Mathematical Modeling with a Social Conscious This session

- Slides: 21

Mathematical Modeling with a Social Conscious This session presents a working definition of math used to implement socially conscious mathematics while ensuring that the math maintains its rigor. the goal is to see math as a “research activity” that opens up new ways of seeing the world. “For the things of this world cannot be made known without a knowledge of mathematics” Roger Bacon Marty Romero “There is no branch of mathematics, however abstract, which may not someday be applied to the phenomena of the real world. ” Nicholas Lobachevsky UCLA Graduate School of Education maromero@ucla. edu allrealsblog. wordpress. com CMC-South Annual Conference November 1 st , 2013 “The great book of nature can be read only be those who know the language in which it is written. And this language is mathematics. ” Galileo

Session Outline • What is Mathematics, and mathematical thinking • See explicit examples of the “Science of Patterns” • Demonstrate a functions-based (Data Driven) approach and mathematical modeling instruction • Connect the definition of mathematics to the purpose of education, the common core standards of mathematical practice, college and career readiness skills, social justice mathematics, socially conscious mathematicians, mathematics equity • Share classroom examples of activities/projects that are related to the definition of mathematics, mathematical modeling • Share classroom social justice activities/projects

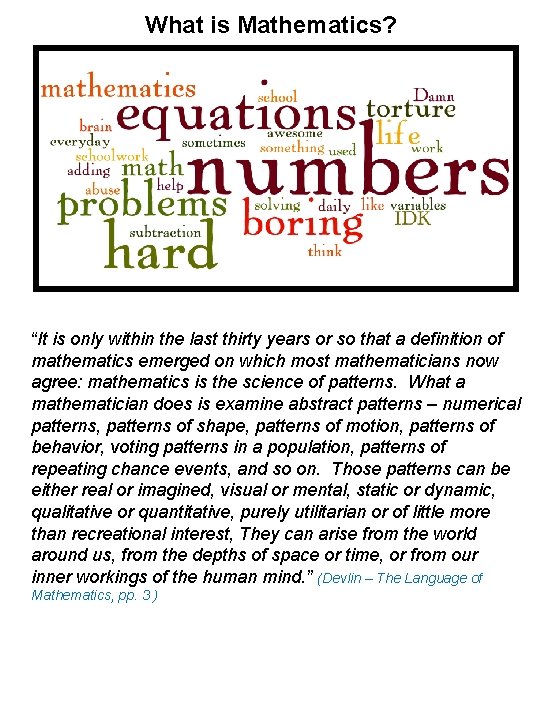

What is Mathematics? “It is only within the last thirty years or so that a definition of mathematics emerged on which most mathematicians now agree: mathematics is the science of patterns. What a mathematician does is examine abstract patterns – numerical patterns, patterns of shape, patterns of motion, patterns of behavior, voting patterns in a population, patterns of repeating chance events, and so on. Those patterns can be either real or imagined, visual or mental, static or dynamic, qualitative or quantitative, purely utilitarian or of little more than recreational interest, They can arise from the world around us, from the depths of space or time, or from our inner workings of the human mind. ” (Devlin – The Language of Mathematics, pp. 3 )

Why Study Mathematics from this perspective (Science of Patterns)? This succinct definition of mathematics explicitly links the learning of mathematics to a fundamental neuroscience view; “human brains operate…in terms of pattern recognition rather than logic”. Further buttressing a motivation to learn mathematics from this perspective, Hawkins (2004) argues that, "patterns are all the brain knows about. They are pattern machines”.

Strands of Mathematical Proficiency (National Research Council) • • • conceptual understanding (comprehension of mathematical concepts, operations, and relations) procedural fluency (skills in carrying out procedures flexibly, fluently, and appropriately), strategic competence (ability to formulate, represent, and solve mathematical problems) adaptive reasoning (capacity for logical thought, reflection, explanation, and justification) productive disposition (habitual inclination to see mathematics as sensible, useful, and worthwhile, coupled with a belief in diligence and one's own efficacy).

Mathematical Thinking • thinking is the means used by humans to improve their understanding of, and exert some control over, their environment (Burton, 1984, p. 36). Burton (1984) describes these means –the operations, processes, and dynamics of mathematical thinking - as encompassing four processes, specializing, conjecturing, generalizing, and convincing. “mathematical thinking is used when tackling appropriate problems in any context area, although questions of a mathematical nature might more readily expose such thinking” (Burton, 1984, p. 36). The key to recognizing and using mathematical thinking lies in creating an atmosphere that builds confidence to question, challenge, and reflect. Behind such behavior is an acknowledgment of the need to: *query assumptions *negotiate meanings *pose questions *make conjectures *search for justifying and falsifying arguments that convince *check, modify, alter *be self-critical *be aware of different approaches *be willing to shift, renegotiate, change direction

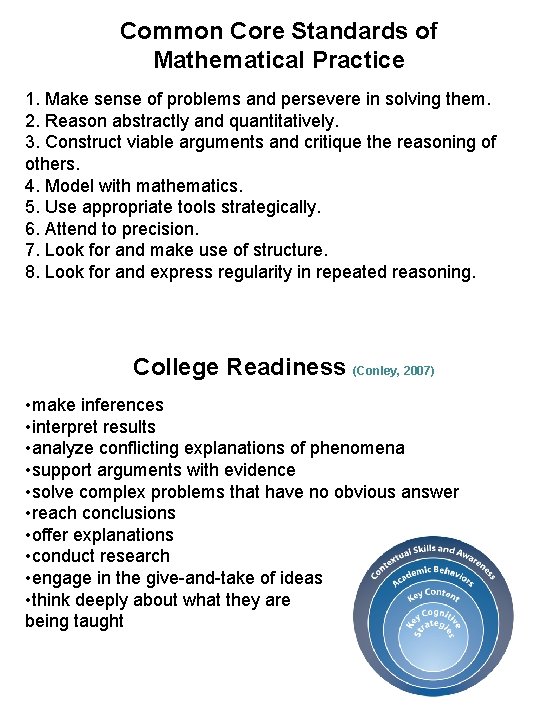

Common Core Standards of Mathematical Practice 1. Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. 2. Reason abstractly and quantitatively. 3. Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others. 4. Model with mathematics. 5. Use appropriate tools strategically. 6. Attend to precision. 7. Look for and make use of structure. 8. Look for and express regularity in repeated reasoning. College Readiness (Conley, 2007) • make inferences • interpret results • analyze conflicting explanations of phenomena • support arguments with evidence • solve complex problems that have no obvious answer • reach conclusions • offer explanations • conduct research • engage in the give-and-take of ideas • think deeply about what they are being taught

The Mathematical Method (Doing Mathematics) (Devlin, 2012) • Identify a particular pattern in the world • Study it (Conjecture, Guess, Question, Discuss, Share) • Develop a notation to describe it (Algebra/ Graphs / Equations) • Use that notation to further the study (Answer questions, Pose Problems, Solve Equations) • Formulate basic assumptions (axioms) to capture the fundamental properties of the abstracted pattern • Study the abstracted pattern, establishing truths by means of rigorous proofs form the axioms (Convince) • Develop procedures that you and others may use to apply the results of the study to the world • Apply the results to the world Mathematical Modeling (Pollack, 2013) Mathematical modeling, on the other hand, begins in the “unedited” real world, requires problem formulating before problem solving, and once the problem is solved, moves back into the real world where the results are considered in their original context. Mathematically proficient students can apply the mathematics they know to solve problems arising in everyday life, society, and the workplace. In early grades, this might be as simple as writing an addition equation to describe a situation. In middle grades, a student might apply proportional reasoning to plan a school event or analyze a problem in the community. By high school, a student might use geometry to solve a design problem or use a function to describe how one quantity of interest depends on another. Mathematically proficient students who can apply what they know are comfortable making assumptions and approximations to simplify a complicated situation, realizing that these may need revision later. They are able to identify important quantities in a practical situation and map their relationships using such tools as diagrams, two-way tables, graphs, flowcharts and formulas. They can analyze those relationships mathematically to draw conclusions. They routinely interpret their mathematical results in the context of the situation and reflect on whether the results make sense, possibly improving the model if it has not served its purpose.

The Science of Patterns 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, ___, ___ O, T, T, F, F, ___, ___ 1, 2, 4, ___, ___ 1, 4, 9, ___, ___ Count to 25 starting at 1 by either 1’s or 2’s. Functions-Based Approach to Describe the World

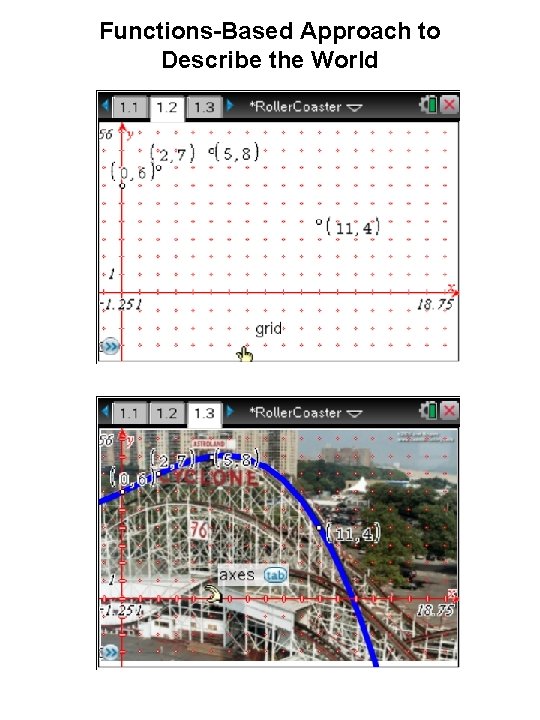

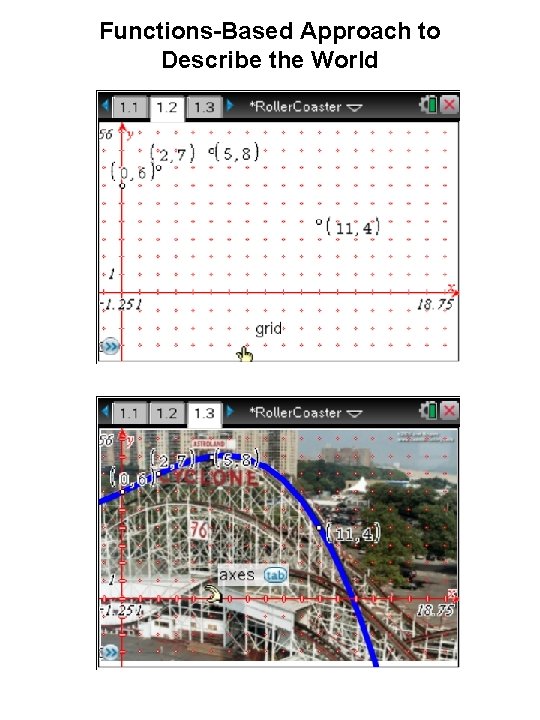

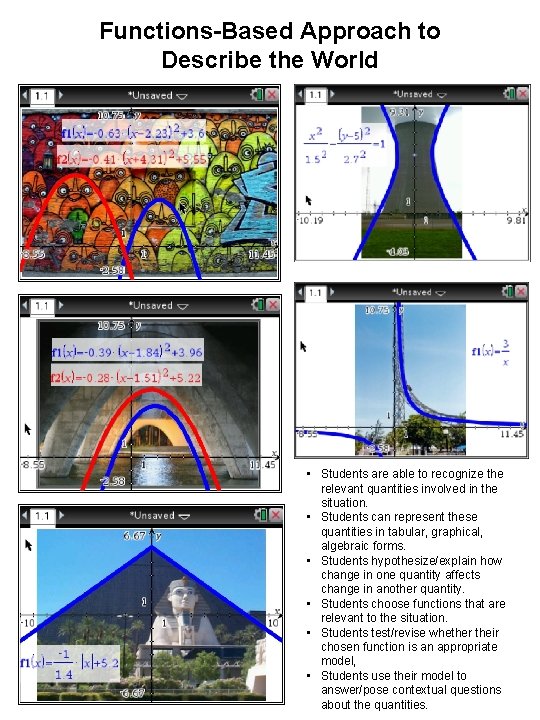

Functions-Based Approach to Describe the World

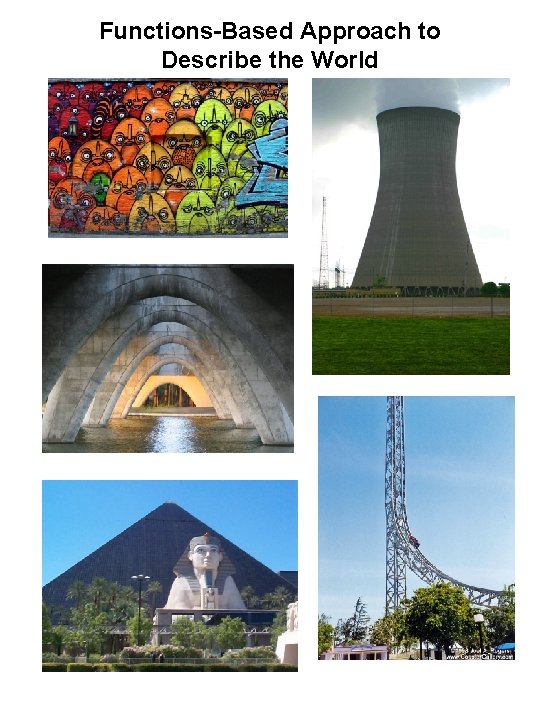

Functions-Based Approach to Describe the World

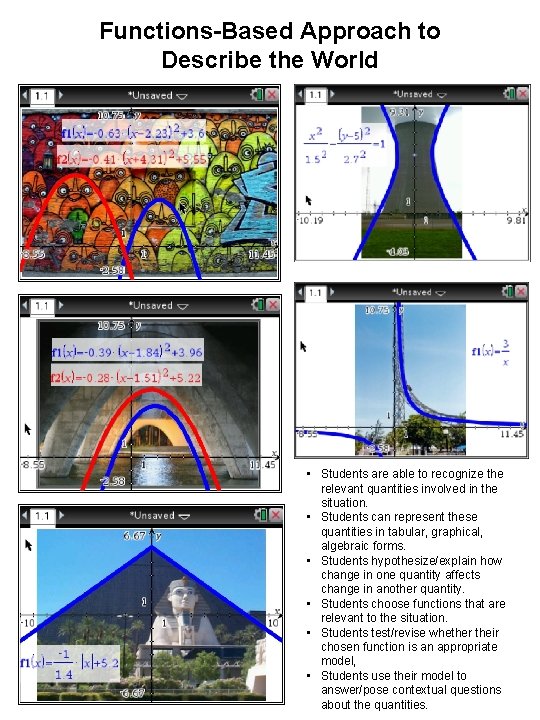

Functions-Based Approach to Describe the World • Students are able to recognize the relevant quantities involved in the situation. • Students can represent these quantities in tabular, graphical, algebraic forms. • Students hypothesize/explain how change in one quantity affects change in another quantity. • Students choose functions that are relevant to the situation. • Students test/revise whether their chosen function is an appropriate model, • Students use their model to answer/pose contextual questions about the quantities.

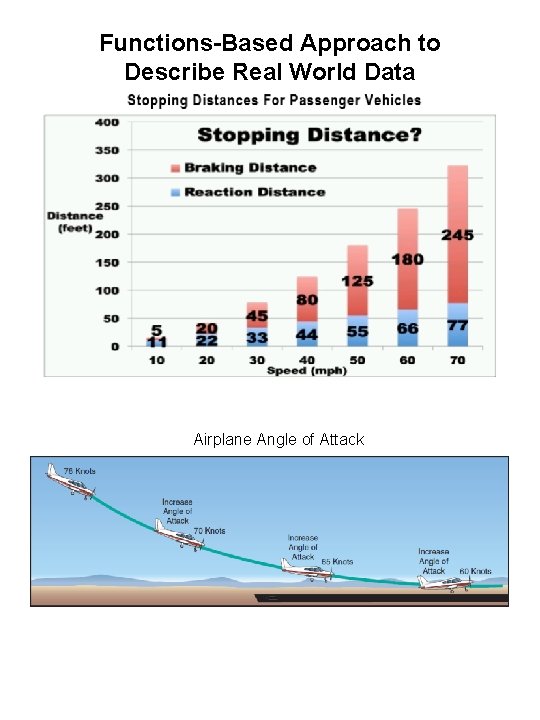

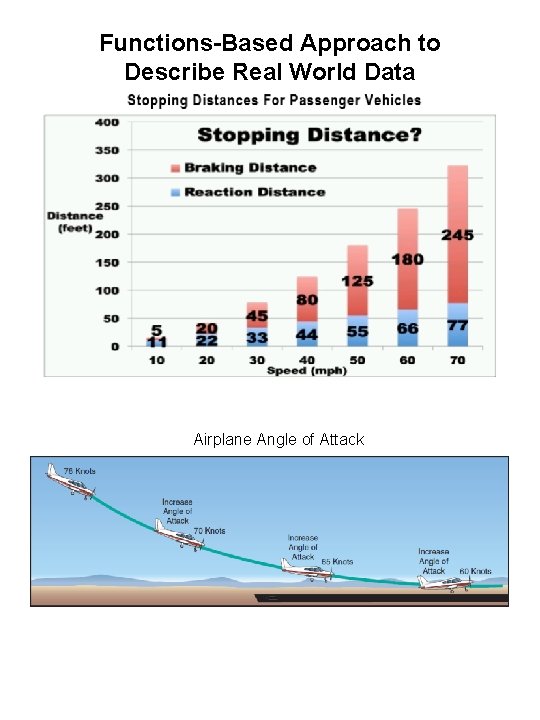

Functions-Based Approach to Describe Real World Data Airplane Angle of Attack

Functions-Based Approach to Describe the Real World through Video Other Resources Graphingstories. com Dan Meyer : 3 Acts Robert Kaplinsky robertkaplinsky. com Video Physics App

What is the Purpose of Education? “The purpose of education is to enable individuals to reach their full potential as human beings, individually and as members of a society; this means that these individuals will receive an education which will enable them to think and act intelligently and purposefully in exercising and protecting the Rights and Responsibilities claimed by the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the American Dream. ” (http: //www. 21 stcenturyschools. com/Purpose_of_Education. htm) “The “highest goal in life is to inquire and create. The purpose of education from that point of view is just to help people to learn on their own. It’s you the learner who is going to achieve in the course of education and it’s really up to you to determine how you’re going to master and use it. ” An essential part of this kind of education is fostering the impulse to challenge authority, think critically, and create alternatives to well-worn models. ” - Noam Chomsky

Critical Pedagogy Teaching Mathematics for Social Justice Conversations with Educators (NCTM) Rooted in a democratic project of justice and freedom, critical pedagogy supports pedagogical theories and practices that drive both teachers and students to acknowledge and understand the interconnecting relationships among ideology, power, and culture and the social structures and practices that produce and reproduce knowledge. Rejecting any claim to “objective” universal truths, critical pedagogy motivates new theories and languages of critique and resistance to examine and transform social and pedagogical practices that maintain unjust social codes (Leistyna and Woodrum 1996). Critical Mathematics Education (Gutierrez, 2013) Two Main Goals: 1. Develop within learners a kind of political awareness that allows the individual to recognize her or his position in society and as a part of history (Freire, 1987) 2. Motivate individuals to action

Criticalmathematics Teaching Mathematics for Social Justice Conversations with Educators (NCTM) 2. as teachers, criticalmathematics educators (a) listen well (as opposed to telling) and recognize and respect the intellectual activity of students, understanding that “the intellectual activity of those without power is always characterized as non-intellectual” (Freire and Macedo 1987); (b) maintain high expectations and demand a lot from their students, insisting that students take their own intellectual work seriously, and that they participate actively as “co- interrogators” (Powell 1986) in the learning process; (c) are not merely “accidental presences” (Freire 1982) in the classroom, but are active participants in the educational dialogue, participants capable of advancing theoretical understanding of others as well as themselves, participants who can have a stronger understanding than their students (Youngman 1986); (d) assume that minds do not exist separate from bodies, and that the bodies or material conditions, in which the potential and will to learn reside, are female as well as male and in a range of colors; that thought develops through interactions in the world, and that people come from a variety of ethnic, cultural, and economic backgrounds; that people have made different life choices, based on personal situations and institutional constraints, and that people teach and learn from a corresponding number of perspectives; (e) believe that “most cases of learning problems or low achievement in schools can be explained primarily on motivational grounds” (Ginsburg 1986) and in relationship to social, economic, political, and cultural context, as opposed to in terms of a “lack of aptitude” or “cognitive deficit”; (f) recognize the reality of mathematics “anxiety, ” but deal with it in a way that does not blame the victims, and that recognizes both the personal psychological aspects and the broader societal causes; (g) recognize that everyone has mathematical ideas; criticalmathematics educators “work hard to understand the logic of other peoples, of other ways of thinking” (Fasheh 1989).

Social Justice Mathematics Education Teaching Mathematics for Social Justice Conversations with Educators (NCTM) Teaching mathematics about social justice refers to the context of lessons that explore critical (and oftentimes controversial) social issues using mathematics. Teaching mathematics with social justice refers to the pedagogical practices that encourage a co-created classroom and provides a classroom culture that encourages opportunities for equal participation and status. And teaching mathematics for social justice is the underlying belief that mathematics can and should be taught in a way that supports students in using mathematics to challenge the injustices of the status quo as they learn to read and rewrite their world (Freire, 1970/2000). Human well-being: A context- and situation-dependent state, comprising basic material for a good life, freedom and choice, health and bodily well-being, good social relations, security, peace of mind, and spiritual experience. (D’Ambrosio, 2012)

Social Justice Mathematics Education From – Rethinking Mathematics Students can learn that mathematics is an essential analytical tool to understand potentially change the world. Students can understand their own power as active citizens in building a democratic society and become equipped to play an active role in that society using mathematics as a resource. Students see mathematics as a powerful and relevant tool for understanding complicated, real-world phenomena rather than a series of disconnected, rote rules to be memorized and regurgitated. Move toward a problem-posing (vs. problem solving) pedagogy: Teachers and students pose issues/problems that must be tackled intellectually (i. e. mathematically) and through action. Students can deepen their understanding of important social issues, such as racism and sexism, as well as ecology and social class

Why Study Mathematics at All and Think Mathematically? • Math is Everywhere • Because you can and you want to be good at it • Productive Mathematical Thinking Improves Higher. Order Thinking Skills • (Career Ready) Improved Higher Thinking Skills are important to function in most jobs and careers • College Ready => Better Jobs ; STEM JOBS => Even More Financial Freedom • Math is Useful for their Life (Financial Decisions, Access to Resources) • Social and Intellectual Capital (People Treat You Differently Because you are smart) • Equity – Help Close the Achievement Gap • Math Needs You • Can Exert Control of Their World (Agency and Empowerment)

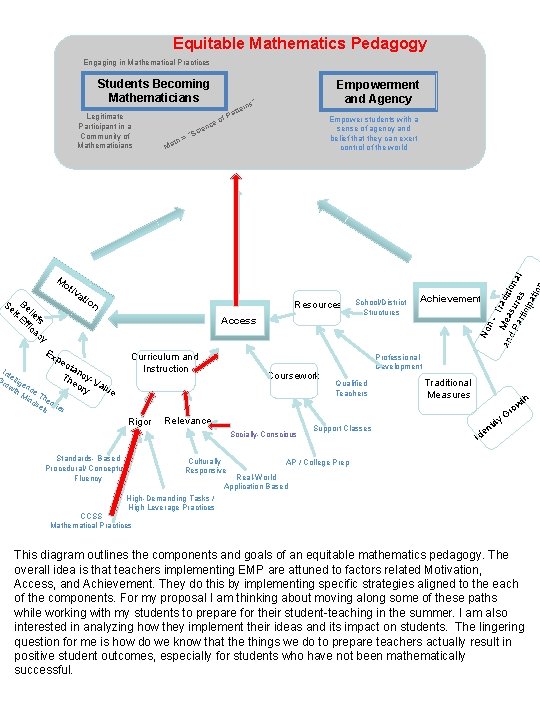

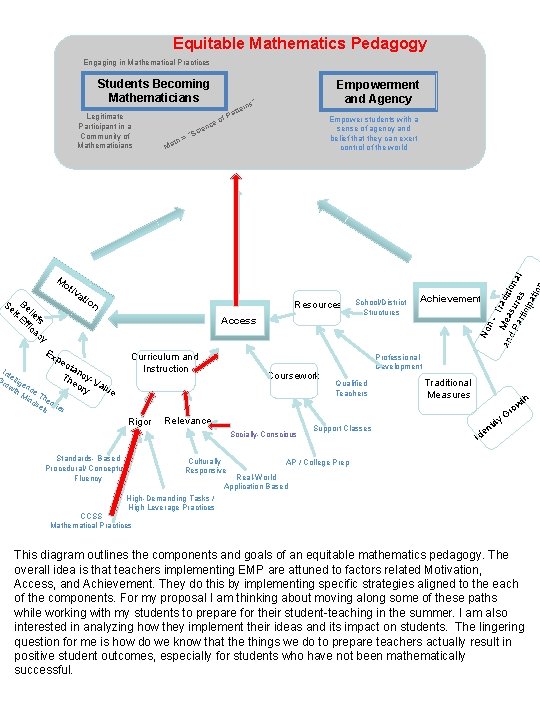

Equitable Mathematics Pedagogy Engaging in Mathematical Practices Legitimate Participant in a Community of Mathematicians nce th Ma ie Sc =“ tte a f. P o rns Empowerment and Agency ” Empower students with a sense of agency and belief that they can exert control of the world Mo tiv at Se Be lf- lie Ef fs fic ac y io n Resources Achievement No Access School/District Structures n. Tra M d an e a d P su ition r art es al icip ati o Students Becoming Mathematicians Ex pe Curriculum and Instruction cta n Th cy-V eo ry alue Int Gr ellig ow en th ce Mi Th nd eo se rie ts s Rigor Coursework Relevance Socially-Conscious Standards- Based Procedural/ Conceptual Fluency Culturally Responsive Professional Development Qualified Teachers Support Classes Traditional Measures tity o Gr h wt n de I AP / College Prep Real-World Application Based High-Demanding Tasks / High Leverage Practices CCSS Mathematical Practices This diagram outlines the components and goals of an equitable mathematics pedagogy. The overall idea is that teachers implementing EMP are attuned to factors related Motivation, Access, and Achievement. They do this by implementing specific strategies aligned to the each of the components. For my proposal I am thinking about moving along some of these paths while working with my students to prepare for their student-teaching in the summer. I am also interested in analyzing how they implement their ideas and its impact on students. The lingering question for me is how do we know that the things we do to prepare teachers actually result in positive student outcomes, especially for students who have not been mathematically successful.