Marsha M Linehan Ph D ABPP Born May

Marsha M. Linehan Ph. D. , ABPP Born May 5, 1943 Professor, Department of Psychology Director, Behavioral Research and Therapy Clinics University of Washington

Developer of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)

O Her childhood, in Tulsa, Okla. , provided few clues. An excellent student from early on, a natural on the piano, she was the third of six children of an oilman and his wife, an outgoing woman who juggled child care with the Junior League and Tulsa social events.

O People who knew the Linehan’s at that time remember that their precocious third child was often in trouble at home, and Dr. Linehan recalls feeling deeply inadequate compared with her attractive and accomplished siblings. But whatever currents of distress ran under the surface, no one took much notice until she was bedridden with headaches in her senior year of high school.

O Her younger sister, Aline Haynes, said: “This was Tulsa in the 1960 s, and I don’t think my parents had any idea what to do with Marsha. No one really knew what mental illness was. ”

Marsh Linehan herself suffers from Borderline Personality Disorder

O “Marsha Linehan arrived at the Institute of Living on March 9, 1961, at age 17, and quickly became the sole occupant of the seclusion room on the unit known as Thompson Two, for the most severely ill patients. The staff saw no alternative: The girl attacked herself habitually, burning her wrists with cigarettes, slashing her arms, her legs, her midsection, using any sharp object she could get her hands on. O The seclusion room, a small cell with a bed, a chair and a tiny, barred window, had no such weapon. Yet her urge to die only deepened. So she did the only thing that made any sense to her at the time: banged her head against the wall and, later, the floor. Hard. ” (NY Times 2011)

O Doctors gave her a diagnosis of schizophrenia; dosed her with Thorazine, Librium and other powerful drugs, as well as hours of Freudian analysis; and strapped her down for electroshock treatments, 14 shocks the first time through and 16 the second, according to her medical records. Nothing changed, and soon enough the patient was back in seclusion on the locked ward.

O During her two years and three months at the Institute of Living, Marsha was at times, placed in complete isolation for months at a time. Nothing seemed to help. She cut and burned herself, banged her head on the walls and floor and attempted to commit suicide, all the while breaking rules and trying to escape. The more the staff tried, the worse she became until they finally concluded the best they could do for Marsha was keep her under 24/7 observation to ensure she didn’t kill herself.

O “My whole experience of these episodes was that someone else was doing it; it was like ‘I know this is coming, I’m out of control, somebody help me; where are you, God? ’ ” she said. “I felt totally empty, like the Tin Man; I had no way to communicate what was going on, no way to understand it. ” ~ Marsha Linehan NYTimes

O A discharge summary, dated May 31, 1963, noted that “during 26 months of hospitalization, Miss Linehan was, for a considerable part of this time, one of the most disturbed patients in the hospital. ” O A verse the troubled girl wrote at the time reads: They put me in a four-walled room But left me really out My soul was tossed somewhere askew My limbs were tossed here about ~ M. M. L.

O It was in that isolation room that Marsha, in the depths of despair and suffering, cried for God to help her. Then she had a transcendent moment. Marsha made a solemn vow that she would get herself out of the hell she was in and then come back and help others get out as well. And that’s exactly what she did.

Marsha, Marsha… Linehan graduated cum laude from Loyola University, Chicago in 1968 with a B. S. in psychology. She earned an M. A. in 1970 and a Ph. D. in 1971

O “She was very creative with people. I saw that right away, ” said Gerald C. Davison, who in admitted Dr. Linehan into a postdoctoral program in behavioral therapy at Stony Brook University.

O It took years of study in psychology — she earned a Ph. D. at Loyola in 1971 — before she found an answer. On the surface, it seemed obvious: She had accepted herself as she was. She had tried to kill herself so many times because the gulf between the person she wanted to be and the person she was left her desperate, hopeless, and deeply homesick for a life she would never know. That gulf was real, and unbridgeable.

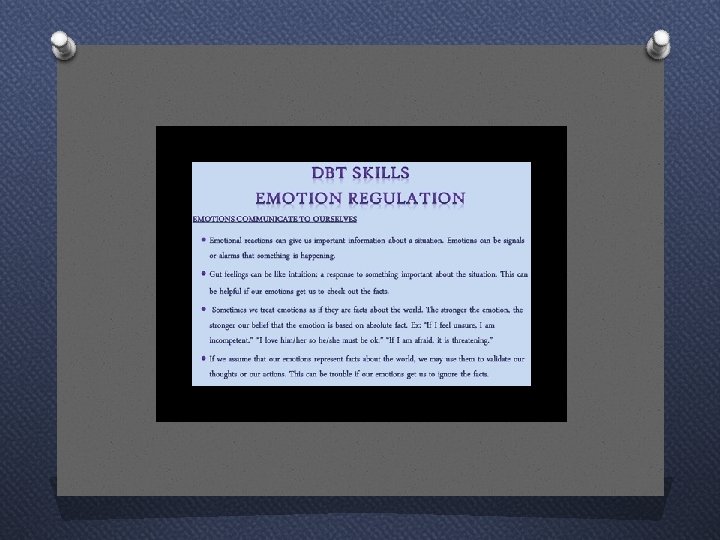

Radical Acceptance O That basic idea ~ radical acceptance ~ became increasingly important as she began working with patients, first at a suicide clinic in Buffalo and later as a researcher. Yes, real change was possible. The emerging discipline of behaviorism taught that people could learn new behaviors — and that acting differently can in time alter underlying emotions from the top down.

O Yet even as she climbed the academic ladder, moving from the Catholic University of America to the University of Washington in 1977, she understood from her own experience that acceptance and change were hardly enough. During those first years in Seattle she sometimes felt suicidal while driving to work; even today, she can feel rushes of panic, most recently while driving through tunnels. She relied on therapists herself, off and on over the years, for support and guidance.

O She chose to treat people with a diagnosis that she would have given her young self: borderline personality disorder, a poorly understood condition characterized by neediness, outbursts and self destructive urges, often leading to cutting or burning. In therapy, borderline patients can be terrors — manipulative, hostile, sometimes ominously mute, and notorious for storming out threatening suicide.

O Dr. Linehan found that the tension of acceptance could at least keep people in the room: patients accept who they are, that they feel the mental squalls of rage, emptiness and anxiety far more intensely than most people do. In turn, therapist accepts that given all this, cutting, burning and suicide attempts make some sense.

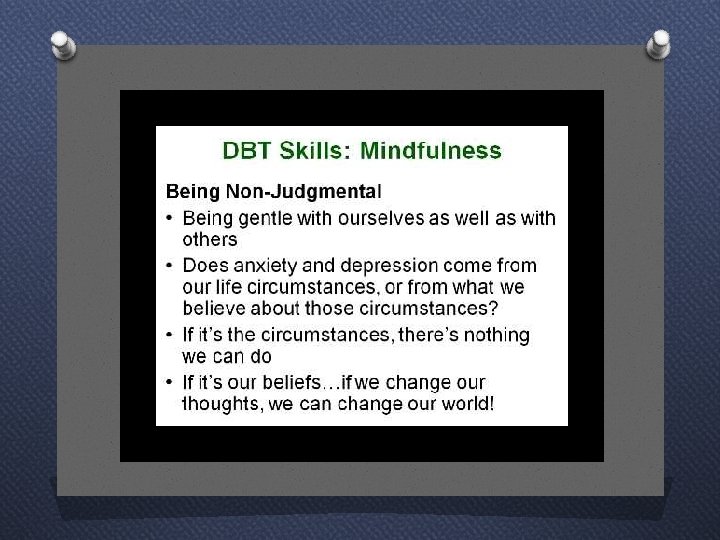

O Dr. Linehan’s own emerging approach to treatment ~ now called dialectical behavior therapy, or D. B. T. ~ would also have to include day to day skills. A commitment means very little, after all, if people do not have the tools to carry it out. She borrowed some of these from other behavioral therapies and added elements, like opposite action, in which patients act opposite to the way they feel when an emotion is inappropriate; and mindfulness meditation, a Zen

Marsha explains DBT https: //youtu. be/V 1 GBv. PVv. Oh. A

O Line han was trained in spir i tual direc tions under Ger ald May and Tilden Edwards and is an asso ciate Zen teacher in both the Sanbo Kyodan School under Willigis Jaeger Roshi as well as in the Dia mond Sangha (USA).

Marsha discusses Mindfulness in DBT O https: //youtu. be/MXxat. Fo. Sbe. Y

She teaches mind ful ness via work shops and retreats for health care providers.

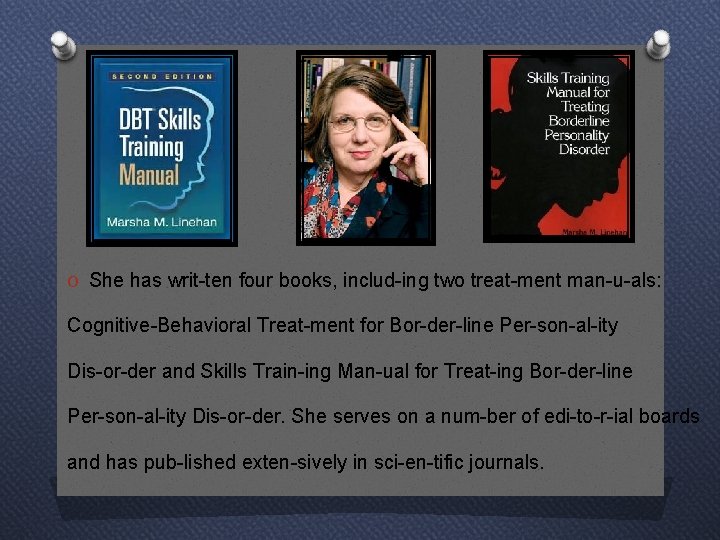

O She has writ ten four books, includ ing two treat ment man u als: Cognitive Behavioral Treat ment for Bor der line Per son al ity Dis or der and Skills Train ing Man ual for Treat ing Bor der line Per son al ity Dis or der. She serves on a num ber of edi to r ial boards and has pub lished exten sively in sci en tific journals.

O Line han is founder of Behav ioral Tech LLC, a behav ioral tech nol ogy trans fer group. She is also founder of Behav ioral Tech Research, Inc. , a com pany that devel ops inno v a tive on line and mobile tech nolo gies to dis sem i nate science based behav ioral treat ments for men tal disorders.

O Marsha Linehan, Ph. D. initially founded Behavioral Tech, LLC in 1997 in response to the growing demand for training in Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT®). In 1998 Behavioral Tech’s 's Research and Development (R&D) department began developing and evaluating training methods to make training accessible, affordable, effective, and efficient. In January 2004, with the growth of the organization, The R&D department became Behavioral Tech Research Inc. , a separate for profit entity owned by Dr. Marsha Linehan. Today, Behavioral Tech Research uses information technology and e learning to develop innovative methods of training mental health providers in evidence based practices.

O She has received sev eral awards rec og niz ing her clin i cal and research con tri bu tions to the study and treat ment of sui ci dal behav iors, includ ing the Louis I. Dublin Award for Life time Achieve ment in the Field of Sui cide, the Dis tin guished Research in Sui cide Award (Amer i can Foun da tion of Sui cide Pre ven tion), and the cre ation of the Mar sha Line han Award for Out stand ing Research in the Treat ment of Sui ci dal Behav ior estab lished by the Amer i can Asso ci a tion of Sui ci dol ogy.

O She is the past president of both the Asso ci a tion for the Advance ment of Behav ior Ther apy and of the Soci ety of Clin i cal Psy chol ogy, Divi sion 12, Amer i can Psy cho log i cal Asso ci a tion. She is a fel low of the Amer i can Psy cho log i cal Asso ci a tion and the Amer i can Psy chopatho log i cal Asso ci a tion and is a diplo mat of the Amer i can Board of Behav ioral Psychology.

O She has also been rec og nized for her clin i cal research includ ing the Dis tin guished Sci en tist Award from the Soci ety for a Sci ence of Clin i cal Psy chol ogy, the award for Dis tin guished Sci en tific Con tri bu tions to Clin i cal Psy chol ogy (Soci ety of Clin i cal Psy chol ogy, ) and awards for Dis tin guished Con tri bu tions to the Prac tice of Psy chol ogy (Amer i can Asso ci a tion of Applied and Pre ven tive Psy chol ogy) and for Dis tin guished Con tri bu tions for Clin i cal Activ i ties, (Asso ci a ti for the Advance ment of Behav ior Therapy).

O Line han is the founder and the con vener of both the Sui cide Strate gic Plan ning Group and the DBT Strate gic Plan ning Group. Both groups meet annu ally or bi annually at the Uni ver sity of Wash ing ton.

O Most remarkably, perhaps, Dr. Linehan has reached a place where she can stand up and tell her story, come what will. “I’m a very happy person now, ” she said in an interview at her house near campus, where she lives with her Peruvian adopted daughter, Geraldine, and "Geri’s husband, Nate. “I still have ups and downs, of course, but I think no more than anyone else. ” O Presentation by: Dhani Toney Sullivan 2015

- Slides: 37