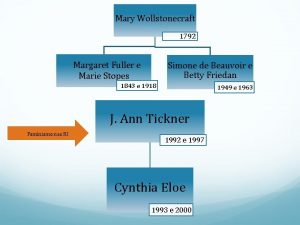

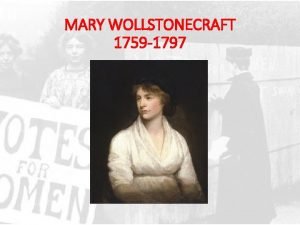

Mary Wollstonecraft The Wrongs of Women 1792 The

- Slides: 74

Mary Wollstonecraft The Wrongs of Women 1792

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Though Mary, a Fiction, was published anonymously, the reader is cued to this rhetorical strategy in the novel’s Advertisement, which states that its heroine-genius is ‘drawn. . . from the original source’, or the author. Ø Thus there are two geniuses represented in the text-the protagonist and the narrator, or the ‘author’ that is implied by the narrator’s style and allusions. Ø Through this narrative method, Mary both depicts in its heroine and enjoins in its reader a sentimental education, or disciplining of subjectivity-the ‘genius’ educating itself.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø “And the old house-keeper told her stories, dead to her, and, at last, taught her to read. Her mother talked of enquiring for a governess when her health would permit, and, in the interim desired her own maid to teach her French. As she had learned to read, she perused with avidity every book that came to her own way, she considered every thing that came under her inspection, and learned to think. ” (p. 8).

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø This ‘genius’ is not only narrated or dramatized in the career of the protagonist, but also implied and exemplified in the character of the narrator as a version of the author. Ø This narrative technique, in its early development by novelists in the 1780 s, would be refined further by Wollstonecraft in her second novel, The Wrongs of Woman, or Maria.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø It would also be developed steadily through the following· century by novelists from Jane Austen to George Eliot to Katherine Mansfield to represent the full affective and intellectual potential of female subjects.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø In a brief Advertisement, Wollstonecraft promised that a subsequent work would examine the laws relating to women in detail; Ø this work would in fact feminist novel, The Wrongs of Woman; or, Maria, while, Rights of Woman was well received and Wollstonecraft attempted to apply her Revolutionary feminism in her personal life, including an unconventional relationship with Joseph Johnson’s friend, the Swiss artist Henry Fuseli.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø [Joseph Johnson (1738 -1809) was an influential 18 thcentury London bookseller and publisher. His publications covered a wide variety of genres and a broad spectrum of opinions on important issues. Johnson is best Wakefield, as well as religious dissenters such as Joseph Priestley, Anne Laetitia Barbaud, Gilbert Wakefield, and George Walker].

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Now her writing projects, interest in the Revolution, and desire to pursue progressive personal relationships all pointed to Paris. Ø At that time the dominant Revolutionary political factions were the moderate and constitutionalist Girondins. French counterparts to people like Wollstonecraft: and her circle.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Furthermore, Paris was full of political tourists, including people Wollstonecraft knew. Ø She set out for Paris in December 1792 and once there joined the British expatriate circle of Johnson’s friend Thomas Christie and soon began a relationship with the American adventurer Gilbert Imlay.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Meanwhile the radical and anti-feminist Jacobin faction seized power, and for her own safety Wollstonecraft registered as Imlay’s wife at the American embassy.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø To earn money, she produced a history and vindication of the Girondin Revolution, published in 1794. Ø In May of that year she bore a daughter, Fanny, but the relationship with Imlay, along with her faith in the Revolution’s direction, was failing.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Imlay moved to London and, attempting reconciliation, Wollstonecraft travelled to Scandinavia with her infant and a woman servant, pursuing money owed to Imlay by business partners. Ø To re-establish her financial independence and literary career, she undertook a book on her travels to be published by Johnson.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø At that time, the travelogue was the second most widely read kind of book after the novel. Ø Travelogues were of several kinds-economic and social description, cultural and artistic studies, political tourism, and self-representation of the author-traveller as ‘man (or occasionally woman) of feeling’. Ø Wollstonecraft’s Letters Written During a Short Residence in Norway, Sweden and Denmark (1795) combined elements of all these.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø On her return from Scandinavia she found Imlay in a liaison with another woman and resolved to move on.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø She resumed editorial work and reviewing for Johnson, re-established earlier friendships, and made new ones. Ø One of these was the anarchist philosopher and novelist, William Godwin (1756 -1836). Ø Within a few months Wollstonecraft and Godwin were lovers and, though both were philosophically and politically opposed to marriage as it was at that time, when Wollstonecraft became pregnant they decided to marry to protect her from public condemnation and consequent loss of literary employment.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø The promise of the Revolution and its potential for promoting the ‘rights of woman’ seemed to be receding rapidly. Ø Undaunted, and to reinvigorate reformist discontent with the system of ‘things as they are’, Wollstonecraft began a feminist novel examining the social injustices of unreformed and unmodernized society as these injustices afflicted women in particular.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Wollstonecraft’s circle now included writers who had taken up the novel with similar aims, believing that the novel could reach readers who would not open a polemical pamphlet or philosophical treatise. Ø These writers developed a fictional form at that time called the philosophical romance, later called the ‘novel of ideas’.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria (92 -131) Ø Wollstonecraft’s The Wrongs of Woman; or, Maria, left incomplete at her death and published by Godwin in 1798, gives this form a specifically Revolutionary feminist turn and takes it further.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø The novel as a whole depicts the ‘wrongs’ of several women. Ø The main story recounts the formation of the young Maria as a mere ‘woman of feeling’ easily duped by the feigned sensibility and courtly gallantry of George Venables, who in fact marries her for her money. Ø After marriage, his genteel vices become evident, especially when he treats his wife as property and offers her to a business friend in exchange for a debt.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Outraged, Maria flees, but after a series of adventures, during which she observes the wrongs of other women, her husband tracks her down, confines her in a private madhouse, and takes her daughter, so that he can control Maria’s property and the daughter’s inheritance. Ø Though imprisoned, Maria and another inmate, Darnford, become lovers, and gain the confidence of their warder Jemima, a former prostitute.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø When the madhouse is unexpectedly abandoned by its proprietor, the inmates escape, but Darnford is sued at law by Venables for alienation of his wife’s affections and when Maria tries to defend her right to choice in a mate, the judge rejects her ‘French principles’ -Revolutionary ideas of equality.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Here the novel breaks off incomplete, though there are several alternative endings: Ø Maria finds Darnford unfaithful, Ø He attempts suicide and dies, Ø She recovers to live in despair, Ø is saved by Jemima and reunited with her daughter.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø The novel’s structure, narrative method, plot, characters, incidents, settings, and use of allusion and reference reinforce its argument that the ‘wrongs of woman’ are not women’s fault but systemic in an unreformed society and state. Ø In structure the novel is a frame narrative containing inserts stories of Maria (Chapters Seven-Fourteen) , Jemima (Chapter Five), and other women. Ø This structure generalizes the novel’s argument, showing that women of all social classes suffer wrongs.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø The intertwined stories imply that, in the state of ‘things as they are’, such wrongs are inevitable and universal. Ø The novel opens in medias res to create suspense and engage the reader, sympathetically describing Maria’s imprisoned situation, then recounting her liaison with Darnford. Ø The love of Maria and Darnford and her loss of her daughter arouse the sympathy of Jemima and spur her to recount her lifetime of wrongs.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Then set into the narrative frame is Maria’s first person manuscript memoir addressed to her absent daughter but read by Darnford and Jemima. Ø The memoir recounts critically, from Maria’s new feminist understanding of herself and society, her narrowly feminine education and social formation for dependent femininity, inevitably leading husband’s exploitation and incarceration of her.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø The novel’s third-person narrative resumes with Maria’s adventures of flight and pursuit, containing imbedded stories recounted to Maria by other women victims of ‘things as they are’, and culminates in Maria’s written declaration of the rights of woman submitted to the court of law (Chapter Seventeen, pp. 170 -174).

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø The turning-point in Maria’s understanding that the ‘wrongs of woman’ are systemic and not peculiar to her, let alone her fault, occurs in what seems a dark moment in her experience of these wrongs.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø When she protests at her husband’s attempt to exchange her sexual services for a debt, he locks her in a room, thereby paradoxically unlocking her feminist understanding of the ‘wrongs of woman’: Ø When left alone, I was a moment or two before I could recollect myself. One scene had succeeded another with such rapidity, I almost doubted whether I was reflecting on a real event. "Was it possible? Was I, indeed, free? " - Yes, free 1 termed myself, when I decidedly perceived the conduct I ought to adopt. How had I panted for liberty, that I would have purchased at any price, but that of my own esteem!’ (p. 144)

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø In Enlightenment thought, are distinct aesthetic and moral categories, gendered masculine and feminine respectively:

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø I rose, and shook myself; opened the window, and methought the air never smelled so sweet. The face of heaven grew fairer as I viewed it, and the clouds seemed to flit away obedient to my wishes, to give my soul, room to expand. I was all soul, and (wild as it may appear) felt as if l could have dissolved in the soft balmy gale that kissed my cheek, or have glided below the horizon on the glowing, descending beams. A seraphic satisfaction animated, without agitating my spirits; and my imagination collected, in visions sublimely terrible, or soothingly beautiful, an immense variety of the endless images, which nature affords, and fancy combines, of the grand fair. (p. 144).

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø The novel’s Revolutionary feminist argument is further reinforced by use of literary and historical allusions and references -a favourite device of the political romancers in Wollstonecrafts circle. Ø Maria’s name, for example, makes a number of such allusions. Ø Maria is Mary (Wollstonecraft), but Maria or Mary was so common a name that it could almost signify ‘everywoman’.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Maria may also be taken as an ironic reference to Mary, mother of Christ, the redeemer of humanity from the transgression of the first, sinning woman, Ø Eve, in the Bible-a narrative that Wollstonecraft reinterpreted in Rights of Woman as illustrating the historic vilification of women by men.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø A recent and politically pertinent reference would be to Marie Roland (1754 -93), centre of the Girondin revolutionaries, guillotined by the Jacobins, and author of a posthumous autobiographical Letter to Impartial Posterity (1795).

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Like the memoir of Wollstonecraft’s Maria, this was a confessional and self-vindicating autobiography, written in prison, and addressed to Roland’s absent daughter. Ø ‘Jemima’ is another ironic biblical reference-to one of Job’s daughters, who were to have equal inheritance with their brothers. Ø Here

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø [Jemima (also written Jemimah, Hebrew: ימימה Yemimah) was the oldest of the three beautiful daughters of Job, named in the Bible as given to him in the later part of his life, after God made Job prosperous again. Jemima's sisters are named as Keziah and Keren-Happuch. Job's sons, in contrast, are not named. Jemima, along with her sisters, was described as the most beautiful women in the land. Also, unusually and in common with her sisters, Jemima was granted an inheritance by her father, with her brothers as might have been expected (Job 42: 15). Apart from these brief references at the end of the Book of Job, Jemima is not mentioned elsewhere in the Bible. The name Jemima means "turtledove“].

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø George Venables, Maria’s husband, resembles in and vices George, Prince of Wales, much in the news while Wollstonecraft was writing her novel because of his debts, moral decadence, and highly publicized conflict with his wife, whom he wanted to have confined as a madwoman and whom he restricted from seeing their daughter (born in January 1796).

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Darnford echoes Darnley (1562 -1612), the lover and eventual betrayer of Mary, Queen of Scots-a familiar Sentimental historical figure for the woman of excessive feeling victimized by political intrigue.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Most obviously, Maria begins to fall in love with Darnford before they even meet through reading his comments in a copy of Rousseau’s Sentimental novel of social criticism, Julie; ou, la nouvelle Héloise- widely regarded by counter-Revolutionaries as a morally and politically inflammatory work. Ø This reference encourages reading Wollstonecraft’s novel in relation to Rousseau’s representation of passionate love as an emancipatory subjective absolute that is denied to women in an unjust, sexist society-as Maria points out in her address to the court.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø A similarly suggestive reference (p. 128) is to Nicholas Rowe’s she-tragedy The Fair Penitent (1703), in which the heroine, Calista, declares her right to take a lover or husband by her own rather than by her family’s or society’s choice. Ø The play also featured the archetypal male seducer and betrayer, Lothario, and was often restaged in Wollstonecraft’s day, with her friend, the famous tragedian Sarah Siddons, as Calista.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Even a passing reference, such as to John Dryden’s poem ‘Guiscard and Sigismunda’ (p. 79), contributes to the feminist theme, as the poem contains a stirring defence of women’s right to independence. Ø Together, such literary allusions suggest to the reader a canon of texts with feminist viewpoints. Ø Like the other novelist in her circle, too, Wollstonecraft reinforced her use of historical and literary allusions with research of various kinds into the “wrongs of woman”.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Instances of such research include the laws of marriage, divorce, marital property, and child custody designed to keep women the property of men; Ø the operation of the poor laws and welfare provision, which bear heavily on women; Ø corrupt management of public and private institutions such as hospitals and madhouses;

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø the forced conscription of soldiers and sailors, affecting their wives and children; Ø and even the precise, exploitative wages for particular kinds of women’s labour, such as clothes washing. Ø To observe an actual madhouse, Wollstonecraft visited Bedlam Hospital for the insane with Godwin and Joseph Johnson.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Thus the novel is in effect the sequel, promised in the author’s Advertisement to A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, dealing with ‘the laws relative to women’, for the novel makes clear that the ‘wrongs of woman’ are based on sexist property laws and the economic exploitation of women’s bodies and labour. Ø As in Rights of Woman, Wollstonecraft relates the legal condition of women to such larger issues as corrupt electoral politics, parliamentary representation, and government.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Finally, as in her earlier novel, Wollstonecraft again gave her fiction greater rhetorical force by incorporating autobiographical material. Ø As with Mary, A Fiction, most readers of The Wrongs of Woman would not know or need to know if material was taken from the author’s life or invented. Ø More important was that certain material be treated so as to convey a sense of autobiographic authenticity and hence authority--a conviction that the narrator-author knows whereof she speaks.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø In The Wrongs of Woman such authenticity works in two converging ways-through the narrator and through the protagonist. Ø As in Mary, use of free indirect discourse, or reported inward speech and thought, creates sympathy between third-person narrator and protagonist.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø In The Wrongs of Woman, this sympathy is established from the opening pages in the narrator’s representation of Maria’s situation, and especially her maternal feelings, enhanced by the way the novel starts in media res, creating suspense and interest, and continues through much of the rest of the novel (Chapters One--Four, Six, Fifteen. Seventeen). Ø Such close identification of narrator and protagonist implies concordance of experience and knowledge between them, and aims to engage the reader, female or male, in this relationship.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø This engagement has a ‘philosophical’ aim, however. For example, after representing Maria’s situation and maternal feelings in the opening paragraphs, the narrator goes on to represent Maria reflecting· on or theorizing her situation and feelings to reach a feminist understanding of them as the consequences of systemic injustice to women (pp. 69 -70). Ø From the opening pages of the novel and throughout the first four chapters, narrator and protagonist display a feminist understanding of the ‘wrongs of woman’ -an understanding that the reader is encouraged to participate in through the narrative method of free indirect discourse.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Maria’s inset story of her life (Chapters Seven-Fourteen) then recounts how she arrived understanding, at the moment when she feels free, because subjectively free, even though confined by her husband, in the passage quoted earlier. Ø Thus Maria’s inset-autobiography recounts the achievement of a feminist consciousness that is also displayed in both protagonist and narrator in the novel’s opening chapters in two ways:

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø through vicarious of wrongs of woman and progress to feminist understanding of them in Maria’s autobiography (and to some extent in Jemima’s) Ø and through identification with the character of the narrator, as a version of the author in the text. Ø Such invoking of authority from personal experience converges with the novel’s use of research and historical and literary allusions to create not only a dense representation of the ‘wrongs of woman’ in all classes, past and present, but also a specifically feminist knowledge.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø The culmination of the protagonist’s acquisition of this knowledge is her feminist manifesto, submitted the court and jury near the end of the novel, and recalling and subsuming Wollstonecraft’s own Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Ø As in Rights of Woman, the novel presents such experience and knowledge, which are usually restricted to the private and domestic sphere, as also legitimate and potentially transformative for the public, political sphere.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Conclusion Ø Maria itself may be included in this revolutionary feminine-feminist discourse, since novels were often regarded at the time as a ‘feminine’ genre. Ø Through these devices, Wollstonecraft aimed to create a new, feminist form of the novel for her time, designed to convey powerfully, to both men and women readers, the relationship between large social, political, and economic structures and the ‘wrongs of woman’ of different classes in everyday life.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø Wrongs of Woman may seem problematic, however, because of its uncertain resolution. Ø Wollstonecraft did not live to complete her novel, and left several sketched endings (pp. 175 -177). Ø The longest of these seems to leave the protagonist, her daughter, and her follower-servant-friend as a small sisterhood of different generations and classes, facing an uncertain future with a feminist understanding of ‘things as they are’.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø No matter which of the sketched endings Wollstonecraft might finally have preferred, however, it is clear that, as the novel’s title indicates, its purpose is protest more than a programme for reform. Ø Ø It aims to make readers recognize-and resent-the ‘wrongs of woman’ and the unjust system of ‘things as they are’ that causes them. Ø This is the necessary first step towards systemic change and, as with Mary, the novel’s open ending leaves readers to imagine how such change might be brought

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø The Fate of Revolutionary Feminism Ø What more Wollstonecraft’s novel, if completed, might have said, what more it might have achieved in effecting change, and what more Wollstonecraft might have become, had she lived, were overtaken by events. Ø The accidents of mortality overtook Wollstonecraft herself, and the counter-Revolutionary reaction and subsequent emergence of political liberalism and cultural Romanticism overtook Wollstonecraft’s Revolutionary feminism and her novel.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø The Fate of Revolutionary Feminism Ø Before she could complete and publish Wrongs of Woman, Wollstonecraft died in September 1797 from complications of childbirth, after bearing another daughter, named Marylater Mary Shelley. Ø Wollstonecraft’s grief-stricken husband published his edited version of the novel, along with some letters and other fragments and his biography of her, early in 1798.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø The Fate of Revolutionary Feminism Ø Political conservatives seized the occasion to pillory Wollstonecraft and her work for what the judge in Wrongs of Woman called ‘French principles’. Ø Moral conservatives rejoiced in her death as divine punishment for a sinful life and unfeminine writings. Ø Wollstonecraft and her work remained under a cloud and did not re-enter public discussion until suffragist feminism of the mid-nineteenth century.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø The Fate of Revolutionary Feminism Ø The feminist movement of the 1960 s saw her as a pioneer ‘liberal’ feminist concerned to establish women’s capacity for sovereign subjectivity and thus civil and political rights, and produced new biographies and editions of her work. Ø Since then, feminist psychoanalytic critics have examined Wollstonecraft’s life and writings as instances of the psycho -social ‘wrongs of woman’ and resistance to them.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø The Fate of Revolutionary Feminism Ø Historians of political theory have examined her work as political philosophy. Historicist and materialist feminist critics have sought to situate her in historical, social, cultural, political, and economic contexts. Ø Wollstonecraft and her writings remain without closure, still open to different readings and the recuperation of their revolutionary potential.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø The Fate of Revolutionary Feminism Ø Wollstonecraft’s life and writings as instances of the psycho -social ‘wrongs of woman’ and resistance to them. Ø Historians of political theory have examined her work as political philosophy. Historicist and materialist feminist critics have sought to situate her in historical, social, cultural, political, and economic contexts.

Ø The Wrongs of Woman or, Maria Ø The Fate of Revolutionary Feminism Ø Wollstonecraft and her writings remain without closure, still open to different readings and the recuperation of their revolutionary potential. Ø The End

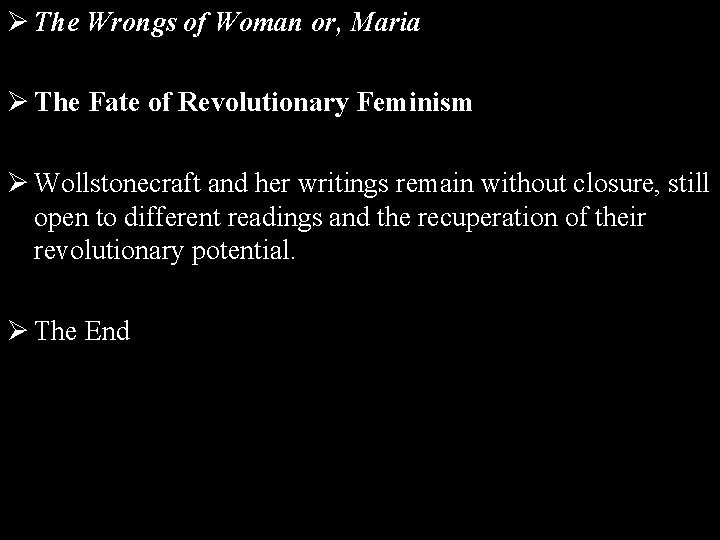

Jean d’Arc – 1412 -1431

R Rouen – Statue de Jeanne d’Arc sur l'emplacement du bucher

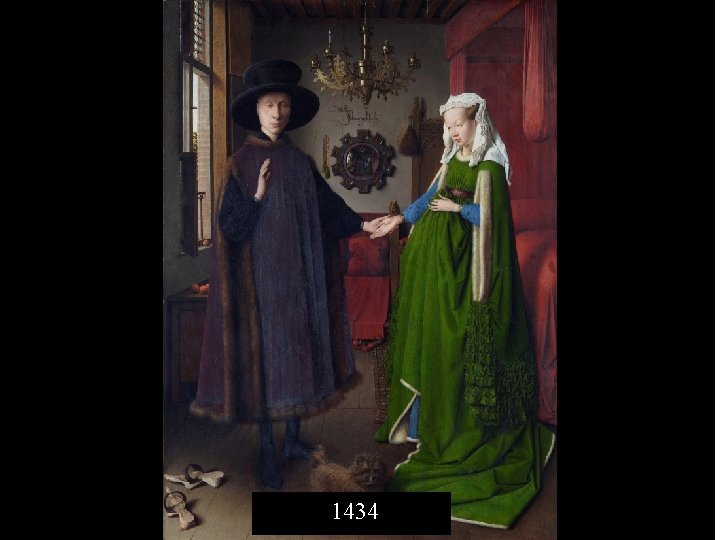

1434

Isabelle of Bavaria 1370 -1435

F

Notes from Gary Kelly

Mary wollstonecraft mary a fiction

Mary wollstonecraft mary a fiction Mary wollstonecraft daughter

Mary wollstonecraft daughter Dr. manuel dy jr quotes

Dr. manuel dy jr quotes Mary wollstonecraft

Mary wollstonecraft Mary quiceno md

Mary quiceno md Olympe de gouges beliefs

Olympe de gouges beliefs Bakit mahalaga ang pakikilahok sa lipunan

Bakit mahalaga ang pakikilahok sa lipunan Mary wollstonecraft

Mary wollstonecraft First computer invented

First computer invented Mount unzen eruption 1792 facts

Mount unzen eruption 1792 facts Pasal 1792 bw

Pasal 1792 bw Radical revolution 1792-94

Radical revolution 1792-94 Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu

Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu Diễn thế sinh thái là

Diễn thế sinh thái là Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Slidetodoc

Slidetodoc V. c c

V. c c Phép trừ bù

Phép trừ bù Chúa yêu trần thế alleluia

Chúa yêu trần thế alleluia Hổ đẻ mỗi lứa mấy con

Hổ đẻ mỗi lứa mấy con đại từ thay thế

đại từ thay thế Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra

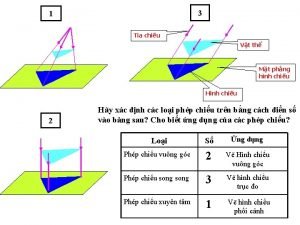

Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau

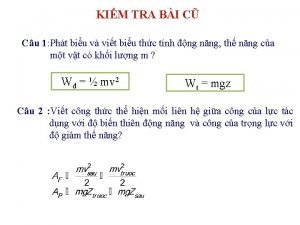

Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau Cong thức tính động năng

Cong thức tính động năng Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em

Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em Thế nào là mạng điện lắp đặt kiểu nổi

Thế nào là mạng điện lắp đặt kiểu nổi Các loại đột biến cấu trúc nhiễm sắc thể

Các loại đột biến cấu trúc nhiễm sắc thể Lời thề hippocrates

Lời thề hippocrates Bổ thể

Bổ thể Vẽ hình chiếu đứng bằng cạnh của vật thể

Vẽ hình chiếu đứng bằng cạnh của vật thể độ dài liên kết

độ dài liên kết Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng từ đua

Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng từ đua Khi nào hổ con có thể sống độc lập

Khi nào hổ con có thể sống độc lập điện thế nghỉ

điện thế nghỉ Biện pháp chống mỏi cơ

Biện pháp chống mỏi cơ Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ

Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ Chó sói

Chó sói Thiếu nhi thế giới liên hoan

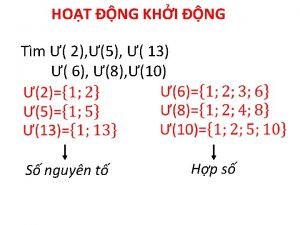

Thiếu nhi thế giới liên hoan Số nguyên tố là số gì

Số nguyên tố là số gì Fecboak

Fecboak Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Một số thể thơ truyền thống

Một số thể thơ truyền thống Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất Sơ đồ cơ thể người

Sơ đồ cơ thể người Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Hát kết hợp bộ gõ cơ thể

Hát kết hợp bộ gõ cơ thể đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ

đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ Mật thư anh em như thể tay chân

Mật thư anh em như thể tay chân Tư thế worms-breton

Tư thế worms-breton ưu thế lai là gì

ưu thế lai là gì Thẻ vin

Thẻ vin Thơ thất ngôn tứ tuyệt đường luật

Thơ thất ngôn tứ tuyệt đường luật Cái miệng nó xinh thế

Cái miệng nó xinh thế Greenville women giving

Greenville women giving Waist circumference metabolic syndrome

Waist circumference metabolic syndrome Lesson 3 the byzantine empire

Lesson 3 the byzantine empire Define women entrepreneurs.

Define women entrepreneurs. For women

For women What is wad in gender

What is wad in gender Poker should not be played in a house with women

Poker should not be played in a house with women Women's rights

Women's rights Chapter 11 the nurse's role in women's healthcare

Chapter 11 the nurse's role in women's healthcare Difference between mens and womens soccer

Difference between mens and womens soccer Educate women

Educate women Napoleonic code women

Napoleonic code women Tall women

Tall women Pinewood ajax

Pinewood ajax Ministry of women and child development logo

Ministry of women and child development logo Young women's preparatory academy uniform

Young women's preparatory academy uniform Hypothyroidism complications

Hypothyroidism complications Spartan women rights

Spartan women rights Borrego dental insurance

Borrego dental insurance Paradigm shift from women studies to gender studies

Paradigm shift from women studies to gender studies 5 days of sample menus for pregnant women

5 days of sample menus for pregnant women