Markov Properties of Directed Acyclic Graphs Peter Spirtes

- Slides: 50

Markov Properties of Directed Acyclic Graphs Peter Spirtes

Outline Bayesian Networks Simplicity and Bayesian Networks Causal Interpretation of Bayesian Networks Greedy Equivalence Search 2

Outline Bayesian Networks Simplicity and Bayesian Networks Causal Interpretation of Bayesian Networks Greedy Equivalence Search 3

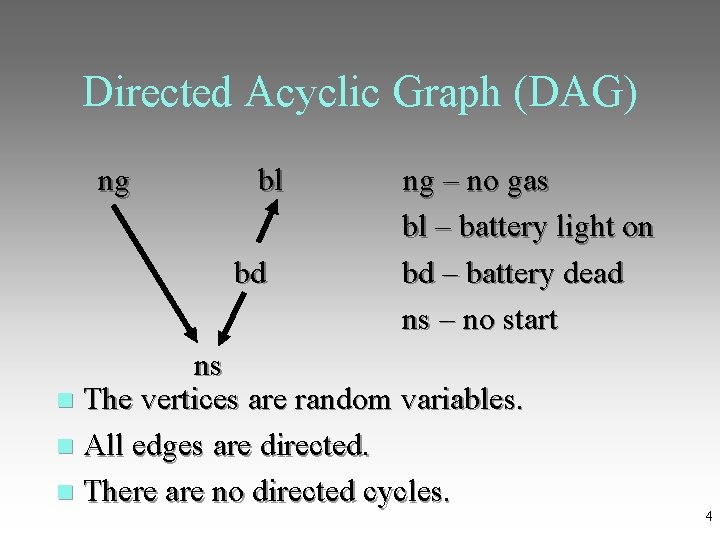

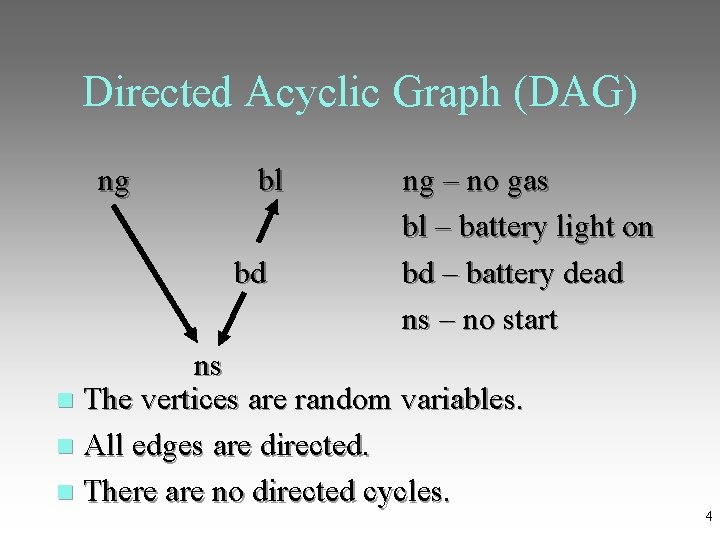

Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) ng bl ng – no gas bl – battery light on bd – battery dead ns – no start ns The vertices are random variables. All edges are directed. There are no directed cycles. 4

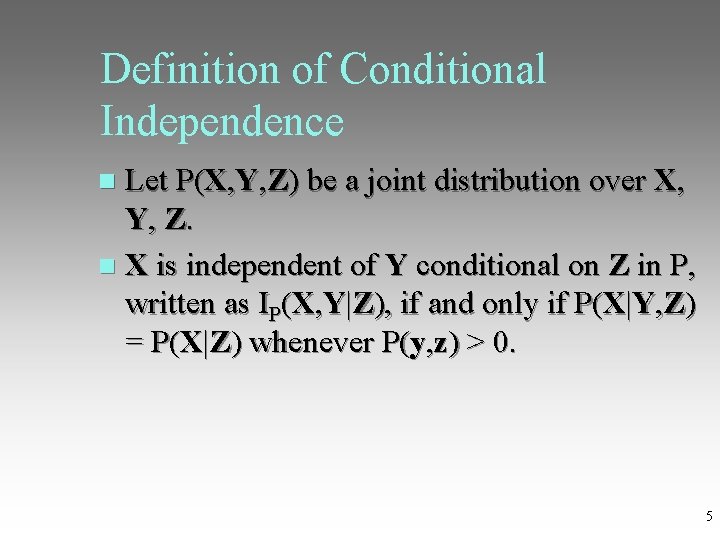

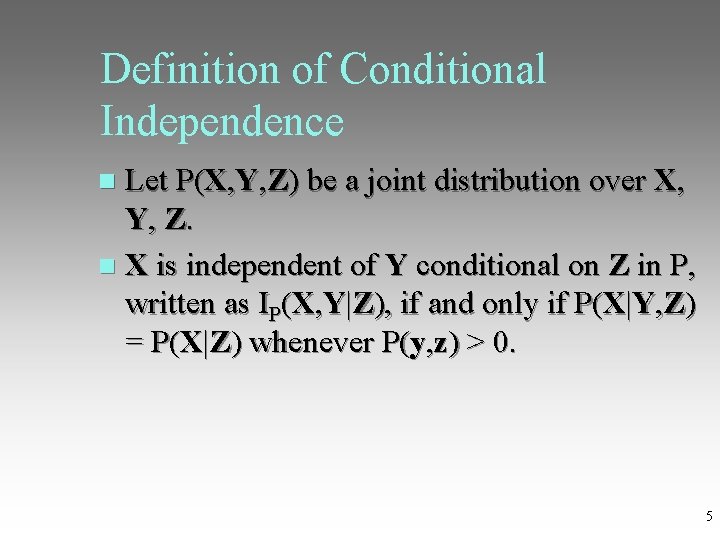

Definition of Conditional Independence Let P(X, Y, Z) be a joint distribution over X, Y, Z. X is independent of Y conditional on Z in P, written as IP(X, Y|Z), if and only if P(X|Y, Z) = P(X|Z) whenever P(y, z) > 0. 5

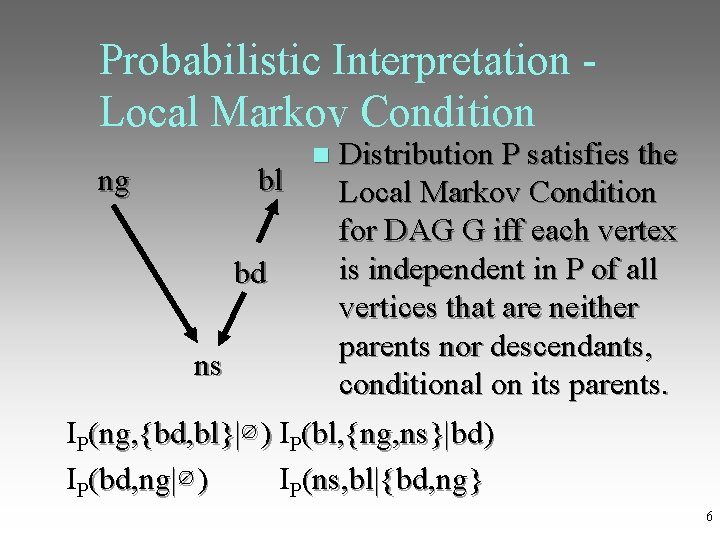

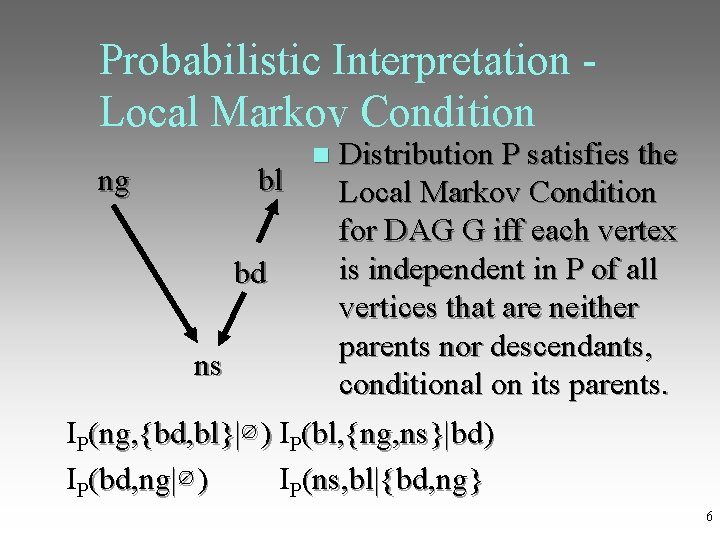

Probabilistic Interpretation - Local Markov Condition Distribution P satisfies the ng bl Local Markov Condition for DAG G iff each vertex is independent in P of all bd vertices that are neither parents nor descendants, ns conditional on its parents. IP(ng, {bd, bl}|∅ ) I ) P(bl, {ng, ns}|bd) IP(bd, ng|∅ ) I ) P(ns, bl|{bd, ng} 6

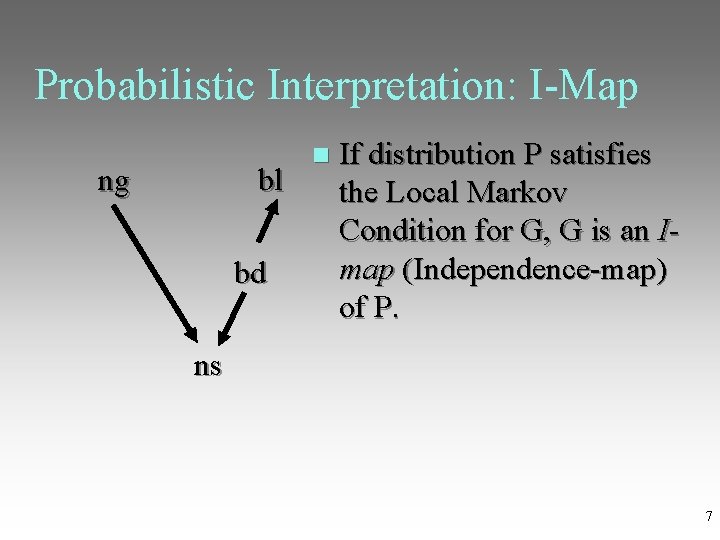

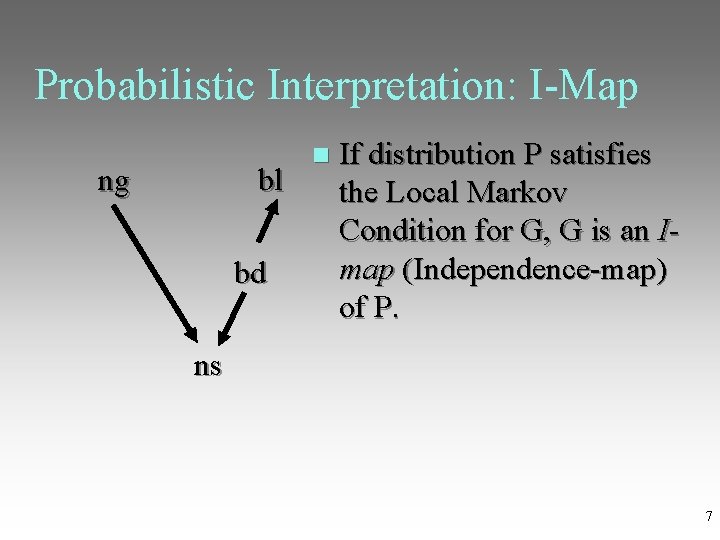

Probabilistic Interpretation: I-Map If distribution P satisfies ng bl the Local Markov Condition for G, G is an Imap (Independence-map) bd of P. ns 7

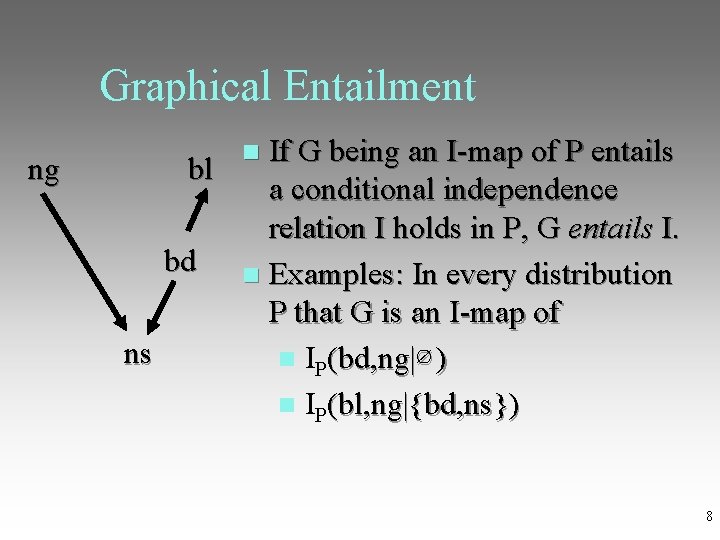

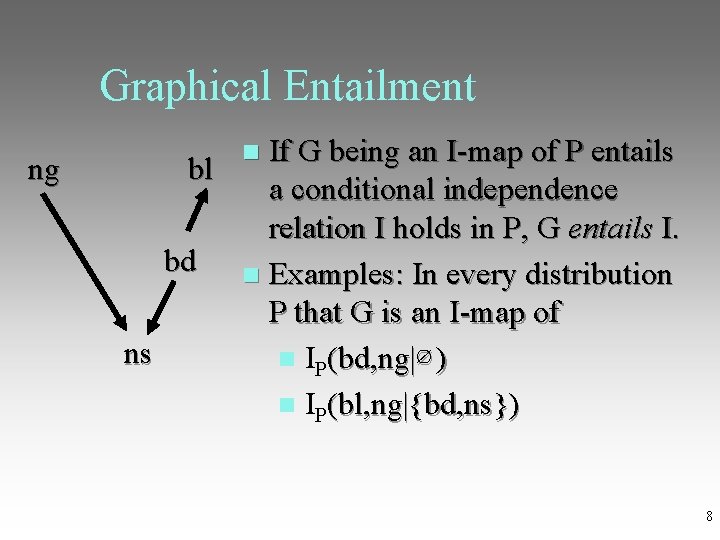

Graphical Entailment If G being an I-map of P entails ng bl a conditional independence relation I holds in P, G entails I. bd Examples: In every distribution P that G is an I-map of ns IP(bd, ng|∅ ) IP(bl, ng|{bd, ns}) 8

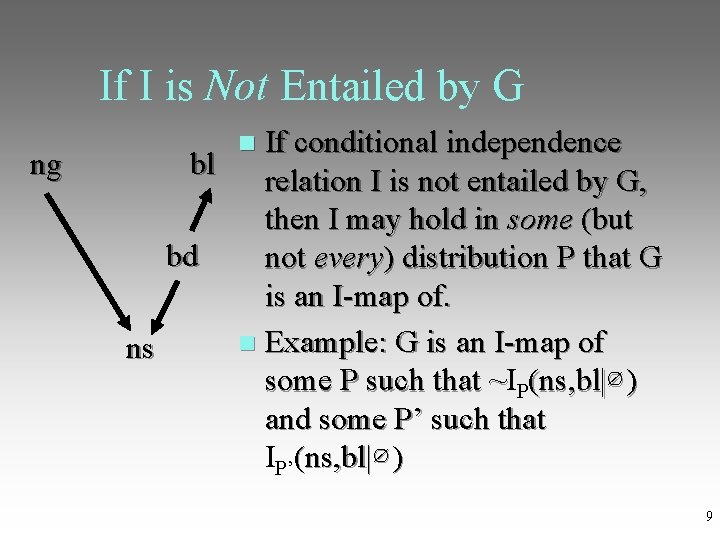

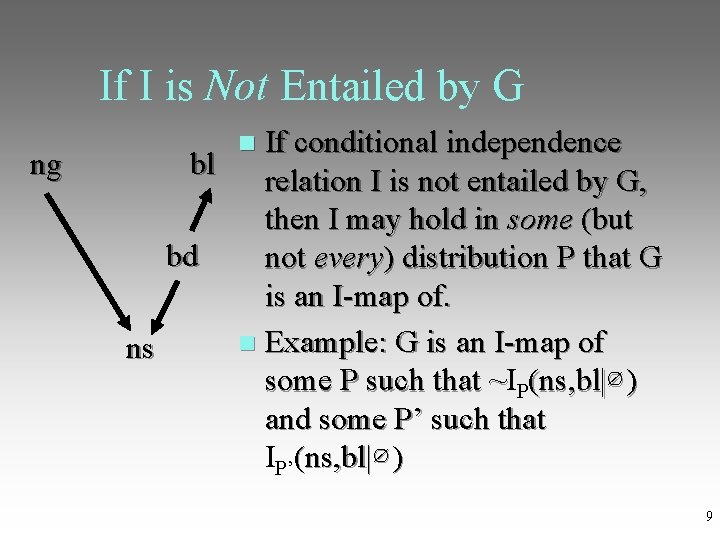

If I is Not Entailed by G If conditional independence ng bl relation I is not entailed by G, then I may hold in some (but bd not every) distribution P that G is an I-map of. Example: G is an I-map of ns some P such that ~I some P such that ~ P(ns, bl|∅ ) and some P’ such that IP’(ns, bl|∅ ) 9

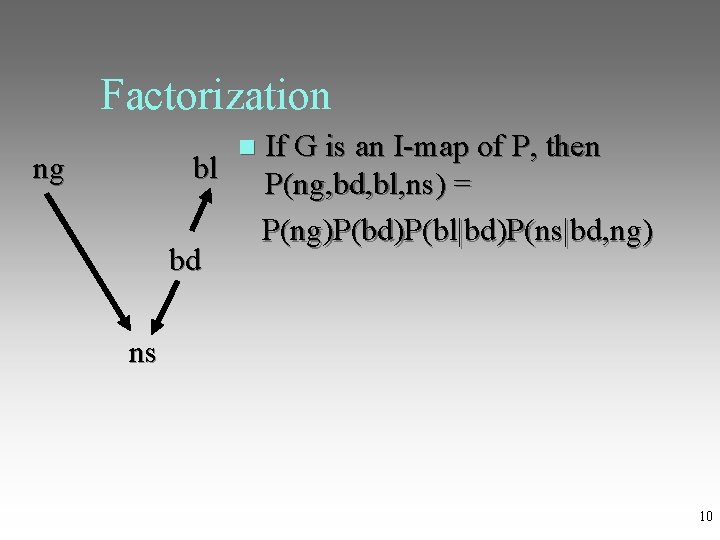

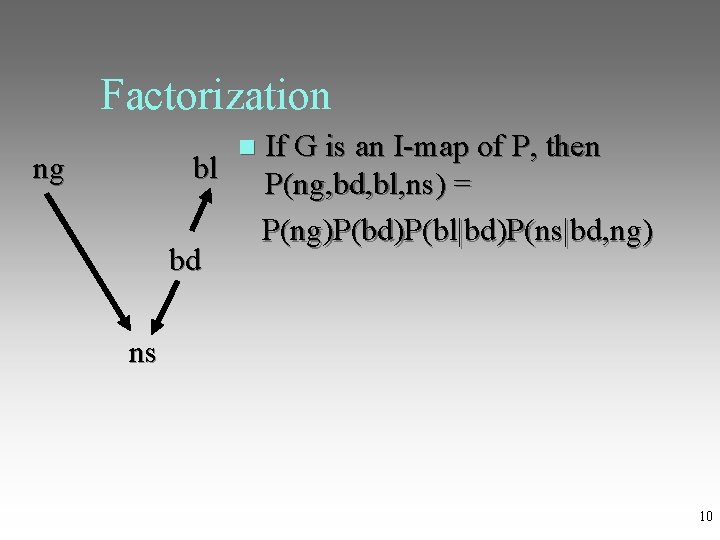

Factorization If G is an I-map of P, then ng bl P(ng, bd, bl, ns) = P(ng)P(bd)P(bl|bd)P(ns|bd, ng) bd ns 10

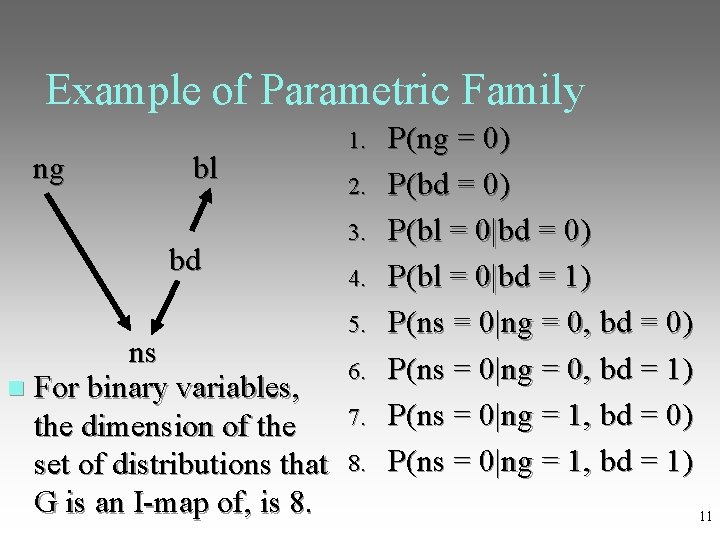

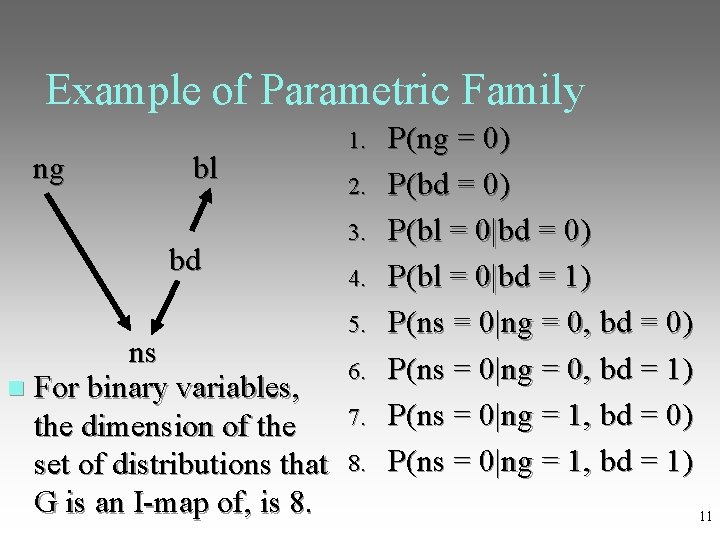

Example of Parametric Family 1. ng bl 2. 3. bd 4. 5. ns 6. For binary variables, the dimension of the 7. set of distributions that 8. G is an I-map of, is 8. P(ng = 0) P(bd = 0) P(bl = 0|bd = 1) P(ns = 0|ng = 0, bd = 0) P(ns = 0|ng = 0, bd = 1) P(ns = 0|ng = 1, bd = 0) P(ns = 0|ng = 1, bd = 1) 11

Outline Bayesian Networks Simplicity and Bayesian Networks Causal Interpretation of Bayesian Networks Greedy Equivalence Search 12

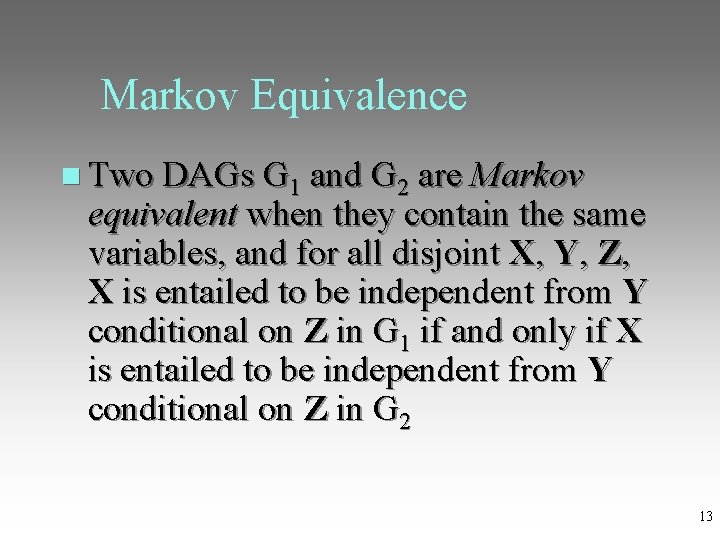

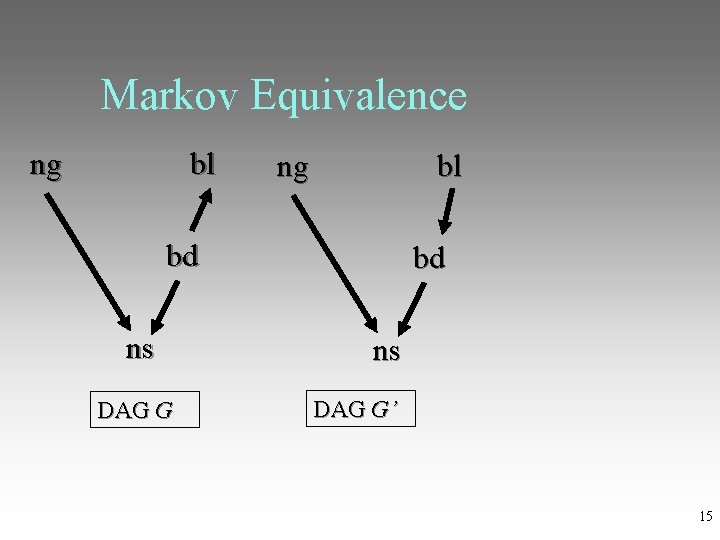

Markov Equivalence Two DAGs G 1 and G 2 are Markov equivalent when they contain the same variables, and for all disjoint X, Y, Z, X is entailed to be independent from Y conditional on Z in G 1 if and only if X is entailed to be independent from Y conditional on Z in G 2 13

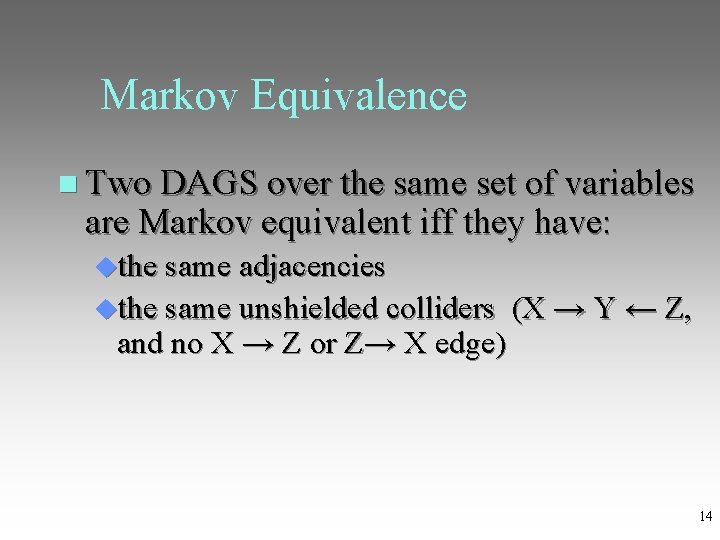

Markov Equivalence Two DAGS over the same set of variables are Markov equivalent iff they have: the same adjacencies the same unshielded colliders (X → Y ← Z, and no X → Z or Z→ X edge) 14

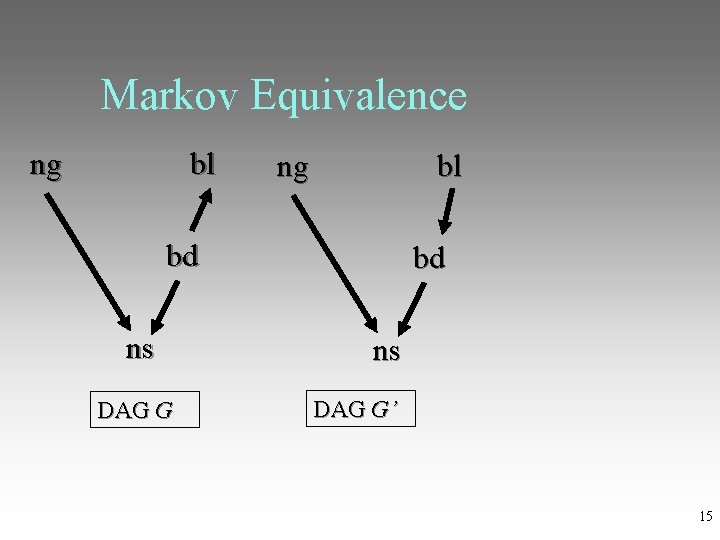

Markov Equivalence ng bl bd ns DAG G DAG G’ 15

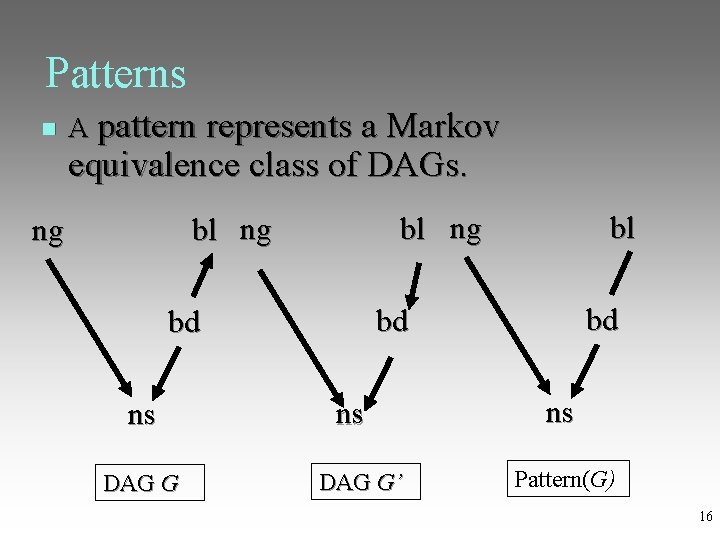

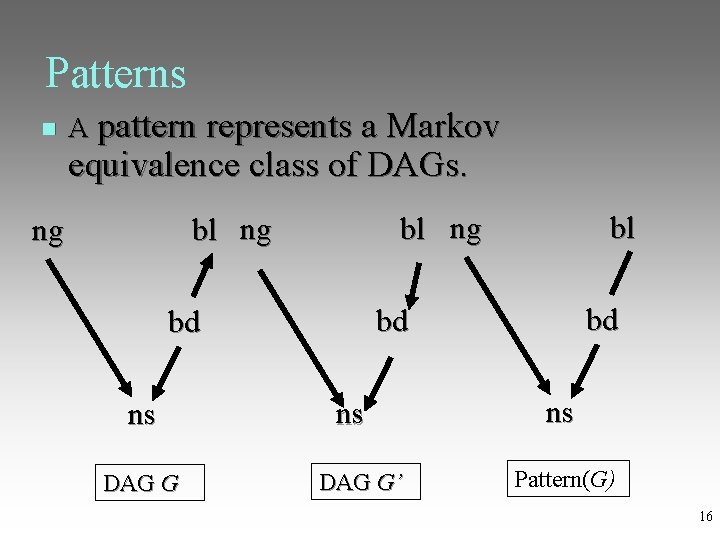

Patterns A pattern represents a Markov equivalence class of DAGs. ng bl bd ns ns DAG G DAG G’ Pattern(G) 16

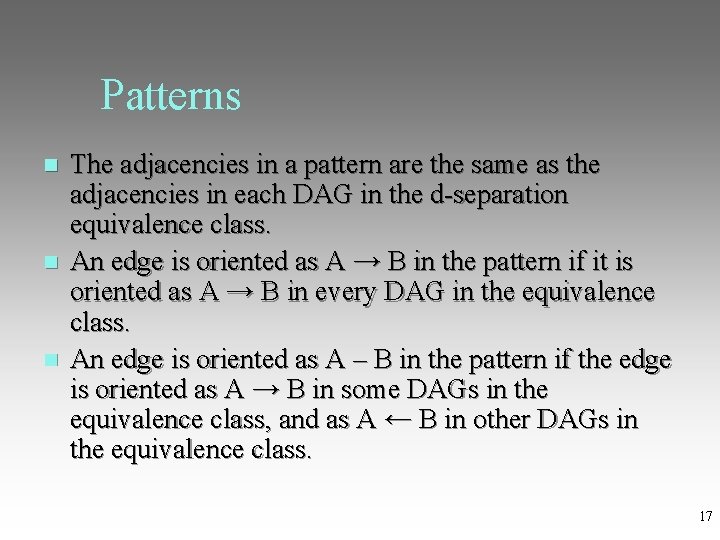

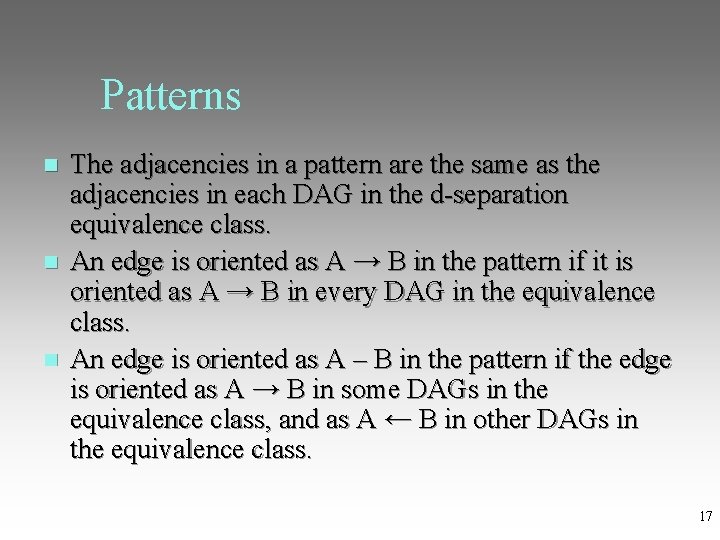

Patterns The adjacencies in a pattern are the same as the adjacencies in each DAG in the d-separation equivalence class. An edge is oriented as A → B in the pattern if it is oriented as A → B in every DAG in the equivalence class. An edge is oriented as A – B in the pattern if the edge is oriented as A → B in some DAGs in the equivalence class, and as A ← B in other DAGs in the equivalence class. 17

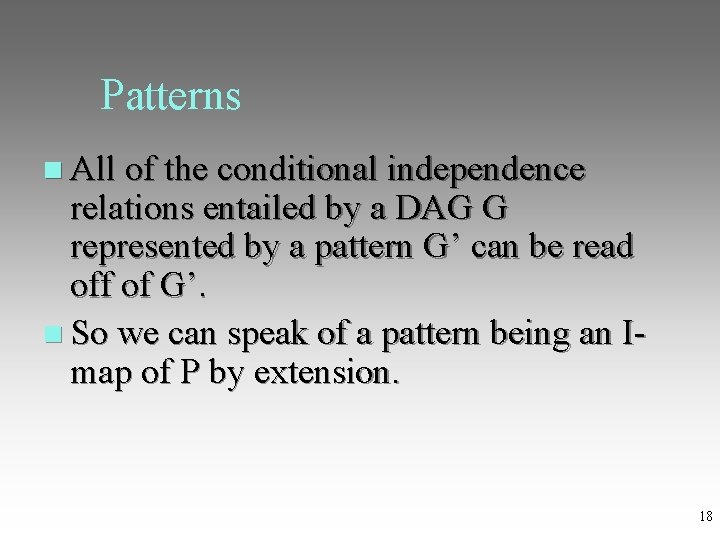

Patterns All of the conditional independence relations entailed by a DAG G represented by a pattern G’ can be read off of G’. So we can speak of a pattern being an Imap of P by extension. 18

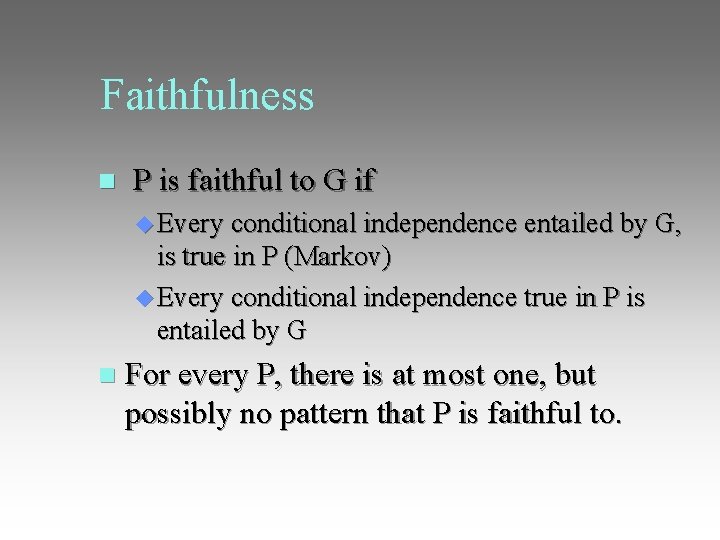

Faithfulness P is faithful to G if Every conditional independence entailed by G, is true in P (Markov) Every conditional independence true in P is entailed by G For every P, there is at most one, but possibly no pattern that P is faithful to.

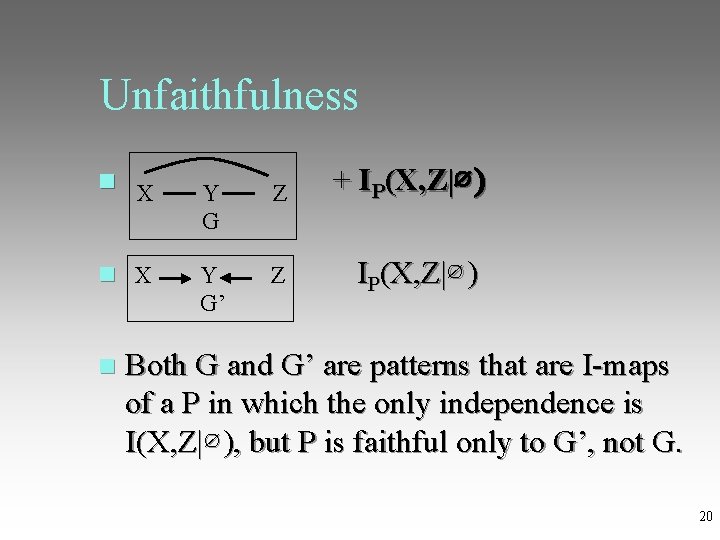

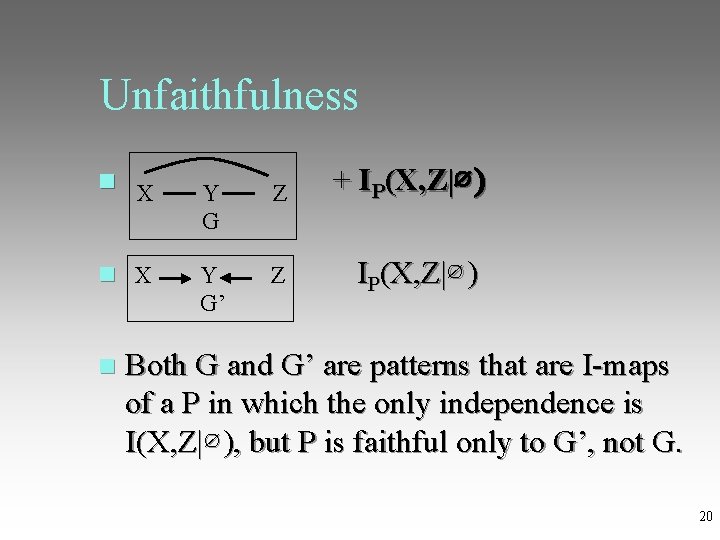

Unfaithfulness + IP(X, Z|∅ ) X Y Z G’ IP(X, Z|∅ ) Both G and G’ are patterns that are I-maps of a P in which the only independence is I(X, Z|∅ ), but P is faithful only to G’, not G. 20

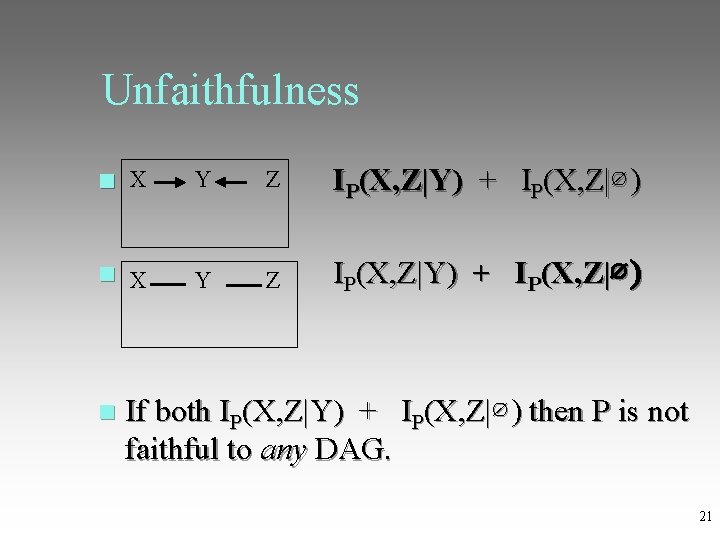

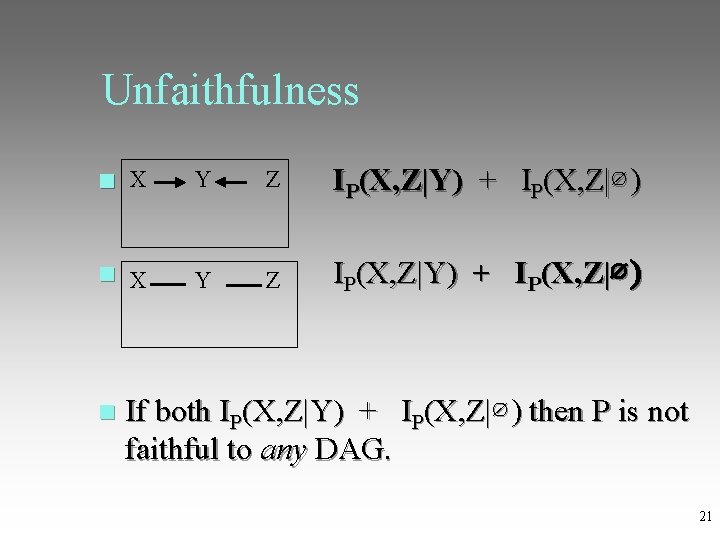

Unfaithfulness X Y Z IP(X, Z|Y) + IP(X, Z|∅ ) I X Y Z P(X, Z|Y) + IP(X, Z|∅ ) If both IP(X, Z|Y) + IP(X, Z|∅ ) then P is not faithful to any DAG. 21

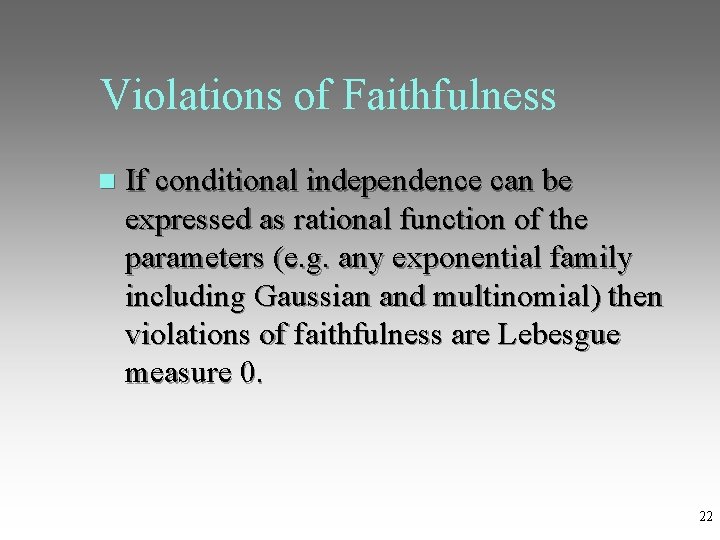

Violations of Faithfulness If conditional independence can be expressed as rational function of the parameters (e. g. any exponential family including Gaussian and multinomial) then violations of faithfulness are Lebesgue measure 0. 22

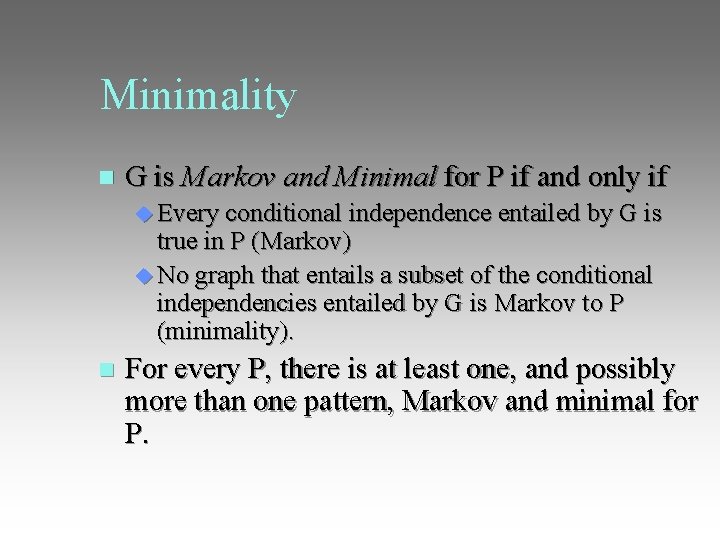

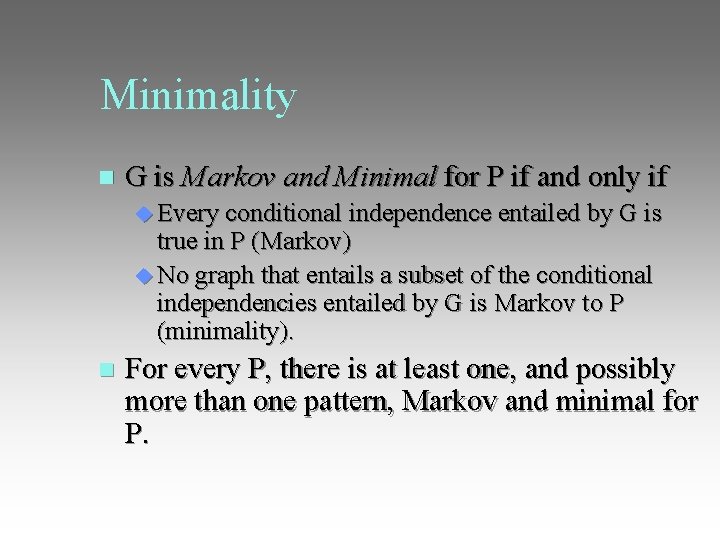

Minimality G is Markov and Minimal for P if and only if Every conditional independence entailed by G is true in P (Markov) No graph that entails a subset of the conditional independencies entailed by G is Markov to P (minimality). For every P, there is at least one, and possibly more than one pattern, Markov and minimal for P.

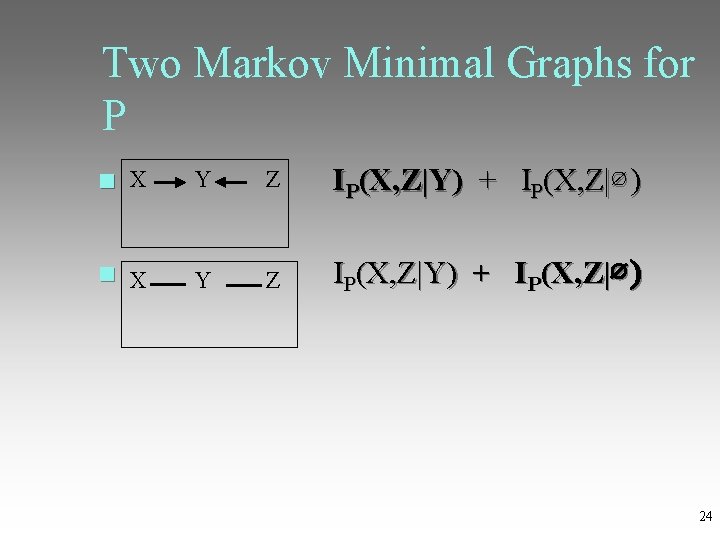

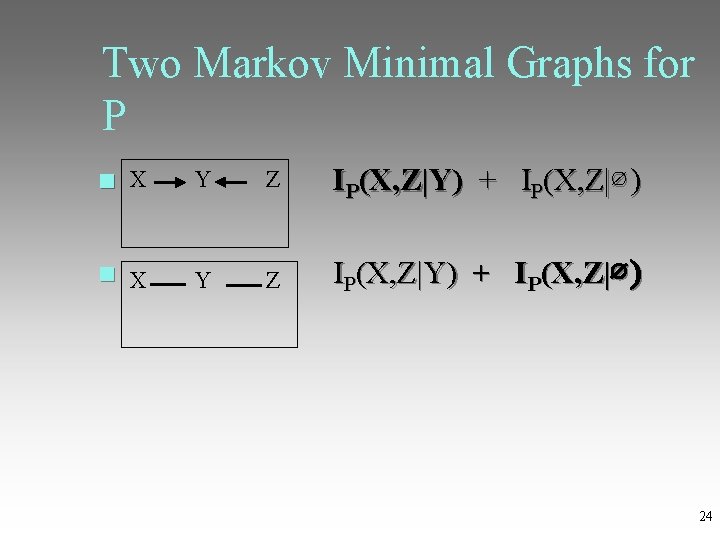

Two Markov Minimal Graphs for P X Y Z IP(X, Z|Y) + IP(X, Z|∅ ) I X Y Z P(X, Z|Y) + IP(X, Z|∅ ) 24

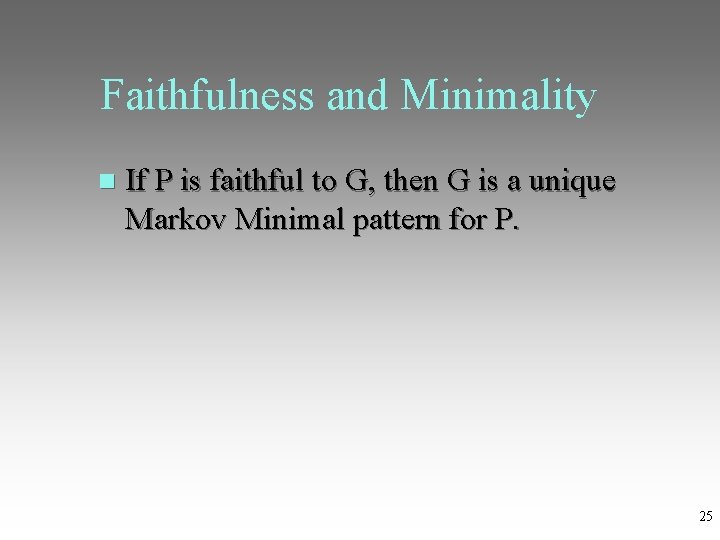

Faithfulness and Minimality If P is faithful to G, then G is a unique Markov Minimal pattern for P. 25

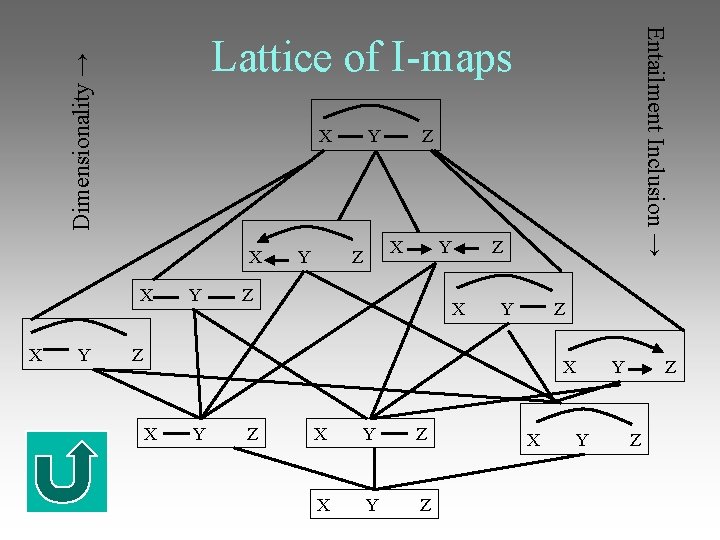

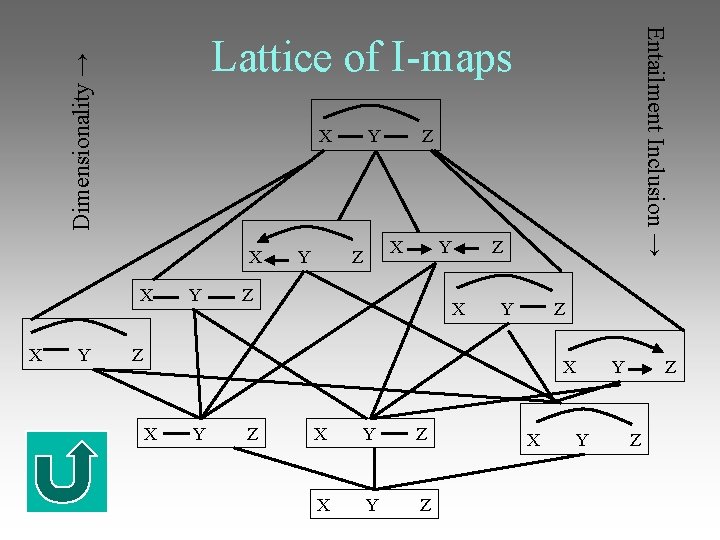

Entailment Inclusion → Dimensionality → Lattice of I-maps X Y Z X Y Z X Y Z

Outline Bayesian Networks Simplicity and Bayesian Networks Causal Interpretation of Bayesian Networks Greedy Equivalence Causal Search 27

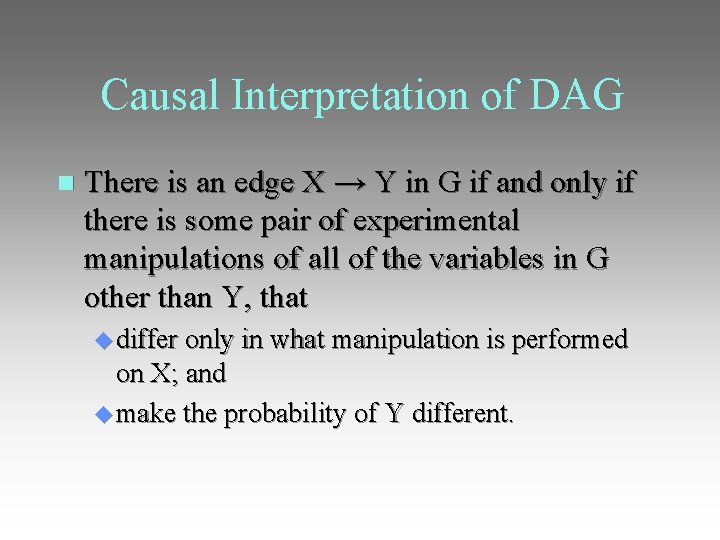

Causal Interpretation of DAG There is an edge X → Y in G if and only if there is some pair of experimental manipulations of all of the variables in G other than Y, that differ only in what manipulation is performed on X; and make the probability of Y different.

Causal Sufficiency A set S of variables is causally sufficient if there are no variables not in S that are direct causes of more than one variable in S. 29

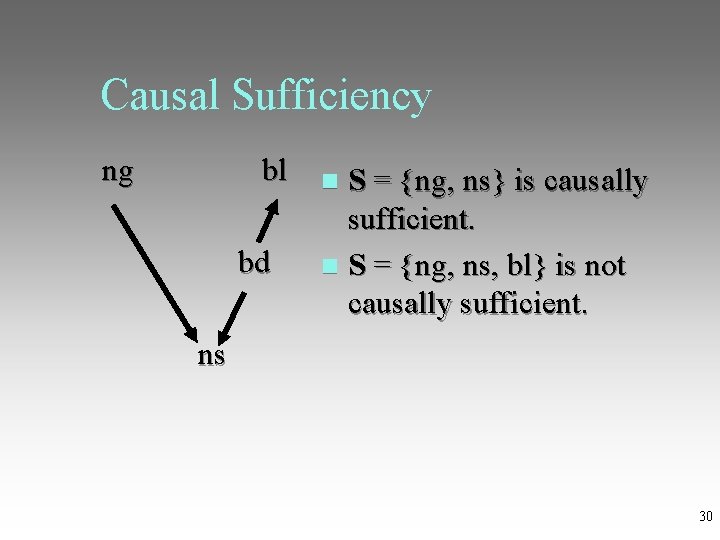

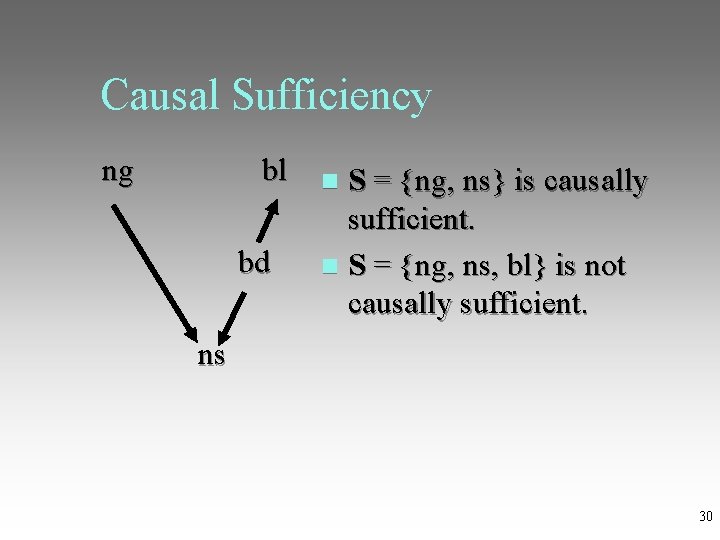

Causal Sufficiency ng bl S = {ng, ns} is causally sufficient. bd S = {ng, ns, bl} is not causally sufficient. ns 30

Causal Markov Assumption In a population Pop with causally sufficient graph G and distribution P, each variable is independent of its non-descendants (noneffects) conditional on its parents (immediate causes) in P. Equivalently: G is an I-map of P.

Causal Faithfulness Assumption In a population Pop with causally sufficient graph G and distribution P, I(X, Y|Z) in P only if X is entailed to be independent of Y conditional on Z by G.

Causal Faithfulness Assumption As currently used, it is a substantive simplicity assumption, not a methodological simplicity assumption. It says to prefer the simplest explanation: if a more complicated explanation is true, it leads astray.

Causal Faithfulness Assumption It serves two roles in practice: Aiding model choice (in which case weaker versions of the assumption will do) Simplifying search

Causal Minimality Assumption In a population Pop with causally sufficient graph G and distribution P, G is a minimal Imap of P. 35

Causal Minimality Assumption This is a strictly weaker simplicity assumption than Causal Faithfulness. Given the manipulation interpretation of the causal graph, and an everywhere positive distribution, the Causal Minimality Assumption is entailed by the Causal Markov Assumption. 36

Outline Bayesian Networks Simplicity and Bayesian Networks Causal Interpretation of Bayesian Networks Greedy Equivalence Search 37

Greedy Equivalence Search Inputs: Sample from a probability distribution over a causally sufficient set of variables from a population with causal graph G. Output: A pattern that represents G. 38

Assumptions Causally sufficient set of varaibles No feedback The true causal structure can be represented by a DAG. Causal Markov Assumption Causal Faithfulness Assumption 39

Consistent scores If model M 1 contains the true distribution, while model M 2 doesn’t, then in the large sample limit M 1 gets the higher score. If both M 1 and M 2 contain the true distribution, and M 1 has fewer parameters than M 2 does, then in the large sample limit M 1 gets the higher score. 40

Consistent scores So, assuming the Causal Markov and Faithfulness conditions, a consistent score assigns the true model (and its Markov equivalent models) the highest score in the limit. Examples: Bayesian Information Criterion, posterior of Bde or Bge prior 41

Score Equivalence Under BIC, Bde, and Bge, Markov equivalent DAGs are also score equivalent, i. e. , always receive the same score. (Could also use posterior probabilities under a wide variety of priors). This allows GES to search over the space of patterns, instead of the space of DAGs. 42

Two Phases of GES Forward Greedy Search (FGS): Starting with any pattern Q, evaluate all patterns that are I-maps of Q with one more edge, and move to the one with the best increase of score. Iterate until local maximum. Backward Greedy Search (BGS): Starting with a pattern Q that contains the true distribution, evaluate all patterns with one fewer edge of which Q is an I-map, and move to the one with the best increase of score. Iterate until local maximum. 43

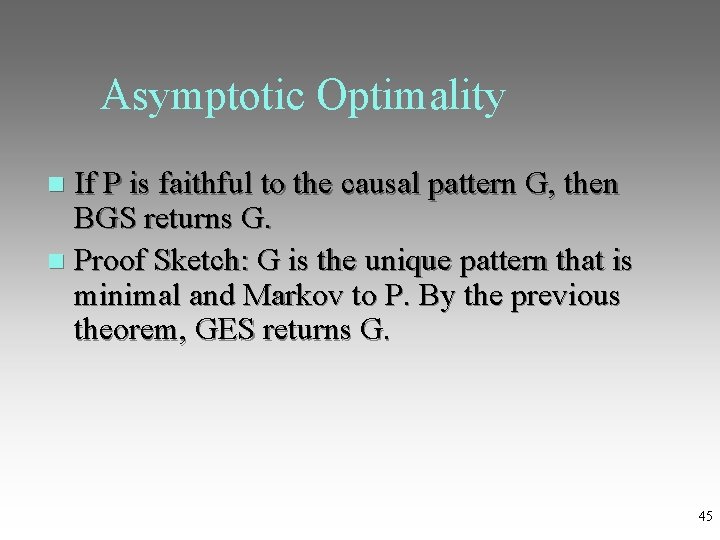

Asymptotic Optimality In the large sample limit, GES always returns a pattern that is minimal and Markov to P. Proof. Because the score is consistent, the forward phase continues until it reaches a pattern G such that P is Markov to G. The backward phase preserves Markov, and continues until there is no pattern that is both Markov to P and entails more independencies. 44

Asymptotic Optimality If P is faithful to the causal pattern G, then BGS returns G. Proof Sketch: G is the unique pattern that is minimal and Markov to P. By the previous theorem, GES returns G. 45

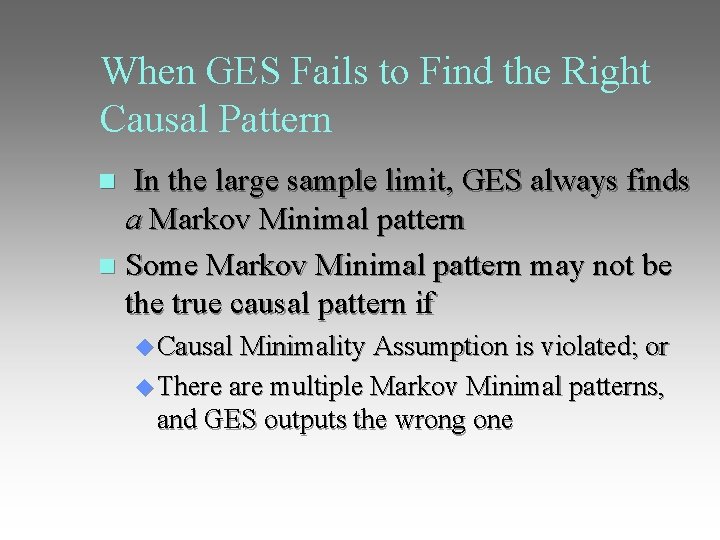

When GES Fails to Find the Right Causal Pattern In the large sample limit, GES always finds a Markov Minimal pattern Some Markov Minimal pattern may not be the true causal pattern if Causal Minimality Assumption is violated; or There are multiple Markov Minimal patterns, and GES outputs the wrong one

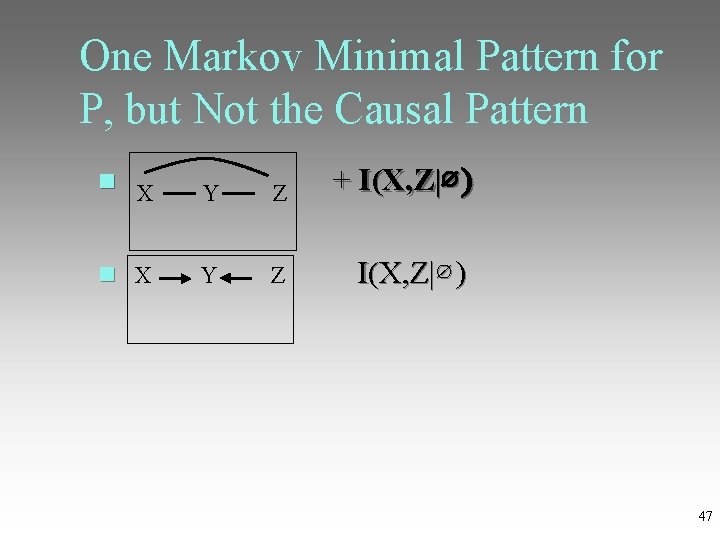

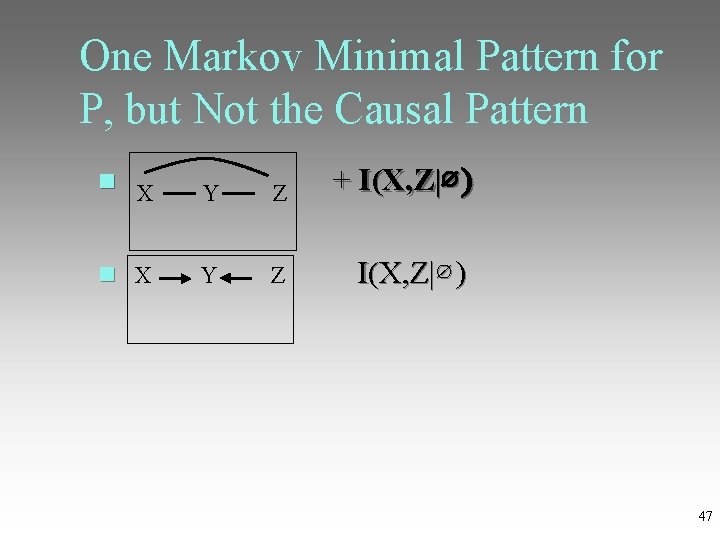

One Markov Minimal Pattern for P, but Not the Causal Pattern + I(X, Z|∅ ) X Y Z I(X, Z|∅ ) 47

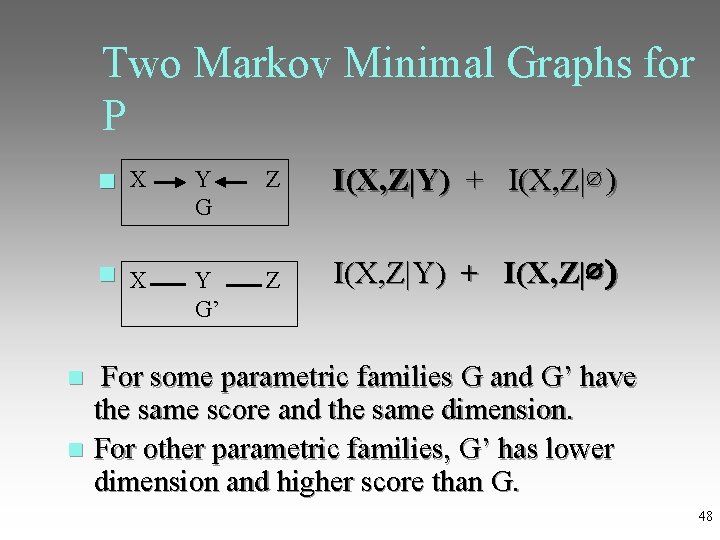

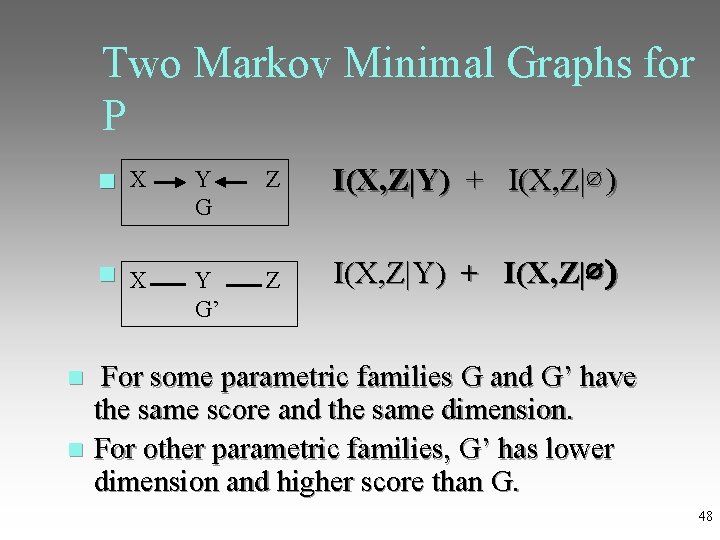

Two Markov Minimal Graphs for P X Y Z I(X, Z|Y) + I(X, Z|∅ ) G I(X, Z|Y) X Y Z G’ + I(X, Z|∅ ) For some parametric families G and G’ have the same score and the same dimension. For other parametric families, G’ has lower dimension and higher score than G. 48

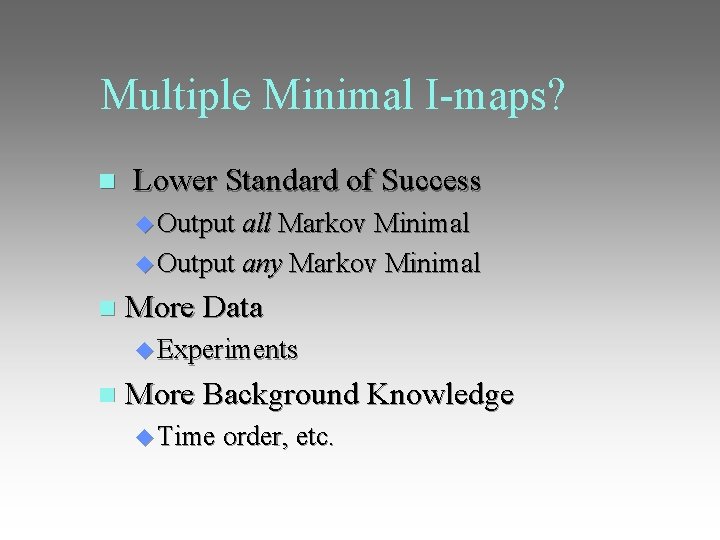

Multiple Minimal I-maps? Lower Standard of Success Output all Markov Minimal Output any Markov Minimal More Data Experiments More Background Knowledge Time order, etc.

References Chickering, M. (2002) Optimal Structure Identification With Greedy Search, Journal of Machine Learning Research 3, pp. 507554. Spirtes, P. , Glymour, C. , and Scheines, R. , (2000) Causation, Prediction, and Search, 2 nd edition. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. 50