MAUS A SURVIVORS TALE PUN TWO VOLUMES MY

- Slides: 28

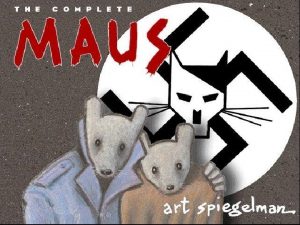

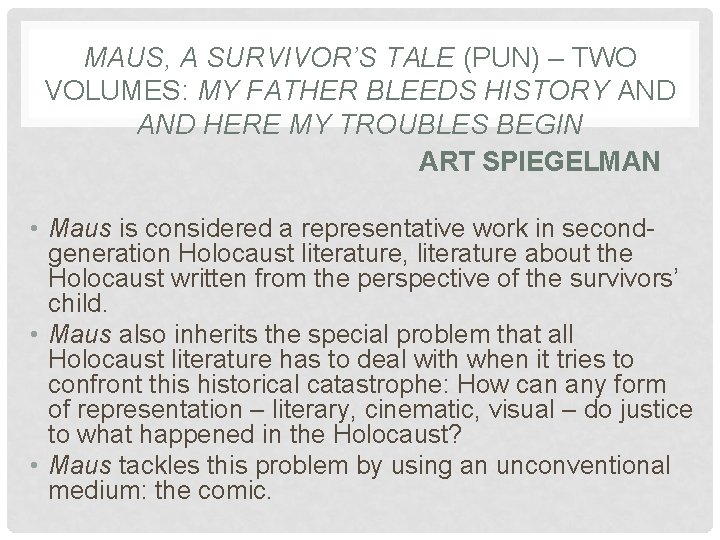

MAUS, A SURVIVOR’S TALE (PUN) – TWO VOLUMES: MY FATHER BLEEDS HISTORY AND HERE MY TROUBLES BEGIN ART SPIEGELMAN • Maus is considered a representative work in secondgeneration Holocaust literature, literature about the Holocaust written from the perspective of the survivors’ child. • Maus also inherits the special problem that all Holocaust literature has to deal with when it tries to confront this historical catastrophe: How can any form of representation – literary, cinematic, visual – do justice to what happened in the Holocaust? • Maus tackles this problem by using an unconventional medium: the comic.

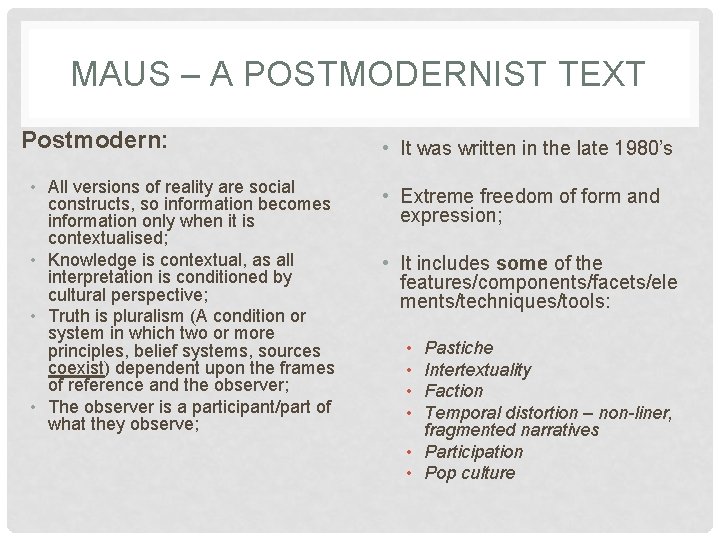

MAUS – A POSTMODERNIST TEXT Postmodern: • All versions of reality are social constructs, so information becomes information only when it is contextualised; • Knowledge is contextual, as all interpretation is conditioned by cultural perspective; • Truth is pluralism (A condition or system in which two or more principles, belief systems, sources coexist) dependent upon the frames of reference and the observer; • The observer is a participant/part of what they observe; • It was written in the late 1980’s • Extreme freedom of form and expression; • It includes some of the features/components/facets/ele ments/techniques/tools: • • Pastiche Intertextuality Faction Temporal distortion – non-liner, fragmented narratives • Participation • Pop culture

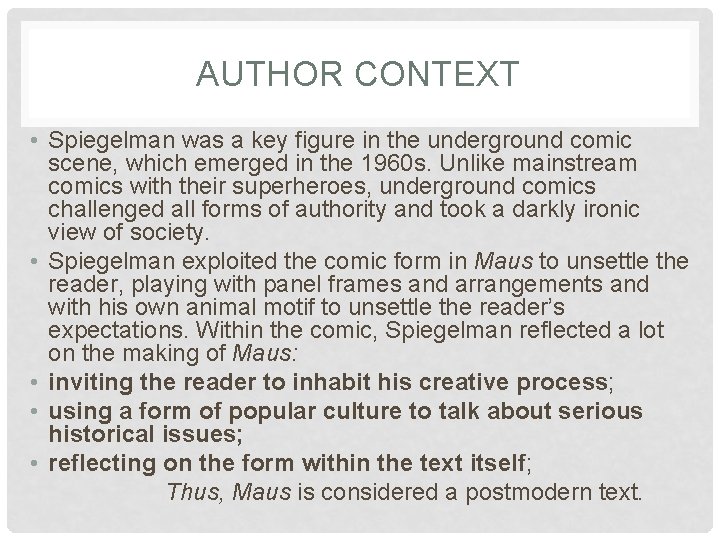

AUTHOR CONTEXT • Spiegelman was a key figure in the underground comic scene, which emerged in the 1960 s. Unlike mainstream comics with their superheroes, underground comics challenged all forms of authority and took a darkly ironic view of society. • Spiegelman exploited the comic form in Maus to unsettle the reader, playing with panel frames and arrangements and with his own animal motif to unsettle the reader’s expectations. Within the comic, Spiegelman reflected a lot on the making of Maus: • inviting the reader to inhabit his creative process; • using a form of popular culture to talk about serious historical issues; • reflecting on the form within the text itself; Thus, Maus is considered a postmodern text.

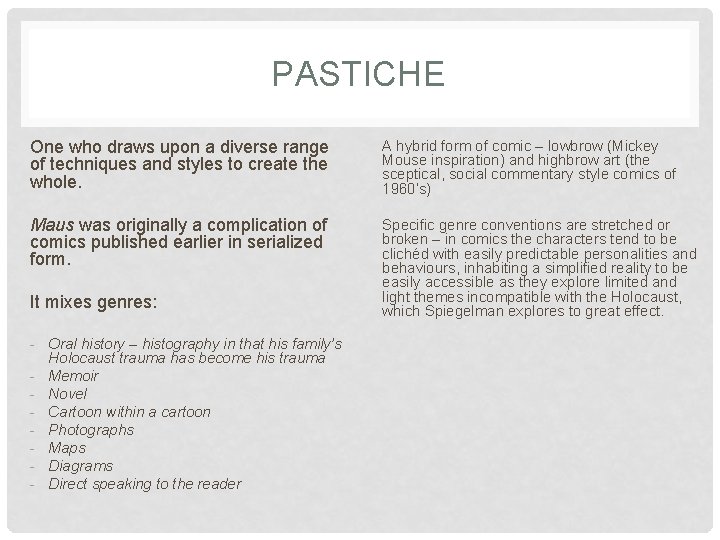

PASTICHE One who draws upon a diverse range of techniques and styles to create the whole. A hybrid form of comic – lowbrow (Mickey Mouse inspiration) and highbrow art (the sceptical, social commentary style comics of 1960’s) Maus was originally a complication of comics published earlier in serialized form. Specific genre conventions are stretched or broken – in comics the characters tend to be clichéd with easily predictable personalities and behaviours, inhabiting a simplified reality to be easily accessible as they explore limited and light themes incompatible with the Holocaust, which Spiegelman explores to great effect. It mixes genres: - Oral history – histography in that his family’s Holocaust trauma has become his trauma - Memoir - Novel - Cartoon within a cartoon - Photographs - Maps - Diagrams - Direct speaking to the reader

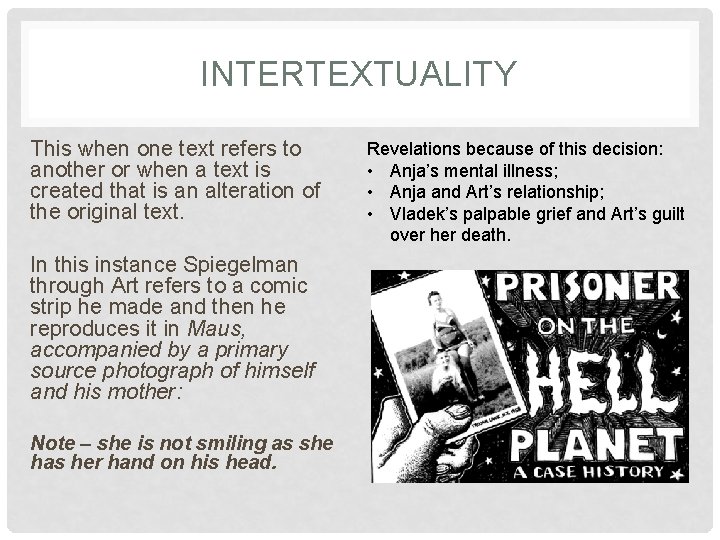

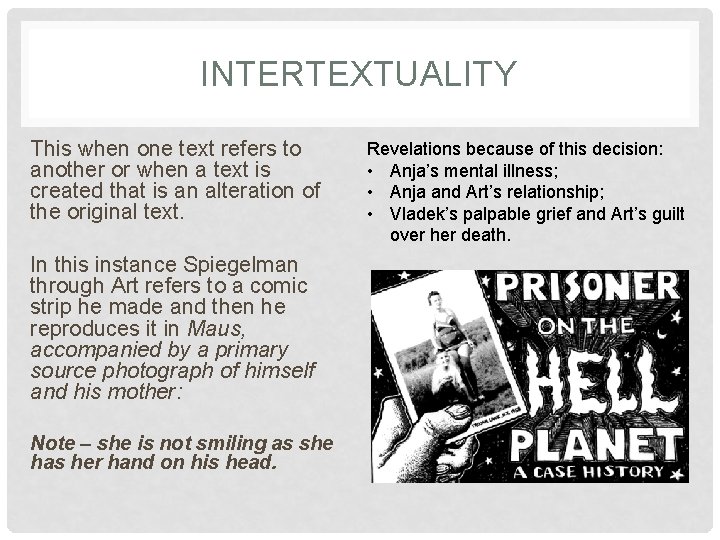

INTERTEXTUALITY This when one text refers to another or when a text is created that is an alteration of the original text. In this instance Spiegelman through Art refers to a comic strip he made and then he reproduces it in Maus, accompanied by a primary source photograph of himself and his mother: Note – she is not smiling as she has her hand on his head. Revelations because of this decision: • Anja’s mental illness; • Anja and Art’s relationship; • Vladek’s palpable grief and Art’s guilt over her death.

FACTION – A MIX OF FACT AND FICTION Whilst comics were inclusively fiction, history was fact with no ambiguities or uncertainties. The text was a revolt against the concept of history being empiric; full of universal truths based on the concept that knowledge is objective, independent of context; How can a single account convey the dynamic, multivalent, contested nature of any cultural group or phenomenon with any accuracy or objectivity? The interdependence of the two narratives of Vladek and Art means that history is blurred, rather than being absolute. Author’s second generation perspective, (which prevents history being passed down in Vladek’s version is based on a transformation of memories. an accurate and unaltered form), Three factors contributing to subjective nature of the text: 1. 2. 3. representation of reality; An oral history with hundreds of hours of tapes and testimonies, in which the recreation of an absolute history is impossible; The process of textual production - the volumes deconstruct, reconstruct, and mediate source material. Maus is neither a verbatim transcription of his interviews nor an objective representation of history. It is, rather, a heavily mediated and self-reflexive reconstruction of the complex culture of one family.

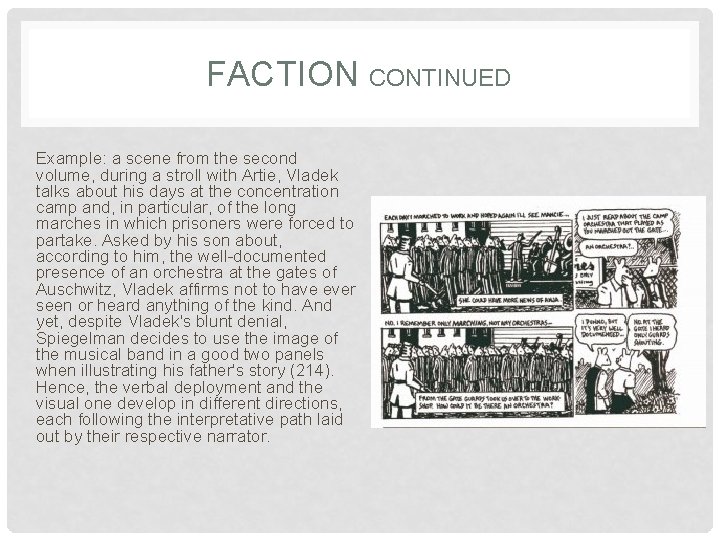

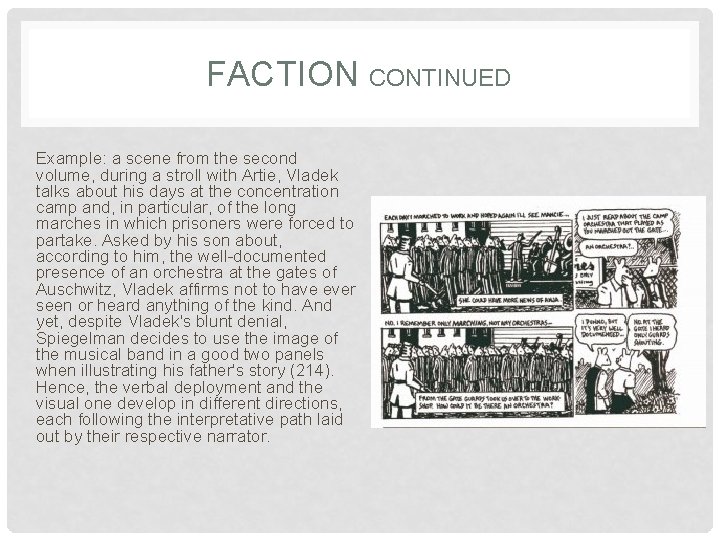

FACTION CONTINUED Example: a scene from the second volume, during a stroll with Artie, Vladek talks about his days at the concentration camp and, in particular, of the long marches in which prisoners were forced to partake. Asked by his son about, according to him, the well-documented presence of an orchestra at the gates of Auschwitz, Vladek affirms not to have ever seen or heard anything of the kind. And yet, despite Vladek's blunt denial, Spiegelman decides to use the image of the musical band in a good two panels when illustrating his father's story (214). Hence, the verbal deployment and the visual one develop in different directions, each following the interpretative path laid out by their respective narrator.

TEMPORAL DISTORTION Moving backwards and forwards in time. Open panels – space and time escape, leave, move, disappear forever; Bleeding panels (broken gutter) – time infinite; Constant changes from the Vladek recollections to the present within the narrative. • Text opens with Art’s memory; • First instance then is ‘The Sheik’, then on top right of p. 22 Vladek appears with the memory of the poison letter; • Every chapter begins in the present, at the time of Art collecting information on Vladek’s life and his own issues, then it plunges into Vladek’s recollections. • Often Art is so focussed on a chronological order of recollections so he forces his father back from tangent anecdotes and onto the next event. In one instance Vladek wants to speak of Richieu, but Art overrides him and it is another 30 pages until readers are given the awful truth of Richieu’s demise. This narrative disruption is clearly shown in the title page of the first chapter of Maus II, which includes the illustration with the word “Mauschwitz” mentioned above; however, Vladek’s narration about his experiences in Auschwitz does not begin until fourteen pages later. The intervening pages focus on Art’s continued struggles with his father in the present, demonstrating - before Vladek’s narration continues - who is framing Vladek’s narrative, and how deeply challenged Art feels about the prospect of representing his father, and his father’s story, fairly.

PARTICIPATION 1. Maus is a composite work, characterized by a significant inter-related perspectives caught up in constant confrontation. The title of the volume A Survivor's Tale may, on the one hand, point at a narrative of an exclusively biographical order related to Vladek Spiegelman. However, the presence of the possessive adjective 'my' in both of the subheadings of the volumes is a indication of the active involvement of the second narrator and protagonist: Art. Thus, Art as an artist/narrator and historian enforces his own visualization and illustrations of the events. 2. Maus differs from traditional oral histories in the ways it exposes and examines its own constructedness and the biases of its creator. Thus, the constructed and interpretive nature of the illustration process, too, is made transparent. For example, in a scene toward the end of Maus I, Art comes to Vladek and Mala’s house to show them some of the preliminary sketches for the book and Maus II begins with Art wondering aloud to his wife, Françoise, how he should draw her since she is French by birth. In the latter scene, Art questions whether Françoise should be depicted as a frog (like the other French characters)or as a mouse (since she converted to Judaism when they married). The “debate” the two have about how Françoise should be representedis, of course, deeply ironic in its placement at the beginning of the second book: Françoise has already appeared as a mouse throughout the first book. Thus, Spiegelman’s decision to begin the second installment with this scene underscores his desire to call attention to the work’s constructedness.

ANTHROPOMORPHISM Anthropomorphism - Giving human characteristics to animals; Physiognomy- a person's facial features or expression, especially when regarded as indicative of character or ethnic origin; Metaphor - figure of speech containing an implied comparison, in which a word or phrase (in this case an image/animal) ordinarily and primarily used for one thing is applied to another; Stereotypes is a way of reducing the large topic to something easier to understand, and at the same time, harder. *Critic – doubly dehumanizing to reduce the treatment of Jews by the Nazis to a cat and mouse scenario and also that there are obvious graphical limitations in portraying figures in cartoon form.

POP CULTURE Pop culture Modelled on American mainstream ’funny-animal’ comic heroes: consider Disney’s anthropomorphic Mickey Mouse (1928 cartoons Steamboat Willie and 1930 comics); Thus, Spiegelman was using visual syntax that was only traditionally considered for simple entertainment, violating a taboo of Holocaust representation. This was an unprecedented eruption of pop culture inside the world of real and harrowing extermination. Maus constitutes an extension of the underground style in which these traditionally funny events are replaced by the tragic story of the Holocaust survivor; *The obvious metaphor is meant to dissolve as the reader enters the narrative as they discover that the animal masks have enormous symbolic significance: 1. The perception of reality of on the part of the Nazis and those they persecute; 2. The power relationships among the ethnicities under the Third Reich.

SPIEGELMAN’S OBJECTIVE The animal metaphor is, in fact, the outcome of an intentional kinship with the figural imagery of the Reich. Inside the text, such a relation is preannounced in the epigraph of both volumes: the first, placed at the beginning of Maus, quotes excerpts of one of the Fuhrer's speeches: "The Jews are undoubtedly a race, but they are not human" while the following epigraph (164), taken from an article published in a German newspaper in the 1930 s, expands the Nazi ideological horizons overseas, explicitly recalling the most famouse character in comics, Mickey Mouse, defined as "the most miserable ideal ever revealed [. ] the dirty and filth-covered vermin, the greatest bacteria carrier in the animal kingdom".

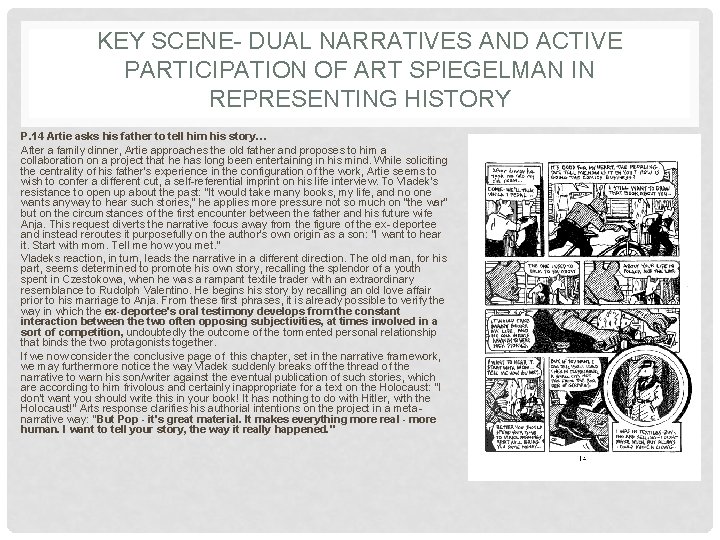

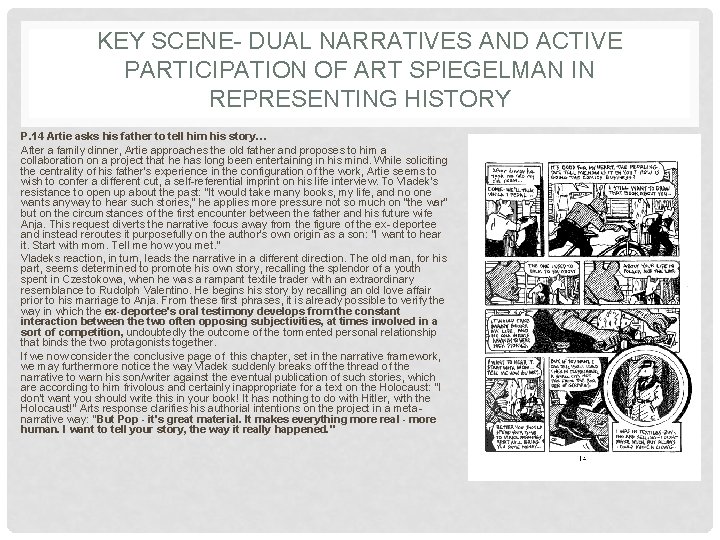

KEY SCENE- DUAL NARRATIVES AND ACTIVE PARTICIPATION OF ART SPIEGELMAN IN REPRESENTING HISTORY P. 14 Artie asks his father to tell him his story… After a family dinner, Artie approaches the old father and proposes to him a collaboration on a project that he has long been entertaining in his mind. While soliciting the centrality of his father's experience in the configuration of the work, Artie seems to wish to confer a different cut, a self-referential imprint on his life interview. To Vladek's resistance to open up about the past: "It would take many books, my life, and no one wants anyway to hear such stories, " he applies more pressure not so much on "the war" but on the circumstances of the first encounter between the father and his future wife Anja. This request diverts the narrative focus away from the figure of the ex- deportee and instead reroutes it purposefully on the author's own origin as a son: "I want to hear it. Start with mom. Tell me how you met. " Vladeks reaction, in turn, leads the narrative in a different direction. The old man, for his part, seems determined to promote his own story, recalling the splendor of a youth spent in Czestokowa, when he was a rampant textile trader with an extraordinary resemblance to Rudolph Valentino. He begins his story by recalling an old love affair prior to his marriage to Anja. From these first phrases, it is already possible to verify the way in which the ex-deportee's oral testimony develops from the constant interaction between the two often opposing subjectivities, at times involved in a sort of competition, undoubtedly the outcome of the tormented personal relationship that binds the two protagonists together. If we now consider the conclusive page of this chapter, set in the narrative framework, we may furthermore notice the way Vladek suddenly breaks off the thread of the narrative to warn his son/writer against the eventual publication of such stories, which are according to him frivolous and certainly inappropriate for a text on the Holocaust: "I don't want you should write this in your book! It has nothing to do with Hitler, with the Holocaust!" Arts response clarifies his authorial intentions on the project in a metanarrative way: "But Pop - it's great material. It makes everything more real - more human. I want to tell your story, the way it really happened. "

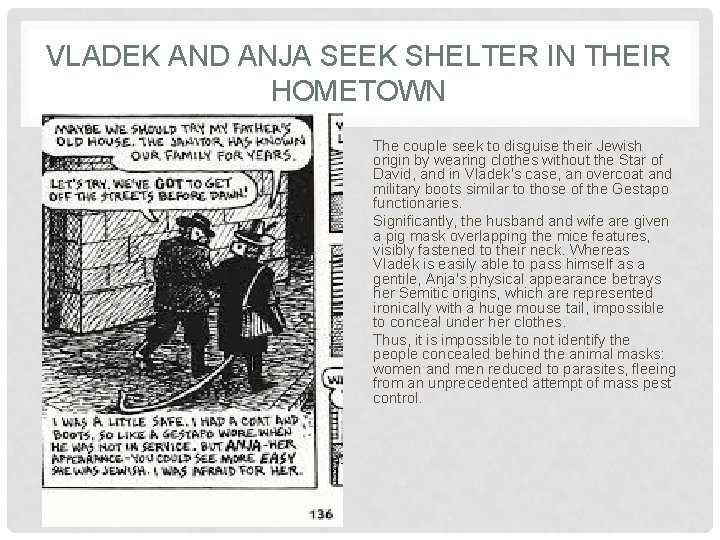

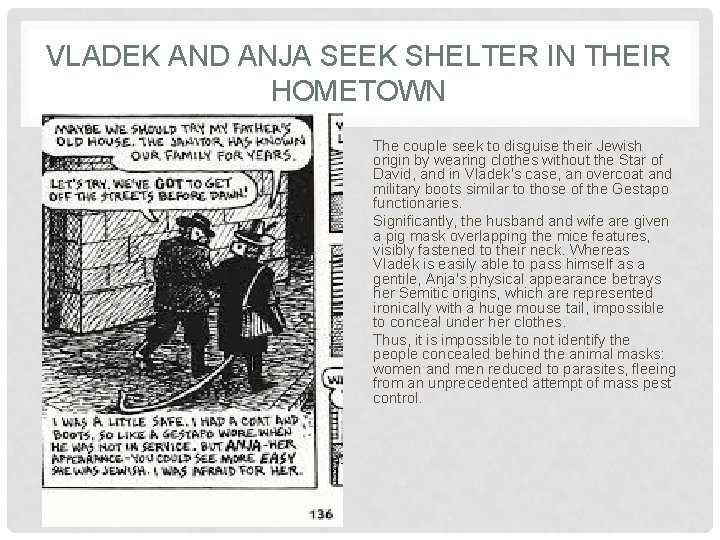

VLADEK AND ANJA SEEK SHELTER IN THEIR HOMETOWN The couple seek to disguise their Jewish origin by wearing clothes without the Star of David, and in Vladek's case, an overcoat and military boots similar to those of the Gestapo functionaries. Significantly, the husband wife are given a pig mask overlapping the mice features, visibly fastened to their neck. Whereas Vladek is easily able to pass himself as a gentile, Anja's physical appearance betrays her Semitic origins, which are represented ironically with a huge mouse tail, impossible to conceal under her clothes. Thus, it is impossible to not identify the people concealed behind the animal masks: women and men reduced to parasites, fleeing from an unprecedented attempt of mass pest control.

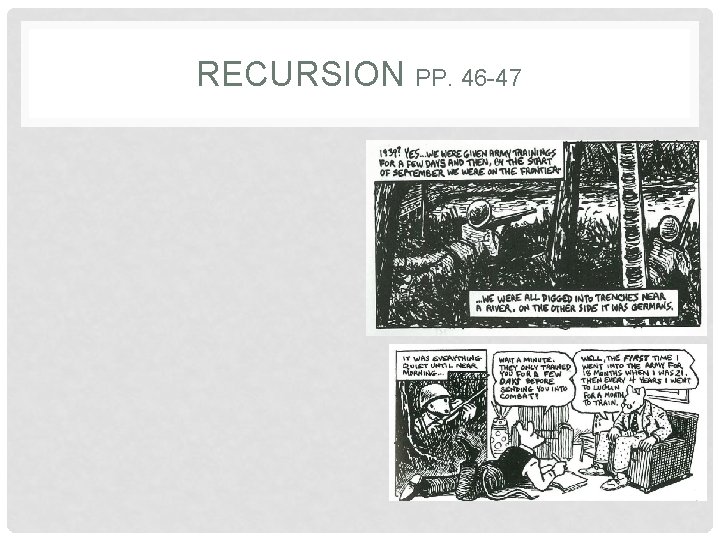

RECURSION PP. 46 -47

UNRELIABLE NARRATOR PP. 76 -77

ART AND VLADEK P. 161

PIVOTAL EVENT PP. 110 -111

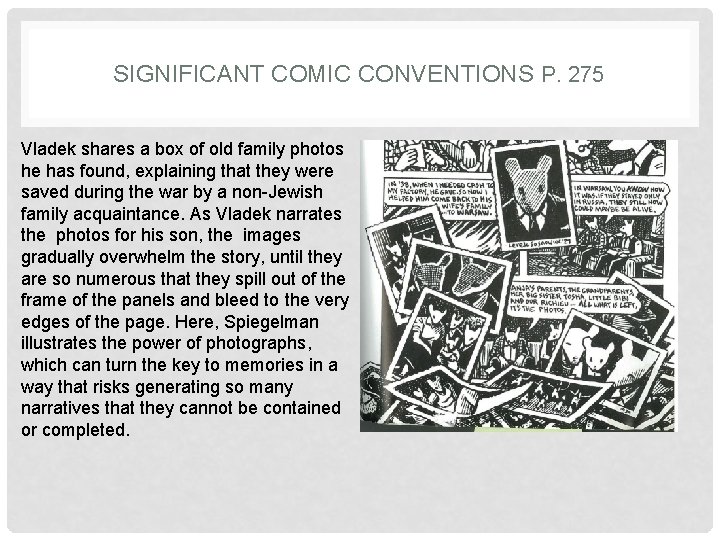

SIGNIFICANT COMIC CONVENTIONS P. 275 Vladek shares a box of old family photos he has found, explaining that they were saved during the war by a non-Jewish family acquaintance. As Vladek narrates the photos for his son, the images gradually overwhelm the story, until they are so numerous that they spill out of the frame of the panels and bleed to the very edges of the page. Here, Spiegelman illustrates the power of photographs, which can turn the key to memories in a way that risks generating so many narratives that they cannot be contained or completed.

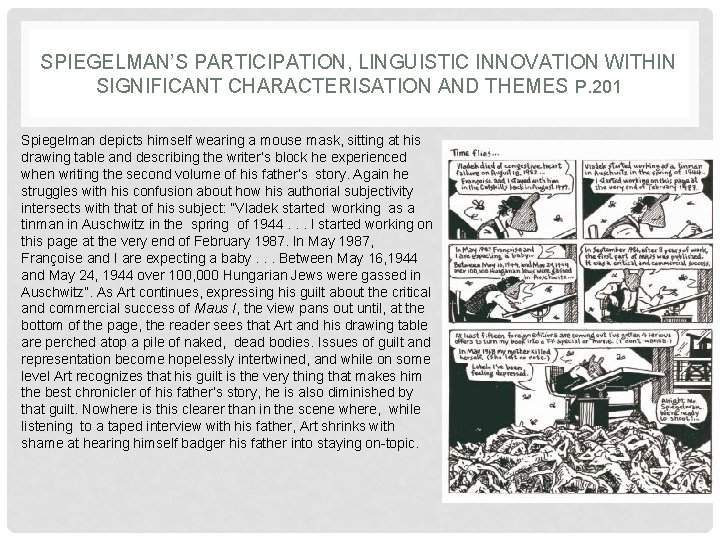

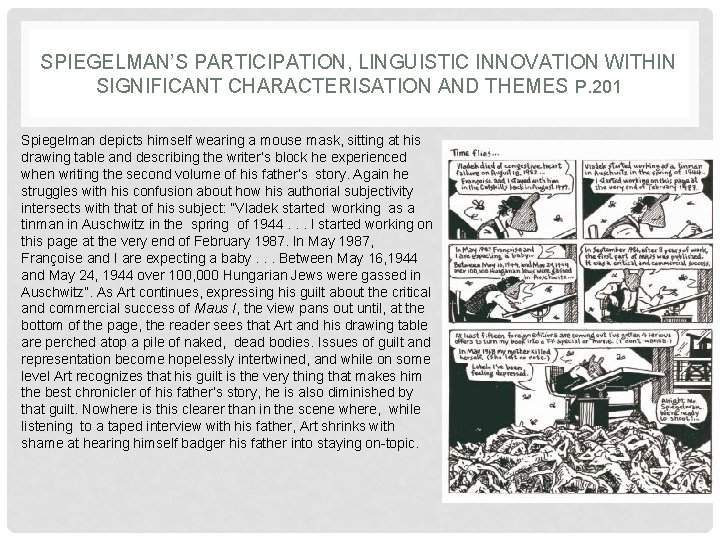

SPIEGELMAN’S PARTICIPATION, LINGUISTIC INNOVATION WITHIN SIGNIFICANT CHARACTERISATION AND THEMES P. 201 Spiegelman depicts himself wearing a mouse mask, sitting at his drawing table and describing the writer’s block he experienced when writing the second volume of his father’s story. Again he struggles with his confusion about how his authorial subjectivity intersects with that of his subject: “Vladek started working as a tinman in Auschwitz in the spring of 1944. . . I started working on this page at the very end of February 1987. In May 1987, Françoise and I are expecting a baby. . . Between May 16, 1944 and May 24, 1944 over 100, 000 Hungarian Jews were gassed in Auschwitz”. As Art continues, expressing his guilt about the critical and commercial success of Maus I, the view pans out until, at the bottom of the page, the reader sees that Art and his drawing table are perched atop a pile of naked, dead bodies. Issues of guilt and representation become hopelessly intertwined, and while on some level Art recognizes that his guilt is the very thing that makes him the best chronicler of his father’s story, he is also diminished by that guilt. Nowhere is this clearer than in the scene where, while listening to a taped interview with his father, Art shrinks with shame at hearing himself badger his father into staying on-topic.

THE ONLY TIME ART SPEAKS TO PAVEL PP. 203 -206

THE END – VLADEK’S FINAL WORDS

REFLECTION In films especially, but also in other texts the depiction of the Holocaust made it somewhat detached from the reader or viewer, a horror story, a distant nightmare, not quite real because it was so hard to comprehend. Spiegelman's challenge was to bring the Holocaust closer to readers, to make it become a tangible, intimate and authentic portrayal of this black stain in history. To bridge that distance he needed to make a connection between the Holocaust and his father’s experience in the Holocaust, and to represent his father’s experiences as faithfully as possible – these are his constant preoccupations. Maus doe not present an epic Hollywood tale, with forces of Good and Evil, heroes and villains. Maus puts readers in the real world, in the lives of ordinary people trying to deal with extraordinary, horrible, terrifying, but very real circumstances. Sadly, it is a stark reminder of the inhumanity that can occur when nationalistic fervor, racism and the power of the collective leads to a complete loss of individual identity, responsibility and morality.

CONCLUSION Other than influencing Maus from the formal and structural points of view, the oral dimension confers an aura of skepticism and relativity upon the work, maintaining the narrative constantly hovered between present and past, history and imagination, reality and fiction. In Maus, objectivity is not demanded: while underlining the value of his father's testimony, the author contextually highlights inevitable gaps and incongruities, welcoming both the certainties and the psychological alterations of memory. Spiegelman does not even hesitate to disclose the limits of his project, not only highlighting the arbitrariness of many of his choices but also studding the narrative with considerations on the difficulty of adequately representing a reality of such graveness and so distant in time and space. As he affirmed in an interview, "essentially, the number of layers between an event and somebody trying to apprehend that event through time and intermediaries is like working with flickering shadows. It's all you can hope for. " Zygmunt Bauman: "Postmodernity is modernity reconciled to its own impossibility and determined - for better or worse, to live with it. " In his work, Spiegelman emphasizes the subjectivity of both the testifier and the historian/biographer, renouncing to reconstruct an authoritative, monolithic version of history, proposing instead a series of stories, each of which is accredited and, at the same time, challenged by the very same protagonists and narrators.

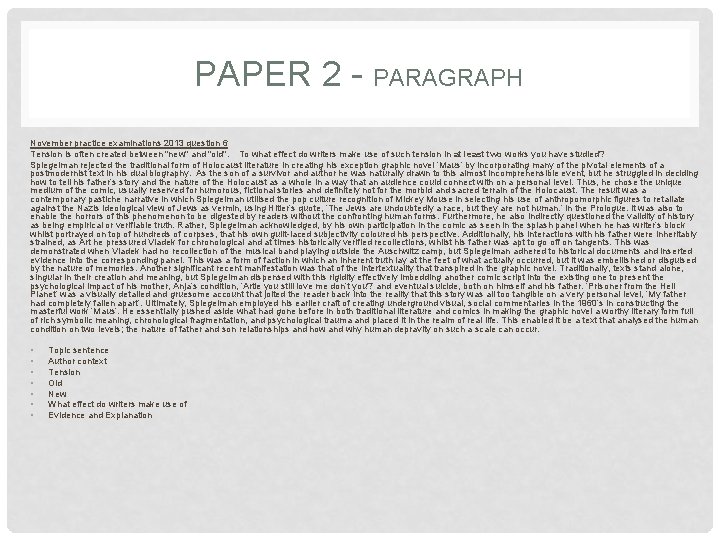

PAPER 2 - PARAGRAPH November practice examinations 2013 question 6 Tension is often created between "new" and "old". To what effect do writers make use of such tension in at least two works you have studied? Spiegelman rejected the traditional form of Holocaust literature in creating his exception graphic novel ‘Maus’ by incorporating many of the pivotal elements of a postmodernist text in his dual biography. As the son of a survivor and author he was naturally drawn to this almost incomprehensible event, but he struggled in deciding how to tell his father’s story and the nature of the Holocaust as a whole in a way that an audience could connect with on a personal level. Thus, he chose the unique medium of the comic, usually reserved for humorous, fictional stories and definitely not for the morbid and sacred terrain of the Holocaust. The result was a contemporary pastiche narrative in which Spiegelman utilised the pop culture recognition of Mickey Mouse in selecting his use of anthropomorphic figures to retaliate against the Nazis ideological view of Jews as vermin, using Hitler’s quote, ‘The Jews are undoubtedly a race, but they are not human. ’ in the Prologue. It was also to enable the horrors of this phenomenon to be digested by readers without the confronting human forms. Furthermore, he also indirectly questioned the validity of history as being empirical or verifiable truth. Rather, Spiegelman acknowledged, by his own participation in the comic as seen in the splash panel when he has writer’s block whilst portrayed on top of hundreds of corpses, that his own guilt-laced subjectivity coloured his perspective. Additionally, his interactions with his father were inheritably strained, as Art he pressured Vladek for chronological and at times historically verified recollections, whilst his father was apt to go off on tangents. This was demonstrated when Vladek had no recollection of the musical band playing outside the Auschwitz camp, but Spiegelman adhered to historical documents and inserted evidence into the corresponding panel. This was a form of faction in which an inherent truth lay at the feet of what actually occurred, but it was embellished or disguised by the nature of memories. Another significant recent manifestation was that of the intertextuality that transpired in the graphic novel. Traditionally, texts stand alone, singular in their creation and meaning, but Spiegelman dispensed with this rigidity effectively imbedding another comic script into the existing one to present the psychological impact of his mother, Anja’s condition, ‘Artie you still love me don’t you? ’ and eventual suicide, both on himself and his father. ‘Prisoner from the Hell Planet’ was a visually detailed and gruesome account that jolted the reader back into the reality that this story was all too tangible on a very personal level, ‘My father had completely fallen apart’. Ultimately, Spiegelman employed his earlier craft of creating underground visual, social commentaries in the 1960’s in constructing the masterful work ‘Maus’. He essentially pushed aside what had gone before in both traditional literature and comics in making the graphic novel a worthy literary form full of rich symbolic meaning, chronological fragmentation, and psychological trauma and placed it in the realm of real life. This enabled it be a text that analysed the human condition on two levels; the nature of father and son relationships and how and why human depravity on such a scale can occur. • • Topic sentence Author context Tension Old New What effect do writers make use of Evidence and Explanation

PAPER 2 PARAGRAPH – YOUR TURN May examination 2013 question 3 Why are the works you have studied considered "literary" texts? Identify and discuss some of the features that make at least two of the texts you have studied literary. Literary works are those that have: • Significantly complex and detailed literary devices particularly in metaphor and symbolism because deeper, figurative meanings are embedded in the text through these techniques and so they then accommodate deeper and more layered themes; • Chronology because the times present, past and future can be used to serve greater purposes than cause and effect, before and after sequencing of events. Chronology can either develop unity or create fragmentation; it can be cohesive or it can disrupt and disturb; • Psychological characterization exposes the mental, cognitive and emotional processes that build or curtail relationships, they drive the progress and depth of the narrative revealing inner motives, confusion, restlessness and alike in order to examine the human condition; • Additionally, real life experiences can be presented in order to understand universal characteristics of human life.

PAPER 2 PARAGRAPH – YOUR TURN May examination 2013 question 4 In what ways is the reader seduced or comforted by the ideas in the works studied and in what ways challenged or alienated? Refer to at least two of the literary works you have studied.

PAPER 2 PARAGRAPH – YOUR TURN May examination 2013 question 6 Literary works often show men and women struggling to resolve problems and not succeeding very well. To what degree do you find this to be true in at least two of the works you have studied?

Folk character

Folk character Siegfried sassoon survivors analysis

Siegfried sassoon survivors analysis Dra survivors

Dra survivors How does the red kangaroo adapt to the desert

How does the red kangaroo adapt to the desert Survivors teaching students

Survivors teaching students Calciphylaxis survivors

Calciphylaxis survivors Find similar images

Find similar images Tap dancing puns

Tap dancing puns Puns in act 1 of the importance of being earnest

Puns in act 1 of the importance of being earnest What is an example of a caesura?

What is an example of a caesura? Pun

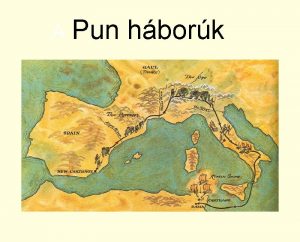

Pun Hbork

Hbork Ugaona linija

Ugaona linija Pun genrator

Pun genrator Summary of the most dangerous game

Summary of the most dangerous game Kekecualian partikel pun

Kekecualian partikel pun Rhetorical question examples

Rhetorical question examples Figurative language exaggeration

Figurative language exaggeration Tökéletlen történelem hannibál

Tökéletlen történelem hannibál Pun in hamlet

Pun in hamlet Contoh ayat tiada rotan akar pun berguna

Contoh ayat tiada rotan akar pun berguna Pun háborúk zanza

Pun háborúk zanza Pan ziod

Pan ziod Simile in mending wall

Simile in mending wall Sambungan peribahasa

Sambungan peribahasa Literary elements symbolism

Literary elements symbolism Pun and zeugma

Pun and zeugma David pun

David pun Intrebari factuale

Intrebari factuale