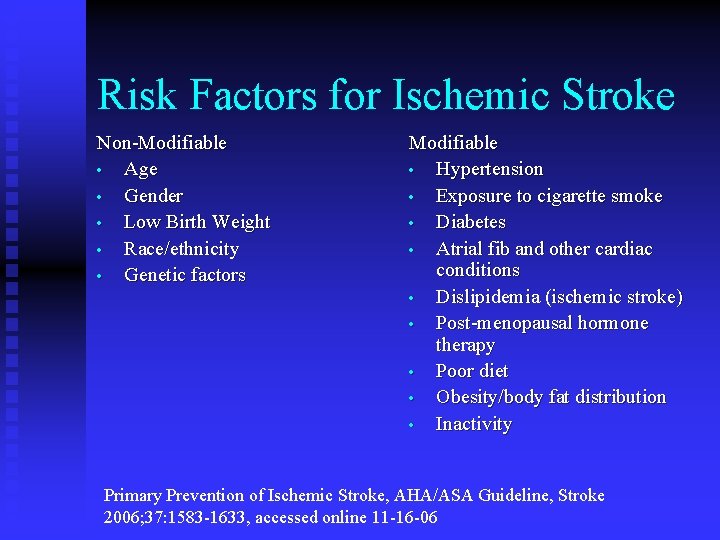

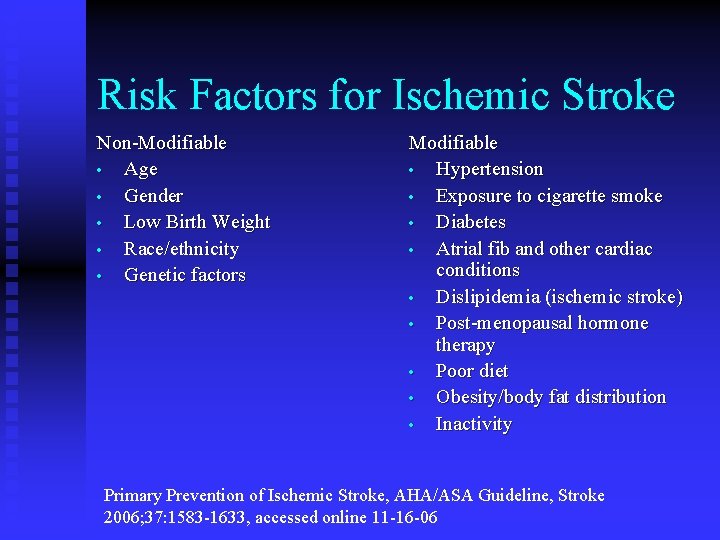

Risk Factors for Ischemic Stroke Non-Modifiable • Age • Gender • Low Birth Weight • Race/ethnicity • Genetic factors Modifiable • Hypertension • Exposure to cigarette smoke • Diabetes • Atrial fib and other cardiac conditions • Dislipidemia (ischemic stroke) • Post-menopausal hormone therapy • Poor diet • Obesity/body fat distribution • Inactivity Primary Prevention of Ischemic Stroke, AHA/ASA Guideline, Stroke 2006; 37: 1583 -1633, accessed online 11 -16 -06

Pathophysiology of Stroke • 85% of strokes caused by a thromboembolic event (related to atherosclerosis, hypertension, diabetes, gout) • Embolic stroke: cholesterol plaque is dislodged from vessel, travels to the brain, blocks an artery • Thrombotic stroke: cholesterol plaque within an artery ruptures, platelets aggregate and clog a narrow artery

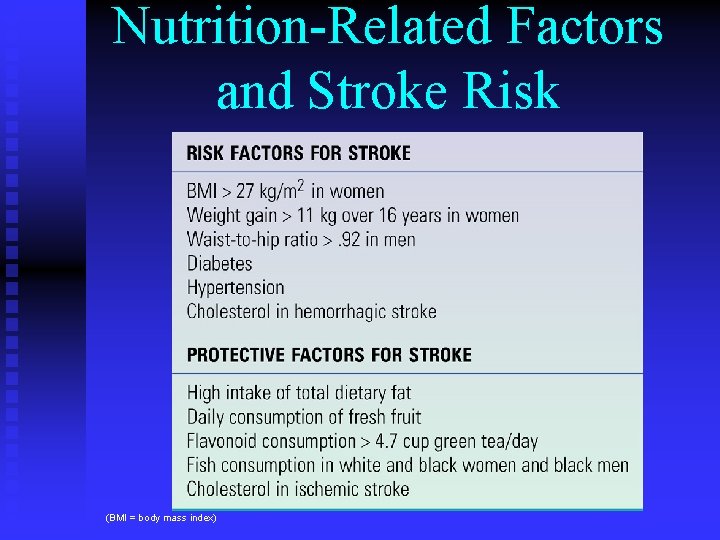

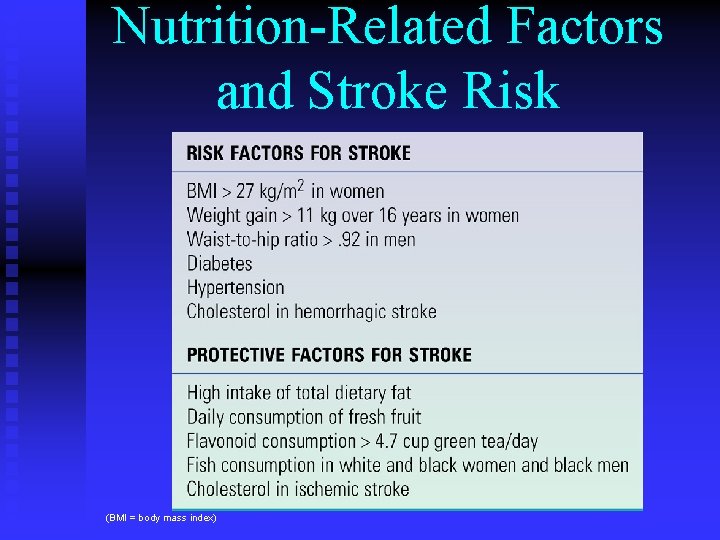

Nutrition-Related Factors and Stroke Risk (BMI = body mass index)

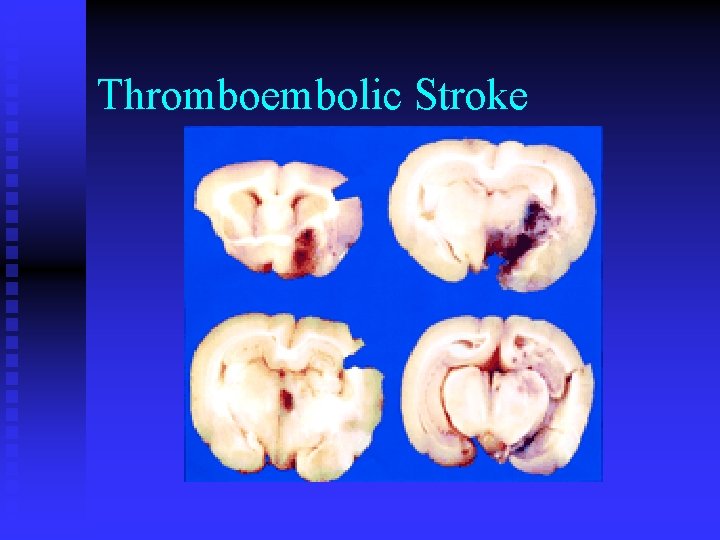

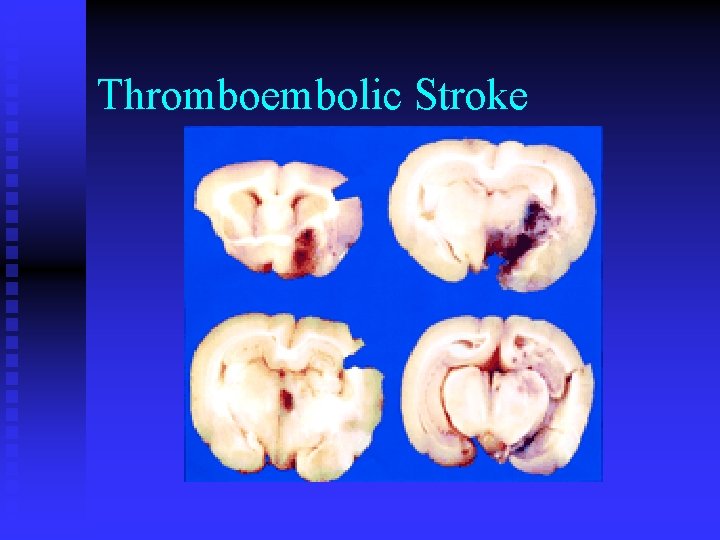

Thromboembolic Stroke

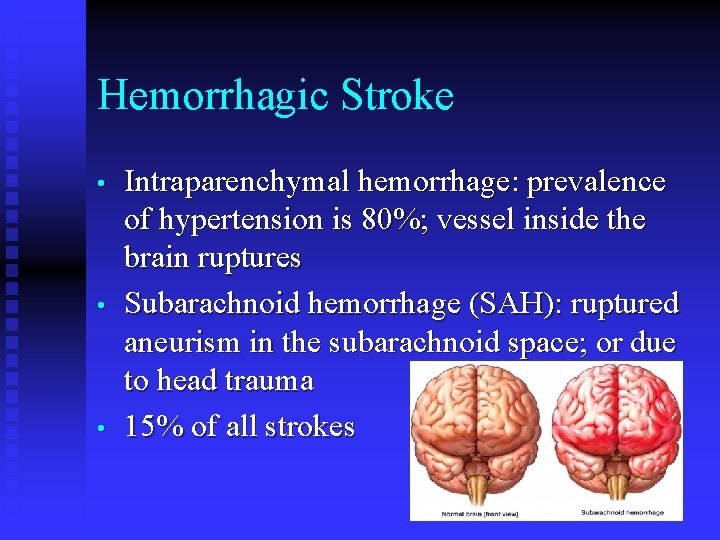

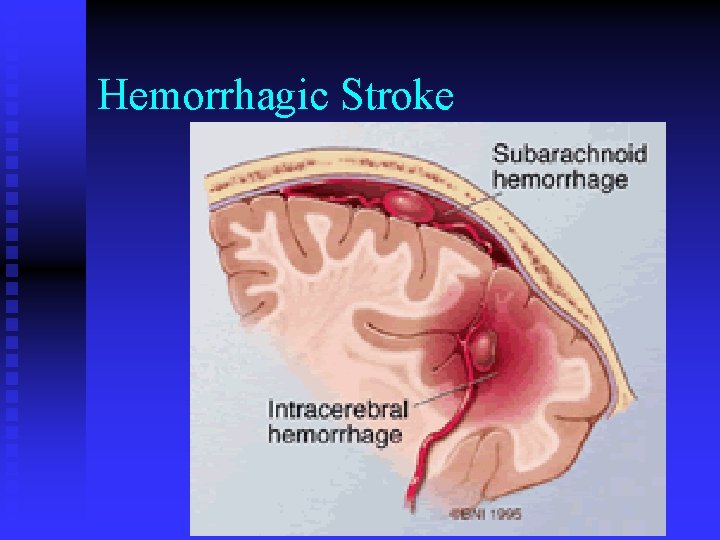

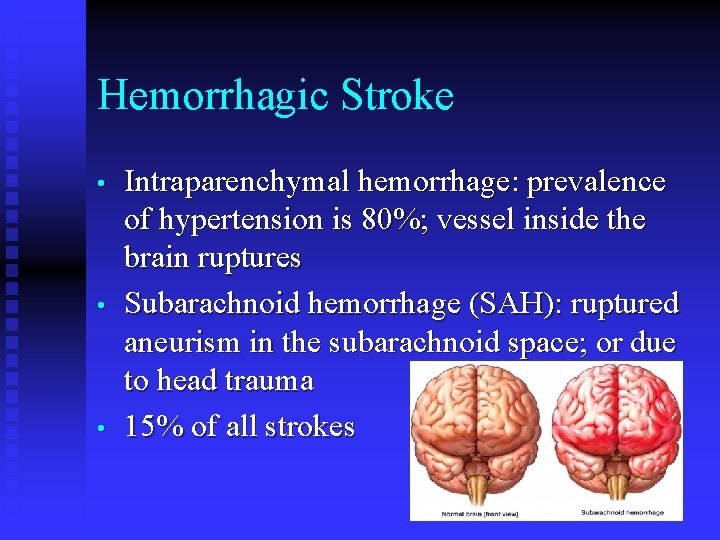

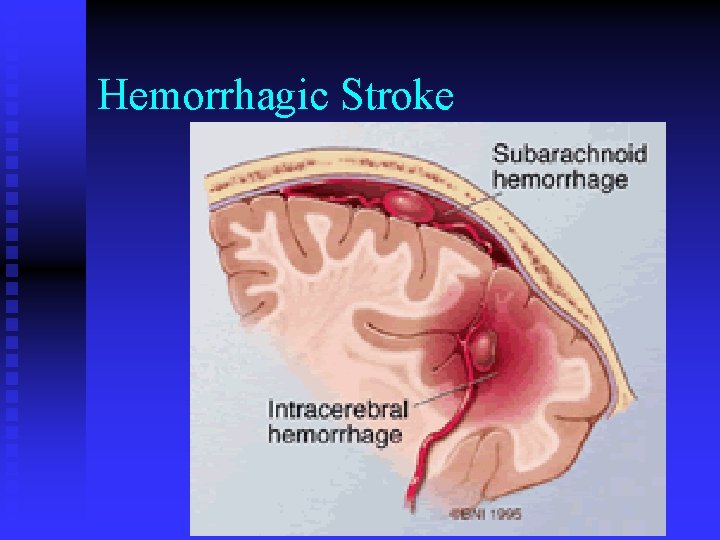

Hemorrhagic Stroke • • • Intraparenchymal hemorrhage: prevalence of hypertension is 80%; vessel inside the brain ruptures Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH): ruptured aneurism in the subarachnoid space; or due to head trauma 15% of all strokes

Hemorrhagic Stroke

Medical Treatment for Stroke • • Thrombolytic or “clot-busting” drugs to restore perfusion to affected areas within 6 hours of onset of stroke Controlling intracranial pressure (ICP) while maintaining sufficient perfusion of the brain

Nutritional Management in Stroke • • • Primary prevention Acute management (screening for dysphagia and nutritional risk) Intervention for swallowing disorders via consistency changes

AHA Guidelines for Primary Prevention of CVD and Stroke: 2006 Update • • • Smoking: complete cessation (Class I, evidence level B Avoid exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (Class IIA, evidence C) BP control: goal <140/90 mm. Hg with lower targets in some subgroups (<130/80 in diabetes) Goldstein et al, Primary Prevention of Ischemic Stroke, Stroke 2006; 37: 15831633)

AHA Guidelines for Primary Prevention of CVD and Stroke: 2006 Update • Blood lipid mgt: • NCP III guidelines for pts who have not had a stroke and have high TC or non-HDL-C w/ high TG • Pts with known CAD and high risk HTN even w/ normal LDL treat with lifestyle/statin (Class I, evidence A) • Rec wt loss, ↑ physical activity, smoking cessation, niacin or gemfibrozil (Class IIA, evidence B) Goldstein et al, Primary Prevention of Ischemic Stroke, Stroke 2006; 37: 1583 -1633)

AHA Diet/Lifestyle Guidelines for Primary Prevention of CVD/Stroke: 2006 Update • • • Reduced intake of sodium and increased intake of potassium to lower blood pressure (Class I, evidence A) Recommended sodium intake <2. 3 g/day; potassium >4. 7 g/day DASH diet emphasizing fruits, vegetables, lowfat dairy products is recommended to lower BP (Class I, evidence A) High fruit and vegetable intake may lower risk of stroke (Evidence C) Wt reduction is recommended because it lowers BP Increased physical activity (>30 minutes of moderateintensity activity daily) Pearson et al. (Circulation. 2002; 106: 388 -391. )

Lipids and Stroke • • • Cholesterol is a very weak risk factor for ischemic stroke, in contrast to CAD Cholesterol reduction with diet and nonstatin drugs is not effective in stroke prevention, although reductions in levels of cholesterol are modest Statins produce a statistically significant 25% reduction in the risk of stroke Briel M, et al Am J Med 2004; 117: 596 -606

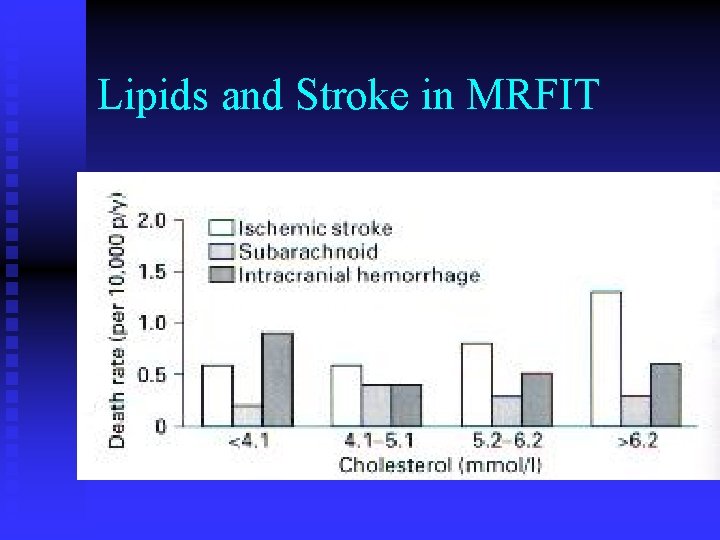

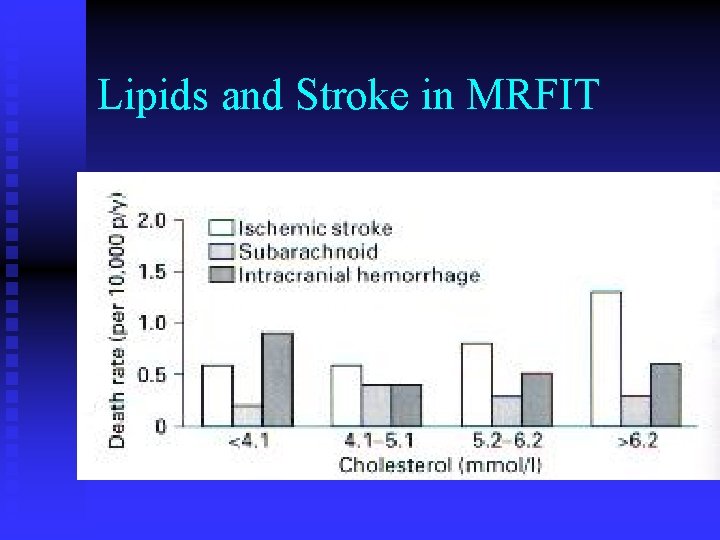

Lipids and Stroke in MRFIT

Lipids and Stroke: ARIC Study • • • Cohort study of 14, 175 men and women After 10 -year followup, there weak and inconsistent associations between ischemic stroke and LDL-C, HDL-C, apo-B, apo-A-1, triglycerides Most consistent relationship was lower risk in women with higher HDL and higher risk with lower TG Shahar E, et al. Stroke, 2003; 34: 623 -631

Lipids and Stroke • • Problem may be the heterogenicity of stroke, although even when looking at homogeneous ischemic stroke, relationship is weak The protective effect of statins may be due to their non-cholesterol-lowering effects.

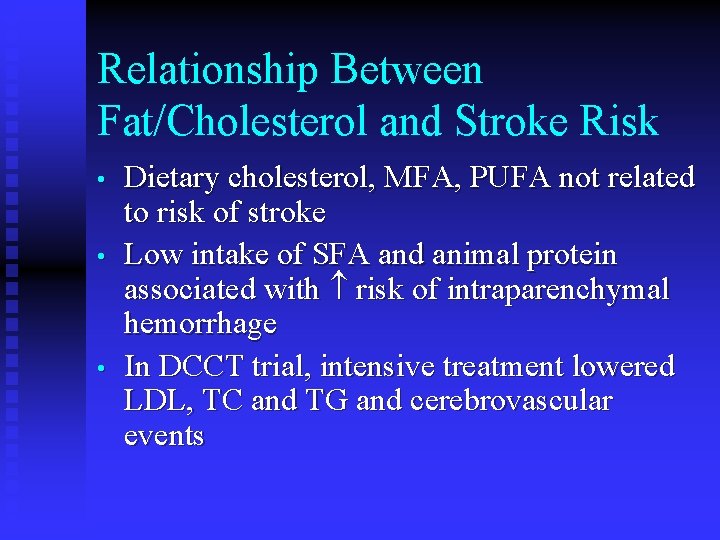

Relationship Between Fat/Cholesterol and Stroke Risk • • • Dietary cholesterol, MFA, PUFA not related to risk of stroke Low intake of SFA and animal protein associated with risk of intraparenchymal hemorrhage In DCCT trial, intensive treatment lowered LDL, TC and TG and cerebrovascular events

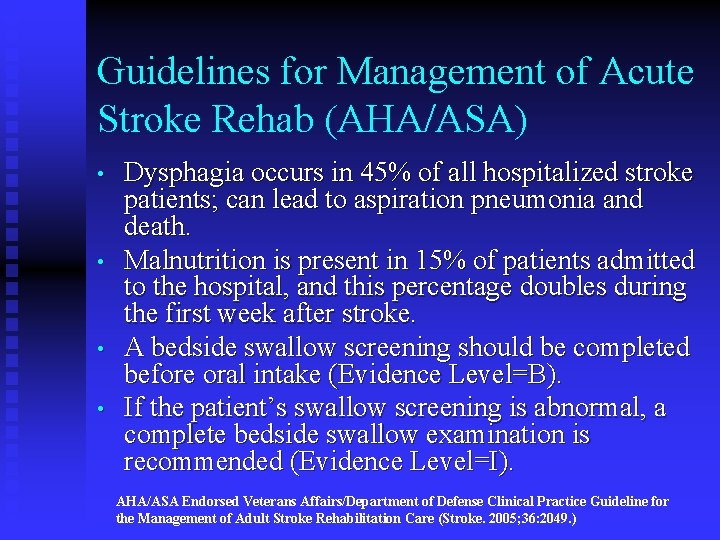

Guidelines for Management of Acute Stroke Rehab (AHA/ASA) • • Dysphagia occurs in 45% of all hospitalized stroke patients; can lead to aspiration pneumonia and death. Malnutrition is present in 15% of patients admitted to the hospital, and this percentage doubles during the first week after stroke. A bedside swallow screening should be completed before oral intake (Evidence Level=B). If the patient’s swallow screening is abnormal, a complete bedside swallow examination is recommended (Evidence Level=I). AHA/ASA Endorsed Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Adult Stroke Rehabilitation Care (Stroke. 2005; 36: 2049. )

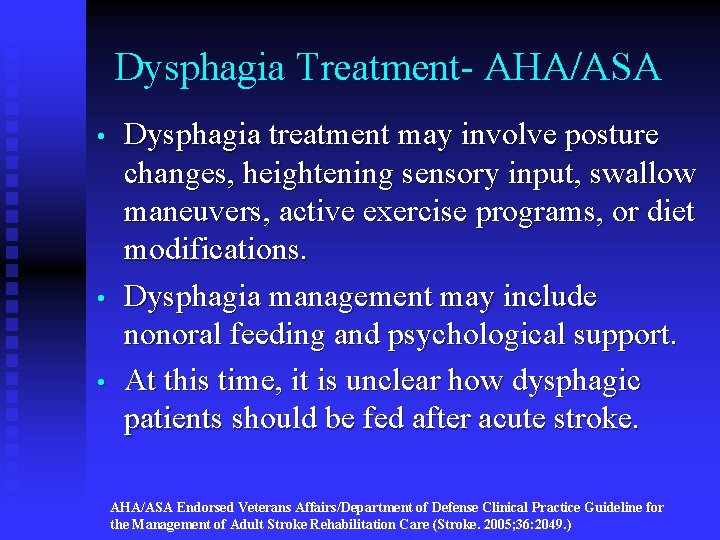

Dysphagia Treatment- AHA/ASA • • • Dysphagia treatment may involve posture changes, heightening sensory input, swallow maneuvers, active exercise programs, or diet modifications. Dysphagia management may include nonoral feeding and psychological support. At this time, it is unclear how dysphagic patients should be fed after acute stroke. AHA/ASA Endorsed Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Adult Stroke Rehabilitation Care (Stroke. 2005; 36: 2049. )

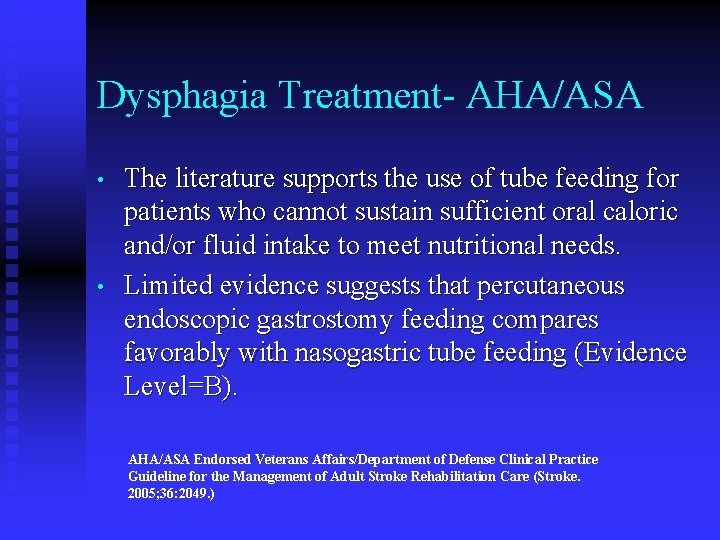

Dysphagia Treatment- AHA/ASA • • The literature supports the use of tube feeding for patients who cannot sustain sufficient oral caloric and/or fluid intake to meet nutritional needs. Limited evidence suggests that percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding compares favorably with nasogastric tube feeding (Evidence Level=B). AHA/ASA Endorsed Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Adult Stroke Rehabilitation Care (Stroke. 2005; 36: 2049. )

FOOD (Feed or Ordinary Diet) Trial • • • Tested feeding strategies after acute stroke including oral supplementation, early vs delayed NG feeding, and NG vs PEG feeding Poor baseline nutritional status is associated with worse outcomes at 6 months. This relationship persists after adjustment for pt’s age, prestroke functional level, living conditions, and severity of stroke. AHA/ASA Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients with Ischemic Stroke. (Stroke. 2005; 36: 916. )

FOOD (Feed or Ordinary Diet) Trial • • • Found no benefit to routine oral supplementation of post-stroke patients who had not been identified as malnourished (1) Early tube feeding was associated with an absolute reduction in risk of death of 5. 8% (p=0. 09) and a reduction in death or poor outcome of 1. 2% (p=0. 7) (2) PEG feeding (vs NG) was associated with an absolute increase in risk of death of 1. 0%, p=0. 9) and an increased risk of death or poor outcome of 7. 8% (p=0. 05). 1: Lancet. 2005 Feb 26 -Mar 4; 365(9461): 755 -63. 2: Lancet. 2005 Feb 26 Mar 4; 365(9461): 764 -72

AHA Guidelines for Early Management of Pts with Ischemic Stroke • • A poor nutritional status was associated with an increased risk of infections including pneumonia, gastrointestinal bleeding, and pressure sores. These data provide a strong rationale for assessment of the patient’s nutritional status at the time of admission. AHA/ASA Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients with Ischemic Stroke. (Stroke. 2005; 36: 916. )

Alzheimer’s Disease • • Most common form of dementia Increases exponentially after age 40 Prevalence in white males at age 100 is 41. 5% Higher prevalence in women (3 X) due to lower mortality

Symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease • • • Forgetfulness: may forget recent events, activities, names of familiar people or things (anomia). Forget how to do simple tasks, such as brushing teeth, brushing hair Get lost in familiar surroundings Repeat words spoken by others (echolalia) Loss of comprehension (agnosia)

Symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease (cont) • • • Motor skills deteriorate: loss of reflexes and shuffling gait Bowel and bladder control lost Limb weakness and contractures Intellectual activity ceases Vegetative state

Alzheimer’s Disease Risk Factors • • • Age: risk doubles every five years after age 65 Family history: early onset strongly hereditary; late onset has a genetic component Those with a parent or sibling with AD are 2 -3 times more likely to develop AD

Alzheimer’s Disease Risk Factors • • Head injury Down syndrome Low level of education Female gender

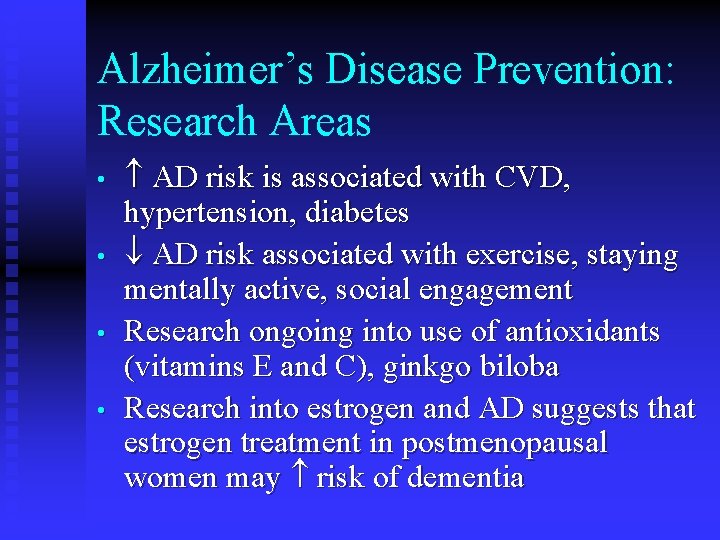

Alzheimer’s Disease Prevention: Research Areas • • AD risk is associated with CVD, hypertension, diabetes AD risk associated with exercise, staying mentally active, social engagement Research ongoing into use of antioxidants (vitamins E and C), ginkgo biloba Research into estrogen and AD suggests that estrogen treatment in postmenopausal women may risk of dementia

Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease • • • No drug can stop or reverse AD Some drugs may slow progress (tacrine (Cognex®), donepezil (Aricept®), rivastigmine (Exelon®), or galantamine (Razadyne®) Other medications may treat symptoms such as sleeplessness, agitation, wandering, anxiety, and depression National Institutes on Aging, Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral Center http: //www. alzheimers. org/treatment. htm

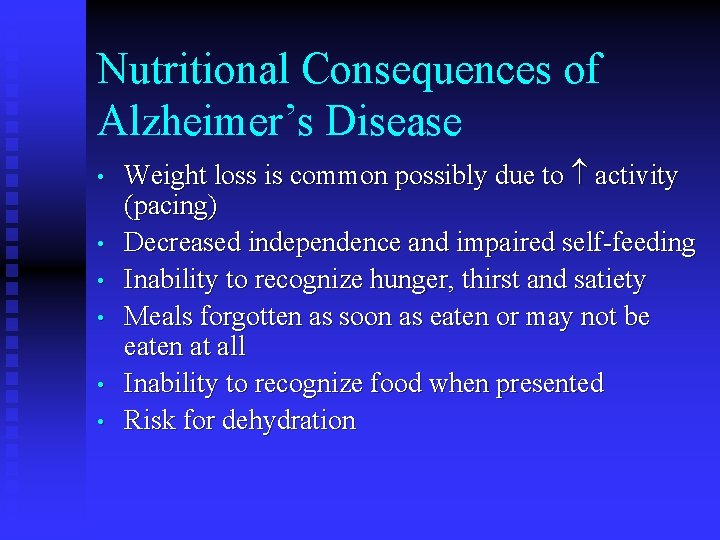

Nutritional Consequences of Alzheimer’s Disease • • • Weight loss is common possibly due to activity (pacing) Decreased independence and impaired self-feeding Inability to recognize hunger, thirst and satiety Meals forgotten as soon as eaten or may not be eaten at all Inability to recognize food when presented Risk for dehydration

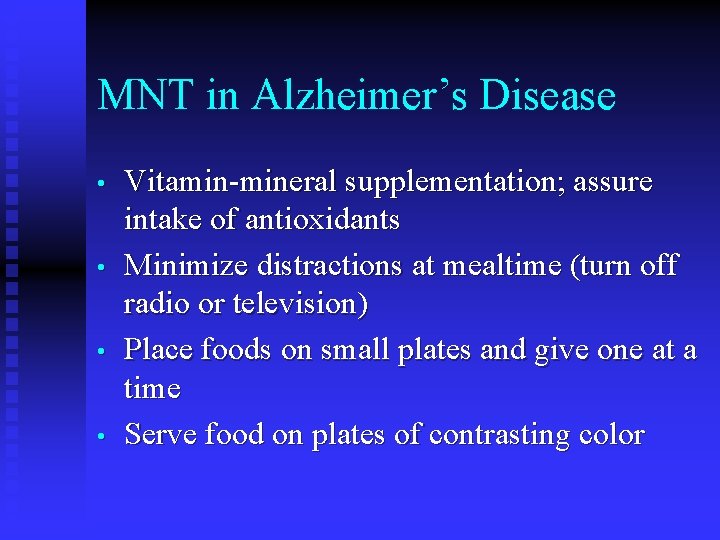

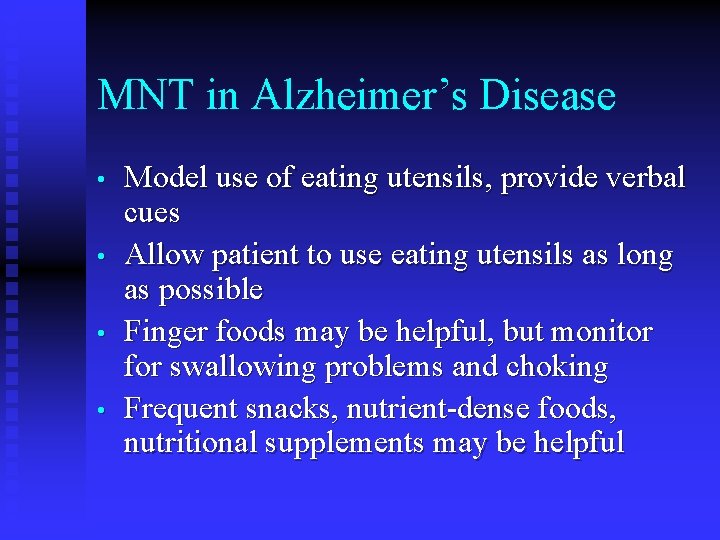

MNT in Alzheimer’s Disease • • Vitamin-mineral supplementation; assure intake of antioxidants Minimize distractions at mealtime (turn off radio or television) Place foods on small plates and give one at a time Serve food on plates of contrasting color

MNT in Alzheimer’s Disease • • Model use of eating utensils, provide verbal cues Allow patient to use eating utensils as long as possible Finger foods may be helpful, but monitor for swallowing problems and choking Frequent snacks, nutrient-dense foods, nutritional supplements may be helpful

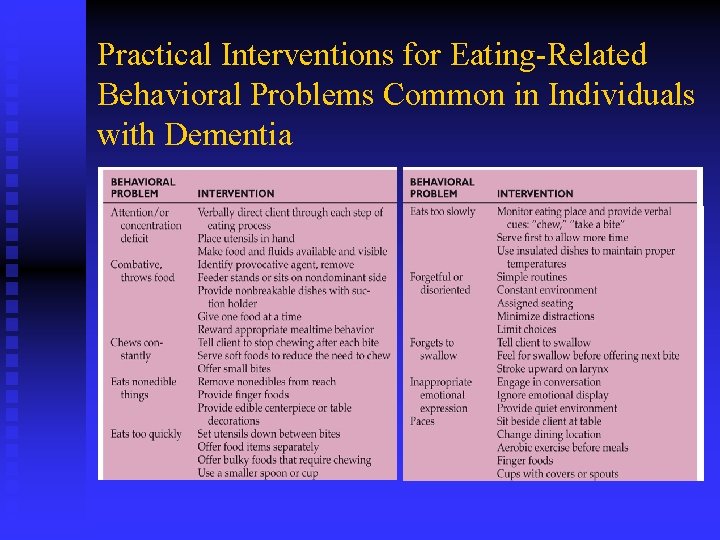

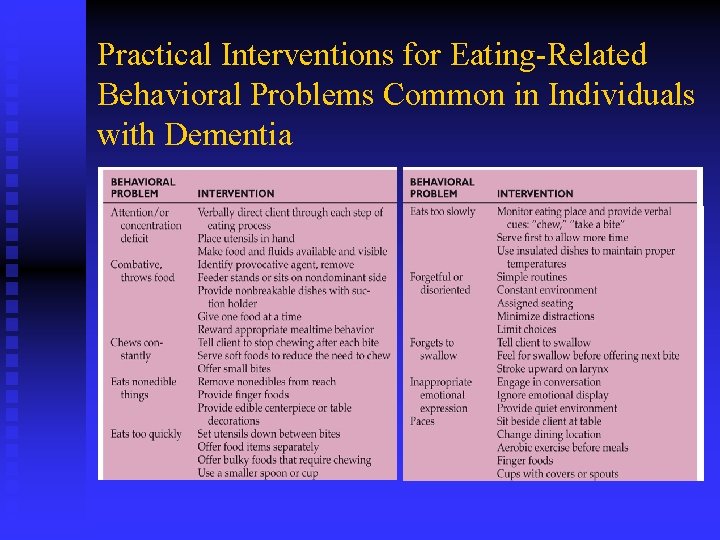

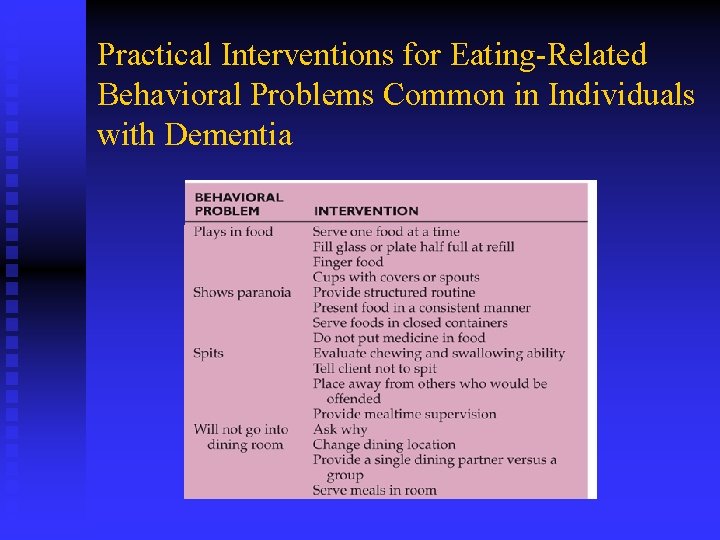

Practical Interventions for Eating-Related Behavioral Problems Common in Individuals with Dementia

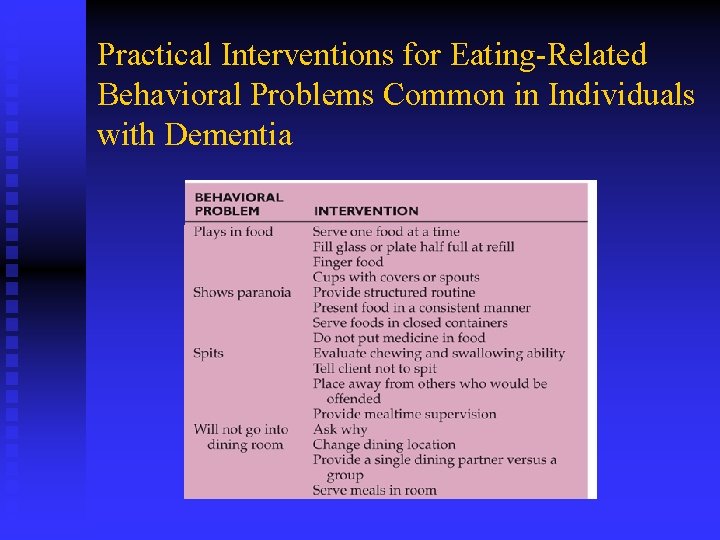

Practical Interventions for Eating-Related Behavioral Problems Common in Individuals with Dementia

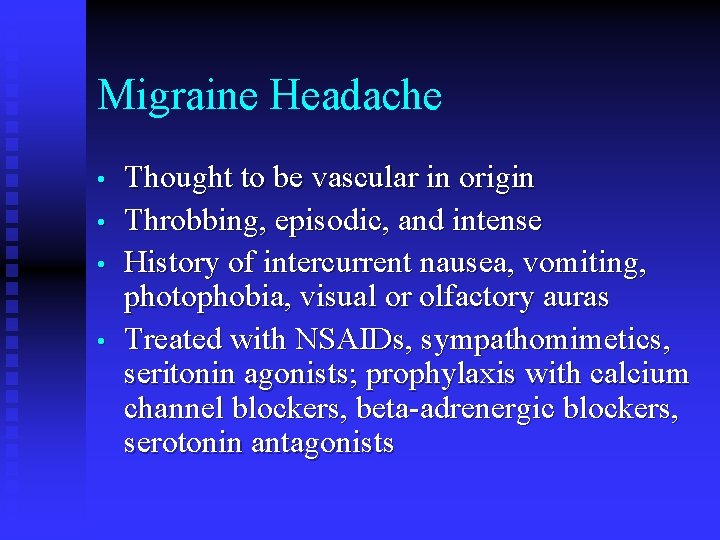

Migraine Headache • • Thought to be vascular in origin Throbbing, episodic, and intense History of intercurrent nausea, vomiting, photophobia, visual or olfactory auras Treated with NSAIDs, sympathomimetics, seritonin agonists; prophylaxis with calcium channel blockers, beta-adrenergic blockers, serotonin antagonists

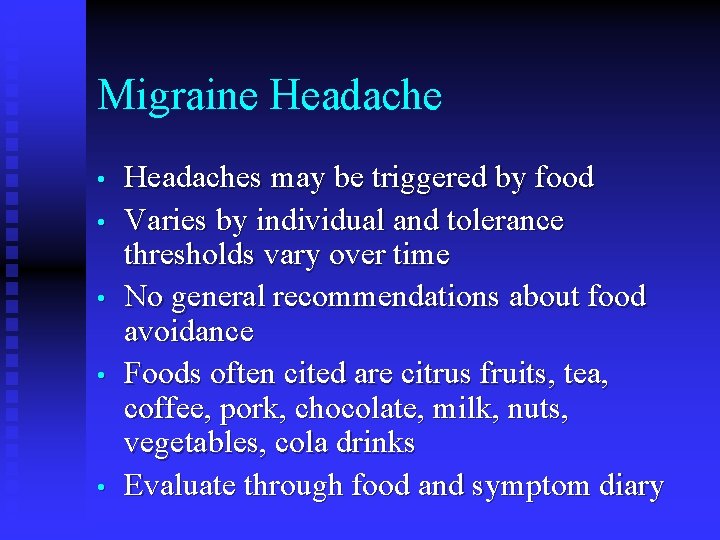

Migraine Headache • • • Headaches may be triggered by food Varies by individual and tolerance thresholds vary over time No general recommendations about food avoidance Foods often cited are citrus fruits, tea, coffee, pork, chocolate, milk, nuts, vegetables, cola drinks Evaluate through food and symptom diary

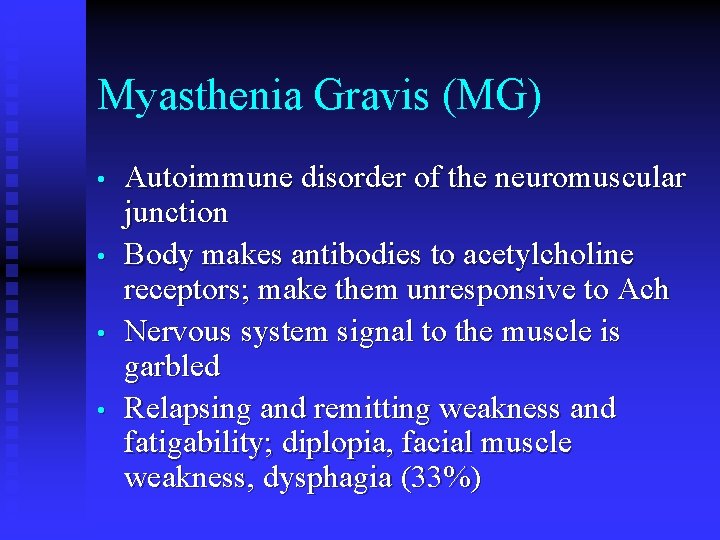

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) • • Autoimmune disorder of the neuromuscular junction Body makes antibodies to acetylcholine receptors; make them unresponsive to Ach Nervous system signal to the muscle is garbled Relapsing and remitting weakness and fatigability; diplopia, facial muscle weakness, dysphagia (33%)

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) Medical Treatment • • • Anticholinesterases inhibit acetylcholesterase and increase the amount of Ach Removal of the thymus gland Corticosteroids

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) MNT • • • Nutritionally dense foods at the beginning of meals before the patient tires Small frequent meals Time medication with feeding to facilitate optimal swallowing Limit physical activity before meals Don’t encourage food consumption when patient is tired; may aspirate

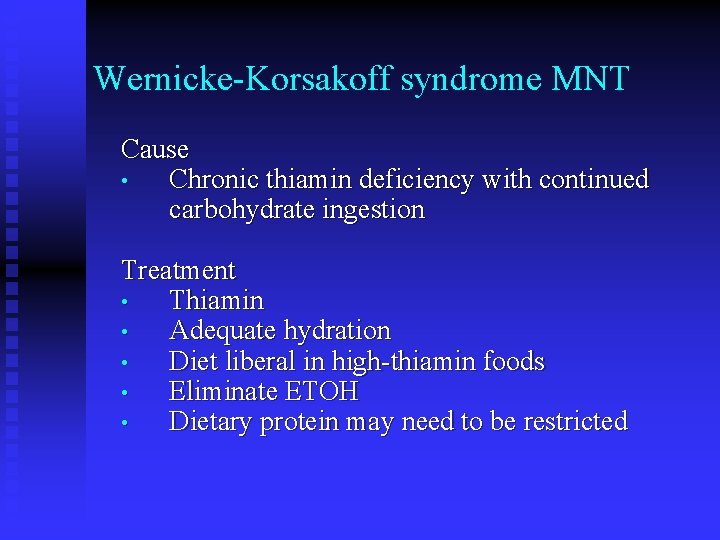

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome MNT Cause • Chronic thiamin deficiency with continued carbohydrate ingestion Treatment • Thiamin • Adequate hydration • Diet liberal in high-thiamin foods • Eliminate ETOH • Dietary protein may need to be restricted

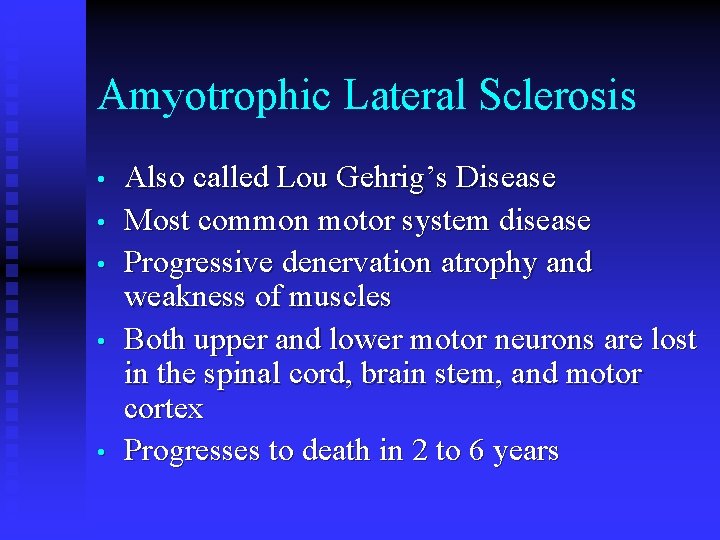

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis • • • Also called Lou Gehrig’s Disease Most common motor system disease Progressive denervation atrophy and weakness of muscles Both upper and lower motor neurons are lost in the spinal cord, brain stem, and motor cortex Progresses to death in 2 to 6 years

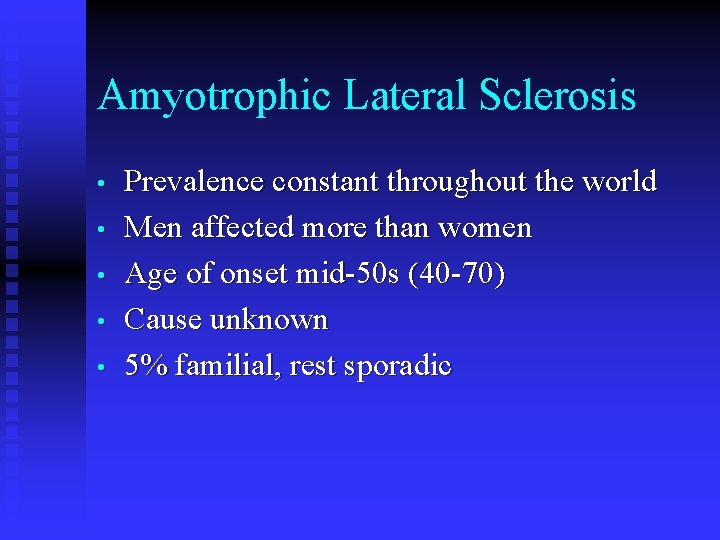

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis • • • Prevalence constant throughout the world Men affected more than women Age of onset mid-50 s (40 -70) Cause unknown 5% familial, rest sporadic

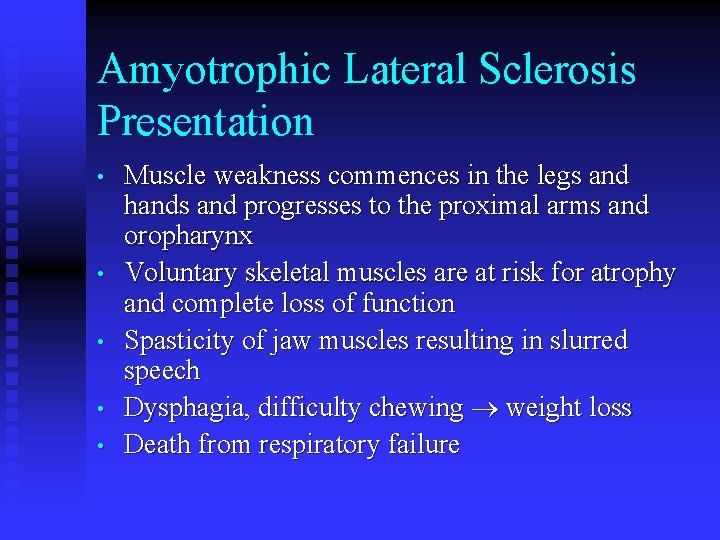

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Presentation • • • Muscle weakness commences in the legs and hands and progresses to the proximal arms and oropharynx Voluntary skeletal muscles are at risk for atrophy and complete loss of function Spasticity of jaw muscles resulting in slurred speech Dysphagia, difficulty chewing weight loss Death from respiratory failure

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Nutritional Implications • • • Dysphagia, chewing, swallowing problems Decreased body fat, lean body mass, nitrogen balance and increased REE as death approaches Late stage patients may not tolerate PEG placement d/t respiratory compromise Initiate discussions about whether to place a feeding tube early in disease process Enteral feedings do not prolong life

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis MNT • • Correlates with ALS Severity Scale (pp 11021103) Emphasize fluids as patients may limit fluids d/t toileting difficulties Get baseline weight; 10% loss increased risk Modify consistency as eating problems develop using easy-chew foods, thickened liquids, using small frequent meals, cool food temperatures

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis MNT • • If nutrition support is planned, use EN Initiate early rather than later; dehydration occurs before malnutrition Purpose of nutrition support should be to enhance quality of life Eventually patients will not be able to manage oral secretions

Medical nutrition therapy for stroke

Medical nutrition therapy for stroke Medical nutrition therapy for hypertension

Medical nutrition therapy for hypertension Small bowel obstruction medical nutrition therapy

Small bowel obstruction medical nutrition therapy Fundamentals of nursing nutrition

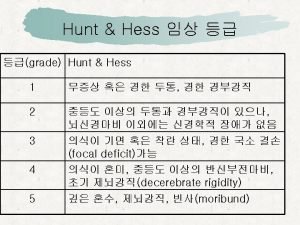

Fundamentals of nursing nutrition World federation of neurological surgeons scale

World federation of neurological surgeons scale Neuro checks pupil size

Neuro checks pupil size Motor function neurological assessment

Motor function neurological assessment What is focal neurological signs

What is focal neurological signs Level of consciousness assessment

Level of consciousness assessment Is adhd a neurological disorder

Is adhd a neurological disorder Mrc grade

Mrc grade Haapsalu neurological rehabilitation centre

Haapsalu neurological rehabilitation centre Neurological based behavior

Neurological based behavior Neurological examination

Neurological examination Muscle power neurological examination

Muscle power neurological examination Neurological exam

Neurological exam Neurological considerations in language acquisition

Neurological considerations in language acquisition What is trait theory in criminology

What is trait theory in criminology Solent physiotherapy

Solent physiotherapy Papilloedema

Papilloedema Neurological disease

Neurological disease Amy lee plastic surgery

Amy lee plastic surgery Ryan waters neurosurgeon

Ryan waters neurosurgeon Neurological observations glasgow coma scale

Neurological observations glasgow coma scale Both psychoanalysis and humanistic therapy stress

Both psychoanalysis and humanistic therapy stress Bioness integrated therapy system occupational therapy

Bioness integrated therapy system occupational therapy Humanistic therapy aims to

Humanistic therapy aims to Medical family therapy

Medical family therapy Jay haley strategic family therapy

Jay haley strategic family therapy Schools of family therapy

Schools of family therapy California medical license for foreign medical graduates

California medical license for foreign medical graduates Gbmc infoweb

Gbmc infoweb Difference between medical report and medical certificate

Difference between medical report and medical certificate Torrance memorial map

Torrance memorial map Cartersville medical center medical records

Cartersville medical center medical records Part part whole addition

Part part whole addition Unit ratio definition

Unit ratio definition Brainpop ratios

Brainpop ratios Technical description

Technical description Parts of a pub

Parts of a pub The phase of the moon you see depends on ______.

The phase of the moon you see depends on ______. Minitab adalah

Minitab adalah Unit 14 physiological disorders examples

Unit 14 physiological disorders examples Unit 14 health and social care level 3

Unit 14 health and social care level 3 Neurocognitive disorders

Neurocognitive disorders Bipolar and other related disorders

Bipolar and other related disorders Bipolar and other related disorders

Bipolar and other related disorders Flinders model

Flinders model Assistive technology for emotional disturbance

Assistive technology for emotional disturbance Somatization disorder

Somatization disorder Egodystone

Egodystone