Main Menu A Power Point Show file pps

- Slides: 62

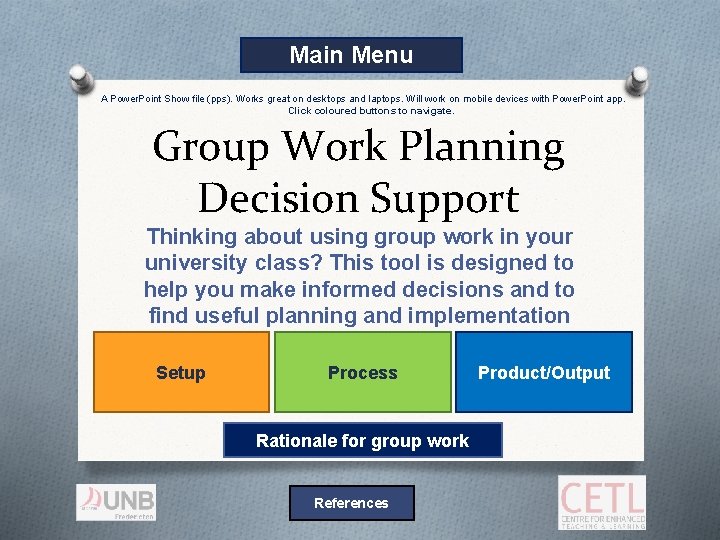

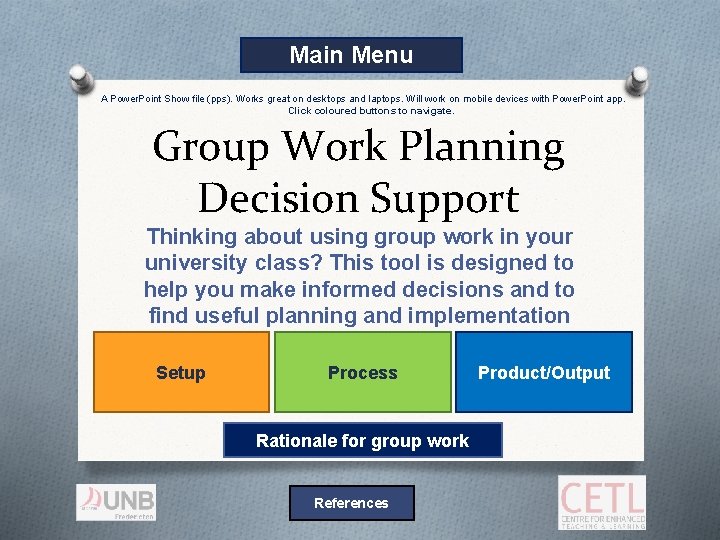

Main Menu A Power. Point Show file (pps). Works great on desktops and laptops. Will work on mobile devices with Power. Point app. Click coloured buttons to navigate. Group Work Planning Decision Support Thinking about using group work in your university class? This tool is designed to help you make informed decisions and to find useful planning and implementation resources. Setup Process Rationale for group work References Product/Output

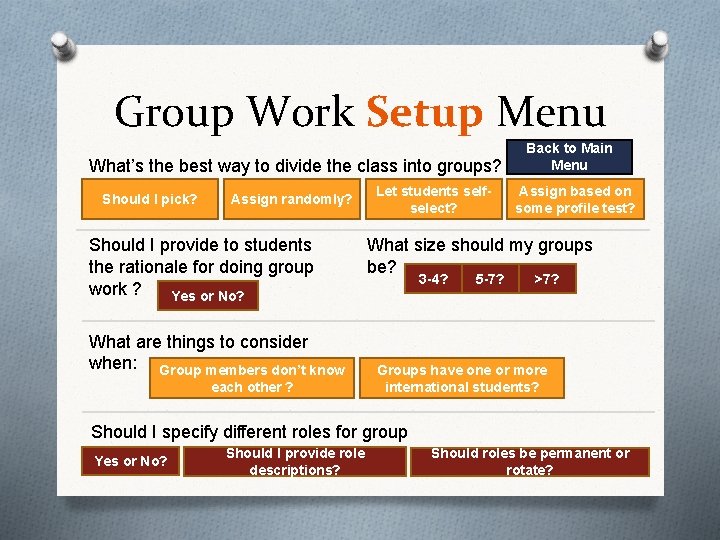

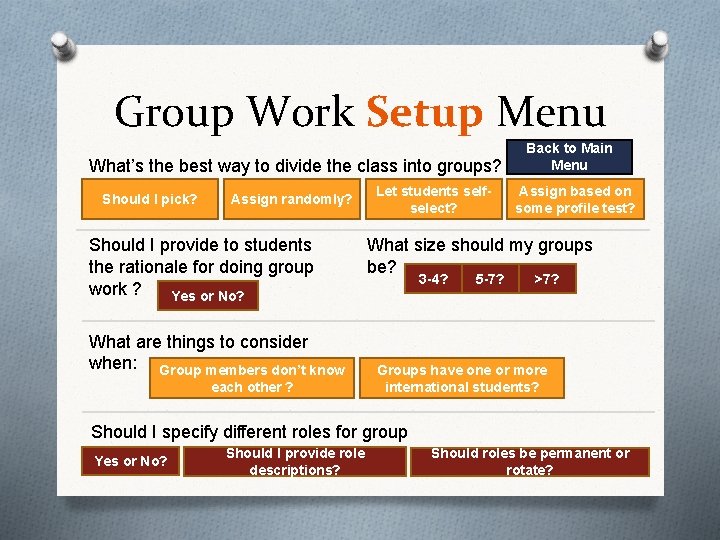

Group Work Setup Menu What’s the best way to divide the class into groups? Should I pick? Assign randomly? Should I provide to students the rationale for doing group work ? Yes or No? What are things to consider when: Group members don’t know each other ? Let students selfselect? Assign based on some profile test? What size should my groups be? 3 -4? 5 -7? >7? Groups have one or more international students? Should I specify different roles for group Should I provide role members? Yes or No? descriptions? Back to Main Menu Should roles be permanent or rotate?

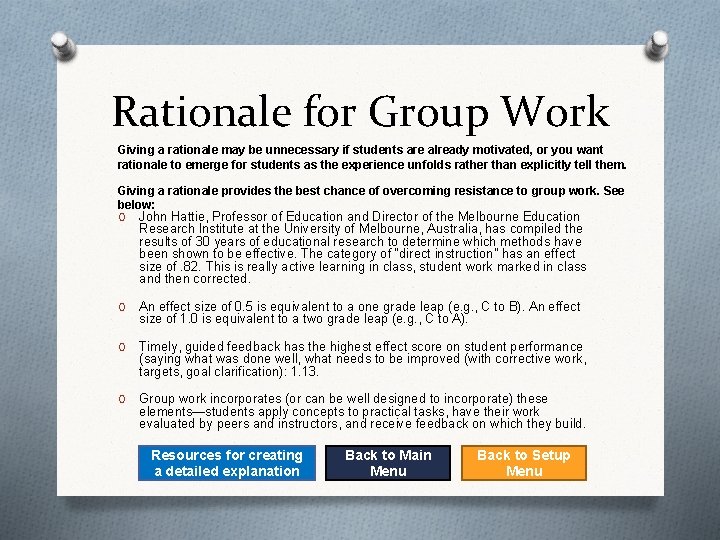

Rationale for Group Work Giving a rationale may be unnecessary if students are already motivated, or you want rationale to emerge for students as the experience unfolds rather than explicitly tell them. Giving a rationale provides the best chance of overcoming resistance to group work. See below: O John Hattie, Professor of Education and Director of the Melbourne Education Research Institute at the University of Melbourne, Australia, has compiled the results of 30 years of educational research to determine which methods have been shown to be effective. The category of “direct instruction” has an effect size of. 82. This is really active learning in class, student work marked in class and then corrected. O An effect size of 0. 5 is equivalent to a one grade leap (e. g. , C to B). An effect size of 1. 0 is equivalent to a two grade leap (e. g. , C to A). O Timely, guided feedback has the highest effect score on student performance (saying what was done well, what needs to be improved (with corrective work, targets, goal clarification): 1. 13. O Group work incorporates (or can be well designed to incorporate) these elements—students apply concepts to practical tasks, have their work evaluated by peers and instructors, and receive feedback on which they build. Resources for creating a detailed explanation Back to Main Menu Back to Setup Menu

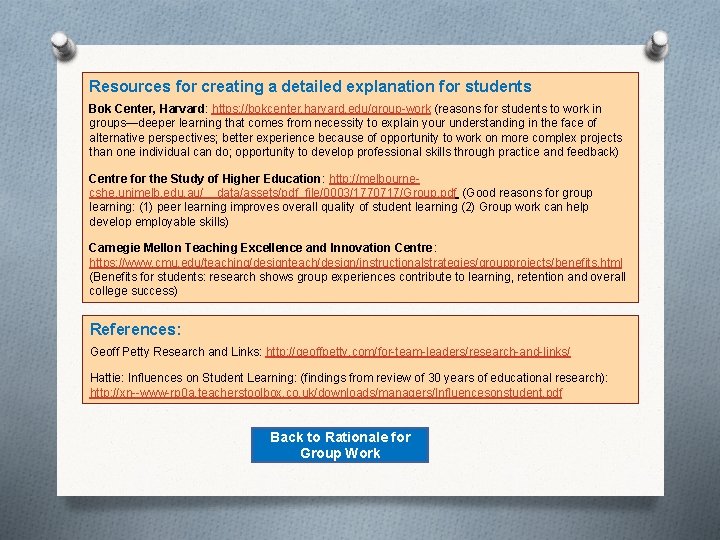

Resources for creating a detailed explanation for students Resources for Explanation Bok Center, Harvard: https: //bokcenter. harvard. edu/group-work (reasons for students to work in groups—deeper learning that comes from necessity to explain your understanding in the face of alternative perspectives; better experience because of opportunity to work on more complex projects than one individual can do; opportunity to develop professional skills through practice and feedback) Centre for the Study of Higher Education: http: //melbournecshe. unimelb. edu. au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/1770717/Group. pdf (Good reasons for group learning: (1) peer learning improves overall quality of student learning (2) Group work can help develop employable skills) Carnegie Mellon Teaching Excellence and Innovation Centre: https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/groupprojects/benefits. html (Benefits for students: research shows group experiences contribute to learning, retention and overall college success) References: Geoff Petty Research and Links: http: //geoffpetty. com/for-team-leaders/research-and-links/ Hattie: Influences on Student Learning: (findings from review of 30 years of educational research): http: //xn--www-rp 0 a. teacherstoolbox. co. uk/downloads/managers/Influencesonstudent. pdf Back to Rationale for Group Work

1 A Random assignment of students to groups Good if most student don’t know others. Good for preventing cliques and familiar, less challenging work patterns. Luck of the draw regarding each group having balanced abilities and personalities. Assigning to groups based on proximity or students’ choice is quickest, especially for large and cramped classes but it means that students work with friends or always with the same people. To vary group composition, randomly assign students to groups by counting off and grouping them according to number; or have them line up according to birthday, height, hair colour, etc. , before dividing them. Another idea is to distribute candy (e. g. , Starburst or hard, coloured candies) and group according to the flavour they choose. For many group tasks, the diversity within a group (gender, ethnicity, level of preparation) is especially important, so random is not so good for that. https: //uwaterloo. ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/teachingresources/teaching-tips/alternatives-lecturing/group-work/implementing-groupwork-classroom Back to Setup Menu

1 B Instructor assignment of students to groups Good whether students are strangers or not. Good for balancing abilities and personalities. Lack of choice may be demotivating to some. In situations where group dynamics and the challenge of working effectively as a group are an expected part of the learning, effective group work may be facilitated by having the instructor form the groups. In this case, it may be useful to consider matching group members; for example, students of similar ages or with similar backgrounds may work well together, depending on the nature and content of the task or project. Back to Setup Menu

1 C Let students self-select Good for motivating students because they have choice. May lead to cliques and exclusion of diversity. Letting students choose who will be in ‘their’ group might be the best way to set membership if: • You do not know them well • It is relatively early in the program • They need to work within familiar rules and behaviours • The task is relatively short-lived and/or straightforward • Assessment stresses the final product http: //www. economicsnetwork. ac. uk/showcase/carroll_diversity Click here for more details. Back to Setup Menu

Details on letting students self-select If learning about group dynamics is not one of the aims, students can selfselect. Some suggest that it's best to know and trust others so the group does not end up carrying a slacker, but this may be difficult for students who do not know anyone in their class. http: //melbournecshe. unimelb. edu. au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/1770717/Group. pdf Students tend to like choosing their own group members, but they often form groups that are homogenous—for example, in terms of gender, major, native language, culture, and race/ethnicity. However, this homogeneity may not support the learning objectives of the project. As a hybrid approach, allow students to select their own group members within particular constraints (e. g. , no groups have more than four members or more than one engineer, each needs 2 international students). https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/grou pprojects/compose. html 1 C 1 Back to Previous Screen Back to Setup Menu

1 D Assign according to personality profile Personality/work profile testing good whether students strangers or not, and for longer term stable group work. The idea is to match students whose profiles indicate they will work well together. Ask students to complete a short questionnaire about their competency in relevant skills or if there are interpersonal issues with classmates that would prevent effective group interaction. Some characteristics to determine: • Prior knowledge, previous experiences, and skills • Motivation • Diversity of perspectives • Students’ familiarity with each other • Personality Click here for more details. Back to Setup Menu

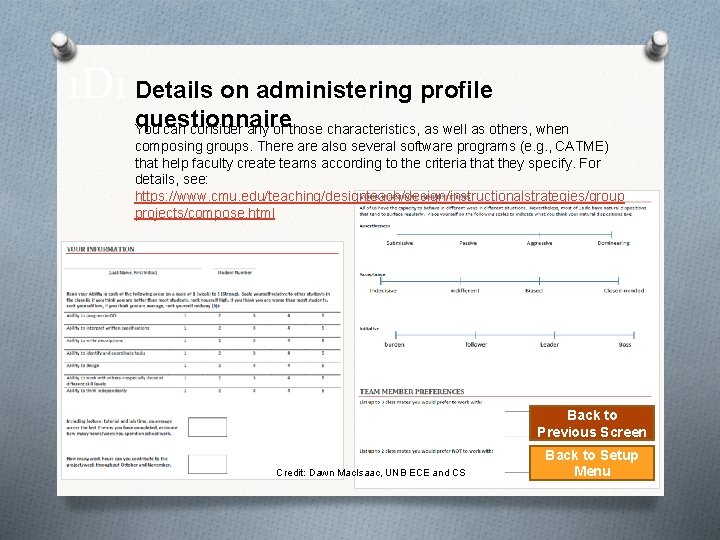

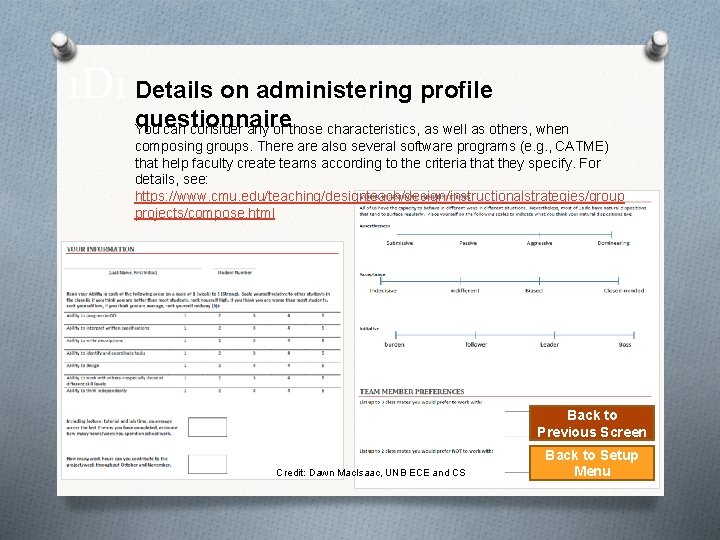

1 D 1 Details on administering profile questionnaire You can consider any of those characteristics, as well as others, when composing groups. There also several software programs (e. g. , CATME) that help faculty create teams according to the criteria that they specify. For details, see: https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/group projects/compose. html Examples: Back to Previous Screen Credit: Dawn Mac. Isaac, UNB ECE and CS Back to Setup Menu

What is the best group size? Small groups work better because it is easier to coordinate efforts and schedules among fewer people. The less skillful the students, the smaller the groups should be. However, although large groups have higher coordination costs, they can theoretically accomplish larger and more complex projects. Some experts claim that groups of more than five or six students tend to be unmanageable, but there are no firm rules. The group size you choose will depend on the total number of students, the size of the classroom, the diversity desired, and the nature of the task. Groups of 4 -5 tend to balance well the needs for diversity, productivity, active participation, and cohesion. https: //uwaterloo. ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/teachingresources/teaching-tips/alternatives-lecturing/group-work/implementing-group-workclassroom From experience and research, the optimum team size is 4 -7 members. http: //humanresources. about. com/od/teambuildingfaqs/f/optimum-team-size. htm Like other aspects of group work, the size of a group should be shaped by the project’s learning objectives. https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/groupproje cts/compose. html#identifycharacteristics Back to Setup Menu 3 A

How well do students know each other? Ask students if they have worked effectively with classmates on previous group projects. Those who have worked together effectively in groups before may be more likely to work together effectively again. If the focus is more on the product than the process of group work, this may be a relevant characteristic. Consider the trade-off between the improved speed and efficiency and potential higher levels of accomplishment of students familiar with working together on the one hand with the additional skills students will develop by learning to work with a wider variety of people, some from scratch. If you are assigning another group project later in the course, or expect to in a future course that the students may enroll in, it may be useful to group students in a way that meets the present project’s learning objectives and prepares students to work together again in the future. https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/groupproje cts/compose. html 4 A Back to Setup Menu

Steps to ensure international students are included Where home students predominate, it’s best to have 2 international students in some groups and none in others than to have lone international students in every group. Ensure at least two international students in groups where home students predominate—this is more effective than having one in each of the groups. If the two international students speak the same mother tongue, help the group establish norms regarding when those students work in their mother tongue and when in English, to ensure everyone’s expectations are aligned. Global conflicts: Students from some areas will not necessarily find it easy to work together. If you know your students, you could explore this aspect with them. The size of the group and the relative diversity of membership: Four to seven is considered optimal; very diverse groups (however you define this) may need to be smaller because it may take longer for such groups to perform tasks due to the additional time needed to work through second language instructions and unfamiliar norms. http: //www. economicsnetwork. ac. uk/showcase/carroll_diversity 4 B Back to Setup Menu

Provide role descriptions, yes or no? Students less familiar with university group work, such as some international students and first year students, may find clear guidelines about roles and expected contributions useful. Students may find simple suggestions about possible roles (for example, leader, note taker and so on) useful for guiding their own discussions about roles. Similarly, a discussion of the responsibility each group member has to the others in their group will not only provide guidance in what to reasonably expect from others but also in what other members are likely to expect from individual students in terms of contributions. If students can create or modify instructor-provided roles to fit their context, they may be more motivated or personally invested in their performance. Typically, this student crafting of their group roles would work better the more students have experience working in groups. If students have a lot of input into their roles, they would benefit from the instructor emphasizing that they challenge themselves to higher levels of performance or to tasks with which they may not be that comfortable, in order to maximize the potential for academic and personal growth. 5 A Back to Setup Menu

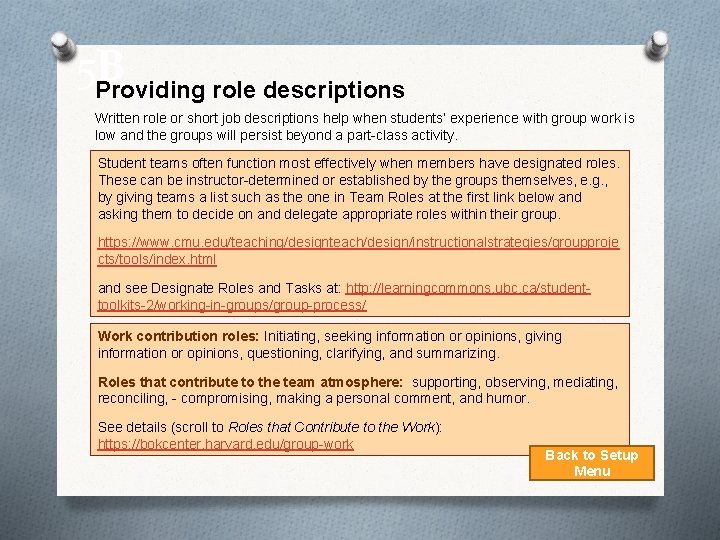

5 B Providing role descriptions Written role or short job descriptions help when students’ experience with group work is low and the groups will persist beyond a part-class activity. Student teams often function most effectively when members have designated roles. These can be instructor-determined or established by the groups themselves, e. g. , by giving teams a list such as the one in Team Roles at the first link below and asking them to decide on and delegate appropriate roles within their group. https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/groupproje cts/tools/index. html and see Designate Roles and Tasks at: http: //learningcommons. ubc. ca/studenttoolkits-2/working-in-groups/group-process/ Work contribution roles: Initiating, seeking information or opinions, giving information or opinions, questioning, clarifying, and summarizing. Roles that contribute to the team atmosphere: supporting, observing, mediating, reconciling, - compromising, making a personal comment, and humor. See details (scroll to Roles that Contribute to the Work): https: //bokcenter. harvard. edu/group-work Back to Setup Menu

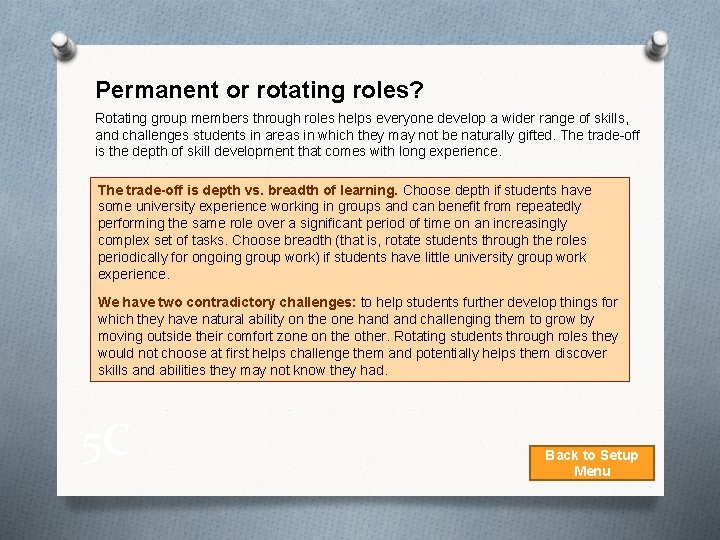

Permanent or rotating roles? Rotating group members through roles helps everyone develop a wider range of skills, and challenges students in areas in which they may not be naturally gifted. The trade-off is the depth of skill development that comes with long experience. The trade-off is depth vs. breadth of learning. Choose depth if students have some university experience working in groups and can benefit from repeatedly performing the same role over a significant period of time on an increasingly complex set of tasks. Choose breadth (that is, rotate students through the roles periodically for ongoing group work) if students have little university group work experience. We have two contradictory challenges: to help students further develop things for which they have natural ability on the one hand challenging them to grow by moving outside their comfort zone on the other. Rotating students through roles they would not choose at first helps challenge them and potentially helps them discover skills and abilities they may not know they had. 5 C Back to Setup Menu

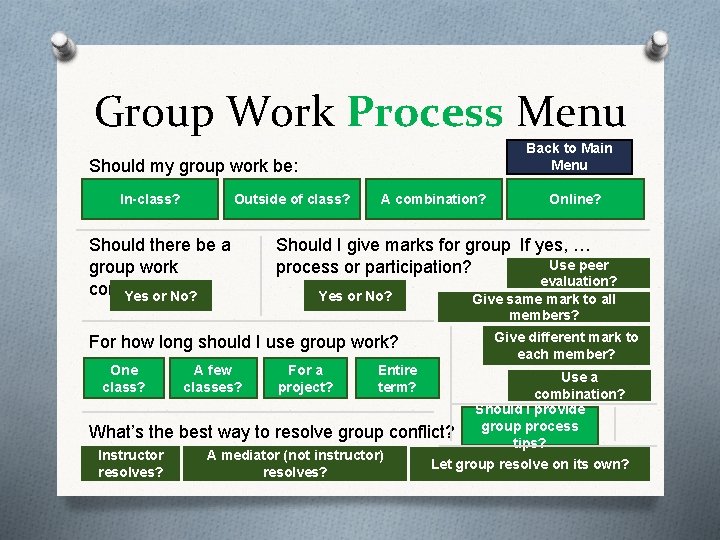

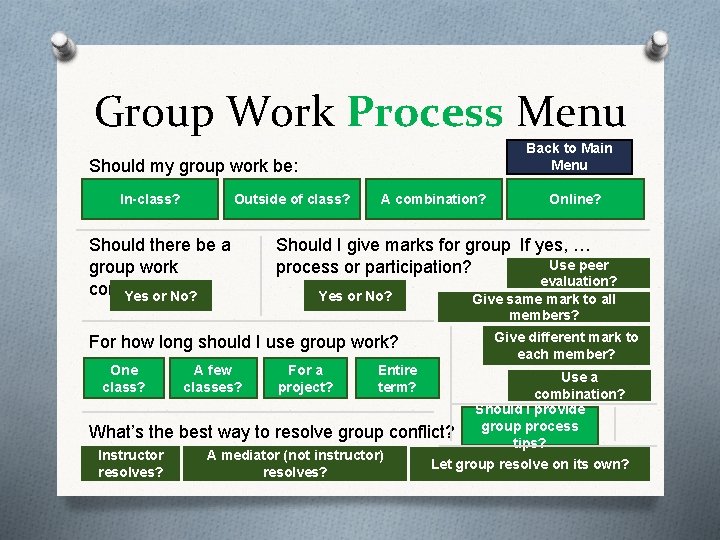

Group Work Process Menu Back to Main Menu Should my group work be: In-class? Outside of class? Should there be a group work contract? Yes or No? A combination? Should I give marks for group If yes, … Use peer process or participation? Yes or No? For how long should I use group work? One class? What’s the Instructor resolves? A few classes? Online? For a project? Entire term? evaluation? Give same mark to all members? Give different mark to each member? Use a combination? Should I provide best way to resolve group conflict? group process tips? A mediator (not instructor) Let group resolve on its own? resolves?

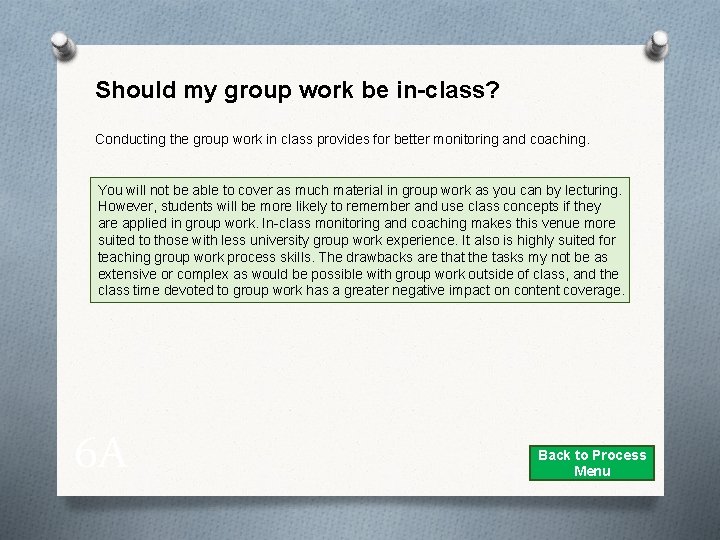

Should my group work be in-class? Conducting the group work in class provides for better monitoring and coaching. You will not be able to cover as much material in group work as you can by lecturing. However, students will be more likely to remember and use class concepts if they are applied in group work. In-class monitoring and coaching makes this venue more suited to those with less university group work experience. It also is highly suited for teaching group work process skills. The drawbacks are that the tasks my not be as extensive or complex as would be possible with group work outside of class, and the class time devoted to group work has a greater negative impact on content coverage. 6 A Back to Process Menu

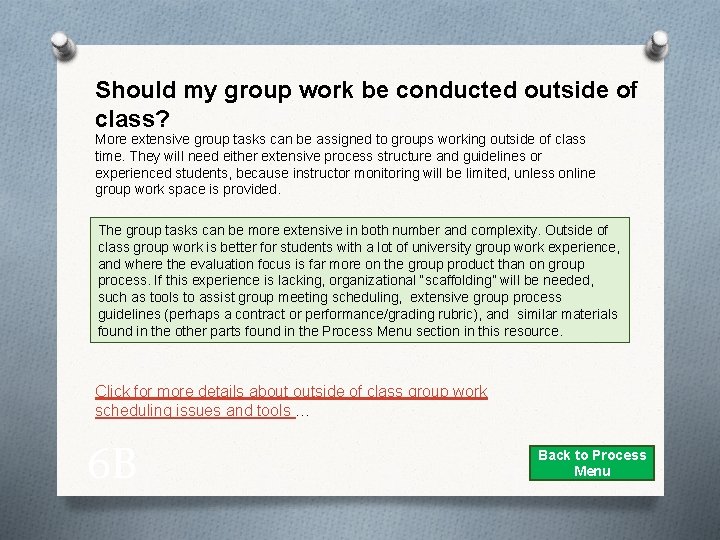

Should my group work be conducted outside of class? More extensive group tasks can be assigned to groups working outside of class time. They will need either extensive process structure and guidelines or experienced students, because instructor monitoring will be limited, unless online group work space is provided. The group tasks can be more extensive in both number and complexity. Outside of class group work is better for students with a lot of university group work experience, and where the evaluation focus is far more on the group product than on group process. If this experience is lacking, organizational “scaffolding” will be needed, such as tools to assist group meeting scheduling, extensive group process guidelines (perhaps a contract or performance/grading rubric), and similar materials found in the other parts found in the Process Menu section in this resource. Click for more details about outside of class group work scheduling issues and tools … 6 B Back to Process Menu

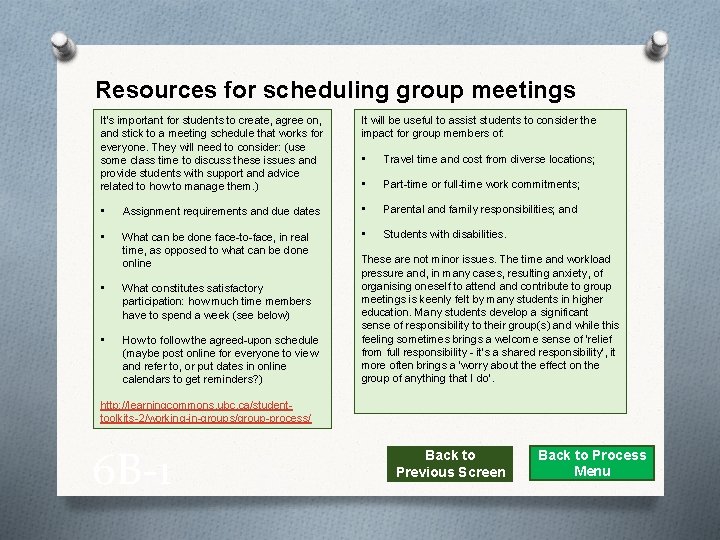

Resources for scheduling group meetings It’s important for students to create, agree on, and stick to a meeting schedule that works for everyone. They will need to consider: (use some class time to discuss these issues and provide students with support and advice related to how to manage them. ) It will be useful to assist students to consider the impact for group members of: • • • Travel time and cost from diverse locations; • Part-time or full-time work commitments; Assignment requirements and due dates • Parental and family responsibilities; and What can be done face-to-face, in real time, as opposed to what can be done online • Students with disabilities. • What constitutes satisfactory participation: how much time members have to spend a week (see below) • How to follow the agreed-upon schedule (maybe post online for everyone to view and refer to, or put dates in online calendars to get reminders? ) These are not minor issues. The time and workload pressure and, in many cases, resulting anxiety, of organising oneself to attend and contribute to group meetings is keenly felt by many students in higher education. Many students develop a significant sense of responsibility to their group(s) and while this feeling sometimes brings a welcome sense of 'relief from full responsibility - it's a shared responsibility', it more often brings a 'worry about the effect on the group of anything that I do’. http: //learningcommons. ubc. ca/studenttoolkits-2/working-in-groups/group-process/ 6 B-1 Back to Previous Screen Back to Process Menu

Should my group work be a combination of inclass and outside of class? A combination of in-class and outside class group work allows for easier monitoring while providing time for more extensive group tasks. A combination of in-class and outside class group work is a good transition for students with some university group work experience who are ready to move to more extensive group work tasks or those focused more on product than process. The in-class time allows for monitoring and coaching of group process, as well as troubleshooting issues, and working outside of class provides opportunities for developing more independence while learning to work with others. 6 C Back to Process Menu

Should my group work be online? Online group work makes better instructor monitoring possible than for typical outside-ofclass group work. Your main contribution will be to provide tools that help students work online. An online group signup and work space is provided in D 2 L Brightspace (scroll to the Group heading) http: //www. unb. ca/fredericton/cetl/tls/educational/d 2 l/facvideos. html. This space lets students schedule work, discuss the work, share work files, provide feedback on those files, compile finalized work, and submit it to the instructor. As an instructor, you will be able to see how often and what each member contributes. Fairness requires that you let students know you will be able to do this and it will be good to reassure them that no one outside their group will be able to see their workspace or work product. For more details on how the online tools work, see: https: //vimeo. com/228107728 6 D Back to Process Menu

7 Should we have a group work contract? Group contracts are statements of responsibilities and expectations and are especially useful for students with little university group work experience or even with more experienced students when group work is a major instructional strategy, ongoing, and the output is substantial. In this case, clear, explicit criteria for roles, expectations, and work product are highly recommended to ensure fairness to all students. There are several things to consider: • Does the instructor create the contract, do students, or is it a combined effort? • How extensive should it be? • What are the consequences of it not being followed? • How are disagreements settled? Click here to see sample group contracts… Back to Process Menu

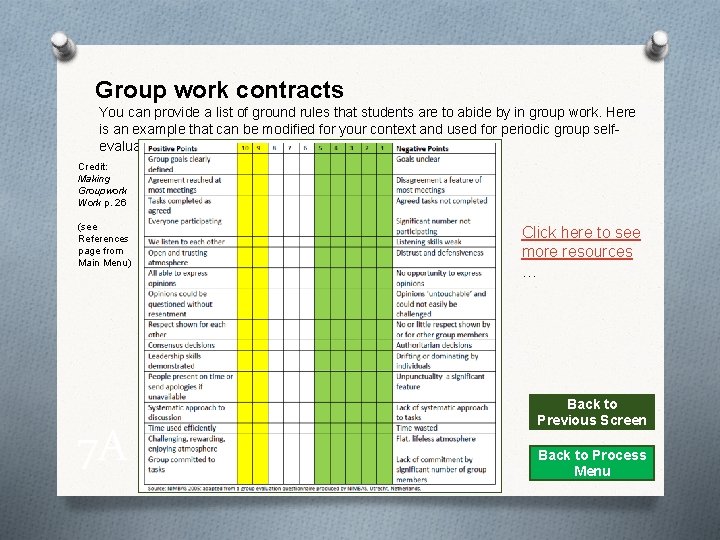

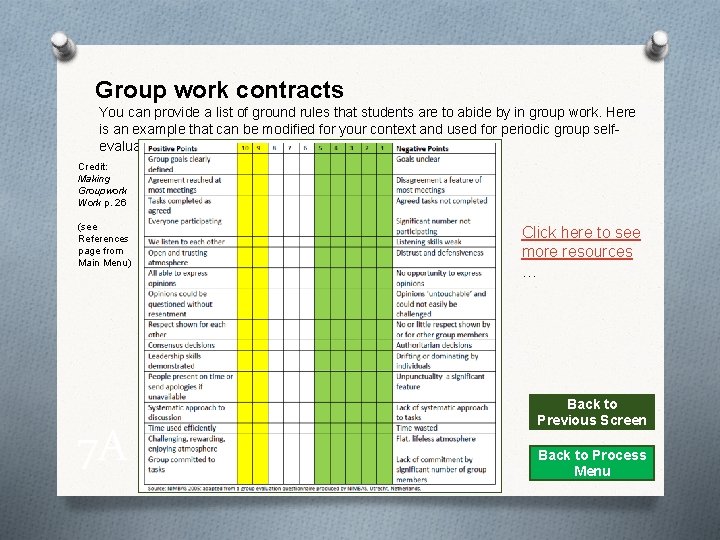

Group work contracts You can provide a list of ground rules that students are to abide by in group work. Here is an example that can be modified for your context and used for periodic group selfevaluation: Credit: Making Groupwork Work p. 26 (see References page from Main Menu) 7 A Click here to see more resources … Back to Previous Screen Back to Process Menu

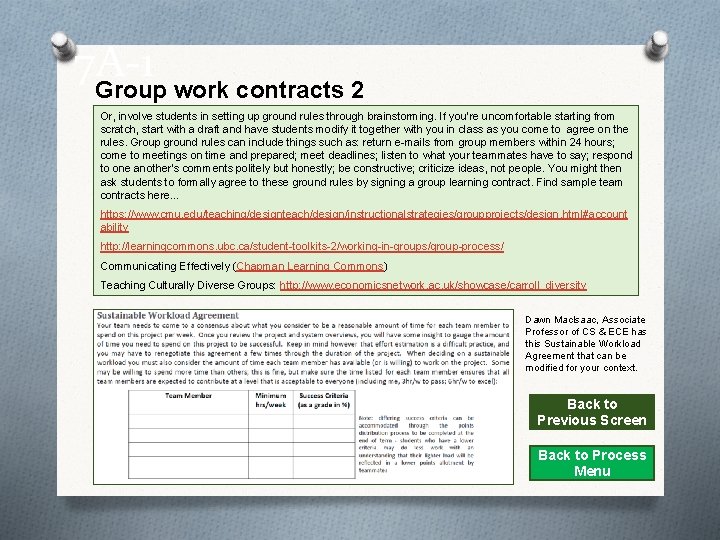

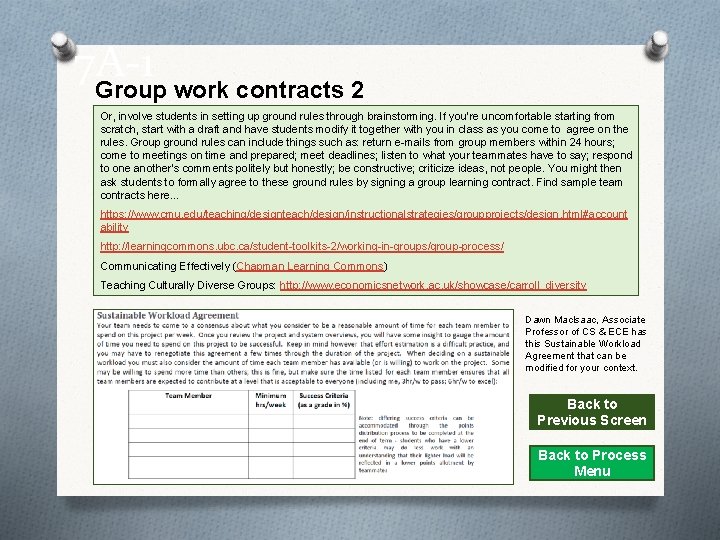

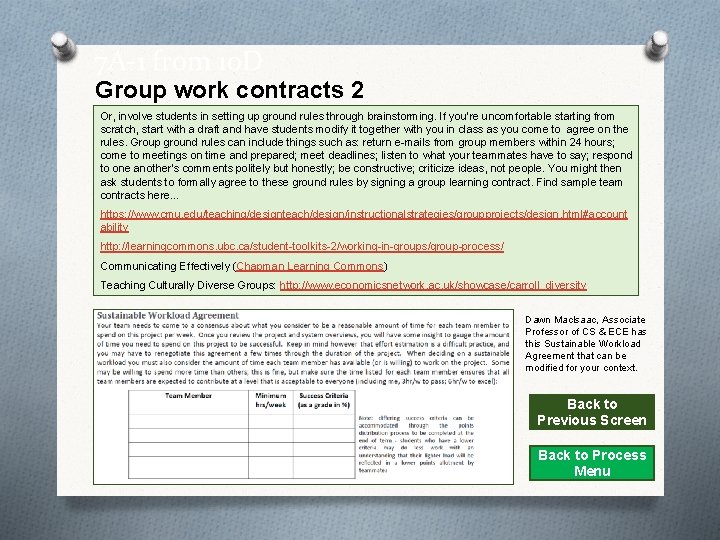

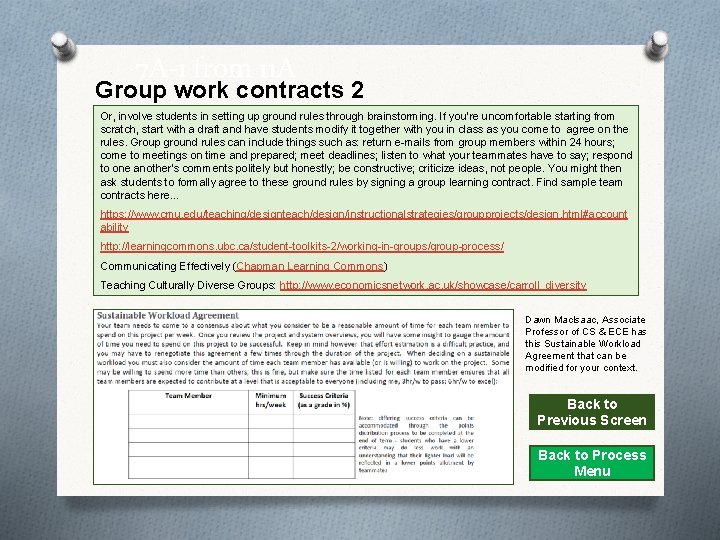

7 A-1 Group work contracts 2 Or, involve students in setting up ground rules through brainstorming. If you’re uncomfortable starting from scratch, start with a draft and have students modify it together with you in class as you come to agree on the rules. Group ground rules can include things such as: return e-mails from group members within 24 hours; come to meetings on time and prepared; meet deadlines; listen to what your teammates have to say; respond to one another’s comments politely but honestly; be constructive; criticize ideas, not people. You might then ask students to formally agree to these ground rules by signing a group learning contract. Find sample team contracts here… https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/groupprojects/design. html#account ability http: //learningcommons. ubc. ca/student-toolkits-2/working-in-groups/group-process/ Communicating Effectively (Chapman Learning Commons) Teaching Culturally Diverse Groups: http: //www. economicsnetwork. ac. uk/showcase/carroll_diversity Dawn Mac. Isaac, Associate Professor of CS & ECE has this Sustainable Workload Agreement that can be modified for your context. Back to Previous Screen Back to Process Menu

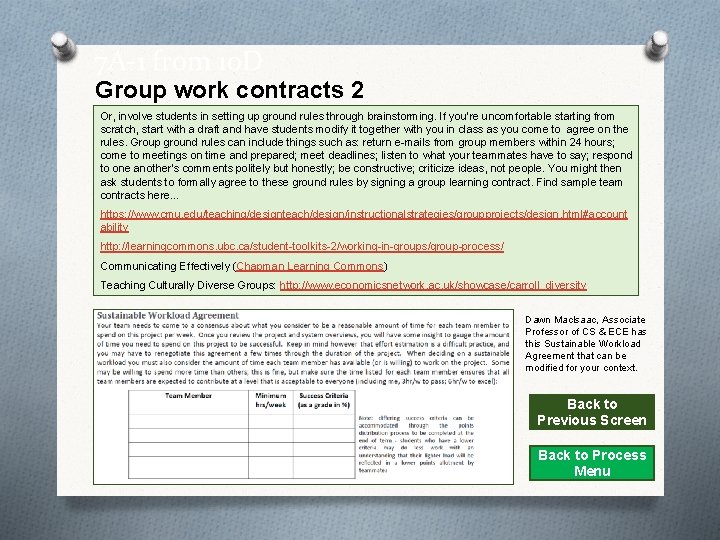

7 A-1 from 10 D Group work contracts 2 Or, involve students in setting up ground rules through brainstorming. If you’re uncomfortable starting from scratch, start with a draft and have students modify it together with you in class as you come to agree on the rules. Group ground rules can include things such as: return e-mails from group members within 24 hours; come to meetings on time and prepared; meet deadlines; listen to what your teammates have to say; respond to one another’s comments politely but honestly; be constructive; criticize ideas, not people. You might then ask students to formally agree to these ground rules by signing a group learning contract. Find sample team contracts here… https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/groupprojects/design. html#account ability http: //learningcommons. ubc. ca/student-toolkits-2/working-in-groups/group-process/ Communicating Effectively (Chapman Learning Commons) Teaching Culturally Diverse Groups: http: //www. economicsnetwork. ac. uk/showcase/carroll_diversity Dawn Mac. Isaac, Associate Professor of CS & ECE has this Sustainable Workload Agreement that can be modified for your context. Back to Previous Screen Back to Process Menu

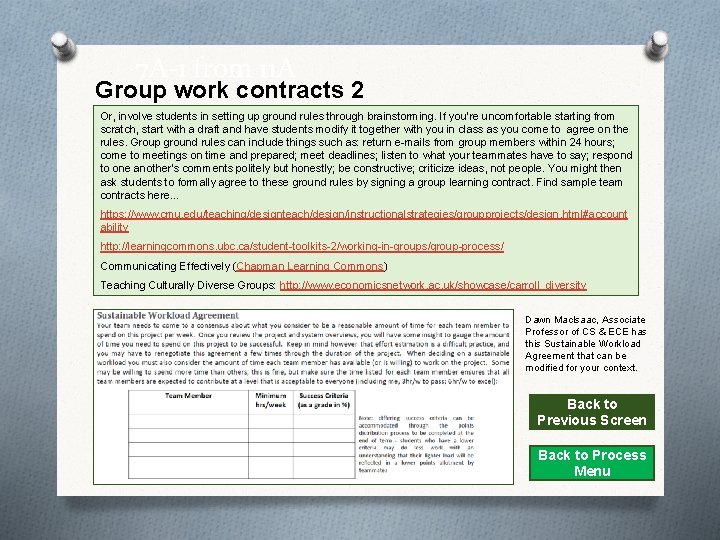

7 A-1 from 11 A Group work contracts 2 Or, involve students in setting up ground rules through brainstorming. If you’re uncomfortable starting from scratch, start with a draft and have students modify it together with you in class as you come to agree on the rules. Group ground rules can include things such as: return e-mails from group members within 24 hours; come to meetings on time and prepared; meet deadlines; listen to what your teammates have to say; respond to one another’s comments politely but honestly; be constructive; criticize ideas, not people. You might then ask students to formally agree to these ground rules by signing a group learning contract. Find sample team contracts here… https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/groupprojects/design. html#account ability http: //learningcommons. ubc. ca/student-toolkits-2/working-in-groups/group-process/ Communicating Effectively (Chapman Learning Commons) Teaching Culturally Diverse Groups: http: //www. economicsnetwork. ac. uk/showcase/carroll_diversity Dawn Mac. Isaac, Associate Professor of CS & ECE has this Sustainable Workload Agreement that can be modified for your context. Back to Previous Screen Back to Process Menu

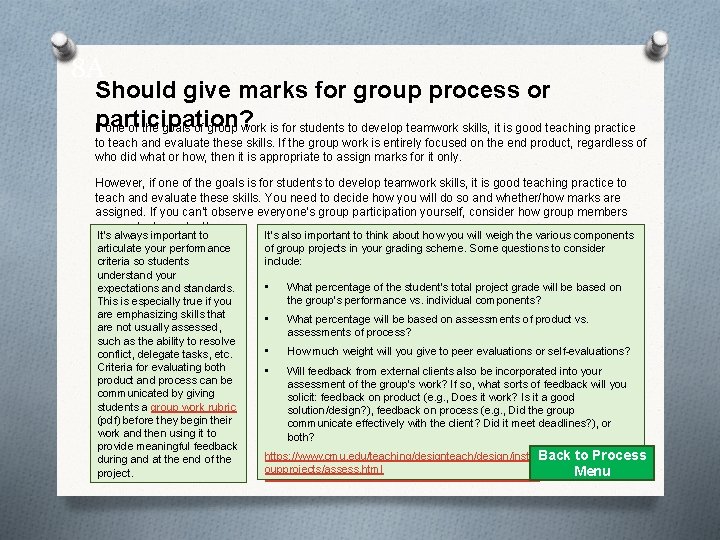

8 A Should give marks for group process or participation? If one of the goals of group work is for students to develop teamwork skills, it is good teaching practice to teach and evaluate these skills. If the group work is entirely focused on the end product, regardless of who did what or how, then it is appropriate to assign marks for it only. However, if one of the goals is for students to develop teamwork skills, it is good teaching practice to teach and evaluate these skills. You need to decide how you will do so and whether/how marks are assigned. If you can’t observe everyone’s group participation yourself, consider how group members can evaluate each other. It’s always important to articulate your performance criteria so students understand your expectations and standards. This is especially true if you are emphasizing skills that are not usually assessed, such as the ability to resolve conflict, delegate tasks, etc. Criteria for evaluating both product and process can be communicated by giving students a group work rubric (pdf) before they begin their work and then using it to provide meaningful feedback during and at the end of the project. It’s also important to think about how you will weigh the various components of group projects in your grading scheme. Some questions to consider include: • What percentage of the student’s total project grade will be based on the group’s performance vs. individual components? • What percentage will be based on assessments of product vs. assessments of process? • How much weight will you give to peer evaluations or self-evaluations? • Will feedback from external clients also be incorporated into your assessment of the group’s work? If so, what sorts of feedback will you solicit: feedback on product (e. g. , Does it work? Is it a good solution/design? ), feedback on process (e. g. , Did the group communicate effectively with the client? Did it meet deadlines? ), or both? Back to Process https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/gr oupprojects/assess. html Menu Click for teamwork evaluation methods…

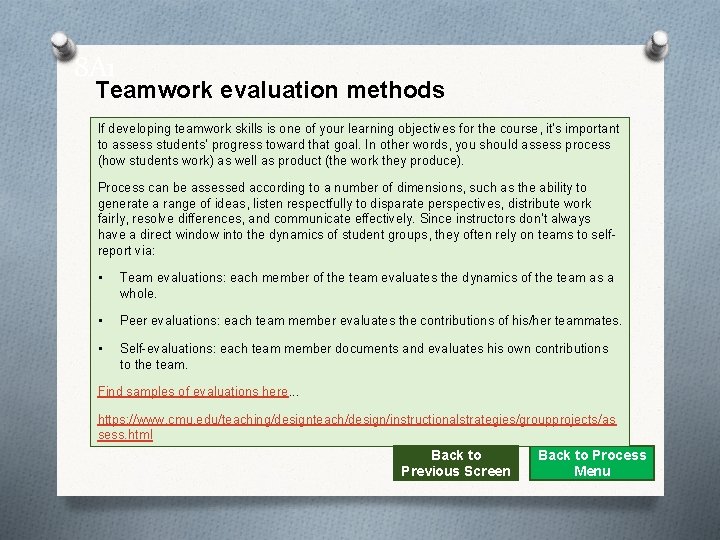

8 A 1 Teamwork evaluation methods If developing teamwork skills is one of your learning objectives for the course, it’s important to assess students’ progress toward that goal. In other words, you should assess process (how students work) as well as product (the work they produce). Process can be assessed according to a number of dimensions, such as the ability to generate a range of ideas, listen respectfully to disparate perspectives, distribute work fairly, resolve differences, and communicate effectively. Since instructors don’t always have a direct window into the dynamics of student groups, they often rely on teams to selfreport via: • Team evaluations: each member of the team evaluates the dynamics of the team as a whole. • Peer evaluations: each team member evaluates the contributions of his/her teammates. • Self-evaluations: each team member documents and evaluates his own contributions to the team. Find samples of evaluations here. . . https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/groupprojects/as sess. html Back to Previous Screen Back to Process Menu

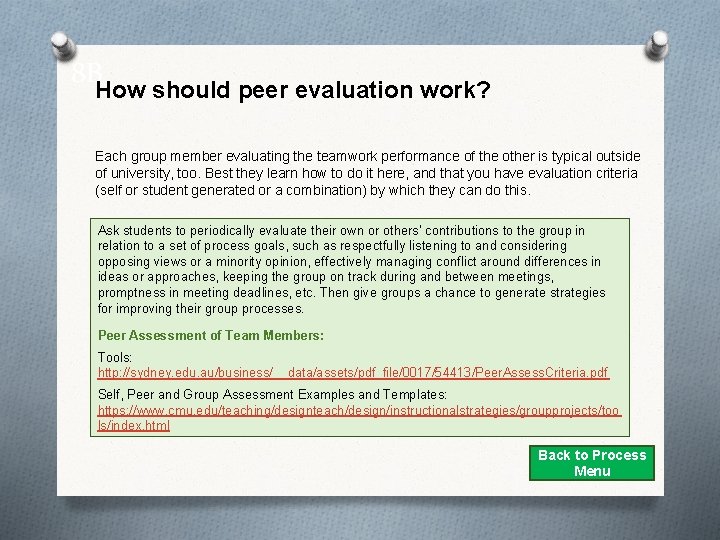

8 B How should peer evaluation work? Each group member evaluating the teamwork performance of the other is typical outside of university, too. Best they learn how to do it here, and that you have evaluation criteria (self or student generated or a combination) by which they can do this. Ask students to periodically evaluate their own or others’ contributions to the group in relation to a set of process goals, such as respectfully listening to and considering opposing views or a minority opinion, effectively managing conflict around differences in ideas or approaches, keeping the group on track during and between meetings, promptness in meeting deadlines, etc. Then give groups a chance to generate strategies for improving their group processes. Peer Assessment of Team Members: Tools: http: //sydney. edu. au/business/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/54413/Peer. Assess. Criteria. pdf Self, Peer and Group Assessment Examples and Templates: https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/groupprojects/too ls/index. html Back to Process Menu

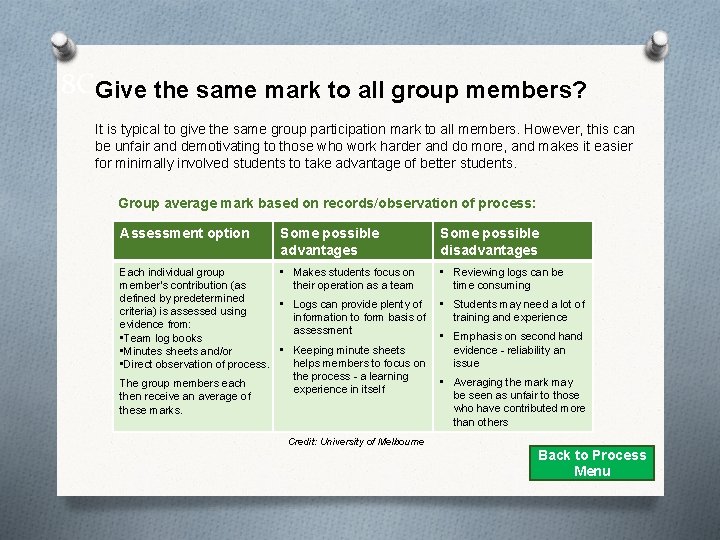

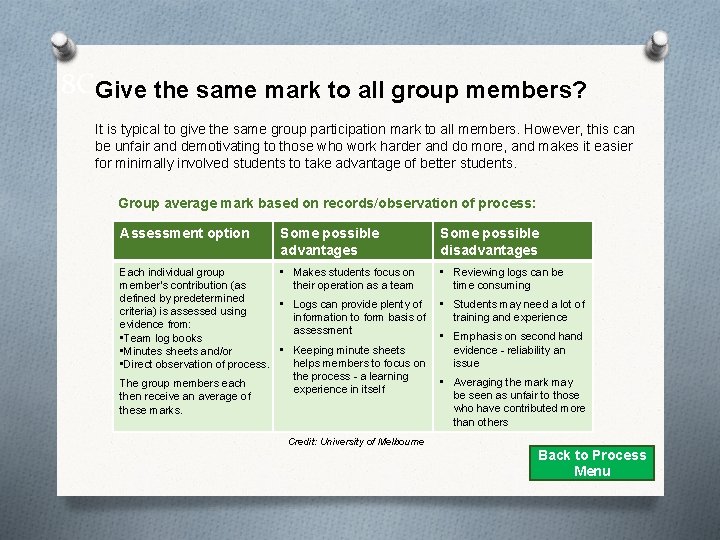

8 CGive the same mark to all group members? It is typical to give the same group participation mark to all members. However, this can be unfair and demotivating to those who work harder and do more, and makes it easier for minimally involved students to take advantage of better students. Group average mark based on records/observation of process: Assessment option Some possible advantages Each individual group • Makes students focus on member's contribution (as their operation as a team defined by predetermined • Logs can provide plenty of criteria) is assessed using information to form basis of evidence from: assessment • Team log books • Keeping minute sheets • Minutes sheets and/or helps members to focus on • Direct observation of process. the process - a learning The group members each experience in itself then receive an average of these marks. Credit: University of Melbourne Some possible disadvantages • Reviewing logs can be time consuming • Students may need a lot of training and experience • Emphasis on second hand evidence - reliability an issue • Averaging the mark may be seen as unfair to those who have contributed more than others Back to Process Menu

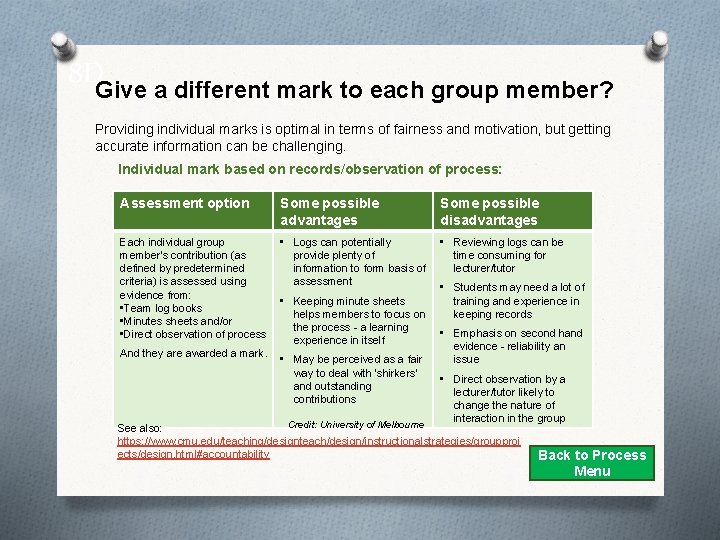

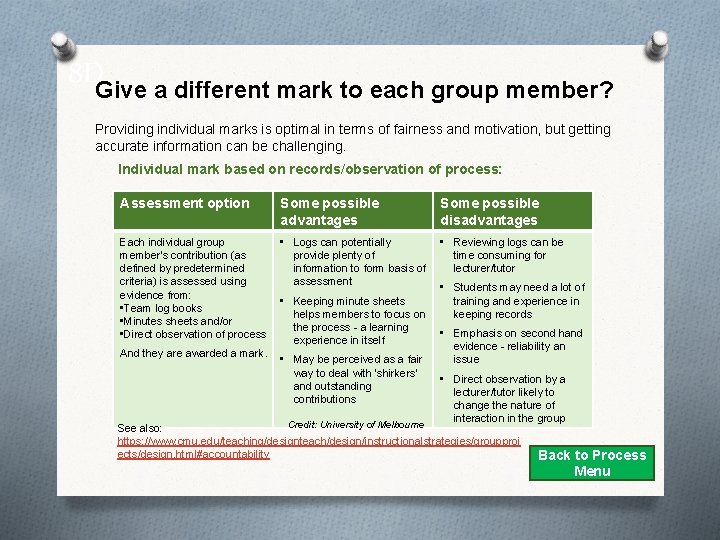

8 D Give a different mark to each group member? Providing individual marks is optimal in terms of fairness and motivation, but getting accurate information can be challenging. Individual mark based on records/observation of process: Assessment option Some possible advantages Some possible disadvantages Each individual group member's contribution (as defined by predetermined criteria) is assessed using evidence from: • Team log books • Minutes sheets and/or • Direct observation of process • Logs can potentially provide plenty of information to form basis of assessment • Reviewing logs can be time consuming for lecturer/tutor And they are awarded a mark. • Keeping minute sheets helps members to focus on the process - a learning experience in itself • May be perceived as a fair way to deal with 'shirkers' and outstanding contributions • Students may need a lot of training and experience in keeping records • Emphasis on second hand evidence - reliability an issue • Direct observation by a lecturer/tutor likely to change the nature of interaction in the group Credit: University of Melbourne See also: https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/groupproj ects/design. html#accountability Back to Process Menu

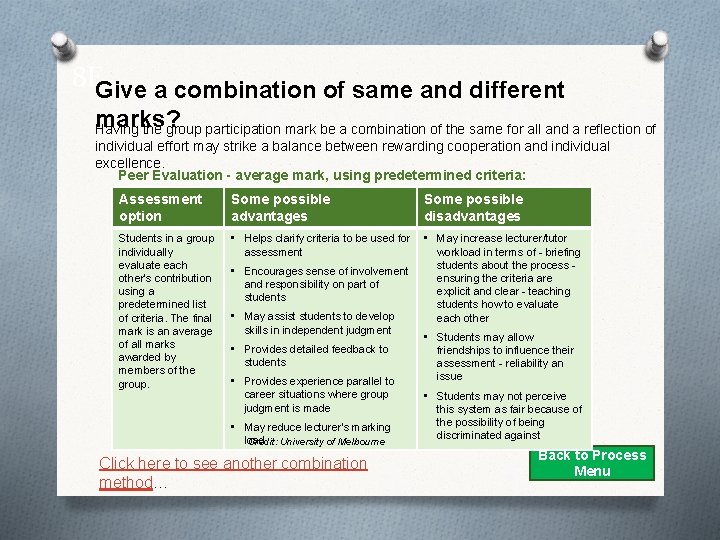

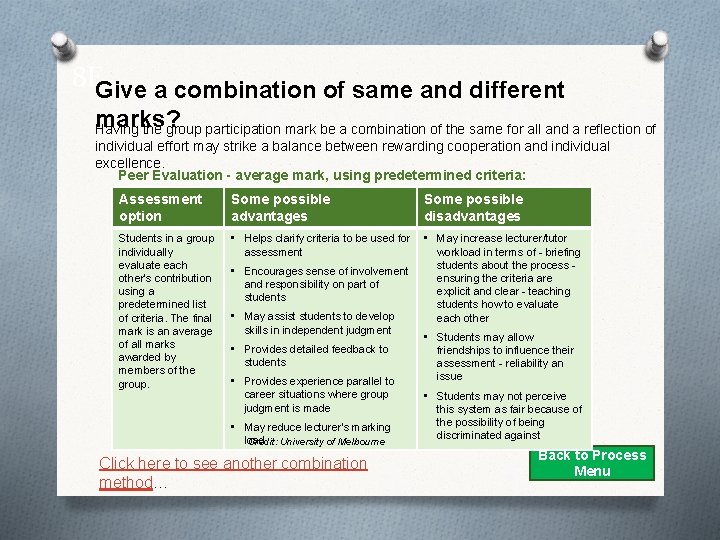

8 EGive a combination of same and different marks? Having the group participation mark be a combination of the same for all and a reflection of individual effort may strike a balance between rewarding cooperation and individual excellence. Peer Evaluation - average mark, using predetermined criteria: Assessment option Some possible advantages Some possible disadvantages Students in a group individually evaluate each other's contribution using a predetermined list of criteria. The final mark is an average of all marks awarded by members of the group. • Helps clarify criteria to be used for assessment • May increase lecturer/tutor workload in terms of - briefing students about the process ensuring the criteria are explicit and clear - teaching students how to evaluate each other • Encourages sense of involvement and responsibility on part of students • May assist students to develop skills in independent judgment • Provides detailed feedback to students • Provides experience parallel to career situations where group judgment is made • May reduce lecturer's marking load Credit: University of Melbourne Click here to see another combination method… • Students may allow friendships to influence their assessment - reliability an issue • Students may not perceive this system as fair because of the possibility of being discriminated against Back to Process Menu

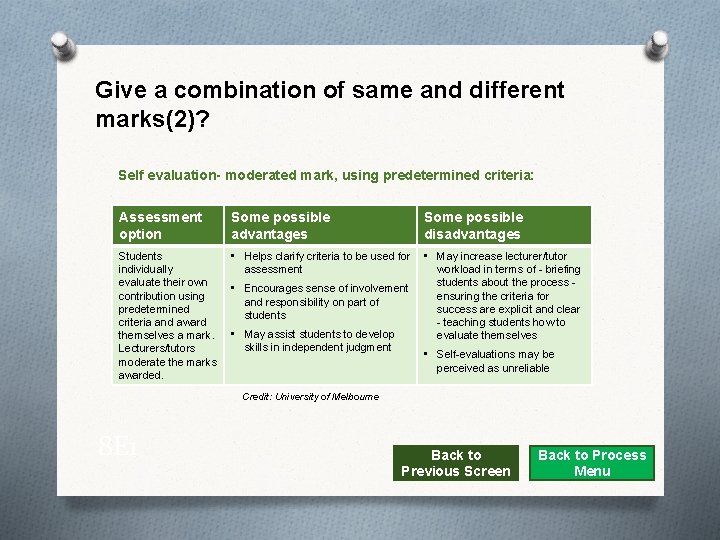

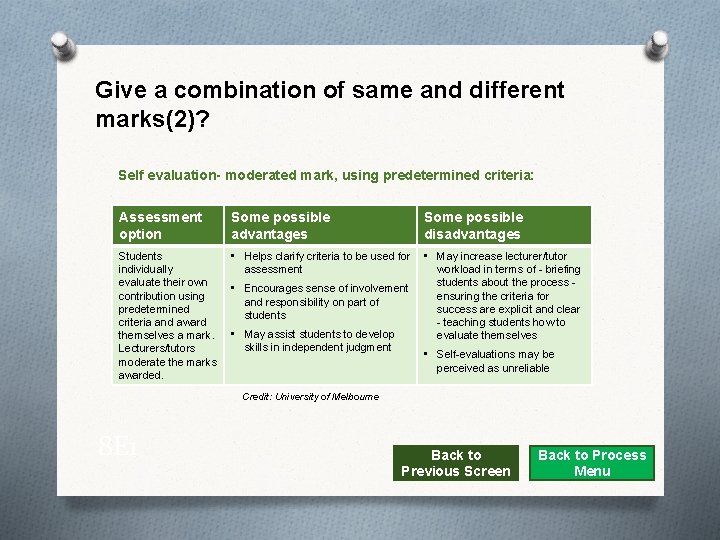

Give a combination of same and different marks(2)? Self evaluation- moderated mark, using predetermined criteria: Assessment option Some possible advantages Some possible disadvantages Students individually evaluate their own contribution using predetermined criteria and award themselves a mark. Lecturers/tutors moderate the marks awarded. • Helps clarify criteria to be used for assessment • May increase lecturer/tutor workload in terms of - briefing students about the process ensuring the criteria for success are explicit and clear - teaching students how to evaluate themselves • Encourages sense of involvement and responsibility on part of students • May assist students to develop skills in independent judgment • Self-evaluations may be perceived as unreliable Credit: University of Melbourne 8 E 1 Back to Previous Screen Back to Process Menu

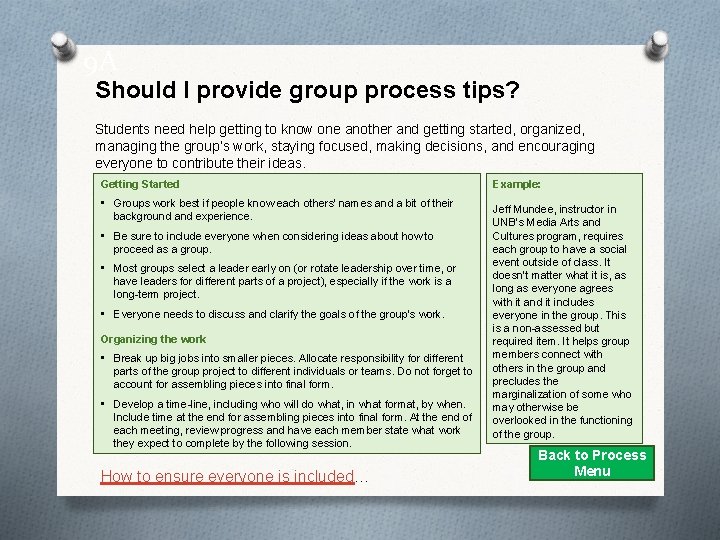

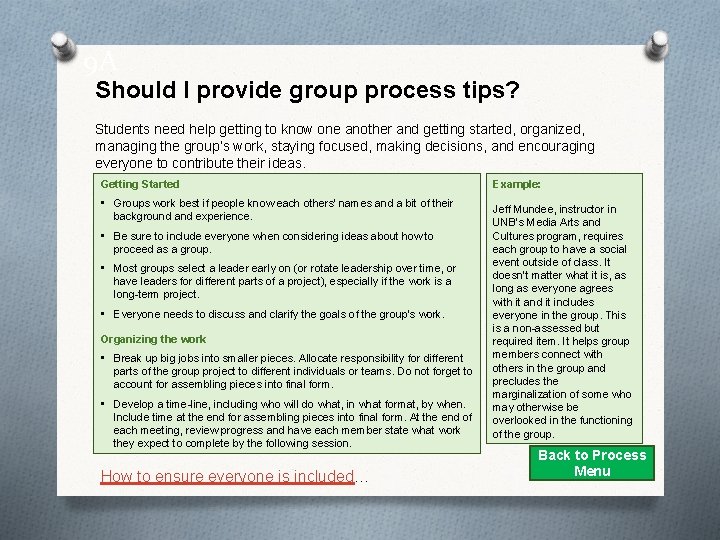

9 A Should I provide group process tips? Students need help getting to know one another and getting started, organized, managing the group’s work, staying focused, making decisions, and encouraging everyone to contribute their ideas. Getting Started • Groups work best if people know each others' names and a bit of their background and experience. • Be sure to include everyone when considering ideas about how to proceed as a group. • Most groups select a leader early on (or rotate leadership over time, or have leaders for different parts of a project), especially if the work is a long-term project. • Everyone needs to discuss and clarify the goals of the group's work. Organizing the work • Break up big jobs into smaller pieces. Allocate responsibility for different parts of the group project to different individuals or teams. Do not forget to account for assembling pieces into final form. • Develop a time-line, including who will do what, in what format, by when. Include time at the end for assembling pieces into final form. At the end of each meeting, review progress and have each member state what work they expect to complete by the following session. How to ensure everyone is included… Example: Jeff Mundee, instructor in UNB’s Media Arts and Cultures program, requires each group to have a social event outside of class. It doesn’t matter what it is, as long as everyone agrees with it and it includes everyone in the group. This is a non-assessed but required item. It helps group members connect with others in the group and precludes the marginalization of some who may otherwise be overlooked in the functioning of the group. Back to Process Menu

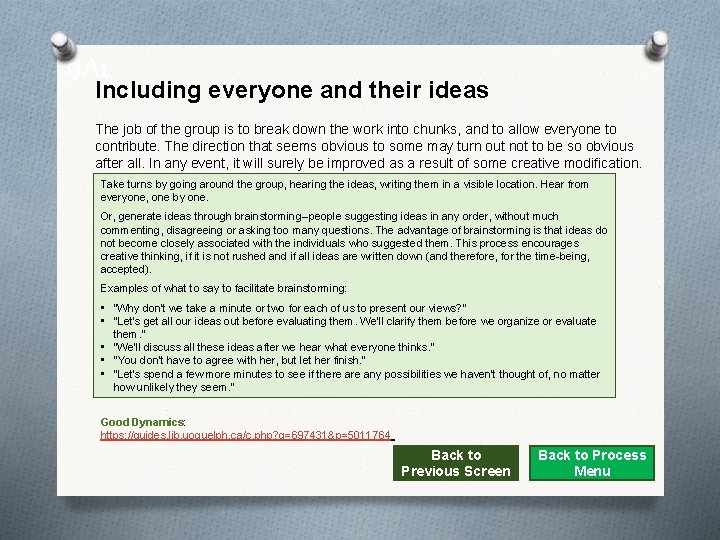

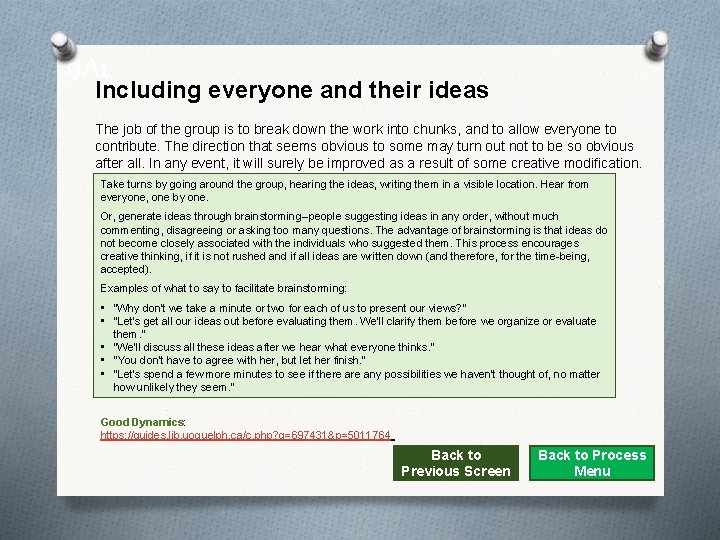

9 A 1 Including everyone and their ideas The job of the group is to break down the work into chunks, and to allow everyone to contribute. The direction that seems obvious to some may turn out not to be so obvious after all. In any event, it will surely be improved as a result of some creative modification. Take turns by going around the group, hearing the ideas, writing them in a visible location. Hear from everyone, one by one. Or, generate ideas through brainstorming--people suggesting ideas in any order, without much commenting, disagreeing or asking too many questions. The advantage of brainstorming is that ideas do not become closely associated with the individuals who suggested them. This process encourages creative thinking, if it is not rushed and if all ideas are written down (and therefore, for the time-being, accepted). Examples of what to say to facilitate brainstorming: • “Why don't we take a minute or two for each of us to present our views? ” • “Let's get all our ideas out before evaluating them. We'll clarify them before we organize or evaluate them. ” • “We'll discuss all these ideas after we hear what everyone thinks. ” • “You don't have to agree with her, but let her finish. ” • “Let's spend a few more minutes to see if there any possibilities we haven't thought of, no matter how unlikely they seem. ” Good Dynamics: https: //guides. lib. uoguelph. ca/c. php? g=697431&p=5011764 Back to Previous Screen Back to Process Menu

When should I use group work of one class duration? Group work of one class duration is good for immediate application of newly encountered concepts, the idea being that the act of articulating one’s understanding to others and reconciling differing aspects of people’s understanding helps students process the concept and learn it more deeply than listening individually. 10 A Back to Process Menu

When should I use group work of a few classes duration? Working together for a few classes helps students move beyond superficial group work skills, and perhaps work on deliverables that are more substantial (and thus lead to more complex application). Another option is to work on different things each class with the goal of the group being able to get things done progressively more quickly as group members’ abilities, interests, and contribution types become better known. Poor group work habits or personality conflicts are likely to be let slide rather than be dealt with because it’s easier to wait until the groups change than to deal with them. 10 B Back to Process Menu

Keeping the group together for the project duration “Project duration” means the group stays together for whatever length needed to complete a project, whether a few weeks or a month or two. The assumption is that a project is more substantial than shorter duration group work, and thus has higher potential for deeper learning. In this situation, any individual poor work habits or personality conflicts that may exist require some support in resolving because it is necessary for the success of the project (see conflict management items in Process Menu). Faculty asking students to work in groups over a long period of time can do a few things to make it easy for the students to work: • The biggest student complaint about group work is that it takes a lot of time and planning. Let students know about the project at the beginning of the term, so they can plan their time. • At the outset, provide group guidelines and your expectations (or start with yours and negotiate a final version with the students). • Monitor the groups periodically to make sure they are functioning effectively. • If the project is to be completed outside of class, provide scheduling support, such as online group workspace in D 2 L Brightspace https: //vimeo. com/228107728. Some faculty members provide in-class time for groups to meet. Others help students find rooms in which to meet. https: //bokcenter. harvard. edu/group-work [scroll to Large projects over a period of time] 10 C Back to Process Menu

When should I use semester-long groups? Semester-long groups have the potential for deeper learning and application than the other durations. However, issues of working style and personality conflict, uneven participation and contribution, need to be addressed when they arise. Groups are typically not well-equipped to deal with issues of working style, personality conflict, and uneven participation and contribution on their own. You need group work criteria, periodic group member self-and-peer process evaluation (using rubrics and other tools provided in the contract section this resource) to identify issues, and unless this is upper year level work, then the instructor needs to have tools to use to help resolve conflict (see What’s the best way to resolve group conflict? In the Process Menu). 10 D Back to Process Menu

11 A When the instructor resolves group conflict Although working through conflict on their own would be ideal, it takes more diplomatic skills than most undergraduates have developed until they have had a lot of positive university group work experience. Unless that is the case, the instructor should provide assistance. You can use the problem-solving matrix as a guide. Being proactive: Dawn Mac. Isaac of UNB Computer Science and Electrical and Computer Engineering has a student from each group complete a team assessment after each deliverable based on a group work rubric (like the one in Group work contracts) to identify group process problems. These assessments often reveal problems. She then creates some group process problem scenarios and conducts a short in-class group work exercise where the groups resolve the issue in their scenarios and report back to the class. There are two scenarios for each problem, each from opposite perspectives (e. g. , what group needs to do vs. what individual experiencing the problem needs to do). The group with the problem typically gets one of the 2 scenarios, but also hears what another group would do. She finds that this helps students find their way out of impasses. Common Problems and some solutions: • Floundering • Dominating or reluctant participants • Digressions and tangents • Getting Stuck • Rush to work • Feuds Scroll to Some Common Problems (and Some Solutions) at: https: //bokcenter. harvard. edu/group-work and https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/gr oupprojects/monitor. html • Ignoring or ridiculing others Are international students being left out? … Back to Process Menu

Ensuring international students are included From Working with International Students in Class by Belinda Young-Davy, Jennifer Rice, and Keli Yerian, AEI Faculty University of Oregon: How can I talk to both non-ELL (English Language Learners) and ELLs about the best way to work with one another? • Take a portion of Class 1 to get into small groups and do a task together that involves asking about past writing experiences, hometowns, etc. • Set up an assignment that makes the native English speakers NEED to talk with the ELLs (interview of cultural difference that leads to a paper, etc. ) • Talk up the cultural (and all kinds of) diversity as an asset to the class and formulate topics around that. 11 A 1 Back to Previous Screen Back to Process Menu

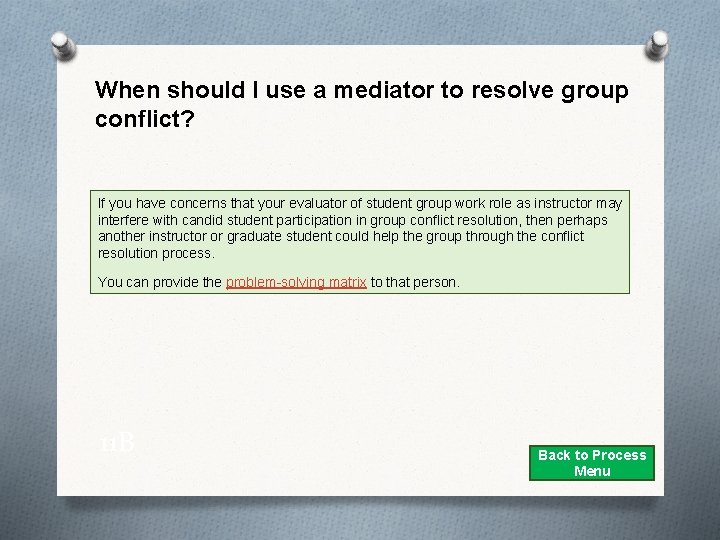

When should I use a mediator to resolve group conflict? If you have concerns that your evaluator of student group work role as instructor may interfere with candid student participation in group conflict resolution, then perhaps another instructor or graduate student could help the group through the conflict resolution process. You can provide the problem-solving matrix to that person. 11 B Back to Process Menu

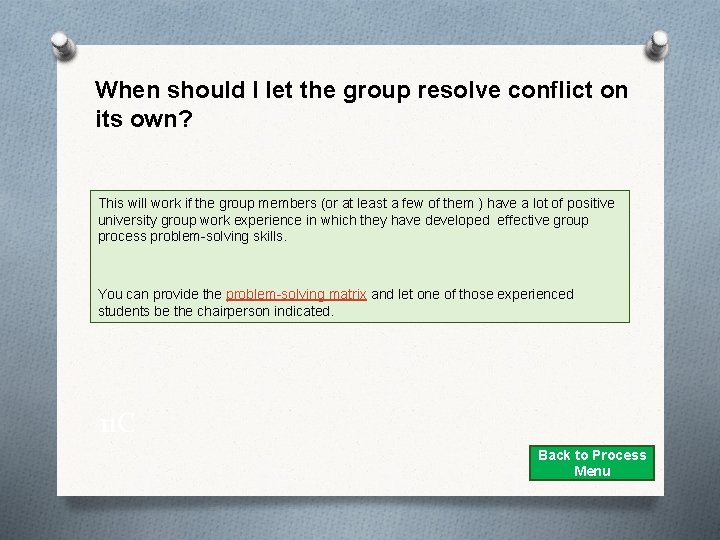

When should I let the group resolve conflict on its own? This will work if the group members (or at least a few of them ) have a lot of positive university group work experience in which they have developed effective group process problem-solving skills. You can provide the problem-solving matrix and let one of those experienced students be the chairperson indicated. 11 C Back to Process Menu

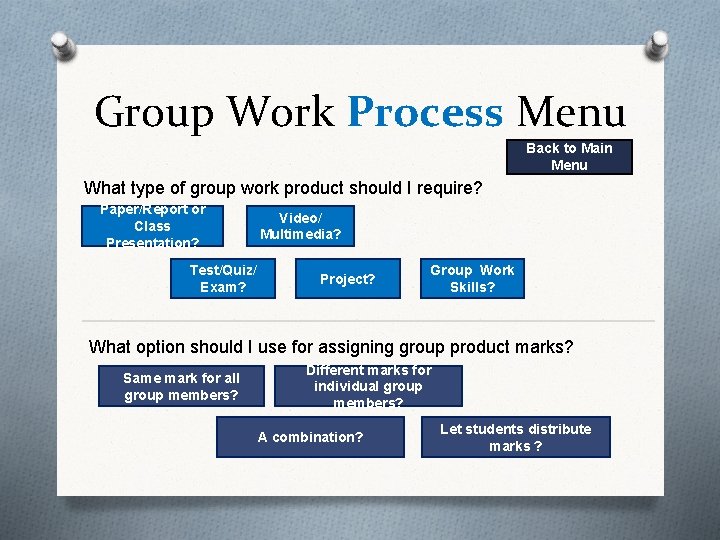

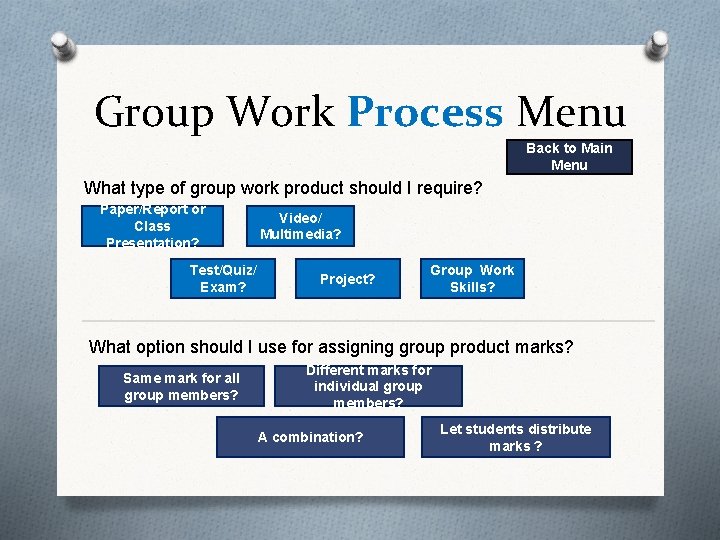

Group Work Process Menu Back to Main Menu What type of group work product should I require? Paper/Report or Class Presentation? Test/Quiz/ Exam? Video/ Multimedia? Project? Group Work Skills? What option should I use for assigning group product marks? Same mark for all group members? Different marks for individual group members? A combination? Let students distribute marks ?

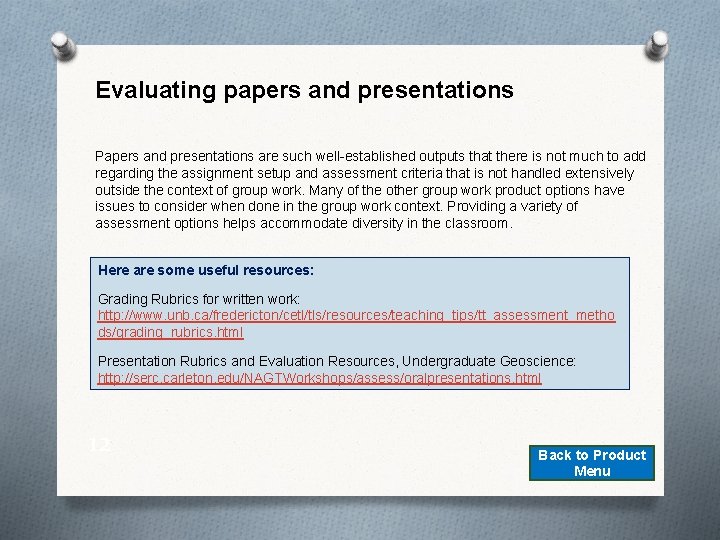

Evaluating papers and presentations Papers and presentations are such well-established outputs that there is not much to add regarding the assignment setup and assessment criteria that is not handled extensively outside the context of group work. Many of the other group work product options have issues to consider when done in the group work context. Providing a variety of assessment options helps accommodate diversity in the classroom. Here are some useful resources: Grading Rubrics for written work: http: //www. unb. ca/fredericton/cetl/tls/resources/teaching_tips/tt_assessment_metho ds/grading_rubrics. html Presentation Rubrics and Evaluation Resources, Undergraduate Geoscience: http: //serc. carleton. edu/NAGTWorkshops/assess/oralpresentations. html 12 Back to Product Menu

Evaluating video and multimedia products Video an multimedia productions on course topics need to maintain a good balance between content quality assessment on the one hand production quality on the other. Video or multimedia product evaluation rubric: This rubric provides instructors with observable behaviours to watch for that can help them determine video quality (so no instructor experience in video production is required), while not having video quality outweigh the content quality. Click to view rubric… 12 A Back to Product Menu

Team-based learning using quizzes and tests Some ongoing group work that uses tests to assess knowledge demonstration mix individual and group assessment in a formalized team-based learning approach developed by Dr. Larry Michaelsen, that provides easy to mark tools (i. RATs- Individual Readiness Assessment Tests and t. RATs-Team Readiness Assessment tests). Team-Based Learning (Michaelsen) (teaching course content through ongoing, termlong stable groups that work on the same problems and report back to class. Deeper learning results. ): www. epsteineducation. com/home/about/teamlearning. aspx Team-based learning video (second from top) http: //ctl. utexas. edu/teaching/engagement/teaching-large#tbl Part of this TBL technique is a mix of individual in-class testing on pre-assigned homework/readings with retaking the same test in a group, and getting a mark based on the mix of the two. Part marks are also awarded for getting the answer on the second try. What is the IF-AT (Immediate Feedback Assessment Technique): http: //www. epsteineducation. com/home/about/default. aspx How Does IF-AT work? http: //www. epsteineducation. com/home/about/how. aspx 12 B Back to Product Menu

Evaluating group projects Projects vary widely by discipline and topic area, so there is little about project setup instructions and evaluation criteria that are unique to the group work context. The next section deals with how to assign marks for projects done in a group context. Consider a group portfolio as a way to document evidence of group work product and process quality. can demonstrate the student's knowledge, understanding, skills, values and attitudes Portfolios relevant to the area of study. Students also learn from the construction of the portfolio. A portfolio should include both agreed criteria that are aligned with the requirements of the subject and examples of work that demonstrate knowledge and understanding of that criteria. For example: • report(s) • assignment(s) • meetings minutes • observational data • interview data • reflective pieces • journal entries • any evidence of the achievement of the set criteria. Other considerations for evaluating group projects… The portfolio documents individual and group contributions. 12 C Back to Product Menu

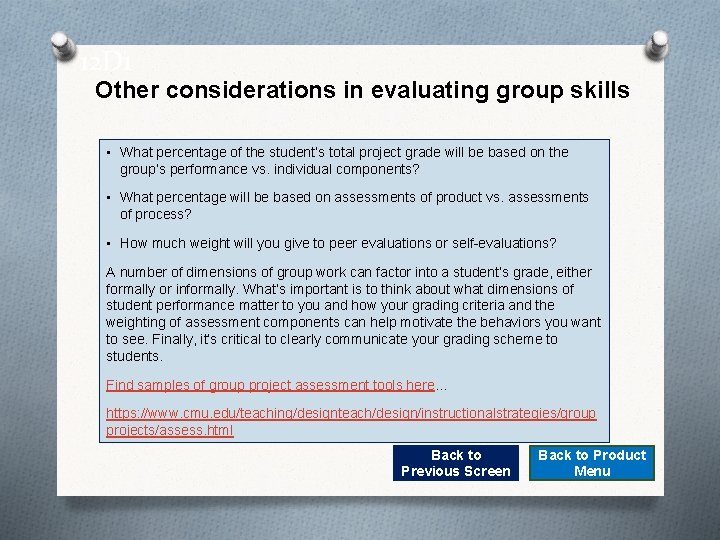

Other considerations in evaluating group projects • What percentage of the student’s total project grade will be based on the group’s performance vs. individual components? • What percentage will be based on assessments of product vs. assessments of process? • How much weight will you give to peer evaluations or self-evaluations? A number of dimensions of group work can factor, either formally or informally, into a student’s grade. What’s important is to think about what dimensions of student performance matter to you and how your grading criteria and the weighting of assessment components can help motivate the behaviors you want to see. Finally, it’s critical to clearly communicate your grading scheme to students. Find samples of group project assessment tools here. . . Other group project assessment resources: https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/group projects/assess. html Back to Product Previous Screen Menu 12 C 1

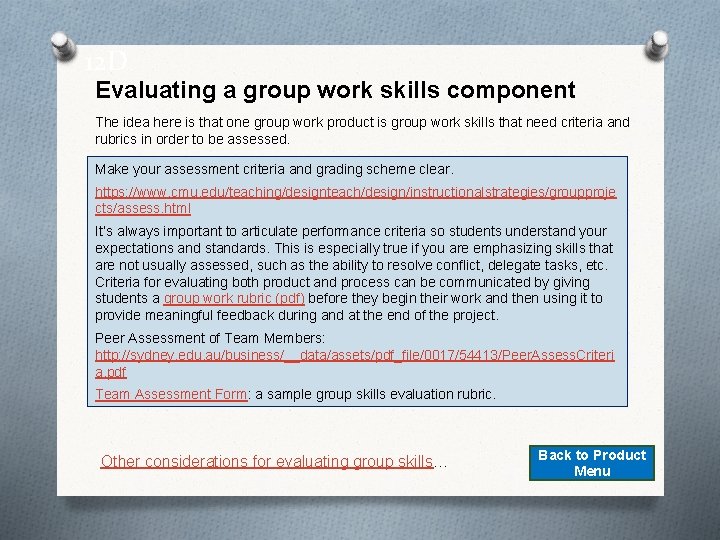

12 D Evaluating a group work skills component The idea here is that one group work product is group work skills that need criteria and rubrics in order to be assessed. Make your assessment criteria and grading scheme clear. https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/groupproje cts/assess. html It’s always important to articulate performance criteria so students understand your expectations and standards. This is especially true if you are emphasizing skills that are not usually assessed, such as the ability to resolve conflict, delegate tasks, etc. Criteria for evaluating both product and process can be communicated by giving students a group work rubric (pdf) before they begin their work and then using it to provide meaningful feedback during and at the end of the project. Peer Assessment of Team Members: http: //sydney. edu. au/business/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/54413/Peer. Assess. Criteri a. pdf Team Assessment Form: a sample group skills evaluation rubric. Other considerations for evaluating group skills… Back to Product Menu

12 D 1 Other considerations in evaluating group skills • What percentage of the student’s total project grade will be based on the group’s performance vs. individual components? • What percentage will be based on assessments of product vs. assessments of process? • How much weight will you give to peer evaluations or self-evaluations? A number of dimensions of group work can factor into a student’s grade, either formally or informally. What’s important is to think about what dimensions of student performance matter to you and how your grading criteria and the weighting of assessment components can help motivate the behaviors you want to see. Finally, it’s critical to clearly communicate your grading scheme to students. Find samples of group project assessment tools here. . . https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/group projects/assess. html Back to Previous Screen Back to Product Menu

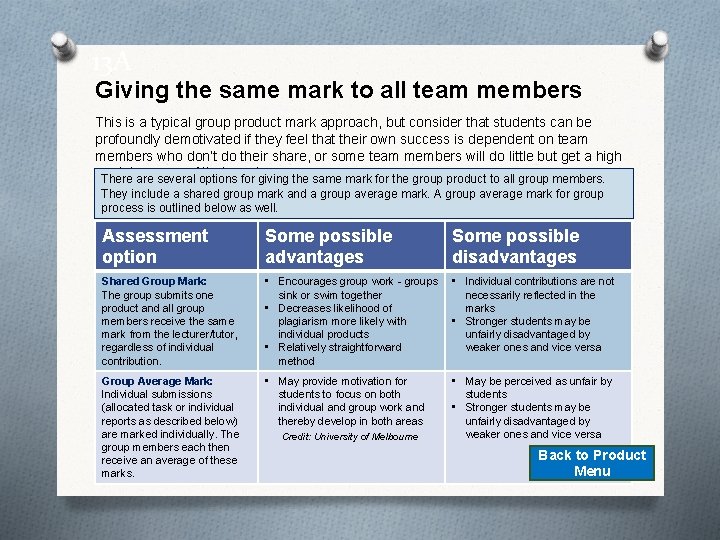

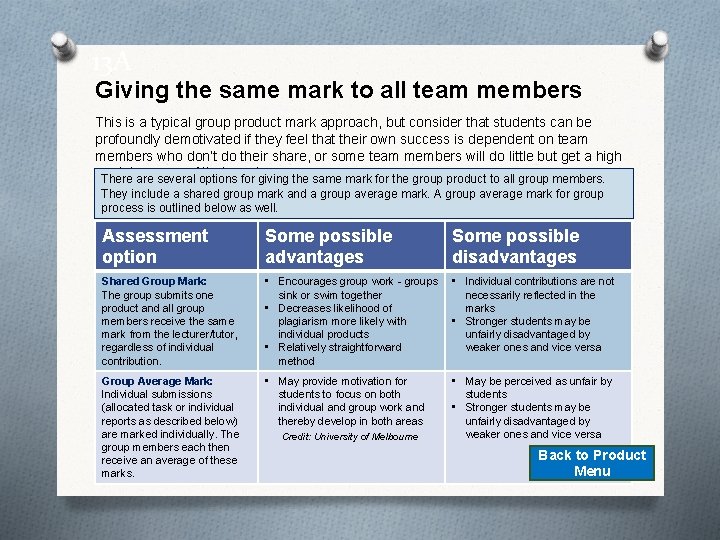

13 A Giving the same mark to all team members This is a typical group product mark approach, but consider that students can be profoundly demotivated if they feel that their own success is dependent on team members who don’t do their share, or some team members will do little but get a high mark ofoptions their work. Therebecause are several for giving the same mark for the group product to all group members. They include a shared group mark and a group average mark. A group average mark for group process is outlined below as well. Assessment option Some possible advantages Some possible disadvantages Shared Group Mark: The group submits one product and all group members receive the same mark from the lecturer/tutor, regardless of individual contribution. • Encourages group work - groups sink or swim together • Decreases likelihood of plagiarism more likely with individual products • Relatively straightforward method • Individual contributions are not necessarily reflected in the marks • Stronger students may be unfairly disadvantaged by weaker ones and vice versa Group Average Mark: • May provide motivation for Individual submissions students to focus on both (allocated task or individual and group work and reports as described below) thereby develop in both areas are marked individually. The Credit: University of Melbourne group members each then receive an average of these marks. here for third option… Click • May be perceived as unfair by students • Stronger students may be unfairly disadvantaged by weaker ones and vice versa Back to Product Menu

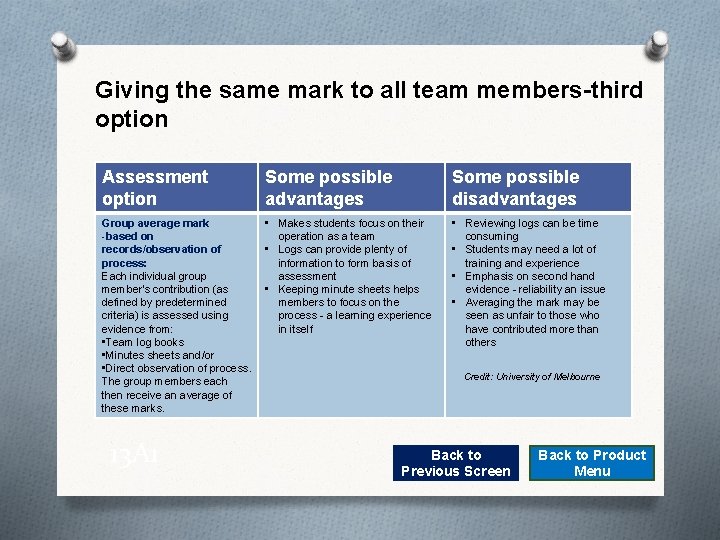

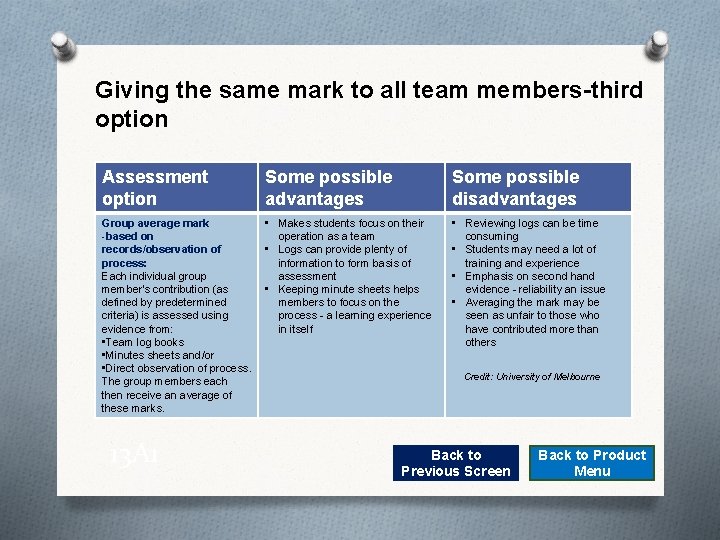

Giving the same mark to all team members-third option Assessment option Some possible advantages Some possible disadvantages Group average mark -based on records/observation of process: Each individual group member's contribution (as defined by predetermined criteria) is assessed using evidence from: • Team log books • Minutes sheets and/or • Direct observation of process. The group members each then receive an average of these marks. • Makes students focus on their operation as a team • Logs can provide plenty of information to form basis of assessment • Keeping minute sheets helps members to focus on the process - a learning experience in itself • Reviewing logs can be time consuming • Students may need a lot of training and experience • Emphasis on second hand evidence - reliability an issue • Averaging the mark may be seen as unfair to those who have contributed more than others 13 A 1 Credit: University of Melbourne Back to Previous Screen Back to Product Menu

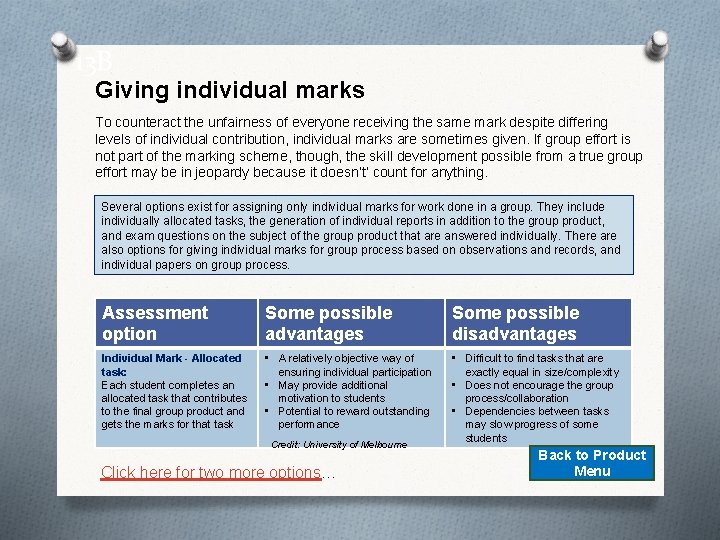

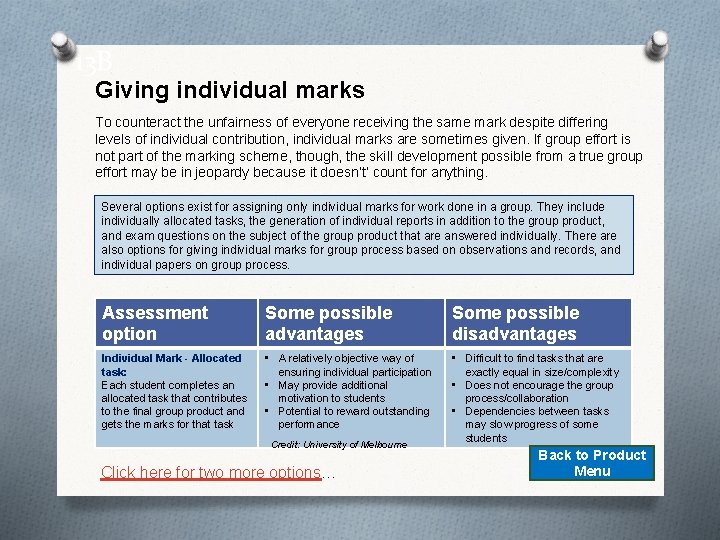

13 B Giving individual marks To counteract the unfairness of everyone receiving the same mark despite differing levels of individual contribution, individual marks are sometimes given. If group effort is not part of the marking scheme, though, the skill development possible from a true group effort may be in jeopardy because it doesn’t’ count for anything. Several options exist for assigning only individual marks for work done in a group. They include individually allocated tasks, the generation of individual reports in addition to the group product, and exam questions on the subject of the group product that are answered individually. There also options for giving individual marks for group process based on observations and records, and individual papers on group process. Assessment option Some possible advantages Some possible disadvantages Individual Mark - Allocated task: Each student completes an allocated task that contributes to the final group product and gets the marks for that task • A relatively objective way of ensuring individual participation • May provide additional motivation to students • Potential to reward outstanding performance • Difficult to find tasks that are exactly equal in size/complexity • Does not encourage the group process/collaboration • Dependencies between tasks may slow progress of some students Credit: University of Melbourne Click here for two more options… Back to Product Menu

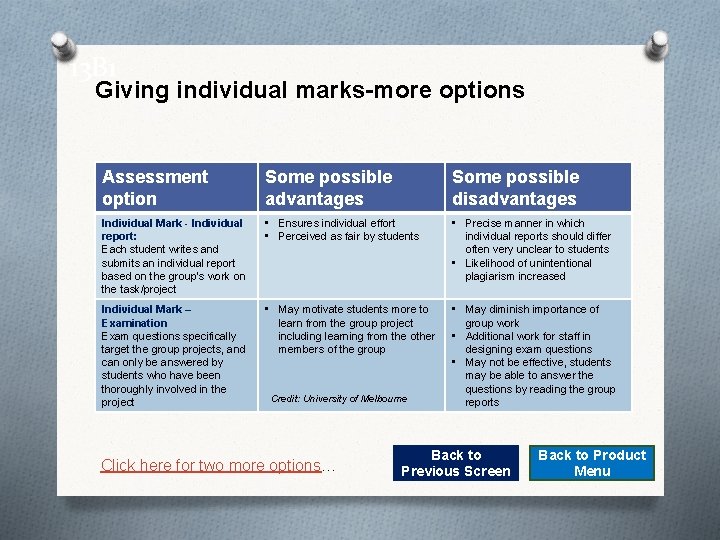

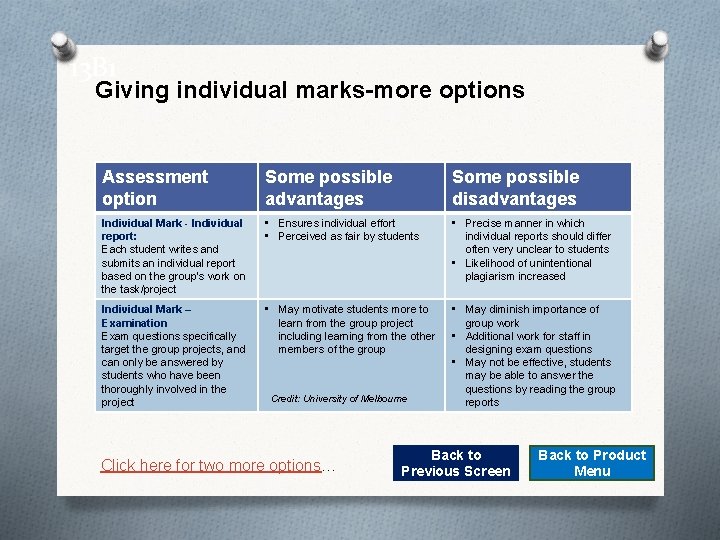

13 B 1 Giving individual marks-more options Assessment option Some possible advantages Some possible disadvantages Individual Mark - Individual report: Each student writes and submits an individual report based on the group's work on the task/project • Ensures individual effort • Perceived as fair by students • Precise manner in which individual reports should differ often very unclear to students • Likelihood of unintentional plagiarism increased Individual Mark – Examination Exam questions specifically target the group projects, and can only be answered by students who have been thoroughly involved in the project • May motivate students more to learn from the group project including learning from the other members of the group • May diminish importance of group work • Additional work for staff in designing exam questions • May not be effective, students may be able to answer the questions by reading the group reports Credit: University of Melbourne Click here for two more options… Back to Previous Screen Back to Product Menu

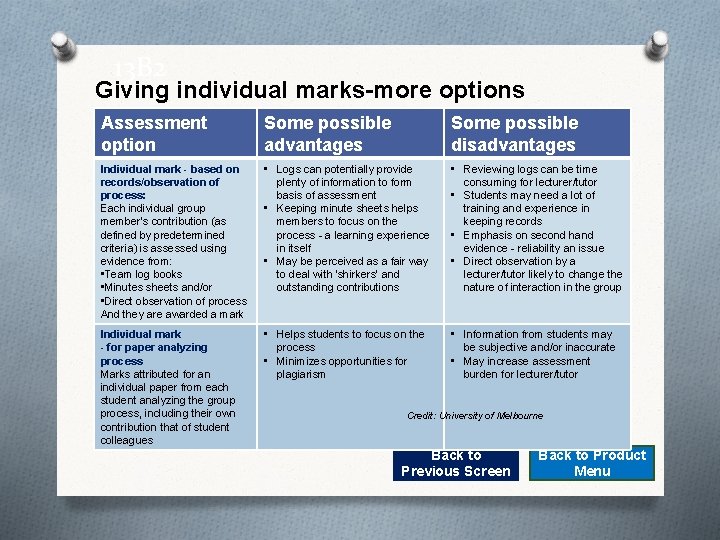

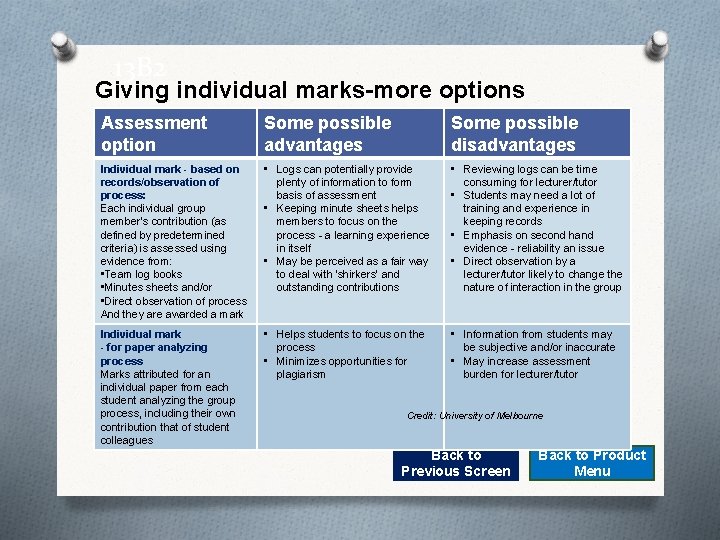

13 B 2 Giving individual marks-more options Assessment option Some possible advantages Some possible disadvantages Individual mark - based on records/observation of process: Each individual group member's contribution (as defined by predetermined criteria) is assessed using evidence from: • Team log books • Minutes sheets and/or • Direct observation of process And they are awarded a mark • Logs can potentially provide plenty of information to form basis of assessment • Keeping minute sheets helps members to focus on the process - a learning experience in itself • May be perceived as a fair way to deal with 'shirkers' and outstanding contributions • Reviewing logs can be time consuming for lecturer/tutor • Students may need a lot of training and experience in keeping records • Emphasis on second hand evidence - reliability an issue • Direct observation by a lecturer/tutor likely to change the nature of interaction in the group Individual mark - for paper analyzing process Marks attributed for an individual paper from each student analyzing the group process, including their own contribution that of student colleagues • Helps students to focus on the process • Minimizes opportunities for plagiarism • Information from students may be subjective and/or inaccurate • May increase assessment burden for lecturer/tutor Credit: University of Melbourne Back to Previous Screen Back to Product Menu

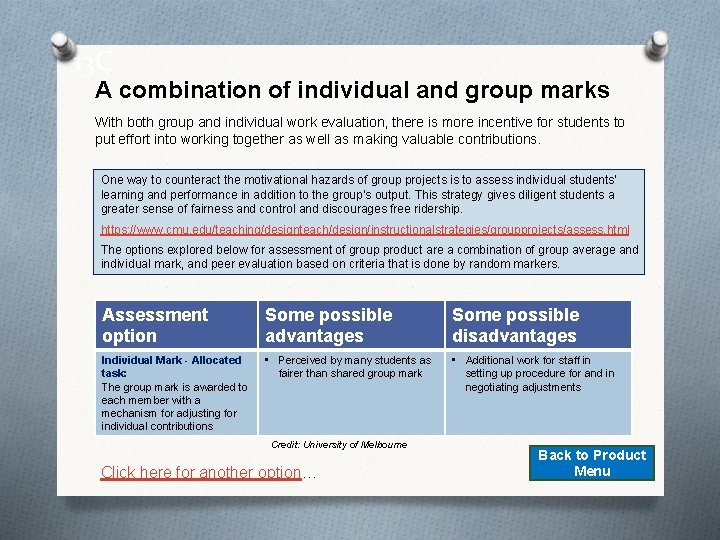

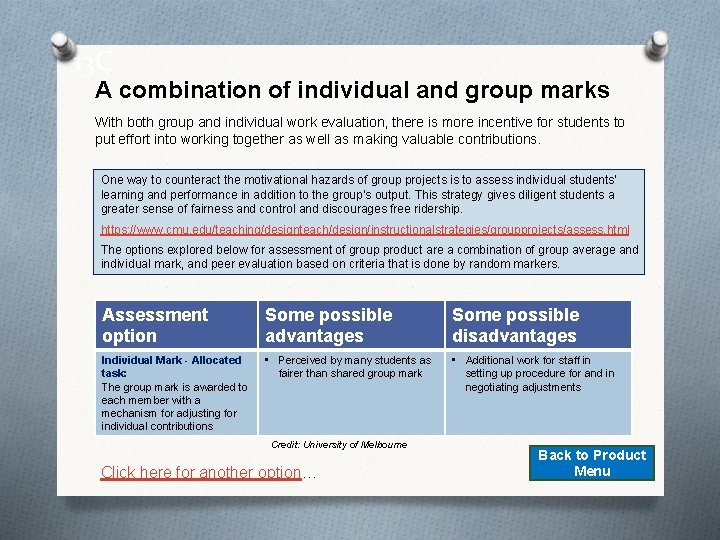

13 C A combination of individual and group marks With both group and individual work evaluation, there is more incentive for students to put effort into working together as well as making valuable contributions. One way to counteract the motivational hazards of group projects is to assess individual students’ learning and performance in addition to the group’s output. This strategy gives diligent students a greater sense of fairness and control and discourages free ridership. https: //www. cmu. edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/groupprojects/assess. html The options explored below for assessment of group product are a combination of group average and individual mark, and peer evaluation based on criteria that is done by random markers. Assessment option Some possible advantages Some possible disadvantages Individual Mark - Allocated task: The group mark is awarded to each member with a mechanism for adjusting for individual contributions • Perceived by many students as fairer than shared group mark • Additional work for staff in setting up procedure for and in negotiating adjustments Credit: University of Melbourne Click here for another option… Back to Product Menu

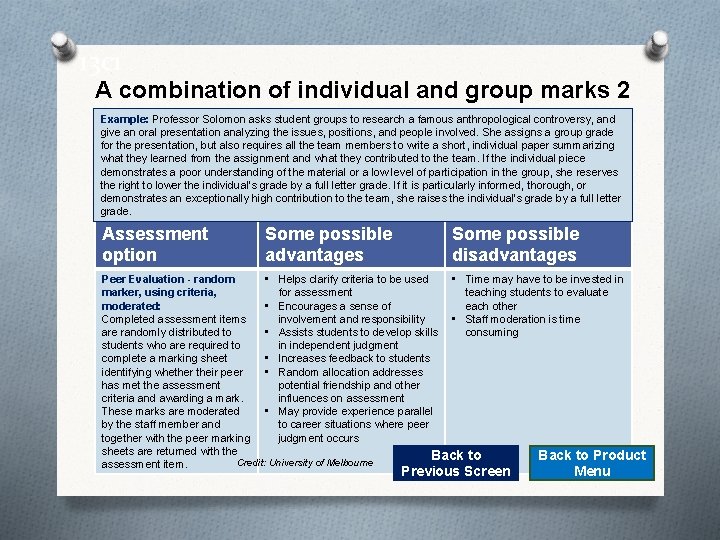

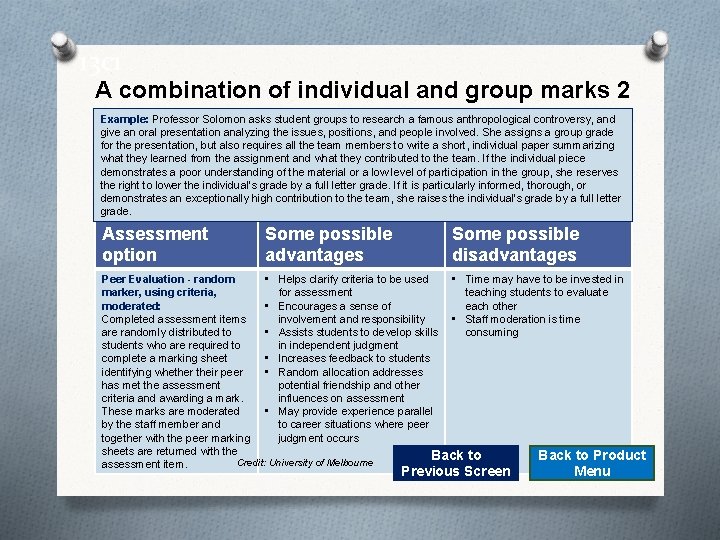

13 c 1 A combination of individual and group marks 2 Example: Professor Solomon asks student groups to research a famous anthropological controversy, and give an oral presentation analyzing the issues, positions, and people involved. She assigns a group grade for the presentation, but also requires all the team members to write a short, individual paper summarizing what they learned from the assignment and what they contributed to the team. If the individual piece demonstrates a poor understanding of the material or a low level of participation in the group, she reserves the right to lower the individual’s grade by a full letter grade. If it is particularly informed, thorough, or demonstrates an exceptionally high contribution to the team, she raises the individual’s grade by a full letter grade. Assessment option Some possible advantages Some possible disadvantages Peer Evaluation - random • Helps clarify criteria to be used • Time may have to be invested in marker, using criteria, for assessment teaching students to evaluate moderated: • Encourages a sense of each other Completed assessment items involvement and responsibility • Staff moderation is time are randomly distributed to • Assists students to develop skills consuming students who are required to in independent judgment complete a marking sheet • Increases feedback to students identifying whether their peer • Random allocation addresses has met the assessment potential friendship and other criteria and awarding a mark. influences on assessment These marks are moderated • May provide experience parallel by the staff member and to career situations where peer together with the peer marking judgment occurs sheets are returned with the Back to Product Credit: University of Melbourne assessment item. Previous Screen Menu

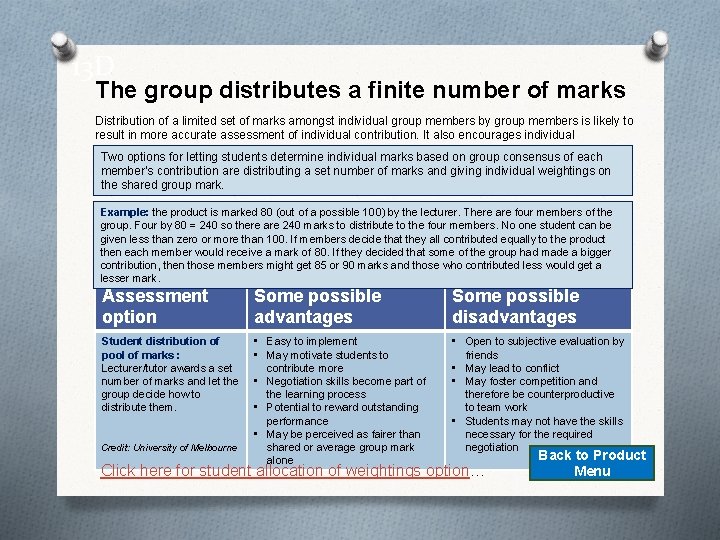

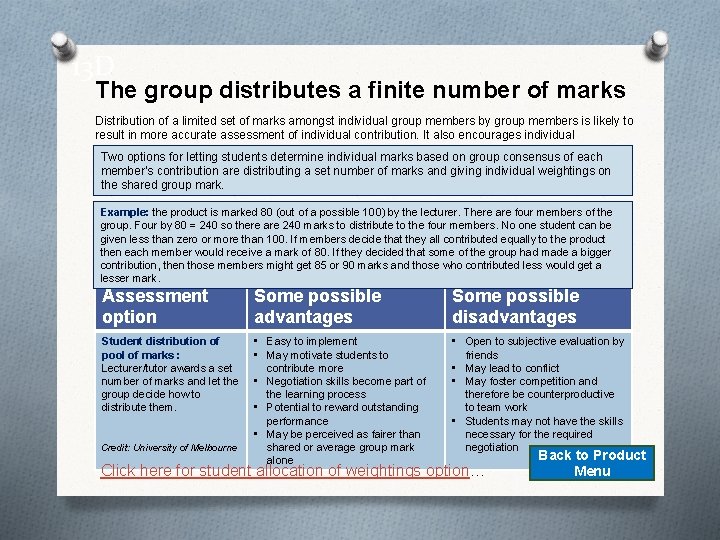

13 D The group distributes a finite number of marks Distribution of a limited set of marks amongst individual group members by group members is likely to result in more accurate assessment of individual contribution. It also encourages individual accountability. Two options for letting students determine individual marks based on group consensus of each member’s contribution are distributing a set number of marks and giving individual weightings on the shared group mark. Example: the product is marked 80 (out of a possible 100) by the lecturer. There are four members of the group. Four by 80 = 240 so there are 240 marks to distribute to the four members. No one student can be given less than zero or more than 100. If members decide that they all contributed equally to the product then each member would receive a mark of 80. If they decided that some of the group had made a bigger contribution, then those members might get 85 or 90 marks and those who contributed less would get a lesser mark. Assessment option Some possible advantages Some possible disadvantages Student distribution of pool of marks : Lecturer/tutor awards a set number of marks and let the group decide how to distribute them. • Easy to implement • May motivate students to contribute more • Negotiation skills become part of the learning process • Potential to reward outstanding performance • May be perceived as fairer than shared or average group mark alone • Open to subjective evaluation by friends • May lead to conflict • May foster competition and therefore be counterproductive to team work • Students may not have the skills necessary for the required negotiation Credit: University of Melbourne Click here for student allocation of weightings option… Back to Product Menu

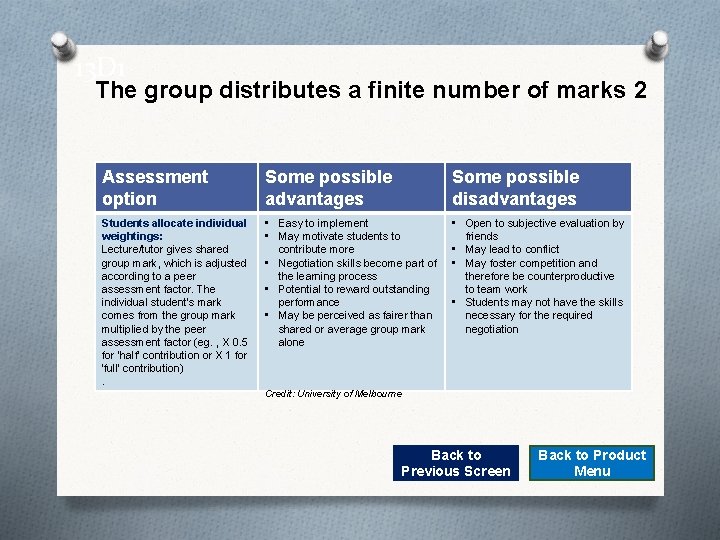

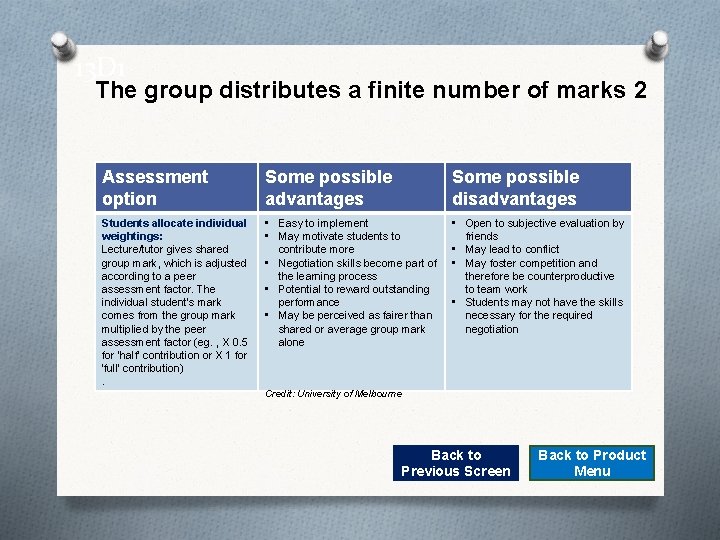

13 D 1 The group distributes a finite number of marks 2 Assessment option Some possible advantages Some possible disadvantages Students allocate individual weightings: Lecture/tutor gives shared group mark, which is adjusted according to a peer assessment factor. The individual student's mark comes from the group mark multiplied by the peer assessment factor (eg. , X 0. 5 for 'half' contribution or X 1 for 'full' contribution). • Easy to implement • May motivate students to contribute more • Negotiation skills become part of the learning process • Potential to reward outstanding performance • May be perceived as fairer than shared or average group mark alone • Open to subjective evaluation by friends • May lead to conflict • May foster competition and therefore be counterproductive to team work • Students may not have the skills necessary for the required negotiation Credit: University of Melbourne Back to Previous Screen Back to Product Menu

References Back to Main Menu O Carroll, J. (2009). Teaching Culturally Diverse Groups: managing assessed group work. Economics Network. Retrieved from http: //www. economicsnetwork. ac. uk/showcase/carroll_diversity O Geoff Petty Research and Links: http: //geoffpetty. com/for-team-leaders/research-and-links/ O Hattie, J. (1999). Influences on Student Learning. University of Auckland. Retrieved from http: //xn--www-rp 0 a. teacherstoolbox. co. uk/downloads/managers/Influencesonstudent. pdf O Leask, B. (2009). Using formal and Informal Curricula to Improve Interactions Between Home and International Students. Journal of Studies in International Education, 13(2). O Medved, D. et al. (2013). Challenges in teaching international students: group separation, language barriers and culture differences. Retrieved from: https: //lup. lub. lu. se/search/publication/4215983 O Mixing, learning and working together. (Undated). The Higher Education Academy, York, UK. O Neville, C. Making Groupwork Work. The Learnhigher CETL at the University of Bradford, UK. O Presentation Rubrics and Evaluation Resources, Undergraduate Geoscience: http: //serc. carleton. edu/NAGTWorkshops/assess/oralpresentations. html O UNB Teaching and Learning Services. Group Work. http: //www. unb. ca/fredericton/cetl/tls/resources/teaching_tips/tt_instructional_methods/group_ work. html O Young-Davy, B. et. at. (2013). Working with International Students in Class. American English Institute, College of Arts and Sciences Teaching Effectiveness Program. This resource designed and developed by Bev Bramble, UNB CETL-Teaching and Learning Services bbramble@unb. ca