Maps Graphs on Surfaces We are mainly interested

- Slides: 38

Maps

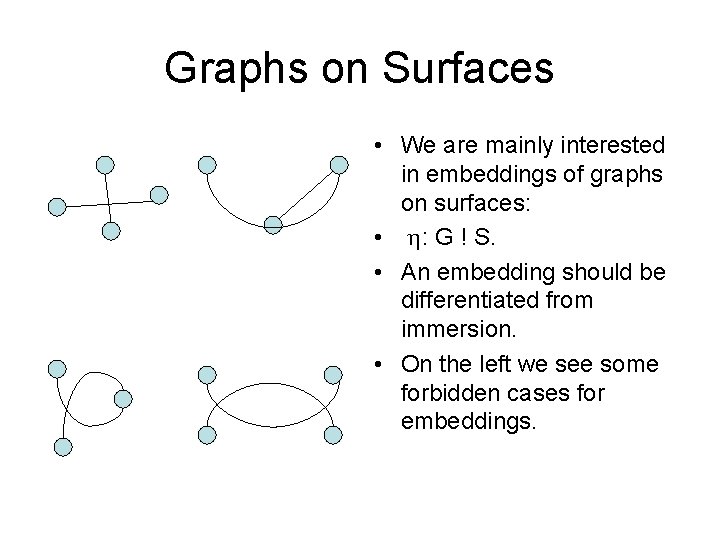

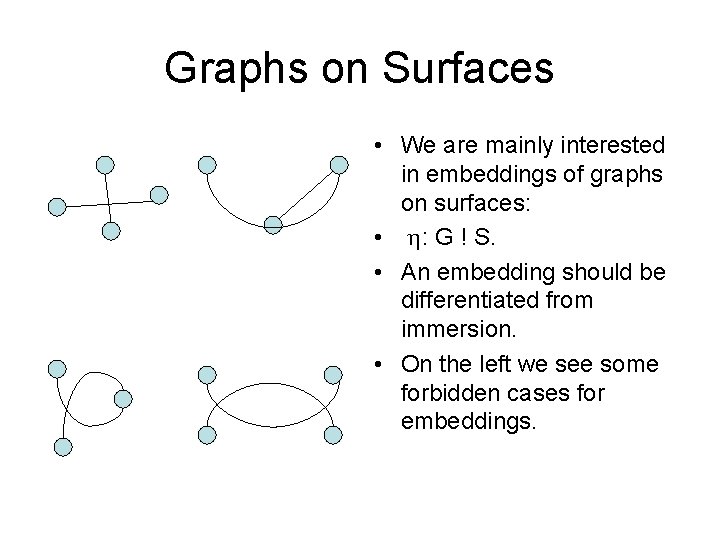

Graphs on Surfaces • We are mainly interested in embeddings of graphs on surfaces: • h: G ! S. • An embedding should be differentiated from immersion. • On the left we see some forbidden cases for embeddings.

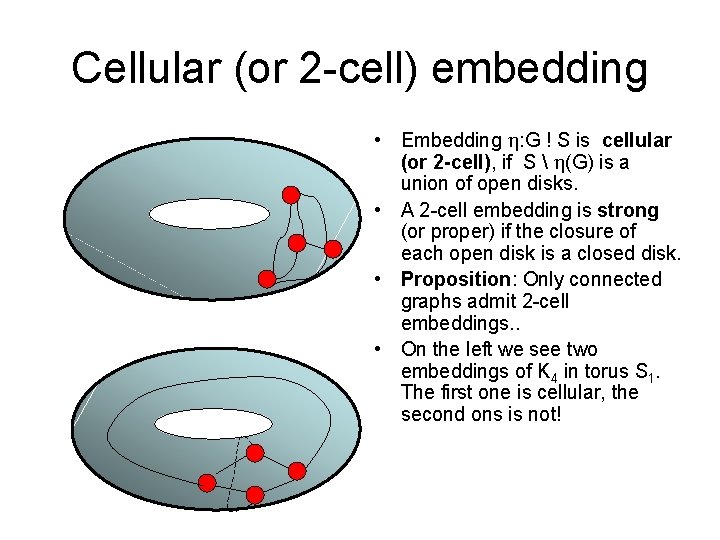

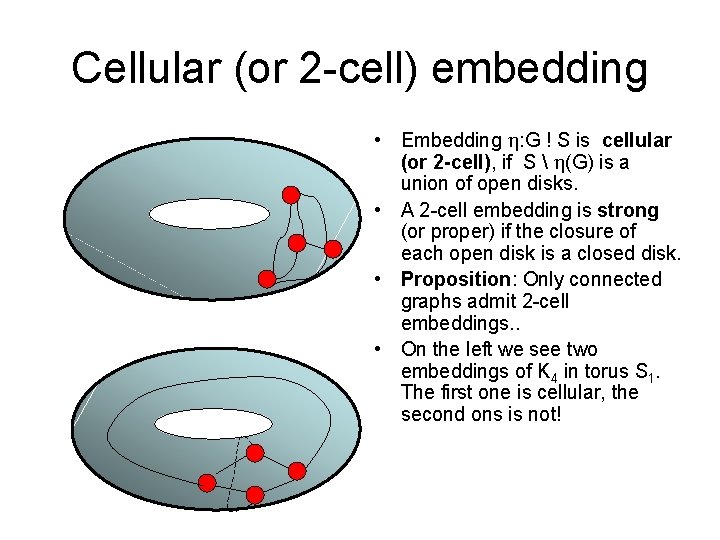

Cellular (or 2 -cell) embedding • Embedding h: G ! S is cellular (or 2 -cell), if S h(G) is a union of open disks. • A 2 -cell embedding is strong (or proper) if the closure of each open disk is a closed disk. • Proposition: Only connected graphs admit 2 -cell embeddings. . • On the left we see two embeddings of K 4 in torus S 1. The first one is cellular, the second ons is not!

2 -Cell Embeddings and Maps • 2 -cell embeddings of graphs are also known as maps. There is a subtile difference in the point of view. • In the former the emphasis is given to the graph while in the latter the emphasis is in the map, a structure, composed of vertices, edges and faces. Examples of maps include surfaces of polyhedra. • Maps include different, equivalent, cryptomorphic purely combinatorial definitions that can be used as a foundation of a theory of maps that is independent of topology.

Genus of a Graph • Let (G) denote the genus of a graph G. This parameter denotes the minimal integer k, such that G admits an embedding into an orientable surface of genus k. • Note: (G) = 0 if and only if G is planar.

Euler Characteristics • To each closed surface S we associate a number (S) called Euler characteristics of S. • (Sg) = 2 – 2 g, for orientable surface of genus g. • (Nk) = 2 – k, for non-orientable surface of crosscap number (non-orientable genus) k.

Euler Formula • Let G be a graph with v vertices, e edges cellularly embedded in surface S with f faces. Then • v – e + f = (S).

Rotation Scheme • Let G be a connected graph with the vertex set V, with arcs S and edges E. For each v 2 V define the set: S[v] = {s 2 S| i(s) = v}. Let and be mappings: • : S ! S • : S !{-1, +1}. • with the property: • Permutation acts cyclically on S[v], for each v 2 V. • (s) = -1(r(s)), for each s 2 S. [Hence is a voltage assignment. In our case: (s) = (r(s))]. • The triple (G, , ) is a called a rotation scheme, defining a 2 -cell embedding of G into some surface.

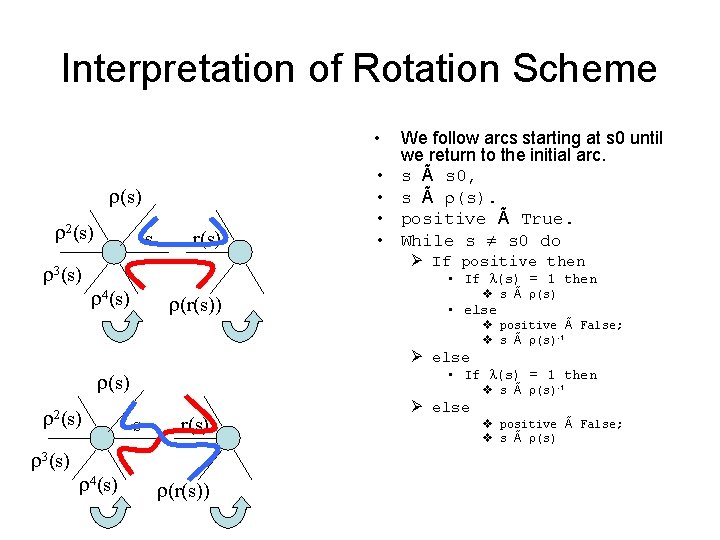

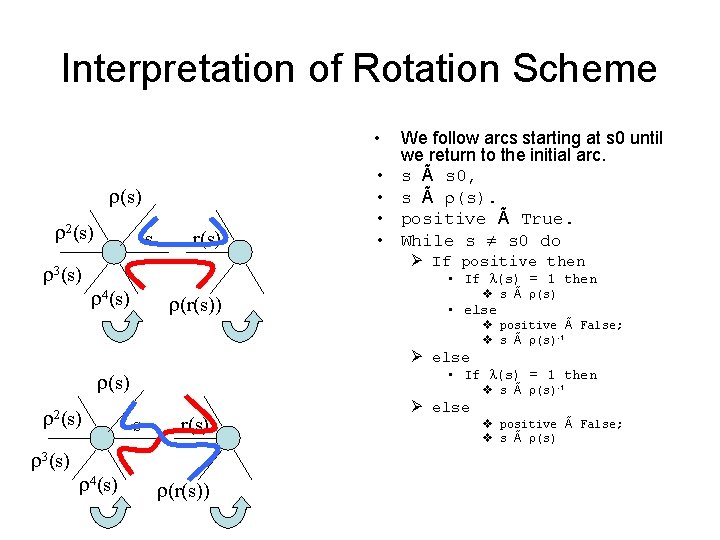

Interpretation of Rotation Scheme • (s) 2(s) 3(s) s r(s) • • We follow arcs starting at s 0 until we return to the initial arc. s à s 0, s à (s). positive à True. While s s 0 do Ø If positive then • If (s) = 1 then 4(s) (r(s)) v s à (s) • else Ø else • If (s) = 1 then (s) 2(s) 3(s) 4(s) v positive à False; v s à (s)-1 s r(s) (r(s)) Ø else v s à (s)-1 v positive à False; v s à (s)

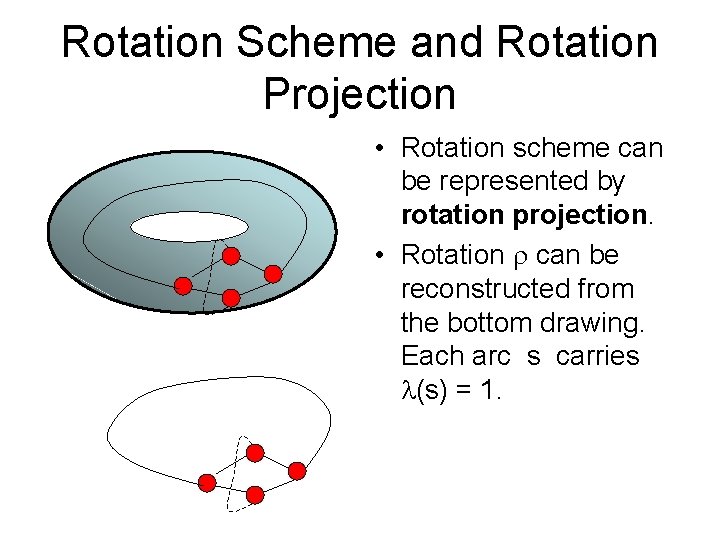

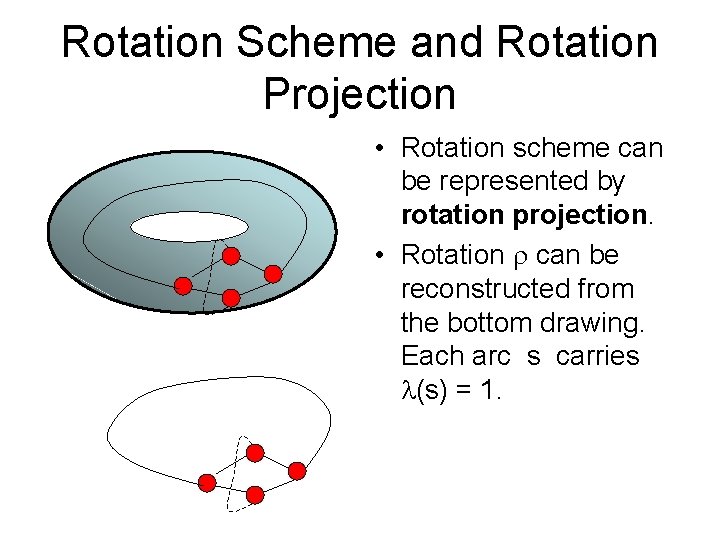

Rotation Scheme and Rotation Projection • Rotation scheme can be represented by rotation projection. • Rotation can be reconstructed from the bottom drawing. Each arc s carries (s) = 1.

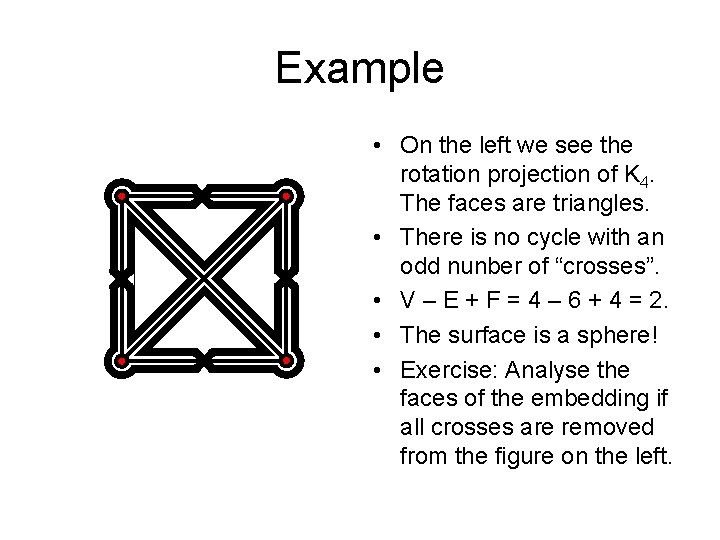

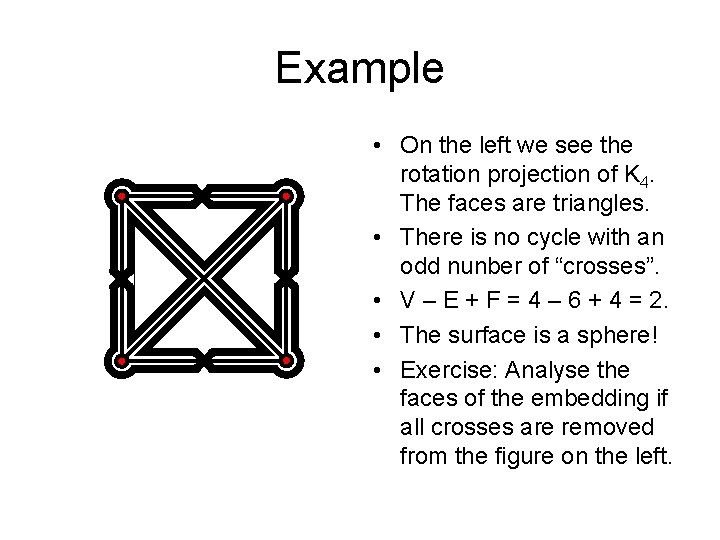

Example • On the left we see the rotation projection of K 4. The faces are triangles. • There is no cycle with an odd nunber of “crosses”. • V – E + F = 4 – 6 + 4 = 2. • The surface is a sphere! • Exercise: Analyse the faces of the embedding if all crosses are removed from the figure on the left.

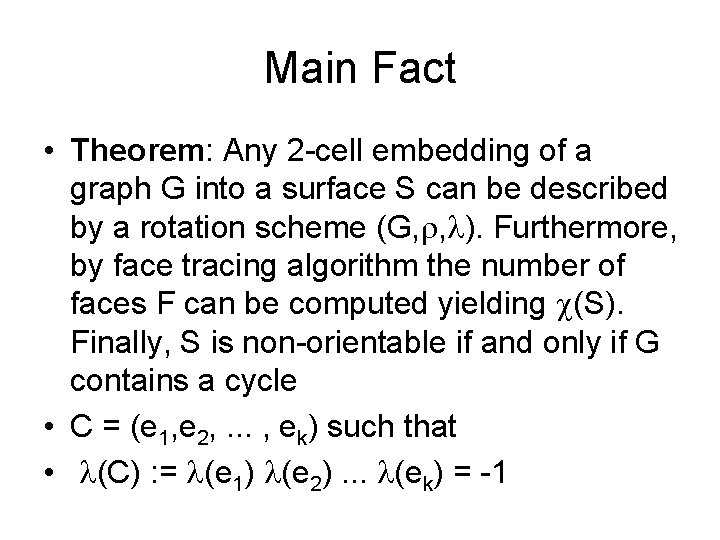

Main Fact • Theorem: Any 2 -cell embedding of a graph G into a surface S can be described by a rotation scheme (G, , ). Furthermore, by face tracing algorithm the number of faces F can be computed yielding (S). Finally, S is non-orientable if and only if G contains a cycle • C = (e 1, e 2, . . . , ek) such that • (C) : = (e 1) (e 2). . . (ek) = -1

Combinatorial Theory of Maps • There are several cryptomorphic definitions of maps (graphs on surfaces. ) • Rotation schemes represent such a tool. • Note that we start with a graph G and additional information (G, , ) in order to describe its 2 -cell embedding. In some closed surface. • We may also start directly from maps or polyhedra.

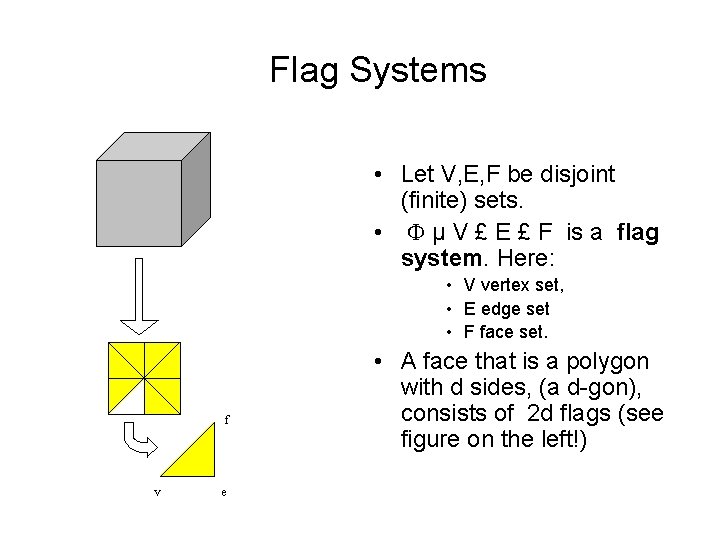

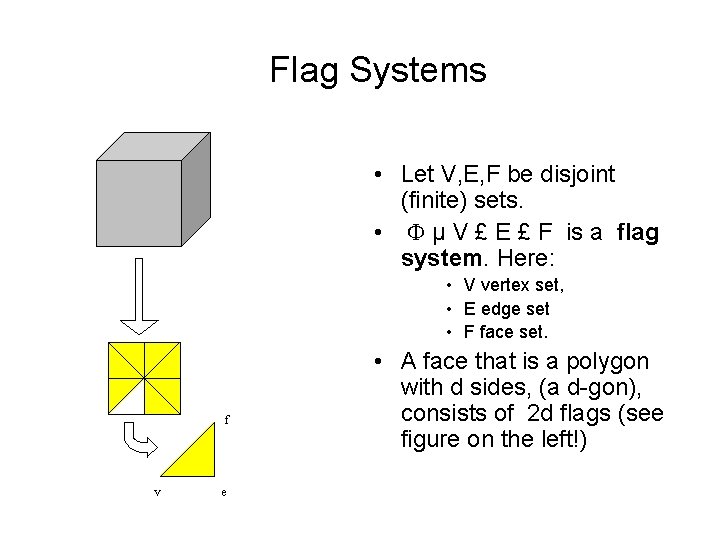

Flag Systems • Let V, E, F be disjoint (finite) sets. • µ V £ E £ F is a flag system. Here: • V vertex set, • E edge set • F face set. f v e • A face that is a polygon with d sides, (a d-gon), consists of 2 d flags (see figure on the left!)

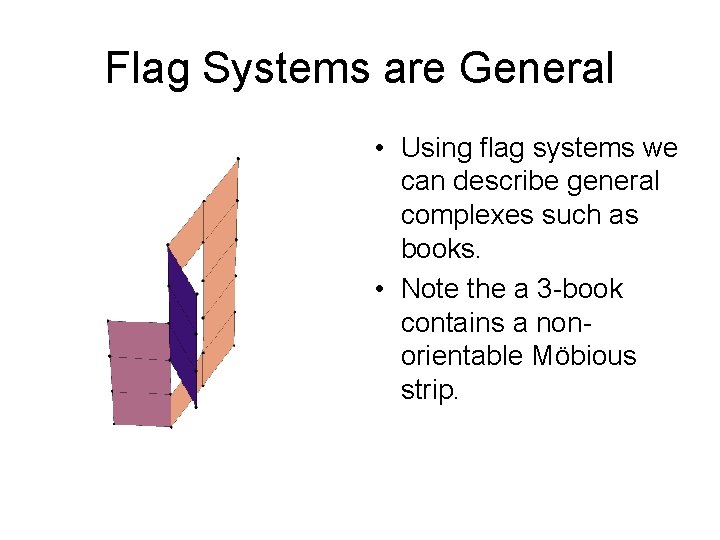

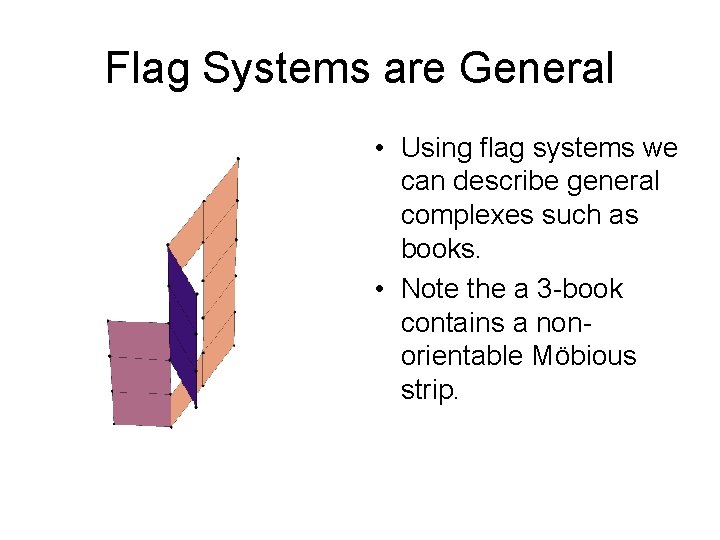

Flag Systems are General • Using flag systems we can describe general complexes such as books. • Note the a 3 -book contains a nonorientable Möbious strip.

Flag systems from 2 -cell embeddings • To a 2 -cell embedding we associate a flag system as follows. Let V be the set of vertices, E, the set of edges and F the set of faces of the embedding. Define • µ V £ E £ F as follows: • (v, e, f) 2 if and only if v, e, and f are pairwise incident.

The 1 -skeleton of a flag system. • Given a flag system µ V £ E £ F, we may study its projection to the first two factors: • A = {(v, e)| (v, e, f) 2 }. • Define: • i: A ! V by i: (v, e) v and • Ve = {v 2 V| (v, e) 2 A}. • Assume |Ve| · 2, for each e 2 E. • We may define r: A ! A by: • r(v, e) = (w, e) if Ve = {v, w} and • r(v, e) = (v, e) if Ve = {v}. • The quadruple (V, A, i, r) is a pre-graph. It is called the 1 -skeleton of . • Given there is an easy test whether the 1 -skeleton is indeed a graph: for each e 2 E we must indeed have |Ve| = 2.

1 -co-skeleton • If we replace the role of V and F in a flag system µ V £ E £ F we obtain a 1 -coskeleton. • We say that the skeleton and co-skeleton are dual graphs.

Homework H 1: If one of 1 -skeleton is a graph is the 1 co-skeleton a graph too? Prove or find a counterexample.

Exercises • N 1. Determine the flag system describing the four-sided pyramid. • N 2. Determine the 1 -skeleton and 1 -coskeleton for N 1. • N 3. Define the notion of automorphism of a flag system . For the case N 1 find the orbits of Aut .

When does a flag system define a surface? • • • As we have seen in the case of a book we may have an edge belonging to more than two faces. This clearly violates the rule that each point on a surface has a neighborhood homeomorphic to an open disk. Therefore a necessary condition is: Each for each flag (v, e, f) 2 there must exist a unique triple (v’, e’, f’) 2 V £ E £ F with v’ v, e’ e, f’ f such that (v’, e, f), (v, e’, f), (v, e, f’) 2 . Another obvious condition is that the 1 -skeleton must be connected. However, a flag system satisfying these two conditions may still represent more general spaces than surfaces. It may represent a pseudosurface. Let us define: Ø v = {(f, e)| (v, e, f) 2 }. Ø e = {(v, f)|(v, e, f) 2 }. Ø f = {(v, e}| (v, e, f) 2 }. Each of the three structures defined above can be represented as graph. More presicely, each of them is regular 2 -valent graph. is a surface if and only if each graph v, e and f is connected.

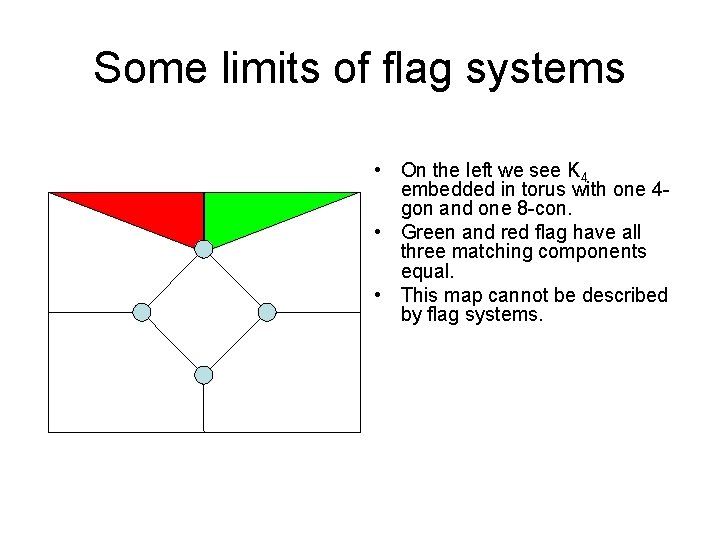

Limits of flag systems • Unfortunately, there are connected graphs whose 2 -cell embeddings cannot be represnted by flag systems. • Proposition. Let G be a connected graph. If G contains a loop or a bridge no 2 -cell embedding of G can be described by flag systems. • [A bridge is an edge whose removal disconnects the graph. ]

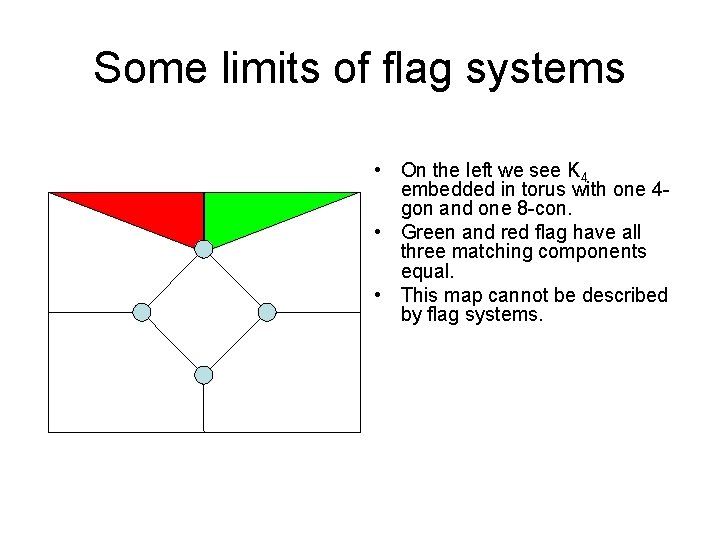

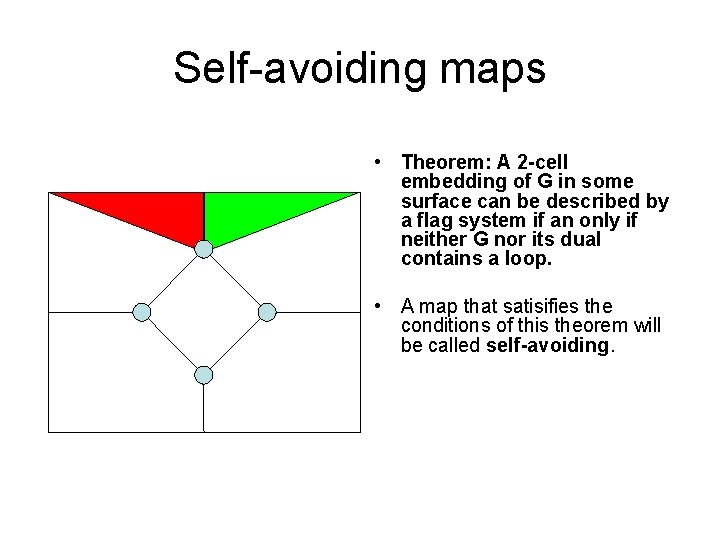

Some limits of flag systems • On the left we see K 4 embedded in torus with one 4 gon and one 8 -con. • Green and red flag have all three matching components equal. • This map cannot be described by flag systems.

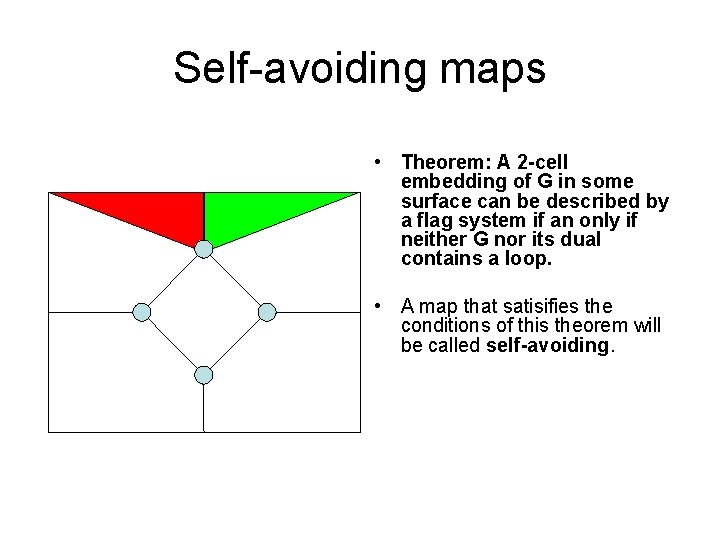

Self-avoiding maps • Theorem: A 2 -cell embedding of G in some surface can be described by a flag system if an only if neither G nor its dual contains a loop. • A map that satisifies the conditions of this theorem will be called self-avoiding.

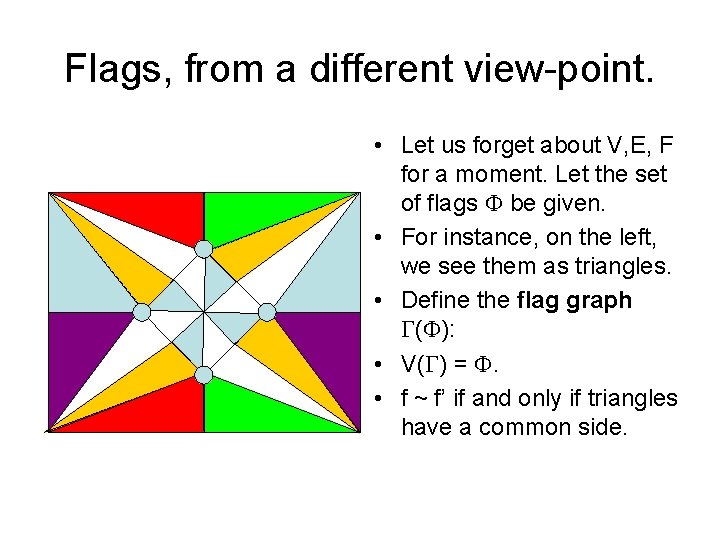

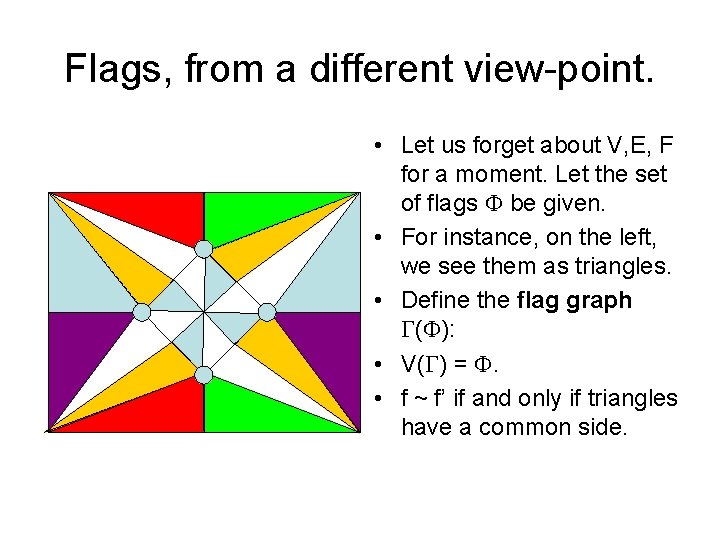

Flags, from a different view-point. • Let us forget about V, E, F for a moment. Let the set of flags be given. • For instance, on the left, we see them as triangles. • Define the flag graph ( ): • V( ) = . • f ~ f’ if and only if triangles have a common side.

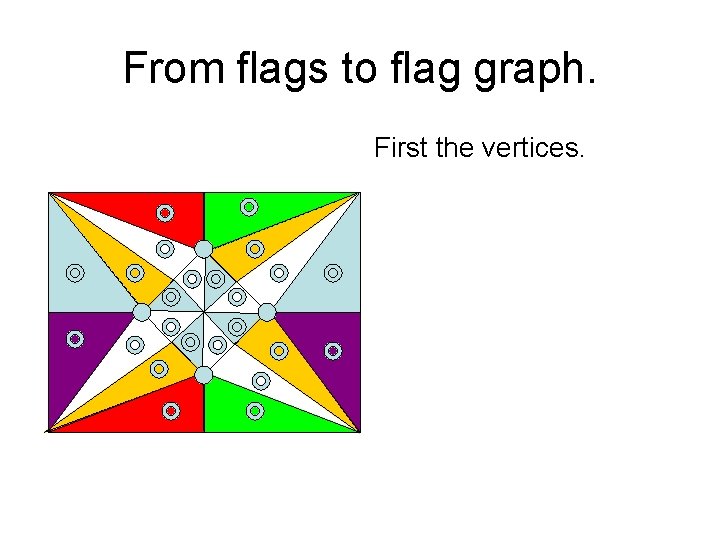

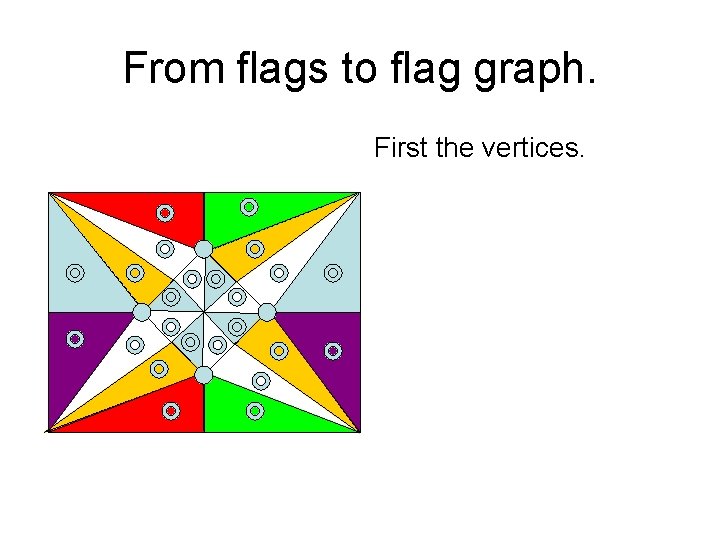

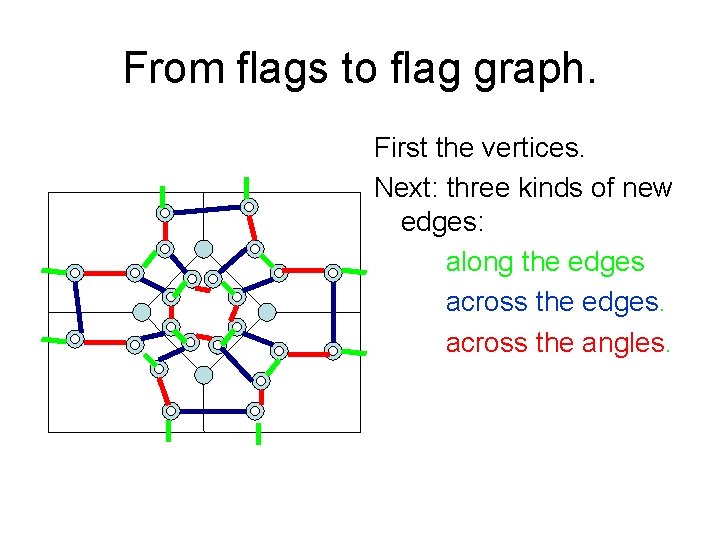

From flags to flag graph. First the vertices.

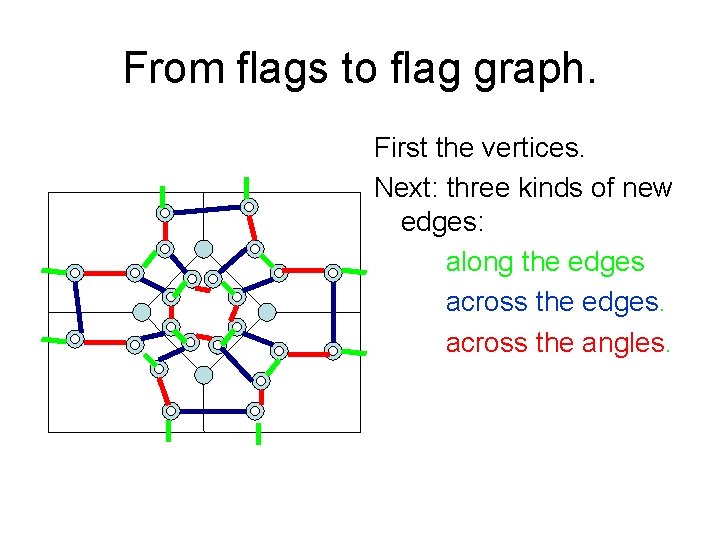

From flags to flag graph. First the vertices. Next: three kinds of new edges: along the edges across the edges. across the angles.

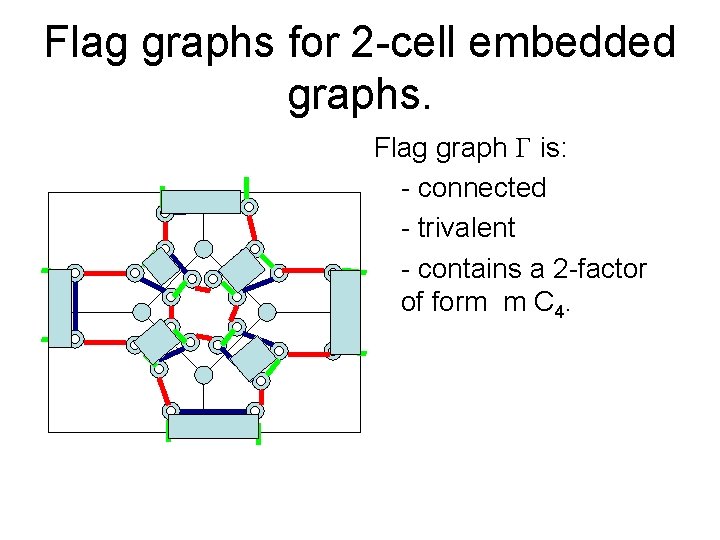

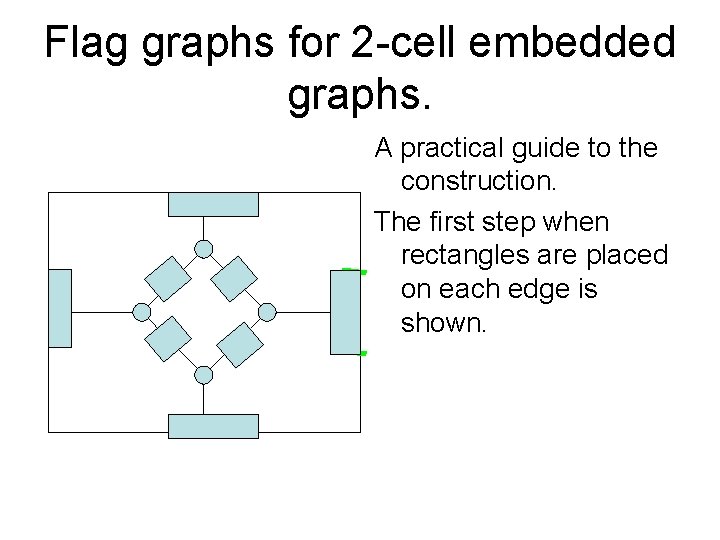

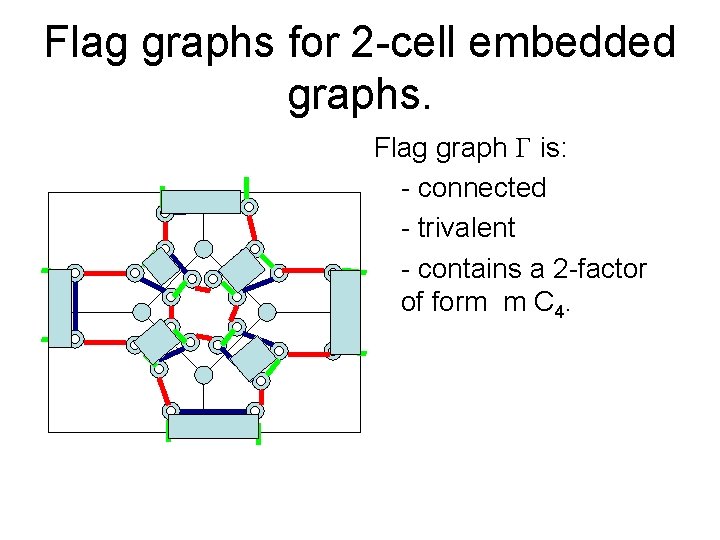

Flag graphs for 2 -cell embedded graphs. Flag graph is: - connected - trivalent - contains a 2 -factor of form m C 4.

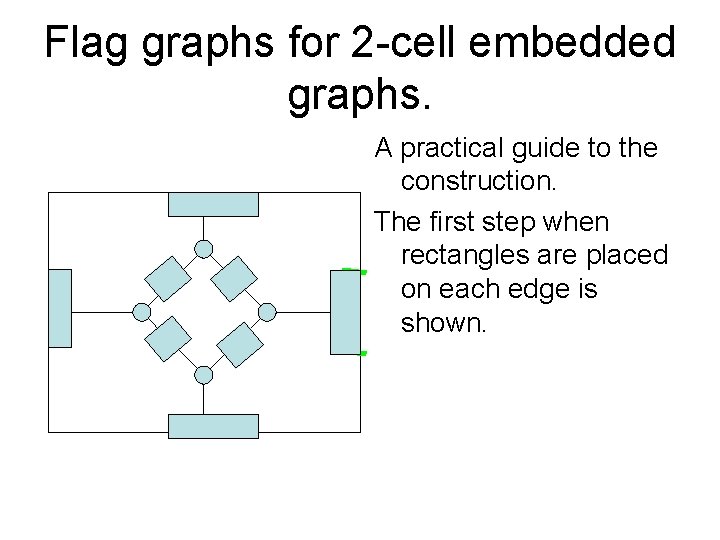

Flag graphs for 2 -cell embedded graphs. A practical guide to the construction. The first step when rectangles are placed on each edge is shown.

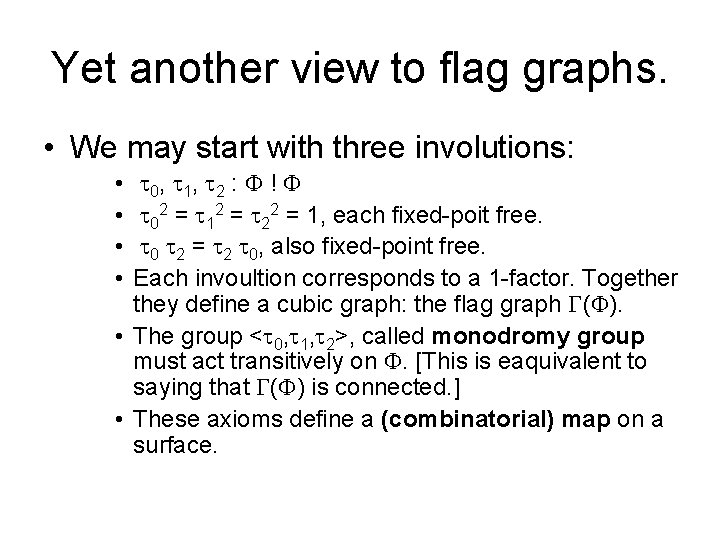

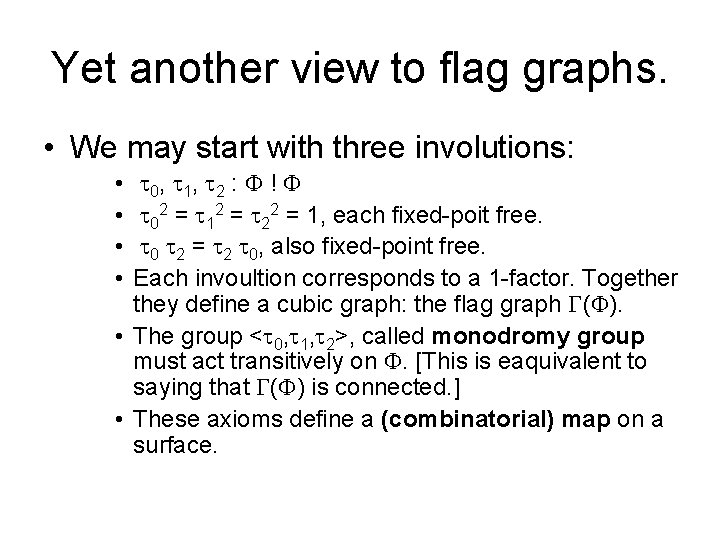

Yet another view to flag graphs. • We may start with three involutions: 0, 1, 2 : ! 02 = 12 = 22 = 1, each fixed-poit free. 0 2 = 2 0, also fixed-point free. Each invoultion corresponds to a 1 -factor. Together they define a cubic graph: the flag graph ( ). • The group < 0, 1, 2>, called monodromy group must act transitively on . [This is eaquivalent to saying that ( ) is connected. ] • These axioms define a (combinatorial) map on a surface. • •

Combinatorial Map. • Combinatorial map is defined by three involutions satisfying the axioms from the previous slide. • Orbits of < 2, 1> acting on define V. • Orbits of < 0, 2> acting on define E. • Orbits of < 0, 1> acting on define F.

Orientable Map • Theorem: A map is orientable if and only if the flag graph is bipartite.

Unique Embedding • Theorem (Whitney): Each 3 -connected planar graph admits a unique embedding in the sphere. • Theorem (Mani). Let Aut G be the group of automorphism of a 3 -connectede planar graph G and let Aut M be the group of automorphisms of the corresponding map. Then Aut G = Aut M.

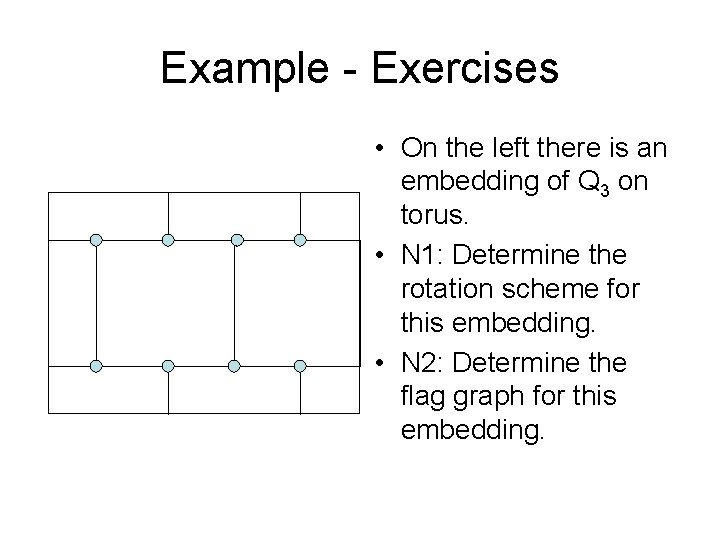

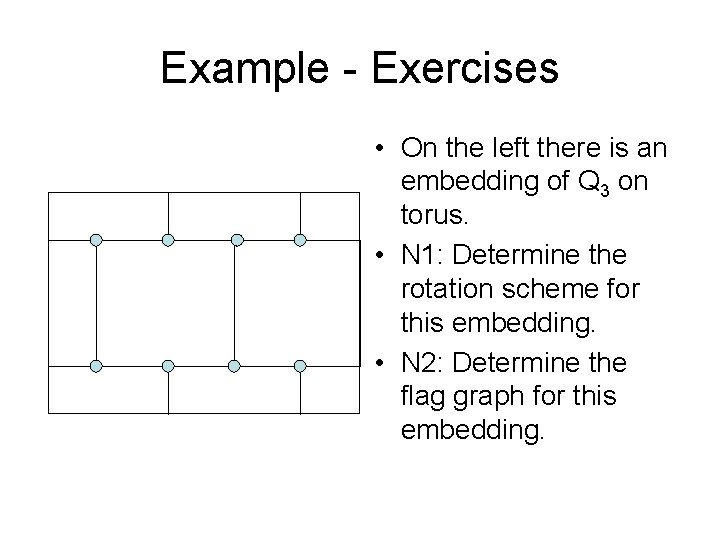

Example - Exercises • On the left there is an embedding of Q 3 on torus. • N 1: Determine the rotation scheme for this embedding. • N 2: Determine the flag graph for this embedding.

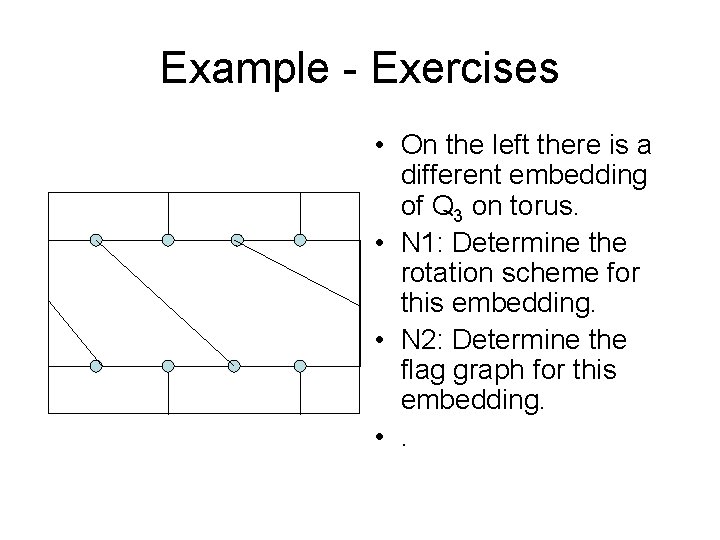

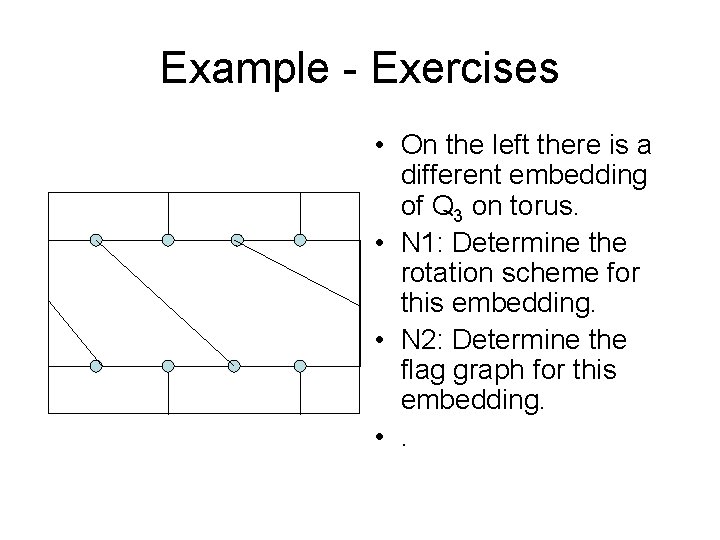

Example - Exercises • On the left there is a different embedding of Q 3 on torus. • N 1: Determine the rotation scheme for this embedding. • N 2: Determine the flag graph for this embedding. • .

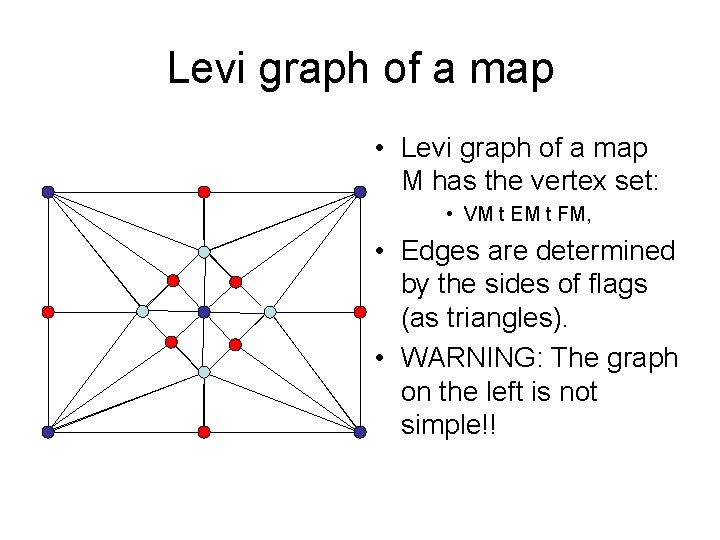

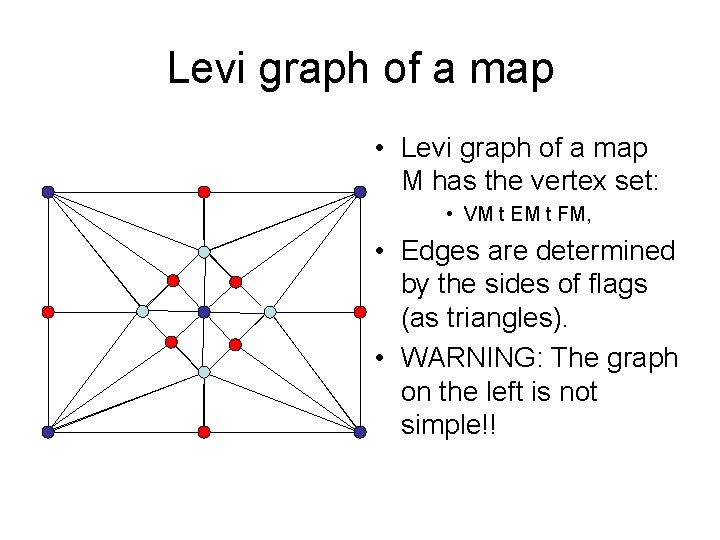

Levi graph of a map • Levi graph of a map M has the vertex set: • VM t EM t FM, • Edges are determined by the sides of flags (as triangles). • WARNING: The graph on the left is not simple!!

Characterisation • Theorem: Levi graph of a map is simple if neither 1 -skeleton nor 1 -co-skeleton has a loop. • Definition: A map M is simple, if and only if its Levi graph is simple.

Homework • H 1: Given Flag graph of a map M, determine whether M is simple! (Prove previous theorem)