Management of patients with STEMI what do the

- Slides: 32

Management of patients with STEMI: what do the latest guidelines recommend? February 2018

What is STEMI? ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction STEMI is a type of AMI defined by characteristic symptoms of myocardial ischaemia in association with persistent ECG ST-segment elevation AMI is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide AMI, acute myocardial infarction Thygesen K et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60: 1581– 98

Reperfusion strategies in STEMI Invasive Pharmacological Pharmaco-invasive primary PCI induction of thrombolysis by thrombolytic agent a combination of both approaches Early reperfusion aims to limit the extent of myocardial damage and lead to better outcomes in patients with STEMI PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention Steg PG et al. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2569– 619

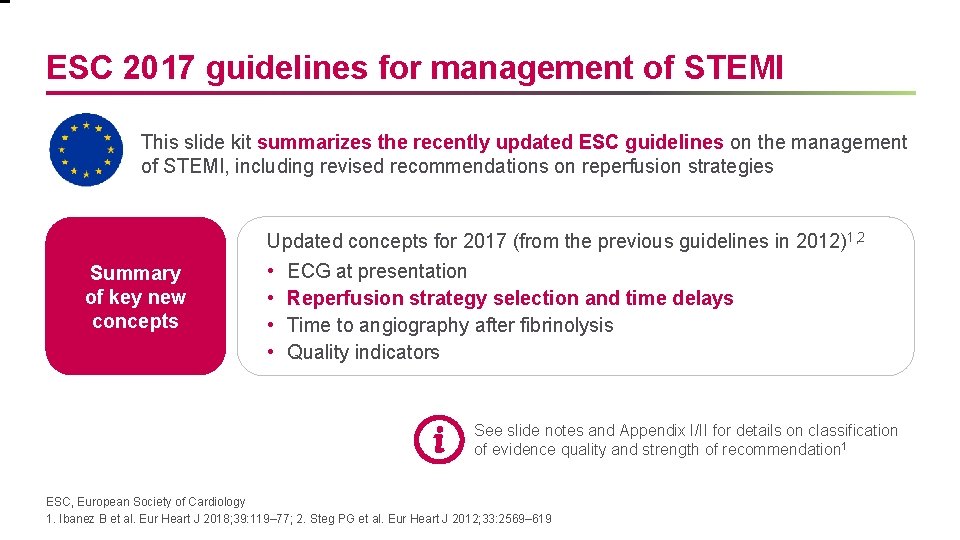

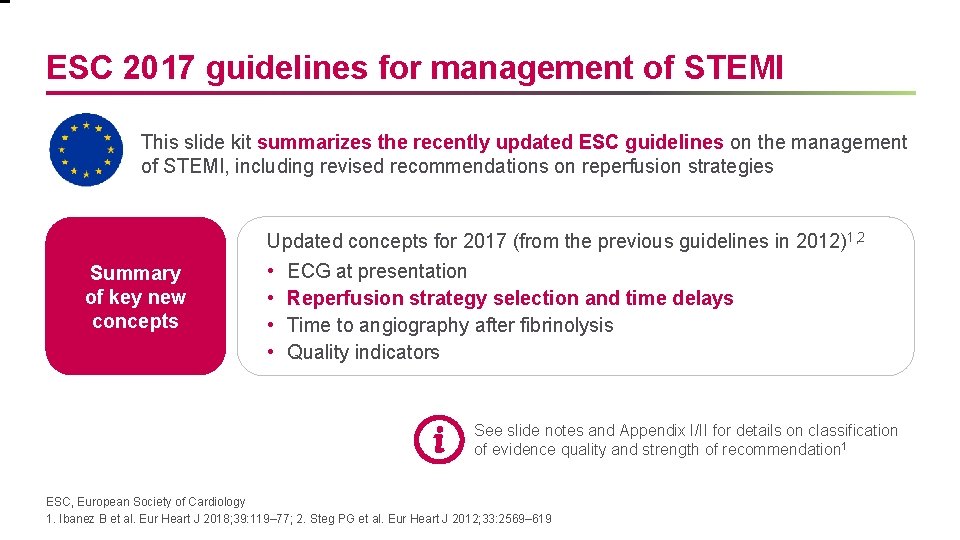

ESC 2017 guidelines for management of STEMI This slide kit summarizes the recently updated ESC guidelines on the management of STEMI, including revised recommendations on reperfusion strategies Summary of key new concepts Updated concepts for 2017 (from the previous guidelines in 2012)1, 2 • ECG at presentation • Reperfusion strategy selection and time delays • Time to angiography after fibrinolysis • Quality indicators See slide notes and Appendix I/II for details on classification of evidence quality and strength of recommendation 1 ESC, European Society of Cardiology 1. Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77; 2. Steg PG et al. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2569– 619

Other guidelines for management of STEMI This slide kit also compares the ESC 2017 guidelines with US guidelines In the USA, the most recent guidelines are: 1. 2013 ACCF/AHA guidelines for management of STEMI 1 2. 2015 AHA guidelines* update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency CV care 2 *The ILCOR ACS Task Force did not review areas in which it found a paucity of new evidence between 2010 and 2015; therefore, the 2010 guidelines 3 for these unreviewed areas remain current. Recommendations that were not reviewed in 2015 will either be reviewed and included in future AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC or will be in the most recent ACC/AHA Guidelines ACCF, American College of Cardiology Foundation; AHA, American Heart Association 1. O’Gara P et al. Circulation 2013; 24; 128: e 481; 2. O’Connor RE et al. Circulation 2015; 132: S 483– 500; 3. O’Connor RE et al. Circulation 2010; 122: S 787– 817

ESC 2017: Diagnosis of STEMI is defined as persistent chest discomfort or other symptoms suggestive of ischaemia and ST-segment elevation in ≥ 2 contiguous leads Key recommendations for initial diagnosis At FMC* 12 -lead ECG as soon as possible (target delay ≤ 10 min) (IB) ECG monitoring with defibrillator capacity as soon as possible in all patients with suspected STEMI (IB) Routine sampling for serum markers as soon as possible in the acute phase, but should not delay reperfusion (IC) *First medical contact (FMC) is defined as the time when the patient is initially assessed by a physician, paramedic, nurse or other trained EMS personnel who can obtain and interpret the ECG and deliver initial interventions, either in the pre-hospital setting or upon arrival at the hospital Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77

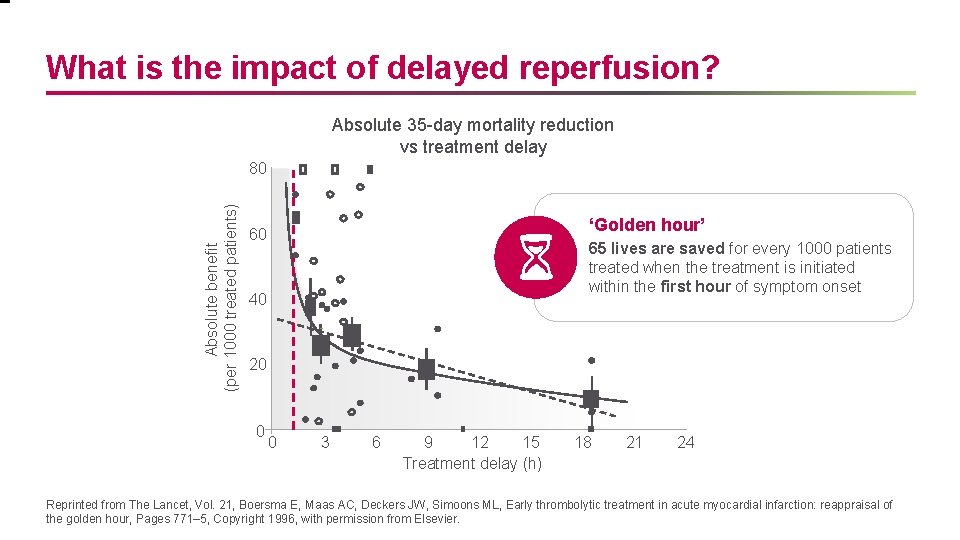

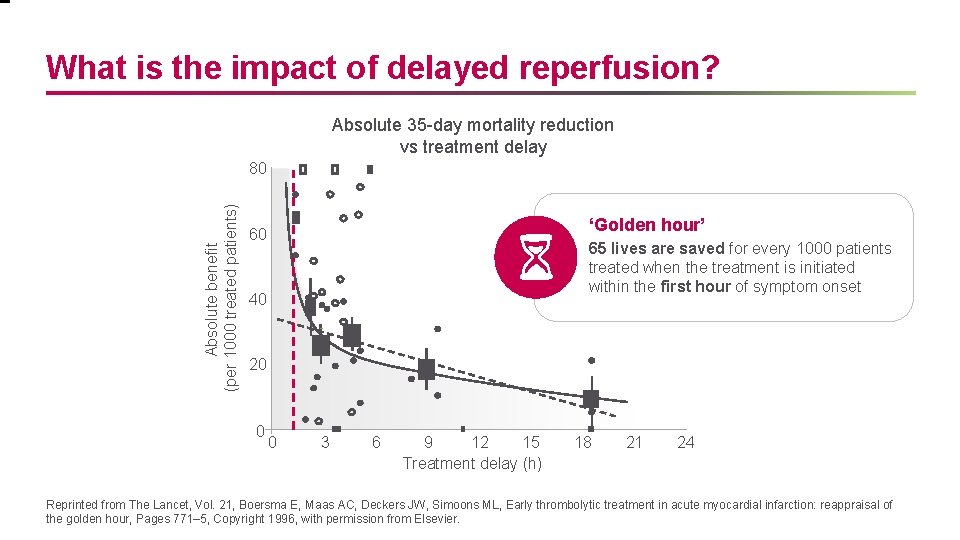

What is the impact of delayed reperfusion? Absolute 35 -day mortality reduction vs treatment delay Absolute benefit (per 1000 treated patients) 80 ‘Golden hour’ 60 65 lives are saved for every 1000 patients treated when the treatment is initiated within the first hour of symptom onset 40 20 0 0 3 6 9 12 15 Treatment delay (h) 18 21 24 Reprinted from The Lancet, Vol. 21, Boersma E, Maas AC, Deckers JW, Simoons ML, Early thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarction: reappraisal of the golden hour, Pages 771– 5, Copyright 1996, with permission from Elsevier.

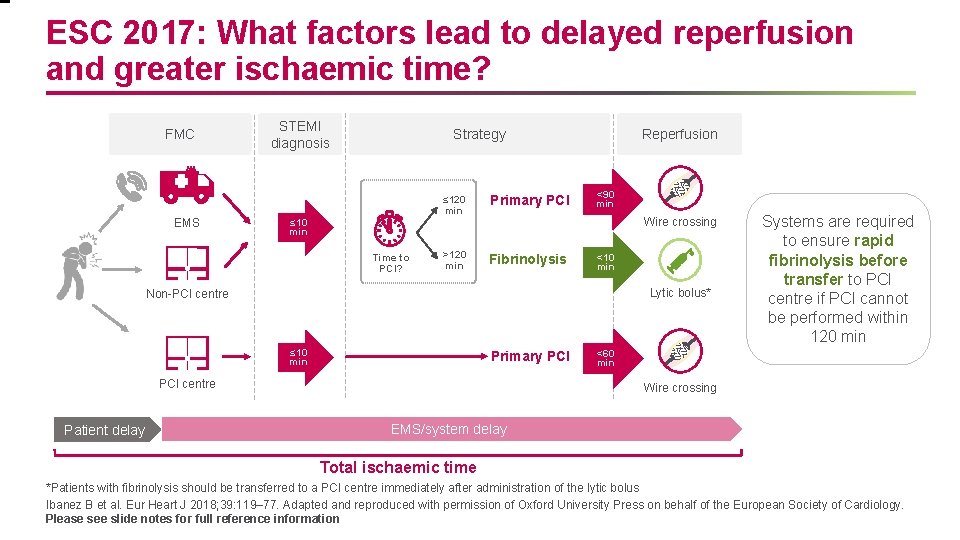

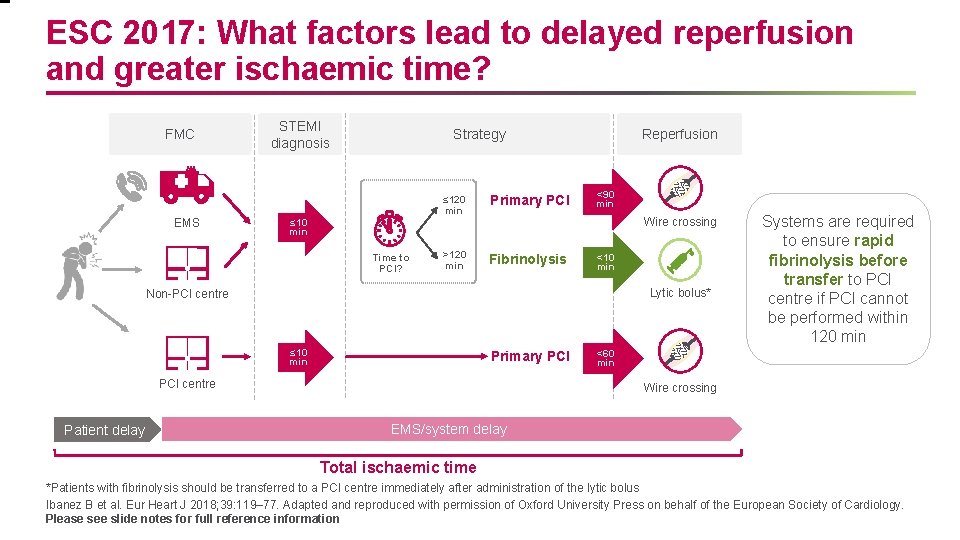

ESC 2017: What factors lead to delayed reperfusion and greater ischaemic time? FMC EMS STEMI diagnosis Strategy ≤ 120 min Primary PCI >120 min Fibrinolysis Reperfusion <90 min Wire crossing ≤ 10 min Time to PCI? <10 min Lytic bolus* Non-PCI centre ≤ 10 min Primary PCI centre Patient delay Systems are required to ensure rapid fibrinolysis before transfer to PCI centre if PCI cannot be performed within 120 min <60 min Wire crossing EMS/system delay Total ischaemic time *Patients with fibrinolysis should be transferred to a PCI centre immediately after administration of the lytic bolus Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77. Adapted and reproduced with permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology. Please see slide notes for full reference information

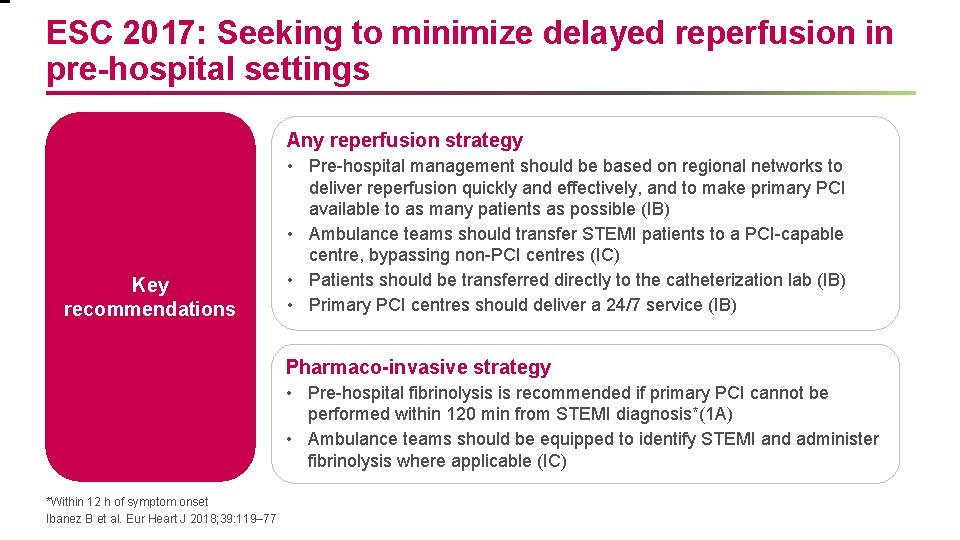

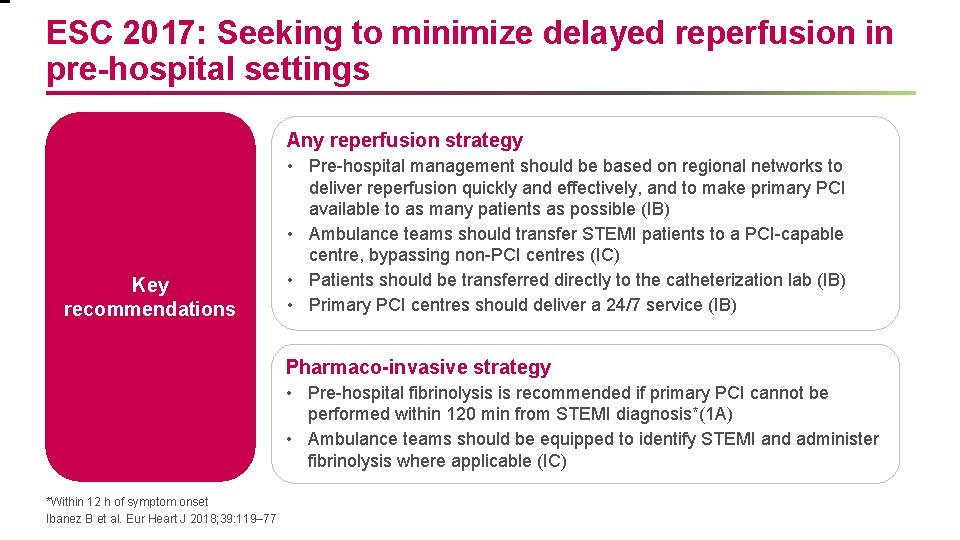

ESC 2017: Seeking to minimize delayed reperfusion in pre-hospital settings Any reperfusion strategy Key recommendations • Pre-hospital management should be based on regional networks to deliver reperfusion quickly and effectively, and to make primary PCI available to as many patients as possible (IB) • Ambulance teams should transfer STEMI patients to a PCI-capable centre, bypassing non-PCI centres (IC) • Patients should be transferred directly to the catheterization lab (IB) • Primary PCI centres should deliver a 24/7 service (IB) Pharmaco-invasive strategy • Pre-hospital fibrinolysis is recommended if primary PCI cannot be performed within 120 min from STEMI diagnosis*(1 A) • Ambulance teams should be equipped to identify STEMI and administer fibrinolysis where applicable (IC) *Within 12 h of symptom onset Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77

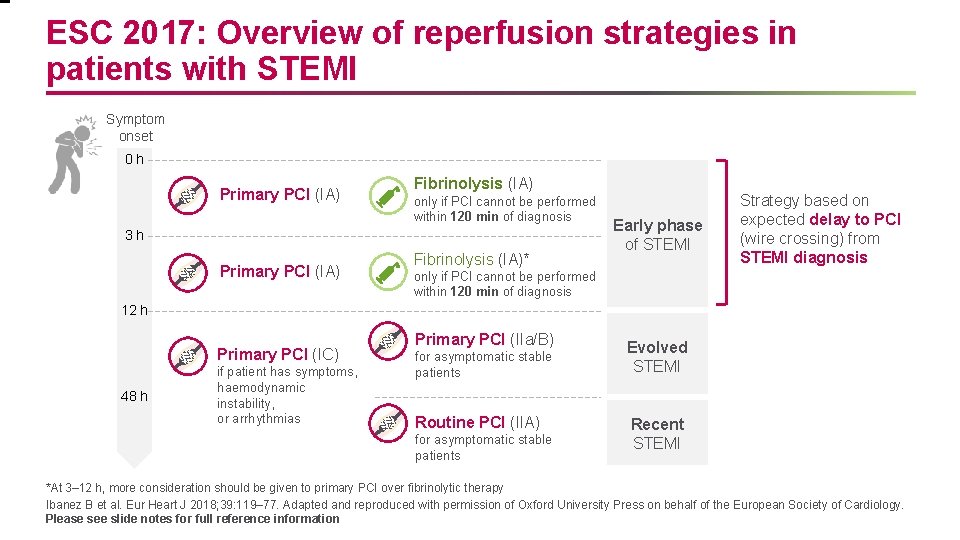

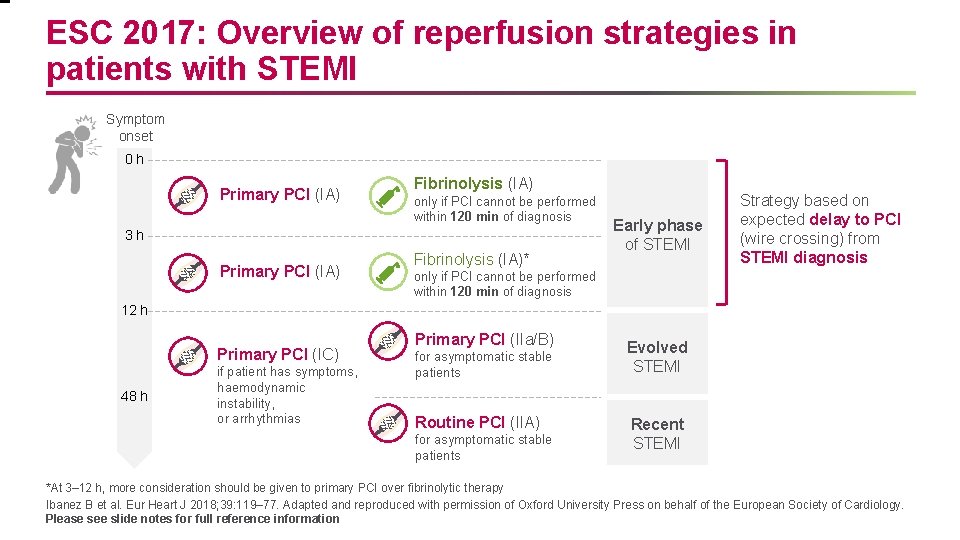

ESC 2017: Overview of reperfusion strategies in patients with STEMI Symptom onset 0 h Primary PCI (IA) Fibrinolysis (IA) only if PCI cannot be performed within 120 min of diagnosis 3 h Primary PCI (IA) Fibrinolysis (IA)* Early phase of STEMI Strategy based on expected delay to PCI (wire crossing) from STEMI diagnosis only if PCI cannot be performed within 120 min of diagnosis 12 h Primary PCI (IC) 48 h if patient has symptoms, haemodynamic instability, or arrhythmias Primary PCI (IIa/B) for asymptomatic stable patients Routine PCI (IIA) for asymptomatic stable patients Evolved STEMI Recent STEMI *At 3– 12 h, more consideration should be given to primary PCI over fibrinolytic therapy Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77. Adapted and reproduced with permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology. Please see slide notes for full reference information

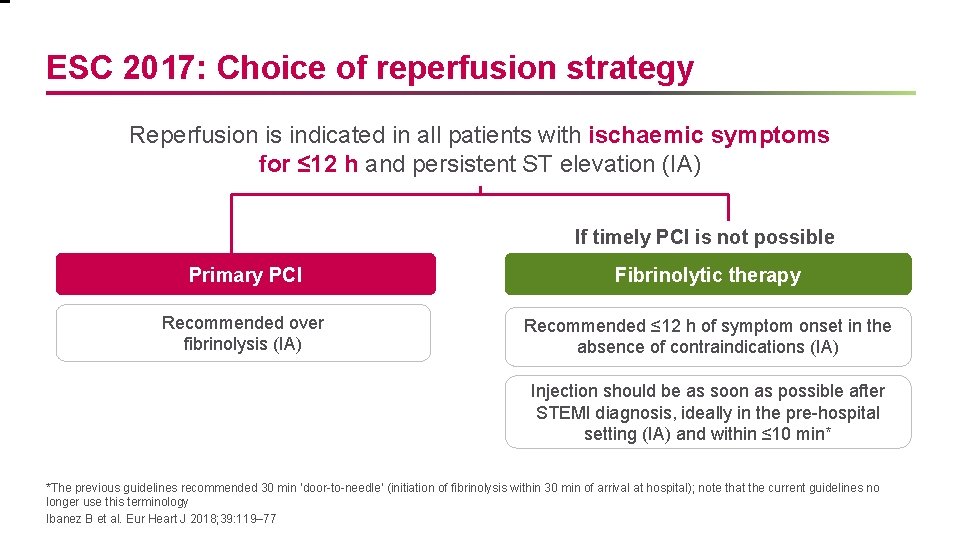

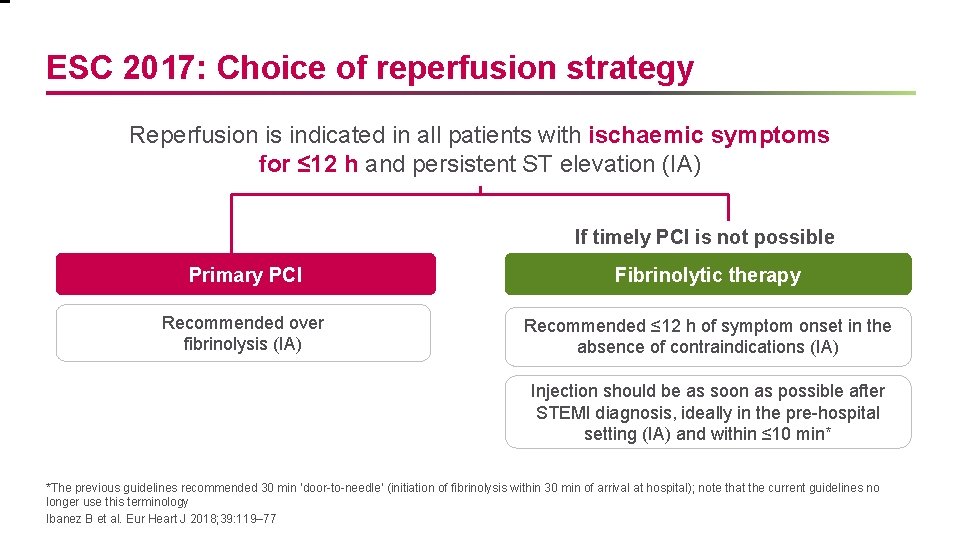

ESC 2017: Choice of reperfusion strategy Reperfusion is indicated in all patients with ischaemic symptoms for ≤ 12 h and persistent ST elevation (IA) If timely PCI is not possible Primary PCI Fibrinolytic therapy Recommended over fibrinolysis (IA) Recommended ≤ 12 h of symptom onset in the absence of contraindications (IA) Injection should be as soon as possible after STEMI diagnosis, ideally in the pre-hospital setting (IA) and within ≤ 10 min* *The previous guidelines recommended 30 min ‘door-to-needle’ (initiation of fibrinolysis within 30 min of arrival at hospital); note that the current guidelines no longer use this terminology Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77

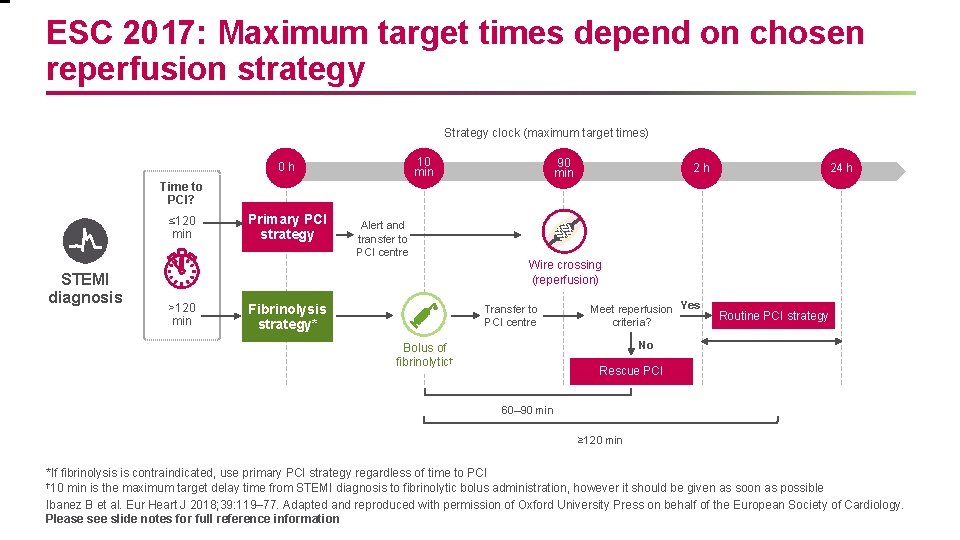

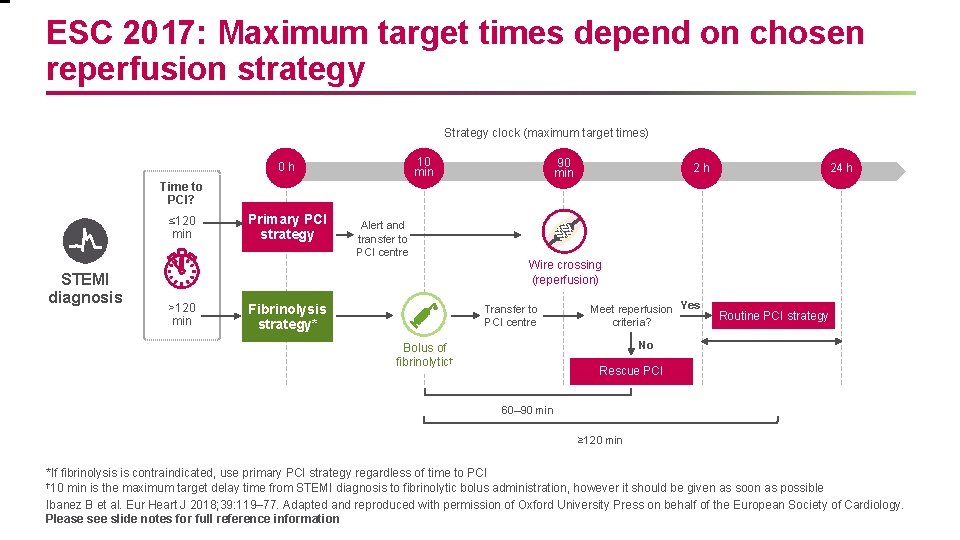

ESC 2017: Maximum target times depend on chosen reperfusion strategy Strategy clock (maximum target times) 10 min 0 h 90 min 2 h 24 h Time to PCI? ≤ 120 min STEMI diagnosis Primary PCI strategy Alert and transfer to PCI centre Wire crossing (reperfusion) >120 min Fibrinolysis strategy* Transfer to PCI centre Meet reperfusion Yes criteria? Routine PCI strategy No Bolus of fibrinolytic† Rescue PCI 60– 90 min ≥ 120 min *If fibrinolysis is contraindicated, use primary PCI strategy regardless of time to PCI † 10 min is the maximum target delay time from STEMI diagnosis to fibrinolytic bolus administration, however it should be given as soon as possible Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77. Adapted and reproduced with permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology. Please see slide notes for full reference information

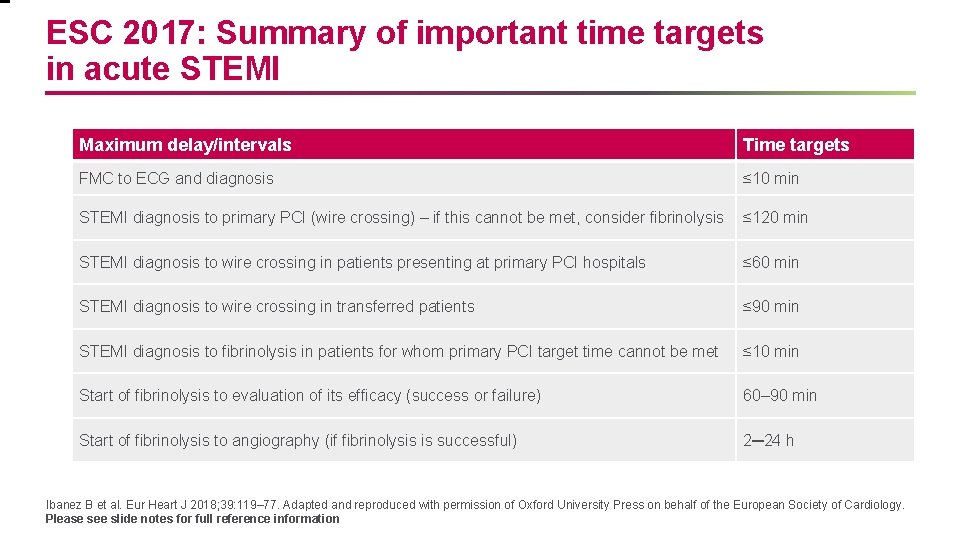

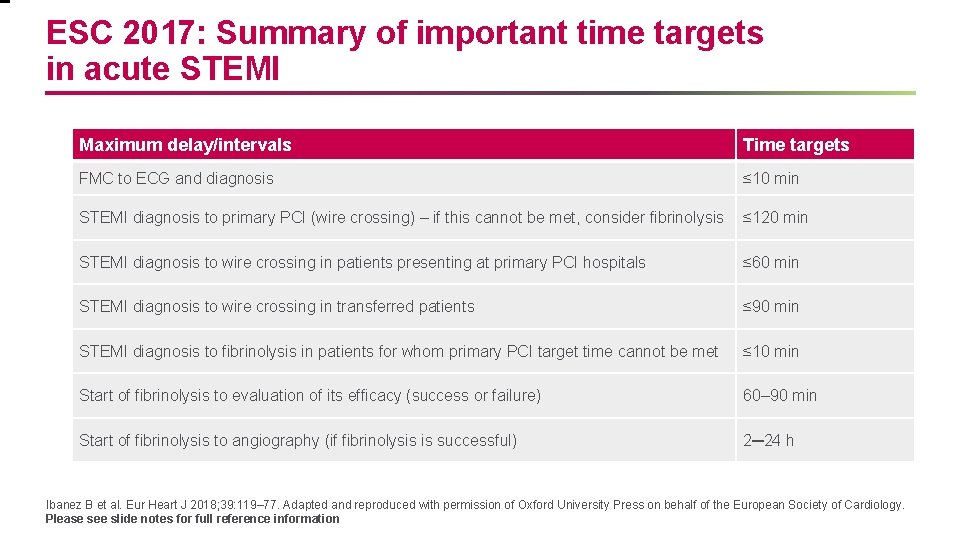

ESC 2017: Summary of important time targets in acute STEMI Maximum delay/intervals Time targets FMC to ECG and diagnosis ≤ 10 min STEMI diagnosis to primary PCI (wire crossing) – if this cannot be met, consider fibrinolysis ≤ 120 min STEMI diagnosis to wire crossing in patients presenting at primary PCI hospitals ≤ 60 min STEMI diagnosis to wire crossing in transferred patients ≤ 90 min STEMI diagnosis to fibrinolysis in patients for whom primary PCI target time cannot be met ≤ 10 min Start of fibrinolysis to evaluation of its efficacy (success or failure) 60– 90 min Start of fibrinolysis to angiography (if fibrinolysis is successful) 2─24 h Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77. Adapted and reproduced with permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology. Please see slide notes for full reference information

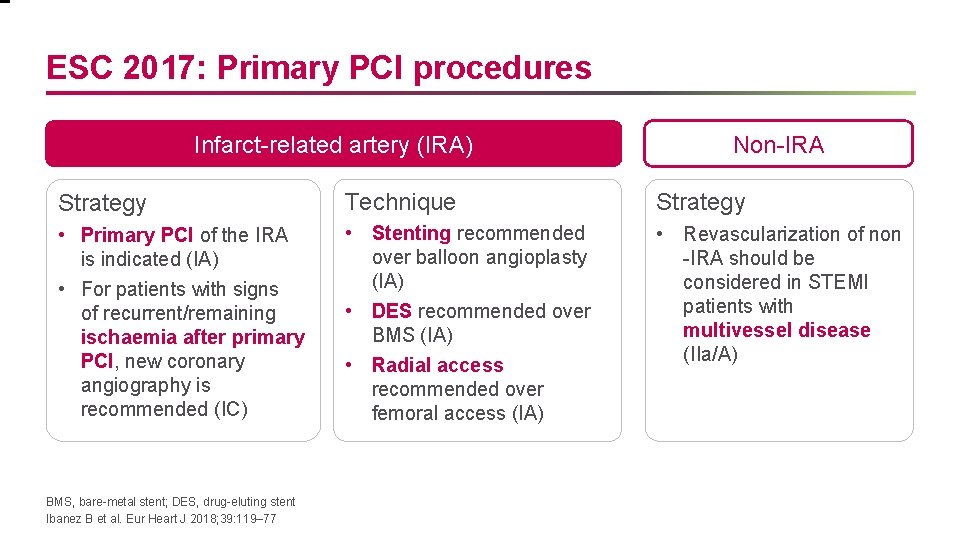

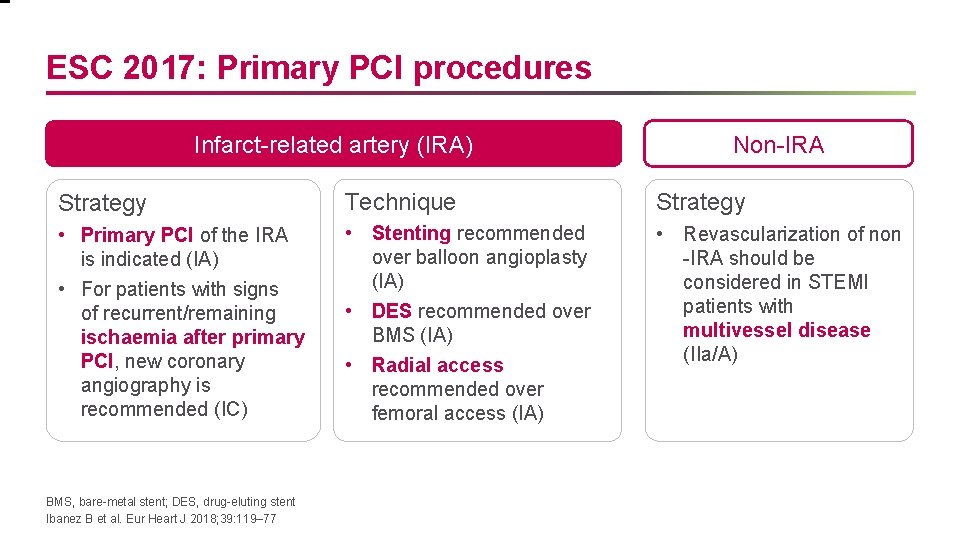

ESC 2017: Primary PCI procedures Infarct-related artery (IRA) Non-IRA Strategy Technique Strategy • Primary PCI of the IRA is indicated (IA) • For patients with signs of recurrent/remaining ischaemia after primary PCI, new coronary angiography is recommended (IC) • Stenting recommended over balloon angioplasty (IA) • DES recommended over BMS (IA) • Radial access recommended over femoral access (IA) • Revascularization of non -IRA should be considered in STEMI patients with multivessel disease (IIa/A) BMS, bare-metal stent; DES, drug-eluting stent Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77

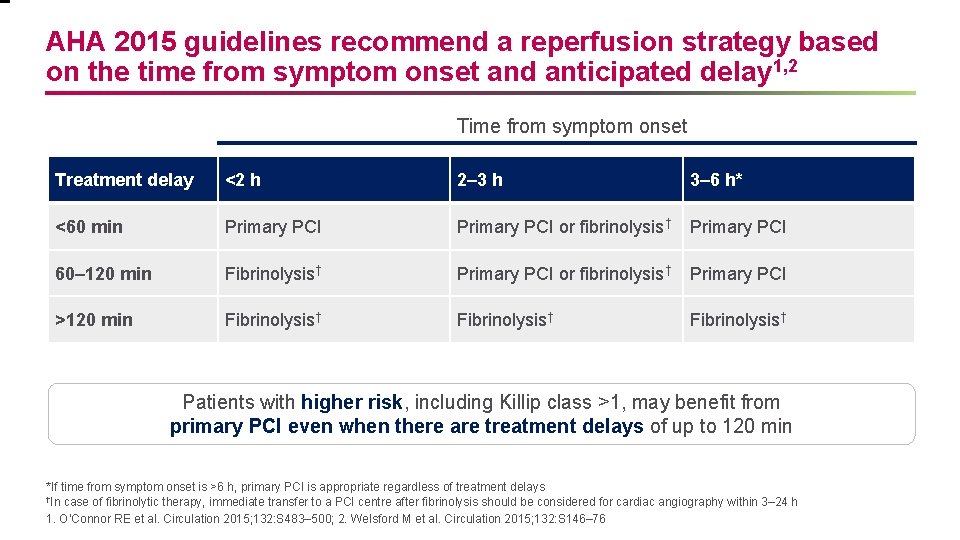

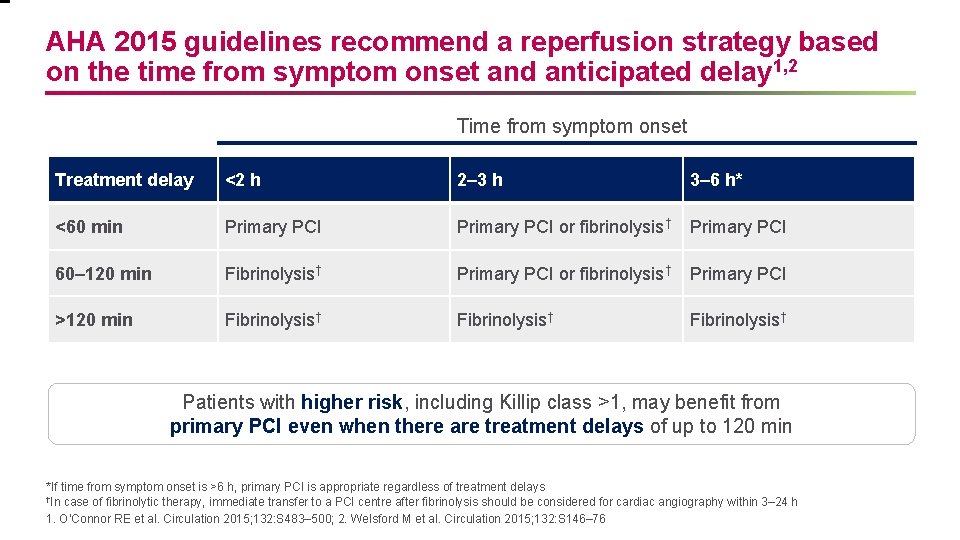

AHA 2015 guidelines recommend a reperfusion strategy based on the time from symptom onset and anticipated delay 1, 2 Time from symptom onset Treatment delay <2 h 2– 3 h 3– 6 h* <60 min Primary PCI or fibrinolysis† Primary PCI 60– 120 min Fibrinolysis† Primary PCI or fibrinolysis† Primary PCI >120 min Fibrinolysis† Patients with higher risk, including Killip class >1, may benefit from primary PCI even when there are treatment delays of up to 120 min *If time from symptom onset is >6 h, primary PCI is appropriate regardless of treatment delays †In case of fibrinolytic therapy, immediate transfer to a PCI centre after fibrinolysis should be considered for cardiac angiography within 3– 24 h 1. O’Connor RE et al. Circulation 2015; 132: S 483– 500; 2. Welsford M et al. Circulation 2015; 132: S 146– 76

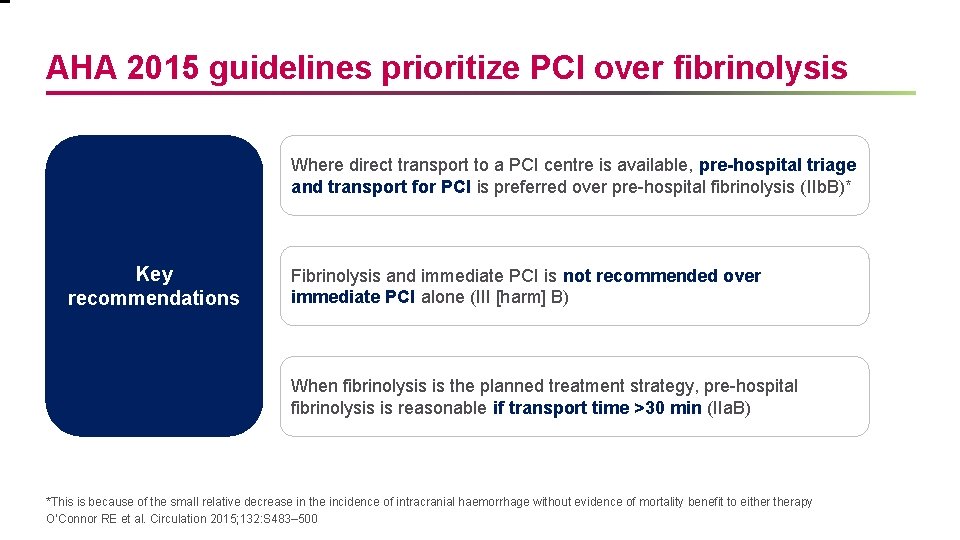

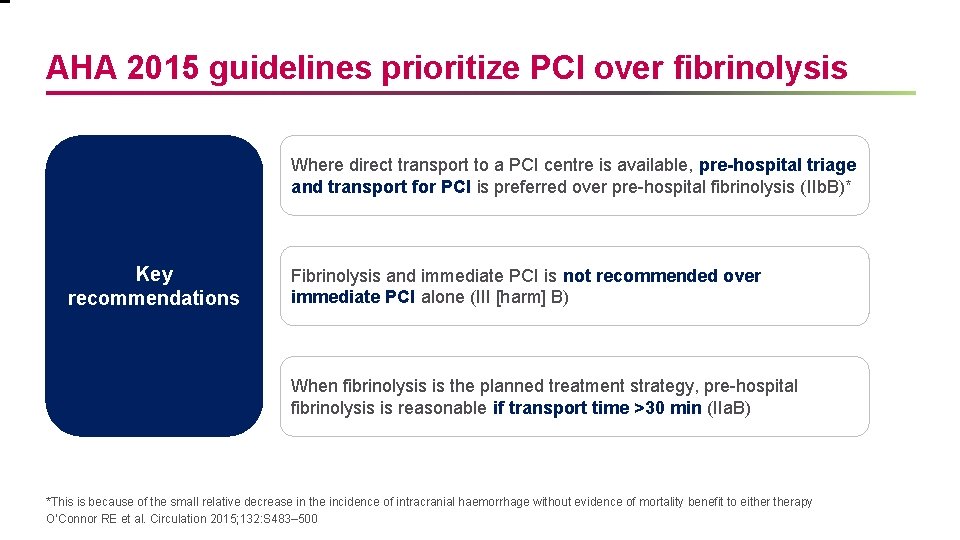

AHA 2015 guidelines prioritize PCI over fibrinolysis Where direct transport to a PCI centre is available, pre-hospital triage and transport for PCI is preferred over pre-hospital fibrinolysis (IIb. B)* Key recommendations Fibrinolysis and immediate PCI is not recommended over immediate PCI alone (III [harm] B) When fibrinolysis is the planned treatment strategy, pre-hospital fibrinolysis is reasonable if transport time >30 min (IIa. B) *This is because of the small relative decrease in the incidence of intracranial haemorrhage without evidence of mortality benefit to eitherapy O’Connor RE et al. Circulation 2015; 132: S 483– 500

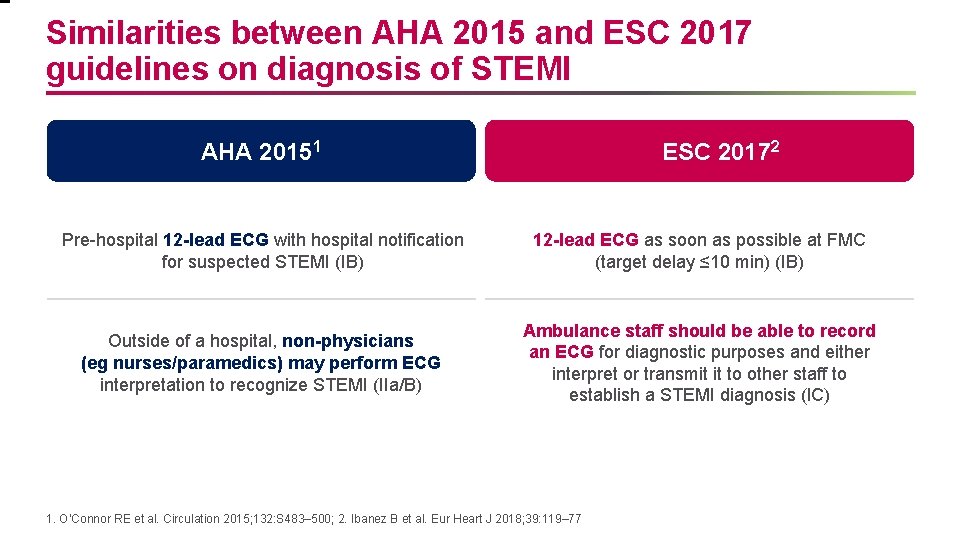

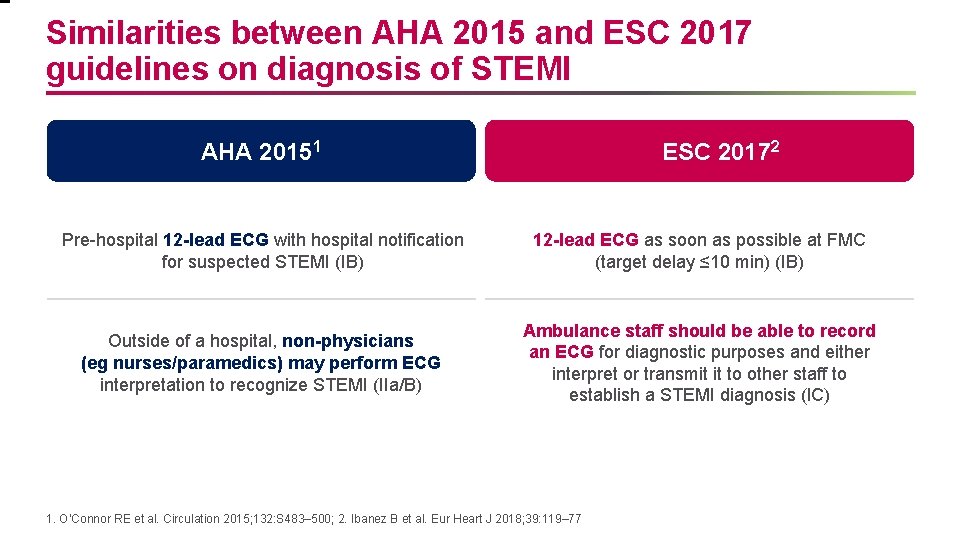

Similarities between AHA 2015 and ESC 2017 guidelines on diagnosis of STEMI AHA 20151 ESC 20172 Pre-hospital 12 -lead ECG with hospital notification for suspected STEMI (IB) 12 -lead ECG as soon as possible at FMC (target delay ≤ 10 min) (IB) Outside of a hospital, non-physicians (eg nurses/paramedics) may perform ECG interpretation to recognize STEMI (IIa/B) Ambulance staff should be able to record an ECG for diagnostic purposes and either interpret or transmit it to other staff to establish a STEMI diagnosis (IC) 1. O’Connor RE et al. Circulation 2015; 132: S 483– 500; 2. Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77

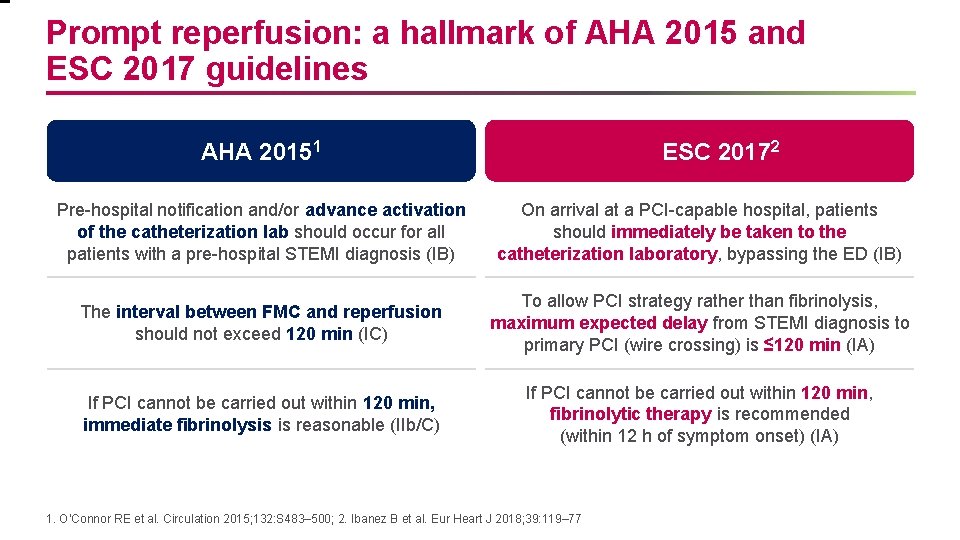

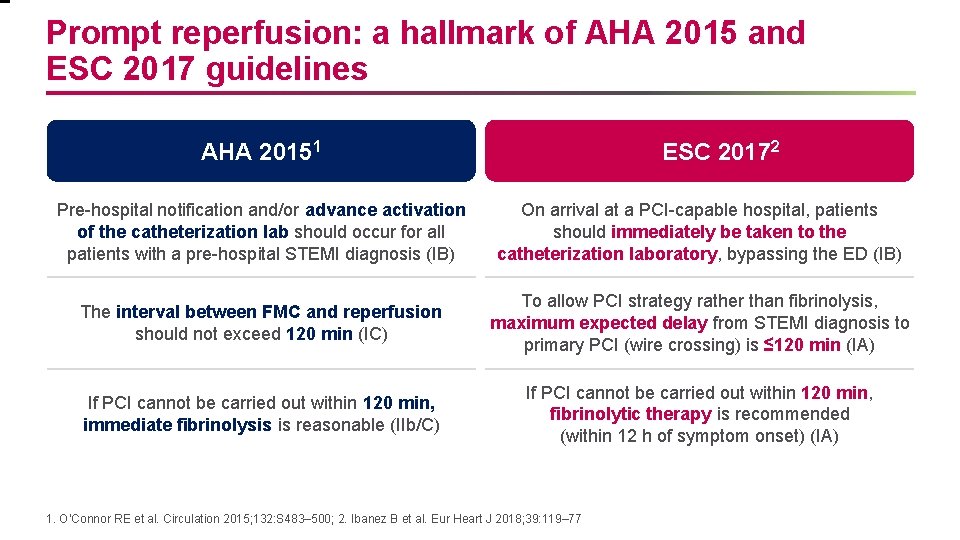

Prompt reperfusion: a hallmark of AHA 2015 and ESC 2017 guidelines AHA 20151 ESC 20172 Pre-hospital notification and/or advance activation of the catheterization lab should occur for all patients with a pre-hospital STEMI diagnosis (IB) On arrival at a PCI-capable hospital, patients should immediately be taken to the catheterization laboratory, bypassing the ED (IB) The interval between FMC and reperfusion should not exceed 120 min (IC) To allow PCI strategy rather than fibrinolysis, maximum expected delay from STEMI diagnosis to primary PCI (wire crossing) is ≤ 120 min (IA) If PCI cannot be carried out within 120 min, immediate fibrinolysis is reasonable (IIb/C) If PCI cannot be carried out within 120 min, fibrinolytic therapy is recommended (within 12 h of symptom onset) (IA) 1. O’Connor RE et al. Circulation 2015; 132: S 483– 500; 2. Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77

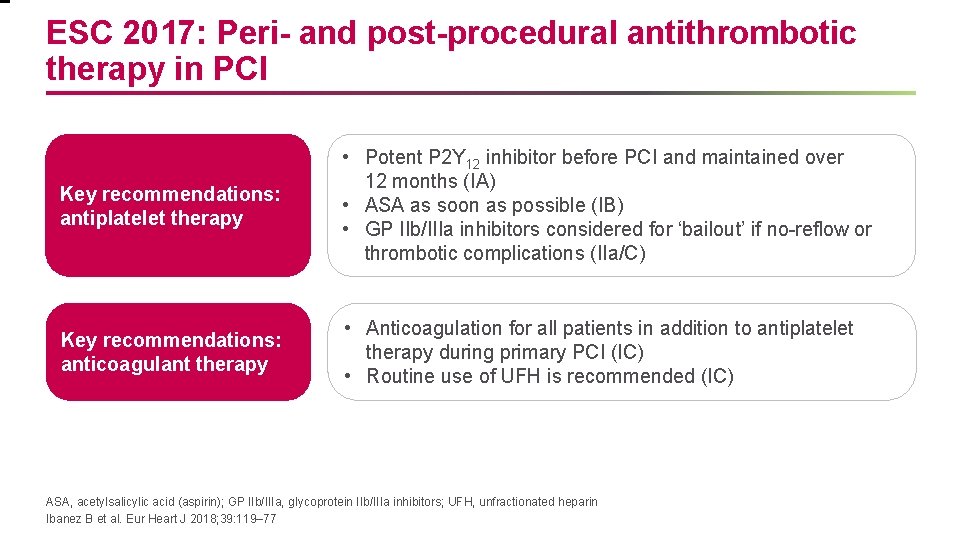

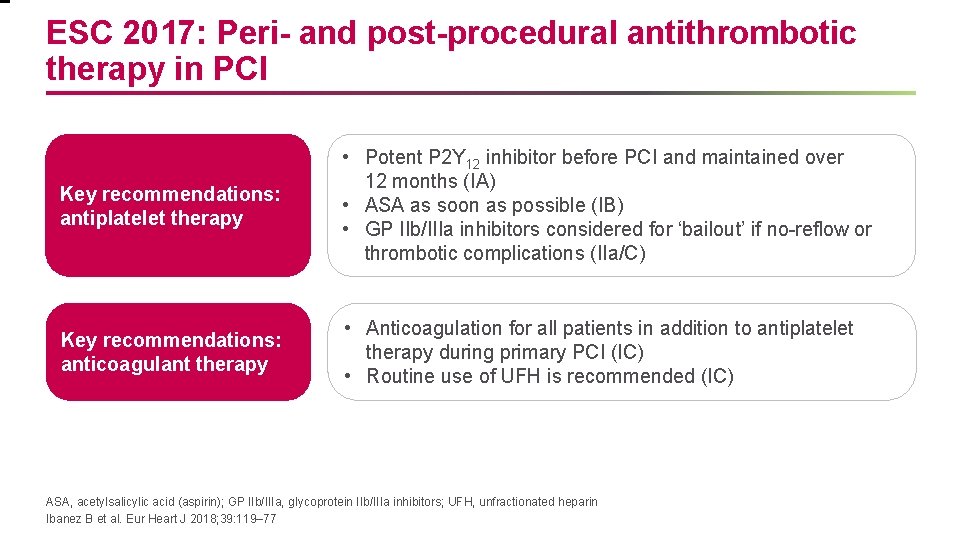

ESC 2017: Peri- and post-procedural antithrombotic therapy in PCI Key recommendations: antiplatelet therapy • Potent P 2 Y 12 inhibitor before PCI and maintained over 12 months (IA) • ASA as soon as possible (IB) • GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors considered for ‘bailout’ if no-reflow or thrombotic complications (IIa/C) Key recommendations: anticoagulant therapy • Anticoagulation for all patients in addition to antiplatelet therapy during primary PCI (IC) • Routine use of UFH is recommended (IC) ASA, acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin); GP IIb/IIIa, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors; UFH, unfractionated heparin Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77

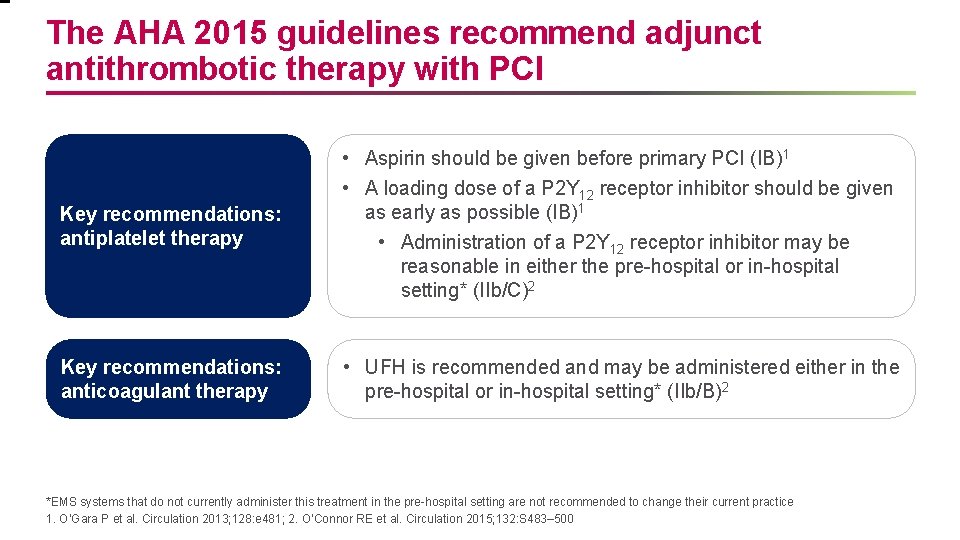

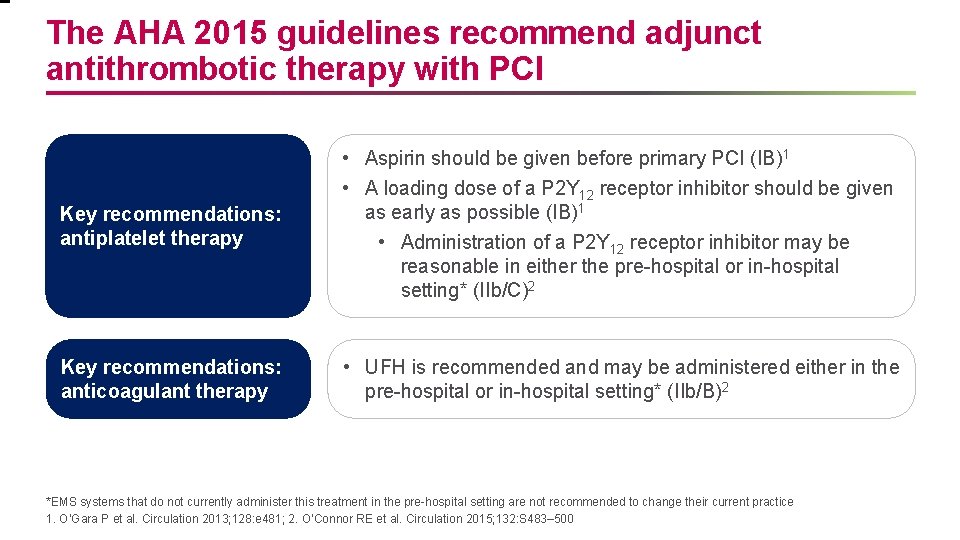

The AHA 2015 guidelines recommend adjunct antithrombotic therapy with PCI Key recommendations: antiplatelet therapy • Aspirin should be given before primary PCI (IB)1 • A loading dose of a P 2 Y 12 receptor inhibitor should be given as early as possible (IB)1 • Administration of a P 2 Y 12 receptor inhibitor may be reasonable in either the pre-hospital or in-hospital setting* (IIb/C)2 Key recommendations: anticoagulant therapy • UFH is recommended and may be administered either in the pre-hospital or in-hospital setting* (IIb/B)2 *EMS systems that do not currently administer this treatment in the pre-hospital setting are not recommended to change their current practice 1. O’Gara P et al. Circulation 2013; 128: e 481; 2. O’Connor RE et al. Circulation 2015; 132: S 483– 500

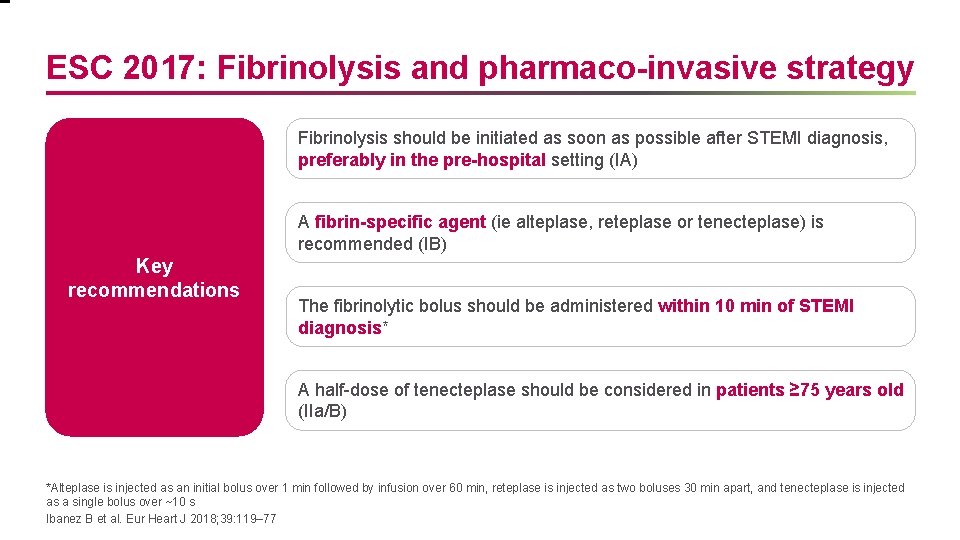

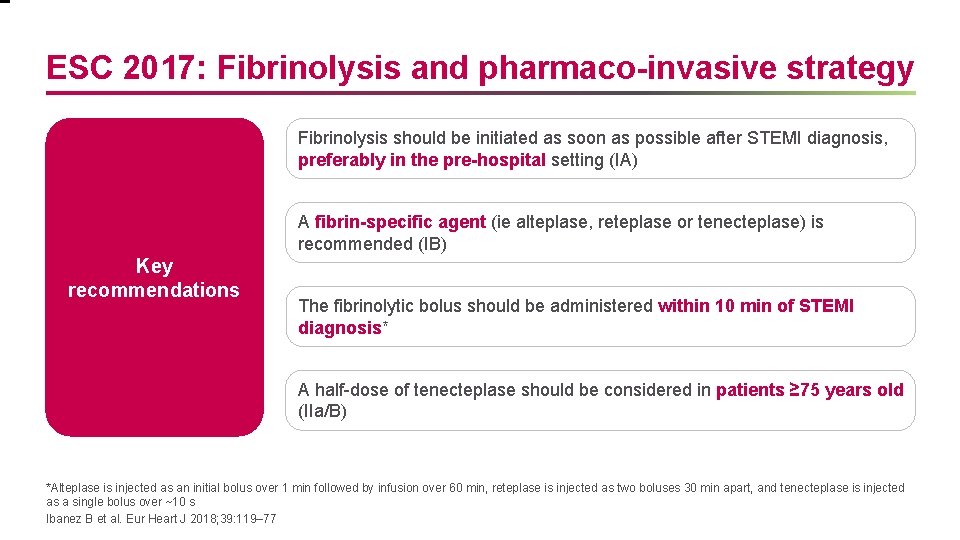

ESC 2017: Fibrinolysis and pharmaco-invasive strategy Fibrinolysis should be initiated as soon as possible after STEMI diagnosis, preferably in the pre-hospital setting (IA) A fibrin-specific agent (ie alteplase, reteplase or tenecteplase) is recommended (IB) Key recommendations The fibrinolytic bolus should be administered within 10 min of STEMI diagnosis* A half-dose of tenecteplase should be considered in patients ≥ 75 years old (IIa/B) *Alteplase is injected as an initial bolus over 1 min followed by infusion over 60 min, reteplase is injected as two boluses 30 min apart, and tenecteplase is injected as a single bolus over ~10 s Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77

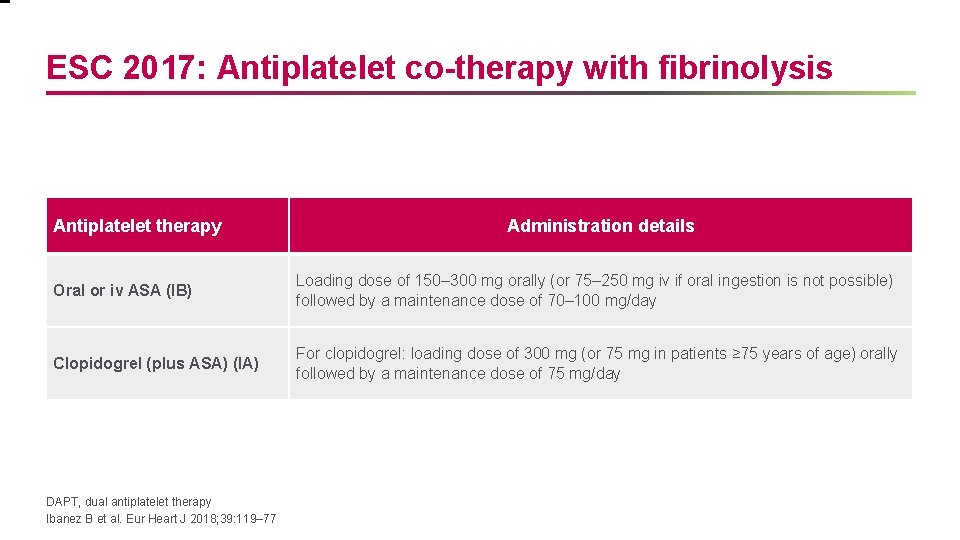

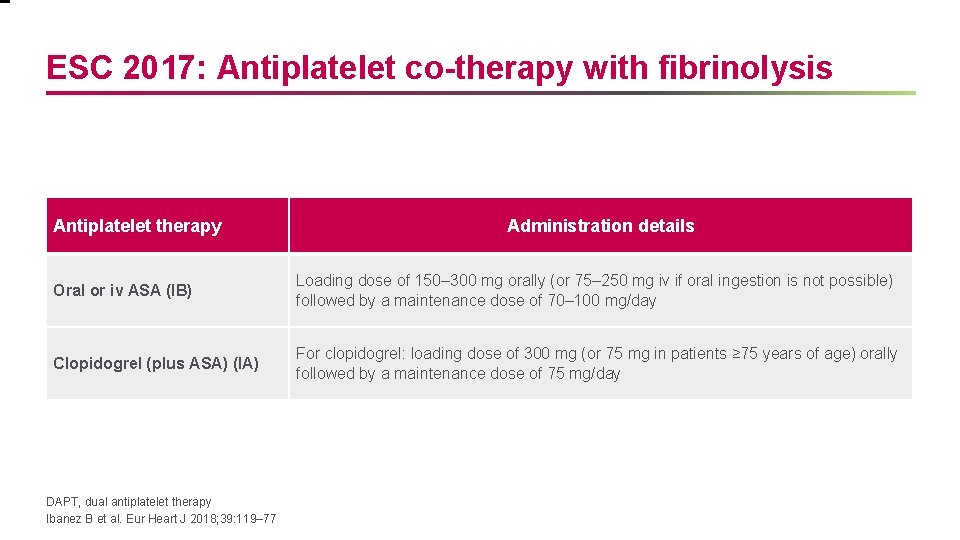

ESC 2017: Antiplatelet co-therapy with fibrinolysis Antiplatelet therapy Administration details Oral or iv ASA (IB) Loading dose of 150– 300 mg orally (or 75– 250 mg iv if oral ingestion is not possible) followed by a maintenance dose of 70– 100 mg/day Clopidogrel (plus ASA) (IA) For clopidogrel: loading dose of 300 mg (or 75 mg in patients ≥ 75 years of age) orally followed by a maintenance dose of 75 mg/day DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77

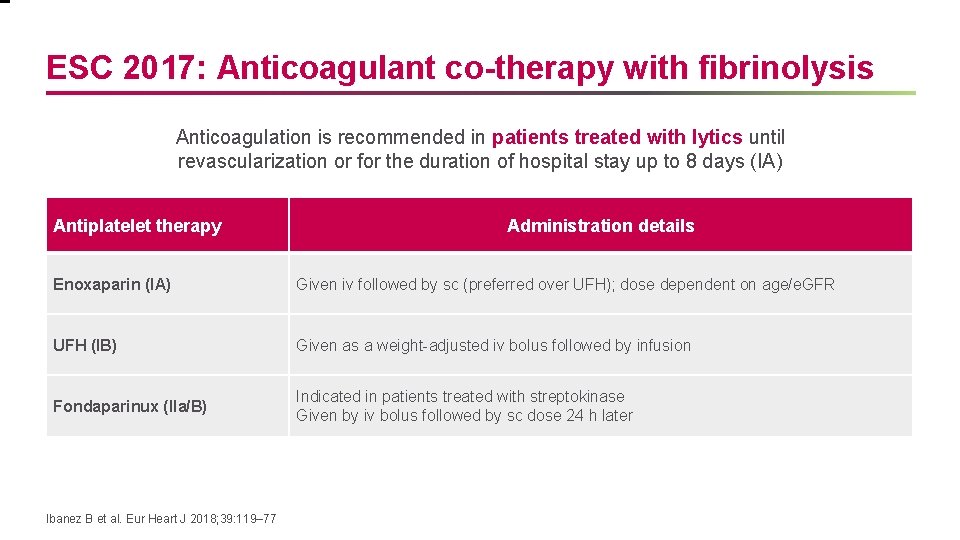

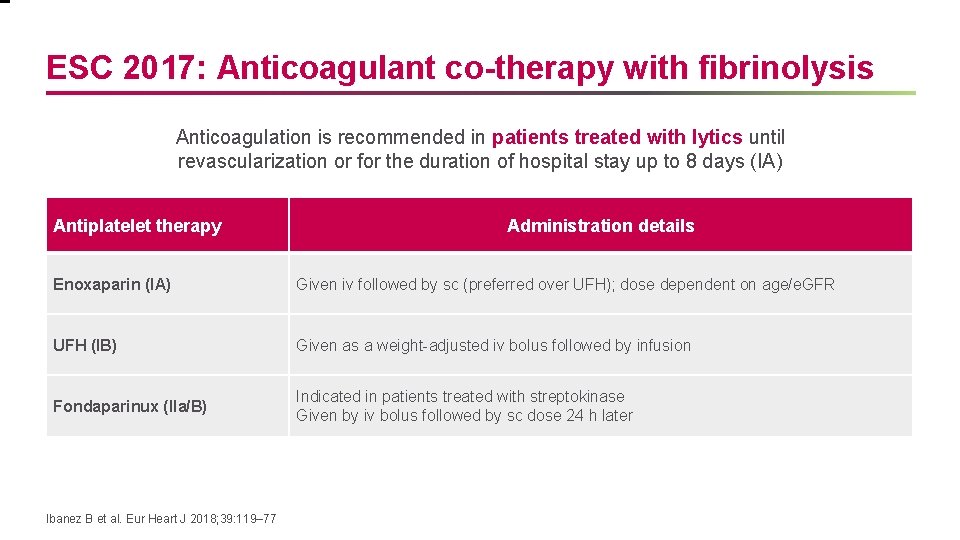

ESC 2017: Anticoagulant co-therapy with fibrinolysis Anticoagulation is recommended in patients treated with lytics until revascularization or for the duration of hospital stay up to 8 days (IA) Antiplatelet therapy Administration details Enoxaparin (IA) Given iv followed by sc (preferred over UFH); dose dependent on age/e. GFR UFH (IB) Given as a weight-adjusted iv bolus followed by infusion Fondaparinux (IIa/B) Indicated in patients treated with streptokinase Given by iv bolus followed by sc dose 24 h later Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77

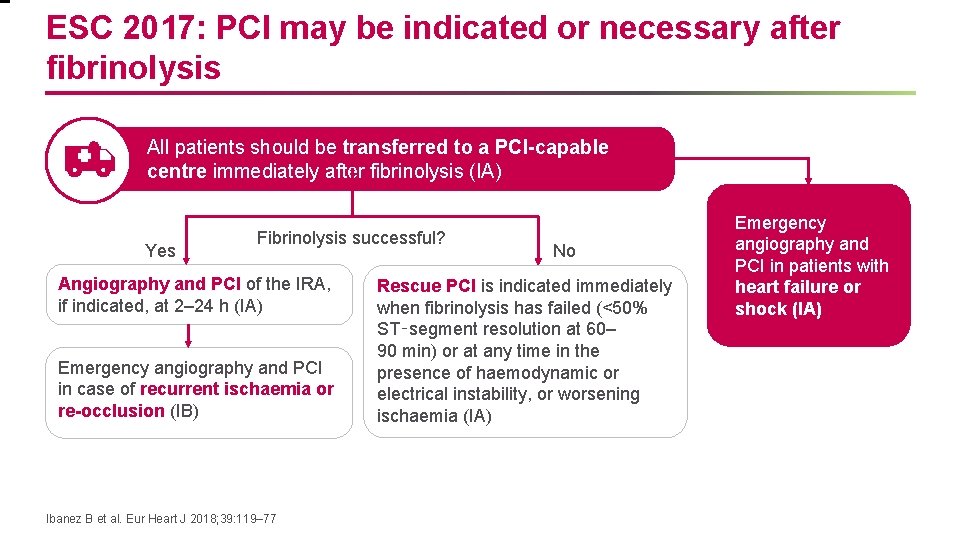

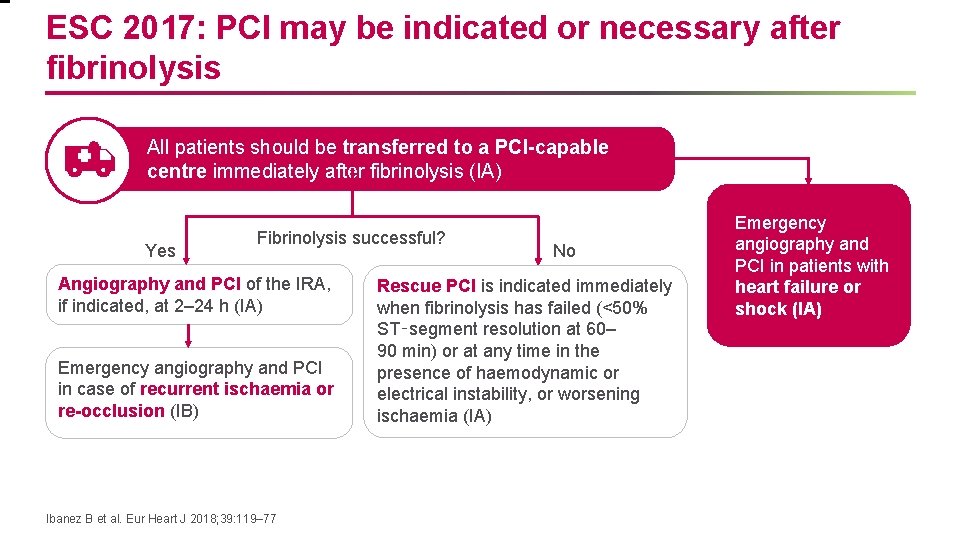

ESC 2017: PCI may be indicated or necessary after fibrinolysis All patients should be transferred to a PCI-capable centre immediately after fibrinolysis (IA) Yes Fibrinolysis successful? Angiography and PCI of the IRA, if indicated, at 2– 24 h (IA) Emergency angiography and PCI in case of recurrent ischaemia or re-occlusion (IB) Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77 No Rescue PCI is indicated immediately when fibrinolysis has failed (<50% ST‑segment resolution at 60– 90 min) or at any time in the presence of haemodynamic or electrical instability, or worsening ischaemia (IA) Emergency angiography and PCI in patients with heart failure or shock (IA)

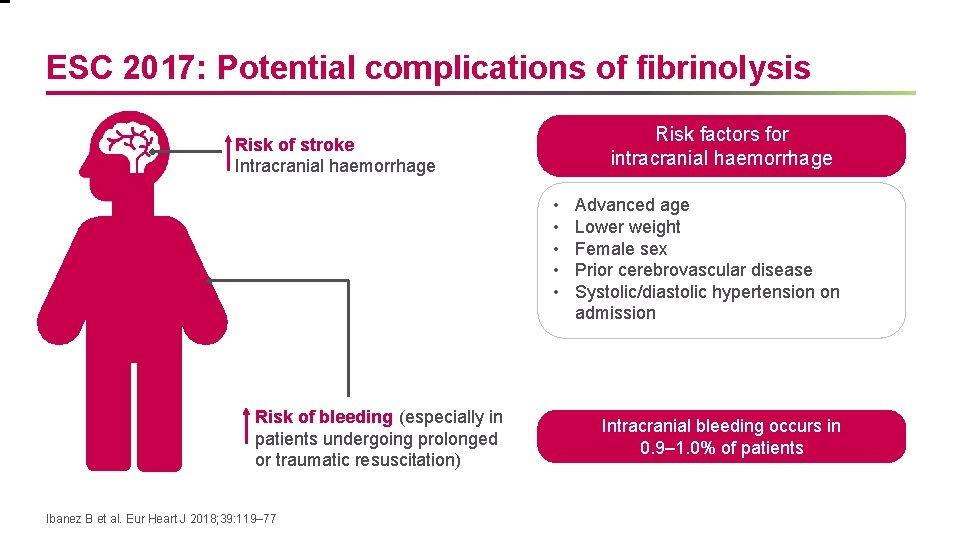

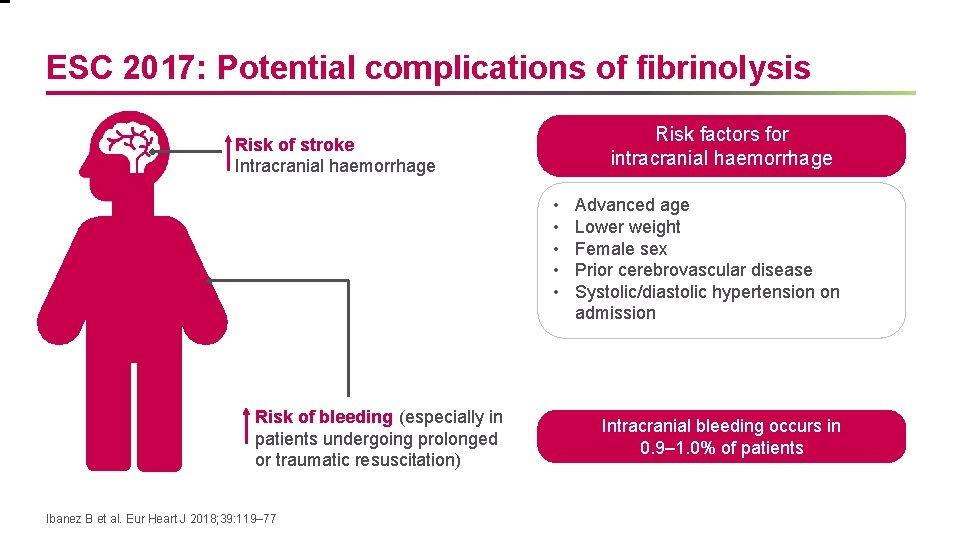

ESC 2017: Potential complications of fibrinolysis Risk factors for intracranial haemorrhage Risk of stroke Intracranial haemorrhage • • • Risk of bleeding (especially in patients undergoing prolonged or traumatic resuscitation) Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77 Advanced age Lower weight Female sex Prior cerebrovascular disease Systolic/diastolic hypertension on admission Intracranial bleeding occurs in 0. 9– 1. 0% of patients

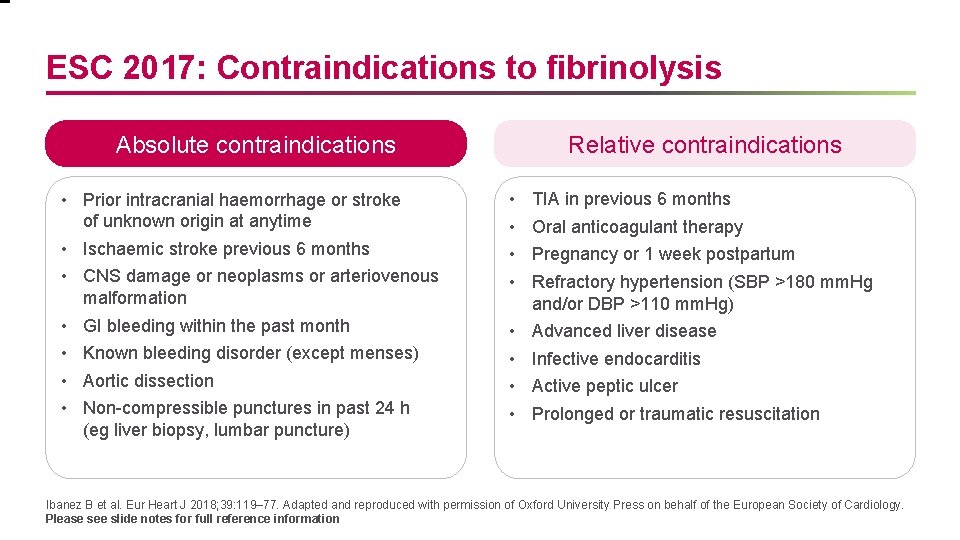

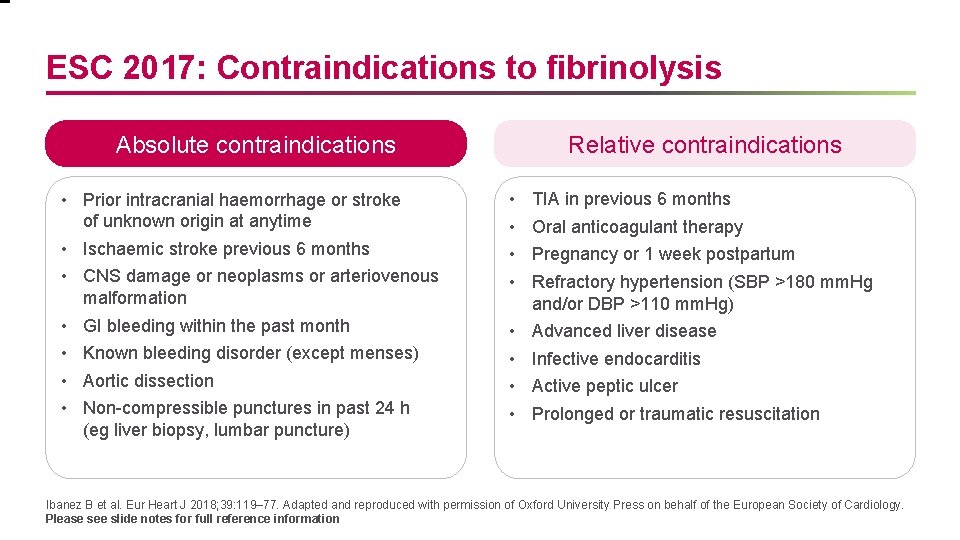

ESC 2017: Contraindications to fibrinolysis Absolute contraindications • Prior intracranial haemorrhage or stroke of unknown origin at anytime • Ischaemic stroke previous 6 months • CNS damage or neoplasms or arteriovenous malformation • GI bleeding within the past month • Known bleeding disorder (except menses) • Aortic dissection • Non-compressible punctures in past 24 h (eg liver biopsy, lumbar puncture) Relative contraindications • • TIA in previous 6 months • • Advanced liver disease Oral anticoagulant therapy Pregnancy or 1 week postpartum Refractory hypertension (SBP >180 mm. Hg and/or DBP >110 mm. Hg) Infective endocarditis Active peptic ulcer Prolonged or traumatic resuscitation Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77. Adapted and reproduced with permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology. Please see slide notes for full reference information

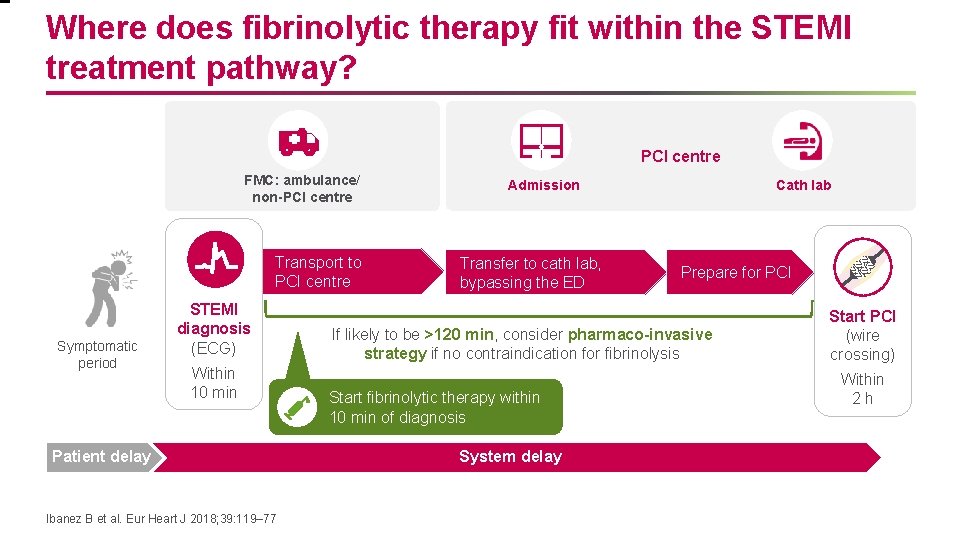

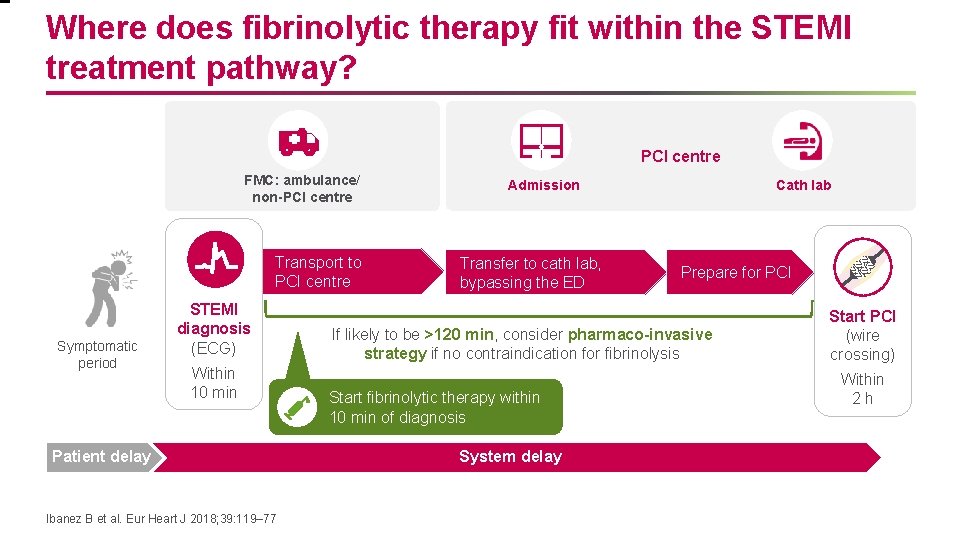

Where does fibrinolytic therapy fit within the STEMI treatment pathway? PCI centre FMC: ambulance/ non-PCI centre Transport to PCI centre Symptomatic period STEMI diagnosis (ECG) Within 10 min Patient delay Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77 Admission Transfer to cath lab, bypassing the ED Cath lab Prepare for PCI If likely to be >120 min, consider pharmaco-invasive strategy if no contraindication for fibrinolysis Start fibrinolytic therapy within 10 min of diagnosis System delay Start PCI (wire crossing) Within 2 h

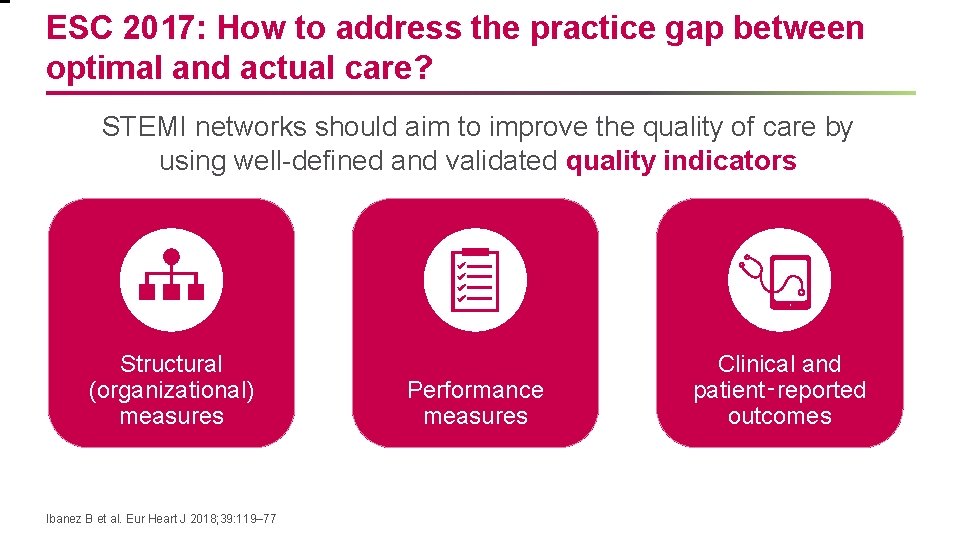

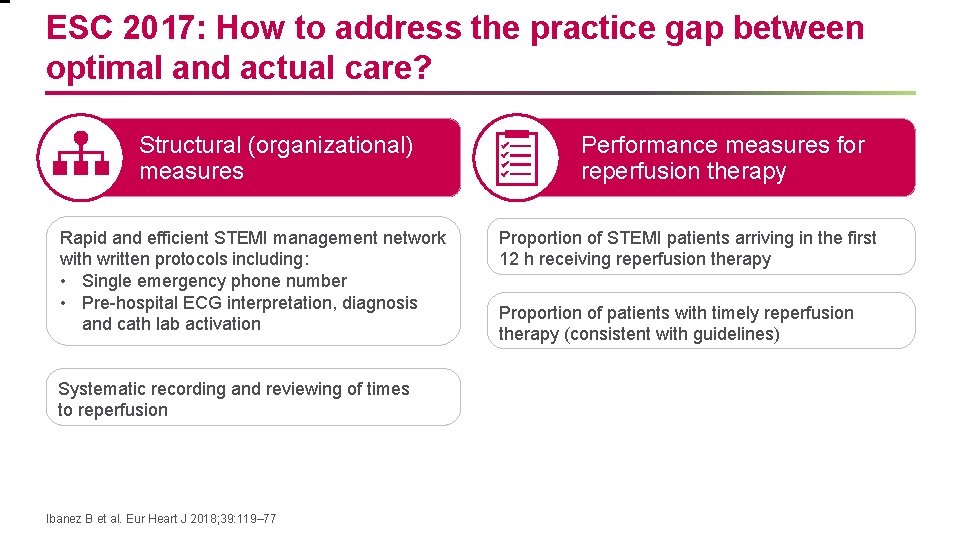

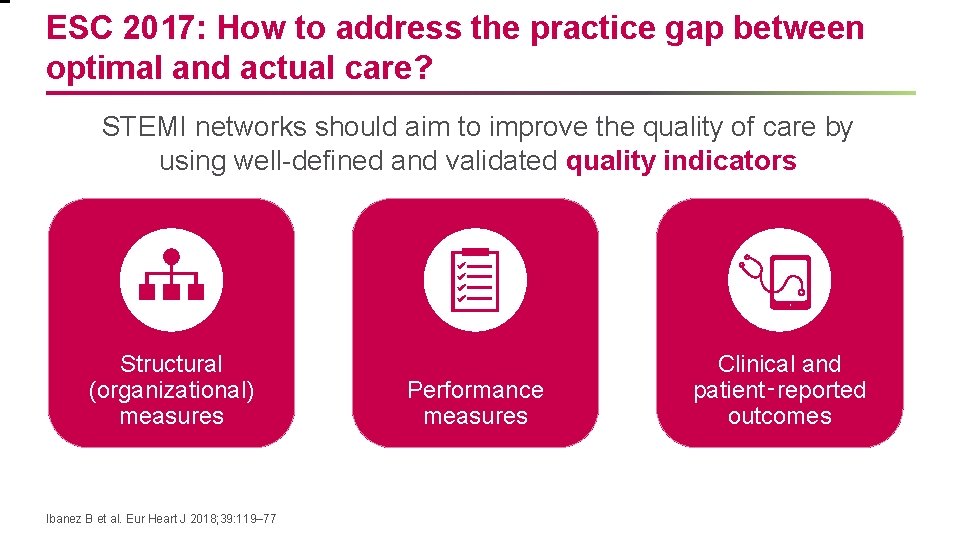

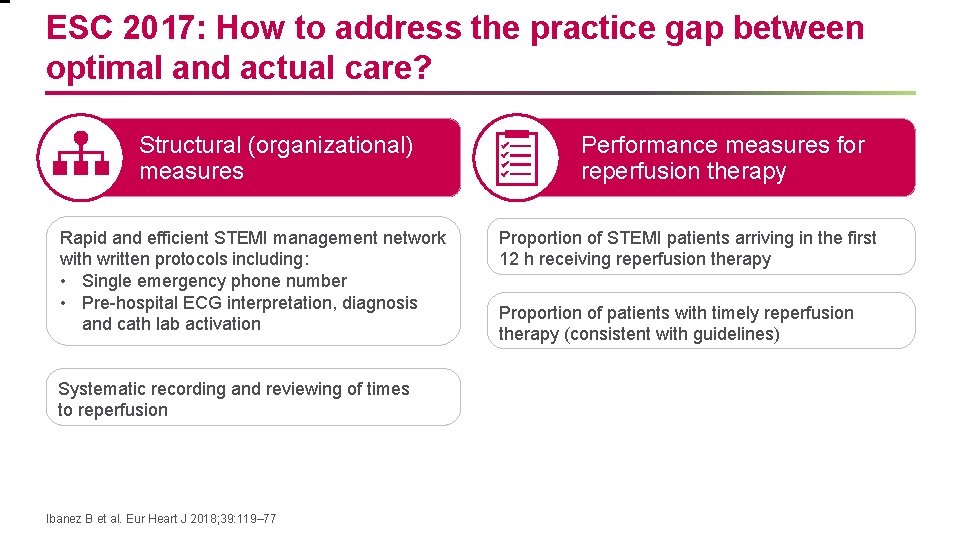

ESC 2017: How to address the practice gap between optimal and actual care? STEMI networks should aim to improve the quality of care by using well-defined and validated quality indicators Structural (organizational) measures Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77 Performance measures Clinical and patient‑reported outcomes

ESC 2017: How to address the practice gap between optimal and actual care? Structural (organizational) measures Rapid and efficient STEMI management network with written protocols including: • Single emergency phone number • Pre-hospital ECG interpretation, diagnosis and cath lab activation Systematic recording and reviewing of times to reperfusion Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77 Performance measures for reperfusion therapy Proportion of STEMI patients arriving in the first 12 h receiving reperfusion therapy Proportion of patients with timely reperfusion therapy (consistent with guidelines)

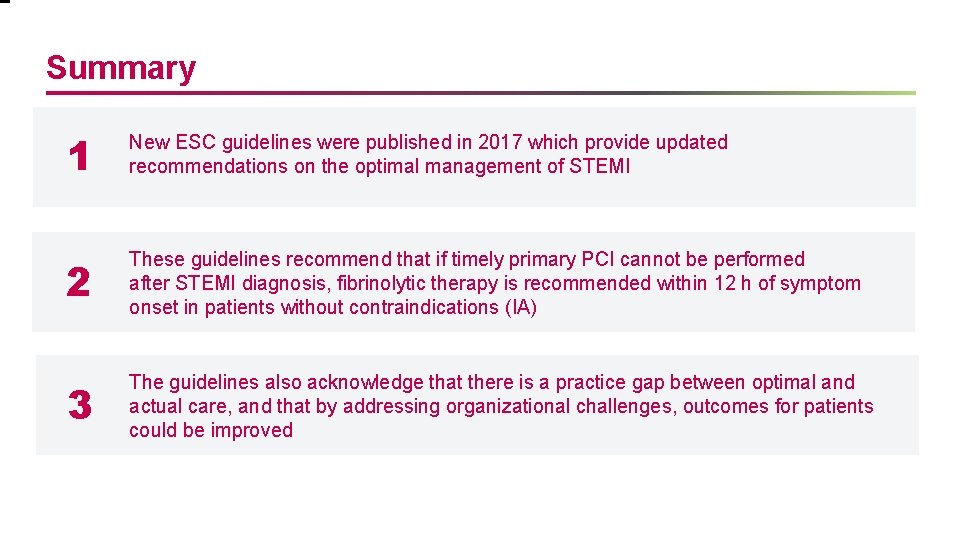

Summary 1 New ESC guidelines were published in 2017 which provide updated recommendations on the optimal management of STEMI 2 These guidelines recommend that if timely primary PCI cannot be performed after STEMI diagnosis, fibrinolytic therapy is recommended within 12 h of symptom onset in patients without contraindications (IA) 3 The guidelines also acknowledge that there is a practice gap between optimal and actual care, and that by addressing organizational challenges, outcomes for patients could be improved

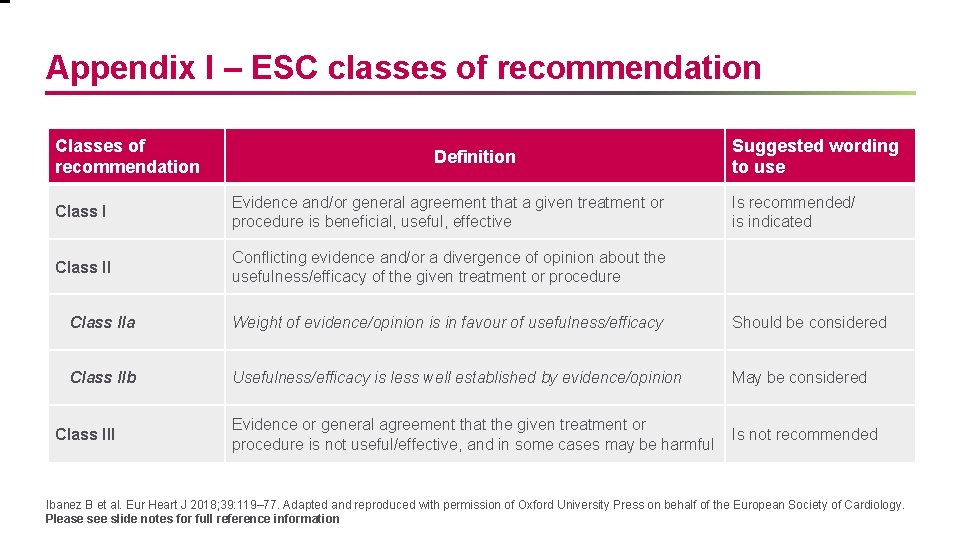

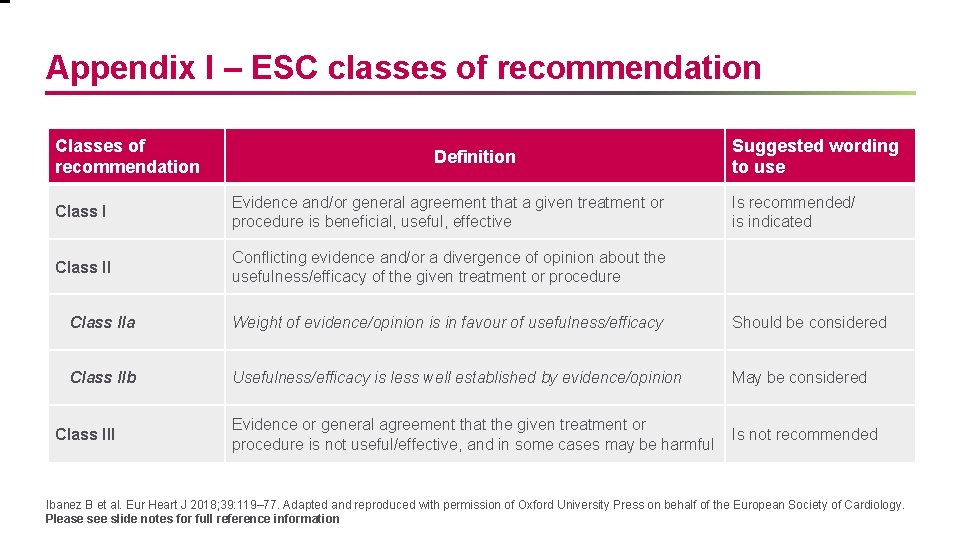

Appendix I – ESC classes of recommendation Classes of recommendation Definition Class I Evidence and/or general agreement that a given treatment or procedure is beneficial, useful, effective Class II Conflicting evidence and/or a divergence of opinion about the usefulness/efficacy of the given treatment or procedure Suggested wording to use Is recommended/ is indicated Class IIa Weight of evidence/opinion is in favour of usefulness/efficacy Should be considered Class IIb Usefulness/efficacy is less well established by evidence/opinion May be considered Evidence or general agreement that the given treatment or procedure is not useful/effective, and in some cases may be harmful Is not recommended Class III Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77. Adapted and reproduced with permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology. Please see slide notes for full reference information

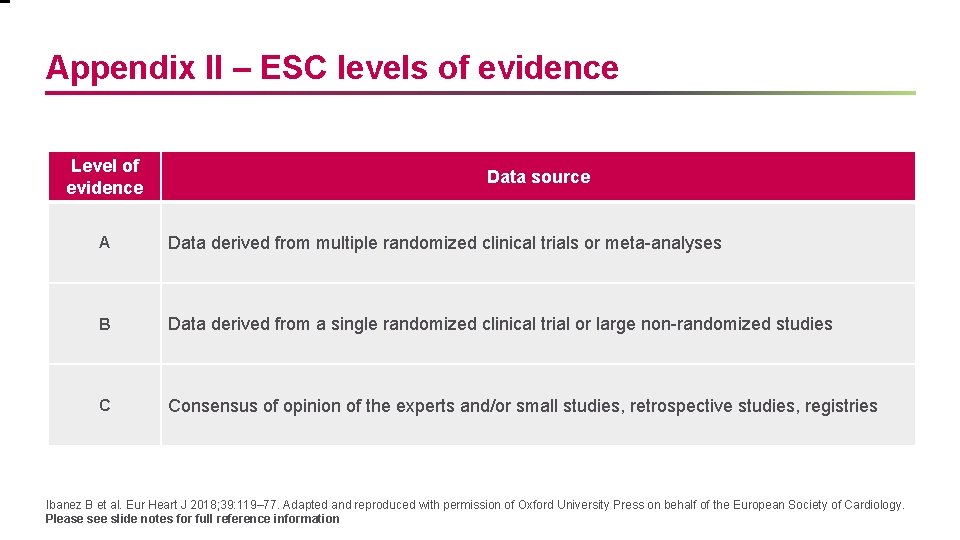

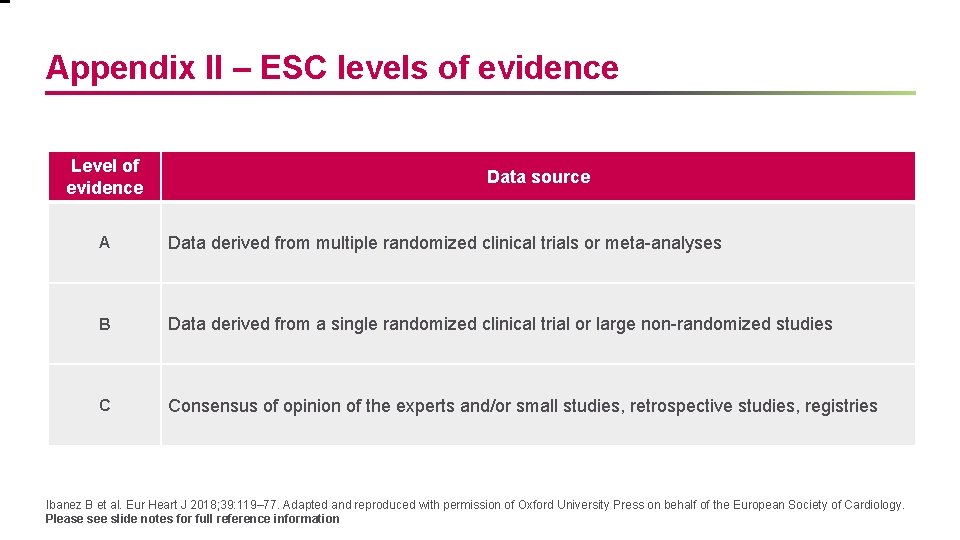

Appendix II – ESC levels of evidence Level of evidence Data source A Data derived from multiple randomized clinical trials or meta-analyses B Data derived from a single randomized clinical trial or large non-randomized studies C Consensus of opinion of the experts and/or small studies, retrospective studies, registries Ibanez B et al. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119– 77. Adapted and reproduced with permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology. Please see slide notes for full reference information