Lynch syndrome Economic evaluations Tristan Snowsill Test Club

Lynch syndrome – Economic evaluations Tristan Snowsill Test Club 5 th December 2017

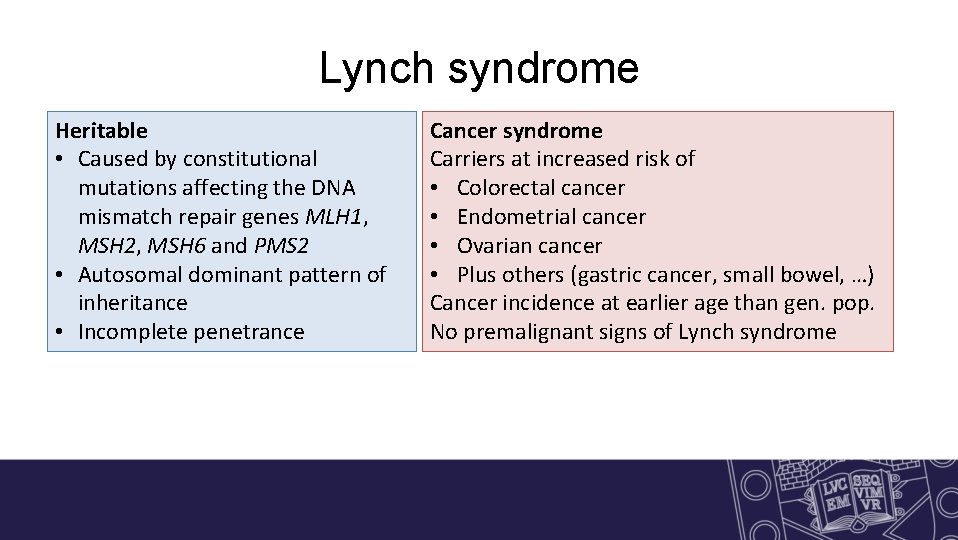

Lynch syndrome Heritable • Caused by constitutional mutations affecting the DNA mismatch repair genes MLH 1, MSH 2, MSH 6 and PMS 2 • Autosomal dominant pattern of Heritable inheritance • Incomplete penetrance Cancer syndrome Carriers at increased risk of • Colorectal cancer • Endometrial cancer • Ovarian cancer • Plus others (gastric cancer, small bowel, …) cancer syndrome Cancer incidence at earlier age than gen. pop. No premalignant signs of Lynch syndrome

Lynch syndrome • Population prevalence (≈ incidence at birth) – Around 1 in 400 • Estimated to cause ≈ 3% of colorectal cancer and endometrial cancer • Disproportionately responsible for early-onset cancer (up to 8%) • Cancer survival tends to be somewhat better than sporadic cancer

Interventions • Surveillance • Risk-reducing surgery • Chemoprevention

Diagnosis (affected by CRC/EC) • Limited use – Clinical and pathological features – Family history • Suggestive, but not diagnostic – Microsatellite instability (MSI) testing – MMR immunohistochemistry (IHC) • Excluding likely sporadic cases – MLH 1 methylation testing – BRAF V 600 E mutation testing (CRC only)

Diagnosis (affected by CRC/EC) • Diagnosis through identification of pathogenic constitutional mutation in or affecting MMR genes – Sequencing for short mutations – MLPA for genomic mutations (deletion, inversion, repetition of exons) – Interpretation can be challenging

Predictive testing • When a Lynch syndrome mutation is known in the family, can test blood relatives for mutation – Very accurate – Not very expensive • Usually use cascade testing

Genetic counselling • Usually individuals are referred for genetic counselling prior to mutation testing • Helps them to understand – What is being tested for – What the risks are – What options are available • Counselling also recommended following testing • But some suggest substantial streamlining

(How) should we try to identify people with Lynch syndrome? Two broad routes to diagnosis in a previously unidentified family • Referred after being affected by cancer (possibly reflex) • Referred due to strong family history of cancer Population screening (with or without risk assessment) unlikely to be cost-effective compared to reflex or opportunistic testing

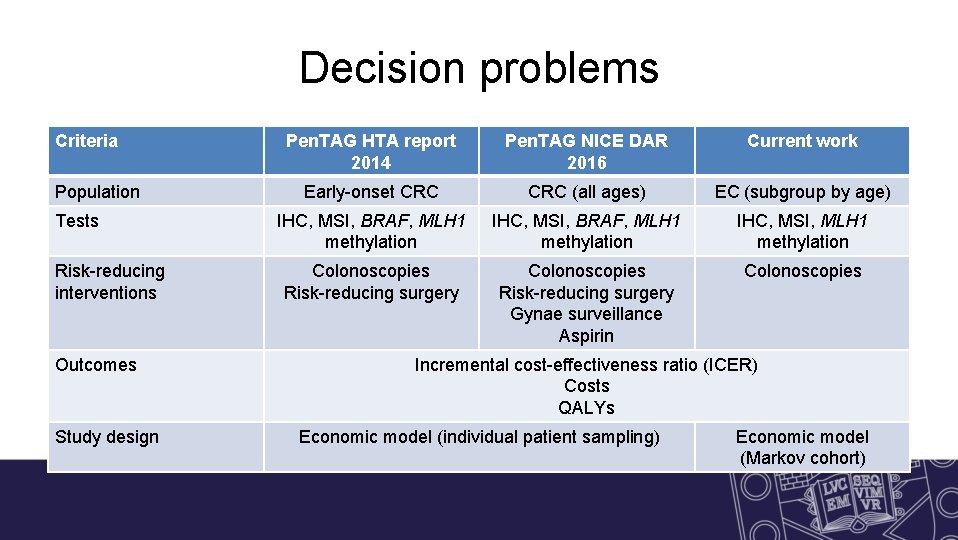

Decision problems Criteria Population Tests Risk-reducing interventions Outcomes Study design Pen. TAG HTA report 2014 Pen. TAG NICE DAR 2016 Current work Early-onset CRC (all ages) EC (subgroup by age) IHC, MSI, BRAF, MLH 1 methylation IHC, MSI, MLH 1 methylation Colonoscopies Risk-reducing surgery Gynae surveillance Aspirin Colonoscopies Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) Costs QALYs Economic model (individual patient sampling) Economic model (Markov cohort)

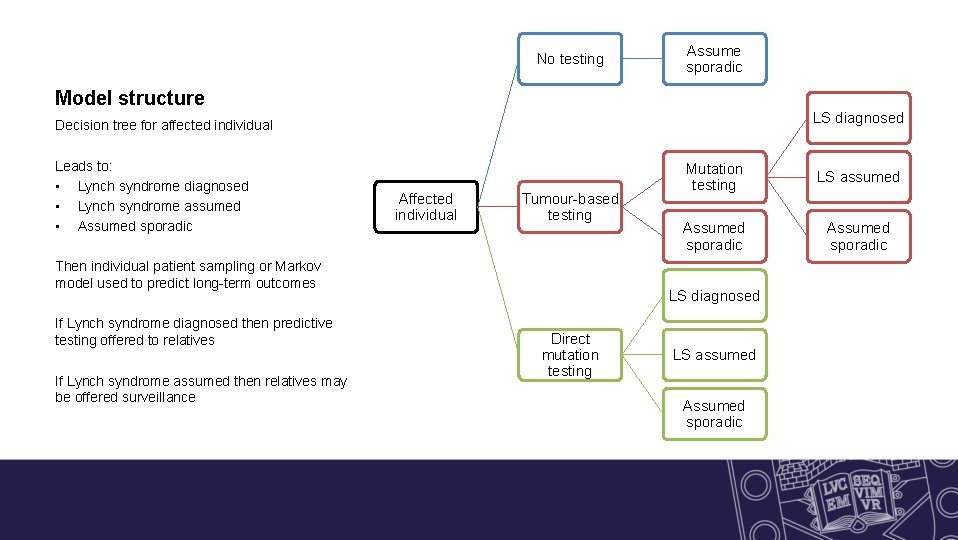

No testing Assume sporadic Model structure LS diagnosed Decision tree for affected individual Leads to: • Lynch syndrome diagnosed • Lynch syndrome assumed • Assumed sporadic Affected individual Tumour-based testing Then individual patient sampling or Markov model used to predict long-term outcomes If Lynch syndrome diagnosed then predictive testing offered to relatives If Lynch syndrome assumed then relatives may be offered surveillance Mutation testing LS assumed Assumed sporadic LS diagnosed Direct mutation testing LS assumed Assumed sporadic

Summary of findings • Pen. TAG HTA report 2014 – Life expectancy for those with Lynch syndrome improved by over 1 year – Increased use of colonoscopies – Decreased CRC incidence and mortality – All testing strategies cost-effective versus no testing – In fully incremental analysis MSI with BRAF was cost-effective – Increasing age threshold worsens cost-effectiveness

Summary of findings • Pen. TAG NICE DAR 2016 – Testing still cost-effective versus no testing (except for direct mutation testing) – Cost-effective strategy is IHC plus BRAF and MLH 1 methylation testing

Current work • Cost-effectiveness of different testing strategies to identify Lynch syndrome in women with endometrial cancer – Pragmatic literature reviews for model parameters – Sophisticated(? ) meta-analyses and parametric model fitting – Decision tree and Markov model – Extensive exploration of uncertainty

Tests with more than two outcomes Microsatellite instability testing MMR immunohistochemistry • Typically use panel of 5 markers • 0 affected Microsatellite stable (MSS) • 1 affected Low microsatellite instability (MSI-L) • 2 -5 affected High microsatellite instability (MSI-H) • Panel of four antibodies for MMR proteins • Absent/weak/abnormal staining suggests deficiency in MMR system • BUT MSH 6/PMS 2 proteins break down if they cannot dimerize with MSH 2/MLH 1 • Intention to diagnose?

Intention to diagnose If individual has following pattern of IHC staining: • MLH 1 absent • MSH 2, MSH 6 and PMS 2 present Is it a true positive result if the individual actually has an MSH 2 mutation? What are the likely downstream tests?

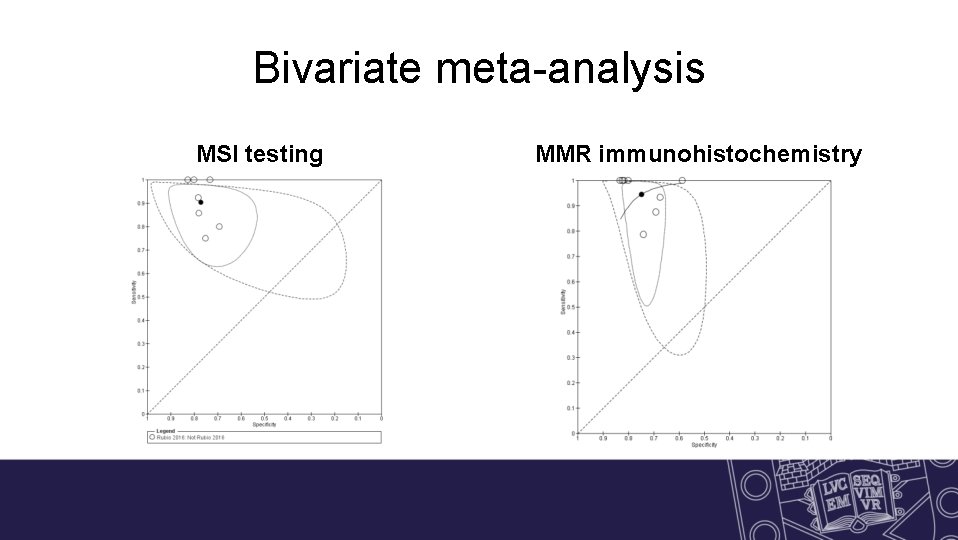

Bivariate meta-analysis MSI testing MMR immunohistochemistry

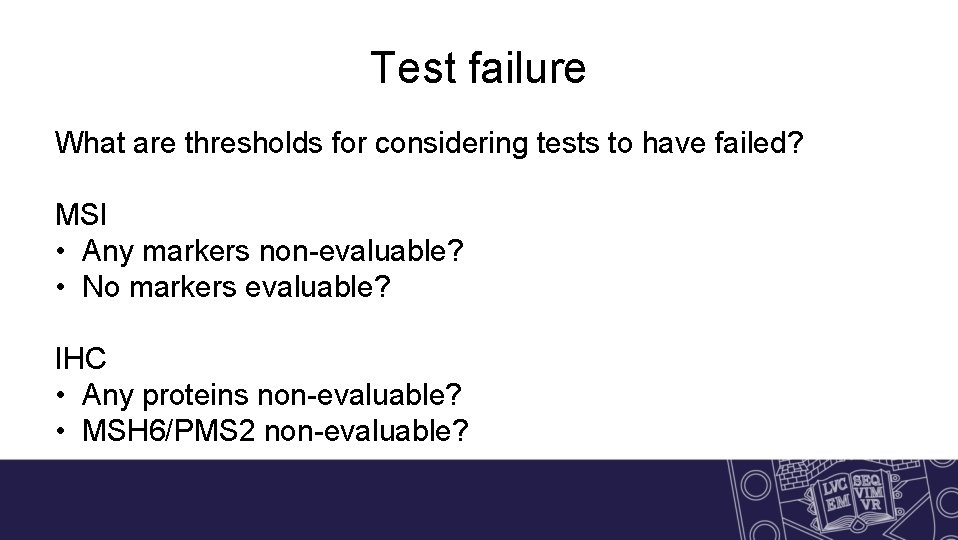

Test failure What are thresholds for considering tests to have failed? MSI • Any markers non-evaluable? • No markers evaluable? IHC • Any proteins non-evaluable? • MSH 6/PMS 2 non-evaluable?

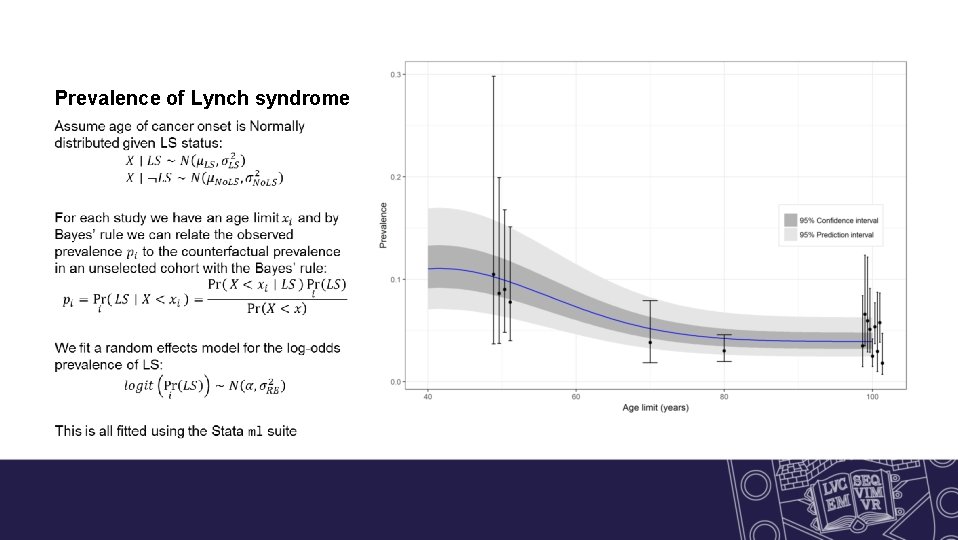

Prevalence of Lynch syndrome

Gene distribution of LS in EC patients Variation due to random chance or heterogeneity across studies?

Incidence of colorectal cancer (fitting)

Cumulative risk of colorectal cancer

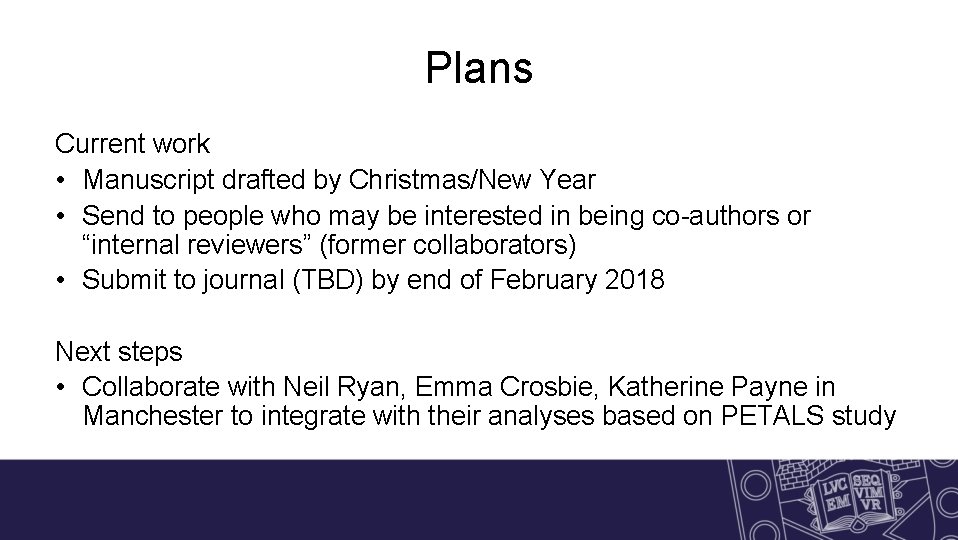

Plans Current work • Manuscript drafted by Christmas/New Year • Send to people who may be interested in being co-authors or “internal reviewers” (former collaborators) • Submit to journal (TBD) by end of February 2018 Next steps • Collaborate with Neil Ryan, Emma Crosbie, Katherine Payne in Manchester to integrate with their analyses based on PETALS study

Thank you! Any questions?

- Slides: 24