Meaning and Language Part 1 Plan We will

- Slides: 26

Meaning and Language Part 1

Plan • We will talk about two different types of meaning, corresponding to two different types of objects: – Lexical Semantics: Roughly, the meaning of individual words – Compositional Semantics: How larger objects (clauses, sentences) come to mean what they do. Relatedly, how formal logic can be used as a tool to study language • However: These two fit together, as discussed in the reading (Partee) • That is, aspects of what we want to say about what words mean will interact with what we say about larger structures • Today: – Some distinctions – Basic sets and truth conditions – Working towards logic for language

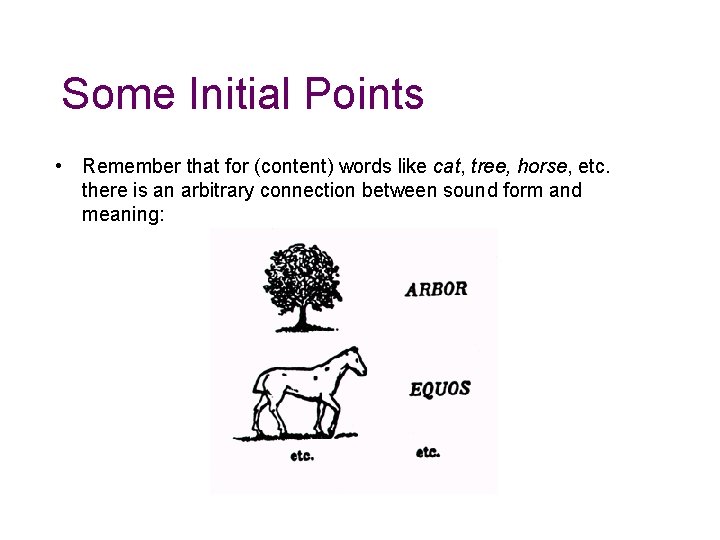

Some Initial Points • Remember that for (content) words like cat, tree, horse, etc. there is an arbitrary connection between sound form and meaning:

Sound and Meaning • This pairing of sound and meaning is one component of language – “arbitrary” component: stressed by de Saussure – “predictable” component: logic, etc. • Rock bottom: basic connections in small units (morphemes, words) between sound and meaning • The full range of things that we associate with human language is found only when such connections are part of a generative system for creating larger units from smaller ones, i. e. the syntax (remember last week)

Outline • Traditional distinctions for sound/meaning connections (homophony, polysemy) • Words and sets (as in set theory) • Basic cases (nouns and adjectives) • Wednesday: Using formal logic to model meaning relations in language

Some Distinctions • First: cases in which the “one to one” mapping between sound forms and meanings is not so direct. – Homophony: A cases in which two words have the same sound form, but distinct and unrelated meanings • Bank-1 ‘side of a river’ • Bank-2 ‘financial institution’

Representation • In any case, with homophony we are dealing with distinct words; that is: – Bank-1 is to Bank-2 as cat is to dog or bank-1 is to cat • This is equivalent to saying that in such cases, the identity in sound form is an accident • In other cases of the same sound form but differing meaning, this is not the case

Polysemy • We speak of polysemy ‘many meanings’ in cases in which we have the same word but with distinct yet related senses; one case: – Pool: water on the ground – Pool: swimming pool • In this case, there is no need to say that there are different words; perhaps really different senses of the same word

Polysemy, cont. • Sometimes with polysemy the intuition is that the word is basically ‘vague’, and that its fuller meanings are supplied by context • Something similar is found with verbs, where the context comes from the syntactic structure: – The whistle sirened lunch time. – The police car sirened the speeder to a stop. • Cases like this indicate that the basic meaning of words can be augmented with information from the syntactic structure – John shinned the ball. – Mary shinned the ball to John. – Etc. • The “core”meaning of the word shin or siren exists, but is augmented by what happens in the syntactic structure

Words and Sets • Let’s take an example of how we think of word meanings… • More interesting: how meanings of combinations of words are derived • We can think of the meaning of some words as relating to a system of categories, some more general, some more specific • This lends itself to representation in terms of sets • A set is, for our purposes, an abstract collection

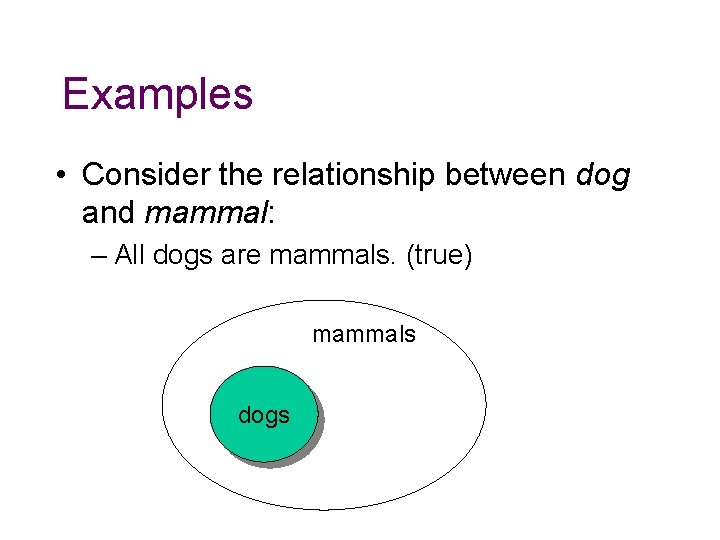

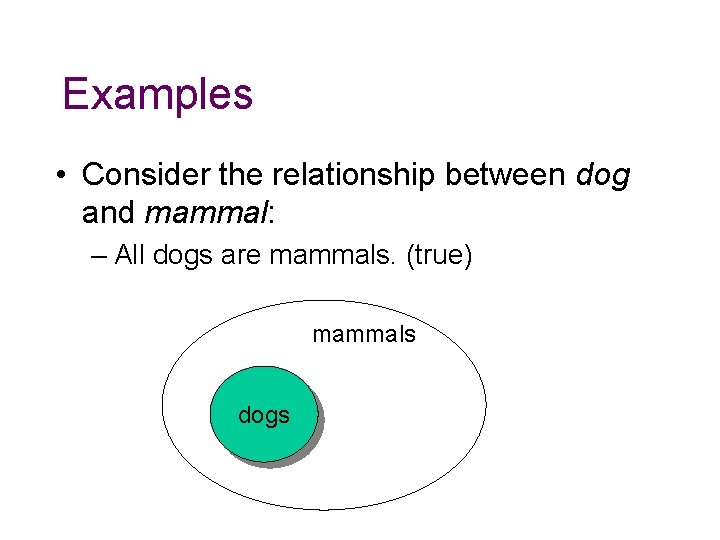

Examples • Consider the relationship between dog and mammal: – All dogs are mammals. (true) mammals dogs

Examples, cont. • The set relationship is one of inclusion; the set denoted by dog is a subset of the set denoted by mammal • Other relationships are possible as well, both in terms of ‘some’ and ‘no’ • We will formalize an extension to this in the next lecture

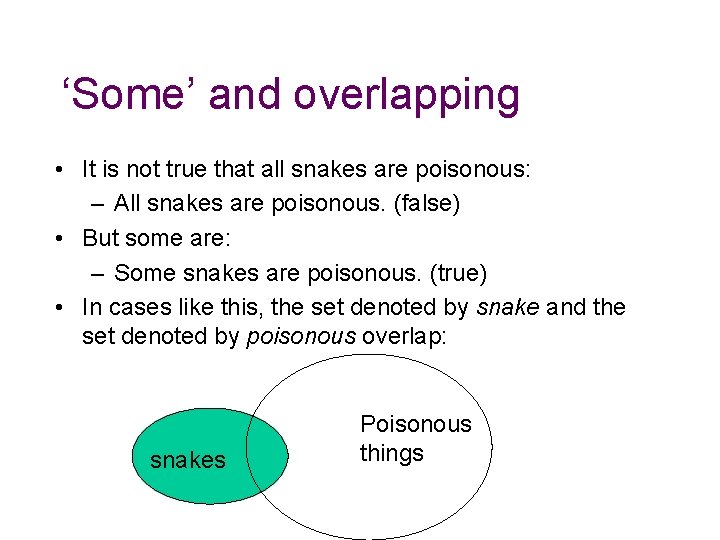

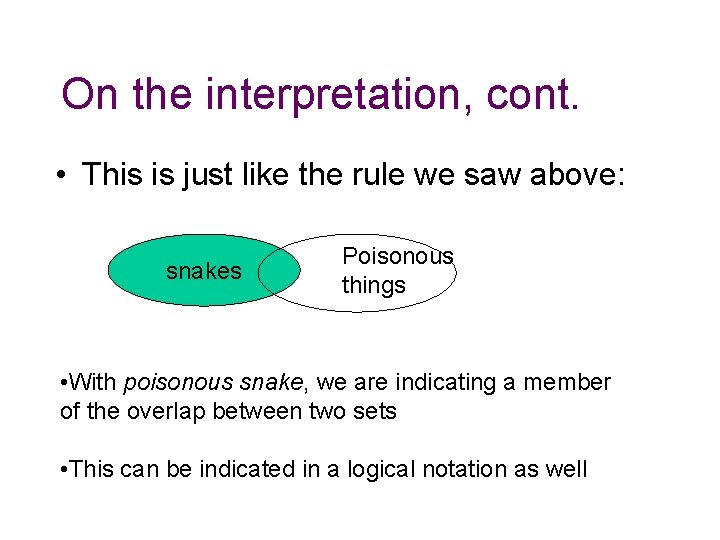

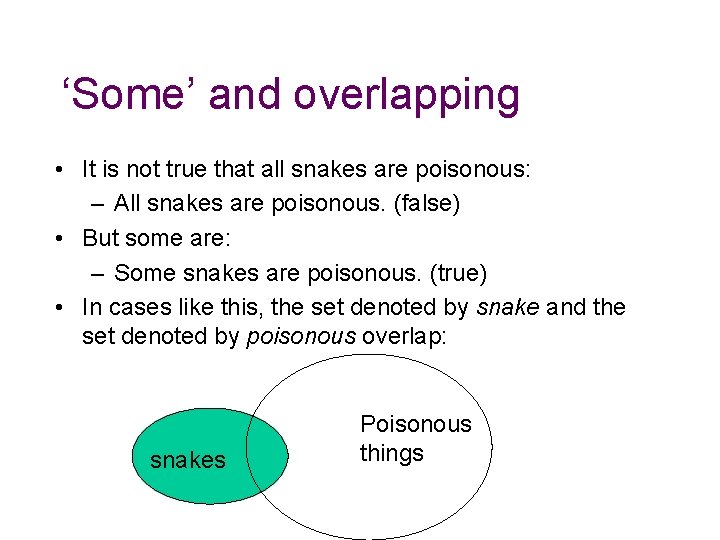

‘Some’ and overlapping • It is not true that all snakes are poisonous: – All snakes are poisonous. (false) • But some are: – Some snakes are poisonous. (true) • In cases like this, the set denoted by snake and the set denoted by poisonous overlap: snakes Poisonous things

Non-overlapping: ‘No’ • It can also be the case that sets do not overlap, in addition to overlapping in very small ways • Consider the following: – No mammals are poisonous. • Ok, we want to know what no means, but is this a good example (is it true)?

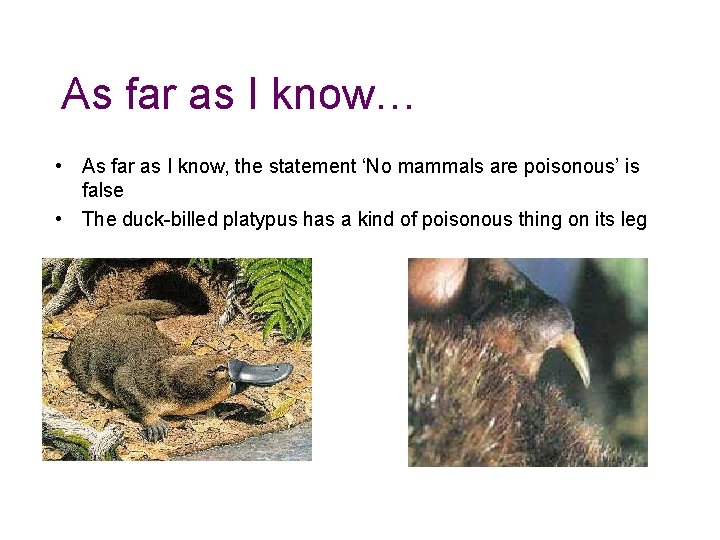

As far as I know… • As far as I know, the statement ‘No mammals are poisonous’ is false • The duck-billed platypus has a kind of poisonous thing on its leg

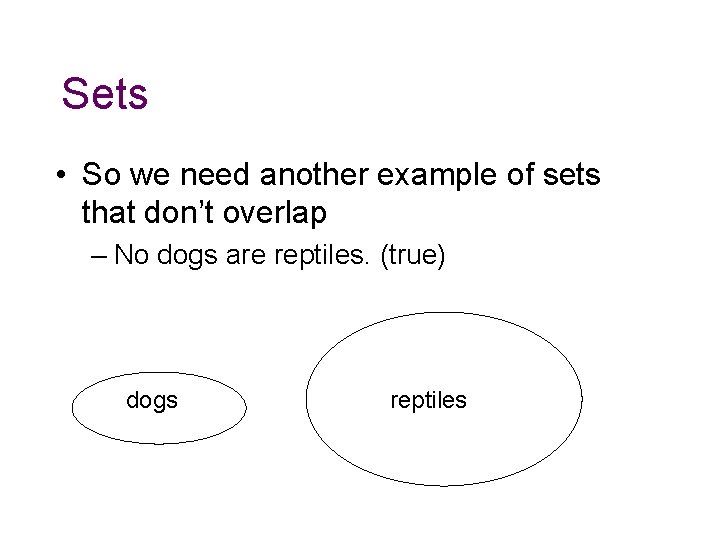

Sets • So we need another example of sets that don’t overlap – No dogs are reptiles. (true) dogs reptiles

Truth Conditions • One way of approaching meanings is to look at the truth conditions of sentences • The truth conditions specify in precise terms the circumstances that obtain in order for a sentence to be true (or false) • Specifying the truth conditions is a necessary component of the study of meaning; if we can show that two sentences are true under different conditions, then we would like to say that they have different meanings

Some examples • Sometimes it seems like the specification of truth conditions is trivial: – The cat is on the mat. – The dog is on the mat. – Different truth conditions • But what about more complex cases? Consider: – The glass is half full. – The glass is half empty.

The ‘Glass’ Example • On the face of it, ‘half full’ and ‘half empty’ seem to have the same truth conditions. • But: Consider the following examples: – The glass is almost half full. (e. g. 48%) – The glass is almost half empty. (e. g. 53%) • These have different truth conditions – Assuming that ‘almost’ is the same in the two sentences, it must be the case that ‘half full’ and ‘half empty’ actually have different meanings – If these two phrases were not different in meaning, where else could the difference come from? ?

Other fractions • As a further point, consider what happens when we replace ‘half’ by other fractions: – The glass is three eighths full. – The glass is three eighths empty. • These do not mean the same thing • It looks as if ‘half full’ and ‘half empty’ mean different things, but sometimes can be true under the same circumstances

More on Adjectives • Some further cases from the study of adjectives illustrate – The relevance of our use of sets above – The interaction of lexical meaning with compositional meaning • Let’s take another simple example: – poisonous snake

Interpreting poisonous snake • One way of thinking of the adjective meaning with respect to the noun follows on what we were doing above • What we would like are some general rules that tell us how to interpret certain syntactic objects in terms of the semantics we are using • Rule (informal): When an adjective A modifies a noun N ([A N]), the interpretation of this object is the set defined by the intersection of A’s meaning with N’s meaning

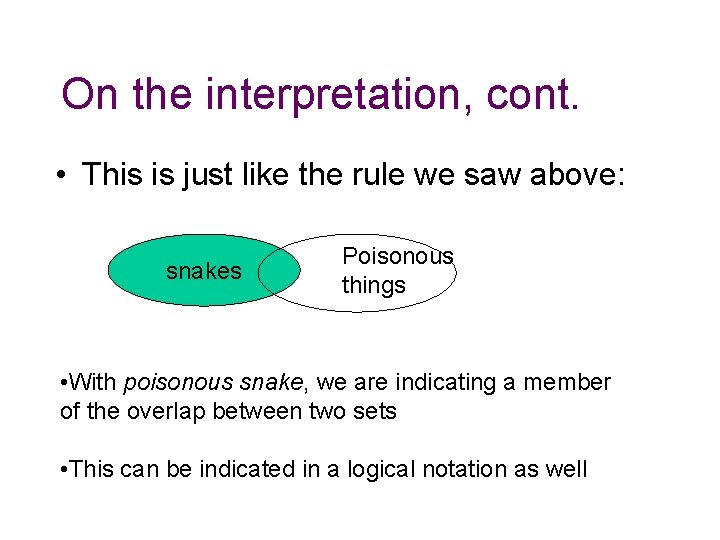

On the interpretation, cont. • This is just like the rule we saw above: snakes Poisonous things • With poisonous snake, we are indicating a member of the overlap between two sets • This can be indicated in a logical notation as well

Some notation • We need a notation for sets and their interaction – || X || = the set of things denoted by property X • Example: || red || = the set of red things • This can also be written as {x| x is red}, read as ‘the set of all things x such that x is red’ – What about how adjectives and nouns combine by the reasoning above? • We need notation for ‘and’; why? Because things that are poisonous snakes are the set of things that are (1) poisonous AND (2) snakes

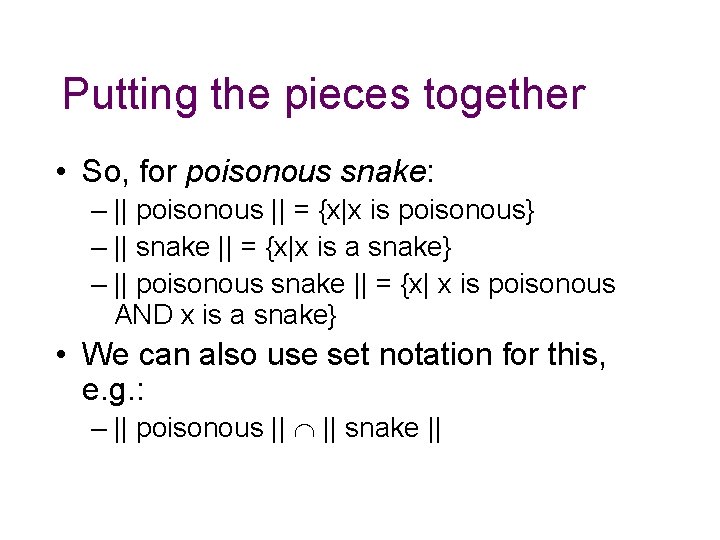

Putting the pieces together • So, for poisonous snake: – || poisonous || = {x|x is poisonous} – || snake || = {x|x is a snake} – || poisonous snake || = {x| x is poisonous AND x is a snake} • We can also use set notation for this, e. g. : – || poisonous || snake ||

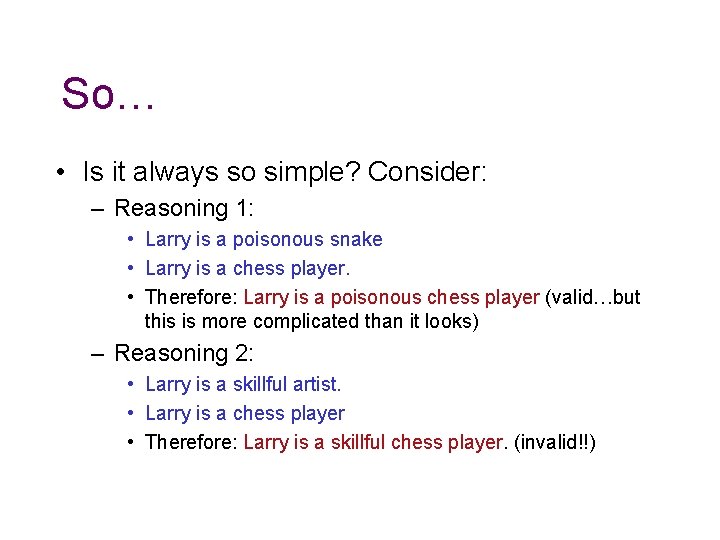

So… • Is it always so simple? Consider: – Reasoning 1: • Larry is a poisonous snake • Larry is a chess player. • Therefore: Larry is a poisonous chess player (valid…but this is more complicated than it looks) – Reasoning 2: • Larry is a skillful artist. • Larry is a chess player • Therefore: Larry is a skillful chess player. (invalid!!)