Medical Communication Grace Varas DO UT Health Division

- Slides: 70

Medical Communication Grace Varas, DO UT Health Division of Geriatric & Palliative Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine

Why communication skills? w w w Important for all medical professionals Skills are lacking w Undertrained w Overconfident CAN be learned (Procedure, Mnemonics) Patient/family satisfaction Quality Care

Risk for BURN Out w w Clinicians report dissatisfaction with family communication. >70% of clinicians report perceived conflicts with other staff or family, typically surrounding decision-making for patients at high risk of dying. Conflicts were often severe and were significantly associated with job strain. Part of the reason that one third of physicians and one half of nurses report being “burned out. ” IPAL-ICU

Where to Begin? w w Medical communication literature is relatively novel. First, we looked to the business (!) communication literature.

Getting to YES w w Separate the people from the problem. Focus on interests, not positions. Invent options for mutual gain. Insist on using objective criteria. Roger Fisher et al. Getting to YES: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In 1981 New York: Penguin Books.

Five Fundamental Skills 1. A Central Skill: "Ask-Tell-Ask. “ 2. When You Are Stuck, Ask for More Information: “Tell Me More. ” 3. Use reflections rather than questions to learn more 4. Skills for Responding to Emotion. 5. Assess the Other Person's Informational, Decision-making and Coping Style.

Skill 1 "Ask-Tell-Ask. " w Ask the family to describe their current understanding of the issue. w Tell the family what you need to communicate w Ask the family WHAT (not IF) they understood of what you just said.

Skill 2: When You Are Stuck, Ask for More Info: “Tell Me More. ” Remember that every conversation really has at least three levels: 1. "What is happening? " 2. "How do I feel about this? " 3. "What does this mean to me? “

Ways to Ask for More Some examples of useful invitations to "tell me more” include the following: w w w "Could you tell me more about what information you need at this point? ” "Could you say something about how you are feeling about what we’ve discussed? ” "Could you tell me what this means for you and your life? ”

Skill 3: Use reflections rather than questions to learn more w w w Simple reflections paraphrase what the person said and do not add meaning or interpretation. Complex reflections, on the other hand, go beyond what person says and includes the clinicians’ thoughts about speaker’s underlying emotions, values, or beliefs. These reflections are riskier because clinicians can be incorrect. Pollak K, Childers JW, Arnold RM. Applying motivational interviewing techniques to palliative care communication

Reflective Statements Serve three functions: 1. Convey empathy 2. Empower the patient/family 3. Allows silence and time to explore the complexity of decision-making Pollak K, Childers JW, Arnold RM. Applying motivational interviewing techniques to palliative care communication

Skill 4: Responding to Emotion w w Strong emotions – disbelief, sadness, anger, frustration and hopelessness – are normal when there is potential for death, loss of physical function, social function or quality of life When people are experiencing strong emotions they are less able to hear cognitive information or make decisions.

Skill 4: Responding to Emotion w w Being empathic is associated with family satisfaction and trust. w What most people want when expressing strong emotions is to feel that their situation and emotions are heard and appreciated. Acting empathically can enable patients to connect their emotional reactions to their own important values.

Skill 5: Assess the Other Person's Informational, Decision-making and Coping Style w w A recent study found that some family members want to hear the doctor’s recommendations about what to do, others specifically said that they did not feel it was the doctor’s role to give recommendations. What is a clinician to do? w Find out who you’re talking to!

Monitors & Blunters w w w People who use problem-focused coping have been termed “monitors. ” As their loved one’s condition worsens beyond the possibility of recovery, they hit a wall in seeking information. May be helpful to gently shift them towards acknowledging their emotions (NURSE). Miller, S. M. (1987). Monitoring and blunting: validation of a questionnaire to assess styles of information seeking under threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 345– 353

Monitors & Blunters w w w People who use emotion-focused coping are termed "blunters. " May not be ready to go beyond denial with you until they have developed a very high level of trust. It may be necessary to contain their emotions and shift them towards information and practical planning using "ask-tell-ask. " Miller, S. M. (1987). Monitoring and blunting: validation of a questionnaire to assess styles of information seeking under threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 345– 353

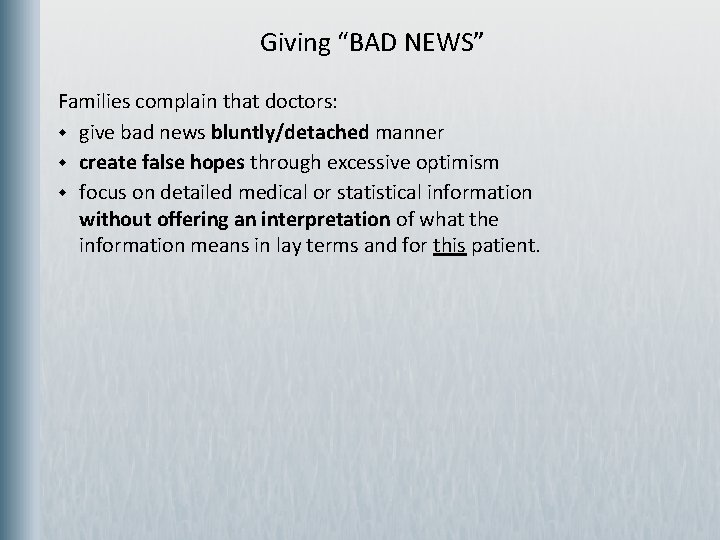

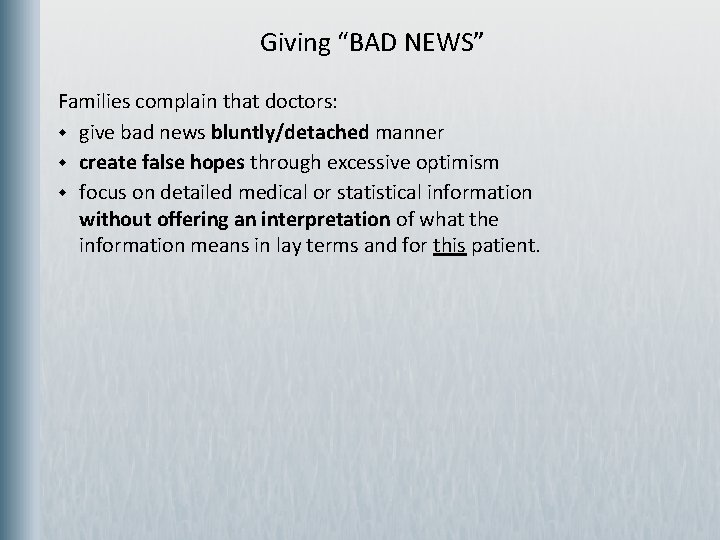

Giving “BAD NEWS” Families complain that doctors: w give bad news bluntly/detached manner w create false hopes through excessive optimism w focus on detailed medical or statistical information without offering an interpretation of what the information means in lay terms and for this patient.

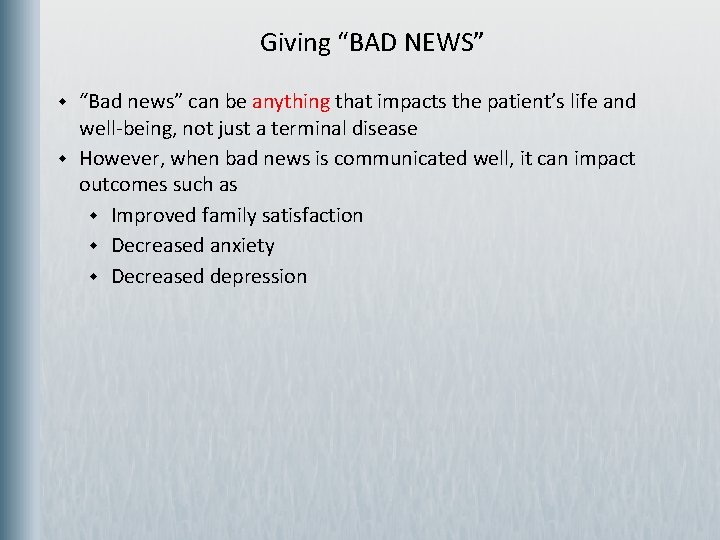

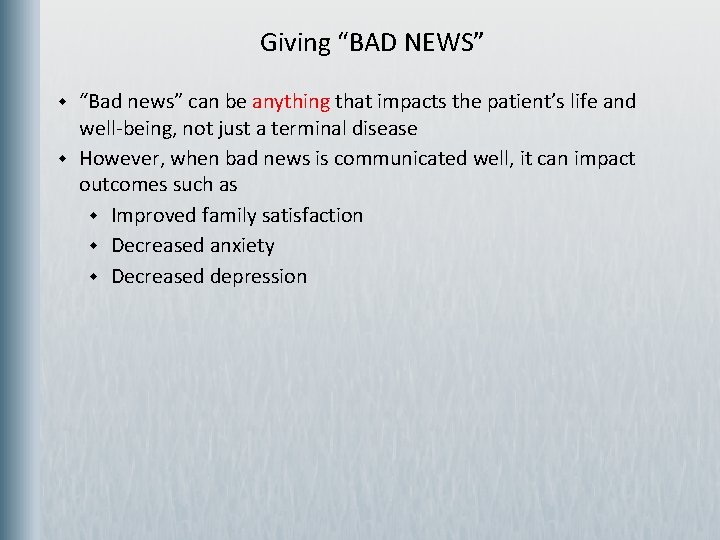

Giving “BAD NEWS” w w “Bad news” can be anything that impacts the patient’s life and well-being, not just a terminal disease However, when bad news is communicated well, it can impact outcomes such as w Improved family satisfaction w Decreased anxiety w Decreased depression

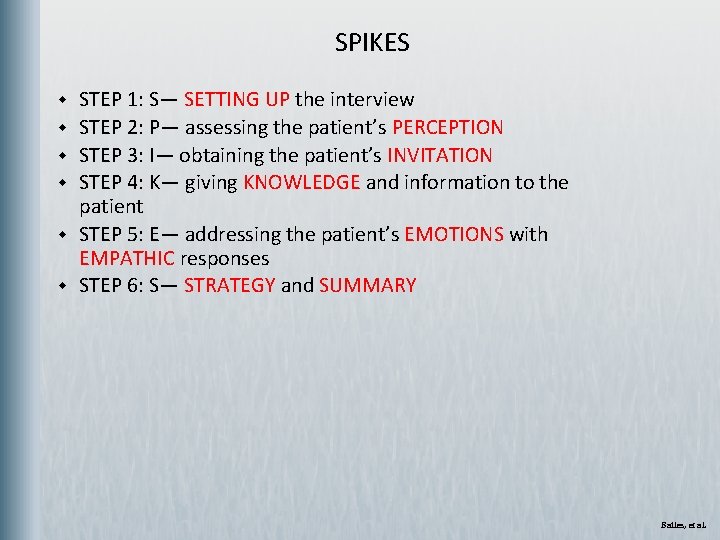

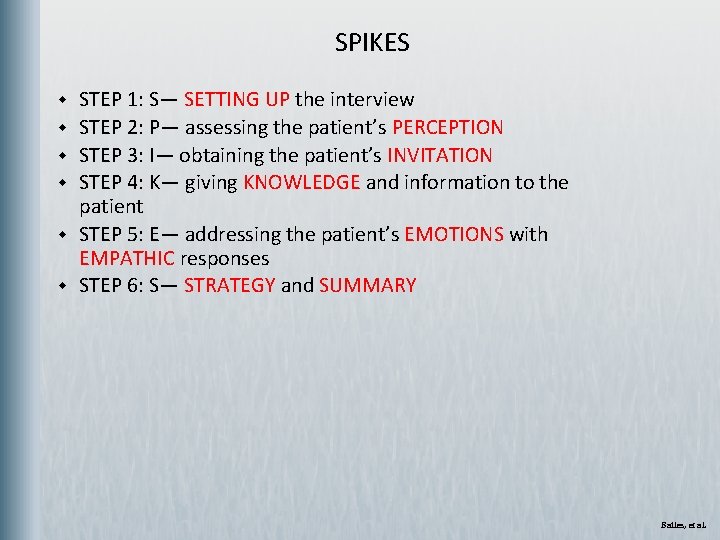

SPIKES w w w STEP 1: S— SETTING UP the interview STEP 2: P— assessing the patient’s PERCEPTION STEP 3: I— obtaining the patient’s INVITATION STEP 4: K— giving KNOWLEDGE and information to the patient STEP 5: E— addressing the patient’s EMOTIONS with EMPATHIC responses STEP 6: S— STRATEGY and SUMMARY Bailes, et al.

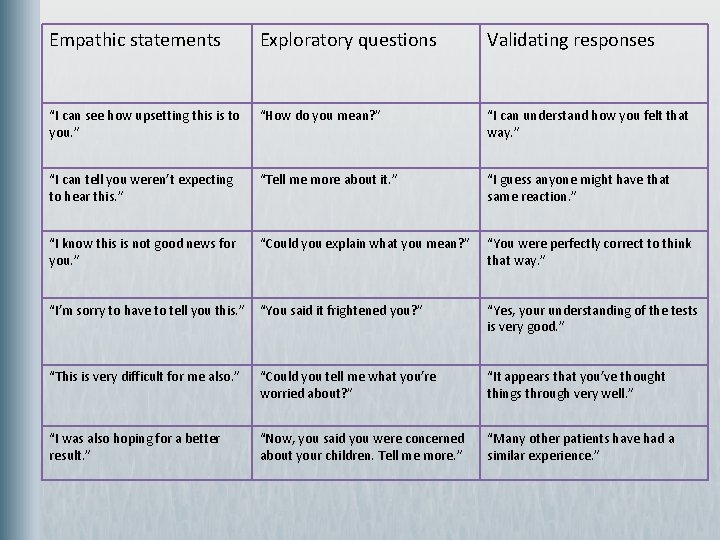

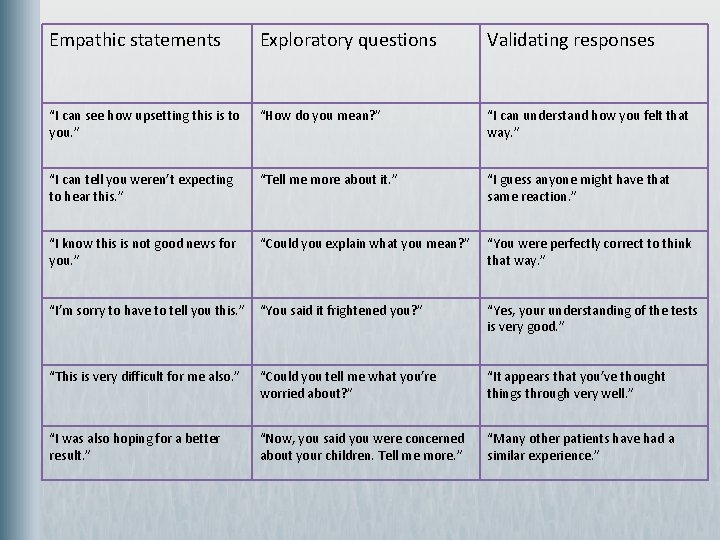

Empathic statements Exploratory questions Validating responses “I can see how upsetting this is to you. ” “How do you mean? ” “I can understand how you felt that way. ” “I can tell you weren’t expecting to hear this. ” “Tell me more about it. ” “I guess anyone might have that same reaction. ” “I know this is not good news for you. ” “Could you explain what you mean? ” “You were perfectly correct to think that way. ” “I’m sorry to have to tell you this. ” “You said it frightened you? ” “Yes, your understanding of the tests is very good. ” “This is very difficult for me also. ” “Could you tell me what you’re worried about? ” “It appears that you’ve thought things through very well. ” “I was also hoping for a better result. ” “Now, you said you were concerned about your children. Tell me more. ” “Many other patients have had a similar experience. ”

There is nothing like a great NURSE! Attending to the family's emotions (NURSE): w Name the emotion. "I know this is not what you wanted to hear. It must be overwhelming. ” w Understand the emotion. "I can see how difficult this is for you. ” w Respect the participants. "Given all that has happened, I respect how hard you're trying to do what your dad would have wanted. ” w Support the participants. "I will come back tomorrow. I'm sure you have questions, so please write them down so that we can go over each one of them. ” w Explore possibilities. "Tell me a little more about what you are thinking. ” Tulsky et al.

Setting Goals of Care Palliative docs have more difficult “difficult conversations: ” w Like an intensivist, may not have a pre-existing relationship with patient & family w Perceived need to make decisions on accelerated schedule (hours to days) w Patient often is incompetent, use of SDMs w Hard for family members to understand why the current treatments cannot achieve their goals (“got better the last time”) w A decision to shift goals and focus on comfort means that the patient may die relatively quickly, which raises the stakes of the loss and makes it harder for the family to think of other things to hope for, exacerbating their sense of loss and guilt and increasing the emotional cost of the transition.

Recommended Procedures for GOC Setting: w w w Identify the legal surrogate decision maker and how the family wants to make decisions. When talking to surrogates assess their knowledge and then provide information about the current medical information: The SPIKES technique Ask key questions to elicit the patient’s values Ask about how the surrogates are doing Suggest a course of action Sometimes given the patient’s goals, try a time-limited treatment trial

Time-Limited Trials CLEARLY tell them: 1. what the treatment is 2. the goals that you are looking for the treatment to achieve 3. what you will be looking for to determine whether those goals are being achieved 4. over what period of time to see if the treatment “works or not. ”

Talking About Prognosis w w Explain how you came up with the prognostic estimation. Some experts also recommend describing both the probability of death as well as the probability of survival to improve understanding.

Talking About Prognosis w w Explain the uncertainty that is inherent in all prognostication. Let the family know you are watching closely and will meet with them again to discuss any changes in the patient’s condition.

Talking About Prognosis: Example “This is the average survival time. Some people do better than average, some do worse. We will work together to try to beat the odds, but I will be there with you whatever happens. ”

Pearls: Ideas to Facilitate Conversations about Transitions 1. Invite the conversation: Do not force your agenda. 2. Respond to emotion, especially hope 3. Respond to guilt and feelings of responsibility 4. Reaffirm your commitment to the patient/family 5. Give the family some time to think about what you said 6. Praise the patient and family for their work up to this point

Interprofessional Communication w w Lacking in the literature. (boo!) Has focused on ICU Physician leadership and “communication openness” have been cited as necessary for other professionals to feel their ideas matter and impact goals of care discussions. Crucial for improving quality and safety of medical care. 1. Reader, T. , Flin, R. , Mearns, K. , & Cuthbertson, B. (2007). Interdisciplinary communication in the Intensive Care Unit. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 98, 347 -352 2. Anon. article reviewed for JPM, publishing pending.

Back to the Business Lit… What makes a great team? 1. Make time for team members to appreciate each other's skills 2. Surface and manage emotional issues that can help or hinder the team's progress 3. Celebrate team success Sound familiar? Harvard Business Review http: //blogs. hbr. org/hmu/2008/02/make-your-good-team-great-1. html, Accessed November 2011

Family Satisfaction w w w Increased proportion of time that family members talk (as compared to physicians) is associated with higher satisfaction ratings Three empathic behaviors are associated with satisfaction: w Assurances that the patient will not be abandoned before death w Assurances that the patient will be comfortable and will not suffer w Support for family's decisions about EOL care RULE OF THUMB: If you’re talking ½ the time, you’re talking TOO MUCH! w Allow people time to process information and ask questions.

VALUE Statements w w w V = Value and appreciate what the family said A = Acknowledge the family’s emotions L = Listen to the family’s description of the patient and U = Understand the patient as a person E = Elicit and ask questions of the family Mularski, et al.

VALUE Statements w w RCT of 126 critically ill patients cared for in 22 ICUs 95% of family members in the VALUE group reported that they had been able to express their emotions to the ICU clinicians, as compared to 75% of family members in the customary practice group. In addition, among family members who initially disagreed with the decision to forgo life-sustaining treatments, those in the VALUE group were more likely to concur with the decision at a later time. Finally, 90 days after the family meeting, VALUE group had less anxiety and depressive symptoms than those in the control group. Mularski, et al.

Six Types of Physician Communicators 1. The inexperienced messenger 2. The emotionally burdened 3. The rough and ready expert 4. The benevolent but tactless expert 5. The “distanced” doctor 6. The empathic professional

Talking about Resuscitation Preferences w w w CPR is symbolically important for both providers and patients. Doctors have strong feelings about performing CPR in patients who they think have a poor prognosis, as it evokes feelings of mutilating bodies. Conversely, families view CPR as the only thing that can stave off their loved one’s death. They overestimate CPR’s success and overemphasize its life prolonging effect and thus demand that physicians try.

Considerations in Discussions about Resuscitation Preferences What people care about regarding CPR: w The patient’s pre-CPR quality of life: if a patient was not happy with his/her QOL before CPR, s/he is unlikely to be happy with it after CPR. w The patient’s post-CPR quality of life: In studies, most patients do not want CPR if after CPR they will not be sentient. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to know the data about CPR outcomes for different populations. w The probability of the CPR “working”: Studies show that patients are likely to overestimate CPR’s success rate.

Considerations in Discussions about Resuscitation Preferences w w Studies have shown that when educated about CPR success rates, over 50% of patients changed their mind about whether they would want it. Patient’s shown videos of CPR made those decisions more stable over time and increased even more the rate of DNR orders.

Considerations in Discussions about Resuscitation Preferences w w Symbolically, CPR means life. Not doing CPR means the patient is going to die. Raising the issue of CPR may make the patient’s dying more real for the family, leading to an emotional reaction. Empathy, rather than giving facts, is most likely to help the family cope with this information.

Considerations in Discussions about Resuscitation Preferences w w You do not need to ask patients about every component of CPR or ACLS: purpose of discussing CPR is to make sure that decisions reflect and promote patient’s goals. Therapeutic decisions are typically viewed in a hierarchical fashion from aggressive (CPR or mechanical ventilation) to less aggressive (IV medications in the hospital) to even less aggressive (oral medications at home). w If patients or surrogates want to forgo ventilation, you probably do not have to ask about CPR. It almost surely does not make sense, and you can tell them that given their goals, CPR would not make sense, and you would not do it. Not true in reverse.

Considerations in Discussions about Resuscitation Preferences w w w Make a recommendation Once you understand the patient’s values and goals, make a recommendation regarding what you think should and should not be done. w The key here is to spend as much time talking about what you WILL do to achieve the patient’s goals as what you think should not be done Recognize that your recommendation may lead to negative reaction. w Instead, try to hear the request for “everything” as a distress signal that requires more exploration. w Reluctance to face painful emotions connected with the patient’s loss of health and potential impending death, preferring instead to keep hope alive by avoiding any such discussion.

Indications for a Family Conference w w When a course of treatment needs to be changed When the patient cannot participate When the medical situation is rapidly changing When family members disagree about the course of treatment

What Makes Family Meetings Hard? 1. Families bring complicated relationships and interactions to the meeting. 2. Family members w Have their own motivations and interests, w Have their own personal emotional needs, w Have different preferences for information or decision making, and w May disagree about the right course of action.

Conducting a Family Conference 1. Prepare for the conference (participants, room with privacy, clear purpose from all teams together, phones on vibrate) 2. Introduce everyone present and the purpose of the meeting 3. Assess what the family knows and expects (Ask-tell-Ask) 4. Describe the clinical situation (Ask-Tell-Ask) 5. Ask the family for questions and concerns (Ask-Tell-Ask and NURSE) 6. Allow silence 7. Propose goals for the patient’s care, and be prepared to negotiate 8. Provide a concrete follow-up plan 9. Summarize decisions 10. Document the family meeting in the chart Modified from EPERC Fast Fact # 16 http: //www. eperc. mcw. edu/fast. Fact/ff_16. htm

Documentation w w w w Who was there What was discussed What the family said about the patient’s goals What treatment plan was decided on What outcomes will be used to determine the plans success When the next meeting is Whethere was disagreement among the family Any strong emotions that were expressed w “Just the facts, ma’am. ” w DO NOT EDITORIALIZE in the medical record!

Watch Your Language!!! w Guilt and the fear of abandonment are particularly common in family meetings. w American culture stresses doing, and thus the default for many families is to want to do more to try to improve their loved ones health.

Watch Your Language!!! w Asking people if they want to be “aggressive” or “do everything” intimates that choosing comfort care is “giving up. ” w Similarly talking about withdrawing “care” or “stopping life supports” may feel like talking about abandoning their loved one. w Remind them of everything you WILL DO: IVF, Abx, Comfort, Hygiene…

Major Challenges to Discussions of Limiting Life-Sustaining Treatment w w w Families may perceive the decision to forgo LST as the cause of death, with accompanying burdens of responsibility and guilt. Families may fear that limitation of LST will be accompanied by intractable suffering including severe pain or dyspnea. There is a fear that limiting LST raises ethical or legal concerns. Teachings of certain religions may be interpreted as prohibiting decisions to limit LST. Death is uncertain, and its timing is unpredictable after withdrawal of treatments that were initiated to sustain life.

Withdrawal of LST w w w The median time to death from the first decision to limit therapy is approximately 15 hours in ICU patients. Following the decision to limit the most active form of therapy, the median time to death if therapy is withheld is 14. 3 hours and 4. 0 hours if therapy is withdrawn. 11% of patients survive to discharge.

Discussing What Happens After a Decision to Forgo Life-Sustaining Treatments w w Talk about the Timing of Forgoing LST Attend to the family’s social and religious needs w people who would like to say good-bye. w how to talk to children about the patient’s death w any religious or spiritual traditions w preferences regarding whether they want to be present during the withdrawal Describe the Process of Discontinuing LST and Dying Summarize and Ask for Questions:

Navigating Conflict with Families Address common patterns of conflict between the family and the health care team: w The family is acting out of guilt or fear of being responsible for a decision that will shorten the life of the patient. w The family does not trust the health care team. w The family is hoping for a miracle.

Is it YOU? ? ? Consider ineffective or dysfunctional communication by health care providers as a primary cause of the family’s misunderstanding. w w w Attend to your own responses to the family. How do poor patient outcomes affect you? Calibrate your own practice style. Is a dispute over life support a power struggle, a matter of resource allocation or an issue of conscience? Be aware that clinicians have issues too. Consider that the health care team’s internal disagreements may be contributing to the problem.

Discussing “medically inappropriate treatments” w w w Be rigorously honest about the limits of your own ability to predict the future. Always ask yourself whether a dispute about limiting LST is about resource allocation, the goals of medicine, or a power struggle about who gets to decide, rather than an issue of prognostication. Make the assumption that the family's intentions are also to provide the best care for the patient. Emphasize that you hope the patient will improve, even if your medical judgment is that such improvement is extremely unlikely. Ask if there is anything you can do to help the family.

Pitfalls: Common Barriers to Good Communication w w Making assumptions about what the family knows and doesn’t know Ignoring the context of the communication encounter Launching into your agenda first without negotiating the focus of the interview Giving pathophysiology lectures

Pitfalls: Common Barriers to Good Communication w w w Talking about procedures like CPR before discussing the big picture of disease status, patient values, patient and family wishes Addressing withdrawal or withholding of life-support with the family without first assessing their understanding of their loved one’s medical condition Focusing on interventions without trying to understand the patient’s preferences or rationale

Pitfalls: Common Barriers to Good Communication w w w Not finding out the family’s information needs and styles Pushing the family to make a decision, before they have had a chance to grieve the loss Don’t ask the family what they want to do… w Rather ask what is in the best interest of the patient or what the patient would want them to do

Pitfalls: Common Barriers to Good Communication w w w Expecting families to make a decision in the 1 st discussion Trying to explore goals and future decisions at the same time you are giving bad news Forcing families to talk about the future or Resuscitation preferences when they are not ready

Pitfalls: Common Barriers to Good Communication w w w Overlooking the stress of caregiving. Over-focusing on the single legal surrogate decision-maker. Focusing solely on what you are not going to do

Pitfalls: Common Barriers to Good Communication w w Expressing frustration with a family that makes a thoughtful choice about LST that diverges from your recommendation Don’t try to convince the family that their decision is unreasonable. Responding to family distress by reflexively offering more aggressive ICU care Offering reassurance prematurely w It is not always “going to be okay. ”

Pitfalls: Common Barriers to Good Communication w w w Ignoring emotions Ignoring your own feelings Watch yourself for distancing behaviors

Pitfalls: Common Barriers to Good Communication w w w Feeling you are responsible for maintaining the patient’s hope Feeling that after the family decides to forgo LST that your job is done Talking too much

Pearls: Ideas to Facilitate Giving Bad News w w w Attend to affect and provide opportunities for patients/families to talk about their values. Avoid vague terms—and when you hear the family use them ask them to define them. Ask the family about their questions and concerns at several points during key discussions.

Pearls: Ideas to Facilitate Giving Bad News w w w Eliciting the patient and/or family’s concerns can help them feel heard and help you address their primary worries. Family members may have different needs Ensure shared understanding of the goals of care by asking “why” when patients/families ask for specific treatments or express their goals.

Pearls: Ideas to Facilitate Giving Bad News w w w Attend to the emotions underlying the questions and reassure them that you will provide information about prognosis so they don’t think you’re being evasive. Be aware of your own emotions such as sadness, guilt, disappointment, or shame. Try to accept that being empathic, interested, and affirming are powerful verbal techniques that the patient and/or family recognize as demonstrations of your support.

Pearls: Ideas to Facilitate Giving Bad News w w You can help your patient and/or family members: w Hope for the best. w Prepare for the worst. w Attend to the present. Express non-abandonment Express support for the family’s decisions Remember that you are offering to let people talk about this issue, not forcing them to “give up. ”

Helpful Phrases In evaluating misunderstanding: w “Tell me what others are telling you about what is going on with your dad? ” w “I want to make sure that we are on the same page. Can you please take a minute to tell me what you understand is going on with your dad. "

Helpful Phrases Dealing with denial w "I can sense how much you were hoping for good news. ” w "I wish things would have worked out differently. ” w "This must be devastating for you. ” w Dealing with “miracles” w "Can you tell me more about what a miracle would look like for you? ” w “Besides a miraculous cure, are there other things you are hoping for? ”

Helpful Phrases Dealing with guilt w "I am not asking you to make a medical decision. I want you to help me understand what your dad would have said if he were sitting here and could understand what we have been talking about. ” w "I can see how hard this is for you. I respect that you’re trying to follow your dad's wishes even though you would want something different for yourself. ” w "I would never ask a family to give up on a patient or loved one. Sometimes, however, love and respect require that we let someone go. ”

Can We Talk? w w w Think of clinical examples of times when a patient and family have had difficulty making a treatment decision. Think about a time you participated in a family conference to discuss treatment decisions that was less than ideal… and an effective one. What are some of the difficulties encountered when working with patients and their families?

Additional References w w http: //www. eperc. mcw. edu/EPERC/Fast. Factsand. Concepts Back AL, Arnold RM, Quill TE. Hope for the Best, and Prepare for the Worst. Ann Intern Med 2003; 138(5): 439443. Quill TE, Arnold RM, Platt F. “I Wish Things Were Different”: Expressing Wishes in Response to Loss, Futility, and Unrealistic Hopes. Ann Intern Med 2001; 135(7): 551 -555. Quill TE, Arnold R, Back AL. Discussing Treatment Preferences With Patients Who Want “Everything”. Ann Intern Med. 2009; 151: 345 -349.

Credits Photographs use for the cover are allowed by the morgue. File free photo agreement and the Royalty Free usage agreement at Stock. xchng. They appear on the cover in this order: Wallyir at morguefile. com/archive/display/221205 Mokra at www. sxc. hu/photo/572286 Clarita at morguefile. com/archive/display/33743 Microsoft Powerpoint Images and Clipart: Slides: 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 14, 29, 34, 35, 41, 44, 53, 68 Images from The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Multimedia Scriptorium: Slides: 10, 12

Sanctifying grace

Sanctifying grace With shouts of grace grace to it

With shouts of grace grace to it Once in grace always in grace

Once in grace always in grace Medida de varas

Medida de varas Excavacion papilar aumentada

Excavacion papilar aumentada Varas verdes

Varas verdes 20 varas de lienzo

20 varas de lienzo Equilibrio puerto varas

Equilibrio puerto varas Altas cumbres puerto varas

Altas cumbres puerto varas Altas cumbres puerto varas

Altas cumbres puerto varas Dra alejandra varas

Dra alejandra varas Altas cumbres puerto varas

Altas cumbres puerto varas Varas feiten

Varas feiten Pistola haga forestal

Pistola haga forestal Alejandra varas oftalmologa

Alejandra varas oftalmologa 369 times 2

369 times 2 Syntehtic division

Syntehtic division Long division vocabulary

Long division vocabulary Long division of polynomials

Long division of polynomials Tung shin hospital chinese medical division

Tung shin hospital chinese medical division California medical license application

California medical license application Gbmc medical records

Gbmc medical records Difference between medical report and medical certificate

Difference between medical report and medical certificate Torrance memorial map

Torrance memorial map Cartersville medical center medical records

Cartersville medical center medical records Chickasaw nation health insurance

Chickasaw nation health insurance Hpd mental health division

Hpd mental health division Merck human health division

Merck human health division Tennessee division of radiological health

Tennessee division of radiological health Types of commmunication

Types of commmunication Umd capital region health

Umd capital region health Population health 101

Population health 101 一生爱你

一生爱你 When your hero falls tupac

When your hero falls tupac Flvs grace period

Flvs grace period Grace binion

Grace binion Circe the grace of the witch summary

Circe the grace of the witch summary Pilgrimage of grace banner

Pilgrimage of grace banner Book 10 circe the grace of the witch

Book 10 circe the grace of the witch Augustus waters death

Augustus waters death Irresistible grace refuted

Irresistible grace refuted Sublime gracia amazing grace español

Sublime gracia amazing grace español Prof. grace schneider

Prof. grace schneider Charles goodyear soccer ball

Charles goodyear soccer ball Grace aviles

Grace aviles A dug a dug by bill keys

A dug a dug by bill keys I am a parrot grace nichols

I am a parrot grace nichols Kairos obstacles talk

Kairos obstacles talk Grace brulotte

Grace brulotte Marvelous grace of our loving lord

Marvelous grace of our loving lord Amy sand clay music

Amy sand clay music Marbury v madison summary

Marbury v madison summary Grace amin

Grace amin Unmerited favor meaning

Unmerited favor meaning Island man grace nichols

Island man grace nichols Surah al ain

Surah al ain Wherever i hang grace nichols

Wherever i hang grace nichols Grace happer

Grace happer Grace fellowship manchester

Grace fellowship manchester Grace paton

Grace paton What is a constructive feedback

What is a constructive feedback Grace vermeulen

Grace vermeulen How does music affect heart rate

How does music affect heart rate Justice for grace holland

Justice for grace holland Covenant of grace presbyterian church

Covenant of grace presbyterian church Philmont itineraries

Philmont itineraries Irresistable grace

Irresistable grace Prevenient grace

Prevenient grace Mary grace slattery

Mary grace slattery My chains are broken i've been set free

My chains are broken i've been set free Robert burns nationality

Robert burns nationality