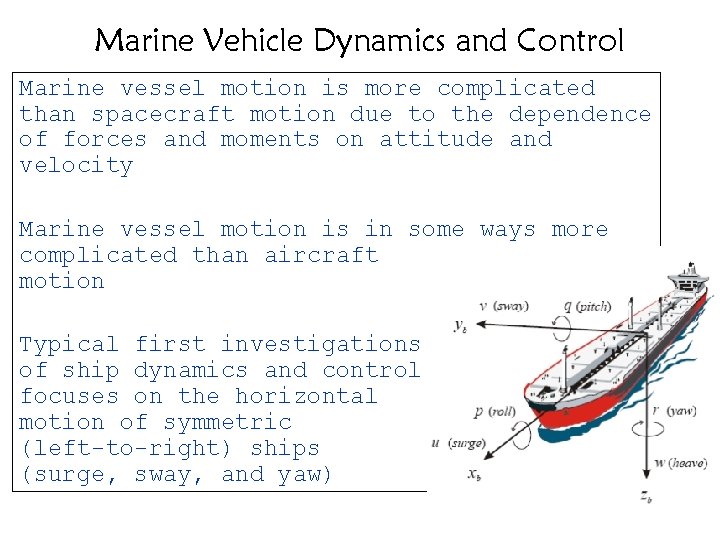

Marine Vehicle Dynamics and Control Marine vessel motion

- Slides: 15

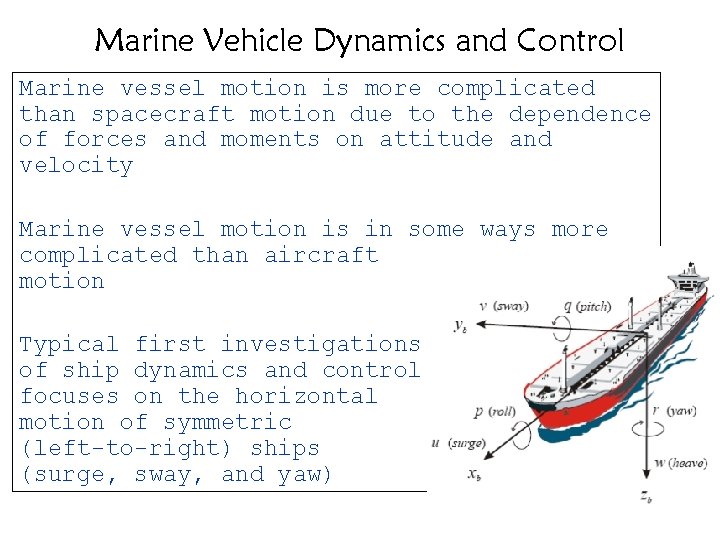

Marine Vehicle Dynamics and Control Marine vessel motion is more complicated than spacecraft motion due to the dependence of forces and moments on attitude and velocity Marine vessel motion is in some ways more complicated than aircraft motion Typical first investigations of ship dynamics and control focuses on the horizontal motion of symmetric (left-to-right) ships (surge, sway, and yaw)

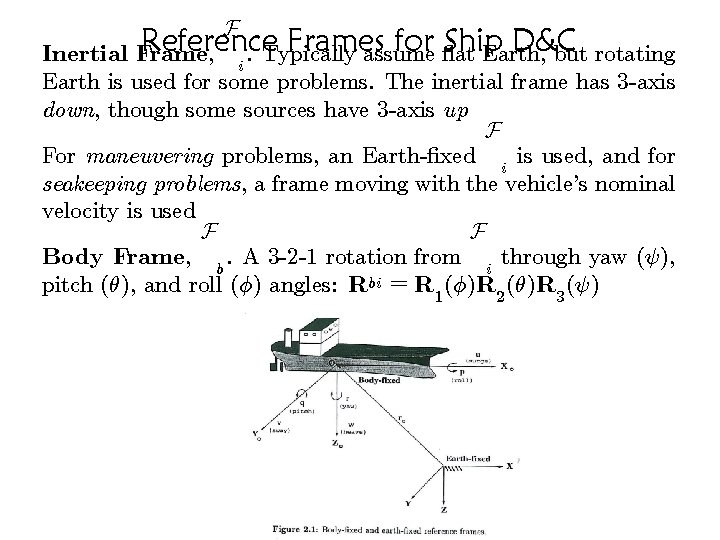

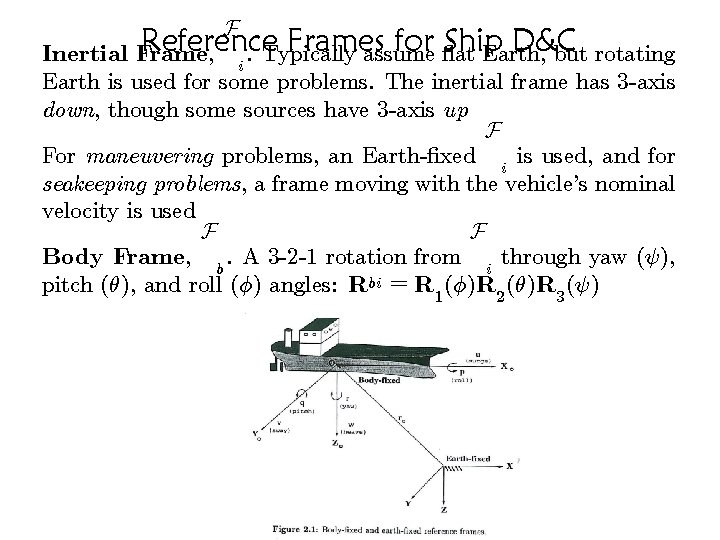

F Reference Frames for °at Ship D&C Inertial Frame, . Typically Earth, assume but rotating i Earth is used for some problems. The inertial frame has 3 -axis down, though some sources have 3 -axis up F For maneuvering problems, an Earth-¯xed i is used, and for seakeeping problems, a frame moving with the vehicle's nominal velocity is used F F Body Frame, b. A 3 -2 -1 rotation from i through yaw (Ã), pitch (µ), and roll (Á) angles: Rbi = R 1 (Á)R 2 (µ)R 3 (Ã)

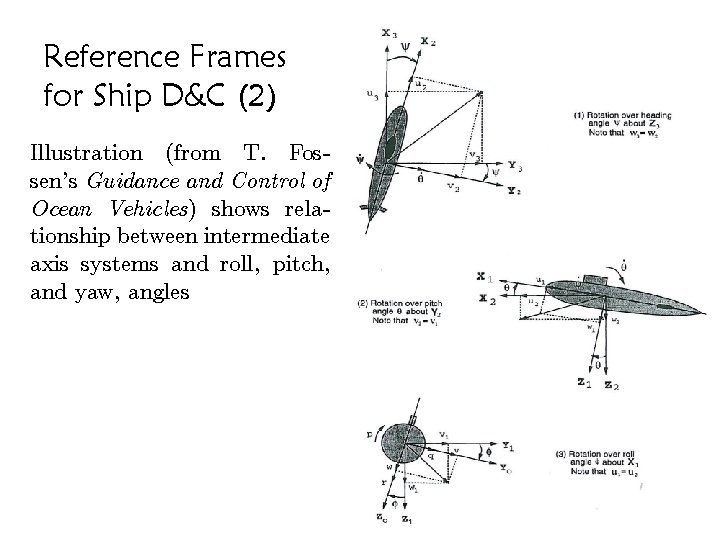

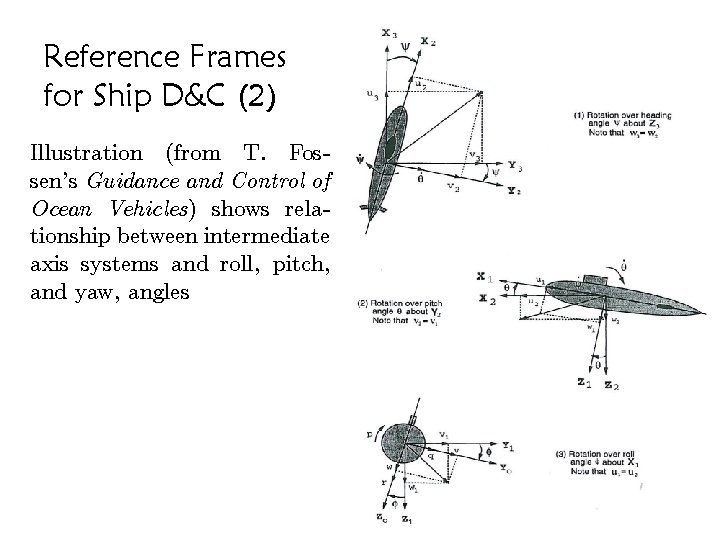

Reference Frames for Ship D&C (2) Illustration (from T. Fossen's Guidance and Control of Ocean Vehicles) shows relationship between intermediate axis systems and roll, pitch, and yaw, angles

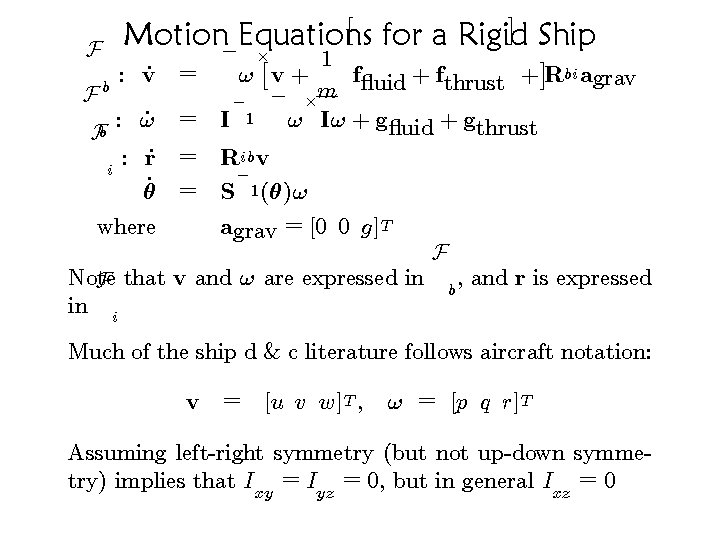

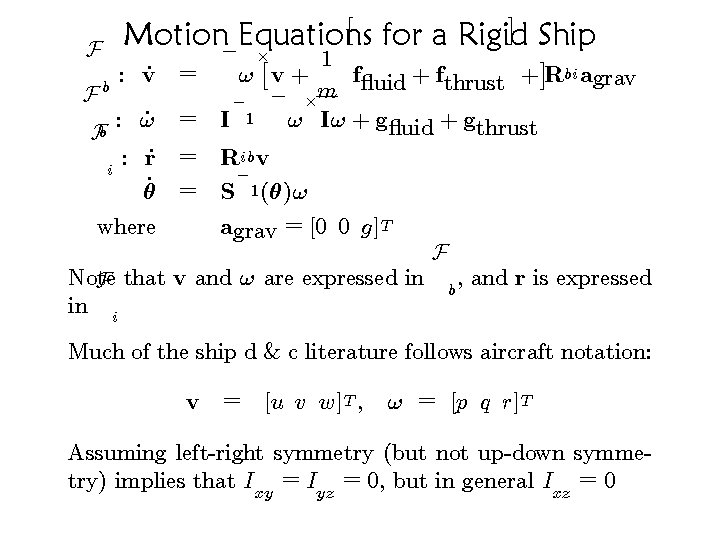

¤ Motion¡Equations for a Rigid Ship F F £ b Fb i : v_ = : !_ = : r_ µ_ = = where £ £ ¤ 1 f°uid + fthrust + Rbi agrav ! v+ m ¡ ¡ £ I 1 ! I! + g°uid + gthrust Rib v ¡ S 1 (µ)! agrav = [0 0 g]T Note F that v and ! are expressed in in i F b , and r is expressed Much of the ship d & c literature follows aircraft notation: v = [u v w]T ; ! = [p q r]T Assuming left-right symmetry (but not up-down symmetry) implies that Ixy = Iyz = 0, but in general Ixz = 0

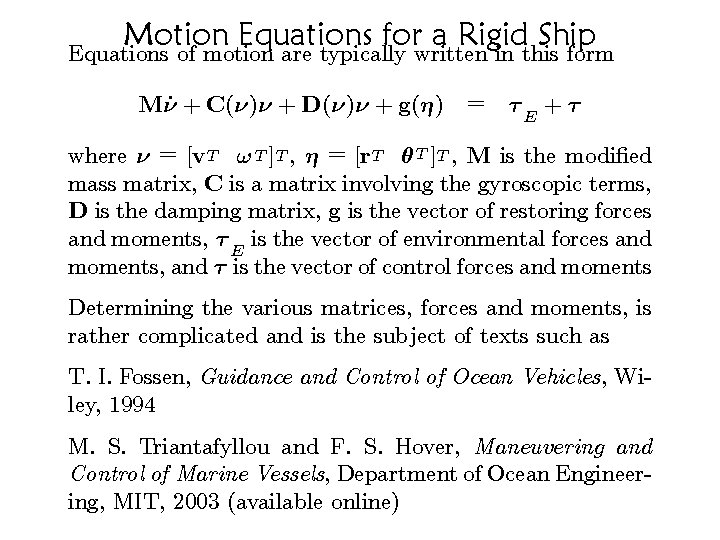

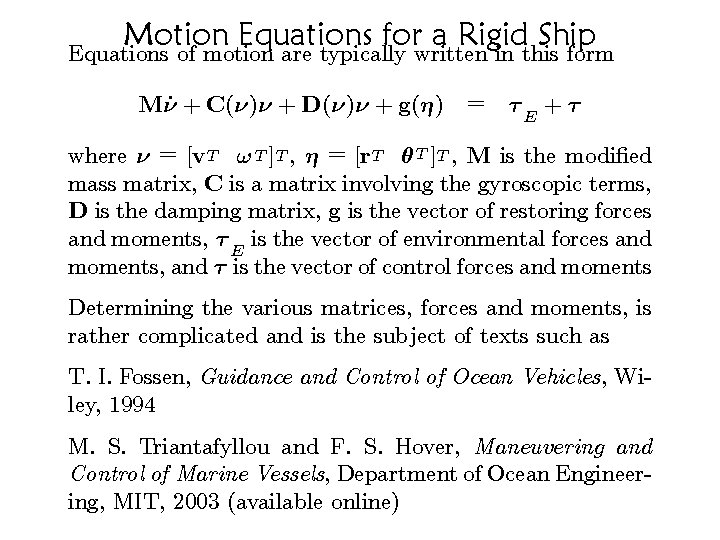

Motion Equations for a Rigid Ship Equations of motion are typically written in this form Mº_ + C(º)º + D(º)º + g(´) = ¿E + ¿ where º = [v. T ! T ]T , ´ = [r. T µ T ]T , M is the modi¯ed mass matrix, C is a matrix involving the gyroscopic terms, D is the damping matrix, g is the vector of restoring forces and moments, ¿ E is the vector of environmental forces and moments, and ¿ is the vector of control forces and moments Determining the various matrices, forces and moments, is rather complicated and is the subject of texts such as T. I. Fossen, Guidance and Control of Ocean Vehicles, Wiley, 1994 M. S. Triantafyllou and F. S. Hover, Maneuvering and Control of Marine Vessels, Department of Ocean Engineering, MIT, 2003 (available online)

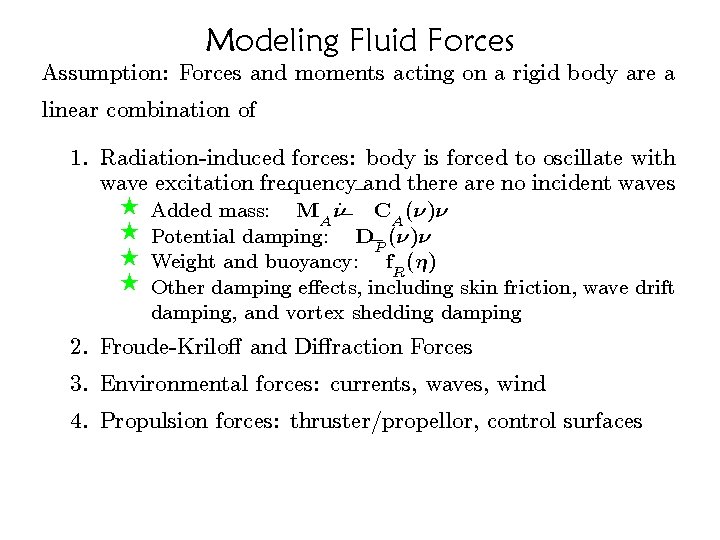

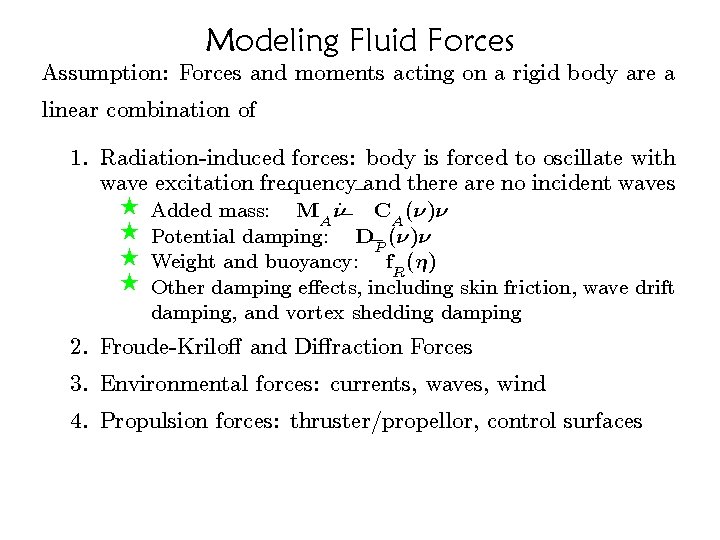

Modeling Fluid Forces Assumption: Forces and moments acting on a rigid body are a linear combination of 1. Radiation-induced forces: body is forced to oscillate with wave excitation frequency ¡ ¡and there are no incident waves F F Added mass: MA º_¡ CA (º)º Potential damping: D¡ P Weight and buoyancy: f. R (´) Other damping e®ects, including skin friction, wave drift damping, and vortex shedding damping 2. Froude-Krilo® and Di®raction Forces 3. Environmental forces: currents, waves, wind 4. Propulsion forces: thruster/propellor, control surfaces

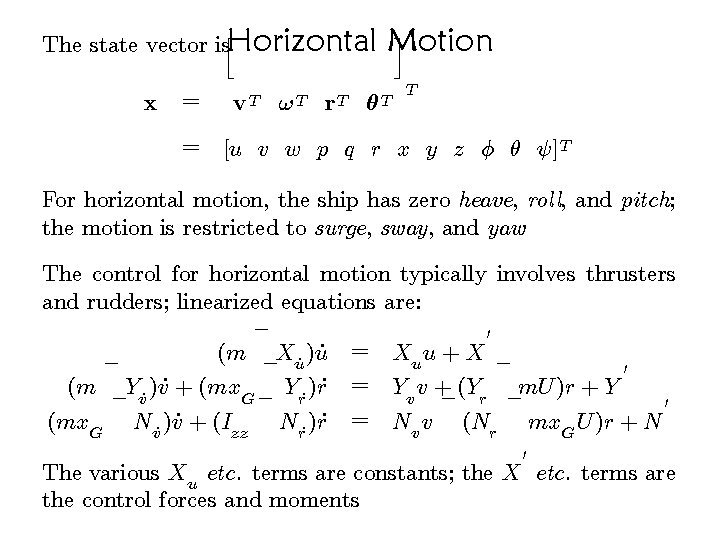

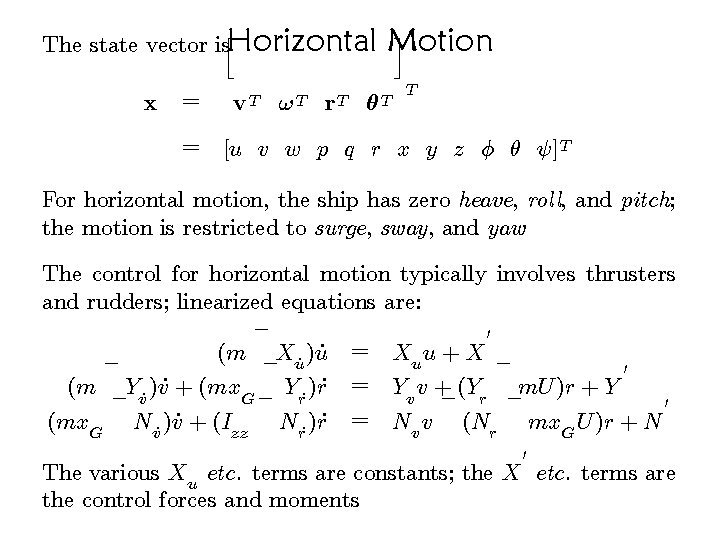

h i Horizontal Motion The state vector is x = = v. T !T r. T µT T [u v w p q r x y z Á µ Ã]T For horizontal motion, the ship has zero heave, roll, and pitch; the motion is restricted to surge, sway, and yaw The control for horizontal motion typically involves thrusters and rudders; linearized equations are: ¡ 0 (m ¡Xu_ )u_ = Xu u + X ¡ ¡ 0 (m ¡Yv_ )v_ + (mx. G ¡ Yr_ )r_ = Yv v + ¡(Yr ¡m. U )r + Y 0 (mx N )v_ + (I N )r_ = N v (N mx U )r + N G v_ zz r_ v G r 0 The various Xu etc. terms are constants; the X etc. terms are the control forces and moments

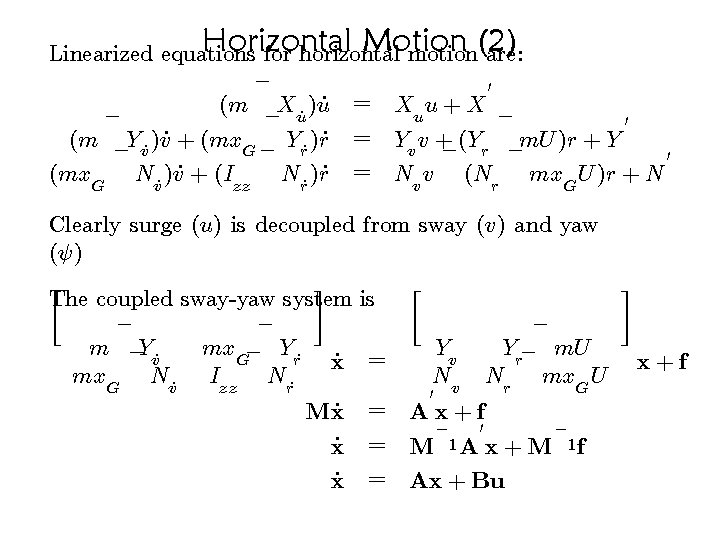

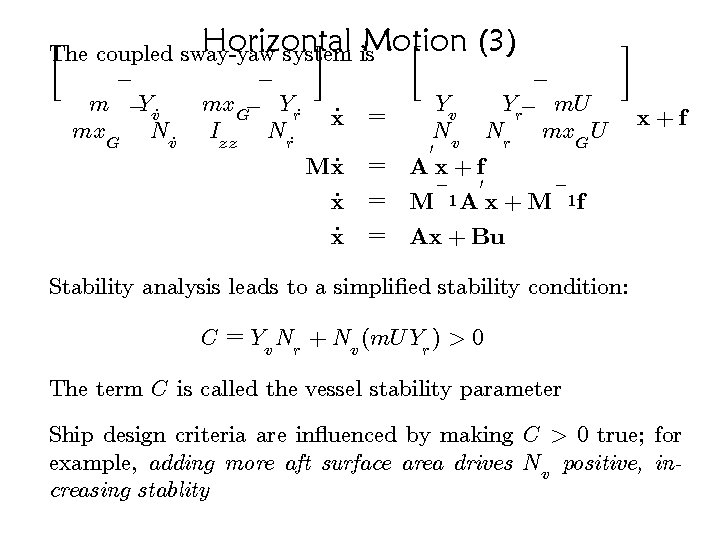

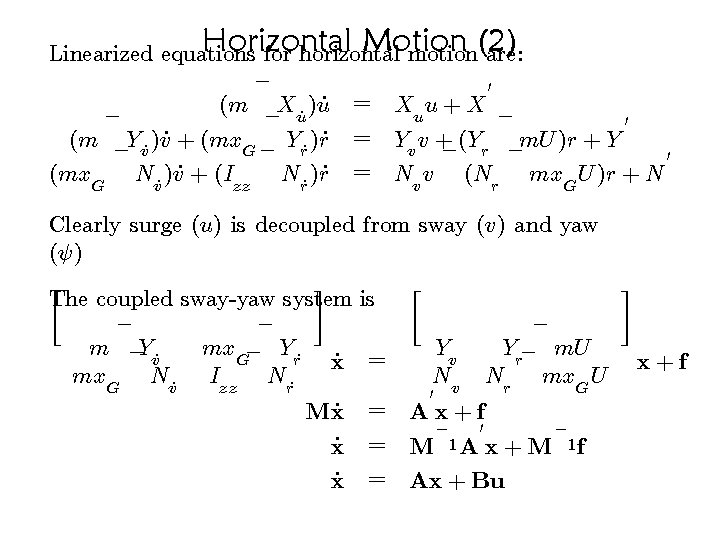

Horizontal Motion Linearized equations motion(2) are: for horizontal ¡ 0 (m ¡Xu_ )u_ = Xu u + X ¡ ¡ 0 (m ¡Yv_ )v_ + (mx. G ¡ Yr_ )r_ = Yv v + ¡(Yr ¡m. U )r + Y 0 mx U )r + N N )v_ + (I N )r_ = N v (N (mx G v_ zz r_ v r G Clearly surge (u) is decoupled from sway (v) and yaw (Ã) · ¸ The coupled sway-yaw system is ¡ ¡ ¡ Yv Yr¡ m. U m ¡Yv_ mx. G¡ Yr_ = x_ x+f Nv Nr mx. G U mx. G Nv_ Izz Nr_ 0 Mx_ = A x + f x_ x_ ¡ 0 = M = Ax + Bu 1 A x+M ¡ 1 f

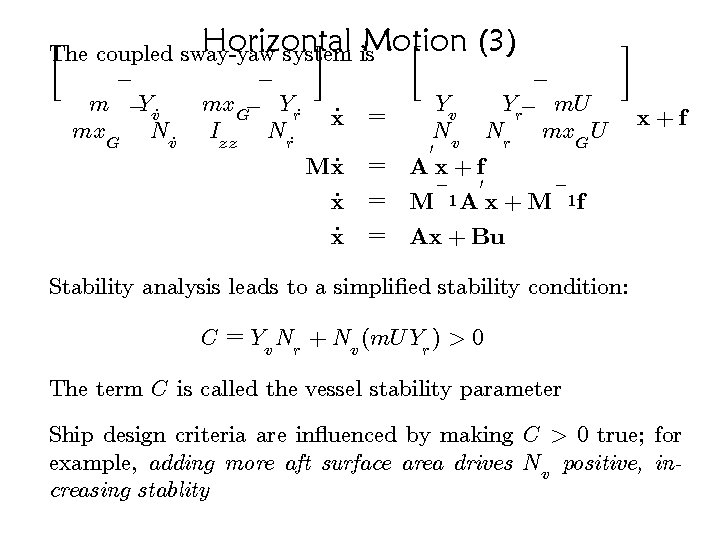

· ¸ Horizontal Motion (3) The coupled sway-yaw system is ¡ ¡ ¡ m ¡Yv_ mx. G¡ Yr_ Yv Yr¡ m. U = x_ x+f mx. G Nv_ Izz Nr_ Nv Nr mx. G U 0 Mx_ = A x + f x_ x_ ¡ 0 = M = Ax + Bu 1 A x+M ¡ 1 f Stability analysis leads to a simpli¯ed stability condition: C = Yv Nr + Nv (m. U Yr ) > 0 The term C is called the vessel stability parameter Ship design criteria are in°uenced by making C > 0 true; for example, adding more aft surface area drives Nv positive, increasing stablity

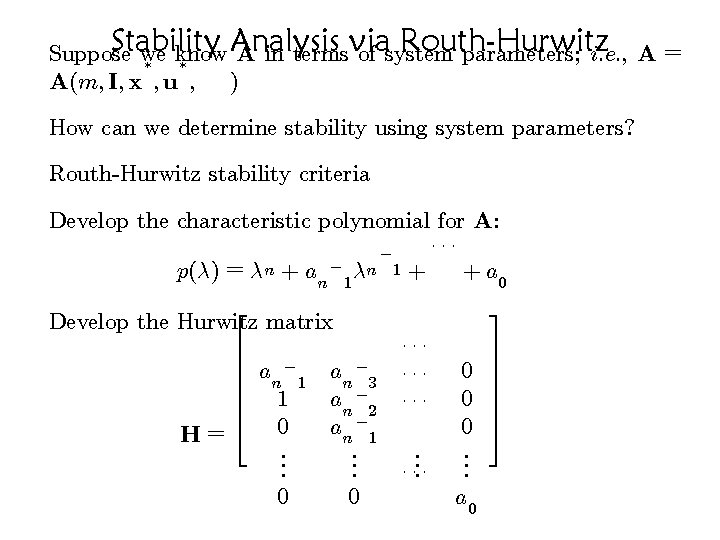

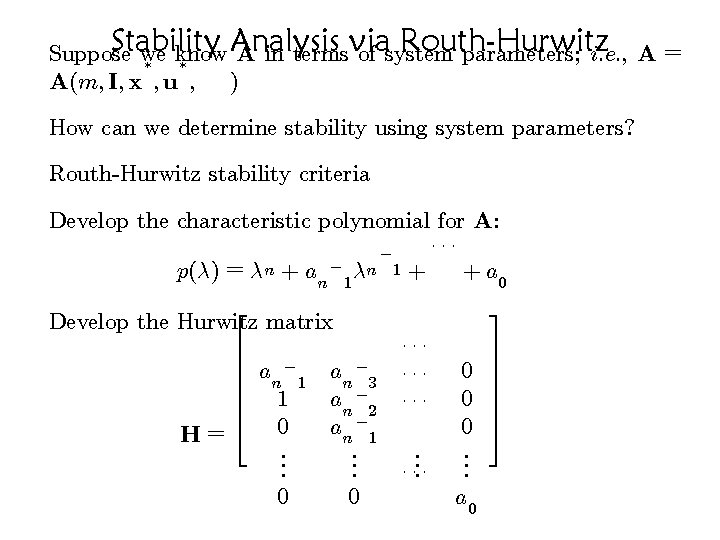

Stability Analysis via Routh-Hurwitz in terms Suppose A we of system know parameters; i. e. , A = ¢ ¢ ¢ ¤ ¤ ) A(m; I; x ; u ; How can we determine stability using system parameters? Routh-Hurwitz stability criteria Develop the characteristic polynomial for A: ¢¢¢ ¡ p(¸) = ¸n + an¡ 1 ¸n 1 + + a 0 2 Develop the Hurwitz matrix 6 6 a ¡ 6 n 1 n 3 6 1 a n¡ 2 6 ¡ 4 0 a = H n 1. . . 0 0 ¢¢¢ ¢¢¢. . ¢ ¢. ¢ 3 7 0 7 7 0 5. . . a 0

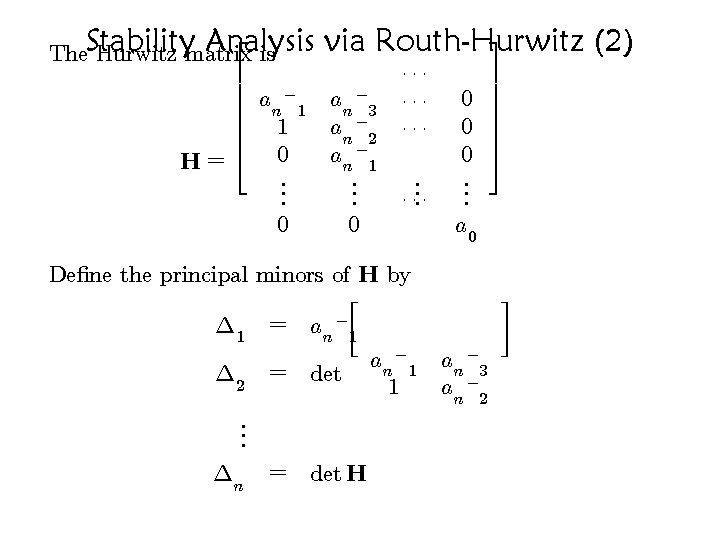

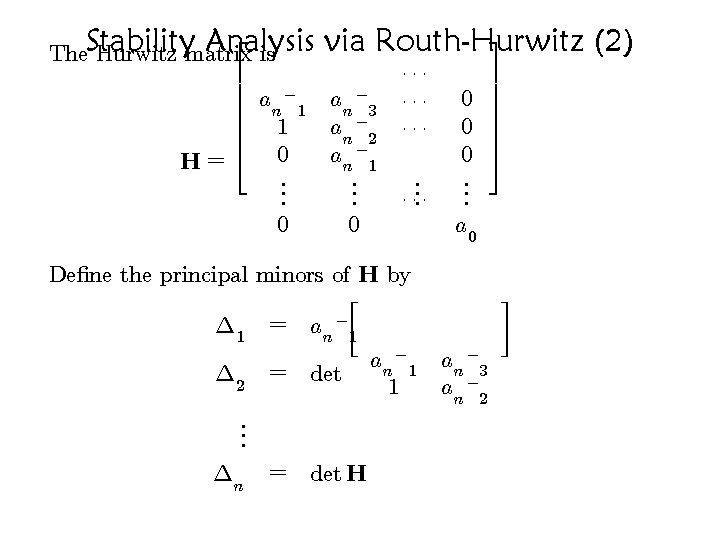

2 3 Stability Analysis via Routh-Hurwitz (2) The Hurwitz matrix is 6 6 a ¡ 6 n 1 6 4 0 = H. . . 0 ¡ an 3 a n¡ 2 a n¡ 1. . . 0 ¢¢¢ ¢¢¢. . ¢ ¢. ¢ De¯ne the principal minors of H by · ¢ 1 = an ¡ 1 ¡ a n 1 ¢ 2 = det 1. . . = det H ¢ n 7 0 7 7 0 5. . . a 0 a n¡ 3 a n¡ 2 ¸

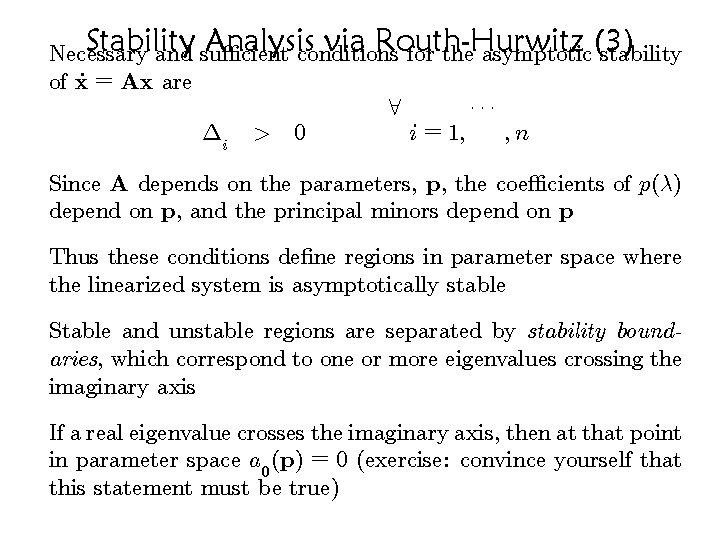

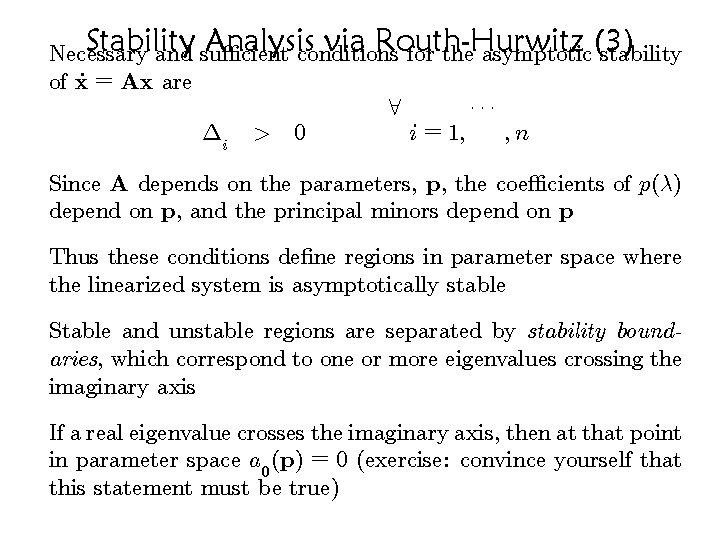

Stability Analysis via Routh-Hurwitz Necessary and su±cient conditions stability for the asymptotic (3) of x_ = Ax are ¢¢¢ 8 ¢i > 0 i = 1; ; n Since A depends on the parameters, p, the coe±cients of p(¸) depend on p, and the principal minors depend on p Thus these conditions de¯ne regions in parameter space where the linearized system is asymptotically stable Stable and unstable regions are separated by stability boundaries, which correspond to one or more eigenvalues crossing the imaginary axis If a real eigenvalue crosses the imaginary axis, then at that point in parameter space a 0 (p) = 0 (exercise: convince yourself that this statement must be true)

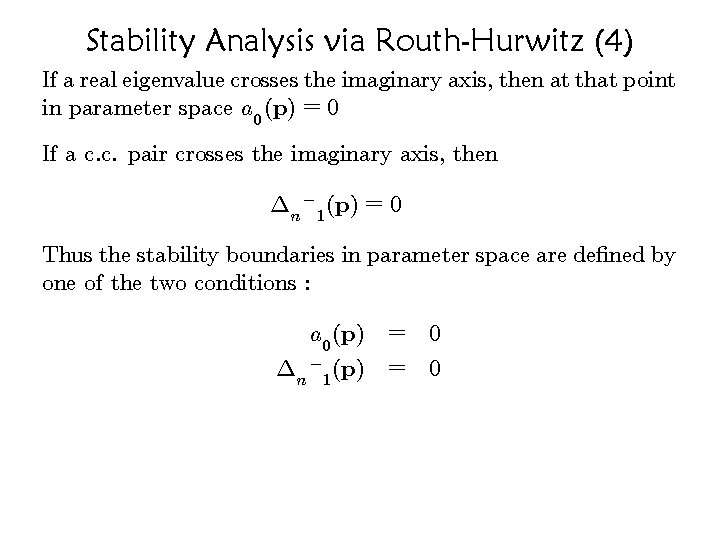

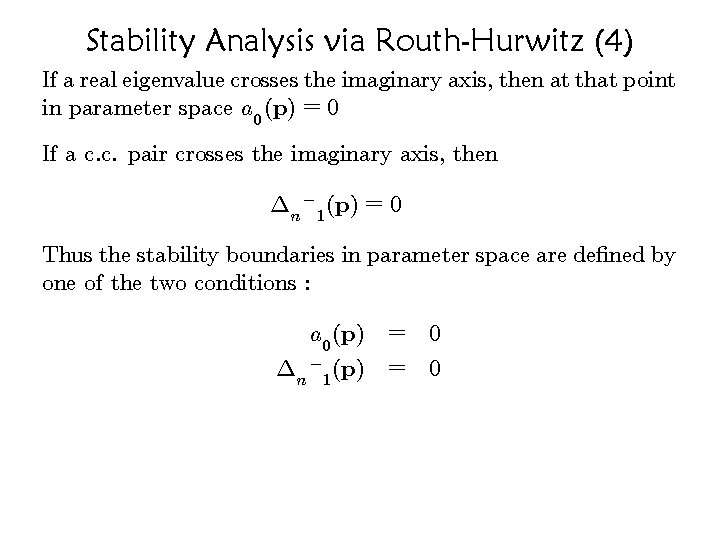

Stability Analysis via Routh-Hurwitz (4) If a real eigenvalue crosses the imaginary axis, then at that point in parameter space a 0 (p) = 0 If a c. c. pair crosses the imaginary axis, then ¢n¡ 1 (p) = 0 Thus the stability boundaries in parameter space are de¯ned by one of the two conditions : a 0 (p) = 0 ¢n¡ 1 (p) = 0

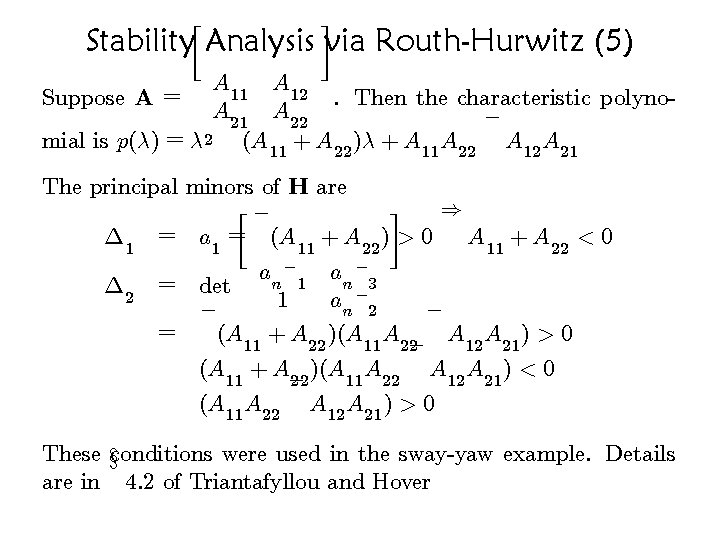

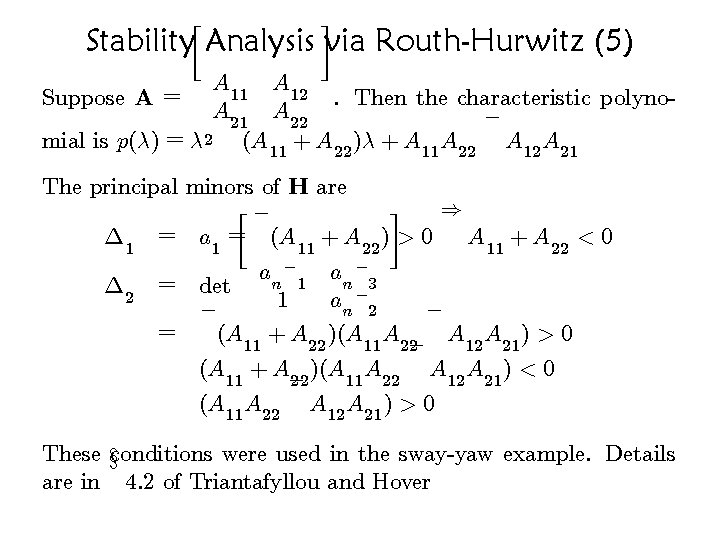

· ¸ Stability Analysis via Routh-Hurwitz (5) A 11 A 12. Then the characteristic polyno. A¡ 21 A 22 ¡ mial is p(¸) = ¸ 2 (A 11 + A 22 )¸ + A 11 A 22 A 12 A 21 Suppose A = The principal minors of H are ·¡ ¸ ) ¢ 1 = a 1 = (A 11 + A 22 ) > 0 A 11 + A 22 < 0 ¡ ¡ a a n 1 n 3 ¢ 2 = det ¡ a 1 n 2 ¡ ¡ = (A 11 + A 22 )(A 11 A 22 ¡ A 12 A 21 ) > 0 (A 11 + A¡ )(A 11 A 22 A 12 A 21 ) < 0 22 (A 11 A 22 A 12 A 21 ) > 0 These xconditions were used in the sway-yaw example. Details are in 4. 2 of Triantafyllou and Hover

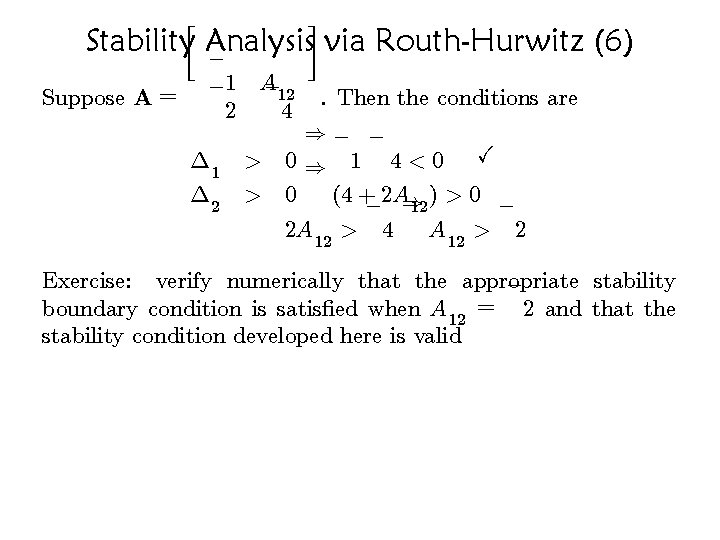

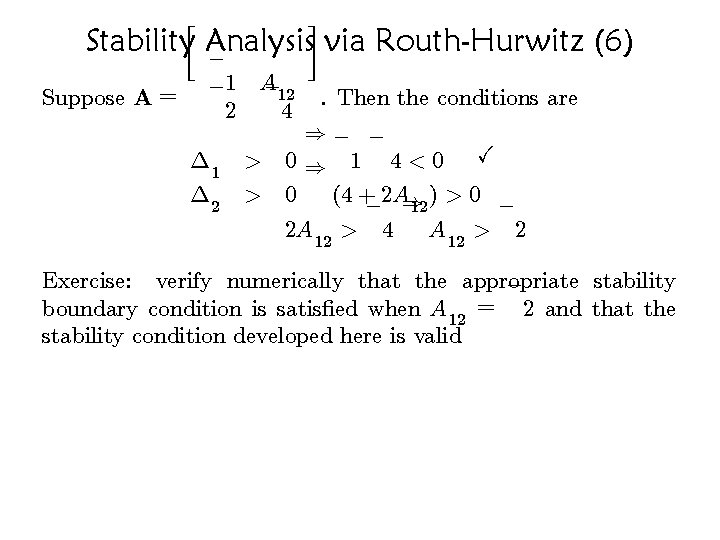

· ¸ Stability Analysis via Routh-Hurwitz (6) ¡ Suppose A = ¡ 1 2 A ¡ 12 4 ¢ 1 > ¢ 2 > . Then the conditions are )¡ ¡ 0) 1 4<0 X 0 (4 + )>0 ¡ ¡ 2 A) 12 2 A 12 > 4 A 12 > 2 Exercise: verify numerically that the appropriate stability ¡ boundary condition is satis¯ed when A 12 = 2 and that the stability condition developed here is valid