Measuring Personal Religious Experience William Langston Iska Frosh

- Slides: 1

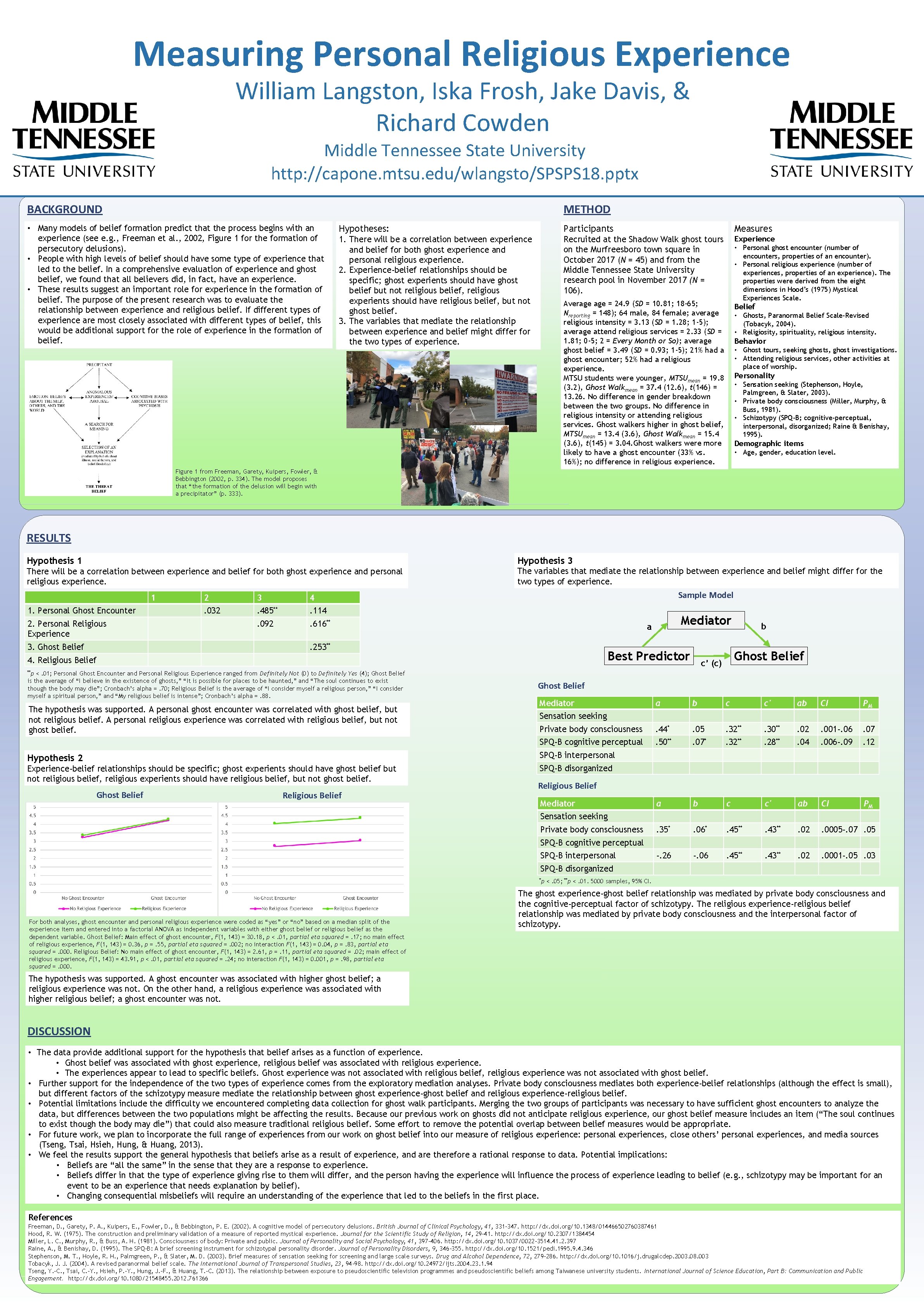

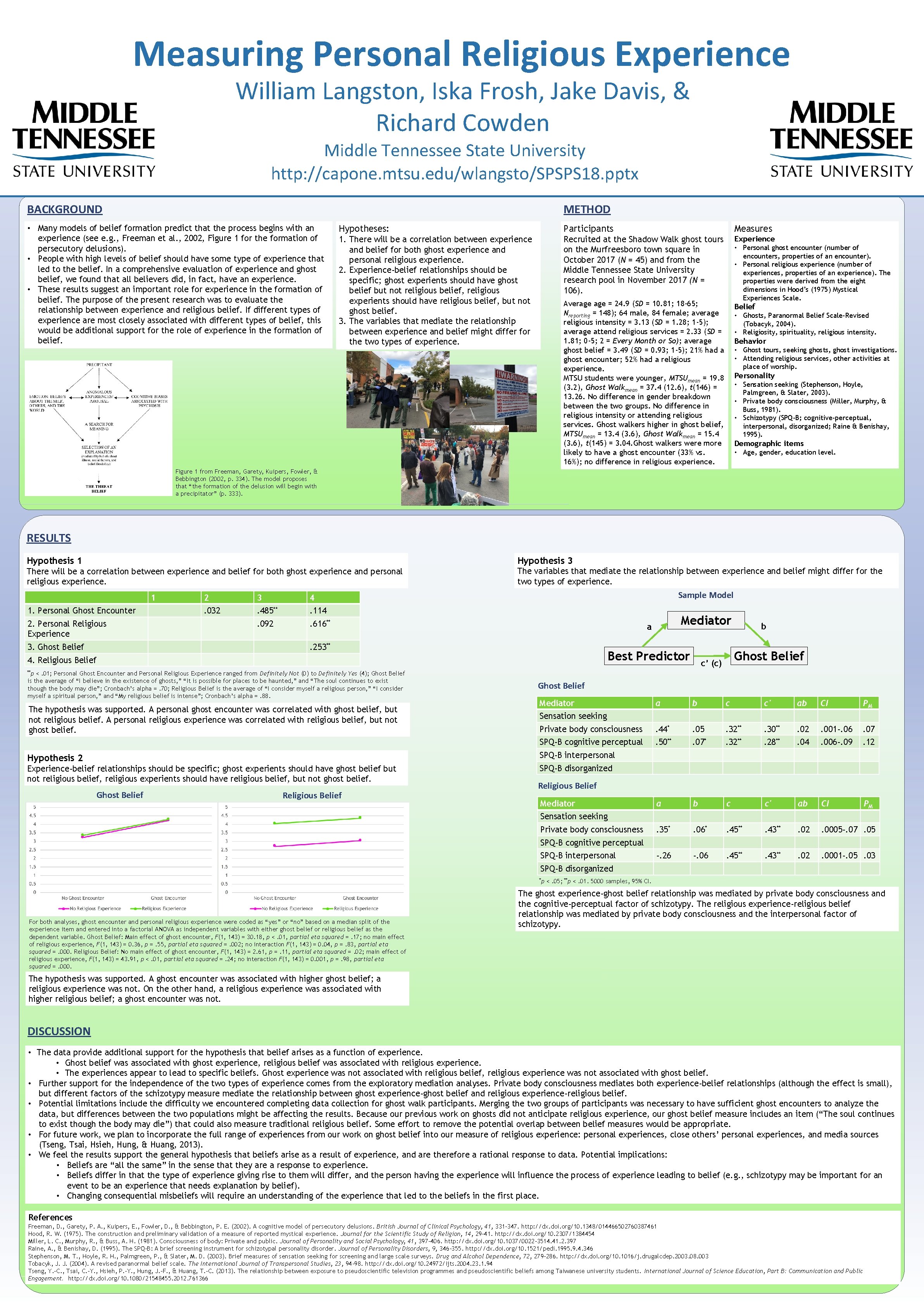

Measuring Personal Religious Experience William Langston, Iska Frosh, Jake Davis, & Richard Cowden Middle Tennessee State University http: //capone. mtsu. edu/wlangsto/SPSPS 18. pptx METHOD BACKGROUND • Many models of belief formation predict that the process begins with an experience (see e. g. , Freeman et al. , 2002, Figure 1 for the formation of persecutory delusions). • People with high levels of belief should have some type of experience that led to the belief. In a comprehensive evaluation of experience and ghost belief, we found that all believers did, in fact, have an experience. • These results suggest an important role for experience in the formation of belief. The purpose of the present research was to evaluate the relationship between experience and religious belief. If different types of experience are most closely associated with different types of belief, this would be additional support for the role of experience in the formation of belief. Hypotheses: Participants Measures 1. There will be a correlation between experience and belief for both ghost experience and personal religious experience. 2. Experience-belief relationships should be specific; ghost experients should have ghost belief but not religious belief, religious experients should have religious belief, but not ghost belief. 3. The variables that mediate the relationship between experience and belief might differ for the two types of experience. Recruited at the Shadow Walk ghost tours on the Murfreesboro town square in October 2017 (N = 45) and from the Middle Tennessee State University research pool in November 2017 (N = 106). Experience Average = 24. 9 (SD = 10. 81; 18 -65; Nreporting = 148); 64 male, 84 female; average religious intensity = 3. 13 (SD = 1. 28; 1 -5); average attend religious services = 2. 33 (SD = 1. 81; 0 -5; 2 = Every Month or So); average ghost belief = 3. 49 (SD = 0. 93; 1 -5); 21% had a ghost encounter; 52% had a religious experience. MTSU students were younger, MTSUmean = 19. 8 (3. 2), Ghost Walkmean = 37. 4 (12. 6), t(146) = 13. 26. No difference in gender breakdown between the two groups. No difference in religious intensity or attending religious services. Ghost walkers higher in ghost belief, MTSUmean = 13. 4 (3. 6), Ghost Walkmean = 15. 4 (3. 6), t(145) = 3. 04. Ghost walkers were more likely to have a ghost encounter (33% vs. 16%); no difference in religious experience. Belief • Personal ghost encounter (number of encounters, properties of an encounter). • Personal religious experience (number of experiences, properties of an experience). The properties were derived from the eight dimensions in Hood’s (1975) Mystical Experiences Scale. • Ghosts, Paranormal Belief Scale-Revised (Tobacyk, 2004). • Religiosity, spirituality, religious intensity. Behavior • Ghost tours, seeking ghosts, ghost investigations. • Attending religious services, other activities at place of worship. Personality • Sensation seeking (Stephenson, Hoyle, Palmgreen, & Slater, 2003). • Private body consciousness (Miller, Murphy, & Buss, 1981). • Schizotypy (SPQ-B; cognitive-perceptual, interpersonal, disorganized; Raine & Benishay, 1995). Demographic items • Age, gender, education level. Figure 1 from Freeman, Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, & Bebbington (2002, p. 334). The model proposes that “the formation of the delusion will begin with a precipitator” (p. 333). RESULTS Hypothesis 1 Hypothesis 3 There will be a correlation between experience and belief for both ghost experience and personal religious experience. The variables that mediate the relationship between experience and belief might differ for the two types of experience. 1 1. Personal Ghost Encounter 2. Personal Religious Experience 3. Ghost Belief 2 3 4 . 032 . 485** . 114 . 092 . 616** Sample Model . 253** Best Predictor 4. Religious Belief <. 01; Personal Ghost Encounter and Personal Religious Experience ranged from Definitely Not (0) to Definitely Yes (4); Ghost Belief is the average of “I believe in the existence of ghosts, ” “It is possible for places to be haunted, ” and “The soul continues to exist though the body may die”; Cronbach’s alpha =. 70; Religious Belief is the average of “I consider myself a religious person, ” “I consider myself a spiritual person, ” and “My religious belief is intense”; Cronbach’s alpha =. 88. Mediator a b Ghost Belief c’ (c) **p The hypothesis was supported. A personal ghost encounter was correlated with ghost belief, but not religious belief. A personal religious experience was correlated with religious belief, but not ghost belief. Ghost Belief Mediator a b c c' ab CI PM Private body consciousness . 44* . 05 . 32** . 30** . 02 . 001 -. 06 . 07 SPQ-B cognitive perceptual . 50** . 07* . 32** . 28** . 04 . 006 -. 09 . 12 a b c c' ab CI PM . 35* . 06* . 45** . 43** . 02 . 0005 -. 07. 05 -. 26 -. 06 . 45** . 43** . 02 . 0001 -. 05. 03 Sensation seeking SPQ-B interpersonal Hypothesis 2 Experience-belief relationships should be specific; ghost experients should have ghost belief but not religious belief, religious experients should have religious belief, but not ghost belief. Ghost Belief Religious Belief SPQ-B disorganized Religious Belief Mediator Sensation seeking Private body consciousness SPQ-B cognitive perceptual SPQ-B interpersonal SPQ-B disorganized *p For both analyses, ghost encounter and personal religious experience were coded as “yes” or “no” based on a median split of the experience item and entered into a factorial ANOVA as independent variables with either ghost belief or religious belief as the dependent variable. Ghost Belief: Main effect of ghost encounter, F(1, 143) = 30. 18, p <. 01, partial eta squared =. 17; no main effect of religious experience, F(1, 143) = 0. 36, p =. 55, partial eta squared =. 002; no interaction F(1, 143) = 0. 04, p =. 83, partial eta squared =. 000. Religious Belief: No main effect of ghost encounter, F(1, 143) = 2. 61, p =. 11, partial eta squared =. 02; main effect of religious experience, F(1, 143) = 43. 91, p <. 01, partial eta squared =. 24; no interaction F(1, 143) = 0. 001, p =. 98, partial eta squared =. 000. <. 05; **p <. 01. 5000 samples, 95% CI. The ghost experience-ghost belief relationship was mediated by private body consciousness and the cognitive-perceptual factor of schizotypy. The religious experience-religious belief relationship was mediated by private body consciousness and the interpersonal factor of schizotypy. The hypothesis was supported. A ghost encounter was associated with higher ghost belief; a religious experience was not. On the other hand, a religious experience was associated with higher religious belief; a ghost encounter was not. DISCUSSION • The data provide additional support for the hypothesis that belief arises as a function of experience. • Ghost belief was associated with ghost experience, religious belief was associated with religious experience. • The experiences appear to lead to specific beliefs. Ghost experience was not associated with religious belief, religious experience was not associated with ghost belief. • Further support for the independence of the two types of experience comes from the exploratory mediation analyses. Private body consciousness mediates both experience-belief relationships (although the effect is small), but different factors of the schizotypy measure mediate the relationship between ghost experience-ghost belief and religious experience-religious belief. • Potential limitations include the difficulty we encountered completing data collection for ghost walk participants. Merging the two groups of participants was necessary to have sufficient ghost encounters to analyze the data, but differences between the two populations might be affecting the results. Because our previous work on ghosts did not anticipate religious experience, our ghost belief measure includes an item (“The soul continues to exist though the body may die”) that could also measure traditional religious belief. Some effort to remove the potential overlap between belief measures would be appropriate. • For future work, we plan to incorporate the full range of experiences from our work on ghost belief into our measure of religious experience: personal experiences, close others’ personal experiences, and media sources (Tseng, Tsai, Hsieh, Hung, & Huang, 2013). • We feel the results support the general hypothesis that beliefs arise as a result of experience, and are therefore a rational response to data. Potential implications: • Beliefs are “all the same” in the sense that they are a response to experience. • Beliefs differ in that the type of experience giving rise to them will differ, and the person having the experience will influence the process of experience leading to belief (e. g. , schizotypy may be important for an event to be an experience that needs explanation by belief). • Changing consequential misbeliefs will require an understanding of the experience that led to the beliefs in the first place. References Freeman, D. , Garety, P. A. , Kuipers, E. , Fowler, D. , & Bebbington, P. E. (2002). A cognitive model of persecutory delusions. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 41, 331– 347. http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1348/014466502760387461 Hood, R. W. (1975). The construction and preliminary validation of a measure of reported mystical experience. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 14, 29 -41. http: //dx. doi. org/10. 2307/1384454 Miller, L. C. , Murphy, R. , & Buss, A. H. (1981). Consciousness of body: Private and public. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 397 -406. http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1037/0022 -3514. 41. 2. 397 Raine, A. , & Benishay, D. (1995). The SPQ-B: A brief screening instrument for schizotypal personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 9, 346 -355. http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1521/pedi. 1995. 9. 4. 346 Stephenson, M. T. , Hoyle, R. H. , Palmgreen, P. , & Slater, M. D. (2003). Brief measures of sensation seeking for screening and large scale surveys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 72, 279– 286. http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1016/j. drugalcdep. 2003. 08. 003 Tobacyk, J. J. (2004). A revised paranormal belief scale. The International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 23, 94 -98. http: //dx. doi. org/10. 24972/ijts. 2004. 23. 1. 94 Tseng, Y. -C. , Tsai, C. -Y. , Hsieh, P. -Y. , Hung, J. -F. , & Huang, T. -C. (2013). The relationship between exposure to pseudoscientific television programmes and pseudoscientific beliefs among Taiwanese university students. International Journal of Science Education, Part B: Communication and Public Engagement. http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1080/21548455. 2012. 761366