Maximizing coverage and access to care under PPACA

- Slides: 23

Maximizing coverage and access to care under PPACA State Coverage Initiatives Program August 4, 2010 Stan Dorn The Urban Institute Sdorn@urban. org 202. 261. 5561

Overview n n n Maximizing enrollment and retention of eligible individuals Improving affordability and continuity of coverage and care above Medicaid income levels Increasing Medicaid beneficiaries’ access to care

But first: a quick review n Medicaid to 138% FPL Ø MAGI Ø Rules for newly eligible adults o Definition: would not have qualified under state rules as of 12/1/09 o Highly enhanced FMAP o “Benchmark benefits” Ø Standard FMAP for other adults n Subsidies in the exchange up to 400% FPL Ø OOP cost-sharing subsidies to 250% FPL – higher AV n n n Integrated eligibility system for Medicaid and exchange Individual mandate raises the stakes on enrollment Caveat: much hinges on how CMS interprets the law

Part I Maximizing enrollment and retention of eligible individuals

The need for public education and application assistance n The Massachusetts story Ø Major public education effort Ø Application assistance o “Virtual gateway” o CBO contracts o Provider incentives o > ½ of all successful applications came from CBOs and providers n n Other states have facilitated enrollment – CA, NY, WI, etc. Behavioral economics

Public education and application assistance under PPACA n n Responsibility of exchange Ø Patient navigators Ø Call centers Ø Federal funding through 12/31/14 Partner with local philanthropy Hospital-based presumptive eligibility Follow MA precedent in terms of safety net providers? Ø Must be done carefully, to avoid deterring access to care

Limit application forms to questions relevant to eligibility n Need to distinguish the newly eligible from others Ø Claim enhanced FMAP Ø Provide benchmark benefits n Requires information irrelevant to eligibility Ø Parents o Assets o Deprivation Ø Childless adults and empty nesters o Disability o Pregnancy n Solutions Ø To claim FMAP, use sampling Ø Provide standard Medicaid benefits as “Secretary-approved” benchmark coverage, Social Security Act Section 1937(b)(1)(D)

Asking for help without completing a traditional form n n Eligibility is determined based on data when an individual applies “by requesting a determination of eligibility and authorizing disclosure of … information [described in Social Security Act Sections 1137, 453(i), and 1942(a)] … to applicable State health coverage subsidy programs for purposes of determining and establishing eligibility. ” PPACA Section 1413(c)(2)(B)(ii)(II) Precedents Ø EITC amount Ø CA income tax Ø Medicare Parts B and D – automatic, without request

Requirements n Consumer must Ø Request for disclosure Ø Provide SSNs needed for data-matching n State and exchange must gather data Ø 1137 – IEVS, SAVE Ø 453(i) – National Directory of New Hires Ø 1902(a) – public benefit programs, new hires data, state tax records, Medicaid TPL data showing private coverage, vital statistics records in any state

Basing eligibility on receipt of other benefits n n n Express Lane Eligibility remains an option for children New SSA Section 902(e)(13)(D)(i)(I) says that MAGI does not apply to people “who are eligible for medical assistance … as a result of eligibility for, or receipt of, other Federal or State aid or assistance” [in addition to SSI] Implies that states can base Medicaid income -eligibility on receipt of other benefits Ø Logical if other program’s eligibility is far below 138% FPL

Basing eligibility on income data n Subsidies in exchange Ø Based on prior-year tax data Ø Chance to supplement at application Ø Year-end reconciliation n Medicaid Ø Initial determination based on income at time application is processed Ø Post-application changes? Not clear, under PPACA Ø What happens if application submitted to exchange?

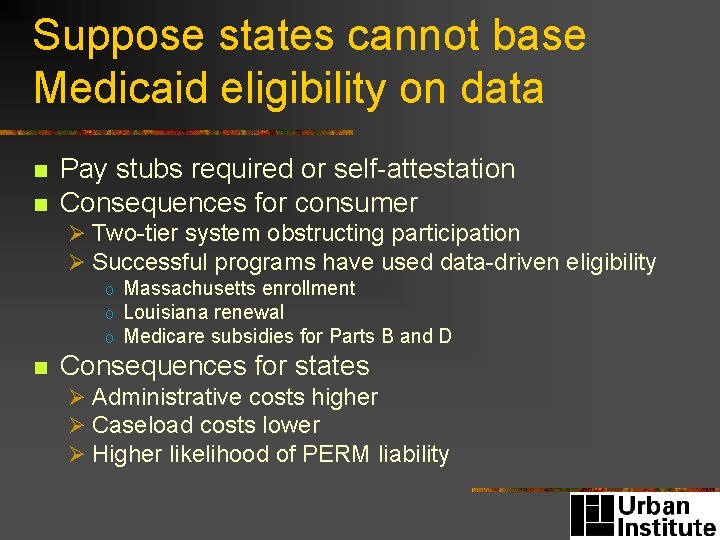

Suppose states cannot base Medicaid eligibility on data n n Pay stubs required or self-attestation Consequences for consumer Ø Two-tier system obstructing participation Ø Successful programs have used data-driven eligibility o Massachusetts enrollment o Louisiana renewal o Medicare subsidies for Parts B and D n Consequences for states Ø Administrative costs higher Ø Caseload costs lower Ø Higher likelihood of PERM liability

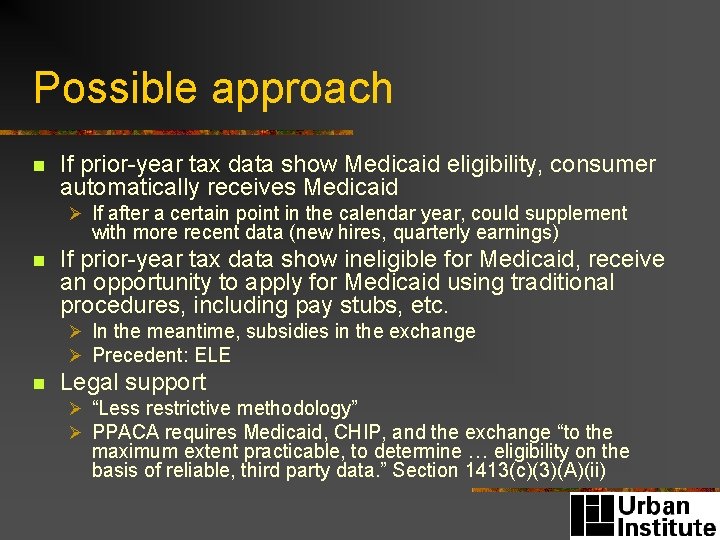

Possible approach n If prior-year tax data show Medicaid eligibility, consumer automatically receives Medicaid Ø If after a certain point in the calendar year, could supplement with more recent data (new hires, quarterly earnings) n If prior-year tax data show ineligible for Medicaid, receive an opportunity to apply for Medicaid using traditional procedures, including pay stubs, etc. Ø In the meantime, subsidies in the exchange Ø Precedent: ELE n Legal support Ø “Less restrictive methodology” Ø PPACA requires Medicaid, CHIP, and the exchange “to the maximum extent practicable, to determine … eligibility on the basis of reliable, third party data. ” Section 1413(c)(3)(A)(ii)

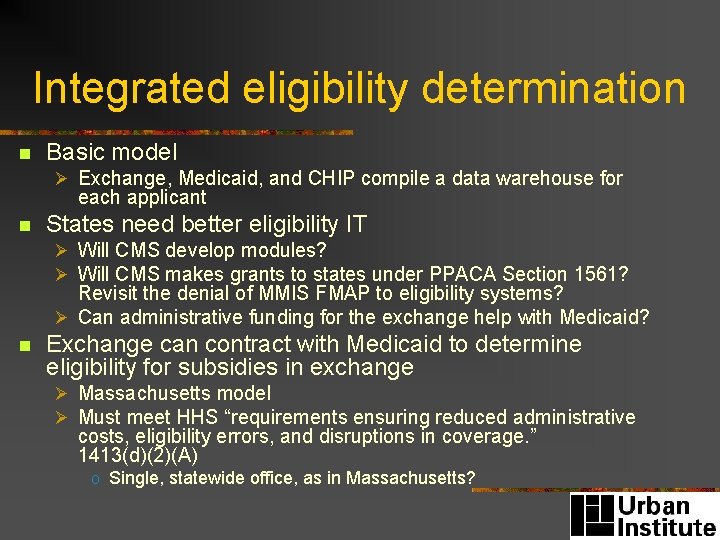

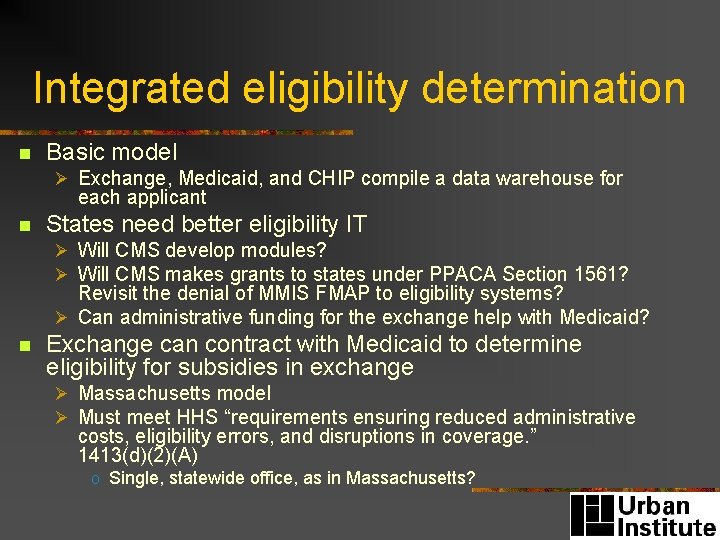

Integrated eligibility determination n Basic model Ø Exchange, Medicaid, and CHIP compile a data warehouse for each applicant n States need better eligibility IT Ø Will CMS develop modules? Ø Will CMS makes grants to states under PPACA Section 1561? Revisit the denial of MMIS FMAP to eligibility systems? Ø Can administrative funding for the exchange help with Medicaid? n Exchange can contract with Medicaid to determine eligibility for subsidies in exchange Ø Massachusetts model Ø Must meet HHS “requirements ensuring reduced administrative costs, eligibility errors, and disruptions in coverage. ” 1413(d)(2)(A) o Single, statewide office, as in Massachusetts?

Part II Improving affordability and continuity of coverage above Medicaid eligibility levels

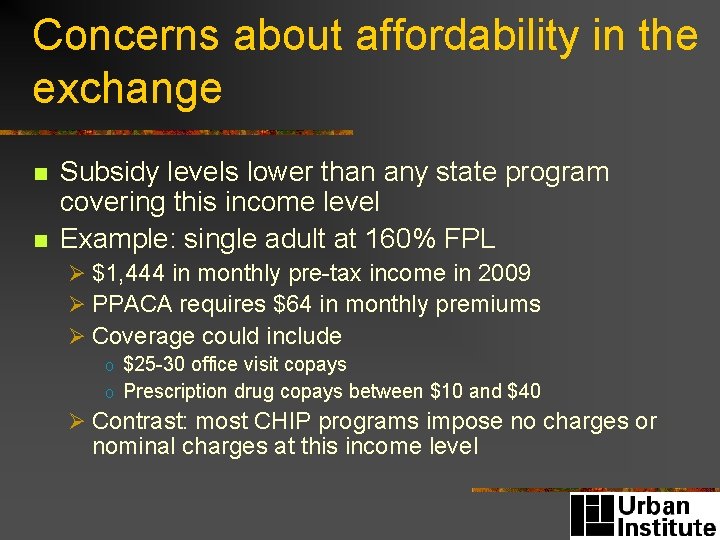

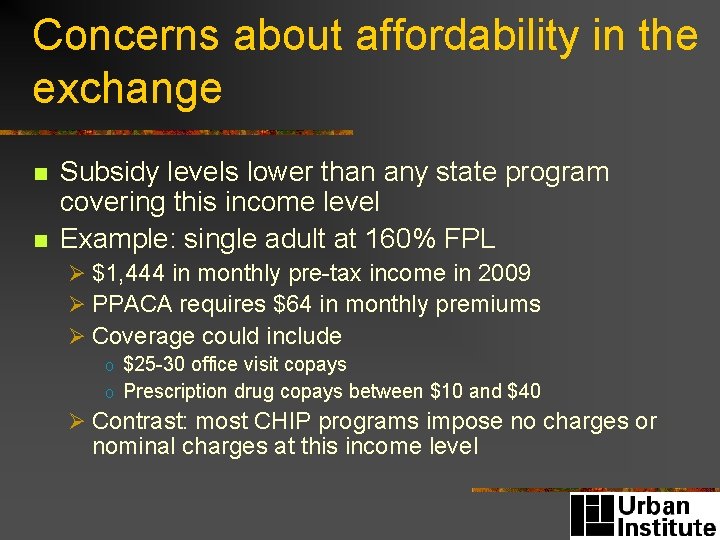

Concerns about affordability in the exchange n n Subsidy levels lower than any state program covering this income level Example: single adult at 160% FPL Ø $1, 444 in monthly pre-tax income in 2009 Ø PPACA requires $64 in monthly premiums Ø Coverage could include o $25 -30 office visit copays o Prescription drug copays between $10 and $40 Ø Contrast: most CHIP programs impose no charges or nominal charges at this income level

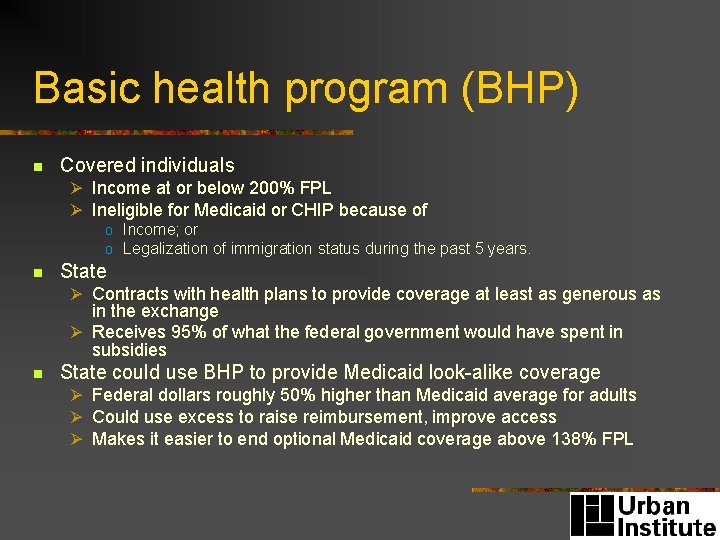

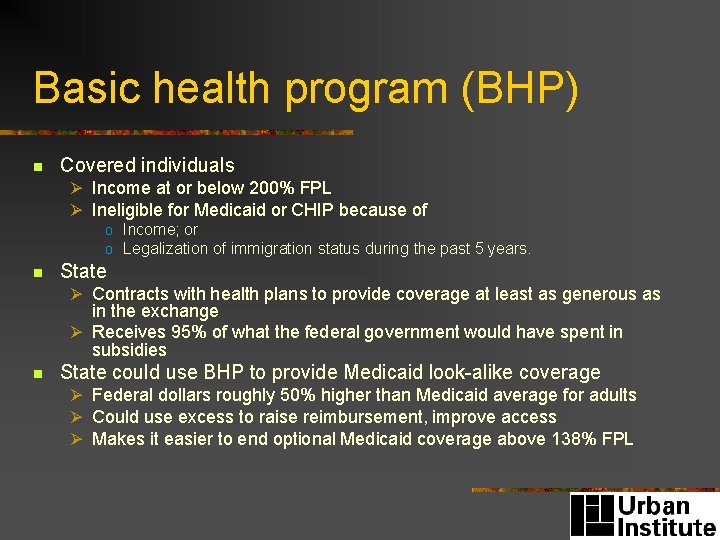

Basic health program (BHP) n Covered individuals Ø Income at or below 200% FPL Ø Ineligible for Medicaid or CHIP because of o Income; or o Legalization of immigration status during the past 5 years. n State Ø Contracts with health plans to provide coverage at least as generous as in the exchange Ø Receives 95% of what the federal government would have spent in subsidies n State could use BHP to provide Medicaid look-alike coverage Ø Federal dollars roughly 50% higher than Medicaid average for adults Ø Could use excess to raise reimbursement, improve access Ø Makes it easier to end optional Medicaid coverage above 138% FPL

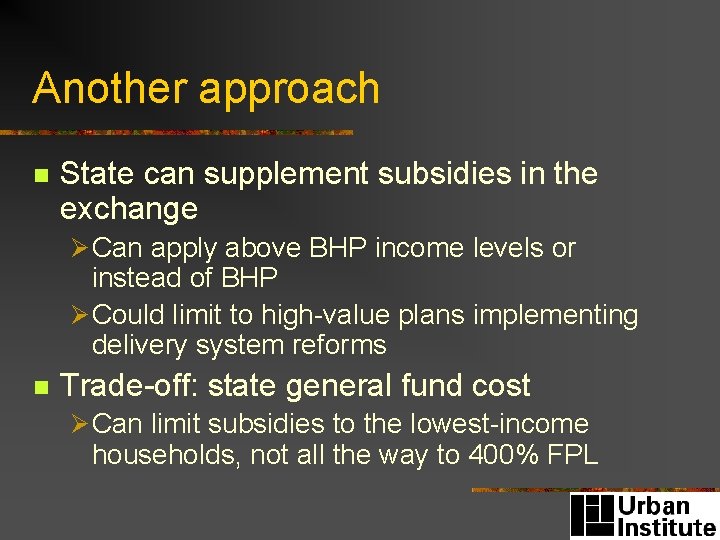

Another approach n State can supplement subsidies in the exchange Ø Can apply above BHP income levels or instead of BHP Ø Could limit to high-value plans implementing delivery system reforms n Trade-off: state general fund cost Ø Can limit subsidies to the lowest-income households, not all the way to 400% FPL

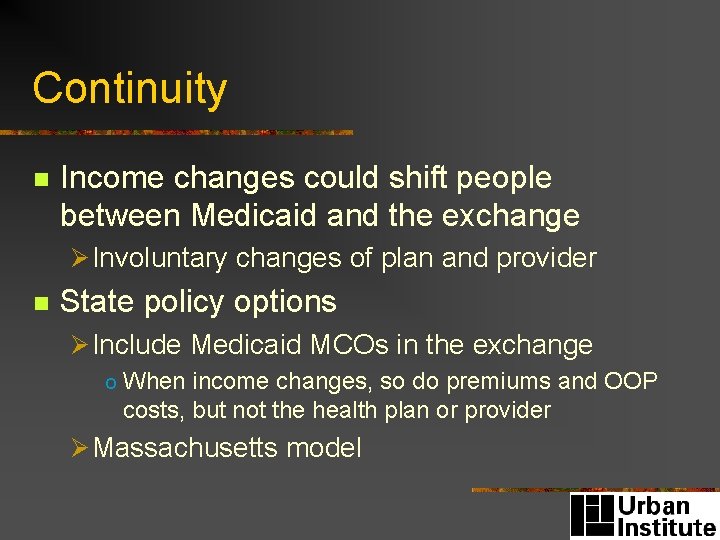

Continuity n Income changes could shift people between Medicaid and the exchange Ø Involuntary changes of plan and provider n State policy options Ø Include Medicaid MCOs in the exchange o When income changes, so do premiums and OOP costs, but not the health plan or provider Ø Massachusetts model

Part III Increasing access to care for Medicaid beneficiaries

PPACA n Raises reimbursement to Medicare levels, but… Ø Only for evaluation and management services Ø Only for primary care providers o Not for mental health, dentistry, specialists Ø 100% FMAP ends after 2013 and 2014 n Provides other infrastructure funding Ø $11 billion for community health centers n MACPAC

Alternatives to raising rates n n Streamline Medicaid claims processing Increase permitted scope of practice for non-physicians Ø Especially for Medicaid, potentially for other payors to address workforce shortages n n Rural tele-health Incentives to take Medicaid patients Ø Link to other coverage

Conclusion n n No matter what, PPACA is likely to dramatically increase coverage and access to care The amount of that increase will depend, in significant part, on state policy decisions