Machine Learning meets the Real World Successes and

- Slides: 44

Machine Learning meets the Real World: Successes and new research directions Andrea Pohoreckyj Danyluk Department of Computer Science Williams College, Williamstown, MA October 11, 2002

Data, data everywhere. . . • Scientific: data collection routinely produces gigabytes of data per day • Telecommunications: AT&T produces 275 million call records • Web: Google handles 70 million searches • Retail: Wal. Mart records 20 million sales transactions

A wealth of information • Scientific data – Detection of oil spills from satellite images – Prediction of molecular bioactivity for drug design • Telecommunications – Fraud detection to distinguish between “bad” and normal usage of cell phones

A wealth of information • Web mining – Characterize killer pages • Retail – Determine better product placement • Direct mail – Predict who is most likely to donate to a charity

Machine learning success (Machine learning is ubiquitous) • Scientific discovery – Detection of oil spills from satellite images • Telecommunications – Diagnosis of problems in the local loop • Printing – Determine causes of banding (printing cylinder problems) • Control – Self-steering vehicles

Why research in machine learning is so good today Research in machine learning benefits from • Abundant data • Interest in fielding new applications – Even more data – Push on limits of our understanding, technology, etc.

Plan for this talk Original • Discuss success stories and failures • Failures help identify new areas of research New plan • One success story in detail • Lesson learned: can identify new areas of research even when we succeed

Induction of decision trees • Not the only (or even the most “hot”) algorithms • Have been used in many contexts • Important for understanding our success story: local-loop network diagnosis

Inductive learning Given a collection of observations of the form (<x>, f<x>) Find g<x> that approximates f<x>

Sample data

Predictive model I. e. , g<x>

Learning objectives • Learn a tree that is correct • Learn a tree that is compact • At every level in the tree, select a test that best differentiates examples of one class from another

TDIDT • If all examples are from the same class – The tree is a leaf with that class name • Else – Pick a test to make – Construct one edge for each possible test outcome – Partition the examples by test outcome – Build subtrees recursively

Which is better?

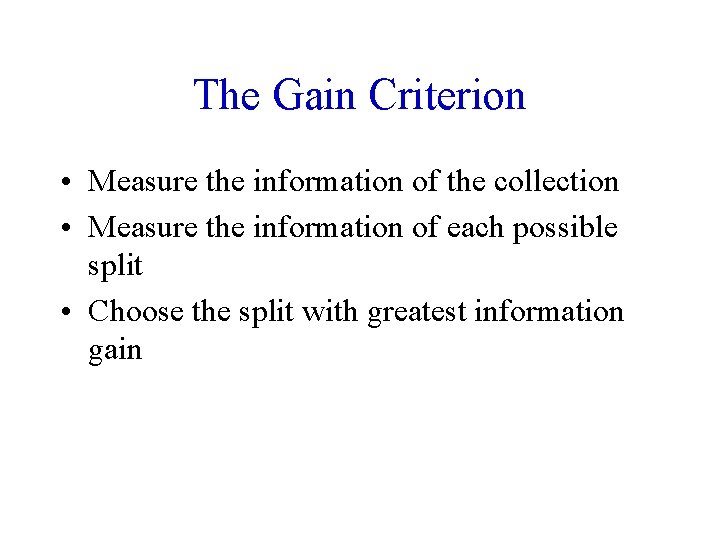

The Gain Criterion • Measure the information of the collection • Measure the information of each possible split • Choose the split with greatest information gain

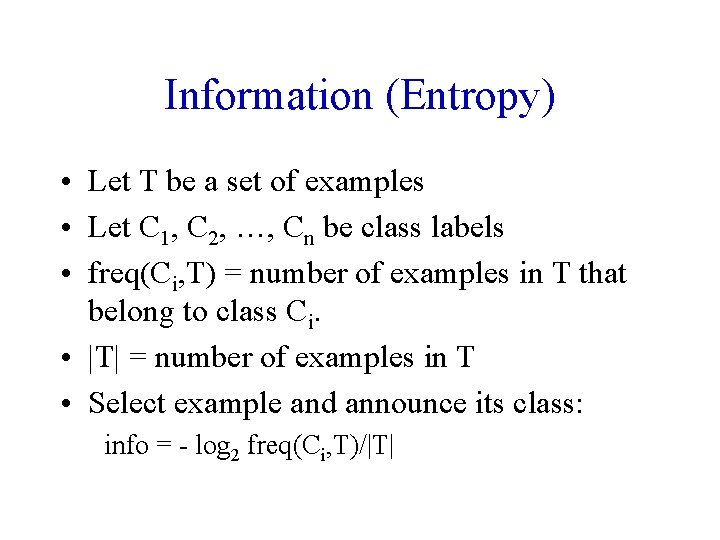

Information (Entropy) • Let T be a set of examples • Let C 1, C 2, …, Cn be class labels • freq(Ci, T) = number of examples in T that belong to class Ci. • |T| = number of examples in T • Select example and announce its class: info = - log 2 freq(Ci, T)/|T|

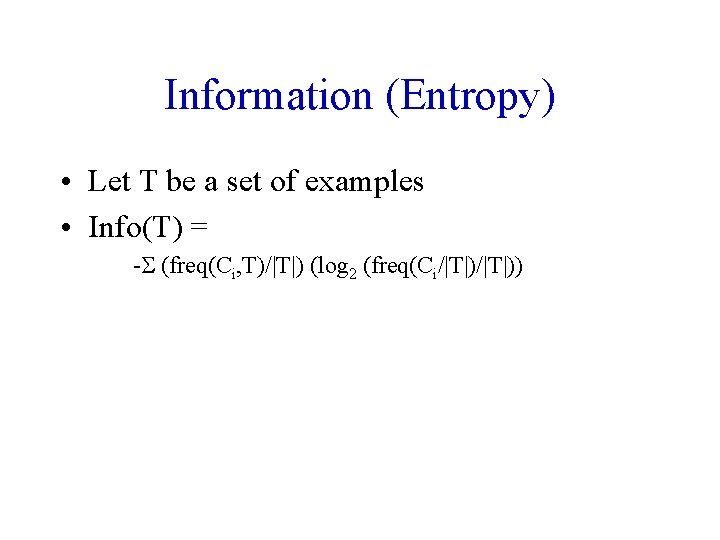

Information (Entropy) • Let T be a set of examples • Info(T) = - (freq(Ci, T)/|T|) (log 2 (freq(Ci/|T|))

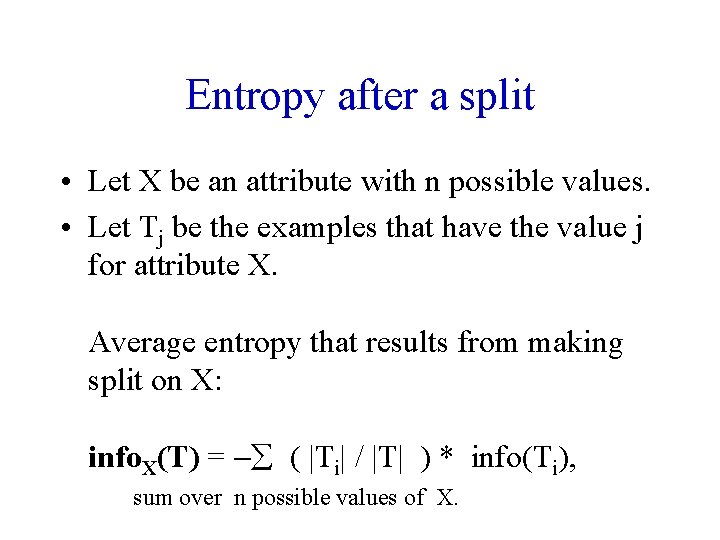

Entropy after a split • Let X be an attribute with n possible values. • Let Tj be the examples that have the value j for attribute X. Average entropy that results from making split on X: info. X(T) = ( |Ti| / |T| ) * info(Ti), sum over n possible values of X.

Information Gain • Compute info. X(T) for every attribute • Select attribute that maximizes info(T) – info. X(T)

Which is better?

Scrubber (the success story) • Diagnoses problems in the local loop • Problem may be due to trouble in: – Customer premise equipment – Facilities connecting customer to cable – Central office • Millions of “troubles” reported annually

MAX, 1990 • Acts as Maintenance Administrator (MA) • Sequence of action: – Customer calls – Rep takes information; initiates tests – Trouble report sent to MA – MA puts trouble in dispatch queue for specific type of technician

Scrubber 2 • Performed a task at a later point in the pipeline • Survey dispatch queues to determine whether dispatch appropriate – Dispatch not immediate – Many problems resolved exogenously

Scrubber 3 • Scrubber 2 for new application platform • Centralized knowledge server • Cover twice as large a network

Implementation difficulties • Original expert system shell no longer supported • Knowledge base evolved into opacity – Many tweaks over a decade – Many knowledge engineers – Most not available to work on Scrubber 3

Requirements • Level of performance at least as good as prior system – Overall accuracy – False positives and false negatives in range • Comprehensible – For understanding and acceptance by experts

Additional requirements (ours) • Improved performance • Improved extensibility

Phase I: Modeling Scrubber 2 • Applied a decision tree learning algorithm • Input data: – Trouble reports – Scrubber 2 diagnoses

Data 26, 000 trouble reports • 40 attributes (1/2 continuous; 1/2 symbolic) • Two classes – Dispatch – Don’t -- I. e. , call customer to verify ok

Background knowledge • C 4. 5 selected • 17 of 40 attributes used

Phase I results • Decision trees with predictive accuracy of. 99, with as few as 10, 000 examples • Less than two days of work (easy!)

Phase II: Acceptance • Comprehensibility Readability – Need to observe rationality in learned knwoledge – Original trees on order of 1000 nodes • The simpler the model, the better it can be understood Comprehensibility = Readability + Simplicity + Fidelity

Trading off simplicity and correctness • Pruning nodes sacrifices correctness • Appropriate when comprehensibility an issue • Langley and Schwabacher, 2001 • Note: not pruning to avoid overfitting

Phase II results • Used only two most prominent attributes • New decision trees created • Still fell into acceptable zone

Phase III: Working toward extensibility • Hoped to gain flexibility for – Local modifiability – Additional attribute values • Moved toward probabilistic decision tree – Leaves labeled with probability estimates, not decisions – Stubby trees easy to represent in tabular form

Phase IIIb: More data • Focus on two attributes gave us access to an extensive data set – Many more trouble reports – Abridged (two-attribute) form had not been considered useful earlier

Phase III results • Simple diagnostic model • Greater empirical confidence -- impt due to small disjunct problem – “Big” general rules cover approximately 50% of the data – Remaining 50% covered by small disjuncts

Summarizing the success story • C 4. 5 applied to induce Scrubber 2 model • Pruned model for comprehensibility/simplicity • Converted new model into probabilistic one • Used newly gained data for additional tuning and confidence • Small(? ), simple model in very short time

Lessons can be learned from success Lesson 1: the importance of comprehensibility – Rationality – Readability – Simplicity

Lessons can be learned from success Lesson 2: the need for algorithms to handle small data sets – Creative ways to engineer interesting features from few – Openness to alternative sources of data – Algorithms specifically tuned to handle small data sets Langley has noted this to be an issue of scientific data -- but true for industrial data as well

Lessons can be learned from success Lesson 3: the need to think about systematic error – Locally systematic error only look like noise with enough data – Clearly related to the problem of small data sets – How do our algorithms hold up?

Lessons can be learned from success Lesson 4: the need to think about the future – Learning results put into practice will be modifed and extended – Must new models be learned? – Can improvement be incremental?

Lessons can be learned from success Lesson 5: creative uses of the technology – Learning for the purposes of re-engineering isn’t “standard” – New applications will serve to fuel new research

Further reading and acknowledgements • Carla Brodley et al, American Scientist, Jan. /Feb. ‘ 99 • Pat Langley, various publications • Thanks to Foster Provost and many others at Nynex / Bell Atlantic