MATH 374 Lecture 10 Chapter 4 Linear Differential

- Slides: 15

MATH 374 Lecture 10 Chapter 4: Linear Differential Equations

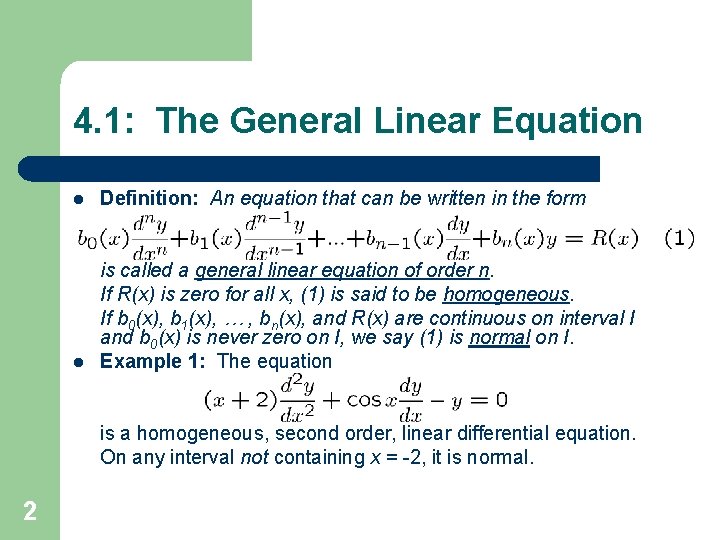

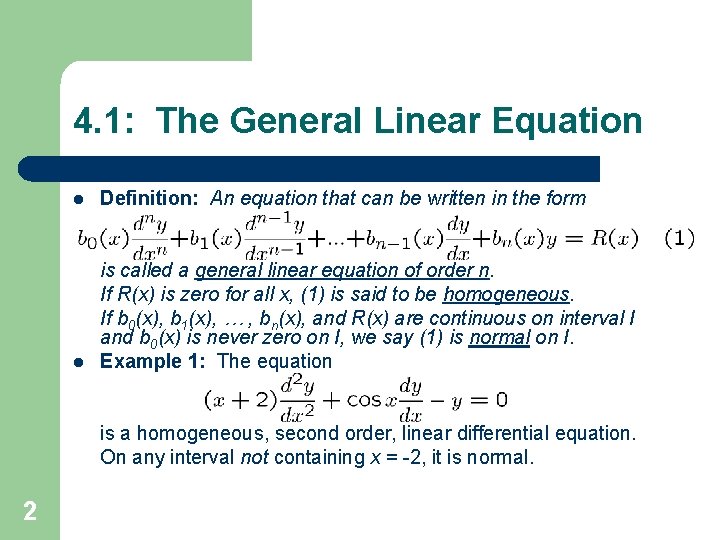

4. 1: The General Linear Equation l Definition: An equation that can be written in the form l is called a general linear equation of order n. If R(x) is zero for all x, (1) is said to be homogeneous. If b 0(x), b 1(x), … , bn(x), and R(x) are continuous on interval I and b 0(x) is never zero on I, we say (1) is normal on I. Example 1: The equation is a homogeneous, second order, linear differential equation. On any interval not containing x = -2, it is normal. 2

Linear Combination of Functions l l 3 Definition: A linear combination of the functions {f 1, f 2, … , fk } is a function of the form: c 1 f 1 + c 2 f 2 + … + ck fk where c 1, c 2, … , ck are constants. An important property of linear, homogeneous differential equations is the Principle of Superposition!

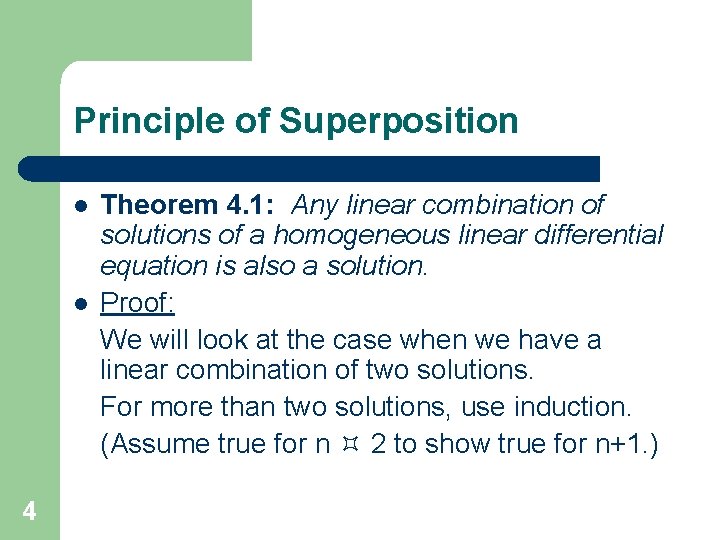

Principle of Superposition l l 4 Theorem 4. 1: Any linear combination of solutions of a homogeneous linear differential equation is also a solution. Proof: We will look at the case when we have a linear combination of two solutions. For more than two solutions, use induction. (Assume true for n 2 to show true for n+1. )

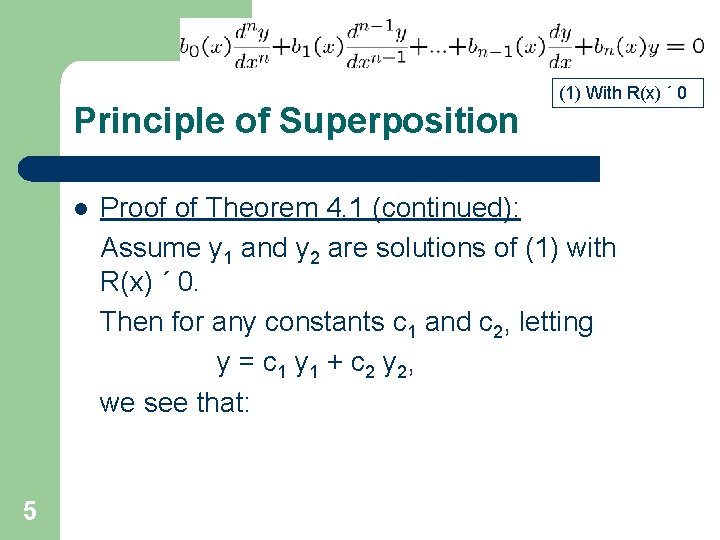

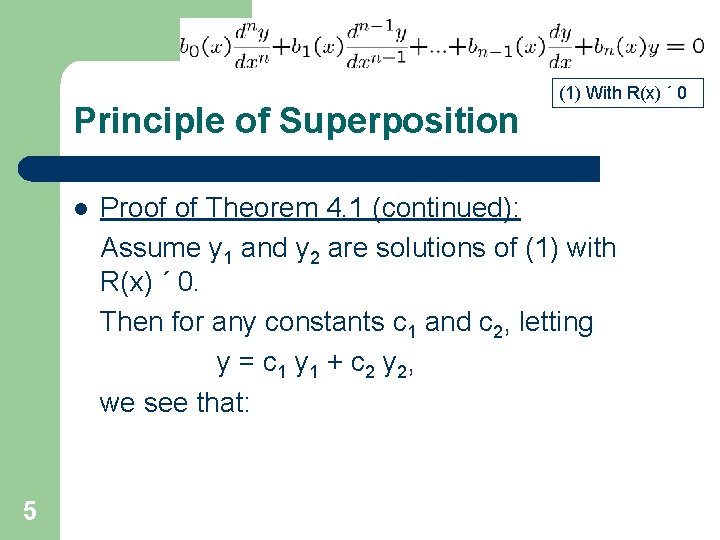

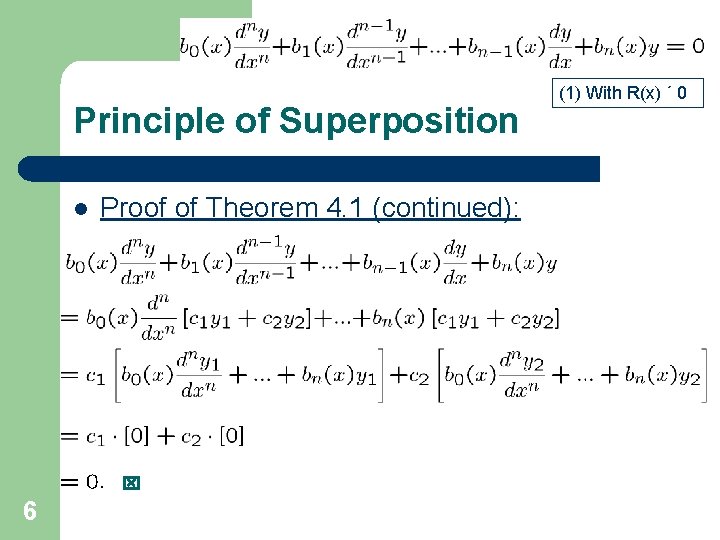

Principle of Superposition l 5 (1) With R(x) ´ 0 Proof of Theorem 4. 1 (continued): Assume y 1 and y 2 are solutions of (1) with R(x) ´ 0. Then for any constants c 1 and c 2, letting y = c 1 y 1 + c 2 y 2, we see that:

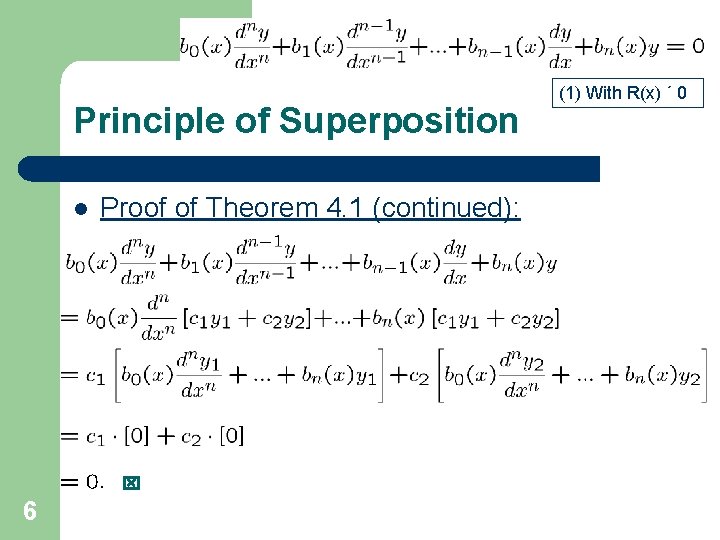

Principle of Superposition l Proof of Theorem 4. 1 (continued): 6 (1) With R(x) ´ 0

4. 2: An Existence and Uniqueness Theorem l l 7 We state without proof, an existence and uniqueness theorem for general linear equations (compare to Theorem 2. 4 for the case when n = 1). A proof for this theorem can be found in Coddington’s An Introduction to Ordinary Differential Equations – see Chapter 6 (beyond the scope of this course).

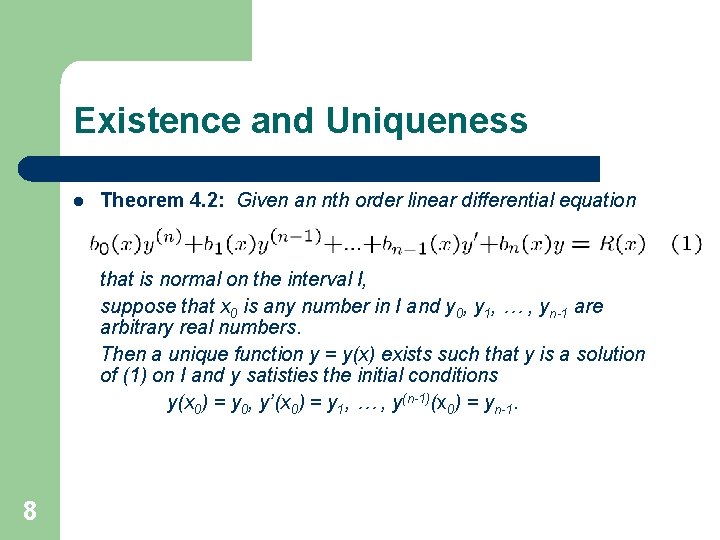

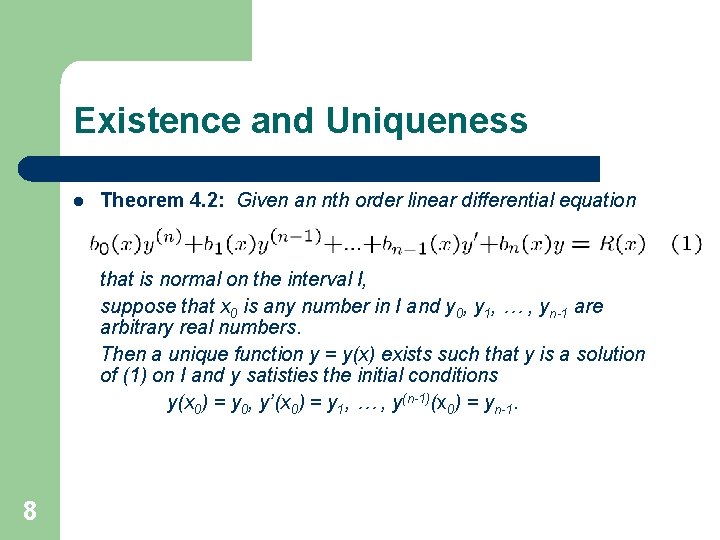

Existence and Uniqueness l Theorem 4. 2: Given an nth order linear differential equation that is normal on the interval I, suppose that x 0 is any number in I and y 0, y 1, … , yn-1 are arbitrary real numbers. Then a unique function y = y(x) exists such that y is a solution of (1) on I and y satisties the initial conditions y(x 0) = y 0, y’(x 0) = y 1, … , y(n-1)(x 0) = yn-1. 8

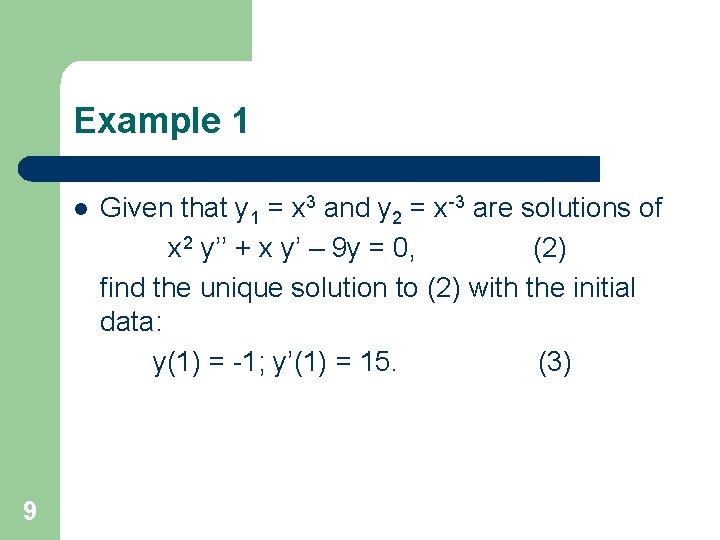

Example 1 l 9 Given that y 1 = x 3 and y 2 = x-3 are solutions of x 2 y’’ + x y’ – 9 y = 0, (2) find the unique solution to (2) with the initial data: y(1) = -1; y’(1) = 15. (3)

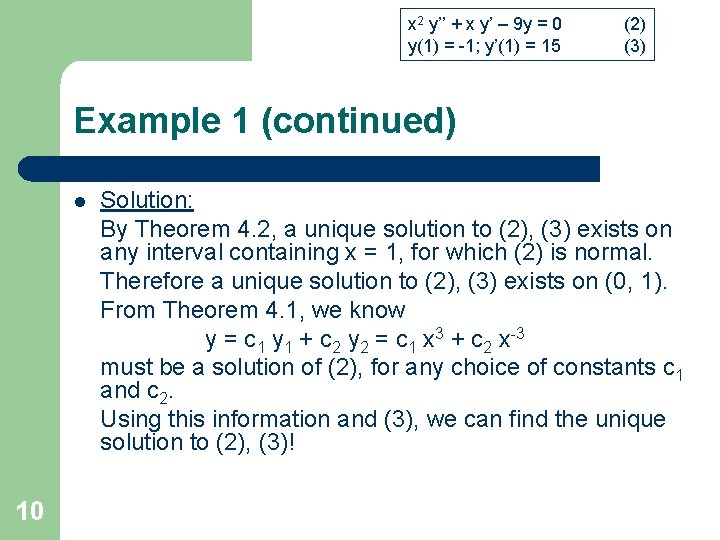

x 2 y’’ + x y’ – 9 y = 0 y(1) = -1; y’(1) = 15 (2) (3) Example 1 (continued) l 10 Solution: By Theorem 4. 2, a unique solution to (2), (3) exists on any interval containing x = 1, for which (2) is normal. Therefore a unique solution to (2), (3) exists on (0, 1). From Theorem 4. 1, we know y = c 1 y 1 + c 2 y 2 = c 1 x 3 + c 2 x-3 must be a solution of (2), for any choice of constants c 1 and c 2. Using this information and (3), we can find the unique solution to (2), (3)!

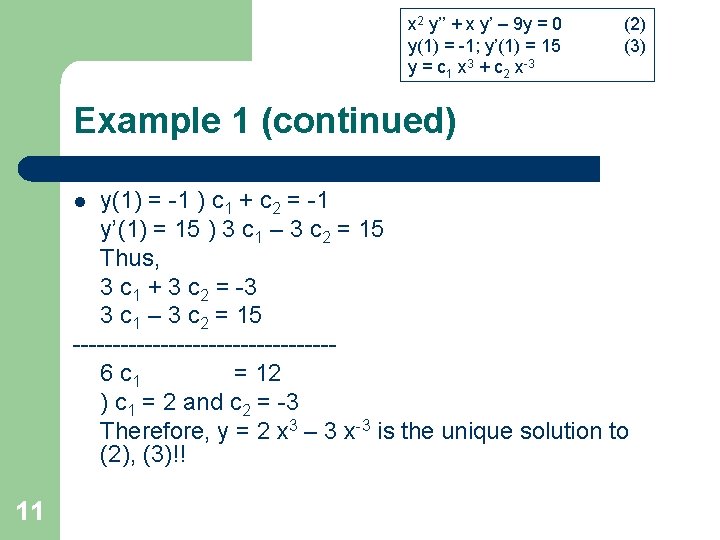

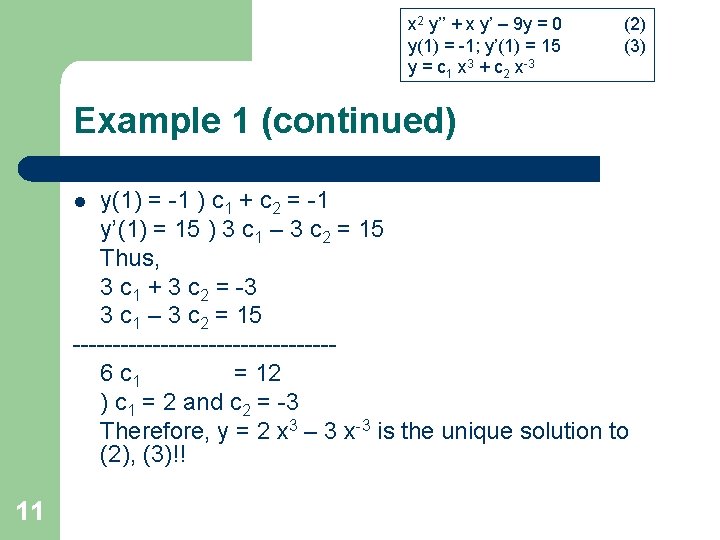

x 2 y’’ + x y’ – 9 y = 0 y(1) = -1; y’(1) = 15 y = c 1 x 3 + c 2 x-3 (2) (3) Example 1 (continued) y(1) = -1 ) c 1 + c 2 = -1 y’(1) = 15 ) 3 c 1 – 3 c 2 = 15 Thus, 3 c 1 + 3 c 2 = -3 3 c 1 – 3 c 2 = 15 ----------------6 c 1 = 12 ) c 1 = 2 and c 2 = -3 Therefore, y = 2 x 3 – 3 x-3 is the unique solution to (2), (3)!! l 11

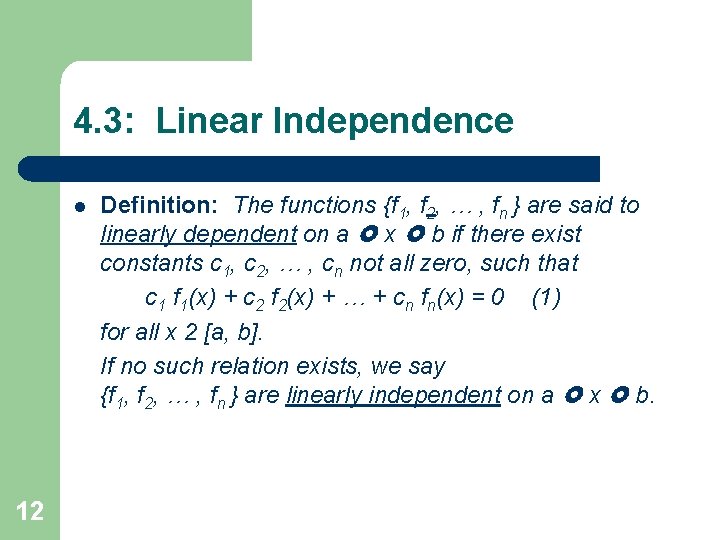

4. 3: Linear Independence l 12 Definition: The functions {f 1, f 2, … , fn } are said to linearly dependent on a x b if there exist constants c 1, c 2, … , cn not all zero, such that c 1 f 1(x) + c 2 f 2(x) + … + cn fn(x) = 0 (1) for all x 2 [a, b]. If no such relation exists, we say {f 1, f 2, … , fn } are linearly independent on a x b.

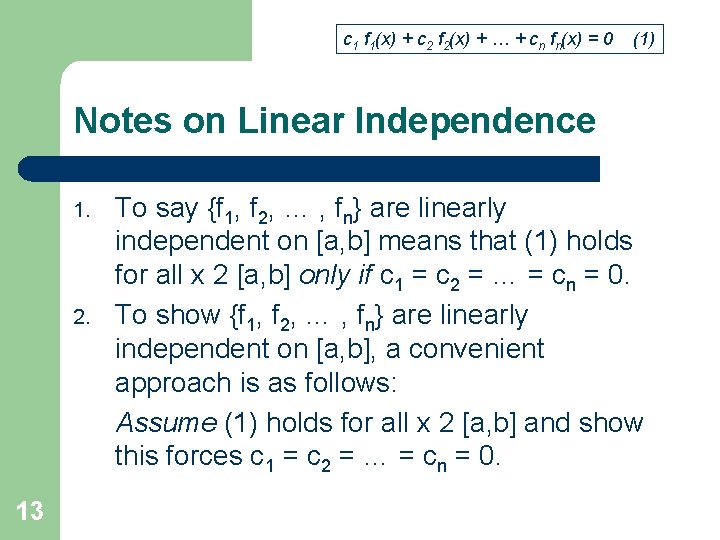

c 1 f 1(x) + c 2 f 2(x) + … + cn fn(x) = 0 (1) Notes on Linear Independence 1. 2. 13 To say {f 1, f 2, … , fn} are linearly independent on [a, b] means that (1) holds for all x 2 [a, b] only if c 1 = c 2 = … = cn = 0. To show {f 1, f 2, … , fn} are linearly independent on [a, b], a convenient approach is as follows: Assume (1) holds for all x 2 [a, b] and show this forces c 1 = c 2 = … = cn = 0.

c 1 f 1(x) + c 2 f 2(x) + … + cn fn(x) = 0 Notes on Linear Independence 3. 4. 14 {f 1, f 2, … , fn} are linearly dependent on [a, b] if and only if at least one of them is a linear combination of the others. {f 1, f 2, … , fn} are linearly independent on [a, b] if and only if none of them is a linear combination of the others. (1)

c 1 f 1(x) + c 2 f 2(x) + … + cn fn(x) = 0 (1) Some Examples l l 15 Example 1: {sin 2 x, cos 2 x, 1} are linearly dependent on any real interval, as sin 2 x + cos 2 x – 1 = 0, for all x. Example 2: {1, x, x 2} are linearly independent on any real interval, since c 1 + c 2 x + c 3 x 2 = 0 for all x 2 [a, b] ) c 1 = c 2 =c 3 = 0 must hold. Reason: Any polynomial of degree two has at most two distinct real roots (Fundamental Theorem of Algebra). Hence, the only way to have c 1 + c 2 x + c 3 x 2 = 0 for all x 2 [a, b] is if the coefficients are all zero.