Management of neonatal vomiting abdominal distention Vomiting relatively

Management of neonatal vomiting , abdominal distention

Vomiting relatively frequent symptom during the neonatal period. In the 1 st few hours after birth, infants may vomit mucus, occasionally blood streaked. This vomiting rarely persists after the 1 st few feedings; it may be due to irritation of the gastric mucosa by material swallowed during delivery. If vomiting is protracted, gastric lavage with physiologic saline solution may relieve it. When persistent : possibilities of intestinal obstruction metabolic disorders increased intracranial pressure must be considered.

A history of maternal polyhydramnios suggests upper gastrointestinal (esophageal, duodenal, ileal) atresia. Bile-stained emesis suggests intestinal obstruction beyond the duodenum but may also be idiopathic. Abdominal radiographs (kidney-ureter-bladder [KUB] and cross-table lateral views) should be performed in neonates with persistent emesis and in all infants with bile-stained emesis to detect air-fluid levels, distended bowel loops, characteristic patterns of obstruction (double bubble: duodenal atresia), and pneumoperitoneum (intestinal perforation). A contrast swallow roentgenogram with small bowel followthrough is indicated in the presence of bilious emesis. Obstructive lesions of the digestive tract are the most frequent gastrointestinal anomalies

Vomiting (and drooling) from esophageal obstruction occurs with the 1 st feeding. The diagnosis of esophageal atresia can be suspected if unusual drooling from the mouth is observed and if resistance is encountered during an attempt to pass a catheter into the stomach. The diagnosis should be made before the infant has trouble with oral feedings and aspiration pneumonia develops Infantile achalasia (cardiospasm), a rare cause of vomiting in newborn infants, is demonstrable radiographically as obstruction at the cardiac end of the esophagus without organic stenosis.

Regurgitation of feedings because of continuous relaxation of the esophageal-gastric sphincter, or chalasia, is a cause of vomiting. Keeping the infant in a semi-upright position, thickening the feeding, or administering prokinetic drugs can control it Vomiting due to obstruction of the small intestine usually begins on the 1 st day of life and is frequent, persistent, usually nonprojectile, copious, and, unless the obstruction is above the ampulla of Vater, bile-stained it is associated with abdominal distention, visible deep peristaltic waves, and reduction or absence of bowel movements.

Malrotation with obstruction from midgut volvulus is an acute emergency that must be not only considered but also urgently evaluated by an upper gastrointestinal contrast radiographic series. Radiographs of the abdomen show the distribution of air in the intestine, which may point to the anatomic location of an obstruction; malrotation can be identified only by contrast studies. Normally, air can be demonstrated by radiographs in the jejunum by 15 -60 min, in the ileum by 2 -3 hr, and in the colon by 3 hr after birth. Absence of rectal gas at 24 hr is abnormal.

Persistent vomiting may occur with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. -losing variety The vomiting associated with pyloric stenosis may begin any time after birth but does not assume its characteristic pattern before the 2 nd-3 rd wk. hyperammonemias Vomiting with obstipation is a common early sign of Hirschsprung disease. septicemia, meningitis, and urinary tract infection. Vomiting may occur with many other disturbances such as: In many infants, it is simply regurgitation from overfeeding or from failure to permit the infant to eructate swallowed air. milk allergy adrenal hyperplasia of the salt galactosemia organic acidemias increased intracranial pressure

Constipation More than 90% of full-term newborn infants pass meconium within the 1 st 24 hr The possibility of intestinal obstruction should be considered in any infant who does not pass meconium by 24 -36 hr. Intestinal atresia, stricture, or stenosis; Hirschsprung disease; milk bolus obstruction; meconium ileus; or meconium plugs may manifest as constipation or, more often, obstipation. About 20% of very low birthweight (VLBW) infants do not pass meconium within the 1 st 24 hr.

Constipation not present from birth but appearing during the 1 st mo of life may be a sign of short-segment congenital aganglionic megacolon, hypothyroidism strictures after necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) anal stenosis. It must be kept in mind that infrequent bowel movements do not necessarily mean constipation. A breast-fed infant usually has frequent bowel movements, whereas a formula-fed infant may have 1 -2 movements a day or every other day.

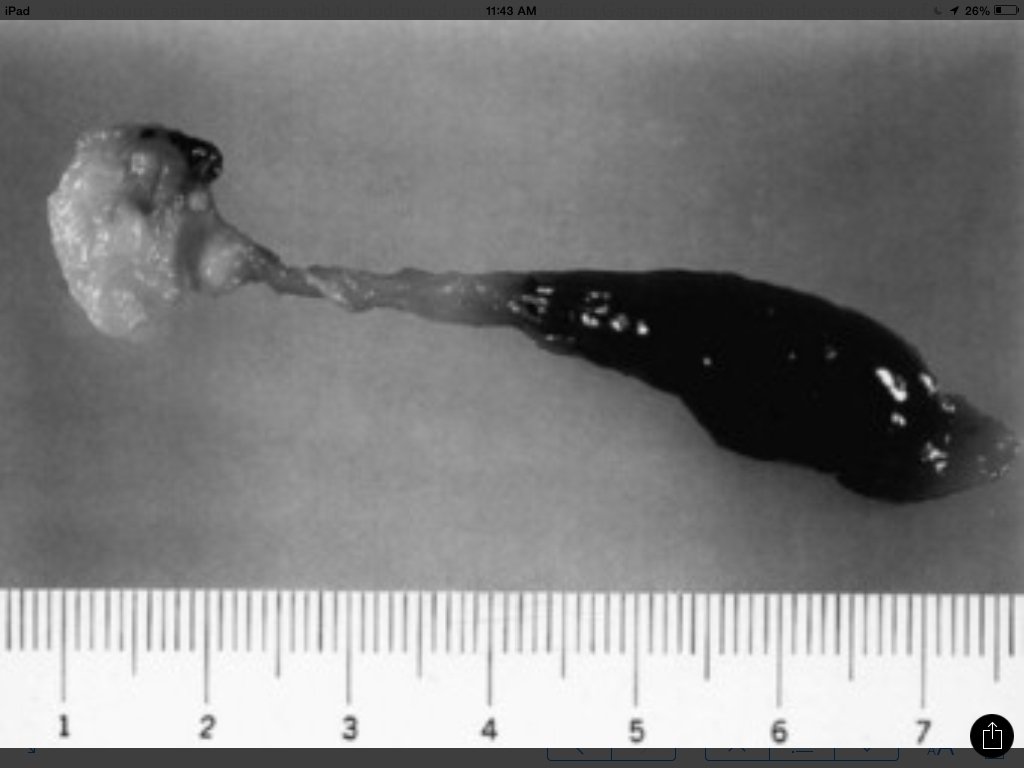

Meconium plugs Lower colonic or anorectal plugs with a lower than normal water content may cause intestinal obstruction Rarely, a firm mass of meconium may cause intrauterine intestinal obstruction and meconium peritonitis unrelated to cystic fibrosis (CF). Anorectal plugs may also cause mucosal ulceration and intestinal perforation. Meconium plugs are associated with small left colon syndrome in infants of diabetic mothers CF rectal aganglionosis maternal opiate use magnesium sulfate therapy for preeclampsia.

The plug may be evacuated by glycerin suppository rectal irrigation with isotonic saline. Enemas with the iodinated contrast medium Gastrografin usually induce passage of the plug, presumably because the high osmolarity (1, 900 m. Osm/L) of the solution draws fluid rapidly into the intestinal lumen and loosens inspissated material. Such rapid loss of fluid into the bowel may result in acute dehydration and shock, so it is advisable to dilute the contrast material with an equal amount of water, correct any existing dehydration, and provide intravenous fluids during and for several hours after the procedure. After removal of a meconium plug, the infant should be observed closely for the possible presence of congenital aganglionic megacolon.

Meconium ileus in cystic fibrosis The absence of fetal pancreatic enzymes in CF limits normal digestive activities in the intestine, and meconium becomes viscid and mucilaginous. The inspissated and impacted meconium fills the intestinal canal but is most concentrated in the lower part of the ileum. Clinically, the pattern is that of congenital intestinal obstruction with or without intestinal perforation. Abdominal distention is prominent, and vomiting becomes persistent. Infrequently, one or more inspissated meconium stools may be passed shortly after birth.

The differential diagnosis involves other causes of intestinal obstruction, including intestinal pseudo-obstruction and other causes of pancreatic insufficiency A presumptive diagnosis can be made on the basis of a history of CF in a sibling, via palpation of doughy or cordlike masses of intestines through the abdominal wall, and from the radiographic appearance. In contrast to the generally evenly distended intestinal loops above an atresia, the loops may vary in width and are not as evenly filled with gas. At points of heaviest meconium concentration, the infiltrated gas may create a bubbly granular appearance It is technically difficult to perform a sweat test in a neonate. Genetic testing confirms the diagnosis of CF.

Treatment high Gastrografin enema as described previously for meconium plugs. If the procedure unsuccessful or perforation of the bowel wall is suspected, laparotomy is performed, and the ileum opened at the point of greatest diameter of the impaction. Approximately 50% of these infants have associated intestinal atresia, stenosis, or volvulus that requires surgery. The inspissated meconium is removed by gentle and patient irrigation with warm isotonic sodium chloride or acetylcysteine (Mucomyst) solution through a catheter passed between the impaction and the bowel wall. Most infants with meconium ileus survive the neonatal period. If meconium ileus is associated with CF, the long-term prognosis depends on the severity of the underlying disease

Meconium peritonitis Perforation of the intestine may occur in utero or shortly after birth. Frequently, the intestinal perforation seals naturally with relatively little meconium leakage into the peritoneal cavity. In some cases, with long-standing perforation, meconium peritonitis is more pronounced. Perforations occur most often as a complication of meconium ileus in infants with CF but are occasionally due to a meconium plug or in utero intestinal obstruction of another cause. Cases at the most severe end of the spectrum may be diagnosed on prenatal ultrasonography with fetal ascites polyhydramnios bowel dilatation intra-abdominal calcifications hydrops fetalis.

At the other end are cases in which an intestinal perforation may seal spontaneously with only a minor meconium leak, so the event may never be detected except when meconium becomes calcified and is later discovered on radiographs of the abdomen. Alternatively, the clinical picture may be dominated by the signs of intestinal obstruction (as in meconium ileus) or chemical peritonitis. Characteristic clinical findings include abdominal distention, vomiting, and absence of stools. Treatment consists primarily of elimination of the intestinal obstruction and drainage of the peritoneal cavity.

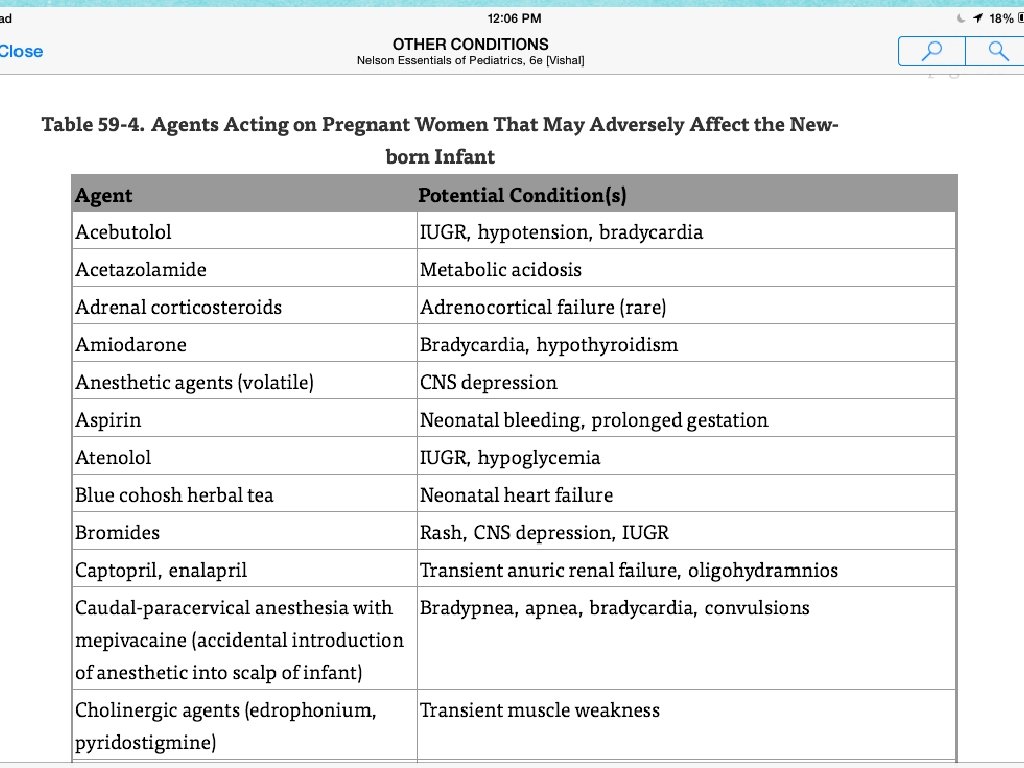

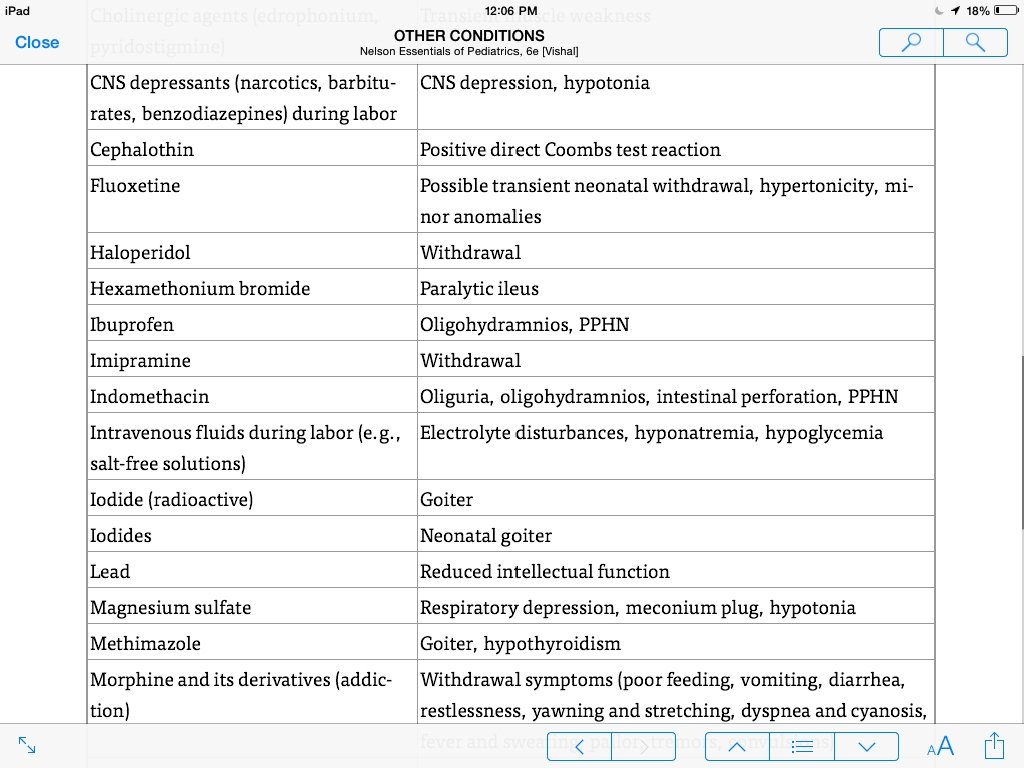

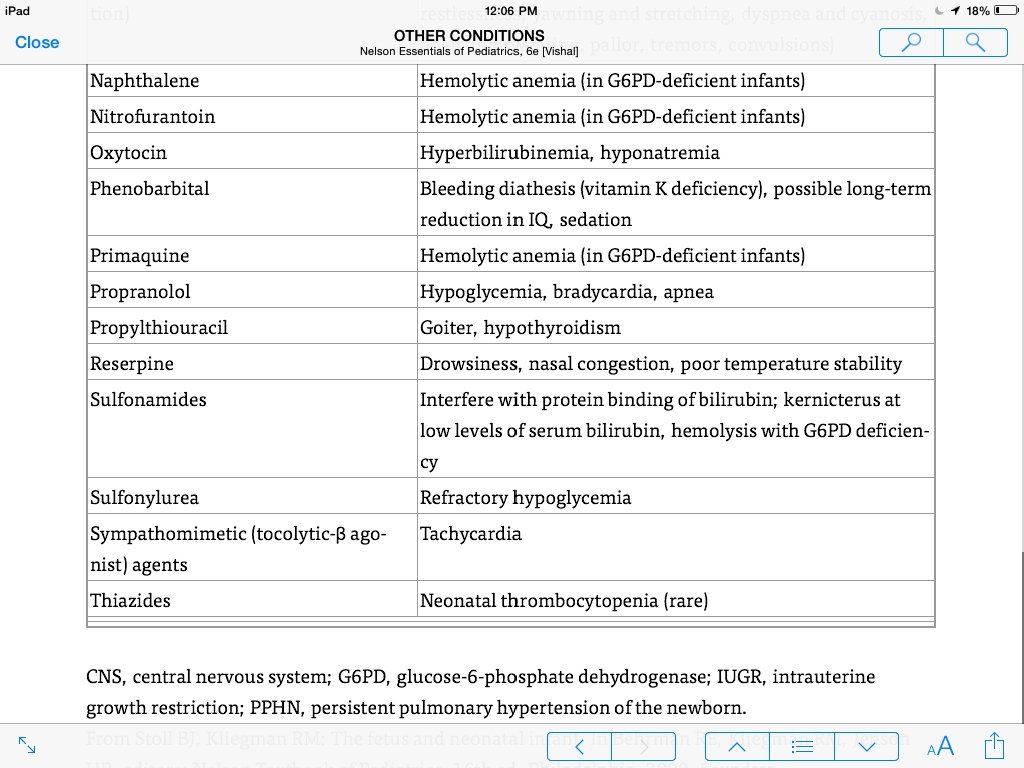

Agents Acting on Pregnant Women That May Adversely Affect the Newborn Infant

- Slides: 23