Lutheran and Episcopalian Heritage Part 2 The ELCA

- Slides: 37

Lutheran and Episcopalian Heritage: Part 2: The ELCA

Lutheran and Episcopalian Heritage • Feb. 10: Lutheran History-- Martin Luther's theology, the reformation, and the early Lutheran Church (Ashley Hall) • Feb. 17: The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America today -- theology, practices/beliefs (Ashley Hall) • Feb. 24: Episcopal History -- Roots in Anglican tradition, relevant monarchs and the via media, Episcopal branch (USA) and the Book of Common Prayer (Tim Anderson) • March 3: The Episcopal Church Today -- Current beliefs and practices (Tim Anderson) • March 10: The Call to Common Mission -- Creation of the agreement ("communion") between the churches: What does it say? What does it mean? (Ashley Hall) • March 17: Dialogue on the relationship between the churches: What can/should we be doing now? (community discussion)

February 17: Formation of the ELCA • The Immigrant Story – Early Cooperation between Lutherans and Episcopalians – Struggles for Identity (Confessional and Social) • Consolidations – The American Lutheran Church – The Lutheran Church in America • • The ELCA Constitution and Structures Dialogues Challenges

Lutheranism is America • Inexorably tied to the immigrant experience • Our identity is: – Tied to the diverse European origins of the immigrant – Yet, was uniquely shaped by the religious and geographical context of the United States – Thus, Lutheranism in America is unique but not uniform

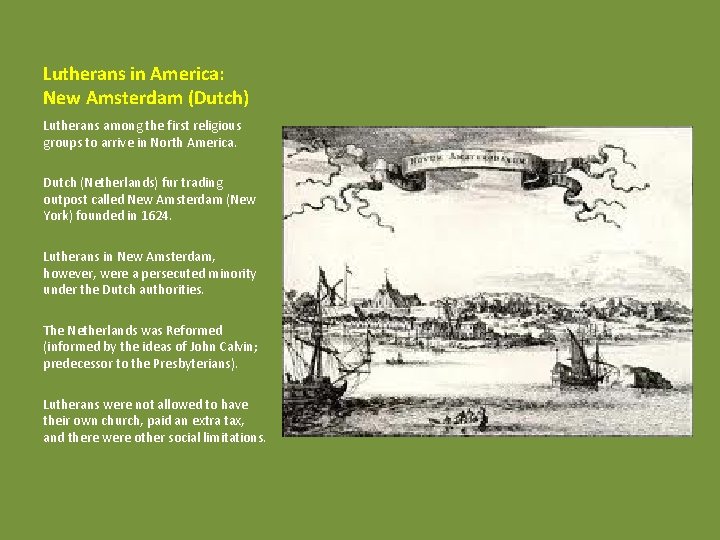

Lutherans in America: New Amsterdam (Dutch) Lutherans among the first religious groups to arrive in North America. Dutch (Netherlands) fur trading outpost called New Amsterdam (New York) founded in 1624. Lutherans in New Amsterdam, however, were a persecuted minority under the Dutch authorities. The Netherlands was Reformed (informed by the ideas of John Calvin; predecessor to the Presbyterians). Lutherans were not allowed to have their own church, paid an extra tax, and there were other social limitations.

Lutherans in America: New York Thus, when the British also claimed the mid-Atlantic, the Lutherans in New Amsterdam – from the point of view of the Dutch authorities – were guilty of treason because they refused to fight against the British. When New Amsterdam became New York, the British gave Lutherans religious toleration and gave them former Dutch Reformed congregational buildings. However, there were no Lutheran pastors to serve these congregations, so many of them closed and/or became Anglican (Episcopalian) congregations.

Lutherans in America: New Sweden (Delaware) The same is true of the earliest Swedish experience in United States. The Swedes claimed what is today eastern Delaware and western New Jersey in 1638. The had to compete against the aggressive and better funded Dutch and British. When the British defeated the Dutch and took over New Amsterdam, the Swedes decided to pull out. The Swedish king ordered every soldier and pastor (he paid their salaries!) to return home. Many did, leaving the settlers who stayed without pastoral care. As in New York, many of these Lutherans joined the Anglican/Episcopal Church, both out of necessity and because their styles of worship were basically the same (though the Swedes complained the Anglicans were “too Reformed” in their liturgy).

Lutherans in America: Pennsylvania (the Germans) • Lutheranism began to take hold in the colony of Pennsylvania, as poor German farmers sought out cheap land, 1710 -1760. • These Germans were not initially welcome, as the English settlers thought of them as another race of people with strange customs. • Benjamin Franklin worried: "Why should the Palatine boors be suffered to swarm into our settlements and, by herding together, establish their language and manners to the exclusion of ours? Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a colony of aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us, instead of our Anglifying them? "

Lutherans in America: Pennsylvania (the Germans) • These German immigrants arrived to hardscrabble land with few resources. • They could not afford to send for a pastor • Some German church sent pastors to care for their needs, but many farmers could barely support these pastors, let alone build a church and a school. • Many of the pastors were farmers in order to provide for the needs of their families.

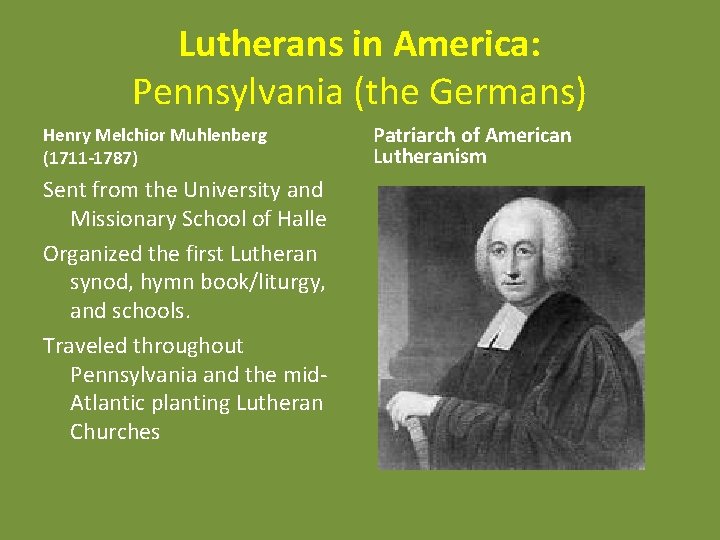

Lutherans in America: Pennsylvania (the Germans) Henry Melchior Muhlenberg (1711 -1787) Sent from the University and Missionary School of Halle Organized the first Lutheran synod, hymn book/liturgy, and schools. Traveled throughout Pennsylvania and the mid. Atlantic planting Lutheran Churches Patriarch of American Lutheranism

Muhlenberg: Lutheran Pastor and Anglican Priest Muhlenberg served Lutheran congregations in Virginia and Georgia, where the Anglican Church was the official state church. This meant, all citizens (even non. Anglicans) paid a church tax to support the Anglican Church. This meant that Lutheran congregations – often small and rural – did not have funds to pay for Muhlenberg to visit. The Anglican Bishop of New York ordained Muhlenberg into Anglican Orders as an act of pastoral care and compassion for these congregations.

Muhlenberg: Lutheran Pastor and Anglican Priest Muhlenberg was the father of a large and influential family: • Peter Muhlenberg (1746– 1847) Minister, Continental Army General, US Congressman, US Senator • Frederick Muhlenberg (1750– 1801) Member of Continental Congress, first Speaker of US House of Representatives • Gotthilf Henry Ernest Muhlenberg (1753– 1815) Botanist • John Andrew Shulze (1774– 1852) Governor of Pennsylvania • Henry A. P. Muhlenberg (1782– 1844) US Congressman and Minister to Austria • Francis Swaine Muhlenberg (1795– 1831) US Congressman

William Augustus Muhlenberg (1796 -1877) Episcopalian priest Educator Poet Philanthropist Brought the “Oxford Movement” to the United States • “He was the first to hold weekly Eucharist and daily offices in the Episcopal Church” • • •

Lutheranism in America • For most of the 1750 -1850, Pennsylvania was the heartland of American Lutheranism. • Home of Lutheran firsts in America: first synod, the first two seminaries, the first college, and largest sponsor of missionary efforts as populations grew in the western United States. • Also home to the first controversies of Lutheran identity.

Lutheranism in America • Lutherans came to the U. S. for different reasons. • Most came for economic reasons • Some, however, came as a result of religious persecution.

Lutheranism in America: Case Study 1 • In many German territories and all Scandinavian nations, the Lutheran Church was the official religion. – These Lutheran churches (often led by Bishops) retained the medieval privileges of the Church to tax each citizen and collect rent. – Therefore, some left to seek more religious freedom.

Lutheranism in America: Case Study 1 • If you leave seeking religious freedom, you might want to leave the old ways behind and become something new (something forbidden in Europe). – Therefore, some of these Lutherans embraced the more “Protestant” ideas that were dominant in America, such as: • Highest power in the democratic voice of the congregation, no hierarchy • No set liturgy and long, charismatic sermons • Open to revivalism • Strict moral code: no drinking, dancing, card playing • No taxation by the Church, only a free offering

Lutheranism in America: Case Study 2 • Another appeal to religious freedom led others to come to America as a protest to changes in Germany and a desire to keep to the old ways. • Example: the Missouri Synod – Saxony (Lutheran) was taken over by the Prussians (Calvinists). The Prussians mandated that Lutherans join with the Calvinists and give up things that were uniquely Lutheran/too Catholic: liturgy, weekly Eucharist, vestments, etc. – These Saxon Lutherans left Germany and settled in Missouri. From the start, they were very defensive and protective of their “pure Lutheran” identity.

Lutheranism in America: Case Study 3 • If you leave seeking economic opportunity, you may be quite happy with the religious situation at home and seek to establish those habits in your new environment. – Wanted to import previous ecclesiastical structures and liturgy Conflict between case studies 1 & 3 often led to two Lutheran churches of the same ethic identity but different confessional allegiance: e. g. , a Swedish congregation with vestments, liturgy, and structure like they had at home and a Swedish congregation with no vestments, no historic liturgy, and “American” church polity.

Lutheranism in America: An Ethic and Doctrinally Diverse Church(es) • It is a common phenomenon in places where Lutherans of various types settled to have several Lutheran churches. They may all be ELCA now, but one time there might have been: – One for each ethnicity (German, Danish, Swedish) – And divisions within each ethnicity (Confessionalists or “Americanists”)

Two Lutheranisms Samuel Simon Schmucker (1799 -1873) Charles Porterfield Krauth (1823 -1883)

Two Lutheranisms Do we become more “Americanized” in our religious expression? Meaning, abandoning those things that make Lutherans “more Catholic” and stand out against the larger Protestant scene in America (i. e. , Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterian) so that we can adapt and survive? Or, retain our distinctive theological convictions (such as vestments, weekly Eucharist, historical liturgy)?

Two Lutheranisms

Many Lutheranisms • The question of language and ethnicity, however, were a constant in either group. – Neither was primarily concerned with breaking of their enclaves. • Said another way, you could find theological traditionalists who embraced worship and education in English and theological progressives who insisted on retaining their linguistic and ethnic identity.

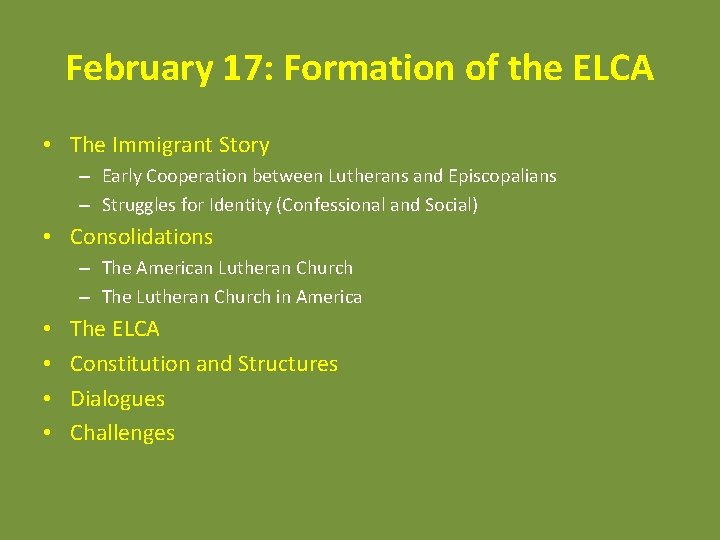

Lutheran Consolidation: American Lutheran Church (1960) • The Norwegian Synod (1853) & the Hauge Synod (1896) merged to form the Evangelical Lutheran Church (1917) • The United Danish Lutheran (1896) and the Danish Ev. Association (1884) and the Danish Ev. Luth. (1894) merged to form the United Ev. Lutheran Church (1946). • The German Iowa synod (1854) and Buffalo synod (1854) and the Ohio (1818) merged to form the American Lutheran Church (1930). • The Evangelical Luth. Church (1917), the United Ev. Luth. Church (1946) and the American Luth. Church (1930) merged to form the American Lutheran Church (1960).

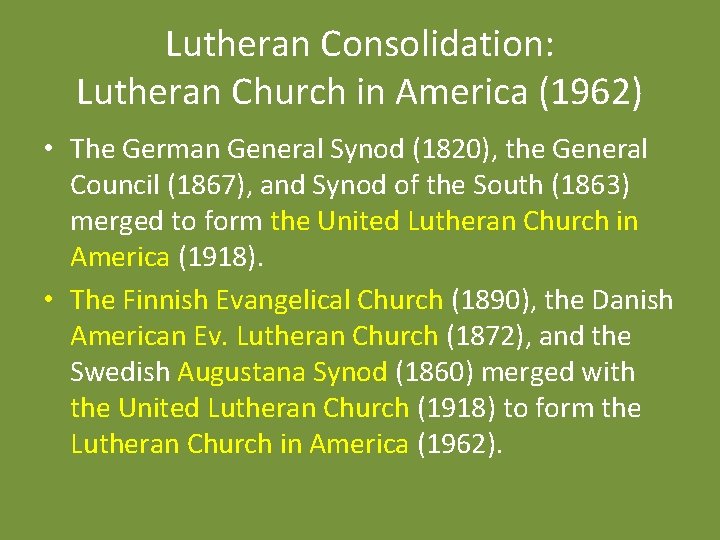

Lutheran Consolidation: Lutheran Church in America (1962) • The German General Synod (1820), the General Council (1867), and Synod of the South (1863) merged to form the United Lutheran Church in America (1918). • The Finnish Evangelical Church (1890), the Danish American Ev. Lutheran Church (1872), and the Swedish Augustana Synod (1860) merged with the United Lutheran Church (1918) to form the Lutheran Church in America (1962).

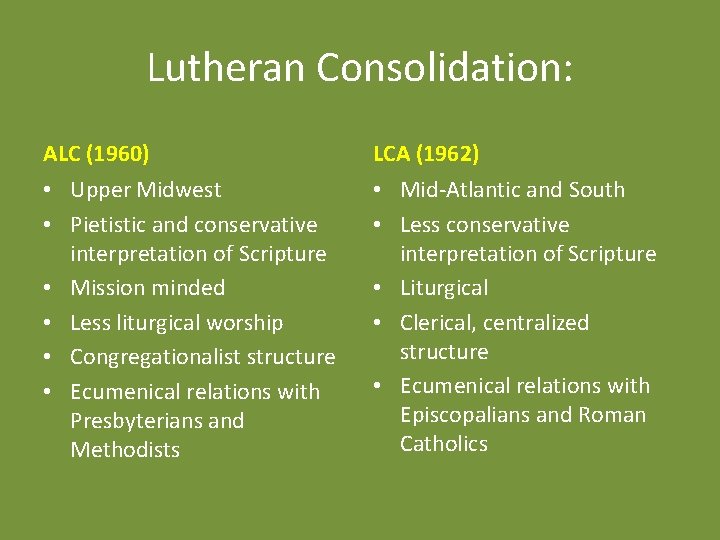

Lutheran Consolidation: ALC (1960) LCA (1962) • Upper Midwest • Pietistic and conservative interpretation of Scripture • Mission minded • Less liturgical worship • Congregationalist structure • Ecumenical relations with Presbyterians and Methodists • Mid-Atlantic and South • Less conservative interpretation of Scripture • Liturgical • Clerical, centralized structure • Ecumenical relations with Episcopalians and Roman Catholics

The Commission to Form a North American Church: Union out of Division • An internal conflict of the LC-MS over “biblical inerrancy” led to the removal of four district presidents at the 1975 convention, and by 1976 the moderates had gathered forces to form the Association of Evangelical Lutheran Churches (AELC). Approximately 300 congregations and 110, 000 people moved into the AELC from LCMS with a stated goal from the beginning of promoting unity with the ALC and LCA. • In 1977 the LCMS decision to place fellowship with ALC “in protest” along with the AELC’s “Call to Lutheran Union” nudged the three church bodies, ALC, LCA and AELC, toward merger. The 1978 ALC and LCA conventions adopted resolutions aimed at the creation of a single church body. The AELC joined them, and the ALC-LCA Committee on Church Cooperation became the Committee on Lutheran Unity (CLU) in January of 1979. • Presiding Bishop David Preus (ALC), Bishop James Crumley (LCA) and President and later Bishop William Kohn (AELC) met with the CLU over the next 16 months, and the 1980 conventions of all three church bodies adopted a two-year study process.

Formed in 1988 Largest Lutheran church in North America In union with the Lutheran World Federation and the World Council of Churches.

Formation of the ELCA

What we believe • The Bible contains the inspired word of God • We affirm the three chief Creeds: Apostles, Nicene, and Athanasian. • We acknowledge the Small Catechism and the unaltered Augsburg Confession as an authoritative interpretation of the Christian faith. • Other content in the Book of Concord is regarded as a helpful guide in doctrinal issues.

Structure of the ELCA • Congregations More than 10, 300 congregations across the United States, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands are local communities of faith-filled people celebrating, learning and connecting through weekly worship and various ways to serve others. • Synods Sixty-five synods throughout the country unite the work of congregations within their areas, serving as regional support and guiding pastoral and other staff candidates through the call process. • Churchwide Organization The churchwide expression includes the ELCA Churchwide Assembly, Church Council, officers, offices and churchwide units. Churchwide staff work from the Lutheran Center in Chicago, Ill. , and from locations around the globe.

Structure of the ELCA • Each expression works together, under the guidance of the Churchwide Assembly and Church Council, to ensure a strong foundation of leadership that enables faithful proclamation of the gospel and expressive worship, community involvement, open dialogue and a culture of support for our nearly five million members.

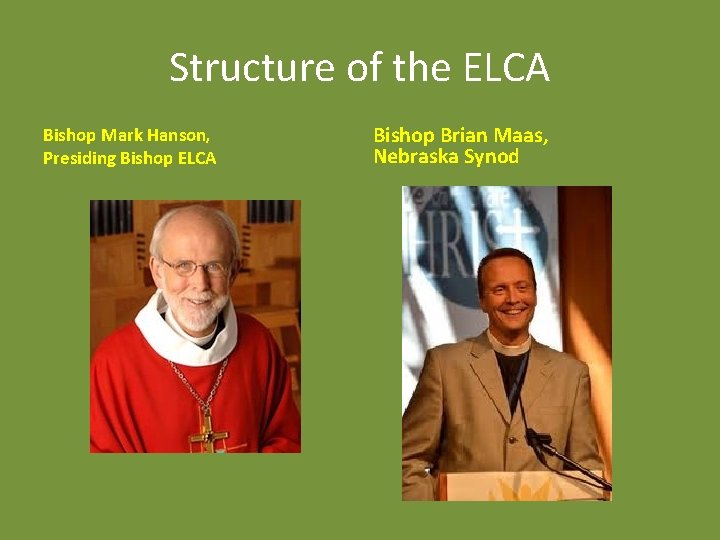

Structure of the ELCA Bishop Mark Hanson, Presiding Bishop ELCA Bishop Brian Maas, Nebraska Synod

Seminaries of the ELCA

Affiliations of the ELCA • Member of the Lutheran World Federation (140 churches, 70 million members) • Full Communion Partners with: – Presbyterian Church-USA (1997) – Reformed Church in America (1997) – The United Church of Christ (1997) – The Episcopal Church (1999) – The Moravian Church (1999) – The United Methodist Church (2009)

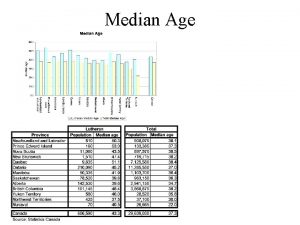

Challenges: • • Aging population Outreach to non-European groups Too many seminaries and not enough seminarians? Transition from rural to urban life Divisiveness concerning human sexuality Previous church cultures not fully blended Casualties of the “Worship Wars” and “Culture Wars” Structure too “corporate” instead of “ecclesiastical”?

Obstructed heritage and unobstructed heritage

Obstructed heritage and unobstructed heritage Sapratibandha

Sapratibandha Critical thinking club

Critical thinking club Episcopalian beliefs

Episcopalian beliefs World heritage is our heritage slogan

World heritage is our heritage slogan What is lutheran

What is lutheran Elk river lutheran church

Elk river lutheran church Protestantism vs catholicism

Protestantism vs catholicism Mr slagle gatsby

Mr slagle gatsby Texas lutheran university scholarships

Texas lutheran university scholarships Lutheran church leadership structure

Lutheran church leadership structure Elk river lutheran church

Elk river lutheran church Yuen long lutheran secondary school

Yuen long lutheran secondary school Muhlenberg lutheran church

Muhlenberg lutheran church Northland lutheran high school

Northland lutheran high school Episcopal vs lutheran

Episcopal vs lutheran Bethany lutheran primary school

Bethany lutheran primary school Se_xs

Se_xs Catholic church organizational chart

Catholic church organizational chart Grace lutheran church boone nc

Grace lutheran church boone nc Lutheran vs catholic beliefs chart

Lutheran vs catholic beliefs chart Lutheran vs catholic

Lutheran vs catholic Christ evangelical lutheran church

Christ evangelical lutheran church Lutheran foundation of st louis

Lutheran foundation of st louis Trinity lutheran school joppa tuition

Trinity lutheran school joppa tuition Lutheran cursillo

Lutheran cursillo Eden care regina lutheran home

Eden care regina lutheran home Celc lutheran

Celc lutheran Christ evangelical lutheran church

Christ evangelical lutheran church Celc lutheran

Celc lutheran Christ evangelical lutheran church

Christ evangelical lutheran church Celc lutheran

Celc lutheran Evangelical lutheran church of hong kong

Evangelical lutheran church of hong kong Intangible cultural heritage and sustainable development

Intangible cultural heritage and sustainable development Frankenstein performer heritage

Frankenstein performer heritage Communities culture and heritage

Communities culture and heritage Barton hundley

Barton hundley Indian culture and heritage

Indian culture and heritage